ABSTRACT

This study compared 76 six-year-old children’s performance on matched oral and written narrative retell tasks. Other predictors of children’s written story retell ability were also examined (i.e., oral narrative comprehension, phoneme awareness, spelling, and reading). Analyses of four groups, based on the number of words produced in the oral and written retells, were undertaken to identify the underlying factors contributing to children’s written retell performance. Children’s oral and written retells were strongly correlated on almost every measure, and children produced a significantly greater number of words in their oral retells. Hierarchical linear modelling found that 79% of the variance in written retell scores was explained by ideation (47%) and transcription measures (32%). The findings of this study demonstrate how ideation and transcription skills interact during the writing process and highlight the need for educators to address the key foundational skills that support children’s early writing success, during the first years of instruction.

Introduction

Building upon children’s foundational language skills to enable them to become readers and writers is an important focus during the early years of literacy instruction. Oral language includes both receptive (i.e., listening) and expressive (i.e., talking) modes, and requires understandings of vocabulary, phonology, morphology, syntax, pragmatics, and narrative discourse (Graham, Citation2021; Snow, Citation2020). Written language skills are dependent upon oral language skills, and also require explicit instruction to develop both the receptive (i.e., reading), and expressive (i.e., writing), modes (Graham, Citation2019, Citation2021; Moats, Citation2009, Citation2020; Spencer & Pierce, Citation2023). It is important, therefore, to understand both the relationship, and interaction, between children’s oral and written language skills during their first years at school. In addition, measuring the quantity and quality of young children’s writing presents challenges because these two distinct dimensions are strongly correlated (Kim, Al Otaiba, Folsom, Greulich, & Puranik, Citation2014; Puranik, Duncan, Li, & Ying, Citation2020). The current study utilized both quantitative and qualitative measures to compare six-year-old children’s ability to retell a story in both oral, and written modes to identify and evaluate the key foundational skills that support children’s early writing success.

Narrative skills are commonly measured across oral and written modes using retell tasks, which require children to retell a story that they have heard (Pinto, Tarchi, & Bigozzi, Citation2016; Reese, Suggate, Long, & Schaughency, Citation2010; Westerveld & Gillon, Citation2010b; Wright & Dunsmuir, Citation2019) or narrative production tasks, which require children to formulate their own story (Bigozzi & Vettori, Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2011, Citation2015a). Narrative retell tasks involve children listening to a story, which is usually accompanied by pictures, then retelling the story aloud (oral retell) or in writing (written retell). Oral and written narrative retell tasks have proven to be valid measures of young children’s language skills (Fey, Catts, Proctor-Williams, Tomblin, & Zhang, Citation2004; Westerveld, Gillon, & Boyd, Citation2012), including for bilingual (Lucero & Uchikoshi, Citation2019) and English language learners (Gillon, McNeill, Scott, Gath, & Westerveld, Citation2023; Westerveld et al., Citation2012). A narrative retell task provides children with story structure and content, so may be more supportive than a narrative production task (Westerveld & Gillon, Citation2010a), particularly for those who have language difficulties (Favot, Carter, & Stephenson, Citation2021), or who are English language learners (Lucero & Uchikoshi, Citation2019).

Oral narrative retells have been scored at the macrostructural level (e.g., accurate recall of key events and narrative quality; Reese et al., Citation2010; Schaughency, Suggate, & Reese, Citation2017), the microstructure level (e.g., number of utterances, number of different words, the mean length of utterance; Westerveld & Gillon, Citation2010a, Citation2010b), and a combination of macrostructural and microstructural elements (e.g., Narrative Language Measures that assess story elements and the complexity of the sentences used; Petersen & Spencer, Citation2016). Some studies have assessed children's written narratives using the same scoring methods used for oral narratives (e.g., Bigozzi & Vettori, Citation2016; Pinto, Tarchi, & Bigozzi, Citation2015, Citation2016; Spencer & Petersen, Citation2018). However, comparisons of children’s performance on two comparable tasks, in both the oral and written modes, are relatively scarce in the literature.

The relationship between oral and written language

Empirical research and theoretical models provide valuable direction when considering the link between oral and written language performance. Writing is considered to be the product of two essential components: Transcription (i.e., spelling and handwriting) and ideation (i.e., production and organization of ideas in a text) (Abbott & Berninger, Citation1993; Berninger et al., Citation1992; Juel, Griffith, & Gough, Citation1986). Experimental studies have demonstrated that classroom instruction focused on oral language skills such as vocabulary development and narrative instruction (Arrimada, Torrance, & Fidalgo, Citation2021; Kirby, Spencer, & Chen, Citation2021; Petersen, Mesquita, Spencer, & Waldron, Citation2020; Spencer & Petersen, Citation2018), handwriting (Fancher, Priestley-Hopkins, & Jeffries, Citation2018; Ray, Dally, & Lane, Citation2021; Wanzek, Gatlin, Al Otaiba, & Kim, Citation2017) and spelling (Graham & Santangelo, Citation2014), have all shown to be effective in improving children’s ideation and transcription skills, and therefore should be considered as core components of early literacy instruction. Research evidence, largely from descriptive studies, indicates that variance in children’s written skills can also be attributed to factors beyond ideation and transcription, such as, executive functions and self-regulatory processes (Berninger & Amtmann, Citation2003), working memory (Berninger & Winn, Citation2006; Kim & Schatschneider, Citation2017), higher-order cognitive skills, i.e., inference and theory of mind (Kim & Schatschneider, Citation2017) and attention (Kent, Wanzek, Petscher, Al Otaiba, & Kim, Citation2014), and individual student characteristics, i.e., gender (Adams & Simmons, Citation2019; Coker, Jennings, Farley-Ripple, & MacArthur, Citation2018), motivation (Graham, Berninger, & Fan, Citation2007), and being an English language learner (Zhang, Shen, Pasquarella, & Coker, Citation2022). These factors influence both ideation and transcription processes (Graham, Citation2018; Kim & Schatschneider, Citation2017), yet many cannot be easily or directly addressed by teachers within the context of the classroom. In the following section, the key skills that underpin ideation and transcription are reviewed to clearly define the link between oral and written skills and provide direction for early literacy instruction.

Ideation and oral language

The ideation component of writing is dependent on oral language because thoughts and ideas must be translated into oral language before they can be written down (Kim et al., Citation2015a; Kim et al., Citation2015b). Research has also demonstrated the critical role oral language plays in supporting children to compose written texts. Descriptive studies have examined the influence of children’s oral language skills on their early writing development. For example, in first grade, foundational oral language skills, such as vocabulary and grammatical knowledge, are important for text generation (Kim & Schatschneider, Citation2017). Oral language skills in kindergarten have also been shown to influence writing quality in the first grade (Kent et al., Citation2014) and are predictive of writing quality into the third grade (Kim et al., Citation2015a). Finally, pre-school children’s oral language skills (i.e., sentence structure, word structure, and expressive vocabulary), and the rate at which they develop these skills in the first years at school, have been shown to predict spelling and written composition in kindergarten and first grade (Cabell et al., Citation2021).

Experimental studies measuring the impact of oral language instruction on children’s writing have also provided evidence of a causal relationship between oral and written language. Spencer and Petersen (Citation2018) explored the extent to which six sessions of an oral language intervention programme (Story Champs; Spencer & Petersen, Citation2012) focused on story grammar (i.e., narrative text structure) influenced the writing of seven Grade 1 children. Their results indicated that all but one student showed an improvement in their written narratives, both during the instruction phase, and 3–4 weeks post intervention. However, little improvement was observed in students’ use of language complexity features (e.g., prepositions, verb/noun modifiers, or dialogue), though this had not been a focus of the instruction (Spencer & Petersen, Citation2018). In an action-research study, utilizing a concurrent multiple baseline design involving three groups of kindergarten children (N = 6), Kirby et al. (Citation2021) also found that instruction focused on narrative text structure using the Story Champs intervention improved the quality of children’s written narratives. However, like Spencer and Petersen (Citation2018), this study found no improvement in the complexity of the language used (i.e., sentence quality), leading Kirby et al. (Citation2021) to hypothesize that early writers ‘were only emerging in their oral language repertoires or that transfer to writing requires explicit instruction’ (p. 12). Given the impact of the intervention on children’s oral narrative skills was not measured in either of these studies, it is not possible to examine this hypothesized link between shift in complexity of oral rather than written skills (Kim et al., Citation2014; Shanahan, Citation2006). Research that directly compares children’s performance in matched oral and written narrative tasks is needed to further understand the connection between gains in each mode in response to intervention.

Studies that have focused on comparing oral language and writing have typically focused on comparing children’s oral language at preschool or kindergarten with later writing achievement (e.g., in Grade 1). This approach misses the opportunity to directly compare these skills at a point in time when children are also developing early literacy skills (e.g., handwriting and spelling). Oral language skills have generally been assessed via standardized measures of vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, and sentence repetition (Bigozzi & Vettori, Citation2016; Kent et al., Citation2014; Kim et al., Citation2015a; Pinto et al., Citation2015, Citation2016), although some studies have measured children’s narrative skills (Bigozzi & Vettori, Citation2016; Pinto et al., Citation2015, Citation2016; Spencer & Petersen, Citation2018). Studies that have included an oral narrative measure suggest that this may be a strong predictor of later written narrative competence. For example, a longitudinal descriptive study involving 122 Italian children (mean age = 5.29 years) measured children’s oral narrative competence, phonological awareness, and conceptual knowledge of the writing system at the end of kindergarten, and reported that children’s oral narrative competence in kindergarten was the only significant predictor of their written narrative competence when, at the end of first grade, they were presented with the same story and asked to retell it in writing (Pinto et al., Citation2016). The lack of prediction of the skills underpinning transcription in kindergarten (e.g., phonological awareness, spelling) may be partially explained by the transparent nature of the Italian orthography where transcription is mastered much earlier. Therefore, it is also important to evaluate the connection between the oral and written narratives of emergent learners acquiring English written skills (Georgiou, Torppa, Manolitsis, Lyytinen, & Parrila, Citation2012).

Ideation and transcription

Experimental and descriptive studies directly comparing the ideation component of children’s oral and written narratives, and measures of both ideation and transcription in written narratives, are scarce in the literature. To evaluate a 10-week story-telling intervention, Wright and Dunsmuir (Citation2019) compared concurrent oral and written story retells of 194 6- and 7-year-old children but scored each mode of retelling differently, i.e., oral retells were scored using the total numbers of words and different words, and key points from the original story (i.e., quantitative measures), whereas the written retell was scored using a qualitative tool to obtain scores for handwriting, spelling, punctuation, sentence structure and grammar, vocabulary, organization and structure, and ideas. Although a direct comparison is not possible due to the different scoring systems used across the oral and written tasks, the authors noted that differences found between the oral retell scores of the intervention and comparison groups were not also evident in written retell scores, hypothesizing that this was because the medium of the intervention (i.e., oral) did not transfer skills to a different medium (i.e., written) and that improvements in oral language may take some time to been seen in children’s written language. Some studies have utilized the same measure to compare the ideation component across oral and written modes (e.g., measuring text cohesion, coherence, and structure), though often the only measure of transcription is a separate spelling task (Bigozzi & Vettori, Citation2016; Pinto et al., Citation2015, Citation2016). In their longitudinal descriptive study, Bigozzi and Vettori (Citation2016) examined the narrative skills of 80 Italian children (mean age = 5.3 years) by comparing performance on an oral story production task in kindergarten, with a written story production task and a spelling dictation task at the start of first grade. They reported that the quality of kindergarten oral narrative skills only predicted first-grade written narrative skills for children who did not have spelling difficulties. Further, a similar longitudinal study from kindergarten to second grade undertaken by Pinto et al. (Citation2015) also found that spelling interfered with children’s written narrative competence but observed that for a transparent orthography, such as Italian, the constraining influence of spelling decreased as children moved through second grade.

Although studies comparing ideation across oral and written narratives give some insight into connection across these modalities, to the authors’ knowledge no concurrent comparison study has been conducted that has also evaluated the influence of children’s transcription skills on written retells in English. The exploration of the transcription component of written retells is critical for understanding how ideation and transcription interact in children’s early writing development.

Assessing young children’s oral retell ability provides an insight into the ideation component of early writing. A direct comparison of young children’s oral and written retells also provides an insight into their developing transcription skills, and the degree to which these might constrain the ideation component of their writing (Kim et al., Citation2011; Malpique, Pino-Pasternak, & Roberto, Citation2020; Puranik & Al Otaiba, Citation2012). The review of the literature thus far, has found no concurrent comparison studies that measure both the ideation and transcription components, and the quantitative and qualitative dimensions of children’s oral and written narrative retells after their first year at school.

The current study

This study compared six-year-old children’s ability to retell a story, in both oral and written modes at one time point, to explore how the two essential components of writing, ideation and transcription, interact in children’s early writing. Comparisons of the qualitative and quantitative dimensions of the oral and written retells were followed by an examination of the language and literacy skills, namely, oral narrative comprehension, phoneme awareness, spelling, and reading, that enable children to transfer their oral retell skills to a written retell task. Differences in the language and literacy skills of groups, based on their performance in each retell task, were also explored.

The study addressed the following research questions:

What is the relationship between concurrent measures of children’s oral narrative retell and written narrative retell skills at age six?

What language and literacy skills influence six-year-old children’s written retell ability?

Are there differences in the language and literacy skills of groups based on their relative performance in each mode of retelling?

Materials and methods

Participants

The study was part of broader research examining a teacher-implemented approach to accelerate phoneme awareness, letter-sound knowledge, and vocabulary knowledge during children’s first year at school (Gillon et al., Citation2019, Citation2022; Scott, Gillon, McNeill, & Gath, Citation2022). Following an invitation from the research team, one large urban primary school situated in a high socio-economic community in Auckland, New Zealand, agreed to participate. Approval from the University of Canterbury’s Human Ethics committee was gained prior to the commencement of the study and parental consent was obtained for each child participant. A project information sheet and an assent form were read to each child and children indicated their assent by writing their name. A convenience sample of 76 six-year-old children from two consecutive cohorts of students in their second year of primary school (54% girls, 46% boys; aged 74–81 months; M age = 76.8 months, SD = 1.6) participated in the study. The ethnicity of the participants was New Zealand European (46.1%), Māori (2.6%), Asian (36.8%), Pasifika (2.6%), and Other (11.8%).

Instruments and procedure

Participants were assessed during Term 2 (approximately four months into the academic year), in their second year at school. Measures were administered over 3–4 sessions by primary teachers, trainee speech-language therapists, or research assistants. All assessors were provided with training from the research team and followed an administration manual.

Narrative measures

Children's narrative retell skills were measured via an oral narrative retell and a written narrative retell task.

Oral narrative: The oral retell task was developed by Gillon et al. (Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2023) and was based on the work of Westerveld and Gillon (Citation2010b). High reliability has been reported – with intra-class reliability ranging from 0.81 to 1.00 and interrater reliability as 0.88 (Gillon et al., Citation2023). Children viewed and listened to the story, Tama and the Playground, on the Better Start Assessment website (Better Start Literacy Approach, Citation2021) using a tablet or laptop. Ten pictures and a recorded telling of the story were presented. Assessors told the children,

I brought a book to show you. I have it on my computer. We can’t read this book as it has no words, but I have recorded the story. Let’s look at the book and listen to the story. I will ask you to retell the story afterwards, so that other children can listen to your story next time.

Following a child’s oral retell, their understanding of the story was assessed with five oral narrative comprehension questions relating to the story. The questions included three literal questions (e.g., Who is the story about?) and two inferential questions (e.g., Why did Tama have to stay with his nana?). Children could score up to two points for each question, depending on the correctness and detail of their response, with a possible total score of ten.

Written narrative: The written retell task was designed to align with the oral retell task, so that a direct comparison between children’s oral and written retell performance could be obtained. The written retell of the story, Tama and the Playground, was administered after the oral retell (on a different day), and was completed in small groups, (max. of 4 children). Children viewed and listened to the story on the Better Start Assessment website (Better Start Literacy Approach, Citation2021) using a tablet or laptop. They were then provided with a story template with the same ten sequenced pictures (with four lines underneath each picture) to independently write their own version of the story. They were given the following instructions: ‘Ok, now it's your turn to tell the story, but instead of saying it out loud, we’re going to write it down. You can look at the pictures as you are writing. Let’s start at the beginning’. Children were able to progress through the pictures and write the story at their own pace. Assessors could use the same prompts as in the oral retell such as ‘What happened in the beginning?’ but were not able to provide details or ask questions about specific events.

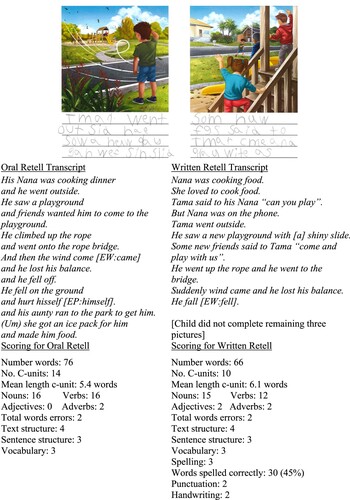

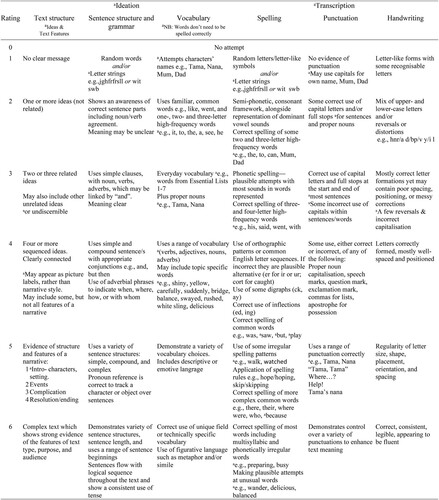

Scoring

The narrative retells were assessed using three different methods: an analysis of language features using Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT), a qualitative scoring tool (QST), and for the written retell only, curriculum-based measures (CBM). The measures were selected to encapsulate the qualitative and quantitative dimensions of the children’s narrative retells. Each measure is described in detail below. An example of a student’s oral and written retells scored using all three measures can be found in Appendix A.

Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT): The oral and written retells were transcribed (with spelling errors corrected), coded (unintelligible or illegible words were coded as X), and then analysed using SALT software (Miller, Gillon, & Westerveld, Citation2017). The scores obtained included:

Total number of words

Total number of c-units – defined as one main clause and subordinate clauses that cannot be further divided without impacting on meaning, (SALT Software LLC, Citation2016) and used as a measure of the number of ideas related to the story.

Mean length of c-unit – used as a measure of syntactic complexity.

Total numbers of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs – used as a measure of semantic diversity

Word level errors (e.g., pronoun errors: she instead of he)

Omitted words (e.g., Nana put [on] a white sling to help …)

Omitted bound morphemes (e.g., omission of regular –ed tense endings)

Qualitative scoring tool (QST): Adapted from the Writing Analysis Tool (WAT; Mackenzie, Scull, & Munsie, Citation2013; Scull, Mackenzie, & Bowles, Citation2020), the QST measured the ideation component of both retells, i.e., text structure (incl. ideas and text features), sentence structure (incl. grammar), vocabulary, and the transcription component of the written retell i.e., spelling, punctuation, and handwriting (see Appendix A ). To align with a narrative retell task, rather than the open story prompt task the WAT was designed for, adaptions were made to several of the descriptors for text structure, vocabulary, and spelling. Students were rated on a scale from 0 to 6 for each component, with the totalled scores forming the QST total. Students who would not attempt the writing task and made no marks or letters on the page were rated as zero for each component.

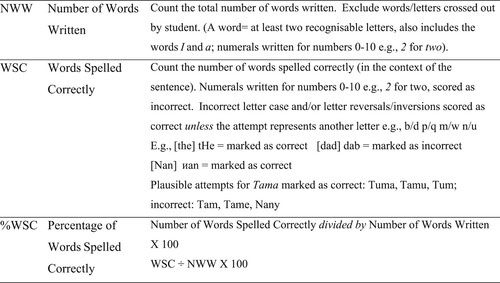

Curriculum-based measurement (CBM): This is a quantitative assessment that analyses the number and accuracy of letters and words within a sample of writing (Hosp & Hosp, Citation2003; Jewell & Malecki, Citation2005; Powell-Smith & Shinn, Citation2004). For Grade 1, test-retest and alternate-form reliability for 5-min story-prompt writing samples has been reported as r = .68 to .78 for the number of words written and r = .65 to .82 for words spelled correctly, and criterion validity scores of r = .47 for the number of words written and r = .51 for words spelled correctly (McMaster, Du, & Pétursdéttir, Citation2009). The written retell was scored using the following metrics: number of words written (a word = at least two recognizable letters, also includes words I, and a, and numerals for words e.g., 2 for two), number of words spelled correctly (numerals for words e.g., 2 for two scored as incorrect), and percentage of words spelled correctly (see Appendix A ).

Other measures

In addition to the narrative measures described above, the following measures were also administered to gain insight into how foundational literacy knowledge contributed to early written narrative performance.

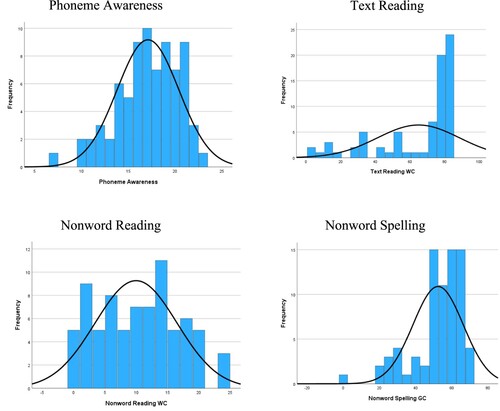

Phoneme awareness: This was assessed through two measures, phoneme segmentation and phoneme blending. The measures were developed by Gillon et al. (Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2022) and based on subtests from the Computer Based Phonological Awareness Assessment Tool (CBPAT; Carson, Gillon, & Boustead, Citation2011). These tasks have demonstrated good reliability and validity (Carson, Boustead, & Gillon, Citation2015; Gillon, McNeill, Scott, & Arrow, Citation2022). Tasks were administered using the Better Start Assessment website (Better Start Literacy Approach, Citation2021) on a tablet or laptop. Scores were totalled to give an overall phoneme awareness score out of 24.

Phoneme segmentation: Children were asked to identify the number of phonemes in a target word. They were presented with a picture (e.g., a sun) with five phoneme boxes underneath and asked to segment the word into phonemes and click a box to count each phoneme. Twelve test items were presented, and one point awarded for each correctly segmented word. Cronbach’s alpha for these 12 items has been reported as 0.57 (Gillon et al., Citation2022).

Phoneme blending: Children were presented with three pictures (e.g., cake, cape, ring). The target word (e.g., cake) was segmented into individual phonemes and children were asked to blend phonemes together to form the segmented word and select the corresponding picture. Twelve test items were presented, and one point awarded for each correctly identified word. Cronbach’s alpha for these 12 items has been reported as 0.83 (Gillon et al., Citation2022).

Nonword tasks: These tasks measured children’s ability to use their letter-sound knowledge, phoneme blending, and phoneme segmenting skills to decode (i.e., read) and encode (i.e., spell) nonwords. These measures were developed by (Gillon et al., Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2022) and have demonstrated good reliability (Gillon et al., Citation2022).

Nonword reading: Children were asked to read 24 non-words (e.g., tid, ret). Two practice items were included to familiarize children with the task. The total number of graphemes (out of 80) read correctly were collected for analysis. Children’s responses were audio recorded to monitor scoring fidelity. Cronbach’s alpha across the first ten items has been reported as 0.96 and intertester reliability for non-word reading (graphemes correct) ranged from 0.95 to 1.00 (Gillon et al., Citation2022).

Nonword spelling: Children were asked to spell 10 non-words (e.g., fap, mub). Two practice items were included to familiarize children with the task. The total number of graphemes (out of 68) spelled correctly were collected for analysis. Cronbach’s alpha across the ten items has been reported as 0.96 and intertester reliability for non-word spelling (graphemes correct) ranged from 0.99 to 1.00 (Gillon et al., Citation2022).

Text reading: The text reading task was a novel task developed as part of the Better Start Literacy Approach (see Gillon et al., Citation2022). It measured children’s ability to apply their decoding and language skills in the reading of a connected text. Children were provided an unseen text, Dot the Pig (84 words), and the assessor said, ‘Here is a story about Dot the pig. She likes to play outside. Let’s see what she is going to do. Read the story to me. If you don’t know a word, then try it aloud and keep reading’. Children’s responses were audio recorded to monitor scoring fidelity. Reading behaviours were noted, and all word attempts were coded using standardized conventions for correct responses, substitutions, omissions, insertions, attempts, repetitions, appeals, told words, and self-corrections. After 12 errors, the assessor said ‘Well done! Let’s finish this story off together’, and noted where the student finished reading the text. Scoring includes the number of words read, the number of errors, the number of words read correctly.

Reliability

Oral and written retells: Twenty percent of the oral and written retells were randomly selected for reliability scoring. Oral retell audio recordings and written retells were re-transcribed and coded by an independent assessor. Interrater reliability was calculated as the intra-class correlation (ICC) between the two sets of scores. ICCs for the 10 variables derived from SALT coding for each retell showed one to be moderately reliable (oral retell mean length of c-unit = 0.67), four demonstrated good reliability (0.78–0.86), and 15 showed excellent reliability (0.91–1.00). For curriculum-based measure scoring, the written retells were re-scored by an independent assessor. Points of difference were identified and discussed until agreement was reached, and one assessor then rescored all remaining retells.

For qualitative scoring (QST), initial exact rater agreement percentages for the oral retell were 56% for both text structure and sentence structure, and 75% for vocabulary, and for the written retell, 40% for text structure, 60% for sentence structure and handwriting, 67% for spelling and punctuation, and 27% for vocabulary. Obtaining interrater reliability using qualitative scoring, particularly for young children’s writing, can be challenging (Puranik & Al Otaiba, Citation2012). McKenna, Dedrick, and Goldstein (Citation2021) found that widening the tolerance of scores to within one point demonstrated a high level of agreement using this approach. The 1-point discrepancy scoring agreement between both raters for the oral retell was 100% for text structure, sentence structure, and vocabulary, and for the written retell it was 93% for text structure, sentence structure and vocabulary, and 100% for spelling, punctuation, and handwriting. After the initial reliability scoring, assessors discussed points of ambiguity or difference until agreement was reached, and then one assessor rescored all remaining retells.

Oral narrative comprehension: Interrater reliability for the oral narrative comprehension questions was obtained by a single assessor re-scoring 20% of the audio-recorded responses. The ICC between the two sets of scores was 0.85.

Other literacy measures: Interrater reliability for nonword reading, nonword spelling, and text reading was obtained by a single assessor re-scoring 20% of the audio recorded or written responses. The ICC between the two sets of scores for graphemes correct was 1.00 for both nonword reading and nonword spelling, and 1.00 for text reading words correct.

Results

Data analysis

Statistical analyses examined the relationships between children’s scores on the oral and written retell tasks, and between the written retell and other literacy measures. Of the 76 participants, two children would not attempt either retell, and one child did not attempt the written retell. The written retells of 11 children who did not write at least one c-unit, or were difficult to decipher due to inaccurate spelling, were unable to be transcribed for SALT analysis. In total, 76 children’s oral and written retells were compared using measures for the number of words written and the number of words spelled correctly, and the QST, and 62 underwent further analysis using SALT.

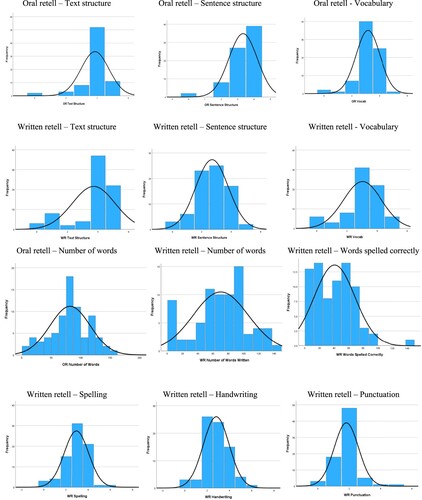

Preliminary analyses were also conducted to assess parametric test assumptions for normality, linearity, and variance. The Shapiro–Wilk test indicated that several variables were not normally distributed, particularly for variables scored using the QST (e.g., text structure). However, nearly all fell within the acceptable range (−3 to +3) for skewness and kurtosis (Abbott, Citation2011). Levene’s test also identified a small number of variables for which homogeneity of variance between the groups could not be assumed. For analyses involving variables for which parametric test assumptions were not wholly met, non-parametric analyses were also undertaken.

Descriptive statistics

Children produced an average of 81.7 words (0–155; SD = 33.9) in the oral retell, and 70.2 words (0–149; SD = 36.2) in the written retell. Out of a maximum total of 18, QST scores for ideation (i.e., text structure, sentence structure, and vocabulary) averaged 10.3 (0–13; SD = 2.4) for the oral retell, and 9.4 (0–15; SD = 3.6) for the written retell. For the written retell, the average number of words spelled correctly was 40 (0–142; SD = 27.3) and the average score for the transcription total (i.e., spelling, handwriting, and punctuation) was 7.5 out of a maximum of 18 (0–17; SD = 2.8). Descriptive statistics for all measures can be found in the Appendix B , and distributions for all QST measures, the number of words, words spelled correctly, and the other literacy measures can be found in Appendix B .

Relationship between the oral and written narrative retell

Comparisons were made between the oral and written retell scores to determine the concurrent relationship between children’s ability to retell the narrative in each mode, thus giving insight into the ideation component of writing. Measures for each mode of retell e.g., the number of words produced, were analysed using the Pearson correlation coefficient (see below), followed by paired samples t tests to determine the significance of any difference (see Appendix B ). There was a strong positive correlation between the number of words produced (r = .50, p < .001) in each mode of retell. In addition, the number of words children said in their oral retells significantly correlated with every written retell measure except the number of adjectives. Mean quantitative ideation scores (i.e., number of words and number of c-units) for the oral retell were higher than for the written retell, and paired samples t test results showed that the differences were significant for the number of words (t = 2.86, p = .006), but not for the number of c-units (t = 1.40, p = .168). This suggests that while children may produce longer oral retells, the number of ideas (i.e., c-units) included do not significantly differ between the two modes.

Table 1. Correlations between oral and written retell measures.

The quality of ideation was compared using QST scores for text structure, sentence structure and vocabulary, as well as the number of word errors and omissions. Text structure, sentence structure, and vocabulary were strongly correlated between both retells (rs = .56, .56, .53, ps < .001). In the written mode, more children (n = 22, 29%) scored a five for text structure compared to the oral retell, where only 11 children (15%) were rated as five. A similar pattern was observed for vocabulary, with six children (8%) scoring five in the written retell compared to only one (1%) scoring five in the oral retell. Errors, such as omitted bound morphemes (e.g., want instead of wanted), were also strongly correlated (r = .68, p < .001) and word level errors (e.g., was instead of were), were moderately correlated (r = .42, p < .001). There was no evidence of a relationship between children omitting words when retelling the story orally, or in writing (r = .05, p =.705), though they were more likely to omit bound morphemes in their written retells (t = −2.58, p = .012). On average, children constructed better quality sentences in their oral retells (t = 5.80, p < .001), with 87% scoring a three or four for sentence structure on the QST, in comparison to 55% of children scoring a three or four in the written retell. Interestingly, no child scored above four for sentence structure in their oral retell, yet, despite lower mean sentence structure scores for the written retell, two children (3%) produced written sentences that were rated as five. The relative quality and complexity of the language produced in each retell were further determined by comparisons made between the length of c-units, and numbers of nouns (e.g., playground), verbs (e.g., play), adjectives (e.g., new), and adverbs (e.g., off). Between each retell, mean c-unit length was moderately correlated (r = .36, p = .001) and, on average, children produced significantly longer c-units (t = 3.63. p < .001) in their oral retells. There were also moderate to strong correlations found between children’s use of nouns (r = .32, p < .001) and adverbs (r = .51, p < .001), with significantly more adverbs included in the oral retells (t = 4.31, p < .001). There was a weak correlation, but no difference found in the use of verbs (r = .27, p = .037; t = 1.37, p = .175), and no correlation or difference in children’s use of adjectives (r = .02, p = .880; t = 0.72, p = .473) between the two retells.

For the written retell, there were strong positive correlations between each transcription measure (i.e., spelling, handwriting, and punctuation) and the number of words written, text structure, sentence structure and vocabulary (rs = .62 - .78, ps < .001). Unexpectedly, only handwriting related to any type of word error, being positively correlated with omitted bound morphemes in the written retell (r = .30, p = .05).

Language and literacy skills that support early writing

The second question in this study examined the language and literacy skills that influence children’s early writing ability. Comparisons were made using the Pearson correlation coefficient between selected retell measures (e.g., oral retell comprehension, the number of words, ideation total) and all literacy measures (e.g., phoneme awareness, nonword spelling, text reading), followed by hierarchal linear regression analysis to assess how these component skills influenced children’s performance on the written retell task. Children’s understanding of the story, another measure of ideation, was determined by their responses to the five oral narrative comprehension questions. Bivariate correlations between narrative comprehension and all oral and written retell measures can be found in . Comprehension scores demonstrated moderate to strong correlations across both modes of retell for the number of words, text structure, sentence structure, and vocabulary (rs = .38 - .62, ps < .001), however, a moderate correlation for the mean length of c-units (r = .30, p = .01) was only observed for the oral retell. No significant correlations were found between oral narrative comprehension and the use of adjectives, adverbs, and word errors and omissions, in either mode of retell.

The comparisons presented so far show the quantity (i.e., number of words: r = .50, p < .001) and quality of ideation (i.e., ideation total: r = .60, p < .001) to be strongly correlated between the oral and written retells, and transcription is strongly and positively correlated to written retell ideation (i.e., number of words: r = .75, p < .001; ideation total: r = .79, p < .001). This suggests that children with sufficiently developed transcription skills are more likely to be able to produce oral and written retells of comparable quality.

Next, was an investigation into the other literacy skills (i.e., phoneme awareness, nonword reading, nonword spelling, and text reading) thought to influence children’s writing performance. Bivariate correlations between retell measures and other literacy measures are presented in . With the exception of phoneme awareness and handwriting, moderate (rs = .39–.47) to strong (rs = .51–.73) correlations were observed between all literacy and written retell measures. Overall, the literacy measures did not correlate as strongly with handwriting and punctuation, in comparison to spelling and ideation measures. Further, phoneme awareness demonstrated weaker correlations in comparison to nonword reading, nonword spelling, and text reading. After an examination of all correlations, five measures (i.e., oral retell comprehension, oral retell number of words, written retell handwriting, nonword spelling, and text reading) were selected for further analysis.

Table 2. Correlations between retell and other literacy measures.

Prior to performing the regression analyses, tolerance indices were examined to identify potential issues related to multicollinearity. An examination of the variance inflation index (VIF) showed no multicollinearity in the data. Hierarchal linear regression analysis was then performed to assess the component skills that influenced children’s performance on the written retell task (see ). The dependent variable was the combined writing QST scores for text structure, sentence structure, vocabulary, spelling, and punctuation. Oral narrative comprehension and the number of words said were entered at Step 1 as control variables, explaining 47% of the variance in the children’s written retell scores, R² = .47; F(2, 73) = 32.09, p < .001. After entering the written retell handwriting QST score, nonword spelling, and text reading at Step 2, the total variance explained by the model was 79%, R² = .79; F(3, 70) = 36.06, p < .001. The three variables entered at Step 2 explained an additional 32% (ΔR² = .32) of the variance in children’s written retell scores. In the final model, four variables explained statistically significant unique variance in children’s written retell ability: handwriting (β = .36, p < .001), nonword spelling (β = .36, p < .001), oral narrative comprehension (β = .19, p = .005), and the number of words spoken in the oral retell (β = .19, p = .003).

Table 3. Hierarchical linear regression for written narrative retell.

Group differences in underlying language and literacy skills

To answer the third research question, an analysis of groups within the sample investigated the relationship between children’s performance on each retell task, and explored factors that may have influenced the written retell results. Children were divided into four groups based on their achievement relative to the mean scores for the number of words produced in the oral and written retell tasks. The number of words children said or wrote strongly correlated to other retell measures and was operationalized as a measure of the overall quality of each retell (Puranik & Al Otaiba, Citation2012). Children who scored at or below the mean number of words for both retells were assigned to Group 1 Below both, those scoring above the mean for the oral retell and at, or below, the mean for the written retell were assigned to Group 2 Below written, those scoring at, or below, the mean for the oral retell and above the mean for the written retell were assigned to Group 3 Below oral, and children who produced above the mean number of words for both the oral and written retell were assigned to Group 4 Above both (see below).

Table 4. Demographics of groups based on number of words produced in each retell.

To address potential violations of parametric test assumptions for normality, linearity, and variance that were identified in the preliminary analyses, both parametric and non-parametric testing were undertaken. A series of one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and independent-samples Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted to explore group differences across a range of measures. The means and standard deviations for each group can be found in Appendix B . Group differences in measures for oral narrative comprehension, ideation (totalled scores for text structure, sentence structure and vocabulary), handwriting, spelling, punctuation, nonword spelling, nonword reading, and text reading were statistically significant across both tests (see below). It is important to note that the QST ideation measure correlates significantly with the number of words produced (r = .76, p = .01) i.e., the measure used to determine the placement of children into each group, therefore, to avoid confounding the results, the oral narrative comprehension scores have also been included in group comparisons as a measure of oral narrative ideation.

Table 5. Results for group differences.

Post hoc Scheffe and Kruskal–Wallis tests identified significant differences between the groups who wrote below the mean number of words in their written retells i.e., Group 1 Below both and Group 2 Below written, and those who wrote above the mean number of words i.e., Group 3 Below oral and Group 4 Above both (see Appendix B ). Group 1 had significantly lower scores than Group 4 for oral narrative comprehension and oral retell ideation, and lower scores than both Group 3 and 4 for written retell ideation, handwriting, spelling, and punctuation. Group 1 also had significantly lower scores than Group 4 for nonword spelling, nonword reading, and text reading. Significant differences were also found between Group 2 and Group 3 for handwriting, spelling, and text reading. No significant group differences between any of the groups were found for phoneme awareness, word errors or word omissions. The only significant difference between Groups 3 and 4 was Group 3’s lower score for oral retell ideation, which would be expected because these children produced fewer words in their oral retell, than those in Group 4.

For the two groups that demonstrated similar oral narrative retell ability i.e., scored above the mean number of words said but differed in the number of words written, results revealed that in comparison to children in Group 4 Above both, the scores of children in Group 2 Below written were significantly lower for written retell ideation, handwriting, spelling, nonword reading, nonword spelling, and text reading. There were no significant differences found between the two group’s oral narrative comprehension, oral retell ideation, word errors, or word omissions.

Discussion

This study compared six-year-old children’s ability to retell a story in both the oral and written modes to identify key foundational skills that support early writing success. Children produced significantly more words, a greater number of adverbs, and better-quality sentences in their oral retells compared to their written retell attempts of the same story. Hierarchical linear modelling found that 79% of the variance in written retell scores was explained by ideation (47%) and transcription measures (32%), and post hoc group comparisons revealed significant differences in the writing performance of children who had lower scores on transcription related measures (e.g., handwriting, nonword spelling).

The first research question compared children’s ability to retell a story orally and then in writing. Comparisons indicated that whilst children’s oral and written retells were correlated on almost every measure, in line with previous studies (Fey et al., Citation2004), most children produced a significantly greater number of words in the oral mode, in comparison to the written. As has also been widely reported in the literature (Kim et al., Citation2011; Puranik & Al Otaiba, Citation2012), transcription skills (i.e., spelling, handwriting and punctuation) were strongly and positively correlated with the quantity of words written and the quality of the text structure, sentence structure and vocabulary used in the written retell. However, the written retells that were excluded from the SALT analysis, due to limited or undecipherable text, may have influenced comparisons between the oral and written retells because students with less developed transcription skills were under-represented. For example, 13 (37%) of the 35 children in Groups 1 and 2 produced texts that couldn’t be scored on all writing measures. This is unsurprising given their low scores for transcription and other literacy related measures in comparison to Groups 3 and 4, who, by contrast, had only one written retell (2%) that couldn’t be transcribed for SALT analysis.

Overall, the accuracy and complexity of children’s sentences in the oral retell appears to be greater due to the significant difference in the mean length of c-units and the mean sentence structure score (Westerveld & Gillon, Citation2010a). These differences were largely due to more children having greater difficulty constructing complete sentences in the written retell, indicating that for many children, the transcription process may have interfered with their ability to compose correct or complete sentences (Kim et al., Citation2011). The vocabulary used in the oral and written story retelling was closely related; except for more adverbs used in the oral retell, no significant differences in the mean vocabulary score, the number of nouns, verbs, adjectives, omitted words, and word errors was seen. This indicates that for children who were able to write at least one c-unit (i.e., a simple sentence), the quality of the language used is comparable between both retells, and children who make word errors and word omissions in their oral retelling of the story, are also likely to make these types of errors in their written retell (Fey et al., Citation2004).

A greater number of omitted bound morphemes in the written retell could be related to a child’s spelling skills, rather than difficulties with grammar. However, for the written retells scored using SALT analysis, there was no evidence of a correlation between omitted bound morphemes, and either of the spelling measures. Only data related to the participants’ ethnicity was available, not their English language learning (ELL) status, however, 75% of the children who made bound morpheme errors in their oral retells were classified as either Asian, Pasifika or ‘other’, suggesting ELL status might have been a factor. Further, the unexpected positive correlation between the quality of children’s handwriting and bound morpheme errors may have been a result of children with proficient handwriting skills who are learning English as a second language because 75% of the children who scored four (i.e., one standard deviation above the mean) for handwriting (M = 2.8, SD = 1.17), were classified as either Asian or ‘other’. Interestingly, Zhang et al. (Citation2022) reported that the only significant difference found in a written composition task, was better handwriting scores for ELL students, in comparison to their native-English-speaker peers. The findings presented so far, demonstrate how children’s oral language skills can influence the quality of their writing and highlights the importance of teaching vocabulary and grammatically correct sentence structures (Kirby et al., Citation2021; Petersen, Staskowski, Spencer, Foster, & Brough, Citation2022; Spencer & Petersen, Citation2018), particularly for English language learners (Zhang et al., Citation2022), as well as spelling and handwriting.

The quality of text structure and the range of the vocabulary used may be influenced by the very nature of a retell task (Lucero & Uchikoshi, Citation2019). Mean scores for text structure and the number of c-units (i.e., ideas) were similar across both retells, and this may have been a result of the support provided by the sequenced story pictures that reduced the demands on children’s memory capabilities. A story production task, where children must create their own story, may yield different results because children will have to employ greater cognitive resources in formulating their own ideas (Lucero & Uchikoshi, Citation2019). Children with less developed transcription skills may struggle to coherently generate text and may only write words they are confident in being able to spell (Kim et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, a retell task could have a ceiling effect on the complexity of the ideas and vocabulary children are able to demonstrate, i.e., children only use ideas and words from the story (Piasta, Groom, Khan, Skibbe, & Bowles, Citation2018).

In the written retell, more children attained higher qualitative ideation scores (i.e., scores of five) in comparison to the oral retell, meaning more written retells displayed evidence of the structure and features of a narrative, and a greater variety of sentence structures (e.g., compound and complex) and vocabulary (e.g., descriptive or emotive words). This suggests that for some children, the act of writing better engaged their narrative story telling skills. It may have been that children had more time to think during the writing process and, provided they possessed adequate transcription skills, could re-read and revise what they had written as they wrote (Gillam & Johnston, Citation1992), whereas in the oral retell, the child is retelling the story to an adult ‘in-the-moment’ and may be less inclined to retell it in the style of a narrative (i.e., ideas constructed more as captions of what is happening in each picture). in Appendix A provides an example of a child’s oral retell that is structured more as picture captions, and the corresponding written retell from the same child illustrates a more narrative style.

The second research question examined the influence of key skills thought to underpin ideation and transcription. Moderate to strong correlations found between numerous written retell measures, and the other language and literacy measures highlight the importance of both ideation and transcription in children’s early writing. Moreover, the influence of children’s oral language skill was clearly demonstrated, accounting for 47% of the variance in children’s written retell scores for ideation, spelling, and punctuation. An additional 32% of the variance was attributed to handwriting and spelling, the two key aspects of transcription (Graham, Harris, & Adkins, Citation2018; Kim & Schatschneider, Citation2017). Similar to findings of Kim et al. (Citation2011), reading skill was not uniquely related to writing once oral language, spelling, and handwriting were taken into account. However, the connected text read largely consisted of ‘decodable’ words, and scores were significantly correlated to nonword reading and nonword spelling. In addition, text reading scores were negatively skewed, indicating a ceiling effect. It is possible that a more challenging text that included more orthographically irregular words might have contributed to additional variance.

The third research question examined differences between groups that were based on their performance in each retell task. Analyses confirmed the initial findings of the hierarchical regression analysis: Children who produced fewer words for both retells (i.e., Group 1 Below both) had lower scores for language skills (e.g., oral narrative comprehension and oral retell ideation) and transcription skills (i.e., handwriting, spelling, and punctuation), in comparison to children who wrote a greater number of words (i.e., Group 3 and Group 4). However, the results of comparisons between the other three groups suggest that whilst children’s oral narrative comprehension and oral retell skills underpin their ability to retell a story in the written mode, they must also possess the requisite transcription skills to be able to translate their ideas into writing (Graham, Berninger, Abbott, Abbott, & Whitaker, Citation1997; Kent & Wanzek, Citation2016).

Differences observed in the quality of children’s written retells were influenced more by the foundational literacy skills that support transcription, rather than their oral narrative skills (i.e., ideation). For example, children who demonstrated a similar level of ability in their oral retells (i.e., Group 2 and Group 4) but differed significantly in their transcription skills (i.e., Group 2), were less able to transfer their ideas into writing. It seems likely that Group 2’s less developed foundational literacy skills (i.e., phoneme segmentation, phoneme blending, letter-sound knowledge, and handwriting), constrained their ability to demonstrate their oral retell skills in a written retell task (Kim et al., Citation2011; Malpique et al., Citation2020; Puranik & Al Otaiba, Citation2012).

Despite Group 3 having lower oral retell scores in comparison to Group 4, there were no significant differences between any of the written retell or foundational literacy measures (e.g., nonword spelling, nonword reading, text reading), though it is worth noting here that this may have been due to some Group 3 children being shy or reluctant to retell the story aloud but were willing and able to retell the story in writing. However, Group 3 children also had lower oral retell scores than Group 2, yet outperformed them on all written retell measures, except punctuation, raising the possibility that in a retell task, adequate transcriptions skills may compensate for less proficient oral narrative skills in early writers. These findings are consistent with Kent et al. (Citation2014), who reported that individual differences in oral language did not relate to grade one children’s writing fluency, hypothesizing that as writing production becomes less constrained by transcription, language skills are more likely to exert a greater influence on writing quality. This also aligns with Bigozzi and Vettori's (Citation2016), and Pinto et al's (Citation2015) findings, that spelling difficulties influence grade one Italian children’s writing over and above the influence of their oral narrative competence.

Finally, for the group of children who attained the highest mean scores across all ideation and transcription measures (i.e., Group 4), no significant differences were found in the ideation scores or the number of words they produced in either mode of retell. This is in line with Fey et al. (Citation2004) who reported that though the oral narratives of second grade children were longer than their written narratives, between second and fourth grade, the differences in the length, complexity, and quality of children’s oral and written narratives began to lessen. It also suggests that for some children, as they move through their second year of school, the constraining influence of transcription skills (i.e., spelling) on their writing is somewhat reduced, thus aligning with Pinto et al's (Citation2015) observations of children’s writing growth in a more transparent orthography, such as Italian.

Implications for practice

The findings of this study have demonstrated how transcription and ideation interact during the writing process and highlights the need for collaboration between teachers and specialists (e.g., speech language pathologists or literacy specialists) to address the key skills beginning writers need to develop, particularly for children identified as having oral and/or written language difficulties. Children’s oral language skills lay the foundation upon which children’s written skills are built, therefore, guided by specialists, teachers should provide learning activities that continue to grow oral narrative and vocabulary skills throughout the early years of school (Gillam, Olszewski, Fargo, & Gillam, Citation2014; Gillon et al., Citation2019; Scott et al., Citation2022), whilst at the same time, ensuring children acquire the early literacy skills required to develop proficient transcription skills (i.e., explicit handwriting and spelling instruction) (Berninger et al., Citation1997; Graham et al., Citation2018; Puranik & Al Otaiba, Citation2012). In addition, for children with more complex learning needs who require additional support (i.e., those with speech language difficulties or who are learning English as an additional language), the inclusion of writing goals within treatment will provide opportunities for children to develop language in both the oral, and written modes.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to make concurrent comparisons of six-year-old children’s oral and written retell ability. In addition, the comparisons made between each mode of retell, utilized both quantitative and qualitative measures and provided a level of detail that, as far as we are aware, has not previously been reported. As noted in the discussion, a limitation of this study was that children with less developed transcription skills produced writing that was difficult to read due to inaccurate spelling or letter formation. To ensure all aspects of ideation can be measured for all written retells, future studies should include procedures, such as those outlined by (Johnson & Grant, Citation1989), that require task administrators to ask each child to read back their written retells and transcribe any misspelt, omitted, or illegible words to allow detailed analysis. Further, unlike spelling, the only measure of handwriting was within the context of the written retell task. Future studies should consider the inclusion of a separate handwriting measure that is less likely to be influenced by the cognitive demands of spelling and generating ideas, e.g., handwriting fluency tasks (Kim et al., Citation2011; Puranik, Al Otaiba, Folsom Sidler, & Greulich, Citation2014). Finally, reliability data highlight the challenges of assessing the quantitative and qualitative dimensions of early writing, and further development of the measurement tools to improve interrater agreement is warranted.

Summary

The results of this study have confirmed the findings of previous studies demonstrating the importance of the language and literacy skills that underpin ideation and transcription. A direct comparison of six-year-old children’s ability to retell a narrative in the oral and written modes has provided further insight into the pivotal role transcription skills play, over and above the influence of oral language skills, in enabling beginning writers to transfer their ideas into writing. The findings of this study further highlight the need for early instruction to focus on the language and literacy skills required for young children to develop both the ideation and transcription components of writing, particularly for those with oral and/or written language difficulties.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the children, teachers, and research assistants who participated in this project. We would also like to thank Dr Megan Gath (Child Well-being Research Institute) for the support provided during data analysis. This work was supported by the A Better Start National Science Challenge under Grant Number 15-02688.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott, M. L. (2011). Understanding educational statistics using Microsoft Excel® and SPSS® (1st ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Abbott, R. D., & Berninger, V. W. (1993). Structural equation modeling of relationships among developmental skills and writing skills in primary- and intermediate-grade writers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(3), 478–508. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.85.3.478

- Adams, A. M., & Simmons, F. R. (2019). Exploring individual and gender differences in early writing performance. Reading and Writing, 32(2), 235–263. doi:10.1007/s11145-018-9859-0

- Arrimada, M., Torrance, M., & Fidalgo, R. (2021). Response to intervention in first-grade writing instruction. A large-scale feasibility study. Reading & Writing, 35(4), 943–969. doi:10.1007/s11145-021-10211-z

- Berninger, V., Yates, C., Cartwright, A., Rutberg, J., Remy, E., & Abbott, R. (1992). Lower-level developmental skills in beginning writing. Reading and Writing, 4(3), 257–280. doi:10.1007/BF01027151

- Berninger, V. W., & Amtmann, D. (2003). Preventing written expression disabilities through early and continuing assessment and intervention for handwriting and/or spelling problems: Research into practice. In H. L. Swanson, K. R. Harris, & S. Graham (Eds.), Handbook of Learning Disabilities (pp. 345–363). New York: Guilford Press.

- Berninger, V. W., Vaughan, K. B., Abbott, R. D., Abbott, S. P., Rogan, L. W., Brooks, A., … Graham, S. (1997). Treatment of handwriting problems in beginning writers: Transfer from handwriting to composition. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(4), 652–666. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.89.4.652

- Berninger, V. W., & Winn, W. D. (2006). Implications of advancement in brain research and technology for writing development, writing instruction, and educational evolution. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of Writing Research (pp. 96–114). New york: Guilford Press.

- Better Start Literacy Approach. (2021). Better start assessment. https://bsla.azurewebsites.net/login.

- Bigozzi, L., & Vettori, G. (2016). To tell a story, to write it: Developmental patterns of narrative skills from preschool to first grade. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31(4), 461–477. doi:10.1007/s10212-015-0273-6

- Cabell, S. Q., Gerde, H. K., Hwang, H., Bowles, R., Skibbe, L., Piasta, S. B., … Justice, L. (2021). Rate of growth of preschool-age children’s oral language and decoding skills predicts beginning writing ability. Early Education and Development, 33(7), 1198–1221. doi:10.1080/10409289.2021.1952390.

- Carson, K., Boustead, T., & Gillon, G. (2015). Content validity to support the use of a computer-based phonological awareness screening and monitoring assessment (Com-PASMA) in the classroom. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(5), 500–510. doi:10.3109/17549507.2015.1016107

- Carson, K., Gillon, G., & Boustead, T. (2011). Computer-administrated versus paper-based assessment of school-entry phonological awareness ability. Asia Pacific Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing, 14(2), 85–101.doi:10.1179/136132811805334876

- Coker, D. L., Jennings, A. S., Farley-Ripple, E., & MacArthur, C. A. (2018). When the type of practice matters: The relationship between typical writing instruction, student practice, and writing achievement in first grade. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 54(June), 235–246.doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.06.013

- Fancher, L. A., Priestley-Hopkins, D. A., & Jeffries, L. M. (2018). Handwriting acquisition and intervention: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, and Early Intervention, 11(4), 454–473. doi:10.1080/19411243.2018.1534634

- Favot, K., Carter, M., & Stephenson, J. (2021). The effects of oral narrative Intervention on the narratives of children with language disorder: A systematic literature review. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 33(4), 489–536. doi:10.1007/s10882-020-09763-9

- Fey, M. E., Catts, H. W., Proctor-Williams, K., Tomblin, J. B., & Zhang, X. (2004). Oral and written story composition skills of children with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 47(6), 1301–1318.

- Georgiou, G. K., Torppa, M., Manolitsis, G., Lyytinen, H., & Parrila, R. (2012). Longitudinal predictors of reading and spelling across languages varying in orthographic consistency. Reading and Writing, 25(2), 321–346. doi:10.1007/s11145-010-9271-x

- Gillam, R. B., & Johnston, J. R. (1992). Spoken and written language relationships in language/learning-impaired and normally achieving school-age children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35(6), 1303–1315. doi:10.1044/jshr.3506.1303

- Gillam, S. L., Olszewski, A., Fargo, J., & Gillam, R. B. (2014). Classroom-based narrative and vocabulary instruction: Results of an early-stage, nonrandomized comparison study. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(4), 204–219.doi:10.1044/2014_LSHSS-13-0008

- Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Denston, A., Scott, A., & Macfarlane, A. (2020). Evidence-based class literacy instruction for children with speech and language difficulties. Topics in Language Disorders, 40(4), 357–374. doi:10.1097/TLD.0000000000000233

- Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Scott, A., & Arrow, A. (2022). A better start literacy approach: effectiveness of Tier 1 and Tier 2 support within a response to teaching framework. Reading and Writing, 36, 565–598. doi:10.1007/s11145-022-10303-4

- Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Scott, A., Denston, A., Wilson, L., Carson, K., … Macfarlane, A. H. (2019). A better start to literacy learning: Findings from a teacher-implemented intervention in children’s first year at school. Reading and Writing, 32(8), 1989–2012. doi:10.1007/s11145-018-9933-7

- Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Scott, A., Gath, M., & Westerveld, M. (2023). Retelling stories: The validity of an online oral narrative task. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 39(2), 150–174. doi:10.1177/02656590231155861.

- Graham, S. (2018). A revised writer(s)-within-community model of writing. Educational Psychologist, 53(4), 258–279. doi:10.1080/00461520.2018.1481406

- Graham, S. (2019). Changing how writing is taught. Review of Research in Education, 43(1), 277–303. doi:10.3102/0091732X18821125

- Graham, S. (2021). A walk through the landscape of writing: Insights from a program of writing research. Educational Psychologist, 57(2), 55–72. doi:10.1080/00461520.2021.1951734.

- Graham, S., Berninger, V., & Fan, W. (2007). The structural relationship between writing attitude and writing achievement in first and third grade students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32(3), 516–536. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2007.01.002

- Graham, S., Berninger, V. W., Abbott, R. D., Abbott, S. P., & Whitaker, D. (1997). Role of mechanics in composing of elementary school students: A new methodological approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(1), 170–182.doi:10.1037//0022-0663.89.1.170

- Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & Adkins, M. (2018). The impact of supplemental handwriting and spelling instruction with first grade students who do not acquire transcription skills as rapidly as peers: A randomized control trial. Reading and Writing, 31(6), 1273–1294. doi:10.1007/s11145-018-9822-0

- Graham, S., & Santangelo, T. (2014). Does spelling instruction make students better spellers, readers, and writers? A meta-analytic review. Reading and Writing, 27(9), 1703–1743. doi:10.1007/s11145-014-9517-0

- Hosp, M. K., & Hosp, J. L. (2003). Curriculum-based measurement for reading, spelling, and math: How to do it and why. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 48(1), 10–17.

- Jewell, J., & Malecki, C. K. (2005). The utility of CBM written language indices: An investigation of production-dependent, production-independent, and accurate-production scores. School Psychology Review, 34(1), 27–44. doi:10.1080/02796015.2005.12086273

- Johnson, D. J., & Grant, J. O. (1989). Written narratives of normal and learning disabled children. Annals of Dyslexia, 39, 140–158.

- Juel, C., Griffith, P. L., & Gough, P. B. (1986). Acquisition of literacy. A longitudinal study of children in first and second grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(4), 243–255. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.78.4.243

- Kent, S., Wanzek, J., Petscher, Y., Al Otaiba, S., & Kim, Y. S. (2014). Writing fluency and quality in kindergarten and first grade: The role of attention, reading, transcription, and oral language. Reading and Writing, 27(7), 1163–1188. doi:10.1007/s11145-013-9480-1

- Kent, S. C., & Wanzek, J. (2016). The relationship between component skills and writing quality and production across developmental levels: A meta-analysis of the last 25 years. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 570–601. doi:10.3102/0034654315619491

- Kim, Y. S., Al Otaiba, S., Folsom, J. S., Greulich, L., & Puranik, C. (2014). Evaluating the dimensionality of first-grade written composition. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57(1), 199–211. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0152)

- Kim, Y. S., Al Otaiba, S., Puranik, C., Folsom, J. S., Greulich, L., & Wagner, R. K. (2011). Componential skills of beginning writing: An exploratory study. Learning and Individual Differences, 21(5), 517–525. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2011.06.004

- Kim, Y. S., Al Otaiba, S., & Wanzek, J. (2015a). Kindergarten predictors of third grade writing. Learning and Individual Differences, 37(850), 27–37. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2014.11.009

- Kim, Y. S. G., Park, C., & Park, Y. (2015b). Dimensions of discourse level oral language skills and their relation to reading comprehension and written composition: An exploratory study. Reading and Writing, 28(5), 633–654. doi:10.1007/s11145-015-9542-7

- Kim, Y. S. G., & Schatschneider, C. (2017). Expanding the developmental models of writing: A direct and indirect effects model of developmental writing (DIEW). Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(1), 35–50. doi:10.1037/edu0000129

- Kirby, M. S., Spencer, T. D., & Chen, Y.-J. I. (2021). Oral narrative instruction improves kindergarten writing. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 0(0), 1–18. doi:10.1080/10573569.2021.1879696

- Lucero, A., & Uchikoshi, Y. (2019). Narrative assessments with first grade Spanish-English emergent bilinguals: Spontaneous versus retell. Narrative Inquiry, 29(1), 137–156. doi:10.1075/ni.18015.luc.Narrative

- Mackenzie, N., Scull, J., & Munsie, L. (2013). Analysing writing: The development of a tool for use in the early years of schooling. Issues in Educational Research, 23(3), 375–393.

- Malpique, A. A., Pino-Pasternak, D., & Roberto, M. S. (2020). Writing and reading performance in Year 1 Australian classrooms: Associations with handwriting automaticity and writing instruction. Reading and Writing, 33(3), 783–805. doi:10.1007/s11145-019-09994-z

- McKenna, M., Dedrick, R. F., & Goldstein, H. (2021). Development and initial validation of the Early Elementary Writing Rubric to inform instruction for kindergarten and first-grade students. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 47(4), 220–233. doi:10.1177/15345084211065977.

- McMaster, K. L., Du, X., & Pétursdéttir, A.-L. (2009). Technical features of curriculum-based measures for beginning writers. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(1), 41–60.doi:10.1177/0022219408326212

- Miller, J., Gillon, G., & Westerveld, M. (2017). Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT) (New Zealand/Australian Instructional Version 18). Middleton: SALT Software, LLC.

- Moats, L. (2009). Knowledge foundations for teaching reading and spelling. Reading and Writing, 22(4), 379–399.doi:10.1007/s11145-009-9162-1

- Moats, L. (2020). Teaching reading is rocket science: What expert teachers of reading should know and be able to do. Washington, DC: American Federation of Teachers. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/moats.pdf.

- Petersen, D. B., Mesquita, M. W., Spencer, T. D., & Waldron, J. (2020). Examining the effects of multitiered oral narrative language instruction on reading comprehension and writing: A feasibility study. Topics in Language Disorders, 40(4), E25–E39. doi:10.1097/TLD.0000000000000227

- Petersen, D. B., & Spencer, T. D. (2016). Narrative language measures. CUBED Assessment; Dynamics Group, LLC. http://www.languagedynamicsgroup.com.

- Petersen, D. B., Staskowski, M., Spencer, T. D., Foster, M. E., & Brough, M. P. (2022). The effects of a multitiered system of language support on kindergarten oral and written language: A large-scale randomized controlled trial. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 53(1), 44–68. doi:10.1044/2021_LSHSS-20-00162

- Piasta, S. B., Groom, L. J., Khan, K. S., Skibbe, L. E., & Bowles, R. P. (2018). Young children’s narrative skill: concurrent and predictive associations with emergent literacy and early word reading skills. Reading and Writing, 31(7), 1479–1498.doi:10.1007/s11145-018-9844-7

- Pinto, G., Tarchi, C., & Bigozzi, L. (2015). The relationship between oral and written narratives: A three-year longitudinal study of narrative cohesion, coherence, and structure. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12091.

- Pinto, G., Tarchi, C., & Bigozzi, L. (2016). Development in narrative competences from oral to written stories in five- to seven-year-old children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 36, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.12.001

- Powell-Smith, K. A., & Shinn, M. R. (2004). Administration and scoring of written expression curriculum-based measurement (WE-CBM) for use in general outcome measurement (pp. 1–65). Eden Prairie: Aimsweb.

- Puranik, C., Al Otaiba, S., Folsom Sidler, J., & Greulich, L. (2014). Exploring the amount and type of writing instruction during language arts instruction in kindergarten classrooms. Reading and Writing, 27(2), 213–236. doi:10.1007/s11145-013-9441-8

- Puranik, C., Duncan, M., Li, H., & Ying, G. (2020). Exploring the dimensionality of kindergarten written composition. Reading and Writing, 33(10), 2481–2510. doi:10.1007/s11145-020-10053-1

- Puranik, C. S., & Al Otaiba, S. (2012). Examining the contribution of handwriting and spelling to written expression in kindergarten children. Reading and Writing, 25(7), 1523–1546. doi:10.1007/s11145-011-9331-x

- Ray, K., Dally, K., & Lane, A. E. (2021). Impact of a co-taught handwriting intervention for kindergarten children in a school setting: A pilot, single cohort study. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 15(3), 244–264.doi:10.1080/19411243.2021.1975604.

- Reese, E., Suggate, S., Long, J., & Schaughency, E. (2010). Children’s oral narrative and reading skills in the first 3 years of reading instruction. Reading and Writing, 23(6), 627–644. doi:10.1007/s11145-009-9175-9

- SALT Software LLC. (2016). C-unit segmentation rules (pp. 1–5). http://saltsoftware.com/media/wysiwyg/tranaids/CunitSummary.pdf.

- Schaughency, E., Suggate, S., & Reese, E. (2017). Links between early oral narrative and decoding skills and later reading in a New Zealand sample. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 22(2), 109–132.doi:10.1080/19404158.2017.1399914

- Scott, A., Gillon, G., McNeill, B., & Gath, M. (2022). Impacting change in classroom literacy instruction: A further investigation of the Better Start Literacy Approach. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 57(1), 191–211. doi:10.1007/s40841-022-00251-6.

- Scull, J., Mackenzie, N. M., & Bowles, T. (2020). Assessing early writing: A six-factor model to inform assessment and teaching. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 19(2), 239–259. doi:10.1007/s10671-020-09257-7