This special issue of Architecture and Culture on the ethics, power and politics in the stories of collecting, archiving and displaying architecture media draws attention to curatorial responsibilities in finding the proper placement for architecture collections, and how accessibility, reproducibility and promotion impact the cultural, economic and socio-political role of architecture media. And Yet It Moves questions the relevance of translations from place to place when mobile architecture media moves between offices, buildings, archives, exhibition spaces and websites. How does mobile media generate a dynamic trans-mediated construction and construing, finding renewed significance over time?Footnote1 This is also the subject of the parallel publication to this journal, The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models: From Translating to Archiving, Collecting and Displaying by the same editor (forthcoming).Footnote2

Architect and historian Robin Evans (1944–1993) outlined the imaginative role of the translational gap between drawings and buildings.Footnote3 Yet, translation does not end when buildings are built, and drawings and models are transferred to the places where their afterlives unfold. Considering that the Latin word translationem indicated a physical transporting from place to place, it is useful to reflect on the role, practices, power relations, political negotiations and agency of archival locations as sites-of-knowledge-construction and cultural production, questioning the lives of drawings and models after construction – when mobile architecture media are transferred to designated archival locations.Footnote4 These planned translatory acts result from decisions leading to changes in meaning. Importantly, what then emerges is that the epistemic relations in the thereafter of construction are context-dependent.

Every newfound location has the potential to generate, alter and affect sited-interpretations of architecture media. The siting of representational media (whether ubiquitous or not) has an impact on the construing of culture, the curatorial choices of inclusion/exclusion, omission/promotion,Footnote5 or the lost and found materials in archival collections and what remains obscured or hidden in dark archives (the hardly accessible or restricted parts of repositories).Footnote6 Diverse and inclusive knowledge construction is context-dependent. Thus, archival locations, ownership and accessibility, copyrights and rights-to-copy impact the ethical framework,Footnote7 the power and politics enacted in the readings and uses of architectural media and what they yield in terms of cultural imagination, memory, and differentials.

After the changes brought about by the so-called “archival turn,” described by anthropologist Ann Laura Stoler as a change from archive-as-source to archive-as-subject,Footnote8 this special issue draws attention to the archive-as-place. Archival drawings and models are sited epistemic objects, and it is this situatedness that determines their ethical and political agency. Derrida affirmed that:

They [archival documents] inhabit this uncommon place, this place of election where law and singularity intersect in privilege. At the intersection of the topological and the nomological, of the place and the law, of the substrate and the authority, a scene of domiciliation becomes at once visible and invisible.Footnote9

Under this premise, such topology, or the study of the locations where drawings, models and other materials are domiciled in designated archival places, should be understood as a formation process, that is to say that epistemic objects are an integral part of the meaning and construction of places, and vice versa, the places where documents, drawings and models are kept impact their reading and interpretation.Footnote10 Changes in archival locations have implications on our ability to access, analyze, and interpret such artifacts, directly impacting the ongoing rewriting of the histories and theories of architecture and their influence on broader cultural and political issues.

The dual significance of the translation of media – both as mobile and epistemic artifacts – has a bearing on the changes of meaning that occur when interpreting media. Archivist and author Verne Harris, Head of Leadership and Knowledge Development at the Nelson Mandela Foundation, affirmed that “the archive is politics.”Footnote11 More so, the political dimension of architecture media emerges clearly out of this very condition of being sited, enacting unique power dynamics in terms of research access, curatorial choices and emerging meanings.

The urgency of the questions related to archival choices becomes apparent when considering that the age of digital production, overproduction and reproduction is reconceiving not just architecture media but also the modes of archival access on a local and global scale.Footnote12 The digital age is characterized by ubiquitous sites of drawing production and archival. Even though it is now possible to reproduce digitally analog drawings and models in multiple copies or born-digital media in multiple originals, facilitating the construction of architecture theory and pondering its significance,Footnote13 born-digital media might not remain fully accessible long into the future due to the rapid obsolescence implied by software development. Nowadays, private and public architecture archives are hybrid digital/physical constructs faced with the challenge of what and how much to preserve and how to regulate privilege and access.Footnote14

The significance of the history of continuity and contiguity of drawings, models, and buildings establishing meaningful on-site relations (in situ) versus off-site archival (ex-situ), has yet to be fully acknowledged. The architects, scholars, design practitioners, architect-archivists and curators contributing to And Yet It Moves and the Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models tackle questions informing the future planning of archival sites-in-becoming – considering how past and future are to engage in meaningful, inclusive and multicultural relations.Footnote15

The nine contributions to this special issue invite reflection on the role, practices, power relations, political negotiations and agency of archival locations as sites-of-knowledge-construction and cultural production. They question the lives of architecture media in the afterlife of construction, providing insight into how such locations and modalities of access to materials contribute to the construction of culture in relations to given sites of origin – where the drawings were made, where the buildings were built, and where stories-took-place.Footnote16

When kept in-situ, the spatial contiguity and temporal continuity of drawings-models-and-building may define an extended site of knowledge construction – an archive with a dual nature of cultural recollection and fostering of future imaginings. This is the case of the Instituto Bardi housed at Casa De Vidro in Morumbi, São Paulo, Brazil since 1990, which transformed from the private dwelling of Lina Bo (1914–1992) and Pietro Maria Bardi (1900–1999) into an international cultural institution and archive including a collection ranging from professional to personal items. The archive holds not only architectural, design and illustration drawings but also letters, a library, furniture and artwork, forming a sited-collection of over 40,000 items kept in the house designed by Lina Bo Bardi (). Sol Camacho discusses questions of archival systematization addressing their specific location in relation to accessibility of the contents, loan policies and financial stability.

Figure 1 Lina Bo Bardi at Casa De Vidro in Morumbi, São Paulo, Brazil, 1952. Photo by Francisco Albuquerque. © Instituto Bardi/Casa de Vidro and Instituto Moreira Salles.

In A Lifetime of Collecting: Pietro M. Bardi and Lina Bo Bardi’s Archive, Camacho, the Cultural Director of the Istituto Bardi, narrates the transformation and the challenges faced by the private nonprofit institution, examining its role and relevance in the national, Latin American and broader international context over four decades.

Archival legacy agency is challenged by the Brazilian national context where architecture archives often were and still are private endeavors, except for repositories within academic institutions and architecture schools such as the Faculty of Architecture of the University of São Paulo (FAU USP), actively archiving architecture collections since the 1970s. While, as Camacho writes, Brazil lacks a national public institution valorizing the work of architecture media and the profession, the presence of architectural archives held within architecture schools shows the fostering of the educational value of architecture media in the academic context.

Camacho also addresses the recent acquisition of the archive of 2006 Pritzker prize laureate Paulo Mendes da Rocha (1928–2021) by the private nonprofit Casa da Arquitetura in Matosinhos, Porto, and the attention that this donation and transfer of materials to Portugal (September 10, 2020) has drawn not just to the context of the current situation in Brazil, but also to the question of finding the proper location of archival holdings in relation to the places of origin of the works.Footnote17

Mendez Da Rocha’s decision to donate his collection of architecture media to the Portuguese archive has been criticized by those who have seen this archival dis-location out of the Brazilian context to have a colonial undertone.Footnote18 However, the motivation may be partly due to the new governmental policies and the radical changes recently introduced in Brazil, with the incorporation of the Ministry of Culture into the Ministry of Citizenship and the implied potential reduction of public and private funding.Footnote19 Over the last few years, in fact, a number of museums have been affected by devastating fires with irreparable cultural losses that could have been prevented with adequate financial support for fire prevention and the upkeep of the buildings housing such institutions.Footnote20 However, the question of the appropriateness of the archival location came to the fore in consideration of the interposed physical distance between the building sites and the archival sites where architecture media are stored. In response to this challenge, Nuno Sampaio, the director of the Portuguese archive, committed to the complete digitization of the collection, which would offer, once accomplished, remote access to materials aiding their global reach.

Camacho, one of the participants in the Brazilian architectural archival network launched in 2018 by the Instituto de Arquitetos do Brasil, São Paulo (IAB SP) to promote the creation and agency of public and private architectural archives, stresses the overlooked questions of the valorization of architectural collections. The 2021 Special Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement in memoriam awarded to Lina Bo Bardi by La Biennale di Venezia draws attention to her legacy safeguarded at Casa De Vidro and the lifelong efforts of the Bardi couple in raising awareness of art and architecture in the Brazilian context. Lina Bo Bardi’s notion of a “historical present” – discussed by Camacho in her essay – finds renewed significance in relation to the current politics, power and culture of the siting of architecture media in Brazil, raising questions of research and broader cultural value and agency in a digital, transnational condition.

Drawing in a Memory Theater: Revisiting Marco Frascari on Carlo Scarpa’s Reggia – Mastio Bridge Drawings at the Castelvecchio, by architect and scholar Sam Ridgeway, explores the construing and constructing of memory in places over time, from the city to the building, from the construction site to the archive as a memory theater. As he explains, the “memory theater” is enacted in drawings that are witnesses to buildings and sites under transformation where cultural and historical events are grounded. A whole city, in this reading, can become the witness of a sited-history where built artifacts of architecture become memory theaters embodying and displaying the facticity of history.Footnote21

The in-situ Carlo Scarpa Archive (Archivio Carlo Scarpa) at the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona () was born from the decision to maintain the original drawings on site. This story is narrated by the archive curator, Alba di Lieto in The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models.Footnote22 The seed of this collection developed in recognition of the site as a possible archive of architecture media. The Carlo Scarpa Archive began with the purchase in 1973 of Scarpa’s drawings by Licisco Magagnato (1921–1987), the director of the museum during Scarpa’s renovation periods (1957–1964, 1965–1975). In 2002 the valorization of the drawings, which had been catalogued and preserved in situ, began. The archive was systematized, thus becoming available to researchers and architects during building maintenance, renewal, and new design interventions on the same site.Footnote23 A digital archive was also created to facilitate off-site research.

Figure 2 Carlo Scarpa Archive, 2013. Visit of the Amici dei Musei after the inauguration of the Tower with the Curator of the Carlo Scarpa Archive, Alba Di Lieto. © Photograph by Federico Puggioni. Courtesy of Castelvecchio Museum, Verona, Italy.

Considering Ridgeway’s essay, it is possible to think of the archive itself as a “memory theater” born from and within the building, which brings into focus historical artifacts interpreted anew in the readings of architecture media by archivists, scholars, architects and historians over time. Indeed, as the author reminds us, the words theater and theory share the same etymological root, enabling a sited “relationship between the human body and the theater, and the theater of memory.” Ridgeway explains that in Giulio Camillo’s memory theater (ca. 1480–1544), “the person exploring its encyclopedic collection physically moves between images, texts, and objects to gain comprehension.”

The archive thus performs and reenacts memories when documents are interpreted and engaged in situ – in the very places where they first witnessed history, where they were conceived and kept (). Every new act of engagement with archival artifacts extends an original dialogue with the monument and the storytellers, who participate in the continuous reinterpretation of a site that is always in-the-making.Footnote24 One could say that the relationship between the archivist and the archive shapes and is shaped by memories revealed and concealed in-situ, witnessing a cosmic order and establishing the order of the archive.

Figure 3 Museum of Castelvecchio’s courtyard seen from a window of the Carlo Scarpa Archive, Verona, Italy. © Photograph courtesy of Prakash Patel.

In – Filarete’s Libro and Memoria: The Archive within a Book – Berrin Terim narrates the story of a Renaissance manuscript – Filarete’s Libro architettonico Codex Magliabechianus (1460–1466 ca.) – as a traveling archive that moves beyond the bounds of a physical place where history is often believed to be preserved as stable and neutral content, an idea challenged by post-modern studies.Footnote25 Terim elucidates the possibility that Filarete conceived the book as his “main edifice,” erected to transport his ideas not just from place to place but also through time.

Terim unveils how the tactic of inserting within the manuscript the fictional story of a rediscovered Golden Book from a distant age reveals Filarete’s hope that his work could be rediscovered at a future time and place. This traveling Renaissance archive, in the form of a book collecting stories and drawings of real and imagined places designed by its author, may have been related to his ambition to be recognized as an architect in posterity,Footnote26 considering the limited acknowledgement that was custom for the creators of design and built work during that period.

In – Designing in Real Scale: The Practice and Afterlife of Full-Size Architectural Models from Renaissance to Fascist Italy – Claudia Conforti, Fabio Colonnese, Maria Grazia D’Amelio, and Lorenzo Grieco discuss the unlikely afterlives of full-size architecture models, focusing on their use as political props during the Fascist period in Italy. Architecture media is demonstrated to be de facto a medium of communication – transforming itself into the message – an outright propagandistic political tool projecting an image of power.

Through a careful analysis of life-size models, their materiality and assembly, like that of the three-story statue described as a “fragile colossus of gypsum blocks, stacked like a cyclopean wall,” personifying Fascist Italy, the authors unravel an interpretation of the facticity of this model as a telling sign of both the political agenda of the fascist regime in Italy in the 1940s and its fate of dissolution hinted by the temporary nature of the chosen material and its expedient and economical construction. Such full scale models – instruments of political power – survive today mainly through archival photographs and as re-sited elements. Such photographic trans-mediations and spoils gain new meanings in their afterlife as evidentiary witnesses of the bygone time of the Fascist regime.

In the essay – ‘Ugly’ Architectural Drawings of William Hardy Wilson: (Re)Viewing Architectural Drawings with Difficult Origins or Content for Curation and Display – Yvette Putra introduces the need for critical methodologies for the display and curation of objectionable works concealing a problematic history of discrimination, colonialism, sexism and racism. Putra reveals how the awareness of such histories transforms the sites and sight of the celebrated drawings of Australian architect William Hardy Wilson (1881–1955) from mystifying drawings exhibiting technical mastery to unsightly architecture media evidencing a history of discrimination.

Putra introduces the concept of “ugly” architecture drawings not to refer to an esthetic judgment but to a radically transformed reading of them, which is influenced by a deeper understanding of Hardy Wilson’s background. The specific cultural and political context in which the works were produced and the not-so-hidden political intent behind them become central to their interpretation and experience. Putra makes recommendations for a methodology of displaying and curating problematic pieces that partake in a dark history of racism, suggesting that contextualization and acknowledgement are necessary to open the door to a critical analysis that reaches into the significance and latent meanings beyond merely esthetic value.

Rather than avoiding such controversial history – leaving materials in the dark corners of archival repositories – the author suggests the importance of bringing artifacts and controversial materials out from their archival places to create an opportunity for their translation and re-contextualization in the present time. This exhibit and exposure of controversial past histories determines a critical evaluation of the work of Hardy Wilson in the context of the history of Australian architecture during the first half of the twentieth century.

In Collecting State Contents, Territory and Value in France, c. 1700–1850 Jonah Rowen introduces the dual use of the mobile plan-relief models used to collect and display the state’s contents in eighteenth and early nineteenth century France. Architecture media was deployed as an instrument of power and control, contributing to the construction of the image of the nation-state and its territorial extension through the developing science of cartography while also creating a taxation instrument of political economy by surveying the land and its contents. The plan-relief models made possible a physical manifestation of the territorial domain of a nascent state and its land use while also accounting for “political subjects” residing in distant places.

The author discusses the changing understanding and perception of the traveling models as siteless-objects indexing sited territories observed from a centralized location where they were displayed. The models, objectifying the state’s contents, were esthetic and military instruments of accounting and taxation. The historical shift from display to archival signifies a change in the significance of the plan-relief models. While they were initially displayed as “artifacts of covert military intelligence” at the Tuileries Palace since 1697, manifesting embodied demonstrations of the centralization of power and control over a vast territory, nowadays, the “un-situated models” belong to the Ministry of Cultural heritage and are archived at the Musée des Plans-Reliefs in the Hôtel des Invalides in Paris as cultural artifacts indexing a history of the political economy of the emergent mercantile-colonial eighteenth century French state.

Such plan-relief models are not unlike what Bruno Latour defines as “immutable mobiles,” intended to carry stable knowledge from place-to-place, translating real immovable places from their original context to new centralized sites of power.Footnote27 However, it could be argued that when epistemic objects are recontextualized in a new archive or exhibition site, a cultural and political shift happens. From this premise, “immutable mobiles” transform into what I would call ‘mutable mobiles.’ The translations to newfound archival locations correspond directly to moments of critical re-interpretation where architecture media are re-negotiated in place through time, re-defining their significance.

Julien Lafontaine Carboni discusses in Undrawn Spatialities. The Architectural Archives in the Light of the History of the Sahrawi Refugee Camps the potential of architectural knowledge that does not rely on traditional architecture media translating to and from built realities. He questions the archival challenges posed by “undrawn spatialities” in the context of some of the oldest refugee camps in the world – the Sahrawi refugee camps (1975–1991). The author provides his first-hand account of visiting the archives of the Ministry of Information of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in Rabuni, where he gained access to materials collected under the Oral Culture project launched in 2010 by the Sahrawi Ministry of Culture.

Lafontaine Carboni unravels the role of women and their organizational systems in establishing the refugee camps. Women developed a unique craftwomanship by molding bricks and setting up essential structures like tents and a hospital, negotiating their refugee site with their memories of traditional forms of inhabitation. They made appropriate changes to adapt to harsh conditions partly determined by the limited availability of resources and support in the absence of men in the camps, thus emphasizing the role of women’s collective imagination developed through oral culture. Aguaila, a public figure and traditional medicine specialist, shared with Lafontaine Carboni the story of her exodus from the Sahrawi territories in Western Sahara to the refugee camp in Smara at the Algerian border in 1975. During their encounter, Aguaila manifested gestures reenacting what Lafontaine Carboni defines as “undrawn spatialities,” or “figurations anchored in her body, carrying with her a timeless co-shaping of desert spatialities and the Sahrawis’ gestures.”

Lafontaine Carboni unravels the archival significance of oral culture unmediated by architectural representation, unpacking the necessity to hold on to nomadic knowledge during a protracted period of immobilization in the camps. The archival knowledge construction is essential to the survival of intangible histories, holding on to a nomadic culture developed over centuries. As the author states, the archival process is projected toward a future of Sahrawi knowledge re-construction. Such process is arguably not unlike the construction of what Derrida described as “transgenerational memory,” uniting the archival project with “ancestral experience.”Footnote28

Lisa Landrum’s essay, Tableaux Vivants: Tables and Stages of Architectural Striving, focuses on the worktables of architects as “miniature theaters” – the sites of “dramatic knowledge construction,” enacting in these miniaturized worlds the presence of the actual sites of building construction. She provides a historical account relying on both drawings and writings by Soul Steinberg (1914–1999) and Marco Frascari (1945–2013), the ideas of philosophers Georges Perec (1936–1982) and Michel Foucault (1926–1984), as well as art historians Georges Didi-Huberman and James Elkins. She narrates their transformation from portable desktops to sited mechanical tables with adjustable tops where “personal and shared cosmologies convene.” The author describes the drafting tables in the drawings of Frascari as places where ideas are gathered, confronted and enacted with an open mind. Indeed, Frascari’s idea of the vertical drafting table was that of a window onto the mundus imaginalis.Footnote29

Landrum argues that students’ worktables at the architecture program, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada, where she teaches, can be deemed in situ archives destined for oblivion. Such drafting tables collect in and over their bare surfaces the accumulated marks of “infra-ordinary traces of ordinary design processes” by architecture students since 1959. The studio space itself developed from understanding the design practices at the worktable, indexing architectural design as a social rather than a solo practice. The author’s essay takes the form of an archive in which images trans-mediate the disused tabletops into a possible afterlife.

In the concluding interview enclosed in this special issue, Archival Futures. Born Digital Architecture Media, curator Annet Dekker is invited to comment on the archival of architecture media, such as the transfer of the documents of MVRDV to Het Nieuwe Instituut (HNI) in Rotterdam – the first archival collection of almost entirely born digital architecture media. She is the author of Collecting and Conserving Net Art; Moving Beyond Conventional Methods,Footnote30 a book where she reveals how the unique nature of born digital art and media is changing what archiving and preserving means today, reflecting on concepts of democratization of digital archival access and the challenges posed by “dark archives.” She addresses numerous questions ranging from how the techniques and cultures of archival technologies are affecting or affected by changing modes of media production, the vital curatorial questions regarding inclusion/exclusion, omission/promotion of materials, and the potential for the creation of “living digital archives” of digital media.

Taking note of the situatedness of archives is essential, as this sets the unique conditions of access in relation to the geographic, cultural, economic and socio-political context of collections and their materials. The politics of archives are both internal and external to the institution. The ways in which an archive may regulate privilege and access is based on specific inward and outward-facing regulations particular to the private or public institutions, yet changing over time in any given socio-cultural and geo-political context. However, the agency of archives is also dependent on local archival cultures and their role in the constructions and interpretations of epistemic realities, which are also dependent on the broader political context of the nation states in which they operate. Situatedness is set out to determine all of these factors directly or indirectly.

In her essay, Camacho argues that Lina Bo Bardi’s projects travel when archival media is loaned for exhibition purposes, when it is published or displayed. She poignantly states that “the residence itself is part of the archive,” which arguably underscores the importance of the direct experience of archival materials in their unique and situated condition. In this light, the ambiguous conversions of the house into an archive, which is also a home exhibiting itself – or a museum – which is also an institute, reveals a series of ambiguous conversions dependent on the cultural approach adopted in the interpretation of the site. The Bardi house-archive-museum-institute is part of the Brazilian cultural and political context. The experience of the archival materials within the house is not replaceable by the remote access to low-resolution images of the drawings in a ubiquitous digital archive.

Marco Frascari noted that “Architecture cannot be shown in museums.[…] In museums drawings, models or photos of architecture can be shown and appreciated for their own intrinsic qualities as agents and vehicles for architecture […] these visual means connote architecture, but the architectural qualities and properties cannot be directly denoted.”Footnote31

Drawing on Frascari’s distinction between connoting and denoting architecture, the on-site presence of elected representations becomes emblematic of the process of on-site inventory in its dual nature of cultural recollection and fostering of future imaginings. The stories-telling of the site, the site of building construction and the edifice exist in various relations to each other, extending the lives of drawings in meaningful ways beyond a time of construction, which is often understood as the end of the translational relations.

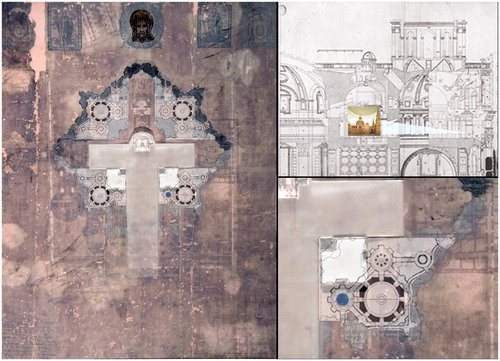

In the context of in situ archives, like the Bardi Institute or the Carlo Scarpa Archive,Footnote32 the container/contained relations can be inverted in a co-sited condition, where both media and architecture conspire and act together in the construction of memory and projective design over time. There are numerous examples of in situ archives, both historically and in recent times. A historical example of in situ archives is the Archivio Storico della Fabbrica di San Pietro (Historical Archive of the Fabric of St. Peter’s). The archive founded in 1579 is still housed within the basilica. The relationship between Renaissance drawings, models and basilica is more than what exists between a container and its contents, typical of contemporary archival and museum practices, revealing something different from the mere desire for archiving or displaying. The translations from one drawing to another, from a drawing to a model or a full-scale prototype, manifest the role of drawings and models that have never left the site, defining an active dialogue between the building and its twin representations, creating the possibility for sited-reinterpretations. The position of the octagonal rooms of the archive above the barrel vaults converging into the central area of St. Peter’s suggests the idea of the archive itself as a compass of time, providing orientation toward the past and the future (). The presence of the archive inside the building means that the future of the religious edifice and its epistemic representations kept within it have a shared destiny. In this place, an ambiguity is revealed: the archive is more than a storage place and architectural drawings and models are more than instruments of building construction.

Figure 4 Hybrid collage showing the location of the Historical Archives of the Fabric of St. Peter’s in the Vatican. Left: Plan of the archives located in octagonal rooms above the level of the barrel vaults. Right: Drawing plan and section of the octagon of St. Jerome where the model (1539–1546) of Antonio da Sangallo the Younger (1484–1546) for St. Peter’s is kept. © Federica Goffi.

It is often assumed that the mobility of drawings during the Renaissance period freed the architect from the building site and that the medieval practices of tracing drawings and profiles of full-scale architectural elements on site document the immobility of drawings, which were an integral part of the construction site and the building. But it could also be hypothesized that it was precisely the presence of mobile drawings and models that were housed near or within a construction site, where in some cases they can still be found today, that originated the practice of in situ archives, sustaining an active epistemic dialogue with the edifice even after the death of an architect, something that was not an uncommon circumstance in relation to long construction campaigns.

Several archives were created in the proximity of St. Peter’s – the main church of Christendom – a center of religious spirituality but also political power, or in other words, the designated axis mundi of Christianity itself, an essential locus in the process of construction of Catholic identity. The location of the Fabric’s Archive in this centralized place shows how the archive itself was construed and constructed in the collective imaginary as a key immobile locus from where history originated.

And yet they moved- numerous drawings from the Renaissance renewal period of St. Peter’s Basilica are now kept in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi in Florence. Despite their mobile nature, it is more likely that they can be exhibited in various museums worldwide as works of art, connoting architecture, rather than becoming part of the denoting functions of the twinned building, even if only for research purposes.

Contemporary architecture archives most often house collections of architectural drawings (ex-situ) by storing the drawings in places that are distinct from where the drawings were made and the places where the buildings were built, drawing attention to the architect as an individual creator by listing collections under their name and keeping all projects drawings by one architect in one or few archival locations. Conversely, the keeping of drawings in the buildings that they represent reveals that the purpose of in situ conservation is related to the idea that drawings are design instruments with the potential to offer meaningful insight into future building renovations and construction programs.

The saying attributed to Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), “And Yet It Moves,” even though not authored by him, is exemplary of a story,Footnote33 as well as a cultural and revolutionary cosmological mindset. Translated in the context of this special issue, it hints at the idea that archival materials are both sited and mobile.Footnote34 This dynamic condition is amplified in a global digital age, and yet archives remain impacted by their local cultural, political, and geographically sited conditions and their policies and politics of access, inclusion and promotion. The possibility to mobilize knowledge through digital archival methods, allowing researchers, architects, connoisseurs and the broader public to come into contact with these realities, has the potential to narrow the dark corners of archives, opening the doors to multi-culturally-sited and temporal interpretations.

It is worth noting that Galilei’s trial documents (1633) are still conserved at – and never left – the Vatican Secret Archives funded in 1612 by Pope Paul V and renamed in 2019 by Pope Francis, as the Vatican Apostolic Archive.Footnote35 The naming of the archive as “Secret” – from the Latin secretus, set apart – refers to the fact that such archive was (and still is) private and thus subject to unique regulations of privilege and access.Footnote36 And yet some of the materials of Galilei’s trial moved from the location where they have been kept for centuries, coming out of the dark recesses of archival shelves to be displayed for the first and only time in history in the context of the exhibition, Lux in Arcana - The Vatican Secret Archive Reveals Itself, which was held at the Capitoline Museum in Rome in 2012.Footnote37

Nowadays, secrecy and privacy have overlapping and obfuscating meanings. Who chooses how, what and when materials can be accessed? Preclusion from the study of materials may depend on an author’s wishes,Footnote38 the decisions of the heirs of a collection,Footnote39 or the policies of private or public institutions in relation to the imposed temporal distance from a historical record or its political content.

And yet they move – drawings and models as ‘mutable mobiles’ move between places and are moved by changing ideas and questions. Each archival location holds significance in place.Footnote40 An archive is a place where the traces of history accumulate, and sited-interpretations take hold, but can also be hidden or lost over time. The archive-as-place holds the potential to affect meaning through its socio-cultural and geo-political situatedness. While translations of materials from one place to another are motivated by reasons that cannot be overlooked and should be questioned, archives are the cause and sites originating the movement of ideas even in the absence of physical movement.

Acknowledgement

With thanks to Prof. Suzanne Ewing, Editor of Architecture and Culture for her insightful advice and support throughout the production of this special issue.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Federica Goffi

Federica Goffi is Professor of Architecture, Interim Director and Co-Chair of the PhD and MAS Program at the Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism at Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada (2007-present). She was an Assistant Professor at INTAR, RISD, US (2005–2007). She holds a PhD from Virginia Tech in Architecture and Design Research. She has published book chapters and journal articles on the threefold nature of time-weather-tempo. Her book, Time Matter[s]: Invention and Re-imagination in Built Conservation: The Unfinished Drawing and Building of St. Peter’s in the Vatican, was published by Ashgate in 2013. Her recent edited volumes include Marco Frascari’s Dream House: A Theory of Imagination (Routledge 2017), InterVIEWS: Insights and Introspection in Doctoral Research in Architecture (Routledge 2019), and the co-edited Ceilings and Dreams: The Architecture of Levity (Routledge 2019). Her edited book The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models: From Translating to Archiving, Collecting and Displaying is forthcoming. She holds a Dottore in Architettura from the University of Genoa, Italy. She is a licensed architect in her native country, Italy.

Notes

1. Regarding the concepts of construction and construing in architecture theory see Marco Frascari, “The Tell-the-Tale Detail,” VIA no. 7 (1981): 23–37.

2. Federica Goffi, ed., The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models: From Translating to Archiving, Collecting and Displaying (London: Routledge, 2022).

3. Robin Evans, Translations from Drawing to Building (Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1997), 154–163.

4. Marco Frascari, Monsters of Architecture: Anthropomorphism in Architectural Theory (Savage, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1991), 77; Thordis Arrhenius, Mari Lending, et al., Place and Displacement. Exhibiting Architecture (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2014); Eeva Liisa Pekonen, Carson Chand and David Andrew Tasman, eds., Exhibiting Architecture: A Paradox? (New Haven and Barcelona: Actar, Yale School of Architecture, 2015); Jordan Kauffman, Drawing on Architecture: The Object of Lines, 1970–1990 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018); Eeva Liisa Pekonen, Exhibit A: Exhibitions That Transformed Architecture, 1948-2000 (London: Phaidon Press, 2018).

5. See, for example, “The Critical Visitor,” a research project into heritage institutions with attention to questions of inclusivity and accessibility in which Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam participates as a partner. https://hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en/critical-visitor-important-subsidy-allocation-nwo-smart-culture (accessed May 11, 2021).

6. See the interview “Archival Futures. Born Digital Architecture Media,” with Annet Dekker in this special issue.

7. See the Code of Ethics adopted by the International Council on Archives on September 6, 1996 at the XIII general assembly in Beijing, China, https://www.ica.org/sites/default/files/ICA_1996-09-06_code%20of%20ethics_EN.pdf (accessed May 16, 2021).

8. Stoler defines archives as “something in between a set of documents, their institutions, and a repository of memory-both a place and a cultural space that encompasses official documents but are not confined to them.” Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 44, 49.

9. Jacques Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” Diacritics 25, no. 2 (1995): 3.

10. See, for example, as a study of domiciliation, the analysis of the sited immobile drawings of Michelangelo: “The ‘house arrest’ of Michelangelo’s mural drawings,” by Jonathan Foote, in Goffi, The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models.

11. Verne Harris, “Archives, Politics and Justice,” in Political Pressure and the Archival Record, ed. Margaret Procter, Michael Cook, and Caroline Williams (Chicago: Society of Architectural Archivists, 2005), 173.

12. Frans Neggers, “Setting up Het Nieuwe Instituut’s Digital Archive,” February 17, 2020, https://collectie.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en/preservation/setting-het-nieuwe-instituuts-digital-archive (accessed May 11, 2021).

13. Federica Goffi, “Translations and Dislocations of Architectural Media at the Fabric of St. Peter’s in the Vatican,” arq: Architectural Research Quarterly 22, no. 4 (2018): 325–338.

14. See the chapters: “The Move of the Frank Lloyd Wright Drawings and Models. From Private Archive to Public Collection and Its Promotion of Use and Deterrence of Abuse,” by Neil Levine; “I will Begin with the Jar of Empty Pen Caps. The Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania,” by William Whitaker; “The Living Archive. The Renzo Piano Building Workshop and the Renzo Piano Foundation,” by Renzo Piano, Chiara Bennati, Nicoletta Durante and Giovanna Langasco in Goffi, The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models. For a short review of the history of architectural museums and their archives see John Harris, “Storehouses of Knowledge: The origins of the Contemporary Architectural Museum,” in Canadian Center for Architecture, Building and Gardens, edited by Larry Richards (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1989), 15–32. Regarding digital collections see the essay by the Manager of the Heritage Department of Het Nieuwe Instituut, Behrang Mousavi, “The future of Digital sustainability,” https://collectie.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en/collection-news/future-digital-sustainability (accessed March 7, 2021).

15. See the essay, “‘Ugly’ Architectural Drawings of William Hardy Wilson: (Re)Viewing Architectural Drawings with Difficult Origins or Content for Curation and Display,” by Yvette Putra and the essay, “Collecting State Contents, Territory and Value in France, c. 1700–1850,” by Jonah Rowen in this special issue.

16. Karl Schlögel, In Space We Read Time: On the History of Civilization and Geopolitics, tran. Gerrit Jackson (New York: Bard Graduate Center, 2016).

17. Giulia Ricci, “Paulo Mendes da Rocha’s Archive is now in Portugal (and Not Without Criticism),” Domus, September 11, 2020, https://www.domusweb.it/en/architecture/2020/09/11/paulo-mendes-da-rochas-archive-is-flying-to-casa-da-arquitectura-portugal-and-not-without-criticism.html (accessed February 7, 2021). See also the chapter: “The Archives of Luis Barragán. A Complicated and Controversial Story” by Louise Noelle Gras, in Goffi, The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models.

18. For a recent study of the phenomenon of archival displacement denoting a questionable even if legal removal of archives from an original place, see James Lowry, Displaced Archives (London and New York: Routldge, 2017), 1–22. Such archives are referred to as “migrated archives” or “expatriate archives.” Lowry, Displaced Archives, 4.

19. Giacomo Pirazzoli, “Mendes da Rocha, gli archivi e le ferite coloniali del Brasile, Il Giornale dell’Architettura,” September 23, 2020, https://ilgiornaledellarchitettura.com/2020/09/23/mendes-da-rocha-gli-archivi-e-le-ferite-coloniali-del-brasile/ (accessed March 7, 2021); Brigit Katz, “Brazil Dissolves Its Ministry of Culture,” Smithsonian Magazine, January 10, 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/brazils-new-government-has-dissolved-countrys-culture-ministry-180971236/ (accessed April 18, 2021); Gabriela Angeleti, “Jair Bolsonaro’s Government Extinguishes Brazilian Ministry of Culture,” The Art Newspaper, January 9, 2019, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/brazilian-culture-ministry-bolsonaro-osmar-terra (accessed April 18, 2021).

20. See Ela Biettencourt, “As Fires Consume Brazilian Cultural Heritage, Could Cinemateca Brasileira Be Next?” Frieze, May 10, 2021, https://www.frieze.com/article/fires-consume-brazilian-cultural-heritage-could-cinemateca-brasileira-be-next (accessed June 1, 2021). In 2018 a large fire devastated the National Museum of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/03/world/americas/brazil-museum-fire.html (accessed June 1, 2021).

21. Regarding the concept of facticity see François Raffoul and Eric Nelson, eds., Rethinking Facticity (Albany: State University of New York, 2009).

22. See the chapter by Alba Di Lieto, “A Well Sited Archive. The Carlo Scarpa Archive at the Castelvecchio Museum,” in Goffi, The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models.

23. Alba Di Lieto, I Disegni di Carlo Scarpa per Castelvecchio (Venezia: Marsilio, 2006). See also the online digital archive of the Carlo Scarpa Archive at the Museum of Castelvecchio, http://www.archiviocarloscarpa.it/web/progetto.php?lingua=e (accessed April 18, 2021).

24. Federica Goffi, Time Matter(s): Invention and Re-Imagination in Built Conservation. The Unfinished Drawing and Building of St. Peter’s, the Vatican (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2013), 8–9, 61–63.

25. Terry Cook, “Archival Science and Postmodernism: New Formulations for Old Concepts,” Archival Science 1, no. 1, 2000: 3–24; Randall C. Jimerson, “Archives for All: Professional Responsibilities and Social Justice,” The American Archivist no. 70, Fall/Winter 2007: 252–281. See also Ann Laura Stoler about the critique of the concept of archives as “stable ‘things’ with ready-made and neatly drawn boundaries.” Stoler, Along the Archival Grain, 51.

26. Marco Frascari, “Horizons at the Drafting Table: Filarete and Steinberg,” in Chora 5: Intervals in the Philosophy of Architecture, ed. Alberto Pérez-Gómez and Stephen Parcell (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007), 179–200.

27. Bruno Latour, “Visualization and Cognition. Drawing Things Together,” in Knowledge and Society Studies in the Sociology of Culture Past and Present, ed. Henrika Kuklick and Elizabeth Long (Greenwich, CT: Jay Press, 1986), IV: 1–40.

28. Derrida, “Archive Fever,” 27.

29. Marco Frascari, Marco Frascari’s Dreamhouse: A Theory of Imagination, ed. Federica Goffi (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 6–8.

30. Annet Dekker, Collecting and Conserving Net Art: Moving Beyond Conventional methods (London: Routledge, 2018); See also Annet Dekker, ed., archive2020. Sustainable Archiving of Born-Digital Cultural Content (Amsterdam: Virtueel Platform, 2010).

31. Frascari, Monsters of Architecture, 77.

32. Regarding the John Soane Museum, an architecture office turned into museum, see “The place of models and drawings in Sir John Soane’s House and Museum,” by Helen Dorey, in Goffi, The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models.

33. Giuseppe Marco Antonio Baretti, The Italian Library. Containing an Account of the Lives and Works of the Most Valuable Authors of Italy: With a Preface, Exhibiting the Changes of the Tuscan Language, from the Barbarous Ages to the Present Time (Londra: A. Millar in the Strand, 1757), 52.

34. Evans, Translations from Drawing to Building, 160. Mario Carpo, “Building with Geometry, Drawing with Numbers,” in When is the Digital in Architecture? ed. Andrew Goodhouse (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017), 43. The medieval practices of tracing drawings and profiles of full-scale architectural elements on the site document the immobility of the drawings, which were an integral part of the construction site and the building. Some of the well documented medieval examples include the “tracing houses” of Wells and York Minster Cathedral. Alexander Holton, “The Working Space of the Medieval Master Mason: The Tracing Houses of York Minster and Wells Cathedral,” in Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Construction History (Volume II, 2006): 1579–1597.

35. Archivio Segreto Vaticano [ASV], Misc., Arm. X 204. Sergio Pagano, I Documenti Vaticani del Processo di Galileo Galilei (1611–1741) (Vatican: Archivio Segreto Vaticano, 2009), 10. See also https://www.swissinfo.ch/ita/lux-in-arcana_l-archivio-segreto-vaticano-si-svela-al-pubblico/32254578 (accessed May 9, 2021).

36. The extensive Vatican Apostolic Archive is the personal archive of the Pope, and it has gradually offered access to materials to an increasing number of researchers. See https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/motu_proprio/documents/papa-francesco-motu-proprio-20191022_archivio-apostolico-vaticano.html (accessed May 16, 2021).

37. Alessandra Gonzato, Lux In Arcana. The Vatican Secret Archives Reveals Itself. Exhibition Catalogue. (Rome: Palombi Editore, 2012).

38. See “Rise and Fall of a Draftsman, The Lequeu Legacy at the National Library of France” by Elisa Boeri in Goffi, The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models.

39. See for example, “After the Original (the Afterimage). High Costs, low roads and circumventions” by Marcia Feuerstein about the archival collection of the works of Oskar Schlemmer, and also “The Secret Afterlife of Three Drawings and the Replica They Spawned” by Adam Sharr in Goffi, The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models.

40. The 1996 Code of Ethics of the International Council on Archives states in the second article that archivists “should cooperate to ensure the preservation of records in the most appropriate repository.” https://www.ica.org/sites/default/files/ICA_1996-09-06_code%20of%20ethics_EN.pdf (accessed May 16, 2021).

References

- Angeleti, Gabriela. 2019. “Jair Bolsonaro’s Government Extinguishes Brazilian Ministry of Culture.” The Art Newspaper, January 9. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/brazilian-culture-ministry-bolsonaro-osmar-terra.

- Arrhenius, Thordis, Mari Lending, et al. 2014. Place and Displacement Exhibiting Architecture. Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers.

- Baretti, Giuseppe Marco Antonio. 1757. The Italian Library. Containing an Account of the Lives and Works of the Most Valuable Authors of Italy: With a Preface, Exhibiting the Changes of the Tuscan Language, from the Barbarous Ages to the Present Time. Londra: A. Millar.

- Biettencourt, Ela. 2021. “As Fires Consume Brazilian Cultural Heritage, Could Cinemateca Brasileira Be Next?” Frieze, May 10. https://www.frieze.com/article/fires-consume-brazilian-cultural-heritage-could-cinemateca-brasileira-be-next.

- Carpo, Mario. 2017. “Building with Geometry, Drawing with Numbers.” In When Is the Digital in Architecture?, edited by Andrew Goodhouse, 33–44. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Cook, Terry. 2000. “Archival Science and Postmodernism: New Formulations for Old Concepts.” Archival Science 1, no. 1: 3–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435636.

- Dekker, Annet, ed. 2010. Archive2020. Sustainable Archiving of Born-Digital Cultural Content. Amsterdam: Virtueel Platform.

- Dekker, Annet. 2018. Collecting and Conserving Net Art: Moving Beyond Conventional Methods. London: Routledge.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1995. “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression.” Diacritics 25, no. 2: 9–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/465144.

- Di Lieto, Alba. 2006. I Disegni di Carlo Scarpa per Castelvecchio. Venezia: Marsilio.

- Di Lieto, Alba. Forthcoming 2021. “A Well Sited Archive. The Carlo Scarpa Archive at the Castelvecchio Museum.” The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models. From Translating to Archiving, Collecting and Displaying, edited by Federica Goffi. London and New York: Routledge.

- Evans, Robin. 1997. Translations From Drawing to Building and Other Essays. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- Frascari, Marco. 1981. “The Tell-the-Tale Detail.” VIA no. 7: 22–37.

- Frascari, Marco. 1991. Monsters of Architecture: Anthropomorphism in Architectural Theory. Savage, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Frascari, Marco. 2007. “Horizons at the Drafting Table: Filarete and Steinberg.” In Chora 5: Intervals in the Philosophy of Architecture, edited by Alberto Pérez-Gómez and Stephen Parcell. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Frascari, Marco. 2017. Marco Frascari’s Dreamhouse: A Theory of Imagination, edited by Federica Goffi. London: Routledge.

- Goffi, Federica. 2013. Time Matter(s): Invention and Re-Imagination in Built Conservation. The Unfinished Drawing and Building of St. Peter’s, the Vatican. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate.

- Goffi, Federica. 2018. “Translations and Dislocations of Architectural Media at the Fabric of St. Peter’s in the Vatican.” Architectural Research Quarterly 22, no. 4: 325–338. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1359135518000660.

- Goffi, Federica. 2022. The Routledge Companion on Architectural Drawings and Models: From Translating to Archiving, Collecting and Displaying. London: Routledge.

- Gonzato, Alessandra. 2012. Lux in Arcana. The Vatican Secret Archives Reveals Itself. Exhibition Catalogue. Rome: Palombi Editore.

- Harris, John. 1989. “Storehouses of Knowledge: The origins of the Contemporary Architectural Museum.” In Canadian Center for Architecture, Building and Gardens, edited by Larry Richards, 15–32. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Harris, Verne. 2005. “Archives, Politics and Justice.” In Political Pressure and the Archival Record, edited by Margaret Procter, Michael Cook, and Caroline Williams, 173–182. Chicago: Society of Architectural Archivists.

- Holton, Alexander. 2006. “The Working Space of the Medieval Master Mason: The Tracing Houses of York Minster and Wells Cathedral.” Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Construction History II, 1579–1597.

- Jimerson, Randall C. 2007. “Archives for All: Professional Responsibilities and Social Justice.” The American Archivist 70, (Fall/Winter): 252–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.70.2.5n20760751v643m7.

- Katz, Brigit. 2019. “Brazil Dissolves Its Ministry of Culture, Smithsonian Magazine.” January 10. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/brazils-new-government-has-dissolved-countrys-culture-ministry-180971236/.

- Kauffman, Jordan. 2018. Drawing on Architecture: The Object of Lines, 1970–1990. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Latour, Bruno. 1986. “Visualization and Cognition. Drawing Things Together.” In Knowledge and Society Studies in the Sociology of Culture Past and Present, edited by Henrika Kuklick and Elizabeth Long, 1–40. Greenwich, CT: Jay Press.

- Lowry, James. 2017. Displaced Archives. London: Routledge.

- Mousavi, Behrang. 2021. “The future of Digital sustainability.” https://collectie.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en/collection-news/future-digital-sustainability.

- Neggers, Frans. 2020. “Setting up Het Nieuwe Instituut’s Digital Archive.” February 17. https://collectie.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en/preservation/setting-het-nieuwe-instituuts-digital-archive.

- Pagano, Sergio. 2009. I Documenti Vaticani Del Processo Di Galileo Galilei (1611–1741). Vatican: Archivio Segreto Vaticano.

- Pekonen, Eeva Liisa. 2018. Exhibit A: Exhibitions That Transformed Architecture, 1948–2000. London: Phaidon Press.

- Pekonen, Eeva Liisa, Carson Chand, and David Andrew Tasman, eds. 2015. Exhibiting Architecture: A Paradox? New Haven: Actar, Yale School of Architecture.

- Pirazzoli, Giacomo. 2020. “Mendes da Rocha, gli archivi e le ferite coloniali del Brasile, Il Giornale dell’Architettura.” September 23. https://ilgiornaledellarchitettura.com/2020/09/23/mendes-da-rocha-gli-archivi-e-le-ferite-coloniali-del-brasile.

- Raffoul, François and Eric Nelson, eds. 2009. Rethinking Facticity. Albany: State University of New York.

- Ricci, Giulia. 2020. “Paulo Mendes da Rocha’s Archive is Now in Portugal (and Not Without Criticism).” Domus, September 11. https://www.domusweb.it/en/architecture/2020/09/11/paulo-mendes-da-rochas-archive-is-flying-to-casa-da-arquitectura-portugal-and-not-without-criticism.html.

- Schlögel, Karl. 2016. In Space We Read Time: On the History of Civilization and Geopolitics, translated by Gerrit Jackson. New York: Bard Graduate Center.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2010. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.