Abstract

This paper discusses Architectural History and Theory at the Graduate School of Architecture, University of Johannesburg in 2019. The curriculum is centered on a series of conversations as the means to generate forms of engagement for a plurality of voices, contested views and dialogic encounters, as a way of working toward an alternative institutional imaginary. The focus on conversation and dialogue aims to create a space for slow and shared scholarship, to become a manifestation of spatial resistance to the imperatives of the neoliberal university and global economies of higher education. This paper discusses some of the key conceptual and practical moves undertaken in the development of a new history and theory course through examples of student work. The paper points to inclusive and reflexive pedagogical methods and modes of collaboration as central to resistance, and as the means that enable generative and supportive networks across geographic and institutional boundaries.

Conversations in Architectural History and Theory

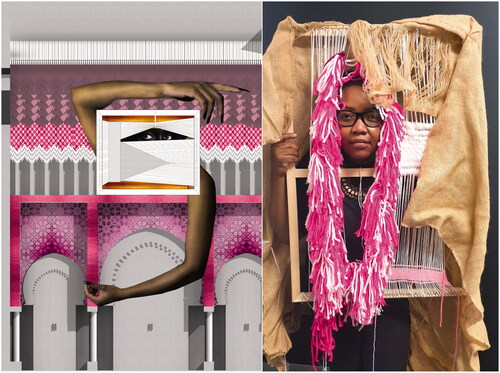

In a provocative opening performance on the 10th of September 2019, at 68 Juta Street, in Braamfontein, central Johannesburg, a Masters of Architecture student at the Graduate School of Architecture (GSA), University of Johannesburg, Gugulethu Mthembu articulated: “you have been taught to grow up, I have been taught to grow in…I have been taught accommodation.”Footnote1 Mthembu’s comments on “growing up” and “growing in” questioned what it means to be a black female body within an architectural school with historically very little space for Black positionality, recognition and voice. Mthembu’s performance, which forms part of her architectural design thesis involves a series of installations, drawings and live recitals (). Her provocation was the first in a day of conversations, bringing into direct question issues of gender, race and the limits and extents of architecture with regards to the location of the black body within space.

Figure 1 The port of Sihr, MArch Thesis project GSA Unit 12, 2019. Performed and designed by Gugulethu Mthembu.

This performance took place at the 2019 Architectural History and Theory colloquium or Conversation Rooms, which marked the culmination of the first year of teaching a new architectural History and Theory course titled “Methods, Fields and Archives.” The course as a whole is centered on a series of conversations as the locus around generating forms of engagement for a plurality of voices, contested views and dialogic encounters. The colloquium, therefore, marked the public endpoint of a series of engagements throughout the year. These conversations that take place through seminars, reading groups and the colloquium are seen as a way of talking and working through an alternative architectural history and ultimately an alternative institutional imaginary. The Architectural History and Theory course at the GSA, and the emphasis on conversation and dialogue, aimed to create a space for slow and shared scholarship, to make room for critical thought among tutors and students, and to become a manifestation of resistance to the imperatives of the neoliberal university and global economies of higher education. This article discusses some of the key conceptual and practical moves undertaken in the course to provoke discussion through examples of student work. The paper points to inclusive and reflexive pedagogical methods and modes of collaboration as central to resistance, and as the means that enable us to establish generative and supportive networks across geographic and institutional boundaries.

Architectural History and Theory at the GSA

In 2019 I joined the GSA as the programme convener for History and Theory and found a welcoming space within the wider pedagogical agenda of Transformative Pedagogies. The GSA, and project of Transformative Pedagogies, was established by Prof. Lesley Lokko in 2016, in the aftermath of the Fees Must Fall protests in South Africa.Footnote2 From the outset, the intention was to create a space for an alternative architectural culture for the African continent. The school grew from 11 students in 2016 to 90 students in 2021.Footnote3 The success in student numbers reveals the popularity of this program among students from across the continent. This popularity has been built by student and alumni work, which found a space to respond to alternative spatial imaginaries which reverberate across scales, from the intimate present to the urban, national, continental and planetary. As Lokko explains, Transformative Pedagogies was established as a research and teaching program, that sought to transform “both the way we teach architecture and what we teach.”Footnote4 She notes that student activism in South African universities in 2015 was clearly fueled by two distinct yet related issues: of socio-economic difficulties for poor students, and the “cultural alienation of Black students at historically white universities.”Footnote5 In the manifesto which sets out the intentions and thinking behind the school, she states “At the GSA, we chose to address curriculum as both content and praxis: in other words, focusing not on individuals or the group in isolation, but rather through exploring how both individuals and groups create understandings and practices […] We need to keep encouraging critique and problematization of what is considered to be knowledge and the processes involved in generating it.”Footnote6 For Lokko, the aim was not the creation of a new kind of regionalism for South Africa, but rather to construct a space for critical engagement with architectural knowledge from Johannesburg, an African city. Mthembu’s performative architecture, which talks to the problematic of architecture schools as historically spaces to stifle Black voices, or indeed their outright absence, is one example of a project which both critique’s existing frameworks, and questions what an embodied and performative architecture could be. Lokko’s Transformative Pedagogies agenda provided a space to further question what a history and theory curriculum might offer, beyond the existing canon.

The GSA has made its mark in terms of design teaching and design research in and from South Africa. History and theory has however been a difficult terrain to negotiate, for various reasons. Much of the existing research on modern and post-independence architecture on the African continent focuses on the role of expatriate or settler colonial architects.Footnote7 “Africa” is often reduced to a level of ornamentation or “traditional references,” an essentializing and reductive approach that epistemologically, tends to mirror colonial frameworks. As a survey of anglophone schools across the continent by Ikem Okoye points out, “Architectural historians, whether African, American, or European, are used to the moniker “African” standing for something essential – something traditional or indigenous, a locally invented product uncontaminated by more globalized histories.”Footnote8 As Okoye notes in his 2002 published study, it remains unclear what an African architectural history is, or indeed where it might be positioned in schools that are generally professionally oriented.Footnote9 With no courses specifically producing architectural historians on the African continent, what little discursive culture exists largely remains firmly tied to the object building often within a global developmentalist framework that demarcates the African continent as a space of lack or poverty. In South African universities, where architectural survey courses have been updated, this is often with sociological surveys on the African city, which treat “Africa” as a generic category. Although these courses often shift the focus to the African continent, their focus on “urgent” and “present” questions of informality, poverty and infrastructure rarely understand “Africa” as a space of design, visual cultures or associated critical commentary. These often well-intended efforts, therefore, reinforce the suggested “absence” of architecture, or indeed a history of architecture, on the continent. Yet, as Christina Sharpe prompts, history is always in the room with us and “the past that is not the past, reappears, always, to rupture the present.”Footnote10 How do we, therefore, speak from this position of the absence of “history”? And what might this mean for how “architecture” is understood?

As a discipline, architectural history is rooted in the nineteenth century construction of the distinction between the “west” and its “other,” where the “west” was considered a site of knowledge production, and the “other,” at best, the site of vernacular and non-historical styles. This is exemplified in the Bannister Fletcher Tree of History.Footnote11 Architectures of the so-called “non-west,” considered “native,” were understood as spaces associated with the tribal and primitive body rather than sites produced through discourse, following Itohan Osayimwese.Footnote12 Indeed, in many cases, these “other” architectures were relegated to anthropological and archaeological studies rather than considered as architecture. The work of architectural scholars drawing on postcolonial theory has played an important role in questioning the power-relations within the archive and its association with colonialism.Footnote13 More recent efforts in global, worldly, and planetary histories have widened the sites of research in an effort to provincialize the “western” canon.Footnote14 This growing effort to reveal the untold histories of architecture in peripheral and underrepresented sites has led to a plethora of significant work on trans-national movements and networks, and global relationships of production and construction. Yet, in many cases, the place of theory and knowledge production remain in the “west” while the “other” is considered the “field” for gathering data. The historiographical and epistemological underpinnings are rarely questioned. This is played out in the growing interest in fieldwork and ethnographic methods, seen as key to “de-centring” architectural history. While this approach expands the sites of studies, in many cases the architectural truths defined, produced and constructed in the “west” as “center” remain largely in place. Following Sara Ahmed, I argue for the importance of recognising that the absence and associated violence and coloniality of knowledge are produced and reproduced in institutions. This is a context where the post-Apartheid institution in South Africa is located within wider neoliberal global economies and hierarchies of higher education, and associated practices of hostility which particularly disenfranchize Black and brown bodies.Footnote15

Methods, Fields and Archives

In developing a history and theory course at the GSA, the impetus was to question both what architectural history might be in terms of content, and also how it might enable us to think and theorize architecture differently. Contesting the prefiguration of distinctions between methods, fields and archives, the course suggested bringing these into conversation to understand their entangled nature. While the field remains a site for gathering data on the “other,” the archive is often treated as a siloed, sacred and western source of knowledge. In foregrounding the decolonial focus on both praxis and content,Footnote16 the course questions the existing canon of the architect-architecture-architectural, by looking to the margins and edges of architecture as a discipline. The limitations of the architectural canon are not seen as disabling, but rather, following Anooradha Siddiqi, seen as an opportunity to “shift the historiographical gaze toward alternate forms of intellectual and material productivity.”Footnote17 As Lokko has noted in the framing of the GSA, the wider interest in the school at the time, was not only in a change of curricula, but as a set of practices, in order to question what we do and how we do it.Footnote18

This emphasis on praxis and content is related to how institutionality gets produced and reproduced. Ahmed reminds that while institutions have become associated with an established order and assumed stability, what is often overlooked is the “instituting” aspect of that which is “instituted.”Footnote19 She asks us to think of institutions as both verbs and nouns, to recognize the processes, labor and work which go into institutionality, “to attend to how institutional realities become given, without assuming what is given by this given.”Footnote20 Institutions produce and reproduce certain forms of knowledge through content. Within architecture, these range from the academic institution, to the various professional bodies and accreditation boards which validate and decide who can practice and how. Institutions are the site of the production and reproduction of architectural knowledge, and what is deemed as architecture. They are collective endeavors, involving all those who do the work to establish, maintain, and actively produce the physical and intellectual space on a daily basis. While in the global north institutions are often critiqued as being resistant to change, in the global south they tend to be discussed in relation to their failures and absence. Yet, I would argue that this supposed “absence” itself, allows and enables for a continuation of inherited coloniality.

In response to this wider context, the history and theory course is structured as a series of thematic seminars, each of which focuses on a different form of architectural dissemination. These range from manifestos, fiction and film to exhibitions and oral histories. These forms are understood as central to how architecture is recorded, remembered, conceptualized and understood. Each week, in addition to completing a set of readings, students are asked to engage directly with the form. For example, the assignment prompts include the production of a short fictional text, a study of an actual exhibition in the city, or the writing of a manifesto. The seminar is therefore both the space of conversation and dialogue around the thematic and set of media that have been assigned, as well as a space for engaging with the material students have themselves produced in response. While the structure of thinking through forms of architectural dissemination is widely used globally and not unique in itself, what is particularly important here is that works considered more canonical are combined with those that are not usually considered “architecture.” The students are therefore actively engaging with a “stretching” out of architecture as a discipline in the Fanonian sense, an act they are encouraged to continue in how they produce their own responses. For example, while Italo Calvino’s, Invisible CitiesFootnote21 or Georges Perec’s “The Apartment”Footnote22 are commonly used text in architectural courses around the world, very seldom are Black or brown fictional voices represented. In contrast, as an example, included in this curriculum, in different stages of this course have been Jamaica Kincaid’s, A Small Place,Footnote23 Miriam Tlali’s Soweto Stories,Footnote24 and Alexis Pauline Gumbs M Archive.Footnote25 These deliberate additions of black female voices from the African continent and diaspora ask a student to engage with black female positionality directly rather than lament their absence. In these examples fiction becomes a tool for postcolonial critique, and speculative science fiction, as a way of imagining other possible futures. These texts ask students to engage with the lived reality of those often not included in the architectural archive proper.

This inclusion of widely marginalized voices in the course handbooks, in turn sets a precedent for how students respond to the tasks, inviting them to bring in additional literature, a wide variety of resources, and experiences of the city. For many South African students of color, their experiences of post-Apartheid cities is often also excluded from institutional spaces and how architecture has historically been taught. The seminar, and this ground for additional material, becomes a space for “speaking to one another,” following Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Spivak asserts the importance of “speaking to” instead “speaking for” the subaltern subject, where “speaking to” is an active gesture that involves a transaction between a speaker and a listener.Footnote26 The change in curriculum content creates the ground for the basis of the conversation, asserting the validity of voices not usually accommodated and thereby inviting in a variety of perspectives. This is an acknowledgment of the unequal grounds of “speaking,” and a gesture toward a radical inclusion, whether considered architectural or not.

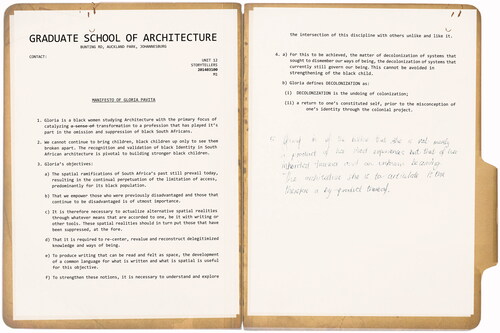

As one example, the student Gloria Pavita responded to the week on manifestos, by producing a manifesto for herself, focused on questions on the positionality of Black women studying Architecture. Pavita’s response as seen in was in some ways framed by a long history of manifesto writing by architects. As David Roberts has suggested manifesto writing in architecture can be understood “as relational and reflexive acts [which] correspond to approaches of ethical deliberation and imaginative identification.”Footnote27 The manifesto in architecture is a way of working between the existing context, and a possible future. Yet as Roberts also articulates, the “manifesto is a reminder of the privilege of who has been able to speak in spheres of public exchange and who has been excluded,”Footnote28 because they have not been able to speak on the public domain. He points to a survey of 110 architectural declarations from around the world, which included only 5 from the Global South. In Pavita’s writing, we see a deliberation on what it means to be a Black woman in architecture. She borrows the form of this manifesto from her work in student activism outside of the department, deliberately unsettling and actively politicizing how architectural education is understood. In particular, Pavita questions the potential of language and ways of writing for how we might expand architecture to consider the Black subject. She suggests as part of her objectives, “to produce writing that can be read and felt as space, the development of a common language for what is written and what is spatial is useful for this objective.”Footnote29 Although unreferenced, Pavita is pointing to a longer debate around the power and potential of language. As Hortense Spiller articulates, our language and grammar are an inherited form of “capture” that enables the violence of anti-blackness.Footnote30 While Spiller’s work is framed around the afterlife of slavery in the United States, the implications are wide-reaching. In a different context, this argument is extended by Kathryn Yusoff in her articulation of the deeply embedded anti-blackness and coloniality of geology as a discipline and the language it employs.Footnote31 Drawing on these theorists, the absence of black bodies in architectural curricular, for example, is not incidental but an inherent part of the coloniality of inherited western knowledge systems, and their continued implementation. This manifesto is one example of bringing these questions to the seminar room, as a central and starting point of conversation.

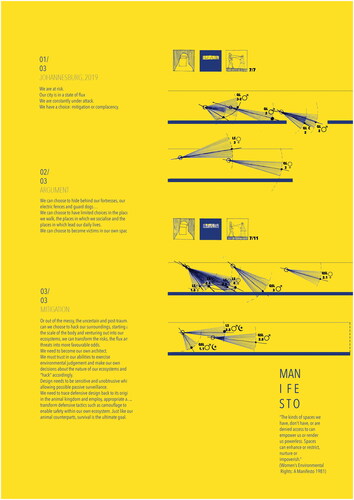

A second example from the seminar room is the manifesto by Azraa Gabru,Footnote32 seen in . Gabru offers a statement on questions of gender and safety in Johannesburg. Unlike Pavita’s, Gabru borrows certain linguistic tactics from more established architectural manifestos. There is an indirect reference here to Le Corbusier’s Toward an ArchitectureFootnote33 in the syntax and structure of the initial sentences and a direct reference to Leslie Kanes Weisman’s “Women’s Environmental Rights: A Manifesto.”Footnote34 This is no doubt deliberate, and perhaps, points to a critical move in terms of citations. Yet, this manifesto makes certain playful and direct moves which ask us to rethink what and how we see the world. The set of drawings alongside the manifesto, clearly articulate the position of a Muslim woman in full niqab, and the seemingly analytical diagrams point to an engagement with the dialectic between what she might see looking out, and how she might be seen. The result is an ambivalent response which questions understandings of safety, gender, scientific analysis and clarity, with a suggestion that the hijab is understood as the construction of a micro-environment and understood as a means of engaging with the urban street. Gabru indicated the missing ends of sentences was deliberate. For the reader, the result is that the text begins to undo itself, and in turn the manifesto, asks questions of authorship, positionality and of how choice operates in the world. Gabru’s manifesto asks us to consider from whose perspective or position we view and construct the center and margin, and through a playful misplacement reveals the recentering of “man.”

These are two examples from one seminar, illustrative of the kinds of questions many other students are interested in and engage with. These weekly assignments and associated seminar discussions provided a space for students to test out and enact positionalities through discussion and dialogue with each other and a seminar tutor. Importantly, these were not reductive engagements based on the static limits of identity politics, but rather expansive engagements with the basis of how we might see the world through the lens of difference, in order to learn how to look differently. Thinking with bell hooks,Footnote35 they ask how choosing the margin as a space of radical openness, might enable us to extend, break open and critique existing canonical frameworks. While the seminars formed one platform and space for speaking within a classroom setting, optional bi-weekly reading groups led by design teaching staff added an additional platform, with an alternative set of material curated by the facilitator. The colloquium in turn, opened these conversations to the wider public, which included students and staff from neighboring architectural schools.

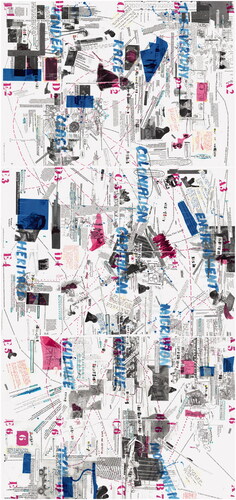

The final platform for the course was created and curated by the students themselves, through the design and publication of a zine. is the base mapping which was later reworked and rescaled in order to produce the zine that was distributed at the end of year exhibition. This mapping was produced by seven students, namely Azraa Gabru, Jana Cloete, Sarah Harding, Jackson Change, Karabo Moumakwe, Thelma Ndebele, Gloria Pavita and Izak Potgieter, who volunteered to curate the work of the remainder of the cohort. The mapping is an engagement with the wider work produced by all 48 students in the Honors year. This mapping is therefore both a collective product, curated and produced by indexing key concerns across the year in the work of students. In producing an atlas of student work over the course of 2019, the zine itself starts to question the boundary between that deemed architecture, and its outside. This collective publication has become part of the course, and in 2020 took the form of an auditory zine, located on Instagram.Footnote36 In both cases, it becomes a platform for students to engage with the work of each other directly, and the wider audience. As course convener, I provided commentary on feedback at various points while a design developed, and through the organization of a workshop with a graphic designer. Yet the entire process, from planning to production was managed by students themselves. To look beyond the disciplinary restrictions of architecture is not new. As Gülsüm Baydar Nalbantoḡlu has argued, with many others, architecture is not a “stable and secure autonomous entity,” but is constantly defining that which is included and excluded. The question she raises, still of relevance here, is “How are architectural boundaries constructed and on what basis?”Footnote37 The mapping for this zine not only catalogues student work, but also begins to suggest an alternative indexing for how we might read architecture.

Conversation Rooms: 10 September 2019

The colloquium held on the 10th of September 2019, at GSA Metro in Braamfontein Johannesburg, was a central part of extending and expanding the conversations and dialogues that were happening within the course and among students. It was co-curated and organized in collaboration with Sumayya Vallly and Sarah de Villiers of Counterspace, both design teaching staff at the GSA. While the colloquium was rooted in the Architectural History and Theory course, it was also tied into wider conversations that have been longer standing, and the day saw a series of presentations by students and invited academics, speaking on the same platform.Footnote38 One particular extended conversation has been between the organizers of the colloquium and members of the Break//Line Collective,Footnote39 Thandi Loewenson, David Roberts and Miranda Critchley over the course of 2019. Our initial conversations over skype and in person, between London and Johannesburg, varied from discussions on the hostile environment policy in the UK as they play out in institutions of higher education, to questions of globalized institutional racism as embedded in policy, teaching practices and curricula. In some cases, these were an extension of conversations that were established through the development of the open-access curriculum, Race, Space & Architecture.Footnote40 Important to these extended dialogues was the value of understanding the wider implications of race, and how they play out in the global economies and hierarchies of higher education. Many of the boundaries to university for people of color are common across geographic boundaries, evident in how institutions function and academic hegemony. While the particular institutional and national contexts are significant and important, these trans-national dialogues are a reminder of the value of foregrounding collaborations and networks of solidarity across geographies. They are a reminder of the global economies we all operate within, where the financialization of higher education has led to the increasing precarity of academics more generally.

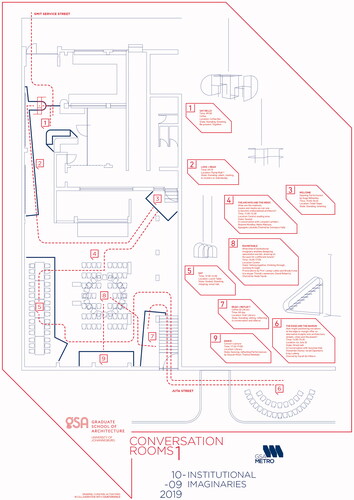

The colloquium that evolved from these series of conversations and engagements, resulted in a day-long choreographed event. shows the resultant choreography, which actively moved audience and speakers throughout the day, from the interior of this basement, to the street space outside. While, as organizers, we fully recognized that moving a conversation onto the street might not be enough to draw in additional “publics,” we also suggest it is an important gesture that does deliberately place a public institution in the eyes of the public – inviting passersby to stop, engage and slow down. The presentations were printed on weather proof boards and remained as a street exhibition for several months following the colloquium (). The planning returns to the spatiality offered by architecture as a discipline, in order to disrupt what might be expected of an academic event and to suggest alternative modes of enquiry that can coexist. Drawing on Ahmed, we recognize that “public space takes shape through the habitual actions of bodies, such that the contours of space could be described as habitual.”Footnote41 Ahmed suggests that we think of the habitual as a form of inheritance, that is both bodily and spatial. When engaging with institutions, these are places shaped by the “proximity of some bodies and not others: white bodies gather, and cohere to form the edges of such spaces.”Footnote42 Choreographing the day was part of an active tactic of questioning and disrupting habits, and their associations with particular kinds of raced and gendered bodies. With a provocation from Fred Moten, as quoted by to Natasa Petresin –Bachelez, to “slow down, to remain, so we can get together and think about how to get together.”Footnote43 Following bell hooks, in Teaching to Transgress, Footnote44 the colloquium opened up a radical and celebratory space of possibility, if only temporarily.

Toward Alternative Institutional Imaginaries

As an extension of the conversations with the Break//Line collaborative, on the 10th of September 2019, we were joined throughout the day by David Roberts and Thandi Loewenson, who contributed with a skype response and visual screenshot of their thoughts, responses, provocations and resonances in reflecting on the colloquium (see ). They wrote of the experience, “our position on the virtual margin, behind three screens, two google docs, multiple notes and connected through the (shaky) internet has facilitated the creation of a document of references and notes which we will share in time to come. However, attending to the Fred Moten quote, “this may be finalized, slowly, in the longness of time.”Footnote45

Figure 7 A gathering of Screen-Shots at a distance, 2019, Break//Line: Thandi Loewenson and David Roberts.

Loewenson and Roberts drew on Christina Sharpe’s concept of “wake-work,” to “labor within the spaces of paradoxes surrounding black citizenship, identity and civil rights.” In reference to Sharpe, they ask how performing “wake-work” might point to new and alternative institutional imaginaries, asking “How can you work in a way which is both cognizant of violence and crafts an alternative?”Footnote46 While remaining aware that the challenges of the institution cannot be solved immediately, Loewenson and Roberts point to the multitude of forms of resistance that can and must continue and the value of spaces for conversation for working through difficult institutional spaces. Drawing out and reflecting on the day, they return to Gugu Mthembu’s provocation, to suggest that we need to find new practices and ways of working that are not about “accommodating.” Working across and outside of institutional boundaries, they point here to a warning about the co-opting of work on race and justice by neoliberal institutions. As Sarah Ahmed reminds us, institutional diversity practices within institutions often “allow racism and inequalities to be overlooked.”Footnote47 The labor in developing anti-racist and feminist curriculum projects, by a few staff and students can often be instrumentalized and commodified to sell a “vision” of transformation, which does not necessarily translate into nor reflect wider institutional change both in terms of who remains in power, and how the institution functions. Loewenson and Roberts suggest instead “a practice which does not seek to merely soften the edges of institutions or disciplines but is transformative of the kinds of knowledges which are held and produced within them.”Footnote48 Working beyond institutional boundaries, collaboratively, is one means of resisting this neoliberal impetus and developing supportive, shared networks for this work.

In her discussion on institutional diversity and racism, Ahmed argues for “thinking more concretely about institutional spaces, about how some more than others will be at home in institutions that assume certain bodies as their norm.”Footnote49 The series of conversations retold here are in many ways about bodies in space and in architecture. They are about researchers, tutors, and students trying to find a space to speak from, and from where to speak back. If policy is not so much about what documents on diversity or anti-racism say, but what they do, following AhmedFootnote50 the series of conversations was focused on practices within the institution. The seminar spaces, reading groups and colloquium were not organized around a binary notion of agency versus subjection. They do not assume or suggest that change in platform will automatically become a vehicle of liberation or fundamental change. Yet the inclusion of wider voices, and different kinds of bodies sets the stage for conversations to happen at the margins and edges of Architectural History and Theory. Setting the stage in turns claims a space for conversations to stretch what the discipline could be.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Huda Tayob

Huda Tayob is currently a senior lecturer at the University of Cape Town. She was former History and Theory of Architecture Programme Convener and co-leader of Design Unit 18 at the Graduate School of Architecture, University of Johannesburg. She trained as an architect at the University of Cape Town and subsequently worked in architectural practice prior to completing a PhD at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL in 2018. Her doctoral research looked at the spatial practices of African migrants, immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers in Cape Town, with a particular focus on mixed-use markets established and run by these populations. Much of this work is grounded in feminist approaches to both historiography and methodologies of practice. She received a Commendation from the RIBA President’s Medal Research Award committee for her PhD. Her wider academic interests include a focus on minor and subaltern architectures, the politics of invisibility in space, and the potential of literature to respond to archival silences in architectural research. Her recent publications include “Subaltern Architectures: Can Drawing ‘tell’ a Different Story” (Architecture and Culture, 2018) and “Architecture-by-migrants: The Porous Infrastructures of Bellville” (Anthropology Southern Africa, 2019).

Notes

1. Gugulethu Mthembu, “The Port of Sihr” (MArch thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2019).

2. Lesley Lokko, “A Minor Majority,” ARQ: Architectural Research Quarterly 21, no. 4 (2017): 387–392; Fees Must Fall protests took place in 2015 across South African universities. While initially spurred by the Rhodes Must Fall movement, directed at the removal of the Cecil John Rhodes statue at the University of Cape Town, the later widespread protests focused on student demands for decolonising the curriculum and free access to higher education.

3. Lesley Lokko, “African Space Magicians,” in …And Other Such Stories, eds. Yesomi Omulu, Sepake Angiama, and Paulo Tavares (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2019).

4. Ibid., 389.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Much of the existing research on modern and post-independence architecture on the African continent focuses on the role of expat architects from Poland, Israel, Germany and, notably, Britain among others.

8. Ikem Okoye, “Architecture, History and the Debate on Identity in Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa,” JSAH 61, no. 3 (2002): 382.

9. This is shown to still be the case in a more recent study by Mark Olweny which illustrates the dominance of technical aspects of architecture across sub-saharan Africa: Mark Olweny, “Architectural Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Investigation into the Pedagogical Positions and Knowledge Frameworks,” The Journal of Architecture 25, no. 6 (2020): 1–19.

10. Christina Sharpe, In the Wake (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 8.

11. Lesley Lokko, White Papers, Black Marks: Architecture, Race, Culture (London: Athlone Press, 2000).

12. Itohan Osayimwese, “Architecture and the Myth of Authenticity During the German Colonial Period,” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 24, no. 2 (2013): 11–22.

13. Sibel Bozdogan, “Architectural History in Professional Education: Reflections on Postcolonial Challenges to the Modern Survey,” Journal of Architectural Education 52, no. 4 (1999): 207–215.

14. There are a wide range of projects, including the Global Architectural History Teaching Collaborative (GAHTC), and the 2020 revised Bannister Fletcher edited by Murray Fraser.

15. Sara Ahmed, On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012).

16. Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial, Kerem Nişancıoğlu, eds., Decolonising the University (London: Pluto Press, 2018).

17. Anooradha Siddiqi, “Crafting the Archive: Minnette De Silva, Architecture and History,” Journal of Architecture 22, no. 8 (2017): 1301.

18. Lokko, “A Major Minority,” 390.

19. Ahmed, On Being Included, 20.

20. Ibid., 21.

21. Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, trans. William Weaver (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974).

22. Georges Perec, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, trans. John Sturrock (London: Penguin Classics, 2008(1974)).

23. Jamaica Kincaid, A Small Place (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1988).

24. Miriam Tlali, Soweto Stories (London: Pandora Press, 1989).

25. Alexis Pauline Gumbs, M Archive (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018).

26. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?,” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, eds. C. Nelson and L. Grossberg (Basingstoke: Macmillan Education, 1988), 271–313, 301.

27. David Roberts, “Why Now: The Ethical Act of Architectural Declaration,” Architecture and Culture 8 (2020): 1–19.

28. Ibid., 9.

29. Gloria Pavita, “Manifesto,” Honours Architectural History and Theory (Johannebsurg: University of Johannebsurg, 2019).

30. Hortense J. Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (1986): 64–81.

31. Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018).

32. Azraa Gabru, “Manifesto,” Honours Architectural History and Theory (Johannebsurg: University of Johannebsurg, 2019).

33. Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture (New York: Dover Publications, (1923)1985).

34. Leslie Kanes Weisman, “Prologue: Women’s Environmental Rights: A Manifesto,” (1981) republished in Gender Space Architecture, eds. Jane Rendell, Barbara Penner, and Iain Borden (London: Routledge, 2000), 1–5.

35. bell hooks, “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness,” in Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, ed. bell hooks (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1990), 145–53.

36. See Instagram page @kota_vol.2_2020 Curated and designed by Mbali Vilakazi, Natalie Harper, Dylan Fernandes, Gio Rech and Claudine Williams.

37. Gülsüm Baydar Nalbantoḡlu, “Toward Postcolonial Openings: Rereading Sir Banister Fletcher’s ‘History of Architecture’,” Assemblage 35 (1998): 8.

38. Colloquium presenters included students and staff of the GSA, in addition to invited guests. They include: Gugulethu Mthembu, Leopold Lambert, Roanne Moodley, Farieda Nazier, Kgaugelo Lekalakala, Sumayya Vally, Suzanne Hall, Olasumbo Olaniyi, Israel Ogundare, Anja Ludwig, Sarah de Villiers, Atiyyah Khan, Thelma Ndebele, Anna Abengowe, Mark Raymond, and Huda Tayob.

39. Break//Line is a project of creative resistance by and for those who oppose the trespass of capital, the indifference towards inequality and the myriad frontiers of oppression present in architectural education and practice today. The Break// Line collaborative includes Thandi Loewenson, Miranda Critchley, David Roberts, Thom Callan-Riley and Sayan Skandarajah (Breakline.studio.com) @break_line_res

40. Huda Tayob and Suzi Hall, Race, Space and Architecture: Towards an Open-Access (London, UK: 2019); See also racespacearchitecture.org (Huda Tayob, Suzi Hall, Thandi Loewenson).

41. Sara Ahmed, “A Phenomenology of Whiteness,” Feminist Theory 8, no. 2 (2007): 156.

42. Ibid., 157.

43. Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, “For Slow Institutions,” E-Flux 85 (2017), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/85/155520/for-slow-institutions/.

44. bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (New York: Routledge, 1994).

45. Thandi Loewenson and David Roberts, “Institutional Imaginaries,” 10 September 2019. Available at: https://breakline.studio/projects/institutional-imaginaries#content; This note was intended to be presented as part of a roundtable conclusion discussion on the 10th of September, however due to a problem with the internet connection in Johannesburg it was sent as an email instead. It has since been published on Break//Line’s website.

46. Loewenson and Roberts, “Institutional Imaginaries.”

47. Ahmed, On Being Included, 14.

48. Loewenson and Roberts, “Institutional Imaginaries.”

49. Ahmed, On Being Included, 3.

50. Ibid., 6.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2007. “A Phenomenology of Whiteness.” Feminist Theory 8, no. 2: 149–168. doi:10.1177/1464700107078139

- Ahmed, Sara. 2012. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bhambra, K. Gurminder, Dalia Gebrial, and Kerem Nişancıoğlu. 2018. Decolonising the University. London: Pluto Press.

- Bozdogan, Sibel. 1999. “Architectural History in Professional Education: Reflections on Postcolonial Challenges to the Modern Survey.” Journal of Architectural Education 52, no. 4: 207–215. doi:10.1111/j.1531-314X.1999.tb00273.x

- Calvino, Italo. 1974. Invisible Cities, translated by William Weaver. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Corbusier, Le 1923 1985. Towards a New Architecture. New York: Dover Publications.

- Gabru, Azraa. 2019. “Manifesto,” Honours Architectural History and Theory. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg.

- Gumbs, Alexis Pauline. 2018. M Archive. Durham: Duke University Press.

- hooks, bell. 1990. “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness.” In Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, edited by bell hooks, 145–153. Boston, MA: South End Press.

- hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

- Kincaid, Jamaica. 1988. A Small Place. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux.

- Loewenson, Thandi, and David Roberts. 2019. “Institutional Imaginaries.” 10 September 2019. Available at: https://breakline.studio/projects/institutional-imaginaries#content.

- Lokko, Lesley. 2000. White Papers, Black Marks: Architecture, Race, Culture. London: Athlone Press.

- Lokko, Lesley. 2017. “A Minor Majority.” ARQ: Architectural Research Quarterly. 21, no. 4: 387–392. doi:10.1017/S1359135518000076

- Lokko, Lesley. 2019. “African Space Magicians.” In … And Other Such Stories, edited by Yesomi Omulu, Sepake Angiama, and Paulo Tavares. New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City.

- Mthembu, Gugulethu. 2019. “The Port of Sihr.” MArch thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg.

- Nalbantoḡlu, Gülsüm Baydar. 1998. “Toward Postcolonial Openings: Rereading Sir Banister Fletcher’s ‘History of Architecture’.” Assemblage 35: 6–17. doi:10.2307/3171235

- Okoye, Ikem. 2002. “Architecture, History and the Debate on Identity in Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa.” JSAH 61, no. 3: 381–396.

- Olweny, Mark. 2020. “Architectural Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Investigation into the Pedagogical Positions and Knowledge Frameworks.” The Journal of Architecture 25, no. 6: 1–19. doi:10.1080/13602365.2020.1800794

- Osayimwese, Itohan. 2013. “Architecture and the Myth of Authenticity During the German Colonial Period.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 24, no. 2: 11–22.

- Pavita, Gloria. 2019. “Manifesto,” Honours Architectural History and Theory. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg.

- Perec, Georges. 2008(1974). Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, translated by John Sturrock. London: Penguin Classics.

- Petrešin-Bachelez, Nataša. 2017. “For Slow Institutions.” E-Flux 85. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/85/155520/for-slow-institutions/.

- Roberts, David. 2020. “Why Now: The Ethical Act of Architectural Declaration.” Architecture and Culture 8: 1–19.

- Sharpe, Christina. 2016. In the Wake. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Siddiqi, Anooradha. 2017. “Crafting the Archive: Minnette De Silva, Architecture and History.” Journal of Architecture 22, no. 8: 1299–1336. doi:10.1080/13602365.2017.1376341

- Spillers, Hortense J. 1986. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics 17, no. 2: 64–81. doi:10.2307/464747

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by C. Nelson and L. Grossberg, 271–313. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education.

- Tayob, Huda, and Hall Suzanne. 2019. Race, Space and Architecture: Towards an Open-Access Curriculum. London, UK: London School of Economics and Political Science, Department of Sociology.

- Tlali, Miriam. 1989. Soweto Stories. London: Pandora Press.

- Weisman, Leslie Kanes. 1980. “Prologue: Women’s Environmental Rights: A Manifesto.” In Gender Space Architecture, edited by Jane Rendell, Barbara Penner, and Iain Borden, 1–5. London: Routledge.

- Yusoff, Kathryn. 2018. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.