ABSTRACT

This study examined housekeeper referral agencies’ operations in Japan, their services, and fee standards. This promoted an estimation of the standard price of housekeeping services in Japan if insurance coverage was excluded. Questionnaires were distributed to 399 housekeeping agencies whose addresses were available on the website of the Japan Association of Nursing and Welfare Placement Agencies as of October 2022, and 101 agencies responded (response rate: 25.3%). Surveys were completed in February–March 2023. Two-thirds (65%) of the housekeeper placement agencies had a long-term care (LTC) insurance office. Housekeeper referrals were mostly for 1–4 h; the fee varied according to city size and service provider type, which tended to be higher in larger cities. The fees were lower for attached LTC providers than for stand-alone providers. Most managers (60%) of housekeeper referral agencies rated their fees as ‘somewhat low’ or ‘very low’, requesting an increase in users’ burden and housekeepers’ compensation. LTC insurance keeps the prices of services provided by housekeeper referral agencies low. In the future, daily living support services for the lightly insured may be excluded from LTC insurance coverage in Japan, and the demand for housekeeper agencies’ services is expected to increase.

Introduction

This study examines the operational status of housekeeper employment agencies in Japan, their service content, and fee standards. The goal is to compare the prices of services provided by housekeeper employment agencies with the official prices of home-helper long-term care (LTC) physical care and lifestyle assistance services in the LTC insurance system. This study predicts the future cost of home-helper services for those with minor care needs (LTC care level 1/2) in a scenario in which LTC insurance does not cover the use of home helpers, thus determining the out-of-pocket burden.

The background to this study is the difficult financial situation of LTC insurance in Japan [Citation1]. Launched in 2000 with a 3.6 trillion-yen budget, the LTC insurance system’s budget reached 10.5 trillion yen by 2022. Financed half by insurance premiums and half by taxes, the budget expansion directly impacts social security costs. In 2017, services for people with mild needs were transferred to local authorities. The transfer of home-helper services for the moderate to local authorities is still a matter of debate, although it is likely to be realized in the future [Citation2].

The prediction draws on the UK’s ‘self-funder’ concept [Citation3,Citation4].Footnote1 Although comparisons between the UK’s National Health Service and Japan’s social insurance must be undertaken cautiously, Japan’s LTC insurance, administered municipally with 50% national treasury subsidy, already excludes certain services. A phased ‘means test’ may encourage self-funding, driven by the LTC insurance’s estimated increase from 11.2 trillion yen in 2023 to 24.6 trillion yen in 2040 (peak ageing rate projection) [Citation5]. To manage this fiscal situation, home-helper LTC for those with medium needs might separate from LTC insurance. Three scenarios include (1) local authorities bearing the financial, (2) unpaid family care, and (3) private companies providing services. I believe that scenario (3) is the most reasonable prediction. This study reveals older housekeeping agencies in Japan, some affiliated with LTC insurance providers. They are potential service providers for ‘self-funded’ service users.

The fee structure of housekeeper employment agencies slightly varies among providers; it typically includes ‘housekeeper remuneration’, ‘housekeeper employment agency referral fee’, and ‘necessary expenses like transportation’. Users usually pay the housekeeper directly, who then compensates the agency. Unlike housekeeping services, there is no formal employment relationship between the housekeeper and users/referral agencies. While an employment contract exists between the user and housekeeper in a housekeeper employment agency, it is legally interpreted as a family contract exempt from labour-related laws and regulations. This lack of legal protection for housekeepers sparks debates on potential legal revisions.

Contrastingly, the LTC insurance remuneration system outlines a ‘basic remuneration’ for each service (e.g. home helpers and day-care centres). For instance, an hour of ‘physical care’ by a home-helper results in 579 credits of remuneration, with each credit equivalent to approximately 10 JPY. Additional credits, increase remuneration received based on specific conditions like work experience, qualifications, and staff training implementation.

Certain housekeeper employment agencies are now designated as LTC insurance providers. Besides them, providers offering home-helper LTC (physical care and living assistance) under the LTC Insurance Act have emerged. Unlike medical insurance, Japan’s LTC insurance permits mixed use of services that are covered and not covered by insurance. Monthly usage is capped according to LTC level certification, and covered activities are limited (e.g. walking, shopping other than for daily necessities, etc.), positioning Japan’s LTC insurance as a subsidy for declining physical abilities rather than comprehensive support for the lifestyles of older adults.Footnote2

Literature review

Previous research on housekeeper placement agencies in Japan has focused on historical aspects [Citation6]. Historical research clarifies home-helper LTC development up to LTC insurance, but surveys on current prices are scarce. A new survey is needed to understand current fee standards of housekeeper employment agencies and providers’ circumstances.

shows the organization of similar services. Only home helpers are LTC-insured; housekeeping employment agencies are privately funded. Physical care services are provided by home helpers and housekeeper employment agencies, whereas housekeeping services focus on assistance.

Table 1. List of characteristics of home helpers, the housekeeper employment agency, and housekeeping services.

Both the implementation of LTC insurance and the use and supply of home-helper (physical care/lifestyle assistance) services are increasing. However, the content and expertise of these services have always been the subject of controversy. The primary goal of home-helper LTC insurance is to promote ‘individuals’ physical independence’ through home care and housekeeping. Services that are not suitable for this purpose, such as shopping, cleaning other than the older adult’s living room, and laundry that does not belong to the older adult, are restricted. Further, LTC insurance sets a monthly usage limit according to everyone’s LTC level. Therefore, the current circumstances of housekeeper employment agencies being used to supplement the shortfall in LTC insurance usage limits have already been indicated [Citation7].

An overview of public LTC insurance in Japan is provided by Yamada and Arai [Citation1]. The current aims are (1) How do home care services affect the health status of the elderly and their family members who care for them? (2) How does the increased cost burden of home care services affect household finances? Calvó-Perxas and colleagues [Citation8] compared the health status of carers providing at-home care in 11 European countries when the use of home care services is reduced. They found that although respite care and carer benefits (cash payments) are the most effective measures to maintain carers’ health, their effectiveness varied. This suggests that support systems for home care are strongly influenced by country-specific conditions. Marukawa [Citation9] also estimates that Japanese workers have reduced their workload by 2% to care for family members, and estimates that if the current situation continues, 3.9% of the workload will be reduced for care in 2065. Tsuchiya-Ito and colleagues [Citation10] investigated how household income affects at-home rehabilitation. They found that while low-income groups used more home help services, they spent less than middle/high-income groups. This indicates that the Japanese LTC insurance system provides financial support to low-income groups. Sano and colleagues [Citation11] acknowledged that an increase in public LTC insurance user fees would bring financial stability, but note that it may discourage the use of home help services. summarizes this relevant literature.

Table 2. Literature review of housekeeper referral agencies and public long-term care insurance in Japan.

Novelty and originality of this study

No studies have examined the relationship between the housekeeper referral agencies and the public LTC insurance agencies that this study investigates. The services provided by both are similar. However, most of the research has been into public LTC insurance, and researchers have not focused on housekeeper referral agencies, which are self-funded services. The uniqueness of this study is therefore that it bridges these two services and compares the relationship between the public LTC insurance system and housekeeper agencies.

Method

The research objectives are to (1) understand the percentage of housekeeper referral agencies that are affiliated with LTC agencies; (2) analyse pricing structures for various services offered by both independent and LTC-affiliated agencies; (3) assess the impact of provider type and city size on service prices, and (4) gauge housekeeper agency owners’ evaluations of current service pricing. The insights gained will aid in preparing for potential challenges, such as a decline in Japanese LTC insurance system finances, reduced coverage for home-helper LTC, and the emergence of ‘self-funders’ who provide out-of-pocket at-home support.

Research design

This study employed a cross-sectional design.

Selection method and data collection

The survey instrument for this study was developed by the author. The survey questionnaire was distributed to 399 housekeeper employment agencies whose addresses were listed on the website of the Japan Association of Nursing and Housekeeper Employment Agencies as of October 2022. The Japan Care and Housekeeper Employment Agency Association is the largest organization to which housekeeper placement agencies in Japan belong, and the list used in this survey is close to the population of housekeeper placement agencies in Japan. However, the Japanese housekeeper placement agencies have ageing managers, and I felt that an online form-based survey would not be suitable.

Surveys were administered and collected from February–March 2023. Knowledge Data Service, Inc. was responsible for sending, collecting, and entering data for the survey questionnaire, and the dataset was delivered to the author for subsequent data cleaning and analysis.

A total of 101 questionnaires were returned (response rate: 25.3%). Three were excluded from the analysis because they were not matched. The missing values for each questionnaire item were retained using regression assignment methods with other continuous variables. Categorical variables were treated as not applicable.

Survey topics

The principal objective of this study was to analyse the cost structure associated with each service dispensed by the Housekeeper Employment Agency, encompassing nursing care, housekeeping, and attendant services.

The survey items included the following items in June 2022: ‘number of hours of use less than 1 h’, ‘number of hours between 1 and 2 h’, ‘number of hours between 2 and 4 h’, ‘number of hours between 4 and 8 h’, ‘number of hours of use over 8 h (day shift)’, ‘number of hours over 8 h (overnight stay)’, ‘3 h each for nursing care, domestic help and escorting’, and the approximate fee for 3 h of use.

Concurrently, this study appraises the prevailing pricing structure from agency managers’ standpoints. Managers within the Housekeeper Employment Agency were solicited to assess the current prices, reflecting both their clients’ and workers’ perspectives, a procedure denominated in this context as ‘price evaluation’. The factors potentially influencing this price determination and subsequent evaluation are delineated by the categories of ‘city size’, ‘type of establishment’, ‘employment of non-family members’, and ‘office ownership’.

The variable ‘city size’ discriminates between ordinance-designated cities and non-ordinance-designated cities, as per the criteria defining large urban areas in Japan. The ‘type of establishment’ differentiates between offices incorporated within the LTC insurance system and those operating as independent referral offices. An inquiry into the ‘employment of employees other than family members’ seeks to ascertain whether the proprietor and immediate family (mainly the spouse and children) engage any personnel outside the familial circle. Finally, the ‘office ownership’ item probes the utilization of the owner’s residence as a functional office. As the purpose of this survey was to determine the current state of housekeeper referral agencies, only descriptive statistics were used, and no predictive models of any kind were developed from the dataset.

Statistical analysis

Collected data were analysed using R (version 4.3.0). Frequency analysis and descriptive statistical analysis were conducted to identify the general characteristics and main research variables of the targeted offices. The main study variables were ‘size of city’, ‘type of establishment’, ‘non-family employment’, and ‘ownership of establishment’, with 95% confidence intervals compared. In recent years, it has been recommended that p-values not be displayed in t-tests to avoid intentional manipulation (p-hacking). However, I believe that this trend has not been fully established and therefore p-values are displayed for reference purposes.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kyoto Prefectural University (no. 2022-265). Returning the survey was deemed consent to participate.

Results

Status of housekeeper employment agencies

According to the sample of housekeeper employment agencies obtained in this survey, there were 63 (64.3%) co-located LTC insurance provider types (‘LTC co-located types’) and 34 (34.7%) stand-alone housekeeper employment agency types (‘stand-alone types’). Additionally, 39 (39.8%) housekeeper employment agencies were in ordinance-designated cities and 59 (60.2%) in non-ordinance cities. Reasons for why clients used housekeeper employment agencies were as follows: ‘services not covered by LTC insurance’, 45 agencies (46.8%); ‘shortage of service fees with LTC insurance’, 32 agencies (33.3%); ‘long-term continued use’, 14 agencies (14.6%); and ‘other’, five agencies (5.2%; ).

Table 3. Descriptive information about housekeeper employment agencies (N = 98).

A cross-tabulation of the type of management of the housekeeper referral agency (LTC-affiliated or stand-alone) and whether it was family-owned or non-family-owned, and a chi-squared test showed that the stand-alone type was significantly more common in family-owned agencies ().

Table 4. Cross-tabulation table for family or non-family-owned businesses and office type.

Three-hour usage prices according to housekeeper employment agency services

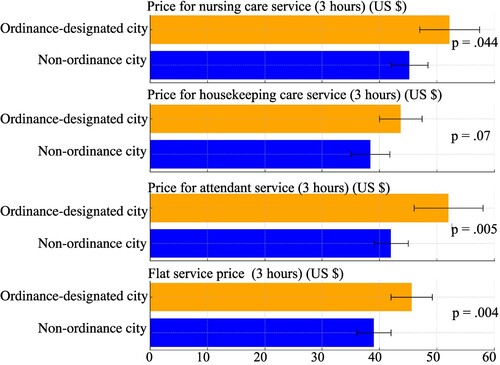

The prices of the services provided by housekeeper employment agencies are divided according to the following categories: ‘LTC: aspects involving physical care’; ‘housekeeping: lifestyle assistance, such as cooking, laundry, and cleaning, that does not involve physical care’; ‘attendant: support for going out, such as to the hospital’; and ‘uniform: no price differences for each service’. Participants were then asked about the three-hour usage price. The services mediated by referral agencies are available for use for less than one hour to eight hours or more (including overnight stay), but the most commonly used ones were as follows: for the LTC co-located type, use of more than one hour but less than two hours (34.0%) and use of more than two hours but less than four hours (33.6%); and for the stand-alone type, use of more than one hour but less than two hours (32.6%) and use of more than two hours but less than four hours (49.2%; ).

Figure 1. Comparison of volume zones of hours of use between long-term care co-located and stand-alone type.

Based on these data, it was assumed that the volume zone of services of housekeeper employment agencies was approximately three hours, and the standard price was set as the three-hour usage price. The three-hour standard is also consistent with research findings that family caregivers ‘who are completely free from caregiving for three (or more) hours a day are less likely to feel the caregiving burden than those who are not’ [Citation10, p. 10], even after statistically controlling for confounding factors. This is a good guideline for use as a home care service. This price includes a referral fee (mean value: 19.2%), which is the profit of the referral agency.

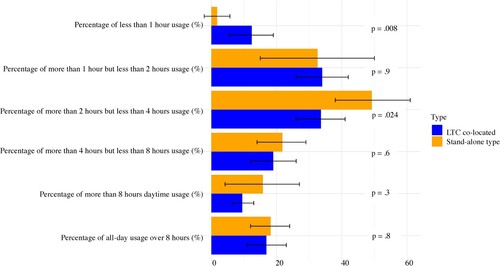

Three-hour rates for each service were plotted for each city (). Rates for physical care services, housekeeping services, and escort services tended to be higher for offices located in ordinance-designated cities.

Evaluation of the current price of housekeeper services

Owners are positioned between housekeeper employment agency workers and users, and it is believed that they can evaluate both. Housekeeper employment agency owners were asked how they evaluated the ‘current price of housekeeper services’ from the perspective of ‘housekeeper reward’ and ‘housekeeper service fees’ (). No significant differences were found in their evaluation of ‘housekeeper compensation’ and ‘housekeeper service fees’.

Table 5. Evaluation of housekeeper service prices by housekeeper employment agency owners (N = 98).

A total of 61.2% of the owners answered that the current price of the housekeeper service was ‘somewhat cheap’ (54%) or ‘very cheap’ (7.2%), while 37% of the owners answered that the price was ‘reasonable’. Higher prices for housekeeper referral agencies would increase referral fees and profits for referral agencies.

Continued prices for housekeeper employment agency services

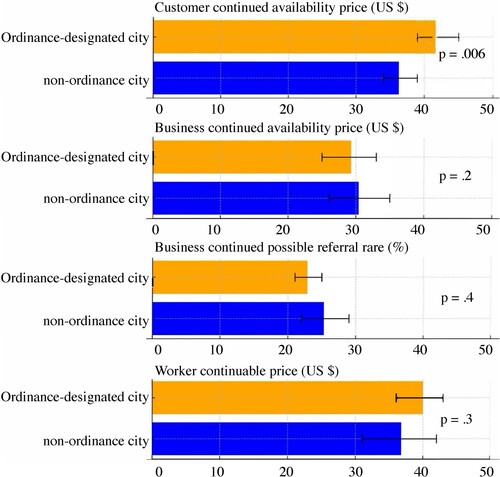

The following three items were asked of housekeeper service providers regarding the price of service and referral rate: ‘the price per three-hour period at which the average client can continue to use the housekeeper’, ‘the referral rate at which the provider can continue to provide a stable service’, and ‘the price per three-hour period at which the housekeeper service is needed to keep the housekeeper working’. plots the confidence intervals for each variable by city size.

Figure 3. Confidence intervals for the estimated sustainable price of service user, business, and worker service use by city size.

Managers of housekeeper employment agencies in large cities tend to believe that their clients can afford to pay more than the current price. However, there is no significant difference from the current price, indicating that the managers of housekeeper employment agencies find the current price reasonable. Further, 23.7–25.7% of respondents desire an introduction fee that would enable them to provide stable services in the future, which is higher than the current price of 18.7–19.7%, suggesting their preference for a higher introduction fee than the current price.

Discussion

This study estimates that the price of housekeeper employment agency services remains cost-effective owing to the impact of LTC insurance, particularly for the LTC co-located type. In 2023, the home-helper remuneration under LTC insurance for 3–3.5 h of physical care was approximately 9150 Japanese yen (579 + 4 × 84 = 915 credits) or $61 USD (1US$ = 150 JPY). Assuming a user burden of 10%, this translates to $6.

The private usage fee is 5.5–6.1 times the user burden (estimated at $6 for using a home helper for three hours) for the co-located type and 5.3–7.9 times for the stand-alone type. This trial calculation indicates that the housekeeper service price, which would be $61 for private use, is suppressed at approximately 21–45% owing to the LTC insurance system. If housekeepers through LTC insurance are available at 10–20% of the market price, the total number of users willing to pay the full cost may decrease.

According to the February 2023 LTC benefit cost statistics, the annual cost for home helpers with LTC insurance is 924 billion JPY for all levels of care and 299 billion JPY for 1/2 level of care. When limited to daily living assistance, the cost would be 21.5 billion JPY for those requiring nursing care 1–5 level of care, and 11.9 billion JPY when limited to those requiring 1/2 level of nursing care. This 11.9 billion JPY is a small amount compared with the total cost of LTC benefits, which exceeds 10 trillion JPY; however, if this amount is to be cut every year, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare – which is struggling with ballooning LTC insurance finances – will have no choice but to cut back.

Even if LTC insurance reduces coverage, the demand for LTC services will create a new market for housekeeping employment agencies. The 12 billion figure will have little financial impact on the overall LTC insurance market; however, it will create a new market for housekeeping employment agencies.

The crucial issue is whether older adults and families, accustomed to a 10% LTC-insured basis, will use housekeeper employment agencies if costs rise ten-fold owing to private funds. If LTC becomes unavailable, the home care environment for older adults will deteriorate, increasing the burden on family care. This could lead to a deterioration in the physical and social conditions of older adults, possibly requiring more extensive care and a return to insurance services. The rising burden on family caregivers may result in workforce exits, particularly affecting women (in Japan, the wage gap between men and women is large, and it is estimated that most of the people exiting are women), leading to increased poverty in homecare families and exacerbating labour shortages in the market [Citation12]. Additionally, decreased use of formal services tends to increase unpaid family caregiving, negatively impacting caregivers’ physical and psychological health [Citation13].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Housekeeper referral agencies and their impact on family caregivers should have been included [Citation12] including discussing how public LTC insurance in Japan impacts family caregivers’ employment. Unfortunately, this study did not examine the impact of housekeeper services on family caregivers. Further, this study lacks clear evidence to compare the unit cost of home help services in the LTC insurance system with those of housekeeper employment agencies. LTC insurance’s short-duration usage (30 min to 1.5 h) contrasts with housekeeper services, primarily used for 3 h, making the 1-hour period relatively expensive. Future research should establish criteria for a more accurate comparison of these services. Additionally, the survey collection rate was lower than expected, likely introducing bias owing to the insufficient sample size. This may be attributed to the busy schedules of housekeeper referral agency management, often older adults with limited survey response capacity. This speculation will be reflected in future survey designs.

Conclusion

Although housekeeper employment agencies provide low-cost complements to housekeeper LTC services, they may be affected by price dumping by the LTC insurance system. Exempting LTC for housekeepers from insurance coverage for the 1/2 level of LTC required would have negligible impact on improving LTC insurance finances, but many current housekeeper agencies are small and do not have the human resource capacity to meet the demand for 12 billion JPY that would be exempted from insurance coverage. If LTC for home helpers is excluded from insurance coverage for the 1/2 level of LTC required, the amount paid by service users could be approximately 10 times higher than the current level. If this price impact causes users to curtail their use of services, it will have a significant negative impact on the homecare environment for older adults, working environment, and lives of family caregivers [Citation13]. I plan to conduct an additional future survey of housekeeper referral agencies to determine changes in the use of homecare services following changes in Japan’s LTC insurance system.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI under grant JP21K01977. The Knowledge Data Services Corporation (kdsv.jp) provided support for mailing the survey, tabulation, and input.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Naruhisa Nakane

Professor Naruhisa Nakane, Faculty of Industrial Sociology, Ritsumeikan University. Ph.D. (Sociology) Disability studies, clinical sociology and welfare sociology are my fields of specialisation. In Japan, I am working on information on benefits under the Comprehensive Support for Persons with Disabilities Act, analysis of the use of disability welfare services, and database analysis.

Notes

1 In the UK, older adults with a certain amount of assets cannot receive social care service fees from the NHS (they can receive the fees again if the value of their assets falls below the threshold due to the use of services). Older adults who experienced so-called ‘dismissal from the system’ are no longer subject to government surveys, and it becomes difficult to determine their actual circumstances [Citation4].

2 It has been 23 years since the introduction of LTC insurance in Japan; however, it is difficult for providers to achieve economies of scale and secure profits compared with services that provide group support, such as special nursing homes for older adults and day services. Home helper providers are labour-intensive businesses that cannot provide services if helpers cannot be hired. Many home helpers are middle-aged and older female workers, and employment mobility is high. Changes in the employment environment in other industries have a large impact. As of 2023, the most serious labour shortages among LTC insurance services are for home helpers, and some providers go bankrupt because of labour shortages.

References

- Yamada M, Arai H. Long-term care system in Japan. Ann Geriatric Med Res. 2020;24(3):174–180. doi:10.4235/agmr.20.0037

- Ministry of Finance of Japan. Fiscal in historical transcription [Internet]. Reference Material for the Council on Fiscal Institutions 2023 (3). Japanese. Available from: https://www.mof.go.jp/aboutmof/councils/fiscalsystemcouncil/sub-offiscal_system/report/zaiseia20230529/zaiseia20230529.html#:~:text=%5D%0A(3)%5B-,PDF,-%5D

- Baxter K, Wilberforce M, Birks Y. What skills do older self-funders in England need to arrange and manage their social care? Findings from a scoping review of the literature. Br J Soc Work. 2021;51:2703–2721. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcaa102

- Henwood M, Glasby J, McKay S, et al. Self-funders: still bystanders in the English social care market. Soc Policy Soc. 2022;21:227–241. doi:10.1017/S1474746420000603

- Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy, Cabinet Office [Internet]. Future prospects for social security looking ahead to 2040 (discussion material). Summary; 2018. Japanese. Available from: https://www5.cao.go.jp/keizai-shimon/kaigi/minutes/2018/0521/shiryo_04-1.pdf

- Saso T. Relationship between home service worker system and housekeeper system in Japanese home helps: focusing on trends in the actual conditions of the bearers of both systems and changes in target areas. Soc Welf. 2017;58:1–12. Japanese.

- City of Sapporo. Report of the questionnaire survey on the actual provision of services outside long-term care insurance in fiscal year 2015; 2016. Japanese. Available from: https://www.city.sapporo.jp/kaigo/k100citizen/documents/jittaityousahoukoku.pdf

- Calvó-Perxas L, Vilalta-Franch J, Litwin H, et al. A longitudinal study on public policy and the health of in-house caregivers in Europe. Health Pol. 2021;125(4):436–441. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.02.001

- Marukawa T. The demand for and supply of elderly care in Japan. Jpn Polit Econ. 2022;48(1):8–26.

- Tsuchiya-Ito R, Ishizaki T, Mitsutake S, et al. Association of household income with home-based rehabilitation and home help service utilization among long-term home care service users. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:1–16. doi:10.1186/s12877-020-01704-7

- Sano K, Miyawaki A, Abe K, et al. Effects of cost sharing on long-term care service utilization among home-dwelling older adults in Japan. Health Pol. 2022;126(12):1310–1316. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.10.002

- Fu R, Noguchi H, Kawamura A, et al. Spillover effect of Japanese long-term care insurance as an employment promotion policy for family caregivers. J Health Econ. 2017;56:103–112. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.09.011

- Miyawaki A, Kobayashi Y, Noguchi H, et al. Effect of reduced formal-care availability on formal-informal care patterns and caregiver health: a quasi-experimental study using the Japanese long-term care insurance reform. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:207. doi:10.1186/s12877-020-01588-7