Abstract

This article analyzes the formation of a conceptual persona in a narrative which some architects use in the design process. It focuses on a description of such a persona borrowed from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s What is Philosophy? It presents the work of three architects who explore how this persona can express a corporeal, public and emotional presence; elaborating on relations which extend beyond the design task and engage with their cultural context. The task all three were given is to design a glory hole that links divided lovers. The actuality of this configuration asks the inhabitants to imagine the presence of the other much like the architects would in the design process. The research is novel allowing architects to truly indulge in exploring the presence of sexual desire and longing in public space.

Introduction: The Conceptual Persona as a Reflective Tool

Designing architecture requires an imaginative faculty that realizes a hypothetical, yet-to-occur event in space. Before placing the metaphorical pen to paper, these events only exist in the architect’s imagination and often emerge using a design method of narrating an event which involves a conceptual persona that inhabits the space and gives it character. If the program brief asks for an architectural solution for which the architect does not have previous experience, the persona takes a creative form that enables engagement with the contemporary cultural situation in which the designer finds themselves.

The conceptual persona was theorized by Gilles Deleuze and Félix GuattariFootnote1 who use the construct to play the same function as Cogito for Rene Descartes or Dasein for Martin Heidegger. In architecture this imaginary inhabitation can only resemble the actual scenarios of events. However, in the acting out of relations between spaces in the built environment a measure of conceptualization remains. The most palpable scenario is a situation where a viewer can only engage with the inhabitant in a different room through the signs of their presence. The example studied here is the relation between lovers divided by a wall – longing for one-another but separated by a physical barrier – left only to imagine one another’s presence through subtle or not-so-subtle hints.

This article investigates the formation of the conceptual persona in the designs of three anonymous architects who were tasked with designing a space of separation and linking in a desirous relation – specifically that between the users of a glory hole. The glory hole allows bodies to come in close contact with the architectural form that fosters a particular type of erotic arousal between conceptual characters. In this way, the architects engage in a similar game that is played out between the lovers – one of imagining who or what is happening in the a not visible space. The glory hole design project presents the architects with a task they had never before been asked to undertake and gives them an opportunity to expand on a new and creative way of thinking about the relation between intimacy and public behavior. In doing so, the article aims to show how architects engage with the cultural specificities associated with designing intimate and public spaces exacerbated in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, during the 2020 lockdown. Not normally discussed in existing architectural literature, David Holmes, Patrick O’Byrne, Stuart MurrayFootnote2 and Don BapstFootnote3 address the issue of glory holes in public life while Johan AndersonFootnote4 discusses the problematics of queer space from a geographical perspective. This paper makes an original contribution to the disciplines of architecture, gender studies, queer theory and philosophical scholarship.

The article is original in that it employs architectural design methods of drawing showcased through the designs by professional architectural designers who have chosen the aliases: Mary, Adam and Patrick. The architects were asked to produce drawings for a glory hole and its adjoining spaces, following the Health Department of New York city safe sex announcement during the pandemic lockdown.Footnote5 In doing so, the architects show through the conceptual persona, their engagement with the constraints of rules of commerce and fixation on ulterior bodily functions, challenging social, economic and political conceptualisations of corporeal, sexual pleasure. The different styles of drawing of the figure presented by the architects not only reflect on the cultural context but the emotional baggage that the three architects carry. This baggage speaks to how the architects construct and position their practice in the ethical nexus they operate in. In presenting this work, the article shows the fragmented interior machinations of the design process related to architectural detailing associated with bodies that come together in a specific context and under very particular cultural conditions.

This article is inspired by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s postmodern writing in What is Philosophy? in which they define the conceptual persona as a thought experiment that engages with an idea of an interaction with another, imaginary person. This paper expands first, on the conceptual persona in relation to prior architectural designs by Le Corbusier and Peter Salter. Secondly, it outlines the definition and spatial characteristics of the glory hole defined by Holmes, O’Byrne, Murray and Baptst. Thirdly, it discusses the designs that Mary, Adam and Patrick produced showcasing how each took the opportunity to express their view on matters of sexual desire and longing for the intimate in a public space.

Deleuze and Guattari’s Conceptual Persona

According to Deleuze and Guattari, the conceptual persona is an imaginary and naïve construct that is often used by thinkers to examine and test difficult concepts. They consider its formation a “form of becoming the other”Footnote6 and suggest that it offers an opportunity for the thinker to retain a fresh outlook on a specific issue discarding unnecessary metanarratives operating in the immanence of a situation. The Deleuzian-Guattarian persona conforms to a set of characteristics or functions that can be ascribed to a subject under a particular set of conditions, cultural context and for a limited time. They are indispensable in the formation of new ideas in philosophy; the detail of which is dependent on the complexity of the question and the thinker who envisages it/them. Examples conjured by Deleuze and Guattari include a multiplicitous forms of mother undergoing motherly duties or obligations. They write:

Only Justice is just, only Courage courageous, such are Ideas, and there is an Idea of mother if there is a mother who is not something other than a mother (who would not have been a daughter), or of hair which is not something other than hair (not silicon as well). Things on the contrary, are understood as always being something other than what they are. At best, therefore, they only possess quality in a secondary way, they can only lay claim to quality, and only to the degree that they participate in the idea.Footnote7

The figure of ‘mother’ is apt because in real life a mother is much more complicated to define because they are an agent functioning only in the semantic neighborhood of motherhood. At times a mother can take on the traits of a career woman, be an artist, scientist, philosopher, wife, or daughter; and indeed, these may be her most prominently definable traits. The notion of otherness outlined above may serve to indicate the redacted representation of the figure – functioning only for the duration of an event and ascribing to a given relation with a narrow assemblage of characteristics fitting a particular context as they “participate in the idea”.Footnote8

To extrapolate this construct, Deleuze and Guattari refer to the writings of French philosopher, René Descartes for whom the conceptual persona, understood as Cognito, asked: “How do I know that I exist?”Footnote9 This simple question allowed Descartes to develop and present an elaborate answer that now figures as a foundation stone of philosophy. Following from this, German philosopher, Immanuel Kant criticized Cartesian thinking and suggests that the problematics of ontology cannot be fully answered by Cogito because the conceptual persona can not ‘fill’ the complexity posed by the question.Footnote10 Deleuze and Guattari recognize the differences in the understanding of ontology and epistemology as presented by Descartes and Kant and highlight the problem individual thinkers strike in sharing and composing their ideas. In this light, the Deleuzian-Guattarian ‘mother’ may play the function of the mother, artist, philosopher, or daughter but in a different circumstance, it may also be acceptable for her to be the lover to an extra-marital suiter – a role which may give the wholesome image of the mother an additional or different characteristic.

In architecture, the representation of the conceptual persona as a drawing of an inhabitant of a building that possesses certain characteristics is only appropriate for the space it was drawn in, much like the Cogito was for the Cartesian school of thought. In this respect, it is a redacted image of the complexities of events that are yet to happen in the space and it can be criticized from a Kantian perspective. It need not even be drawn, perhaps just imagined, but the conceptual persona allows the designer to adapt the geometries of the plan and section to the needs of this conceptual figure. If the representation of the persona’s dimensions depicts those of the human body accurately, it will show the relation between architectural elements and the heights at which the joints on the body are placed. By doing so, it will make explicit if for instance, windowsills are too high or too low or if stairs are too narrow or wide, etc. Conversely, the personae can also represent more and engage with complex socio-political relations. An actual person in any given room does not need to only limit themselves to one task imagined by the architect. In spite of the fact that the persona cannot represent all the functions that a potential room can offer (or it cannot ‘fill the space’ conceptually) it has the capacity to give form to the designed architecture and become a setting for life to ‘fill in’.

Representations of the generic figure can be found in sketches and drawings by renowned architects. Famous examples of the appropriation of the conceptual persona in architectural drawing include the Vitruvian man drawn by Leonardo da Vinci (associated with notes on Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius) or the ‘modulor man’ famously proposed by Le Corbusier. Lydia Kallipoliti suggests that both personae embody the spirit of the times in which they were produced; the Vitruvian man reflecting the ideals of geometrical supremacy, while the ‘modulor man’ represents the idealized proportions of modern architecture.Footnote11 Alain Pottage analyzes Le Corbusier’s drawings and suggests that by drawing the ‘modulor man’ Le Corbusier aims to represent the complexities and processes of urban living.Footnote12 Le Corbusier’s ‘modulor man’ drawn in a section through the niche of Notre-Dame du Haut, Ronchamp (1950–1954) represents a desire to look – curiously investigating a particular element (the sculpture of the virgin Mary) – indicating the significance of the relations in space. In Le Corbusier’s Notre-Dame niche section, the drawing serves to represent the attitude that the architect had toward the role of Mary, the mother of God, in religion.

Another and more palpable example are Peter Salter’s moody, playful, and full-of-life drawn characters that channel more than just body dimensions. Salter’s conceptual persona can be understood as a representation of the his ambitions, radical attitudes, and rational or emotional sentiments to spatial configurations or experimental form-finding. There is a recurring sense of deliberate definition of inhabitation in every architectural project and a lingering, disputedly implicit, presence of a conceptual persona.

At the same time, it can also be assumed that the more the architectural form is repeated the greater its chances of signifying an archetype and the easier it is to scrutinize its presence or absence in a design without the necessity to imagine the persona. Subsequently, architects can produce work and still offer architecture that has been tested numerous times before, having gained validation through repetition. In this way, architecture can embody the weight of the status quo. The danger here is that architects may find themselves locked in to looking at archetypal typologies of behavior in their attempt to understand what brings their clients and users a sensation of delight in how they go about their day-to-day lives.Footnote13 The specification of an inhabitant is likely to discriminate against opportunities to engage with the immanence of culture and may end up privileging a specific type of conduct above any other. This can be problematic; especially if the architects are taught to think in a particular way and with preferential or biased treatment, take for instance the glory hole.

Close Inspection of the Glory Hole

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 disallowed the continuation of ‘normal’ architectural practice. For one, social gathering and close personal contact became a potentially hazardous and life-threatening endeavor. The status quo that architects had formerly pre-pandemic had to be realigned, at least for the its duration. Governmental and local authorities were challenged with the problems of restricting the citizen’s personal life for public well-being. In an effort to orchestrate civic conduct that may prevent contagion, advice and directives were issued; these touched on most aspects of people’s lives although some behaviors which were less common required specific addressing. One intervention was the need for architectures to allow publicly inappropriate sexual activity, as was the case in the USA.

In 2020, New York officials published a safe sex announcement in which they suggest to “[m]ake it a little kinky. Be creative with sexual positions and physical barriers, like walls, that allow sexual contact while preventing close face-to-face contact.”Footnote14 A device that most comprehensively complies with this remit is the glory hole – a perceived solution to the public health issue that is carried by sexual encounters with a partner without exposing oneself to aerosol carried by breath which may contain the virus. The architectural link between spaces that the glory hole allows is a complex assemblage of relationships in public space.

The glory hole became more pronounced following the AIDS pandemic (in the gay scene, where it is most commonly features) and the related stigmatization of gay sex acts; after which queer culture turned to present sanitized image of hygiene and esthetics of some gay venues.Footnote15 Holmes, O’Byrne, and Murray define the glory hole as a cut or hole in a wall dividing two rooms that is about 16 cm in diameter.Footnote16 Don Bapst suggests that the glory hole can be used to expose genitalia to be “fellated or masturbated” by another person without revealing one’s identity.Footnote17 Preventing visual rapport and redacting the usual way in which one can visually inspect a sexual partner, glory holes find their place in dim rooms dedicated for consensual sex between adults.Footnote18 As Holmes, O’Byrne, and Murray explain the glory hole can be found in public facilities that gay men frequent.Footnote19

The key feature of the glory hole is to distance the participants of the sexual act emotionally from one another.Footnote20 Typically, the apparent sexual pleasure flows from an encounter with an arbitrary individual. The experience forces the participant to imagine the partner on the other side of the dividing wall – an encounter that is extra-ordinary or transcendental. In a subculture that composes a social minority where the recognition of the individual is often compared to a stereotypical queer figure with a very specific body type, one might suggest that this imaginative process of fetishization becomes eased. This type of sexual encounter is often not preempted or followed up and is normally frowned upon by conservative society. But the anonymity that the glory hole provides in its architectural configuration ensures that no shame is felt as the participants are not identifiable. Following Bapst, this anonymity is not only a protection from the feeling of shame but also an enhancement to sexual arousal.Footnote21 Some scholars argue that responses to a glory hole are varied and should not be thought of narrow-mindedly. In research conducted by Edward Sumerau, Ryan Cragun, and Lain Mathers, one of the users of the glory hole reported experiencing an epiphany and “feeling of peace that washed over [them].”Footnote22 The shared pleasure can come from the act of dissent from the norm, be it sexual, social, or spiritual.

Judith Butler suggests that risky or shameful encounters may enhance the collective endeavor to perpetuate a sense of togetherness signified by the ‘I’, ‘you’, ‘we’ dialectic proposed by Adriana Cavarero.Footnote23 It allows for the complexities and frictions of the acting-out-identity in real-life to be missed and a new, potentially less complete image to take over. The imaginary is attained through the explicitness of the vulnerabilities encoded in the precariousness of the encounter and a wish to recognize the object of desire in the unseen. This loose-knit relation requires a type of creative empathy and an imaginary faculty which must be emotionally and sensually challenging and to some, perceptibly tantalizing. The assumption of the identity’s form is similar to the Cartesian Cogito or the process of producing a conceptual persona that architects use when designing. In this research, the design drawing methodology employing the conceptual persona was developed through conversation.

Conversation as Methodology

The specific method deployed for this research involved direct communication between the author with three architectural designers –Mary, Adam and Patrick. The brief that was issued to them included the definition of the glory hole (as an architectural element in the queer subculture) and that of the conceptual persona. The task asked all three to use the persona to interrogate their design process and include it in orthographic plan, section, elevation, and other necessary drawings.

As with any research which includes creative input from third parties, the research methodology used here was iterative. Conversations digressed flowing with each individual participant’s input and their design aspirations. As such, each architect will be discussed separately. Notably, all three designers expressed shared concerns included issues of hygiene, cleanliness, and olfaction. Curiously, they all suggest that flexibility is a key aspect of the design; each propose ways in which their architectural design does not conform to a standardized user body image. Mary notes that: “[…] there is not a right or wrong way to use [the glory hole], you decide what is right for you. Maybe you want to control the angle that suits you, but maybe you just want it to randomly change to play a different game.”Footnote24 The architects’ responses here are sequential and follow the conversation that was conducted with each as to how each conceptual persona evolved.

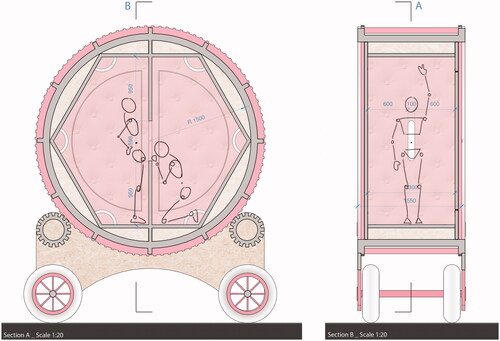

Mary’s Home Delivery

As an experienced architect, Mary approached the design task with diligence and professionalism and designed what she called a device to attain a “new and exciting sex experience.”Footnote25 She explains, “Based on the history of the ‘glory hole’, we could consider anonymity as one of the main characteristics […]. Considering the highly variable times we are living in I understand mobility and adaptation are matters to take into account in any future proposal.”Footnote26

Mary suggests that withdrawing from the public domain plays a significant part of the experience for her conceptual persona. An interesting aspect of her message is mobility – a characteristic of the architecture which has not been mentioned in literature but one that Mary finds fitting in the cultural context. Mary’s correspondence includes sketches ( and ) which indicate how flexibility fits into her understanding of the ‘glory hole history’. Although the public is not present in her drawings one can easily imagine Mary’s vehicle making its way through a busy square in a center of a town reminding people of the historicism of glory holes, seeking the next bashful persona that would want to use it. Mary explains:

Figure 1 Concept sketch by Mary (Mary Citation2020).

Figure 2 A developed sketch of Mary’s design intent (Mary Citation2020).

Now more than ever, the takeaway spirit is inserted in society. It is that idea that made me consider this element needs to be movable, not only for secret encounters but a service for anyone up for a new safe sexual experience. A final look still to be determined, it definitely needs to be on wheels. There are already plenty of pleasures coming to our doorstep like our favourite food. Why not to have a safe-sex delivery service as well?Footnote27

Even though we never see any context in Mary’s drawings her persona, understood as ‘anyone’, reaches out to the public through interest in safe sex. Mary brings the space closer to her and the reader’s own ‘doorstep’. She follows her imaginative sketches with a detailed section of the design that remains playful. The detailed cylindrical cabin takes a more emotive dimension, inviting the reader to occupy the sketch: “There is something appealing about occupying a space unlike any other in your day-to-day life. In this case, the wheel represents access to a different dimension whose rules are unknown to you. The excitement forgoing the unveiling of a mystery.”Footnote28

The definitions of the characteristics of Mary’s persona comment on the issues of contemporary society and the puritan approach to sexual practices as well as the contemporary attitudes to social space. Mary’s drawings are also express a link between desire and demand in contemporary markets through door-to-door delivery during COVID-19. Her becoming of the naïve persona is used instrumentally to diverge into a generalized approximation of inhabitation fit for the space outside. The conceptual persona in her drawings is sketchy and difficult to empathize with but her text invites the reader to occupy her cabin design with her. Each iteration delves deeper into the world of sexual fantasies enticed through familiarity.

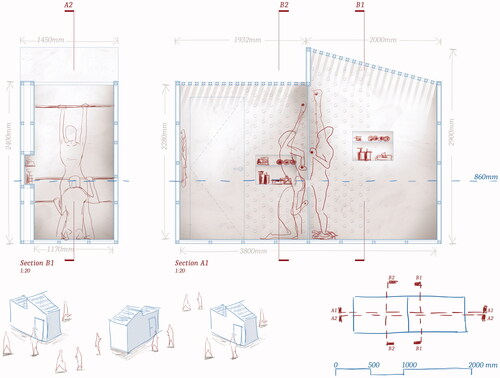

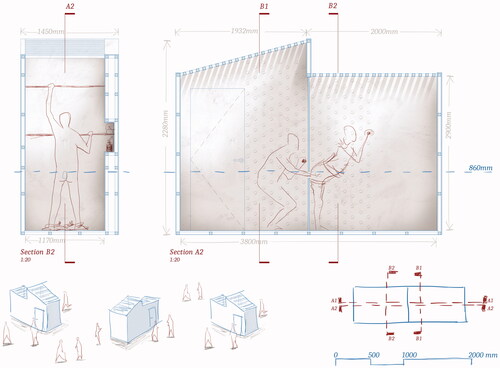

Adam’s Portal

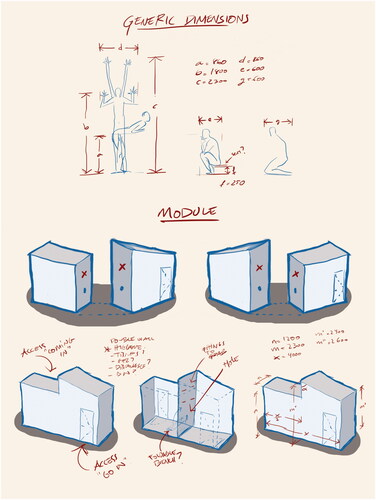

Adam’s initial correspondence included quirky sketches () and a list of bullet-points expressing “reflections and thoughts”Footnote29 including:

Figure 3 An initial sketch of Adam’s design intent (Adam Citation2020).

1 - Keep its underground atmosphere.[…]

5 - Access on opposite faces.

6 - The shape of the module is determined by its use so would be quick to recognize.Footnote30

Similar to Mary’s text, the presence of the public is indicated in Adam’s drawings is palpable and explicitly given bodies (bottom of ). He narrates that the conceptual personae might want to exchange glances as they enter. Adam’s rhetoric suggests that the cabin would be a device that could introduce people to the concept of pleasure and lust attained through the transgression of social boundaries much like crossing a portal into a new and unexplored world.

Figure 4 A detailed design by Adam (Adam Citation2020).

The connection of the module to the public seems to be the driver of the design for Adam, although at the scale of the conceptual persona he dissolves the specificity of the characteristics of the inhabitant’s body and suggests opening the discussion to all sexes and sexualities on a deeply empathetic level. Adam explains that “[n]ot only a penis but a hand can be inserted so either a woman and a man can be on both sides.”Footnote31

Adam’s sketches are more revealing and present his conceptual personae in the throes of passion. For Adam, the design exercise allows the exploration of an emotional experience of transiting into an exciting new dimension rather than a rhetorical device introducing an attitude to sexuality or economy. His drawings of the conceptual persona are much more engaging and provocative than Mary’s and his narrative is more detailed in the timescale of the narrative that it encompasses. At the same time, the text does not draw the reader in as Mary’s did –because of its abruptness. His textual concerns center on atmosphere, situation, and the public’s attitude to casual sexual relations. The narrative and the sketches suggest that Adam imagined what it would be like to enter the module.

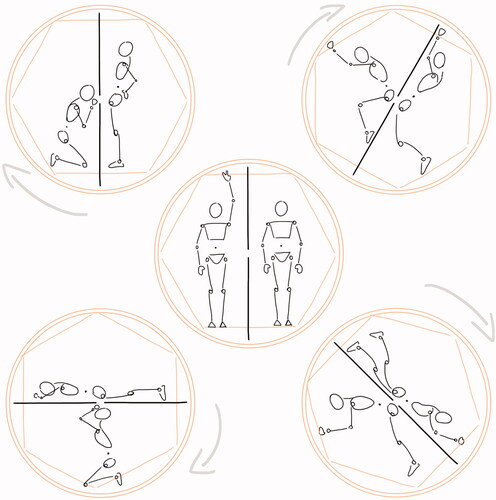

Patrick’s Soft Latex Finish

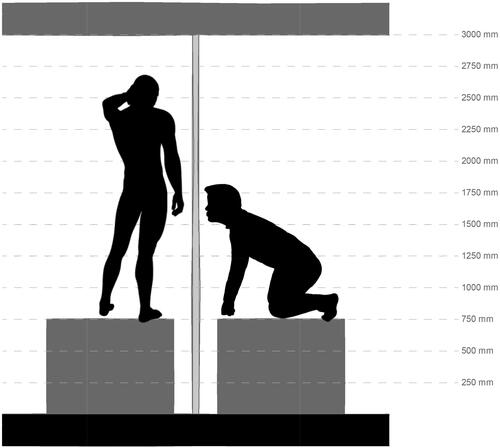

Patrick explores the ergonomics of the conceptual persona’s body. Patrick’s first sketch () is explained, “I explored the positions of the bodies in various situations and indicatively noted key measurements. The findings will aid in creating the best possible arrangement to facilitate a better experience as well as positioning [of] the wall openings.”Footnote32

Figure 5 Patrick’s initial sketch (Patrick Citation2020).

Here, the interface of the body and architecture becomes a problem that is de-contextualized and much less connected to any socio-political commentary or the idea of the transgression of the rules that Mary and Adam were working with. The core of Patrick’s concept is the experience and spatial configurations of what a glory hole may offer in relation to the alignments of orifices. However, the personae in Patrick’s drawings are shaded to allow for anonymity and show two male figures without sexual organs in compromising positions.

In subsequent iterative drawings, Patrick retracts from his bold use of shaded figures and reasons that appropriate support to withstand pushes and pulls should be considered in the design process. He adds:

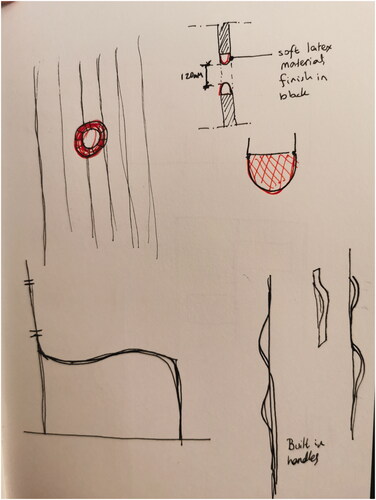

[D]ue to the proximity of the hole to one’s genitals, the materiality will respond to the safety and pleasure of the participant. In biology, the lips and the anus are the two ends of a pipe called the Alimentary Canal. The glory hole functions as the lips and the anus […]

The opening will be soft and warm yet non-absorbent and durable to provide a comfortable feel when touched whilst withstanding the inevitable wear and tear. Footnote33

The design decisions which Patrick makes are reasoned and communicated clearly. His narrative positions the conceptual persona in an abstract space as ‘one’ that moves, touches, and has genitals but his drawings argue against this. Patrick keeps a professional demeanor and refers back to a formal way of articulating his intent highly regarding ergonometric qualities of architectural detail. His early propositions complement one another – never telling the full story. The final proposition also contains a series of hand-drawn sketches indicating the small-scale detail of the hole itself which as Patrick envisioned had to be encased with a latex material ().

Figure 6 Patrick’s detailed sketch (Patrick Citation2020).

Conclusion: The Conceptual Persona as a Reflective Tool

Here, architects challenge the role of architecture in the interface between the body and the architectural element with a glory hole and all the complexities that come with designing for it. This practice-based research offers an avenue to explore the use of a conceptual persona as a candid expression of the architects’ design sentiments. The core issue at hand is the relation between the deepest functions of the body, the feeling of lust/excitement/shame that may be brought by engaging with the glory hole, and the social and/or political issues that shook the world in 2020. All of the designers that agreed to take part in the research created unique conceptual personae and represented them in their text and drawings, giving them a body and emotional states. In comparison with one another, the architects prioritized and reflected on different aspects of the design and overlooked others showing the non-comprehensive partiality of the imaginary user construct in the architectural setting. Mary neglects the materiality of the hole and Patrick fails to consider the context. For all, the conceptual persona was fragmented to make a fuller but never complete image. In this sense, the personae are what Deleuze and Guattari might refer to as a heterogeneity – an affiliation of concepts that are grouped through their zones of semantic neighborhoods.Footnote34 In this way, the methodology is incomplete and should be complemented with other methods of representation. It is difficult to discern the extent of the detail that is essential to include in constructing the personae yet it is useful in attaining a coherent focus. If the simplest functions necessitate a relational composition of an abstract identity, then when should the designer stop their construction to fill the needs of the question they are answering? This may have lied at the core of Kant’s grievance issued to Descartes.

It could be said that the public quality of the device forced the architects to redact the specificity of the bodies’ conceptual personae to allow for flexibility and adaptability to a wide range of body types. In suggesting this, the designers expose friction in the methodology between accessibility to all and specificity of architectural element to the imagined inhabitant. At the same time, all personae also exhibit very specific and varied emotional responses such as excitement, lust, and pleasure – aspects specific to the intangible character of the imagined situation.

At times, the characteristics of the conceptual persona diverge into other areas of life making them overtly able or unable to engage with the idea of sexual encounter through a glory hole. Using the analogy of what does it feel like to be a mother? What does it feel like for the other to feel lust? Can a mother feel lust and is it necessary for her to feel it to answer the posed question? If she doesn’t need to feel lust, then how does that impact on the necessary characteristics of her being? In this sense, the idea of the conceptual persona presented in public is problematic – never entirely enough to convey the full dimension of the multiple identity problem while at times borrowing the architect’s experiences or aspirations. It also has to be said that the idea of sexuality as exercised in the experience of the glory hole is fragmentary and it is argued that the ideas that come to materialize it may not fit together neatly. This is not to say that conventional sexual practices do or that in some way the sheer idea of sexual pleasure is a unified and non-divisible construct. To refer back to Deleuze and Guattari it might be said that the elements that come to form the concept are not like fragments of a “jigsaw puzzle” but rather “throws of the dice.”Footnote35 Much like the pleasures of participating in all relations in the cultural context, they rely on the haphazardness and unintentionality of an imminent moment. Similarly, producing the conceptual persona engages the designer, their cultural context, and drawing practices, and the reader, into a game of dice-throwing to seek unity in the designed object/yet-to-be situation.

Mary approached the matter by gradually introducing the reader to the general notion of desire in the COVID-19 pandemic. Her conceptual persona travels and engages with a thesis on the economy of pleasure and the difficult and diminishing concept of delayed gratification. Adam’s take on the device is similar to Mary’s but goes deeper into developing an understanding of the emotional side of the space and the fetishism of leaving the public realm. Patrick’s conceptualization of the persona is corporeal and ignores the socio-political or economic functioning of society to understand the deeply machinic assemblage of the bodies and architecture in this type of sexual encounter.

In summary, the reflective use of a conceptual persona can serve as a tool in the exploration of a designer’s preconceived ideas of normal or ethical conduct in the state of culture at the time of designing. It can serve as an introduction to the ideas behind the architecture or debates that are being had in society; and if the design commission asks for a nonstandard solution, the conceptual persona, as an approximation of inhabitation, can aid the architect’s role in engaging in a heightened creative examination of the event they are to ordain with an envelope and society’s take on it.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the three designers who took the time to produced designs for this research.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Charles Drożyński

Charles Drożyński (PhD) is a Senior lecturer, working at the University of West England, and a Part II architect. In his academic career, he has taught and lectured in several universities across the UK. His Ph.D. thesis, written in Cardiff University, focused on the intersections of architecture and post-linguistic schools of thought; in particular, those put forward by Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. His research examines the subvert in society and architecture and the development of new ideas and the intricacies of their introduction into socio-economic markets.

Notes

1. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, What is Philosophy? (London: Bloomsbury, Citation1996)

2. Dave Holmes, Patrick O’Byrne, Stuart Murray, “Faceless Sex: Glory Holes and Sexual Assemblages,” Nursing Philosophy 11, no. 4 (Citation2019): 250–259.

3. Don Bapst. “Glory Holes and the Men Who Use Them,” Journal of Homosexuality 41, no. 1 (Citation2001): 89–102.

4. Johan Andersson, “Homonormative Aesthetics: AIDS and ‘De-Generational Unremembering’ in 1990s London,” Urban Studies 56, no. 14 (Citation2019): 2993–3010.

5. Health Department of New York City. Safe Sex Announcement During the Pandemic Lockdown, COVID-19 – Point 4, Bullet-point 4 (Citation2020).

6. Deleuze and Guattari, What is Philosophy?, 32.

7. Ibid., 30.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid., 24–27.

10. Ibid. 32.

11. Lydia Kallipoliti, “Feedback Man,” Aftershocks: Generation(s) 13/14 (Citation2008): 115–118.

12. Alain Pottage, Architectural Authorship: The Normative Ambitions of Le Corbusier’s Modulor (London: Architectural Association, Citation1996).

13. Nigel Coates, Narrative Architecture (London: Wiley, Citation2012).

14. New York City's Health Department, New York City’s Safe Sex Announcement During COVID-19. (New York: New York City Health Department, 2020). point 4, bullet-point 4. p. 3.

15. Johan Andersson. “Homonormative Aesthetics: AIDS and ‘De-Generational Unremembering’ in 1990s London,” Urban Studies 56, no. 14 (Citation2019): 2993–3010.

16. Holmes et al. “Faceless Sex,” 250–259.

17. Don Bapst, “Glory Holes and the Men who use Them,” Journal of Homosexuality 41, no. 1 (Citation2001): 89–102, 90.

18. Michael Helquist and Rick Osmon, “Beyond the Baths: The Other sex Businesses,” Journal of Homosexuality 44, no. 3/4 (2003): 177–201.

19. Holmes et al., “Faceless Sex.”

20. Bapst, “Glory Holes and the Men who use Them.”

21. Ibid.

22. J.E. Sumerau, Ryan T. Cragun, Lain A. B. Mathers, “I Found God in The Glory Hole: The Moral Career of a Gay Christian,” Sociological Inquiry 86, no. 4 (Citation2016): 618–640.

23. Judith Butler, “Giving An Account of Oneself,” Diacrics 31, no. 4 (Citation2005): 22–40.

24. Mary, email exchange with Charles Drożyński, June 20–August 8, 2020.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid.

29. Adam, email exchange with Charles Drożyński, June 20–August 8, 2020.

30. Ibid.

31. Ibid.

32. Patrick, email exchange with Charles Drożyński, June 20–August 8, 2020.

33. Ibid.

34. Deleuze and Guattari, What is Philosophy?, 20.

35. Ibid., 35.

References

- Adam, email exchange with Charles Drożyński, June 20-August 8, 2020.

- Andersson, Johan. 2019. “Homonormative Aesthetics: AIDS and ‘De-Generational Unremembering’ in 1990s London.” Urban Studies 56, no. 14: 2993–3010. doi:10.1177/0042098018806149

- Bapst, Don. 2001. “Glory Holes and the Men Who Use Them.” Journal of Homosexuality 41, no. 1: 89–102. doi:10.1300/J082v41n01_02

- Butler, Judith. 2005. “Giving An Account of Oneself.” Diacrics 31, no. 4: 22–40. doi:10.1353/dia.2004.0002

- Coates, Nigel. 2012. Narrative Architecture. London: Wiley.

- Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. 1996. What is Philosophy? London: Bloomsbury.

- Helquist, Michael, and Rick Osmon. 2003. “Beyond the Baths: The Other sex Businesses.” Journal of Homosexuality 44(3/4): 177–201.

- Holmes, Dave, O’Byrne, Patrick, Murray, Stuart. 2019. “Faceless Sex: Glory Holes and Sexual Assemblages.” Nursing Philosophy 11, no. 4: 250–259. doi:10.1111/j.1466-769X.2010.00452.x

- Kallipoliti, Lydia. 2008. “Feedback Man.” Aftershocks: Generation(s) 13/14: 115–118.

- Mary, email exchange with Charles Drożyński, June 20–August 8, 2020.

- New York City Health Department. New York City’s Safe Sex Announcement During COVID-19. 2020. New York: New York City Health Department.

- Patrick, email exchange with Charles Drożyński, June 20–August 8, 2020.

- Pottage, Alain. 1996. Architectural Authorship: The Normative Ambitions of Le Corbusier’s Modulor. London: Architectural Association.

- Sumerau, J.E., Ryan T. Cragun, and Lain A.B. Mathers. 2016. “I Found God in The Glory Hole: The Moral Career of a Gay Christian.” Sociological Inquiry 86, no. 4: 618–640. doi:10.1111/soin.12134