Abstract

The article explores the relationship between Baukunst and Zeitwille in the practice and pedagogy of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and the significance of the notions of civilization and culture for his philosophy of education and design practice. Focusing on the negation of metropolitan life and mise en scene of architectural space as its starting point, it examines how Georg Simmel’s notion of objectivity could be related to Mies’s understanding of civilization. Its key insight is to recognize that Mie’s practice and pedagogy was directed by the idea that architecture should capture the driving force of civilization. The paper also summarizes the foundational concepts of Mies’s curriculum in Chicago. It aims to highlight the importance of the notions of Zeitwille and impersonality in Mies van der Rohe’s thought and to tease apart the tension between the impersonality and the role of the autonomous individual during the modernist era.

Introduction

The article argues that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s agenda in both design and teaching was based on his conviction that his designs could achieve timeless and universal validity, only if he were able to capture the specificity of the Zeitwille. It explains that Mies’s simultaneous interest in impersonality and the autonomous individual is pivotal for understanding the tension between universality and individuality in his thought. The paradox at the center of this article is that while Mies believed in the existence of a universal visual language, he also placed particular emphasis on the role of the autonomous individual in architecture. The article draws upon George Simmel’s understanding the relationship between culture and the individual in order to interpret this paradox characterizing Mies’s thought.

One of the key principles of modernism was the concept of a universally understandable visual language. In the framework of this endeavor to shape a universal language, many of the modernist architects and theorists, including Sigfried Gideon, Nikolaus Pevsner, and Serge Chermayeff drew upon the work of philosophers such as Oswald Spengler. This article explores Mies’s specific perspective on these general ideas common to modernist architects. It analyses his representations of interior spaces, such as those for his Court house projects (c.1934 and c.1938) and the Museum for a Small City project (1941–1943). These interiors shed light on the peculiarities of Mies’ approach to modernism’s generally accepted concern for universality. Mies’s simultaneous interest in individuality and universality was related to Simmel’s conception of the binary relationship between “subjective life” and the “its contents”.Footnote1

The article links Mies’s representations to Nietzsche’s theory and to Simmel’s understanding of culture and spirituality. The concept of negation functions as the common denominator that relates the design of Barcelona pavilion to Nietzsche’s and Simmel’s approaches. The “negativeness” toward the metropolis that characterizes Barcelona pavilion is not far from the “representational living” (Ausstellungswohnen) enhanced by the design of Tugendhat House. The “representational living” promoted through the austerity of the design of Tugendhat House had a liberating impact on its inhabitants that goes hand in hand with the “negativeness” toward metropolis characterizing not only the design of Barcelona pavilion, but also in the representations for Court house projects, Resor House project (1939), and the Museum for a Small City project. The liberating force of Mies’s representations and designs is linked to his understanding of teaching as an organic unfolding of spiritual and cultural relationship and to his preoccupation with the preservation of every individual’s autonomy. Mies’s concern about preserving the autonomy of external culture and the social forces of a given historical period echoes Simmel’s theory.Footnote2

Contextualizing Mies van der Rohe’s conception of Zeitwille

Mies often designed vast open spaces, which represented the universal value of civic life. Mies’s interiors were designed with the intention of helping inhabitants to distance themselves from the chaos of the city. Mies understood Baukunst as an action. He considered it to be a result of the Zeitwille as it becomes evident in his article entitled “Baukunst und Zeitwille!” published in Der Querschnitt in 1924.Footnote3 In this article one can read his famous aphorism “Architecture is the will of time in space.” The German and original version of this aphorism is: “Baukunst ist raumgefaßter Zeitwille”, while the term Zeitwille expresses simultaneously a Schopenhauerian “will of the age” and a “will of time.” It would be interesting to juxtapose the notion of Zeitwille with that of Kunstwollen and Zeitgeist. In Maike Oergel’s recent study the concept of Zeitgeist is related to the “formation of modern politics.” The term is said to “capture key aspects of how ideas are disseminated within societies and across border, providing a way of reading history horizontally”.Footnote4 This connection of the Zeitgeist to the intention to disseminate ideas universally could be related to Mies’s understanding of universality.

As Hazel Conway and Rowan Roenisch highlight, “[i]n an attempt to establish modernism as the only true style, early twentieth-century historians such as Nikolaus Pevsner and Sigfried Giedion employed the concept of the Zeitgeist”.Footnote5 Nikolaus Pevsner “interpreted the styles of the past as the inevitable outcome of what he conceived as their social and political Zeitgeist”.Footnote6 David Watkin characterizes Mies’s conception of Zeitwille as a “blend of Lethaby and the Zeitgeist into a menacing vision of the depersonalised, secular, mechanistic future”.Footnote7 Given that the notion of Zeitwille implies a nonstop process of becoming which is inherent in life; a comprehension of architecture as Zeitwille implies a perception of architectural representation as a snapshot of a continuous process of transformation. Zeitwille implies a state of continuous becoming and a state of action. Mies’s understanding of Baukunst as Zeitwille is characterized by the following ambiguity: on the one hand, it shows that Mies was attracted by man’s capacity to convert his spiritual energy into something tangible, such as a building, and, on the other hand, it demonstrates that he was interested in the impact that products of human creation can have on civilization.

Oswald Spengler’s work was influential on many modernists.Footnote8 For instance, Oswald Spengler’s Man and Technics: A Contribution to a Philosophy of Life.Footnote9 had an important impact on Sigfried Giedion’s Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History.Footnote10 The impact of Spengler’s work of Mies is of great importance for understanding Mies’s conception of Baukunst as Zeitwille. Spengler declared, in The Decline of the West, that “[e]very philosophy is the expression of its own and only its own time.” He rejected the distinction “between perishable and imperishable doctrines” and replaces it with the distinction “between doctrines which live their day and doctrines which never live at all.” Spengler believed in the capacity of “philosophy [to] […] absorb the entire content of an epoch.” For him, the main criterion for evaluating the potential and the eminence of a doctrine was “its necessity to life”.Footnote11 In 1959, during his presentation of The Commander’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Mies underscored his conviction that “architecture belongs to an Epoch.” He claimed that he believed it would “take fifty more years to clarify the relationship of architecture to the epoch” and that “[t]his will be the business of a new generation”.Footnote12 Konrad Wachsmann notes in 1952, in Arts and Architecture, regarding the new conception of inhabitants that is implied in Mies’s interior perspective views and their relationship to the will of epoch: “Thus he paves the way for anonymous building which will enable sensible solutions of modern problems to be achieved”.Footnote13

Many of his representations that played a significant role in the dissemination of his work were produced in collaboration with Lilly Reich, before his departure to the United States, and in collaboration with his students or his employees after his settlement in Chicago. For instance, given that Lilly Reich and Mies collaborated closely between 1926 and 1938, her role in the design of the Barcelona Pavilion and Tugendhat House should not be underestimated.Footnote14 The tendency of both Mies and Lilly Reich to avoid taking an explicit political position could be interpreted in relation to a generalized stance developed in Germany, since the late nineteenth century, around German Idealism, and especially around the notions of Bildung and Kultur.Footnote15 Esther da Costa Meyer relates this unpolitical attitude to Thomas Mann’s book entitled Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen [Reflections of a Non- political Man] published in 1918.Footnote16 Acknowledging Reich’s role is useful for placing Mies’s work within a broader cultural context. Mies’s simultaneous interest in impersonality and the autonomous individual should be understood in relation to the perspectives that were at center of architectural and artistic debates in Germany at the time.

The ambiguity of Mies van der Rohe’s simultaneous interest in impersonality and the autonomous individual

Central for Mies’s work was the phenomenon of inhabitants distancing themselves from the chaos of the city, which is a particular effect of his interiors. This trait of his interiors should be associated with his belief in the autonomous individual and his conviction that in “town and city living […] privacy is a very important requirement”.Footnote17 Mies’s interiors function as fields within which the subjects are autonomous individuals, and as mechanisms permitting to overcome the tension – characterizing the modern metropolis – between the frenetic city and the private bourgeois dwelling. They could be perceived as indoor fragments of the metropolis. The way he represented his interiors, blending linear perspective and photomontage, intensifies the sensation of leaving behind the chaos of the metropolis.

Mies privileged the use of perspective as mode of representation, despite his predilection for the avant-garde, anti-subjectivist tendencies, which rejected the use of perspective and favored the use of axonometric representation or other modes opposed to the assumptions of perspective. Mies used perspective as his main visualizing tool against the declared preference of De Stijl, El Lissitzky and Bauhaus’s for axonometric representation. However, many of his perspective drawings were based on the distortion of certain conventions of perspective. Mies van der Rohe, despite the fact that he preferred objectivity, he did not privilege axonometric projection.

In “The Preconditions of Architectural Work” (1928), Mies claims that “[t]he act of the autonomous individual becomes ever more important”.Footnote18 As Robin Schuldenfrei notes, the “phenomenon, of the inhabitant set apart from his surroundings, was a particular effect of Mies’s interiors”.Footnote19 Schuldenfrei associates this aspect of Mies’s way of representing interiors with his belief “in the autonomous individual”.Footnote20 The place of the “autonomous individual” in Mies’s thought is an aspect that needs to be examined attentively, if we wish to understand the ambiguity between universality and individuality in his thought. Mies gives credence to the acts of the autonomous individual, but mistrusts the endeavor to “express individuality in architecture”, as is evident when he affirms that “[t]o try to express individuality in architecture is a complete misunderstanding of the problem”.Footnote21

For Mies, individuality and autonomous individual are two different things. The way Kant and Nietzsche conceive the notion of autonomous individual is pivotal for understanding the distinction between individuality and autonomous individual in Mies’s thought. Nietzsche, while appropriating Kant’s notion of autonomy, rejects “its link to the categorical imperative and the ‘formal constraints’ interpretation of morality”.Footnote22 In order to understand the differences between Kant’s and Nietzsche’s conception of the autonomous individual, we could juxtapose the Kantian rule “act always according to that maxim whose universality as a law you can at the same time will”Footnote23 to the Nietzschean rule “act always according to that maxim you can at the same time will as eternally returning.”

Deleuze notes regarding the conception of “sovereign” or “autonomous” individual, in Nietzsche’s second essay contained in his book entitled On the Genealogy of Morals, that it is “liberated […] from morality of customs, autonomous and supramoral (for ‘autonomous’ and ‘moral’ are mutually exclusive), in short, the man who has his own independent, protracted will”.Footnote24 Deleuze’s claim that “[i]n Nietzsche […] the autonomous individual is [simultaneously] […] the author and the actor”Footnote25 relates to Mies’s idea of the autonomous individual. We could claim that Mies was favorable toward acts that were expressions of autonomous individuals but negative toward individual means.

The individual’s autonomy preoccupied not only Mies, but Georg Simmel as well. This common interest between Mies and Simmel’s ideas is significant for understanding the differences between the concept of autonomous individual and that of individual means. Simmel introduced “The Metropolis and Mental Life” with the following phrase: “The deepest problems of modern life derive from the claim of the individual to preserve the autonomy and individuality of his existence in the face of overwhelming social forces, of historical heritage, of external culture, and of the technique of life.”Footnote26 Mies’s concern about the autonomous individual is related to his modes of representation, in the sense that his visualization strategies provoked a specific perception of his interiors.

Baukunst as Zeitwille and the dualism between object and culture

Mies’s understanding of Baukunst as Zeitwille should be understood in relation to his interest in man’s capacity to convert his spiritual energy into something tangible, such as a building. In parallel, he was interested in the impact that products of human creation can have on civilization. This is very close to the binary relationship between “subjective life” and the “its contents”, as described by Simmel, in “On the Concept and the Tragedy of Culture”, where the author examines the “radical contrast: between subjective life, which is restless but finite in time, and its contents, which, once they are created, are fixed but timelessly valid”.Footnote27

Simmel also analyses how culture can help us resolve the dualism between object and culture. Mies’s insistence on the importance of the understanding of architectural praxis as an expression of civilization and the fact that he perceived architecture as an act in “the realm of significance”Footnote28 are compatible with Simmel’s theory. Mies until his late days believed that “architecture must stem from sustaining and driving forces of civilisation.”Footnote29 He was convinced that if the architect, during the procedure of concretizing his ideas, manages to capture the “driving forces of civilization” and convert them into a space assemblage through the process of Baukunst, then the products of human intellect – the architectural artifacts – can acquire a universally and timelessly valid effect on the human intellect. For Mies, in order to achieve this timeless and universal validity, the architect had to grasp the specificity of the Zeitwille.

Georg Simmel examines the notion of objectivity in “On the Concept and the Tragedy of Culture”, where he associates the “potentialities of the objective spirit” with the fact that it “possesses an independent validity.” He claims that this independent validity makes possible its re-subjectivisation after “its successful objectification.” For him, the wealth of the concept of culture “consists in the fact that objective phenomena are included in the process of development of subjects, as ways or means, without, thereby losing their objectivity”.Footnote30 We could argue that Mies understands Baukunst as an objective means, believing that only if Baukunst is based on objectifiable, impersonal and generalizable processes can it allow the subject to appreciate their visual interaction with the built artifact. Mies, in “Baukunst und Zeitwille”, associates Zeitwille with impersonality, declaring: “These buildings are by their very nature totally impersonal. They are our representatives of the will of the epoch. This is their significance. Only so could they become symbols of their time.” He also affirms: “The building-art can only be unlocked from a spiritual centre and can only be understood as a life process”.Footnote31 Mies insisted on the fact that his way differed from any kind of individualistic approach, saying: “I go a different way. I am trying to go an objective way.”Footnote32

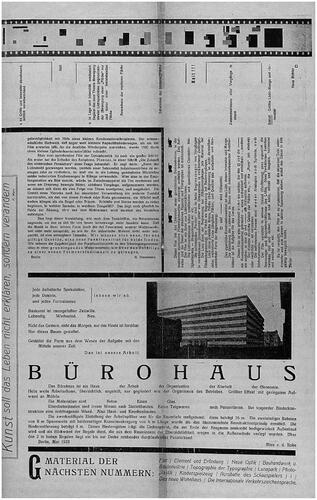

A characteristic of the concept of Zeitwille that should not be overlooked is the fact that it is always in a state of becoming. The process of Baukunst is, thus, perceived by Mies as being in a permanent state of becoming and, for this reason, is conceived as a crystallization of an epoch. Mies declares in “Bürohaus”, published in the first issue of the journal G:

We reject every aesthetic speculation, every doctrine, and every formalism.

The art of building is the will of our time captured in space.

Living. Changing. New.

Not yesterday, not tomorrow, only today can be formed.

Only this practice of building gives form.

Create the form from the nature of the task with the means of our time.

That is our task.Footnote33 ()

Mies’s interest in impersonality should also be related to his belief in the significance of anonymity. In “Baukunst und Zeitwille”, he remarks:

The individual is losing significance; his destiny is no longer what interests us. The decisive achievements in all fields are impersonal and their authors are for the most part unknown. They are part of a trend of our time towards anonymityFootnote34

Mies often referred to the following quotation of Erwin Schrödinger: “But the creative vigour of a general principle depends precisely on its generality.”Footnote35 This quotation brings to mind Mies’s remark, in “Baukunst und Zeitwille”, that “[t]he decisive achievements in all fields are impersonal and their authors are for the most part unknown”.Footnote36 Mies related the idea of innovation to impersonality and insisted on the fact that the notion of renewal in any discipline is “part of the trend of […] time toward anonymity.”Footnote37

Mies’s interest in anonymity and impersonality should be contextualized given that it was at the center of the discourse developed around G: Material zur elementaren Gestaltung. Two artists that were particularly interested in these two notions are Hans Richter and Werner Gräff, who declared in the first issue of the journal: “Today the trend of both artsiness and of life is individualistic and emotional. Operating methodically and impersonally is a cultural challenge today”.Footnote38 They opposed individualistic stance to culture, claiming that in order to contribute to culture creative processes should be impersonal. In the same text, they also refer to the “will to solve the problem of art not from an aestheticizing standpoint but from a general cultural one”.Footnote39

The individual will or intention is peripheral to Mies’s approach since his main concern seems to be the conception of a system that organizes an environment of changes toward progress. Fritz Neumeyer notes, in “A World in Itself: Architecture and Technology”, that for Mies, “the merging of technology and esthetic modernism embodied the promise of a culture suited to the age, one in which form and construction, individual expression and the demands of the times, as well as subjective and objective values would converge into a new identity”.Footnote40

Mies van der Rohe’s representations: non-resolved emptiness as “negativeness” toward Großstadt

The representations that Mies van der Rohe produced for his Court house projects, Resor House project, and the Museum for a Small City project combine the techniques of collage and linear perspective. This combination of collage and linear perspective, the use of grid only in the ground floor, and the absence of frame around the representation intensify the effect of depth in the perception of the observer.Footnote41 They provoke a sensation of extension, which is further reinforced by his choice to place the artworks and surfaces in a dispersed way. Additionally, the lines of the spatial arrangements are less visible than the objects, artworks and statues represented in his architectural representations. The impact of these techniques on the perception of the observers is intensified by the minimal expression of Mies’s representation, pushing the observers of Mies’s representations to imagine their movement through space. The contrast between the discrete symmetrical fond with the grid and the nonsymmetrical organization of the intense surfaces and artworks that are placed on it activates a non-unitary sensation in the way the observers perceive the Mies’s drawings. This non-unitary sensation is in opposition to the unitary dimension of Erwin Panofsky’s understanding of perspective. Mies overcame Panofsky’s conception of the linear perspective apparatus as a “Will to Unification”.Footnote42 The representational ambiguity provoked by Mies’s visualization strategies provokes a non-possibility to take the distance that is inherent in the use of perspective.Footnote43

The stagelike experience of Mies’s interiors is related to a specific attitude of the inhabitant toward the metropolis.Footnote44 Manfredo Tafuri related Mies’s interiors to a “negativeness” toward the metropolis, which brings to mind what Georg Simmel called “blasé attitude” in “The Metropolis and Mental Life”.Footnote45 The reinvention of spatial experience through the movement of users is a characteristic of the Barcelona Pavilion. Tafuri drew a parallel between the visitors’ experience in Mies’s Barcelona Pavilion and stage experience. He related the experience of moving in Barcelona Pavilion to Adolphe Appia’s understanding of the effect of rhythmic geometries on how space is perceived and experienced.Footnote46 The mise en scène of a stagelike experience by Mies in the Barcelona Pavilion activates a specific kind of perception of the relation between the spatial experience of the interior of the Barcelona Pavilion and the city. Mandredo Tafuri shed light on the sensation of “the impossibility of restoring ‘syntheses’” provoked by the perception of the interior of the Barcelona Pavilion as an “empty place of absence”.Footnote47 This sensation is related to a specific kind of “negativeness” toward the metropolis that could be interpreted as a mise en suspension of the synthesis or suspended perception. It brings to mind Robin Evans’ remark that in the case of Mies’s Barcelona Pavilion “[t]he elements are assembled, but not held together”,Footnote48 and Hubert Damisch’s claim that, in Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion, “circulation […] was more visual than pedestrian”.Footnote49 This distinction between visual and pedestrian circulation is useful for comparing Mies’s conception of circulation, which is more visual than pedestrian, to that of Le Corbusier that is simultaneously visual and pedestrian.

Tafuri analyses the effect of non-resolved emptiness of space produced by Mies’s Barcelona Pavilion, noting: “In the absolute silence, the audience at the Barcelona Pavilion can thus ‘be reintegrated’ with that absence”.Footnote50 Mies avoided representing human figures in his interior perspective representations, especially during the first decade after he moved to the United States. The fact that Mies preferred the observers of his images and the users of his spaces not to meet other people while they mentally visualized or physically experienced his spaces shows that he prioritized the solitary experience of space. This choice reinforced that sensation of meditation and of taking distance from the chaotic rhythms of metropolitan life. Walter Riezler juxtaposed the experience based on a conception of the house as a “living machine” (“machine à habiter”), as defined by Le Corbusier, with the experience of the interior space of Mies’s Villa Tugendhat, noting:

no one can escape from the impression of a particular, highly developed spirituality, which reigns in these rooms, a spirituality of a new kind, however, tied to the present in particular ways and which is entirely different therefore from the spirit that one might encounter in spaces of earlier epochs… This is not a “machine for living in”, but a house of true “luxury”, which means that it serves highly elevated needs, and does not cater to some “thrifty”, somehow limited life style.Footnote51

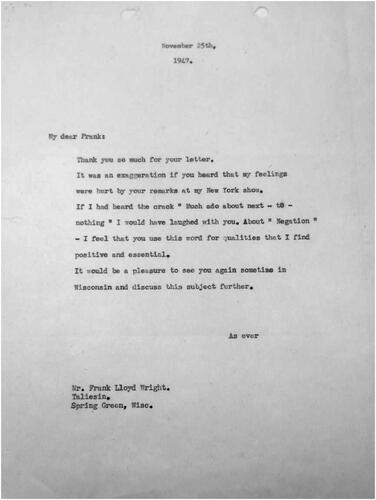

Regarding the Barcelona Pavilion, Mies held the following claim: “I must say that it was the most difficult work which ever confronted me, because I was my own client; I could do what I liked.”Footnote52 Frank Lloyd Wright, in a letter he sent to Mies in 1947, wrote: “the Barcelona Pavilion was your best contribution to the original ‘Negation’”.Footnote53 Mies responded to this letter telling Wright: “About “Negation” – I feel that you use this word for qualities that I find positive and essential”Footnote54 (). The “original ‘Negation’” to which Wright refers in his letter is related to the fact that the Barcelona Pavilion constitutes a reaction “against both classical and modern […] simultaneously and in extremis”,Footnote55 as Robin Evans suggests. The aforementioned exchange between Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe should be interpreted with the context of the theoretical debates of the modernist architects as far as the relationship between modern society and urbanism is concerned.

Figure 2 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, letter to Frank Lloyd Wright, 25 November 1947. Credits: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Box 60, Folder “Wright, Frank Lloyd 1944–1969.” Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Through the design of the Barcelona Pavilion Mies expressed his rejection of both symmetry and asymmetry. Tafuri, analyzing this building, refers to the “‘negativeness’ toward metropolis” and interprets its “‘signs’ as devoid of meaning”.Footnote56 Wright’s comment on the contribution of Mies’s Pavilion “to the original ‘Negation’” and Tafuri’s remark regarding the “negativenesss” of Mies’s stance toward metropolis might seem an oxymoron if we think that “[t]he Elementary design proclaimed by the Berlin circle around Mies, Ludwig Hilberseimer and Hans Richter outwardly promoted an unconditionally affirmative, yes-saying attitude toward reality”.Footnote57.The “negativeness” toward metropolis and the phenomenon of claustrophobia are apparent in Mies’s collages for the Resor House project.Footnote58

Evans notes, in “Mies Van Der Rohe’s Paradoxical Symmetries”: “The problem is that we are being offered two extreme options: either the vertigo of universal extension, or the claustrophobia of living in a crack”.Footnote59 The claustrophobic aspect of Mies’s representations could be related to the concept of Berührungsangst in Simmel’s work. The dimension of Berührungsangst in Mies’s representations is intensified during the first years of his life in the United States. Simmel’s understanding of Berührungsangst as the fear for public spaces could be related to claustrophobic aspect of Mies’s representations. Analyzing the relationship between Simmel’s approach and Mies’s design strategies is useful for understanding the fact that Mies did not design alone in a vacuum, but was responding to a cultural moment and others were responding to him. In this sense, Mies was part of a particular sensibility. A distinction that is important for understanding the vision of Mies is that between the dialectic of Enlightenment and the dialectic of Romanticism, which is analyzed by Peter Murphy and David Roberts in Dialectic of Romanticism.Footnote60

Mies’s Baukunst as an antidote to the chaos of metropolis

For Mies, Baukunst functioned as an antidote to the complexity and the chaos of metropolis. The way he used glass in his architecture should also be understood in relation to his intention to respond to the chaos of metropolis. Characteristically, Francesco Dal Co and Manfredo Tafuri note in Modern Architecture regarding the role of glass in Mies’s work:

But the perfectly homogeneous, broad glassed expanse is also a mirror in the literal sense: the “almost nothing” has become a “large glass,” although imprinted not with the hermetic surrealist ploys of Duchamp, but reflecting images of the urban chaos that surrounds the timeless Miesian purity.Footnote61

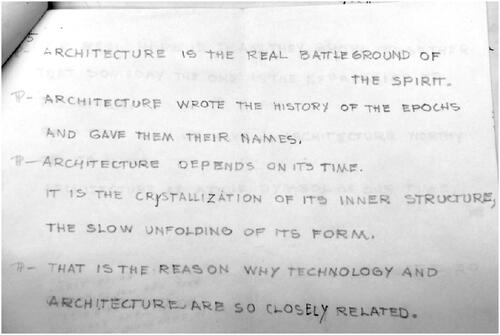

Francesco Dal Co associated Mies’s approach to Nietzsche’s “Beyond Good and Evil”,Footnote62 relating the conflict between the arete (αρετή) of operari and its historical determination in Nietzsche’s thought to the tension between architecture and Baukunst in Mies’s approach. Mies understood Baukunst as an expression of spirit and “[a]rchitecture [as] […] the real battleground of the spirit”Footnote63 (), and elaborated the term Baukunst to capture the practice of building as a spiritualized art.Footnote64 Useful for grasping Mies’s understanding of spirituality is Simmel’s remark that “the subjective spirit has to leave its subjectivity, but not its spirituality, in order to experience the object as a medium for cultivation”.Footnote65 This thesis of Simmel brings to mind Mies van der Rohe’s conviction that the architectural artifacts and the ideals that are intrinsically linked to them can acquire a universally valid status only if their creation is based on the metamorphosis their concepts into something tangible as their architecture.

Figure 3 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s notes for his speeches. Credits: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Box 61, Folder “Mies drafts for speeches, Speeches, Articles and other Writings”, Manuscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Franz Schulze and Edward Windhorst’s argument that Mies “was […] bound up with the esthetic, with art, […] with architecture, but it took on an elevated quality that reached fully to the divine”Footnote66 can help us understand how Mies understood the notion of Baukunst. Mies was interested in form as starting-point and not as result. In the second issue of G: Material zur elementaren Gestaltung (G: Material for Elementary Construction, published in September 1923, Mies wrote, in “Bauen” (“Building”):

We refuse to recognise problems of form but only problems of building

Form is not the aim of our work, but only the result.

Form, by itself, does not exist.

Form as an aim is formalism, and that we reject…

Essentially our task is to free the practice of building from the control of aesthetic speculators and restore it to what it should exclusively be: Building.Footnote67

Mies insisted on the fact that for him the most significant phase of the design process was the “starting point of the form-giving process.” He associated the significance of the starting point of architectural design process to life. He distinguished two types of architectural forms: those that derive from life and those do not derive from life. This becomes evident from what he wrote in a letter he sent to Walt Riezler: “We want to open ourselves to life and seize it. Life is what matters in all the fullness of its spiritual and concrete relations. We do not value the result but the starting point of the form-giving process. It in particular reveals whether form was arrived at from the direction of life or for its own sake”.Footnote68

Representational living and the capacity of space to stimulate the intellect

The concept of representational living is pivotal for understanding Mies' interiors. Representational living was linked to the cultural criticism of Walter Benjamin as well as the architecture of Adolf Loos. Walter Riezler’s article in Die Form provoked the reactions of Justus Bier, Roger Ginsburger and Grete and Fritz Tugendhat, who also published articles commenting on the same building in the same journal.Footnote69 What these exchanges reveal is that Mies’s Villa Tugendhat activated a new mode of inhabiting domestic space. Bier, in his provocative article entitled “Can one live in the Tugendhat House?” (“Kann man im Haus Tugendhat wohnen?”) associated the living experience in the Villa Tugendhat with an “ostentatious living” (Paradewohnen) and a “representational living” (Ausstellungswohnen). According to him, the special characteristic of this new mode of inhabitation was its capacity “to lead a kind of representational living and eventually overwhelm the inhabitants’ real lives”.Footnote70 Grete and Fritz Tugendhat, Mies’s clients and first inhabitants of the house, responded to Bier and Ginsburger’s critiques, asserting that their experience of the spaces of the Tugendhat house was “overwhelming but in a liberating sense.” They related the liberating force of the space of the house to its austerity, claiming that “[t]his austerity makes it impossible to spend your time just relaxing and letting yourself go, and it is precisely this being forced to do something else which people, exhausted and left empty by their working lives, need and find liberating today.”Footnote71 Useful for understanding the place of dweller in Mies’s thought is the work of Hans Prinzhorn.Footnote72 The fact that the two men were friends should also be taken into account.

We can juxtapose the concept of the “machine for living in” (“machine à habiter”) in Le Corbusier’s thought and that of the “meditating machine” (“machine à méditer”) in Mies’s approach, drawing upon Richard Padovan’s “Machine à Méditer”, where the author claims that Mies desired to convert buildings into objects of meditation.Footnote73 The following words of Mies confirm his desire to create objects that pushed him to think and to further activate his intellect: “I want to examine my thoughts in action…. I want to do something in order to be able to think.”Footnote74 One could relate the “representational living” to Mies’s desire concerning the capacity of space to further stimulate the intellect through action. The attention that Mies paid to the intellect becomes evident in an interview he gave to some students of the School of Design of North Carolina State College, in 1952: “The shock is emotional but the projection into reality is by the intellect”.Footnote75

Teaching as an organic unfolding of spiritual and cultural relationships

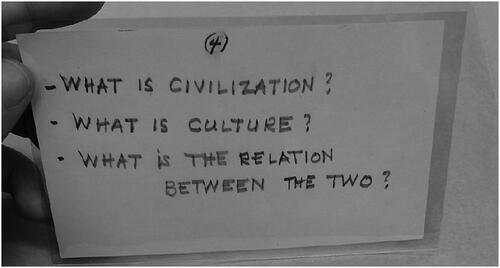

Mies's ideas about the autonomous individual and timeless architecture had an important impact on his conception of architectural education. This is evident in a letter from Mies to Henry T. Heald in December 1937, in which Mies claimed that the curriculum he proposed “through its systematic structure leads an organic unfolding of spiritual and cultural relationships”.Footnote76 In the same letter, he also declared that “[c]ulture as the harmonious relationship of man with his environment and architecture as the necessary manifestation of this relationship is the meaning and goal of the course of studies”.Footnote77 This quotation makes the importance of culture for his pedagogical agenda clear (). He continued writing:

Figure 4 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s notes for his speeches. Credits: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Box 61, Folder “Mies drafts for speeches, Speeches, Articles and other Writings”, Manuscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

The accompanying program is the unfolding of this plan.

Step I is an investigation into the nature of materials and their truthful expression. Step II teaches the nature of functions and their truthful fulfilment. Step III: on the basis of these technical and utilitarian studies begins the actual creative work in architectureFootnote78

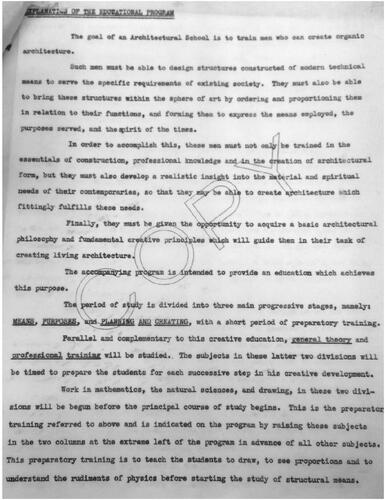

Mies’s curriculum at the Department of Architecture of the Armor Institute of Technology, which would be renamed Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), moved from “Means” to “Purposes” to “Planning and Creating”, placing particular emphasis on the different successive phases of the pedagogical process, and the significance that the notions of civilization, culture and Zeitwille and . Mies divided the curriculum into three main progressive stages, that would be preceded by a short period of “preparatory training.” This was influenced by the so-called Vorkurs, the preliminary course at the Bauhaus. For Mies, the main components of “preparatory training” would be mathematics, natural sciences and drawing. In parallel, he considered that the main objective of the preparatory training would be “to teach the students to draw, to see proportions and to understand the rudiments of physics before starting the study of structural means”.Footnote79

Figure 5 Program for Architectural Education, Illinois Institute of Technology, 1938. Courtesy of Brenner Danforth Rockwell.

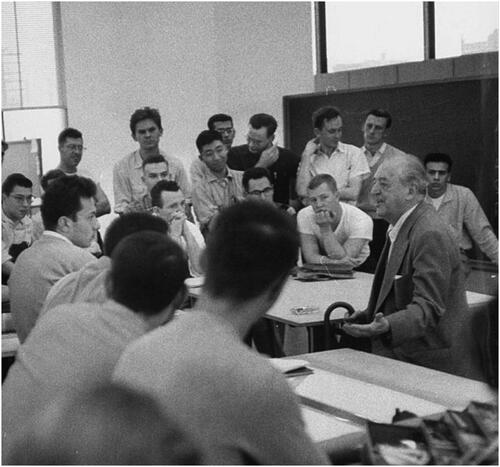

Figure 6 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with his students at IIT discussing some problems they have come up in their individual projects. While emphasizing fundamental principles of architecture, he reminds them that “God is in the details.” Photograph taken by Frank Scherschel on 1 November 1956. Credit: Getty Images.

Walter Peterhans, who used to teach photography courses at the Bauhaus and was invited by Mies to join the faculty of the Department of Architecture of the Armor Institute of Technology, started teaching the “Visual Training” course there in 1938. He placed particular emphasis on the role of visual perception for architectural practice. Mies, in “Program for Architectural Education”, commented on the logic of the “Visual Training” course. He believed that the “Visual Training” course served “to train the eye and sense of design and to foster esthetic appreciation in the world of proportions, forms, colors, textures and spaces”.Footnote80 In parallel, he prioritized “visual training” over freehand drawing. For him, “visual training” was “indispensable as a means of recording an idea”, while freehand drawing should be understood as “a means of fostering insight and stimulating ideas”.Footnote81 Mies described the philosophy of the “Visual Training” course as follows:

Visual Training is a course which serves to train the eye and sense of design and to foster aesthetic appreciation in the world of proportions, forms, colors, textures and spaces. We attach incomparably more importance to visual training than freehand drawing or drawing from nude. Sketching is indispensable as a means of recording an idea, clarifying it and communicating to others; but as a means of fostering insight and stimulating ideas visual training has quickly shown itself to be a greatly superior method since it begins as a deeper level in training the eye for architectureFootnote82

Undoubtedly, the strategies employed in the Vorkurs at the Bauhaus constitute the precedents for the exercises given to the students in the framework of the “Visual Training” course. According to Peterhans, who taught this course, “Visual Training […] [was] a […] conscious education for seeing and forming, for esthetic experience in the world of proportion, shape, color, texture, space”.Footnote83 Its philosophy was based on the conviction that sensory knowledge can be a path to insight. What is of particular interest for this paper is the fact that the innovative quality of the “Visual Training” course taught by Peterhans lay in his intention to reconcile esthetic and scientific perspectives instead of prioritizing one over the other. Another distinctive characteristic of the didactic vision behind “Visual Training” is the fact that it treated the students’ own work as its main material. Thus, students were invited to sharpen their visual perception on their own artefactual products, and not on preexisting cases or works of major architects that already occupied an important position within architectural epistemology.

In a letter that accompanied the “Explanation of the Educational Program” (), which Mies sent to Henry T. Heald on 31 March 1938, he wrote: “I lay special worth upon the sharpening of the powers of observation and the development of the capacity to create imaginatively as well as a general control of the quality of the students’ work by photographic methods”.Footnote84 Mies believed that the teaching of “Visual Training” by Peterhans could serve this purpose.

Figure 7 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Explanation of the Educational Program sent to Henry T. Heald on 31 March 1938. Credits: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, BOX 5. Manuscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

The “means” were divided into material, construction and form. Informative for understanding the philosophy of not only the “preparatory training”, but also of the whole educational programme that Mies suggested as newly-appointed Director of the Armor Institute of Technology is what he called “General theory”, which included the six following sub-categories: mathematics and natural sciences, the nature of man, the nature of human society, analysis of technics, analysis of culture, and culture as obligatory task. Mies’s curriculum was based on the idea that during the first phase of education, the students should focus on the development of their “drawing ability and visual perception, progressing through Construction as an understanding of principles, acquiring the technical knowledge of related Engineering and studying Function as a way of understanding problems and building types”.Footnote85 Therefore, during the first three years the pedagogical agenda was concentrated on the sharpening of visual and spatial perception, while the last two years of education were conceived as serving to enhance the synthesis of the skills acquired previously.

Central for his teaching and design strategy was the relationship between culture and civilization. Mies’s hostility toward subjectivity in art is characterized by a paradox: despite his rejection of individualized esthetics, he asserts in the first issue of the journal G that “we need an inner order of our existence”.Footnote86 This inner order of our existence, which Mies refers at the same moment that he rejects individualized esthetics, reveals the paradoxical relationship between subjectivity and objectivity as Simmel describes it. An aspect of Simmel’s approach, which reveals its affinities with Mies’s point view, is the concern about the double gesture of the “objectivization of the subject and the subjectivization of the object”, in Philosophie der Kultur.Footnote87 This connection between Simmel and Mie’s perspective is further legitimized by the fact that Mies owned Simmel’s Philosophie der Kultur. Mies van der Rohe poses the following questions: “What is civilization? What is culture? What is the relation between the two?”Footnote88 The distinction between civilization and culture was at the center of Oswald Spengler’s thought, as it becomes evident in his following words:

Civilization is the ultimate destiny of the Culture… Civilizations are the most external and artificial states of which a species of developed humanity is capable. They are a conclusion, the thing-become succeeding the thing-becoming, death following life, rigidity following expansion… petrifying world-city following mother-earth and the spiritual childhoodFootnote89

Conclusions

For Mies, clarity was important not only in terms of its application to the design process, but for pedagogy as well. This becomes evident from what he declared in his inaugural address as Director of Architecture at Armor Institute of Technology, in 1938, in which he underscored the significance of “rational clarity” for education. More specifically, he declared that “[e]ducation must lead us from irresponsible opinion to true responsible judgment.” His pedagogical vision was characterized by the intention to replace “chance and arbitrariness” with “rational clarity and intellectual order.” Footnote90 A meeting point between Mies’s design approach and his teaching philosophy is the interest in promoting clarity. He understood teaching as a means for clarifying his ideas. This becomes evident in what he declared a year before his death, in January 1968:

Teaching forced me to clarify my architectural Ideas. The work made it possible to test their validity. Teaching and working have convinced me, above all, of the need for clarity in thought and action. Without clarity, there can be no understanding. And without understanding, there can be no direction — only confusionFootnote91

The main principle on which Mies’s curriculum was based was the promotion of clarity and order. Regarding the importance of clarity for education, he remarked: “If our schools could get to the root of the problem and develop within the student a clear method of working, we could have given him a worthwhile five years”.Footnote92 To understand Mies’s conception of clarity it would be useful to relate it to the debates around clarity in the pages of G. Zeitschrift für elementare. Regarding the theme of clarity Théo van Doesburg declares in the first issue of the aforementioned journal:

What we demand of art is CLARITY, and this demand can never be satisfied if artists use individualistic means. Clarity can only follow from discipline of means, and this discipline leads to the generalization of means. Generalization of means leads to elemental, monumental form-creation.Footnote93

Clarity in the sense described in the journal G is associated with the invention of generalizable means. Mies’s interest in generalizable means and the rejection of individualistic is related to his concern about objectivity as Georg Simmel describes it in “The Stranger”.Footnote94 Mies believed that one of the most important criteria for judging the practice of architects and educators in the field of architecture is the clarity of their working methods and the knowledge of the tools of the discipline. Mies’s belief in the necessity of an extreme discipline of the design process could be associated with St Thomas Aquinas’s conviction that “[r]eason is the first principle of all human work.” Footnote95St Thomas Aquinas agrees with Aristotle’s point of view in Nicomachean Ethics (Ηθικά Νικομάχεια) according to which ethical is what is in accordance with right reason.Footnote96 In this sense, we could claim that, in Mies’s case, good architecture is assimilated to an architecture that is conceived according to right reason. Mies declared: “I don’t want to be interesting – I want to be good!”Footnote97 This declaration, apart from an echo of St Thomas Aquinas and Aristotle, can also be interpreted in relation to Nietzsche’s approach in Will to Power, where the latter claims that it is important to avoid any confusion between the good and the beautiful. More precisely, Nietzsche states: “For a philosopher to say, ‘the good and the beautiful are one,’ is infamy.”Footnote98 Mies, as Nietzsche, refused to assimilate good and beautiful. The belief in the extreme discipline of the design process, which characterizes Mies’s point of view, could be interpreted as an incorporation into architecture of the idea of St Thomas Aquinas that “Reason is the first principle of all human work.”Footnote99 For both Aquinas and Aristotle behaving according to reason is the first principle of ethics.

Mies understood Baukunst as an expression of spirit. The elaboration of the term Baukunst permitted him to capture the practice of building as a spiritualized art. It also helped him to grasp the idea of spiritual pertinence, which was, for him, the means to freedom and clarity. In parallel, he “saw architecture as the expression of a certain Zeitwille”.Footnote100 Mies’s interest in the spatial expression of Zeitwille is related to his conviction that Zeitwille can be apprehended spatially.Footnote101 As Jean-Louis Cohen has remarked, Mies believed that “the teaching of architecture should focus on the importance of values ‘anchored in the spiritual nature of man’”.Footnote102 Descartes and Kant claimed that our rational minds impose meanings to the world, while St Thomas Aquinas understood this process in the reverse. The approaches of Descartes, Kant and St Thomas Aquinas can help us understand the relationship between the mental image and the art of building in Mies’s thought, and his belief that “the art of building [arises] out of spiritual things”.Footnote103

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the anonymous reviewers, the editors of Architecture and Culture - particularly to Dr. Jessica Kelly - and Prof. Dr. Jean-Louis Cohen for their very insightful feedback.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marianna Charitonidou

Dr. ir. Marianna Charitonidou is a registered architect, spatial designer, curator, educator and architecture and urban design theorist and historian. Currently, she is a Lecturer at the Chair for the History and Theory of Urban Design of the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta) of ETH Zürich, where she works on her project entitled “The Travelling Architect's Eye: Photography and the Automobile Vision”. Dr. ir. Charitonidou is the curator of the exhibition entitled "The View from the Car: Autopia as a New Perceptual Regime” (https://viewfromcarexhibition.gta.arch.ethz.ch) at ETH Zurich (5 March–15 October 2021). She is also Postdoctoral Research Associate at the School of Architecture of the National Technical University of Athens and the Faculty of Art History and Theory of Athens School of Fine Arts. Email: [email protected]; Website: https://charitonidou.com

Notes

1 Georg Simmel, “On the Concept and the Tragedy of Culture,” in The Conflict in Modern Culture and Other Essays (New York: Teachers College Press, 1968); Simmel, “Der Begriff und die Tragödie der Kultur,” in Philosophie der Kultur Gesammelte Essais (Leipzig: Werner Klinkhardt, 1911), 245–77.

2 Georg Simmel, “Metropolis and Mental Life,” in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. Kurt Wolf (New York: Free Press, 1950), 409; “Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben,” in Die Großstadt. Vorträge und Aufsätze zur Städteausstellung, ed. Theodor Petermann (Dresden: von Zahn und Faensch, 1903), 185.

3 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, “Baukunst und Zeitwille!” Der Querschnitt 4(1) (1924): 31–32.

4 Maike Oergel, Zeitgeist: How Ideas Travel; Politics, Culture and the Public in the Age of Revolution (Culture & Conflict) (Berlin; New York: De Gruyter, 2019).

5 Hazel Conway and Rowan Roenisch, Understanding Architecture: An Introduction to Architecture and Architectural History (London; New York, Routledge, 2005), 46.

6 David Watkin, Morality and Architecture Revisited (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001).

7 Ibid., 44.

8 Ian James Kidd, “Oswald Spengler, Technology, and Human Nature,” The European Legacy, 17, no. 1 (2012): 19–31.

9 Oswald Spengler, Man and Technics: A Contribution to a Philosophy of Life, trans. Charles Francis Atkinson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1976).

10 Sigfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1948).

11 Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, trans. Charles Francis Atkinson (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 31–32.

12 Reply of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to Baron von Lupin’s speech on 2 April 1959 at the Arts Club of Chicago on the occasion of his presentation of The Commander’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Box 61, Folder “Mies drafts for speeches, Speeches, Articles and other Writings,” Manuscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

13 Konrad Wachsmann, “Mies van der Rohe, his Work,” Arts and Architecture 69(38) (1952), 21.

14 See Hermann Blomeier, “Lilly Reich zum Gedächtnis,” Bauen und Wohnen 3, no. 4 (1948): 106–107.

15 Esther da Costa Meyer, “Cruel Metonymies: Lilly Reich's Designs for the 1937 World's Fair,” New German Critique, 76 (1999): 161–189.

16 Thomas Mann, Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen, introduction by Erika Mann (Frankfurt; Main: Fischer, 1956).

17 Mies van der Rohe, letter to Stefano Desideri, 29 January 1962. Mies van der Rohe papers, Box 4, Folder “Personal Correspondence 1930–69 D,” Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

18 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, “The Preconditions of Architectural Work”. Lecture held at the end of February 1928 in the Staatliche Kunstbibliothek Berlin; also on March 5, 1928, at the invitation of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft for Frauenbestrebung (Work Association for the Women's Movement) of the Museumsverein and the Kunstgewerbeschule Stettin in the auditorium of the Marienstiftsgymnasium in Stettin; as well on March 7 at the invitation of the Frankfurter Gesellschaft for Handel, Industria und Wissenschaft (Frankfurt Society for Trade, Industry and Science) in Frankfurt am Main. Unpublished manuscript in the collection of Dirk Lohan, Chicago; see also Fritz Neumeyer, The Artless Word: Mies van der Rohe on the Building Art, trans. Mark Jarzombek (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991), 299–300.

19 Robin Schuldenfrei, “Contra the Großstadt: Mies van der Rohe's Autonomy and Interiority,” in Interiors and Interiority, ed. Beate Söntgen Ewa Lajer-Burcharth (Berlin; Boston: De Guyter, 2016), 287.

20 Ibid.

21 Mies van der Rohe, “Wohin gehen wir nun?” Bauen und Wohnen 15, no. 11 (1960), 391.

22 R. Kevin Hill, Nietzsche's Critiques: The Kantian Foundations of His Thought (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 216.

23 Immanuel Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals: with On a Supposed Right to Lie because of Philanthropic Concerns, trans. James W. Ellington (Indianapolis, IN; Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1993), 42.

24 Gilles Deleuze, Nietzsche and Philosophy, trans. Hugh Tomlinson (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2006), 128.

25 Ibid., 137.

26 Georg Simmel, “Metropolis and Mental Life,” in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. Kurt Wolf (New York: Free Press, 1950), 409; Simmel, “Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben,” in Die Großstadt. Vorträge und Aufsätze zur Städteausstellung, ed. Theodor Petermann (Dresden: von Zahn und Faensch, 1903), 185.

27 Georg Simmel, “On the Concept and the Tragedy of Culture,” in The Conflict in Modern Culture and Other Essays (New York: Teachers College Press, 1968); Simmel, “Der Begriff und die Tragödie der Kultur,” in Philosophie der Kultur Gesammelte Essais (Leipzig: Werner Klinkhardt, 1911), 245–77.

28 Text of an address that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe gave during a dinner on 17 April 1950 at the Blackstone Hotel, Chicago, Illinois. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Box 61, Manuscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

29 Revised version of a speech that Ludwig Mies gave in January 1968. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Box 61, Folder “Speeches, Articles and other writings,” Manuscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

30 Georg Simmel, “On the Concept and the Tragedy of Culture”.

31 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, “Baukunst und Zeitwille!” Der Querschnitt 4, no. 1 (1924): 31–32.

32 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe cited in Moisés Puente, ed., Conversations with Mies Van Der Rohe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008), 59.

33 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, “Bürohaus,” G, 1 (1923), 3.

34 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, “Baukunst und Zeitwille!” Der Querschnitt 4(1) (1924): 31–32.

35 Erwin Schrödinger, 'Nature and the Greeks' and 'Science and Humanism' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 9.

36 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, “Baukunst und Zeitwille!”

37 Ibid.

38 Hans Richter, Werner Gräff, G: Material zur elementaren Gestaltung, 1 (1923), 1.

39 Ibid.

40 Fritz Neumeyer, “A World in Itself: Architecture and Technology,” in Presence of Mies, ed. Detlef Mertins (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994).

41 See also Marianna Charitonidou, “Architecture’s Addressees: Drawing as Investigating Device,” in villardjournal 2 (2020): 91–111. doi:10.2307/j.ctv160btcm.10

42 Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form, trans. Christopher S. Wood (New York: Zone Books, 1991); Panofsky, “Die Perspektive als symbolische Form,” in Vorträge der Bibliothek Warburg 1924–1925, ed. Fritz Saxl (Leipzig; Berlin: B.G. Teubner, 1927), 258–330.

43 Dan Hoffman, “The Receding Horizon of Mies: Work of the Cranbrook Architecture Studio,” in The Presence of Mies, ed. Detlef Mertins (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994).

44 Manfredo Tafuri, “Il teatro come ‘città virtuale.’ Dal Cabaret Voltaire al Totaltheater/The Theatre as a Virtual City: From Appia to the Totaltheater,” Lotus International 17 (1977): 30–53.

45 Simmel, “Metropolis and Mental Life,” 409–24; “Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben,” 185–206.

46 Adolphe Appia, “Ideas on a Reform of Our Mise en Scène,” (1902) in Adolphe Appia: Texts on Theatre, ed. Richard Beacham (London; New York: Routledge, 1993), 59–65.

47 Ibid.

48 Robin Evans, “Mies van der Rohe’s Paradoxical Symmetries,” in Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays (London: Architectural Association, 1997), 242; “Mies van der Rohe’s Paradoxical Symmetries,” AA Files 19 (1990): 56–68.

49 Hubert Damisch, “The Slightest Difference: Mies van der Rohe and the Recontruction of the Barcelona Pavilion,” in Noah’s Ark: Essays on Architecture, ed. Anthony Vidler (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2016), 217.

50 Tafuri, “Il teatro come ‘città virtuale.’ Dal Cabaret Voltaire al Totaltheater/The Theatre as a Virtual City: From Appia to the Totaltheater”.

51 Walter Riezler, “Das Haus Tugendhat in Brünn,” in Die Form: Monatsschrift für gestaltende Arbeit 9 (1931): 321–332.

52 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe cited in Franz Schulze, Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 117.

53 Frank Lloyd Wright, letter to Mies van der Rohe, 25 October 1947. Mies van der Rohe papers, Box 60, Folder “Wright, Frank Lloyd 1944–69,” Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

54 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, letter to Frank Lloyd Wright, 25 November 1947. Mies van der Rohe papers, Box 60, Folder “Wright, Frank Lloyd 1944–69,” Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

55 Evans, “Mies van der Rohe’s Paradoxical Symmetries,” 239.

56 Tafuri, “Il teatro come ‘città virtuale.’ Dal Cabaret Voltaire al Totaltheater/The Theatre as a Virtual City: From Appia to the Totaltheater”.

57 Fritz Neumeyer, “Nietzsche and Modern Architecture in Nietzsche and ‘An Architecture of Our Minds’” , ed. Irving Wohlfarth Alexandre Kostka (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities 1999), 289.

58 Martino Stierli, “Mies Montage,” AA Files 61 (2010), 64.

59 Evans, “Mies van der Rohe’s Paradoxical Symmetries,” 249.

60 Peter Murphy, David Roberts, Dialectic of Romanticism (London; New York: Bloomsbury, 2005).

61 Francesco Dal Co, Manfredo Tafuri, Modern Architecture, trans. Robert Erich Wolf (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1979), 342.

62 Francesco Dal Co, “La culture de Mies considérée à travers ses notes et ses lectures,” in Mies Van der Rohe (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1987), 78; Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, trans. Judith Norman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002); Original edition: Jenseits von Gut und Böse: Vorspiel einer Philosophie der Zukunft (Leipzig: C. G. Naumann, 1886).

63 Text of an address that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe gave during a dinner on 17 April 1950 at the Blackstone Hotel, Chicago, Illinois. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Box 61, Manuscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

64 Luciana Fornari Colombo, “What is life? Exploring Mies van der Rohe's concept of architecture as a life process,” The Journal of Architecture 22, no. 8 (2017): 1267–1286.

65 Georg Simmel, “On the Concept and the Tragedy of Culture,” in The Conflict in Modern Culture and Other Essays (New York: Teachers College Press, 1968), 30.

66 Franz Schulze, Edward Windhorst, Mies van der Rohe. A Critical Biography (Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2014), 173.

67 Mies van der Rohe, “Bauen,” G, 2 (1923), 1.

68 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe cited in Fritz Neumeyer, The Artless Word: Mies van der Rohe on the Building Art, 178.

69 Walter Riezler, “Das Haus Tugendhat in Brünn,” Die Form, 9 (1931): 321–32; Justus Bier, "Kann Haus man im Tugendhat wohnen?” Die Form: Monatsschrift für gestaltende Arbeit, 11 (1931): 392–393; Grete and Fritz Tugendhat, “Die Bewohner des Hauses Tugendhat äußern sich,” Die Form 11 (1931): 437–38.

70 Justus Bier, “Kann Haus man im Tugendhat wohnen?” Die Form: Monatsschrift für gestaltende Arbeit 11 (1931): 392–393; see also Dietrich Neumann, “Can one live in the Tugendhat House?” A Sketch. Wolkenkuckucksheim | Cloud-Cuckoo-Land 32 (2012): 87–99.

71 Grete and Fritz Tugendhat, “Die Bewohner des Hauses Tugendhat äußern sich,” Die Form 11 (1931): 437–38; Reprinted in Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat, Tugendhat House. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2014), 74–77.

72 Hans Prinzhorn, Leib - Seele - Einheit. Ein Kernproblem der neuen Psychologie (Zürich and Potsdam: Müller & Kiepenheuer/Orell Füssli, 1927); see also Tanja Poppelreuter, “Spaces for the elevated personal life: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's concept of the dweller, 1926–1930,” The Journal of Architecture 21, no. 2 (2016): 244–270.

73 Richard Padovan, “Machine à Méditer,” in Mies van der Rohe: Architect as Educator, ed. Rolf Achilles, Kevin Harrington, and Charlotte Myhrum (Chicago: Illinois Institute of Technology, 1986), 17.

74 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe cited in Padovan, “Machine à Méditer,” 17.

75 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, interview given to six students from the School of Design of North Carolina State College in 1952. Mies van der Rohe papers, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

76 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s letter to Henry T. Heald on 1 December 1937. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, BOX 5. Manuscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

77 Ibid.

78 Ibid.

79 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, letter that accompanied the “Explanation of the Educational Program” sent to Henry T. Heald on 31 March 1938. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Manurscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

80 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, “Peterhans’ Seminar für visuelles Training der Architekturabteilung des IIT,” in Mies van der Rohe, Lehre und Schule, ed. Werner Blaser (Basel; Stuttgart: Birkhäuser Verlag, 1977), 34–35.

81 Ibid.

82 Ibid.

83 Kristin Jones, “Research in Architectural Education: Theory and Practice of Visual Training,” Enquiry: The ARCC Journal 13, no. 1 (2016), 12.

84 Ludwig Mies vand der Rohe, letter that accompanied the “Explanation of the Educational Program” sent to Henry T. Heald on 31 March 1938. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Manuscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

85 George Schipporeit, foreword to in Mies van der Rohe: Architect as Educator, ed. Rolf Achilles, Kevin Harrington, and Charlotte Myhrum (Chicago: Illinois Institute of Technology, 1986), 10.

86 Mies van der Rohe, “Bürohaus,” G 1 (1923), 3.

87 Georg Simmel, Philosophie der Kultur (Leipzig: Alfred Kröner Verlag, 1919).

88 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s notes for his speeches. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Manuscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

89 Spengler, The Decline of the West.

90 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, inaugural address as Director of Architecture at Armour Institute of Technology in 1938. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Manuscripts Divisions, Library of Congress, Washington DC.

91 Revised version of a speech that Ludwig Mies gave in January 1968. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe papers, Box 61, Folder “Speeches, Articles and other writings,” Manuscripts division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

92 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, “Wohin gehen wir nun?” Bauen und Wohnen 15, no. 11 (1960), 391.

93 Théo van Doesburg, G 1 (1923): 2; Detlef Mertins, Michael William Jennings, eds., G: An Avant-Garde Journal of Art, Architecture, Design, and Film, 1923–1926 (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2010), 102.

94 Georg Simmel, “The Stranger,” in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. Kurt H. Wolff (New York: The Free Press, 1950).

95 St Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I II, q. 58, a. 2.

96 Aristotle, Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Robert C. Bartlett, Susan D. Collins (Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2012).

97 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in Conversations with Mies Van Der Rohe, ed. Moisés Puente. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008), 56.

98 Friedrich Nietzsche. 1968. The Will to Power, trans. Walter Kaufmann, R. J. Hollingdale (New York: Vintage Books), 435.

99 St Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I II, q. 58, a. 2.

100 Jean-Louis Cohen, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2018), 8.

101 Mies van der Rohe referred to the “the spatially apprehended will of the epoch” [raumgefaßter Zeitwille]; Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, “Bürohaus,” G, 1 (1923), 3.

102 Ibid., 100; Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, inaugural speech as director of the IIT, 20 November 1938, manuscript, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, published in Neumeyer, The Artless Word: Mies van der Rohe on the Building Art, 317.

103 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, unpublished lecture, 17 March 1926, reprinted in Neumeyer, The Artless Word: Mies van der Rohe on the Building Art, 252–256.

References

- Appia, Adolphe. 1993. “Ideas on a Reform of Our Mise en Scène.” In Adolphe Appia: Texts on Theatre, edited by Richard Beacham, 59–65. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

- Aristotle . 2012. Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, translated by Robert C. Bartlett, Susan D. Collins Chicago, IL; London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Bier, Justus. 1931. "Kann Haus man im Tugendhat wohnen?” Die Form: Monatsschrift für gestaltende Arbeit, 11: 392–393.

- Bier, Justus. 1931. “Kann Haus man im Tugendhat wohnen?” Die Form: Monatsschrift für gestaltende Arbeit 11: 392–393.

- Blomeier, Hermann. 1948. “Lilly Reich zum Gedächtnis.” Bauen und Wohnen 3, no. 4: 106–107.

- Charitonidou, Marianna. 2020. “Architecture’s Addressees: Drawing as Investigating Device.” Villardjournal 2: 91–111. doi:10.2307/j.ctv160btcm.10

- Cohen, Jean-Louis. 2018. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 8. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Colombo, Luciana Fornari. 2017. “What is life? Exploring Mies van der Rohe's Concept of Architecture as a Life Process.” The Journal of Architecture 22, no. 8: 1267–1286. doi:10.1080/13602365.2017.1393836

- Conway, Hazel and Rowan Roenisch. 2005. Understanding Architecture: An Introduction to Architecture and Architectural History, 46. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

- da Costa Meyer, Esther. 1999. “Cruel Metonymies: Lilly Reich's Designs for the 1937 World's Fair.” New German Critique, 76: 161–189. doi:10.2307/488661

- Dal Co, Francesco. 1987. “La culture de Mies considérée à travers ses notes et ses lectures.” In Mies Van der Rohe, 78. Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou.

- Dal Co, Francesco and Manfredo Tafuri. 1979. Modern Architecture, translated by Robert Erich Wolf, 342. New York, NY: H. N. Abrams.

- Damisch, Hubert. 2016. “The Slightest Difference: Mies van der Rohe and the Recontruction of the Barcelona Pavilion.” In Noah’s Ark: Essays on Architecture, edited by Anthony Vidler, 217. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Deleuze, Gilles. 2006. Nietzsche and Philosophy, translated by Hugh Tomlinson, 128. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Evans, Robin. 1990. “Mies van der Rohe’s Paradoxical Symmetries.” AA Files 19: 56–68.

- Evans, Robin. 1997. “Mies van der Rohe’s Paradoxical Symmetries.” In Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays, 242. London: Architectural Association.

- Giedion, Sigfried. 1948. Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Grete and Fritz Tugendhat. 1931 “Die Bewohner des Hauses Tugendhat äußern sich.” Die Form 11: 437–38.

- Hammer-Tugendhat, Daniela. 2014. Tugendhat House. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 74–77. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Hill, R. Kevin. 2000. Nietzsche's Critiques: The Kantian Foundations of His Thought, 216. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hoffman, Dan. 1994. “The Receding Horizon of Mies: Work of the Cranbrook Architecture Studio.” In The Presence of Mies, edited by Detlef Mertins. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Jones, Kristin. 2016. “Research in Architectural Education: Theory and Practice of Visual Training.” Enquiry: The ARCC Journal 13, no. 1: 12. doi:10.17831/enq:arcc.v13i2.404

- Kant, Immanuel. 1993. Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals: with On a Supposed Right to Lie because of Philanthropic Concerns, translated by James W. Ellington, 42. Indianapolis, IN; Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc..

- Kidd, Ian James. 2012. “Oswald Spengler, Technology, and Human Nature.” The European Legacy, 17:1: 19–31. doi:10.1080/10848770.2011.640190

- Mann, Thomas. 1956. Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen, introduction by Erika Mann. Frankfurt; Main: Fischer.

- Mertins, Detlef and Michael William Jennings, eds. 2010. G: An Avant-Garde Journal of Art, Architecture, Design, and Film, 1923–1926, 102. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute.

- Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig. 1924. “Baukunst und Zeitwille!” Der Querschnitt 4, no. 1: 31–32.

- Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig. 1960. “Wohin gehen wir nun?” Bauen und Wohnen 15, no. 11, 391.

- Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig. 2008. Conversations with Mies Van Der Rohe, edited by Moisés Puente, 56. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Murphy, Peter and David Roberts. 2005. Dialectic of Romanticism. London; New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

- Neumann, Dietrich. 2012. “Can one live in the Tugendhat House?” A Sketch. Wolkenkuckucksheim | Cloud-Cuckoo-Land 32: 87–99.

- Neumeyer, Fritz. 1991. The Artless Word: Mies van der Rohe on the Building Art, translated by Mark Jarzombek, 299–300. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Neumeyer, Fritz. 1994. “A World in Itself: Architecture and Technology.” In Presence of Mies, edited by Detlef Mertins. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Neumeyer, Fritz. 1999. “Nietzsche and Modern Architecture.” In Nietzsche and ‘An Architecture of Our Minds, edited by Irving Wohlfarth Alexandre Kostka, 289. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1886. Jenseits von Gut und Böse: Vorspiel einer Philosophie der Zukunft. Leipzig: C. G. Naumann.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1968. The Will to Power, translated by Walter Kaufmann, R. J. Hollingdale, 435. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 2002. Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, translated by Judith Norman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oergel, Maike. 2019. Zeitgeist: How Ideas Travel; Politics, Culture and the Public in the Age of Revolution (Culture & Conflict). Berlin; New York, NY: De Gruyter.

- Padovan, Richard. 1986. “Machine à Méditer.” In Mies van der Rohe: Architect as Educator, edited by Rolf Achilles, Kevin Harrington, and Charlotte Myhrum, 17. Chicago, IL: Illinois Institute of Technology.

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1927. “Die Perspektive als symbolische Form.” In Vorträge der Bibliothek Warburg 1924–1925, edited by Fritz Saxl, 258–330. Leipzig; Berlin: B.G. Teubner.

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1991. Perspective as Symbolic Form, translated by Christopher S. Wood. New York, NY: Zone Books.

- Poppelreuter, Tanja. 2016. “Spaces for the elevated personal life: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's concept of the dweller, 1926–1930.” The Journal of Architecture 21, no. 2: 244–270. doi:10.1080/13602365.2016.1160946

- Prinzhorn, Hans. 1927. Leib - Seele - Einheit. Ein Kernproblem der neuen Psychologie. Zürich and Potsdam: Müller & Kiepenheuer/Orell Füssli.

- Puente, Moisés. ed., 2008. Conversations with Mies Van Der Rohe, 59. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Richter, Hans and Werner Gräff. 1923. G: Material zur elementaren Gestaltung, 1: 1.

- Riezler, Walter. 1931. “Das Haus Tugendhat in Brünn.” In Die Form: Monatsschrift für gestaltende Arbeit 9: 321–332.

- Schipporeit, George. 1986. Mies van der Rohe: Architect as Educator, edited by Rolf Achilles, Kevin Harrington, and Charlotte Myhrum, 10. Chicago, IL: Illinois Institute of Technology.

- Schrödinger, Erwin. 2014. 'Nature and the Greeks' and 'Science and Humanism, 9. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schuldenfrei, Robin. 2016. “Contra the Großstadt: Mies van der Rohe's Autonomy and Interiority.” In Interiors and Interiority, edited by Beate Söntgen Ewa Lajer-Burcharth, 287. Berlin; Boston, MA: De Guyter.

- Schulze, Franz. 2012. Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography, 117. Chicago, IL and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Schulze, Franz and Edward Windhorst. 2014. Mies van der Rohe. A Critical Biography, 173. Chicago, IL; London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Simmel, Georg. 1903. “Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben.” In Die Großstadt. Vorträge und Aufsätze zur Städteausstellung, edited by Theodor Petermann, 185. Dresden: von Zahn und Faensch.

- Simmel, Georg. 1911. “Der Begriff und die Tragödie der Kultur.” In Philosophie der Kultur Gesammelte Essais, 245–77. Leipzig: Werner Klinkhardt.

- Simmel, Georg. 1950. “Metropolis and Mental Life.” In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, edited by Kurt Wolf, 409. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Simmel, Georg. 1950. “The Stranger.” In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, edited by Kurt H. Wolff. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Simmel, Georg. 1968. “On the Concept and the Tragedy of Culture.” In The Conflict in Modern Culture and Other Essays, 30. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Spengler, Oswald. 1976. Man and Technics: A Contribution to a Philosophy of Life (1931), translated by Charles Francis Atkinson. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Spengler, Oswald. 1991. The Decline of the West, translated by Charles Francis Atkinson, 31–32. Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Stierli, Martino. 2010. “Mies Montage.” AA Files 61, 64.

- Tafuri, Manfredo. 1977. “Il teatro come ‘città virtuale.’ Dal Cabaret Voltaire al Totaltheater/The Theatre as a Virtual City: From Appia to the Totaltheater.” Lotus International 17: 30–53.

- van der Rohe, Mies. 1960. “Wohin gehen wir nun?” Bauen und Wohnen 15, no. 11: 391.

- Wachsmann, Konrad. 1952. “Mies van der Rohe, his Work.” Arts and Architecture 69, no. 38: 21.

- Watkin, David. 2001. Morality and Architecture Revisited. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.