ABSTRACT

Progress of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) services within the South African context lags behind that made by high-income countries internationally. Implementation of EHDI services in this context faces many challenges that underscore the need to ensure contextualized intervention approaches that meet the needs of South Africa’s linguistically and culturally diverse population. The aim of the current study was to describe caregivers’ expectations of EHDI services, and to evaluate the success and/or failure of the EHDI services in relation to these expectations. To achieve this aim, in-person, telephonic and videoconferencing narrative interviews were conducted with nine caregivers of children who are Deaf-or-Hard-of-Hearing (DHH), and analysed through reflexive thematic analysis. The following themes and sub-themes emerged from the narrative interviews: (1) expectations of the EHDI process (‘early detection of hearing loss and ‘EHDI should be accessible’), and (2) expectations for the outcomes of EHDI services (‘age-appropriate acquisition of spoken language’, ‘mainstream education’, and ‘further education and independence’). These themes speak to concerns with the entire EHDI process from detection to intervention, including continuity of care. In order to ensure effective and sustainable EHDI services within the South African context; caregivers’ expectations should be used to inform service provision and to guide best practice. Furthermore, these findings suggest a need to implement wide spread, integrated, and inter-disciplinary EHDI services that are linguistically and culturally responsive and relevant; with caregivers and families forming a crucial part of the programmes.

Introduction

Children progress through multiple stages of speech and language development during their first year, from perceiving and vocalizing speech sounds to producing the first word at 12 months of age (Gmmash & Faquih, Citation2022). However, for a child who is Deaf or Hard-of-Hearing (DHH) that is not always the case. The hearing loss results in incomplete access to spoken language, leading to negative effects on the understanding and development of spoken language (Wang & Engler, Citation2011; Maluleke, Khoza-Shangase, & Kanji, Citation2019). Over the last decade, high-income countries (HICs) have demonstrated that through Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) programmes which include benchmark indicators of screening hearing before one month of age, diagnosing the hearing loss before three months of age, and enrolment in early intervention (EI) service before six months of age; children who are DHH can develop optimal spoken language abilities, thus minimizing or reversing the negative effects of an unidentified hearing loss (DesJardin et al., Citation2014; Fulcher, Purcell, Baker, & Munro, Citation2012; JCIH, Citation2007; Moeller & Tomblin, Citation2015; Umat, Mukari, Nordin, Annamalay, & Othman, Citation2018). Furthermore, great strides in hearing technologies have contributed towards language development trajectories that would have been unattainable in previous eras for these children (Szarkowski, Young, Matthews, & Meizen-Derr, Citation2020).

However, despite being classified as an upper-middle income country within the low-and-middle income country (LMIC) category, South Africa lags far behind HICs in terms of progress made in EHDI programmes (Mustapha, Citation2023; Naidoo & Khan, Citation2022; World Bank, Citation2021). Universal implementation of EHDI and adherence to the Health Professions Council of South Africa’s (HPCSA) (Citation2018) guidelines of screening hearing no later than six weeks, diagnosing the hearing loss before four months and enrolment in EI services no longer than eight months of age; are not yet a lived reality in this context (Kanji & Opperman, Citation2015; Khoza-Shangase, Citation2019). This is due to documented challenges, including differences between the public and private healthcare sectors, inadequate human resources, lack of political will, poor social determinants of health, high burden of disease, and lack of resource allocation for successful and national implementation of universal newborn hearing screening (UNHS) (Kanji & Khoza-Shangase, Citation2016; Khoza-Shangase & Kanji, Citation2021). These challenges are not unique to the South African context or to childhood hearing loss, and have been identified in various other LMICs and across numerous diseases and illnesses (Weiss & Pollack, Citation2017).

In EHDI, the challenges described above underscore the need to ensure that context-specific studies are conducted to guide best practice that is relevant to South Africa’s contextual realities (Khoza-Shangase, Citation2021; Khoza-Shangase, Kanji, Petrocchi-Bartal, & Farr, Citation2017; Kanji & Khoza-Shangase, Citation2021). Contextualized intervention approaches would also facilitate family-centred early intervention (FCEI), which aligns with HPCSA’s EHDI guidelines (HPCSA, Citation2018; Khoza-Shangase & Kanji, Citation2021; Maluleke, Chiwutsi, & Khoza-Shangase, Citation2021a). FCEI is a family-professional partnership that places the needs of the child in the context of their family to optimize the child’s developmental outcomes (Iversen, Shimmel, Ciacere, & Prabhakar, Citation2003; Maluleke et al., Citation2021a; MacKean, Thurston, & Scott, Citation2005). This approach recognizes the role families and caregivers play in the implementation, integration and carry-over of care (Khoza-Shangase, Citation2022; Maluleke et al., Citation2021a; Moeller, Carr, Seaver, Stredler-Brown, & Holzinger, Citation2013). Furthermore, FCEI recognizes caregivers as important co-drivers of any intervention programme, facilitates active caregiver engagement and involvement, and promotes self-efficacy in caregivers. Active caregiver engagement and involvement are essential in EI and result in higher rates of follow-through, greater participation in and adherence to EHDI, improved outcomes for children with hearing loss, and mitigation of the inequities associated with access to healthcare (HPCSA, Citation2018; Khoza-Shangase, Citation2022; Moeller et al., Citation2013; Yoshinaga-Itano, Citation2014).

It is through the family that children are born, socialized and cared for until they become independent (Department of Social Development, Citation2013). Caregivers and families thus provide the most effective and economical system for fostering and sustaining the child’s development (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1993; Maluleke et al., Citation2023; Mantri-Langeveldt, Dada, & Boshoff, Citation2019). Caregivers and families also provide a linguistic and cultural environment in which children can develop (Balton, Uys, & Alant, Citation2019; Schlebusch, Samuels, & Dada, Citation2016). Hence, provision of EHDI services in the family’s home language would mitigate the language barriers experienced by caregivers when accessing EHDI services (Khoza-Shangase, Citation2019). Furthermore, linguistically and culturally congruent EHDI services would ensure that the child who is DHH is not distanced linguistically and culturally from the rest of their family or community (HPCSA, Citation2018; Khoza-Shangase & Mophosho, Citation2018).

South Africa is characterized by a linguistically and culturally diverse population (Statistics South Africa, Citation2016). However, EHDI services are offered predominantly in English, owing to a largely white, female, English- or Afrikaans-speaking staff complement (Khoza-Shangase, Citation2019; Pillay, Tiwari, Khathard, & Chikte, Citation2020). This staff complement does not represent the linguistic and cultural diversity of the South African population (Pascoe & Norman, Citation2011). Global evidence on health indicators reveals that patients who do not belong to the dominant language and cultural group experience poorer health outcomes than patients who do (Flood & Rohloff, Citation2018; Steinberg, Valenzuela-Araujo, Zickafoose, Kieffer, & DeCamp, Citation2016). South Africa is no exception (Mtimkulu, Khoza-Shangase, & Petrocchi-Bartal, Citation2023). Although English is spoken at home by only 10% of the population (Statistics South Africa, Citation2016), it is the dominant language in the country and is viewed as a language of power and prestige (Pascoe, Klop, Mdlalo, & Ndhambi, Citation2018). As a result, 11 million South Africans do not access healthcare services in their home language (Statistics South Africa, Citation2016; Mophosho, Citation2018). This situation does not reflect the needs of South Africa, and the implementation of EHDI is thus not responsive or receptive to the needs of the population in this context.

In recent years, literature has demonstrated that for EHDI services to be effective, it is not enough to consider the availability, quality and equity of care provided, it is also necessary to consider the adoption of the FCEI approach (Deng, Finitzo, & Aryal, Citation2018; Khoza-Shangase, Citation2019, Citation2022). Although there is an increasing awareness of caregivers’ role in EI, limited attention is given to their opinions, their views, and their role in the EHDI process, by both the clinical and the research communities (Khoza-Shangase, Citation2019). Caregivers are the individuals within the child’s family who play the most significant role in day-to-day child rearing and caregiving (Maluleke, Khoza-Shangase, & Kanji, Citation2021b; Masuku & Khoza-Shangase, Citation2018). Hence, understanding their expectations and providing EI that aligns with those expectations might ultimately contribute to positive patient outcomes (Fitzpatrick, Angus, Durieux-Smith, Graham, & Coyle, Citation2007; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2016). The current study therefore aimed to describe caregivers’ expectations of the EHDI process from detection to intervention, and to evaluate the success and/or failure of the EHDI process in relation to caregivers’ expectations.

This paper forms part of a larger research project entitled ‘Family-Centred EHDI: Caregivers’ experiences and evaluation of the process and practices in the South African context’, describing the first steps in formulating a framework for FC-EHDI for children with hearing loss within the South African context.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

Prior to the commencement of this study, ethical clearance was obtained from the university’s Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) (Protocol Number: H19/06/16). The work also adhered to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revized in 2013 (World Medical Association, Citation2013).

Study design

Results in the current paper are based on the narrative interviews that were conducted as part of the mixed methods convergent design employed in phase 1 of the main study.

Participants

In order to gain access to the participants, the first author obtained written permission from two EI preschool centres for children with developmental delay and disabilities, including hearing loss. The written permission allowed the first author access to the preschool records in order to identify potential participants for the current study. Subsequently, posters outlining the study, the recruitment strategy, participant inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data collection methods were placed in the reception area of each EI preschool centre.

The EI preschool centres also distributed flyers detailing the study to caregivers of former learners. Once a caregiver had indicated interest in being recruited to participate in the study, the first author was granted access to their child’s preschool file.

A small number of participants is recommended for narrative interviews in order to ensure that the researchers obtain in-depth information about the research question, which is not achievable with a large sample size (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2018). Participants were recruited telephonically to participate in the study using non-probability sampling until data saturation was reached. Nine caregivers of children who are DHH participated in the current study. Caregivers met the following inclusion criteria:

Caregiver of a child with hearing loss.

Caregiver of a child diagnosed with a mild to profound, bilateral, or unilateral hearing loss.

Caregiver of a child who was enrolled in an EI preschool centre in Gauteng, South Africa, between 2010 and 2020.

The participants’ socio-demographic profile is summarized in . All the participants were female, with a mean age of 39 years at the time of the study. Five of the participants were Black (African), two were White, one participant was Coloured (Mixed Race), and one participant was Indian, based on the race classification system used in South Africa. Two of the participants each had two children who had been diagnosed with hearing loss. This brought the total number of children the nine participants in the study to 11.

Table 1. Participants caregivers’ socio-demographic profile.

The demographic and audiological profile of children who are DHH is summarized in . Participants were caregivers of children with a mean age of 10.2 years and an age range of between six years and 15 years at the time of the study. Of the children, seven were male and four were female. The children had been diagnosed with hearing loss at a mean age of 12 months, with the age range of between zero and 30 months. All the children presented with an early onset bilateral hearing loss and had been fitted with hearing aids or cochlear implants, or both.

Table 2. Demographic and audiological profile of children who are DHH.

Data collection

Data was collected using narrative interviews, with the interview schedule reflected in Box 1 below.

Box 1: Interview script

Tell me YOUR story.

What were your expectations of the EHDI process?

What were the successes and failures of this process based on your experience?

- What do you think worked well or did not work so well with the EHDI process based on your experience?

What are the facilitators and barriers to the EHDI process?

- What made the EHDI process work well and what made it not work so well?

How satisfied were you with the services that you received?

In-person, telephonic and videoconferencing interviews were conducted to collect the data. The study had aimed to conduct data collection through in-person interviews only; however, these plans had to be changed to accommodate COVID-19 restrictions (National Department of Health, Citation2020). The in-person interviews were conducted during January and February 2020, prior to the World Health Organisation (WHO) declaring COVID-19 a pandemic (WHO, Citation2020). The telephonic and videoconferencing interviews were conducted between March 2020 and March 2021.

Five interviews were conducted in English, two interviews in Setswana, one interview in SeSotho, and one interview in IsiZulu, in accordance with the participants’ preferences. The lead researcher conducted all the interviews and is proficient in all these South African languages, hence there was no need for an interpreter.

Data analysis

The narrative interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data collection and data analysis were conducted simultaneously in order to ensure that participant recruitment and data collection were discontinued once data saturation had been reached (Saunders et al., Citation2018). All the interviews were anonymized, with a participant number being allocated for participants and a pseudonym for the children. Reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyse the narrative interviews. For all interviews conducted in an African language, two bilingual translators translated the recordings into English and another bilingual translator back-translated the interview transcript into the source language. Plans to use transliteration were in place, in case no immediate meaning was found in English (Vaismoradi, Jones, Turunen, & Snelgrove, Citation2015), but this did not occur.

Themes that were identified from the current data were analysed using the following guidelines recommended by Braun and Clarke (Citation2013; Citation2020):(a) familiarization with the data, (b) generating initial codes, (c) generating themes, (d) reviewing potential themes, (e) defining and naming themes, and (f) producing the report. Representative verbatim quotations were used in the write-up of the study to support the presented findings.

Rigour

Reliability and validity are two key aspects of all research (Cypress, Citation2017; Polit & Beck, Citation2012). Rigour in qualitative research equates to the concepts of reliability, validity and all the necessary components of quality (Cypress, Citation2017). In order to prevent bias and intersubjective understanding of the findings, all the researchers were involved in the analysis (Vaismoradi et al., Citation2015; Wertz et al., Citation2011). Reflexive thematic analysis is considered a reflection of the researcher’s reflective and thoughtful engagement with the data and their reflexive and thoughtful engagement with the analytic process; thus, involvement of all the researchers during the analysis process allowed for exploration of multiple assumptions or interpretations of the data, and richer interpretation of the meaning of the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019; Byrne, Citation2022). Furthermore, a rich description of the participants and the children who are DHH is provided in order to increase transferability (Polit & Beck, Citation2012).

Results

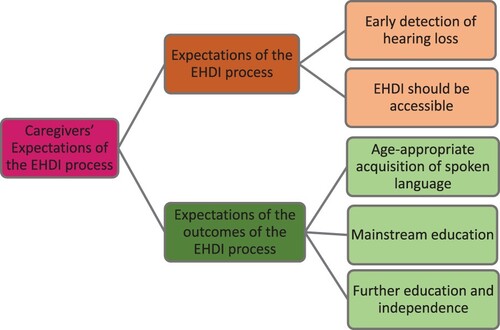

Two key themes pertaining to caregivers’ expectations of EHDI were identified from the reflexive thematic analysis namely; expectations of the EHDI process and expectations of the outcomes of EHDI services. provides a graphic illustration of these themes and their sub-themes.

reflects the themes, sub-themes and supporting quotations that were identified from the narrative interview data. All of these themes and sub-themes are presented below in relation to the success and/or failure of the EHDI services in meeting caregivers’ expectations.

Table 3. Themes, Sub-themes and corresponding quotations

Theme 1: expectations of the EHDI process

Participants’ expectations of the EHDI process are presented in terms of the following sub-themes: (a) early detection of hearing loss; and (b) EHDI services should be accessible.

Early Detection of Hearing Loss. The first sub-theme that was identified for expectations of the EHDI process was caregivers’ expectation that healthcare professionals (HCPs) detect their child’s hearing loss early. EHDI services failed to meet caregivers’ expectations in this regard. Four of the participants had discussed with various HCPs their concerns about to their child’s not reacting to loud sounds or observed delayed speech and language milestones; however, the HCPs had dismissed caregiver s’ concerns. Consequently, their child’s hearing loss was only detected at a later stage.

Two of the participants reported that they had been referred to and had attended numerous appointments with various HCPs before a diagnosis of hearing loss was made. Furthermore, seven of the 11 children presented with risk factors for hearing loss, including; prematurity, neonatal intensive unit stay, Waardenburg syndrome, jaundice and chronic otitis media.

Only two of the eleven children had reportedly received timely EHDI services because their older sibling had also presented with a hearing loss and their caregivers had insisted on hearing screening and hearing evaluation when they were born.

EHDI Services Should Be Accessible. The second sub-theme that was identified for expectations of the EHDI process was caregivers’ expectation that EHDI services would be accessible. However, EHDI services failed to meet caregivers’ expectations. Nine participant caregivers expressed frustration with the distance from their home to the health facility where they received EHDI services, the high cost of services, and/or the use of the English language throughout the EHDI process, which made access to EHDI services difficult.

For five of the nine participants EHDI services were situated far away from their homes. For three of these five participants, EHDI services were in areas that were hard-to-reach areas by public transport, which was the mode of transport available to them. Furthermore, for five of the participants, the high cost of EHDI services associated with audiology services, speech therapy services, amplification devices, and accessories such as FM systems made it difficult for them to access EHDI services. Only two participants received free EHDI services from state-owned hospitals in the public sector. The remaining seven participants received EHDI services from the private sector, and paid for these services directly (out-of-pocket) or through their medical aids. For one participant, the high cost of EHDI services resulted in their child not receiving EHDI services for a ‘few months’ because they could no longer afford to pay directly for the services.

In addition to distance and cost challenges, participants also expressed concern with the use of the English language throughout the EHDI process. Appointments for all EHDI services were conducted in English, despite English not being the first language for six out of the nine participants. The reason provided for the use of the English language was that available schools that cater for the needs of learners who are DHH used only English as a medium of instruction.

Theme 2: expectations of the outcomes of the EHDI process

Participants’ expectations of the EHDI process will be presented according to the following sub-themes: (a) age-appropriate acquisition of spoken language; (b) mainstream education; and (c) further education and independence.

Age-appropriate acquisition of spoken language. The first sub-theme that was identified regarding expectations of the outcomes of the EHDI process was caregivers’ expectation that their child would acquire age-appropriate spoken language when receiving EHDI services. EHDI services succeeded in meeting this expectation for only two of the 11 children, but failed to meet this expectation for the remaining nine children.

Only two of the 11 children received timely EHDI services and adequate acoustic input from their amplification devices to support the development of age-appropriate speech and language abilities. For four of the 11 children, despite receiving adequate acoustic input from their amplification devices to support speech and language development, late-enrolment in EHDI, among other factors which are beyond the scope of the current paper, resulted in delayed spoken language abilities; while for five of the children, limited audibility with their amplification devices and late-enrolment in EHDI, among other factors which are beyond the scope of the current paper, resulted in delayed spoken language abilities. Of the latter five children, three had to switch to South African Sign Language (SASL) as their first language and spoken language as their second mode of communication.

Mainstream education. The second sub-theme that was identified regarding expectations of the outcomes of the EHDI process was caregivers’ expectation that their child would be enrolled in a mainstream school. EHDI services succeeded in meeting this expectation for only one of the 11 children (who was enrolled in a mainstream school) but failed to meet this expectation for the remaining 10 children, one of whom was enrolled in a remedial school, and eight of whom were enrolled in Schools for Learners with Education Needs (LSEN Schools), which provide support for learners who experience barriers to learning.

One participant did not express an expectation regarding her child’s enrolment in a mainstream school. This participant reported that prior to receiving EHDI services for her child, she had not been aware that there were schools catering for children with hearing loss and as a result ‘would lose hope’ that her child would ever go to school. This participant’s child, at the time of the study, was enrolled in a remedial school where she was receiving instruction in English.

Further Education and Independence. The third sub-theme that was identified regarding expectations of the outcomes of the EHDI process was caregivers’ expectations for their child’s further education and independence. The failure or success of EHDI services in this regard is yet to be determined. For five of the nine participants, expectations regarding their child’s further education and independence included an expectation that their child would go to university and be able to provide for themselves as adults. Participants who expressed expectations regarding their child’s prospects also expressed concerns pertaining to their child’s speech and language abilities and/or their academic performance at school. However, these concerns were not limited to caregivers of children who use Sign Language, but were also expressed by caregivers of children enrolled in a remedial school or an LSEN school.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to describe caregivers’ expectations of the EHDI process and to evaluate the success and/or failure of these programmes in relation to caregivers’ expectations. All nine participants in the current study were female. The fact that the sample for the current study was an all- female sample is consistent with the hierarchical and gendered role-assignment in various patriarchal contexts such as South Africa (Maluleke et al., Citation2021b; Merumagamala, Pothula, & Cooper, Citation2017). Within these contexts, males are generally regarded as the heads of the family, and females play the most significant role in day-to-day child rearing and caregiving (Masuku & Khoza-Shangase, Citation2018). Furthermore, reports from similar patriarchal contexts suggest that these hierarchical and gendered role-assignments accord women limited power to acquire health information, to make decisions regarding health, and to take action to improve health, and health access (Conroy et al., Citation2016; Merumagamala et al., Citation2017). Thus, HCPs need to be cognisant of the complexity of contextual decision-making dynamics and explore ways of navigating this dynamic in clinical practice (Maluleke et al., Citation2021b); in order to ensure best practice within this context.

The narrative interviews conducted in the current study revealed two key expectations, namely; expectations of the EHDI process and expectations of the outcomes of EHDI services. With regard to expectations of the EHDI process, the first sub-theme of the study revealed caregivers’ expectations that HCPs would detect their child’s hearing loss when they raised concerns about their child’s failure to react to loud sounds or observed delayed speech and/or language milestones. However, EHDI services failed to meet this expectation. HCPs failed to detect the child’s hearing loss and consequently refer the child for a hearing evaluation. Furthermore, participants were referred to and attended numerous appointments with various HCPs before their child was diagnosed with a hearing loss. Findings in the current study are concerning and suggest a lack of awareness on the part of HCPs of childhood hearing loss, its signs and symptoms, and the availability of EHDI services in the South African context.

The current study’s findings that point to HCPs lack of awareness of these aspects are supported by Naidoo and Khan (Citation2022), whose study showed that there is a general lack of awareness and knowledge about EHDI services among some HCPs in the South African context. In a study by Khan and Joseph (Citation2020), 42% of primary healthcare nurses reported that they were not knowledgeable about the risk factors for hearing loss. Similar findings of HCPs lack of awareness of EHDI, childhood hearing loss, its signs and symptoms, and the availability of EHDI services have been reported in India, another LMIC. In a study by Yerraguntla, Ravi, and Gore’s (Citation2018), only 3.33% of doctors reported that they would refer a child to an audiologist for a hearing evaluation, while 23.33% reported that they would refer to a paediatrician and 76.67% reported that they would refer the child to an Ear-Nose-and-Throat specialist. Furthermore, the doctors were able to list the signs and symptoms of hearing loss including hyperbilirubinemia, low birth weight and family history; however, none of them included lack of or inconsistent responses to sounds or loud noises and delayed spoken language abilities on the list of signs and symptoms.

Nurses and doctors are the first point of contact within the healthcare system (Kieft, de Brouwer, Francke, & Delnoij, Citation2014; Khan, Joseph, & Adhikari, Citation2018). This is especially the case for the 85% (at least) of the South African population that accesses healthcare in the public sector (Khan et al., Citation2018; Khoza-Shangase & Kanji, Citation2021). The authors of the current paper thus maintain that HCPs’ failure to identify signs and symptoms of childhood hearing loss compromises the EHDI process. Until UNHS is realized within this context, audiologists need to advocate for and promote EHDI and NHS amongst HCPs (Khoza-Shangase & Kanji, Citation2021). Communication and collaboration between HCPs, in an interdisciplinary approach, are a crucial aspect of effective EHDI services (HPCSA, Citation2018; Naidoo & Khan, Citation2022) and would facilitate information sharing amongst HCPs and improved awareness of infant hearing loss, helping to develop referral pathways that would assist in earlier identification of infant and childhood hearing loss (Naidoo & Khan, Citation2022). Furthermore, an interdisciplinary approach of shared knowledge and skills for a common goal, will advance hearing health and developmental outcomes for children who are DHH, while pooling the necessary resources into an efficiently run healthcare system, as advocated by the World Health Organization (WHO, Citation2010, Citation2020).

The second sub-theme for caregivers’ expectations of the EHDI process was their expectation that the EHDI process would be accessible. However, EHDI services failed to meet this expectation, because caregivers had to travel long distances, often using public transport, to access EHDI services. Similarly, in a study by McLaren, Ardington, and Leibbrandt (Citation2014), distance from facilities posed a barrier for South Africans wishing to access healthcare. With specific reference to audiology in this context, Kanji and Khoza-Shangase (Citation2018) found that distance from healthcare services negatively influenced follow-up return rates in NHS programmes, while in Naidoo and Khan’s (Citation2022) study, caregivers identified the cost of transport as a barrier to EHDI.

Furthermore, the current study found that the high cost of EHDI services, amplification devices, and their accessories contributed to the failure of EHDI process to meet caregivers’ expectation of accessible EHDI. Similarly, Naidoo and Khan (Citation2022) found that, caregivers also identified the cost of the hearing evaluation in the private sector as a barrier to EHDI. According to Burger and Christian (Citation2020), affordability of healthcare remains a constraint within the South African context. Even when healthcare services are provided free of charge, the monetary and time costs of travel to healthcare facilities represent the cost of access to healthcare (Chimbidi et al., Citation2015).

EHDI services’ failure to meet caregivers’ expectations of accessible services with regard to distance and cost is not limited to EHDI services within the South African context. The South African Constitution provides for the right to healthcare services; however, being afforded the right to something does not necessarily translate into getting the service or the quality of care (Chiwire, Citation2016). South Africa is characterized by persistent inequitable quality of health services provision (de Villiers, Citation2021). Furthermore, the healthcare system faces a range of systemic and structural challenges, which include widespread inefficiencies, staff shortages, variability in skills sets between rural and urban areas, and suboptimal care levels of patient management (Khoza-Shangase, Citation2019).

In an effort to address these challenges, South Africa is introducing the National Health Insurance (NHI) system, with the goal of fostering healthcare reform to improve service provision and healthcare delivery for all socioeconomic groups, while also partnering with providers and organizations within the private sector in the delivery of healthcare (de Villiers, Citation2021). Though the NHI offers hope to the disadvantaged, it will not be ready soon, leaving the current healthcare arrangements, with their own vulnerabilities, needing an urgent revamp (Chiwire, Citation2016). Thus, current findings raise implications for improving access to healthcare services, such as EHDI, through improving affordability of healthcare and proximity to healthcare facilities.

One of the proposed models for improving healthcare access in resource-constrained contexts like South Africa is through tele-audiology (Swanepoel & Hall, Citation2010; Sebothoma, Khoza-Shangase, Masege, & Mol, Citation2021). Tele-audiology, a subset of telehealth, is the utilization of telecommunication technologies to reach patients, reduce barriers to the best healthcare, enhance patient access to healthcare practitioners, and spare patients from having to travel long distances to obtain high-quality care (Krupinski, Citation2015; Khoza-Shangase & Sebothoma, Citation2022). Increased efforts by the South African government towards information and communication technologies and the fourth industrial revolution, coupled with telehealth’s immense capabilities to increase access to healthcare services as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, make tele-audiology a viable option to improve access to EHDI within the South African context (Khoza-Shangase & Sebothoma, Citation2022; Maluleke & Khoza-Shangase, Citation2023; State of the Nation Address [SONA], Citation2020). However, South Africa is experiencing challenges with meeting the country’s electrical demands, resulting the implementation of various stages of power outages referred to as ‘load shedding’ (Laher et al., Citation2019; Wood, Citation2023). The current load shedding challenges pose a challenge to telehealth within this context. Thus, further deliberations on internet access and use, especially within the remote contexts which are supposed to gain the most benefit from these services, are essential.

In addition to distance and the high cost of services, use of the English language throughout the EHDI process resulted in EHDI services’ failure to meet caregivers’ expectation that EHDI services would be accessible. English was used as a ‘preferred’ language even though it was not the first language for six of the nine participants. South Africa has a richly diverse population in culture and language; clinical interactions should therefore be conducted using a mode or language of communication which patients and families can understand, especially where the core scope of function is in communication pathology (HPCSA, Citation2018; Khoza-Shangase, Citation2019; Khoza-Shangase & Mophosho, Citation2018). Using the language that the family can understand improves the degree of accurate recall and has significant implications for follow-up of treatment options, commitment and adherence to treatment recommendations, and improved health outcomes (Flood & Rohloff, Citation2018; Watermeyer, Kanji, & Sarvan, Citation2017; Watson & McKinstry, Citation2009). Thus, robust efforts to embrace linguistically- and culturally-congruent EHDI services are warranted in the South African context.

The second key theme that was identified from this study was caregivers’ expectations of outcomes of the EHDI process. The first sub-theme of caregivers’ expectation of the outcomes of the EHDI process was their expectation that their child would acquire age-appropriate spoken language once fitted with amplification devices. EHDI services failed to meet this expectation as only two of the 11 children developed age-appropriate spoken language abilities. Similar results are reported in studies conducted by Fitzpatrick et al. (Citation2007), and by Young and Tattersall (Citation2007), where caregivers showed high expectations of EHDI services in enabling their child to achieve what a child with normal hearing would achieve. Furthermore, in a study by Gilliver, Ching, and Sjahalam-King (Citation2013), caregivers expected that their child’s hearing loss would be easily and effectively managed by early fitting of amplification devices.

Early access to EHDI services is critical for children who are DHH to develop optimal speech and language development (Barr, Dally, & Duncan, Citation2019; MacKean et al., Citation2005). However, providing amplification at an early age is not sufficient to support positive developmental outcomes for children who are DHH, given the complexity of childhood hearing loss (Findlen, Malhorta, & Adunka, Citation2019; McCreery, Walker, & Spratford, Citation2015). There are multiple factors that influence development outcomes for children who are DHH, such as co-morbid medical, social and developmental factors. Thus, the effect of the timing of intervention is small compared to the aforementioned factors (Barr et al., Citation2019; Gilliver et al., Citation2013; Khoza-Shangase, Citation2021).

Caregivers’ expectation that their child would be able to hear once fitted with amplification devices and would subsequently develop age-appropriate spoken language abilities thus highlight the need for adequate informational counselling for caregivers. Caregivers’ expectations that amplification devices will result in their child achieving like a child with normal hearing may be misguided when considering the various factors that influence developmental outcomes for children who are DHH (Gilliver et al., Citation2013). Caregivers’ expectations must be realistic in relation to their child’s characteristics (Gilliver et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, perpetration of the belief that EI equates to normal development may place unnecessary guilt or pressure on those families where EI did not occur or fails to provide such outcomes. Thus, providing families with evidence-based information needs to be balanced in such a way as to provide information about the benefits of EI and its outcomes within a realistic framework (Gilliver et al., Citation2013).

The second sub-theme of caregivers’ expectations of outcomes of the EHDI process was their expectation that their child would be enrolled in a mainstream school. EHDI services failed to meet this expectation, as only one of the 11 children was enrolled in a mainstream school, two children were enrolled in a remedial school, and the remaining eight children were enrolled in LSEN schools. This finding confirms the notion that children who are DHH are primarily placed in the country’s limited number of special schools for the deaf, which contradicts the South African ethos of inclusive education (Human Sciences Resource Council, Citation2018; Khoza-Shangase, Citation2021).

The South African government has increased efforts to attain educational goals through initiatives such as Early Childhood Development (ECD) programmes and continuity of care for children who are DHH, from the health sector to the education sector, through access to therapeutic services that mitigate barriers to learning for these children. Furthermore, White Paper 6 (Department of Education, Citation2001) asserts that in order to make inclusive education a reality, a conceptual shift regarding the provision of support for learners who experience barriers to learning is required. However, we know far less about educating the child who is DHH than is commonly believed (Shaver, Marschark, Newman, & Marder, Citation2014). The current authors therefore agree with the assertion by Shaver et al. (Citation2014) that a better understanding of the effectiveness of various practices in regular and separate settings and how they are affected by complexities in child characteristics, is essential if we are to ensure that children who are DHH are placed in settings that are most enabling rather than administratively expedient.

The third sub-theme of caregivers’ expectations of outcomes of the EHDI process was their expectations for their child’s further education and independence. The success or failure of EHDI services’ in meeting this expectation remains to be seen. However, the findings of the current study relating to caregivers’ expectations for their child’s future prospects are warranted, given that early detection is key to initiating EI services and delayed provision of rehabilitation services can hinder a child’s overall development leading to long-term negative consequences (Gmmash & Faquih, Citation2022). These negative consequences pose a threat to quality of life with regard to education, employment, and integration in society for the child who is DHH (Khoza-Shangase, Citation2021; Yoshinaga-Itano, Citation2014).

Furthermore, reports from the South African context show that up to 70% of children with disabilities, which includes children who are DHH, are out of school, despite being of school-going age (Donohue & Bornman, Citation2014), while an estimated 93% of adults who are DHH are unemployed (Parliamentary Monitoring Committee, Citation2013). Current findings highlight an urgent need for the Departments of Health, Social Development and Basic Education to invest in initiatives that are aimed at properly resourcing, coordinating and managing the child with hearing loss from EHDI, ECD centres, and school through an integrated and collaborative approach that involves the child who is DHH, their family and EI professionals.

Limitations

The results are based on reports of events that occurred prior to the narrative interviews being conducted; thus, time might have influenced caregivers’ recall of their experiences. Furthermore, use of purposive sampling and inclusion of caregivers of children from EI preschools in Gauteng only is not representative of the general population of caregivers of children who are DHH in South Africa. It can therefore cannot be assumed that the findings of this study are representative of all caregivers and children who are DHH within the South African context. The results of the current study cannot be interpreted beyond the sampled population; however, they provide a firm foundation for further research. An investigation of caregivers’ expectations of EHDI services from different geographical locations and healthcare facilities is warranted.

Conclusion

Findings from this study revealed that EHDI services failed to meet caregivers’ expectations of (a) early detection of hearing loss; (b) accessible EHDI services; (c) age-appropriate acquisition of spoken language; and (d) enrolment in a mainstream school for the child who is DHH. These findings emphasize the need for context-specific solutions and strategies that will ensure that EHDI services are effective, sustainable, and evidence-based, and that they recognize caregivers as significant co-drivers of successful EHDI services. Furthermore, these findings highlight the need for implementation of wide-spread, integrated, and inter-disciplinary EHDI services that meets the needs of South Africa’s linguistically and culturally diverse population.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Balton, S., Uys, K., & Alant, E. (2019). Family-based activity settings of children in a low-income African context. African Journal of Disability, 8(0), a364. doi:10.4102/ajodv8i0364

- Barr, M., Dally, K., & Duncan, J. (2019). Service accessibility for children with hearing loss in rural areas of the United States and Canada. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 123, 15–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.04.028

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Bronfenbrenner, U.(1993). Ecological models of human development. In International encyclopedia of education, Vol. 3, 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier. Reprinted in: M. Hauvain, & M. Cole (eds). Readings on the development of children (2nd Ed). (pp. 37–43). New York: Freeman.

- Burger, R., & Christian, C. (2020). Access to health care in post-apartheid South Africa: Availability, affordability, acceptability. Health Economics, Policy and Law, 15(1), 43–55.

- Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke's approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56, 1391–1412. doi:10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Chimbidi, N., Bor, J., Newell, M. L., Tanser, F., Baltusen, R., Hontelez, J., … Bärnighausen, T. (2015). Time and money: The true costs of health care utilization for patients receiving “free” HIV/TB care and treatment in rural KwaZulu-Natal. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 70, e52–e60.

- Chiwire, P. (2016). Factors influencing access to healthcare in South Africa. Retrieved from http://www.peach.it/2016/10/factors-influencing-access-to-health-care-in-south-africa/

- Conroy, A. M., McGrath, N., van Rooyen, H., Hosegood, V., Johnson, M. O., Fritz, K., … Darbes, L. A. (2016). Power and the association with relationship quality in South African couples: Implications for HIV/AIDS interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 153, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.035

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Cypress, B. S. (2017). Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 36(4), 253–263. doi:10.1097/DCC.0000000000000253

- Deng, X., Finitzo, T., & Aryal, S. (2018). Measuring early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) quality across the continuum of care. The Journal of Electronic Health Data and Methods, 6(1), 1–8. doi:10.53341/egems.239

- Department of Education. (2001). Education white paper 6: Special needs education: Building an inclusive education and training system. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printer.

- Department of Social Development. (2013). White paper on families in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printer.

- DesJardin, J. L., Doll, E. R., Stika, C. J., Eisenberg, L. S., Johnson, K. J., Ganguly, D. H., … Henning, S. C. (2014). Parental support for language development during joint book reading for young children With hearing loss. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 35(3), 167–181. doi:10.1177/1525740113518062

- De Villiers, K. (2021). Bridging the health inequality gap: An examination of South Africa's social innovation in health landscape. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 10, 19. doi:10.1186/s40249-021-00804-9

- Donohue, D., & Bornman, J. (2014). The challenges of realising inclusive education in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 34(2), 1–14. doi:10.15700/201412071114

- Findlen, U. M., Malhorta, P. S., & Adunka, O. F. (2019). Parent perspectives on multidisciplinary pediatric hearing healthcare. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 116, 141–146. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.10.044

- Fitzpatrick, E., Angus, D., Durieux-Smith, A., Graham, I. D., & Coyle, D. (2007). Parents’ needs following identification of childhood hearing loss. American Journal of Audiology, 17, 38–49. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2008/005)

- Fitzpatrick, E., Grandpierre, V., Durieux-Smith, A., Gaboury, I., Coyle, D., Na, E., … Sallam, N. (2016). Children With mild bilateral and unilateral hearing loss: Parents’ reflections on experiences and outcomes. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 21(1), 34–43. doi:10.1093/deafed/env047

- Flood, D., & Rohloff, P. (2018). Indigenous languages and global health. The Lancet Global Health, 6(2), e134–e135. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30493-X

- Fulcher, A., Purcell, A. A., Baker, E., & Munro, N. (2012). Listen up: Children with early identified hearing impairment achieve age-appropriate speech/language outcomes by 3 years-of-age. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 333–355. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.09.001

- Gilliver, M., Ching, T. Y. C., & Sjahalam-King, J. (2013). When expectation meets experience: Parents’ recollections of and experiences with a child diagnosed with hearing loss soon after birth. International Journal of Audiology, 52(2), doi:10.3109/14992027.2013.825051

- Gmmash, A. S., & Faquih, N. O. (2022). Perceptions of healthcare providers and caregivers regarding procedures for early detection of developmental delays in infants and toddlers in Saudi Arabia. Children, 9(11), 1753. doi:10.3390/children9111753

- Health Professions Council of South Africa. (2018). Professional Board for Speech, Language and Hearing Professions Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Programmes in South Africa: Position Statement. Retrieved from http://www.hpcsa.co.za/Uploads/editor/UserFiles/downloads/speech/Early_Hearing_Detection_and_Intervention_(EHDI)_2018.pdf

- Human Sciences Research Council. (2018). SA is failing deaf and hard-of-hearing learners: Can a bilingual model of education be the solution to acquiring literacy? Retrieved from https://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/review/hsrc-review-oct-dec-2018/sa-is-failing-deaf-and-hard-of-hearing-learners

- Iversen, M. D., Shimmel, J. P., Ciacere, S. L., & Prabhakar, M. (2003). Creating a family-centered approach to early intervention services: Perceptions of parents and professionals. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 15(1), 23–31. doi:10.1097/01.PEP.0000051694.10495.79

- Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. (2007). Year 2007 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics, 120, 898–921.

- Kanji, A., & Khoza-Shangase, K. (2016). Feasibility of newborn hearing screening in a public hospital setting in South Africa: A pilot study. South African Journal of Communication Disorders, 63(1), e1–e8. doi:10.4102/sajcd.v63i1.150

- Kanji, A., & Khoza-Shangase, K. (2018). In pursuit of successful hearing screening: An exploration of factors associated with follow-up return rate in a risk-based newborn hearing screening programme. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics, 28(4), e56047. doi:10.5812/ijp.56047

- Kanji, A., & Khoza-Shangase, K. (2021). A paradigm shift in early hearing detection and intervention in South Africa. In K. Khoza-Shangase, & A. Kanji (Eds.), Early detection and intervention in audiology: An African perspective (pp. 3–14). Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Kanji, A., & Opperman, J. (2015). Audiological practices and findings post HPCSA position statement: Assessment of children aged 0-35 months. South African Journal of Child Health, 9(2), 38–40. doi:10.7196/SAJCH.778

- Khan, N. B., & Joseph, L. (2020). Healthcare practitioners’ views about early hearing detection and intervention practices in KwaZulu-natal, South Africa. South African Journal of Child Health, 14, 200–207.

- Khan, N. B., Joseph, L., & Adhikari, M. (2018). The hearing screening experiences and practices of primary health care nurses: Indications for referral based on high-risk factors and community views about hearing loss. African Journal of Primary Healthcare and Family Medicine, 10, e1–e11.

- Khoza-Shangase, K. (2019). Early hearing detection and intervention in South Africa: Exploring factors compromising service delivery as expressed by caregivers. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 118(December 2018), 73–78. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.12.021

- Khoza-Shangase, K. (2021). Confronting realities to early hearing detection in South Africa. In K. Khoza-Shangase, & A. Kanji (Eds.), Early detection and intervention in audiology: An African perspective (pp. 66–88). Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Khoza-Shangase, K. (2022). Early hearing detection and intervention: Considering the role of caregivers as key co-drivers within the African context. In K. Khoza-Shangase (Ed.), Preventive audiology: An African perspective (pp. 157–177). Cape Town: AOSIS Books.

- Khoza-Shangase, K., & Kanji, A. (2021). Best practice in South Africa for early hearing detection and intervention. In K. Khoza-Shangase, & A. Kanji (Eds.), Early detection and intervention in audiology: An African perspective (pp. 264–278). Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Khoza-Shangase, K., Kanji, A., Petrocchi-Bartal, L., & Farr, K. (2017). Infant hearing screening in a developing-country context: Status of 2 South African provinces. South African Journal of Child Health, 11(4), 159–163.

- Khoza-Shangase, K., & Mophosho, M. (2018). Language and culture in speech-language and hearing professions in South Africa: The dangers of a single story. South African Journal of Communication Disorders, 65, 1–7.

- Khoza-Shangase, K., & Sebothoma, B. (2022). Tele-audiology and preventive audiology: A capacity versus demand challenge imperative in South Africa. In K. Khoza-Shangase (Ed.). Preventive audiology: An African perspective (pp. 21–40). Cape Town: AOSIS Books. doi:10.1402/aosis.2022.BK209.02

- Kieft, R. A., de Brouwer, B. B., Francke, A. L., & Delnoij, D. M. (2014). How nurses and their work environment affect patient experiences of the quality of care: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 249.

- Krupinski, E. (2015). Innovations and possibilities in connected health. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 26(9), 761–767. doi:10.3766/jaaa.14047

- Laher, A. E., van Aardt, B. J., Craythorne, A. D., van Welie, M., Malinga, D. M., & Madi, S. (2019). ‘Getting out of the dark’: Implications of load shedding on healthcare in South Africa and strategies to enhance preparedness. South African Medical Journal, 109(12), 899–901. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.2019.v109i12.14322

- MacKean, G. L., Thurston, W. E., & Scott, C. M. (2005). Bridging the divide between families and health professionals’ perspectives on family-centred care. Health Expectations, 8(1), 74–85.

- Maluleke, N. P., Chiwutsi, R., & Khoza-Shangase, K. (2021a). Family-Centered early hearing detection and intervention. In K. Khoza-Shangase, & A. Kanji (Eds.), Early hearing detection and intervention in audiology (pp. 196–218). Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Maluleke, N. P., & Khoza-Shangase, K. (2023). Embracing videoconferencing interview applications beyond COVID-19: Scoping-review-guided implications for family-centered EHDI services in South Africa. Discover Health Systems. doi.10.1007/s44250-023-00033-x

- Maluleke, N. P., Khoza-Shangase, K., & Kanji, A. (2019). Communication and school readiness abilities of children with hearing impairment in South Africa: A retrospective review of early intervention preschool records. South African Journal of Communication Disorders, 66(1), a604. doi:10.4102/sajcd.v66i1.604

- Maluleke, N. P., Khoza-Shangase, K., & Kanji, A. (2021b). An integrative review of current practice models and/or process of family-centered early intervention for children who Are deaf or hard of hearing. Family & Community Health, 44, 59–71.

- Mantri-Langeveldt, A., Dada, S., & Boshoff, K. (2019). Measures for social support in raising a child with a disability: A scoping review. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45, 159–174.

- Masuku, K. P., & Khoza-Shangase, K. (2018). Spirituality as a coping mechanism for family caregivers of persons with aphasia. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 28(3), 245–248. doi:10.1080/14330237.2018.1475518

- McCreery, R. W., Walker, E. A., & Spratford, M. (2015). Understanding limited use of amplification in infants and children who are hard of hearing. Perspectives on Hearing and Hearing Disorders in Childhood, 25, 15–23.

- McLaren, Z. M., Ardington, C., & Leibbrandt, M. (2014). Distance decay and persistent health care disparities in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 1–9.

- Merumagamala, S. V., Pothula, V., & Cooper, M. (2017). Barriers to timely diagnosis and treatment for children with hearing impairment in a southern Indian city: A qualitative study of parents and clinic staff. International Journal of Audiology, 56(10), 733–739. doi:10.1080/14992027.2017.1340678

- Moeller, M., & Tomblin, J. (2015). An introduction to the outcomes of children with hearing loss study. Ear & Hearing, 36(1), 4S–13S. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000000210

- Moeller, M. P., Carr, G., Seaver, L., Stredler-Brown, A., & Holzinger, D. (2013). Best practices in family-centered early intervention for children who Are deaf or hard of hearing: An international consensus statement. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 18(4), 429–445. doi:10.1093/deafed/ent034

- Mophosho, M. (2018). Speech-language therapy consultation practices in multilingual and multicultural healthcare contexts: Current training in South Africa. African Journal of Health Professions Education, 10(3), 145. doi:10.7196/AJHPE.2018.v10i3.1045

- Mtimkulu, K., Khoza-Shangase, K., & Petrocchi-Bartal, L. (2023). Barriers and facilitators influencing hearing help-seeking behaviours for adults in a peri-urban community in South Africa: A preventive audiology study. Frontiers in Public Health, 11(1), 1095090. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1095090

- Mustapha, J. (2023). Upper-middle income Africa. https://futures.issafrica.org/geographic/income-groups/upper-middle-income-africa

- Naidoo, N., & Khan, N. B. (2022). Analysis of barriers and facilitators to early hearing detection and intervention in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South African Journal of Communication Disorders, 69(1), a839. doi:10.4102/sajcd.v69i1.839

- National Department of Health, South Africa. (2020). COVID-19 Disease: Infection prevention and control guidelines. National Department of Health. https://j9z5g3w2.stackpathcdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Covid-19-Infection-and-Prevention-Control-Guidelines-1-April-2020.pdf

- Parliamentary Monitoring Group. (2013). Disabled people's employment & learning challenges: Deputy Minister Women, Children & People with Disabilities, Departments of Public Service and Basic Education briefings. Pretoria, South Africa.

- Pascoe, M., Klop, D., Mdlalo, T., & Ndhambi, M. (2018). Beyond lip service: Towards human rights-driven guidelines for South African speech-language pathologists. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(1), 67–74. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1397745

- Pascoe, M., & Norman, V. (2011). Contextually-relevant resources in speech-language therapy and audiology in South Africa: Are there any? South African Journal of Communication Disorders, 58(1).

- Pillay, M., Tiwari, R., Khathard, H., & Chikte, U. (2020). Sustainable workforce: South African audiologists and speech therapists. Human Resources for Health, 18(1), 47. doi:10.1186/s12960-020-00488-6

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2012). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (9th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., … Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52, 1893–1907. doi:10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Schlebusch, L., Samuels, A. E., & Dada, S. (2016). South African families raising children with autism spectrum disorders: Relationship between family routines, cognitive appraisal and family quality of life. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 60(5), 412–423. doi:10.1111/jir.12292

- Sebothoma, B., Khoza-Shangase, K., Masege, D., & Mol, D. (2021). The use of tele-practice in assessment of middle ear function in adults living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery, 74(Suppl 2), 31183125. doi:10.1007/s12070-021-02876-x

- Shaver, D. M., Marschark, M., Newman, L., & Marder, C. (2014). Who Is where? Characteristics of deaf and hard-of-hearing students in regular and special schools. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 19(2), 203–219. doi:10.1093/deafed/ent056

- State of the Nation Address (SONA). (2020). President Cyril Ramaphosa; 2020 Sate of the Nation address, viewed February 25, 2020. https://www.gov.za/speeches/president-cyril-ramaphosa-2020-state-of-the-nation-address-13-feb-2020-0000

- Statistics South Africa. (2016). Community survey. https://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=6283. Published December 21, 2017. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Steinberg, E. M., Valenzuela-Araujo, D., Zickafoose, J. S., Kieffer, E., & Decamp, L. R. (2016). The “Battle” of managing language barriers in health care. Clinical Pediatrics, 55(4), 1318–1327. doi:10.1177/0009922816629760

- Swanepoel, D. W., & Hall, J. W. (2010). A systematic review of telehealth applications in audiology. Telemedicine and eHealth, 16(2), 181–200. doi:10.1089/tmj.2009.0111

- Szarkowski, A., Young, A., Matthews, D., & Meizen-Derr, J. (2020). Pragmatics development in deaf and hard of hearing children: A call to action. Pediatrics, 146(s3), S311–S315. doi:10.15425/peds.2020-0242L

- Umat, C., Mukari, S. Z., Nordin, N., Annamalay, T. A. L., & Othman, B. F. (2018). Mainstream school readiness skills of a group of young cochlear implant users. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 107, 69–74. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.01.031

- Vaismoradi, M., Jones, J., Turunen, H., & Snelgrove, S. (2015). Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 6(5), 100–110. doi:10.5430/jnep.v6n5p100

- Wang, Y., & Engler, K. S. (2011). Early intervention. In P. V. Paul, & G. M. Whitelaw (Eds.), Hearing and deafness: An introduction for health education professsionals (pp. 241–271). Toronto: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

- Watermeyer, J., Kanji, A., & Sarvan, S. (2017). The first step to early intervention following diagnosis: Communication in pediatric hearing aid orientation sessions. American Journal of Audiology, 26(4), 576–582. doi:10.1044/2017_AJA-17-0027

- Watson, P. W., & McKinstry, B. (2009). A systematic review of interventions to improve recall of medical advice in healthcare consultations. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 102, 235–243. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2009.090013

- Weiss, B., & Pollack, A. A. (2017). Barriers to global health development: An international quantitative survey. PLoS ONE, 12(0), e0184846.

- Wertz, F. J., McSpadden, E., Charmaz, K., McMullen, L. M., Anderson, R., & Josselson, R. (2011). Five ways of doing qualitative analysis: Phenomenological psychology, grounded theory, discourse analysis, narrative research and intuitive inquiry. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Wood, N. H. (2023). The impact of loadshedding on dental practice in South Africa. South African Dental Journal, 78(1).

- World Bank. (2021). The World Bank: South Africa. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/country/za

- World Health Organisation. (2010). Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems : a Handbook of Indicators and their measurement strategies. Retrieved from. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258734/9789241564082-eng.pdf

- World Health Organisation. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336034/nCoV-weekly-sitrep11Oct20-eng.pdf

- World Medical Association. (2013). Declaration of Helsinki-Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Retrieved from http://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/#:~:text=Medical%20research%20involving%20human%20subjects%20must%20be%20conducted%20only%20by,or%20other%20health%20care%20professional

- Yerraguntla, K., Ravi, R., & Gore, S. (2018). Knowledge and attitude of pediatric hearing impairment among general physicians and medical interns in coastal Karnataka, India. Indian Journal of Otology, 22(3), 183–187. doi:10.4103/0971-7749.187980

- Yoshinaga-Itano, C. (2014). Principles and guidelines for early intervention after confirmation that a child is deaf or hard of hearing. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 19, 143–175.

- Young, A., & Tattersall, H. (2007). Universal newborn hearing screening and early identification of deafness: Parents’ responses to knowing early and their expectations of child communication development. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 12, 209–220.