Abstract

With the continuous assertion of Eindhoven as a center of innovation, technology and, more specifically, smart systems, the proliferation of “smartness” across the city’s built environment continues to increase in both overt and tacit ways. Traces of such a proliferation of “smartness” appear dotted throughout the city in the form of cameras and sensors, without much disclosure regarding who owns them and what they are used for. As such, Eindhoven’s citizens are subjected to various data-collection systems and living-lab experiments without their knowledge or agreement, as well as without any idea of the potential consequences and implications. This visual essay uncovers some of the traces of “smartness” across Eindhoven to reflect on the pervasiveness of “smartness” not only as an abstract idea, but also as a way of life and, ultimately, question the normalization of its corresponding mass-surveillance regime.

Becoming Smart

The exact number of projects and data-collection initiatives operating within Eindhoven has been so difficult to ascertain that in 2018 one of the city’s Alderman, Staf Depla, drew the government’s attention to the lack of legislation on this field. This resulted in the city’s implementation of a (pilot) sensor registry with the intention to “provide clarity .. about what is being measured in Eindhoven and by whom.”Citation1 A year after its implementation, however, no public institution, living-lab or private company has completed the voluntary registry of their sensors in the city’s public database. All the while, Eindhoven’s streets have become ever more littered with sensors, cameras and other networked devices, enacting the so-called smartification of the city as well as subjecting its residents to a multitude of involuntary data-collection schemes.

The promotion of innovation, technology and, more specifically, smart systems has become an intrinsic part of Eindhoven’s image building in which the full range of the city’s economical, educational and cultural spectrum has been employed. Smartness, not as an abstract idea, but as a way of life, is also actively promoted in the city’s built environment. Ranging from Atlas, the recently completed main building on the campus of the Eindhoven University of Technology heralded as the “most sustainable education building in the world,” to projects under development that promise a smart future for the smart city that Eindhoven is to become.Citation2

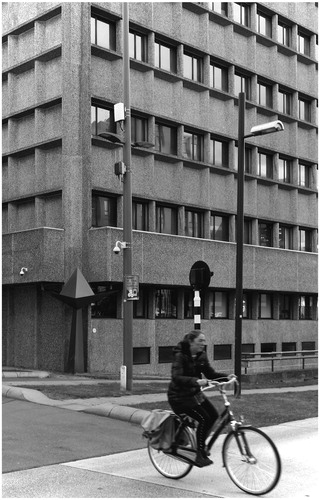

In preparation for that future, smartness has been forcefully deployed across Eindhoven’s urban fabric in the past few years, with its traces being materialized in various ways, from seemingly harmless license-plate recognition cameras accompanied by cheerful signs to an ever more cluttered amassment of sensors on lamp posts across the city’s center. Cloaked by an apparent transparency, certain areas of the city – such as the booming industrial-transformation area Strijp-S – provide public listings of the sensors present in their streets. These, however, are often incomplete, with several sensors being unaccounted for, while those that are accounted for being commonly merely identified without much (if any) information on which company or individuals are collecting and monitoring the data produced, nor how that data is stored or for what purposes it is used.Citation3

The ubiquity of smart systems in Eindhoven appears also in other, more inconspicuous ways, hiding behind layers of “infotainment” displayed on the sleek, futuristic-looking, CityBeacons. While the screens of these devices display advertisements and announcements for various events taking place in the city, concealed within them, an array of cameras and sensors continuously monitor the public space in which they are placed, tracking not only crowds but also individuals through the collection of the MAC-addresses of any smartphone within its range. Furthermore, the beacons are also outfitted with “selfie-cams” and actively invited passersby to take selfies and share their love for the city. The resulting “Eindhoven City Selfies” were automatically posted on a publicly accessible Flickr-account, thus effectively generating a free database of thousands of smiling faces complete with timestamps. Much to the dismay of city administrators, both the MAC-address tracker and selfie-cam had to be switched off once it became clear that those functions violated Dutch privacy laws, specifically the provision that forbids the collection and storage of such personal data without a “specific and pre-disclosed purpose.”Citation4 Nevertheless, the Flicker-account with over 72,000 selfies remains online and publicly accessible.

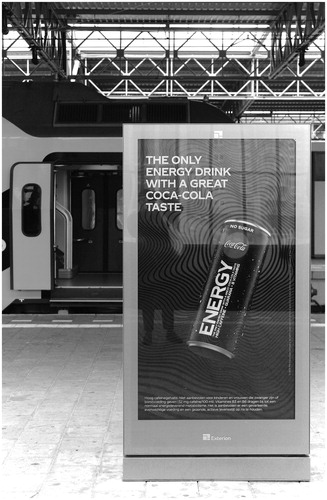

The surreptitious colonization of public space by smart systems was extended in Eindhoven (and beyond) through a network of digital advertisement screens placed in various Dutch train stations. While at first glance these appeared to be simple digital advertisement boards, it did not take long for commuters across the Netherlands to discover the cameras concealed within them. Besides displaying a continuous stream of ads, these boards were also equipped with cameras that recognized when someone looked at these devices’ screens, their gender and age, as well as how much time they spent looking at them.Citation5 Once this was revealed, a nationwide popular backlash ensued, resulting initially in the rebellious blocking off of the cameras with stickers, band-aids or chewing gum by random members of the Dutch citizenry. In response to the commotion, the corporation behind the advertising screens announced that the cameras had been turned off, subsequently covering up most cameras with a plaque with the company’s logo.

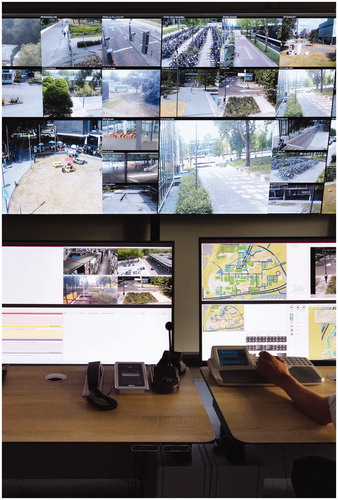

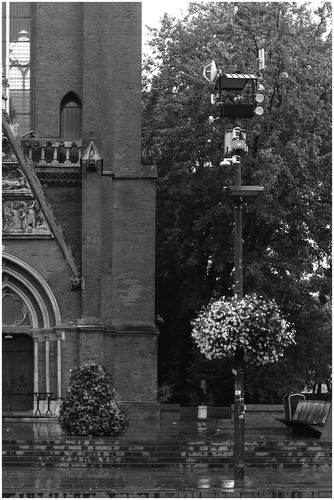

Conversely, the extensive presence of smartness in Eindhoven has also been employed in more active ways to influence people’s behavior. One such example comes in the form of bicycle-counting boards that register the amount of people cycling over a certain bicycle path and greet the passersby with encouraging messages, such as Good that you are cycling! and Do I see you again tomorrow?, stimulating people to keep up their cycling habits. Eindhoven is, however, more notorious for its attempts to influence behavior on its (in)famous bar street Stratumseind, which has become the most camera and sensor ridden area of Eindhoven in an effort to curb aggressive behavior and reduce the number of physical altercations. As part of one of the most famous urban living-labs, Stratumseind was outfitted with numerous Wi-Fi-trackers, cameras and microphones, intent on detecting aggressive behavior and, potentially instantly, alert police officers. Beyond an early-warning system, the living-lab project also intended to directly intervene in those occurrences. Thus, twenty-two lamp posts with adjustable light were installed in the street with the idea that the color and intensity of their light could influence people’s behavior, calming them or preventing tense situations. A few months after this experiment was initiated, it was abandoned, as the causality between human behavior and the adjustment of the light remained inconclusive. A new experiment ensued in which the spread of the smell of oranges was tested, again in an attempt to employ technology to thwart aggressive behavior.Citation6 All of these experiments, however, are taking place without notifying those who enter the area of their participation in a living-lab that is used “to profile, nudge or actively target people.”Citation7

Even though the advocates for these projects proclaim that rather than considering these developments as “Big Brother is Watching You” people should consider them as “Big Brother is Helping you,” these Minority Report type of developments should not be blindly heralded as great advancements as technologists and city marketers would like us to believe. Some citizens do realize this, such as Dave Borghuis, who in response to the employment of MAC-address tracking deployed in the Dutch city of Enschede filed a formal complaint against the municipality, stating that “if you walk around the city, you have to be able to imagine yourself unwatched.”Citation8

Although most data-collection and sensor distribution initiatives in Eindhoven claim to serve the greater good, it remains unclear what this greater good exactly is and who exactly it serves. Thus, these initiatives appear to be simple data-harvesting operations for the sake of data without any specific purpose. More worrisome still is that, as these projects occur in the physicality of public space, the only way to opt-out of participation is to opt-out of the city. By not going to Strijp-S, Stratumseind or any of Eindhoven’s other districts that have been colonized by living-labs, living in Eindhoven and using its public space becomes that much more restricted.

As such, with the already ubiquitous presence of sensors and cameras throughout our contemporary cityscapes, Borghuis’ desire seems like a nostalgic dream within the inescapable reality of constant surveillance: willingly or unwillingly, we are always being watched.

Figure 1 Billboard promoting the Eindhoven Edge project currently under development. © Justin Agyin, 2019. The Eindhoven Edge project is one of the many (high-rise) projects currently under development within the city aimed at reinforcing the image of Eindhoven’s Brainport and innovation district. The Eindhoven Edge is developed by Edge Technologies, a subsidiary of Dutch real estate developer OVG Real Estate specifically devised to develop buildings embedded with smart technologies as “the world needs better buildings,” according to the company slogan.

Figure 2 One of the main car entrances to the Strijp-S area. © Justin Agyin, 2019. Under the guise of improving mobility, all main entrances by car to the Strijp-S area have been outfitted with license-plate recognition cameras. With catchphrases as Smile! we capture your special moments. visitors are welcomed and notified that their license-plate has been registered. Despite this notification, it is impossible to opt out, since once the notification is readable, the license plate has already been registered.

Figure 3 Lamp post on the Strijp-S area containing several sensors. © Justin Agyin, 2019. With the increasing amalgamation of cameras and sensors in Eindhoven’s public space, lamp posts become ever more cluttered. This lamp post, for instance, features sensors that measure sound, air quality and the number of passersby. Naturally, these sensors are accompanied by a camera.

Figure 4 Pole with sensors in front of Saint Catherina Church in Eindhoven’s city center. © Justin Agyin, 2019. The ornate St. Catharina church proudly stands amid the predominantly modernist postwar building stock of Eindhoven’s city center. Positioned at the end of the city’s main shopping street, the lamp posts swarmed with various sensors and cameras facing the church already indicate its proximity to the main bar street Stratumseind.

Figure 5 CityBeacon in Eindhoven’s city center. © Justin Agyin, 2019. The slick, smartphone-like CityBeacon adorns various streets of Eindhoven’s city center, continuously watching. While the selfie-camera and MAC-address reader are currently disabled, developers of the CityBeacon and similar smart technologies are merely waiting for privacy legislation to become less restrictive to re-activate them.

Figure 6 Digital advertisement board on one of the platforms of Eindhoven Station. © Justin Agyin, 2019. With an increasing drive toward cyber-physical experiences developers of smart technologies employ various tools to achieve just that. The infamous digital advertisement screens located at various train stations in the Netherlands could potentially just do so. With the ability to estimate onlookers gender, age, and interest, these screens could actively target passersby, effectively mimicking online advertising tracking experience to the physical world.

Figure 7 Information board counting bicycles at the entrance of the Eindhoven University of Technology campus. © Justin Agyin, 2019. Bicycle counting information boards at the entrances to the campus of the Eindhoven University of Technology greet passersby with encouraging messages such as “Good that you are cycling. Naturally, as most sensor nodes, beyond counting the number of cyclists, other conditions are also continuously measured and recorded. In this case, temperature and air quality.

Figure 8 Pole with MAC adressess-trackers, cameras, microphones and the famed adjustable lights on Eindhoven’s Stratumseind. © Justin Agyin, 2019. As part of the Stratumseind living lab, twenty-two black boxes with three strips of LEDs have been distributed over its bar street. The light could be adjusted from a central control room, located in the nearby former courthouse. In addition, the data from the Wi-Fi-trackers, cameras and microphones embedded in these boxes can also be monitored and analyzed in real-time from that control room.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sergio M. Figueiredo

Sergio M. Figueiredo is an architect, author, curator and historian. He is an Assistant Professor of Architecture History and Theory at TU Eindhoven, where he founded the Curatorial Research Collective (CRC), a fledgling curatorial and research group. He is also the chair and head curator for CASA Vertigo, the exhibition department of TU Eindhoven’s Department of the Built Environment. Having contributed to several publications and conferences, his work focuses on architectural institutions and exhibitions, particularly how they shape (and are shaped by) architectural culture. His first book, The NAi Effect: Creating Architecture Culture, was published in 2016 by nai010 publishers.

Justin Agyin

Justin Agyin is an architect, curator and research and teaching assistant at the chair of Urbanism and Urban Architecture at TU Eindhoven. He has previously been involved with the chair of Smart Architectural Technologies at TU/e’s Department of the Built Environment and has co-curated and produced several exhibitions for the department’s exhibition committee CASA Vertigo. In addition, he has been Commissioner of Public Relations as board member of AnArchi, student-association for Architecture and has been editor-in-chief for the built environment magazine Chepos and the architecture journal Archiprint. He is currently assistant-curator at Eindhoven-based gallery and publisher Onomatopee Projects.

Notes

1 Hans Vermeeren, “Databank met alle Sensoren op één Plek in Eindhoven,” Eindhoven Dagblad, August 18, 2018, https://www.ed.nl/eindhoven/databank-met-alle-sensoren-op-een-plek-in-eindhoven∼a08fbf87/.

2 “BREEAM Hails Atlas the World’s Most Sustainable Education Building,” Cursor, April 16, 2019.

3 Strijp-S, “Living Lab Strijp-S,” http://strijps.nl/nl/living-lab-strijp-s (accessed September 20, 2019).

4 Michel Theeuwen, “Citybeacons Eindhoven op Zwart door Failliet Bedrijf,” Eindhovens Dagblad, October 18, 2018; “Smart Society Eindhoven: Endless Options for the Citybeacons,” Innovation Origins (blog), December 29, 2017, https://innovationorigins.com/smart-society-eindhoven-endless-options-citybeacons/.

5 Laurence Verhagen, “Camera’s in Reclamezuilen? Dat Mag Niet Zomaar,” De Volkskrant, June 26, 2018.

6 Diede Hoekstra, “Netwerk van Hypermoderne Camera’s Op Stratumseind in Eindhoven Gaat Politie Helpen,” Eindhovens Dagblad, December 11, 2017.

7 Saskia Naafs, “‘Living Laboratories’: The Dutch Cities Amassing Data on Oblivious Residents,” The Guardian, March 1, 2018, sec. Cities.

8 Ibid.

References

- 2019. “BREEAM Hails Atlas the World’s Most Sustainable Education Building.” Cursor, April 16.

- Hoekstra, Diede. 2017. “Netwerk van Hypermoderne Camera’s Op Stratumseind in Eindhoven Gaat Politie Helpen.” Eindhovens Dagblad, December 11.

- Naafs, Saskia. 2018. “‘Living Laboratories’: The Dutch Cities Amassing Data on Oblivious Residents.” The Guardian, March 1, sec. Cities.

- Strijp-S. “Living Lab Strijp-S.” http://strijps.nl/nl/living-lab-strijp-s.

- Theeuwen, Michel. 2017. “Smart Society Eindhoven: Endless Options for the Citybeacons.” Innovation Origins (blog), December 29. https://innovationorigins.com/smart-society-eindhoven-endless-options-citybeacons/.

- Theeuwen, Michel. 2018. “Citybeacons Eindhoven op Zwart door Failliet Bedrijf.” Eindhovens Dagblad, October 18.

- Verhagen, Laurence. 2018. “Camera’s in Reclamezuilen? Dat Mag Niet Zomaar.” De Volkskrant, June 26.

- Vermeeren, Hans. 2018. “Databank met alle Sensoren op één Plek in Eindhoven.” Eindhoven Dagblad, August 18. https://www.ed.nl/eindhoven/databank-met-alle-sensoren-op-een-plek-in-eindhoven∼a08fbf87/.