Abstract

In this study, we follow-up on the social construction of an organizational image focusing on the role of luxury watches worn at work. In this way, we discuss the crucial role of employees' aesthetic appearance as a projector of organizational values to internal and external audiences. Drawing on the theoretical lenses of gestalt theory and the literature on aesthetics of labour, we examine the dynamics of luxury display in organizational settings via a qualitative approach, a netnography based on 193 topical entries. The netnography was guided by a pre-study conducting interviews with high level experts from the luxury watch industry. Our findings show that the display of a luxury watch at work can contribute to a harmonious organizational image. However, professional settings exist where the watch triggers an inconsistency in an employee's appearance relative to the organization that is being represented. Thus, disturbing the overall organizational image. Adopting a gestalt theoretical perspective to this social construction process, we define the "organizational gestalt": as a dynamic projection of organizational values informed and conveyed by aesthetic, organizational representations (in this study: employees' wristwatches). We theorize that a gestalt-switch – a conversion of a previously stable organizational image – occurs when an employee's appearance projects values that conflict with the established aesthetic, organizational representations. As a consequence, the authenticity and credibility of the employee and the organization may suffer.

Introduction

In 2010 Swiss bank UBS made headlines sending a dress code to its customer-facing staff that explicitly encouraged the use of a wristwatch, given that the watch carries the notion of "reliability and great care for punctuality".Footnote1 However, as wristwatches are often more than simple indicators of time, their display in an organizational setting can also be controversial.Footnote2 Anecdotal evidence shows that particularly luxury timepieces may lead to unwanted outcomes when worn at work.Footnote3 In a recent newspaper article, a reporter recalls a visit to the dentist, who was wearing a luxury watch during the treatment.Footnote4 Although the dentists' work was satisfactory, the journalist concluded that she did not want to return to the dental practice, given the doubt that the organization might prioritize profits over patient well-being.Footnote5

In this paper, we follow-up on this peculiar phenomenon drawing on an emerging research strand of organizational literature that engages with the social construction and reconstruction of an organizational image in professional work settings.Footnote6 This research body stresses the processes involved in the formation of an organizational image, understood here as an aesthetic expression in the organizational context that is socially constructed and thereby grounded in “visual impression and expression”.Footnote7 In today's organizational environments, where employees often stand representative for organizational products and services, their appearance moves centre stage in this social (re)construction process.Footnote8 As a first touching point between the organization and the external environment, the work appearance of front-line employees is a crucial element when conveying organizational values and informing the organizational image.Footnote9 By drawing on the theoretical lenses of gestalt theory,Footnote10 and the literature on aesthetics of labour and branded labour,Footnote11 we examine the dynamics of luxury watch display in organizational settings. We build on a qualitative netnography based on 193 topical entries derived from one of the largest luxury watch online forums. The netnography is guided by the insights from a pre-study with interviews with high level experts from the luxury watch industry. The overall research question is: how does a luxury watch worn at work influence the social construction and reconstruction of an organizational image?

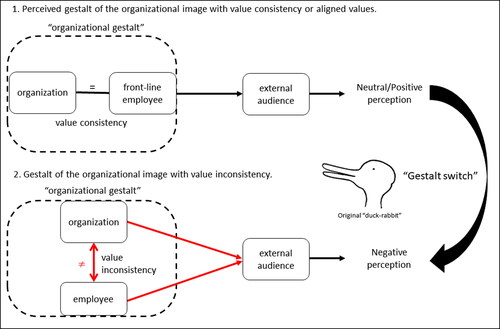

Our findings suggest that the display of a luxury watch in an organizational setting can contribute to a harmonious organizational gestalt. A gestalt "refers to something which is stable in its dynamic nature, something which is recognizable as such as a result of a process which structures its inner form".Footnote12 Thus, an employee wearing a luxury timepiece can contribute to conveying an organizational gestalt to the internal and external audiences consistent with the values attached to the organization. For example, a portfolio manager wearing a luxury watch in a client meeting may contribute to constructing a positive organizational gestalt, indicating that his personal success and organizational success are linked.Footnote13 However, as shown in the introductory example, organizational settings exist where the watch triggers an inconsistency in an employee's appearance relative to the organization that is being represented. Thus, a perception change arises when the appearance of the organizational member projects values that conflict with the established aesthetic, organizational representations.Footnote14 Therefore, a conversion of a previously stable organizational image – gestalt-switch – occurs, meaning that the external audience perceives the gestalt of the organizational image as irritated or scattered. As a result, the authenticity and credibility of the employee and the organization may suffer as the audience perceives the watch bearer to take advantage. Consequently, we define the "organizational gestalt": as a dynamic projection of organizational values informed and conveyed by aesthetic, organizational representations (in this study: employees' wristwatches).

Theoretical background

The social (re)construction of an organizational image

Organizational literature has long discussed aspects of organizational image, identity, and reputation.Footnote15 In recent years, this discourse started to take a cross-disciplinary turn, engaging with the related marketing concept of branding.Footnote16 Organizational literature thereby takes up elements from the marketing literature but goes beyond the largely behaviourist and functionalist conceptualization of an organizational brand.Footnote17 As pointed out by Kärreman and Rylander, treating a brand as a mere marketing tool means that social and communicative processes involved in the construction, recognition, and reconstruction of an organizational image are overlooked. However, these processes are essential for constructing an organizational image and ongoing branding processes in organizational settings.Footnote18 Thus, recent organizational literature is particularly suited to engage with important and peculiar organizational phenomena, such as the one described in the introduction, thereby departing where mainstream marketing literature typically ends.

Organization studies literature goes beyond marketing perspectives by recognizing the importance of both the internal and external organizational audience regarding the social construction of an organizational image. Consequently, emphasizing a broader perspective on the branding concept typically found in the marketing literature.Footnote19 Away from a narrow focus that is rather product and customer-centric, toward a broader perspective that considers a comprehensive set of internal and external stakeholders.Footnote20 In this regard, "the notion of branding relates to the practices of attempting to emphasize specific values to be associated with the organization and/or its products and services".Footnote21

In today's corporate environments, which are often characterized by service firms, the product moves further into the background. Employees stand representative of the offered goods and services. In such organizational settings, "values to be associated with the brand need to be connected to the employees (and their capabilities and characteristics) rather than a physical product (and its capabilities and characteristics)".Footnote22 In this manuscript, we follow Salzer‐Mörling and Strannegård'sFootnote23 understanding of an organizational image as an aesthetic expression that is socially constructed, grounded in 'visual impression and expression.' Crucial in this regard is the visual impression and expression of employees in relation to the internal and external audience and how they perceive and process this image.Footnote24 From this perspective, the organizational image is socially constructed and reconstructed in an ongoing manner, involving employees and the internal and external organizational audience.

Gestalt theory and the organizational image

To investigate the social construction and reconstruction of an organizational image, we draw on "Gestalt" theory, which has a long tradition in social psychology and philosophy.Footnote25 Although there is no direct translation of the German word "Gestalt," the English words "appearance," "pattern," "shape," or "form" are close approximations. In the past, gestalt theoretical approaches have been used to explore complex systems that are characterized by human interaction and when it comes to the perception and aesthetics of organizations, which makes the theory particularly suitable for investigations into corporate image creation.Footnote26

Gestalt theory focuses on perception and perceptual structuring with a holistic notion at its core: "perceiving is more than the summation of the sensations produced by stimuli".Footnote27 As depicted by Bonacchi,Footnote28 a gestalt "refers to something which is stable in its dynamic nature, something which is recognizable as such as a result of a process which structures its inner form." Consequently, gestalt theory highlights the organization's perceivable facets, such as a consistent corporate image or brand, as an aesthetic expression in the marketplace.Footnote29

We argue that it is highly relevant to adopt a gestalt perspective to better understand an organizational image's social construction in light of an internal and external audience. Thus, the objective of this paper is to explore the social construction of the gestalt of an organizational image in light of the expression and impression of employees' aesthetic appearance in an organizational setting.Footnote30 To do so, we build on recent organizational literature that focuses on employees' central role in projecting an organizational image.

Aesthetics of labour, branded labour and conspicuous luxury consumption at work

We discuss the social construction of an organizational image through the theoretical lenses of aesthetics of labour and branded labour, two related and complementary literature streams.Footnote31 At the core of this literature body are questions on how an employee's appearance can positively or negatively convey the organizational image, thus, contributing to favourable or unfavourable perceptions thereof.Footnote32 The research thereby focuses on the organization's internal and external relationships and the respective audiences, recognizing the critical role that employees' physical appearance can play in image formation.Footnote33 Thus, whereas the aesthetics of labour literature focuses more on the internal organizational perspective, the branded labour literature is more concerned with the external view.

Past research on aesthetics of labour has discussed the adverse effects that can go along with an employee or job candidate having "the wrong look".Footnote34 Here, intrinsic or extrinsic physical 'imperfections' can be a source of bias and even lead to different forms of workplace discrimination.Footnote35 For example, service sector personnel are often judged by their physical appearance, whether they have a 'desirable look' that fits the organization. Attributes, such as body art and piercings, can be a potential disadvantage in this regard.Footnote36

In addition to the research stream on aesthetics of labour, research about "branded labour examines employee appearance on the consumption side, with an emphasis on consumers' perceptions of front-line employees".Footnote37 In this regard, front-line staff's actions and appearance are crucial, given that they represent the link that connects the organization with the external environment. Employees can be thought of as manifestations of the organization's offerings and, as such, project the corporate image to the outside world.Footnote38

When interacting with an internal or external audience, employees are, therefore, decisive actors contributing to the construction and reconstruction of an organizational image, and crucially positive or negative perceptions of it.Footnote39 As depicted above, body art and piercings may appear as undesirable characteristics, raising issues for employees. However, recent research cautions that such attributes can also turn into an advantage, positively projecting specific organizational values in some contexts.Footnote40 In contrast to these previous studies, in this paper, we focus on a potentially desirable attribute, a luxury watch forming part of an employee's appearance.

Although luxury watches take up a substantial presence in the everyday workplace and organizational settings, their role in the overall dynamics between employees' appearance and the construction and reconstruction of an organizational image appears to be an overlooked aspect in current literature.Footnote41 Luxury watches are particularly interesting to study, as they form part of an employee’s appearance and connect the individual to the work environment.Footnote42 As outlined by Woodward,Footnote43 accessories such as luxury watches mediate the relationship between the wearer and the work context. The watch as a material object of high value can convey aspects of the self to the external environment and may be worn for strategic reasons.Footnote44 Given that the watch represents an element of the employee's appearance, and as such, becomes part of the interaction with an internal and external audience, a luxury watch may, therefore, contribute to a favourable or unfavourable perception of the employee as well as the overall organization.Footnote45 Thus, the watch may play an important role in the social construction and reconstruction of an organizational image and the way in which this image is perceived and processed by an audience.Footnote46 Consequently, by examining the role of luxury watches displayed by employees in organizational settings, we follow-up on the social construction and reconstruction of an organizational image in the form of the "organizational gestalt." Thus, we strive to answer the questions: how does a luxury watch worn at work influence the social construction and reconstruction of an organizational image?

Methods

To answer the research questions, we adopt a qualitative research approach based on a netnography. The development of the netnography was informed by insights gained from a pre-study drawing on descriptive expert interviewsFootnote47 with high level experts from the luxury watch industry. The netnography follows the approach of a non-participatory netnography study.Footnote48 Given the peculiarity and sensitive topic of luxury watches and their usage in organizational contexts, we adopt this approach to gain thorough insights into the complex and dynamic phenomenon of organizational image changes. In this regard, pre-study expert interviews combined with netnography are particularly relevant for entering niche communities, such as luxury watch users (users of a highly exclusive products), and exploring in-depth their mindset and reasoning processes.Footnote49 Thus, the research followed two stages:

First, expert interviews were conducted to make a quick and deep dive into the phenomenon of organizational image change.Footnote50 In the second stage, a netnographic study followed. In contrast to traditional ethnography, netnography helps to observe openly accessible information generated by an online community in an unobtrusive manner, thereby benefitting from naturally arising communication between the community members.Footnote51 Thus, the netnographic approach aimed at uncovering the deeper motivations, meanings, and attitudes of a large online community in displaying luxury watches in organizational settings. The netnographic study thereby benefited from the descriptions of the experts, highlighting the need to adopt an unobtrusive approach to tap into the reasoning processes of luxury watch owners and their experiences concerning the sensitive aspect of conspicuous luxury consumption in an organizational setting.Footnote52

Pre-study: expert-interviews

We used pre-study expert interviews to dive into the phenomenon of organizational image change.Footnote53 The expert interviews thereby provided the opportunity to start the research project by gaining initial understandings of the luxury watch environment and approaching luxury watch display in organizational settings from multiple angles. In this manner, we carried out semi-structured interviews with experienced industry experts (on average, over 20 years) with diverse expertise fields. Interview partners were identified and contacted through information provided in a public database of the Federation of the Swiss Watch IndustryFootnote54 combined with LinkedIn profiles.

Experts received a semi-structured interview guideline before the interview. Thus, it was ensured that the experts had a clear understanding of the interview objective. They could remain anonymous, stop the interview at any point, and leave questions unanswered. Appendix AFootnote55 lists the wording of the guiding questions that were asked to the experts. The interviews were conducted in March 2019, lasted between 20 and 60 minutes, and were conducted in English, with one expert responding in Italian. In accordance with interview partners, four of the five interviews were recorded. Experts included a luxury watch historian (face-to-face interview in Switzerland), a managing director (Skype interview), a principle of a luxury watch competence centre (phone interview), and two experts in managing positions in marketing and sales (face-to-face interview in Switzerland; phone interview), as well as customer services (phone interview). Experts were asked if they wanted to be quoted anonymously or with their identity. Quotations used further below indicate their decision accordingly by adding or not adding a name.

Summarizing interviews: perceptions of luxury watches and organizations

We first summarized the interviews in protocols and categorized them according to emergent and recurring elements.Footnote56 summarizes the initial understandings that we gained from the interviews along with major themes (micro, macro), which we elaborate next,

Table 1 Themes arising from the pre-study.

The pre-study expert interviews revealed that perceptions of luxury watches worn by employees should be observed according to two broader environments: luxury watch contexts and non-luxury watch contexts.

Luxury watch contexts: aesthetics perceptions

From the interviews, it became clear that organizational and professional settings explicitly linked to luxury watches represent a particular environment that has to be observed differently from other organizational environments when it comes to the display of luxury watches. In settings related to luxury watches, front-line employees wearing a costly timepiece on their wrist are seen as a natural element of the organizational environment. Here, the watch is also perceived from an intrinsic perspective that is focused on the aesthetic attributes of the watch, as one of the interview partners explained:

"It [the watch] is first a piece of art. (…). What is very strange with watches is actually the system, the mechanism is coming back to more than 200 years ago (…) It is something quite old in terms of technology, but so magic when you start to wind your watch and you see it moving. (…) there is something which is, I would say, extremely emotional." [Managing director, luxury market development company].

Thus, the front-line employee with a luxury watch on the wrist is perceived as a manifestation of the organizational product offerings as a carrier of the corporate image projected to customers.Footnote57 Therefore, positive perceptions toward the front-line employee and the organization are common, as the experts indicate. Consequently, conspicuous extrinsic consumption of luxury watches is seen as a desirable attribute of the work setting.Footnote58 However, this aspect can differ in non-luxury watch contexts.

Non-luxury watch contexts: indifference, ethical conflicts, and gestalt switch situations

According to the experts, luxury watches worn by front-line employees have to be observed differently in contexts where watches are not the core element of organizations' daily business. An interview partner explained that not everyone might recognize a luxury watch and thus can have neutral or indifferent perceptions:

"The general public is getting less and less aware of a watch." [Principle, luxury watch competence center]

Another interview partner added that neutral or positive perceptions can shift given the function of the front-line employee relative to the represented organization:

"Yes, it [referring to a luxury watch] can give a bad signal to the people in front of you. Especially if you are an official in politics or something like that." [Manager, luxury watch customer services]

The expert drew a link between the luxury watch's external audiences' perception as a negative indicator that may disturb the relation between the front-line employee and the represented organization. As specified by the expert, this may go along with a lack of trust due to contradictory values between the front-line employees flaunting of the luxury item and the organizational function occupied. Thus, an external audience may sense a potential ethical conflict. In a similar vein, another expert highlighted the fear of front-line employees wearing their luxury watch during client encounters, providing insights into a potential gestalt switch situation.

"Some of my customers that are working in the insurance industry take-off their Rolex prior to a client meeting. They are afraid that the watch could send a misleading message, for example, that they make a lot of money and that they might want to rip off their clients" [Manager, marketing and sales of luxury watches]

The expert's remark on the moral conflict and the perception change that could follow from a luxury watch display in a client encounter is noteworthy. In a similar vein, another expert indicated a potential value conflict between the front-line employees' position and the external audience, discussing the example of a politician as an organizational representative:

"It would be kind of logical if you pay your representatives' tax money and then they wear a very expensive Rolex watch. It might, for a certain type of people, be a little bit felt as a betrayal. But I think it would be a very, very small number and the general public is getting less and less aware of a watch." [Principle, luxury watch competence centre]

The expert described that social media plays a vital role as a digital extension of the organizational context in today's digital environments. In this sense, the front-line employee's appearance as a first touching-point between an external audience and the organization may expand in terms of time and space. Thus, the perception of a front-line employee is not limited to the immediate moment as an in-situ experience, but captured and saved as a digital image; it can be distributed via digital means, reaching a broader audience that may see the watch bearer at any later point in time:

"But then you have some clever bloggers that are very influential and suddenly spot a politician wearing an expensive watch and then decide to take him down online or something like this." [Principle, luxury watch competence centre]

The descriptions by the expert connect to and are also corroborated by news reports about organizational leader's that were caught in social media scandals due to the luxury watch they wore as representatives of their respective organization.Footnote59

Netnography

Building on the descriptive insights from experts-interviews, we collected netnographic data to gain deeper understandings on a broader basis of the dynamics between employees' appearance and the social (re)construction of an organizational image. In this regard, we looked for a suitable online community to collect netnographic data that fulfilled the following criteriaFootnote60: (1) the size of the community and number of posts (as an active community) (2) rich data in terms of thread length and post contents (3) diversity in forum members and interactions, and (4) relevant concerning the research question. After an online search that revealed several luxury watch communities (particularly on Linkedin, yet with a very small number of active members and few threads, unrelated to the research question), we selected the "Rolex forum" as a field site that corresponded to the above criteria. The Rolex forum is an online forum that is not affiliated with the luxury watch company Rolex.Footnote61 It represents one of the largest online forums related to luxury watches, given its user base of 246,588 registered forum members, which have contributed to numerous threads (710,559) and posts (10,581,797) related to multiple luxury watch brands at the data collection cut-off date in early August 2020. Thus, it represents an open discussion forum about multiple topics related to luxury watches, not limited to a single watch brand. The forum topic "Wearing a Rolex when meeting clients" appeared as the most suitable fit for the selection criteria, with 193 comments in total. The first comment was made in May 2016. The last comment was made in August 2016. Overall, 146 different forum members commented on the topic. 125 forum members made a single comment, and only 21 members commented more than one time. The four most active forum members commented more than three times: (clb521: 12 comments), (speedolex: 8 comments), (jdlc1406: 4 comments), (jmiicustomz: 4 comments).

Analysis and result: "wearing a rolex when meeting clients"

In line with netnographic data analysis,Footnote62 we used open-coding to iteratively label and categorize the forum data, thereby grouping the emerging data categories while moving between literature and nascent themes.Footnote63 Through this analysis, 33 salient second-order themes emerged. Subsequently, these themes were further refined into 6 first-order themes. Appendix BFootnote64 lists the themes together with representative quotes from forum members. The following results with exemplary quotes show the perceptions, attitudes, and broader thought processes of luxury watch owners, reflecting on wearing a luxury watch in organizational settings and professional interactions.

Personal values

Many of the forum members stressed that wearing a luxury watch is important to them regardless of the context. They strongly associate the watch with personal values and positive feelings. In this way, they see the luxury watch as an aesthetic object that serves as an expression of the wearer's personality:

"I find that those of us who collect and wear watches because it's our hobby and passion manage to "pull it off" in all social and business situations quite well as we don't think of the watches as s "show of affluence". Rather, they are reflective of our enjoyment if anything and that is what shows to outsiders (if anything is evident at all)" [Mfrankel2]

Strong personal emotions and intrinsic values are linked to the display of the luxury watch. Thus, rather than making a connection with the organization or the audience, these forum members depict the watch as an object directly linked to their personality, detached from contextual aspects. Consequently, the watch is worn without additional considerations about external perceptions thereof.

Indifference

Several forum members indicated that luxury watches represent a very particular item, which is not always noticeable in organizational contexts. Therefore, it may often be met with indifference. In terms of interactions with an external audience, it was stressed that clients may lack awareness of luxury watches, such that neutral perceptions prevail: "Unless it had diamonds on it, most people won't notice and even less will care" [forum member myc ritz]. The forum members also indicated that their personal attention for others wearing a luxury watch is high. Nobody has ever noticed…I have noticed many watches in client meetings myself though: chuckle:" [forum member LightOnAHill].

Indicator for personal and organizational success

Another salient theme that emerged from the forum community is the perception of the luxury watch as an indicator of personal and organizational success. Several members made a direct connection between the display of the luxury watch and financial accomplishments, personal and organizational: "If I saw an attorney wearing a rolex compared to one with a Casio I would want the attorney with the Rolex because we view it as financial success, so they must be good at their job" [cpark]. Here, the luxury watch is perceived as a success symbol and indicator for competence, effort, and experience, which indicates the performance of the organization that the individual represents. In this regard, the luxury watch positively reinforces the organizational image that the employee projects.

Value consistency: employee and organization

From the forum entries, it became clear that a luxury watch worn in an organizational setting can be an essential element to show the employees' fit and belonging to a specific organization. The watch can thereby serve as a linkage between the employee and the organization, indicating the belonging. The forum members specifically associated legal, wealth management, medical, architectural, and design-related organizations with the display of luxury watches:

"Nobody has ever had a problem, but the position I've put myself in practicing law and my field make it easy and culturally acceptable. Presence is important in the courtroom, and wearing what I like and looks good to me causes me to project well." [LightOnAHill]

Thus, similar to the interview partners' comments, these settings can be seen as luxury watch contexts. As such, the watch worn by the employee forms part of the organizational image. Further, forum members hinted that a luxury watch can be indicative of seniority within an organization, particularly concerning executive positions:

"When someone sees $7,000 on your wrist it also tells them you are a well-established executive in your industry, not some newb or retread trying to keep up in a $200 Seiko. I'm an EVP and when I hire 20 year veterans in my industry as VP's or Directors, wristwear matters, if they want a six-figure job they'd better have some visible symbols that show they've been successful and care about the finer things. "[speedolex]

Value inconsistency: employee and organization

In contrast to the previous description, several forum members outlined a potential value inconsistency between the organization and an employee wearing a luxury watch at work. From an internal perspective, a luxury watch displayed to colleagues or superiors can be associated with personal value conflicts and discomfort, as some expressed. Particularly concern over judgment or misinterpretations by the internal organizational audience was raised, indicating that the watch may lead to unintended or adverse consequences for the wearer:

"I also used to work with people who were very frugal and if I wore a Rolex all the time they would say I would never need a raise since I can afford a Rolex." [Stelyos]

Therefore, some forum members remarked that the display of a luxury watch can be delicate and that they would refrain from wearing it in an organizational setting to avoid any form of conflict, especially when being new to an organization. Consequently, a luxury watch worn during a job interview was controversially discussed, with forum members mentioning that it may or may not correspond with organizational values and in- or decrease the applicants' chances to join the organization. A crucial aspect appeared to be the notion that the wearer of the luxury timepiece could be perceived as asymmetrically benefitting from the organization:

"Wear your Rolex on your interviews. It would be way more uncomfortable if they didn't see it until after you started a new position. At that point they'll probably just assume it's a new purchase and bad feelings could result around the office if they think you bought it after the job offer. Certainly would make some bosses feel like maybe they paid you too much. [904VT]

Gestalt switch situation

A large part of the online community's discussion about wearing a luxury watch in an organizational context centres on displaying a luxury watch when interacting with the organization's external audience. Meeting (new) clients was deemed to be one of the most sensitive situations. Forum members mentioned that when products or services are offered in a sales context, a luxury watch may well be noticed by clients and may trigger adverse effects for the wearer and the represented organization. Several second-order themes emerged, underlining the characteristics of such a situation. In such a context, a luxury watch can signal contradictory values relative to the represented organization. As outlined, a taking advantage perception may arise, such that clients may associate the luxury watch with overpriced products or services:

"I think that if I wore a Rolex most of my regular guests would probably notice as they also wear a Rolex. On the service side, I would almost forecast reduced sales based on the perception of taking advantage of people." [BSelby]

The luxury watch thereby enters the professional interaction as an interfering signal, which the client connects to the organizational offerings. Thus, a perception change may occur such that a client perceives to be "ripped off." As a consequence, the client may refrain from any present or future acquisitions with the organization. To avoid potential adverse effects and perception changes in the eyes of the client, forum members indicated to refrain from wearing a luxury watch in such a situation or switch to a less costly watch: "I feel the same way. On new clients where my Apple Watch. When at the office where my Rolex. I do feel self conscious." [woodbine].

General discussion and conclusions

Luxury watches are desirable items frequently appearing in organizational settings and professional interactions.Footnote65 As elements of employees' physical appearance, they can contribute to the social construction of an organizational image, conveying values to an internal or external audience.Footnote66 Thus far, organizational literature has not yet examined their role in the dynamics between employees' appearance in an organizational setting and the social construction of an organizational image.Footnote67 By drawing on the theoretical lens of gestalt theory and aesthetics of labour and branded labour, we respond to recent calls for more cross-disciplinary research into the organizational image concept and its related marketing concept of branding. Consequently, we adopt an organizational studies perspective informed by cross-disciplinary literature to discuss the dynamics involved in the social (re)construction of an organizational image in the form of the "organizational gestalt".Footnote68

Based on a netnographic study that was informed by a pre-study with luxury watch experts, we gained insights into the way in which the aesthetic appearance of an employee wearing a luxury watch in an organizational setting can contribute to the social (re)construction of the organizational image. Through expert interviews, we started to approach the luxury watch environment from multiple perspectives. From the expert descriptions, we learned that employees' display of luxury watches might be perceived differently in what can be termed luxury watch and non-luxury watch contexts. In settings where the daily business conduct is connected to luxury watches, front-line employees are perceived as manifestations of the organizational products, as described in branded labour literature.Footnote69 This descriptive aspect was underlined by netnographic data showing that certain professional service firms are associated with the display of luxury watches. Thus, luxury watches worn by employees in these settings are seen as an aesthetic and desirable attribute of the organizational environment, connecting the employee's appearance with the organizational image.Footnote70 In these situations, a value consistency between the employee and the organization is indicated. The employee's appearance featuring a luxury watch expresses the values associated with the organization.Footnote71 Thus, employee and organizational values are in harmony, and the "organizational gestalt" appears as a stable image.Footnote72

In these situations, the luxury watch can be seen as an important artifact that carries the organization's values.Footnote73 The watch is not an explicit artifact (not bearing a logo), but more an abstract indicator of organizational principles. In this case, the values relate to the previous and ongoing accomplishment, competence, and experience of an organization. Thus, when it comes to the external audience, the employee's luxury watch depicts here a positive image of the organization highlighting success and performance in the marketplace.Footnote74 For example, a portfolio manager wearing a luxury watch in a client meeting contributes to constructing a positive image, indicating that his personal success and organizational success are linked. In this way, the 'organizational gestalt' may appear as authentic and credible to an external audienceFootnote75:

"Maybe my "recklessness" will change if I lose a prospect or customer one day due to wearing a nice watch but as of now it hasn't given me any issues. If they notice it, I honestly don't think it will be a big deal, prospects and customers know that we are very successful because we make our customers successful." [Gus2]

As indicated by the comment, the watch thereby forms part of an employee's personality, and the distinction between the organization and employee's image becomes blurry.Footnote76 Accordingly, the netnographic data illustrate that employees use the luxury watch in a very self-centred manner in organizational contexts. In this regard, the watch serves to express the personal identity and attract and manage the demand for their own "personal brand" or personal image.Footnote77 Thus, the employee conveys an image to the external and internal audience with individual values attached.

Our findings show that an internal audience may approach the employee's appearance with indifference beyond positive perceptions. However, these perceptions may be subject to change and can also lead to reservations. This connects to previous research in the aesthetics of labour literature, in which elements of the employee's appearance have been associated with potential value conflicts.Footnote78 A luxury watch can communicate contradictory values from an inside perspective, disturbing the relationship between the employee and the organization. Thus, in light of an internal audience, the individual employee's personal image can conflict with the organizational image.Footnote79 As a result, a value inconsistency may arise, and the individual may appear less credible and face potential drawbacks:

"I also used to work with people who were very frugal and if I wore a Rolex all the time they would say I would never need a raise since I can afford a Rolex." [Stelyos]

As outlined by aesthetics of labour literature, such drawbacks may even prevent an individual from becoming part of an organization, as the aesthetic appearance may be perceived as unfitting for the professional setting and the contact with clientsFootnote80:

"Wear your Rolex on your interviews. It would be way more uncomfortable if they didn't see it until after you started a new position. At that point they'll probably just assume it's a new purchase and bad feelings could result around the office if they think you bought it after the job offer. Certainly would make some bosses feel like maybe they paid you too much. [904VT]

One can argue that in such a situation, a dissonance between the employee's personal image and the organizational 'organizational gestalt' arises, such that the values the employee projects differ from the organizational values.Footnote81 From an internal perspective, such a conflict between the personal image and the organizational image may come with disadvantages for the individual employee displaying the watch. However, from an outside perspective, it may also influence the overall organization in terms of the social construction of the corporate image in the eye of an external audience.

Theorizing gestalt-switch: a reconstruction of the organizational image

By conceptualizing the organizational image from a gestalt perspective, we offer a contribution to existing organizational literature.Footnote82 As shown above, a front-line employee's appearance can successfully contribute to conveying an organizational image and organizational values to an external audience, such as consumers and the wider public. We argue (see the first part of ) that in this situation, the personal image of the employee is in line with the organizational image, such that an external audience perceives the "gestalt" of the organization as a single entity.Footnote83 Thus, a consistency or harmony of values between the front-line employee and the organization exists. In other words, the employee's appearance is aligned with the organization's image, forming an authentic and credible 'organizational gestalt' conveyed to the external audience.Footnote84

Figure 1 The "organizational gestalt-switch" and Wittgenstein'sFootnote98 original duck-rabbit drawing.

However, a perception changeFootnote85 may arise when a front-line employee's appearance contradicts the image and underlying values that the organization embodies and projects to the outside (as depicted in the second part of ). In such a case, a value inconsistency between the employee and the organization arises. This means that the employee's physical appearance is not in line with the organizational values, and an external audience perceives the "gestalt" of the organization as irritated or scattered: a gestalt-switch arises.

A core theme discussed in gestalt theory is the "gestalt switch or shift," which is often illustrated by Wittgenstein's duck-rabbit drawing.Footnote86 Among experimental psychologists and philosophers, the duck-rabbit analogy is known as an illustration of the fundamentally interpretive human perception.Footnote87 The drawing can be seen as a duck or as a rabbit, yet not as both at the same time. Whereas the drawing remains the same, the 'gestalt-switch' is attributed to a change in perception, "when one first experiences an image or entity in one way and then in a quite different way".Footnote88 Thus, an organization's gestalt may appear stable and positive for an external audience. However, a luxury watch worn by an employee may trigger a value inconsistency. This suggests that a gestalt-switch occurs when a previously stable image of an organization undergoes a conversion due to a front-line employee having a look that appears to conflict with the established aesthetic, organizational representations.Footnote89 In conclusion, and to summarize the above discussion on an organizational image's social construction, we define the "organizational gestalt": as a dynamic projection of organizational values informed and conveyed by aesthetic, organizational representations (in this study: employees' wristwatches).

Against this background, both organizations and employees need to watch for potential value inconsistencies that may trigger a gestalt switch. Consequently, as an organization or front-line employee, it will be difficult to win back customer confidence. Like a scientific paradigm shift, the previously favourable image of the organization and its representative is reconstructed to an unfavourable one.Footnote90 A duck turns into a rabbit. Once a favourable gestalt has switched to a "new" unfavourable one, it may be difficult to turn it back, as trust and credibility have to be regained.Footnote91

Outlook, limitations, and future research

The workplace is crucial when it comes to the formation of an organizational image. In this social setting, employees' physical appearance increasingly moves centre stage, as a crucial aesthetic expression of organizational values. Focusing on the role of luxury watches worn at work, we followed-up on the social (re)construction of an organizational image in light of an internal and external audience. We thereby built on a qualitative approach involving pre-study expert interviews and netnographic data to gain insights into the dynamics between employees' appearance in the workplace and the formation of an organizational image. In light of the findings and the cross-disciplinary research that we drew on (gestalt theory, aesthetics of labour, and branded labour), we conceptualized the formation of an organizational gestalt and its restructuring – as a gestalt switch. Thus, this paper offers a new perspective to recent organizational literature engaging with the social processes involved in the organizational image construction and its marketing concept of branding.Footnote92 Not seeking to generalize, our findings may serve as a starting point for future research to further explore the role of other luxury items entering the workplace. A noteworthy example for departure might be the diamond ring of former French justice minister Rachida Dati, airbrushed in 2008 from Le Figaro's front page.Footnote93 Thus, future research may look into the degree to which luxury items as an aesthetic expression in the workplace can represent a risk factor for the organizational image, trust, and reputation.Footnote94 What implications might go along for the organizational reputation and value when individual, organizational members flash luxuries? To what extent should an organization manage or control its organizational gestalt against the background of an internal and external audience?Footnote95

Given this study's exploratory nature, we drew on a qualitative study that is not without limitations. Pre-study interviews were conducted with a convenience sample of luxury watch experts. This approach was chosen to make a quick and profound dive into the topic but comes with the risk of respondents' bias and subjectivity. To counter this risk, we interviewed experts from diverse backgrounds and with long-term experience approaching the topic from multiple angles.Footnote96 Also, the netnographic data was limited to a sample from a U.S.-based luxury watch forum. Although representing one of the largest forums worldwide with forum members dispersed worldwide, forum comments tend to reflect the U.S. country settings. Thus, future research could go beyond this context and strive to compare and contrast insights from different settings. Additionally, future research may apply differing methodological approaches to look deeper into the gestalt-switch via, for example, social-psychology experimental research, ethnography, or in-depth content analysis of social media cases. Theoretically, future research may also take up other theories in light of potential value and power conflicts between organizations and their members and external audiences contributing to the construction of an organizational gestalt.Footnote97

Notes on contributors

Mario D. Schultz is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Ethics and Communication Law Center, at the Università della Svizzera italiana, Switzerland. His current research focuses on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Business Ethics in relation to digitalization and information and communication technology and the luxury watch industry.

Peter Seele is a Full Professor for Corporate Social Responsibility and Business Ethics at the Università della Svizzera italiana, Switzerland. His research interests lie in CSR and its communication, CSR reporting, CSR digitalization, sustainable development, ethics, and law.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.7 KB)Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mario D. Schultz

Mario D. Schultz is a Postdoctoral researcher Corporate Social Responsibility and Business Ethics, Ethics and Communication Law Center (ECLC), USI Università della Svizzera italiana, Black Building, Office 116 (Level 1), Via Buffi 13, 6900 Lugano. [email protected]

Peter Seele

Peter Seele is a Full Professor for Corporate Social Responsibility and Business Ethics, Ethics and Communication Law Center (ECLC), USI Università della Svizzera italiana, Black Building, Office 115 (Level 1), Via Buffi 13 CH-6900 Lugano. [email protected]

Notes

1 Berton, “Dress to Impress, UBS Tells Staff.”

2 Oakley, “Ticking Boxes: (Re)Constructing the Wristwatch as a Luxury Object.”

3 Krüger, Behav. Brand.; Bemmer, “Weniger Rolex Wagen.”

4 Bemmer, “Weniger Rolex Wagen.”

5 Bemmer.

6 Müller, “‘Brandspeak’: Metaphors and the Rhetorical Construction of Internal Branding”; Mumby, “Organizing beyond Organization: Branding, Discourse, and Communicative Capitalism”; Vallas and Cummins, “Personal Branding and Identity Norms in the Popular Business Press: Enterprise Culture in an Age of Precarity”; Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing”; Salzer‐Mörling and Strannegård, “Silence of the Brands.”

7 Salzer‐Mörling and Strannegård, “Silence of the Brands,” 226.

8 Hatch and Schultz, “Of Bricks and Brands: From Corporate to Enterprise Branding.”

9 Müller, “‘Brandspeak’: Metaphors and the Rhetorical Construction of Internal Branding.”

10 Biehl-Missal and Fitzek, “Hidden Heritage: A Gestalt Theoretical Approach to the Aesthetics of Management and Organisation”; Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations; Grondin, Psychology of Perception.

11 Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing”; Timming, “Aesthetic Labour.”

12 Bonacchi, “Some Preliminary Remarks about the Use of the Expression ‘Gestalt’ in the Scientific Debate,” 13.

13 Sádaba and Bernal, “History as Luxury Brand Enhancement.”

14 Eilan, “On the Paradox of Gestalt Switches: Wittgenstein’s Response to Kohler”; Schurz, Philosophy of Science; Ash, Gestalt Psychology in German Culture, 1890-1967. Holism and the Quest for Objectivity.

15 Hatch and Schultz, Taking Brand Initiative: How Companies Can Align Strategy, Culture, and Identity Through Corporate Branding; Schultz et al., Constructing Identity in and around Organizations.

16 Kärreman and Rylander, “Managing Meaning through Branding – the Case of a Consulting Firm”; Müller, “‘Brandspeak’: Metaphors and the Rhetorical Construction of Internal Branding”; Mumby, “Organizing beyond Organization: Branding, Discourse, and Communicative Capitalism”; Vallas and Cummins, “Personal Branding and Identity Norms in the Popular Business Press: Enterprise Culture in an Age of Precarity”; Bertilsson and Rennstam, “The Destructive Side of Branding: A Heuristic Model for Analyzing the Value of Branding Practice”; Willmott, “Creating ‘value’ beyond the Point of Production: Branding, Financialization and Market Capitalization.”

17 Kärreman and Rylander, “Managing Meaning through Branding – the Case of a Consulting Firm”; Mumby, “Organizing beyond Organization: Branding, Discourse, and Communicative Capitalism.”

18 Schultz et al., Constructing Identity in and around Organizations; Hatch and Schultz, Taking Brand Initiative: How Companies Can Align Strategy, Culture, and Identity Through Corporate Branding.

19 Schroeder, “The Cultural Codes of Branding.”

20 Hatch, “The Pragmatics of Branding: An Application of Dewey’s Theory of Aesthetic Expression.”

21 Kärreman and Rylander, “Managing Meaning through Branding – the Case of a Consulting Firm,” 104.

22 Kärreman and Rylander, 106.

23 “Silence of the Brands.”

24 Hatch and Schultz, Taking Brand Initiative: How Companies Can Align Strategy, Culture, and Identity Through Corporate Branding.

25 Biehl-Missal and Fitzek, “Hidden Heritage: A Gestalt Theoretical Approach to the Aesthetics of Management and Organisation”; Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations; Grondin, Psychology of Perception; Wertheimer, On Perceived Motion and Figural Organization; Ellis, A Source Book Of Gestalt Psychology; Wertheimer, “Untersuchungen Zur Lehre von Der Gestalt.”

26 Biehl-Missal and Fitzek, “Hidden Heritage: A Gestalt Theoretical Approach to the Aesthetics of Management and Organisation.”

27 Grondin, Psychology of Perception, 89.

28 “Some Preliminary Remarks about the Use of the Expression ‘Gestalt’ in the Scientific Debate,” 13.

29 Biehl-Missal and Fitzek, “Hidden Heritage: A Gestalt Theoretical Approach to the Aesthetics of Management and Organisation”; Timming et al., “What Do You Think of My Ink? Assessing the Effects of Body Art on Employment Chances.”

30 Salzer‐Mörling and Strannegård, “Silence of the Brands.”

31 Pettinger, “Brand Culture and Branded Workers: Service Work and Aesthetic Labour in Fashion Retail”; Sirianni et al., “Branded Service Encounters: Strategically Aligning Employee Behavior with the Brand Positioning”; Karlsson, “Looking Good and Sounding Right: Aesthetic Labour”; Warhurst et al., “Aesthetic Labour in Interactive Service Work: Some Case Study Evidence from the ‘new’ Glasgow”; Witz, Warhurst, and Nickson, “The Labour of Aesthetics and the Aesthetics of Organization”; Warhurst and Nickson, “Employee Experience of Aesthetic Labour in Retail and Hospitality”; French, Mortensen, and Timming, “Are Tattoos Associated with Employment and Wage Discrimination? Analyzing the Relationships between Body Art and Labor Market Outcomes”; Timming, “Aesthetic Labour”; Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing.”

32 Timming, “Aesthetic Labour”; Zeithaml, Bitner, and Gremler, Services Marketing: Integrating Customer Focus Across the Firm.

33 French, Mortensen, and Timming, “Are Tattoos Associated with Employment and Wage Discrimination? Analyzing the Relationships between Body Art and Labor Market Outcomes”; Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing.”

34 Karlsson, “Looking Good and Sounding Right: Aesthetic Labour.”

35 Woodford, “Body Art and Its Impact on Employment Selection Decisions: Is There a Bias towards Candidates with Visible Tattoos?”; Timming et al., “What Do You Think of My Ink? Assessing the Effects of Body Art on Employment Chances.”

36 Woodford, “Body Art and Its Impact on Employment Selection Decisions: Is There a Bias towards Candidates with Visible Tattoos?”; French, Mortensen, and Timming, “Are Tattoos Associated with Employment and Wage Discrimination? Analyzing the Relationships between Body Art and Labor Market Outcomes.”

37 Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing,” 1042.

38 Nickson et al., “The Importance of Being Aesthetic: Work, Employment and Service Organization”; Sádaba and Bernal, “History as Luxury Brand Enhancement.”

39 Sirianni et al., “Branded Service Encounters: Strategically Aligning Employee Behavior with the Brand Positioning”; Liljander and Strandvik, “The Nature of Customer Relationships in Services, Advances in Service Marketing and Management.”

40 see, e.g., French, Mortensen, and Timming, “Are Tattoos Associated with Employment and Wage Discrimination? Analyzing the Relationships between Body Art and Labor Market Outcomes.”

41 Vigneron and Johnson, “Measuring Perceptions of Brand Luxury”; Amatulli and Guido, “Externalised vs. Internalised Consumption of Luxury Goods: Propositions and Implications for Luxury Retail Marketing”; Truong and McColl, “Intrinsic Motivations, Self-Esteem, and Luxury Goods Consumption”; Oakley, “Ticking Boxes: (Re)Constructing the Wristwatch as a Luxury Object”; Nickel, “Haute Philanthropy: Luxury, Benevolence, and Value.”

42 Duberley et al., “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend …? Examining Gender and Careers in the Jewellery Industry.”

43 Why Women Wear What They Wear.

44 van den Berg and Arts, “Who Can Wear Flip-Flops to Work? Ethnographic Vignettes on Aesthetic Labour in Precarity”; Entwistle and Mears, “Gender on Display: Peformativity in Fashion Modelling”; Lee, “Distinction by Indistinction: Luxury, Stealth, Minimalist Fashion”; Nickel, “Haute Philanthropy: Luxury, Benevolence, and Value.”

45 Sirianni et al., “Branded Service Encounters: Strategically Aligning Employee Behavior with the Brand Positioning”; Liljander and Strandvik, “The Nature of Customer Relationships in Services, Advances in Service Marketing and Management.”; Grandy and Mavin, “Occupational Image, Organizational Image and Identity in Dirty Work: Intersections of Organizational Efforts and Media Accounts”; Müller, “‘Brandspeak’: Metaphors and the Rhetorical Construction of Internal Branding.”

46 Salzer‐Mörling and Strannegård, “Silence of the Brands”; Sádaba and Bernal, “History as Luxury Brand Enhancement.”

47 Swedberg, “Before Theory Comes Theorizing or How to Make Social Science More Interesting.”

48 Kozinets, Netnography: The Essential Guide to Qualitative Social Media Research; Kozinets, Netnography: Doing Ethnographic Research Online; Leavy, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin and Lincoln, The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research; Cova, Pace, and Skålén, “Marketing with Working Consumers: The Case of a Carmaker and Its Brand Community.”

49 Sharma, Ahuja, and Alavi, “The Future Scope of Netnography and Social Network Analysis in the Field of Marketing.”

50 Swedberg, “Before Theory Comes Theorizing or How to Make Social Science More Interesting.”

51 Kozinets, “The Field behind the Screen: Using Netnography for Marketing Research in Online Communities”; Kozinets, Netnography: Doing Ethnographic Research Online.

52 de Lassus and Anido Freire, “Access to the Luxury Brand Myth in Pop-up Stores: A Netnographic and Semiotic Analysis”; Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing.”

53 see, e.g., Swedberg, “Before Theory Comes Theorizing or How to Make Social Science More Interesting.”

54 Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry FH, “Contact Details.”

55 see supplementary file for peer review

56 Saldaña, The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers.

57 see, e.g., Cutcher and Achtel, “‘Doing the Brand’: Aesthetic Labour as Situated, Relational Performance in Fashion Retail”; Nickson et al., “The Importance of Being Aesthetic: Work, Employment and Service Organization.”

58 Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing”; see, e.g., French, Mortensen, and Timming, “Are Tattoos Associated with Employment and Wage Discrimination? Analyzing the Relationships between Body Art and Labor Market Outcomes.”

59 see, e.g., Boyes, “Now You See It, Now You Don’t: It’s the Vanishing Rolex Trick; Europe” about Klaus Kleinfeld former CEO of Siemens; and Schwirtz, “$30,000 Watch Vanishes Up Church Leader’s Sleeve” about Patriarch Kirill, as the leader of the Russian Orthodox Church.

60 Kozinets, Netnography: Doing Ethnographic Research Online; Kozinets, Netnography: The Essential Guide to Qualitative Social Media Research.

61 Sádaba and Bernal, “History as Luxury Brand Enhancement.”

62 Kozinets, Dolbec, and Earley, “Netnographic Analysis: Understanding Culture Through Social Media Data.”

63 Colquitt, “On the Dimensionality of Organizational Justice: A Construct Validation of a Measure.”; Saldaña, The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers.

64 see supplementary file for peer review

65 Vigneron and Johnson, “Measuring Perceptions of Brand Luxury”; Amatulli and Guido, “Externalised vs. Internalised Consumption of Luxury Goods: Propositions and Implications for Luxury Retail Marketing”; Truong and McColl, “Intrinsic Motivations, Self-Esteem, and Luxury Goods Consumption”; Oakley, “Ticking Boxes: (Re)Constructing the Wristwatch as a Luxury Object.”

66 Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing”; Lee, “Distinction by Indistinction: Luxury, Stealth, Minimalist Fashion.”

67 Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing”; Timming, “Aesthetic Labour”; Müller, “‘Brandspeak’: Metaphors and the Rhetorical Construction of Internal Branding”; Grandy and Mavin, “Occupational Image, Organizational Image and Identity in Dirty Work: Intersections of Organizational Efforts and Media Accounts”; Kärreman and Rylander, “Managing Meaning through Branding – the Case of a Consulting Firm”; Hatch and Schultz, “Of Bricks and Brands: From Corporate to Enterprise Branding.”

68 Biehl-Missal and Fitzek, “Hidden Heritage: A Gestalt Theoretical Approach to the Aesthetics of Management and Organisation”; Kärreman and Rylander, “Managing Meaning through Branding – the Case of a Consulting Firm.”

69 Nickson et al., “The Importance of Being Aesthetic: Work, Employment and Service Organization”; Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing.”

70 Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing”; French, Mortensen, and Timming, “Are Tattoos Associated with Employment and Wage Discrimination? Analyzing the Relationships between Body Art and Labor Market Outcomes.”

71 Kärreman and Rylander, “Managing Meaning through Branding – the Case of a Consulting Firm.”

72 Morsing, “Corporate Moral Branding: Limits to Aligning Employees.”

73 Schultz, Hatch, and Ciccolella, “Brand Life in Symbols and Artifacts: The LEGO Company.”

74 Morsing, “Corporate Moral Branding: Limits to Aligning Employees.”

75 Schultz et al., Constructing Identity in and around Organizations.

76 Salzer‐Mörling and Strannegård, “Silence of the Brands.”

77 Vallas and Cummins, “Personal Branding and Identity Norms in the Popular Business Press: Enterprise Culture in an Age of Precarity.”

78 Woodford, “Body Art and Its Impact on Employment Selection Decisions: Is There a Bias towards Candidates with Visible Tattoos?”; Timming, “Body Art as Branded Labour: At the Intersection of Employee Selection and Relationship Marketing”; Timming et al., “What Do You Think of My Ink? Assessing the Effects of Body Art on Employment Chances”; Baumann, Timming, and Gollan, “Taboo Tattoos? A Study of the Gendered Effects of Body Art on Consumers’ Attitudes toward Visibly Tattooed Front Line Staff”; French, Mortensen, and Timming, “Are Tattoos Associated with Employment and Wage Discrimination? Analyzing the Relationships between Body Art and Labor Market Outcomes.”

79 Vallas and Cummins, “Personal Branding and Identity Norms in the Popular Business Press: Enterprise Culture in an Age of Precarity.”

80 Woodford, “Body Art and Its Impact on Employment Selection Decisions: Is There a Bias towards Candidates with Visible Tattoos?”; Timming et al., “What Do You Think of My Ink? Assessing the Effects of Body Art on Employment Chances.”

81 Morsing, “Corporate Moral Branding: Limits to Aligning Employees.”

82 Kärreman and Rylander, “Managing Meaning through Branding – the Case of a Consulting Firm”; Müller, “‘Brandspeak’: Metaphors and the Rhetorical Construction of Internal Branding”; Mumby, “Organizing beyond Organization: Branding, Discourse, and Communicative Capitalism”; Vallas and Cummins, “Personal Branding and Identity Norms in the Popular Business Press: Enterprise Culture in an Age of Precarity”; Witz, Warhurst, and Nickson, “The Labour of Aesthetics and the Aesthetics of Organization”; Willmott, “Creating ‘value’ beyond the Point of Production: Branding, Financialization and Market Capitalization”; Bertilsson and Rennstam, “The Destructive Side of Branding: A Heuristic Model for Analyzing the Value of Branding Practice.”

83 Bonacchi, “Some Preliminary Remarks about the Use of the Expression ‘Gestalt’ in the Scientific Debate.”

84 Schultz et al., Constructing Identity in and around Organizations; Biehl-Missal and Fitzek, “Hidden Heritage: A Gestalt Theoretical Approach to the Aesthetics of Management and Organisation.”

85 Eilan, “On the Paradox of Gestalt Switches: Wittgenstein’s Response to Kohler”; Schurz, Philosophy of Science; Ash, Gestalt Psychology in German Culture, 1890-1967. Holism and the Quest for Objectivity.

86 Schurz, Philosophy of Science; Ash, Gestalt Psychology in German Culture, 1890-1967. Holism and the Quest for Objectivity.

87 Eilan, “On the Paradox of Gestalt Switches: Wittgenstein’s Response to Kohler.”

88 Crowe, The Gestalt Shift in Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes Stories, 1.

89 Schroeder, “The Cultural Codes of Branding”; Hatch, “The Pragmatics of Branding: An Application of Dewey’s Theory of Aesthetic Expression”; Cutcher and Achtel, “‘Doing the Brand’: Aesthetic Labour as Situated, Relational Performance in Fashion Retail.”

90 McDonagh, “Attitude Changes and Paradigm Shifts: Social Psychological Foundations of the Kuhnian Thesis”; Crowe, The Gestalt Shift in Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes Stories.

91 see, e.g., Bachmann, Gillespie, and Priem, “Repairing Trust in Organizations and Institutions: Toward a Conceptual Framework”; Fuglsang and Jagd, “Making Sense of Institutional Trust in Organizations: Bridging Institutional Context and Trust.”

92 Kärreman and Rylander, “Managing Meaning through Branding – the Case of a Consulting Firm”; Witz, Warhurst, and Nickson, “The Labour of Aesthetics and the Aesthetics of Organization”; Vallas and Cummins, “Personal Branding and Identity Norms in the Popular Business Press: Enterprise Culture in an Age of Precarity.”

93 Samuel, “Photo of French Justice Minister Airbrushed to Play down Glamorous Image.”

94 Schultz et al., Constructing Identity in and around Organizations; Fuglsang and Jagd, “Making Sense of Institutional Trust in Organizations: Bridging Institutional Context and Trust”; Sádaba and Bernal, “History as Luxury Brand Enhancement.”

95 Müller, “‘Brandspeak’: Metaphors and the Rhetorical Construction of Internal Branding.”

96 Payne and Mansfield, “Relationships of Perceptions of Organizational Climate to Organizational Structure, Context, and Hierarchical Position.”

97 Mumby, “Organizing beyond Organization: Branding, Discourse, and Communicative Capitalism”; Bertilsson and Rennstam, “The Destructive Side of Branding: A Heuristic Model for Analyzing the Value of Branding Practice.”

98 Philosophical Investigations, 194.

Bibliography

- Amatulli, Cesare, and Gianluigi Guido. “Externalised vs. Internalised Consumption of Luxury Goods: Propositions and Implications for Luxury Retail Marketing.” International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 22, no. 2 (2012): 189–207. doi:10.1080/09593969.2011.652647.

- Ash, Mitchell G. Gestalt Psychology in German Culture, 1890–1967. Holism and the Quest for Objectivity. Vol. 15. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Bachmann, Reinhard, Nicole Gillespie, and Richard Priem. “Repairing Trust in Organizations and Institutions: Toward a Conceptual Framework.” Organization Studies 36, no. 9 (2015): 1123–1142. doi:10.1177/0170840615599334.

- Baumann, Chris, Andrew R. Timming, and Paul J. Gollan. “Taboo Tattoos? A Study of the Gendered Effects of Body Art on Consumers’ Attitudes toward Visibly Tattooed Front Line Staff.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 29, (2016): 31–39. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.11.005.

- Bemmer, Ariane. “Weniger Rolex Wagen.” Der Tagesspiegel. 2018. https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/zur-lage-der-spd-weniger-rolex-wagen/23601358.html

- Berg, Marguerite van den., and Josien Arts. “Who Can Wear Flip-Flops to Work? Ethnographic Vignettes on Aesthetic Labour in Precarity.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 22, no. 4 (2019): 452–467. doi:10.1177/1367549419861621.

- Bertilsson, Jon, and Jens Rennstam. “The Destructive Side of Branding: A Heuristic Model for Analyzing the Value of Branding Practice.” Organization 25, no. 2 (2018): 260–281. doi:10.1177/1350508417712431.

- Berton, Elena. “Dress to Impress, UBS Tells Staff.” The Wall Street Journal. 2010. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704694004576019783931381042

- Biehl-Missal, Brigitte, and Herbert Fitzek. “Hidden Heritage: A Gestalt Theoretical Approach to the Aesthetics of Management and Organisation.” Gestalt Theory 36, no. 3 (2014): 251–266. http://0-search.ebscohost.com.library.ucc.ie/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2014-43804-005&site=ehost-live%5Cn http://[email protected]%5Cn http://[email protected]

- Bonacchi, Silvia. “Some Preliminary Remarks about the Use of the Expression ‘Gestalt’ in the Scientific Debate.” Dialogue and Universalism 25, no. 4 (2015): 11–20. doi:10.5840/du201525481.

- Boyes, Roger. “Now You See It, Now You Don’t: It’s the Vanishing Rolex Trick; Europe.” The Times. 2005. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/now-you-see-it-now-you-dont-its-the-vanishing-rolex-trick-8nl286btb0m

- Colquitt, Jason A. “On the Dimensionality of Organizational Justice: A Construct Validation of a Measure.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 86, no. 3 (2001): 386–400. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.386.

- Cova, Bernard, Stefano Pace, and Per Skålén. “Marketing with Working Consumers: The Case of a Carmaker and Its Brand Community.” Organization 22, no. 5 (2015): 682–701. doi:10.1177/1350508414566805.

- Crowe, Michael J. The Gestalt Shift in Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes Stories. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98291-5.

- Cutcher, Leanne, and Pamela Achtel. “Doing the Brand’: Aesthetic Labour as Situated, Relational Performance in Fashion Retail.” Work, Employment and Society 31, no. 4 (2017): 675–691. doi:10.1177/0950017016688610.

- Denzin, NORMAN K., and YVONNA S. Lincoln, eds. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2018.

- Duberley, Joanne, Marylyn Carrigan, Jennifer Ferreira, Carmela Bosangit. “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend …? Examining Gender and Careers in the Jewellery Industry.” Organization 24, no. 3 (2017): 355–376. doi:10.1177/1350508416687767.

- Eilan, Naomi. “On the Paradox of Gestalt Switches: Wittgenstein’s Response to Kohler.” Journal for the History of Analytical Philosophy 2, no. 3 (2013), 1–21. doi:10.15173/jhap.v2i3.21.

- Ellis, Willis D. A Source Book of Gestalt Psychology. Routledge, 2013. doi:10.4324/9781315009247.

- Entwistle, Joanne, and Ashley Mears. “Gender on Display: Peformativity in Fashion Modelling.” Cultural Sociology 7, no. 3 (2013): 320–335. doi:10.1177/1749975512457139.

- Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry FH. “Contact Details.” online document. London: Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry FH. 2019. https://www.fhs.swiss/eng/links.html

- French, Michael T., Karoline Mortensen, and Andrew R. Timming. “Are Tattoos Associated with Employment and Wage Discrimination? Analyzing the Relationships between Body Art and Labor Market Outcomes.” Human Relations 72, no. 5 (2019): 962–987. doi:10.1177/0018726718782597.

- Fuglsang, Lars, and Søren Jagd. “Making Sense of Institutional Trust in Organizations: Bridging Institutional Context and Trust.” Organization 22, no. 1 (2015): 23–39. doi:10.1177/1350508413496577.

- Grandy, Gina, and Sharon Mavin. “Occupational Image, Organizational Image and Identity in Dirty Work: Intersections of Organizational Efforts and Media Accounts.” Organization 19, no. 6 (2012): 765–786. doi:10.1177/1350508411422582.

- Grondin, Simon. Psychology of Perception. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31791-5.

- Hatch, Mary Jo. “The Pragmatics of Branding: An Application of Dewey’s Theory of Aesthetic Expression.” European Journal of Marketing 46, no. 7 (2012): 885–899. doi:10.1108/03090561211230043.

- Hatch, Mary Jo., and Majken Schultz. “Of Bricks and Brands: From Corporate to Enterprise Branding.” Organizational Dynamics 38, no. 2 (2009): 117–130. doi:10.1016/j.orgdyn.2009.02.008.

- Hatch, Mary Jo., and Majken Schultz. Taking Brand initiative: How companies can align strategy, culture, and identity through corporate branding. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, a Wiley Impring, 2008.

- Karlsson, Jan Ch. “Looking Good and Sounding Right: Aesthetic Labour.” Economic and Industrial Democracy 33, no. 1 (2012): 51–64. doi:10.1177/0143831X11428838.

- Kärreman, Dan, and Anna Rylander. “Managing Meaning through Branding – the Case of a Consulting Firm.” Organization Studies 29, no. 1 (2008): 103–125. doi:10.1177/0170840607084573.

- Kozinets, Robert V. “The Field behind the Screen: Using Netnography for Marketing Research in Online Communities.” Journal of Marketing Research 39, no. 1 (2002): 61–72. doi:10.1509/jmkr.39.1.61.18935.

- Kozinets, Robert V. Netnography: Doing Ethnographic Research Online. London: SAGE Publications, 2010. doi:10.2501/S026504871020118X.

- Kozinets, Robert V. Netnography: The Essential Guide to Qualitative Social Media Research. Society. London: Sage Publications Ltd, 2019.

- Kozinets, Robert V., Pierre-Yann Dolbec, and Amanda Earley. “Netnographic Analysis: Understanding Culture through Social Media Data.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, 262–276. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2010. doi:10.4135/9781446282243.n18.

- Krüger, Doris. “Behavioral Branding.” In Behavioral Branding, edited by Torsten Tomczak, Franz-Rudolf Esch, Joachim Kernstock, and Andreas Herrmann. Wiesbaden: Gabler Verlag, 2012. doi:10.1007/978-3-8349-7134-0.

- Lassus, Christel de, and N. Anido Freire. “Access to the Luxury Brand Myth in Pop-up Stores: A Netnographic and Semiotic Analysis.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 21, no. 1 (2014): 61–68. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.08.005.

- Leavy, Patricia, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199811755.001.0001.

- Lee, YeSeung. “Distinction by Indistinction: Luxury, Stealth, Minimalist Fashion.” Luxury 6, no. 3 (2019): 203–225. doi:10.1080/20511817.2021.1897265.

- Liljander, Veronica, and Tore Strandvik. “The Nature of Customer Relationships in Services, Advances in Service Marketing and Management.” Advances in Services Marketing and Management 4, (1995): 141–167.

- McDonagh, Eileen L. “Attitude Changes and Paradigm Shifts: Social Psychological Foundations of the Kuhnian Thesis.” Social Studies of Science 6, no. 1 (1976): 51–76. doi:10.1177/030631277600600103.

- Morsing, Mette. “Corporate Moral Branding: Limits to Aligning Employees.” Corporate Communications: An International Journal 11, no. 2 (2006): 97–108. doi:10.1108/13563280610661642.

- Müller, Monika. “Brandspeak’: Metaphors and the Rhetorical Construction of Internal Branding.” Organization 25, no. 1 (2018): 42–68. doi:10.1177/1350508417710831.

- Mumby, Dennis K. “Organizing beyond Organization: Branding, Discourse, and Communicative Capitalism.” Organization 23, no. 6 (2016): 884–907. doi:10.1177/1350508416631164.

- Nickel, Patricia Mooney. “Haute Philanthropy: Luxury, Benevolence, and Value.” Luxury 2, no. 2 (2015): 11–31. doi:10.1080/20511817.2015.1099338.

- Nickson, Dennis, Chris Warhurst, Anne Witz, and A. M. Cullen. “The Importance of Being Aesthetic: Work, Employment and Service Organization.” In Customer Service: Empowerment and Entrapment, edited by Andrew Sturdy, Irena Grugulis, and Hugh Willmott, 170–190. Sasingstoke, UK: Palgrave, 2001.

- Oakley, Peter. “Ticking Boxes: (Re)Constructing the Wristwatch as a Luxury Object.” Luxury 2, no. 1 (2015): 41–60. doi:10.1080/20511817.2015.11428564.

- Payne, Roy L., and Roger Mansfield. “Relationships of Perceptions of Organizational Climate to Organizational Structure, Context, and Hierarchical Position.” Administrative Science Quarterly 18, no. 4 (1973): 515. doi:10.2307/2392203.

- Pettinger, Lynne. “Brand Culture and Branded Workers: Service Work and Aesthetic Labour in Fashion Retail.” Consumption Markets & Culture 7, no. 2 (2004): 165–184. doi:10.1080/1025386042000246214.

- Sádaba, Teresa, and Pedro Mir Bernal. “History as Luxury Brand Enhancement.” Luxury 5, no. 3 (2018): 231–243. doi:10.1080/20511817.2018.1741169.

- Saldaña, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd, 2013.

- Salzer‐Mörling, Miriam, and Lars Strannegård. “Silence of the Brands.” European Journal of Marketing 38, no. 1/2 ( 2004): 224–238. doi:10.1108/03090560410511203.

- Samuel, Henry. “Photo of French Justice Minister Airbrushed to Play down Glamorous Image.” The Telegraph. 2008. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/3495242/Photo-of-French-justice-minister-airbrushed-to-play-down-glamorous-image.html

- Schroeder, Jonathan E. “The Cultural Codes of Branding.” Marketing Theory 9, no. 1 (2009): 123–126. doi:10.1177/1470593108100067.

- Schultz, Majken, Mary Jo Hatch, and Francesco Ciccolella. “Brand Life in Symbols and Artifacts: The LEGO Company.” In Artifacts and Organizations: Beyond mere Symbolism, edited by Anat Rafaeli and Michael G. Pratt, 141–160. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2006.

- Schultz, Majken, Steve Maguire, Ann Langley, and Haridimos Tsoukas. Constructing Identity in and Around Organizations. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Schurz, Gerhard. Philosophy of Science: A Unified Approach. Routledge, 2013. doi:10.4324/9780203366271.

- Schwirtz, Michael. “$30,000 Watch Vanishes Up Church Leader’s Sleeve.” New York, NY: New York Times. 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/06/world/europe/in-russia-a-watch-vanishes-up-orthodox-leaders-sleeve.html