ABSTRACT

Since 2014, UCL Qatar has undertaken a diverse programme of community engagement as part of an archaeometallurgical research project at the Royal City of Meroe, Sudan. We present initial analyses of anonymous questionnaires conducted as part of this programme. We designed the questionnaires to evaluate qualitatively residents’ knowledge about, outlook on, and experience with local archaeological sites, to generate an understanding of the social fabric within which archaeology is situated. Additionally, we collected quantitative demographic data to assess critically the local community composition. Statistical analyses of the questionnaire have highlighted the heterogeneous nature of the local communities, and how their often-divergent knowledge, outlooks, and experiences with archaeology are influenced by numerous social, economic, historical, and political factors: an idealized audience for ‘community archaeology’ does not exist in our context. Nevertheless, community engagement, leading to community archaeology, should form an integral part of an archaeological research programme from inception to completion.

Introduction

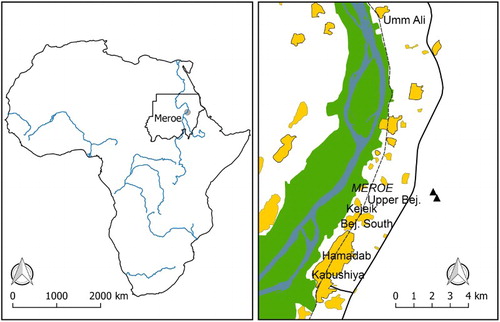

The Royal City of Meroe (henceforth ‘Meroe’) is situated c. 200 km north of Khartoum on the east bank of the Nile in the Republic of the Sudan (). Meroe is one of a number of spectacular and monumental archaeological sites in a region known as ‘The Island of Meroe’, which became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011. The site was a royal capital of the Kingdom of Kush, which ruled vast territory from at least the early eighth century BCE to the fourth century CE. Meroe has long attracted attention from scholars visiting the region (e.g. Bruce Citation1790; Cailliaud and Jomard Citation1826; Shinnie Citation1967), and archaeological research projects continue to investigate details concerning the origins, development, and organization of Kush (see Török Citation2015 for the most recent consideration of Kushite history). The impressive architectural remains of Meroe’s temples, palaces, and the so-called Royal Baths, as well as the associated pyramid burials, demonstrate the significance of the site as a key Kushite period centre of power. The landscape surrounding Meroe comprises a number of architecturally remarkable archaeological sites including Meroitic religious and administrative centres.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of Meroe in the Republic of the Sudan (left) and the locations of each village within which community engagements were conducted (shown in relation to Meroe, right). Map produced by Frank Stremke.

Meroe in its modern context

Like many archaeological sites along the Nile, Meroe is situated on the banks of the river and surrounded by modern villages. Today, as in the past, populations live within the Nile Valley to exploit the river water, and thus thousands of residents live and work near or next to the archaeological remains of Meroe. The site’s physical location in a riverine residential locale fosters subtle but frequent(ly meaningful) interactions between ‘people’ and ‘place’: children play among the ruins, men pass through on their way to the fields, and local people sell souvenirs to tourists and offer camel rides around the pyramids. Festivals and gatherings are also held at the sites throughout the year. Since the early twentieth century, Sudanese and international teams have regularly employed a significant number of local people to work on archaeological excavations. Meroe and the surrounding sites are thus firmly embedded within social and economic aspects of local life.

Unlike other areas of Sudan, recent conflicts have not scarred this region, known as the Shendi Reach. It has not experienced large-scale population displacement or the loss of the archaeological past, such as has been the case along other stretches of the Nile during the development of hydro-electric dams (see Säve-Söderbergh Citation1987; Hopkins and Mehanna Citation2010 at the First Cataract; Hänsch Citation2012; Näser and Kleinitz Citation2012 at the Fourth Cataract). Nevertheless, an average of 57.6 per cent of Sudan’s rural population live below the poverty line, and rural populations, such as those near Meroe, face perpetual challenges in accessing basic resources (World Bank Citation2011). Existing land and water sources are under severe pressure from the increasing number of people moving into the area (many of whom have been gradually pushed south by long-term factors such as desertification across the Sudanic belt), and the commoditization and long-term renting of land to private investors (Linke Citation2014; Umbadda Citation2014).

UCL Qatar at Meroe

Since 2012, University College London (UCL) Qatar-based researchers have been investigating ancient iron production associated with the Kingdom of Kush, the extensive remains of which are prominent in the Meroe landscape. At this writing, the team has spent 10 seasons excavating at Meroe and at the nearby Meroitic site of Domat al Hamadab. Sudanese archaeologists and Sudanese trainee-students form part of the multi-national team, which can reach up to 70 people including the local workforce.

The UCL Qatar research project attempts to ‘decolonize’ archaeological practice by implementing a long-term strategy to involve an increasing number of Sudanese specialists and non-specialists in developing research questions and implementing research programmes (a process sometimes referred to as ‘indigenization’, see Lane Citation2011). We aim for collaborative decision-making and broad public participation to create ‘useable pasts’ that contribute ‘practical knowledge’ to Sudanese society (Lane Citation2011). For the more immediate future, such a decolonizing process involves communication and discussions with members of local communities about our research objectives and results, as well as involving and training Sudanese students and members of other stakeholder professions. Around 80 per cent of the UCL Qatar community engagement team are consistently Sudanese, and during the most recent archaeological season, almost 50 per cent of the specialist excavation team were Sudanese.

We appreciate, of course, that to ‘decolonize’ also means addressing notions of knowledge pursuit – perhaps evolving the questions we ask of the archaeological record and challenging long-held, western-developed assumptions about the past (Edwards Citation2004). This also applies to questions of knowledge production, particularly in terms of the languages and spaces in which we choose to publish. Nevertheless, our commitment to decolonizing our archaeological practices is strong, recognizing that ‘Archaeology on the African continent is a century-long practice, characterized largely by research approaches that do not consult and engage with local and indigenous communities’ (Pikirayi and Schmidt Citation2016, 1). This is true in the case of Meroe: archaeological investigations here pre-date the twentieth century, yet comprehensive, long-term ‘community archaeology’ has been lacking.

General impressions based on informal conversations with local people in the early years of the project revealed a diversity of local outlooks towards the history of Meroe. Some people expressed pride in the achievements of ‘their ancestors’, while others spoke of a disassociation between themselves and the ancient inhabitants of Kush. Many were keen to receive ‘more information’ about the sites, and still more were interested in the potential economic benefits tourism could bring to the area.

After we recognized the diversity of opinions within the broader community, we decided to undertake a diagnostic study to generate a more comprehensive understanding of these opinions and investigate what steps would be necessary to develop community archaeology around Meroe before we tried to conceive locally relevant programmes.

Why ‘community engagement’?

Debates concerning relevant terminology for the diverse approaches linking archaeology with non-professionals, including local communities, are discussed elsewhere in detail (e.g. Smith and Waterton Citation2009, 11–20; Belford Citation2014; Richardson and Almansa-Sánchez Citation2015). Here we use the term ‘community engagement’ to signify both our broad involvement with local communities, and the specific activities we undertake in six locations around Meroe. We use the term engagement to highlight the differences between our comparatively new work, compared to that of an active and long-term, sustainable community archaeology programme. As expressed by Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), such programmes aim ‘to stimulate enquiry and promote active discovery through partnership and participation, widening access to and appreciation of … heritage’ (http://www.mola.org.uk/community-archaeology). Sustainability, defined by Belford (Citation2014, 27) as ‘the creation of a solid and focused local understanding of, and care for, the historic environment’, is essential at the social, intellectual, and economic level and a key feature of well-established community archaeology programmes. Important too is the co-development of participatory or collaborative research designs, in which communities are equal partners in and co-producers of research projects (Schmidt Citation2016). While our engagement with local communities is based around interaction and archaeology, it does not, in our case, mean that non-archaeologists are involved in the archaeological decision-making process, beyond the fact that we provide information about the past to interested members of the community (which could, of course, be considered a first step – see Atalay Citation2012).

Our engagement, rather, attempts to collect data on what knowledge, outlooks, and experiences exist locally in relation to archaeology, and relate these to how ‘the community’ is constituted demographically. Thus, we may fully understand the audience with whom and for whom community archaeology strategies might be conceived, developed, and implemented effectively in the future. We argue that each community should be considered as distinctive, with its own demographic make-up, histories, and resulting outlooks, and perceived needs and priorities, in relation to the heritage around it. Our results indicate that in addition to intra-community diversity, significant inter-community diversity exists (see also Meskell Citation2005, 90; Straight et al. Citation2015, 394). This identifiable intra- and inter-community complexity creates significant challenges to developing appropriate and valuable community archaeology packages for different groups within ‘the community’.

We thus see this community engagement as the critical first phase towards developing and integrating community archaeology into formal research, from start to finish. In British archaeology (and elsewhere), this would often be termed ‘consultation’, which has different formal and informal meanings worldwide. Space does not permit us to explore the global literature about consultation here, but our intent was to gain an intuitive understanding of the communities for whom (and with whom) we work – how they identify themselves (collectively or individually), their livelihoods and education, and what is important to them, in relation to the archaeology around them. We argue that in Sudan this phase is essential, because UCL Qatar archaeologists are often culturally, linguistically, and religiously different from those local communities.

‘Community engagement’ thus encompasses all of our community interactions, from meetings and tea drinking to attending weddings, funerals, and graduations; from student training to two-way community lectures (delivered for local people by the archaeologists and vice versa); from throwing festivals to multi-media output. Producing and delivering such activities requires and deserves significant time and dedication, particularly considering the absence of formalized and published engagement programmes so far in Sudan, the legacy of western archaeologists removing ‘treasure’ from archaeological sites, and of course the role of the British in colonizing Sudan for the first half of the twentieth century. At Meroe, we work in an Arabic-speaking Muslim context, one governed by conservative Islamic laws (sharia), the nuances of which were unknown to us when we arrived in Sudan. Sustained relationships of trust and multi-linear community engagements, therefore, serve as a basis for two-way learning and understanding.

The engagements described here comprised 11 community meetings designed to understand local views using quantitative and qualitative questionnaires and having open discussions. Here we present the framework used and initial analyses of some of these data. Even at this preliminary stage, we have begun to understand the complexities surrounding the concept of ‘the community’ (and thus future community archaeology and participatory projects), but also the potential for such work in this region of Sudan.

Methods

The locations

Most of the local excavation employees (mostly men but occasionally women), hired as part of the UCL Qatar archaeological team, live in two villages: Kejeik, situated on Meroe’s south-western boundary and Upper Bejrawiya, just to the north-east (). Our long-standing relationship with the local employees, plus UCL Qatar’s residence in Hamadab (3 km due south of Meroe), made these three communities obvious choices for our engagement activities. In addition to employing a local workforce, social and economic relationships with other nearby areas have developed, leading us to include three additional villages in our programme. The team relies on the twice-weekly market held at the nearby town of Kabushiya, around 4.5 km south of Meroe, and, when travelling to Meroe from Hamadab each day, the team passes by the village of Bejrawiya South. Somewhat further afield is the large village of Jebel Umm Ali, chosen because it has been a past focus of UCL Qatar archaeological research. ‘Communities’ are therefore defined by their residents’ close ties of kinship and their interdependent political and economic relationships. We selected these six communities because they were where both the archaeological site and team have the most presence, and are thus likely to have the most impact. We held meetings in Kejeik, Hamadab, and Kabushiya in 2014 and in Jebel Umm Ali, Upper Bejrawiya, and Bejrawiya South in 2015.

The meetings

Each community meeting was tripartite in structure, and approximately 2.5–3 hours in length. The first section of each meeting was dedicated to conducting the questionnaire. Interviewees received information about the purpose and general content of the anonymous questionnaires before each interview, and were assured they could withdraw at any time. The UCL Ethics Research Committee approved the questionnaires and strategies prior to these being implemented in the field. At least five Sudanese team members spent an average of 90 minutes conducting these questionnaire-interviews (), while non-Sudanese team members (such as the authors) handed out refreshments and talked with local people.

Figure 2. Questionnaires being carried out by University of Khartoum students, Basil Kamal Bushra and Mohammed Nasreldein Babiker at a women’s meeting. Provided by authors.

This was followed by a presentation, which introduced the UCL Qatar team, the research aims and objectives of the archaeological project, and its current results. The final section of each meeting was an open discussion, whereby both the audience and the archaeologists asked each other questions. The aim was to encourage informal dialogue which allowed salient topics to develop organically, and issues arose that were not anticipated by us or represented in the questionnaires, but were of crucial importance to the audience and, therefore, to archaeologists. This section in particular proved critical to the two-way learning process.

Following advice from Sudanese colleagues, to ensure maximum attendance we held meetings after evening prayers, and on separate days for men and women to ensure high female turnout (aside from Kabushiya, where this was not logistically possible). We spent much time advertising the date, time, and location of each meeting, via word of mouth and announcements at local mosques (kindly facilitated by the imams). We delivered questionnaires and presentations in Arabic to avoid continual translation during the meetings and to prevent confusion in delivery. In preparation (and to contextualize our reasoning), we used classroom lectures to train Sudanese students and colleagues in the theory and practice of community archaeology, using literature such as Bartoy (Citation2012) and Little (Citation2012) as reference material. This enabled them to effectively conduct the meetings, supported by non-Sudanese, non-Arabic-speaking team members. We also provided training to conduct questionnaires sensitively, particularly when interviewing members of the opposite sex. The concept of gender identity in Sudan, and the principles that structure how men and women interact in ways regarded as ‘acceptable’, are complex and beyond the scope of this paper (but see Boddy Citation1989). In addition to ensuring professional and effective meetings, this training allowed Sudanese students and heritage professionals to gain community engagement experience. All team members understood the reasons for the strategy and were able to communicate this formally and informally to local people.

The questionnaire

We developed the questionnaire with advice from Sudanese colleagues. The first half of the questionnaire collected demographic data that could be quantitatively analysed, including age group, gabila (pl. gabaayil, a social unit defined by paternal bloodline or family, often translated as ‘tribe’ or ‘kinship group’), residence, livelihood(s), and educational experience. The second half of the questionnaire was a knowledge, outlook, and experience assessment, to understand each respondent’s pre-existing relationship with archaeology and archaeologists. Questions included whether or not the respondent or their family had worked with archaeologists, before moving to questions such as ‘what is ‘archaeology?’ and ‘what do you know about the Kingdom of Kush?’ Questions also investigated the channels through which archaeological and historical information is disseminated, and the aspirations respondents might have for the site. Of particular significance, for developing future community archaeology projects, were questions about outlook – such as whether the archaeological site brought benefits to the community, and if so, how. We deemed the residents’ outlook as particularly important to help us avoid the simple assumption that all residents are predisposed to like, or be interested in archaeology.

The relationships between demographic data and knowledge, outlook and experience, were analysed statistically using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo (http://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-product). Many answers to the questions were ‘bundled’, i.e. made up of several strands, and the software provided data on the frequency of words and concepts as they emerged in the responses. Questions to which there was no answer from the respondents were marked ‘undisclosed’ and discounted from this round of analysis.

Over 200 participants completed the questionnaire, and the Arabic transcripts were later translated into English. We presented the original Arabic versions to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums in Sudan (NCAM), for their use in developing community archaeology programmes in the future.

Results

provide information about the numbers of attendees at each of the meetings and the total numbers of interviews conducted. We present below a selection of results from certain key questions. These results illustrate significant diversity of knowledge, outlooks, and experiences of archaeology in this relatively small area, and demonstrate that ‘the community’ is not a homogeneous unit, in terms of intra- or extra- group and village relationships.

Table 1. 2014 participants.

Table 2. 2015 participants.

Table 3. Total numbers of people who attended the meetings and the number of people interviewed in total.

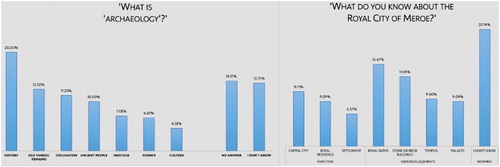

Knowledge assessment: What is archaeology; what do you know about the Royal City of Meroe?

These questions aimed to evaluate existing knowledge about western-conceived notions of ‘archaeology’ and in particular about the archaeology of Meroe. When asked, ‘what is ‘archaeology?’’, 20 per cent of the responses included the term ‘history’ and 12.5 per cent included the phrase ‘old things’ (). Other frequent responses included the words ‘civilization’, ‘heritage,’ and ‘science’. This indicated that, in general, people living in these villages know that the archaeological enterprise can include professionally investigating the past via material remains (‘science’, ‘things’), and creating a chronological narrative sequence of events (‘history’), one that centres on people (‘civilization’). Given the extensive history of archaeology at Meroe, this was perhaps to be expected. What was surprising, however, given this history, was that a large number of respondents, 13.75 per cent, answered that they ‘do not know’ what archaeology is, and a further 14.17 per cent gave no answer to this question. We are uncertain why.

In answer to the question, ‘What do you know about the Royal City of Meroe?’ many respondents provided examples of the general functions and idiosyncratic elements of Meroe (76.26 per cent). Yet nearly one quarter did not know anything or gave a negative response to this question (). On aggregate, we suggest that there was some recognition of Meroe’s original function and of the site’s key buildings. However, knowledge levels vary (both within and across the six communities) and respondents currently have, at best, only the most basic knowledge of Meroe’s role in Kushite civilization (the ‘official history’ of the site).

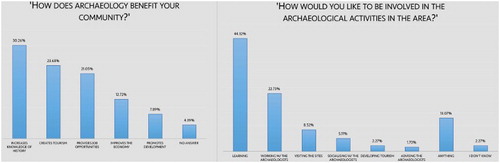

Outlook assessment: Does the archaeological site benefit your community, and if so, how; do you want to be involved in the archaeological activities of the area, and if so, how?

The majority of questionnaire respondents answered that ‘yes’, the archaeological site is beneficial to their community, and that they were keen to get involved in archaeological activities in the region (84 per cent and 83 per cent, respectively). represents the ways in which respondents provided their answers. When asked if the site benefits their community, 30.26 per cent noted that it provides ‘historical information’ or more simply ‘history’; 23.68 per cent included the idea of the site generating tourism; 21.05 per cent mentioned job opportunities, and others mentioned ‘the economy’ and ‘development’.

When asked, ‘how would you like to be involved in archaeological activities?’, a significant number (44.32 per cent) said they wanted to learn more – whether about the pyramids, local history, or about archaeologists themselves. Interacting with the archaeologists, either as colleagues, friends, or advisors, also made up a significant percentage of the responses.

Based on these responses, we propose that for the majority of respondents in these six communities, community members perceive the current main benefits of archaeology to be historical information and contributions to the local economy (via employment with the archaeological team, via infrastructural developments and/or via tourism). This suggests that our community archaeology efforts should focus on implementing educational programmes and stimulating channels for local economic development (many respondents noted that we partially do this already through archaeological employment, though they often noted pointedly that they, too, ‘want jobs’.) Many might suggest that these are predictable conclusions, but we suggest that in Sudan and elsewhere across Africa, archaeologists often dismiss these messages, and do not seek to understand various dimensions of community needs (see similar critiques of archaeology in the Middle East from Starzman Citation2012). Indeed, our data further suggest the Sudanese experience of archaeology is much more complex than this, as we will describe below.

Experience assessment: What are archaeologists looking for?

Earlier approaches to the archaeological heritage of Sudan by foreign archaeologists add complexity to the relationships we are attempting to develop with these local communities. From 2012 to 2016, as described above, we made significant efforts to develop a transparent working model for interaction. People were continually invited to the sites to observe excavations; the team made numerous formal and informal social visits, and advertised the dig house as permanently ‘open’ to visitors. However, we sometimes found a certain level of indifference in what archaeologists were actually doing. We attribute this, at least partly, to the history of archaeological research in Sudan, which has typically overlooked comprehensive, systematic engagement, or knowledge exchange with local communities. It was noticeable, for example, that in the questionnaires we conducted only six months after a major community engagement event (January 2015), 20.93 per cent of responses to the question ‘what are archaeologists looking for?’ still included the words, ‘gold’ and ‘treasure.’ Particularly troubling was that a total of almost 20 per cent (19.77 per cent) of respondents answered ‘I don’t know’, ‘They don’t tell us, they take it away’, or gave no answer.

These responses clearly suggest that more meetings and educational opportunities are necessary to reach mutual understandings of motivation. They also show that we must readily acknowledge the parallels our discipline has with other exploitative, extractive industries, and other structures in Sudan, and the prominent role westerners continue to play within them. This is particularly relevant around Meroe. The previous lack of systematic archaeological engagement has compounded the more general culture of top-down exploitation in Sudan. Overcoming such outlooks and creating new experiences is important, not just for site management and conservation issues (such as protection from looting and other forms of site destruction) but also to build mutual trust between archaeologists and the local communities, and dispel the notion that archaeologists benefit by depriving local people of cultural and economic resources.

Demographic assessment

One of the most salient concepts of collective identity in Sudan is that of gabila, and the majority of residents living around Meroe self-identify as belonging to the riverine agricultural Ja’aliyin, one of the largest gabaayil in the Nile Valley. In 2014, 96 per cent of questionnaire respondents identified as ‘Ja’aliyin’, as did 89 per cent of the 2015 respondents. However in 2015, as we gained understanding of the region’s social complexity, we amended the questionnaire to include more questions on individual and collective identities (although we recognize the fluid and often momentary nature of identity). Respondents then began to identify themselves secondarily as belonging to seven smaller family-community branches of the Ja’aliyin gabila, such as the Sa’adab in the Bejrawiya area, and the Omerab in Jebel Umm Ali. The results also show that in 2015 we were able to attract a statistically relevant number of attendees from members of other, non-Ja’aliyin gabaayil living around Meroe: 4.5 per cent respondents identified as Manasir, and 3.6 per cent as Hassaniya.

Nevertheless, while residents in the newer settlement area of Upper Bejrawiya primarily self-identify as belonging to the pastoral Manasir or Hassaniya, they were still not well represented within either meeting attendees or questionnaire respondents. Contrary to our strategy to try and engage specifically with pastoralists, the questionnaires demonstrate that riverine Ja’aliyin came the (albeit short) distance from their villages to the Upper Bejrawiya meetings in much larger numbers than the Manasir or Hassaniya residents. Low pastoralist attendance, even at the meetings in or near their own residences, characterized all the meetings and reflects the local intra-group power dynamics in which the agricultural Ja’aliyin are the dominant group, with consequences for the development of inclusive community archaeology programmes. For these initial analyses, we evaluated the Manasir and Hassaniya’s questionnaire responses alongside those of the Ja’aliyin, but future analyses will seek to tease out, explain, and address the differences between them.

In the open discussions, almost none of the respondents mentioned feeling biological or cultural attachments with the ancient Kushite inhabitants of Meroe, identifying instead as descendants of the Islamic Arab groups of the Peninsula whose gradual arrival and settlement in Sudan in the later medieval periods marks the ‘golden age’ of their history (see also Edwards Citation2004). This result is particularly noteworthy because it helps foreground the importance of identity and context, or perhaps more specifically ‘identity in context’; perceptions of archaeology here are most likely to be different from perceptions of the Nubians in the north, who openly claim descent from the people of ancient Kush.

Moreover, in place of ancestral or patrimonial claims, most of the 84 per cent of respondents who agreed that the archaeological site ‘is a benefit to our local community’ cited purely economic reasons for their answer. Similarly, questionnaire data concerning the development of Meroe as a tourist destination show that respondents embrace it as a prospect: 65 per cent of responses clustered around the potential that tourism has for local economic gain, many noting that tourism development is long overdue. The economic pressures briefly outlined at the beginning of this paper explain, in part, the value placed on economic and infrastructural development in relation to the archaeological sites in the area. Indeed, these economic pressures are caused by such similar industries that it compounds the level of mistrust evident in the some questionnaire answers, specifically regarding what archaeologists are looking for and potentially benefitting from.

It is important to note that the approval obtained from the UCL Ethics Research Committee did not include administering questionnaires to minors (under-18 years old). This is a significant loss in terms of evaluating local perceptions of archaeology: Sudan, like the rest of the continent, has a very young demographic profile, wherein 53 per cent of the population is under 19. Nevertheless, we interviewed people from all other age groups (18–30, 31–45, 46–65, and 66+) in each village aside from Kabushiya and Upper Bejrawiya, where we interviewed neither female nor male respondents over the age of 66 (in general, this age group is less represented than the rest, which is unsurprising considering Sudan’s young profile).

Respondent information is therefore not proportional across age groups, or between male and female respondents. However, some differences may be accounted for. For example, official data (as well as observations) show that Kabushiya is a small town with a large population of young adults and the social setting is more amenable for young people, including women, to attend events at night. In contrast, Jebel Umm Ali and Bejrawiya South are older, well-established but industry-less villages, with smaller populations of young people, but with women who have attained higher levels of education than elsewhere and who have more confidence about interacting with foreigners. This may explain why in Kabushiya the majority of male and female respondents were aged 18–45, whereas in Jebel Umm Ali and Bejrawiya South female respondents are mainly from the 46–66+ categories.

Education is also important to consider, and a particularly heterogeneous picture is evident within and between the six villages. In the case of Upper Bejrawiya, a higher proportion of males compared to females completed primary school, a slightly higher proportion of women than men completed secondary school, and while no men went to university, six women had completed university. In part, this is significant because in the Sudanese curriculum, pre-Islamic history is taught in depth only at secondary school, and only then for students who elect to pursue a humanities course. This means that, theoretically, only the students who complete(d) secondary school would have any significant knowledge about Kushite history from school. We were thus surprised that when asked, ‘how do you learn about archaeology?’, 22.82 per cent of respondents identified ‘school’ as their main source of knowledge. Perhaps less surprising was that the lowest number of answers mentioned ‘archaeologists’, but again our curiosity was sparked at the very low number of attributions to ‘archaeological employees’ such as the site guard, whose post has been held by members of one family since 1939. Although 19.92 per cent said they learn about the sites from ‘local people’, no one mentioned official or unofficial custodians of tradition or site information (nor were we ever directed to such an individual).

Future analyses should help us link these demographic variables more closely with responses. Nevertheless, the analyses begin to illustrate how the area’s broader community is far more diverse than it first appears, and that answers are not always predictable. For now, perhaps the most important results are that the questionnaire respondents are predominantly self-identifying Ja’aliyin, and that, because we did not interview minors, it is Ja’aliyin adults that are the main demographic group we ‘engaged’ with at our meetings.

Discussion

Although uneven demographic representation of respondents prevents generalized conclusions across all six communities, the results clearly indicate that each community should be considered as distinctive, with its own demographic make-up, histories, outlooks, perceived needs, and priorities. This adds significant complexity to the challenges of developing appropriate community archaeology packages, and we fully anticipate this diversity to translate into differing needs and archaeology-related priorities (although precisely how is unknown). For example, although local aspirations could be partially fulfilled by developing a local tourism sector at Meroe, it (or other strategies) may not be sustainable if applied across all six villages – or perhaps even within a single village. With reference to ‘packaging’ community-specific archaeology, our preliminary results provide strong foundations for development. It is tempting to move forward by identifying the sections of the community who we might perceive to be most detached from archaeology, such as the groups of pastoralists, women, or even children, and use archaeology as a tool for intersubjective cohesion. But would this really create a community archaeology, or should we be aiming for community archaeologies? Until further analysis, we feel cautious about prioritizing the vision of one section of any heterogeneous community over another: contested notions of how to allocate resources have a long history of causing conflict both here and across the globe.

Progress

From 2014 to 2016, we made encouraging progress, notably in the increase in the overall number of meeting attendees. The number of women who attended the 2015 meetings and agreed to complete questionnaires increased, as did the number of kinship groups. Several reasons may account for these positive changes. For example, in 2015, a dedicated community engagement officer Bradshaw), was tasked with developing community relationships and organizing meetings. In 2014, the project director (Humphris) had undertaken this role, as an additional task while running the field research project. Thus, in 2014, there had been more limited time to meet and socialize with people, to develop two-way relationships, and to actively advertise the meetings. Additionally, in 2015 the deliberate involvement of pastoral Manasir and Hassaniya groups who live on the village outskirts in Upper Bejrawiya increased the diversity of kinship groups represented at the meetings.

Another development began in 2014 and flourished in 2015, namely the attendance of children at the community meetings (although not as interviewees). At first, we had envisioned our engagement with children to be in a more formal educational format. In part towards this goal, we had produced a five-day community iron smelting festival in 2015 (documented in a film freely available online in English and Arabic, Double and Humphris Citation2015). In the weeks preceding the festival, we canvassed local schools and arranged for primary and secondary schoolchildren to attend, meet the team, have interactive talks, and participate in a Q&A session. In the end, we hosted over 300 schoolchildren and 24 of their teachers. Although we initially discouraged children from attending our other, adult-focused community meetings, it became apparent that this approach was not socially appropriate for a number of reasons: in Sudan, children are usually included in all social events, especially those taking place in semi-domestic settings, as was the case with most of our meetings. Following further consultation with Sudanese colleagues, we began actively to encourage children to attend and learn with their parents. We, therefore, hope that through this extra-curricular learning, younger people can begin to benefit from our meetings and learn how people from different cultures may live and work together.

Lessons learned

Throughout the processes described here, we have learned several lessons. Language continues to be a challenge, with few of the non-Sudanese team members speaking fluent Arabic. This means we are dependent upon Sudanese students and colleagues to deliver the questionnaires and the presentations, and to translate and transcribe the open discussions as they progress; they are also responsible for translating all the questionnaires into English after each meeting. These are significant tasks, requiring the dedication of Sudanese team members with very strong English language skills, willing to work collaboratively to ensure the validity of the translations.

Organizing meetings also posed particular challenges, and relied on the good will of either existing or newly established contacts. The Hamadab Local Committee (the basic unit of state apparatus in rural villages, thus an important local ‘gatekeeping’ institution) as well as several other Ja’aliyin men and women kindly lent us their reception rooms (saloons) as venues for the meetings so that we could use their electricity. However, we notice that this affected the participation of Manasir and Hassaniya residents. Therefore in future, we wish to reduce our reliance upon PowerPoint (and thus electricity) as a means of visual display, so that meetings can be held in electricity-less Manasir and Hassaniya houses. Similarly, we noted that on the occasions where events were not deliberately gender segregated, women did not attend in large numbers. We were not unsurprised by this result, but we had been – and still are – encouraged by some community residents to hold joint meetings. To ‘test’ this, we attempted a number of joint meetings in autumn 2016. Our rationale was that if mixed meetings were successful (as we were assured by some community members that they would be), we would be able to provide a greater number of meetings in each location, and therefore more opportunities for people to attend. However, at the 2016 mixed meetings, again, the female turnout was noticeably low. In contrast, at the segregated events we had more female attendees than male, and the atmosphere was tangibly more relaxed. While it is of course not our default preference for segregation, we will thus continue to keep men’s and women’s meetings separate.

The importance of a continual, critical analysis and constant consideration of ‘how our individual identities affect our work, how we can be changed personally by the work, and how our work can change other people’ (McDavid Citation2007, 73) is essential, to develop new ideas and ways of meeting challenges and to ensure that work is conducted appropriately. Certainly the power of archaeologists to shape and create systems of knowledge and to raise and deploy significant sums of money in resource-scarce areas inevitably leads to their incorporation into power relations (whether these relations exist horizontally, across communities, or vertically, through national and transnational institutions). This requires considerable reflection on the possible impacts of our work (Little and Shackel Citation2014).

Conclusions

This diagnostic study, undertaken to investigate exactly what steps would need to be taken to develop community archaeology around Meroe, has provided important information from which we are developing our future community archaeology strategies. Questionnaire data show that the communities living around the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Royal City of Meroe are heterogeneous, and that an idealized ‘community’ for ‘community archaeology’ does not exist in this context. This diagnostic study, and the engagements described here, helped to identify the complex diversity of the area. Our results demonstrate that there is an interested wider community, keen to learn more, contribute to, and benefit from the development of a tourism sector.

We believe that archaeology can be inclusive, mutually beneficial, and sustainable, and that community research (such as that described here) may help archaeological projects to meet this potential within the diverse contexts of Sudan. We aim to work alongside the National Museum in Khartoum and other relevant heritage organizations to embrace this possibility.

The transition from ‘community engagement’ to ‘community archaeology’ has already begun. In autumn 2016, we held nine community meetings across the same six villages. Each meeting featured an Arabic presentation about the history of the Kingdom of Kush and how people lived during this time, directly addressing the respondents’ stated desire for more information about local history. An additional aim was to promote the sort of sustainability described by Belford (Citation2014, 27). After an update on the project’s results (and our team’s future plans), we held discussion sessions, some of which ran for over two hours. As people discussed current and future plans, their growing knowledge and understanding of our scientific approach to archaeology was reflected in the types of questions they asked the team. These ranged from research-focused enquiries (such as the techniques we use to date archaeological materials) to questions about whether the Meroites used different types of iron ore. Questions extended to broader, ‘heritage’ concerns about the role of museums in Sudan, and how Sudan’s antiquities are protected by international law. Around 300 people attended these meetings, which, we feel, represents solid progress towards developing a sustainable community archaeology effort.

These recent conversations confirm Atalay's (Citation2012) detailed observations about the need to establish solid educational foundations before embarking on participatory practices. The work described here was the first step in developing a long-term programme of capacity building in the Meroe Region.

Ultimately we feel that community engagement and community archaeology should be context-specific. Even though international and cross-cultural critiques and comparisons can be useful, they often do not allow for the diversity of local social, economic, and political situations. Although we feel our first phase, ‘community engagement’ offers a good example, we also recommend that ideally the sorts of ‘engagements’ we described here be conducted parallel to other, more typical archaeological first-steps, such as landscape survey. In this way, the results of both archaeological survey and community survey can help to develop relevant and sustainable archaeological research.

Suggested citation

Humphris, Jane and Rebecca Bradshaw. 2017. ‘Understanding “the Community” before Community Archaeology: A Case Study from Sudan.’ Special Series, African Perspectives on Community Engagement, guest-edited by Peter R. Schmidt. Journal of Community Archaeology and Heritage 4 (3): page 203–217.

Acknowledgements

We first presented this paper at the Society for Africanist Archaeologists (SAfA) conference of 2016 in a session convened by Innocent Pikirayi and Peter Schmidt, ‘Success Stories about Community Archaeology and Heritage in Africa’. We are grateful to Innocent and Peter for their engaged comments on an earlier draft of this paper, and to the editors and reviewers of the Journal of Community Archaeology and Heritage. We thank the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums in Sudan (NCAM), for allowing and supporting this research, and UCL (Beacon Bursary), UCL Qatar and QSAP (Qatar Sudan Archaeology Project) for providing funding which enabled this work or associated work to take place. Many of the UCL Qatar team working in Sudan have played an integral role in implementing the meetings, often late at night during periods of intensive archaeological research. We specifically thank Basil Kamal Bushra and Sayed Ahmed Mokhtar (both University of Khartoum), as well as Abdelhai Abdelsawi Fedlemula (NCAM). Ahmed Hamid Nassr of the University of al Nileen and Abdel Monim Ahmed Abdalla Babiker of the University of Shendi are also specifically thanked for their assistance and support. To all of the other team members who contributed by delivering and translating questionnaires, handing out drinks and biscuits during the meetings, assisting with the meeting setups and taking photographs, we owe you a huge thanks. Meetings would also not have been possible without non-team members such as the local women and imams, who so kindly advertised the meetings for us. We also thank Paul Belford and Stavroula Golfomitsou for offering comments on an earlier draft of this paper. We would like to finally thank all of the local community members who, some with amusement and some with curiosity, gave their time to attend the meetings and provide input through the discussions and questionnaires. We thank you for your trust and hope we can meet your expectations in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributors

Jane Humphris is a Principal Research Associate at University College London (UCL) Qatar. She holds a PhD in African Archaeometallurgy and an MA in African Archaeology from UCL, UK, and a BA in Ancient History and Archaeology from the University of Manchester, UK. Jane’s research in Sudan focuses mainly on ancient iron production associated with the Kingdom of Kush. Alongside the research, she runs a community engagement and capacity building programme, which involves meetings, interviews and lectures, as well as training Sudanese students.

Rebecca Bradshaw has submitted her PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, UK, in which she examines the political and economic impact of archaeology in Sudan. She also holds an MPhil in Egyptology from the University of Cambridge and a BA in Ancient History from the University of Warwick. She has worked extensively in Sudan, with teams from UCL Qatar and the British Museum, and has also helped to spearhead archaeological and anthropological investigations in Egypt and Iraqi Kurdistan.

References

- Atalay, Sonya. 2012. Community-Based Archaeology: Research With, By, and For Indigenous and Local Communities. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bartoy, Kevin M. 2012. “Teaching Through, Rather Than About. Education in the Context of Public Archaeology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Archaeology, edited by Robin Skeates, John Carman, and Carol McDavid, 552–565. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Belford, Paul. 2014. “Sustainability in Community Archaeology.” Online Journal in Public Archaeology SV 1: 21–44.

- Boddy, Janice. 1989. Wombs and Alien Spirits: Women, Men and The Zār Cult In Northern Sudan. Madison: New Directions In Anthropological Writing, University of Wisconsin Press.

- Bruce, James. 1790. Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile in the Years 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772, and 1773. Edinburgh: G.G.J. and J. Robinson.

- Cailliaud, Frédéric, and Edme-François Jomard. 1826. Voyage À Méroé, Au Fleuve Blanc, Au-delà De Fâzoql Dans Le Midi Du Royaume De Sennâr, À Syouah Et Dans Cinq Autres Oasis, Fait Dans Les Années 1819, 1820, 1821 Et 1822. Paris: Imprimerie Royale.

- Double, Graham (Director), and Jane Humphris (Producer). 2015. “Ancient Iron, Experimental Archaeology in Sudan.” film available in English and Arabic. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SPU8Uwa-jBQ (English) and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PBCrKLx0R0I (Arabic).

- Edwards, David. 2004. “History, Archaeology and Nubian Identities in the Middle Nile.” In African Historical Archaeologies, edited by Paul J. Lane and Andrew M. Reid, 33–59. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Hänsch, Valerie. 2012. “Chronology of a Displacement: The Drowning of the Manāsȋr People.” Meroitica 26: 179–228.

- Hopkins, Nicholas S., and Sohair R. Mehanna. 2010. Nubian Encounters: The Story of the Nubian Ethnological Survey, 1961–1964. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- Lane, Paul. 2011. “Possibilities for a Postcolonial Archaeology in sub-Saharan Africa: Indigenous and Usable Pasts.” World Archaeology 43 (1): 7–25. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2011.544886

- Linke, Janka. 2014. “Oil, Water and Agriculture: Chinese Impact on Sudanese Land Use.” In Disrupting Territories: Land, Commodification and Conflict in Sudan, edited by Jörg Gertel, Richard Rottenburg, and Sandra Calkins, 77–101. Rochester, NY: Boydell and Brewer.

- Little, Barbara J. 2012. “Public Benefits of Public Archaeology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Archaeology, edited by Robin Skeates, John Carman, and Carol McDavid, 395–409. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Little, Barbara J., and Paul A. Shackel, eds. 2014. Archaeology, Heritage, and Civil Engagement. Working Towards the Public Good. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- McDavid, Carol. 2007. “Beyond Strategy and Good Intentions: Archaeology, Race and White Privilege.” In Archaeology as a Tool of Civic Engagement, edited by Barbara J. Little and Paul A. Shackel, 67–88. Lanham: Altamira Press.

- Meskell, Lynn. 2005. “Archaeological Ethnography: Conversations Around Kruger National Park.” Archaeologies 1 (1): 81–100. doi: 10.1007/s11759-005-0010-x

- Näser, Claudia, and Cornelia Kleinitz, eds. 2012. “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: A Case Study on the Politicisation of Archaeology and Its Consequences from Northern Sudan.” Meroitica 26: 269–304.

- Pikirayi, Innocent, and Peter Schmidt. 2016. “Introduction.” In Community Archaeology and Heritage in Africa: Decolonising Practice, edited by Peter Schmidt and Innocent Pikirayi, 1–20. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

- Richardson, Lorna-Jane, and Jamie Almansa-Sánchez. 2015. “Do You Even Know What Public Archaeology Is? Trends, Theory, Practice, Ethics.” World Archaeology 47 (2): 194–211. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2015.1017599

- Säve-Söderbergh, Torgny. 1987. Temples and Tombs of Ancient Nubia: The International Rescue Campaign at Abu Simbel, Philae, and Other Sites. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Schmidt, Peter. 2016. “Collaborative Archaeology and Heritage in Africa, Views From the Trench and Beyond.” In Community Archaeology and Heritage in Africa: Decolonising Practice, edited by Peter Schmidt and Innocent Pikirayi, 70–90. Oxon: Routledge.

- Shinnie, Peter. 1967. Meroe: A Civilization of the Sudan. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Smith, Laurajane, and Emma Waterton. 2009. Heritage, Communities and Archaeology. London: Duckworth.

- Starzman, Maria Theresia. 2012. “Archaeological Fieldwork in the Middle East: Academic Agendas, Labour Politics and Neo-Colonialism.” In European Archaeology Abroad: Global Settings, Comparative Perspectives, edited by Sjoerd. J. van der Linde, Monique. H. van de Dries, Nathan Schlanger, and Corijanne. G. Slappendel, 401–415. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Straight, Bilinda, Paul. J. Lane, Charles. E. Hilton, and Musa Letua. 2015. “It Was Maendeleo That Removed Them’: Disturbing Burials and Reciprocal Knowledge Production in a Context of Collaborative Archaeology.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 21: 391–418. doi: 10.1111/1467-9655.12212

- Török, László. 2015. The Periods of Kushite History from the Tenth Century BC to the Fourth Century AD. Studia Aegyptiaca Supplements 1. Budapest: Izisz Foundation.

- Umbadda, Siddig. 2014. “Agricultural Investment Through Land Grabbing in Sudan.” In Disrupting Territories: Land, Commodification and Conflict in Sudan, edited by Jörg Gertel, Richard Rottenburg, and Sandra Calkins, 31–51. Rochester, NY: Boydell and Brewer.

- World Bank. 2011. “A poverty profile for the northern states of Sudan.” The World Bank Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit, Africa Region: p. 2. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTAFRICA/Resources/257994-1348760177420/-2011.pdf.