ABSTRACT

Currently vaccines protecting from COVID-19 are a scarce resource. Prioritising vaccination for certain groups of society is placed in a context of uncertainty due to changing evidence on the available vaccines and changing infection dynamics. To meet accepted ethical standards of procedural justice and individual autonomy, vaccine allocation strategies need to state reasons for prioritisation explicitly while at the same time communicating the expected risks and benefits of vaccination at different times and with different vaccines transparently. In this article, we provide a concept summarising epidemiological considerations underlying current vaccine prioritisation strategies in an accessible way. We define six priority groups (vulnerable individuals, persons in close contact with the vulnerable, key workers with direct work-related contact with the public, key workers without direct work-related contact to the public, dependents of key workers and members of groups with high interpersonal contact rates) and state vaccine priorities for them. Additionally, prioritisation may follow non-epidemiological considerations including the aim to increase intra-societal justice and reducing inequality. While national prioritisation plans integrate many of these concepts, the international community has so far failed to guarantee equitable or procedurally just access to vaccines across settings with different levels of wealth.

Vaccine prioritization – a case for procedural justice in public health

The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) lists eleven vaccines for COVID-19 that are currently licensed. Still, globally, vaccines protecting from COVID-19 are a scarce and highly precious resource. Availability and access to different vaccines differ widely between countries and regions[Citation1]. All countries are currently forced to implement prioritization schemes to allocate available vaccine doses to groups of people. Vaccine prioritization implies unequal access to a potentially life-saving resource – and, prospectively, to some services (e.g. international travel) – so, it inevitably raises issues of distributive justice.

Uncertainties (such as vaccine safety and effectiveness, or changes in viral populations) complicate the ethical issue of fair and efficient allocation of vaccines, and risk fostering disagreement about the principles and values that should govern priority settings. To overcome these situations, and to guide decision makers toward fair and legitimate public health measures, Daniels and Sabin have developed the theoretical framework ‘accountability for reasonableness’[Citation2]. Their framework outlines that a fair prioritization process requires: publicity (transparency) of the grounds on which decisions are made, wide acceptance of the relevance of decisions to meet health needs fairly; and procedures for revising decisions in response to emerging challenges. Although the framework was conceived as a rational tool for priority management – and as such it has been adopted during the actual pandemic e.g. in the United Kingdom[Citation3], its potential for promoting the acceptance of priority-setting decisions and trust in health care systems has also been highlighted [Citation2] The first two criteria, publicity and relevance, especially challenge the scientific community to communicate reasons and justifications underlying the political decision-making process in an accessible way[Citation4].

The problem of vaccine selection and prioritization

The aim of currently available vaccines is to protect people from disease at the lowest possible risk of adverse effects. Their ability to prevent infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is still less certain. If all vaccines were equally available globally, it is likely that everyone would choose the vaccine with the highest likelihood of individual protection and the best safety profile.

However, because of ongoing high transmission numbers for COVID-19 in many countries and persistent risk of reintroduction of the virus in places with low numbers of cases, waiting for the best vaccine and forgoing the advantages of earlier vaccination with the available vaccines is not generally desirable either for the individual nor for public health policy. High numbers of new infections create a situation whereby receiving a safe but only partially effective vaccine earlier may be preferable to a better vaccine later. Concurrently, infection control on a public health level strongly benefits from vaccines that prevent transmission[Citation5].

To maximize the gains from vaccination programmes it is necessary to allocate available vaccines strategically, at the same time as allowing for individual autonomy through transparent communication of true risks and benefits of offered vaccines. The uncertainty about the precise usefulness of available vaccines contributes to vaccine hesitancy and even rejection of highly effective vaccines in many European countries on the grounds that other vaccines (i.e. mRNA-vaccines, at the time of writing) are perceived as superior, while the advantages of unused vaccines remain insufficiently explained. In fact, it is unused vaccines at a time of global shortage that has prompted decision-makers to question the very usefulness of prioritization in general.

Three constituent perspectives for forming a prioritization plan

Individual considerations: advantages and disadvantages of being prioritized

Currently, motivation to receive a vaccine and demand for early vaccination are both high[Citation1]. Many advantages seem to come with belonging to a high priority group. Licensed vaccines decrease the probability of developing COVID-19 disease, of being hospitalized and of death from COVID-19[Citation6]. They may also decrease the possibility of spreading infection to friends and family[Citation6]. Being placed in a high-priority group shortens the time to vaccination, thereby maximizing health and social benefits for those vaccinated.

The most important disadvantage is that prioritized people may receive an inferior vaccine. This already happens when a vaccine with lower efficacy is offered to prioritized groups because it is the only one available at the time, despite licensed vaccines with higher efficacy being available elsewhere. As the pandemic progresses, it is also highly likely that adaptations to mutations of SARS-CoV-2 will result in later generation vaccines conveying better protection from changed viral populations[Citation7]. Third, despite proven safety in licensing studies, phase IV studies in larger populations and adverse effect surveillance may uncover longer-term safety concerns for some of the already licensed vaccines.

Epidemiological considerations for prioritization: maximizing vaccine impact on morbidity and mortality

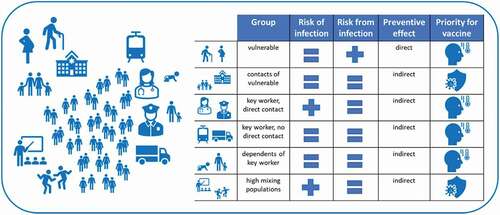

The aim of prioritization is to allocate available vaccine doses where their impact on morbidity and mortality is expected to be highest[Citation8]. Allocating vaccines randomly would prevent disease in a proportion of vaccinated people close to the vaccine efficacy determined by phase III trials and indirect effects would only manifest after high vaccine coverage in the population. Indirect effects can be the prevention of secondary (‘onwards’) cases of infection, if a vaccine can prevent transmission, or of secondary adverse health events due to disruption of order, infrastructure and medical services[Citation8]. provides a schematic overview of prioritized groups accompanied by the main reasoning that justifies prioritization and related rationales. The expected population efficiency of vaccinating these groups with a suitable vaccine decreases from top to bottom of the table. summarizes reasons for prioritization and requirements for vaccines for these groups.

Table 1. Summarizes reasons for prioritization and requirements for vaccines

prevention of disease

prevention of disease prevention of transmission

prevention of transmission higher or

higher or![]() equal compared to the general population.

equal compared to the general population.

Science can provide guidance on who should be placed in which group, e.g. by quantifying the relative risk of severe disease or death for at-risk groups or by providing cost-benefit analyses informed by modeling studies. The urgency of prioritizing key workers and their dependents depends on several factors, most importantly (a) the level of transmission in the population, as this drives the risk of infection and (b) the capacity of services to compensate short- to medium-term loss of staff. A high proportion of informal employment can impede identification of key workers in other fields than health care and public services.

Non-epidemiological considerations on prioritization: integrating plans with the interests of society and factual limitations

From a philosophical perspective, egalitarian and utilitarian approaches to a just prioritization can be distinguished. Egalitarian approaches follow the ideal that resources should be shared equally according to need, regardless of further criteria, such as social utility. Utilitarian approaches pursue the greatest benefit for the greatest number. This means that higher social utility of a person might result in a higher priority. If medical personnel are considered necessary to help a great number of the rest of a population, this would justify a prioritization of this group. Current triage plans try to balance egalitarian and utilitarian approaches[Citation11].

Societies may choose to incorporate criteria that do not strictly focus on preventing morbidity and mortality in the current pandemic. An example may be that frontline health workers and other group 3 workers were relied upon to keep services running at a time of high uncertainty. At the beginning of the pandemic, neither the individual risk from SARS-CoV-2 infection was known nor which infection control measures would be appropriate and additionally, infection control measures were only partially available[Citation12]. Society may perceive it as damaging to these workers’ long-term motivation and willingness to be in a position at risk, if they now feel that they have to wait overly long for the vaccine when it is already available to others. Following such social criteria is not wrong, but they must be made transparent in the same way as the epidemiological criteria, in order to achieve procedural justice. Some social criteria may also overlap with epidemiological considerations. If, for instance, men are at a higher risk of suffering from severe courses, there might be an epidemiological argument for placing them in a higher priority group than women. Gender is at the same time a social category and, consequently, a transparent discourse about prioritization according to sex and gender may need to include issues of gender inequality as well. Questions of inter-generational justice fall under the same category.

Prioritization can act as a tool to lower inequality by allocating vaccines based on expected benefits rather than status or monetary wealth[Citation2]. National prioritization plans integrate this aspect, but the international community has so far failed to guarantee equitable access to vaccines across settings with different levels of wealth[Citation1]. Prioritization plans between countries, but also within countries with limited infrastructure for vaccine distribution, need to take additional aspects of feasibility of vaccine deployment into account. Deployment of all vaccines can be hindered by logistical and administrative challenges posed by the absence of adult vaccine programmes in about one third of WHO member countries[Citation1]. This means that neither resources for deploying vaccines (e.g. staff, transport) nor data and infrastructure for planning (e.g. demographic data, population access points and traceable documentation) may be available. Deployment of vaccines requiring ultra-cold chains (currently the mRNA vaccines) poses an additional challenge. In this context, prioritization plans may need to adapt to feasibility to prevent delays or waste of vaccines.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wouters OJ, Shadlen KC, Salcher-Konrad M, et al. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet. 2021;397:1023–1034.

- Daniels N, Sabin JE. Accountability for reasonableness: an update. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2008;337:a1850.

- Campos-Matos I, Mandal S, Yates J, et al. Maximising benefit, reducing inequalities and ensuring deliverability: prioritisation of COVID-19 vaccination in the UK. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;2: 100021.

- Feufel MA, Antes G, Gigerenzer G. Competence in dealing with uncertainty: lessons to learn from the influenza pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2010;53(12):1283–1289.

- Saad-Roy CM, Levin SA, Metcalf CJE, et al. Trajectory of individual immunity and vaccination required for SARS-CoV-2 community immunity: a conceptual investigation. J R Soc Interface. 2021;18(175):20200683.

- Hall VJ, Foulkes S, Saei A, et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against infection and COVID-19 vaccine coverage in healthcare workers in England, multicentre prospective cohort study (the SIREN study). SSRN 2021. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3790399.

- Wang Z, Schmidt F, Weisblum Y, et al. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature 2021;592(7855):616–622. .

- Bubar KM, Reinholt K, Kissler SM, et al. Model-informed COVID-19 vaccine prioritization strategies by age and serostatus. Science. 2021;371(6532):916–921. .

- Hassan-Smith Z, Hanif W, Khunti K. Who should be prioritised for COVID-19 vaccines? Lancet. 2020;396(10264):1732–1733.

- Kumar Agrawal A, Arora PK, Nafees M, et al. Assessment of health infrastructure in tackling COVID-19: a case study of European and American scenario. Mater Today Proc. 2021. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.01.916

- Tabery J, Mackett CW 3rd. Ethics of triage in the event of an influenza pandemic. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(2):114–118.

- Bielicki JA, Duval X, Gobat N, et al. Monitoring approaches for health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(10):e261–e7.