Abstract

What happens if architectural knowledge is not mediated through drawing or does not produce any type of record? How can an architectural archive exist and make sense in a context where the circulation of knowledge and the emergence of spatialities leave no physical traces? This essay offers insights into the traces left by undrawn spatialities and how they could be recorded and interpreted in architectural archives based on observations on the history of the Sahrawi refugee camps in archiving oral memories in collaboration with the Sahrawi Ministry of Culture. A project was launched to archive and maintain nomadic knowledge circulation that has been short-circuited by protracted immobilization. This essay proposes that gestures, words and bodies- as producers of undrawn architecture -allow other regimes and traces of spatialities to emerge.

Introduction

Entering the archive of the Ministry of Information of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic in Rabuni, the capital of the Sahrawi population in exile, I was impressed by the number of documents. Around a corridor, I found a room for the digitization of audio and video material, a small office for the director, and a storage room for the audio and video material. There is also a little room, called the library, with journals from the national periodic, Jeune Afrique, and other publications. In this room, a set of books written on a wide range of topics concerning the Sahrawi history, the war, and Western Sahara geography is stored. “Everything you want to learn about the Sahrawis is here,” said Lahsen Selki Sidi Buna, my host and collaborator on the Oral Memory archiving project. On the right side of the corridor, there is a room used as an archive of the journals that include articles on the Sahrawis and the conflict with Morocco from 1976 to the present.

Lahsen and I worked on the memories and histories of the refugee camps (1975–1991), from an architectural perspective. During this period, women were alone organizing and building the camps and the state. This archival fund has proven difficult to interpret, and without context or captions, the documents were cryptic. No drawings or plans ever existed to organize the camps, and no maps to coordinate them. Furthermore, most of the camp’s spatialities disappeared. The climatic and political conditions obliged the Sahrawi to move several times and reconstruct the camps each time in a new location. For all these reasons, the reading and understanding of the archives documents did not help provide a reliable image of the camps over time.

Minutes later, we went to Mohamed Ali Laman’s office, the person responsible for Oral Memory in the Sahrawi Ministry of Culture. He launched this project at the beginning of 2010. He observed a short-circuiting of the circulation of oral knowledge and memory in the new generations due to the protracted immobilization and the impossibility of maintaining a nomadic life. This knowledge is essential to the Sahrawi people, as it constitutes a decisive element for returning to their land and legitimizing their centennial culture. In his office, which was kept dark to keep the temperature down, there was a desk, a computer, and a hard disk. When Mohamed Ali inserted the hard disk into his computer, I found a series of audio and video interviews documenting discussions with elderly people in the refugee camp. I then realized I was there to continue to develop this work in the following months. When navigating through the materials of this archive of Oral Memories, I understood that these were the most relevant architectural documents I would find during my stay.

In this article, I question how could archives incorporate records and traces of architectural knowledge and culture unmediated through architectural drawings, notebooks, models, or other working documents? How can an architectural archive exist and make sense in a cultural context in which the circulation of knowledge and the emergence of spatialities leave no traces to be recorded under the Western epistemic frame of reference?Footnote1

These questions have been addressed by cultural mapping, which UNESCO acknowledges as “a crucial tool and technique in preserving the world’s intangible and tangible cultural assets.”Footnote2 Equally, numerous artists and scholars address the refugees’ and migrants’ conditions and the limits of conventional representation in grasping their memories and the traces of settlement and movements.Footnote3 Nevertheless, their work remains disregarded in the Western architectural archives. This article offers insights into the traces left by undrawn spatialities and how they could be recorded and interpreted in architectural archives based on observations on the Sahrawi camps’ history.

Firstly, the interpretation and analysis of architectural drawing, based on the writings of Robin Evans (1944–1993), will be introduced. Moving from an understanding of architectural space as the object of architectural history to a performative and embodied approach of architectural spatiality, I will engage with architectural images based on enacted gestures that remain undrawn or unbuilt. I then analyze the traces left by these undrawn spatialities, considering why and how their discussion fosters architectural knowledge diversification in archives. I will finally ground this epistemic frame through an analysis of the refugee camps’ histories, focusing on the memories of three architectural events, which I observed during a stay in 2020, to understand the traces left by these spatialities, how they can be recorded, and how they constitute architectural images of the socio-spatial transformation of the Sahrawi society in exile.

Architectural matter(s): potent and latent gestures and words

In “Translations from Drawing to Building,” Evans outlined opposite architectural practices. Firstly, there is one that ends “up working on the thing itself,” “emphasizing the corporeal properties of things made;”Footnote4 this entails a making based on direct action and engagement with physical matter. Secondly, design can be mediated through drawing by “disengagement, obliqueness, abstraction, mediation and action at a distance.”Footnote5 While mediated by drawings, the architectural image is transposed on a transcendental plane, exterior and agential – the drawing’s role is to represent this image, to fix it on paper. Conversely, an unmediated architectural image belongs to the nonrepresentational and the non-exclusively visual – such haptic images emerge through performed practices.

Architectural drawings can be collected, stored and retrieved, protected from weather and time, documenting the evolution of their uses and appropriations. Archives do not need to store buildings, even though it happens exceptionally.Footnote6 Nevertheless, the architectural drawing is not simply a representation; it is part of the world and its materiality, physical and virtual, as it enacts a field of potentialities.

In the article “In Front of Lines That Leave Nothing Behind,” Evans writes about Daniel Libeskind’s Chamber Works series (1983)Footnote7 and the existence of another kind of lines in architectural drawings. He wrote: “we must look in front for the things that the drawing might suggest, might lead to, might provoke; in short for what is potent in them rather than what is latent.”Footnote8 Evans saw a possibility for architecture to move back “from building to drawing […] [to] split into prior and subsequent activities: design and construction.”Footnote9 This architectural practice maintains the dichotomy between drawing and building but liberates it from its dependence on construction. Drawings become autonomous architectural works, acting in the world directly for what they can do – not for what they represent – “allow[ing] for the construction of lines in the sky.”Footnote10

In this definition, the spatialities are emergent and brought into being by a drawing understood not as a representation of a future state but as an active agent in the world and a producer of potentialities. Extending this consideration, I argue that gestures and speaking should be considered decisive records for architectural archives, not unlike drawing or other disciplinary media, as they can play the same agential role in the enactment of spatiality. From this position, the content of the architectural archive finds itself challenged in two ways. First, the gaze would reenact the agency of the records and the potentialities they afforded. Then, archives would become a place of imagination,Footnote11 and of critical understanding of the potentiality of transformative gestures,Footnote12 shedding light on an underestimated dimension in the architectural archives: spatialities that remain unbuilt and undrawn. To consider these realities of architectural experience and to archive them requires shifting from the historical linearity of the architectural space to the body-to-body migration of architectural spatiality.

From architectural space to architectural spatiality

The concept of “minor architecture” articulates that architecture and architectural technicity exist before the so-called “architectural.”Footnote13 Organizing spaces and times is a potentiality of the body negotiating and inventing its environment,Footnote14 individuating its milieu. This co-individuation of the milieu and the individual is the proposition of Gilbert Simondon (1924–1989) concerning the physical, biological, and psychosocial individuation of the technical being.Footnote15 In this view, the architectural space is a life form, not necessarily mediated through the kind of drawing described by Evans. It belongs to trace and gesture. I contend that the way two bodies are seated, one in front of the other, implies cultural situatedness, a fundamental part of spatial and architectural culture. Nevertheless, this definition of architectural technicity engenders a historiographical paradox in the way we inherit or transmit architecture – not only through the linearity of heritage but also in the regimes of the “migration of gestures,”Footnote16 and in the way we archive and construct architectural histories through a relentless and unforgiving standardization of architectural documents and records.

Facing this epistemic dead end, cultural geographers Nicky Gregson and Gillian Rose searched for another epistemology and shifted from the concept of space to that of spatiality. Taking the theory of performativity elsewhere, Gregson and Rose suggested that:

performances do not take place in already existing locations […], waiting in some sense to be mapped out by performances; rather, specific performances bring these spaces into being.Footnote17

Performance is a “situated convergence of human and nonhuman elements and force relations through which people, places, and things emerge or become.”Footnote18 It is a reenactment of socio-spatial norms through citational practices.Footnote19 Everyday spatialities are performed and maintained through iterative gestures that ground their meanings through an architectural assemblage of bodily, physical, and virtual materiality. The spatial knowledge on which these performative reenactments rely is a particular texture of architectural images that we call figurations. These figurations embody tacit knowledge hinging between the cognitive and the physical, deeply rooted in a cultural context as a technico-gestural knowledge.

Suppose architecture is brought into being by the rhythmic organization of space and time by embodied re-con-figuration. In that case,Footnote20 this phenomenon is more straightforward than the architectural event we are used to and remains unmediated through representational drawings. In this sense, spatialities are formed through an encounter of physical reality and a set of virtual potentialities. Space does not exist as a separate entity on which the architect and the geographer work. Under this premise, the architectural event shifts from the invention of new spaces to new gestures and spatialities.

This architectural event is enacted by figurations, as a particular kind of architectural knowledge and image that is not only visual but also haptic.Footnote21 The specific texture of the architectural knowledge and image is made of habits, gestures, bodies, and minor inventions defined by the emergence of new driving forces.Footnote22 To understand the transformation of architectural spatialities as situated performances, we have to follow their genesis from everyday gestures to transformative gestures through a body-to-body transmission. The historicity of these spatialities “differs from other types of traces in that it requires physical embodiment, the support of a human body.”Footnote23 As a category of architectural spatialities, the undrawn requires investigations on other regimes of traces, both to address its temporalities, embodiment, and migration, constituting its system of transmission, from one body to the other.

As gestures or words, the architectural drawing enacts or prepares new spatialities to come, as an embodied practice of imagination and reconfiguration. But if these undrawn spatialities are a matter of architectural history, what are the documents or records of these new threads? What is left of them that could become the content of an archive of spatiality?

Traces of the undrawn

The key question is why address architecture and archives within this frame of performative spatialities and figurations? Why is the undrawn as a category relevant for historiography?

While the destruction of worlds based on colonial pursuits has been widely debated,Footnote24 the decolonization of the archives, mainly the colonial archives that misrepresented, looted the objects of, and produced epistemic violence on colonized populations, is still to be accomplished.Footnote25 Within the almost-thirty-year-old archival turn, archives moved from archives-as-source to archives-as-subject – a field of ethnographic investigation.Footnote26

As Ann Laura Stoler suggested, “[D]istinguishing the archival power lodged in moments of creation from practices of assembly, retrieval, and disciplinary legitimation,”Footnote27 research unveils the “processes of production, relations of power in which archives are created, sequestered, and rearranged.”Footnote28 Architectural archives are still in need of such inquiries to disentangle power relationships. In this sense, the high degree of standardization of the documents hides, devalues, and silences many forms of circulation and conservation of architectural knowledge, notably organic forms,Footnote29 enacting what has been called an “epistemicide,”Footnote30 and instituting a male Western gaze on architectural history. A myriad of ways of engaging with architectural and spatial knowledge exists, and it is our responsibility to acknowledge them and give ground to reparation.

Architectural scholar Janina Gosseye stated that “over the past half-century, architectural historiography has been punctuated by attempts to break the silence, to tell alternative narratives and to include other voices.”Footnote31 The bourgeois classification and opposition between the building and the original architectural object presented in experts’ documents are criticized for the underlying idealism and incapacity to foresee the majority of the protagonists in a building’s conception and life.Footnote32 As one of the categories that could mediate potential (hi)stories, the undrawn aims at addressing standardization and silencing in giving accounts of other regimes of traces and circulation of knowledge. In endorsing the performative dimensions of spatialities and the embodied nature of figurations – as an attempt to dismount imperialist views on architectural knowledge and image – the undrawn allows us to think of new ways of engaging with architectural archival practices; it permits us to ground a debate on the content of the architectural archives, beyond the analysis of the actual content, and the potential opening to other traces of spatialities and potent materialities. I propose here the recording of three series of traces that remained outside of the architectural archives’ scope, and that could be brought to the fore by using new and old archival technologies.

I begin this non-exhaustive enumeration with the relation between spatialities, bodies, and reenactments. The body-as-archive has been extensively explored.Footnote33 Performance and dance theory discussed reenactment as a will-to-archive. Curator André Lepecki stated that in some “reenactments, there will be no distinctions left between archive and body.”Footnote34 In a performative perspective, physical space and gestures are actors of the reenactment of a spatiality. As such, the embodied knowledge that is figured through reenactment is an architectural record.

Cinematographic, journalistic, or vernacular videography remains the most accessible record from the viewpoint of the technicality of reenactments. Filmmaker Harun Farocki interrogated the cinematographic archive, questioning how it allows non-lexical indexing of the content based on gestures and bodies.Footnote35 Other archiving approaches to migration use film to address the complexity of the temporalities, spatialities, geographies, and memories.Footnote36 Vernacular photography has also been studied in relation to the visual and as a source of knowledge.Footnote37 Considered as an event engaging agents with a camera, photography sometimes results in images that allow the performative dimensions to be analyzed as part of a scene where every individual act sheds light. By meticulously studying the events and their spatialities, vernacular photographs become a rich source of information for architectural histories.

Finally, as one of the primary means of transmitting knowledge, oral memory has been addressed as a source of epistemic diversity in the construction of archives.Footnote38 The electronic and digital records are marked by the “return to conceptual orality,”Footnote39 which is at the core of our concerns through the lens of the interview and the archive’s community-based construction.Footnote40 In a context where spatialities remain undrawn, unbuilt, or ephemeral, oral memories constitute one of the most reliable architectural traces for understanding one’s relation to space and its evolution in time.

These materialities constitute a corpus of traces that could record spatiality and bring light to undrawn spatialities. They place the architectural researcher (and archivist) in the role of an ethnographer. However, these questions did not emerge out of nowhere. In this frame, through research granted by the Swiss National Fund, in collaboration with the University of Tifariti in the refugee camp of Smara, with the Ministry of Culture of the Sahrawi State, and with the Autonomous University of Madrid, I had the chance to be part of an archiving project of Oral Memories. Collectively, we aimed at addressing the history and memories of one of the oldest refugee camps in the world, focusing on the sociocultural transformation of the Sahrawi society through exile.

Spatialities and historicity of the Sahrawi refugee camps

Nowadays, extensive literature exists on the Sahrawi’s political and armed struggle against the Moroccan occupation from a political science perspective,Footnote41 offering a counter-historical account.Footnote42 Some anthropologists studied the Sahrawi society and the identity transformations through the revolution;Footnote43 the actual camps had been analyzed from an urbanistic perspective.Footnote44 Nevertheless, the memories and history of the refugee camps had not been addressed. From the Hamada’s desert (high plateau), the Sahrawis, in the majority women, outlined and performed the spatiality of the camps and participated in a nation-state effort to govern them.Footnote45

The refugee camps history is much more complex than just settling the population in one place and organizing the infrastructure’s cumulative and linear growth. The refugees moved several times to find water and branches or because of floods and safety issues. Consequently, almost all of these camps and their spatialities disappeared. The harshness of the climate coupled with the lightness of built installations left nearly no physical traces behind. Thus, emerged the questions of the traces of the undrawn: the prolonged immobilization of the Sahrawis short-circuited the traditional systems of knowledge circulation, stressing the urgent necessity to archive the memories and knowledge of these women. The memories of the refugee camp spatialities are expressed in various ways, from the movement of hands to ways of seating. The sociocultural revolution that they went through was expressed and actualized through the new spatialities and gestures they invented, grounded on traditional and embodied knowledge, new ideals of radical equality, and the lost territories’ reenactments.

These gestures and spatialities were not enacted through or translated into archivable documents. In the Ministry of Information archives one can find only some photographs, anonymous and without captions. There are no drawings or plans. Only administrative documents and official discourses can provide testimony for this period. If these spatialities embody a common affect and knowledge, a (non-visual) architectural image and its performative reenactment, how can we imagine archiving them without losing their embodied qualities while translating them into a latent drawing? How can one include in the archival project the body-to-body history of the transformations of the Sahrawi spatialities? Some insights emerge from the discussions with elderly women, sketching ideas toward constructing an archive of architectural spatialities.

The Lezl refuge

Surrounded by her family members, Aguaila was seated on a carpet in front of the sand-brick wall of her Jaïma, enjoying the sunset. Like many older people who spent most of their lives in the refugee camps, her eyes are surrounded by a white halo, progressively losing sight because of the sun’s light intensity. Aguaila is a public figure in the barrio 3 (neighborhood) of Hausa’s daïra in Smara; as a traditional medicine specialist, she is consulted to treat every health trouble. She was holding two large needles in her hand, passing them again and again through the stitch of the carpet, in synchronicity with the rhythms of her sentences. During her childhood and youth, she lived as a pastoralist in the northeast of Western Sahara; she did not go to the Spanish schools and did not learn how to read or write. Instead, she cultivated the bottomless memory of the Sahrawis and the knowledge of medicinal plants and natural medicines. Thus, the way she described the Saharan desert was dense in information and details enhanced by her gestures and body’s position while she was talking.

We mainly discussed her exodus in the camps with her children. When the Moroccan army entered the Sahrawi territories on October 31, 1975, Aguaila was in Jdeiriya, a village at the northern border. When the Spanish army left silently, the Sahrawi population was alerted by the dust lifted by their cars. The people, including Aguaila and her children, fled to join the Polisario Front and protect themselves from the Moroccan army. Over four months, two-hundred people moved from one water well to another without any equipment to survive before reaching the first refugee camp at the Algerian border. While narrating the exodus, Aguaila named each Ouad (river), dates of arrivals and departures, describing the vegetation and the climatic conditions.

After staying hidden for a few days near Jdeiriya, where she was born, they went on the road to Smara to the water well called M’Jbeiriya, on the Ouad R’ni, a tributary of the Saguiat el Hamra. The sand accumulates at the feet of Lezl trees growing in the river bed;Footnote46 the more significant the heap, the higher the tree grows, while branches are absorbed in the sand. Aguaila imitated the plant’s growth and the sand accumulation using her hands and arms to explain this process. In times of trouble, the Sahrawis dig at the feet of trees to create shelter from the heat of the day and protect themselves from the coldness of the night. She reenacted the wood structure with her gestures, which permitted her to create invisible, temperate, and safe spaces to sleep and spend the days protected. Aguaila and the women dug holes into the sand for several days and nights to protect their children. She bent her back, tilting her whole body onward; she explained that to warm up their babies, the women hollowed the ground out to use its heat, transforming their bent bodies into blankets. She reenacted figurations anchored in her body, carrying with her a timeless co-shaping of desert spatialities and the Sahrawis’ gestures. The movements of her hands and her body’s posture, forming gestural drawings that leave no lasting traces, are the means of circulation and conservation of an architectural knowledge that cannot be standardized into a document but is remembered by the archive of her body.

The bricks of the National Hospital

Another kind of trace is left by the national hospital built from 1976 to 1978 between the Smara and Awserd camps. Most of the information shared here emerges from a discussion with Souilma Beiruk, the representative of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) at the African Union. The hospital was the first building made by the Sahrawi women in the refugee camps. The situation when they arrived at the camp was critical. People were sleeping outside, without blankets. Several diseases spread throughout the population while the open war against the Moroccan army was raging. The few tents they received from the international support were not enough to host all the armed people.

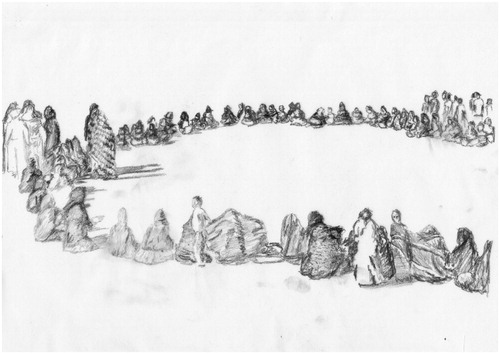

Women were highly organized; cells of nine to twelve people were the basic political unit through which information spread and the political decisions were made. Along with the political cells, women were organized in committees in charge of health, education, social assistance, justice, and craftwomanship. At night, when the children were sleeping, around 11 p.m., they would meet and sit in circles, as was their custom, to discuss for hours how to ameliorate the camp’s living conditions ().

Figure 1 Photograph redrawn by the author from the Archives of the Ministry of Information of the SADR. Morning meeting in the refugee camps (probably Rabuni) in 1976. Source: Manfred O Hinz, “3WM Interview mit Gunther Hiliger,” Terre des Hommes (1977): VIII. © Drawing by author.

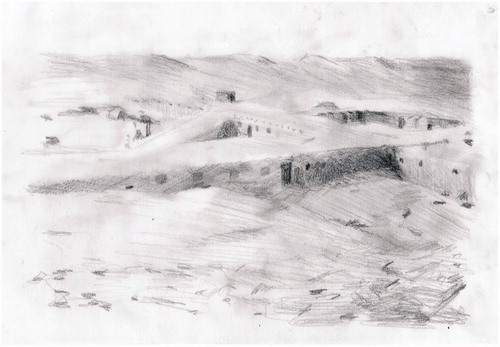

Souilma Beiruk remembered one night when a woman had the idea to fabricate bricks out of the sand. Sahrawi women did not have construction knowledge. Nevertheless, for years, when all the daily tasks were accomplished and the children were sleeping, they met to mold bricks. They accumulated enough bricks to erect walls and started to outline in the sand the plan of the hospital at full scale (). Souilma told us that there were no preliminary plans or paper drawings. The organization of the hospital spaces according to the need of the health committee and external medical aid was discussed by observing the traces inscribed in the ground; rooms were added, and the layout shifted based on the evolution of the needs until the end of the construction process. It is not yet clear how the construction site was managed. From the discussion it emerged that the only division of labor was between the molders and the builders; the plan resulted from collective discussions without hierarchical distinctions. The hospital was built over several months and lasted for years, improving the health conditions of the refugees. Nowadays, only some sand piles exist; the bricks disintegrated under the rain, and women built new health dispensaries in each camp. As the first public infrastructure, this hospital is the evidence of a sociocultural revolution in terms of the apparition of a public sphere embodying new spatialities that emerged from collective discussions and imagination.

Figure 2 Photograph of the National Hospital at the end of the construction redrawn by the author. The original photo (ca. 1978) from the Archives of the Ministry of Information of the SADR was part of a portfolio edited by the Polisario Front for foreign visitors in 1980 to promote the accomplishment of the newborn state. © Drawing by author.

The void left by men

The exile meant leaving behind the traditional wool tents replaced by light tents distributed by NGOs. Movement and the objects’ position in the Jaïma (tents) interior were reinvented through new socio-material assemblages. In the traditional pastoralist encampment called Friq, in which a significant part of the Sahrawi lived before the exodus, the tent’s position was defined by the orientation (main entry at the south, and other entries at each cardinal point) and the social status. While the refugee camp layout erased the social stratification due to detribalization policy, the cardinal points relation remained central. The tents in the camps were organized on a grid determining the proximity between them. The four entries fostered connections, hosting a network of solidarity between the Jaïmas, reconfiguring the social links and the political economy of affection.Footnote47

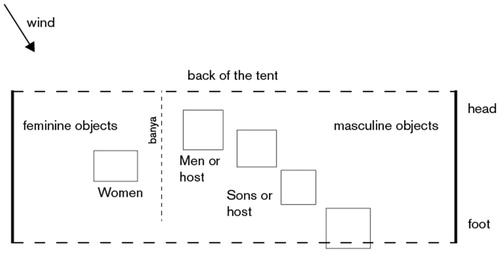

In the traditional Jaïma, everyday objects had a precise position according to the cardinal orientation (). Women’s objects stood at the west of the tent, where women’s activities took place. Men’s objects (weapons and saddle) stood at the east.Footnote48

Figure 3 The Jaïma (Tent): disposition of the interior space, feminine and masculine objects, location of people. Diagram drawn by Julien Lafontaine Carboni according to the anthropological investigation of Sophie Caratini on the Rgaybat, the main tribe that constituted the Sahrawi population. In Sophie Caratini. Les Rgaybāt: 1610–1934. 2: Territoire et société (Paris: Éd. L’Harmattan, 1989). © Drawing by author.

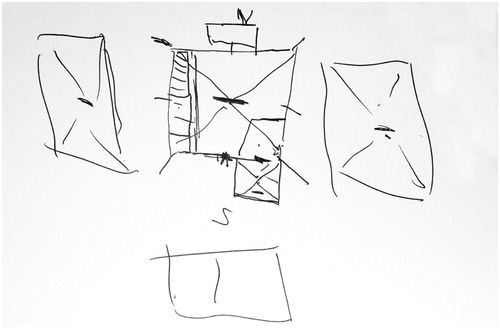

Upon arriving in the camps, the women used the tents according to their habits, ordering objects on the west side of the NGO tent; but the absence of men left a physical void of absent objects. After a while, the Sahrawi women installed cooking utensils and created a proper kitchen on the east side. The kitchen was a small extension enclosed within a fabric that protected the main tent from fire. Around 1985, when women learned to manufacture sand bricks and had time at night, they started to build small rooms on the east for the kitchens, durably changing the tents’ spatialities and the camps ().

Figure 4 The Jaïma. Disposition of the interior space and relations to other tents in the camp (1980–1991). Diagram made by Lahsen Selki Sidi Buna during an interview with Gorba Mohamed Lehbib (March 8, 2020). The women’s objects are on the west side of the tent, while the kitchen is on the east. © Drawing by author.

These minor spatialities are telling signs of the sociocultural transformations, particularly about the changing role of women, which remain invisible, as the protracted sedentarization led to the construction of individual rooms, where the functions are separated and the spatialities fixed. Nowadays, the kitchen position is no longer chosen only according to the orientation, but also in relation to the internal organization of the spaces of the Jaïma.

Conclusions

These three situations unveiled minor architectural events that left no traces such as drawings but threaded a potent architectural image. In this context, the notion of an image refers to non-visual affects,Footnote49 in the form of figurations. When fleeing to the Algerian desert in 1975, the Sahrawis could not bring physical artifacts with them. Nevertheless, beyond the toponymic references to Western Sahara in the camps, the Sahrawis reenacted their land through the maintenance and reinvention of their traditional spatialities. When discussing the interior of the Jaïma, those inventions call for new forms of architectural histories, records, and archives – following minor gestures and spatialities, transmitted body-to-body.

In the Sahrawi society, orality is the essential means of knowledge transmission; writing, as much as drawing, had never been until recently a common practice, leading to a weak viability of the Western concept of archives. Nevertheless, the protracted conflict and refugeehood profoundly affected the social structure. Thus, the system of knowledge circulation was short-circuited by the forced sedentarization. Furthermore, in the soft-power conflict, facing the appropriation of their customs and rewriting their history for colonial means, the absence of an archive proved to be an obstacle to legitimise their culture. To counter this without disregarding their collective knowledge and epistemology, the Ministry of Culture launched an Oral Memory archive. In this context, audio-visual technologies bring into being archiving practices that allow to collect and protect not only tangible and built elements but also virtual and ephemeral cultural events and spatialities. Equally, reenactment, as a particular performance that brings to the surface traces of embodiment and organic forms of knowledge and memory constitutes a decisive means of archiving the Sahrawi spatialities, which the Sahrawis are employing widely to transmit their nomadic knowledge to future generations.

Still, it is crucial to consider this atypical archival condition, where political unrest may limit access. For instance, the refugee camps’ current situation did not allow the author to contact the Archivist for the authorization to publish the photographs, which had to be redrawn in and to be published in this article, due to the new attacks of the Moroccan army against the Polisario position in the liberated territories.

The insight into the Sahrawi archives made me question the architectural archives I knew. Spatialities are not necessarily mediated through archivable documents; other media, like sketches in the sand, gestures, or words, can act in the world, fulfilling a function of memory recall, as architectural drawing would, as in the case of the Sahrawi women’s circle meeting, whose spatialities manifest a history of discussion, debates, and knowledge transmission. The movement of the bodies and the evolution of these gestures give ground to another history of architecture. Similar questions emerged in performance studies and the process of archiving dances and performances, leading to the proposition of the body as an archive. A field of research opens architectural heritage beyond the built and the drawn. The digital artefact and digitization could play a significant role in the widening of the archivable performative-materialities – mostly the gestural – but also in their retrieval and sharing. This perspective would frame another historicity of spatialities, threading minor architectural histories and allowing traces of the undrawn to be archived, far from the dominant Western history and archives we know, outlining a path toward reparations and an active engagement with the potential histories shaping spatialities.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Julien Lafontaine Carboni

Julien Lafontaine Carboni is an architect. He graduated from ENSA Paris-Malaquais and currently pursues a PhD at the ALICE Laboratory, EPFL. He has published in architectural, philosophical, and anthropological journals such as Tabula Rasa. He investigates non-visual epistemologies and architectures, implying other forms of historicity that allow for minor histories to emerge.

Notes

1. For a critique of the Imperialist Western gaze on the archive, see Elizabeth A. Povinelli, “The Woman on the Other Side of the Wall: Archiving the Otherwise in Postcolonial Digital Archives,” Differences 22, no. 1 (2011): 146–171.

2. https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/cultural-mapping (accessed June 1, 2020).

3. Ektoras Arkomanis, “Passage Variations: An Elliptical History of Migration in Eleonas,” Architecture and Culture 7, no. 1 (July 2019): 95–111. On Palestinian camps see, Dorota Woroniecka-Krzyzanowska, “The Right to the Camp: Spatial Politics of Protracted Encampment in the West Bank,” Political Geography 61 (November 2017): 160–169.

4. Robin Evans, “Translations from Drawing to Building,” AA Files 12 (1986): 156, 160.

5. Ibid., 160.

6. Kent Kleinman, “Archiving/Architecture,” Archival Science 1 (2001): 321–332. An example of a building preserved in a museum includes the Chinese merchant house of Yin Yu Tang at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Masschussets.

7. Daniel Libeskind, “Chamber Works: Architectural Meditations on Themes from Heraclitus,” MOMA, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/164668 (accessed June 1, 2020).

8. Robin Evans, “In Front of Lines that Leave Nothing Behind. Chamber Works,” AA Files, 6 (1984): 487.

9. Ibid., 488–489.

10. Ibid.

11. Mark Wigley, “Unleashing the Archive,” Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism 2, no. 2 (2005): 10–15.

12. As quoted by Stuart Hall from Walter Benjamin “To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was.’ It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.” He argues that archives are not inert historical collections. They stand in an active, dialogic relation to the changing questions which the present puts to the past from one generation to another. Stuart Hall, “Constituting an Archive”, Third Text 15, no. 54 (March 2001): 89 and 92. Ariella Azoulay proposed that the archive is “a graveyard of political life that insists that time is a linear temporality: again, an imperial tautology.” Ariella Azoulay, Potential History. Unlearning Imperialism (London: Verso Books, 2019), 186.

13. Jill Stoner, Toward a Minor Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012). Lucía García Jalón Oyarzun, “Excepción y cuerpo rebelde: lo político como generador de una arquitectónica menor/Exception and the Rebel Body: The Political as Generator of a Minor Architecture” (Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, 2017).

14. André Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993).

15. Gilbert Simondon, L’individuation à la lumière des notions de forme et d’information (Grenoble: Millon, 2005).

16. One can find insight on the historicity of the migration of gestures in Carrie Noland and Sally Ann Ness, ed., Migrations of Gesture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008).

17. Nicky Gregson and Gillian Rose, “Taking Butler Elsewhere: Performativities, Spatialities and Subjectivities,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 18, no. 4 (August 2000): 441.

18. Robert Kaiser and Elena Nikiforova, “The Performativity of Scale: The Social Construction of Scale Effects in Narva, Estonia,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26, no. 3 (2008): 123.

19. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (London: Routledge, 2011).

20. Keller Easterling, Medium Design (Moscow: Strelka Press, 2018).

21. David Turnbull, “Maps Narratives and Trails: Performativity, Hodology and Distributed Knowledges in Complex Adaptive Systems? An Approach to Emergent Mapping,” Geographical Research 45, no. 2 (June 2007): 140–149.

22. In his research on Imagination and Invention, Simondon proposes four textures of the image; the driving force, the hosting system of information, an affective resonance of experience, and a cognitive signal as symbol. The invention emerges out of a reorganization of the system of symbols (which is deeply embodied and individuates its milieu in the same motion), which results in a new image as driving force. Images are always a gesture and a movement. In Gilbert Simondon, Imagination et Invention: 1965–1966, ed. Nathalie Simondon (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2014).

23. Noland and Ness, Migrations of Gesture, XII.

24. Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1-14.

25. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Nelson Cary, and Grossberg Lawrence, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture 271 (1988): 271–313.

26. Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009).

27. Ibid., 48.

28. Ibid., 32.

29. Povinelli, “The Woman on the Other Side of the Wall,” 146–171.

30. Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide (London / New York: Routledge, 2016).

31. Janina Gosseye, Naomi Stead, and Deborah Van der Plaat, eds, Speaking of Buildings: Oral History in Architectural Research (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2019), 10.

32. Kleinman, “Archiving/Architecture,” 321–332.

33. André Lepecki, “The Body as Archive: Will to Reenact and the Afterlives of Dances,” Dance Research Journal 42, no. 2 (2010): 28–48.

34. Ibid., 31.

35. Farocki developed it in Workers leaving the Factory or The expression of hands. Thomas Elsaesser, Harun Farocki: Working on the Sightlines (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2004).

36. Arkomanis, “Passage Variations,” 95–111.

37. Ariella Azoulay and Louise Bethlehem, Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography (London: New York: Verso, 2012).

38. Lynette Russell, “Indigenous Knowledge and Archives: Accessing Hidden History and Understandings,” Australian Academic & Research Libraries 36, no. 2 (January 2005): 161–171.

39. Terry Cook, “Evidence, Memory, Identity, and Community: Four Shifting Archival Paradigms,” Archival Science 13, no. 2–3 (June 2013): 34.

40. Nancy MacKay, Curating Oral Histories: From Interview to Archive (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2007).

41. Jacob A. Mundy, “Performing the Nation, Pre-Figuring the State: The Western Saharan Refugees, Thirty Years Later,” The Journal of Modern African Studies 45, no. 02 (June 2007): 275.

42. Tomás Bárbulo, La historia prohibida del Sáhara español, Imago mundi 21 (Barcelona: Ediciones Destino, 2002). Juan Carlos Gimeno Martìn, and Juan Ignacio Robles Picón, “Vers une contre-histoire du Sahara occidental,” Les Cahiers d’EMAM. Études sur le Monde Arabe et la Méditerranée, 24–25 (January 1, 2015).

43. Sophie Caratini, La république des sables: anthropologie d’une révolution (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2003). Konstantina Isidoros, Nomads and Nation-Building in the Western Sahara: Gender, Politics and the Sahrawi (London: I.B. Tauris, 2018).

44. Manuel Herz, From Camp to City: Refugee Camps of the Western Sahara (Zürich: Lars Müller, 2013).

45. Women constitute around 90 percent of the adult and capable population.

46. Tamarix aphylla, a species of Acacia.

47. Isidoros, Nomads and Nation-Building in the Western Sahara, 2018.

48. Julio Caro Baroja, Estudios saharianos (Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos, 1955).

49. On non-visual image and affects, read the introduction of Stoner, Toward a Minor Architecture, 2012. Lucía García de Jalón Oyarzun, “Nightfaring & Invisible Maps: Of Maps Perceived, but Not Drawn,” The Funambulist, 18 (2018): 40–43.

References

- Arkomanis, Ektoras. 2019. “Passage Variations: An Elliptical History of Migration in Eleonas.” Architecture and Culture, Spaces of Tolerance 7, no. 1: 95–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/20507828.2019.1558381.

- Azoulay, Ariella, and Louise Bethlehem. 2012. Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography. London; New York: Verso.

- Azoulay, Ariella, and Louise Bethlehem. 2019. Potential History. Unlearning Imperialism. London: Verso Books.

- Bárbulo, Tomás. 2002. La historia prohibida del Sáhara español. Imago mundi 21. Barcelona: Ediciones Destino.

- Butler, Judith. 2011. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York; London: Routledge.

- Caratini, Sophie. 1989. Les Rgaybāt: 1610–1934. 2: Territoire et Société. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Caratini, Sophie. 2003. La république des sables: anthropologie d’une révolution. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Caro Baroja, Julio. 1955. Estudios saharianos. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Cook, Terry. 2013. “Evidence, Memory, Identity, and Community: Four Shifting Archival Paradigms.” Archival Science 13 (2–3): 95–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-012-9180-7.

- Easterling, Keller. 2018. Medium Design. Moscow: Strelka Press.

- Elsaesser, Thomas. 2004. Harun Farocki: Working on the Sightlines. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Evans, Robin. 1984. “In Front of Lines that Leave Nothing Behind. Chamber Works.” AA Files, 6: 89–96.

- Evans, Robin. 1986. “Translations from Drawing to Building.” AA Files 12: 3–18.

- Gosseye, Janina, Naomi Stead, and Deborah Van der Plaat, eds. 2019. Speaking of Buildings: Oral History in Architectural Research, 10. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Gregson, Nicky, and Gillian Rose. 2000. “Taking Butler Elsewhere: Performativities, Spatialities and Subjectivities.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 18, no. 4: 433–452. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/d232.

- Hall, Stuart. 2001. “Constituting an Archive.” Third Text 15, no. 54: 89–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09528820108576903.

- Hartman, Saidiya. 2008. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2: 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1.

- Herz, Manuel, ed. 2013. From Camp to City: Refugee Camps of the Western Sahara. Zürich: Lars Müller.

- Isidoros, Konstantina. 2018. Nomads and Nation-Building in the Western Sahara: Gender, Politics and the Sahrawi. London and New York: I. B. Tauris.

- Jalón Oyarzun, Lucía García de. 2017. “Excepción y cuerpo rebelde: lo político como generador de una arquitectónica Menor/Exception and the Rebel Body: The Political as Generator of a Minor Architecture.” Thesis. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid.

- Jalón Oyarzun, Lucía García de. 2018. “Nightfaring & Invisible Maps: Of Maps Perceived, but Not Drawn.” The Funambulist 18: 40–43.

- Kaiser, Robert, and Elena Nikiforova. 2008. “The Performativity of Scale: The Social Construction of Scale Effects in Narva, Estonia.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26, no: 3: 537–562. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/d3307.

- Kleinman, Kent. 2001. “Archiving/Architecture.” Archival Science 1: 321–332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02438900

- Lepecki, André. 2010. “The Body as Archive: Will to ReEnact and the Afterlives of Dances.” Dance Research Journal 42, no: 2: 28–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0149767700001029.

- Leroi-Gourhan, André. 1993. Gesture and Speech. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Libeskind, Daniel. 1983. “Chamber Works: Architectural Meditations on Themes from Heraclitus.” MOMA. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/164668.

- MacKay, Nancy. 2007. Curating Oral Histories: From Interview to Archive. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Martìn, Juan Carlos Gimeno, and Juan Ignacio Robles Picón. 2015. “Vers une contre-histoire du Sahara occidental.” Les Cahiers d’EMAM. Études sur le Monde Arabe et la Méditerranée, 24–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.4000/emam.866.

- Mundy, Jacob A. June 2007. “Performing the Nation, Pre-Figuring the State: The Western Saharan Refugees, Thirty Years Later.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 45, no. 2: 275–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X07002546.

- Noland, Carrie, and Sally Ann Ness, eds. 2008. Migrations of Gesture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Povinelli, Elizabeth A. 2011. “The Woman on the Other Side of the Wall: Archiving the Otherwise in Postcolonial Digital Archives.” Differences 22, no. 1: 146–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-1218274.

- Russell, Lynette. 2005. “Indigenous Knowledge and Archives: Accessing Hidden History and Understandings.” Australian Academic & Research Libraries 36, no. 2: 161–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2005.10721256.

- Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. 2016. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. London; New York: Routledge.

- Simondon, Gilbert. 2005. L’individuation à la lumière des notions de forme et d’information. Grenoble: Millon.

- Simondon, Gilbert. 2014. Imagination et Invention: 1965–1966. Édité par Nathalie Simondon. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty, Nelson Cary, and Lawrence Grossberg. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture 271: 271–313.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2009. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Stoner, Jill. 2012. Toward a Minor Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Turnbull, David. 2007. “Maps Narratives and Trails: Performativity, Hodology and Distributed Knowledges in Complex Adaptive Systems? An Approach to Emergent Mapping.” Geographical Research 45, no. 2: 140–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2007.00447.x.

- Wigley, Mark. 2005. “Unleashing the Archive.” Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism 2, no. 2: 10–15.

- Woroniecka-Krzyzanowska, Dorota. 2017. “The Right to the Camp: Spatial Politics of Protracted Encampment in the West Bank.” Political Geography 61: 160–169. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.08.007.