Abstract

Introduction

Adults with intellectual disabilities have an increased vulnerability to mental health problems and challenging behaviour. In addition to psychotherapeutic or psychoeducational methods, off-label pharmacotherapy, is a commonly used treatment modality.

Objective

The aim of this study was to establish evidence-based guideline recommendations for the responsible prescription of off-label psychotropic drugs, in relation to Quality of Life (QoL).

Method

A list of guidelines was selected, and principles were established based on international literature, guideline review and expert evaluation. The Delphi method was used to achieve consensus about guideline recommendations among a 58-member international multidisciplinary expert Delphi panel. Thirty-three statements were rated on a 5-point Likert-scale, ranging from totally disagree to totally agree, in consecutive Delphi rounds. When at least 70% of the participants agreed (score equal or higher than 4), a statement was accepted . Statements without a consensus were adjusted between consecutive Delphi rounds based on feedback from the Delphi panel.

Results

Consensus was reached on 4 general:the importance of non-pharmaceutical treatments, comprehensive diagnostics and multidisciplinary treatment. Consensus was reached in 4 rounds on 29 statements. No consensus was reached on 4 statements concerning: freedom-restricting measures, the treatment plan, the evaluation of the treatment plan, and the informed consent.

Conclusion

The study led to recommendations and principles for the responsible prescription – aligned with the QoL perspective – of off-label psychotropic drugs for adults with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour. Extensive discussion is needed regarding the issues on which there was no consensus to furthering the ongoing development of this guideline.

Introduction

The prevalence of behavioural and mental health problems in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) is estimated to be higher than in the general population (Crocker et al., Citation2014, Emerson et al., Citation2001, Hove and Havik, Citation2008, Lin and Lin, Citation2021, Lloyd and Kennedy, Citation2014, O’Dwyer et al., Citation2018, Sappok, Citation2020). People with intellectual disabilities (ID) have an increased vulnerability to mental health problems. These problems are reported to occur in 30-50% of people with ID; as compared to 10% in persons without ID (Barron et al., Citation2013, Bratek et al., Citation2017, Došen, Citation2010, Morisse, Vandevelde and Došen, Citation2014). It is relevant to point out that adults with ID often have difficulties in communicating their needs, desires and emotions (Hagan and Thompson, Citation2014). Challenging behaviour often serve a communication function, when other forms are not available (Smith et al., Citation2020). Many people with ID are treated with psychotropic medication, according to the registered indication and off-label prescription norms, and polypharmacy is common (Bowring et al., Citation2017). There are generally two reasons for prescribing psychotropic drugs in people with ID: (1) the presence or suspicion of a mental disorder, and (2) the presence of challenging behaviour, such as aggression, self-injurious behaviour, agitation and sexually unacceptable behaviour (De Kuijper et al., Citation2019). Psychotropics are often administered to address challenging behaviour without a proper indication, in absence of an underlying psychiatric disorder, so-called off-label prescribing (De Kuijper et al., Citation2019). According to a study by the World Psychiatric Association, 20% to 45% of adults with ID take psychotropics. 14% to 30% of these adults use psychotropic drugs for challenging behaviour, such as aggression or self-injurious behaviour, in the absence of a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder (Deb et al. Citation2009). Reasons leading to the use of psychotropic drugs in people with ID and challenging behaviour include behavioural control or correcting underlying psychophysiological factors associated with aggression (de Kuijper et al. Citation2010, Matson and Neal Citation2009). Moreover, stopping or phasing out psychotropics is often considered to be difficult because of fear for symptoms of restlessness or because previous attempts have failed (de Kuijper and Hoekstra Citation2017).

In the field of intellectual disability care, the concept of Quality of Life (QoL) as an outcome evaluation framework, together with the supports paradigm, are increasingly being used (Gómez Sánchez et al. Citation2022, Schalock and Verdugo Citation2002, Schalock et al. Citation2005). Both the QoL framework and the supports paradigm are essential elements in the definition of intellectual disability in the 12th edition of the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) manual (Schalock et al. Citation2021). A central idea is a social-ecological perspective that focuses on person-environmental interaction, which pays attention to the use of individualized supports to enhance human functioning and personal outcomes. With a focus on the development and interests of adults with ID, efforts are made to improve well-being, individual functioning and QoL.

Despite the increased use of the QoL framework as well as the supports paradigm, there are many restrictive practices in the treatment of people with ID and challenging behaviour (Deveau and McGill Citation2009, Sanders Citation2009, Sturmey Citation2009). Prescribing psychotropic drugs to adults with ID for challenging behaviour is considered to be a type of chemical restraint (Deb Citation2007, Edwards et al. Citation2020, García‐Domínguez et al. Citation2022, Trollor et al. Citation2016). Moreover, side-effects are common, and the effectiveness of psychotropic drugs for the treatment of challenging behaviour has not been proven (Deb et al. Citation2007, Mahan et al. Citation2010, Matson and Mahan Citation2010, Sturmey Citation2009). Although only a few studies address psychotropic side effects in the population, adults with IDD have been found to be more likely to experience side effects than those who do not have IDD (Charlot et al. Citation2020, Sheehan and Hassiotis Citation2017). The side-effects of psychotropic drugs may negatively influence one’s QoL. A large majority of patients have had at least one adverse event associated with psychotropic drug use (Deutsch and Burket Citation2021, McMahon et al. Citation2020, Scheifes et al Citation2016). More attention needs to be paid to these adverse events and their negative influence on the QoL of these patients, taking into account the lack of evidence for the effectiveness of psychotropic drugs for challenging behaviour (Scheifes et al. Citation2016).

In this regard, the QoL framework is a relevant perspective for operationalising intended outcomes in the support of people with IDD and challenging behaviour (Scheifes et al. Citation2016). Medication monitoring is important because medication-related adverse events cause, or contribute to, challenging behaviour, which can sometimes be improved by dose reduction, discontinuing the medication, and/or eliminating polypharmacy and co-pharmacy. Importantly, medications themselves may interfere with self-reported measures of QoL. These medications can be associated with a variety of neurological and metabolic side effects and contribute to ‘self-reported’ lowering or worsening of QoL (Koch et al. Citation2015). Deutsch and Burket (Citation2021) assume that adverse events associated with psychotropic drugs prescribed for challenging behaviour in adults with ID have a negative effect on QoL. According to Ramerman et al. (Citation2019) discontinuation of antipsychotics have a positive impact on health-related QoL- domains.

The QoL framework has been empirically validated across different cultures and countries. The measurable construct includes eight domains and respective indicators (Wang et al. Citation2010). Although there is some variability on how predictors and outcomes are defined (Walsh et al. Citation2010), there is general agreement across studies that outcomes are influenced by personal and environmental factors (Schalock et al. Citation2010). In a study by Morisse et al. (Citation2013), the application of QoL principles in people with ID and mental health problems was evaluated by professional workers and family members. The domains of ‘emotional well-being’, ‘interpersonal relationships’, ‘self-determination’ and ‘social inclusion’ were reported as most relevant in the case of people with ID and mental health problems. In a study by Koch et al. (Citation2015), unmet needs and psychotropic medication were identified as the most important predictors of reduced self-rated QoL, whereas an increase of psychiatric symptoms, problem behaviours, and psychotropic medication best predicted the reduced QoL proxy ratings (Koch et al. Citation2015).

The subject of QoL does not always seem to be (explicitly) addressed in international evidence-based guidelines for psychotropic drugs in adults with ID and challenging behaviour. For example, we found that in only half (four of eight) of the international western guidelines that were scanned – i.e. l’Agence Nationale de l’evaluation et de la qualité des Établissements et Services sociaux et Médico-sociaux 2016, Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust Citation2018, Deb et al. Citation2006, De Kuijper et al. Citation2019, Embregts Citation2019, Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux Citation2021, Nederlandse Vereniging van Artsen voor Verstandelijk Gehandicapten Citation2016, and Unwin and Deb Citation2010 – attention was paid to one or more QoL domains when addressing challenging behaviour in people with ID.

According to the Dutch and NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Citation2015) guidelines, QoL should be monitored and included in the evaluation of the treatment plan. The NICE guidelines emphasize not only the client’s Quality of Life, but also the family’s and caregivers’ QoL, through the establishment of a risk-benefit profile. The NICE and Canadian guidelines state that reduction in polypharmacy leads to an increase in QoL. In all of the guidelines, health-related QoL is the most frequently mentioned; whereas personal development, self-determination, interpersonal relationships, emotional and material well-being, social inclusion and rights are far less often reported on.

The aim of our study was to develop a guideline with recommendations for the responsible prescription – aligned with the QoL perspective – of off-label psychotropic drugs for adults with ID and challenging behaviour, based on the literature and clinical practice. In this context, no statements are made about concrete doses and evaluation schedules. The objective was to establish principles for careful prescribing behaviour. The guideline is meant to lead to a reduction of off-label psychotropic drug prescription in clinical practice and the improvement of QoL in patients who are treated with psychotropic drugs for challenging behaviour.

Methods

Study design

A Delphi procedure was conducted to achieve consensus among clinicians from the ID working field about principles and guideline recommendations. The Delphi method is used to reach consensus on a topic through the (subjective) opinions of experts (McPherson et al. Citation2018)

The study was conducted in cooperation with, and under the supervision of, The Superior Health Council (Belgium). The Belgian Superior Health Council draws up scientific advisory reports that aim to provide guidance to political decision-makers and health professionals (FOD Gezondheid Citation2019). Responding to current events in public health, the Superior Health Council is a high-level scientific centre of expertise in Belgium. Government and health professionals recognize the Council for their high-quality contribution to health care (FOD Gezondheid Citation2019). This cooperation reinforces the potential impact and implementation of this study and opportunities for follow-up research. To develop the guideline and establish the recommendations and principles, an ad hoc Scientific Steering Committee, chaired by a Professor in Psychiatry, was established with experts (n = 13) in the following areas: ID medicine, orthopedagogy (special needs education), psychiatry and psychology. In addition, experts with lived experience (i.e. a person with an intellectual disability and a family member) were also included in the Scientific Steering Committee. The literature review was done as part of a master’s dissertation by one of the authors. The experts in the Scientific Steering Committee completed a general statement of interest and an ad hoc statement, and the Committee on Deontology (an external and independent group, tasked with preparing opinions on the possible risk of conflict of interest) assessed the potential risk of conflict of interest.

The SSC took up different roles during the Delphi process: (1) the statements for the Delphi study were based on international guideline recommendations and guiding principles drawn up by the Scientific Steering Committee; (2) the Scientific Steering Committee defined criteria for the acceptance or rejection of the statements after each round of the Delphi study; (3) in consultation with the Scientific Steering Committee some of the statements were combined after the Delphi rounds to develop the Belgian guideline for off-label use of psychotropics in adults with ID.

Participants

The Delphi group participants were selected on the basis of their long-standing clinical expertise with the target group of people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour. Fifty-eight experts were contacted: 27 Dutch-speaking and 12 French-speaking Belgian experts, and 19 international (United Kingdom, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands) experts. The majority of the participants (n = 36) were psychiatrists (n = 33). In addition, 2 doctors for people with intellectual disabilities and 1 neurologist were involved. The international experts were recruited through the European Association for Mental Health in Intellectual Disability, and the national experts all work in specialised residential services for people with ID and mental health problems. Six participants are attached to a university, and all have published scientific articles on this topic. As there were French-, Dutch- and English-speaking participants, the decision was made to present the principles and recommendations in English in order to limit the differences related to language. Although there are no defined criteria on the minimum or maximum number of experts in a Delphi panel (McMillan et al. Citation2016), a group size of at least 10 experts is reported to be sufficient (Alizadeh et al. Citation2020). Of the 58 experts who were approached by email, 36 agreed to participate in the first round of the Delphi study. All 36 participants signed an informed consent form. In the successive Delphi rounds, only participants who completed the statements in the first round were sent the adapted statements for the next round. As sending a reminder between rounds is reported to increase the response rate by more than a quarter (Gargon et al. Citation2019), reminder e-mails were sent to non-responders who signed the informed consent and participated in the first round.

Procedure

As indicated above, the statements for the first round of the Delphi study were prepared by the researchers of the Scientific Steering Committee based on a literature review and expert opinions. The literature review focused on peer-reviewed scientific journals, reports of national and international organizations that are competent in this area (peer reviewed) and existing international evidence-based guidelines for the prescribing of psychotropic drugs to adults with ID. The PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus databases were used for the literature review. A search was conducted on the keywords ‘psychotropic drugs’, ‘challenging behaviour’, ‘responsible prescribing’ and ‘adults with ID’. Members of the Scientific Steering Committee (experts on prescribing psychotropic drugs to adults with ID) examined, in addition to the evidence-based guideline of the World Psychiatric Association (Deb et al. 2009), the most cited guidelines and the guidelines of our neighbouring countries:

Australia (Trollor et al. Citation2016)

Canada (Sullivan et al. Citation2011, Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux Citation2021)

Germany (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie, Berufsverband für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie, Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft der Leitenden Klinikärzte für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sozialpädiatrie und Jugendmedizin, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde, and Gesellschaft für Neuropädiatrie Citation2014)

France (ANESM Citation2016),

Netherlands (De Kuijper et al. Citation2019, Embregts Citation2019, Nederlandse Vereniging van Artsen voor Verstandelijk Gehandicapten Citation2016)

New Zealand (Trollor et al. Citation2016)

United States (Bhaumik et al. Citation2015),

United Kingdom (Bhaumik et al. Citation2015, Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust Citation2018, Deb et al. Citation2006, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Citation2015, Unwin and Deb Citation2010).

During the literature review, specific attention was paid to the occurrence of the keyword QoL. The results of the literature review initiated the discussion among the experts in the Scientific Steering Committee. The statements for the first round of the Delphi study were developed based on the literature review, according to QoL and presented three times to the Scientific Steering Committee.

A structured online questionnaire with statements, using SurveyMonkey (an online survey site) was sent to the 36 participants. The experts were asked to give their opinion on 33 statements. Principles deal with general principles that should be taken into account in the off-label prescribing of psychotropics to adults with ID and challenging behaviour. The guideline recommendations contain concrete prescriptions (tools for following the recommendations) and checklists. For each principle or guideline recommendation, respondents were asked to what extent they agreed with the statements, using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from totally disagree (1) to totally agree (5). They could also provide comments. The statements for which no consensus was reached were reformulated based on the comments provided and were resubmitted to the experts in the next round. Feedback from every round was given anonymously along with the invitation for the next round.

Analyses

In consultation with the Scientific Steering Group, the statements were considered accepted when at least 70% of the participants agreed (score equal to or higher than 4) and the median was equal to or higher than 4, with an interquartile range (IQR) of no more than 1. The statements for which more than 70% of the participants gave a score of 1 or 2 with a median less than 2 and an IQR less than 1 were rejected (Diamond et al. Citation2014, Von der Gracht Citation2012).

Results

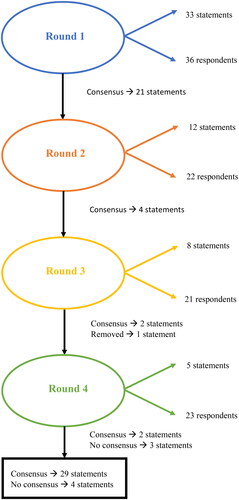

In the first round of the Delphi study, 33 statements (13 principles and 20 guideline recommendations) were sent for assessment and agreement to the Delphi panel (36 respondents). Sufficient agreement among the panel members was reached for 29 out of the 33 (or 88%) of the statements. Appendix A lists the statements, the Delphi round in which consensus was achieved, and the reformulations of statements on which there was insufficient agreement. After the first round, the experts agreed on 21 of the 33 statements. The remaining 12 statements were reformulated based on feedback from the experts. Twenty-two of the 36 experts participated in the second round. After round 2, there was consensus on 4 of the 12 remaining statements. After the third round (with 21 respondents), 2 more statements were approved, and 6 statements did not reach consensus. Five statements were reformulated for the last round of the Delphi study, in which 23 experts participated (). One principle was judged to be too controversial: Off-label use of psychotropic drugs or use outside professional guidelines’ advice is regarded as a freedom-restricting measure from the perspective of ‘Quality of Life’. The analysis of the feedback showed a discussion on medical liability. The Scientific Steering Committee decided to remove the statement because consensus could not be reached even after several adjustments.

Consensus could not be reached on some statements, and so these could not be included as guideline recommendations. The statements where no consensus was reached are presented in . The Scientific Steering Committee decided to delete 3 statements after the fourth round based on a lack of agreement (2 statements) or too many outliers (1 statement).

Table 1. Statements where no consensus was reached in a Delphi procedure aimed to achieve consensus about statements on the responsible prescribing of psychotropic drugs in adults with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviours (n respondents).

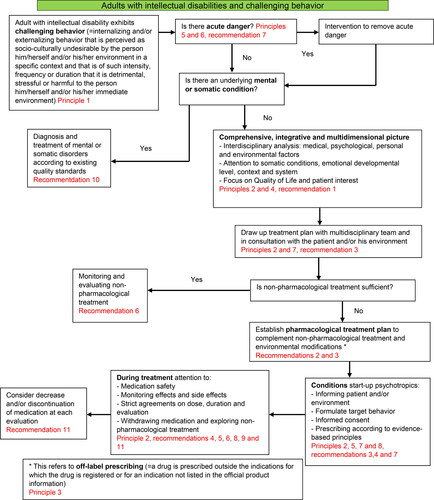

To complete the guideline of off-label psychotropic drugs for adults with ID and challenging behaviour, the Scientific Steering Committee developed a flow chart as an overview for the assessment and treatment of challenging behaviour for adults with ID, based on the feedback of the respondents. The model of the Nederlandse Vereniging Artsen Verstandelijk Gehandicapten (NVAVG, 2019) was used as an example for the flow chart. The cyclical nature of prescribing and the link with QoL were added to the NVAVG model.

By combining some of the statements after the Delphi rounds, the complete Belgian guideline for off-label use of psychotropics in adults with ID, seen from the QoL perspective, contains: the 8 principles and 11 recommendations (Appendix B). The statements were combined so each principle/guideline recommendation addressed one topic - e.g. monitoring and evaluation of the treatment, side-effects, responsibility for prescribing, etc. The Belgian guideline was supplemented with a flow chart based on the Dutch guideline on problem behaviour in adults with ID (), and an annex with concrete tools for following the guideline (Appendix C).

Figure 2. Flow chart based on Embregts (Citation2019). Multidisciplinaire Richtlijn Probleemgedrag bij volwassenen met een verstandelijke beperking. NVAVG, 2019.

Discussion

This study used a Delphi method to develop a guideline – from the perspective of the concept of QoL – for prescribing off-label psychotropic drugs to people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviours. QoL and the careful prescription of psychotropic drugs relate to safeguarding the human rights of persons with ID (Sheehan Citation2018, Verdugo et al. Citation2012). The principles and guideline recommendations were not each tested separately for QoL. QoL was considered holistically in the development of the entire guideline. Medication discontinuation was approached from the Human Rights-Based Approach and the Supports Paradigm.

The Delphi procedure led to a high level of agreement on the principles and recommendations presented in the guideline. Consensus was found for 88% of the proposed statements in the Delphi procedure. The experts shared opinions on the statements related to the importance of non-pharmaceutical treatments, comprehensive diagnostics and multidisciplinary treatment. There was consensus on the statements that treatment with off-label psychotropic drugs should never be a first choice and that strict agreements should be made regarding the administration of ‘if-necessary’ medication.

Psychological problems in people with ID are often interpreted differently by other people e.g. family, health professionals, carers (Morisse et al. Citation2014). Involving the client’s network in providing information and drafting the treatment plan (the bio-psycho-social model) is one of the principles retained in this study. The importance of QoL indicators in establishing goal behaviour and measuring treatment effectiveness is recognized by the experts. This result confirms the view that QoL can be seen as a criterion for developing support strategies (Schalock et al. Citation2016). We can conclude that it is an ongoing challenge for the natural and professional network to search for the most appropriate support strategies focused on improving the QoL of their family members or clients with ID (Morisse et al. Citation2013). When evaluating a treatment, whether medicinal or not, this should always include other factors that affect QoL such as communication opportunities, safety, access to support, community inclusion, etc. (Erickson et al. Citation2022).

Disagreement was found for the statements concerning freedom-restricting measures, the treatment plan, the evaluation of the treatment plan, and the informed consent. In our understanding, the underlying controversies can be divided into (1) ethical, (2) theoretical, (3) practical, and (4) policy-related aspects.

The first controversy (freedom-restricting measures) can be regarded as an ethical question. Some of the experts believe that off-label prescription of psychotropic drugs should not necessarily be seen as a freedom-restricting measure. An interesting question is whether or not such a measure should be labelled as freedom-restricting when the client requests this him- or herself. There seems to be a need for defining ‘freedom-restricting measures’ and how to assess them (Wet zorg en dwang: wat is onvrijwillige zorg? Citation2022). From a QoL and Human Rights perspective, the off-label prescription of psychotropic medication for challenging behaviour to adults with ID should always take into account: (1) proportionality: the measure is proportionate to the goal, (2) subsidiarity: the least intrusive measure is used, and (3) effectiveness: the measure must achieve the intended goal (Wet zorg en dwang: wat is onvrijwillige zorg? 2022).

We believe that it is important to develop a shared vision on the concept of freedom-restricting measure linked to QoL. In addition, another question is: can we consider the off-label use of psychotropic drugs as a freedom-restricting measure? A comprehensive debate is essential to discussing these ethical questions.

The second controversy (the treatment plan) primarily concerns theoretical issues. Expert opinions are less divided (as compared to the ethical question on freedom-restricting measures), but there is still no consensus according to the pre-defined criteria. There is an agreement that information is needed, whether written down in a treatment plan or not. The results reflect the need for involving the environment/family in drawing up the treatment plan. This finding confirms the view of Došen (Citation2010) regarding the essential role of the environment. According to Morisse and Došen (Citation2017), the search for appropriate treatment starts primarily from the environment by indicating that adjustments in the environment may lead to less focus on challenging behaviour. Research has also shown that involving family has a positive impact on the QoL of persons with ID (Lei & Kantor Citation2021). Disagreement among the experts on this statement was mainly due to a lack of theoretical background information, such as:

What should be mentioned in the treatment plan?

Should there be more emphasis on non-pharmaceutical treatment strategies?

What is the feasibility of drawing up a written multidisciplinary treatment plan?

Experts disagree on what should be in the treatment plan. Further debate is needed to clarify this and to make theoretically underpinned choices on the content of a treatment plan.

The third controversy (evaluation of the treatment plan) relates to practical obstacles. The results suggest a gap between how often prescribers would ideally like to evaluate and the practical feasibility. Ramerman (Citation2019) argues that long-term psychotropic use in adults with ID can often be attributed to a lack of monitoring the effect of treatment. Sheehan et al. (Citation2015) also note that psychotropic drugs are often prescribed long-term without necessarily being properly evaluated. This confirms the importance of setting an evaluation timeframe, without losing sight of feasibility. The Delphi study shows that an evaluation term cannot always be fixed, but depends on the indication, the medication, the context and the patient. Still, frequent evaluation remains the target.

The fourth controversy (informed consent) concerns a policy choice to be made. A distinction should be made between the legal representative, the professional support worker, and a family member. In Belgium, the judge appoints a legal representative if he/she considers that the adult with ID is legally incapacitated (Federale Overheidsdienst, n.d.). The finding highlights the role of the context, as research by Schalock et al. (Citation2009) confirms. The feedback of the experts shows the importance of providing information to the client and his/her network. Some experts argue that excessive control of the context can be detrimental to a patient’s QoL. There is insufficient scientific research to support or reject this opinion. But if the patient is unable to give consent, the prescriber is responsible: the prescriber acts in the patient’s best interest, according to good medical practice. Relevant questions include: Who is ultimately responsible? Is it a shared responsibility? What is the legality if the patient himself refuses? What information is required to make a consent valid? The above dilemmas point to policy barriers that need to be resolved before a consensus can be found.

These four controversies require further attention and debate, in close cooperation between experts, practitioners, policymakers and other stakeholders, including clients and their families. Organizing focus groups would be a useful and relevant pathway to discussing these complex controversies. Focus groups allow a more dynamic exchange of ideas on complex concepts such as QoL, restriction of freedom, and ethical and medico-legal issues.

Together with experts from clinical practice, we developed a guideline from a holistic approach. This guideline is meant to lead to a reduction of off-label psychotropic medication use and an improvement of QoL by addressing unmet needs with alternative treatments. After the guideline has been implemented and then evaluated, it could be further enhanced by the outcome of the debate concerning the controversies identified above. The developed guideline is a starting point for raising awareness and should be reviewed regularly.

Limitations of the study

In this study, the literature review was limited to examining how often, and in what way, QoL was addressed in 8 western international evidence-based guidelines. A literature review examining other issues – such as the extent of evidence, from which point of view, etc. – could have strengthened the study. This study may help to explicitly integrate the perspective of QoL in the prescribing of off-label psychotropics for challenging behaviour to adults with ID.

The composition of the group of experts in Delphi studies is essential. Careful consideration was given to the selection of the expert panel. Nevertheless, despite this specific attention, it would be an added value if more countries were represented on the Delphi panel. Furthermore the results might be dominated by a psychiatric perspective, since all of the experts were psychiatrists. This might have limited a wider range of expertise across other (mental) health professionals, such as general practitioners, who are (at least in Belgium) authorised to prescribe psychotropic medication, including to adults with ID. Given the focus on a multidisciplinary treatment plan, the absence of experts from multidisciplinary service providers and the lack of clients in the Delphi panel could be seen as a limitation of this study. For example, general practitioners or multidisciplinary service providers could advise on the feasibility of some of the principles and guideline recommendations.

Furthermore, we have to remain aware that QoL is difficult to measure. Despite our focus on QoL during the study, we cannot make any statements about the increase of QoL when following the developed guideline. In this study, the focus was not looking for a normative framework, but to improve QoL at an individual level. A relevant follow-up study could be to assess whether the guideline leads to an increase in QoL and/or a reduction in using off-label psychotropic medication. Consequently, the guideline can be operationalized in terms of QoL by designing an instrument that links QoL and medication use in adults with ID, starting from a person-centered approach rather than a prescriptive framework. Finally, it is important to remember that consensus does not mean that a principle/guideline is not dynamic.

Conclusion and further research

A consensus guideline was developed. We described four underlying controversies that might have led to not reaching consensus for some recommendations or principles that, therefore, could not be included in the guideline. An extensive discussion regarding these controversies is needed – for example, by organising focus groups on these controversies, which might be helpful in furthering the ongoing development of this guideline.

Future research could focus on the effectiveness, implementation and feasibility in practice of the principles/recommendations on psychotropic medication use, as well as on the impact of the guideline on a patient’s QoL. It is also advantageous to monitor and revise the principles/recommendations on a regular basis. A pilot study is currently being set up in Belgium in which, first of all, the effects of applying the developed guideline in adults with ID and challenging behaviour will be investigated (impact evaluation), and secondly, the process of phasing out the medication will be described in detail (process evaluation). The impact evaluation will identify the effect of the phasing out on QoL, global functioning, challenging behaviour and side effects.

The developed guideline focuses on adults with ID. According to McLaren and Lichtenstein (Citation2019), psychotropics are also frequently prescribed, often off-label and long-term, to children and adolescents with ID and challenging behaviour. Therefore, it is recommended to set up a similar study for this target group.

Acknowledgements

This publication was authored by Pauline Laermans, Filip Morisse, Marco Lombardi, Sylvie Gérard, Stijn Vandevelde, Gerda de Kuijper, Kurt Audenaert and Claudia Claes. All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. This article has been written as part of a scientific advisory report by the Superior Health Council on the use of off-label psychotropic drugs for adults with intellectual disabilities. The authors were members of the ad hoc working group and sincerely thank the other members of the group (Godelieve Baetens, Gunther Degraeve and Eric Willaye).The research was made possible by the support of EQUALITY ResearchCollective and Scientific Foundation Mental Health Care Organisation Brothers of Charity. We would like to thank the members of the Scientific Steering Committee for their advice and the theory and practice elements in this study. We are also grateful to the national and international participants of the Delphi study for their time and input.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alizadeh, S., Maroufi, S. S., Sohrabi, Z., Norouzi, A., Dalooei, R. J. and Ramezani, G. 2020. Large or small panel in the Delphi study? Application of bootstrap technique. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences, 9, 1267–1271.

- ANESM. 2016, December. Les «comportements-problèmes»: Prévention et réponses au sein des établissements et services intervenant auprès des enfants et adultes handicapés. Agence nationale de l’évaluation et de la qualité des établissements et services sociaux en médico-sociaux. Geraadpleegd op 14 mei 2021, van https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2018-03/rbpp_comportements_problemes_volets_1_et_2.pdf

- Barron, D. A., Molosankwe, I., Romeo, R. and Hassiotis, A. 2013. Urban adolescents with intellectual disability and challenging behaviour: Costs and characteristics during transition to adult services. Health & Social Care in the Community, 21, 283–292.

- Bhaumik, S., Gangadharan, S. K., Branford, D. and Barrett, M. 2015. The Frith Prescribing Guidelines for People with Intellectual Disability. 3de editie. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

- Bowring, D. L., Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Toogood, S. and McMahon, M. 2017. Prevalence of psychotropic medication use and association with challenging behaviour in adults with an intellectual disability. A total population study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 61, 604–617.

- Bratek, A., Krysta, K. and Kucia, K. 2017. Psychiatric comorbidity in older adults with intellectual disability. Psychiatria Danubina, 29, 590–593.

- Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust. 2018, September. Prescribing guidance for managing adults with learning disability who displays behaviours that challenge. Camden and Islington.

- Charlot, L. R., Doerfler, L. A. and McLaren, J. L. 2020. Psychotropic medications use and side effects of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 64, 852–863.

- Crocker, A. G., Prokić, A., Morin, D. and Reyes, A. 2014. Intellectual disability and co-occurring mental health and physical disorders in aggressive behaviour. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR, 58, 1032–1044.

- Deb, S. 2007. The role of medication in the management of behaviour problems in people with learning disabilities. Advances in Mental Health and Learning Disabilities, 1, 26–31.

- Deb, S. Clarke, D. and Unwin, G. 2006, September. Using medication to manage behaviour problems among adults with a learning disability. University of Birmingham.

- Deb, S., Sohanpal, S. K., Soni, R., Lenôtre, L. and Unwin, G. 2007. The effectiveness of antipsychotic medication in the management of behaviour problems in adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR, 51, 766–777.

- De Kuijper, G., Degraeve, G. and Zintkstok, J. R. 2019. Voorschrijven van psychofarmaca bij mensen met een verstandelijke beperking: Handvatten voor de praktijk. Tijdschrift Voor Psychiatrie, 61, 786–791.

- de Kuijper, G. M. and Hoekstra, P. J. 2017. Physicians’ reasons not to discontinue long-term used off-label antipsychotic drugs in people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR, 61, 899–908.

- de Kuijper, G., Hoekstra, P., Visser, F., Scholte, F. A., Penning, C. and Evenhuis, H. 2010. Use of antipsychotic drugs in individuals with intellectual disability (ID) in the Netherlands: Prevalence and reasons for prescription. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR, 54, 659–667.

- Deb, S.,Kwok, H.,Bertelli, M.,Salvador-Carulla, L.,Bradley, E.,Torr, J. andBarnhill, J. 2009. International guide to prescribing psychotropic medication for the management of problem behaviours in adults with intellectual disabilities. World Psychiatry : official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 8, 181–186.

- Deutsch, S. I. and Burket, J. A. 2021. Psychotropic medication use for adults and older adults with intellectual disability; selective review, recommendations and future directions. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 104, 110017.

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie, Berufsverband für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie, Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft der Leitenden Klinikärzte für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sozialpädiatrie und Jugendmedizin, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde, & Gesellschaft für Neuropädiatrie. 2014, December. S2k Praxisleitlinie Intelligenzminderung. AWMF Online. Geraadpleegd op 10 april 2021, van https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/028-042.html

- Deveau, R. and McGill, P. 2009. Physical interventions for adults with intellectual disabilities: Survey of use, policy, training and monitoring. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22, 145–151.

- Diamond, I. R., Grant, R. C., Feldman, B. M., Pencharz, P. B., Ling, S. C., Moore, A. M. and Wales, P. W. 2014. Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67, 401–409.

- Došen, A. 2010. Psychische stoornissen, gedragsproblemen en verstandelijke handicap. Assen, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Van Gorcum.

- Edwards, N., King, J., Williams, K. and Hair, S. 2020. Chemical restraint of adults with intellectual disability and challenging behaviour in Queensland, Australia: Views of statutory decision makers. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities : JOID, 24, 194–211.

- Embregts. 2019. Multidisciplinaire Richtlijn Probleemgedrag bij volwassenen met een verstandelijke beperking. NVAVG, 2019.

- Emerson, E., Kiernan, C., Alborz, A., Reeves, D., Mason, H., Swarbrick, R., Mason, L. and Hatton, C. 2001. The prevalence of challenging behaviors: A total population study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 22, 77–93.

- Erickson, S. R., Houseworth, J. and Esler, A. 2022. Factors associated with use of medication for behavioral challenges in adults with intellectual and developmental disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 123, 104182.

- Federale Overheidsdienst. n.d. Bescherming van meerderjarigen. Federale overheidsdienst Justitie. https://justitie.belgium.be/nl/themas_en_dossiers/personen_en_gezinnen/bescherming_van_meerderjarigen

- FOD Gezondheid. 2019, Juli. Bestuursovereenkomst 2019–2021. Geraadpleegd op 2 januari 2022, van https://www.health.belgium.be/nl/bestuursovereenkomst-2019-2021#anchor-35938

- García‐Domínguez, L., Navas, P., Verdugo, M. N., Arias, V. B. and Gómez, L. E. 2022. Psychotropic drugs intake in people aging with intellectual disability: Prevalence and predictors. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities : JARID, 35, 1109–1118.

- Gargon, E., Crew, R., Burnside, G. and Williamson, P. R. 2019. Higher number of items associated with significantly lower response rates in COS Delphi surveys. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 108, 110–120.

- Gómez Sánchez, L. E., Morán Suárez, M. L., Al-Halabí Díaz, S., Swerts, C., Verdugo Alonso, M. Á. and Schalock, R. L. 2022. Quality of life and the international convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: Consensus indicators for assessment. Psicothema, 34, 182–191

- Hagan, L. and Thompson, H. 2014. It’s good to talk: Developing the communication skills of an adult with an intellectual disability through augmentative and alternative communication. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42, 66–73.

- Hove, O. and Havik, O. E. 2008. Mental disorders and problem behavior in a community sample of adults with intellectual disability: Three-month prevalence and comorbidity. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 1, 223–237.

- Institut National D’excellence En Santé Et En Services Sociaux. 2021, mei. Troubles graves du comportement: Meilleures pratiques en prévention, en évaluation et en intervention auprès des personnes qui présentent une déficience intellectuelle, une déficience physique ou un trouble du spectre de l’autisme . INESSS. Geraadpleegd op, 14 mei 2021, van https://www.inesss.qc.ca/fileadmin/doc/INESSS/Rapports/ServicesSociaux/INESSS_TGC_EC.pdf

- Koch, A. D., Vogel, A., Becker, T., Salize, H.-J., Voss, E., Werner, A., Arnold, K. and Schützwohl, M. 2015. Proxy and self-reported quality of life in adults with intellectual disabilities: Impact of psychiatric symptoms, problem behaviour, psychotropic medication and unmet needs. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 45-46, 136–146.

- Lei, X. and Kantor, J. 2021. Correlates of social support and family quality of life in chinese caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 68, 1–14.

- Lin, J. D. and Lin, L. P. 2021. Mental disorders and the impacts in older adults with intellectual disabilities. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 8, 239–243.

- Lloyd, B. P. and Kennedy, C. H. 2014. Assessment and treatment of challenging behaviour for individuals with intellectual disability: A research review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities : JARID, 27, 187–199.

- Mahan, S., Holloway, J., Bamburg, J. W., Hess, J. A., Fodstad, J. C. and Matson, J. L. 2010. An examination of psychotropic medication side effects: Does taking a greater number of psychotropic medications from different classes affect presentation of side effects in adults with ID? Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31, 1561–1569.

- Matson, J. L. and Mahan, S. 2010. Antipsychotic drug side effects for persons with intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31, 1570–1576.

- Matson, J. L. and Neal, D. 2009. Psychotropic medication use for challenging behaviors in persons with intellectual disabilities: An overview. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 572–586.

- McLaren, J. L. and Lichtenstein, J. D. 2019. The pursuit of the magic pill: The overuse of psychotropic medications in children with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the USA. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 28, 365–368.

- McMahon, M., Hatton, C. and Bowring, D. L. 2020. Polypharmacy and psychotropic polypharmacy in adults with intellectual disability: A cross‐sectional total population study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 64, 834–851.

- McMillan, S. S., King, M. and Tully, M. P. 2016. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 38, 655–662.

- McPherson, S., Reese, C. and Wendler, M. C. 2018. Methodology update. Nursing Research, 67, 404–410.

- Morisse, F. and Dosen, A. 2017. SEO-R2. 2de ed. Antwerpen, Belgium: Garant.

- Morisse, F., Vandemaele, E., Claes, C., Claes, L. and Vandevelde, S. 2013. Quality of life in persons with intellectual disabilities and mental health problems: An explorative study. TheScientificWorldJournal, 2013, 491918.

- Morisse, F., Vandevelde, S. and Došen, A. 2014. Mensen met een verstandelijke beperking en geestelijke gezondheidsproblemen: Een praktijkdefinitie. Vlaams Tijdschrift Voor Orthopedagogiek, 33, 21–33.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015. Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: Prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges. In National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NG11). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng11

- Nederlandse Vereniging van Artsen voor verstandelijk Gehandicapten 2016. Revisie NVAVG standaard: Voorschrijven van psychofarmaca. NVAVG. Geraadpleegd op 10 maart 2021, van https://nvavg.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/16_367_NVAVG_richtlijn-Psychofarmaca_digitale-versie-WATERMERK.pdf

- O’Dwyer, M., McCallion, P., McCarron, M. and Henman, M. 2018. Medication use and potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults with intellectual disabilities: A neglected area of research. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety, 9, 535–557.

- Ramerman, L. 2019. Off-label use of antipsychotic medication in people with intellectual disabilities: adherence to guidelines, long-term effectiveness, and effects on quality of life. Groningen, the Netherlands: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen.

- Ramerman, L., Hoekstra, P. J. and de Kuijper, G. 2019. Changes in health-related quality of life in people with intellectual disabilities who discontinue long-term used antipsychotic drugs for challenging behaviors. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 59, 280–287.

- Sanders, K. 2009. The effects of an action plan, staff training, management support and monitoring on restraint use and costs of work-related injuries. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22, 216–220.

- Sappok, T., Došen, A., Zepperitz, S., Barrett, B., Vonk, J., Schanze, C., Ilic, M., Bergmann, T., De Neve, L., Birkner, J., Zaal, S., Bertelli, M. O., Hudson, M., Morisse, F. and Sterkenburg, P. 2020. Standardizing the assessment of emotional development in adults with intellectual and developmental disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities : JARID, 33, 542–551.

- Schalock, R. L., Borthwick-Duffy, S. A., Buntinx, W. H. E., Coulter, D. L. and Craig, E. M. 2009. Intellectual disability: Definition, classification, and systems of supports. 11th ed. Washington: American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

- Schalock, R. L., Keith, K. D., Verdugo, M. and Gómez, L. E. 2010. Quality of life model development and use in the field of intellectual disability. In: R. Kober (Red.) Enhancing the Quality of Life of People with Intellectual Disabilities. Dordrecht: Springer, p.17–32.

- Schalock, R. L., Luckasson, R. and Tassé, M. J. 2021. An overview of intellectual disability: Definition, diagnosis, classification, and systems of Supports (12th ed.). American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 126, 439–442.

- Schalock, R. L. and Verdugo, M. A. 2002. Handbook on quality of life for human service practitioners. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation.

- Schalock, R. L., Verdugo, M. A., Gomez, L. E. and Reinders, H. S. 2016. Moving us toward a theory of individual quality of life. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 121, 1–12.

- Schalock, R. L., Verdugo, M. A., Jenaro, C., Wang, M., Wehmeyer, M., Jiancheng, X. and Lachapelle, Y. 2005. Cross-cultural study of quality of life indicators. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 110, 298.2.0.CO;2]

- Scheifes, A., Walraven, S., Stolker, J. J., Nijman, H. L., Egberts, T. C. and Heerdink, E. R. 2016. Adverse events and the relation with quality of life in adults with intellectual disability and challenging behaviour using psychotropic drugs. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 49-50, 13–21.

- Sheehan, R. 2018. Optimising psychotropic medication use. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 23, 22–26.

- Sheehan, R. and Hassiotis, A. 2017. Reduction or discontinuation of antipsychotics for challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: A systematic review. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 4, 238–256.

- Sheehan, R., Hassiotis, A., Walters, K., Osborn, D., Strydom, A. and Horsfall, L. 2015. Mental illness, challenging behaviour, and psychotropic drug prescribing in people with intellectual disability: UK population based cohort study. BMJ, 351, h4326.

- Smith, M., Manduchi, B., Burke, E., Carroll, R., McCallion, P. and McCarron, M. 2020. Communication difficulties in adults with Intellectual Disability: Results from a national cross-sectional study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 97, 103557.

- Sturmey, P. 2009. It is time to reduce and safely eliminate restrictive behavioural practices. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22, 105–110.

- Sullivan, W.F., Berg, J.M., Bradley, E., Cheetham, T., Denton, R., Heng, J., Hennen, B., Joyce, D., Kelly, M., Korossy, M. and Lunsky, Y. 2011. Primary care of adults with developmental disabilities: Canadian consensus guidelines. Canadian Family Physician, 57, 541–553.

- Trollor, J. N., Salomon, C. and Franklin, C. 2016. Prescribing psychotropic drugs to adults with an intellectual disability. Australian Prescriber, 39, 126–130.

- Unwin, G. and Deb, S. 2010. The use of medication to manage behaviour problems in adults with an intellectual disability: A national guideline. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 4, 4–11.

- Verdugo, M. A., Navas, P., Gómez, L. E. and Schalock, R. L. 2012. The concept of quality of life and its role in enhancing human rights in the field of intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR, 56, 1036–1045.

- Von der Gracht, H. A. 2012. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79, 1525–1536.

- Walsh, P. N., Emerson, E., Lobb, C., Hatton, C., Bradley, V. J., Schalock, R. L. and Moseley, C. B. 2010. Supported accommodation for people with intellectual disabilities and quality of life: An overview. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 7, 137–142.

- Wang, M., Schalock, R. L., Verdugo, M. A. and Jenaro, C. 2010. Examining the factor structure and hierarchical nature of the quality of life construct. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 115, 218–233. 10.1352/1944-7558-115.3.218

- Wet zorg en dwang: wat is onvrijwillige zorg?. 2022, 9 November. kennispleingehandicaptensector_nl. https://www.kennispleingehandicaptensector.nl/tips-tools/tools/wet-zorg-en-dwang-wat-is-onvrijwillige-zorg