ABSTRACT

Written reflective practice (WRP) is a teaching and learning activity utilized in clinical programmes. Identifying depth of WRP aims to provide an overall rating of students’ written reflective abilities. Engaging in reflective activities has been proposed to have a positive relationship with clinical competency. Aims: 1. To examine the impact of time on depth of WRP for SLT students across and within each year group of the SLT clinical programme. 2. To determine whether a relationship exists between depth of WRP and clinical competency of SLT students. Methods: Participants were 77 undergraduate SLT students (first, second or final professional year) in the clinical programme. Participants wrote reflections as part of their clinical education experiences. Depth of WRP was measured utilizing a modification of Plack et al.’s [2005. A method for assessing reflective journal writing. Journal of Allied Health, 34(4), 199–208] coding schema. This was completed at four time points across the academic year for each professional year. Level of clinical competency was assessed using the Competency Assessment in Speech Pathology (COMPASS®) at the end of both semesters. Results: There was a statistically significant association between time and development of depth of WRP for students in their final professional year (β = .66 (.30), z = 2.22, p < .05). There was no association between depth of WRP and level of clinical competency. Conclusion: A one-off judgement of WRP depth may be useful for supporting overall judgements of RP ability and provide observable behaviours for competency assessments. This research contributes to the evidence base examining how WRP is assessed and utilized in clinical programmes.

Introduction

The objective of Speech-language Therapy (SLT) programmes is to develop students into competent clinicians. Competency development is described as both the participation in clinical practice and learning from clinical practice (Walker, Citation1985). Specific to SLT, competency is defined as ‘ … combinations of knowledge, skills and personal qualities that contribute to sets of occupational and professional competencies that combine to create competent professional performance … ’ (Sheepway, Lincoln, & McAllister, Citation2014, p. 190).

Across allied health, nursing and medical clinical education programmes competency is measured in a variety of ways and differs between programme, governing body, licencing board and country of training. In general, the governing bodies or licencing boards have identified the core areas, minimum skills or certification standards required on entry to their specific profession. This level of competency is also termed entry-level practice (Fouad et al., Citation2009; Nursing Council of New Zealand, Citation2022; Occupational Therapy Board of New Zealand, Citation2022; Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand, Citation2018; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2020; Standards of Proficiency for Speech and Language Therapists, Citation2014).

Clinical competency for SLT clinical programmes

Specific to SLT students training programmes in Australia, New Zealand and South East Asia the entry-level practice competencies are derived from seven Competency Based Occupational Standards for Speech Pathologists (CBOS) competencies (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2011). An additional four professional competencies (Reasoning, Communication, Learning and Professionalism) are combined with the CBOS standards and comprise the Competency Assessment in Speech Pathology (COMPASS®). This valid and reliable tool assesses and tracks competency development for SLT students (McAllister, Lincoln, Ferguson, & McAllister, Citation2013a; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2011). The COMPASS® instrument has been utilized in research as the measure of competency in studies examining clinical competency as influenced by placement type and simulation (Hill et al., Citation2021; Sheepway et al., Citation2014).

Additionally, requirements for assessing each area of competency are individualized across SLT clinical programmes and are tailored to meet the requirements of that programme’s university quality assurance process (e.g., Academic Quality Assurance of New Zealand Universities) and accreditors (e.g., New Zealand Speech-language Therapists’ Association Programme Accreditation Committee) One such example, is that the New Zealand Speech-language Therapists’ Association Programme Accreditation Committee requires all programmes to be accredited against The Aotearoa New Zealand Context. This is specific to SLT programmes in New Zealand. However, the exact choice and design of assessment is typically determined by the clinical programme, and considers the needs of their student population and university regulations.

Predicting student clinical competency

Identifying factors that could either predict or contribute to student development of clinical competency is of particular interest to researchers in academic and clinical education programmes. The identification of factors critical to the development of clinical competency would allow educators to streamline the admissions process and/or provide bespoke and tailored support during training that better meets student needs (Boles, Citation2018; Middlemas, Manning, Gazzillo, & Young, Citation2001). Past studies in athletic, dental, SLT, nursing and medical student training programmes examining the ability to predict academic and clinical competency prior to admission to the clinical programmes or prior to workplace practice have yielded varying results (Blackman, Hall, & Darmawan, Citation2007; Boles, Citation2018; Gadbury-Amyot et al., Citation2005; Stacey & Whittaker, Citation2005; Troche & Towson, Citation2018). One key measure used to predict competency is that of grade point average (GPA). GPA alone has thus far been found to be an ineffective predictor of future academic and/or clinical competency (Blackman et al., Citation2007; Boles, Citation2018; Stacey & Whittaker, Citation2005; Troche & Towson, Citation2018). Moving away from GPA, use of a one-off objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) early in medical training did predict future success for clinical competency in clinical programmes and postgraduate training (Wallenstein, Heron, Santen, Shayne, & Ander, Citation2010).

Beyond academic and clinical performance, an individual’s ability to accurately rate their own competence in clinical practice has also been suggested and examined as a measure of competency (Blackman et al., Citation2007; Chambers, Citation1993). Self-assessment as part of student portfolios is commonly used in clinical programmes and has been suggested as a more robust way to assess competency over time rather than a one-off assessment (Gadbury-Amyot et al., Citation2005). Self-assessment is also utilized as one part of the COMPASS® assessment for SLP students (McAllister et al., Citation2013a; McAllister, Lincoln, Ferguson, & McAllister, Citation2013b ).

Reflective practice (RP) is a further learning tool and form of self-assessment that is utilized with students in clinical programmes. Specific to SLT, RP is defined as a ‘ … means by which learners can make sense of and integrate new learning into existing knowledge’ (McAllister & Lincoln, Citation2004, p. 125). RP activities have also been used as a piece of assessment, to contribute to either clinical competency or academic grades, or a combination of both in clinical education programmes (Boud, Citation1995; Levett-Jones, Citation2005; Musolino, Citation2006). The utilization of RP can be found as written reflections (WR) included in ePortfolio assignments (Gadbury-Amyot et al., Citation2005; Walton, Gardner, & Aleksejuniene, Citation2016); reflective discussions to support practical assessments (VIVA VOCE) (Orrock, Grace, Vaughan, & Coutts, Citation2014), stand-alone WRP assignments (Cook et al., Citation2019), and evaluations of clinical competency (e.g., COMPASS®, (McAllister et al., Citation2013a, Citation2013b)).

Reflective practice and development of competency

RP skill has been long described as a stepping stone towards clinical competency, yet empirical evidence supporting this relationship is limited and outcomes of studies have found mixed results (Caty, Kinsella, & Doyle, Citation2015; Schön, Citation1983; Schön, Citation1987). To date, examination of clinical competency and RP has largely been presented via one-off assessment tasks, or student perception of RP and competency development (Chabeli, Citation2010; Domac, Anderson, O’Reilly, & Smith, Citation2015; Lim & Low, Citation2008b, Citation2008a; Mamede, Schmidt, & Penaforte, Citation2008; Tsingos-Lucas, Bosnic-Anticevich, Schneider, & Smith, Citation2017). Two studies examining the perceptions of nursing student have suggested that a positive relationship exists between RP and clinical competence level (Eng & Pai, Citation2015; Pai, Citation2016). In comparison, a study examining clinical competency of occupational therapy students revealed a positive relationship between the student self-assessment scales for reflective practice and occupational therapy competence, but not between student self-assessment of reflective practice and the educator rated clinical performance level (Iliff et al., Citation2021).

WRP is a RP activity that is regularly utilized in clinical programmes, including SLT where development of RP skills over time as clinical experience increases has been reported (Cook, Messick, & McAuliffe, Citation2022; Dunne, Nisbet, Penman, & McAllister, Citation2019). For students in clinical programmes, educators suggest that WRP skills are important for clinical competency development or contribute to clinical competency. However, this has not been tested for students despite being embedded into clinical programmes (Aronson, Niehaus, Hill-Sakurai, Lai, & O’Sullivan, Citation2012; Caty et al., Citation2015; Chabeli, Citation2010; Cook et al., Citation2019; Cook et al., Citation2022; Halton, Murphy, & Dempsey, Citation2007; Ng, Bartlett, & Lucy, Citation2012; Plack, Driscoll, Blissett, McKenna, & Plack, Citation2005). Furthermore, studies examining changes in SLT student WRP skills over time or with increased clinical experience have indicated a positive relationship exists for depth of WRP over a six-week period (Cook et al., Citation2019). Depth of WRP is an overall judgement of WRP skill, whereby SLT students are judged as falling into one of five categories (‘Non-reflector’, ‘Emerging-reflector’, ‘Reflector’, ‘Emerging-critical-reflector’, or ‘Critical reflector’. See for definitions) (Cook et al., Citation2019; Plack et al., Citation2005). Alternatively, three trajectories of WRP skill development were identified over a period of ten weeks for SLT students: ‘steady growth’, ‘no clear change’ and ‘gradual decline’ (Dunne et al., Citation2019). However, SLT student WRP skills have not been examined in relation to clinical competency.

Table 1. Coding schema for depth of written reflective practice, modified from Plack et al. (Citation2005) (first modification for Cook et al., Citation2019, second modification by Cook et al., Citation2022).

In summary, the ability to predict clinical competency has been largely investigated through one-off snap-shots of skills or varied types of skills such as GPA, self-rating scales, educator rating scales, portfolios, practical assessments and clinical placements in medical and allied health programmes with varying outcomes (Blackman et al., Citation2007; Boles, Citation2018; Chambers, Citation1993; Gadbury-Amyot et al., Citation2005; Iliff et al., Citation2021; Middlemas et al., Citation2001; Stacey & Whittaker, Citation2005; Troche & Towson, Citation2018; Wallenstein et al., Citation2010). There remains an assumption that clinical competency development is aided or enhanced by RP activities such as WRP, however, further studies are needed to provide empirical evidence. This includes examining the relationship between SLT student clinical competency and development of RP abilities across a clinical programme (Caty et al., Citation2015; Schön, Citation1983; Schön, Citation1987). To our knowledge no such study has explored an association between WRP depth and clinical competency across a speech-language therapy (SLT) clinical programme. Investigation of such an association is a precursor to examination into an ability to predict clinical competency through utilization of WRP activities. As such, this study aims to:

Examine the impact of time on depth of WRP for SLT students across and within each year group (first, second and final) of the SLT the clinical programme.

Determine whether a relationship exists between depth of WRP and level of clinical competency of SLT students.

Methods

This study received ethical approval from [University Name] Human Ethics Committee, [university location]. All participants provided written consent to participate.

Study context

This cross-sectional and repeated measures design study was conducted as part of the speech-language therapy (SLT) clinical programme at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand (NZ). The students included in this study were all completing a 4-year undergraduate honours degree in SLT. The first year of study does not include clinical education, and years two through four are professionally orientated (renamed first, second and final professional year) and include a focus on clinical placement experiences. Students are eligible to practice as a Speech-language Therapist at the conclusion of the final professional year.

As part of the programme, and reported in Cook et al. (Citation2022), students engaged in a variety of RP activities. Clinical educators (CE) utilized dialogic teaching, class discussions, metacognitive discussions, informal discussions with clinical educators (individual or group) written reflections (informal and assessed) and verbal reflective practice groups (discussion groups with student peers and a clinical educator facilitating professional topics). See Tillard, Cook, Gerhard, Keast, and McAuliffe (Citation2018) for a detailed report on the structure of verbal reflective practice groups for SLT students. Appendix 1 describes the RP clinical education programme followed by the SLT clinical education programme (Cook et al., Citation2022). Inclusion of weekly written reflections (WR) was usual practice for all clinical courses and part of clinical education learning outcomes (see Appendix 2 for Guiding questions).

This study examined usual practice, therefore for each professional year, students completed two semesters of academic study. This included 12 weeks per semester of clinical experiences in a range of clinical environments and populations including preschool, school-aged children and adults under the guidance of a Clinical Educator (CE). At two points during clinical programme, SLT students engaged in clinical placements described as ‘block placements’. A block placement is a full-time placement (i.e., 40 h per week) with no academic class requirements (McAllister et al., Citation2013b).

Participants

The study included the same 77 undergraduate students enrolled in clinical courses as part of the Speech-Language Pathology honours programme, and reported in Cook et al. (Citation2022). The average age of the participants was 21.5 years (SD = 3.95) with 75 females and 2 males participating in the study. See for participant details by professional year. The study excluded any students who chose to withdraw from a clinical course during the semester.

Table 2. Demographic details of student participants by professional year.

Instruments

Coding of participants’ WR was initially undertaken to identify breadth of WR present in each participant’s WR using the procedure defined by Plack et al. (Citation2005), modified by Cook et al. (Citation2019) and reported in Cook et al. (Citation2022) (see Appendix 3 for breadth coding framework). The Cook et al. (Citation2022) study utilized and reported on the data gained from the breadth of reflection component. The current study utilized data generated from the depth of reflection component as the outcome measure for this study. Depth of reflection is described as an overall level of reflective practice skill (Hill, Davidson, Theodoros, Citation2012 ; Plack et al., Citation2005). Depth of reflection has also been described as an overall measure of reflective competency (Plack et al., Citation2005). The five depth categories (‘Non-reflector’, ‘Emerging-reflector’, ‘Reflector’, ‘Emerging-critical-reflector’, or ‘Critical reflector’. See for definitions) allowed for comparison of category of reflection to level of clinical competency gained as part of the COMPASS® assessment. For identification of depth of reflection, in keeping with the Cook et al. (Citation2019) methodology, the authors applied a rule-based system where by inclusion of specific breadth of reflection codes informed the condition for depth of reflection (). For example, a WR with the breath codes ‘return’ and or ‘attend’ only, would fall into the ‘Non-reflector’ depth category. The depth categories were developed and based on the Plack et al. (Citation2005) schema and further defined from readings from Schön (Citation1987), Mezirow (Citation1991), and Boud et al. (Citation1985). As per the 2019 study, modifications to the ‘depth’ categories proposed by Plack et al. (Citation2005) were utilized whereby ‘emerging reflector’ and ‘emerging critical reflector’ were introduced following a review of the reflective practice literature in an attempt to make the instrument more sensitive to subtle changes in depth of student reflection. The description of depth categories and allocation of breadth codes to depth categories are found in .

Competency Assessment in Speech Pathology (COMPASS®) is a valid and reliable online outcome measure of SLT student performance (McAllister et al., Citation2013a). COMPASS® is used in all SLT programmes in Australia, New Zealand and South East Asia as one assessment of clinical competency. For the purpose of this assessment tool, the term competence is defined as an ‘observable competent action’ (McAllister et al., Citation2013a). As per recommendations by McAllister et al. (Citation2013a), students are required to complete their own ratings for all 11 competencies as a self-evaluation practice and to further inform the CE’s judgement. The student and the CE then meet to discuss the student’s competency and complete the visual analogue scale (VAS) to rate student performance. The 11 competencies are then automatically combined via a scoring system to provide a judgement of overall competency in SLT practice (McAllister et al., Citation2013a). The automatic scoring system converts the VAS into one of seven categories representing increases in clinical performance, then to interval-level data and finally parametric statistics are completed (McAllister et al., Citation2013b). The output includes a ‘raw score’ (range 11–77, the sum of the 11 competencies), an ‘overall competency score’ (range 144–835.25), an interval measure expressed as a scaled score and an overall ‘zone of competency’ (ZOC) (range 1–7, an interval measure indicating one of seven developmental ZOC determined by the student’s competency score). For this study, and in keeping with the recommendations from the COMPASS® technical manual, ZOC represents each student’s clinical competency score. ZOC has been reported in past studies examining SLT clinical competency (e.g., Hill et al., Citation2021; Sheepway et al., Citation2014). For further reading on the development, validation and statistical properties of COMPASS® see McAllister et al. (Citation2013b).

Procedure

This study employed the same procedure for the WR data published by Cook et al. (Citation2022). In brief, as part of usual practice students wrote and submitted WR weekly. Students were encouraged to submit their WR within 24 h of the clinical experience they were reflecting on. Guiding questions were utilized to support engagement in the WR process (see Appendix 2 for guiding questions) (Cook et al., Citation2022). Students received at least two pieces of written feedback per WR from their CE. CE were encouraged to provide feedback based on the process of reflection the student had undertaken and could utilize the coding framework published in Cook et al. (Citation2022) to assist (see Appendix 3 for coding framework). Beyond the encouragement provided to CEs, all CEs had full ownership of amount, frequency and style of formative feedback they chose to provide to student SLT. For this study and Cook et al. (Citation2022) the WR selected for analysis were taken from the start and end of each clinical course for each semester. This totalled four WR for each student across the professional year (reported as T1, T2 (start and end of semester one), T3 and T4 (start and end of semester two)).

With respect to the COMPASS® instrument, in the final week of semester one and two, as part of usual practice, the end placement COMPASS® Competency Assessment in Speech Pathology was completed with the participant and their CE. This instrument was administered via a secure website. COMPASS® data were inspected to check for variation between individual student scores (no variation found) and that ZOC data were available for extraction (in keeping with COMPASS® no ZOC data would be available for any students where more than three units were not scored). This did not occur for any students. Following this the COMPASS® ZOC data for each participant was extracted from ACCESS 2013 software. COMPASS® end placement clinical competency data were available for T2 and T4 (semester one and two) for second and final professional year students and T4 (semester 2) for first professional year students. As part of usual practice, the first clinical course, for the first professional year group, does not utilize the COMPASS® tool as students are deemed ‘pre novice’.

Data analysis

Each WR was deidentified, given a randomly generated number and then coded for breadth of reflection by trained research assistants, (see Cook et al. (Citation2022) study for full description of training, analysis and reliability). The research assistants had no relationship to the students or CEs. The depth category for each WR was then automatically generated in excel for each participant at each timepoint (T1-4) ( illustrates how breadth elements contributed to the judgement of depth). A total of 273 of a possible 308 WR were submitted and given a depth category (from 77 participants, across the three-year groups, at four time points—referred to as T1, T2, T3 and T4). indicates the number of participants by year group who submitted a WR for each time point. COMPASS® end placement clinical competency data extracted for this study was the ZOC (1–7 interval level zones). Any fractions of zones were converted to whole numbers for assessment purposes (Hill et al., Citation2021). WR depth category was matched to COMPASS® ZOC scores for each participant and at each timepoint. For each timepoint, any data that could not be matched was excluded from the analysis. Average scores for the depth categories were reported using descriptive statistics. Visual inspection in the form of both table and figure was completed initially to compare WR depth category for time 2 and 4 to COMPASS® ZOC score.

Table 3. Number of participants who submitted a written reflection for each time point across the academic year (% of written reflections compared to the expected number).

Statistical analysis

To examine the effect of time both within professional year groups (T1–T4) and across professional year groups (First, Second and Final) on WR depth, mixed effects modelling was utilized (Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, Citation2015). This was used in keeping with the Cook et al. (Citation2022) analysis. Analysis was undertaken in R (R Core Team, Citation2015), using the add-on packages lme4 (Bates et al., Citation2015) and ordinal (Christensen, Citation2015). A mixed-effects cumulative link logistic regression model for ordered categories was utilized. The aim was to predict the probability of participants to fall into ordered depth of reflection categories both across and within year groups (with alpha at 0.5). Slope parameters were included to model the change in probability over time for being allocated into a specific reflection depths category. Participant-specific changes in slopes were included in the model as normally distributed random effects.

To determine if a relationship (positive or negative) existed between WR depth and ZOC for clinical competency a second mixed-effects cumulative link logistic regression model for ordered categories was utilized. This examined depth of reflection categories both across and within year groups compared to ZOC score for T2 (second and final professional year group) and T4 (all year groups).

Results

A total of 46 participants (60% of possible participants who consented to participate in the study) submitted a WR at each of the four time points (T1, T2, T3, T4). provides details of participants, organized by professional year and time point and indicates participant WR submissions. All professional year groups demonstrated participant attrition over time.

The effect of time on depth of written reflective practice across and within SLT year groups

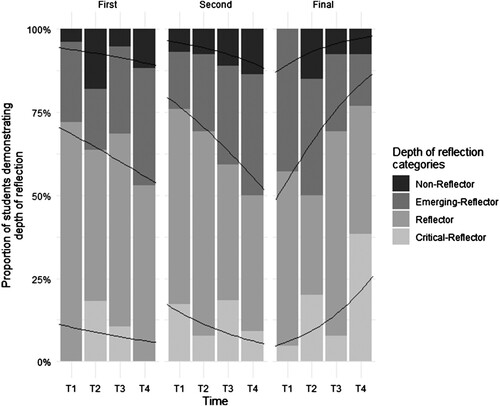

illustrates the proportion of SLT students categorized as Non-reflector, Emerging-reflector, Reflector, Emerging-critical-reflector or Critical reflector and the change within these depth categories across time. No participants were categorized as Emerging-critical-reflector. At any time point, the majority of participants were categorized as Reflectors, with Emerging-reflector as the next largest RP depth category. At the conclusion of the assessment period (T4) the majority of participants in the final professional year group had progressed into the higher categories of Reflector and Critical reflector. To examine the effect of time and clinical experience on depth of reflection category a logistic regression model for ordered categories was run with the fixed effects of time (T1–T4), and professional year (first, second and final) in comparison to the threshold coefficients (Model 1 ). The threshold coefficients are the estimated thresholds for first professional year participant T1 depth categories. Model 1 indicates there was a statistically significant association between increasing time and the probability to develop depth of reflection for final professional year students only (β = .66 (.30), z = 2.22, p < .05).

Figure 1. Proportion of participants by professional year demonstrating a category for depth of reflection at that particular time point (time 1–4), with the predicted thresholds between categories (black lines). See for a definition of each depth category.

Table 4. Coefficients of the mixed effects model for depth of written reflection with the fixed effects of time and professional year in comparison to the first professional year (Threshold coefficients).

Determining a relationship between WRP and clinical competency

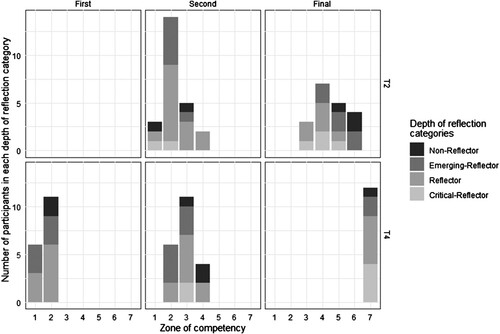

To determine a relationship between WRP and clinical competency, depth of reflection data from SLT student participants in time 2 and time 4 were extracted and compared to the COMPASS® clinical competency data (ZOC) at the same time points. presents SLT student participants by professional year group for whom both depth of reflection category and ZOC was available for time 2 (43 students) and 4 (50 students). This excluded ZOC data for time 2 for first professional year students as no COMPASS® data were collected for this group as part of usual practice. Participant attrition is seen over time. It can be seen that over time as a group, students in the second professional and final year groups demonstrate increasing ZOC median.

Table 5. Number (percentage) of participants in each zone of competency (ZOC) by professional year group and timepoint (time two (T2) and time four (T4)).

illustrates all SLT students by professional year group, their category for depth for of reflection and their ZOC as taken from the COMPASS® instrument (time 2 and time 4). To examine a relationship between depth category and ZOC visual inspection of was first completed and indicated that there was no association between WRP and ZOC as time and clinical experience increased. Students judged as having higher depth of WRP categories (e.g., Emerging-critical-reflector or Critical reflector) did not have a higher ZOC. A second logistic regression model for ordered categories was run with the fixed effects of time (Model 2 ). Model 2 confirmed no significant effect can be found between change in depth category and ZOC as time and clinical experience (across or within professional year group) increased. An interpretation of this finding is that both year and ZOC share the effect. instead illustrates that professional year and ZOC could be intertwined, in that, it was not clear if SLT student year of experience predicted ZOC or ZOC predicts SLT professional year.

Discussion

The purposes of this study were to: (1) examine the impact of time on depth of WRP for SLT students across and within each year group (first, second and final) of the SLT the clinical programme; and (2). Determine whether a relationship exists between depth of WRP and level of clinical competency of SLT students. The results indicated that the majority of SLT students fell into the depth category of Reflector. Category of depth of reflection increased as clinical experience increased for final professional year SLT students. First and second professional year SLT students were variable in their demonstration of depth of WRP across and within the clinical programme. No relationship was indicated for depth of WRP and clinical competency across and within the clinical programme. The findings are discussed with implications for clinical education, limitations and future research.

Depth of written reflective practice as clinical experience increases

This study found that at any one point in time the majority of SLT students in the study were categorized as Reflectors for depth of WRP. This finding is consistent with past studies of SLT and Physical therapy students’ depth of WRP category (Cook et al., Citation2019; Hill et al., Citation2012; Plack et al., Citation2005). While this finding highlights similarities across SLT student groups, it may in fact be related to similar guiding questions being employed for SLT students regardless of professional year group. It may be that, the tailoring of guiding questions for WRP to specific professional year groups rather than placement type yields a different outcome. Better tailoring of guiding questions, may be useful to offer additional opportunities for observable behaviours of ‘critical reflectors’. Therefore, examination of guiding questions employed for WRP warrants systematic examination in the future.

Over time, final-year SLT students significantly enhanced their depth of WRP category. In comparison, the two professional year groups with less clinical experience (first and second) did not. This finding is in contrast to earlier SLT WRP studies and is discussed in detail below (Cook et al., Citation2019; Hill et al., Citation2012). The finding for final year students however, produced similar results to Plack et al.’s (Citation2005) depth of WRP results for a one-off examination of final year physical therapy students. The current study then extends Plack et al.’s (Citation2005) findings by identifying significant positive change over time for final professional year SLT students’ depth of WRP. One reason for this finding may relate to the combination of RP activities, feedback and teaching that was part of usual clinical practice for the SLT students in the current study (see Appendix 2). It may be that students in the final professional year were better able to use their extra knowledge about RP, as well as the feedback provided by CEs about their RP process, as a self-directed learning tool (Dunne et al., Citation2019). Extending on this, as part of their clinical placement experience, students in the final professional year may have been exposed to and able to reflect on more complex clinical situations compared to first and second professional year students. Complex clinical situations have also been described as a catalyst for RP (Mann, Gordon, & MacLeod, Citation2009). Finally, this significant finding may highlight final professional year students’ progression towards workplace readiness and demonstration of life-long learning practices, where they continue to engage in learning and personal development activities such as RP, beyond formal education settings.

First and second professional year SLT students were more variable in their depth category over time. This finding is in keeping with descriptions of variability for reports of clinical competency and another mixed methods investigation into WRP for SLT students, for the second professional year SLT students (Dunne et al., Citation2019; McAllister et al., Citation2013b). However, it was unexpected for first professional year students, who one might expect to begin at the non-reflector category and progress through emerging reflector categories . One reason for these unexpected findings for both groups of students again likely relates to the focus on usual practice for this study. Usual practice meant the clinical placements were varied. Placements varied by population (e.g., adult, child or mixed), environment (e.g., school, hospital or private practice settings), and time (e.g., part-time placement and block placement) within and across professional year groups. This finding may indicate that while in the earlier stages of the clinical programme, consistency of clinical placement, may allow students to better demonstrate higher depth of RP as seen in earlier studies of SLT students WRP abilities in the first and second professional year that used a consistent clinical placement experience (Cook et al., Citation2019; Hill et al., Citation2012). Consistency of clinical placement may allow students to: (1) build on repeated experiences, (2) receive formative feedback from the same CE and (3) discuss the impact of the repeated experiences on their learning in WRP in more depth over time. Studies describing simulation activities and strategies for supporting culturally and linguistically diverse SLT students, have identified similar benefits as a result of repeated practice or consistency of clinical placement. The benefits included enhanced clinical skill and confidence for SLT students (Attrill, Lincoln, & McAllister, Citation2015; Becker, Rose, Berg, Park, & Shatzer, Citation2006; Penman, Hill, Hewat, & Scarinci, Citation2021). A second reason for these findings may be that the variability indicates each student’s unique background, past life experiences and past experiences with WRP. This would be a useful avenue for future research.

The relationship between WRP and clinical competency

No association was detected between depth of WRP and clinical competency. Therefore, there was no ability to predict clinical competency based on depth of WRP. Instead, clinical competency appeared to be associated to professional year group. The findings contrast with prior medical and allied health studies that suggested positive relationships with RP and competency, and a positive impact on future clinical practice (Aronson et al., Citation2012; Caty et al., Citation2015; Chabeli, Citation2010; Cook et al., Citation2019; Halton et al., Citation2007; Ng et al., Citation2012; Plack et al., Citation2005). This finding may again be due to the RP guiding questions enlisted to guide student WRP. Use of these guiding questions aimed to promote reflective questioning, however, the questions may in fact be restricting some students or offer limited opportunities to demonstrate higher-level reflective skills and therefore any relationship between WRP and clinical competency (Tillard et al., Citation2018). Additionally, the finding of clinical competency appearing to be associated to professional year group may be due to CE being aware of the general guide listed for both SLT students and CE in each course outline that stated student competency by the end of the course e.g., ‘students will be approaching intermediate level’.

Given no relationship was found between WRP and clinical competency, the results of the current study, further reinforce that no one assessment tool (such as an overall measure of WRP skill) can be used to predict future clinical competency outcomes. This finding now adds WRP to the body of literature in clinical education where possible relationships between clinical competency, GPA and self-assessment had been examined in order to attempt to predict future clinical competency, or streamline admissions to clinical programmes (Blackman et al., Citation2007; Boles, Citation2018; Chambers, Citation1993; Gadbury-Amyot et al., Citation2005; Hardy et al., Citation2021; Iliff et al., Citation2021; Middlemas et al., Citation2001; Stacey & Whittaker, Citation2005; Troche & Towson, Citation2018; Wallenstein et al., Citation2010).

Implication for clinical education

The findings of this study serve to further inform the use of WRP as part of a clinical education programme of learning for SLT students. Judgements of either depth or breadth of reflection (as reported in Cook et al., Citation2022; Hill et al., Citation2012; Plack et al. Citation2005) continue to keep the focus of the judgement on the process undertaken for RP rather than the content covered in reflection. This practice aims to reduce student report of feeling unsafe and students’ writing what they perceive educators want them to write to gain a high grade (Bourner, Citation2003; Cook et al., Citation2019; Dunne et al., Citation2019; Plack et al., Citation2005).

While the results of this study suggest that the depth of WRP classification system cannot be used to predict student clinical competency as measured by COMPASS®, WRP could instead be used as an example of observable behaviour to inform competency ratings such as COMPASS® (Boud, Citation1995; Levett-Jones, Citation2005; Musolino, Citation2006). A core requirement of COMPASS® is to only rate observable behaviours, yet, RP is sometimes described as difficult to visualize (McAllister, Citation2005; McAllister et al., Citation2013a).

Limitations and future research

A number of limitations and opportunities for future research avenues are apparent as a result of this study. Firstly, the reorganization of depth categories utilizing a rule-based system implemented by Cook et al. (Citation2019) requires further examination. The depth judgement utilized here requires assessment of breadth elements only, rather than allowing raters to make their own subjective depth judgement, as was originally intended by Plack et al. (Citation2005). Examination of agreement between the rule-based system and inter-rater judgement is a useful next step, if educators want to use the depth categories only, for one-off assessments of RP. Additionally, in this study no students were found to be ‘emerging-critical-reflectors’, a category also introduced by Cook et al. (Citation2019) to make the depth instrument more sensitive to SLP students developing RP skills and to map to an academic system of grading (Kember, Mckay, Sinclair, & Kam Yuet Wong, Citation2008). If the goal really is to credit students who are ‘emerging’ in demonstrative of RP abilities then re-examination of the description and criteria of what makes an Emerging-critical-reflector is recommended. Secondly, attrition is seen over time in all year groups in the WRP component (100% to 66%), and when matching participants to their COMPASS® competency scores for both time points (50% of possible participants). This was not unexpected, as attrition in repeated measures designs are expected (Pan & Zhan, Citation2020). However, this may be a source of bias in over interpreting the results (Dumville, Torgerson, & Hewitt, Citation2006). Further studies examining RP and clinical competency over time, could follow a longitudinal approach to focus on examining individual participant characteristics in more detail at each time point in data collection (Dumville et al., Citation2006). Additionally, future research could examine what makes a question reflective? What questions are better posed to final-year students? Or, what questions are useful for all students to address? This could offer educators and students a list of questions to choose from for both WR and reflective discussions, as well as different questions based on SLT student clinical experience.

Conclusion

This study found a positive association with time for demonstration of depth of WRP skills for final year SLT students. First and second professional year students were variable in their demonstration of depth of WRP across time within an academic year. No relationship was seen between depth of WRP and clinical competency across the degree programme. Examination of student depth of WRP maybe useful as a one-off judgement of reflective skill to continue to place the focus of grading on the process undertaken rather than the content of WRP activities. Additionally, judgements of depth of WRP may be useful as an analysis that can contribute to judgements made about student RP abilities as part of the COMPASS® assessment tool and other clinical competency tools.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aronson, L., Niehaus, B., Hill-Sakurai, L., Lai, C., & O’Sullivan, P. S. (2012). A comparison of two methods of teaching reflective ability in Year 3 medical students. Medical Education, 46(8), 807–814. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04299.x

- Attrill, S., Lincoln, M., & McAllister, S. (2015). International students in speech-language pathology clinical education placements: Perceptions of experience and competency development. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(3), 314–324. doi:10.3109/17549507.2015.1016109

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. M., & Walker, S. C. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), doi:10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Becker, K. L., Rose, L. E., Berg, J. B., Park, H., & Shatzer, J. H. (2006). The teaching effectiveness of standardized patients. Journal of Nursing Education, 45(4), 103–111. doi:10.3928/01484834-20060401-03

- Blackman, I., Hall, M., & Darmawan, G. N. (2007). Undergraduate nurse variables that predict academic achievement and clinical competence in nursing. International Education Journal, 8(2), 222–236.

- Boles, L. (2018). Predicting graduate school success in a speech-language pathology program. Teaching and Learning in Communication Sciences & Disorders, 2(2), Article 1.

- Boud, D. (1995). Enhancing learning through self assessment. London/Philadelphia: Kogan Page.

- Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Reflection: Turning experience into learning. In D. Boud, R. Keogh, & D. Walker (Eds.), Reflection: Turning experience into learning. doi:10.4324/9781315059051

- Bourner, T. (2003). Assessing reflective learning. Education + Training, 45(5), 267–272. doi:10.1108/00400910310484321

- Caty, M-È, Kinsella, E. A., & Doyle, P. C. (2015). Reflective practice in speech-language pathology: A scoping review. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(4), 411–420. doi:10.3109/17549507.2014.979870

- Chabeli, M. (2010). Concept-mapping as a teaching method to facilitate critical thinking in nursing education: A review of the literature. Health SA Gesondheid, 15(1), 7. doi:10.4102/hsag.v15i1.432

- Chambers, D. W. (1993). Toward a competency-based curriculum. Journal of Dental Education, 57(11), 790.

- Christensen, R. H. B. (2015). Ordinal –Regression models for ordinal data. R package version 2015.1-21. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ordinal/index.html

- Cook, K., Tillard, G., Wyles, C., Gerhard, D., Ormond, T., & McAuliffe, M. (2019). Assessing and developing the written reflective practice skills of speech-language pathology students. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(1), 46–55. doi:10.1080/17549507.2017.1374463

- Cook, K. J., Messick, C., & McAuliffe, M. J. (2022). Written reflective practice abilities of SLT students across the degree programme. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12815

- Crisp, B. R., Lister, P. G., & Dutton, K. (2005). Integrated assessment. Evaluation of an innovative method of assessment: Critical incident analysis. https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/38310/1/sieswe_nam_evaluation_critical_incident_analysis_2005_02.pdf

- Domac, S., Anderson, L., O’Reilly, M., & Smith, R. (2015). Assessing interprofessional competence using a prospective reflective portfolio. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29(3), 179–187. doi:10.3109/13561820.2014.983593

- Dumville, J. C., Torgerson, D. J., & Hewitt, C. E. (2006). Reporting attrition in randomised controlled trials. BMJ, 332(7547), 969–971. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7547.969

- Dunne, M., Nisbet, G., Penman, M., & McAllister, L. (2019). Facilitating the development and maintenance of reflection in speech pathology students. Health Education in Practice: Journal of Research for Professional Learning, 2(2). doi:10.33966/hepj.2.2.13579

- Eng, C.-J., & Pai, H.-C. (2015). Determinants of nursing competence of nursing students in Taiwan: The role of self-reflection and insight. Nurse Education Today, 35(3), 450–455. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2014.11.021

- Fouad, N. A., Grus, C. L., Hatcher, R. L., Kaslow, N. J., Hutchings, P. S., Madson, M. B., … Crossman, R. E. (2009). Competency benchmarks: A model for understanding and measuring competence in professional psychology across training levels. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 3(4S), S5–S26. doi:10.1037/a0015832

- Gadbury-Amyot, C. C., Bray, K. K., Branson, B. S., Holt, L., Keselyak, N., Mitchell, T. V., & Williams, K. B. (2005). Predictive validity of dental hygiene competency assessment measures on one-shot clinical licensure examinations. Journal of Dental Education, 69(3), 363–370. doi:10.1002/j.0022-0337.2005.69.3.tb03923.x

- Halton, C., Murphy, M., & Dempsey, M. (2007). Reflective learning in social work education: Researching student experiences. Reflective Practice, 8(4), 511–523.

- Hardy, J., Lewis, A., Walters, J., Hill, A. E., Arnott, S., Penman, A., … Hewat, S. (2021). Reflections on clinical education by students and new graduates: What can we learn? Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology, 23(3), 146–150.

- Hill, A. E., Davidson, B. J., & Theodoros, D. G. (2012). Reflections on clinical learning in novice speech-language therapy students. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 47(4), 413–426. doi:10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00154.x

- Hill, A. E., Ward, E., Heard, R., McAllister, S., McCabe, P., Penman, A., … Walters, J. (2021). Simulation can replace part of speech-language pathology placement time: A randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 23(1), 92–102. doi:10.1080/17549507.2020.1722238

- Iliff, S., Tool, G., Bowyer, P., Parham, L., Fletcher, T., & Freysteinson, W. (2021). Self-reflection and its relationship to occupational competence and clinical performance in Level II fieldwork. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice, 19(1), Article 8. doi:10.46743/1540-580x/2021.1988

- Kember, D., Mckay, J., Sinclair, K., Kam Yuet Wong, F. (2008). A four-category scheme for coding and assessing the level of reflection in written work. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(4), 369–379. doi:10.1080/02602930701293355

- Levett-Jones, T. L. (2005). Self-directed learning: Implications and limitations for undergraduate nursing education. Nurse Education Today, 25(5), 363–368. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2005.03.003

- Lim, P. H., & Low, C. (2008a). Reflective practice from the perspectives of the bachelor of nursing students: A focus interview. Singapore Nursing Journal, 35(4), 8.

- Lim, P. H., & Low, C. (2008b). Reflective practice from the perspectives of the bachelor of nursing students in International Medical University (IMU). Singapore Nursing Journal, 35(3), 5.

- Mamede, S., Schmidt, H. G., & Penaforte, J. C. (2008). Effects of reflective practice on the accuracy of medical diagnoses. Medical Education, 42(5), 468–475. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03030.x

- Mann, K., Gordon, J., & MacLeod, A. (2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14(4), 595–621. doi:10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2

- McAllister, L., & Lincoln, M. (2004). Clinical education in speech-language pathology. London: Whurr.

- McAllister, S. (2005). Competency based assessment of speech pathology students’ performance in the workplace (Published thesis). The University of Sydney (Issue May). University of Sydney.

- McAllister, S., Lincoln, M., Ferguson, A., & McAllister, L. (2013a). COMPASS® competency assessment in speech pathology assessment resource manual (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Speech Pathology Association of Australia.

- McAllister, S., Lincoln, M., Ferguson, A., & McAllister, L. (2013b). COMPASS®:competency assessment in speech pathology technical manual (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Speech Pathology Association of Australia.

- Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Middlemas, D. A., Manning, J. M., Gazzillo, L. M., & Young, J. (2001). Predicting performance on the National Athletic Trainers’ Association Board of Certification Examination from grade point average and number of clinical hours. Journal of Athletic Training, 36(2), 136–140. https://go.exlibris.link/0MCC0BTj

- Musolino, G. M. (2006). Fostering reflective practice: Self-assessment abilities of physical therapy students and entry-level graduates. Journal of Allied Health, 35(1), 30–42. https://go.exlibris.link/wNksZ8WH

- Ng, S. L., Bartlett, D., & Lucy, S. D. (2012). The education and socialization of audiology students and novices. Seminars in Hearing, 33(2), 177–195. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1311677

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2022). Competencies for registered nurses. https://www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Public/Nursing/Standards_and_guidelines/NCNZ/nursing-section/Standards_and_guidelines_for_nurses.aspx

- Occupational Therapy Board of New Zealand. (2022). Competencies for registration and continuing practice for occupational therapists. https://otboard.org.nz/document/6151/7569 OTBNZ – Competencies for practice FINAL.pdf

- Orrock, P., Grace, S., Vaughan, B., & Coutts, R. (2014). Developing a viva exam to assess clinical reasoning in pre-registration osteopathy students. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 193. BioMed Central Ltd. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-193

- Pai, H.-C. (2016). An integrated model for the effects of self-reflection and clinical experiential learning on clinical nursing performance in nursing students: A longitudinal study. Nurse Education Today, 45, 156–162. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2016.07.011

- Pan, Y., & Zhan, P. (2020). The impact of sample attrition on longitudinal learning diagnosis: A prolog. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1051–1051. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01051

- Penman, A., Hill, A. E., Hewat, S., & Scarinci, N. (2021). Does a simulation-based learning programme assist with the development of speech–language pathology students’ clinical skills in stuttering management? International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 56(6), 1334–1346. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12670

- Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand. (2018). Physiotherapy Standards framework – 2018. https://pnz.org.nz/physiotherapy.org.nz/Attachment?Action=Download&Attachment_id=1154

- Plack, M. M., Driscoll, M., Blissett, S., McKenna, R., & Plack, T. (2005). A method for assessing reflective journal writing. Journal of Allied Health, 34(4), 199–208. doi:10.1097/00001416-200607000-00014

- Schön, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

- Sheepway, L., Lincoln, M., & McAllister, S. (2014). Impact of placement type on the development of clinical competency in speech–language pathology students. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 49(2), 189–203. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12059

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2011). Competency-based occupational standards for speech pathologists: Entry level. (Updated 2017).

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2020). Professional standards for speech pathologists in Australia. 11. https://speechpathologyaustralia.cld.bz/Speech-Pathology-Australia-Professional-Standards-2020/2/

- Stacey, D. G., & Whittaker, J. M. (2005). Predicting academic performance and clinical competency for international dental students: Seeking the most efficient and effective measures. Journal of Dental Education, 69(2), 270–280. doi:10.1002/j.0022-0337.2005.69.2.tb03913.x

- Standards of Proficiency for Speech and language therapists, Health Professions Council Documents 16. (2014). https://www.hcpc-uk.org/standards/standards-of-proficiency/speech-and-language-therapists/

- Team, R. C. (2015). A language and environment for statistical computing. from http://www.R-project.org/. In R Foundation for Statistical Computing (Vol. 10, Issue 1)

- Tillard, G. D., Cook, K., Gerhard, D., Keast, L., & Mcauliffe, M. (2018). Speech-language pathology student participation in verbal reflective practice groups: Perceptions of development, value, and group condition differences. Teaching and Learning in Communication Sciences and Disorders, 2(2). doi:10.30707/tlcsd2.2tillard

- Troche, J., & Towson, J. (2018). Evaluating a metric to predict the academic and clinical success of master’s students in speech-language pathology. Teaching and Learning in Communication Sciences & Disorders, 2(2), Article 7.

- Tsingos-Lucas, C., Bosnic-Anticevich, S., Schneider, C. R., & Smith, L. (2017). Using reflective writing as a predictor of academic success in different assessment formats. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 81(1), 1–8. doi:10.5688/ajpe8118

- Walker, D. (1985). Writing and reflecting. In D. Boud, R. Keogh, & D. Walker (Eds.), Reflection: Turning experience into learning (pp. 52–68). London/New York: Kogan Page.

- Wallenstein, J., Heron, S., Santen, S., Shayne, P., & Ander, D. (2010). A core competency-based objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) can predict future resident performance. Academic Emergency Medicine, 17, S67–S71. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00894.x

- Walton, J. N., Gardner, K., & Aleksejuniene, J. (2016). Student ePortfolios to develop reflective skills and demonstrate competency development: Evaluation of a curriculum pilot project. European Journal of Dental Education, 20(2), 120–128. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. doi:10.1111/eje.12154

Appendices

Appendix 1. Clinical education program of learning for reflective practice by year group and semester (x indicates type of RP activity completed) (as published in Cook et al. (Citation2022))

Appendix 2: Guiding questions utilized for WRP (As published in Cook et al. (Citation2022)

Appendix 3. Coding schema for written reflective practice, modified from Plack et al. (Citation2005) (first modification for Cook et al., Citation2019, second modification by Cook et al. (Citation2022)