Abstract

In 1933, the construction of two twin bungalows, designed by Berthold Lubetkin, began on a site adjacent to Whipsnade Zoo. From their inception, they have been differently appreciated by architects and historians for their formal, technical, functional, material and environmental conditions. This article reappraises these buildings from broader multiple contexts involving human and non-human actors that have been part of their ecology, prioritizing categories of human wellbeing, pleasure and entertainment, and animal and environmental welfare.

Moving through the page and the terrain as spaces for critical analysis of the built environment, I consider the multiple plots – either a piece of ground, a site, a plan or the scheme of a written work – that constitute various valid frames for understanding Whipsnade bungalows. For this purpose, I reconstruct a methodological approximation to architectural criticism from feminist and cybernetic literature on “patterns” – conceived as flows of interconnection enabling associations and analogies.

Introduction

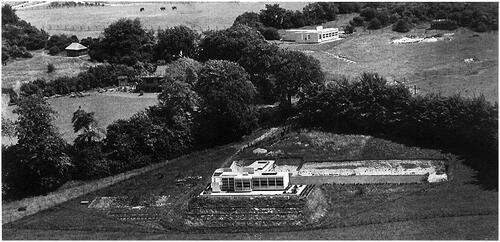

In 1933, the construction of two bungalows began on a site adjacent to Whipsnade Zoo, Bedfordshire, England ().Footnote4 Both initially designed by architect Berthold Lubetkin, they are twin buildings. Hillfield, also known as “House A,” was conceived first and built for the architect himself. After a period of intense deterioration and abandonment (1988–b. 1996), it was the first to be listed as grade II* (1988) and is being maintained. Holly Frindle, “House B” – generally appraised as the secondary version – was built for Dame Dr Ida Mann, who was at the time appointed Honorary Consulting Ophthalmic Surgeon in the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). Holly Frindle was listed (1988 as II and a. 1997 as II*) after a period of abandonment (1987–b. 2001) when it was fully restored and functional.

Figure 1 Bungalows at Whipsnade Zoo Estate, Whipsnade. Photograph c. 1936, RIBA Collections as published in “Bungalows at Whipsnade,” Architectural Review 81 (1937): 60–4. Hillfield (“House A”) is in the foreground and Holly Frindle (“House B”) is to the back. On the left center is Springfield, the house of Geoffrey Vevers.Footnote1 According to the letter Tess Vevers writes to Lubetkin, this third house was named Springfield, and was demolished in 1980 “to make way for a brick house on three levels for David, Director of Zoos, and his family.”Footnote2 Springfield might have been designed by Edward T. Salter according to the drawings kept at the RIBA collections, but no evidence of the construction of the building or the actual design has been found. Salter also designed other buildings in the Whipsnade Zoo such as the lavatories and a kiosk. Springfield was demolished and a new bigger house was built on its place.Footnote3

In 1937, only months after the buildings were completed, Lubetkin released a “series of definitions” in the Architectural Review. Expressed in negative form and written in a humorous way, these illustrated Hillfield, the first bungalow, different from general conceptions of modern architecture: not the result of hygienic, functional or geometric concerns, neither responding to the laws of physics or the conditions of the environment.Footnote5 From that moment on, this text set “House A” as a testament of a specific set of ideas that would also define future buildings designed by Lubetkin.

What are these “series of definitions” doing for these buildings, their written history and our present appreciation of them? And what do they do in conjunction with the category of “role models,” as architect John Allan would put it;Footnote6 of featuring prominently in contemporary exhibitions – such as the Museum of Modern Architecture in New York (MoMA), or the Modern Architecture Research (MARS) group exhibition at Burlington Gardens – and the main architectural publications of the time? This article reappraises the lives of these aging buildings, reflecting on how their occupations, adaptations and fetishizations – along with other modern designs – might have been affected by what this article argues to be an idealized provenance.

Lubetkin’s “series of definitions” and subsequent intellectual narratives set the buildings as models to copy in terms of layout, construction techniques, intervention in the terrain and visual impact in the landscape. However, when one returns to the origins and broader history of these bungalows, their actual design rationale included an ecological enclave to preserve, a facility for the care of animals and plants, and an access to the Zoo that would prevent land speculation.

The following text aims to rebalance the appraisal of both bungalows through interpretations of the human and animal wellbeing and environmental “patterns” of the buildings in their unique zoological landscape. “Patterns” are understood as flows of interconnection enabling associations and analogies, following the philosophy of Gregory Bateson, and recent work by Peg Rawes and Jon Goodbun. Patterns allow one to question issues of decay, individualism or collectivism throughout the material fate of these buildings, their media representation, social circumstances and personal appreciations.

A two-night stay at Holly Frindle in 2017 sparked the present article and the interest in connecting these bungalows’ ninety years of existence and their divergent histories through a wide range of agents and contexts.Footnote7 This text presents the ZSL; the media; the museums; the MARS group; English Heritage; Rogers, Stirk, Harbour and Partners (RSH-P); and Avanti Architects, along with their individual actors, the landscape, animals and plants, as reproducing specific patterns, and constituting valid frames to understand the historical significance of Lubetkin’s Whipsnade Bungalows.

Visiting the plot of the building and the plot of the page

I arrived at Holly Frindle at 9pm on a cold February Friday of 2017 with a few friends. The roads were dark and muddy, and our directions were not precise. I struggled to drive our nine-seat van up the narrow access path, presumably designed for much smaller vehicles. We crossed a field with horses, several gates across the track, one house on the left-hand side (afterwards we found out it was the one that replaced Springfield) and an abandoned shack. We were surrounded by a dense mass of trees, some of which had had branches cut off after encroaching on the road.

We awoke the following morning to the trumpeting of elephants. The place from which they were calling was designed by the same team that designed the roof over our own heads: that of Lubetkin’s. From the top of the hill we could spot some of the zoo’s animals through a fence with an overhang turning at the top. At the bottom, the large garden was bounded by a chain-link fence from where we peered at an inaccessible landscape, freely inhabited by a herd of deer.

On the last day of our stay in Holly Frindle, I felt the need to record the building in relation to its environment. I walked down the hill to the access gate. I took pictures all the way up to Holly Frindle, as a stop-motion film. I would then build a sequence of images that would present the only human access to the building. However, I was aware that this was not the way an animal or someone reading about the building would approach it — either from the sky or through treacherous alternative paths. I wondered if the first inhabitants of Holly Frindle used that path at all since I struggled with that muddy and sloppy terrain.

Despite the fact that the bungalows were referred to as houses, they were conceived and built as spaces for weekend and summer holidays. Even though at no point were these permanent homes, it is important to note that Holly Frindle, the second bungalow, was used as a temporary home by the veterinary and researchers of the Zoo; and Hillfield, the first bungalow, was occupied for a short period by Ernő Goldfinger as a refuge at the outbreak of World War 2.Footnote8

In setting up an approach to reappraising these bungalows that encompasses their lived experience, I considered the difficult position that progressive architects found themselves in the 1930s UK. In this prewar environment that promoted private housing, Lubetkin and his partnership with Tecton could only realize the design of a few houses.Footnote9 The bungalows at Whipsnade may be best understood in relation to Lubetkin’s experiments in construction techniques and to his understanding of relations between humans and the material environment than to housing projects. By explaining the architecture of these bungalows from the point of view of their multiple visitors, I aim to detach this article from a canonical perspective that, in the case of these modernist buildings, can tend to be self-referential, artificially assuming connections to architectural histories of formal, technical, functional, material or environmental endeavors, leaving so many other histories behind.

From literature on cybernetic studies I turn to “patterns” as a methodology that looks at the esthetics of communication objects, arguing that the way that this concept has been used in architectural criticism as well as in architectural history and philosophy enables analogies through different architectural expressions.

“The pattern that connects” is probably one of the most overused phrases of Gregory Bateson in the way it is described in Mind and Nature, but he meant so many things throughout an extensive career of at least forty years theorizing the term.Footnote10 Patterns are the organization of hierarchical psychic, social and material relations such as “a word in a sentence, or a letter within the word, or the anatomy of some part within an organism, or the role of a species in an ecosystem, or the behaviour of a member within a family.”Footnote11

On the one hand, patterns can be empowering – enabling communication and production. Patterns are a set of agreed structures between organisms or an organism and its environment. For example, they are involved in the intuitive choice of a path, or the choice of words that might ease communication between organisms. On the other hand, “pattern” can be thought of as “frame”: the socially agreed context that, in order to enable communication, determines what something turns out to be.Footnote12

The concept of pattern in feminist architectural histories is usually traced back to the concept of pater (father) and its French origin in English language where patron is the role model, a paternal figure that encourages, supports and guides (while often constrains).Footnote13 This applies as much to a design as to a person, and one can understand the architect also as shaped by their training and environment.Footnote14 Thus, the message, or the pattern, for Bateson, “depends upon where we sit” and our awareness of our seat.Footnote15

This approach to “patterns” connects both the situated architectural criticism of feminist traditionFootnote16 and feminist philosophy of architecture.Footnote17 In the latter, and following Agnes Denes’s work, Peg Rawes thinks of “patterns” as enabling a “‘language of perception that allows the flow of information among alien systems and disciplines’ to make ‘new associations and valid analogies possible’.”Footnote18 Rawes explains non-verbal patterns of communication as a complex ecology of esthetic relations where all levels – psychic, social and material – coexist.Footnote19 This is the complexity that Bateson saw in the visual arts: a non-verbal interrelation of life-attached patterned themes (sexual, religious, toxic, healing and others).Footnote20 In setting out a reappraisal of particular architectural projects in this article, these complexities are followed through life-attached patterned themes of environment, decay, restoration, individualism or community. This approach is not only aimed at understanding the patterned features of these themes, but to include a context of purpose to the reasoned objectives of architectural practice. Rawes argues that “failings [of reason], Bateson observes, fully demonstrate that ‘purposive rationality unaided by such phenomena as art, religion, dream and the like, is necessarily pathogenic and destructive of life’.”Footnote21 In this essay, the phenomena of human wellbeing, pleasure and entertainment, animal and environmental welfare, amongst others, are foregrounded, as they are expressed by those who influence the lived-in architecture of these buildings.

The pattern of the page is constituted by elements such as titles, grammar and vocabulary, the cover of the document, formal acknowledgements, the spaces where documents are negotiated, the media that covers the production of documents and the actors who are invited to contribute.Footnote22 The pattern is, of course, set up by a series of actors who are at the center of this analysis.Footnote23 Annelise Riles turns to Bateson’s work on pattern to think of the frames in the text as a series of analytic ideas that do not require context to be read; or to put it in the terms of Robin Wilson’s utopian and feminist work on architectural publications: each article might probably be repeating not only a constraining layout of words, heading and graphic designs, but also a patterned language that limits the definition of the project.Footnote24

The pattern of the building is set by the conditions of the plot, its maintenance conditions, its access, its ownership and funding, but also the way the archive as well as Google filters its representation. It is, again, through these patterns that the voices of different agents conflate and which I retrieve in this article.Footnote25

Life as pleasure, entertainment and wellbeing is at stake in Lubetkin’s bungalows amidst their environment, animals and people inhabiting these. However, accounts contrast depending on the situation of the architect, constructor, weekender, veterinary, curator or critic. The patterned limitations of an archive are heightened by the loss of part of Whipsnade Zoo’s archives to a fire in 1962, which contained records of routines and daily activity in the Zoo at a time of dereliction.Footnote26 The missing information also informs the deteriorating conditions of the bungalows. As most of the existing documentation on the bungalows comes from Lubetkin’s papers, and John Allan’s celebrated exhaustive monograph on Lubetkin’s life and work built through conversations between the two architects, I try to draw out accounts and positions both from and against the criteria of Lubetkin.

Peter Chalmers Mitchell, Geoffrey Vevers and Ida Mann: A Rural Zoological Settlement

Due to London’s pollution in the 1920s and the interest in studying animals in an environment where they could experience more freedom, the ZSL decided that moving London Zoo to Whipsnade was necessary. Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell, Secretary of the ZSL, would specifically see this “as a farm for growing suitable food and breeding and recuperating ground for animals.”Footnote27 In December 1926, the ZSL purchased 600 acres of terrain in Bedfordshire, north west of London. Whipsnade opened in 1931. Animals occupied large enclosures in the form that Carl Hagenbeck had inaugurated in Tierpark Hagenbeck (of course, this time without exhibiting humans).Footnote28

On December 17, 1930, Chalmers Mitchell purchased a plot of seven acres next to Whipsnade Zoo, with the “hope that the [Zoological] Society [of London] would ultimately use it as a kind of flower and bird sanctuary” and as a measure to guarantee future access to the Zoo from Dagnall, the closest town.Footnote29 The adjacent plot was purchased by London Zoo superintendent Geoffrey Vevers for the same purpose, and soon he built his own house on it: Springfield ().Footnote30

Chalmers Mitchell offered one acre of the plot to his friend Ida Mann, at the time Ophthalmological Consultant at the Zoo, for the construction of her own bungalow, Holly Frindle. Their agreement was conditioned to “revert [the bungalow] to the [Zoological] Society on the death of the survivor of the two of [them]” and to its future use by the “Scientific Employees” of the Zoo.Footnote31 Chalmers Mitchell added that Holly Frindle’s plot “shall be kept as a wild garden for the encouragement of vegetation and of all kinds of animal life natural to the vicinity.”Footnote32 In 1938, two years after the completion of the bungalow, Mann ceded her rights and Chalmers Mitchell took over.

As one of the champions of Lubetkin’s architecture, Chalmers Mitchell believed that both animals and humans would “thrive under what would seem the most unnatural conditions” as long as hygiene and security were provided.Footnote33 The modernist buildings that Lubetkin designed for London, Dudley and Whipsnade Zoos provided exactly this, as did the bungalows.

Holly Frindle is located on a gentle slope, flattened slightly to accommodate the single-storey structure. The slope continues at the south front of the bungalow, down toward the town of Dagnall. The bungalow cannot be spotted from the road – not because it is tucked between trees (of which there are few), but because the slope is not steep enough. On the north there is a steeper but shorter slope, apparently the result of flattening the terrain, that reaches the top of the beacon where the African animals of the Zoo reside ().

Figure 2 The Whipsnade Lion chalk hill figure, Whipsnade. Photograph 1938, © Historic Environment Scotland. Holly Frindle appears as a white spot in the top-right corner of the picture, right next to the Zoo enclosure delimited by masses of trees over the lion. Hillfield does not appear in the image; it would be located further down the hill on the right-hand side of Holly Frindle.

Hillfield’s plot, some meters down the hill, is steeper, and although surrounded by many trees, is visible from the road. According to Lubetkin, this plot was “forced upon him.”Footnote34 It is probable that it was a site required by the ZSL to access the Zoo from Dagnall in the future. Lubetkin accepted the plot chosen for him.

Berthold Lubetkin: Architecture “at the Point of Take-Off”

The bungalows of Whipsnade are contemporary to Lubetkin’s first commissions in London Zoo such as the Gorilla House (1932–34) and the Penguin Pool (1933–1934), to which a long list of buildings in Dudley, Whipsnade and London Zoos would follow. Lubetkin would travel to Whipsnade Zoo from his residency in Hampstead, one of the closest points in metropolitan London.Footnote35 This is currently still the way to travel from central London to Whipsnade Zoo.

Lubetkin would declare that “[Hillfield] is not a direct or functional result of a haphazard choice of site and of materials.”Footnote36 In fact, the site represented Lubetkin’s modernist understanding of the ideal relationship between architecture and the environment. According to architect John Allan of Avanti Architects, lead restorer of many of Lubetkin’s buildings, it was at Whipsnade where “Lubetkin could freely indulge his pursuit of contrast – now not only between the animal pavilions and their occupants but between the buildings as a whole and their spectacular surroundings.”Footnote37 Allan would sum up this approach quoting Lubetkin: “nature tamed not with a fist but with a smile.”Footnote38

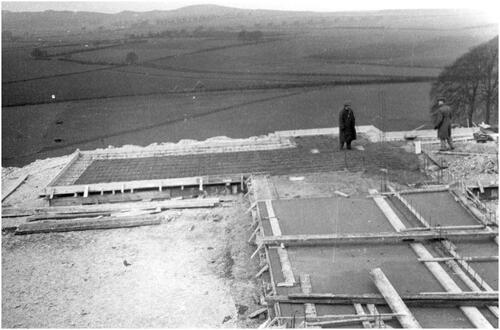

The excavation of Hillfield’s terrain shown in its picture after completion highlights its dramatic locus, with its terraced garden resembling the scars on the terrain: “[t]he designer admits also that he has not capitulated to the accidents of a site.”Footnote39 This technological achievement of dramatic earthworks contrasts with Holly Frindle’s gentle slope ().

Figure 3 Hillfield (House A), Whipsnade, foundations. Photograph c. 1934, RIBA Collections. The picture probably shows Lubetkin on the foundations of Hillfield.

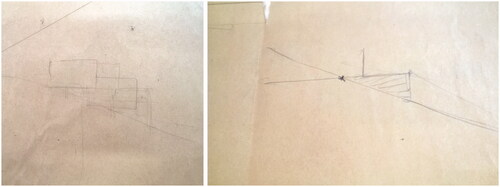

In his “series of definitions,” Lubetkin continues with some pride, referring to himself in the third person, “he excavated 800 cubic yards of dazzling chalk full of megalithic fossils, to make a flat lawn and a flat house where any Czech would have made a house in steps with a roof garden.”Footnote40 However, I would speculate that, according to the doodles next to the Survey drawing for Hillfield’s site, he might have been tempted to build the very “house in steps” that he despisedFootnote41 ().

Figure 4 Hillfield (House A), Tecton, Survey drawing of Hillfield, Whipsnade. Drawing c. 1931, RIBA Collections.

Lubetkin reinforces his authorship through his “series of definitions”: “It does not try to prove that its design grew ‘naturally’ from the given conditions.”Footnote42 In fact, Lubetkin ridicules other approaches such as a house in steps or the fauna and flora-shaped buildings which he doodles between paragraphs, “like an ordinary pumpkin, Victoria Regia, or deep-sea fish.” Furthermore, he insists that design decisions are not responses to external forces. The “flashgap plinth” – the “shadow gap between the building and the ground” – was an experiment to make the bungalows hover, to maintain the “distinction between the man-made world and the natural world” as well as refusing the “walls a damp contact with the earth.”Footnote43 This along with the “‘wing and fuselage’ plan” set the building “‘at the point of take-off’”:Footnote44

my approach is whenever possible to create buildings which are just put there as if they landed from the sky and are about to fly away.Footnote45

Hillfield was conceived as a dacha house, a Russian holiday home.Footnote46 Due to size restrictions in the Soviet era, these houses usually had a large veranda at the front, in which the inhabitants could sleep at night. Their prominent loggias, and especially their exterior fireplaces, would not make much sense otherwise. But I read these as a defensive surveillance of the land, with loggias and roof terraces offering an impressive view of the landscape that reinforces a superior human position over the landscape ().

Holly Frindle does something similar but on a flatter slope. This feature has been seen in architectural journalism as negative because “[t]here is a corresponding loss of drama, as instead of overlooking a distant valley, the house [B] is placed in a more or less conventional relationship with its foreground, in effect a gently sloping lawn.”Footnote47 As another commentator stated, Holly Frindle is “a tamer version – especially in siting”Footnote48; or as Allan himself would describe, “[t]he setting is […] better described as charming than dramatic.”Footnote49

Furthermore, people’s capacity to view the land from Holly Frindle is in direct relation to the possibility of being seen. When visitors drive along Dagnall Road looking forward to reaching House B they cannot spot it. Instead, Hillfield acts as a sort of mirage that “convert[s] the site from an auditorium into a stage; the house not so much observing the view as addressing it.”Footnote50

Lubetkin and Tecton: Hillfield as a Model

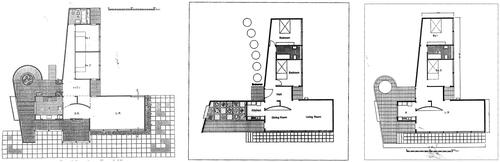

Holly Frindle was known in Tecton’s office as the twin of Hillfield: “[H]ouse B, […] smaller and more conventional.”Footnote51 From its inception, the bungalow was expected to resemble its larger sibling, Hillfield.Footnote52 Hillfield was slightly bigger, containing a loggia connecting interior and exterior space, a bigger kitchen and planting spaces, and impressive views of the landscape. The “T-shape” seems clear as the kitchen is larger. The geometry of the plan seems more fluid: nooks and corners are rhythmically interspersed through the perimeter, and the loggia breaks the limits of the house to merge with the environment.

Meanwhile, Holly Frindle has a bigger living room, is better constructed, required a smaller degree of soil engineering and is less present in the landscape. In the design process, the garden grid and the loggia disappeared. The kitchen shrank but gained direct and open access to the living room, and the dining room and master bedroom gained square meters. Rooms are different in size and the bathroom is embedded in the same geometry of the layout. These features approximate Holly Frindle to the avant-garde open-plan homes that architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright were advocating at the time.

During construction, further design modifications took place. Lubetkin’s involvement in Holly Frindle ended with an outline design. Therefore, the contractor, who already knew how to materialize Lubetkin’s ideas, “simply adapted arrangements of the first house as already constructed, including re-use of the sunscoop shuttering.”Footnote53 In this process, the singular features of Holly Frindle – the grid garden being the most obvious one – were removed, and the resulting bungalow was neither Lubetkin’s exact proposal nor Hillfield’s exact copy ().

Figure 5 Hillfield, Whipsnade, floor plan as built as drawn by Tecton; Holly Frindle, Whipsnade, floor plan as designed, drawn by John Allan following Lubetkin’s instructions and Holly Frindle, Whipsnade floorplan as built, drawing by Tecton. As presented in Berthold Lubetkin: Architecture and the Tradition of Progress (London: Artifice, 2012), courtesy of John Allan.

Hillfield contained many experiments – such as the glass door frames and the flashgap plinth – that were perfected in Holly Frindle and subsequently applied to later urban projects, from Finsbury Health Centre to High Point to Spa Green. As Mike Davies confirms, copying resulted in a higher-quality construction and subsequent comfort with improved durability and refinement of details.Footnote54

Multiple Approaches to the Bungalows

As a weekend retreat, the access to these bungalows might be significant to understand how the buildings are perceived by their multiple visitors. Whipsnade Zoo opened with unexpected traffic jams, besieged train stations in Luton and Dunstable, overcrowded omnibuses, and lots of hitchhikers and people walking miles.Footnote55 Accounts from Lubetkin and others only mention arriving by car. However, researchers and visitors probably arrived by public transport, maybe by bus to Dagnall or by train to Luton and Dunstable.

During the time it was tied to the ZSL (c. 1946–c. 1996), access to Holly Frindle crossed the Zoo.Footnote56 For this reason, Chalmers Mitchell, as well as the visiting researchers, were fully conscious on a daily basis of both the physical presence of the Zoo’s animals and the formal and contextual source of the sounds these animals made. Potential independent access to Holly Frindle from the west was planned in 1937, in case of an eventual transfer to a private owner.Footnote57 In contrast, Hillfield always had its own access from Dagnall Road, and has no visual contact with the Zoo. Visitors of Hillfield must have been more aware of the visual landscape in front of the bungalow than of the animals inhabiting the top of the hill, right behind it.

From the carpark, which is the access to the plot, there are two ways to enter Hillfield: the first is to climb up the ramp and enter into a hall on the left. The second way goes past the sunscoop corner, which focuses the sight of the visitor. Then around the kitchen, through the loggia that suddenly surrounds the visitor with the structure of the building before one more step takes the visitor into the dining room. The latter access route is a choreographed passage with spaces of compression and decompression from the landscape into the building.

In Holly Frindle’s design stage, the garden grid prevented an exterior sequential passage that was retrieved when the grid was abandoned. Access to Holly Frindle is, as in Hillfield, a choreographed passage past the sunscoop corner, around the kitchen and into the dining room. This somewhat less poetic approach to the building and its less harmonious geometry have been used to discredit the qualities of this second bungalow.

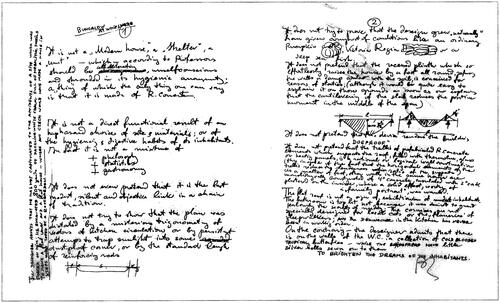

A Personal Visit to Lubetkin’s Writings

In 1937, the Architectural Review published Lubetkin’s “series of definitions” as described in the IntroductionFootnote58 (). My first encounter with this text was through the monograph on Lubetkin’s oeuvre (originally published in 1992) written by Allan.Footnote59 Allan’s book presents both bungalows in a subheading titled “Testament,” where he describes the bungalows and their influence in future designs of Lubetkin. “Testament” is followed by “Assimilation,” where later house designs of the firm rationalizes previous successful experiments. Hillfield is here defined as a “Utopian time capsule” that represents the ideals of this period of heroic modernism at a standard or pattern difficult to achieve in relation to construction techniques and the environment.Footnote60

Figure 6 The Whipsnade “series of definitions,” Lubetkin’s original manuscript. As presented in Berthold Lubetkin: Architecture and the Tradition of Progress (London: Artifice, 2012), courtesy of John Allan.

Moving through the paragraphs of Lubetkin’s “series of definitions” can be understood as entering an architectural site through the imagination of the architect. It transcended the qualities of one building, to construct a set of statements that might be generalized to other architectures, not because it said so, but because the frame of the page is much more abstract than the earthy, topographic, life-filled site of the building itself. This set of definitions acquired the meaning of “manifesto” through time and has been referred to as such by Allan. The text rejects a purely structural, formal, material, functional or environmental explanation of Hillfield, reinforcing the autonomy of the designer.

The manifesto starts and ends in capital letters: “BUNGALOW AT WHIPSNADE […] TO BRIGHTEN THE DREAMS OF THE INHABITANTS [himself].” It is a two-page handwritten text, with a side note on the left, and corrections through its length, interspersed with simple drawings that do not fit in it. It looks impulsive, disordered. Its line spacing reduces at the end to fit in more text, and lines are broken. As if written in conclusion, to make sure the receiver understood the order of the text, a circled “1” and a circled “2” appear on top of each block of text. This text was published in the Architectural Review in a serifed bold stylized font, somehow reproducing Lubetkin’s handwriting.Footnote61

Somehow fixed in the moment of Lubetkin’s impulse, this page does constitute a utopian time capsule to which any building will never hold to. But as the buildings decay, I wonder whether the page, and its contents, has also been decaying, offering no possibility of their own restoration.

The Media: Detachments from the Environment

Both the Architectural Review and Allan’s book present an edited transcription of the manifesto to improve its readability. They removed some of its word and visual play, such as the relation between a rejection of natural growth and “a compost of conditions” (my emphasis) or the definition of the flashgap plinth – the fissure between the building and the terrain – as “DOGPROOF.”Footnote62 Despite the intentional humorous tone that was edited out, I take Lubetkin’s statements contained in the manifesto very seriously because it was destined to present Hillfield as a design free of constraints, utopic, thus constituting a model, a pattern. In this article, I argue that Lubetkin’s appreciations of both bungalows have conditioned their subsequent use more than the material, spatial and site-based characteristics of the buildings themselves.

The Architectural Review accompanied the manifesto with a four-to-one ratio of information on the two houses.Footnote63 Hugh de Cronin Hastings, Editor at the time, was in close contact with Lubetkin and his environment. I presume that, as well as in Allan’s book, he had been directing any edits of his manifesto as well as the appearance of his buildings in the publication. Other publications of the time included similar appraisals of the bungalows. In 1937, The Architect’s Journal devoted four pages to Hillfield and one to Holly Frindle. They did not publish a single word about the second house except for the title “Two Bungalows at Whipsnade” and in footnotes.Footnote64 Further publications such as Architect & Building News, L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui and others were similar. The RIBA photographic collection only holds pictures of the construction process and models of Hillfield.Footnote65 Pictures of Holly Frindle once built are scarce.

The MoMA dedicated two plates to Hillfield and one to Holly Frindle in the catalogue of the exhibition “Modern Architecture in England” in 1937.Footnote66 This publication has been revisited by Mark Crinson in his broad historical analysis of internationalism.Footnote67 The approach of the curator of the exhibition, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, was premised on an exhibition in the MoMA in 1932. The latter, co-curated by Hitchcock and Philip Johnson and accompanied by the catalogue International Style, epitomized for Crinson the US absorption of the International Style. This absorption removed the international complex values closely associated with world peace and wellbeing under socialist ideas, and transforming the international “style” into a form of global consumerism:Footnote68

Never – or rather, hardly ever – was enough visual information included to lead the viewer into consideration of the specificity of a site, the qualities of a climate, or the effects of a terrain. The architecture of the International Style was not to be in dialogue with these matters because they were simply too specific, too conditional or too local.Footnote69

Meanwhile, modern architecture was presented by their authors as hygienic, helping animals thrive as much as it helped humans, to the extent that penguins or gorillas would be better off in geometrical constructions than in a reproduced construction of the Antarctic or the forest. The same discourse would apply to Whipsnade bungalows.

Subsequent publications also neglected Holly Frindle. For example, Nick Dawe published four pictures of Hillfield and one of Holly Frindle in The Modern House Today.Footnote70 Academic interest also focuses on Hillfield, such as Susan MacDonald’s essay.Footnote71 Finally, Avanti Architects wrote a report for the protection of each of the bungalows in 1988, before they were listed. Hillfield’s report was exhaustive in its photographic and textual descriptions, and little reference was made to its twin bungalow. On the other hand, Holly Frindle’s report, commissioned by the ZSL, describes the context of the bungalow through its twin, to the extent that most of the text is directly copied from Hillfield’s report. Holly Frindle’s report also contained lots of pictures of Hillfield that are used to highlight the importance of Holly Frindle only as a second version.

Tess Vevers, Kenneth Powell and Mike Davies: A Social Construction of Decay

After Chalmers Mitchell died in 1945, the ZSL should have inherited the bungalow, but instead they purchased it so as to get rid of the particular conditions they had signed with Chalmers Mitchell. Nevertheless, despite this purchase, the bungalow ended up hosting researchers as Chalmers Mitchell wanted, although it did not become a sanctuary for birds and wildlife. Holly Frindle was adapted to the needs of the new inhabitants: double-glazed windows; a second, bigger kitchen; a chimney in the living room; and awning boards over the living room’s terrace, all presumably added in the 1960s.Footnote72

Meanwhile, Hillfield preserved its original features because the house has never changed from its weekend use. After Lubetkin gave the house as a present to his friend (and Soviet spy) Prascovia Schubersky and her husband Dr Frank Yates in 1938, the latter kept it until it became uninhabitable in 1987. The house was purchased by Mike Davies in 1996, two years after Yates died.

Whilst scarce, the accounts of Holly Frindle during the time it was used by the Zoo researchers do show concerns for its material state. In 1962, when Holly Frindle was already owned by the ZSL, Geoffrey Vevers, Superintendent of the Zoo, described to Lubetkin the terrible state of Whipsnade Zoo at that time.Footnote73 In May 1987, Tess Vevers, his daughter, expressed to Lubetkin her concerns about the state of Holly Frindle:

Your bungalow [Hillfield] […] still looks fine as the Yates have kept it in good order […] Holly Frindle, on the other hand, is much neglected and looks very sad.Footnote74

One year later, the bungalow was closed “when the building became uninhabitable and service supplies were disconnected.”Footnote75 The same perception continued among those who reported on the bungalow’s decay. For instance, Kenneth Powell wrote that “[b]oth houses have been very well restored in recent years – ‘Holly Frindle’ from a state of advanced decay.”Footnote76

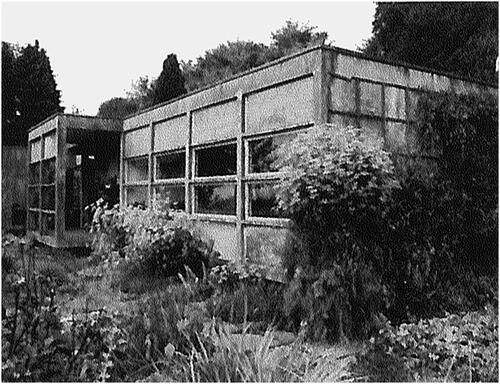

However, archival evidence might prove that perceptions about the state of the bungalows were a bit biased. For example, pictures taken around 1975, when the Yates were still living in Hillfield, show humidity stains all over the walls and window frames, and a general shabby appearance (). Contemporary pictures of Holly Frindle, when the veterinary of the Zoo was staying there, show a cleaner and more homogeneous surface, and generally better conditions.Footnote77 Furthermore, pictures of Holly Frindle in 1988 () do not show significantly worse conditions than Hillfield as it appeared thirteen years earlier.

Figure 7 Hillfield (House A), Whipsnade, front facade. Photograph by John Allan, 1975. As published in Berthold Lubetkin: Architecture and the Tradition of Progress (London: Artifice, 2012), 189, courtesy of John Allan.

Figure 8 Holly Frindle (House B), Whipsnade, front façade with Berthold Lubetkin on a visit with John Allan one July day in 1988. Courtesy of John Allan.

The idea that Holly Frindle’s state might have been denigrated more than necessary was confirmed by Mike Davies. He purchased Hillfield in 1996 and persuaded his company, RSH-P, to do the same with Holly Frindle. Hillfield was, at that moment, in even worse condition than Holly Frindle mostly because nature had literally occupied it: animals had eaten the insulating cork and other fixtures, and it was almost impossible to spot the bungalow beneath the climbing plants covering it.Footnote78

John Allan, English Heritage and the Environment: Reporting and Transferring Care

Both bungalows were indeed in a state of disrepair in 1988, one year after Vevers praised Hillfield’s state and pointed out Holly Frindle’s state of decay (). Allan’s report of 1988, commissioned by the ZSL, stressed the need to keep using Holly Frindle as a home, while the priority at Hillfield was the preservation of the building itself:

Holly Frindle, however well restored, would not be very worthwhile as an empty monument. It must become a fully used, heated, cared for and lived-in home. The special character and charm of this building can then again be enjoyed by residents and visitors alike.Footnote79

[Hillfield] is far and away the most architecturally interesting, artistically accomplished and historically significant [of Lubetkin’s houses] […] the key requisites for securing the future of this building would seem to be the formulation of a viable use, [and] the provision of adequate funds.Footnote80

On September 1, 1988, Holly Frindle was listed as grade II by English Heritage, while Hillfield and the Elephant House obtained grade II*. This segregation was in line with the position of Allan and Lubetkin, who claimed that “[i]t was generally agreed that Holly Frindle was of less merit than the larger house, but that as they had been designed and built in tandem they deserved to be preserved as a pair.”Footnote81 The process of listing the buildings involved correspondence between Sasha Lubetkin, John Allan, English Heritage, the ZSL and Professor Rod Hackney (president of the RIBA) mostly concerning the listing of Hillfield. This correspondence was finalized by a letter from the Listing Branch to Allan that highlighted the interest in Hillfield:

You will be glad to know that the building [Hillfield] was listed on 1 September 1988 in grade II* having been judged to be of special architectural or historic interest. I enclose a copy of the list entry for the bungalow and also for other Lubetkin buildings listed at the zoo at the same time, which may be of interest to you; (see the emphasis on the main bungalow).Footnote82

Described as “[a]n important house by a major architect, built for his own use,” English Heritage listing for Hillfield has no reference to Holly Frindle.Footnote83 Meanwhile, drawing on Allan’s monograph on Lubetkin, Holly Frindle is described as having some features renewed and as part of a set of two bungalows.Footnote84 Quoting Allan, English Heritage refer to the importance of the construction of these bungalows for the development of construction techniques in Highpoint II and Finsbury Health Centre.

Mike Davies, a Calf, a Lion and Some Mold: “Dangerously in Harmony with the Natural World!!”

Davies has been heroically preserving Hillfield for more than twenty years.Footnote85 It is uninhabitable in winter, and requires, along with its garden, a great deal of attention.Footnote86 Moreover, every work of repair must use original materials or exact replicas in order to preserve the original design features. This is not because of the differential in listings, as Holly Frindle reached grade II* before its restoration. Holly Frindle was conceived by RSH-P as a facility for the recreation of employees and has been working as such for years. Holly Frindle was fully restored with certain fixtures or construction materials that were not original but similar, and more convenient for maintaining the function of the bungalow, even in winter. This was possible thanks to the lesser importance given to its design. It is not without some irony that, despite its neglect, Holly Frindle was given a II* listing ten years later, has been fully restored and is fully functional.Footnote87

More than fifty years later, a new solution was built after RSH-P purchased the bungalow: Hillfield’s access was extended through a steep and winding road. The fact that the new inhabitants stopped arriving via the Zoo could have made them less aware of the ecology they were living in, especially the nearby animals. These are just inches away. They can be spotted through a fence with an overhang turning at the top to prevent the animals from trespassing.Footnote88

This awareness can be clearly identified in a personal anecdote Mike Davies related to me in 2017: Davies once heard a lion in Hillfield’s garden. At that moment, fortunately, he was inspecting the roof. The situation was utterly frightening, and he feared to move. The sound seemed very clear and close. Some minutes later, the roar started to fade. Little by little, the wind changed direction and Davies realized that the lions were in fact still on the other side of the fence. Davies also explained to me how the animals physically inhabit the bungalow from time to time. A picture of Holly Frindle from 1975 shows a calf in the foreground that was being nursed by the vet before being released to the Zoo park.Footnote89 Some animals manage to get through into the plot, become trapped in it and, if it is winter, die after days of starvation. Whilst a deer would not die because there is plenty of grass to eat, most of the animals of the Zoo are living in an alien environment and develop a relation of absolute dependence with their human caregivers.

The Covid-19 crisis, Davies argues, has stopped the necessary constant maintenance of Hillfield, where the recently cleaned surfaces are again covered in black mold and green pollen: “Lubetkin would have hated the nature which has invaded the site – and even the trellis for climbing plants added by Dr and Mrs Yates to the south end of the living room […] beginning to look dangerously in harmony with natural world!!”Footnote90

Who Sits “Comfortably” by the Sunscoop Corner?

Hillfield’s spaces have been documented to the extent of fetishization. The book cover of the exhibition catalogue “Un Moderne en Angleterre” at the Institut Français D’Architecture in Paris from June–September 1983 () shows an artistic reproduction of Dell & Wainwright’s picture of 1936. This is an image of a woman (probably Margaret Church) taken from Hillfield's roof, sitting down on the sunscoop corner.Footnote91 sitting down on the sunscoop corner. The image – along with the title of the exhibition – depicts a particular lifestyle: a smartly dressed woman in black with a hat that covers one of her eyes sits down on a white welded metal chair (not particularly comfortable-looking), in a relaxed position with a book on her lap and looking pensively at the entrance of the house. This image represents an idea of modernity and progress that is well ingrained in current imaginaries of wellbeing that believe in humans thriving as isolated individuals – in this case, she does not seem to be caring for anyone else except herself. At the same time, her pose is superficially performative: the subject of wellbeing seems more concerned with displaying pleasure than feeling it.

Figure 9 Cover of the catalogue of the exhibition “Un Moderne en Angleterre” held at the Institut Français D’Architecture (Paris, June–September 1983) showing Hillfield (House A), Whipsnade, sunscoop wall patio in a photomontage from the original of Dell & Wainwright’s picture of 1936; fair use.

Hillfield is hard work, there are very little moments of sitting and contemplating according to Mike Davies’s accounts. As soon as one has finished restoring one end of the railing, one has to start the other end again. In Dr Frank Yates’s obituary, Michael Healy, Professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, argued for the value of Yates’s individual efforts to maintain the bungalow:

He [Dr Yates] was very fond of this building and particularly of its garden, and his long drawn out efforts to keep it waterproof have been severely undervalued by press reports in recent years.Footnote92

The private character of Hillfield has not promoted any public display of life in it, nor has it helped the difficulties of living in it. Privacy and hard work might be two sides of the same pattern.

RSH-P Visitors’ Weekend Retreats

RSH-P opened up Holly Frindle to many visitors after its rehabilitation. This increased Holly Frindle’s visibility online, which shows very different images from the one described earlier in Hillfield. These images usually depict the lawn in front of the house, people playing, eating, drinking, chatting, using the swing in the oak in the middle of the garden or just relaxing. An image drew my attention from Angela Tobin’s blog.Footnote93 It is from 2012 and depicts a big gathering in the bungalow with four children, five women, two of them pregnant, and four men. It is not the happiness that they express, which might be performed or not, but the setting of the image that I found quite representative. The picture does not show the bungalow but rather its garden. According to its point of view, the camera must have been held on the exterior terrace, posing the bungalow behind the camera’s lens for the wellbeing of the smiling group and not vice versa. The picture is accompanied by others that showed the kids next to a metal shack by Springfield, on a fence or in the garden. It is also followed by a text which, in its apparent triviality, shows a range of activities that probably correspond to a bungalow for weekend retreats:

As much as I love London, it is always a treat to get away for a break especially in the countryside. We went to the Zoo, played camp and explored, petted the horses, saw the wallabies at the end of the garden, (had a take away and watched x-factor!) You know, all the lovely relaxing things you can do when you’re not at home.Footnote94

Conclusion: Reclaiming Whipsnade Bungalows’ Hidden Patterns

The MoMA showed Hillfield isolated from its surroundings in 1937. One year later, the MARS group presented an aerial view of the bungalow and its surroundings as a wallpaper of their exhibition “New Architecture” in Burlington Gardens. Lubetkin did not participate in the materialization of the exhibition. However, he was involved in the discussions of previous small exhibitions of the MARS group that led to this and, if dismissive of MARS as a forum for design ideas, he was strongly connected to it in terms of “socially directed ideals.” Footnote95 “New Architecture” presented a wide range of criticisms of the current situation and new ideas on the built environment, from dwelling to leisure, education, medical services, work, transport and landscape.Footnote96 Hillfield was featured in the section on “Architecture in the Landscape,” next to a real-size pergola, as the epitome of the relation between architecture and nature.Footnote97 The following words were inscribed over the west-side darkened trees where the current road passes by:

Architecture – Garden – Landscape: The Architecture of the house embraces the garden. House and garden coalesce, a single unit in the landscape.Footnote98

However, it is Holly Frindle in which technique was perfected, the relation to education, medical services and work was further rehearsed from its inception, as well as the care for the landscape and its relation to leisure and wellbeing – in fact, the exhibition included London and Dudley Zoos as examples of modern leisure. Holly Frindle’s collective use was managed by the services of the ZSL and later by RSH-P. Even though this effort seems to go unnoticed, it is strikingly representative of a life in community that maintains the socialist, internationalist, peaceful values that the MARS exhibition presented and that Crinson argues were ignored in the dissemination of modern architecture in the USA. I speculate that the value that Lubetkin and subsequent designers and architectural historians gave to Hillfield and Holly Frindle might have dramatically conditioned their use and are at odds with their aforementioned contextual ideals.

I have turned to the MARS exhibition in this Conclusion as a piece of evidence that agglutinates patterns beyond Lubetkin’s architecture and that of his contemporaries. In Holly Frindle there appear collective and interdependent patterns where the landscape is mildly controlled and cared for in order to thrive, as Lubetkin’s architectures did for the animals in Whipsnade Zoo next to them, or the collective management of the building and garden for ZSL’s researchers and RSH-P’s employees.

In contrast, individualistic, hard work patterns appear through Hillfield, presenting the difficult, strenuous care of a building in a permanent stay of decay, isolated and with an access unrelated to its origins that tied it to the Zoo. The building imposes an individual figure on the terrain.Footnote99

Some patterns have been consistently ignored. However, their remains are still to be found in the archive and on site. I suggest that acknowledging these patterns and also the values associated with each of their lives and moments offers a critical interpretation and reappraisal of these bungalows. The sort of decay that the buildings have manifested may be equated with other material wearings: to paper, Lubetkin’s words and printed publications. It is probably high time we accept that all of these texts decay and transform them into something much more productive and life-giving, that is a life in community and in harmony with the environment.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Joe Crowdy and Sabina Andron for their support and especially Peg Rawes for her guidance and encouragement. The author is most grateful to the two peer-reviewers who offered very generous advice, Ben Campkin for his comments, Mike Davies and John Allan for their immensely valuable insights and criticisms and the archivists at ZSL and the RIBA for their amazing work. Foremost, the author wants to highlight Suzanne Ewing’s epic editorial work with this article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Albert Brenchat-Aguilar

Albert Brenchat-Aguilar is a Lecturer (teaching) at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London. Previously, he co-curated the public programme and publications of the Institute of Advanced Studies, UCL, edited the digital platform Ceramic Architectures and worked as an architect in Bombas Gens Arts Centre. He is a CHASE-funded PhD student at Birkbeck and the Architectural Association.

Notes

1. John Allan, “House Style,” in Berthold Lubetkin: Architecture and the Tradition of Progress (London: Artifice, 2012), 180.

2. RIBA Collections, London, LUB\4\7\1-4, Correspondence between Lubetkin, from Princess Victoria Street, Bristol, and Tess Vevers, from Holly Frindle bungalow, Whipsnade between May 1987 and July 1988.

3. Correspondence with Mike Davies, founding partner at Rogers, Stirk, Harbour and Partners and owner of Hillfield, April 2020. For details on dates and personalities involved in these buildings please consult Appendices 1 and 2.

4. The limit of the county, however, runs through the fence separating the plots: Holly Frindle is in Bedfordshire and Hillfield is in Buckinghamshire. I have not found any indication that this has been a reason for the buildings to be preserved differently. RIBA Collections, London, LUB\11\9\1-5, Correspondence between Lubetkin, from Upper Kilcott Farm, David Verey, from Cirencester, and Nikolaus Pevsner, from Penguin Books, London; tss., February 19, 1965–January 12, 1967. In a letter to Nicolaus Pevsner on November 4, 1966, Lubetkin asserts that the contract for the houses was signed the day after the Reichstag fire (February 28, 1933).

5. “Bungalows at Whipsnade,” Architectural Review 81 (1937).

6. Allan, “House Style,” 180. He would place these bungalows, along with Bentley Wood of Chermayeff and Willow Road of Goldfinger, as “Continental role models.”

7. My own voice is interspersed through the text (in cursive indented paragraphs) along with those who restored or inhabited the buildings at any point of their history. A visit and stay in Holly Frindle took place on February 3–5, 2017.

8. The Ernő Goldfinger Papers at the RIBA Collections. GOLER\408–409.

9. A broad and comprehensive account of Lubetkin’s relation to social and private housing can be found in Allan, “House Style.” Allan describes the contradictory position of Lubetkin on housing in a 1930s UK where the government facilitated the construction of private housing. “[T]he individual house, as an autonomous artistic object and viewed through the prism of the English class system, presented contradictions for the ‘progressive’ architect of the 1930s.” For Lubetkin, the individual house would function best as a model for clients and speculative builders than as objets d'art on their own. Allan, “House Style,” 161–3.

10. Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000). Internal patterns, external patterns, patterns of patterns or patterns as hierarchical relations (or levels), patterns as difference, patterns of verbal and non-verbal, iconic and “uniconic” communication, patterns as the connection of the part to the whole, patterns as redundancy, meaning, form, restraints and, in some cases, pattern as matter. Not only are these classifications categories on their own but they get entangled in the analysis of human and non-human relations.

11. Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 406.

12. Ibid.; “Restraints of many different kinds may combine to generate this unique determination.” For this reason, the term pattern and frame might be interchanged in the text.

13. John Goodbun, “The Architecture of the Extended Mind: Towards a Critical Urban Ecology” (Ph.D. thesis, University of Westminster, 2011).

14. Katie Lloyd Thomas, “Introduction: Architecture and Material Practice,” in Material Matters: Architecture and Material Practice, ed. by Katie Lloyd Thomas (London: Routledge, 2007), 5–6.

15. Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 413.

16. For more information see the following works of architectural criticism: Jane Rendell, Site-Writing: The Architecture of Art (London: IBTauris, 2010); Robin Wilson, Image, Text, Architecture: The Utopics of the Architectural Media (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015).

17. In the form that philosophers such as Peg Rawes, Elizabeth Grosz or Hélène Frichot pursue architecture in its environmental and biopolitical relations.

18. Peg Rawes, Relational Architectural Ecologies: Architecture, Nature and Subjectivity (New York, NY: Routledge, 2013), 46 in relation to the work of Agnes Denes.

19. Ibid. Rawes turns to non-verbal patterns of communication in the arts and design to define “an ecology of [aesthetic] relations that exist simultaneously on psychic, social and material levels.”

20. Ibid., 46–7.

21. Ibid., 47 quoting Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 146.

22. Annelise Riles, The Network inside Out (Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press, 2000).

23. Ibid., 18.

24. Annelise Riles, “Infinity within the Brackets,” American Ethnologist 25 (1998); and Robin Wilson, “‘Now, This Square Is Beautiful’: The Utopic Report of Lacaton & Vassal,” in Image, Text, Architecture: The Utopics of the Architectural Media (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2015), 101–26. The latter might remind the reader of Christopher Alexander’s work on Pattern Language, the prescriptive quality of which – and consequent multiple ontological and epistemological problems – would point us to the opposite direction of the meaning of pattern as an analytic tool specified in this article. It is true, however, that the analysis of patterns might be perceptually constructed but this discussion might belong to a different article. For the first, see Michael J. Dawes and Michael J. Ostwald, “Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language: Analysing, Mapping and Classifying the Critical Response,” City, Territory and Architecture 4 (2017): 17.

25. Robin Wilson, “‘Now, This Square Is Beautiful’,” 101–26. He refers to the tension between the work of Elizabeth Grosz and that of Louis Marin who clash in their understanding of the utopian work and the possibility of the unexpected. It also induces ideas around the work of science fiction writers Ursula K. Le Guin and Octavia E. Butler when they refer to The Day Before the Revolution or Martha’s Dream and explain that both their works do not present immediate templates of a better future but generate a seed for future transformations of the world.

26. Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton, NJ; Oxford, UK: Princeton University Press, 2009). See particularly Chapter Two, “to understand an archive, one needs to understand the institution that it served.” Ibid., 25.

27. John Allan, Berthold Lubetkin: Architecture and the Tradition of Progress (London: Artifice, 1992), 213.

28. The purchase of Hall Farm was made for £13,480 12s 10d.

29. Zoological Society of London Library, London, GB 0814 WAA; WABJ, letter written by Chalmers Mitchell to Julian Huxley in 1937.

30. It is not clear whether Lubetkin’s purchase of the plot was also motivated by this intention, but it might have been the case considering the difficulty of accessing the top of the beacon only through Springfield and Holly Frindle.

31. Peter Chalmers Mitchell, Codicil to the Will Dated 16th Day of May 1945 of Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell, Knight, C.B.E, F.R.S., GB 0814 KBAA (London: Zoological Society of London Library, 1945).

32. Ibid.

33. Peter Chalmers Mitchell, My Fill of Days, by Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell (London: Faber & Faber, 1937), 362.

34. “Bungalows at Whipsnade.”

35. At the time, probably 12 Canon Street according to letters sent at the time from this address now archived in the RIBA collections.

36. “Bungalows at Whipsnade,” 60.

37. Allan, Berthold Lubetkin, 213

38. Ibid.

39. “Bungalows at Whipsnade,” 60.

40. Ibid.

41. RIBA Collections, London, PA117/1, Survey drawing for the site of Hillfield, Whipsnade, Bedfordshire, by Tecton, c. 1931. There are three drawings next to the survey representing houses in steps.

42. “Bungalows at Whipsnade,” 60.

43. John Allan, Berthold Lubetkin (1901–90), 1994, Pidgeon Digital, https://www.pidgeondigital.com/talks/berthold-lubetkin-1901-90-/ (accessed February 28, 2017).

44. London, RIBA library, LUB 4/5/16, John Allan et al., Notes of a Meeting at the Zoological Society of London held on July 15, 1988. Second quote is John Allan quoting Lubetkin.

45. Berthold Lubetkin, “Interview,” Architects Journal 16 (1987): 32.

46. Nikolaus Pevsner, Elizabeth Williamson, and Geoffrey K. Brandwood, Buckinghamshire (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994), 110. See also RIBA cataloguing of this building: https://www.architecture.com/image-library/RIBApix/image-information/poster/hillfield-house-a-whipsnade-zoo-estate-whipsnade-the-entrance-terrace-and-circular-patio-seen-from-t/posterid/RIBA8687.html (accessed 10 January 2020).

47. Allan, Berthold Lubetkin, 186.

48. Malcolm Reading, Lubetkin & Tecton: An Architectural Study (London; Triangle Architectural, 1992), 47.

49. Allan, Berthold Lubetkin, 186.

50. Avanti Architects, The Bungalow on the Beacon: A Case for Restoration of Berthold Lubetkin’s House at Ivanhoe Beacon, Whipsnade (London: Avanti Architects, 1988), 5.

51. Reading, Lubetkin & Tecton, 47.

52. Allan, Berthold Lubetkin, 186.

53. Ibid., 187.

54. Mike Davies in conversation with the author on March 24, 2017.

55. Dunstable train station was probably also crowded. “Crowds Besiege Omnibuses,” Daily Mail, May 26, 1931, p. 9, Gale Primary Sources; and A Special Representative, “Amazing Traffic Chaos at New Zoo,” The Daily Telegraph, May 26, 1931, p. 9, Gale Primary Sources.

56. In 1966, Lubetkin told Pevsner that “I have not been there for years, but I believe the only access to them is through the Zoo (Near Dr. Vevers cottage). When I owned one of them, I had the right of way through the Zoo.” RIBA Collections, London, LUB\11\9\1-5, Correspondence between Lubetkin, from Upper Kilcott Farm, David Verey, from Cirencester, and Nikolaus Pevsner, from Penguin Books, London; Tss. 19 Feb 1965 - 12 Jan 1967. However, Davies affirms that the access to Holly Frindle was continued from the one to Hillfield, and the plans for the Vevers cottage in 1930, as well as the map of the area of 1970 in Digimaps, already show the road to Hillfield without the extension to Holly Frindle.

57. Access to Holly Frindle is acknowledged through the Zoo on September 17, 1937 as an alternative route (proposal drawing sent to Julian Huxley on October 4, 1937), but it would have been too costly (£150).

58. “Bungalows at Whipsnade.”

59. Allan, Berthold Lubetkin, 185. The term “manifesto” is preserved throughout the text and without quotation marks to improve readability.

60. Ibid., 180–9 and 190.

61. “Bungalows at Whipsnade.”

62. Allan also presents a reproduction of the document sent by Lubetkin. Allan, “House Style,” 185.

63. “Bungalows at Whipsnade.”

64. “Two Bungalows at Whipsnade,” The Architects’ Journal 85 (1937): 299–303.

65. Understandable considering Lubetkin’s detachment from the construction of Holly Frindle.

66. Museum of Modern Art, Modern Architecture in England (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1937), plates 60–1.

67. Mark Crinson, Rebuilding Babel: Modern Architecture and Internationalism (London; New York, NY: IBTauris & Co. Ltd, 2017).

68. Ibid., 142–3. He describes the exhibition at MoMA as the epitome of the US absorption of the International Style, when it lost all of its ideals and became simply a formal construction.

69. Ibid., 148.

70. Nick Dawe, The Modern House Today (London: Black Dog, 2001).

71. Susan MacDonald, “Long Live Modern Architecture. A Technical Appraisal of Conservation Work to Three 1930s Houses,” Twentieth Century Architecture 2 (1996).

72. Further images of these details can be seen in Avanti Architects, The Bungalow on the Beacon.

73. RIBA Collections, London, LUB\11\7\7, letter by Geoffrey [Vevers], from Whipsnade, Beds, to Lubetkin; ms., signed on January 29, 1962. The letter was written in 1962, the very same year that the archive of Whipsnade Zoo was lost in a fire: “Whipsnade is in such a mess that I do not like to ask people to come to see us – Everywhere there are [illegible] up buildings that would make you shudder – ‘lavatorial erections’ of the worst possible kind […] Nobody seems to care anymore or has any consideration for the aesthetics of the place.”

74. RIBA Collections, LuB\4\7\1-4.

75. Avanti Architects, The Bungalow on the Beacon, 4.

76. Dawe, The Modern House, 44.

77. Allan, Berthold Lubetkin.

78. Mike Davies in conversation with the author on March 24, 2017. See also Holly Frindle (House B), Whipsnade, front elevation, photograph of c. 1997 in Kenneth Powell, ‘Beyond the Fringe’, in Structure and Style, ed. by Michael Stratton (London; New York: E&FN Spon, 1997), 80.

79. Avanti Architects, The Restoration of Holly Frindle Bungalow at Whipsnade Park, Bedfordshire: Report to the Zoological Society of London (London: Avanti Architects, 1988), 55.

80. Avanti Architects, The Bungalow on the Beacon, 14.

81. RIBA Collections, London, LUB\4\5-7, Correspondence and notes relating to the restoration of bungalows at Whipsnade, designed by Lubetkin and Tecton; tss. & mss., 1987–88.

82. S. Cox, “Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest: Bungalow at Whipsnade,” RIBA Collections, September 21, 1988.

83. “House Adjacent to West Boundary of Whipsnade Zoo,” Historic England, https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1300803 (accessed March 5, 2020).

84. “Holly Frindle Bungalow, Whipsnade,” Historic England, https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1321291 (accessed March 5, 2020).

85. MacDonald, “Long Live Modern Architecture.”

86. Roderick Gradidge, “A Feeling for Restoration,” Country Life 186 (1992). This is a critical article about Hillfield with a clear agenda, but its picture and comments leave no room for doubt: “if one is to retain Lubetkin's machine-age conception at Hillfield, it will be necessary to put it back to the state that it was in when it was illustrated in all those books that publicised the New Age. This would have to be undertaken by an enthusiast who is willing to give up all his spare time to the restoration, treating Hillfield as he might treat the restoration of a pre-war Alfa-Romeo.”

87. Michael Stratton, Structure and Style: Conserving Twentieth Century Buildings (London; New York, NY: E & FN Spon, 1997), 80.

88. Lucy Pendar describes the original fence supplied by the Darlington Fencing Company that assured inhabitants that “the inmates could not escape.” Lucy Pendar, Whipsnade Wild Animal Park “My Africa” (Dunstable: The Book Castle, 1991), 12.

89. See Allan, Berthold Lubetkin, 186 for an image of Holly Frindle in its setting showing the front facade (photograph by John Allan, 1975). As Allan specifies: “Holly Frindle was being used by the Zoo vet who happened to be nursing the calf at the time in the protective surroundings of the bungalow garden before it was released back into the zoo park.” Email correspondence between John Allan and the author, 2018.

90. Correspondence between the author and Mike Davies, 2020.

91. Correspondence between the author and John Allan, 2021.

92. Michael J. R. Healy, “Frank Yates, 1902–1994: The Work of a Statistician,” International Statistical Review 63 (1995): 272.

93. Angela Tobin, “The End of the Summer,” 2012, http://thisiswiss.blogspot.com/2012/09/the-end-of-summer.html (accessed March 7, 2017).

94. Ibid.

95. MARS group, New Architecture: An Exhibition of the Elements of Modern Architecture (London: New Burlington Galleries, 1938). For a comprehensive account of Lubetkin’s relation to MARS group, see Allan, Berthold Lubetkin, 315–22. “Lubetkin certainly did not look to MARS as a forum of design ideas or debate […] The MARS Group did at fist provide an outlet for the socially directed ideals with which he had embarked in English practice but which were not altogether fulfilled in Tecton's earlier commissions.” He had effectively abandoned MARS well before 1938.

96. John R. Gold, “‘Commoditie, Firmenes and Delight’: Modernism, the Mars Group’s ‘New Architecture’ Exhibition (1938) and Imagery of the Urban Future,” Planning Perspectives 8 (1993): 362.

97. This section of the exhibition stated: “There must be no antagonism between architecture and its natural setting, The Architecture of the house embraces the garden. House and garden coalesce, a single unit in the landscape.” MARS group, New Architecture, 20.

98. Ibid., 20.

99. As John Allan would put it, “Any account of Lubetkin’s Whipsnade bungalow must begin with the drama of its site.” Allan, Berthold Lubetkin, 181.

100. Avanti Architects, The Restoration of Holly Frindle Bungalow.

101. Ibid.

102. Ibid.

103. Avanti Architects, The Bungalow on the Beacon.

104. Avanti Architects, The Restoration of Holly Frindle Bungalow.

105. Stratton, Structure and Style.

106. Ibid.

107. Dawe, The Modern House.

108. Tobin, “The End of the Summer.”

109. Allan, Berthold Lubetkin.

110. Reading, Lubetkin & Tecton.

111. Healy, “Frank Yates, 1902–1994.”

References

- A Special Representative. 1931. “Amazing Traffic Chaos at New Zoo.” The Daily Telegraph, May 26.

- Allan, John. 1992. Berthold Lubetkin: Architecture and the Tradition of Progress. London: Artifice.

- Allan, John. 1994. “Berthold Lubetkin (1901–90).” Pidgeon Digital. https://www.pidgeondigital.com/talks/berthold-lubetkin-1901-90-/

- Allan, John. 2012. “House Style.” In Berthold Lubetkin: Architecture and the Tradition of Progress, 160–190. London: Artifice.

- Avanti Architects. 1988. The Bungalow on the Beacon: A Case for Restoration of Berthold Lubetkin’s House at Ivanhoe Beacon, Whipsnade. London: Avanti Architects.

- Avanti Architects. 1988. The Restoration of Holly Frindle Bungalow at Whipsnade Park, Bedfordshire: Report to the Zoological Society of London. London: Avanti Architects.

- Bateson, Gregory. 2000. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- “Bungalows at Whipsnade.” 1937. Architectural Review 81: 60–4.

- Chalmers Mitchell, Peter. 1937. My Fill of Days, by Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell. London: Faber & Faber.

- Chalmers Mitchell, Peter. 1945. Codicil to the Will Dated 16th Day of May 1945 of Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchel, Knight, C.B.E, F.R.S., GB 0814 KBAA. London: Zoological Society of London Library.

- Cox, S. 1988. “Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest: Bungalow at Whipsnade.” RIBA Collections, September 21.

- Crinson, Mark. 2017. Rebuilding Babel: Modern Architecture and Internationalism. London; New York, NY: IBTauris & Co. Ltd.

- “Crowds Besiege Omnibuses.” 1931. Daily Mail, May 26.

- Dawe, Nick. 2001. The Modern House Today. London: Black Dog.

- Dawes, Michael J., and Michael J. Ostwald. 2017. “Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language: Analysing, Mapping and Classifying the Critical Response.” City, Territory and Architecture 4: 17. doi:10.1186/s40410-017-0073-1

- Gold, John R. 1993. “‘Commoditie, Firmenes and Delight’: Modernism, the Mars Group’s ‘New Architecture’ Exhibition (1938) and Imagery of the Urban Future.” Planning Perspectives 8: 357–76. doi:10.1080/02665439308725780

- Goodbun, John. 2011. “The Architecture of the Extended Mind: Towards a Critical Urban Ecology.” Ph.D. thesis, University of Westminster.

- Gradidge, Roderick. 1992. “A Feeling for Restoration.” Country Life 186: 60.

- Healy, Michael J. R. 1995. “Frank Yates, 1902–1994: The Work of a Statistician.” International Statistical Review 63: 271–88.

- “Holly Frindle Bungalow, Whipsnade.” 2020. Historic England. https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1321291

- “House Adjacent to West Boundary of Whipsnade Zoo.” 2020. Historic England. https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1300803

- Lloyd Thomas, Katie. 2007. “Introduction: Architecture and Material Practice.” In Material Matters: Architecture and Material Practice, edited by Katie Lloyd Thomas, 1–12. London: Routledge.

- Lubetkin, Berthold. 1987. “Interview.” Architects Journal 16: 32.

- MacDonald, Susan. 1996. “Long Live Modern Architecture. A Technical Appraisal of Conservation Work to Three 1930s Houses.” Twentieth Century Architecture 2: 102–10.

- MARS group. 1938. New Architecture: An Exhibition of the Elements of Modern Architecture. London: New Burlington Galleries.

- Museum of Modern Art. 1937. Modern Architecture in England. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art.

- Pendar, Lucy. 1991. Whipsnade Wild Animal Park “My Africa”. Dunstable: The Book Castle.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus, Elizabeth Williamson, and Geoffrey K. Brandwood. 1994. Buckinghamshire. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Powell, Kenneth. 1997. “Beyond the Fringe.” In Structure and Style. London; New York: E&FN Spon.

- Rawes, Peg. 2013. Relational Architectural Ecologies: Architecture, Nature and Subjectivity. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Reading, Malcolm. 1992. Lubetkin & Tecton: An Architectural Study. London: Triangle Architectural.

- Riles, Annelise. 1998. “Infinity Within the Brackets.” American Ethnologist 25: 378–98. doi:10.1525/ae.1998.25.3.378

- Riles, Annelise. 2000. The Network Inside Out. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2009. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton, NJ; Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Stratton, Michael. 1997. Structure and Style: Conserving Twentieth Century Buildings. London; New York, NY: E & FN Spon.

- Tobin, Angela. 2012. “The End of the Summer.” This is Swiss. http://thisiswiss.blogspot.com/2012/09/the-end-of-summer.html

- “Two Bungalows at Whipsnade.” 1937. The Architects’ Journal 85: 299–303.

- Wilson, Robin. 2015. “‘Now, This Square Is Beautiful’: The Utopic Report of Lacaton & Vassal.” In Image, Text, Architecture: The Utopics of the Architectural Media, 101–126. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Archive Sources

- RIBA Collections, London, PA117/1, Survey drawing for the site of Hillfield, Whipsnade, Bedfordshire, by Tecton near 1931.

- RIBA Collections, London, LUB/11/7/7, letter by Geoffrey [Vevers], from Whipsnade, Beds, to Lubetkin; ms., signed on January 29, 1962.

- RIBA Collections, London, LUB/11/9/1-5, correspondence between Lubetkin, from Upper Kilcott Farm, David Verey, from Cirencester, and Nikolaus Pevsner, from Penguin Books, London; tss., February 19, 1965–January 12, 1967.

- RIBA Collections, London, LUB/4/5-7, correspondence and notes relating to the restoration of bungalows at Whipsnade, designed by Lubetkin and Tecton; tss. & mss., 1987–88.

- RIBA Collections, London, LUB/4/7/1-4, correspondence between Lubetkin, from Princess Victoria Street, Bristol, and Tess Vevers, from Holly Frindle bungalow, Whipsnade between May 1987–July 1988.

- RIBA library, London, LUB 4/5/16, John Allan et al., Notes of a Meeting at the Zoological Society of London held on July 15, 1988.

- The Ernő Goldfinger Papers at the RIBA Collections. GOLER\408-409.

- Zoological Society of London Library, London, GB 0814 WAA; WABJ, letter written by Chalmers Mitchell to Julian Huxley in 1937.

Appendix 1

Holly Frindle timeline; a for after, b for before, c for circa

Phase 1: construction and first inhabitants

1933 – Construction starts

1936 – Completion

1936–38 – Dame Dr Ida Caroline Mann

1938–45 – Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell

Phase 2: a house for well-being

1946c – Zoo researchers

1967c – Modifications and extensions: chimney and new kitchenFootnote100

1974 – Pictures in the report: “the house in its appropriate setting of well-trimmed lawns”Footnote101

1975c – Zoo vet living in Holly Frindle

1987c – Allan and others approach possible buyers such as Sir John Smith of the Landmark Trust

Phase 3: decay and refurbishment

1987–88 (winter) – House uninhabitableFootnote102

1988 (July–August) – Site visit by John Allan, Arup, Lubetkin and so onFootnote103

1988 (September 1) – Listed Grade II (meanwhile Elephant House and House A II*)

1988 (December) – Avanti Architects’ reportFootnote104

1996c–97b – RSH-P purchases the houseFootnote105

1997a – Grade II*Footnote106

2001b – RestorationFootnote107

2012b – Currently in use by RSH-P employeesFootnote108

Hillfield timeline

1935 – Completion (picture 5024/13 taken on February 18, 1935 showing structure almost finished)

1938 – Lubetkin gives the house to his friend Prascovia Schubersky, wife of Dr YatesFootnote109

1987a (May 26) – House is abandoned by Frank Yates (RIBA Collections, LUB/4/7/1)

1988b (July 3) – House in the Beacon report to convince the English Heritage Committee (RIBA Collections, LUB/4/5-7)

1988 (September 1) – Listed Grade II* (RIBA Collections, LUB/4/5/21)

1991 – Restoration appeal launchedFootnote110

1994 – Dr Yates diesFootnote111

1996b – Purchased by Mike Davies and maintenance works started (McDonald 1996)

Appendix 2

Personalities involved in Holly Frindle

Berthold Lubetkin “Tolek” – architect

Ida Mann – client, eye specialist

Zoo researchers – users

Geoffrey Vevers – Superintendent at London Zoo, occupies Springfield house

Tess Vevers – relative of Geoffrey Vevers. Sends letters to Tolek and Sasha

Sasha Lubetkin – Lubetkin’s daughter

Prascovia Schubersky – friend of Lubetkin and owner of House A. Communist activist (Alias Prascovia Yates, Mary Yates, Pauline Gray, Lubetkin)

Dr Yates – Schubersky’s husband and famous doctor. Communist activist (alias Francis Gray)

Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell – Secretary of the ZSL

Ernő Goldfinger – finds refuge in Hillfield in 1939