ABSTRACT

A scoping review was conducted to map the availability and nature of early detection and intervention services for children with hearing loss in Western and South Asian developing countries. The scoping review followed the five-stage framework outlined by Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. [(2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616]. Terms relating to research question were searched in PubMed, CINAHL and Scopus. An additional grey literature search was conducted in relevant area. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied on 1,237 articles. Included articles were categorized based on delivered services. Analysis of the literature identified that many countries in Western and South Asia have some available services. Specifically, (1) newborn hearing screening programmes are not available in all hospitals; (2) there are some centres providing amplification devices and cochlear implants, but these are limited in number; and (3) families have difficulty accessing therapy services. 31 texts were included in the scoping review. These findings highlight that whilst some early detection and intervention services for children with hearing loss are available in developing countries in Western and South Asia, they are not yet fully established, and thus there are limitations to addressing all factors in early detection and intervention and optimizing outcomes for children with hearing loss.

Introduction

Hearing loss is an auditory disorder affecting 1 in every 750 children worldwide (WHO, Citation2018). Children with hearing loss are still at risk of experiencing difficulties across multiple domains, including speech and language acquisition, literacy and academic performance, and social development (Figueras, Edwards, & Langdon, Citation2008; Newton, Citation2009; Winskel, Citation2006; Yoshinaga-Itano, Coulter, & Thomson, Citation2000; Yoshinaga-Itano, Sedey, Mason, Wiggin, & Chung, Citation2020) The risk of ongoing difficulties is influenced by a range of factors including (1) age of onset; (2) age of identification; (3) type of hearing loss; (4) use of hearing aids and other assistive listening devices (e.g., cochlear implants); (5) family involvement; and (6) availability of early intervention services (Ching et al., Citation2010; Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, Citation2019; Thompson et al., Citation2001; Yoshinaga-Itano, Sedey, Coulter, & Mehl, Citation1998; Yoshinaga-Itano et al., Citation2020)

Ongoing difficulties can be mitigated through early intervention which aims to ensure that all newborns are screened for hearing loss shortly after birth, with early detection and immediate access to technological and therapeutic interventions, such as hearing aids, cochlear implants, and therapy services within the first six months of life (Community Care Population Health Principal Committee, Citation2013; Joint Committee on Infant Hearing [JCIH], Citation2019). Previous research has demonstrated that early intervention can facilitate the development of a child's communication skills, in line with their typically developing peers (Ching et al., Citation2010; Yoshinaga-Itano et al., Citation1998; Yoshinaga-Itano et al., Citation2020), with early intervention enhancing a child’s chances of educational success and other social skills (Thompson et al., Citation2001). Therefore, early intervention is recommended, to assist children with hearing loss to overcome challenges to their communication, education, and social development (Yoshinaga-Itano, Citation2003).

The JCIH (Citation2019) has developed principles and guidelines to support early intervention practices for children with hearing loss and their families. The primary goals of the JCIH are to: promote early identification of infant hearing loss through screening by one month of age, preferably screening prior to hospital discharge; the fitting of amplification devices (i.e., hearing aids) by three months of age; and enrolment in early intervention services by six months of age (JCIH, Citation2019; Yoshinaga-Itano, Citation2003). These JCIH early hearing detection and intervention goals are known as ‘1–3–6’, with early intervention services matching the child's goals and needs (JCIH, Citation2019).

Moreover, the JCIH encourages a family-centred approach through the provision of information and guidelines to support a child's early intervention goals. The JCIH outlines clear procedures to guide health professionals in implementing newborn hearing screening programmes and how to work together to meet the 1–3–6 guidelines (JCIH, Citation2019). Most developed countries (e.g., the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia) apply the JCIH principles and guidelines through universal newborn hearing screening programmes (UNHS) and access to early intervention services (Community Care Population Health Principal Committee, Citation2013; JCIH, Citation2019; Wolff et al., Citation2010). For example, in Australia, the Community Care Population Health Principal Committee reported on framework and guidelines that are supported by evidence base stander practice that includes recruitment, screening, diagnosis, early intervention, treatment and management. Recruiting and screening newborns within 24–72 h of birth with the aim of completion 4 weeks of age using transient evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAE) and automated auditory brainstem response. If newborns fail the screening, then they are referred for further diagnostic assessment. Conformation of hearing loss should be completed by 3 months of age and babies are referred to medical evaluation and to early intervention services as soon as possible no later than 6 months of age (Citation2013). Also, cross-agency collaboration has been used to ensure equality in accessing the services for participants from rural geographical locations, different cultural backgrounds and socio-economic statuses (Citation2013). However, the nature and availability of newborn hearing screening and early intervention services in developing Western and South Asian countries is not known.

Developing countries are defined as emerging nations in their total national income and/or quality of life, such as life expectancy, health, and educational factors (United Nations, Citation2021). Developing countries in Western and South Asia include Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Iran, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, State of Palestine, Syrian Arab Republic, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen (MDG, Citation2014; United Nations, Citation2021). In these developing countries, early intervention services for children with hearing loss are still in the initial stages of development. Previous research exploring services for children with hearing loss in some developing Western and South Asian countries have reported barriers such as delayed detection and diagnosis of hearing loss in both Saudi Arabia and Kuwait (Al-Shawi, Alrawaf, Al-Gazlan, Al-Qahtani, & Almuhawas, Citation2020; Alduhaim, Purcell, Cumming, & Doble, Citation2020) and difficulty accessing services due of the distribution of services across the country in India (Bishnoi, Baghel, Agarwal, & Sharma, Citation2019; Sachdeva & Sao, Citation2017; Galhotra & Sahu, Citation2019).

Whilst these studies have begun to explore early intervention services, there is a lack of understanding about the implementation of services and the nature of the services that are offered across Western and South Asian developing countries. In order to begin to address the challenges of delivering early intervention services to children with hearing loss in developing Western and South Asian countries, there is a need to understand the extent to which early intervention services are available in these countries. Therefore, this study aimed to describe the availability and nature of early intervention services for children with hearing loss in developing countries in Western and South Asia.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted to understand the availability and nature of early intervention services for children with hearing loss in developing countries of Western and South Asia. Scoping reviews summarize a wide range of evidence to provide greater understanding and conceptual clarity in the search area (Davis, Drey, & Gould, Citation2009; Levac, Colquhoun, & O'Brien, Citation2010). Scoping reviews, therefore, help create a comprehensive literature map, while identifying key concepts and theories, and identifying research gaps (Levac et al., Citation2010). This type of review also allows for the inclusion of a broad range of peer-reviewed and grey literature (Levac et al., Citation2010).

The scoping review in the current study followed the five-stage framework proposed by Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005) and Levac et al. (Citation2010) including (1) identification of the research question; (2) identification of relevant studies; (3) selection of studies; (4) charting the data; and (5) result collection, summary, and report formulation.

Identification of the research question

The development of a specific research question in the first stage of this review provided a clear, focused, and constructive search strategy that addressed the targeted population and area of interest (Levac et al., Citation2010). The objective of the current study was to understand the early intervention services for children with hearing loss in developing countries in Western and South Asia. The overarching research question was: What is the availability and nature of early detection and intervention services for children with hearing loss and their families in developing Western and South Asian countries?

Identification of relevant research

In order to identify relevant research, the research team consulted a liaison librarian experienced in health and rehabilitation sciences, to develop a search strategy for the research question and to identify appropriate databases. PubMed, CINHAL and Scopus, were searched in November 2020 and updated in March 2022. The search terms for the main group (e.g., ‘intervention’, ‘developing countries in Western and South Asia, ‘children’ and ‘hearing loss’) were combined using the term ‘AND’. Other keywords within each main group were combined with ‘OR’. Each electronic database utilizes a unique keyword input enquiry. For example, the term ‘MeSH’ is used in PubMed search strategies when looking at titles and abstracts (i.e., ‘Hearing Disorders’ [MeSH]). Alternatively, Scopus requires direct input of the keyword ‘Hearing Disorders’. Therefore, each term was carefully adapted, in consultation with the subject librarian, while using different databases (see Supplementary A for an outline of the search terms used).

The research team also conducted a search of the grey literature to find further information that would help answer the research question. This grey literature search was conducted by searching official government websites and official organization websites of developing countries in Western and South Asia. A grey literature plan was developed using three strategies: (1) Google search engine; (2) targeted websites, official government websites and official organizations; and (3) key terms search; (i.e., hearing screening, early intervention services, children with hearing loss, developing countries in Western and South Asia). See Supplementary A for an outline of the search terms used. These strategies were used to minimize omitting or overlooking relevant resources.

Study selection

The following inclusion criteria were applied for the scoping review: (1) published in English; (2) reported on children aged 0–8 years with hearing loss; (3) reported on early detection and intervention services, including guidelines, practices, habilitation or therapy programmes, screening, diagnosis assessment, support services, use of technology; (4) reported on services in 1 of the 22 developing countries in Western and South Asia, including Afghanistan, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Maldives, Nepal, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, State of Palestine, Syrian Arab Republic, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen (MDG, Citation2014; United Nations, Citation2021); (5) published after 2010; and (6) reported on data collected from 2010 onwards. Applying these criteria ensured that the included studies addressed the research question’s specific areas and populations.

The first author (JB) conducted the initial title and abstract screening using Covidence (Covidence, Citation2022) online software as the main screening engine. Twenty percent of titles and abstracts were screened by a second reviewer (MN) to confirm consistency on study inclusion eligibility. Following that, JB conducted screening on all studies, with other research team members RN, MN, and NS sharing the screening of all the studies. Conflicted studies were reviewed by NS and RN to resolve remaining conflicts.

Charting the data

Included studies were summarized in a Microsoft® Excel chart for analysis. This chart was used to record general and specific information about the studies, including author(s), year of publication, country of origin, study aim, study population, the method used to evaluate or explore early detection, intervention services, and early intervention types and protocols.

Results

Database results

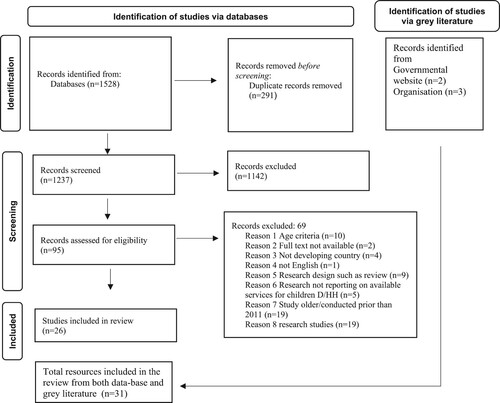

The electronic database search identified 1,528 citations, of which 1,237 were screened at the title and abstract stage following the removal of duplicates. After the initial screening phase, the full text of 95 remaining studies were assessed for eligibility, with data extracted from the 26 studies that met the inclusion criteria. A summary of the search results and stages is outlined in .

Grey literature search

The grey literature search identified two government websites and websites from three official organizations (n = 5) which contained information about early intervention services for children with hearing loss in developing countries in Western and South Asia. A summary of the search results and stages is outlined in .

Combined search

A total of 31 sources (Supplementary B) reporting on early detection and intervention services for children with hearing loss in developing countries in Western and South Asia were identified across the peer-reviewed and grey literature. In total, 17 of the 22 developing countries in Western and South Asia had published studies or grey literature reporting on early detection and intervention services for children with hearing loss. provides a summary of the available early detection and intervention services in each developing country. No literature was found for the following six countries: Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, State of Palestine, Syrian Arab Republic, and Yemen.

Table 1. Database literature.

The 31 identified sources were categorized into one or more of two distinct categories of early intervention services for children with hearing loss: (1) identification and diagnosis of hearing loss (n = 31) and (2) intervention for hearing loss; including provision of amplification devices (n = 17) and therapy (n = 10). These stages reflect the ‘1–3–6’ JCIH guidelines (2019) for early intervention services for children with hearing loss.

(1)#Identification and diagnosis of hearing loss

The scoping review revealed that within developing countries in Western and South Asia, the implementation of early detection and intervention services dedicated to the identification of hearing loss ranged from: (1) fully implemented National Hearing Screening (NHS) programme; (2) partially implemented NHS programme, or (3) not implemented.

Fully implemented national hearing screening programme

Only 2 of the 22 countries, namely Iran and Turkey, had reports of a NHS programme for early hearing detection. Four published studies in Iran and Turkey (Acar et al., Citation2015; Ardic, Citation2017; Saki et al., Citation2017; Shojaee et al., Citation2013) and one Turkish grey literature source (Uhlén, Citation2020) reported on national programmes providing a unified guideline for early detection of hearing loss. Newborn hearing screening was established in Turkey in 2004 (Acar et al., Citation2015; Ardic, Citation2017) and Iran in 2002 (Saki et al., Citation2017; Shojaee et al., Citation2013), with screening conducted in both Turkey and Iran before newborns are discharged from hospital. Both countries follow a similar protocol, testing for newborn hearing by: (1) screening newborns using auditory brainstem response (ABR) and otoacoustic emission (OAE) for pass/fail and in the case of failure and (2) conducting further diagnostic testing (Acar et al., Citation2015; Ardic, Citation2017; Saki et al., Citation2017) ().

Table 2. Grey literature.

Partially implemented national hearing screening

Eighteen sources reported on the partial availability of hearing screening programmes across eight developing countries, including Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, India, Oman, Bahrain, Jordan, United Arab Emirates, and Qatar (Al-Sayed & AlSanosi, Citation2017; Al-Shawi et al., Citation2020; Alanazi, Citation2020; Alyaa Alduhaim et al., Citation2020; R. Alkahtani et al., Citation2019; H. Alyami et al., Citation2016; Ansari, Citation2014; Ayas & Yaseen, Citation2021; George et al., Citation2016; Kolethekkat et al., Citation2020; Merugumala et al., Citation2017; Nuseir et al., 2020; PHCC, Citation2021; Sachdeva & Sao, Citation2017; Sharma et al., Citation2018; Sukumaran, Citation2011; UNBHS Program, Citation2021; WHO, Citation2009). Reasons for the partial availability of a newborn NHS programme were variable across developing countries and included the availability of NHS in hospitals, the availability of newborn hearing screening protocols, the availability of staff, and the awareness of hearing loss.

NHS programme was not always available in every hospital at all times. For example, in Kuwait, NHS was reported to be compulsory in public hospitals but optional for parents in private hospitals (Alduhaim et al., Citation2020). Similarly, in Bahrain the availability of NHS was only reported to be consistently offered in university hospitals (George et al., Citation2016). Meanwhile, other studies in Saudi Arabia noted that the availability of NHS was minimal and not consistently available in rural hospitals, despite the majority of the population living in rural areas (Al-Sayed & AlSanosi, Citation2017; Al-Shawi et al., Citation2020; R. Alkahtani et al., Citation2019; H. Alyami et al., Citation2016). In India, due to limited NHS access, alternative community-based prevention control programmes assess hearing through questionnaires distributed by healthcare workers or behavioural testing. If newborns fail the NHS, parents are advised to follow up at district hospitals (Galhotra & Sahu, Citation2019; WHO, Citation2009). In Oman, NHS is only available during weekdays and therefore screening is typically only conducted on approximately 72% of all newborns, with babies born on the weekend not participating in a NHS programme (Kolethekkat et al., Citation2020). A Qatar governmental website advised that hearing screening is available for public patients referred by a general practitioner or an ear nose and throat specialist (PHCC, Citation2021).

In addition to the variability of NHS across countries, this review found that healthcare settings lack the structural protocols needed to conduct hearing screening for children with hearing loss. Multiple studies have reported that children’s hearing testing protocols differ from one healthcare facility to another (Ansari, Citation2014; Galhotra & Sahu, Citation2019; Sachdeva & Sao, Citation2017; Sharma et al., Citation2018; Sukumaran, Citation2011; WHO, Citation2009). For example, the NHS is not unified across healthcare settings in Saudi Arabia, leaving many hospitals utilizing different protocols for conducting hearing screening (Alanazi, Citation2020). This lack of service structure has resulted in many children’s hearing losses being first detected by their parents, rather than a hearing screening facility (Merugumala et al., Citation2017). Three studies reported the use of the same screening tools/protocols in Oman, Jordan and Bahrain. In Oman, the protocol for testing utilizes OAE for pass/fail criteria; if the newborn fails the screening twice, they are referred for further testing by using ABR (Kolethekkat et al., Citation2020). Similarly, in Bahrain, the NHS uses OAE to screen infants; if the infants fail twice, they are scheduled to have diagnostic testing by using ABR (George et al., Citation2016). In Jordan, evaluations are currently being conducted on their protocols for newborn hearing screening to minimize false negative rate (Zaitoun & Nuseir, Citation2020). Just one UAE study identified the use of ABR hearing screening for newborns (Ayas & Yaseen, Citation2021). Such variations suggest that there is no consistency to the approach used when conducting newborn hearing screening in these countries.

Finally, the review also found that the availability of staff and the awareness of hearing loss impacted on the implementation of NHS. In a study conducted in United Arab Emirates, there were reports on staff shortages resulting in newborns being left unscreened for hearing loss (Ayas & Yaseen, Citation2021) . In addition, Ayas and Yaseen (Citation2021) stated in their study that in UAE there are a lack of trained healthcare professionals to conduct and implement NHS (Ayas & Yaseen, Citation2021). In Saudi Arabia, citizens had limited access to information about hearing loss (Alanazi, Citation2020) and George et al. (Citation2016) also reported that in Bahrain there is a need to increase the general public’s awareness of the NHS and its benefits.

National hearing screening not available

The World Health Organization reported that unified national programmes for early detection of hearing loss were not available in six countries: Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives, and Sri Lanka (2009). However, the scoping review identified that screening and diagnosis is partially available through certain organizations in some of these countries, such as teaching hospitals in Sri Lanka and centres in Nepal and Sri Lanka (WHO, Citation2009). A more recent report from WHO stated that the government of Pakistan has initiated plans to develop a national hearing screening programme (WHO, Citation2021).

(2)#Intervention for children with hearing loss

Provision of amplification devices

In total, 13 (10 peer-reviewed and 3 grey literature) sources from Turkey, Qatar, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, India, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan reported on the provision of amplification devices and cochlear implants for children with hearing loss in the developing countries of Western and South Asia. The studies described: (1) access to amplification devices and/or cochlear implants; and (2) source of information for amplification devices and cochlear implants.

(1)#access to amplification devices and/or cochlear implants

Access to healthcare systems and the provision of amplification devices or cochlear implants differed from one country to another. The provision of amplification devices is available and free for children with hearing loss in Jordan, Turkey, and Qatar. In 2014, Jordan aimed to increase free access to cochlear implants for children with hearing loss. Alkhamra (Citation2015) reported that guidelines in Jordan stipulate that children with hearing loss should undergo a 3–6 month trial period to assess their progress and ensure their eligibility and suitability, before having a cochlear implant, however, only 5% received cochlear implant before under 1 year of age. Similarly, Acer and colleagues (2020) reported that in Turkey, children who have not benefited from a hearing aid would then have a cochlear implant. The typical age for cochlear implantation in Turkey is 12 months (Acar et al., Citation2020). The grey literature reported that in Turkey the number of children fitted with amplification devices per year is unavailable (Uhlén, Citation2020). Whilst there was no peer-reviewed literature that reported on amplification devices in Qatar, the governmental website stated that audiological services, such as amplification devices, were available for recommended candidates (PHCC, Citation2021). A number of studies across multiple countries reported a shortage of amplification devices in Oman, India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepa and Sri Lanka. In Oman, the lack of hearing amplification and cochlear implants in some centres has resulted in further referrals to other centres or overseas, resulting in delays in access to hearing devices (Kolethekkat et al., Citation2020). Similarly, in India, 35 clinics reported access problems due to a lack of funding for cochlear implant devices, device maintenance, and accessories (Jeyaraman, Citation2013; Paul et al., Citation2017; Sukumaran, Citation2011). The WHO reported that countries such as Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka do not have a national policy for early intervention for children with hearing loss (2009). However, in Bhutan, Bangladesh and Pakistan have free amplification devices distribution programme such as hearing aids (WHO, Citation2009, Citation2021). Furthermore, other countries such as in Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka were reported to that some centre provide cochlear implants, but there is no programme to distribute hearing aids (WHO, Citation2009, Citation2021).

Local access to amplification devices was noted as a barrier in India and Saudi Arabia specifically. In India, families said that audiological services are not always near their homes (Ansari, Citation2014) whereas in Saudi Arabia, children who live relatively close to major cities have access to services and are granted hearing devices at a younger age than children in more remote areas (Al-Sayed & AlSanosi, Citation2017). It was also reported that Saudi children in urban areas usually receive cochlear implants after the age of 6 months (Al-Sayed & AlSanosi, Citation2017; H. Alyami et al., Citation2016).

(2)#Source of information for amplification devices and cochlear implants

Two studies published in Jordan (Alkhamra, Citation2015) and Saudi Arabia (Aloqaili et al., Citation2019) reported on the information parents received regarding amplification devices for their children with hearing loss. Both countries reported that healthcare professionals, namely Ear, Nose and Throat specialists and audiologists, are the families’ first source for information regarding amplification devices and cochlear implants (Alkhamra, Citation2015; Aloqaili et al., Citation2019). Whilst families do engage with healthcare professionals, the study conducted by Aloqaili et al. (Citation2019) reported that parents are more involved than healthcare professionals when choosing different types and ranges of cochlear implants. Also, in Saudi Arabia healthcare professionals had been less involved than parents in choosing different types and ranges of cochlear devices (Aloqaili et al., Citation2019). Parents shared that they felt comfortable gathering information about the devices from the internet (Alkhamra, Citation2015; Aloqaili et al., Citation2019) and that family members of other children with hearing loss were also sources of information (Alkhamra, Citation2015).

Therapy

Eight published studies (Acar et al., Citation2020; A. Alduhaim et al., Citation2020; Alkhamra, Citation2015; H. Alyami et al., Citation2016; Ansari, Citation2014; Jeyaraman, Citation2013; Kulkarni & Gathoo, Citation2017; Merugumala et al., Citation2017), and two sources of grey literature (PHCC, Citation2021; Uhlén, Citation2020) across six developing countries in Western and South Asia reported on the available therapy services for children with hearing loss in Turkey, India, Jorden, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. The types and extent of implementation of therapy services varies across countries to which therapy is implemented and the common barriers.

Whilst therapy services are available in Turkey, it is unknown whether all children with hearing loss are referred into therapy programmes (Uhlen, Citation2020). One study conducted at Turkey’s University Base Education and Research Centre illustrated how parent–child interaction was addressed in their intervention services to support a child’s acquisition and development of language (Acar et al., Citation2020). However, there are still unknown statistics surrounding the number of children with hearing loss, who are referred to therapy programmes (Uhlén, Citation2020). Two studies reported that programmes in Jordan (Alkhamra, Citation2015) and Kuwait (Alduhaiml et al., Citation2020) provided aural rehabilitation for children with hearing loss, pre- and post-cochlear implantation (A. Alduhaim et al., Citation2020; Alkhamra, Citation2015). In Kuwait, speech pathologists use various communication approaches with parents of children with hearing loss, to support the implementation of therapy activities at home. However, parents reported that the resources in speech and audiology sessions were not new and did not grab the children’s attention, indicating that there was room for improvement in the therapy provided (Alduhaim et al., Citation2020). Patients registered in Qatar’s Primary Health Care Corporation receive services for rehabilitation and habitation, such as educating families about hearing loss, and counselling regarding the care and use of the hearing amplification devices (PHCC, Citation2021).

Several studies have reported on barriers which limit access to early intervention therapy programmes for children with hearing loss. For example, in Saudi Arabia, most people live outside major cities, whilst therapy is provided within major cities. Therefore, the geographic location of therapy services restricts access for those who live outside the city (Al-Sayed & AlSanosi, Citation2017; H. Alyami et al., Citation2016). In India, it has been reported that due to family size and the lack of local services near their residential area and that people find it hard to travel to the therapy centre locations (Ansari, Citation2014). Research has reported on the perspectives of parents regarding their experiences of intervention services (H. Alyami et al., Citation2016). In Saudi Arabia, families reported: (1) a delay in hearing aid fitting; and (2) that it took a long time to start the therapy sessions. The main age for children in Saudi Arabia enrolled in speech therapy sessions was 32 months and children attended fewer sessions than expected (H. Alyami et al., Citation2016). Meanwhile, in India, families were not fully aware of services to support their children with hearing loss. As a result, they tried alternative therapies because they did not know about free and/or effective services for children with hearing loss (Merugumala et al., Citation2017). Healthcare professionals also noted barriers and one study reported that professionals face challenges regarding the delivery of therapy, such as lack of a specific programme protocols, lack of standardized assessment tools, a poor understanding of cochlear implant outcomes, and a lack of materials for rehabilitation programmes (Jeyaraman, Citation2013).

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to determine the availability and nature of early detection and intervention services for children with hearing loss in developing Western and South Asian countries. As a result of screening both journal articles and grey literature, 31 sources were identified which contained qualitative and quantitative information about the availability and nature of early detection and intervention services for children with hearing loss in Western and South Asia. The main finding was that some services are available for identification, diagnosis, and intervention for children with hearing loss in developing countries of Western and South Asia. However, these services are still in the early stages of development, and JCIH principles and guidelines are not fully implemented due to several factors. These factors include: NHS is not always available in all hospitals; amplification devices and cochlear implants have limited availability; and there are barriers to accessing therapy services due to prolonged waits, geographic location, and financial difficulties. This finding is in contrast to most developed countries (e.g., the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia) which follow the recommendation of early UNHS as a standard of care, to ensure that children with hearing loss are detected, diagnosed, and enrolled into early intervention services to optimize outcomes in different domains (Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, Citation2019; Punch, Van Dun, King, Carter, & Pearce, Citation2016; van Dyk, Swanepoel, & Hall, Citation2015).

A key finding of this scoping review is that the majority of the developing countries in Western and South Asia have only partially implemented NHS. This is due to screening not always being available in hospitals, shortages of trained staff, and the absence of unified protocols for hearing screening. Such variations suggest that there is no consistent approach when conducting newborn hearing screening. As a result, many children are left unscreened for hearing loss or receive a delayed diagnosis. Conversely, in developed countries a range of professionals, including midwives, physicians, nurses, and technicians, have been trained to perform newborn hearing screening (WHO, Citation2009). Furthermore, in developed countries newborn hearing screening is soon after birth, ensuring that all babies are screened before discharge (WHO, Citation2009). In the UK, if a newborn is discharged before NHS, a letter-based appointment is sent to the parent to attend for screening (WHO, Citation2009). A US study demonstrates the importance of applying early detection, through its assessment of the implementation of a UNHS programme in Colorado, which has highlighted that universal screening has effectively reduced the average age of identification from two years to within the first month of life (Yoshinaga-Itano, Citation2003). Moreover, early detection increases the likelihood of children with hearing loss being enrolled in early intervention services, resulting in better language and speech development outcomes (Anne, Lieu, & Kenna, Citation2018; Yoshinaga-Itano, Citation2003; Yoshinaga-Itano et al., Citation2000). Countries in Western and South Asia could consider similar strategies to those adopted in developed countries in order to ensure all children are screened in line with the guidelines.

This scoping review has shown that some developing countries in Western and South Asia provide amplification devices for children with hearing loss. However, there is a pattern of delayed fitting of appropriate amplification devices. Children with hearing loss in developing countries in Western and South Asia who are candidates for cochlear implants have to undergo a trial period, during which their suitability for a cochlear implant is determined (H. Alyami et al., Citation2016). This delay in protocol may cause developmental delay for language acquisition. JCIH (Citation2019) recommends cochlear implant surgery for infants around 12 month of age or younger, to increase the chances of enhanced speech and language, in line with their normal hearing peers. Studies emphasize that it is important for children with hearing loss to have access to amplification soon after diagnosis, alongside early language interventions, to optimize outcomes (Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, Citation2019; Moeller, Citation2000; Robinshaw, Citation1995). Further research is needed to explore how developing countries can be supported to reduce waiting periods and ensure children with hearing loss receive appropriate amplification devices in line with international guidelines.

In addition to time delay, other factors contributing to limited access to amplification devices have been identified in this scoping review, namely financial and geographic factors. These factors restrict many families of children with hearing loss to access services and thereby gain an amplification device (Neumann, Euler, Chadha, & White, Citation2020). Another factor influencing the outcome of interventions is the type of amplification device available. Whilst some organizations provide hearing aids free of cost, some children may need a different form or type of amplification device, such as cochlear implant. Despite the availability of devices and therapy services, families of children with hearing loss in developing countries across studies reported being unaware of free services, long wait times before commencing therapy, old resources used in therapy sessions, geographic barriers, and a lack of access to multidisciplinary teams. In contrast, barriers to accessing early intervention in developed countries are associated with children with mild hearing loss; unilateral hearing loss; and premature babies and other developmental delay (McLean, Ware, Heussler, Harris, & Beswick, Citation2019; Rosenberg, Zhang, & Robinson, Citation2008).

Whilst this scoping review has provided important insights regarding the nature and availability of early intervention services for children with hearing loss in developing Western and South Asian countries, some limitations are acknowledged. Only peer-reviewed articles and grey-literature sources that were written in English were included. Other relevant articles and resources may exist in languages other than English. Additionally, some studies were excluded in this scoping review due to lack of information regarding the age group of children in the study. It is also acknowledged that some countries may have services available that aren’t reported in the peer-reviewed or grey literature. Further research is needed to explore the gaps in early intervention services so that targeted strategies can be used to improve the early intervention services for children with hearing loss, and ultimately work towards JICH recommendations and guidelines to optimize opportunities for children with hearing loss in developing countries to match their normal-hearing peers.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to explore the early intervention services for children with hearing loss in developing countries in Western and South Asia. The findings of this scoping review demonstrated that UNHS programmes are not always available across the region resulting in later detection and intervention services for children with hearing loss. This review found that early intervention services and its nature of delivery have been affected, resulting in a delay in both detection and intervention due to the availability of UNHS and staff in the hospital, variability of hearing screening protocols, lack of awareness, and the accessibility and availability of the amplification devices and/or needed therapy intervention programmes. Few papers explicitly explored the validity of hearing screening as a tool were exclusively investigating and not the nature of services delivered for children, which makes it challenging to understand the availability of early intervention services for children with hearing loss. Further research that targets the nature and availability of those delivered services for children and their families in Western and South Asia is required.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al-Sayed, A. A., & AlSanosi, A. (2017). Cochlear implants in children: A cross-sectional investigation on the influence of geographic location in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 24(2), 118–121. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_142_15.

- Al-Shawi, Y. A., Alrawaf, F. K., Al-Gazlan, N. S., Al-Qahtani, M. M., & Almuhawas, F. A. (2020). Relationship between proximity to a cochlear implant center and early presentation in children with congenital hearing loss. Saudi Medical Journal, 41(3), 314–317. doi:10.15537/smj.2020.3.24918

- Acar, B., Ocak, E., Acar, M., & Kocaöz, D. (2015). Comparison of risk factors in newborn hearing screening in a developing country. Turkish Journal of Pediatrics, 57(4), 334–338. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84969129971&partnerID=40&md5=0a0a735aa530ac974d3c34ca4b9816ac

- Acar, F. M., Turan, Z., & Uzuner, Y. (2020). Being the father of a child who Is deaf or hard of hearing: A phenomenological study of fatherhood perceptions and lived experiences in the Turkish context. American Annals of the Deaf, 165(1), 72–113. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26983928

- Alanazi, A. A. (2020). Referral and lost to system rates of two newborn hearing screening programs in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 6(3), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns6030050

- Alduhaim, A., Purcell, A., Cumming, S., & Doble, M. (2020). Parents’ views about factors facilitating their involvement in the oral early intervention services provided for their children with hearing loss in Kuwait. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 128, 109717. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.109717

- Alkahtani, R., Rowan, D., Kattan, N., & Alwan, N. A. (2019). Age of identification of sensorineural hearing loss and characteristics of affected children: Findings from two cross-sectional studies in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 122, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.03.019

- Alkhamra, R. A. (2015). Cochlear implants in children implanted in Jordan: A parental overview. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 79(7), 1049–1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.04.025

- Aloqaili, Y., Arafat, A. S., Almarzoug, A., Alalula, L. S., Hakami, A., Almalki, M., & Alhuwaimel, L. (2019). Knowledge about cochlear implantation: A parental perspective. Cochlear Implants International, 20(2), 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2018.1548076

- Alyami, H., Soer, M., Swanepoel, A., & Pottas, L. (2016). Deaf or hard of hearing children in Saudi Arabia: Status of early intervention services. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 86, 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.04.010

- Anne, S., Lieu, J. E. C., & Kenna, M. A. (2018). Pediatric sensorineural hearing loss: Clinical diagnosis and management. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing, Inc.

- Ansari, M. S. (2014). Assessing parental role as resource persons in achieving goals of early detection and intervention for children with hearing impairment. Disability, CBR & Inclusive Development, 25(4), 84–98. https://doi.org/10.5463/dcid.v25i4.356.

- Ardic, C. (2017). Newborn Hearing Screening Outcomes From Rize; Turkey. Konuralp Medical Journal / Konuralp Tip Dergisi, 9(1), 41–45. https://doi.org/10.18521/ktd.292877.

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Ayas, M., & Yaseen, H. (2021). Emerging data from a newborn hearing screening program in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Pediatrics, 2021, 2616890. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2616890

- Bishnoi, R., Baghel, S., Agarwal, S., & Sharma, S. (2019). Newborn hearing screening: Time to act! Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery, 71(Suppl. 2), 1296–1299. doi:10.1007/s12070-018-1352-1

- Ching, T. Y. C., Crowe, K., Martin, V., Day, J., Mahler, N., Youn, S., … Orsini, J. (2010). Language development and everyday functioning of children with hearing loss assessed at 3 years of age. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12(2), 124–131. doi:10.3109/17549500903577022

- Community Care Population Health Principal Committee. (2013). National framework for neonatal hearing screening. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/neonatal-hearing-screening

- Covidence systematic review software. (2022). www.covidence.org

- Davis, K., Drey, N., & Gould, D. (2009). What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(10), 1386–1400. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010

- Figueras, B., Edwards, L., & Langdon, D. (2008). Executive function and language in deaf children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 13(3), 362–377. doi:10.1093/deafed/enm067

- Galhotra, A., & Sahu, P. (2019). Challenges and solutions in implementing hearing screening program in India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 44(4), 299–302. doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_73_19

- George, S. A., Alawadhi, A., & Al Reefy, H. (2016). Newborn hearing screening. Bahrain Medical Bulletin: BMB, 38(3), 148–150. https://doi.org/10.12816/0047488

- Jeyaraman, J. (2013). Practices in habilitation of pediatric recipients of cochlear implants in India: A survey. Cochlear Implants International, 14(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1179/1754762812Y.0000000005

- Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. (2019). Year 2019 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 4(2), 1–44. doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_73_19

- Kolethekkat, A. A., Al Abri, R., Hlaiwah, O., Al Harasi, Z., Al Omrani, A., Sulaiman, A. A., Al Bahlani, H., Al Jaradi, M., & Mathew, J. (2020). Limitations and drawbacks of the hospital-based universal neonatal hearing screening program: First report from the Arabian Peninsula and insights. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 132(109926), 109926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.109926

- Kulkarni, K. A., & Gathoo, V. S. (2017). Parent empowerment in early intervention programmes of children with hearing loss in Mumbai, India. Disability CBR & Inclusive Development, 28(2), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.5463/dcid.v28i2.550

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- McLean, T. J., Ware, R. S., Heussler, H. S., Harris, S. M., & Beswick, R. (2019). Barriers to engagement in early intervention services by children with permanent hearing loss. Deafness & Education International, 21(1), 25–39. doi:10.1080/14643154.2018.1528745

- Merugumala, S. V., Pothula, V., & Cooper, M. (2017). Barriers to timely diagnosis and treatment for children with hearing impairment in a southern Indian city: a qualitative study of parents and clinic staff. International Journal of Audiology, 56(10), 733–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2017.1340678

- MDG. (2014). Millennium development indicators – United Nations. United Nations. https://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Host.aspx?Content=Data/snapshots.htm

- Moeller, M. P. (2000). Early intervention and language development in children who are deaf and hard of hearing. Pediatrics, 106(3), E43–E43. doi:10.1542/peds.106.3.e43

- Neumann, K., Euler, H. A., Chadha, S., & White, K. R. (2020). A survey on the global status of newborn and infant hearing screening. Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 5(2), 63–84.

- Newton, V. E. (2009). Paediatric audiological medicine (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Paul, A., Prasad, C., Kamath, S. S., Dalwai, S., Nair, M. K. C., & Pagarkar, W. (2017). Consensus statement of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics on newborn hearing screening. Indian Pediatrics, 54(8), 647–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-017-1128-9

- PHCC. (2021). Audiology. https://www.phcc.gov.qa/Home

- Punch, S., Van Dun, B., King, A., Carter, L., & Pearce, W. (2016). Clinical experience of using cortical auditory evoked potentials in the treatment of infant hearing loss in Australia. Seminars in Hearing, 37(1), 36–52. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1570331

- Robinshaw, H. M. (1995). Early intervention for hearing impairment: Differences in the timing of communicative and linguistic development. British Journal of Audiology, 29(6), 315–334. doi:10.3109/03005369509076750

- Rosenberg, S. A., Zhang, D., & Robinson, C. C. (2008). Prevalence of developmental delays and participation in early intervention services for young children. Pediatrics, 121(6), e1503–e1509. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1680

- Sachdeva, K., & Sao, T. (2017). Outcomes of newborn hearing screening program: A hospital based study. Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery, 69(2), 194–198. doi:10.1007/s12070-017-1062-0

- Saki, N., Bayat, A., Hoseinabadi, R., Nikakhlagh, S., Karimi, M., & Dashti, R. (2017). Universal newborn hearing screening in southwestern Iran. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 97, 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.03.038

- Sharma, Y., Bhatt, S. H., Nimbalkar, S., & Mishra, G. (2018). Non-compliance with neonatal hearing screening follow-up in rural western India. Indian Pediatrics, 55(6), 482–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-018-1338-9

- Shojaee, M., Kamali, M., Sameni, S. J., & Chabok, A. (2013). Parent satisfaction questionnaire with neonatal hearing screening programs: Psychometric properties of the Persian version. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 77(11), 1902–1907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.09.007.

- Sukumaran, T. U. (2011). Newborn hearing screening program. Indian Pediatrics, 48(5), 351–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-011-0079-9

- Thompson, D. C., McPhillips, H., Davis, R. L., Lieu, T. A., Homer, C. J., & Helfand, M. (2001). Universal newborn hearing screening. JAMA, 286(16), 2000–2010. doi:10.1001/jama.286.16.2000

- Uhlén, A. M. I. (2020). Summary: Hearing screening Turkey. Karolinska Institutet. Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm Sweden.

- UNBHS Program. (2021). Health affairs. https://www.ngha.med.sa/English/MedicalCities/AlRiyadh/CIP/Pages/UNBHSP.aspx

- United Nations. (2021). World Economic Situation Prospects.

- van Dyk, M., Swanepoel, D. W., & Hall, J. W. (2015). Outcomes with OAE and AABR screening in the first 48 h—implications for newborn hearing screening in developing countries. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 79(7), 1034–1040. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.04.021

- WHO. (2009). Newborn and infant hearing screening: Current issue and guiding principles for action. https://www.who.int/blindness/publications/Newborn_and_Infant_Hearing_Screening_Report.pdf?ua=1

- WHO. (2018). Addressing the rising prevalence of hearing loss. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/addressing-the-rising-prevalence-of-hearing-loss.

- Winskel, H. (2006). The effects of an early history of otitis media on children’s language and literacy skill development. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(4), 727–744. doi:10.1348/000709905X68312

- Wolff, R., Hommerich, J., Riemsma, R., Antes, G., Lange, S., & Kleijnen, J. (2010). Hearing screening in newborns: Systematic review of accuracy, effectiveness, and effects of interventions after screening. Archives of Disease in Childhood, doi:10.1136/adc.2008.151092

- World Health Organization. (2021). World report on hearing. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Yoshinaga-Itano, C. (2003). Early intervention after universal neonatal hearing screening: Impact on outcomes. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 9(4), 252–266. doi:10.1002/mrdd.10088

- Yoshinaga-Itano, C., Coulter, D., & Thomson, V. (2000). The Colorado newborn hearing screening project: Effects on speech and language development for children with hearing loss. Journal of Perinatology, 20(8 Pt 2), S132–S137. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7200438

- Yoshinaga-Itano, C., Sedey, A. L., Coulter, D. K., & Mehl, A. L. (1998). Language of early- and later-identified children with hearing loss. Pediatrics, 102(5), 1161. doi:10.1542/peds.102.5.1161

- Yoshinaga-Itano, C., Sedey, A. L., Mason, C. A., Wiggin, M., & Chung, W. (2020). Early intervention, parent talk, and pragmatic language in children with hearing loss. Pediatrics, 146(Suppl. 3), S270–S277. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0242F

- Zaitoun, M., & Nuseir, A. (2020). Parents’ satisfaction with a trial of a newborn hearing screening programme in Jordan. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 130(109845), 109845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.109845