?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The enormous demographic and economic disturbances caused by World War I forced participating governments to drastically restrict market freedoms. In particular, the state began intervening actively in the housing market. For the first time, Ukraine, as a part of the then Russian Empire, implemented rent controls and protection of tenants from eviction. This paper concentrates on interventions in the rental housing market of Right-Bank Ukraine during the war. It identifies the factors triggering intervention in the landlord-tenant relationship; analyses changes in the housing legislation; and assesses the effectiveness of the regulations.

World War I (WWI) played a very important role in shaping modern socio-economic policy. In particular, WWI was a catalyst for state intervention in the rental housing market. One hundred years later, its effects remain salient. In modern industrialised countries, like Germany and the USA, rent control and tenant eviction protection remain actively used tools of government regulation. The history of these tools is well documented.Footnote1 However, despite the fact that Ukraine, as part of the Russian Empire, was one of the earliest countries to see housing policies implemented, its housing policy during WWI remains understudied.Footnote2 In Soviet historical literature, the housing market regulation of Right-Bank Ukraine is only briefly mentioned, exclusively in the context of the worsening living standards of the workers.Footnote3 Modern Ukrainian historians give somewhat more attention to urban housing issues. For instance, an everyday-life researcher, r Vil’shanska, considers the main reasons for housing shortages and dramatic rent increases during WWI and points out the compromise nature of the housing regulation in Ukraine in 1918.Footnote4 One study looking at the impact of WWI on the welfare of Ukraine’s population noted a substantial deterioration in housing conditions,Footnote5 while two other studies discuss governmental regulation of housing in 1917–1921, but only within the geographical limits of the Podol’skaya governorate.Footnote6 Vityuk investigates housing policies undertaken at the municipal level and concludes that they were unable to solve the housing issue due to a sharp increase of the urban population in the governorate, which also led to mass unemployment. Gerasimov argues that the housing act of 1918 in Ukraine led to a real freeze of rents, because the allowed rent increases fell short of the overall prices increases.

Our aim is to analyse the origins and development of the state’s intervention in the rental housing market (rent controls and tenant protection) in Right-Bank Ukraine, one of the regions of the Russian Empire. The paper examines the factors that triggered state intervention and reflects on its effectiveness.

The Housing Market Before WWI

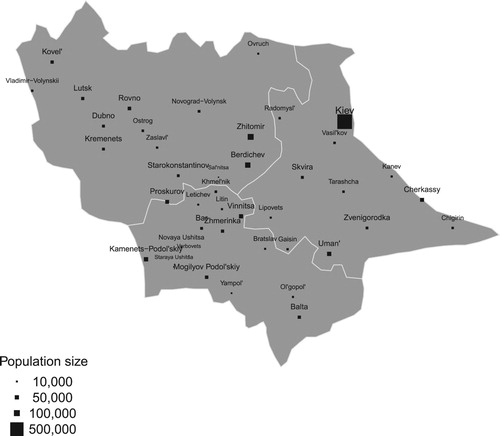

Right-Bank Ukraine is one of the historical regions of Ukraine. As an integral regional unit, it started taking shape in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. When it became part of the Russian Empire, Right-Bank Ukraine bore the official name of the South-West region and occupied the territory of three Ukrainian governorates: Kievskaya, Podol’skaya, and Volynskaya (see ). In maps of modern Ukraine, these are the territories of Cherkasskaya, Khmelnitskaya, Kievskaya, Rovenskaya, Vinnitskaya, Volynskaya, and Zhitomirskaya plus parts of the Odesskaya and Ternopolskaya oblasts.Footnote7 In 1914, the total population of Right-Bank Ukraine was 11.5 million. From the beginning of the twentieth century through WWI, Right-Bank Ukraine led the Empire in terms of urbanisation rates, urbanising even faster than the most economically developed regions of the Russian Empire. Between 1897 and 1914, the urban population of the region increased by 70%, while the Empire’s average was 58%. The biggest cities in Right-Bank Ukraine – with populations of 50,000 or more – were (in descending order): Kiev, Zhitomir, Berdichev, Vinnitsa, and Kamenets-Podol’skiy; see , where the size of squares denoting the cities is proportional to their 1910 population. However, despite its rapidly growing urban population, Right-Bank Ukraine remained, overall, a mainly agricultural region.Footnote8

The rapid urban population increase led to a strong increase of demand for housing in urban areas. This stimulated building activity. Just prior to WWI, residential construction in Right-Bank Ukraine was very profitable, with the construction frenzy leading to a noticeable increase in prices for construction materials and labour. In the central parts of the city, small houses were demolished and in their place multi-story buildings were erected, while additional stories were built on top of existing houses in some cases.Footnote9 Landlords rented out the newly built apartments.Footnote10 However, the growing housing supply in Right-Bank Ukraine’s cities could not keep pace with its rapidly expanding urban population. Therefore, no decrease in the rents for apartments and rooms was observed. Thus, the situation of tenants in urban settlements remained rather precarious, with a large proportion of their incomes spent on rent. For example, in 1912, the share of housing expenditure in total expenses of Kiev’s workers varied between 3% and 22%.Footnote11 The lowest share was observed in the case of single people, who rented beds, while the highest share was paid by those renting entire apartments. Among singles, the income share for those renting apartments was just 11.3%, whereas among the families it was 67%. By contrast, almost half of the singles (44.8%) lived squeezed in corners, renting beds or even sharing beds. Demand exceeded supply and a lack of laws protecting tenants made them defenseless in the face of the landlords. Some landlords prohibited the tenants from having children. The “guilty” families were evicted. Not wanting to lose shelter, poor tenants acted desperately; one, for example, sent his new born baby daughter immediately to a village where his relatives lived.Footnote12

The Housing Crisis During the War

The entry of the Russian Empire in WWI changed Ukrainian cities significantly. The population exploded with city-dwellers returning from their summer residences and rural populations arriving in order to comply with the military draft registrations.Footnote13 For example, the substantial inflow of people in Zhitomir instantly led to rent increases.Footnote14 In the fall of 1914, a mass eviction of the large and socially unprotected group of reservists’ families from rental dwellings started. The tensest situation was in Kiev, where newspapers reported cases of women who were unable to pay their rent after their husbands were drafted; these women were evicted from their dwellings.Footnote15 Furthermore, martial law introduced on July 30, 1914, in the Kievskaya, Podol’skaya, and Volynskaya governoratesFootnote16 led to a further reduction of housing vacancies. In the urban settlements, the requisitions of dwellings for the military started. Not only were residential buildings requisitioned, but also schools, thus creating the need to find new facilities for dormitories and classrooms. Moreover, during the war, offices were needed for the many newly established foundations, committees, military hospitals, and other organisations.Footnote17

There was nothing to compensate for a reduction in residential space in Right-Bank Ukraine cities. With the outbreak of WWI, housing construction virtually ceased.Footnote18 This was caused by the impossibility of obtaining credit, strong increases in the wages of construction workers and materials, as well as a lack of available space for transporting materials on trains; most were reserved for military purposes.Footnote19 The first wartime construction season, starting in the spring of 1915, saw limited action: only public buildings were erected, all private construction ceased.Footnote20 During the first months of 1915, the output of the building materials industry significantly dropped after 50% of its workers were mobilized.Footnote21 All the materials needed for construction became scarce and, hence, very expensive.Footnote22 Then, in 1916, in the middle of the housing crisis in the big cities of Right-Bank Ukraine, the construction market collapsed. Wages increased very rapidly. For example, between January and December 1916, building costs more than doubled in Vinnitsa.Footnote23 In 1916, the city board of Kiev decided to stop all construction works.Footnote24

Another factor that significantly contributed to the aggravation of the housing issue was an inflow of refugees from the territories occupied by the enemy and located near the front line. In August 1914, after Kamenets-Podol’sk was taken by the Austro-Hungarian army, an eastward evacuation of its public establishments started, as most civil servants, together with their families, headed to Vinnitsa.Footnote25 The military catastrophe suffered by the Russian army in the summer of 1915, in turn, caused substantial movements of people toward rear governorates.Footnote26 The refugees tried to settle down in the big cities, hoping that jobs and housing would be much easier to find there.Footnote27

All these factors led to increasing rents and deteriorating relationships between landlords and tenants. In fall 1915, Vinnitsa and Zhitomir experienced the first symptoms of a full-fledged housing crisis. In September 1915, a local newspaper wrote about daily increases in rents for apartments and hotel rooms.Footnote28 In 1915, in Kiev the housing issue was not so grave as in Vinnitsa and Zhitomir, although that summer the rents were already much higher than immediately before the outbreak of the war. For instance, a one-room apartment on the city outskirts could be rented for at least 240–250 rubles a year, whereas in peacetime the rent for a similar apartment in the city center did not exceed 100 rubles.Footnote29 In the fall of 1915, there was a temporary rent decrease, triggered by the flight of people who feared that Kiev would be occupied by the enemy. In addition, thanks to a hasty evacuation of the local government bodies, including Kiev University, the city had a break in the housing crisis.

In August 1916, the housing issue in the large cities of the region was again a major issue. In Zhitomir, the local press noticed a complete absence of vacant lodgings and extreme overcrowding in the hotels. The real-estate agents asserted that “the housing issue was never so tight before”.Footnote30 During 1917, the situation remained unchanged. However, the period between March and December 1918 was peculiar for the cities of Right-Bank Ukraine. It was the period of the fastest growth. First, the demobilised soldiers returned home. Secondly, the presence in the cities of the garrisons of the Central Powers made them “safe harbors.” In the countryside, the peasants frequently revolted, meaning that the big landowners and many non-peasants were fleeing to the cities trying to escape the peasants’ anger and the deteriorating safety situation. Thirdly, thousands of refugees flooded the Hetmanate state.Footnote31 Some left Bessarabia, which was occupied by Romania, others ran away from the Russian regions under Bolshevik rule, especially from Moscow and Petrograd. These factors together with high inflation intensified the housing crisis further. This crisis affected urban settlements in the region. According to one contemporary, “all vacant lodgings were completely filled and many city-dwellers were in an unbearable situation”.Footnote32 Kiev was suffocating from overpopulation.Footnote33 Mogilyov-Podol’skyi was full of refugees from Bessarabia and surrounding villages.Footnote34

Reaction of the State to the Housing Crisis

The state reacted to the increasing housing problems with prohibitive-protective measures. summarises the legal acts that were in force in Right-Bank Ukraine in 1915–1921. The first column reports the date of the act, as indicated in the document. The second column contains the full title of the act both in English translation and in the original language. Column 3 characterises the sphere of application of the legal act: its subject (e.g., apartments and rooms); settlements, which were subject to the regulations; and exceptions from the regulations. Column 4 describes the provisions concerning rent controls: setting, which stands for the rules setting the upper bound on the rent and updating, which denotes the rules regulating the legally allowed rent increases. Column 5 sums up the provisions on protection of tenants from eviction: prolongation – possibilities to automatically prolong the contract when it is over; and termination reasons – possibilities to revoke the contract ahead of schedule by the landlord. Column 6 lists the bodies to which the legal act delegated the power to (extrajudicially) settle the conflicts between the landlords and tenants. The last column shows the period of validity of the act.

Table 1. Housing legislation that was in force in Right-Bank Ukraine, 1915–1921.

The rent increases that accelerated in the middle of 1915 due to large inflows of refugees caused discontent. Similar to the heads of many other regions of the Russian Empire,Footnote35 the commander-in-chief of the Kievskiy military district decided to restrict the rent increases and issued a compulsory ordinance (obiazatel’noe postanovlenie) on August 13 (July 30), 1915.Footnote36 It prohibited increased rents for apartments, furnished chambers and hotel rooms in excess of the existing ones, except for those cases where rent increases could be justified by the expenses of improving the apartments.Footnote37 Later, the commander-in-chief of Kievsky military district V. I. Trotsky issued two more compulsory ordinances on housing regulations. The compulsory ordinance of September 23 (10), 1915 covered all the towns and boroughs (mestechki) of Kievskaya governorate, except the city of Kiev.Footnote38 The subject of regulation was the same as in the previous compulsory ordinance. There were two novelties in the new compulsory ordinance: written contracts concluded before publication of the compulsory ordinance were excluded from its sphere of application; and the reference data, to which the maximum rent was linked, was specified and set to August 14 (1), 1915. In the previous compulsory ordinance, its publication date was set as the reference one.

The compulsory ordinance of April 21 (8), 1916 was much more elaborate than its predecessors.Footnote39 It contained many innovations. An additional restriction on the sphere of application was introduced: only premises built prior to August 12 (July 30), 1914, were now subject to the regulations and the reference date was shifted from 14 August–28 December 1915. In addition, to the rent level at the reference date 5% could be added. Furthermore, advance paymentsFootnote40 of rent were limited to one month not only to the families of the military, but also to the tenants renting corners and beds and an automatic prolongation of the rental contract after its expiry was introduced, provided that the tenant diligently paid rent. Finally, the termination of existing contracts was confined to two cases: if the housing was urgently needed by the landlord or principal tenant, which should be incontestably proven; or if the behaviour, life style and occupation of tenants required their eviction.

This compulsory ordinance had significantly enlarged the sphere of regulation by extending it not only to residential but also to non-residential premises. At the same time, its sphere was confined only to the premises built prior to WWI. However, taking into account that during the war construction almost ceased, this relaxation was relevant for very few dwellings. The main purpose of this exception was to avoid reducing incentives for new construction.Footnote41 Moreover, the compulsory ordinance covered all settlements of the Kievsky military district. The shift in the reference date practically implied an increase in the allowed rent level. A very important innovation was an introduction of tenant protection from eviction. Previously, only the rent level was controlled, while the eviction of tenants was a free decision of the landlords. It is clear that under such conditions, the landlords could easily get rid of undesirable tenants. Now, eviction, at least on paper, was made much more difficult. It should be noted that the first condition was formulated clearly and strictly, while the second one was very vague and allowed a wide interpretation. The authors of the compulsory ordinance imagined perhaps noisy and reckless tenants destroying their dwelling and making money in occupations such as prostitution. In practice, however, the landlords could interpret this provision in a radically different way.

According to the legislation of the Russian Empire (provisions on the administration of the military districts of 1864), the commander of a military district had control over all military forces in the district, both regular and irregular. He was responsible for quartering, transportation, and provision of the troops as well as for maintaining the discipline of the military men, protecting their health, military training, inspecting the troops, etc. However, during the war, the prerogatives of the commander of the military district were substantially extended. In particular, the commander of the district in a defensive situation had to “take a special care of the protection of security and order in all the governorates and regions of the district”.Footnote42 Hence, settling the housing issue was a direct responsibility of the commander of the military district, since the last thing he wanted was an expansion of social conflicts due to an aggravation of the shortage of affordable housing.

A small part of Right-Bank Ukraine, namely the Baltskyi uyezd of Kievskiy governorate, a county with a centre in the town of Balta (see ), belonged to the Odesskiy military district. The military district had its own regulations on tenant protection, which until September 9, 1916, also covered Baltskiy uyezd. In particular, on September 4 (August 22), 1915, the commander-in-chief of Odesskiy military district general M. I. Ebelov issued a compulsory ordinance prohibiting rental increases in excess of those fixed in the contracts (both written and oral) concluded prior to the publication of the ordinance.Footnote43 On January 28 (15), 1916, general Ebelov issued another compulsory ordinance that froze the rental prices for hotel rooms and furnished chambers at the January 14 (1), 1915, levels.Footnote44

After multiple compulsory ordinances issued at the regional level, in the fall of 1916, finally, the central Russian government reacted to the growing housing issue. On September 9 (August 27), 1916 the Council of Ministers of the Russian Empire issued an act “On prohibition to increase the housing rents,”Footnote45 see . The act explicitly delineated the settlements subject to its regulations. Specifically, in Right-Bank Ukraine 41 such settlements were identified, that is, all towns that existed there at that time. It specified the subject of regulations: only dwellings, excluding the apartments for the wealthy. The rent was fixed at the pre-war level (1 August 1914) plus 10%. Rent could only be increased to compensate for growing expenditure on fuel, wages of yard-keepers and porters as well as in case of interior refurbishment. In addition, protection of tenants from eviction was introduced and an automatic prolongation of contracts was provided for. Contract termination ahead of time by the landlord was allowed in only three cases: if the tenant broke all the conditions of the contract; if the landlord needed the housing for his own use; or if the tenant infringed the conditions of co-habitation in the house. The expiry date was set for August 1919. Apparently, the war was supposed to end by then and then the housing market was expected to normalise.

Thus, the rent controls act of the Tsarist government was meant to mark huge progress in housing market regulation compared to the local compulsory ordinances, in particular, to those of the Kievskiy military district. It also specified the regulation mechanism. But did the 1916 act lead to stricter controls? To a large extent the answer is “no”. Firstly, compared to the compulsory ordinance of April 21 (8), 1916, it meant a relaxation through the exclusion of non-residential premises from regulations and through its focus on the specific segments of middle- and low-priced dwellings, which especially needed protective regulations and not on the entire market. Second, it softened regulations by extending the list of reasons a landlord could terminate rental contracts ahead of time, thus weakening the protection from eviction for tenants. How restrictive the provision allowing a 10% increase of rents compared to 1 August 1914 was, can only be determined by examining data on how rents in Right-Bank Ukraine increased between 1 August 1914 and 28 December 1915 and through 9 September 1916. Unfortunately, such data is not available.

On August 18 (5), 1917 the Provisional Government of Russia issued a decree “On establishing the maximum rents for apartments and other premises”.Footnote46 It became a model for almost all the subsequent rent control acts that were issued until 1920 on the territory of the former Russian Empire by the non-Bolshevik governments.

Compared to the act of 1916 the act of the Provisional Government of Russia introduced a number of changes. Firstly, the sphere of application was extended by including, along with private apartments, the lodgings belonging to public, charity, commercial and industrial establishments. The regulations were also extended to subletting and the premises in hotels and summer residences, if they were let for a short term, as well as in large pensions and hotels, were excluded from the sphere of application of the act. The upper bound for rent was raised to 15–100%, depending on the apartment tax classFootnote47 of the corresponding settlement and rent category of the dwelling and compensation of increasing costs for heating was introduced as an additional possibility to increase rent. However, the claim that the landlord needed the dwelling for his own use was excluded from the list of reasons allowing an early termination of contract by the landlord. Finally, as a body for extrajudicial settlement of conflicts between the landlords and tenants, arbitration councils (primiritel’nye zhilishchnye kamery) were set up, including representatives of both sides on A parity basis.

After the February 1917 Revolution, the Empire started to decompose. Regarding Right-Bank Ukraine, in 1918, there were several political regimes that partly coexisted and alternated on its territory. The Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR) from 22 January to 29 April 1918; the Hetmanate from 29 April to 14 December 1918; and the Directorate of the UPR from December 1918 to November 1920. On 2 November (October 20), 1918, the government of Hetman Skoropadsky issued the “Act on renting premises.”Footnote48 It was meant to replace the decree of the Provisional Government of Russia of August 18 (5), 1917. The innovations in the Hetman’s law included: the regulations were extended to all residential premises, regardless of the rent level; the upper bounds for legally admissible rent were raised from 15–100% to 50–100% as a function of the category of settlement and level of rent; and the list of reasons for contract termination was substantially extended. To the two reasons mentioned in the decree of the Provisional Government, another five were added: failure to pay rent; damage of premises; speculative use of the premises; absence from the rented premises for more than five months; and if the tenant was fired and his employment was related to the occupation of the dwelling (for example, if he was a yard-keeper).

On the one hand, the new law implied tougher regulations through extending its sphere of application. On the other hand, it meant weaker regulations, since it simplified the termination of contract by the landlord. Again, the upper bounds for rent established by the Hetman’s law cannot be unambiguously identified as liberalisation, because it is not known by how much the cost of living and of, in particular, housing increased in Ukraine between August 1917 and November 1918. It is likely that the Hetman’s law simply legalised the rent increase that occurred during that period. In addition, the Hetman’s law abolished housing arbitration councils in Ukraine. The cancellation of the housing arbitration councils by the government of Hetman P. P. Skoropadskiy was related to his aspiration to guarantee a clear division between the three branches of power: legislative, executive, and judicial. According to his opinion, only judicial power could settle all kinds of conflicts, including those related to housing. The arbitration councils duplicated the courts and were subject to a greater administrative pressure.

However, the Hetman’s law turned out to be very short-lived. Even in November 1918, it was suspendedFootnote49 and the rent controls act of the Provisional Government was reinstated. On 30 July 1919, the Directorate of the UPR prolonged the act on the territory that it controlled at that time (a small piece of Podol’skaya governorate) until 1 October 1919;Footnote50 for it was meant to expire on 1 August 1919. On 24 May 1920,Footnote51 the Directorate once again prolonged the act of the Provisional Government of Russia.Footnote52

Effectiveness of State Intervention

Unfortunately, no reliable statistical data on the rent dynamics during the period under consideration could be found. However, the available pieces of information point to substantial growth of rent between 1914 and 1918. For example, between 1914 and 1918, the average annual rent for a room rented by a single person were reported to have increased in Ukraine by 15 times: from 120 to 1800 rubles. During the same period, the price for staple foods increased by 20 times.Footnote53 This inflation, as in many other belligerent countries, was caused by enormous military expenditure financed through government debt. Thus, between 1914 and 1917, the government debt of Russia increased from 8.8 billion rubles to over 31 billion rubles.Footnote54 While prior to World War I, the currency emission was 0.3 billion rubles, by the fall 1917, it achieved 16.5 billion rubles.Footnote55 Between 1914 and 1917, the average worker’s nominal wage in the Russian Empire should have risen by more than 700%, for it to remain unchanged in real terms.Footnote56 In 1915 and 1916, real wages increased by 6.3 and 9.4% with respect to 1914. After the October Revolution, real wages in Ukraine plummeted: compared to 1913, in June 1918, the real wage of carpenters, locksmiths, painters and unskilled workers decreased by 2, 1.93, 1.7 and 1.76 times.Footnote57 In contrast to the workers, the civil servants did not experience any substantial growth in their nominal earnings. For example, in Podol’skaya governorate, the nominal wages of low-rank school employees increased from 30 rubles in 1913–125 in 1918, that is, by 4.2 times. However, due to a much stronger price increase their purchasing power decreased by almost 10 times.Footnote58 Thus, civil servants were hit by the consumer prices increases much harder than the workers. Housing rents contributed to the worsening of living standards, but their contribution was rather minor compared to that of other consumer expenses.

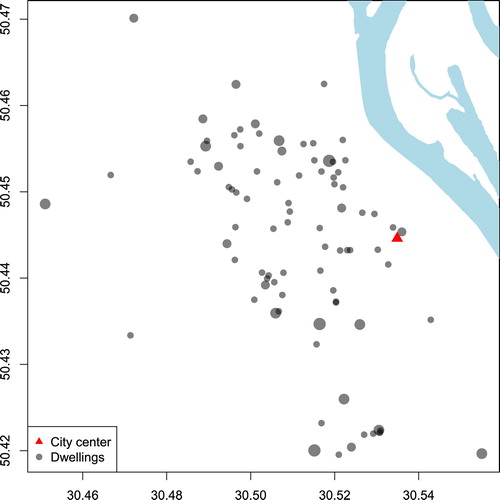

In addition, we collected more than 120 advertisements from the daily newspaper “Kievlyanin” that appeared in Kiev between 13 July 1864 and 16 December 1919. The announcements contain information on dwelling characteristics, such as: number of rooms, category (apartment or chamber), furniture, heating (central or not), electricity, balcony, bathroom, kitchen, convenience, date of publication of the announcement, and the address. They cover the period between 1913 and 1919. depicts the location of dwellings offered for rent in the newspaper announcements (grey circles) and the city center (red triangle). The size of grey circles reflects the number of announcements corresponding to the same address. The location of the city centre is computed as the average co-ordinates of: the administration of the general governor of Kievskaya, Podol'skaya, and Volynskaya governorates (Yekaterininskaya ulitsa 12); the administration of Kievskaya governorate (Yekaterininskaya ulitsa 10); and the secretariat of the governor of Kievskaya governorate (Institutskaya ulitsa 22). Using these geographic coordinates the distances from dwellings to the city centre are calculated.

Figure 3. Map of dwellings offered for rent in Kiev, 1913–1919. Sources: newspaper “Kievlyanin” and own calculations.

Based on these data we estimated a linear regression in order to obtain hedonic (that is, quality-adjusted) housing rents:where pi is the monthly rent for i-th apartment or chamber in rubles; Xi is the vector of structural and locational characteristics of the housing;

are the time dummies, while the parameters are α, β, and γ’s; and ui is the error term. The time dummies are defined as year. Thus, each γt corresponds to the change of rent in the respective year t.

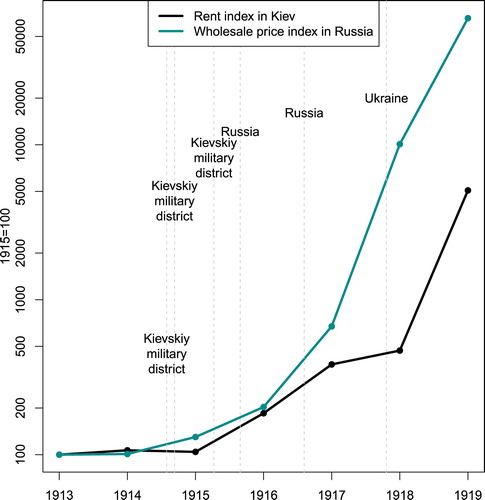

Then, for each year, we computed the hedonic rent for a three-room apartment with kitchen, but without electricity, balcony, convenience, and central heating located 2.27 km from the city center. The evolution of the resulting quality-adjusted housing rent is shown in . For comparison, an index of wholesale prices for Russia is displayed.Footnote59 The latter index is used because it is the only price index for the former Russian Empire that covers the period of interest and since no consumer price index is available for Ukraine for that period. Both indices have 1913 as their basis year. In addition, dashed lines reflect the dates of rent control ordinances and laws. It can be seen that after the beginning of the war, rents started to decline due to a large outflow of males to the front. Similar trends are observed, for example, in BerlinFootnote60 and in St. Petersburg (work in progress of one of the authors of this paper). However, in 1915, rents began to increase. Until 1917, they were growing at the same rate as wholesale prices. After 1917, the increase of both wholesale prices and rents became explosive. However, wholesale prices substantially outpaced rents: wholesale prices increased from 1913 through 1919 by 65,600%, while the rents grew by only 5076%. Such a huge difference can be, in part, explained by relatively effective rent control. Nevertheless, it should be noted that for the post-1917 period there are very few usable observations (advertisements containing rents) and, hence, great caution is needed when interpreting these results. shows that during the war, the number of advertisements published by landlords (especially, those including rents) drastically declined, while the number of advertisements placed by tenants looking for lodging increased. Moreover, in Berlin, where rent control was implemented starting from 1919, the rents in 1917 also lagged behind the national consumer price index.Footnote61

Figure 4. Hedonic housing rent vs. wholesale price index, 1913–1919. Sources: consumer price index – Pervushin (1925); housing rent index – own calculations.

Table 2. Evolution of the number of advertisements in the newspaper “Kievlyanin”.

As landlords were not readily willing to violate the provisions of law prohibiting rent increases, they sought ways to circumvent them. A rational reaction of the landlords to the impossibility of increasing rent revenues was their attempts to cut costs or to find alternatives sources of income. The landlords were “saving” on repairs and provision of services to the tenants. Oftentimes, while formally setting the rent at the legal level, the landlords were forcing new tenants to buy some rudimentary furniture for exorbitant prices. Landlords also tried to lodge those tenants, who were ready to pay large amounts of money in order to stay in the city. To do so, they needed to get rid of the incumbent tenants. The methods that were employed by the landlords to make the life of their tenants difficult, as described in the contemporary press, are striking. For example, landlords prohibited having pets or playing musical instruments, restricted water supply and did not stoke the fire. As a result, the Kiev city authorities received multiple complaints from the affected tenants.Footnote62

During the occupation of Ukraine by the Central Powers, new methods of evading rent controls were invented. In Kamenets-Podol’skiy, the landlords threatened the tenants, who did not agree to pay above the allowed bounds, to transfer the dwellings to the employees of the Podolsk railroads.Footnote63 In other cities, the landlords appealed to the foreign military command and asked them to evict the tenants, who were apparently neglecting the premises, by requisitioning the property.Footnote64 The right to create arbitration councils, given by the rent control act of the Russian Provisional Government to the municipalities, was not implemented everywhere. For instance, in Proskurov and Vinnitsa during the Hetmanate they did not function, despite the multiple requests of townspeople.Footnote65 On average, in the settlements, where no arbitration councils existed, the rents were higher. In June 1918, the landlords of Proskurov, for example, raised rents by 500%.Footnote66 Another disadvantage of the rent control acts was that housing construction became unprofitable because the rental revenues of the landlords did not cover their expenditure for building and maintaining the houses. State intervention also brought some advantages. It allowed, to a certain extent, the weakening of social tensions in the urban settlements. Dwelling owners who broke the law, were punished by fines and their names were published in the newspapers.Footnote67

Finally, we undertook a case study of the activity of the housing arbitration councils introduced by the Act of 1917 using the example of Gaisin, a town with a population of 15,000. The council was founded in early 1918 by the gorodskaya duma (the parliament/legislative power at the municipal level in the Russian Empire) and functioned for six months until the Hetman's act was issued. During this period, the arbitration council considered 125 cases.Footnote68 Persons from various social strata appealed to the council, including priests, school teachers, as well as military and civil officers of low and high ranks; for example, the local marshal of nobility (predvoditel’ dvoryanstva) Sevost’yanov.Footnote69 The landlords fiercely resisted and on multiple occasions the head of the council called the police to restore order.Footnote70 Contemporary commentators evaluated the effectiveness of the arbitration council in Gaisin ambiguously. On the one hand, on August 15, 1918, in reaction to large rent increases by the landlords, the Gaisin city duma requested the head of the local arbitration council to assess the rental values of all apartments in the town in 1914–1916 and create a table of housing rents in accordance with the Act of 1917, which would be obligatory for all the local landlords.Footnote71 As a result, for example, landlord L. Kuzminskiy had to reduce the annual rent from 2500 to 960 rubles. On the other hand, the newspapers reported that the inhabitants of Gaisin had complained about speculation by landlords, who, despite the existence of the arbitration council, rented big apartments with 8–10 rooms and then sublet them on a basis at 100 rubles per room per month.Footnote72

Conclusion

The war led to significant movements of population on the territory of Ukraine and to the redirection of resources to serve the military machine. As a result, the housing issue rapidly deteriorated into a housing crisis. The state tried to alleviate the crisis by relying on prohibitive policies. Each new act adopted by the authorities extended the list of accommodations and settlements subject to rent controls and strengthened tenant protection. At the same time, unable to check the rent increases, the state raised the legal rent ceilings. In fact, different political regimes pursued similar policies. Given that the vast majority of the urban population (both poor and rich) were tenants, rent increases and evictions represented a general problem. Hence, it can be concluded that the rental market regulations represented an ad hoc reaction of authorities to the pressing issues. The militarisation of the whole economy implied an increased reliance upon restrictive measures. For example, not only rents, but also prices for staple foods (especially, bread and meat) and its distribution were controlled.Footnote73 Moreover, in 1915, rent controls were introduced in many governorates independently. Housing market policy had little to do with the political preferences of the authorities, but was just following a general trend.

However, in the situation of an economic crisis caused by the war, all these attempts were, to a large extent, fruitless, since they were combating the symptoms but not the “sickness.” Although reliable and consistent data on rent evolution during WWI are missing, the fact that each new regulation set higher upper limits on rents implies that rent controls were largely ineffective. Moreover, they were undermined by the landlords’ opportunistic behaviour. Again, in the absence of statistics concerning the violations of rent control and tenancy protection regulations by landlords, it is impossible to judge whether these violations were single cases or mainstream behaviour. Contemporary newspapers abound with reports on such cases, but it is also possible that they exaggerated. On the one hand, the tenants were forced to pay an increasingly higher rent for increasingly uncomfortable housing. On the other hand, the landlords incurred losses due to ever growing inflation with the possibilities of rent increases being severely restricted.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributors

Konstantin A. Kholodilin is a research associate at the Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung Berlin and Professor at the National Research University Higher School of Economicsin St. Petersburg. His research focuses on the housing market, especially in Germany and Russia in the early 20th century, and on a comparative cross-country analysis of governmental housing policies regulating the relationships between landlords and tenants.

Timofiy Gerasymov is a Lecturer at the Department of Philosophy and Humanities of the Vinnytsia National Technical University. He investigates the everyday life and the social history of Ukrainian cities during World War I and the Hetmanate of P. Skoropadskiy.

Notes

1. See K.A. Kholodilin, ‘Quantifying a Century of State Intervention in Rental Housing in Germany’, Urban Research and Practice 10, no. 3 (2017): 267–328 for Germany; W. Wilson, ‘A Short History of Rent Control’, House of Commons Library (2017), for the United Kingdom; and J.W. Willis, ‘Short History of Rent Control Laws’, Cornell LQ 36 (1950): 54–94 for a wide array of countries.

2. See, for example, a detailed overview of the housing legislation during WWI in International Labour Office, European housing problems since the war. (Imprimeries réunies S.A.: Geneva, 1924) and A. R.Miletić, ‘Tenancy vs. Ownership Rights. Housing Rent Control in Southeast and East-Central Europe, 1918–1928’, Mesto a dejiny, 5, no. 1 (2016): 51–74.

3. As exemplified in AN URSR, Iсторiя мiст i сiл Української РСР: Київ (History of Urban and Rural Settlements of Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic: Kiev). (Київ: Гол. ред. УРЕ АН УРСР, 1973) and V.G. Sarbey, V.I. Borisenko and V.V. Panashenko, История Киева: в 3 т., 4 кн. Том 2: Киев периода позднего феодализма и капитализма (History of Kiev in 3 Volumes and 4 Books. Volume 2: Kiev during the Later Feudalism and Capitalism) (Киев: Наукова думка, 1983).

4. O.L. Vil‘shanska, ‘Повсякденне життя населення України пiд час Першої свiтової вiйни’, Український iсторичний журнал 4 (2004): 56–70.

5. V.B. Molchanov, ‘Вплив Першої свiтової вiйни на життєвий рiвень населення України’, in Проблеми iсторiї України ХIХ – початку ХХ ст., Volume ХXIII, ed. O.P. Reent, V.V. Shevchenko, and V.T. Borisenko (К.: Iнститут iсторiї України, 2014), 92–102.

6. O.O. Vityuk, ‘Заходи мiських дум щодо регулювання житлових вiдносин серед населення на Подiллi у 1917–1919 рр.’, Науковi працi iсторичного факультету Запорiзького нацiонального унiверситету 37 (2013): 97–100 and T. Yu. Gerasimov, ‘Вплив квартирного законодавства 1917–1918 рр. на житловi умови мешканцiв подiльських мiст доби Гетьманату П. Скоропадського (квiтень-грудень 1918 р.)’, Науковi працi Кам’янець-Подiльського нацiонального унiверситету iменi Iвана Огiєнка: Iсторичнi науки 21 (2011): 422–9.

7. O.P. Prishchepa, ‘Мiста Правобережної України кiнця ХVIII – початку ХХ ст.: сучасний стан дослiджень та перспективи вивчення’, Науковий вiсник Схiдноєвропейського нацiонального унiверситету iменi Лесi Українки. Iсторичнi науки 12 (2013): 131–9.

8. In the beginning of 1914, according to A.G. Rashin, Население России за 100 лет (1811–1913): статистические очерки (Population of Russia During 100 years (1811–1913): Statistical essays) (М.: Государственное статистическое издательство, 1956), 37, the share of urban population in Right-Bank Ukraine was as follows: in Kievskaya governorate 18.0%, in Podol’skaya governorate 8.8% and in Volynskaya governorate 8.4%. The average share for the whole Empire was 15.3%. A high urbanization level of Kievskaya governorate was attained in large part thanks to Kiev, which accounted for the largest part of the city-dwellers of the region: 520,500 out of 863,300; some 60.3% of the urban population.

9. L.V. Koshman, ‘Культурное пространство русского города XIX – начала XX вв. К вопросу о креативности исторической памяти’, NB: Культуры и искусства 2 (2013): 42–115.

10. Kievskaya mysl, ‘Рост строительства в Киеве’, 9 July 1914, 6.

11. According to G. Naumov, Бюджеты рабочих города Киева: По данным анкеты, произведённой в 1913 году Обществом экономистов и Ремесленной секцией при Киевской выставке (Budgets of the Workers of Kiev) (Киев: Типография И.И. Чоколова, 1914). This is comparable to other European countries. For instance, in Germany in 1907–1910, rent accounted for 17–18% of household income on average. Even low-income families spent “only” 20% of their budget on rental housing; see S. Ascher, Die Wohnungsmieten in Berlin von 1880–1910 (Erlangen: Carl Heymanns Verlag, 1917), 28.

12. Yuzhnaya kopeika, ‘В тени’, 20 February 1913, 3.

13. Zhizn‘ Volyni, ‘Переезд в город’, 22 July 1914, 3.

14. Zhizn‘ Volyni, ‘Дороговизна квартир’, 1 August 1914, 3.

15. Yuzhnaya kopeika, ‘Стыдно!’, 6 September 1914, 2.

16. O.I. Averbah, Законодательные акты, вызванные войной 1914–1915 гг., Volume 1 (Legal Acts Brought about by the War 1914–1915) (Петроград: Типография Петроградского товарищества печатного и издательского дела «Труд», 1916), 15.

17. O. L. Vil’shanska, ‘Повсякденне життя i суспiльнi настрої населення’, in Велика вiйна 1914–1918 рр. i Україна, ed. O. Reent (K.: TOB «Видавництво “КЛIО”», 2014), 454.

18. V. Prihod’ko, Пiд сонцем Подiлля: спогади. Ч. 2 (Вiнниця: ТОВ “Консоль”, 2011), 388.

19. Kiev, ‘Строительный кризис’, 19 September 1914, 4.

20. Yuzhnaya kopeika, ‘Весенние картинки‘, 12 April 1915, 3.

21. A.L. Sidorov, Экономическое положение России в годы Первой мировой войны (Economic Situation of Russia during World War I) (М.: Наука, 1973), 338.

22. Kievskaya mysl, ‘К строительному сезону’, 26 May 1915, 3.

23. Gosudarstvennyi arhiv Vinnitskoy oblasti, Ф. Д-230. – Оп. 1. – Д. 1605. – 1017 л., л. 1, 911.

24. Kiev,‘Прекращение строительных работ’, 31 July 1916, 4.

25. A.K. Lisii, ‘Повiтове мiсто Подiлля в буремнi 1914–1917 рр.’, in Народи свiту i велика вiйна 1914–1918 рр.: матерiали Всеукраїнської наукової конференцiї 3–4 квiтня 2015 р. (Вiнниця, ТОВ «Нiлан-ЛТД», 2015), 248.

26. L.M. Zhvanko, ‘Органiзацiя транспортування бiженцiв Першої свiтової вiйни у тиловi губернiї України (лiто–осiнь 1915 р.)’, Науковi працi iсторичного факультету Запорiзького нацiонального унiверситету 40 (2014): 40.

27. Vil'shanska, ‘Повсякденне життя’, 454.

28. Zhizn‘ Volyni, ‘Больной вопрос’, 16 September 1915, 3.

29. Yuzhnaya kopeika, ‘Под квартирным гнётом’, 12 July 1915, 2.

30. Zhizn‘ Volyni, ‘Квартирный «голод»’ 18 August 1916, 3.

31. A coup d’état on 29 April 1918, and supported by the military of Germany and Austro- Hungary, resulted in P.P. Skoropadsky becoming the Hetman of Ukraine. Therefore, the period of Ukrainian history between 29 April and 14 December 1918 is called the Hetmanate. The official name of the country was the Ukrainian State (Ukrayinska Derzhava).

32. Slovo Podolii, ‘Квартирный налог’, 22 October 1918, 1.

33. A.A. Goldenveizer, ‘Из Киевских воспоминаний (1917–1921 гг.) (From Kiev’s memories (1917–1921)’, Архив Русской Революции 6 (Берлин: Изд. И. В. Гессена, 1922), 226.

34. Gosudarstvennyi arhiv Vinnitskoy oblasti, Ф. Д-230. – Оп. 1. – Д. 1826. – 23 л., л. 360.

35. In July–August 1915, similar ordinances were issued in 41 governorates: 18 ordinances at the governorate level and four at the military district level, each military district covering several governorates. In 1914, the Russian Empire consisted of 98 governorates.

36. From here on the date before parenthesis denotes the date according to the Gregorian calendar, while that in parentheses stands for the date according to the Julian calendar.

37. Yugo-Zapadnyi kray, ‘Обязательное постановление (Compulsory Ordinance)’, 4 August 1915, 4.

38. Kievskie gubernskie vedomosti, ‘Обязательное постановление (Compulsory Ordinance)’, 105, 8 October 1915, 2.

39. Kievskie gubernskie vedomosti, ‘Обязательное постановление (Compulsory Ordinance)’, 43, 16 April 1916, 2.

40. In order to minimize risks of non-payment, the landlords often forced their tenants to pay rent several months in advance.

41. Similar exceptions existed in the acts on rent controls adopted in other European countries: e.g. in Austria, France, Germany and Spain.

42. Cited from A. Bezugol'nyi and N. Kovalevskiy, ‘Kovaliov Istoriya voenno-okruzhnoi sistemy v Rossii 1862–1918’ (The History of the Military Districts System in Russia 1862–1918) (Moscow, 2012).

43. Podol’skie gubernskie vedomosti, ‘Обязательное постановление (Compulsory Ordinance)’, 68, 5 September 1915, 3.

44. Podol’skie gubernskie vedomosti, ‘Обязательное постановление (Compulsory Ordinance)’, 10, 3 February 1916, 3.

45. O.I. Averbah, Законодательные акты, вызванные войной 1914–1915 гг., Volume 2 (Legal Acts Brought About by the War 1914–1915) (Петроград: Типография Петроградского товарищества печатного и издательского дела «Труд», 1916), 696–704.

46. Vremennoe pravitel'stvo, Собрание узаконений и распоряжений Временного правительства. Номер 191, статья 1136 (Collection of laws and ordinances of the Russian Provisional Government. Number 191, article 1136) (Петроград: 1917).

47. The apartment tax (kvartirnyi nalog) was a tax imposed on tenants. According to the apartment tax act of May 27 (14), 1893, all settlements were split in five classes. For example, class I included the two most important cities of the Empire: Petrograd and Moscow. Within each class, between 19 and 36 categories, according to rent levels, were identified.

48. Derzhavnyi Visnik, 63, 26 October 1918, 1.

49. Gerasimov, ‘Вплив квартирного законодавства 1917–1918 рр.’, 428.

50. V. Verstyuk (ed.) Директорiя, Рада народних мiнiстрiв Укра¨ıнської народної республiки 1918–1920. Документи i матерiали у 2 томах (Directory, Rada of People’s Ministers of Ukrainian People’s Republic 1918–1920. Documents and Materials in Two Volumes) Volume 1 (Киев: Видавництво iменi Олени Телiги, 2006), 439–40.

51. Although a gap in the coverage of the rent control act, between 1 October 1919 and 24 May 1920, appears here, it is apparent that laws must have been in place to cover this time period. However, the specific prolongation of laws have not yet been identified or located.

52. V. Verstyuk (ed.) Директорiя, Рада народних мiнiстрiв Укра¨ıнської народної республiки 1918–1920. Документи i матерiали у 2 томах (Directory, Rada of People’s Ministers of Ukrainian People’s Republic 1918–1920. Documents and Materials in Two Volumes) Volume 2 (Киев: Видавництво iменi Олени Телiги, 2006), 40.

53. Slovo Podolii, ‘Дороговизна и подоходный налог’, 17 October 1918, 1.

54. S.N. Prokopovich, Война и народное хозяйство (The War and the National Economy) (Москва: 1917), 75.

55. N.P. Obuhov, ‘Экономический кризис в России в годы Первой мировой войны’, Финансовый журнал 2 (2009): 161–72.

56. S.N. Prokopovich, Народное хозяйство СССР в двух томах (The National Economy of the USSR in Two Volumes) Vol. 2 (New York, 1952), 78.

57. B. Andrusishin, У пошуках соціальної рівноваги: Нарис історії робітничої політики українських урядів революції та визвольних змагань 1917–1920 рр (Киев: Федер. профспілок України, 1995), 92.

58. T. Yu, Gerasimov, ‘Соціально-побутова історія подільських міст доби Гетьманату П. Скоропадського (квітень-грудень 1918 р.)’ (manuscript of doctoral dissertation, Вінниця, 2013), 150.

59. S.A. Pervushin, Хозяйственная конъюнктура: Введение в изучение динамики русского народного хозяйства за полвека (The Business Cycles: An Introduction to the Examination of the Dynamics of the Russian National Economy During Half a Century) (Moscow, 1925), 157–159 and 221.

60. K.A. Kholodilin, ‘War, Housing Rents, and Free Market: A Case of Berlin’s Rental Housing Market during World War I’, European Review of Economic History 20, no. 3 (2016): 322–44.

61. K.A. Kholodilin, ‘War, Housing Rents, and Free Market’, 337.

62. Yuzhnaya kopeika, ‘Робинзон/Маленький фельетон’, 13 June 1916, 2.

63. Podol’skii kray, ‘Каменецкие домовладельцы … ’, 11 October 1918, 4.

64. Slovo Podolii, ‘Изобретательные домовладельцы’, 1 October 1918, 2.

65. Slovo Podolii, ‘Больной вопрос’, 13 June 1918, 1.

66. Slovo Podolii, ‘Проскуров’, 29 June 1918, 2.

67. Institut rukopisei NBU imeni V. Vernadskogo, Ф. 91, № 1. 1 л., 2.

68. Gosudarstvennyi arhiv Vinnitskoy oblasti. Fond D-286. Opis' 1. Delo 93. L. 97.

69. Ibid., L. 267.

70. Ibid., L. 266 ob.

71. Ibid., L. 150 ob. – 151. Unfortunately, the table itself could not be found in the archive.

72. Slovo Podolii, ‘Gaisinskaya zhizn’, 10 October 1918, 2.

73. N.A. Svavitskiy, ‘Таксы’, in Труды комиссии по изучению современной дороговизны (Proceedings of the Commission Investigating the Reasons for the Current Dearness), VI (Москва: Городская типография, 1916), 161–274 and N.D. Kondratiev, Рынок хлебов и его регулирование во время войны и революции (Corn Market and Its Regulation During the War and Revolution) (Москва: Наука, 1991).