Abstract

Global discourse has evidenced that the physical and social environment continues to have a large bearing on how people age, resulting in growing recognition of the socio-spatial needs of older people in urban environments. This article examines the representation of Zimbabwe’s older people, a subject that has rarely been the focus of critical analysis. A sample of national policy documents and media articles were carefully selected and inspected to determine the level of presence of older people’s welfare using discourse analysis. The article shows how the discourses on spaces of welfare for older people in Zimbabwe are layered and multidimensional. This includes challenges of access to spaces of welfare, the abandonment and neglect of older people, as well as the changes to family and community support known as Ubuntu.

Introduction

In African cities, aging is currently occurring against a background of immense economic and social hardships. Not only will urban growth rates over the next several decades outstrip other regions of the Global South, but Africa is the only continent where urban population and economic growth have not been mutually reinforcing, leading to a situation where an impoverished urban populace survives largely under informal conditions.Footnote1 Arguably, the inequality that characterizes the “urban divide,” is the greatest challenge to urban areas in Africa with urban dwellers highly segregated by class and ethnicity. There is a greater appreciation across Africa that aging, urban growth and urbanization can no longer be ignored.Footnote2 Typically, African cities are economically controlled by small political or economic elites, while the vast majority of residents barely meet their basic needs. Spatially, the urban divide in Africa is reflected in the high incidence of slum and informal settlement.Footnote3 Despite the many advantages that urban areas provide, the poorest residents often live in exceptionally unhealthy and dangerous conditions.Footnote4

Changes to urban living in the global South has led to changes with the traditional family support systems for older people. This support has decreased as younger family members living in urban areas may provide financial support but are unlikely to be physically present to provide health care for vulnerable older family members.Footnote5 Cecilia Tacoli explains that the reality of housing in African countries is that the composition of households is frequently more fluid, and members may reside in different locations for varying periods of time through seasonal or temporary migration (the latter often involving periods of several years) although in terms of commitments and obligations (including financial support) they can still be considered members of their household of origin.Footnote6 Linda G. Martin and Kevin Kinsella note that family structure can also serve as a determinant of migration for older people to urban areas.Footnote7 This migration is often the result of, firstly, the need to receive support and care from family and secondly, the need to provide support and care for children and grandchildren. Rural-to-urban migration may also arise when older women migrate to cities to join their children after the deaths of their husbands.Footnote8

This article explores the dominant narratives regarding access to socio-spatial welfare by older persons in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe’s urban space reveals a crisis of the prioritization of aging issues. Across the Zimbabwean urban hierarchy, poverty trajectories have been associated with the development of increasingly informalized urban employment and “illegal” low-income housing solutions. Urban Zimbabweans are progressively forced into informal settlements usually designated as unplanned by the government, municipal or town authorities.Footnote9 Older persons are often particularly vulnerable to the influence of urban characteristics and rely more on community sources meant for integration.Footnote10 What is becoming evident is that the physical and social environment has an increasingly larger bearing on how people age and the quality of life that a person can enjoy in old age.Footnote11 However, the socio-spatial exclusion of older people in Zimbabwe is still an under-researched area. The paucity of evidence in this area may in part be responsible for the way in which policies addressing urban exclusion and inequality has only recently begun to gain traction and has focused on single parents, young people and, principally, labor market participation. This article contributes toward the interrogation of inclusivity in Zimbabwean policies, achieved by examining the socio-spatial environments of welfare for older people in Zimbabwe. It aims to provide an overview of the discourses of spaces of welfare for older people in Zimbabwe. To identify and support the review, a sample of policy and media documents were carefully selected and inspected to review the visibility of older people in Zimbabwe’s policy and media discourse. The analysis included a collection of twenty-three documents produced for national welfare and urban development programs. It builds on research conducted by Busisiwe Chiko Makore and Sura Al-Maiyah which investigated the discourses of older people living in urban environments through mixed-methods including semi-structured interviews with older people and a wider document discourse analysis.Footnote12 In this article, targeted searches were conducted for documents through snowballing, identifying publications in reference lists, and expert recommendations. Furthermore, a media analysis was conducted to add a contemporary lens to the analysis, that is, an online search of Zimbabwe’s print media websites to elicit news stories that have a focus on older persons or obtaining socio-economic and cultural dynamics that intersect with older persons’ lived realities. This was an analysis of news reportage to assess if it was inclusive of welfare domains for older persons in urban areas and this was for the period 2020–2021.

Urban Environment in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is a landlocked southern African country with approximately thirty-three percent of the population recognized to be living in urban areas.Footnote13 The basis for official designation of an urban area in Zimbabwe is by having a compact settlement of 2,500 people or more where the majority of settlers could be employed in non-farm employment.Footnote14 Like most Global South countries, Zimbabwe will witness increased numbers of older people. The most recent national census in 2012 reported that only six percent of Zimbabwe’s population is aged over sixty years old and less than one percent is aged over eighty.Footnote15 These percentages were expected to experience subsequent increases between 2012 and 2050. As in any society, such aggregate figures mask the heterogeneity of the population of older people. This small proportion of older population might suggest that aging is not a phenomenon of priority in Zimbabwe. However, the absolute numbers tell a different story. Projections based on the 2012 national census show that 785,000 persons aged sixty and over living in Zimbabwe in 2012 and by 2050 it is projected that there will be 2,556,000 persons over the age of sixty years.Footnote16 Additionally, contrary to misconceptions, there is considerable longevity within the older population.Footnote17 This growth in numbers of older persons is also increasingly evident in the urban environment.

Zimbabwe’s urban spaces are largely influenced by the political change in the country with the independence war in the 1970s followed by the 1980 independence. The country inherited an economy molded on the philosophy of white supremacy following the 1980 independence and evolved into a relatively well-developed and modern formal sector which co-exists with an underdeveloped and backward rural economy. Prosper Chitambara argues that the formal sector is the enclave part of the economy developed on the basis of the ruthless dispossession of land, the livelihood source of the majority of blacks which forced them into wage employment.Footnote18 However, the country continues to face multiple hazards that include: the lingering structural and floods’ induced food and nutrition insecurity, the ensuing health crises, the on-going impacts of COVID-19 and the chronic economic crisis. Zimbabwe is still in hyperinflation, severely impacting affordability of basic services by most of the population.Footnote19

A History of Unequal Spaces of Care and Welfare for Older People

Zimbabwe’s colonial urban history has created segregated spaces based on race, and post-independence policies or the lack thereof have maintained the status quo, further alienating the urban poor.Footnote20 Against this line of thought, interventions by the leading political party, Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) have further increased the inequality divide. This is evidenced by the May to July 2005 implemented “Operation Murambatsvina” (OM) (murambatsvina meaning “drive out the rubbish” or “restore order”). The OM started in the capital, Harare, and quickly developed into a deliberate nationwide campaign destroying what the Government termed illegal vending sites, structures, other informal business premises and homes. It had major economic, social, political and institutional impact on Zimbabwean society.Footnote21 Older people were one of the main categories of vulnerable victims who lost their homes and livelihoods. The OM set a trend for future urban interventions which further entrenched older persons in informal spaces and spaces of urban poverty and uncertainty. Footnote22

The socio-cultural and political landscape in Zimbabwe has largely relied on romanticized notions that all older people access welfare, care and support from their extended family. However, increasing numbers of older people can no longer rely on previously enduring traditional patterns of care and support for a variety of reasons. Pervasive poverty and the impact of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in Africa has reconfigured the care for older generations and the familial support for younger infected/affected generation, often to the detriment of care for the older people in need.Footnote23 This situation is even more precarious for migrant older people, without strong support networks leading them to homelessness or residence in state-led old age homes.

Enduring Zimbabwean culture and tradition suggests that in a typical household, the older person should have a specific role and position, often in the social upbringing of the young population. Psychologically and socio-culturally, for older persons this can be a very satisfying role and can contribute to their overall state of wellbeing and welfare.Footnote24 This familial and community interactions and support contribute to the welfare of older people and the sense of belonging. However, these exchanges between generations are not always evident in urban spaces in Zimbabwe. There is an absence of spaces in urban areas where older persons can embed their knowledge of indigenous knowledge systems toward contributing to managing social relations and social solidarity. For example, the arts center “Amakhosi” in the city of Bulawayo (second largest city of Zimbabwe) has over the years nurtured talent of youths in different artistic genres, receiving noteworthy investment. Arguably across Zimbabwe, no similar specific arts and cultural heritage centers or community centers exist where older persons can interact with younger generations for example through participation in hometown associations and mutual self-help platforms such as burial societies activities.

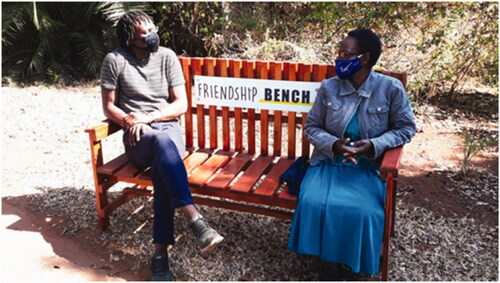

Some recent initiatives that are aiming to challenge the level of exclusion of older people in society do exist although seemingly developed in isolation. An example is The Friendship Bench (see ) which is an initiative which uses a cognitive behavioral therapy-based approach at primary care level in high density locations for the objective of addressing kufungisisa (“thinking too much” in Shona vernacular).Footnote25 The Friendship Bench uses “grandmothers” to deliver the therapy. These grandmothers are community volunteers, without any prior medical or mental health experience, who are trained to counsel patients usually for six structured 45-minute sessions, on wooden benches within the grounds of clinics in a discrete area. It must be noted that historically before the advent of colonialism and subsequent introduction of professions as social work in Zimbabwe, older persons were active in providing counseling and insights to difficult situations. These older persons termed in the Shona language as madzisahwira, sekuru, and tete use knowledge of overcoming adversities as experiential knowledge to provide counseling to younger clan members including marital difficulties, depression, and financial insecurities.

Another example is the “Dzidziso yaAmai” initiative, which was implemented throughout year 2020, led by Zimbabwe’s First Lady, Auxillia Mnangagwa. Media discourses has framed this initiative as an all-inclusive program seeking to promote good morals and fight socio-pathological vice that Zimbabwean youths grapple with. The setup of this initiative is such that older people impart various lifelong skills to youth, equipping them with coping capacities in a dynamic and ever-changing socio-economic fabric.

Older Zimbabweans experience urbanity with existing connectivity with both the post-independent narratives of national development and the collective social memories that has established an interweaving of individual life histories with the prospective and “eternal” return of ancestral knowledge. However, without structured responsibilities and certainties, the places they inhabit become instances of disjointed histories with no official claim to the modernity of urban life.Footnote26 The following sections aim to explore the multi-layered discourses of the welfare of older people.

Accessing Spaces Welfare of Older People in Zimbabwe’s Urban Areas

The discourse analysis of the selected national documents reveals the framing of older Zimbabweans as part of a human rights-based approach which alludes to the idea that older people are valuable members of society and entitled to care and welfare from the state. Key documents such as the Constitution (2013) offer specific paragraphs on the rights of older people. This means that, regardless of the class or social status of older people, they have the same rights as other (younger) persons and should be able and enabled to exercise those rights like anyone else. Zimbabwe identifies and advocates for its citizens as provided in Section 30 of its Constitution.

The State must take all practical measures, within the limits of the resources available to it, to provide social security and social care to those who are in need.Footnote27

The Constitution also contains an inclusive Declaration of Rights (Chapter 4) that underscores the social protection provision. The Declaration of Rights further places prominence on equality of opportunities and nondiscrimination as well as empowerment and employment creation with special focus on older people:

People over the age of seventy years have the right —

to receive reasonable care and assistance from their families and the State;

to receive health care and medical assistance from the State; and

to receive financial support by way of social security and welfare;

and the State must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within the limits of the resources available to it, to achieve the progressive realisation of this right.Footnote28

Disappointingly, there is an inconsistency in the policy definition of older people in accessing these rights to welfare. Section 82 of the Constitution describes an older person as a person who is above the age of seventy years, whilst the Older Persons Act defines an older person as a person over the age of sixty-five years. This inconsistency of definition can adversely impact the access to welfare for older people and their right to welfare.Footnote29 Formal social security support is evidenced in disparate patches of commitment. Some level of social security for older persons is described in the National Social Protection Policy Framework administered by the National Social Security Authority (NSSA).Footnote30 The Older Persons Act sheds some light on the understanding of older people eligible for social welfare.Footnote31 This includes persons that fit four of the following criteria: an older person who (1) is handicapped physically or mentally; or (2) suffers continuous ill-health; or (3) is a dependent of a person who is destitute or indigent or incapable of looking after himself or herself; or (4) otherwise has need of social welfare assistance. Further eligibility for social welfare assistance includes an assessment of the availability of dependents, suitability for resettlement or rehabilitation, and the state of health, educational level and the level of skills of the applicant for purposes of employment. However, meeting the criteria will not guarantee access to formal support as explained in the excerpt below from the Zimbabwe National Healthy Aging Strategic Plan.

Complicating the access to social services were unavailability of medicines in health facilities and low access to income for basic daily living such as inability to pay for transport costs to health facilities, payment and low access to income for basic daily living such as inability to pay for transport costs to health facilities, payment for health services at higher level facilities due to severe socio-economic challenges affecting Zimbabwe.Footnote32

Media discourse suggests that the NSSA is considering paying pensioners in both local and foreign currency to cushion them from the spiraling cost of living during the year 2021. This is a commendable move, as current obtaining socio-economic dynamics have pauperized older persons who rely on their pensions, however, recent implementation of reforms saw the contribution rate increased from seven percent to nine percent split equally between employer and employee, as well as the increase in the maximum pensionable salary from ZW$700 (US$8,64) to ZW$5,000 (US$61,73).Footnote33 The newspaper Zimbabwe Situation describes how Bulawayo City Council (BCC) pensioners have demanded that the local authority awards them with rebates on rates and water through reduced medical aid subscription and pensioners funeral assistance in cash or kind. An assertion of right is shown in the media article, with pensioners expressing awareness that BCC had a policy on rates rebated for ratepayers who are above seventy years.Footnote34

Accessing welfare for older people in Zimbabwe reflects a complicated landscape. The prevailing socioeconomic challenges have affected the quality and quantum of support to older persons. Although the documents evidence a clear willingness from the Government to support the development of inclusive policies and emphasize the rights for older people, there are acute challenges to the realization of the political visionary rhetoric on supporting older people.

Informal, Neglected and Abandoned Spaces

Our analysis shows that the image of the sekuru (older man) or gogo (older woman) is still absent from discourse on the urban environment, situating older Zimbabweans in a background of rurality and communal agriculture/farming. The very idea that such persons could be found in the urban hustling and bustling of life, in the overcrowded “concrete jungle” was and is still very much unheard of. Their very presence in urbanity is questioned. The dominant view is that Zimbabwe is and continues to be a “young” nation, while older persons are seen as visitors to the city with a belonging only in the rural areas. The Government of Zimbabwe’s policies never anticipated a situation where older persons would be a constituency in urban settings needing Government housing and care. Arguably, older persons’ dominance within the profile of the urban poor suggests they have invariably become citizens “left behind” in daily life processes encompassing tedious routine of incessant improvization to make ends meet in contexts offering little formal employment, political stability, or reciprocity. This is articulated by Jeremy L. Jones, who framed Zimbabwe’s economy as that of kukiya kiya which is a term understood as an “informal” way of life.Footnote35 This term of informality argues that from its former marginalization in Zimbabwean life and consciousness, kukiya-kiya now dominates everyday existence ostensibly as the only way of organizing and justifying economic action mazuva ano (“these days”). Although informality is rarely mentioned in the discourse analysis, it is implied through the lack of formal spaces for older people. Older people living in informality experience the lack of security of tenure in law and practice, making protection against forced eviction very difficult and leaving the most vulnerable older persons at risk. With no alternative option, the life of older residents and other residents has consisted of routinized exploitation in the form of insecure tenure, evictions or threats of evictions, and generalized extortion for access to any basic services or economic opportunity of settlement.Footnote36 Older women find themselves in a heightened place of vulnerability due to cumulative effects of multiple discriminations and informal customary mechanisms that remain the most important mechanisms for land tenure, regardless of formal law.Footnote37

In 2005 when the OM was rolled out, citizens who had been tenants in backyard cabins seeing out their different livelihoods now suddenly found themselves homeless. This included migrants (known by the term Mabwidi) who had permanently settled especially during the then Rhodesian Federations. As noted by the excerpt from the report of the Fact-Finding Mission to Zimbabwe to Assess the Scope and Impact of Operation Murambatsvina, vulnerable people impacted by the operation were encouraged to return to the rural areas:

While households are being encouraged to “return” to the rural areas, many widows, divorcees and those married to men of foreign origin do not have a rural home to go to.Footnote38

Evidence from people who experienced the OM suggests that in appealing for humanitarian assistance in the form of some housing, relatives of mabwidi received responses from frontline operatives of the OM suggesting that they check on their ID cards to trace back to their rural roots for accommodation. Again, in disparaging remarks in responding to the OM, then President Robert Mugabe labeled some victims with no rural residences to fall back on for accommodation as totemless. Zimbabwean culture is grounded on a totem system which helps an individual identify with a particular clan based on their totem which offers an emblem and distinct regional identity. The report of the Fact-Finding Mission to Zimbabwe to Assess the Scope and Impact of Operation Murambatsvina made recommendations that the Government of Zimbabwe should grant full citizenship to those former migrant workers and their descendants who have no such legal status. A recommendation that has yet to take full effect today, over fifteen years later.

A report on findings by the Parliamentary Committee on Labor and Social Welfare was produced in 2018. Findings of the report established multiple challenges encountered toward older persons’ care included poverty, informality, financial constraints, gaps in health care access and poor infrastructure. From findings of this parliamentary committee report, it was noted that the majority of residents at old people’s homes originated from neighboring countries, such as Malawi, Zambia and Mozambique, therefore they lacked availability of an extended family capable of providing holistic care to them. These Mabwidi persons were known to have provided labor during the then Northern and Southern Rhodesian Federation between 1957 and 1965. Given their contested citizenship status they are excluded from benefiting from the framework for care of older persons. In addition, the report established that rejection by relatives and childlessness were commonly raised as reasons why individuals ended up staying in old age homes. The National Healthy Aging Strategy supports this trend, noting that older persons without formal identification continue to experience challenges accessing social security services including placement into homes resulting in increased risk of destitution. Homelessness and displacement are experienced largely by older people living in urban poverty, often those who were never employed or employed without any pension contributions, such as smallholder farmers, or farm workers. This situation leads older people without financial stability and familial support to find respite in old age homes or in places of informality. The government of Zimbabwe supported old age homes, they are generally in a dire state, needing urgent intervention. The intractable socio-political and economic environment has left the welfare of older people living in homes subject to donations from the public and non-governmental organizations and charities. This is a prevalent theme in media articles as evidenced by an article by journalist Nyasha Chingono published in The Guardian.Footnote39 Old age homes such as the Society of the Destitute Aged (SODA) home experienced massive attention in the immediate years post-independence and the late Diana, Princess of Wales officiated at SODA’s opening, but currently, lack of funding affects the running of the facility (see ). Prominent persons and schools have donated to old peoples’ homes in their regions at critical moments in the year, demonstrating the inconsistency in supporting older people living in these spaces. As Chingono states:

Figure 2 Society of the Destitute Aged (SODA) Home for Older People in Highfield, a Township in South-West Harare. Photo: Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi/AP.

Older people have become silent victims of the pandemic. Zimbabwean communities used to pride themselves on looking after their ageing members, but poverty and high mortality rates among working-age men and women as well as unrelenting economic pressures on families have left older people isolated, poor and lonely. While some have ended up sleeping rough, risking infection and starvation, the lucky ones […] are cared for in homes such as the SODA home.Footnote40

In sharp contrast to the sections above, many of the higher priced retirement homes and old-age care facilities offer twenty-four-hour support and health care while others provide moral support, a social space, and elderly-specific assistance. Residents must be fifty years or older, and are often perceived to be wealthy, white Zimbabweans, although some private retirement villages do host black Zimbabweans who can afford the costs. An example of this is the Dandaro Retirement Village situated in the city of Harare in the low-density suburb of Borrowdale (see ). Completed in the year 2000 Dandaro (a Shona word meaning a gathering or meeting place) is the first retirement village of its kind in Zimbabwe. It offers a package inclusive of amenities contributing to enhanced social functioning of older persons. Self-catering homes have been noted to be fully equipped with a kitchen and dining area, furnished lounge, furnished patio/veranda and garden space for outdoor living, borehole water, solar backup, gas cooking option, washer and dryer, shared swimming pool and tennis court. The result is a highly serviced, high quality residential retirement village, quite unlike the old age homes discussed previously.

What appears to be evident from the discourse discussed in this section is a layering of experience of the urban poor within a dynamic and constantly changing context. Informal settlements and dilapidated and left behind old age homes have become a seemingly permanent home for most low-income communities including older persons. Adequate spaces of welfare with access to healthcare and social and community care remain private and exclusive only for those with the financial means.

Shared Spaces of Ubuntu and Community

The home is continuously described by many academics as the setting for older peoples’ primary care. Irrespective of the nature of the welfare regimes they are embedded in, families are central to the debate about how societies will face the challenges of population aging. However, gleaning multiple national policies reports amplify that this safety net is failing, resulting in many older persons being indigent and experiencing deprivation. The excerpts from the following documents alluded to the precarious nature of state support and the family unit in caring for older people:

Traditionally, the extended family system was responsible for social support and care provision to its members. However, urbanization, industrialization and globalization processes have gradually weakened the cohesiveness of the extended family system, thereby undermining its capacity to provide social support and care to its members. This void is increasingly being filled by the state and non-state actors but they are constrained by lack of adequate resources to provide meaningful social support and care.Footnote41

The Situation Analysis findings, conducted as part of the strategy development process, established a weakened community and family-based care system in Zimbabwe, despite these being the most effective means of managing long term care of older persons.Footnote42

The SWOT analysis of the mental health services system reveal weaknesses including a lack of financial resources, stigma, poor interdepartmental, multidisciplinary and intersectoral communication and collaboration and poor implementation of policies and plans.Footnote43

Changing family structures within the Zimbabwean context in the face of poverty and pandemics is therefore essentially about the ability of family networks to sustain intergenerational support.Footnote44 There is an emphasis on families as the key resource for their members especially in times of hardship or entrenched poverty. On the same note mutual intergenerational support is seen as the “African way” as opposed to the so-called Western ways, and a moral asset upon which the African care model can be embedded on. This type of support is commonly known as Ubuntu, an African word for a universal philosophy entailing community identity, humanity, humanness, and the use of consensus in conflicts resolution.Footnote45 As a philosophy, Ubuntu does not fit into the Global North model of formalized knowledge but is contingent and flexible. The Government of Zimbabwe officially recognizes the concept and acknowledges its impending collapse. Failures of healthcare infrastructure to accommodate older people has resulted in unrelenting pressures within the family unit. One of the pressures is financial especially when the private health care route is pursued in diagnosis and clinical management of a given chronic or terminal health condition. The Zimbabwe National Healthy Aging Strategic Plan 2017–2020 contextualizes the above assertion:

Deteriorating socio-economic conditions have collapsed the “Ubuntu” spirit that spurred care of the less privileged in the community including older persons.Footnote46

Ethnographic studies by sociologists in Zimbabwe over the years establishes that old age was associated with witchcraft especially if the older persons had wrinkles.Footnote47 Signs of dementia might cause people to label some older persons as witches and sources of family misfortunes. Those that were victimized and neglected were mostly females. These allegations undermine the safety net that cushions older persons through care by the extended family and community at large in the spirit of Ubuntu founded on mutuality. The structural changes to families may threaten their caring capacity and researchers and policy makers have expressed rising apprehension due to this.Footnote48 Media discourses indicate that parents’ entitlement to filial support in old age is no longer unconditional but based on the principle of reciprocity which is contingent upon the degree to which they fulfilled their earlier parental duties to the children. With this perspective, it is the children themselves who judge the conduct of their parents and even if children feel that an aged parent “deserves” support, this will not be forthcoming if resources are scarce, since the needs of the young have a “fundamental priority” over those of the older person. The Zimbabwean policies and legislation analyzed in this section often do not account for the fact that, in all societies, older people both want to and do contribute economically and socially well into old age. The valuable contributions of older persons are rarely mentioned in any of the documents, systematically undervaluing the contributions, and, as a result, perceptions of later life are tinted by the presumption that older people are largely dependent on their households, communities, or the state.

Conclusion

The analysis in this article brings to the forefront the discourses surrounding older people revealing that they are still encumbered by spaces that remain resistant to transformation. State failures to recognize and safeguard older people has led to a deep mistrust of the Government welfare infrastructure and has subsequently transformed the traditional structure of the family space. The changing culture of care experienced through post-colonial governance, positions old age at an uncertain place particularly with existing discourses and frameworks that underline the “traditional” family as a source of belonging, safety and care for older men and women. With no specific spaces for older people – or those that do exist, exist in exclusive enclaves – the majority of older Zimbabweans may never truly experience a sense of belonging within urban spaces. Deep inequalities exist between formal and informal spaces of welfare. Furthermore, the focus on access to welfare as a matter of chronology leads to homogenous assumptions about older people living lives of restricted functionality and activity to access welfare. Crucially, older people who endure a lifetime of poverty, malnutrition, and heavy labor may be chronologically young but “functionally” old at ages such as fifty. By considering the context of a person and their life course, strategies, and resources used for coping with aging by individuals and communities can be established at a much earlier point in life. Lobbying and advocacy by diverse state and non-state actors such as social workers and urban community-based stakeholders, in addition to the meaningful involvement of older persons, can enable the visibility of aging in urban and social development and inform how best to deliver inclusive and sustainable spaces of welfare for older people.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chiko Makore Ncube

Dr Chiko Ncube is an urban planner and architect with expertise in inclusive planning and architecture. She is a research fellow working on multiple international and interdisciplinary funded projects on inclusive planning, age-friendly urban environments, refugee camp planning, architectural heritage conservation and digital technologies. Her research projects span multiple countries including Zimbabwe, Jordan, India, Italy and the United Kingdom. She completed her PhD in Inclusive urban planning from the School of the Built Environment, University of Salford in 2018.

Tatenda Goodman Nhapi

Tatenda Goodman Nhapi is an independent researcher affiliated to Erasmus Mundus MA Advanced Development in Social Work – a joint Programme between the University of Lincoln (England); Aalborg University (Denmark); Technical University of Lisbon (Portugal); University of Paris Ouest Nantere La Defense (France); Warsaw University (Poland). He is also a Research Associate with Department of Social Work, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

Notes

1. Edward Paice, Habitat III: A Critical Opportunity for Africa (London: Africa Research Institute: 2016). https://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/newsite/blog/habitat-iii-critical-opportunity-africa/ (accessed September 2021); James Duminy, Jørgen Andreasen, Fred Lerise, and Vanessa Watson, Planning and the Case Study Method in Africa: The Planner in Dirty Shoes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

2. Paice, Habitat III.

3. UN-Habitat, The State of African Cities: Re-imagining Sustainable Urban Transitions (Nairobi: UN-Habitat, 2014).

4. United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and HelpAge International, Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and a Challenge (New York: UNFPA; London: HelpAge International, 2012).

5. Nana Araba Apt, “Aging in Africa: Past Experiences and Strategic Directions,” Ageing International 37 (2011): 93–103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12126-011-9138-8.

6. Cecilia Tacoli, “Urbanization, Gender and Urban Poverty: Paid Work and Unpaid Carework in the City,” Urbanization and Emerging Population Issues Working Paper 7 (London: IIED; New York: UNFPA, 2012), http://www.unfpa.org/resources/urbanization-gender-and-urban-poverty

7. Linda G. Martin and Kevin Kinsella, Research on the Demography of Aging in Developing Countries (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1994).

8. Ibid.

9. Deborah Potts, “‘Restoring Order’? Operation Murambatsvina and the Urban Crisis in Zimbabwe.” Journal of Southern African Studies 32, no. 2 (2006): 273–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25065092.

10. Tine Buffel, Chris Phillipson, and Thomas Scharf, “Ageing in Urban Environments: Developing ‘Age-Friendly’ Cities,” Sage Journal: Critical Social Policy 32, no. 4 (2012): 597–617.

11. Powell Lawton and Lucille Nahemow, Ecology and the Aging Process (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1973), 619–74; Diego Sanchez-Gonzalez and Vicente Rodríguez-Rodríguez, “Introduction to Environmental Gerontology in Latin America and Europe,” in Environmental Gerontology in Europe and Latin America Policies and Perspectives on Environment and Aging, ed. Sanchez-Gonzalez and Rodríguez-Rodríguez (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016), 1–7.

12. Busisiwe Chikomborero Ncube Makore and Sura Al-Maiyah, “Moving from the Margins: Towards an Inclusive Urban Representation of Older People in Zimbabwe’s Policy Discourse,” Societies 11, no. 1 (2021): 7. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4698/11/1/7.

13. The Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT), Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe Population Census (Harare: ZIMSTAT, 2012).

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. UNFPA and HelpAge International, Ageing in the Twenty-First Century.

17. HelpAge International, Global AgeWatch Index 2015: Insight Report (London: HelpAge International, 2015).

18. Prosper Chitambara, Social Protection in Zimbabwe (Harare: Labour and Economic Development Research Institute of Zimbabwe, 2010).

19. UNICEF, Zimbabwe: Multihazard Situation Report # 1: January–March 2020 (2020).

20. Beth Chitekwe-Biti, “Struggles for Urban Land by the Zimbabwe Homeless People's Federation,” Environment & Urbanization 21, no. 2 (2009): 347–66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956247809343764.

21. Anne Kajumulo Tibaijuka, Report of the Fact-Finding Mission to Zimbabwe to Assess the Scope and Impact of Operation Murambatsvina. UN Special Envoy on Human Settlements Issues in Zimbabwe (Nairobi: UN Human Settlements Program, 2005).

22. Armando Barrientos, Mark Gorman, and Amanda Heslop, “Old Age Poverty in Developing Countries: Contributions and Dependence in Later Life.” World Development 31, no. 3 (2003): 555–70.

23. Jaco Hoffman, “Families, Older Persons and Care in Contexts of Poverty: The Case of South Africa,” in International Handbook on Ageing and Public Policy, ed. Sarah Harper, Kate Hamblin, Jaco Hoffman, Kenneth Howse, and George Leeson (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015): 256–270.

24. M. J. S. Masango, “African Spirituality That Shapes the Concept of Ubuntu,” Verbum Et Ecclesia 3 (2006): 930–943.

25. Friendship Bench is registered in Zimbabwe as a Private Voluntary Organisation (PVO). Further information can be accessed https://www.friendshipbenchzimbabwe.org/

26. Makore and Al-Maiyah, “Moving from the Margins,” 7.

27. Republic of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe’s Constitution of 2013, Chapter 2, Section 30.

28. Ibid., Chapter 4, Section 82.

29. Makore and Al-Maiyah, “Moving from the Margins,” 7.

30. Government of Zimbabwe, National Social Protection Policy Framework for Zimbabwe (Harare: Government of Zimbabwe, 2016).

31. Government of Zimbabwe, Older Persons Act No. 1 (Harare: Government of Zimbabwe, 2012).

32. Government of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe National Healthy Ageing Strategic Plan 2017–2020 (Harare: Government of Zimbabwe, 2017).

33. Kudzai Kuwaza, “NSSA Mulls Forex Pay Outs,” Zimbabwe Independent, October 30, 2020, Business Digest.

34. Vusumuzi Dube, “BCC Pensioners Demand Rates Rebate,” Zimbabwe Situation, August 15, 2021, https://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/bcc-pensioners-demand-rates-rebate/

35. Jeremy L. Jones, “‘Nothing Is Straight in Zimbabwe’: The Rise of the Kukiya-Kiya Economy 2000–2008,” Journal of Southern African Studies 36, no. 2 (2010): 285–99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2010.485784.

36. Dialogue on Shelter and Zimbabwe Homeless Peoples Federation, Harare Slum Upgrading Profile Report (Harare: Dialogue on Shelter and Zimbabwe Homeless Peoples Federation, 2014).

37. HelpAge International, Gender and Ageing Briefs (London: HelpAge International, 2002).

38. Tibaijuka, Report of the Fact-Finding Mission to Zimbabwe.

39. Nyasha Chingono, “Zimbabwe’s Older People: The Pandemic’s Silent Victims,” The Guardian, October 22, 2021, Global Development, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/oct/22/zimbabwes-older-people-pandemic-silent-victims.

40. Ibid.

41. Government of Zimbabwe, National Social Protection Policy Framework for Zimbabwe.

42. Government of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe National Healthy Ageing Strategic Plan 2017–2020.

43. Government of Zimbabwe, National Strategic Plan for Mental Health Services 2019–2023 (Harare: Government of Zimbabwe, 2019).

44. Hoffman, “Families, Older Persons and Care.”

45. Mugendi K. M’Rithaa, Universal Design in Majority Worlds Contexts: Sport Mega-Events as Catalysts for Social Change (Saarbrucken: LAP LAMBERT, 2011).

46. Government of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe National Healthy Ageing Strategic Plan 2017–2020, 14.

47. Gordon L. Chavunduka, “Realities of Witchcraft,” Zambezia 13, no. 2 (1980): 130–35.

48. Hoffman, “Families, Older Persons and Care.”

References

- Apt, Nana Araba. 2012. “Aging in Africa: Past Experiences and Strategic Directions.” Ageing International 37: 93–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-011-9138-8

- Barrientos, Armando, Mark Gorman, and Amanda Heslop. 2003. “Old Age Poverty in Developing Countries: Contributions and Dependence in Later Life.” World Development 31, no. 3: 555–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00211-5

- Buffel, Tine, Chris Phillipson, and Thomas Scharf. 2012. “Ageing in Urban Environments: Developing ‘Age-Friendly’ Cities.” Sage Journal: Critical Social Policy 32(4): 597–617.

- Chavunduka, Gordon. 1980. “Realities of Witchcraft.” Zambezia 13: 89–109.

- Chingono, Nyasha. 2021. “Zimbabwe’s Older People: The Pandemic’s Silent Victims.” The Guardian, October 22, Global Development. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/oct/22/zimbabwes-older-people-pandemic-silent-victims.

- Chitambara, Prosper. 2010. Social Protection in Zimbabwe. Harare: Labour and Economic Development Research Institute of Zimbabwe.

- Chitekwe-Biti, Beth. 2009. “Struggles for Urban Land by the Zimbabwe Homeless People’s Federation.” Environment & Urbanization 21, no. 2: 347–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247809343764

- Dialogue on Shelter and Zimbabwe Homeless Peoples Federation. 2014. Harare Slum Upgrading Profile Report. Harare: Dialogue on Shelter and Zimbabwe Homeless Peoples Federation.

- Dube, Vusumuzi. 2021. “BCC Pensioners Demand Rates Rebate.” Zimbabwe Situation, August 15, https://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/bcc-pensioners-demand-rates-rebate/

- Duminy, James, Jørgen Andreasen, Fred Lerise, and Vanessa Watson. 2014. Planning and the Case Study Method in Africa: The Planner in Dirty Shoes. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Government of Zimbabwe. 2012. Older Persons Act No. 1. Harare: Government of Zimbabwe.

- Government of Zimbabwe. 2016. National Social Protection Policy Framework for Zimbabwe. Harare: Government of Zimbabwe.

- Government of Zimbabwe. 2017. Zimbabwe National Healthy Ageing Strategic Plan 2017–2020. Harare: Government of Zimbabwe.

- Government of Zimbabwe. 2019. National Strategic Plan for Mental Health Services 2019–2023. Harare: Government of Zimbabwe.

- HelpAge International. 2002. Gender and Ageing Briefs. London: HelpAge International.

- HelpAge International. 2015. Global AgeWatch Index 2015 Insight Report. London: HelpAge International.

- Hoffman, Jaco. 2015. “Families, Older Persons and Care in Contexts of Poverty: The Case of South Africa.” In International Handbook on Ageing and Public Policy, edited by Sarah Harper, Kate Hamblin, Jaco Hoffman, Kenneth Howse, and George Leeson, 256–270. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Jones, Jeremy. 2010. “‘Nothing Is Straight in Zimbabwe’: The Rise of the Kukiya-kiya Economy 2000–2008.” Journal of Southern African Studies 36, no. 2: 285–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2010.485784

- Kuwaza, Kudzai. 2020. “NSSA Mulls Forex Pay Outs.” Zimbabwe Independent, October 30, Business Digest.

- Lawton, Powell and Lucille Nahemow. 1973. Ecology and the Aging Process. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- M’Rithaa, Mugendi K. 2011. Universal Design in Majority World Contexts: Sport Mega-Events as Catalysts for Social Change. Saarbrucken: LAP LAMBERT.

- Makore, Busisiwe Chikomborero Ncube, and Sura Al-Maiyah. 2021. “Moving from the Margins: Towards an Inclusive Urban Representation of Older People in Zimbabwe’s Policy Discourse.” Societies 11, no. 1: 7. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4698/11/1/7. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11010007

- Martin, Linda G. and Kevin Kinsella. 1994. Research on the Demography of Aging in Developing Countries. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Masango, M.J. S. 2006. “African Spirituality That Shapes the Concept of Ubuntu.” Verbum Et Ecclesia 3: 930–943.

- Paice, Edward. 2016. Habitat III: A Critical Opportunity for Africa. London: Africa Research Institute. Accessed September 2021. https://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/newsite/blog/habitat-iii-critical-opportunity-africa/.

- Potts, Deborah. 2006. “Restoring Order'? Operation Murambatsvina and the Urban Crisis in Zimbabwe.” Journal of Southern African Studies 32, no. 2: 273–291. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25065092. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070600656200

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, Diego, and Vicente Rodríguez-Rodríguez. 2016. “Introduction to Environmental Gerontology in Latin America and Europe.” In Environmental Gerontology in Europe and Latin America Policies and Perspectives on Environment and Aging, edited by Diego Sanchez-Gonzalez and Vicente Rodríguez-Rodríguez, 1–7. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- The Republic of Zimbabwe. 2016. Zimbabwe’s Constitution of 2013.

- Tacoli, Cecilia. 2012. “Urbanization, Gender and Urban Poverty: Paid Work and Unpaid Carework in the City.” In Urbanization and Emerging Population Issues Working Paper 7. London: IIED; New York: UNFPA. http://www.unfpa.org/resources/urbanization-gender-and-urban-poverty

- Tibaijuka, Anna Kajumulo. 2005. Report of the Fact-Finding Mission to Zimbabwe to assess the Scope and Impact of Operation Murambatsvina. Nairobi: UN Human Settlements Program.

- UN-Habitat. 2014. The State of African Cities: Re-imagining Sustainable Urban Transitions. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

- UNICEF. 2020. Zimbabwe: Multihazard Situation Report #1: January–March 2020.

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and HelpAge International. 2012. Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and a Challenge. New York: UNFPA; London: HelpAge Internatonal.

- The Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). 2012. Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe Population Census. Harare: ZIMSTAT.