ABSTRACT

This study aimed to explore the experiences of Australian-based hearing healthcare stakeholders' with using teleaudiology and their views on future teleaudiology uptake. Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with 23 stakeholders (six clients, 10 clinicians, three students, two academics, and two industry partners). Six themes were generated: (1) Barriers to and facilitators of teleaudiology uptake, (2) Advantages and challenges of using teleaudiology, (3) Additional considerations when using teleaudiology, (4) Teleaudiology education at university, (5) Recent development in improving teleaudiology uptake, and (6) Attitudinal changes in post-pandemic teleaudiology uptake. Poor digital literacy and positive support received from other stakeholders were found to be the biggest barrier and facilitator, respectively. Additional considerations including the type of service offered and clear communication strategies were highlighted. Students and academics noted inadequate teleaudiology education at university, mainly due to a lack of infrastructure and equipment. Recent encouragement from management and improvement in university infrastructure were reported. Most participants were optimistic about post-pandemic teleaudiology uptake and expressed increased willingness to use teleaudiology over time. Generally positive attitudes towards future teleaudiology uptake were observed. Gradually increasing collaborative effort was seen in improving teleaudiology uptake, yet certain challenges and barriers need to be addressed to further promote teleaudiology uptake in post-pandemic times.

Introduction

Teleaudiology is a branch of telehealth or telemedicine in which hearing healthcare services are delivered remotely by means of digital communication and information technology when the client and clinician are in different geographic locations (Audiology Australia, Citation2020). Hearing healthcare services can be delivered via teleaudiology in a synchronous mode in which communication and exchange of medical information occur in real time, in an asynchronous mode in which patient data are saved and sent to clinicians for review at another time, or in a hybrid mode consisting of both synchronous and asynchronous service delivery (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2022). Delivery of various types of hearing healthcare services to children and adults via teleaudiology, including hearing screening, diagnostic audiometric testing, and audiological rehabilitation, has been shown to be feasible, reliable, and effective (Kim, Jeon, Kim, & Shin, Citation2021; Saunders, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). The nature of service delivery via teleaudiology enables easier and more immediate access to hearing healthcare in remote and rural populations which are often underserved (Mealings et al., Citation2020; Swanepoel et al., Citation2010). Teleaudiology is also thought to be able to reduce loss to follow-up, service wait times, travel time, and costs while maintaining quality of care (D'Onofrio & Zeng, Citation2021; Gajarawala & Pelkowski, Citation2021).

Despite recognising the potential benefits of teleaudiology, its uptake was slow prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. An international survey revealed that only 16% of audiologists had teleaudiology experience (Eikelboom & Swanepoel, Citation2016). Yet, hearing healthcare clinicians generally viewed teleaudiology positively and were open to its use if adequate training was provided (Eikelboom & Swanepoel, Citation2016; Ravi, Gunjawate, Yerraguntla, & Driscoll, Citation2018). The low adoption rates were attributable to lack of suitable technology and infrastructure (Ravi et al., Citation2018), limited availability of trained clinicians (Ramkumar, Shankar, & Kumar, Citation2023), patient data confidentiality and privacy concerns (Bennett et al., Citation2022a; Ravi et al., Citation2018), licensure and reimbursement issues (Ramkumar et al., Citation2023; Ravi et al., Citation2018), and uncertainties about the reliability of remote audiometric testing (Bennett et al., Citation2022a). Moreover, some clinicians perceived teleaudiology as less suitable in certain contexts, for example conducting diagnostic assessments or fitting hearing aids for first-time clients and children (Singh, Pichora-Fuller, Malkowski, Boretzki, & Launer, Citation2014).

Since the onset of COVID-19 pandemic and the accompanying restrictions, there was a temporary surge in teleaudiology usage aimed at ensuring care continuity and sustaining businesses (Coco, Citation2020). An international survey of audiologists has shown an increase in teleaudiology uptake from 41% pre-pandemic to 62% during the pandemic, with expectation of further increase to 80% post-pandemic (Eikelboom et al., Citation2022). Similar trends were observed in country-specific surveys in the UK and Australia (Chong-White, Incerti, Poulos, & Tagudin, Citation2023; Saunders & Roughley, Citation2021). The surge in teleaudiology uptake during the pandemic might be largely attributable to exogenous pandemic-related factors, such as the prioritization of client and staff safety and the availability of funding for teleaudiology services, and as such it was suggested the surge might revert once the pandemic was over (Bennett et al., Citation2022b).

As the pandemic wanes, understanding the perspectives, motivation, and challenges of teleaudiology users becomes crucial for its future uptake. Previous studies predominantly explored perceptions of hearing healthcare clients and clinicians towards teleaudiology uptake with minimal emphasis on other stakeholder groups. This study aimed to holistically explore teleaudiology’s post-pandemic landscape by gathering insights from five groups of hearing healthcare stakeholders in Australia: clients, clinicians, students, academics, and industry partners. This study also sought to explore both barriers to and facilitators of teleaudiology uptake.

Materials and methods

The current study is an extension of a nationwide survey conducted in Australia from May to October 2022 (Mui, Muzaffar, Chen, Bidargaddi, & Shekhawat, Citation2023). Consenting survey respondents who were hearing healthcare stakeholders (e.g., clients, clinicians, students, academics, and industry partners) were invited to participate in a semi-structured interview. Due to the qualitative nature of the current study, the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, Citation2007) was employed to guide the reporting of various aspects of study design and data analysis (see Supplemental Material 1 for completed COREQ checklist).

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee before the commencement of data collection (Project ID: 2875).

Research team characteristics and relationship with participants

The first author (BM) conducted all of the 23 semi-structured interviews. BM had no prior experience in conducting semi-structured interviews but did undergo training provided by ML, who had extensive experience in conducting qualitative research, prior to commencement of this study. Relationships were established between BM and some participants prior to study commencement, e.g., clinicians whom BM knew through personal connections and students and academics from the same university where BM was undertaking his study. No prior relationship was otherwise established between BM and other participants. Prior to the interviews, participants were encouraged to express their opinions freely and none of their answers or feelings would be judged. Participants with established relationships with BM shared both positive and negative opinions regarding teleaudiology use and therefore, we believed social desirability bias was insignificant. Information about the purposes and design of this study was provided to the participants in an online participant information sheet and consent form.

Study design

Theoretical framework

Grounded theory was utilized in this study to derive theories from systematic analysis of the data in an inductive approach (Chun Tie, Birks, & Francis, Citation2019). Reflexive thematic analysis is a widely used analytic method in qualitative research which is useful in investigating the perspectives of different individuals on the topics of research interest as well as in identifying, describing, analysing, and reporting themes generated from a dataset (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019, Citation2021). For the purposes of gathering in-depth insights from multiple groups of hearing healthcare stakeholders in Australia on teleaudiology uptake without predetermined hypotheses, grounded theory and reflexive thematic analysis were selected to be the methodological orientation to underpin this study.

Interview guide development

Five interview guides were developed, with one for each stakeholder group (see Supplemental Materials 2–6 for the interview guides). The questions in the guides were crafted to explore stakeholders’ experiences with using teleaudiology, their views on its future uptake, and facilitators of and barriers to its uptake. The interview guides were reviewed by all authors to check for appropriate wording, coherence, and comprehensive coverage of the study objectives.

Participant selection

Participants were recruited from an existing study conducted from May to October 2022 (Mui et al., Citation2023). This study involved completion of a survey to understand the perspectives of hearing healthcare stakeholders in Australia, including clients, clinicians, students, academics, and industry partners, on teleaudiology uptake. In this context, industry partners are defined as those offering audiology products, training, and after-sales services to hearing healthcare providers. The industry partner participants in this study were responsible for the provision of teleaudiology products, training, and after-sales services to clinicians and clinics. Both users and non-users (e.g., clients with tinnitus who were eligible for but never used teleaudiology services) of teleaudiology were recruited in the above study. Survey respondents were recruited via social media and the professional networks of the first author (BM) and last author (GSS). All survey respondents answered a question at the end of the survey about their interest in participating in the current study. An email invitation with a link to the online participant information sheet and consent form were sent to the 154 consenting survey respondents. Out of the 154 individuals contacted, 23 (six clients, 10 clinicians, three students, two academics, and two industry partners) completed the consent form and interview. The invited individuals who did not complete the consent form did not provide reasons for their non-participation.

Setting

As the participants were geographically scattered across different states of Australia, all interviews were conducted online using Microsoft Teams. Each participant was provided a unique link to the online meeting room which was only available to the participant and interviewer (BM). No one else was present in the interviews.

Data collection

Interview guides were provided to the participants at least one week before the interview so they could familiarize themselves with the questions to be discussed. All interviews were video-recorded and automatically transcribed on Microsoft Teams. Field notes were also made by the interviewer during the interviews. Each interview took 12–36 minutes to complete (mean: 22 minutes). Interview transcripts were returned to participants for comment and correction, e.g., spelling corrections and removal of participant’s company name.

Data analysis and reporting

Verbatim interview transcripts were imported into the NVivo R1 software for data analysis. BM performed the initial coding following an inductive thematic analytic approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Interview transcripts were examined repeatedly to identify individual codes and similar codes were grouped into themes. A codebook consisting of codes, description of codes, example quotes, and frequency of codes in all transcripts was established. The codebook was reviewed by co-authors (ML and DT) to check interpretations and ensure appropriate categorization of codes into themes and to evaluate their relevance regarding study objectives. The codebook was modified by BM according to the feedback from ML and DT, which resulted in the removal of redundant codes and facilitated the identification of distinct themes. Participant quotes and ID numbers were included to elucidate the themes identified in this study.

Results

A total of 23 hearing healthcare stakeholders (six clients, 10 clinicians, three students, two academics, and two industry partners) were interviewed. Among the clinicians (N = 10), four had 1–5 years of work experience as a clinician, three had 6–10 years, two had 11–15 years, and one had more than 15 years. Six of the clinicians worked in large chain clinics (>20 clinics), three worked in independent clinics, and one worked in government hospital/clinic. The three students were from two universities and all of them were in their second year of study. The two academics were from two universities and they each had 1–5 years and 6–10 years of work experience as an academic. As for the two industry partners, they respectively had 1–5 years and 6–10 years of work experience as an industry partner.

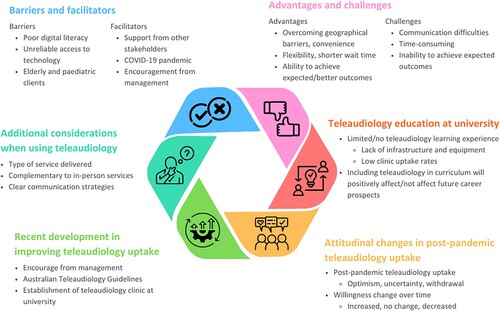

Overall, six themes were generated from the participant responses (see and Supplemental Materials 7–12).

Figure 1. Six themes generated from participant responses regarding their experiences with using teleaudiology and their views on future teleaudiology uptake.

Barriers to and facilitators of teleaudiology uptake

The five groups of hearing healthcare stakeholders (clients, clinicians, students, academics, and industry partners) suggested various barriers to and facilitators of teleaudiology uptake which could be categorized at individual, organizational, and technological levels. Supplemental Material 7 presents the barriers and facilitators suggested with example quotes from the participants. Barriers at individual level can be associated with clients, clinicians, other stakeholders, or a combination of the above. For example, the most mentioned barrier was poor digital literacy and confidence among clients and clinicians, as an industry partner suggested, ‘with people who are not familiar with teleaudiology, there’s lots of scepticism and fear from clinics who are not involved in teleaudiology’ (Participant 10). The other two most mentioned individual-level barriers were client age (elderly and paediatric), e.g., a clinician questioned the availability of research evidence on using teleaudiology in paediatric diagnostic testing, and poor personal connection as a client ‘would prefer in person, because people actually have a very healing quality in them’ (Participant 2). Little or lack of support from other stakeholders was also noted as a barrier, as a clinician explained:

Whenever I'm doing it with an assistant, sometimes it's perfect, but sometimes it can be a bit of like miscommunication between the audiologists and that front staff, and they might like to think that they can run the whole appointment (Participant 20).

At an organizational level, a perceived high cost of accessing teleaudiology services and difficulties in providing reimbursements could deter clients from using teleaudiology. An industry partner suggested that large hearing service providers appeared to be less accepting of teleaudiology uptake due to their more rigid business model, as

remote care is probably something that (bigger chains) would shy away from … because of the implementation of it and it being a bit more rigid in that type of sausage factory of retail, fitting of hearing devices and things like this … teleaudiology and remote care will be much more accepted in the independent space (Participant 22).

Similar to the barriers, facilitators of teleaudiology uptake can be categorized at individual, organizational, and technological levels. The most common facilitator was reported to be the support and training provided by other hearing healthcare stakeholders. For instance, clinical coaches, allied health assistants, and front of house staff played important roles in implementing and facilitating teleaudiology service delivery. The COVID-19 pandemic also prompted teleaudiology uptake for the purposes of minimizing in-person contact and health risks. Clients who had reached a later stage in their hearing care journey might find teleaudiology more useful, as a client explained: ‘(teleaudiology) could be really handy after you’ve done the initial testing and just sort of getting on that support journey’ (Participant 7). In addition, word of mouth, increased client awareness of hearing care, and high digital literacy among students were suggested as other individual-level facilitators.

At an organizational level, positive attitudes from the management level could promote teleaudiology uptake, e.g., a clinician mentioned that their organization was investing in a new department which would recruit clinicians to work completely remotely as teleaudiologists. Meanwhile, technology advancement were facilitators at the technological level, as previously clinicians ‘couldn’t do everything (via teleaudiology) but now they can basically do as much on the hearing aids as if the clients were sitting here right in front of them’ (Participant 15).

Advantages and challenges of using teleaudiology

Supplemental Material 8 displays the advantages and challenges of using teleaudiology suggested by the participants. Among the advantages identified, the ability to overcome geographical barriers, reduce travel needs and time, and increase convenience were the most mentioned. Overcoming the geographical limitations may work in both ways as clients residing in remote areas can more readily access hearing healthcare and clinicians who are located remotely ‘can actually provide services from their laptop at their home’ (Participant 20). Participants also found teleaudiology beneficial in terms of flexibility, reduced wait time, and immediate access to care, as explained by a clinician: ‘who doesn't love the fact that you can do all your medical consults and things from home when you want to squeeze it in while you're at work or whatever’ (Participant 8). Clinicians appreciated that expected health outcomes were able to be achieved or surpassed via teleaudiology. For example, a clinician was able to adjust a client’s hearing aids in real time based on the client’s home environment with the client at home. Other suggested advantages of using teleaudiology included unaffected rapport and trust when comparing to in-person services, comprehensive teleaudiology app functionality, use as an effective triage tool, increased revenue, easy provision of information for clients, and timely referral to other health professionals.

On the contrary, the use of teleaudiology was reported to create challenges which were otherwise not encountered in in-person service delivery. Oral communication via video calls could be difficult, as a client elaborated: ‘I misheard information and I found that there was a lag in the communication stream that tended to overlap questions and answers, and just generally did not feel comfortable’ (Participant 16). Teleaudiology appointments might also require more time for preparation and troubleshooting, e.g., a clinician had to ‘add on an extra 10–15 min, just to make sure we could all log in and everything was OK’ (Participant 15). The ability of certain teleaudiology products to achieve expected health outcomes was questioned. For instance, a client ‘used the tinnitus apps which haven't worked’ (Participant 3) and a clinician doubted the accuracy of self-administered hearing assessment software by saying ‘I know we've got like hearing test software that's recently starting to come out where you know the person can conduct their own hearing test. I don't think they're very accurate’ (Participant 12). Moreover, clinicians being unable to meet clients in person might hinder rapport and trust building. Interestingly, a clinician mentioned that their client who visited their physical clinic complimented on how big and clean the clinic was, and the clinician believed the visit facilitated trust building. Furthermore, the inability to check the placement of audiological testing equipment or hearing device, technological limitations before the COVID-19 pandemic, less client recognition of clinician’s work, and client’s uncertainty about clinician’s full attention during teleaudiology appointment were identified as other challenges of using teleaudiology.

Additional considerations when using teleaudiology

Prior to and during the use of teleaudiology, the participants noted several points as shown in Supplemental Material 9 which required attention and consideration for best service delivery. Firstly, clinicians might have preferences for the type of service delivered via teleaudiology, as a clinician suggested: ‘For audiology services (like) diagnostic test, it’s gonna be very hard to conduct online. But I think primarily, services that require counselling or even hearing aid tuning and aural rehabilitation, it’s very helpful to have it online’ (Participant 4). Secondly, teleaudiology should act as a complement to in-person services rather than a replacement and clients should be offered options of receiving services via either means or a combination of both. In order to tackle the communication difficulties in a videoconferencing appointment, clear communication strategies need to be in place, e.g., a clinician suggested ‘having clear instructions and something that is visual so that clients can follow through, like step-by-step guide’ (Participant 5). Moreover, emotional support and empathy should be shown as per standard in-person service delivery. One of the challenges of using teleaudiology as suggested by participants is rapport building, and a clinician suggested rapport building strategies such as reminding the client of the clinician’s experience and the purpose of the appointment, as well as the capability of conducting procedures with the support of an assistant on the client’s side.

Similar to having preferences for the type of service delivered via teleaudiology, clinicians also reported preferences for the mode of service delivery based on the type of service provided. For example, a clinician would opt for a video call for hearing aid check-ups as they would need to see the client’s home environment, how they manage the hearing aids, and to give visual instructions to the client. Furthermore, the importance of client privacy, confidentiality, and provision of person-centred care should never be overlooked when using teleaudiology. Both clients and clinicians noted that the clinicians conducting teleaudiology appointments should be equally qualified and professional as if the appointments were conducted in person. Some clinicians highlighted the significance of delivering teleaudiology services compliant with the government-funded Hearing Services Program (HSP) in order to maintain best practice and fulfil reimbursement requirements. Additionally, clinicians should be mindful of the time needed for conducting teleaudiology appointments, as in some circumstances extra time might be necessary to achieve planned outcomes with the same service quality. The ambient noise level on the client’s side is another consideration, especially when conducting remote hearing assessment.

Teleaudiology education at university

When being prompted to consider teaching and learning teleaudiology at university, students and academics expressed their opinions in multiple facets, as displayed in Supplemental Material 10. Initially, both students and academics thought teleaudiology education was inadequate or entirely lacking. Only a small number of lectures or subjects were allocated to introducing teleaudiology, according to a student and an academic. The two stakeholder groups attributed the lack of teleaudiology education to six factors: lack of infrastructure and equipment, low clinic uptake rates, importance of teleaudiology is not recognized, limited capacity of curriculum, difficulty in designing teleaudiology teaching, and generic accreditation standards.

As indicated by the students and an academic, some universities might not have a dedicated clinic with appropriate equipment where students could observe teleaudiology appointments and practice teleaudiology-related clinical skills. Low teleaudiology uptake rates among placement clinics further reduced students’ exposure to and perhaps confidence of teleaudiology use. A student conjectured that, maybe at the time when the curriculum was designed, teleaudiology was not as essential and therefore, did not receive much attention to be incorporated in the curriculum. An academic pointed out that the capacity of curriculum seemed merely sufficient to cover the basic topics, let alone additional topics such as teleaudiology. Besides, inclusion of teleaudiology in the curriculum is not a simple process, e.g., an academic believed that ‘it does take quite a bit of creativity to design useful workshops and practical assessment pieces’ (Participant 13). The generic accreditation standards set by Audiology Australia, the professional body in charge of postgraduate audiology programme accreditation in Australia, might have added complexity to defining and refining specific teleaudiology skills to be taught, as an academic explained:

it just gives university so much scope to do kind of what they think is best … so it’s maybe difficult to start out … and slower to get to a really polished part of the curriculum and really polished package for the students (Participant 13).

Recent development in improving teleaudiology uptake

Throughout the interviews, participants from each stakeholder group noted recent development in improving teleaudiology uptake in different areas of the audiology profession since the COVID-19 pandemic, as detailed in Supplemental Material 11. A monumental development occurred in Australia in 2022 when the Australian Teleaudiology Guidelines were introduced by Audiology Australia for the purpose of informing safe and effective teleaudiology service delivery (Audiology Australia, Citation2022). All of the 10 clinicians interviewed were aware of these guidelines, but only half of them had read the guidelines. For the clinicians who had read the guidelines, they expressed mixed feedback. Examples of negative feedback included the guidelines being not concise, practical, and elaborate enough, e.g., a clinician would like to know ‘what is expected of me and where the boundaries lie? What do I have to do to be HSP compliant?’ (Participant 15). Another clinician thought the guidelines did not add much value to their clinical practice because they were just outlining the teleaudiology work they had been doing. Meanwhile, two clinicians found the guidelines helpful in providing instructions on what to ask, do, and expect in a teleaudiology appointment, as well as acting as a reasonable framework for clinics to start using teleaudiology. For the clinicians who had not read the guidelines, they thought teleaudiology did not constitute a significant part of their work and so there was no need to read the guidelines, or they were simply too busy.

Apart from the introduction of the Australian Teleaudiology Guidelines, other development was observed recently across clinics and universities in the hope of facilitating teleaudiology uptake. Examples including hearing healthcare providers establishing departments dedicated solely to teleaudiology service delivery, universities setting up teleaudiology teaching clinics, and assessing students’ teleaudiology competencies as a requirement for programme completion have been mentioned earlier in Barriers to and facilitators of teleaudiology uptake and Teleaudiology education at university.

Attitudinal changes in post-pandemic teleaudiology uptake

As described in Supplemental Material 12, participants showed diverse responses when being asked about their feelings towards teleaudiology uptake over time and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In regard to post-pandemic teleaudiology uptake, all participants shared an optimistic attitude that people would potentially be more accepting of teleaudiology. A student believed that with gradually increasing awareness of hearing healthcare, potential clients would more likely recognize the need for audiology services and especially those who live in regional areas would most directly benefit from teleaudiology. Moreover, an academic observed an ongoing shift towards telehealth not only in the audiology profession but also in other medical and allied health professions, and the fact that some hearing healthcare stakeholders started exploring the feasibility of teleaudiology use during the pandemic would further encourage its continued use. Improvement in client digital literacy and confidence might be another reason behind the optimism about post-pandemic teleaudiology uptake, as an industry partner suggested: ‘As generations get older and they’re more comfortable with communicating through text and all that type of stuff, I think those types of services will just be rapidly continue to grow for sure’ (Participant 22).

Nonetheless, a clinician simultaneously expressed uncertainty due to their client population and work nature (paediatric diagnostic assessment), thinking that teleaudiology might have a place in their work, but they were unsure to what extent it could be used. In addition, it is noteworthy that an academic observed withdrawal from teleaudiology use after the pandemic, as some clinics which adopted teleaudiology during the pandemic ‘just used it as a stopgap measure rather than trying to create a really solid business and the plan and procedure to long term adoption of teleaudiology’ (Participant 13).

When participants were asked how their willingness to use/learn/teach teleaudiology changed over time, increased willingness was the most common response (N = 14), followed by unchanged willingness (N = 6), then decreased willingness (N = 3). In general, advancement in technology, the occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the popularization of internet communications underpinned participants’ increased willingness. For instance, as a client elaborated:

I think, particularly over the last two or three years when we’ve had to use a lot of Zoom, a lot of Teams, a lot of teleaudiology type of appointment, even with other medical professionals. Because we haven’t been able to go personally, I think that’s improved a lot of people’s skills and willingness to actually do it, because I think it’s sort of proved that it’s viable (Participant 7).

Discussion

The current study into teleaudiology use in Australian hearing healthcare stakeholders post-pandemic identified digital literacy, technological issues, and a preference for face-to-face services as key barriers to future uptake; echoing concerns in existing literature (Bennett & Campbell, Citation2021; Eikelboom & Swanepoel, Citation2016; Mui et al., Citation2023). Similarly, clinicians have reported teleaudiology as unsuitable for specific client populations and types of services, e.g., elderly clients and paediatric diagnostic assessment (Rashid, Quar, Chong, & Maamor, Citation2019; Singh et al., Citation2014).

Receiving little to no support from other stakeholders, such as clinicians or allied health assistants, was noted to be a barrier to teleaudiology uptake. In contrast, participants also shared positive experiences of receiving support from their fellow colleagues, which enabled the successful use of teleaudiology. Apart from the provider’s perspective, clients who need help with utilizing technology may also benefit from the assistance of a third party, such as their family members, parents, or caregivers, before and during a teleaudiology appointment. Having a facilitator on the client’s side during a teleaudiology appointment is not a rare practice, as indicated by a scoping review Coco, Davidson, and Marrone (Citation2020). There lies a caveat, nevertheless, that miscommunication between the clinician and assistant can potentially result in less favoured outcomes. For example, a clinician in this study described how their front of house staff took over the teleaudiology appointment and overstepped their duties. In order to maximize the benefits of a facilitator’s involvement, training should be provided to the facilitator beforehand on their duties and responsibilities, and the purposes and expectations of the appointment should be communicated clearly between the clinician and the facilitator. Reflective debriefing sessions may also be organized to discuss strengths to be upheld and weaknesses to be improved.

As an extension of a nationwide survey conducted in Australia in 2022 (Mui et al., Citation2023), participants in the current study reported some recent development in improving teleaudiology uptake which was not observed in the previous study, e.g., increased support from management in clinical and university settings. It is encouraging to know that the leadership team of certain hearing healthcare providers advocates teleaudiology use by investing in positions and departments dedicated to teleaudiology service delivery. This can be an indicator of the leadership team recognizing and acknowledging the feasibility and benefits of teleaudiology use, and a display of the hearing healthcare providers’ commitment to ensuring continuity of care and servicing to remote communities.

Commitment to teleaudiology in the university setting has also been observed. One university had established a teleaudiology clinic to be used for clinical and teaching purposes. This is an important investment as a lack of infrastructure has been noted in multiple studies as a barrier to teleaudiology uptake (Eikelboom & Swanepoel, Citation2016; Saunders & Roughley, Citation2021; Zaitoun, Alqudah, & Al Mohammad, Citation2022). Although the above studies explored barriers from clinicians’ point of view, it is rational to postulate that the same barrier applies to universities. Without suitable space, equipment, and personnel, teleaudiology education can be rendered restrictive, possibly merely at the level of theoretical knowledge transfer with no hands-on clinical experience. Acquisition of knowledge and experience through clinical practice is essential for students, not only to solidify their learning by interacting with real-life clients, but also to improve students’ confidence levels (Santella et al., Citation2020). Universities are the nurturing grounds for future clinicians. Increased opportunities for students to learn teleaudiology will likely improve their acceptance and willingness of using teleaudiology when they practice as clinicians. Same as any other topics in the curriculum, addition of teleaudiology to the curriculum requires meticulous planning and preparation. To name a few, staffing, funding, infrastructure, and teaching materials are some of the imperative considerations. Bringing changes to the university curriculum is never a simple and quick process, yet in an era where teleaudiology has been proven to be viable and advantageous, it may be worthwhile for universities to re-evaluate the importance of teleaudiology education and take the initiative in the joint effort of the accreditation organization (Audiology Australia) to be a key driver of teleaudiology uptake.

This study revealed generally positive attitudes towards teleaudiology uptake among hearing healthcare stakeholders in Australia. Towards the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, most participants indicated that their willingness to use teleaudiology over time increased, and they were optimistic about post-pandemic teleaudiology uptake. These findings echo those from previous studies reporting increased perceived importance of teleaudiology during the pandemic and increased motivation to use teleaudiology during and after the pandemic (Bennett et al., Citation2022a; Eikelboom et al., Citation2022; Saunders & Roughley, Citation2021). It is nonetheless notable that uncertainties around the accuracy and effectiveness of some types of teleaudiology services (e.g., diagnostic assessment) still exist and need to be addressed before teleaudiology is more widely accepted and used. As some of the participants in this study emphasized, teleaudiology is best considered as a complement rather than a replacement of in-person services. As with in-person service delivery, teleaudiology may not be a one-size-fits-all solution, but its capability and benefits certainly need more recognition for this option to be made available to a larger population. Teleaudiology will be here to stay beyond the pandemic, only if hearing healthcare stakeholders are willing to try to utilize it and the government provides continuous support (e.g., funding for reimbursement).

Limitations

The sample size of each stakeholder group was small (N = 23; six clients, 10 clinicians, three students, two academics, and two industry partners) despite all effort in participant recruitment. It is highly likely that underrepresentation of each stakeholder group exists, especially for students, academics, and industry partners. Due to the small sample size, generalization of findings to all hearing healthcare stakeholders in Australia remains difficult and our findings should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, as the lockdown measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, status of teleaudiology implementation, motivation for teleaudiology adoption (e.g., government funding), and the hearing healthcare system structure may vary greatly between Australia and other countries, it may not be appropriate to generalize the findings from this study to other countries. Additionally, the small number of responses collected from each stakeholder group rendered the determination of data saturation impossible. Lastly, self-selection bias might exist in this study, as individuals who were enthusiastic about teleaudiology might be more inclined to accept the invitation to participate in this study.

Future directions

For the aforementioned limitations to be addressed, qualitative studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further explore the views of different hearing healthcare stakeholders on teleaudiology uptake. Changes in the extent of teleaudiology uptake may also be continuously observed in the post-pandemic environment. Future studies at an international scale will be useful in delineating the differences in the landscape of teleaudiology uptake across countries, from which novel insights may be obtained to improve teleaudiology use. For example, strategies for improving teleaudiology uptake (e.g., strategic measures and policies implemented by hearing healthcare providers and governments) may be shared and referred to within and among countries. In addition, further investigation on the roles and effects of facilitators on the quality, satisfaction, and outcomes of teleaudiology consultations, as well as the significance and effectiveness of training provided to facilitators may be of interest.

Follow-up studies on teleaudiology education at universities may prove beneficial, especially with the recent developments in university infrastructure and curriculum modification at some universities. It will be interesting to discover whether universities that do not currently include teleaudiology in the curriculum will follow the steps of the universities that have, and the motivation and challenges behind such decisions. Besides, students’ willingness and confidence in using teleaudiology may be of particular interest, as these future clinicians may become strong advocates for teleaudiology use if they gain adequate relevant experiences during their study.

Supplemental_Material_1.docx

Download MS Word (24.9 KB)Supplemental_Material_3.docx

Download MS Word (26.2 KB)Supplemental_Material_5.docx

Download MS Word (24.1 KB)Supplemental_Material_4.docx

Download MS Word (24 KB)Supplemental_Material_7.docx

Download MS Word (24.1 KB)Supplemental_Material_6.docx

Download MS Word (24.3 KB)Supplemental_Material_9.docx

Download MS Word (18.9 KB)Supplemental_Material_2.docx

Download MS Word (25.6 KB)Supplemental_Material_8.docx

Download MS Word (20.4 KB)Supplemental_Material_11.docx

Download MS Word (19.1 KB)Supplemental_Material_12.docx

Download MS Word (19.8 KB)Supplemental_Material_10.docx

Download MS Word (20.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for sharing their invaluable opinions and ideas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2022). Telepractice. Retrieved 21 July from https://www.asha.org/practice-portal/professional-issues/telepractice/.

- Audiology Australia. (2020). Teleaudiology position statement. https://audiology.asn.au/Tenant/C0000013/AudA%20Position%20Statement%20Teleaudiology%202020%20Final(1).pdf.

- Audiology Australia. (2022). Australian teleaudiology guidelines. https://teleaudiologyguidelines.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Australian-Teleaudiology-Guidelines-2022.pdf.

- Bennett, R. J., & Campbell, E. (2021, December). THE 2020 NATIONAL TELEAUDIOLOGY SURVEY: Utilisation, experiences and perceptions of teleaudiology services during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic: An Australian perspective. Audiology Now, 86, 19–21.

- Bennett, R. J., Kelsall-Foreman, I., Barr, C., Campbell, E., Coles, T., Paton, M., & Vitkovic, J. (2022a). Barriers and facilitators to tele-audiology service delivery in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives of hearing healthcare clinicians. International Journal of Audiology, 62(12), 1145–1154. doi:10.1080/14992027.2022.2128446

- Bennett, R. J., Kelsall-Foreman, I., Barr, C., Campbell, E., Coles, T., Paton, M., & Vitkovic, J. (2022b). Utilisation of tele-audiology practices in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives of audiology clinic owners, managers and reception staff. International Journal of Audiology, 62(6), 571–578. doi:10.1080/14992027.2022.2056091

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Chong-White, N., Incerti, P., Poulos, M., & Tagudin, J. (2023). Exploring teleaudiology adoption, perceptions and challenges among audiologists before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Digital Health, 1(1), 1–11. doi:10.1186/s44247-023-00024-1

- Chun Tie, Y., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Medicine, 7, 1–8. doi:10.1177/2050312118822927

- Coco, L. (2020). Teleaudiology: Strategies, considerations during a crisis and beyond. The Hearing Journal, 73(5), 26–29. doi:10.1097/01.HJ.0000666404.42257.97

- Coco, L., Davidson, A., & Marrone, N. (2020). The role of patient-site facilitators in teleaudiology: A scoping review. American Journal of Audiology, 29(3), 661–675. doi:10.1044/2020_AJA-19-00070

- D'Onofrio, K. L., & Zeng, F.-G. (2021). Tele-audiology: Current state and future directions. Frontiers in Digital Health, 3, 1–11. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2021.788103

- Eikelboom, R. H., Bennett, R. J., Manchaiah, V., Parmar, B., Beukes, E. W., Rajasingam, S. L., & Swanepoel, D. W. (2022). International survey of audiologists during the COVID-19 pandemic: Use of and attitudes to telehealth. International Journal of Audiology, 61(4), 283–292. doi:10.1080/14992027.2021.1957160

- Eikelboom, R. H., & Swanepoel, D. W. (2016). International survey of audiologists’ attitudes toward telehealth. American Journal of Audiology, 25(3S), 295–298. doi:10.1044/2016_AJA-16-0004

- Gajarawala, S. N., & Pelkowski, J. N. (2021). Telehealth benefits and barriers. Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 17(2), 218–221. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.09.013

- Kim, J., Jeon, S., Kim, D., & Shin, Y. (2021). A review of contemporary teleaudiology: Literature review, technology, and considerations for practicing. Journal of Audiology & Otology, 25(1), 1–7. doi:10.7874/jao.2020.00500

- Mealings, K., Harkus, S., Flesher, B., Meyer, A., Chung, K., & Dillon, H. (2020). Detection of hearing problems in aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children: A comparison between clinician-administered and self-administrated hearing tests. International Journal of Audiology, 59(6), 455–463. doi:10.1080/14992027.2020.1718781

- Mui, B., Muzaffar, J., Chen, J., Bidargaddi, N., & Shekhawat, G. S. (2023). Hearing health care stakeholders’ perspectives on teleaudiology implementation: Lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic and pathways forward. American Journal of Audiology, 32(3), 560–573. doi:10.1044/2023_AJA-23-00001

- Ramkumar, V., Shankar, V., & Kumar, S. (2023). Implementation factors influencing the sustained provision of tele-audiology services: Insights from a combined methodology of scoping review and qualitative semistructured interviews. BMJ Open, 13(10), e075430–e075430. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-075430

- Rashid, M. F. N. B., Quar, T. K., Chong, F. Y., & Maamor, N. (2019). Are we ready for teleaudiology?: Data from Malaysia. Speech, Language and Hearing, 23(3), 146–157. doi:10.1080/2050571x.2019.1622827

- Ravi, R., Gunjawate, D. R., Yerraguntla, K., & Driscoll, C. (2018). Knowledge and perceptions of teleaudiology among audiologists: A systematic review. Journal of Audiology & Otology, 22(3), 120–127. doi:10.7874/jao.2017.00353

- Santella, M. E., Hagedorn, R. L., Wattick, R. A., Barr, M. L., Horacek, T. M., & Olfert, M. D. (2020). Learn first, practice second approach to increase health professionals’ nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 71(3), 370–377. doi:10.1080/09637486.2019.1661977

- Saunders, G. H. (2020a). Evaluating evidence-based telaudiology: Part 1 on hearing assessment. The Hearing Journal. Retrieved 26 October from https://journals.lww.com/thehearingjournal/blog/OnlineFirst/pages/post.aspx?PostID = 68

- Saunders, G. H. (2020b). Evaluating evidence-based teleaudiology: Part 2 on intervention & rehabilitation. The Hearing Journal. Retrieved 26 October from https://journals.lww.com/thehearingjournal/blog/onlinefirst/pages/post.aspx?PostID = 71

- Saunders, G. H., & Roughley, A. (2021). Audiology in the time of COVID-19: Practices and opinions of audiologists in the UK. International Journal of Audiology, 60(4), 255–262. doi:10.1080/14992027.2020.1814432

- Singh, G., Pichora-Fuller, M. K., Malkowski, M., Boretzki, M., & Launer, S. (2014). A survey of the attitudes of practitioners toward teleaudiology. International Journal of Audiology, 53(12), 850–860. doi:10.3109/14992027.2014.921736

- Swanepoel, D. W., Clark, J. L., Koekemoer, D., Hall, J. W., Krumm, M., Ferrari, D. V., … Barajas, J. J. (2010). Telehealth in audiology: The need and potential to reach underserved communities. International Journal of Audiology, 49(3), 195–202. doi:10.3109/14992020903470783

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Zaitoun, M., Alqudah, S., & Al Mohammad, H. (2022). Audiology practice during COVID-19 crisis in Jordan and Arab countries. International Journal of Audiology, 61(1), 21–28. doi:10.1080/14992027.2021.1897169