Abstract

John Henry Wigmore’s life experience as a Westerniser teaching Anglo-American Law in Japan from 1889 to 1892 is an example of legal orientalism. Engaging in the historical study of Japanese law despite diverging cultural paradigms between East and West paradoxically revealed striking similarities leading to the publication of the Materials for Study of Private Law in Old Japan in 1892. More than three decades after his return from Tokyo sparking a lasting fascination for foreign and comparative law, Wigmore published in 1928 A Panorama of the World’s Legal Systems. This case study offers insights on the relationship between legal history and comparative law that these publications respectively represent. The imprecise classification of A Panorama at a time when comparative law was at its infancy stage requires identifying a relevant taxonomy. Wigmore’s legacy is revisited with a focus on both its historical and comparative dimensions.

I. Wigmore and the ‘Land of the Rising Sun’: revisiting orientalism through the experience of a late nineteenth-century legal Westerniser

Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,

Till Earth and Sky stand presently at God’s great Judgment Seat;

But there is neither East nor West, Border, nor Breed, nor Birth,

When two strong men stand face to face, though they come from the ends of the earth!

Rudyard Kipling, The Ballad of East and West. (1889)Footnote1

1. The spell cast by ‘comparative law’ on the young Wigmore

John Henry Wigmore (4 March 1863 to 20 April 1943), eldest of seven children, was born in San Francisco. Privately educated, he moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts with his entire family to attend Harvard University (AB, AM in 1883–84).Footnote2 Shortly after his graduation with LLB from Harvard Law School in 1887, he joined the bar and practiced in a Boston firm for about two years before setting out to sail to Japan in 1889 at age 26 on recommendation of Charles William Eliot, the then incumbent and longest-serving President of Harvard University, although warned by Eliot of poor prospects upon return for a scholar willing to pursue an academic career in comparative law at the time.Footnote3 Wigmore mostly remains known to posterity as a leading scholar in the field of evidence. Especially to the more municipally minded lawyers very familiar with his magnum opus, A Treatise on the Anglo-American System of Evidence in Trials at Common Law (1904–1905) which constituted an authoritative landmark and reference for multiple generations of practitioners. Yet an arcane aspect of his peregrinations, which is of particular interest to legal historians, was his early residence in a country in East Asia undergoing a rapid industrialisation accompanied by a radical political overhaul with profound institutional and cultural reforms modelled on Western nations and aimed at bridging their gap.

In the addendum to the preface of the Evolution of Law entitled Sources of Ancient and Primitive Law, Wigmore revealed his ‘sentimental interest’ in ‘returning to the science of [his] early hopes’ following his three-year sojourn in Tokyo.Footnote4 Wigmore expressed his attachment to Japan in various occasions including in his A Panorama which reads ‘[m]any years ago, while living in Japan, I came under the spell of what is called comparative law’.Footnote5 In a late article, nearing his seventies, he maintained his undispellable enchantment and profound fascination for the study of comparative legal ideas since the time he taught law in Japan where ‘the comparative point of view naturally emerged’.Footnote6 Still according to Wigmore’s recollection some 25 years after his return to the US, Japanese institutions ‘point for point, showed parallel legal ideas, and sometimes (amidst influences totally independent) a striking similarity of development with the Occident’ leading him to study these ideas from the (implicitly) ‘comparative point of view’.Footnote7 Thus when Wigmore affirmed comparative law ‘may preferably be named universal legal ideas’ noting a ‘striking similarity of development with the Occident’ of old Japanese law, was this the result of an orientalist outlook impregnated with ethnocentrism or even imperialism? It is no secret that unification or harmonisation constituted an early hope in the field and were still considered functions of comparative law based on universalist assumptions in the 1970s.Footnote8 Wigmore and his contemporaries promoted the idea of universal law and jurisprudence but many subsequent scholars have successfully dismissed these assumptions.Footnote9

Before turning to the next section on the relationship between comparative law and legal history (Section II), some background information is offered on Wigmore’s early and relatively brief time in Japan considering his demanding teaching duties (Subsection 2). Then the notions of intellectual and epistemological orientalism pervading many areas of knowledge are introduced (Subsection 3). Finally the propensity of orientalism in his work on Japanese legal history is considered (Subsection 4).

2. The ‘Japanese connection’

This subtitle is borrowed from one of Wigmore’s successors to the Northwestern Law School’s deanship, Professor Kenneth Abbott, who referred to this chapter in Wigmore’s life as the ‘Japanese connection’.Footnote10 Regardless of President Eliot’s warning on the meagre prospects of an academic career in comparative law upon return, ‘Harry’ packed his luggage, married and embarked.Footnote11 Cautious to make a good impression on his hosts, it was not without a meticulous preparation which epitomises his character that he learned basics of Japanese, ‘read every page of the English-language Japanese newspaper from the preceding twenty years and read all the [US] diplomatic correspondence with Japan since Commodore Perry sailed into Edo Bay some forty years before’!Footnote12 Wigmore was keen to prepare thoroughly for any important event and especially a visit abroad. He saw self-development as a sign of respect and etiquette. Visiting another country was always preceded by a linguistic preparation of about one or two years prior to departure on account of letters from his personal secretary who accompanied him from 1919 until his very last days in 1943.Footnote13 This mindset was confirmed some years later as he attended Northwestern’s School of Speech early in his academic career and later introduced a speech course to the law curriculum.Footnote14 As one may expect, he did not haphazardly sail through the Pacific Ocean to an entirely alien land – which would have potentially made his task exponentially more difficult.Footnote15

The Meiji Restoration movement initiated the industrialisation of Japan in 1868 as a result of the collapse of the Tokugawa Shogunate regime that had been in power since 1603. Wigmore was called in to assume his functions by Fukuzawa Yukichi, a leading Japanese Westerniser who founded Keio University in Tokyo in 1858, a decade prior to the formal beginning of the Restoration period and three decades prior to Wigmore’s arrival. According to Annelise Riles, Wigmore belonged to the ‘second generation of foreigners hired by the Meiji government – so-called “yatoi” (foreign menials) brought in after 1866 to Westernize all aspects of Japanese society’.Footnote16 I believe that Wigmore’s advent should not be characterised as a colonial envoy although he was expressly expected to act as a Western proselyte by his host ‘for the Japanese have always been only too clever at imitation’.Footnote17 Thus, appointed as a Professor of Anglo-American Law, he was the only full-time teacher in this subject at Keio. This entailed a complete freedom to choose the substance and manage his teachings.Footnote18 As Riles noted, Wigmore’s assignment was to prepare the ‘training of the next generation of Japanese lawyers – and hence he was free to turn to less applied and more scholarly forms of inquiry’.Footnote19 As indicated, his visit to Japan lasted three years. The drastic increase in his teaching hours and perhaps his desire to return to his homeland was followed by his appointment as Professor of Law at Northwestern University Law School in Evanston, Illinois in 1893.Footnote20 His departure was certainly not the desire of an otiose spirit. Indeed, this would be a totally undue inference.Footnote21

During this short stay in Japan, quite surprisingly for an US jurist who tended to be navel-gazers, he simply refused to live the life of a presumptuous, western propagandist and combined his newly acquired teaching status with the humbler one of student. Concomitantly to his heavy teaching duties, he successively edited the Notes on Land Tenure and Local Institutions in Old Japan in 1890 and the Materials for Study of Private Law in Old Japan in 1892. The Materials are interesting in many respects. Before discussing their merits, it seems important to note that he also published the same year an article on ‘The Legal System of Old Japan’ in which he summarily explained, ‘it is in Japan that we may find the extreme antithesis to the [English speaking] conception of justice’ with a distinctive feature ‘to make justice personal, not impersonal’ despite the presence in Japan of ‘a legal system, a body of clear and consistent rules, a collection of statutes and of binding precedents’.Footnote22 Abbott later recalled:

a man who was a preeminent scholar in the law of his own land, but whose mind was also ‘directed toward a wider vision’, who thought about the law and legal problems on a global scale. Wigmore’s early Japanese connection certainly contributed to the formation of this world view, but his own intellectual instincts led him to maintain it throughout his life.Footnote23

This first glimpse into a legal tradition foreign to Wigmore, however, did not make him a comparatist yet. Indeed, as Roscoe Pound noted in his idiosyncratic style, ‘[s]tudy of the common law followed by study of the civil law does not constitute study of comparative law’ and in the same vein Konrad Zweigert and Hein Kötz considered ‘the mere study of foreign law falls short of being comparative law’.Footnote26 However, this experience was indeed a necessary milestone and a foundation for his later, more comprehensive encounter with some additional legal traditions of the world (see Section II). Since the study of Japanese legal history has been undertaken by a Western scholar in circumstances revealing cultural and linguistic alienation, did Wigmore’s training in the common law tradition constitute an additional difficulty in his ability to transliterate with exactitude Japanese legal doctrines and institutions?

3. Intellectual and epistemological orientalism: a short introduction

Abbott commented in his belated tribute, ‘[i]t is ironic that Wigmore, brought to Japan by a leading Westernizer to teach Western law, made his greatest contribution to the country by helping it to recognize its own legal tradition’.Footnote27 Irony lies, in truth, in this impudent assertion, which is archetypal of the abuses of orientalism, especially since Wigmore’s work consisted mostly of compilation and translation. Indeed, how would translating Japanese law into a foreign language contribute to Japanese enlightenment? This aberration was identified as early as 1924 by René Guénon who was able to discern the characteristics and weaknesses of orientalism adversely affecting the tenuous relationship between Orient and Occident. Guénon thus raised a severe recrimination against the ‘influence exerted by those of the orientalists’ who ‘act as if called upon to reconstruct vanished civilizations’.Footnote28 The following extract is remarkable for its clarity and is situated in his developments on the ‘Fruitless attempts to bridge the differences between East and West’:

[W]hile displaying a certain sympathy for Eastern conceptions, [some orientalists] wish at all costs to make them fit into the frames of Western thought, which amounts to disfiguring them altogether, and which proves that in point of fact they understand nothing about them. … Evidently, they cannot resign themselves to not understanding, nor help reducing all things to the level of their own mentality, thinking the while to do great honor to those whom they are crediting with these ideas that would be ‘good for children of eight’.Footnote29

the decades after 1868 in Japan were one of the most remarkable periods in recent history, and they were of special interest to lawyers: the Japanese legal system was being thoroughly revised on Western models in an effort to convince the Western powers to terminate the treaties granting them jurisdiction over their nationals within Japan.Footnote30

This translation and editing project gave birth to the Materials for Study of Private Law in Old Japan published in 1892 shortly before his return as indicated and was later renamed as Law and Justice in Tokugawa Japan.Footnote36 In broad lines, the Materials were divided into eight distinct parts including an introduction. Interestingly regarding the object of this paper, Wigmore conceived of Old Japanese law entirely within the western structure of the Institutes of Gaius following the summa divisio of persons, property and actions. Indeed, Parts II – IV dealt with Contract, Parts V – VI with Property and finally, Parts VII – VIII with Persons. The first of either of these two parts dealt with ‘civil customs’ while the second part with ‘legal precedents’ except for a supplementary Part IV on contract concerned with ‘commercial customs’. Parts I, II, III (Section 1), and V were published in 1892 while the other parts were in preparation and only completed by Wigmore’s successors.Footnote37 An interesting quote is offered in the opening of Part I of the Materials according to which comparative legal science teaches, on the one hand, ‘how nations having a common origin may develop independently their original inheritance of legal ideas’ and on the other hand, ‘how the legal systems of nations having no association in history may advance along common lines of development’ and thus:

[i]nvestigations carried on in the region of a single system serve to smooth the path for the advent of comparative legal science. Each enlargement of our view, each addition to our available material, is a gain of the greatest moment for that science.Footnote38

4. Legal orientalism: perspectivism and prejudice in legal thought

If philosophical and metaphysical considerations can be particularly affected by the orientalist prejudice, the situation is no different for law. Orientalism is no stranger to the field – although the terminology was only more recently coined by Teemu Ruskola.Footnote39 Obviously, this outlook preceded this author and the likes of Edward Said to signify an attitude concerned with exotic, mystical and mythical representations of the East by Western literature and arts. Accordingly, notions of ethnocentrism and imperialism are akin to orientalism and are also encountered in law. Imperialism, according to Geoffrey Samuel, consists in the ‘imposition, via a universal theory, of a definition fashioned in one legal culture on the law of another culture [which] may simply obscure rather than highlight this other culture’.Footnote40 Imperialism can take many forms: cultural, economic, epistemological, ideological, intellectual, juridical, legal or social. Ruskola defined legal orientalism as a ‘discourse [which] entails the projection onto the Oriental Other of various sorts of things that “we” are not’.Footnote41 It seems prima facie that the two notions of imperialism and orientalism could be easily conceived as partially interchangeable. Imperialism being geographically neutral as it does not refer to a specific area of the globe is consequently of a more general ambit and on a purely theoretical level, subject neutral. In orientalism, the observing subject would be necessarily a Westerner projecting their views on their Oriental counterpart. I disagree with the views of Ruskola, who seemed to welcome a broad range of approaches in a special issue of the Journal of Comparative Law. The intent here is certainly not to dispute his scholarly integrity. Ruskola’s most significant contribution to scholarship being legal orientalism, his attachment to the term is understandable.Footnote42

It could be objected that to consider Wigmore as a legal orientalist would be anachronistic. Only the term is, not the idea. Furthermore, this observation does not preclude from examining his tendencies in that respect. Riles observed that ‘[l]ike most of his fellow citizens, Wigmore believed that the West, as “Japan’s adopted parent,” had much to teach, and that the Rule of Law should be first among these lessons’.Footnote43 The patent inequality resulting from such presumption confining to overt infantilism is characteristic of the belief in superiority Westerners have over their ‘Oriental’ counterparts, despite the fact that the Japanese rulers were gladly receiving foreign transplants in all aspects of their society. Therefore, if the imperialistic mindset could be attributed to Wigmore concerning his approach to Japanese law, it was contrary to the liberal conception of imperialism not ‘imposed’ or forced against the will of the Japanese rulers. In fact, they were generally uninterested in their own legal history as they were forward thinking, looking ahead towards their new future in rupture with their traditional past. Instead of qualifying Wigmore as an imperialist, it seems more accurate to consider him plainly as an orientalist. According to Guénon:

Westerners who have striven to understand the East, with more or less seriousness and sincerity, have only arrived in general at the most lamentable results, because they have brought into their studies all the prejudices that their minds were encumbered with, the more so because they were ‘specialists’, having inevitably acquired beforehand certain mental habits which they could not get rid of … .Footnote44

According to Abbott’s account, Wigmore’s undertaking was to ‘compare the process of legal development in the West with that in Tokugawa-era Japan’.Footnote46 In Abbott’s view, Wigmore ‘thought of law as “legal science”’ and saw Tokugawa-era in Japan as ‘the perfect control group for a scientific experiment. By studying this unique period of legal development, unaffected as it was by foreign borrowings, legal scholarship could approximate “the laboratory methods of natural science”’.Footnote47 On the first point, the comparative nature of Wigmore’s approach to legal history is discussed in the next section (see Section II) as the Materials were purely concerned with Japanese law and a comparison could have been no more than implicit (see Section I, Subsection 2). On the second point, however, the ambitious aim to scientifically study Japanese law seemed to contradict the Japanese practice since the Japanese officials themselves did not bother recollecting their own ‘legal’ texts. Therefore, did the Japanese consider their own legal heritage in a systematic fashion – and ultimately as a source of knowledge or ‘science’ – or were the documents on decisions during the Tokugawa era just scattered materials of little analytical value for them? This is not the place to reconsider the supposed ‘lawlessness’ attributed to ‘Oriental’ countries such as China. A pertinent literature abundantly discusses this area.Footnote48 The corollary question is: did Wigmore extend his scholarly agenda to the old laws of Japan? This question should be considered in light of the Westernising function of Wigmore which occupied the man’s thoughts on a full-time basis at Keio University. Wigmore disclosed the specificities of his study noting that Japanese legal developments were ‘analogous’ and even ‘almost identical’ to European institutions with ‘no possibility of imitation’ as revealed by the findings of a Japanese historian of the old school unable to read English – leading Wigmore to conclude that ‘the problems of the evolution of corresponding legal ideas in independent systems were forced upon the student’s attention. Gustave [sic] Tarde’s great principle of evolution by imitation and transplantation failed completely to explain the phenomenon in Japan’.Footnote49

The student mentioned here was Wigmore himself. If no de facto influence had led to that ‘strikingly almost identical similarity’, was Japanese law analogous to European law or a projection of the Western self onto the Oriental other? Considering European institutions during the Tokugawa era requires distinguishing between the ius commune and post-codification periods, and also common law and civil law for that matter.Footnote50 The way Wigmore structured his Materials suggests that his account of Japanese laws was modelled on remnants of Roman law on which legal ‘development in Europe’ effectively relied, although his reference to the inability to ‘read English’ of the ‘old school’ Japanese historian points to the direction of the English common law Wigmore was more familiar with. Either way, in relation to the object of this paper, Igor Stramignoni identified a ‘vital question for the comparative knowledge of law’ related to the issue of representation referred to as the ‘question of the comparison’. According to Stramignoni, this question considers ‘whether at the heart, at the centre, of all knowledge having the Other as its own object there is not, in fact, a “same” in return which, in any way, precedes and forms what we see from the Other’ and,

if the ever-dominant interpretations of the Other are not strictly bound/abandoned to the anxieties and the historical and cultural memories at the heart, at the centre, of the suggested gazes and if these memories are not especially ‘visual’, that is, if what we know about the Other is not what we ‘see’ at the end of our gaze in return rather than what it is.Footnote51

II. ‘Comparative’ nomogenetics: Wigmore’s input to global legal history

History involves comparison

Frederic MaitlandFootnote52

1. Setting the scene: from Japanese law to the World’s laws

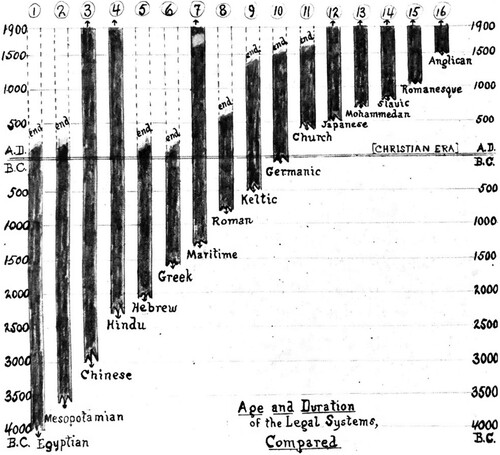

A significant confrontation with aspects of Japanese legal history naturally led Wigmore to further his research into other contemporary and extinct legal traditions, a slightly anachronical term as it was only developed by Pound in the 1930s, but nonetheless a far more pertinent and accurate concept than that of ‘systems’.Footnote53 Wigmore’s most ambitious work in this regard came about more than three decades after his Japanese encounter in 1928 and was boldly entitled A Panorama of the World’s Legal Systems, in which he retraced the evolution of 16 legal traditions past and present: Egyptian, Babylonian (‘Mesopotamian’), Hebrew, Chinese, ‘Hindu’, Greek, Roman, Maritime, Japanese, ‘Mohammedan’, ‘Celtic’, Germanic, Slavic, Ecclesiastical, Romanesque and ‘Anglican’ (common law) ().Footnote54 A further four traditions were subsequently identified some decade later including the Iranian, Armenian-Georgian, ‘Amerindian’ and Madagascan raising the total number to 20.Footnote55 While the terminological inadequacy of Wigmore’s classification of the legal traditions may seem inaccurate if not simply erroneous and misleading to the modern reader for some of these ‘systems’, the outstanding reach of his study is illustrative of both his familiarity with alterity and a frank audacity.

Figure 1. Chart on age and duration of the legal systems, ‘compared’ (Source: John H Wigmore, A Panorama of the World’s Legal Systems, vol 1). Public domain.

A Panorama has been much criticised for its broad generalisations and its accessibility to the lay person in detriment of historical accuracy and rigour.Footnote56 Rather than focusing on vulgarisation and approximation, or amateurismFootnote57 in Wigmore’s work, this contribution is specifically concerned with its ‘comparative’ dimension as the term is understood at present. Hence, a recurrent misconception on comparative law must be dissipated. Comparison necessarily involves the concomitant presence of two or more terms. If these terms are the same object, past and present, such comparison is qualified as historical, pertaining to ‘vertical comparatism’.Footnote58 If these terms are from country A and country B, it is the concern of comparative law, also referred to as ‘horizontal comparatism’.Footnote59 The difficulty to undertake both types of comparisons at the same time as suggested by the compound ‘comparative legal history’ is understandable. Early in the past century, this dichotomy did not seem to have taken roots, at least not effectively, and the focus of works on foreign law were mostly historical (vertical) rather than comparative (horizontal) despite the recurrent use of the latter term. While this certainly has to do with the US ethos in the case of Wigmore, as a result of geographical insularity and the inherently historical nature of the common law tradition, the roots may be deeper.Footnote60 This section of this article seeks to investigate the relationship between both disciplines underlining Wigmore’s historical approach to law and the flaws of its ‘comparative’ dimension.

A brief reference to the prevalent doctrinal conception informing Wigmore’s approach to the study of legal history is considered (Subsection 2). Then the ambiguous relationship between comparative law and legal history is examined in light of the historical dimension of Wigmore’s works (Subsection 3). Finally the comparative nature of A Panorama is revisited according to the contemporary canons of legal scholarship in order to identify a more suitable taxonomy pertaining to this atypical contribution (Subsection 4).

2. Milestones on the history of law informing Wigmore’s doctrinal approach

Two years prior to the publication of A Panorama, Wigmore defined the subject-matter of comparative law by reference to three aspects in a first point on ‘[a]n unconsidered element in the study of Comparative Law’, two of which are especially relevant to this paper.Footnote61 The second and eponymous development of his article ‘A New Way of Teaching Comparative Law’ justified the relevance of visual aids not only in legal history, but also in law in general and pleaded for the use of the visual teaching method in legal studies.Footnote62

This section focuses on legal evolutionism referred to by Wigmore himself as ‘Nomogenetics’ in his first development.Footnote63 Comparative nomogenetics consists in the tracing of the ‘evolution of the various systems in their relation one to another in chronology’.Footnote64 Nomogenetics would be preceded by – although distinct from – ‘Comparative Nomoscopy’, which is another approach to comparative law. Nomoscopy would be concerned with the ‘ascertainment and description of legal systems as facts’ that according to Wigmore had been the quasi-exclusive focus of prior works by his predecessors.Footnote65 This terminology is systematically composed with a unique prefix, the Greek noun ‘nomos’ (νόμος) or ‘law’. Frederick Pollock revealed the origins of such jargon attributed to the prominence of the doctrine of evolution in natural sciences at the time.Footnote66 Such phraseology is characteristic of the nineteenth-century scientism sustained by the belief in the ability of science and reason to solve the ultimate existential dilemmas of humankind. This view was predominant during the International Congress of Comparative Law held in 1900 in Paris.

With A Panorama, Wigmore carried on the seminal findings of his British predecessor, Henry Maine, for whom the former had a pious reverence as he saw in Maine ‘a true apostle of comparative law’.Footnote67 Maine’s pioneering works include Ancient Law: Its Connection with the Early History of Society, and Its Relation to Modern Ideas published in 1861 followed by Village-Communities in the East and West published in 1871. Wigmore’s major writings concerning ‘comparative’ nomogenetics contain regular references to Maine who would be the modern founder of comparative law according to Pollock. The latter dated the birth of the discipline to Maine’s appointment as the first Professor of Historical and Comparative Jurisprudence at Oxford in 1869 and to the founding of the French Society of Comparative Legislation the same year.Footnote68 Before this date, the subject was confined to the particular concerns of a few adventurous scholars. Therefore, this institutional and international consecration occurring on both sides of the English Channel was deemed sufficient by Pollock to officially recognise this ‘new branch of legal science’.Footnote69 For Riles, Wigmore’s early work ‘carefully mimicked that of Henry Maine and his peers’ regarding its ‘historical perspective’ with a ‘unifying theme’ concerned with the ‘relationship between new and old, between “custom” and “law”, between past and present’.Footnote70

Limits to Maine’s work were attributed to limited access to information and a lack of availability of complete materials. Thus, according to Wigmore, the materials were ‘hardly worthwhile’ in Maine’s time but ‘plentiful’ in his.Footnote71 Still in his words, ‘study of each legal system as a whole was not feasible until modern times … unless we believed that we had before us virtually all the actual systems’.Footnote72 Not only were the conditions far more favourable for a grandiose enterprise, but also his conception of the required reach of a ‘proper’ nomogenetical study was critical in his production of A Panorama. Wigmore considered that the narrowly micro-comparative nature of earlier studies was another limitation and deemed an account drawing macro-considerations necessary to fulfil the aims of the newborn ‘science’. Thus for Wigmore, ‘the tracing of the evolution of specific rules and institutions is of course the ultimate aim in comparative nomogenetics’, hence:

this objective needs, for its completion, an auxiliary study of the systems as such, taking each as a whole. Since the individual rules and institutions are bound and related together as the gross product of the social and political life of a particular race or community, their evolution cannot be fully understood without first conceiving the whole system, in its political environment and its chronology.Footnote73

This brief intellectual and sociological background to A Panorama calls into the questioning of Wigmore’s work most observers qualify as comparative law. Was this work genuinely a study pertaining to comparative law or simply global legal history? Furthermore, some preliminary interrogations naturally arise. What would be the relationship between legal history and comparative law? In other words, are these subjects intersecting as suggested by Maitland or heterogeneous? To answer these questions, the historical dimension of Wigmore’s jurisprudential outlook must be examined (Subsection 3) before considering A Panorama’s taxonomy (Subsection 4).

3. Comparative law and legal history: exclusive or symbiotic relationship?

The contributions of Wigmore to US legal history have not only been informed by Maine’s discoveries, but also more generally by the prevalent ideology at the time. The most famous proponent on the European Continent of the historical school of thought predominant in the late nineteenth century would be Friedrich Karl von Savigny. In this regard, Harvard Law School’s former Dean, Pound, and Wigmore’s great friend, correspondent and contemporary parallel,Footnote76 indicated that its ‘method consisted in investigation of the historical origin and development of a legal system and of the institutions, doctrines, and precepts, looking to the past of the law to disclose the principles of the law of today’.Footnote77 In order to have a clearer view of the interplay between comparative law and legal history, it appears necessary to acknowledge first the landmarks informing Wigmore’s approach to scholarship. In this respect, Wigmore officiated from 1907 to 1909 as chairman of the committee producing the Select Essays in Anglo-American Legal History published in three volumes. Kocourek described these as a ‘valuable contribution to historico-legal knowledge’.Footnote78 Wigmore also chaired during 17 years, from 1912 to 1928, the editorial committee producing 11 volumes of the Continental Legal History Series. Interestingly, volume 29 of the Illinois Law Review dating from 1935 saw the article of another great English legal historian, William Holdsworth, Vinerian Professor of English Law at Oxford from 1922 to 1944, taking immediate precedence over John Maxcy Zane’s contemporary tribute to Wigmore as a comparatist. Citing illustrious names such as Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr,Footnote79 Christopher Columbus Langdell, James Barr Ames, James Bradley Thayer and John Chipman Gray along with Wigmore, Holdsworth commented that Wigmore’s originality is the ‘large knowledge which he possesses of foreign systems of law, and the skilful use which he makes of this knowledge to elucidate the history of Anglo-American law … a striking proof of Maitland’s aphorism that “history involves comparison”’.Footnote80

Breaking from the practices of most US comparatists who were ‘mere and modest unsophisticated consumers of legal history’, his productions were landmarks.Footnote81 According to Holdsworth’s observation, Wigmore’s writings on evidence also carried a historical dimension.Footnote82 Perhaps his lasting concern for the subject and the successive editions of his Treatise on Evidence entailed such nomogenetical characteristics. John Zane, author of the most compelling living tribute to Wigmore as a comparatist noted that ‘[a]mong the activities of John H Wigmore as a law teacher and a law writer, none is more interesting than his work in comparative law, considered in the two senses often attributed to that term’.Footnote83 These would correspond to, on the one hand, (vertical) comparison in time or legal history and, on the other hand, (horizontal) comparison in space or comparative law strictly (see Section II, Subsection 1). The first sense of ‘comparative law’ to which Zane refers to is what Wigmore would have strictly described as nomogenetics, without the adjective ‘comparative’, that is, the study of the evolution of institutions or legal traditions. The dichotomy astutely drawn by Zane is fundamental since Wigmore was considered by many as an accomplished legal historian.Footnote84 The second sense of ‘comparative law’ which Zane had in mind is what Zweigert and Kötz later referred to as satisfied by an ‘extra dimension of internationalism’ and is interested in ‘the comparison of the different legal systems of the world’.Footnote85 If this second acceptation of comparative law with a focus on internationalism has become the accepted one today, this was not necessarily common place at the time A Panorama was published – at least, not in practice.

Mathias Reimann – a foremost scholar in the field of comparative law in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century – noted with Alain Levasseur in a paper on the relationship between comparative law and legal history in the US that ‘the former looks at law across space while the latter looks at law across time’.Footnote86 This truism is not without significance since Wigmore seemed to confuse or conflate both. Wigmore himself described A Panorama as pertaining to ‘Comparative Legal History’ – these were the very last words of his book.Footnote87 Unsurprisingly he recommended similar works on the ‘comparative history of law’ such as Maine’s.Footnote88 In the preface of Evolution of Law published a decade earlier, he insisted that ‘these volumes properly will be classified on the side of what is thus, somewhat vaguely, called historical jurisprudence or legal ethnology’.Footnote89 Pound left no place for approximation in this regard and laconically shed some light on this matter summarily dismissing Wigmore’s hesitation. In his words, the ‘investigation and exposition of the actual course of development of a particular legal system is not historical jurisprudence, it is legal history’.Footnote90

The semantic approximation conflating both comparative law and legal history is characteristic of confused thoughts regarding the subject matter at hand. In this regard, while discussing the merits of the endeavours undertaken in each discipline, Reimann and Levasseur could not strictly differentiate between comparative law and legal history, noting that their respective instigators are often the same individuals, and that each study would be inclusive of the other compartment with a different emphasis.Footnote91 Yet their unequivocal conclusion was that there was hardly ‘anything approaching a highly developed discipline of comparative legal history’ worthy of such qualification in the US at the time of their observation at the dawn of the twenty-first century.Footnote92

4. Diachronic taxonomy: refutation of A Panorama’s comparative classification

The observation of Reimann and Levasseur raises interrogations regarding A Panorama. Was it ‘hardly’ fulfilling the requirements of comparative legal history? If not, how to qualify this atypical contribution to knowledge? Maitland’s worn axiom affirming ‘history involves comparison’ may be misunderstood as implying Zane’s first meaning of vertical comparison in time. In fact, the full quotation continues ‘and the English lawyer who knew nothing and cared nothing for any system but his own hardly came in sight of the idea of legal history’.Footnote93 Maitland giving his inaugural lecture at the University of Cambridge in 1888 seemed to have had a very clear conception of the meaning of horizontal comparative law. If Maitland considered that a premise for history was comparison, history of law does not necessarily involve ‘comparative law’ or comparative jurisprudence as it was then also called – especially not in the US.Footnote94 However, when it does, it gives history its fullest meaning and credibility. Conversely, comparison of laws across frontiers does not have to resort to history either but Wigmore seemed to have shown the signs of a timid soul walking on the footsteps of his ‘giant’ predecessors – somehow trapped between his time’s evolutionist dogma and Maine’s gospel. Riles accounted for the ideological substrate informing Wigmore’s works noting that as it ‘developed, the genre, if not the argument, underwent a deep transformation’.Footnote95 This manifested in a departure from ‘the analytical model – the evolutionary paradigm’ in A Panorama, focusing on the ‘institutions’ of each legal system instead of the ‘doctrine per se’.Footnote96

In relation to A Panorama’s comparative dimension, Pound admitted that ‘a fruitful comparative law, even looking only at the precept element in legal systems of different lands, has to do much more than set side by side sections of codes or of general legislation’.Footnote97 Further, according to Walter Kamba, the comparison process schematically entails a descriptive phase (nomoscopy) necessarily accompanied by identification and explanation of divergencies and similarities.Footnote98 Studies falling short of a systematic use of the latter phase with a plural object are simply not comparative. This syllogism is no stranger to Wigmore’s thought. If the second and third phases are the proper concern of comparative nomogenetics, the real problem was that Wigmore himself seemed to have realistically limited his study to the unsystematic description of the institutions or concepts pertaining to those 16 legal traditions – in separate chapters. As Kamba indicated, ‘systematic comparison should be confined to explicit comparison’.Footnote99 Thus, the juxtaposition of two or more legal traditions in the same book with ‘no thread connecting them’ does not qualify a work as comparative, as these result in an implicit comparison left to the reader’s willingness and ability.Footnote100 John Bell recently highlighted this recurrent problem in comparative law, that is its limitation to nomoscopy.Footnote101 This appears to be an inherent flaw of legal comparison as Wigmore considered almost a century ago to no avail that ‘most of the modern workers, have kept chiefly in the field of what is called above Nomoscopy; ie they have described other systems or institutions, but have not undertaken to trace their evolution (or genetics), comparatively’.Footnote102 Interestingly, this observation was reiterated on the epidemic lack of comparison in publications on ‘comparative’ law some five years later in the form of a complaint on the ‘scantiness of any books and articles that genuinely deal with comparative law … by way of comparing and contrasting the ideas in different systems, and of elucidating their correspondence or divergence – in short, of the evolution of legal ideas’.Footnote103

Notwithstanding this clear awareness and the vast knowledge yielded by A Panorama, each legal tradition is covered separately in different chapters. The structure of the book complicates meticulous cross-referencing and the avoidance of repetition. In fact, it would have been perfectly acceptable to describe the different legal traditions first, before discussing them comparatively. Instead, Wigmore’s concluding chapter, an epilogue titled The Evolution of Legal Systems was simply conceived as a mere exposition of the value of nomogenetics. Therefore, if a restatement is indeed always useful – especially since his enterprise claimed to introduce a novel approach yet unconsidered by previous scholarship – it would have served a more appropriate guiding function in the introduction and should not have been the object of a conclusion. Transcribing most of the content of the first point developed two years earlier in his 1926 article (see Section II, Subsection 2), this conclusion is rather disappointing from a comparative standpoint despite the recurrent use of the term throughout the pages of A Panorama. Finally, as pointed out by Holdsworth, ‘Dean Wigmore draws a moral from his comparative study of legal systems’ at best.Footnote104 These observations are consistent with Reimann and Levasseur’s critique on the absence of systematic comparison for scholarship pretentiously pertaining to ‘comparative legal history’. In the authors’ words, ‘where legal history turns to foreign traditions, it mostly considers them in their own right, ie, without relating them to each other’ failing ‘to compare historical developments, not to mention gain insights from the observations made’.Footnote105

Referring to Wigmore’s own definition of comparative nomogenetics that has been identified as comparative legal history, the fact that Wigmore considered his works as systematically ‘comparative’ and others credited him with such input is significant for the extent of the unsophistication of comparative legal studies in the US during the first half of the twentieth century. Wigmore was thus more of a nomogenetician influenced by the legal evolutionist paradigm, being a legal historian considering the evolution of legal ideas in time despite also considering law in space because of an absence of systematism in this work. A serious combination of verticality and horizontality requires more than an elliptical focus on the former axis and occasional cross-references to a selected few ‘systems’ on the latter axis. Furthermore, the standard requirement for a consistent study of comparative legal history appears to be set too high by the combination of a far-stretching horizontal systematism (16 traditions) and a vertiginous scale spanning (c 6000 years) across the entire selected timeframe from the earliest traces of the oldest legal tradition to the first decades of the twentieth century. Such scope is so unrealistically ambitious that – unless for ‘entertainment’ purposes – it can hardly be rigorously achieved by a single individual during a lifetime.Footnote106

If Kocourek saw in Wigmore both the mythological figure of ‘Hercules’Footnote107 and DC Comics’ superhero ‘Superman’ living ‘a mortal life without taking time either for sleep or food’Footnote108 and Charles P Megan revealed ‘[o]ne of the minor secrets of Wigmore’s success was his extraordinary power of reading very rapidly … – an immense advantage for one working in the vast field of legal scholarship’,Footnote109 and ‘childless’ though married for more than 50 years,Footnote110 it is rather tempting to agree with both the rational side of Kocourek and Basil Markesinis, by reducing the exaggeration of panegyrics resulting from the indebtedness of friendship as well as obituary vocabulary to humanly proportions.Footnote111 Regardless of the imprecise classification of A Panorama at a time when the subject was at its infancy stage, blossoming under the impulse of few temerarious legal minds, Pollock seemed to have predicted Wigmore’s advent.Footnote112 A pertinent reminder that, although imperfect, the pioneering contribution of John Henry Wigmore, and others, is an inestimable gift to posterity.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to Anthony Chamboredon who acted in the author’s regard similarly to Charles Eliot facilitating the path to comparative legal studies. Section I was presented during a joint Workshop organised by the Legal History section of the Society of Legal Scholars and LSE’s Legal Biography Project in early September 2021. The author thanks the anonymous reviewers for additional reading suggestions in relation to Section I, Piotr Alexandrowicz for his brilliant editing and Stephen Hewer for his insights, professionalism and humanity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Rudyard Kipling, Rudyard Kipling’s Verse Definitive Edition (Doubleday, 1940) 233.

2 William R Roalfe, ‘John Henry Wigmore, 1863–1943’ (1964) 58 Northwestern University Law Review 445, 450.

3 John H Wigmore, ‘Comparative Law: Jottings on Comparative Legal Ideas and Institutions’ (1931) 6 Tulane Law Review 48; Kenneth W Abbott, ‘Wigmore: The Japanese Connection’ (1981) 75 Northwestern University Law Review 10, 11; John H Wigmore, A Kaleidoscope of Justice Containing Authentic Accounts of Trial Scenes from All Times and Climes (Washington Law Book Co, 1941) iii for an in memoriam note dedicated to Charles W Eliot in this last book published by Wigmore only two years before his tragic passing. See ‘Dean Wigmore “Retires”’ (1943) 20(3) The Law Student 3; ‘Editorials: John Henry Wigmore’ (1943) 34 Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 3; Glenn R Winters, ‘Remembering John Wigmore’ (1976) 59 Judicature 356.

4 Albert Kocourek and John H Wigmore, Evolution of Law: Sources of Ancient and Primitive Law (Little, Brown & Co, 1915) vol 1, xi.

5 John H Wigmore, A Panorama of the World’s Legal Systems (Saint Paul West Publishing Co, 1928) vol 1, xv.

6 Wigmore, ‘Comparative Law’ (n 3).

7 Kocourek and Wigmore (n 4) vol 1, xi–xii (emphasis added).

8 Walter J Kamba, ‘Comparative Law: A Theoretical Framework’ (1974) 23 International & Comparative Law Quarterly 485, 489–90, 501–04.

9 Geoffrey Samuel, An Introduction to Comparative Law Theory and Method (Hart Publishing, 2014) 120.

10 Abbott (n 3) 10.

11 Roalfe (n 2) 445, 451; Abbott (n 3) 11.

12 Abbott (n 3) 11.

13 William R Roalfe, ‘John Henry Wigmore: Scholar and Reformer’ (1962) 53 Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science 277, 293. Wigmore ‘used to read his foreign language on the train, whispering the words to himself, in spite of looks from the other passengers (and I [Sarah B Morgan] really do not believe that he saw the looks as he was thoroughly engaged in what he was doing, but he would not have cared if he had seen them)’. ‘When he decided to go to Morocco … he started studying alone from a French-Arabic grammar (there being no English-Arabic grammars), and he was in his seventies at the time! Then … he got in touch with a priest in a Syrian church in Michigan City, Indiana, and paid him to come to Chicago once a week and give him an hour of spoken Arabic’.

14 James A Rahl, ‘Wigmore as Professor and Dean’ (1981) 75 Northwestern University Law Review 4, 5.

15 Annelise Riles, ‘Encountering Amateurism: John Henry Wigmore and the Uses of American Formalism’ in Annelise Riles (ed), Rethinking the Masters of Comparative Law (Hart Publishing, 2001) 94.

16 Ibid, 100.

17 René Guénon, East and West (Martin Lings tr, Sophia Perennis, 2001) 73. See René Guénon, Orient et Occident (Véga, 2006) 105 for the original statement in French.

18 Abbott (n 3) 11.

19 Riles (n 15) 100.

20 Abbott (n 3) 11–12.

21 Albert Kocourek, ‘John Henry Wigmore’ (1912) 24 Green Bag 3; Albert Kocourek, ‘John Henry Wigmore’ (1943) 27 Journal of the American Judicature Society 122, 124; Sarah B Morgan, ‘Wigmore: The Man’ (1964) 58 Northwestern University Law Review 461, 462.

22 John H Wigmore, ‘The Legal System of Old Japan’ (1892) 4 Green Bag 403 (emphasis added).

23 Abbott (n 3) 15–16.

24 Riles (n 15) 95.

25 Roalfe (n 13) 288–89; Abbott (n 3) 13.

26 Roscoe Pound, ‘The Place of Comparative Law in the American Law School Curriculum’ (1934) 8 Tulane Law Review 161, 168; Konrad Zweigert and Hein Kötz, An Introduction to Comparative Law (Tony Weir tr, 3rd edn, OUP, 1998) 6. See also Kamba (n 8) 505–06; Xavier Blanc-Jouvan, ‘Centennial World Congress on Comparative Law: Closing Remarks’ (2001) 75 Tulane Law Review 1235, 1236.

27 Abbott (n 3) 12.

28 Guénon, East and West (n 17) 97 (emphasis added). See Guénon, Orient et Occident (n 17) 137 for the original French version.

29 Guénon, East and West (n 17) 98 (emphasis added). Guénon, Orient et Occident (n 17) 138–39.

30 Abbott (n 3) 11.

31 Wigmore, ‘Comparative Law’ (n 3) 48. See also Christopher Benfey, The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics and the Opening of Old Japan (Random House, 2004) for a popular account on visitors of Japan concerned with its tradition and neglect during the Meiji era.

32 Riles (n 15) 104.

33 Abbott (n 3) 12.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 John H Wigmore, Materials for Study of Private Law in Old Japan (The Asiatic Society of Japan, 1892).

37 Roalfe (n 13) 288–89.

38 Wigmore, Materials (n 36) [translated by Wigmore] citing Franz Bernhöft, (1878) 1 Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Rechtswissenschaft (emphasis added).

39 Teemu Ruskola, ‘Legal Orientalism’ (2002) 101 Michigan Law Review 179; Teemu Ruskola, ‘The World According to Orientalism’ (2012) 7 Journal of Comparative Law 1; Teemu Ruskola, Legal Orientalism: China, the United States and Modern Law (Havard UP, 2013); see also Edward Said, Orientalism (Vintage Books, 1979).

40 Samuel (n 9) 6, 9 (emphasis added); see also Geoffrey Samuel, ‘Taking Methods Seriously (Part Two)’ (2007) 2 Journal of Comparative Law 230–31.

41 Ruskola, ‘Legal Orientalism’ (n 39) 209.

42 Ruskola, ‘The World’ (n 39) 2–4; Stefan Kroll, ‘Teemu Ruskola, Legal Orientalism: China, the United States and Modern Law’ (2015) 3(1) CLH 207, 208, 211. It is not contended that orientalism may produce effects affecting legal developments in the orientalist’s jurisdiction.

43 Riles (n 15) 100.

44 Guénon, East and West (n 17) 95 (emphasis added). See Guénon, Orient et Occident (n 17) 135 for the original French version.

45 Kocourek, ‘John Henry Wigmore’ (1912) (n 21) 5; Riles (n 15) 94.

46 Abbott (n 3) 11 (emphasis added).

47 Ibid.

48 See Ruskola’s Legal Orientalism book review by Carol G S Tan, ‘How a “Lawless” China Made Modern America: an Epic Told in Orientalism’ (2015) 128 Harvard Law Review 1677.

49 Wigmore, ‘Comparative Law’ (n 3) 49 (emphasis added). See Carl Steenstrup, A History of Law in Japan until 1868 (Brill, 1991) for a more recent substantive account of Japanese legal history until the Meiji Restoration. See also Wilhelm Röhl (ed), History of Law in Japan since 1868 (Brill, 2005); Marius B Jansen (ed), The Emergence of Meiji Japan (CUP, 1995) and Marius B Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan (Harvard UP, 2000) for later Japanese legal developments.

50 John H Merryman, ‘On the Convergence (and Divergence) of the Civil Law and the Common Law’ (1981) 17 Stanford Journal of International Law 357, 359–60.

51 Igor Stramignoni, ‘Le regard de la comparaison: Nietzsche, Heidegger, Derrida’ in Pierre Legrand (ed), Comparer les Droits, Résolument (PUF, 2009) 161–62 (translated from French by the author, original emphasis). See also Pierre Legrand, ‘The Same and the Different’ in Pierre Legrand and Roderick Munday (eds), Comparative Legal Studies: Traditions and Transitions (CUP, 2003) 240 on the persistent emphasis on similarities instead of differences in comparative legal studies and more recently, Pierre Legrand, Negative Comparative Law: A Strong Programme for Weak Thought (CUP, 2022) 229.

52 Frederic Maitland, Why the History of English Law is Not Written: An Inaugural Lecture (CUP, 1888) 11.

53 Mathias Reimann and Alain Levasseur, ‘Comparative Law and Legal History in the United States’ (1998) 46 The American Journal of Comparative Law 1, 4 on ‘the concept of legal tradition’.

54 Wigmore, A Panorama (n 5). See H Patrick Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World (5th edn, OUP, 2014) for a recent work where the traditions are identified as ‘Muslim’, ‘civil law’ and ‘common law’ instead of the use by Wigmore of incorrect designations such as ‘Mohammedan’, ‘Romanesque’ and ‘Anglican’.

55 John H Wigmore, ‘Some Legal Systems That Have Disappeared’ (1939) 2 Louisiana Law Review 1.

56 Frederick C Hicks, ‘Current Legal Literature’ (1929) 15 American Bar Association Journal 575, 576; William S Holdsworth, ‘Book Reviews’ (1929) 77 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 1038; Arthur L Goodhart, ‘Book Reviews’ (1929) 38 The Yale Law Journal 554; Henry B Witham, ‘Book Reviews’ (1936) 15 Tennessee Law Review 834.

57 Riles (n 15).

58 Jean-Baptiste Busaall, Fatiha Cherfouh and Gwenaël Guyon, ‘Du comparatisme au droit comparé, regards historiques, Introduction’ (2017) 13 Clio@Themis 1, 3 [‘comparatisme’ in French].

59 Ibid.

60 Reimann and Levasseur (n 53) 13.

61 John H Wigmore, ‘A New Way of Teaching Comparative Law’ [1926] Journal of the Society of Public Teachers of Law 6.

62 Ibid, 9.

63 Ibid, 6.

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid.

66 Frederick Pollock, ‘History of Comparative Jurisprudence’ (1903) 5 Journal of the Society of Comparative Legislation 74, 79 on the ‘historical method and the doctrine of evolution’.

67 Wigmore, ‘Comparative Law’ (n 3) 50.

68 Pollock (n 66) 86.

69 Ibid.

70 Riles (n 15) 106–07.

71 Kocourek and Wigmore (n 4) vol 1, xii.

72 Wigmore (n 61) 7.

73 Ibid, 7, 9.

74 Kocourek, ‘John Henry Wigmore’ (1943) (n 21) 123–24.

75 Pierre Legrand, ‘John Henry Merryman and Comparative Legal Studies: A Dialogue’ (1999) 47 American Journal of Comparative Law 3, 5–6.

76 Albert Kocourek, ‘John Henry Wigmore 1863–1943’ (1943) 29 American Bar Association Journal 316.

77 Roscoe Pound, ‘Comparative Law in Space and Time’ (1955) 4 American Journal of Comparative Law 70, 71.

78 Kocourek, ‘John Henry Wigmore’ (1912) (n 21) 5.

79 See John M Maguire, ‘Wigmore: Two Centuries’ (1964) 58 Northwestern University Law Review 456 for a correspondence with the Supreme Court Justice.

80 William S Holdsworth, ‘Wigmore as a Legal Historian’ (1935) 29 Illinois Law Review 448.

81 Reimann and Levasseur (n 53) 7.

82 Holdsworth (n 80) 453.

83 John M Zane, ‘A Pioneer in Comparative Law’ (1935) 29 Illinois Law Review 456 (emphasis added).

84 Holdsworth (n 80).

85 Zweigert and Kötz (n 26) 2.

86 Reimann and Levasseur (n 53) 1 (emphasis added).

87 Wigmore, A Panorama (n 5) vol 3, 1130.

88 Ibid, vol 1, xiv–xv.

89 Kocourek and Wigmore (n 4) vol 1, vii (emphasis added).

90 Pound (n 77) 72 (emphasis added).

91 Reimann and Levasseur (n 53) 13.

92 Ibid.

93 Maitland (n 52) 11.

94 Reimann and Levasseur (n 53) 13.

95 Riles (n 15) 111.

96 Ibid.

97 Pound (n 77) 75.

98 Kamba (n 8) 511–12 (original emphasis).

99 Ibid, 506.

100 Ibid, 512.

101 John Bell, ‘Legal Research and the Distinctiveness of Comparative Law’ in Mark Van Hoecke (ed), Methodologies of Legal Research: Which Kind of Method for What Kind of Discipline? (Hart Publishing, 2011) 155–76, 158.

102 Wigmore (n 61) 6–7.

103 Wigmore, ‘Comparative Law’ (n 3) 49–50 (original emphasis).

104 Holdsworth (n 56) 1039 (emphasis added).

105 Reimann and Levasseur (n 53) 13–14.

106 Wigmore, A Kaleidoscope (n 3) v: ‘READER! this work is not offered to you as a piece of scientific research, but mainly as a book of informational entertainment’. Although a similar disclaimer is readily found in A Panorama (n 5) vol 1, xiii, these first two lines in his very last book’s preface – nearing his eighties – are more concise. A fitting summary of Wigmore’s remarkable humility and a testament to his unmatched resourcefulness in the use of ‘tricks’ up his sleeves showcased by himself and used to captivate his contemporaries introducing a novice audience to the mysteries of global legal history.

107 Kocourek, ‘John Henry Wigmore’ (1943) (n 21) 123.

108 Kocourek, ‘John Henry Wigmore’ (1912) (n 21) 4.

109 Charles P Megan, ‘On Behalf of the Bar’ (1943) 34 Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 78.

110 Roalfe (n 2) 451; Rahl (n 5) 5.

111 Kocourek, ‘John Henry Wigmore’ (1912) (n 21) 7; Basil Markesinis, ‘Scholarship, Reputation of Scholarship and Legacy: Provocative Reflections from a Comparatist’s Point of View’ (2003) 38 The Irish Jurist 1, 17.

112 Pollock (n 66) 88–89. See Virgil, Eclogues (Wendell Clause ed, OUP, 1994) 12 (Latin) and 125 (English): ‘A second Argo will transport the chosen heroes; there will be new wars’.