Abstract

In this article I consider the problems, dilemmas and opportunities surrounding approaches to social value in heritage conservation and management. Social value encompasses the significance of the historic environment to contemporary communities, including people's sense of identity, belonging and place, as well as forms of memory and spiritual association. These are fluid, culturally specific forms of value created through experience and practice. Furthermore, whilst some align with authorized heritage discourses, others are created through unofficial and informal modes of engagement. I argue that traditional, expert-driven modes of significance assessment fail to capture the dynamic, iterative and embodied nature of social value. Social research methods, such as qualitative interviewing and rapid ethnographic assessment, are more suited to assessing social values. However, these are best combined with community participatory practices, if we wish to capture the fluid processes of valuing the historic environment.

Introduction

The need to identify, narrate and measure value is a complex and difficult issue within the heritage sector. The assumption of intrinsic worth, linked to historic and aesthetic values, was central to the foundation of the modern conservation movement and continues to underpin the moral duty of care promoted by international conservation charters. More recently there has been increasing emphasis, in both public policy and conservation practice, on the social values associated with the historic environment. However, these shifts in the values underpinning heritage management and conservation have created a number of philosophical and practical issues.

This article arises out of a critical review of approaches to social values, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research CouncilFootnote1 (AHRC), the results of which are reported on in full in CitationJones and Leech (2015). Here I consider the problems, dilemmas and opportunities in addressing the social values associated with heritage places, specifically in relation to how these inform their management and conservation. Encompassing the significance of the historic environment to contemporary communities, social values are fluid, culturally specific forms of value embedded in experience and practice. Some may align with official, state-sponsored ways of valuing the historic environment, but many aspects of social value are created through unofficial and informal modes of engagement. I argue that expert-driven modes of significance assessment tend to focus on historic and scientific values, and consequently often fail to capture the dynamic, iterative and embodied nature of people's relationships with the historic environment in the present. Social research methods such as focus groups, qualitative interviews and participant observation offer a more effective means to assess social values, and one way forward is to make such methods part of mainstream heritage practice. However, there is also the question of whether a value-based model, which inevitably tends to objectify and fix different categories of value, is even appropriate. I will argue that a combination of rapid qualitative research methods alongside public participatory practice offers a way forward in terms of addressing the fluid processes of valuing the historic environment. Mixed methods involving participatory practice also offer opportunities in terms of sustaining an ongoing dialogue between community groups and heritage organizations; one that builds social and community values into participatory forms of management and conservation. To conclude the article, I will briefly illustrate these arguments with reference to another AHRC-funded project, the ACCORD Project,Footnote2 which involved community co-production of 3D visualizations of heritage places.

Social value is a complex concept (CitationPearson and Sullivan 1995, 155). It has been variously used to refer to some or all of the following: community identity; attachment to place; symbolic value; spiritual associations and social capital. For the purposes of this article, social value is defined as a collective attachment to place that embodies meanings and values that are important to a community or communities (CitationJones and Leech 2015, para 1.6; after CitationJohnston 1994, 10; CitationByrne et al. 2003). The concept encompasses the ways in which the historic environment provides a basis for identity, distinctiveness, belonging and social interaction. It also accommodates forms of memory, oral history, symbolism and cultural practice associated with the historic environment.

The heritage management context

Before dissecting the wider problems, dilemmas and opportunities surrounding the social value of heritage, it is important to briefly consider its place in heritage management and conservation policies (for a full discussion see CitationJones and Leech 2015). A concern with the values that underpin cultural significance is fundamental to heritage conservation today (CitationAvrami et al. 2000; Citationde la Torre and Mason 2002; CitationGibson and Pendlebury 2009). However, whilst aspects of what we now call social value were alluded to in nineteenth-century conservation debates, early-mid twentieth century international Charters privileged historic, scientific and aesthetic values, as defined by various forms of expertise, alongside an emphasis on historic fabric (e.g. CitationAthens Charter 1931; CitationVenice Charter 1964). It is only in the second half of the twentieth century that the social value of heritage became an explicit component of conservation policy and practice. This also coincides with increasing attention to broader, non-expert perceptions of heritage and the communal values associated with these.

Many recognize the Burra Charter (ICOMOS Australia 1979, subsequently revised in 1981, 1988 and 1999) as a key document in bringing about this shift (CitationEmerick 2014, 3–4). Despite a lingering emphasis on the physical fabric of heritage places (CitationWaterton et al. 2006, 348), the Charter puts the assessment of cultural significance at the heart of the conservation process on the basis that: ‘places of cultural significance enrich people's lives, often providing a deep and inspirational sense of connection to community and landscape and to lived experiences’ (CitationICOMOS Australia 1999 [1979], 1). The Charter defines cultural significance as the sum of a set of interlocking values including aesthetic, historic, scientific, social or spiritual value for past, present or future generations (Article 1.2). In theory, it thus places social value on an equal footing with historic, aesthetic and scientific value (ibid., 12; though see CitationByrne et al. 2003, 4–6). Furthermore, the latest version of the Charter emphasizes that contemporary communities who attach specific meanings and values to heritage places should be involved in their conservation and management (CitationICOMOS Australia 1999 [1979], Article 12).

Subsequently, this emphasis on the social and communal values of heritage has become evident in other national and international heritage instruments. For instance, the European Landscape Convention (CitationCouncil of Europe 2000) emphasizes the need to assess landscapes in terms of ‘the particular values assigned to them by the interested parties and the population concerned’ (Article C(b)). The Faro Convention (CitationCouncil of Europe 2005) takes this concern a step further by primarily focusing on ‘ascribed values’ rather than on the material heritage itself (CitationSchofield 2014). The Faro Explanatory Report elaborates that these ascribed values are, in part, the product of (self-defined) ‘heritage communities’ extending beyond communities of heritage specialists.

Looking at the UK, the high-level strategy and policy documents of the devolved heritage organizations (Historic England (formerly English Heritage), Cadw, Historic Environment Scotland (HES) (formerly Historic Scotland) and Department of the Environment Northern Ireland respectively) also reveal an increasing emphasis on significance, social value and public participation (e.g. CitationEnglish Heritage 2008; CitationHistoric Scotland 2011). For instance, English Heritage's Conservation Principles (Citation2008, 7–8) is directly influenced by the Burra Charter and emphasizes that the sustainable management of heritage places should start with an understanding of significance. The document identifies ‘communal value’ (encompassing symbolic, social and spiritual value) as one of the key types of value making up significance and provides a very useful discussion of what this encompasses. However, in practical terms social and communal values remain relatively neglected in the designation, management and conservation of heritage places throughout the UK. There are a few recent exceptions where social and communal values have played a key role in designation, over and above historic value or architectural merit. These include the designation of Brixton Market as a Grade II Listed Building (CitationEmerick 2014, 227) and Tinker's Heart in Argyll as a Scheduled Monument (CitationRutherford 2016, 16–17). However, the recognition and investigation of social value in these cases (as in others) resulted from public protest and appeal, rather than something that is routinely addressed in designation or management contexts.

There are a complex body of reasons for the continued marginalization of social value and associated public participation. Institutional cultures and established forms of heritage expertise mean that historic, scientific and aesthetic values still eclipse social values (see CitationSmith 2006; CitationEmerick 2014). Heritage practitioners and policy-makers often regard social values expressed by contemporary communities as more transient and instrumental than historic, scientific and aesthetic values, which in contrast are assumed to be more intrinsic aspects of heritage places. Furthermore, the means for evaluating historic, scientific and aesthetic values are long established, embedded in expertise and connoisseurship (Citationde la Torre and Mason 2002, 3–4). Constraints and demands on resources, especially at a time of austerity, often mitigate against the active investigation of social value in the context of routine conservation and management. Finally, the last decade has witnessed the appearance of a governmental concern with the ‘benefits’ of the historic environment, for instance in terms of well-being, health, education and pride in place (e.g. CitationScottish Government 2014). In response, organizations in receipt of public funding tend to focus on measuring the instrumental success of state-sponsored heritage management policies in terms of generating such ‘benefits’ thus rationalizing the investment of resources. However, this concern with benefits tends to distract attention away from the social values that communities attach to heritage places in and for themselves.

These are genuine obstacles, but I suggest they point to more fundamental issues relating to the complex, shifting and, at times, conflicting nature of social value. To understand the philosophical and practical challenges involved I will now turn to the nature of social value and its implications.

Social value and the historic environment

There is a wide range of research focusing on the meanings and values produced through the historic environment, deriving from various academic disciplines and applied policy contexts. Meaning is integral to the production of value in respect to the historic environment, but the production of meaning can take a variety of different forms, many of which have not typically been a core consideration in heritage management contexts. The ways in which communities understand and value historic places is often rooted in oral narratives, folktales, genealogies and spiritual associations that generate specific, often localized, kinds of meanings (e.g. CitationMacdonald 1997; CitationBender 1998; CitationRiley et al. 2005). These also function as memory practices, which are actively ‘engaged with the working out and creation of meaning’ (CitationSmith 2006, 59). Such memory practices can be seen as a form of heritage ‘work’, but they rarely conform to the authorized linear chronologies that the heritage sector seeks to produce. Instead, social memory usually consists of a dynamic collection of fragmented stories that revolve around family histories, events, myths and community places (CitationSmith 2006, 59–60; CitationJones 2010, 119–120). These stories are continually reworked in everyday contexts where they are passed within and between generations. They are thus embedded in social relationships, providing a basis for the negotiation of identities and power relations.

As CitationJohnston (1994, 10) argues, attaching meanings and identities to specific localities is also integral to the production of a ‘sense of place’. Studies show that people's sense of place is made up of locally constituted meanings and values, over and above nationally recognized heritage ones (CitationHarrison 2004; CitationWaterton 2005). Furthermore, multiple claims to place can be produced in relation to any particular aspect of the historic environment, making them a potential source of tension and conflict (CitationWaterton 2005, 317; see also CitationSchofield 2005; CitationAvery 2009; CitationOpp 2011). Here, identity and ownership invariably intersect with place-making in a complex fashion (CitationJones 2005). Communal identities are predicated upon categories of sameness and difference that create group boundaries (CitationCohen 1985), and this is evident in relation to broader collective identities such as nationality, ethnicity and class, as well as local community identities (CitationDicks 2000; CitationSmith 2006; CitationPeralta and Anico 2009; CitationWatson 2011).

Performance and practice also play a key role in the establishment of social value at heritage sites (CitationBagnall 2003; CitationDeSilvey 2010). These may include: community festivals; ritual and ceremonial activities; everyday practices; recreation and leisure; memorial events and ‘mark-making’ (CitationFrederick 2009, 210) performances such as graffiti. They can also take the form of recording practices, such as photography, video, drawing and survey, alongside archaeological and historical investigation. All of these practices and performances are mediated by various forms of embodied and sensory experience (CitationCox 2008; CitationO'Connor 2011). They also constitute arenas for the production, negotiation and transformation of meanings, memories, identities and values (CitationCrang and Tolia-Kelly 2010).

The implications for the heritage sector are profound. First, social values and meanings may have historical dimensions, but these are by no means always commensurate with historical value, particularly as defined by heritage professionals (CitationByrne et al. 2003; CitationSchofield 2014). Indeed places deemed to be of relatively minor historical value may be extremely important in terms of oral history, memory, spiritual attachment and symbolic meaning (CitationJones 2004; CitationSchofield 2005; CitationO'Brien 2008; CitationHarvey 2010). This is particularly pertinent in the case of ethnic minorities, working class groups and other communities who may feel underrepresented by national heritage agendas, and indifferent to many officially designated sites and places (CitationEmerick 2014, 228).

Second, social meanings and values, and the communities that produce them, are often fluid, transient and contested (CitationRobertson 2009; CitationDeSilvey and Naylor 2011, 13–14; CitationLoh 2011, 239–241). Contemporary communities rework and reproduce the materiality and meaning of the historical landscape through performance and practice. The dynamic nature of social values, and their at times elusive and intangible qualities, often sit in stark contrast to other forms of value that members of the heritage sector have often seen as more intrinsic, namely historic, scientific and aesthetic values. It might therefore be preferable to conceive of social value as a process of valuing heritage places rather than a fixed value category that can be defined and measured. Indeed, the same could also be argued for historic, scientific and aesthetic values, which, despite a veneer of stability and ‘objectivity’, also tend to be fluid and contested on closer inspection.

Lastly, aspects of social value, such as symbolic meaning, memory and spiritual attachment, may not be directly linked to the physical fabric of a historic building, monument or place. As CitationJohnston (1994, 10) states, ‘meanings may not be obvious in the fabric of the place, and may not be apparent to the disinterested observer’. Indeed, they may not even be subject to overt expression within communities, remaining latent in daily practices and long-term associations with place, only crystallizing when threatened in some way (see CitationJones 2004; CitationO'Brien 2008; CitationOrange 2011, 108–109). The complex relationship between tangible and intangible aspects of heritage in the domain of social value is a particular challenge in European contexts where the long-standing pre-occupation with tangible heritage continues to be relatively entrenched.

Addressing social value: methods and approaches

So how might the complexities of social value be taken into account in the context of heritage management and conservation? Some commentators have argued that the nature of social value demands new forms of expertise and methodologies that directly engage with contemporary communities (e.g. Citationde la Torre and Mason 2002; CitationJones 2004; CitationHarrison 2011). Traditionally, conservation and management of the historic environment has been based on archaeological, architectural and scientific expertise. These forms of expertise are important, and there is no question that they need to be maintained, but they do not readily lend themselves to an appreciation of social values. In recent decades heritage organizations have often turned to consultation procedures and large-scale surveys, as a means of gauging public attitudes and concerns. The former can provide a useful avenue for people to voice concerns about developments impacting on specific heritage places, whereas organizations use the latter more commonly to gauge wider attitudes to the historic environment in general (e.g. English Heritage's Power of Place Survey (Citation2000) conducted by Ipsos Mori). However, neither approach is well suited to acquiring a detailed understanding of the social values associated with the historic environment, let alone the specific values associated with particular heritage places.

To gain an understanding of social values it is necessary to carry out research with communities of interest using qualitative methods derived from sociology and anthropology. These methods involve the use of various techniques, for instance focus groups, qualitative interviews and participant observation, to reveal the meanings and attachments that underpin aspects of social value. Researchers have also employed other methods, including analysing archival documents and historic photographs, as well as oral and life histories. Using such methodologies to investigate forms of social value and meaning that are inherently dynamic inevitably creates a snapshot of a particular landscape that requires regular review and revision. Nevertheless, they produce a more sophisticated body of knowledge to make informed choices about the conservation and management of the historic environment, as demonstrated in countries where they have been taken up by heritage institutions, such as the US National Park Service.Footnote3 The model of Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Procedures (REAP) developed in relation to the US National Environmental Policy Act illustrates that such methodologies can be adapted to meet constraints on time and resources (CitationLow 2002; CitationTaplin et al. 2002). For instance, the use of REAP at Independence National Park in Philadelphia over a period of just 2–3 weeks’ fieldwork revealed that the Park holds multiple values for city residents and that these vary significantly between ethnic groups (CitationTaplin et al. 2002, 90–91). Furthermore, many participants felt that the story of National Independence, projected to visiting tourists, excludes wider stories and forms of commemoration associated with resident communities. The study also gathered extensive data on the use of the Park, revealing the tensions resulting from competing practices and recreational agendas.

Such short-term, focused research involving ethnographic practices is increasingly popular in many applied research contexts, including design and technology, health and safety, medicine and science (e.g. CitationKnoblauch 2005; CitationPink and Morgan 2013). Aside from shorter time-frames, rapid qualitative research is often characterized by mixed methods and multi-disciplinary teams. For instance, the REAP study of Independence National Park discussed above involved: site walks (describing a landscape from a participant's perspective); individual interviews; focus groups; expert interviews; observation/mapping of behaviour and archival research (CitationTaplin et al. 2002, 87). Some researchers also advocate using some kind of active intervention to create ‘intense routes to knowing’ (CitationPink and Morgan 2013, 351). Such interventions allow intensive observation of ‘situated performances’ (CitationKnoblauch 2005, para 28), which can be accompanied by focused group interviews where participants are encouraged to talk to one another: ‘asking questions, exchanging anecdotes, and commenting on each others’ experiences and points of view’ (CitationKitzinger and Barbour 1999, 4).

Qualitative social research inevitably depends upon members of the public participating in the research process, but design, analysis and interpretation usually remain in the control of experts who are trained in the use of such methods (and who often have a background in sociology or social anthropology). Another important area of development is the increase in community-led initiatives, particularly in respect to locally significant heritage places. These can focus on community-led identification and recording, as well as forms of community custodianship and conservation. The frameworks and supporting structures for such schemes are usually initiated and promoted by one or more heritage organizations, and involve various forms of guidance, support and/or training (although they rarely incorporate qualitative social research as will be discussed below). Examples of these kinds of initiative include specific projects with defined subject matter, time-scales and funding, such as Scotland's Rural Past (2006–2011) and Scotland's Urban Past (2015–2020), both led by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS, now part of HES). Longer-term schemes, such as the Adopt-a-Monument Scheme, managed by Archaeology Scotland (which has existed in various forms since 1991 and is currently supported by HES), support community groups who are interested in local heritage places to develop creative and sustainable conservation projects, as well as forms of community custodianship.

One of the main advantages of such initiatives is that they encourage community members to identify historic places that are of value to them, and support them in conducting research and looking after heritage places. Yet at the same time they can still privilege traditional historic values, in part because the training and guidance offered by such schemes tends to focus on orthodox recording, investigation and conservation techniques informed by traditional value categories (for instance see the Adopt-a-Monument Scheme Toolkit,Footnote4 and the online training resources for Scotland's Urban Past).Footnote5 Social value in turn usually receives little weight in the guidance provided to community groups, in the UK and more generally across European countries (as can be seen in the aforementioned resources of these otherwise impressive schemes). So, although social values may be the underlying motivation behind community participation, they are often masked by other values considered more intrinsic to the heritage places themselves.

Arguably, the most productive approach to addressing social value lies in forms of collaborative co-production that involve both professionals and members of relevant communities. Collaborative or ‘counter-mapping’ is an area that has received significant attention in recent years, not least because of the work of the National Parks and Wildlife Service of New South Wales, Australia (CitationEnglish 2002; CitationByrne and Nugent 2004; CitationDepartment of Environment, Climate Change and Water, New South Wales 2010). Such mapping involves the integration of archival evidence, such as maps and aerial photographs, with other qualitative research methods such as place-based oral history interviews, site walks with community members and audio-visual recordings (see CitationHarrison 2011). Technologies such as GPS and GIS can be used to integrate tangible material traces with intangible beliefs, stories and other forms of cultural knowledge, thus creating multi-vocal, textured representations of historic places (CitationHarrison 2011). However, a key part of the process is that the attribution of expertise, whilst still important, is de-centred and distributed, with professionals and community participants being recognized for their different kinds of knowledge and skilled practice (see CitationByrne and Nugent 2004; CitationHarrison 2011; CitationDe Nardi 2014; CitationEmerick 2014). Routinely applying such methodologies could contribute to a much more holistic model for managing heritage objects, places and landscapes for their historical, scientific, aesthetic, spiritual and social values. Perhaps more importantly, such approaches bring heritage professionals and communities together in activities that themselves provide a basis for the collaborative production and negotiation of value (CitationDe Nardi 2014, 13).

In the next section, I will draw on a specific project that I have recently been involved in to explore how this might transform the way we deal with heritage. Whilst the ACCORD Project was not primarily designed to address the problems and dilemmas surrounding social value in routine heritage management and conservation, the results reveal the potential of combining community co-production with rapid qualitative research. Indeed, the Project has subsequently informed routine Cultural Significance assessment at a Property in the Care of HES.

Community co-production of heritage using 3D technologies: the ACCORD project

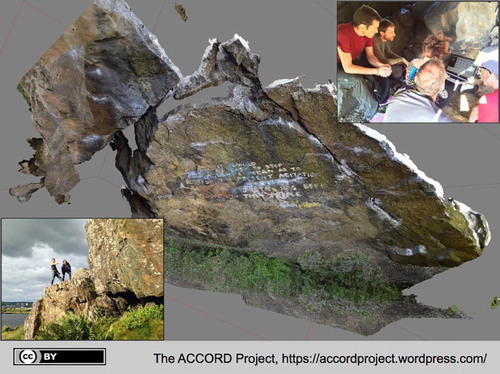

The ACCORD project (2013–15) aimed to examine the opportunities and implications of digital visualization technologies for community engagement and research (see CitationJeffrey et al. 2015).Footnote6 Despite their increasing accessibility, techniques such as laser scanning, 3D modelling and 3D printing have remained firmly in the domain of heritage and conservation specialists. Expert forms of knowledge and/or professional priorities frame the use of digital visualization technologies, rarely addressing forms of community-based social value. Consequently, the resulting digital objects fail to engage communities as a means of researching and representing their heritage. The ACCORD project addressed this gap through the co-design and co-production of 3D heritage models that encompass social value and engage communities with transformative digital technologies. The project team worked with 10 community heritage groups spread across Scotland to co-design and co-produce 3D records and models of heritage places significant to them (see Figure ). For the most part we used consumer-grade Photogrammetry (Structure from Motion) and Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), as they are cheaper and more accessible than laser-based technologies. In some cases, we also used 3D printing to create physical models.

FIGURE 1 Members of the Ardnamurchan Community Archaeology Group and the ACCORD project team engaged in photogrammetric recording of Camas Nan Geall early mediaeval cross-incised standing stone. A visualization of the finished model is in the bottom right. (CC-BY, ACCORD Project).

Reflection on the nature of the relationships between community groups, digital heritage professionals, the heritage places they record and the outputs they create was a central aspect of the ACCORD Project. The participatory approach, involving heritage professionals and community groups in a co-design process, allowed us to explore contemporary social values associated with heritage places. Statements of social value, encompassing both the 3D models and the tangible heritage objects they represent, were co-produced and archived with the digital records. A major objective of the project was to investigate how the use of 3D recording technologies reinforces and/or changes community conceptions of social value, if at all. We also explored whether community co-production of 3D models adds to the significance and authenticity of these digital representations (and the 3D prints that we produced from them).

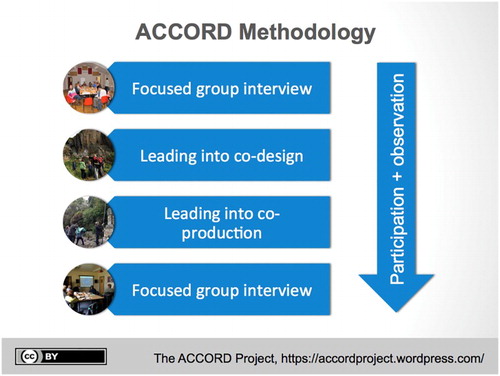

We used focused qualitative research methods alongside the participatory community practice to examine the social values associated with the 3D models and the heritage places they represent (see Figure ). We held two focused group interviews with each community group, one at the beginning of our work with that group and one at the end. The first focus group explored the nature of the group and the historic monuments, buildings and/or objects they are interested in. Here, the participants discussed the meanings and values associated with specific monuments, buildings and/or objects and examined feelings of attachment and belonging. The second focus group dealt with the participants’ experiences of 3D visualization, including the recording and modelling process. It also explored their responses to the models themselves and the forms of social, value, ownership and authenticity associated with them, if any. While co-producing the 3D records and models, we used participant observation to examine how the practices themselves were involved in revealing, negotiating and transforming forms of social value. Through this participant observation, we also explored changing attitudes to 3D technologies and the heritage places being recorded/modelled.

FIGURE 2 A diagram illustrating the phases involved in the use of rapid qualitative research alongside community co-design and co-production in the ACCORD project. (CC-BY, ACCORD Project).

The results of the ACCORD project will be discussed in depth elsewhere. However this brief summary highlights the potential of the ACCORD methodology for gaining new insights into the social values associated with heritage places. As a result of community co-design, the participants selected a wide range of heritage places for recording and modelling. These ranged from prehistoric monuments to historic buildings, sculptured stones, memorials, a rock climbing site and forms of public sculpture. Some of these heritage places are designated scheduled monuments or listed buildings, but in such cases their local social value often diverges from the values underpinning their authorized national heritage designations. Other heritage places that the ACCORD participants selected sit uneasily on the margins of authorized notions of heritage, whilst nevertheless linked to high levels of social value. The focused qualitative research revealed multiple forms of social value associated with oral historical and genealogical narratives, as well as wider forms of social memory and place-making, which often grapple with previous population displacement. Many of the heritage places selected also play important symbolic roles, and are seen as catalysts for mobilizing community action in the present, in particular associated with regeneration. The ACCORD project also highlighted the heterogeneous, contested and dynamic nature of social value, not least because the project itself created activities, records and visualizations of heritage places that acted as a locus for value production and negotiation. The resulting 3D models accrued value in the context of co-production, but they also reinforced existing values associated with the heritage places they represent, and even generated new forms of social value. The virtue of using focused qualitative research alongside community participatory work is that we can also observe and record these dynamic processes at work.

In summary, the collaborative process of recording and modelling provides a lens through which to examine and record social values, and whilst in the case of ACCORD we used 3D technologies, other forms of recording or engaging with, heritage places could serve the same purpose. The short-term intensive nature of the collaboration alongside the use of focused qualitative research makes such methods adaptable to heritage management and conservation contexts, where pressure on time and resources means that more in-depth ethnographic or sociological studies are rarely feasible. Indeed, the potential of the ACCORD methodologies is illustrated by the social value statement that the team co-produced with the climbers they worked with at Dumbarton Rock (see Figure ), which is now part of HES's revised Statement of Cultural Significance for Dumbarton Castle. Whilst reflecting the values of a specific community of practice at a particular time, this statement provides much greater insight into the contemporary meanings and values associated with the Rock (known as ‘Dumby’ by the climbers), that subsequent management and conservation initiatives can take into account. As with any kind of research into social value there are issues with selectively representing the values of some contemporary communities over others. There is also the question of how to accommodate the dynamic nature of social value. Nevertheless, these objections do not justify the continued marginalization of social and communal values in decisions about how to manage and conserve heritage places. One could conduct similar short-term, intensive work with other groups who express an interest in, or attachment to, the place. Furthermore, one could use cycles of collaborative work involving both community groups and heritage professionals to counter the risk of objectifying and fossilizing social values that are in practice fluid and heterogeneous. As well as addressing some of the challenges surrounding social value in the heritage sector, such an approach also creates opportunities. Through such participatory processes, a network of relationships is nurtured between communities and heritage places, creating a framework through which different forms of knowledge and expertise can be acknowledged, and diverse ways of looking after heritage places might be sustained.

Conclusion

In this paper I have argued that social value and related forms of public participation have become increasingly prominent in international heritage frameworks and the conservation policies and guidelines of national heritage bodies. Yet they remain relatively marginal in many areas of heritage practice, and many continue to conflate social value with expert evaluations of historic and aesthetic value, rather than ‘any of the benefits which the population might be able to gain from the “cultural heritage” by and for themselves’ (CitationBell 1997, 14; see also CitationByrne et al. 2003; CitationEmerick 2014). There is often insufficient knowledge of the social value of specific heritage places, and constraints on resources and forms of expertise often mitigate against actively investigating social value in the context of routine conservation and management. Traditional forms of value, in particular historical and architectural value, also continue to prevail in the context of significance assessment, such that social value is often conflated with them, rather than treated as a definitive category in its own right (CitationByrne et al. 2003; CitationGibson 2009, 74).

There is a need to address these issues if social value and public participation in heritage conservation is to move beyond the domain of rhetoric. After all, most current practice is far removed from the complex ‘dialectical comparison between analyses by experts and the values attached by the population to landscape’ recommended by the Guidelines for the Implementation of the European Landscape Convention (CitationCouncil of Europe 2008, II.2.3.A). However, we also need to recognize that the dynamic, iterative and embodied nature of people's relationships with heritage places pose a more fundamental challenge to how we conceive of, and indeed practice, heritage. Ultimately, we need to overcome the far-reaching tensions that persist ‘between the idea of heritage as “fixed”, immutable and focused on “the past”, with that of a mutable heritage centred very much on the present’ (CitationSmith and Akagawa 2009, 2). Collaborative methods involving heritage professionals and communities in a network of on-going relationships with heritage places are arguably the most productive means to accommodate the inherently fluid processes of valuing the historic environment.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on a project funded by the AHRC: Valuing the Historic Environment: a critical review of approaches to social value (Ref: AH/L005654/1), which was part of the AHRC's Cultural Value Project (http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/research/fundedthemesandprogrammes/culturalvalueproject/). The project was led by the University of Manchester and involved the following partners: English Heritage (now Historic England); Historic Scotland and RCAHMS (now both part of HES) and the Council for British Archaeology. The article also discusses the AHRC-funded project: ACCORD: Archaeological Community Co-Production of Research Resources (Ref: AH/L007533/1), led by Glasgow School of Art in partnership with the University of Manchester, RCAHMS and Archaeology Scotland. I would like to thank my collaborators in these two projects for their contributions: Keith Emerick, Alex Hale, Mike Heyworth, Stuart Jeffrey; Cara Jones, Steven Leech, Mhairi Maxwell, Robin Turner and Luke Wormald. The paper was presented at a workshop on Heritage Values and the Public, organized by the H@V Network (http://heritagevalues.net/) in Barcelona, 19th – 20th Feb 2015. I would like to thank the organizers of that event and Margarita Díaz-Andreu for her comments. Finally the paper benefitted from the comments of the editors and two anonymous peer reviewers. Any shortcomings of course remain my own.

ORCiD

Siân Jones http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6157-7848

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Siân Jones

Siân Jones was Professor of Archaeology and Heritage Studies at the University of Manchester during the period when this research was carried out. Subsequently, she has moved to the University of Stirling, where she is Professor of Environmental History and Heritage. Her research focuses on the politics, meanings and values surrounding historic monuments, buildings and places. Recent research projects have focused on identity and place-making, conservation practice, authenticity, social value and community heritage. Her work is interdisciplinary, combining archaeology, social anthropology, cultural history and heritage studies. Siân's publications include: The Archaeology of Ethnicity, Early Medieval Sculpture and the Production of Meaning, Value and Place and the co-authored monograph, A Fragmented Masterpiece: recovering the biography of the Hilton of Cadboll cross-slab. She has also recently edited a special edition of the International Journal of Historical Archaeology on Memory and Oral History.

Notes

6 See also https://accordproject.wordpress.com/).

References

- The Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments, 1931.

- Avery, Tracey. 2009. “Values Not Shared: The Street Art of Melbourne's City Laneways.” In Valuing Historic Environments, edited by Lisanne Gibson and John Pendlebury, 139–56. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Avrami, Erica, Randall Mason and Marta de la Torre. eds. 2000. Values and Heritage Conservation. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute.

- Bagnall, Gaynor. 2003. “Performance and Performativity at Heritage Sites.” Museum and Society 1(2):87–103.

- Bell, Dorothy. 1997. The Historic Scotland Guide to International Conservation Charters. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland.

- Bender, Barbara. 1998. Stonehenge: Making Space. Oxford: Berg.

- Byrne, Denis, Helen Brayshaw and Tracy Ireland. 2003. Social Significance: A Discussion Paper. Second edition. Hurstville: New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service.

- Byrne, Denis and Maria Nugent. 2004. Mapping Attachment: A Spatial Approach to Aboriginal Post-contact Heritage. Sydney: Department of Environment and Conservation, New South Wales.

- Cohen, Anthony P. 1985. The Symbolic Construction of Community. London: Routledge.

- Council of Europe. 2000. European Landscape Convention. (Florence Convention). European Treaty Series 176. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Council of Europe. 2005. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (The Faro Convention). European Treaty Series 199. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Council of Europe. 2008. Guidelines for the Implementation of the European Landscape Convention. (Florence Convention). Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Cox, Rupert. 2008. “Walking Without Purpose: Sensations of History and Memory in Nagasaki City.” Journeys 9(2):76–96. doi: 10.3167/jys.2008.090205

- Crang, Mike and Divya P. Tolia-Kelly. 2010. “Nation, Race and Affect: Senses and Sensibilities at National Heritage Sites.” Environment and Planning A 42(10):2315–31. doi: 10.1068/a4346

- De Nardi, Sarah. 2014. “Senses of Place, Senses of the Past: Making Experiential Maps as Part of Community Heritage Fieldwork.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 1(1):5–22. DOI: 10.1179/2051819613Z.0000000001

- Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water, New South Wales. 2010. Cultural Landscapes: A Practical Guide for Park Management. Sydney: Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water, New South Wales.

- DeSilvey, Caitlin. 2010. “Memory in Motion: Soundings from Milltown, Montana.” Social & Cultural Geography 11(5):491–510. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2010.488750

- DeSilvey, Caitlin and Simon Naylor. 2011. “Introduction: Anticipatory History.” In Anticipatory History, edited by Caitlin DeSilvey, Simon Naylor and Colin Sackett, 9–20. Axminster: Uniformbooks.

- Dicks, Bella. 2000. Heritage, Place and Community. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Emerick, K. 2014. Conserving and Managing Ancient Monuments: Heritage, Democracy, and Inclusion. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- English, Anthony. 2002. The Sea and the Rock Gives us a Feed: Mapping and Managing Gumbaingirr Wild Resource Use Places. Hurstville: New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service.

- English Heritage. 2000. The Power of Place: The Future of the Historic Environment. London: English Heritage.

- English Heritage. 2008. Conservation Principles. London: English Heritage.

- Frederick, Ursula K. 2009. “Revolution is the New Black: Graffiti/Art and Mark-Making Practices.” Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress 5(2):210–37. doi: 10.1007/s11759-009-9107-y

- Gibson, Leanne. 2009. “Cultural Landscapes and Identity.” In Valuing Historic Environments, edited by Leanne Gibson and John R. Pendlebury, 67–92. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Gibson, Leanne and John R. Pendlebury. eds. 2009. Valuing Historic Environments. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Harrison, Rodney. 2004. Shared Landscapes: Archaeologies of Attachment and the Pastoral Industry in New South Wales. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

- Harrison, Rodney. 2011. “‘Counter-Mapping’ Heritage, Communities and Places in Australia and the UK.” In Local Heritage, Global Context: Cultural Perspectives on Sense of Place, edited by John Schofield and Rosy Szymanski, 79–98. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Harvey, David. 2010. “Broad Down, Devon: Archaeological and Other Stories.” Journal of Material Culture 15(3):345–67. doi: 10.1177/1359183510373984

- Historic Scotland. 2011. Scottish Historic Environment Policy. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland.

- ICOMOS. 1964. The Venice Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites. IInd International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, Venice, 1964. Adopted by ICOMOS in 1965

- ICOMOS Australia. 1999 [1979]. Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Significance (The Burra Charter), revised 1999.

- Jeffrey, Stuart, Alex Hale, Cara Jones, Siân Jones and Mhairi Maxwell. 2015. “The ACCORD Project: Archaeological Community Co-production of Research Resources.” In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology, CAA 2014, edited by François Giligny, François Djindjian, L. Costa, Paola Moscati and S. Robert, 1–7. Paris: CAA.

- Johnston, Chris. 1994. What is Social Value? A Discussion Paper. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

- Jones, Siân. 2004. Early Medieval Sculpture and the Production of Meaning, Value and Place: The Case of Hilton of Cadboll. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland.

- Jones, Siân. 2005. “Making Place, Resisting Displacement: Conflicting National and Local Identities in Scotland.” In The Politics of Heritage: The Legacies of ‘Race’, edited by Jo Littler and Roshi Naidoo, 94–114. London: Routledge.

- Jones, Siân. 2010. “‘Sorting Stones’: Monuments, Memory and Resistance in the Scottish Highlands.” In Interpreting the Early Modern World, edited by Mary C. Beaudry and Jim Symonds, 113–39. New York: Springer.

- Jones, Siân and Steven Leech. 2015. Valuing the Historic Environment: A Critical Review of Existing Approaches to Social Value. London: AHRC.

- Kitzinger, Jenny and Rosaline S. Barbour. 1999. “Introduction: The Challenge and Promise of Focus Groups.” In Developing Focus Group Research, edited by Rosaline S. Barbour and Jenny Kitzinger, 1–21. London: SAGE. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781849208857.n1.

- Knoblauch, Hubert. 2005. “Focused Ethnography” [30 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(3): Art. 44. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0503440.

- Loh, Kah. S. 2011. “‘No More Road to Walk’: Cultures of Heritage and Leprosariums in Singapore and Malaysia.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 17(3):230–44. doi: 10.1080/13527258.2011.556660

- Low, Setha. M. 2002. “Anthropological-Ethnographic Methods for the Assessment of Cultural Values in Heritage Conservation.” In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage, edited by Marta de la Torre, 31–49. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute.

- Macdonald, Sharon. 1997. Reimagining Culture: Histories, Identities and the Gaelic Renaissance. Oxford: Berg.

- O'Brien, Suzanne J. Crawford. 2008. “Well, Water, Rock: Holy Wells, Mass Rocks and Reconciling Identity in the Republic of Ireland.” Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art and Belief 4(3):326–48. doi: 10.2752/175183408X376683

- O'Connor, Penny. 2011. “Turning a Deaf Ear: Acoustic Value in the Assessment of Heritage Landscapes.” Landscape Research 36(3):269–90. doi: 10.1080/01426397.2011.564729

- Opp, James. 2011. “Public History and the Fragments of Place: Archaeology, History and Heritage Site Development in Southern Alberta.” Rethinking History 15(2):241–67. doi: 10.1080/13642529.2011.564830

- Orange, Hilary. 2011. “Exploring Sense of Place: An Ethnography of the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site.” In Local Heritage, Global Context: Cultural Perspectives on Sense of Place, edited by John Schofield and Rosy Szymanski, 99–118. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Pearson, Michael and Sharon Sullivan. 1995. Looking After Heritage Places: The Basics of Heritage Planning for Managers, Landowners and Administrators. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Peralta, Elsa and Marta Anico. eds. 2009. Heritage and Identity: Engagement and Demission in the Contemporary World. London: Routledge.

- Pink, Sarah and Jennie Morgan. 2013. “Short-term Ethnography: Intense Routes to Knowing.” Symbolic Interaction 36(3):351–61. DOI: 10.1002/SYMB.66

- Riley, Mark, David C. Harvey, Tony Brown and Sara Mills. 2005. “Narrating Landscape: The Potential of Oral History for Landscape Archaeology.” Public Archaeology 4(1):15–26. doi: 10.1179/pua.2005.4.1.15

- Robertson, Mhairi. 2009. “Àite Dachaidh: Re-connecting People with Place-Island Landscapes and Intangible Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 15(2–3):153–62. doi: 10.1080/13527250902890639

- Rutherford, Allan. 2016. “Monuments in the Hearts of Communities.” Archaeology Scotland 25:16–17.

- Schofield, John. 2005. “Discordant Landscapes: Managing Modern Heritage at Twyford Down, Hampshire (England).” International Journal of Heritage Studies 11(2):143–59. doi: 10.1080/13527250500070337

- Schofield, John. 2014. “Heritage Expertise and the Everyday: Citizens and Authority in the Twenty-First Century.” In Who Needs Experts? Counter-Mapping Cultural Heritage, edited by John Schofield, 1–12. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Scottish Government. 2014. Our Place in Time: The Historic Environment Strategy for Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

- Smith, Laurajane and Natsuko Akagawa. 2009. “Introduction.” In Intangible Heritage, edited by Laurajane Smith and Natsuko Akagawa, 1–10. London: Routledge.

- Taplin, Dana. H., Suzanne Scheld and Setha M. Low. 2002. “Rapid Ethnographic Assessment in Urban Parks: A Case Study of Independence National Historic Park.” Human Organization 61(1):80–93. doi: 10.17730/humo.61.1.6ayvl8t0aekf8vmy

- de la Torre, Marta and Randall Mason. 2002. “Introduction.” In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage, edited by Marta de la Torre, 3–4. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute.

- Waterton, Emma. 2005. “Whose Sense of Place? Reconciling Archaeological Perspectives with Community Values: Cultural Landscapes in England.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 11(4):309–25. doi: 10.1080/13527250500235591

- Waterton, Emma, Laurajane Smith and Gary Cambell. 2006. “The Utility of Discourse Analysis to Heritage Studies: The Burra Charter and Social Inclusion.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 12(4):339–55. doi: 10.1080/13527250600727000

- Watson, Sheila. 2011. “‘Why Can't We Dig Like They Do on Time Team?’ The Meaning of the Past within Working Class Communities.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 17(4):364–79. doi: 10.1080/13527258.2011.577968