ABSTRACT

Co-production of community heritage research is in the ascendant. Co-production aims to break down barriers between ‘experts’ and the ‘public’ to co-create knowledge about the past. Few projects have sought to critically evaluate the complexities of co-producing research, particularly long-term ones, composed of multiple activities, which draw on differently situated groups. This paper presents a reflective analysis by the university-based participants of a long-standing community heritage project focusing on the ruins of a locally celebrated crofting community in Northeast Scotland. The use of archaeological and archival techniques, the creation of an exhibition, a kitchen garden, promenade drama, a heritage app, and publications, provide both opportunities and challenges for co-production. The meaning of co-production was shaped by the nature of research activities, resulting in significantly varied levels of participation; its embedding, therefore, requires managing expectations. Effective relationships for co-creating knowledge are an outgrowth of building trust, which take time, patience, and commitment.

Introduction

Community heritage research is all the rage. A google search of the term returns thousands of hits. Although community heritage – as an activity – has a respectable pedigree, its recent courting by centres of higher education and its reframing as ‘research’, has fundamentally altered its practice. Today, academics are asked to engage ‘communities’ in the undertaking of a wide range of projects linked to local and regional heritage. Whereas initial attempts at doing community heritage often had limited success in actively involving ‘the community' (Simpson and Williams Citation2008), recent calls for ‘co-produced’ research have altered the discourse (Graham and Vergunst Citation2019). Co-production aims to break down the barriers between ‘experts’ and ‘the public’ by changing the hierarchical relationships between them. If academics are popularly viewed as knowledge producers and the public as knowledge consumers, then the purpose is to take the creation of knowledge out of the ‘ivory tower’ of academia and to encourage more collaborative forms of creating and knowing. The logic of co-production is increasingly favoured by research councils to facilitate engagement and evidenced-based collaborations. Given their dependency on public funding bodies, community heritage research projects now commonly aim to underscore their credentials as having been ‘co-produced’. Despite the importance of these terms in public policy, few projects have sought to critically evaluate the complexities within such research arrangements (though see Straight et al. Citation2015, 393; Facer and Pahl Citation2017a, 1), particularly those that are long term, composed of multiple and complementary activities and which draw on different groups of people. Understanding the nature of co-production and the communities it affects can mean different things in different places. Context is everything.

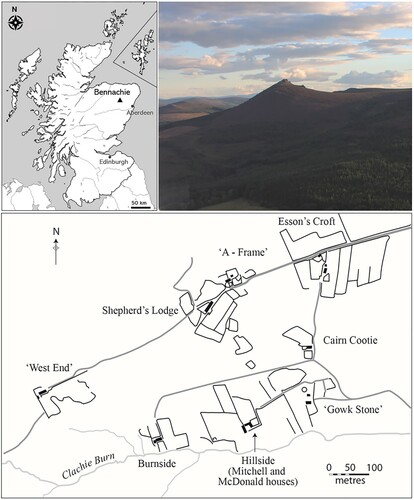

In this paper, we reflect on our personal experiences of community heritage research to discuss what we learnt about co-production as part of the Bennachie Landscapes Project (BLP). The hill of Bennachie is North East Scotland’s most iconic landmark: its heather-clad granite peaks provide a striking backdrop to the undulating pastoral and arable lowlands for miles around. Within this wider setting, the hillside ruins of the Colony – an improvised nineteenth century crofting settlement – provide a focal point to discuss our involvement in a programme of community archaeology, archives and outreach and to critically reflect on co-producing knowledge about the settlement’s past with a variety of stakeholders. Our principal aim is to offer a ‘rich description’ of the research process. In particular, we are concerned with articulating the sorts of relationships that defined our collaboration, how they enabled or conditioned participation and how different actors contributed within a research programme that has involved a range of organizations as well as sites of co-production. In short, we want to unpack what co-production means in practice.

We are also aware that certain factors that helped to give shape to the project affect this further. Multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary working practices, concerns about the nature of academic expertise along with the pressures of working within a university-funded research culture all condition what is achievable and what we have achieved. While the Bennachie Colony has remained an important anchor and reference point, the development of the project over subsequent years has helped to bring in new actors, new activities, new goals and new sites of co-production, presenting significant problems for those looking for tidy answers to questions about social impact, or exactly what ‘community’ it has served. Indeed, we are of the opinion that co-production can do more than just create skills or knowledge; it can be the very glue that creates community. In closing, we offer a set of observations derived from our own experience that may be relevant to researchers and community groups embarking on their own adventures of co-production.

Defining co-production and the community

The term co-production has its origins in debates around public service delivery (Stephens, Ryan-Collins, and Boyle Citation2008). Through its incorporation into university disciplines, co-production has come to signify a mode of co-operation, in which the activities that define research, such as planning and design, methods, analysis and the creation of facts or ideas, are dispersed beyond standard academic roles. Research informants, communities, partner organizations and others may be involved throughout. Jones et al. write that co-production methodologies ‘are intended to decentre traditional relationships of power, control and expertise between researchers and volunteers, or “professionals” and “non-professionals”’ (Citation2018, 337). A key issue is ensuring that community members have greater decision-making capacity. Freire (Citation2001) provides a framework that enables us to theorize how this happens. His conceptualization of the role of experts and learners forces us to confront the idea that ‘whoever teaches learns in the act of teaching and whoever learns teaches in the act of learning’. While a common thread in such thinking stresses shared responsibility and emphasizes the democratization of research, critical reflection often reveals more complicated relationships are possible, if not likely. As Sarah Byrne (Citation2012, 27) points out, the relationship between the way experts and non-experts are positioned may not be a static phenomenon and may change significantly over the lifespan of a project (cf. Hart Citation1997).

One reason co-production as a concept is valuable here (as opposed to a word like collaboration) is because it draws attention to the processes and dynamics of research (cf Johnston and Marwood Citation2017). It is part of a wider lexicon that describes how research can be carried out ‘socially’ by means of diverse networks and partnerships, which also includes community engagement (Waterton and Watson Citation2011), collaboration (Lassiter Citation2005; Facer and Pahl Citation2017b), interdisciplinarity (Klein Citation1990; Oliver Citation2020) and the field of Participatory Action Research (Kindon, Pain, and Kesby Citation2007), amongst others. Without wanting to rank these approaches, our emphasis on co-production draws attention to the performative quality of doing research as part of a collective made real through working together on activities that have productive outcomes.

If arriving at a satisfactory definition of co-production poses issues, the term ‘community’ raises further problems. The Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Connected Communities programme claims that ‘we all belong to communities – at home, in our neighbourhoods, at work, at school, through voluntary work, through online networks, and so on’ (AHRC Citationn.d., 1). Although hard to define and easy to contest, the idea of ‘community’ brings with it a series of expectations. The most basic of these is the identification of a group of people with a shared identity. In many cases, they are assumed to be spatially defined through sharing a geographical locale. Others are communities of interest that can be widely dispersed, sharing in the undertaking of common goals, to the extent of worldwide online communities. In many community heritage projects, ‘the community’ is taken for granted. Others have recognized that communities are dynamic, effected by variables from geography and history to issues of power and practice, meaning that they are apt to change (Bauman Citation2001; Wenger Citation1999). Dewey argues for a dynamic view of community in which ‘community’ is always under construction (Noddings Citation2016, 176). As academic researchers, we are often invited to partner with ‘community/ies’ and then left to identify who that community is, who is included, and by definition, who is excluded. A more dynamic view, which acknowledges the ‘under construction’ element, allows people to have greater agency in identifying themselves as part of these configurations.

However ‘nebulous in its detail’, the word ‘community’ is nevertheless ‘highly suggestive in its abstraction’ (Contier Citation2015, 244) being frequently used in official discourse with a very positive aura. As Bauman (Citation2001, 1) notes, while all words have meanings, ‘some words, however, also have a feel. The word “community” is one of them. It feels good’. As if summarizing the general consensus around this feel-good term, the AHRC claims that ‘communities are vital to our lives and wellbeing’. Delanty has argued that ‘community’ has this resonance because it embodies direct relationships between people in contrast to the more distanced connections established between society and the state. As such, ‘the quest for community is seen as something that has been lost with modernity and that it must be recovered’ (Delanty Citation2003, 10). It is, therefore, simultaneously utopian and nostalgic.

At the same time, the use of ‘community’ in official discourse can also bring with it additional baggage. Often it is seen as ‘a label given to those who cannot, cannot yet, or will not assimilate and integrate into the officially encouraged order’ (Contier Citation2015, 246). This leads to many projects assuming a ‘deficit model’ whereby co-production is intended as a means of improving an otherwise passive community unable to help themselves, a position that also implies that academics stand outside of ‘the community’ or have little to learn.

What we take from this discussion is that usefulness of terms like community and co-production will not emerge by agreeing narrow definitions up front and then making judgements about whether circumstances fit them. Their usage is instead an invitation to explore more diverse and subtle dynamics of social relationships in a reflexive mode. This means being attentive to how communities of practice (or of interest, place, etc.) form and sustain themselves, and how research is imagined and improvised by all participants. Here we do not assume from the start the value of collaborative research as a ‘goal’ to be ‘achieved’, but instead use our engagement to reflect on the process and outcomes of research. Ultimately, we return to these concepts in our discussion, commenting on how expanding our expectations can improve both the planning of projects and their outcomes.

Contextualizing the Bennachie Landscapes Project and its unfolding

The project begins with a place – a storied landscape – and a collection of researchers who were inspired to work together. The place is the ruins of the Colony; an improvised crofting settlement established in the early nineteenth century on Aberdeenshire’s most recognized landform: the hill of Bennachie. Today its drystone dykes and tumbled-down cottages litter the eastern flank of the hill (). Folk memories of the Colony tend to focus on stories of social tension between its crofter colonists and landed interests, accounts that are shaped by more than a century of retelling. Much of what we know of the Colony relates to popular discourses of rural living, its injustices, its heroic common people who toiled in the earth. It is these stereotyped understandings of Scotland’s rural past that helped to bring together a community of researchers to learn more about the social and material history of the hillside, to ‘test’ its popular mythologies and to place the colony within a wider historical context (Oliver et al. Citation2016). Academic members of our team brought together six disciplines from the University of Aberdeen. This included anthropology, archaeology, geography, history, education and museums along with an established community group: The Bailies of Bennachie. Founded in 1973, the ‘Bailies’ are drawn from the wider North-East of Scotland. A Bennachie ‘diaspora’, derived from nineteenth and twentieth century migration, includes members as far away as New Zealand, Australia and Canada (Fagen Citation2011). While membership is without geographical limits, it nevertheless is premised on an intense relationship with the hill of Bennachie that focuses on conservation and educating the public about its natural and cultural dimensions.

Many community heritage research projects originate with an academic grant and university-based researchers in search of a community. The BLP has a curious ‘prehistory’ because it turns this relationship on its head. Our collaboration began with Bailies inviting us – a group of university-based researchers with previous interest in the hill – to undertake a ‘community project’ with them. (The irony of having been ‘engaged’ by a community organization we feel is significant and has not been lost on us).

Beyond a shared concern to ‘dig’ into the Colony’s past, the project has more diverse motivations. One set stemmed from an interest in the archaeology and archival history of the Colony and what it could contribute to wider understandings of nineteenth century crofting, abandonment, and rural life in northern Scotland more generally. From this perspective, the idea of a community project was a means to an end. Others were more focused on understanding the social aspects of a collaborative project, notably questions surrounding how to widen our engagement with the public beyond the Bailies and how collaboration might actually work in practice (cf. Davis et al. Citation2019; Johnson and Simpson Citation2013). While membership of this group has been fluid over the years and has coalesced around a range of evolving activities, what has given it an important degree of coherency is in the doing of heritage research (Wenger Citation1999).

The award of an AHRC Connected Communities grant in 2011 put the project into motion by funding a series of community events designed by the academic researchers around different subject specialisms. These included archaeological shovel test-pitting the abandoned fields of the Colony; archival research using the University’s collections; and oral history events at the Bennachie Centre. It was not until the awarding of an AHRC development grant in 2013, that we began to formally reflect on the idea of co-production, how knowledge about the past might be co-created and how this might influence the direction of our research. Key activities included a set-piece archaeological excavation, the use of local archives and extending research opportunities to local schools. The fruits of our collaboration were to be drawn into an exhibition along with more traditional publications. Additional co-written grants in 2017 (from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) and AHRC) provided the stimulus to bring the significance of the colony to a wider audience. A series of new co-designed activities, from the development of a promenade drama to the creation of a heritage app, were undertaken to help democratize interpretation beyond our local contacts.

In what follows, we trace the evolution of the project through the different activities that have served to give it structure. In particular, we aim to shed light on the different relationships that were formed and subsequently transformed through the experience of doing research.

Archaeological fieldwork

The presence of archaeology on the hillside is well established (Bogdan et al. Citation2000). However, its character and extent were less certain. In 2010, the Bailies, led by independent archaeologist Colin Shepherd, began a co-ordinated strategy to record the cultural legacy of the hill. Our involvement aimed to build on these efforts.

A number of techniques have been used to record the archaeology over the course of the project. A key emphasis has been the use of relatively ‘low-tech’ procedures because the skills required can be learnt relatively quickly. This included shovel test-pitting for artefacts in the abandoned fields of the settlement; the use of off-set and plane table surveys (see RCAHMS Citation2011) to produce a detailed plan showing its dwellings, outbuildings, kailyards and associated trackways; and undertaking a controlled excavation of two Colony crofts (Oliver et al. Citation2016). Reflecting on how these techniques invited participation with the community collaborators helps us to begin to understand what co-production of research really means. While most participants had limited encounters with archaeological field techniques, a small group already possessed significant field experience and were instrumental in teaching skills to others.

Shovel test-pitting has been employed over the duration of the project. It is quick and expedient for obtaining datable artefacts, such as decorated ceramics, but it is also easy to learn and is an effective tool in the hand of volunteers with limited experience. Considering that popular views of the discipline tend to associate it with digging up the past buried beneath our feet (Holtorf Citation2005), test-pitting may have fulfilled some of the expectations of first-time participants for doing archaeology. What is more, because participants can quickly become independent, it can absorb large numbers of volunteers with limited supervision. Some of our shovel test-pitting weekend events attracted upwards of thirty or forty people, helping to fulfil our more basic goals of opening the door to wider participation. The positive results of test-pitting at the Colony, which revealed nineteenth-century ceramics, glass, and metal artefacts (Oliver et al. Citation2013), encouraged the establishment of a number of ‘spin-off’ digs around the Hill of Bennachie at comparable sites. Here the focus was on test-pitting with school groups and engaging them in the co-creation of artefact displays.

The creation of a detailed plan of the Colony ruins using plane table survey set new conditions reconfiguring our relations of co-production. The technical demands are somewhat higher than test-pitting as they require patience and competence with the use of survey tapes, plane tables and stadia rods. These factors tended to limit participation compared with test-pitting. While planning is sometimes seen as a method for the objective recording of archaeological features, it is also about exploring the landscape, about dialogue and decision-making. What to record and what to ignore? Attentive volunteers, even novices, can rapidly become active participants in discussions that transform ambiguity into the object of our attention. With experience comes confidence. In this context, the dividing line between ‘expert’ and ‘novice’ can blur into a range of values shaped by previous experience, reflecting Freire’s argument that teaching is not to transfer knowledge, but to create the possibilities for the production of it (Freire Citation2001). Participants not only gained skills as part of the process of discovery, they also developed trust and the ability to share knowledge, setting the groundwork for future activities.

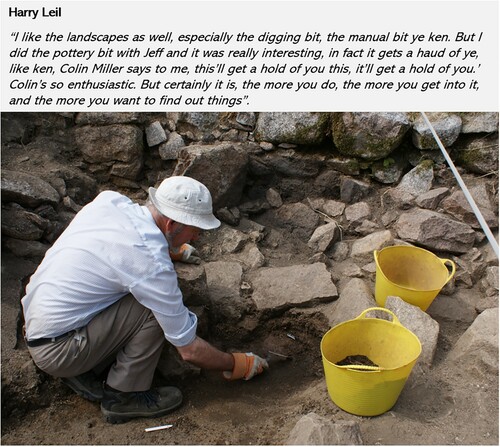

In the summer of 2013, we undertook excavations of two crofts: the McDonald House and Shepherd’s Lodge. Excavation, like archaeological survey, required the establishment of a more intimate team. Digging itself is not onerous for a fit adult, though the technical demands of recording and interpreting remains are such that the professional archaeologists played an important oversight role and were responsible for most high-level decisions, such as working out site stratigraphy. This aspect of the fieldwork, therefore, maintained the more typical relationship seen between ‘experts’ and ‘volunteers’ rather than the democratic one commonly envisaged by ‘co-production’. While traditional hierarchies were harder to shift, a core of the participants developed degrees of expertise that helped shape their identities within the wider group (). For example, some of the regulars – notably Bailies who had engaged the academic membership from the start – took charge of working out an efficient system to remove the heavy granite building rubble from the cottage interiors. Drawing on their knowledge of historic quarrying activities on the hill, the answer came in the form of a traditional ‘bier’: a stretcher of logs tied with rope.

Archival research

The tangible remains of the Colony lent the project a strong archaeological identity, but, from the beginning, our project design recognized the importance of archival history to our overall success. Early meetings with the Bailies centred on the nature and definition of various types of ‘archive’. Focus initially was on the Bailies’ own archive of organizational papers, collections of press clippings and photographic prints and the question of how these might be organized, catalogued and studied. The dialogue with the academic historians encouraged broadening this conversation to consider the scope for investigation of other archives, including the University of Aberdeen’s Special Collections Centre (SCC) with its extensive collections on the wider region. Our community engagement in this context involved opening and pursuing conversations around the public understanding of archives, promoting awareness about access, and the character of archival records.

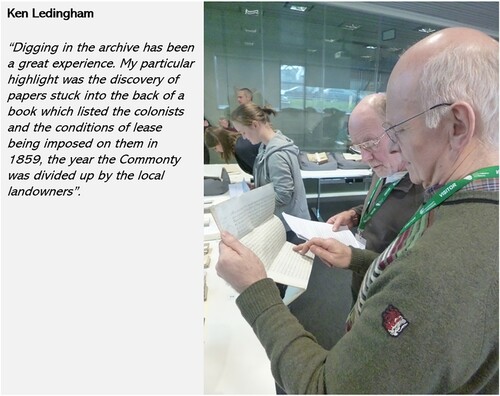

Our research unfolded over a number of stages. Each was shaped by different contributors, with early stages being dominated by the professional archivists of the SCC and historians while later stages were increasingly led by the community researchers. Initial meetings with the professional archivists covered issues like the identification of relevant collections, such as estate records, and concerns around conservation and access. In a second stage the academic historians, led by Jackson Armstrong, invested significant preparatory time ‘behind the scenes’ to identify relevant boxes, bundles and documents of interest. This included, for example, medieval documents from the Arbuthnott papers (AUL MS Citation2764), eighteenth- and nineteenth-century documents from Davidson & Garden solicitors’ papers (AUL MS Citation3744), and the diary of local farmer John Dickie (Harper Citation2012). The historians also identified other accessible collections available in digital format (e.g. newspaper and census records). Preparation also included coordination for initial group visits by the Bailies to introduce them to the SCC and the range of materials of potential significance to the Colony. Once this preparatory work had been completed, community researchers worked without professional support. The range of experience, authority and capabilities of the Bailies that chose to participate in the archival work resulted in five partners coming forward to study a range of records. Even within this group, there was a diversity of approach; some preferred to work with digital newspapers and census records, others regularly used the physical archival collections held in the SCC. This appeared to be driven by the interests and motivations of participants as they contributed to the wider project. It was notable that some of the most active researchers were engaged in a range of activities across the project beyond the archives.

The outcomes of the archival research were occasionally unexpected and overwhelmingly significant for the historical research findings. The volume and quality of information that was gathered through this work is to some extent a reflection of the particular strengths of the Bailies as a community organization whose members are often of working age or recently retired, and from backgrounds where degree-level education or employment in a professional field is common. Unlike some of the archaeological fieldwork with its various technical demands, it is worth noting how skills developed outside of the project were able to be adapted and put to use in making the archival research a more autonomous form of engagement. The archival investigations were crucial in helping to widen our understanding of the historical context of the Colony, and included specific discoveries about some of the identities of the colonists and their improvements to the hillside which would later be actively compared with the archaeological remains (Armstrong, Miller, and Oliver Citation2015) (). These findings not only helped to provide the project with a further angle of intellectual momentum but also enabled later phases of work, including the creation of exhibitions and the drafting of publications.

Interpretation

Imagining the sorts of interpretations the project would create – ‘outputs’ in the dry language of research accountability – was an evolutionary process. Initial funding applications tended to separate community engagement activities from the process of interpretation. The former was about getting people involved, the latter was the domain of academic interest. With the fullness of time, a more complex and multifaceted approach emerged: collaborative acts of interpretation in the field and archives set the stage for later phases of writing and interpretive expression.

Interpretation is an often-neglected subject. While it is sometimes assumed that the evidence speaks for itself, good researchers know that convincing interpretations are born out of working with the evidence, asking questions of it and thinking about possibilities through dialogue with others. Although it is easy to see in hindsight how interpretation unfolded, it was more difficult to spot in the moment. This is because it was caught up with a range of other activities and conversations in the field and archive; a situation that was much facilitated by the fact that membership of these workgroups was composed of relatively stable, close-knit teams formed over months and even years. As the idea of co-produced interpretation bedded into our group psyche, the experience of creating an exhibition about the Colony in 2014 formed an important awareness threshold for recognizing the role that different styles of co-produced interpretation could play and the different groups it could speak to. Mindfulness of what Silliman (Citation2008) calls ‘collaboration at the trowels edge’, also began to filter into the groundwork and writing our popular and academic publications.

With a raised awareness of the power of co-produced interpretation, the project identified a need to make our research findings of interest to wider audiences and to democratize participation. To accommodate these aims new interpretive projects were devised to focus on three, potentially overlapping, audiences: (i) frequent visitors to the hill who may already be participating, but might like to deepen their involvement; (ii) an audience that is interested in reading about our work – a group that potentially includes academics – and; (iii) potential new audiences, particularly those outwith the generally middle-aged and middle class characteristics of the first two groups.

Pop-up exhibition

Our original project proposal promised ‘a co-produced exhibition at the Bennachie Centre’ intended to ‘showcase the project results’ (Oliver et al. Citation2012). The idea called for the display of archaeological finds in glass cases supported by interpretive text – a plan supported by many of the participants. Neil Curtis, as head of University museums at Aberdeen, was initially seen as bringing technical expertise to this enterprise. However, early discussions about the form of the exhibitions raised a number of issues. The first were the limitations posed by a fixed exhibition suitable only for visitors to the hill. The second was that the project was not completed: it was hoped that the exhibition would be a catalyst to encourage new participants. These observations resulted in some unanticipated outcomes. Rather than a typical engagement activity composed by university members engaging community members to create an exhibition, the project group (University members, Bailies and other participants) began to see itself as an insider community wishing to involve wider audiences.

The contribution of a professional designer on the team, Vi Peterson, meant that the project group could see what ideas would look like as professionally rendered images and text. Professional input from outside the university also helped the group to cohere further, as the distinction between ‘community’ and ‘university’ identities was levelled in favour of recognizing the different skills that people brought to the table. In the event, Curtis’s role as technical advisor dramatically shifted to one of leading discussions about the purpose of the display, helping the group to think about its intended audiences and how authorship and voice were to be acknowledged (Smith Citation2006). To reach new audiences, the exhibition plans coalesced around a preference for mobile ‘pop-up’ banners for display in the Bennachie Centre as well as libraries, cafes, community centres and churches across the region. With an ‘output’ agreed, a smaller committed team came together at the Bennachie Centre on chilly evenings in the winter of 2013–2014 to bring the concept to reality.

Writing exhibition text was a new experience for most involved. Initial drafting of ideas could be emotionally challenging as the team, sometimes ruthlessly, edited each other’s texts. Nonetheless, this remained a friendly and constructive ‘give and take’ due to our long discussions about the aims and audiences. In many cases, the drafting and sharing of text enabled imaginative ideas to be floated and openly discussed, alongside the ‘hard’ evidence of our discoveries.

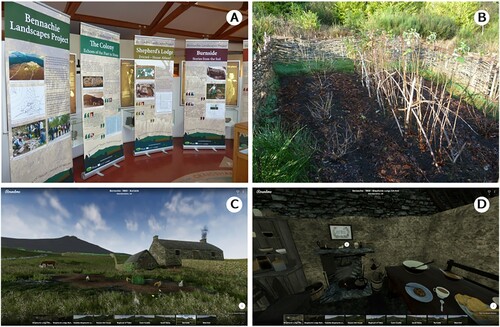

We decided that most of the banners should take a single location in the Colony as their topic: places where we had invested something of ourselves. They used photographs, plans, quotes and interpretive text to highlight our research discoveries along with the contribution of project members. For example, a banner depicting the house known as Shepherd’s Lodge using the sub-title ‘Evicted – House Ablaze?’ presented our archaeological and archival evidence to address a popular (but ultimately apocryphal) story of the house having been set ablaze to evict the tenant. To communicate our aims of inclusiveness, writing emphasized the first person, and was accompanied by illustrations of volunteers and quotes expressing their thoughts. Six years later, thanks to the committed efforts of participants, the pop-up banners continue to travel the Northeast of Scotland ((a)).

Figure 4. (a) Pop-up exhibition banners on display at the Bennachie Centre. Photo provided by Chris Foster. (b) The kailyard at Shepherd’s Lodge. Photo provided by Chris Foster (c) A still of the interpretation of the interior of Shepherd’s Lodge. (d) A still of the interpretation of Burnside Croft.

It is interesting to reflect on how discussions about the form of the exhibition ultimately influenced the nature of its co-production. While Curtis’ role as a museum professional was significant in helping the group to identify its purpose, once established, this role faded into the background. On one level we can make comparisons with archival research. Even though most participants had no previous experience, the typical professional backgrounds of the participants, combined with the Bailies’ aim of opening up participation, ensured a team effort in producing museum-quality banners that would appeal to a wider community. The success of this approach has led to the co-curation of exhibitions, where museum staff work hand in hand with those who bring specialist knowledge (whether students, academics or other community members), becoming the norm in the university’s Museums & Special Collections.

Publication

The mark of a successful project has conventionally been the creation of popular and academic ‘outputs’. Given the more significant challenges around writing with a large group, not to mention the specialist knowledge and writing skills required (Johnson and Simpson Citation2013, 61), community heritage projects have tended to avoid community-authored works, instead favouring practical forms of engagement that absorb many hands (but see for example Davis et al. Citation2019; Hale et al. Citation2017). Where publication is desired or required, writing is usually undertaken by a small number of ‘experts’, often professionals, and may, therefore, lack the forms of collaboration one might expect to be ‘co-produced’. The Bennachie Landscapes Project, however, has benefited from a number of factors that have enabled examples of collaborative writing. First, publication was encouraged and facilitated from an early stage, with the Bailies publishing their own book series Society and Ecology in North East Scotland, under the careful editorship of Colin Shepherd. Second, is the profile of the landscapes group. For many of the Bailies, writing skills have been supported by careers or educational experiences where this was a necessity, even though academic publication was new to most. Third, the long lifespan of the project has meant that participants were able to discuss, develop and execute writing projects within a supportive environment, outcomes that would be a challenge to nurture in short-term projects.

The particular configuration of the project in terms of skills and resources available has enabled a relatively high proportion of the (non-academic) community members to write single-authored and occasionally co-authored articles published under the cover of the Bailies own publication series (see chapters in Shepherd Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2018, etc.) local society magazines (Foster Citation2014; Kennedy Citation2014; Ledingham Citation2014) and peer-reviewed journals (Miller Citation2015; Armstrong, Miller, and Oliver Citation2015). The same skills have enabled non-university members of the group to share their research ideas at community heritage and academic conferences. This is not to say that publication falls neatly into a co-produced model. As more individualistic activities, our publications have tended to offer just that, personal perspectives on a variety of historic, geographical and environmental phenomena. That said, the fact that collaboration in the field or archive helped to provide grounding, and sometimes crucial observations for these more individual pursuits, should not be forgotten. We return to the complexities around authorship and its tensions with co-production in the discussion.

Place, interpretation and expanding participation

Participants within the Bennachie Landscapes Project have frequently been concerned with the wider reach of the project. While the landscapes group has been anything but static, the aim was always to encourage a larger, more diverse participation, and for the work to reach as broad an audience as possible, notably the imaginations of those less willing to read publications and view exhibitions. This signalled not only a greater commitment to multivocality, but also a renewed awareness about how being involved in the research would help create and sustain relationships between people and the landscape more broadly. These aims were further shaped by an awareness that the nature of collaboration between the Bailies and University was becoming more structurally horizontal. In part, this was the result of close collaboration resulting in people working as peers, and partly the recognition of the prior skills, experience and planning that were brought to the collaboration.

The most recent phases of the project have been marked by the levelling of hierarchies, greater group cohesion and the creation of a joint vision in terms of how the project has evolved. The securing of funding from the HLF by the Bailies in 2017 was used to visually interpret the Colony in ways that would connect with new groups. The grant allowed this to be explored through a number of new projects: (i) the creation of a digital app for mobile devices on the history of the Colony based on the research of the BLP (supported through the creation of an online archive); (ii) the recreation of a kailyard (kitchen garden) at one of the crofts, and (iii) the planting of native tree species to recreate aspects of the historic environment. A second AHRC grant awarded the same year concentrated on democratizing the process of interpretation. In order to avoid singular, authoritative narratives it would help participants to explore the history of the Colony and its former residents through storytelling, creative writing and a promenade drama. What unites the projects is their focus on sensory interpretation: bringing the Colony and its surrounds alive to the senses.

To bring life back to the ruins of the Colony, the drystone-walled kailyard adjacent Shepherd Lodge, one of the oldest crofts, was planted with gooseberries, currants and raspberries, which project research had identified as being locally available to the nineteenth-century crofters. Subsequent seasons of planting, weeding and general upkeep has produced a flourishing garden alongside one of the principal Colony footpaths ((b)). Beyond the kailyard, a native woodland has been planted, known among the Bailies as the ‘foraging forest’.

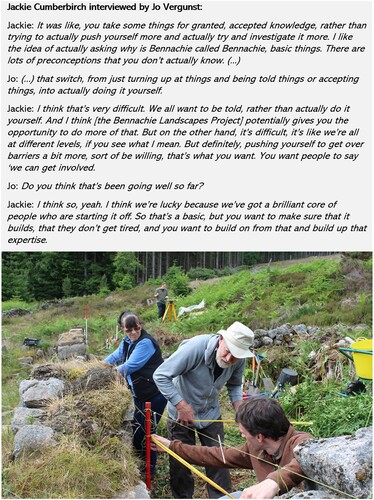

The idea to use the Colony as a stage for community arts was influenced by the assumption that different audiences would respond distinctly to different styles of interpretation. Some of the groups we attempted to attract included the growing Polish expat community – ‘New Scots’ – and others such as Scottish Travellers. A prominent stimulus came from the Senior Bailie, Jackie Cumberbirch’s prior experience of the arts. At the same time, Liz Curtis’s strong social networks among local musical and song and dance groups was influential in recruiting the artists – notably storyteller Grace Banks who brought her own ties with local performing groups. Weekend events, including workshops organized by Polish writer, Kasia Maziarka, and the Polish-Scottish Song and Story Group, drew in non-traditional audiences to create songs and stories that drew inspiration from Bennachie and from the Colony. Our attempt to reach new audiences culminated in the production of a promenade drama focusing on some of the better-known Colony personalities. The production saw visitors guided between the ruins of former crofts where they were entertained with theatrical sketches about the lives of the Crofters – such as the dramatic 1878 expulsion of residents upon their inability to pay rent (Fagen Citation2011, 7).

If the kailyard and artistic performances expanded the Colony’s appeal to alternative audiences, the design of the Bennachie Colony digital app was sought to provide a more dynamic and culturally relevant means through which to reach younger visitors. Meetings with a youth group, the Inverurie Youth Forum, helped to outline key features that might appeal to younger audiences, while the technical aspects of design and implementation were handled by Smart History, a group of academics and tech specialists from the University of St Andrews. A series of workshops provided the main stimulus for making decisions about design and content which drew from our collective explorations – from archaeological and archival discoveries to the use of clips from the promenade drama. Our ambition was for the app to reanimate the ruins of the colony using virtual reality simulations of the dwellings, and through our collected stories about the families that once called the hillside home ((c,d)). Upon its release in 2018, the Digital Bennachie Colony Trail (Bailies of Bennachie Citationn.d.) was quickly adopted by the Aberdeenshire Council Ranger Service for visiting school groups. According to one ranger, the app’s visual simulations challenge children to appreciate the historic natural environment of Bennachie. Today the hillside is a densely wooded plantation, but in the time of the Colony it was dominated by heather and grasses, which the app invites visitors to see.

Opening up the Colony to different modalities of interpretation represents an important threshold for the project: where earlier funded phases were often led by academics, the role of the Bailies has become central to decision-making about funding applications. If our initial research collaboration was once defined by academics working alongside a community group, our shared endeavours helped to produce something closer to a hybridized organization of skills and interests unified by experience. Experience and confidence gained from earlier phases of the project – whether arising out of the design of the heritage app or the choreography of the community drama – helped to give these activities momentum and have served to build trust between all involved.

Discussion

In this final section, we reflect on what we have learnt from our involvement in community heritage research at the Bennachie Colony commenting specifically on the nature of our collaboration. Did our collaborations live up to the expected standard of co-production? The answer is more complex than a binary response affords and demands further unpacking. And to what extent did our understandings of identity and community evolve? The project can be defined by aspects of both stability and change, necessitating a more thoughtful discussion of the varied identities and community relationships that came into focus mediated by a range of issues.

Before looking at these questions in more detail, it is worth taking a step back to consider some of the defining characteristics of the project. One of these is that the BLP unfolded over a longer timeframe and involved a much wider group of people than first envisaged. This has been a strength of the project. Indeed, for the Bailies, this has always been part of the plan. Writing on behalf of the organization, Colin Shepherd originally proposed an ‘open-ended’ venture, where ‘the wider community would play a very important part in evidence gathering … laying the foundations for a community project which could evolve’ (Shepherd Citation2010, 2). The BLP developed to accommodate timescales that took into account the nature of voluntary work, and so was less driven by deadlines. As a reassurance for those worried about slow progress, the Senior Bailie, Jackie Cumberbirch, reminded participants more than once that ‘the hill isn’t going anywhere and neither are we’. The commitment of the community partners to the project, combined with the fact they pre-existed our collaboration and were not going to disappear without us, is in marked contrast to some other community heritage projects focused on building community relations around a single funded activity on a time-limited basis. However, at the same time, its considerable lifespan has allowed the introduction of new variables. This has included new project aims, members, places, even new communities into the fabric of our collaboration. It has also permitted participants to better understand the skills possessed by an eclectic membership. The incorporation of such factors, therefore, presents challenges when looking back to evaluate the nature of our collaboration and whether it is appropriate to view its disparate strands as being ‘co-produced’.

The spectrum of co-production

Co-production is often discussed through a binary optic: either the levelling of hierarchies is achieved and co-production results or it is not achieved. But in reality, co-production is context-specific; it is implicated in practice with a set of participants, a place and an objective. What is more, because community heritage entails a chain of events, from planning to activity phases to intellectual work, with a good deal of improvising along the way, co-production should, therefore, be seen along a spectrum. Not only must we ask what, exactly, is being co-produced, but we must also reflect on who is involved in the doing because collaborative research involves a particular configuration of actors, normally community members and academics. As such, the problems of evaluation are anything but straightforward (Matthews et al. Citation2017, 47).

Comparing some of the different aspects of our collaboration allow us to put the nature of our engagement and its attendant communities into sharper relief. Practical activities introduced at the beginning of the project were important for encouraging wide participation, though due to the maintenance of different skill sets (and hierarchies), not all fit comfortably within the idea of ‘co-production’. However, they also played a secondary role. They were important for encouraging less hierarchically organized activities in later phases of work. This was seen for example in archaeological fieldwork where Bailies who had gained experience played a role in supervising weekend volunteers in test-pitting, or where university participants contributed their labour to the creation of the kailyard, and in the archives where community researchers made decisions around the identification of relevant sources.

Undertaken over longer timescales, these activities also helped to resolve the boundaries of our community membership. For example, much of the research for the BLP – archaeological and archival work – has been undertaken by a group of ‘regulars’ known informally as the Landscape Group. Routine high-level planning meetings helped to provide the identity of this group with a sense of legitimacy. At the same time, sub-specializations evolved within the Landscape Group so that certain individuals cut their teeth on either archaeology or archives resulting in participants identifying more strongly with one of these methods, though there was also overlap. While the affiliation of the BLP has changed over time, a core membership has also provided it with an important degree of continuity and leadership (cf. Johnson and Simpson Citation2013, 62).

Acquiring skills and gaining confidence to use them is one aspect of co-produced research. But there are others as well. Vergunst and Graham (Citation2019) help us expand on this in terms of ‘enskillment’. While learning technical skills allows people to participate, research skills are not solely derived from mastering the techniques of disciplines like archaeology or history. Working together is also a skill that needs to be learnt and practiced by all participants, and it may be applied with varying levels of dexterity. At Bennachie, this might be identified as the skills of inhabiting what we call the ‘research landscape’. These include not only an ability to negotiate the technical challenges of working on the hillside or in the archives but also an ability to share in the learning of ‘soft skills' (Vergunst et al. Citation2019, 33), codes and norms that are part of any established community of practice (e.g. Wenger Citation1999). Early activities probably resembled research training more than co-production, because hierarchies between ‘professionals’ and ‘volunteers’ were entrenched, and many participants were new to each other. However, this configuration had its benefits. Learning soft skills, developing group cohesion and willingness to push the project forward meant that activities and their offshoots empowered the expression of new identities and deeper aspects of co-production.

Enskillment helped reinvent the identities of our membership. For example, Bailies who had participated in earlier aspects of archaeological fieldwork were regularly involved in later phases of activity, such as plane table survey of the Colony crofts in 2016. Our work in these contexts felt more like teamwork than public engagement (). Rather than ‘professionals’ and ‘volunteers’, a more common configuration saw us as enthusiasts doing archaeological or archival research together (Hale et al. Citation2017; Vergunst et al. Citation2017); divides that formerly had significance receded into the background. In others, notably some of the offshoots of the project, community members have taken a leading role in extending aspects of the original project, such as mapping the complex trackway systems cut into the hillside or researching the genealogies of the Colony families on and off the hill. Indeed, up until this point, we tended to discuss ‘the community’ with reference to our own positionality as university participants on the outside of this grouping. However, as the project gained momentum over the years it is important to consider how far the academic partners were engaged by our community membership to continue what we had started. With the culmination of funded archaeological fieldwork in around 2014 and the design of the exhibition, the establishment of the Landscape Group as entity with its own regular meetings and agendas was instrumental to progress a wider ‘Bennachie Landscapes Project’ to which academic partners were invited to join. This configuration meant that the Bailies retained an ownership role over the wider programme of activity. At the same time, it is important to observe that all contributors, including academics, were in a real sense ‘volunteers’, especially considering that our funding did not actually cover staff involvement, meaning most work was undertaken on the weekend and evenings (Milek Citation2018, 42). All parties gave freely of their time and were committed to doing so.

More limited aspects of co-production

Among uninitiated enthusiasts of community research, it is easy to be over-optimistic that collaboration will naturally entail co-production. Projects that emphasize the use of accessible activities and practical skills can afford to be more sanguine (e.g. Johnson and Simpson Citation2013), particularly where they ensure wide involvement. Seeing community collaborators ‘take charge’ of various situations, whether on the hill or in the archive might be seen as crossing this threshold. However, as Hart’s (Citation1997) ladder of participation reminds us, ‘involvement’ is not the same thing as decision-making so may be open to the charge of tokenism. What is more, where projects require more specialized training, education, time and commitment, the ability to affect co-production may be in doubt. Although community membership is often produced through the practice of undertaking research together, not all aspects of community heritage are defined by wide participation. As Byrne (Citation2012) notes, other aspects can be defined by non-participation for diverse reasons. In other contexts, participation may be much more limited where tasks or subsidiary projects benefit from more focused, labour-intensive, intellectual work undertaken by individuals or small groups. All of this has implications for understanding the nature of ‘collaborative research’, not all of which can be labelled as ‘positive’ or ‘co-produced’.

The situation comes into sharp relief with activities that demand technical or analytical expertise or where they lend themselves to individual pursuits. This is particularly the case in heritage research that aims not only to ‘engage’ a local community, often around a set of practical activities, but also to create ‘outputs’, particularly in the form of scholarly works or more accessible publications. The Bennachie Landscapes Project not only aimed to get local people doing archaeology and archival research on the Colony, it also sought to create a new sense of understanding its history and presenting our findings to a range of ‘publics’. Areas probed by our research have ranged widely, from the genealogy of Colony residents using census records to the vegetational history of the hillside through pollen record trapped in peat bogs.

Goals such as these can test the limits of the co-production model because they necessitate degrees of individual commitment, the learning of specialized bodies of expert knowledge and the processing of ideas more conducive to private study. While gaining ‘expertise’ in a task like shovel testing might empower many individuals, turning evidence into data and producing an archaeological report requires additional levels of learning and ability. The same might be said about archival research. Locating relevant documents that can be used by others is a skill that can be developed over several afternoons under the guidance of trained archivists, but the selection and synthesis of that information into a compelling historical narrative requires analytical competence and historical awareness that lends itself to individual pursuit. Likewise, writing for a public audience, which plays an important role in communicating the project to wider audiences, requires a special skillset. These activities typically took place off the hillside, away from our community-focused events, in private homes, offices and laboratories – the more exclusive surroundings of scholarly activity.

It is important to emphasize the limitations of co-production where the practices of individual scholarship, and the expectations of academic employment, encourage more traditional configurations of knowledge creation and authority. It is probably fair to say that many community heritage projects diminish substantial collaboration when it comes to aspects of higher-level interpretation and publication. However, given a number of factors, as described previously, the BLP has resulted in a more complex legacy. While some of the academics had clear ideas about what publication should entail at the beginning of the project – and imagined this would be left to them – the diverse interests and capabilities of individuals within the wider group, along with the realization that there were many stories worth telling, meant that the history of publication has reflected the varied agendas and specializations of those who became associated with the project. This included not only professional researchers but also a significant minority within the Bailies organization, a fact that helps to chip away at the idea that academics are the natural arbiters of knowledge creation. Although the project has unfolded over many years, and has involved many different people and places, it has also benefited from the consistent contributions of academic and community participants within the landscape group who began to blur the more expected boundaries of expertise. For example, in the context of archival research, a few community researchers became peers working alongside academics to co-write academic publications that were made stronger through their combined contributions (e.g. Armstrong, Miller, and Oliver Citation2015). Elsewhere these same individuals pursued their own research questions that stemmed from different aspects of collaborative fieldwork and archival research. Their finished work was subsequently made public through the production of conference papers, written articles, and book chapters. It is worth noting that this aspect of the project allowed participants the greatest degree of independence in terms of decision-making (Oliver et al. Citation2016, 353).

Conclusions

The Bennachie Landscapes Project began with a diverse group of people with a passion for the archaeology and history of the Colony, and eventually with a plan to co-produce research. With the advantage of hindsight, we are better placed to understand the nature of our co-production, how it was realized in practice, the different forms it has taken, and indeed the relationships within our collaboration that may fall short of our initial expectations. Reflecting on the BLP and its afterlife provides us also with lessons for the future.

The different meanings of co-production

Co-production can mean many things to different people. Even accepting a minimal definition, where community research is characterized by a degree of shared decision-making in the context of planning and undertaking research, what we expect to co-produce may change as projects move forward. Here we agree with Pahl and Facer who recognize that such research ‘is not linear with clear lines of causality, rather they are entangled, complex and associated with divergent outcomes’ (Citation2017, 215). With our collaboration located in different contexts, and so with different aims, a degree of openness and ambiguity is, therefore, to be expected.

Research activities and their impact on community formation

Research activities have a clear impact on the scale of participation and thus can shape community building. Low tech, easily learnt, group activities such as shovel test-pitting, sifting through documents, or group storytelling realize feelings of collaboration with more limited effort and absorb many hands. They also can provide a springboard for growing community connections. By the same token, they may not be enough on their own to create deeper ties of project ownership or more meaningful community ties over the long term. Activities that require more focused project work, teamwork and investment, such as archaeological excavation or higher-level interpretation (including the BLP pop-up banner exhibition) lend themselves to stronger ties of integration and may, therefore, provide the groundwork for stronger community relationships. We should, therefore, not expect wide levels of participation across all aspects of community heritage research; smaller task-based group identities involved in planning, coordination or interpretation should be seen as a normal part of larger programmes of collaboration.

Community, trust and success

Community relationships are fundamental to project success. The long-term nature of the BLP is partly a reflection of community connections that preceded our engagement and which were further developed as the project matured. The demographic characteristics of the Bailies (many retired and from professional backgrounds) and the fact that they were well-rooted in the landscape of Bennachie are important formative factors (communities built around projects without a prior history can be more challenging to sustain). Added to this is the formation of the Landscapes Group – a steering group derived from the wider Bailies organization – who have shown considerable resolve in sticking together, enabling more demanding forms of collaboration, such as high-level decision-making, interpretation, writing, and leadership of more recent activities, such as designing the project heritage app. To this group, we can now add the academics who started outside the community but now feel firmly within it. Perhaps the most important element is the building of trust. As we have noted above, trusting relationships are the most effective for enabling the sorts of co-production we often imagine that community heritage projects should create. But trust takes time, patience, and a good deal of commitment. It is trust that propels us forward.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Bailies of Bennachie for their continued support, enthusiasm, and friendship over many years – may our collaboration continue! Particular thanks go to Chris Foster, Barry Foster and Colin Miller for their helpful advice on an earlier draft and to Ana Jorge for assistance with the figures. We are grateful to two external reviewers for comments that have helped to sharpen our thoughts and to Thomas Kador for editorial suggestions. The interview material published here is provided through informed oral consent of the research participants. Ethics approval was obtained by the University of Aberdeen’s Committee for Research Ethics & Governance in Arts and Social Sciences and Business.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jeff Oliver

Jeff Oliver is Senior Lecturer in Archaeology at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland. He has been involved in the archaeological dimensions of the Bennachie Landscape Project since 2011.

Jackson Armstrong

Jackson Armstrong is Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland. He helped with the design and implementation of the community archival research strategy on the Bennachie Colony.

Elizabeth Curtis

Elizabeth Curtis is Lecturer of Education at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland. She has taken a leading role in coordinating the experiential learning aspects of the Bennachie Landscape project since 2011.

Neil Curtis

Neil Curtis is Head of Museums and Special Collections at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland. He has been involved with helping make decisions around the exhibition and display of the Bennachie Landscape Project’s research discoveries.

Jo Vergunst

Jo Vergunst is Senior Lecturer in Anthropology at the University of Aberdeen. He has played a leading role in collecting oral histories and understanding human attitudes on the Bennachie Landscape Project since 2011.

References

- Aberdeen University Library (AUL). MS 2764 Arbuthnott of Arbuthnott.

- Aberdeen University Library (AUL). MS 3744 Davidson and Garden, Advocates. Aberdeen.

- AHRC. n.d. “Connected Communities.” Accessed October 6, 2021. https://ahrc.ukri.org/documents/publications/connected-communities-brochure/.

- Armstrong, Jackson, Colin Miller, and Jeff Oliver. 2015. “Bringing Archives and Archaeology Together: Community Research at the Bennachie Colony.” Scottish Archives 21: 18–29.

- Bailies of Bennachie. n.d. “Digital Bennachie.” Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.digitalbennachie.org/virtualmuseum/.

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2001. Community: Seeking Safety in an Insecure World. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bogdan, N. Q., P. Z. Dransart, T. Upson-Smith, and J. Trigg. 2000. Bennachie Colony House Excavation: An Extended Interim Report. Unpublished Report for the Scottish Episcopal Palaces Project.

- Byrne, Sarah. 2012. “Community Archaeology as Knowledge Management: Reflections from Uneapa Island, Papua New Guinea.” Public Archaeology 11 (1): 26–52.

- Contier, Xavier Sven Colverson. 2015. “The Institution of the Museum in the Early Twenty-First Century in Scotland.” PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh.

- Davis, Oliver, Dave Horton, Helen McCarthy, and Dave Wyatt. 2019. “The Caerau and Ely Rediscovering Heritage Project: Legacies of Co-Produced Research.” In Heritage as Community Research: Legacies of Co-Production, edited by Helen Graham, and Jo Vergunst, 129–148. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Delanty, Gerard. 2003. Community: Key Ideas. London: Routledge.

- Facer, Keri, and Kate Pahl. 2017a. “Introduction.” In Valuing Interdisciplinary Collaborative Research: Beyond Impact, edited by Keri Facer, and Kate Pahl, 215–231. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Facer, Keri, and Kate Pahl, eds. 2017b. Valuing Interdisciplinary Collaborative Research: Beyond Impact. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Fagen, Jennifer. 2011. The Bennachie Colony Project: Examining the Lives and Impact of the Bennachie Colonists. Bennachie Landscapes Series 1. Inverurie: The Bailies of Bennachie.

- Foster, Chris. 2014. “Bennachie Landscapes Project.” Leopard 403: 18–20.

- Freire, Paulo. 2001. Pedagogy of Freedom: Ethics, Democracy and Civic Courage. Lanhham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Graham, Helen, and Jo Vergunst, eds. 2019. Heritage as Community Research: Legacies of Co-Production. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Hale, Alex, Alison Fisher, John Hutchinson, Stuart Jeffrey, Sian Jones, Mhairi Maxwell, and John Stewart Watson. 2017. “Disrupting the Heritage of Place: Practising Counter-Archaeologies at Dumby, Scotland.” World Archaeology 49 (3): 372–387.

- Harper, Marjory, ed. 2012. Footloose in Farm Service: Autobiographical Recollections of John Dickie. Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen, Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies.

- Hart, Roger A. 1997. Children’s Participation: The Theory and Practice of Involving Young Citizens in Community Development and Environmental Care. London: Earthscan/UNICEF.

- Holtorf, Cornelius. 2005. From Stonehenge to Las Vegas: Archaeology as Popular Culture. Oxford: Altamira.

- Johnson, Melanie, and Biddy Simpson. 2013. “Public Engagement at Prestongrange: Reflections on a Community Project.” In Archaeology, the Public and the Recent Past, edited by Chris Dalglish, 55–64. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press.

- Johnston, Robert, and Kimberly Marwood. 2017. “Action Heritage: Research, Communities, Social Justice.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (9): 816–831.

- Jones, Sian, Stuart Jeffrey, Mhairi Maxwell, Alex Hale, and Cara Jones. 2018. “3D Heritage Visualisation and the Negotiation of Authenticity: The ACCORD Project.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (4): 333–353.

- Kennedy, Alison. 2014. “Bennachie Landscapes Project.” Aberdeen and North-East Scotland Family History Society Journal 130: 41–46.

- Kindon, Sara, Rachel Pain, and Mike Kesby. 2007. Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting People, Participation and Place. London: Routledge.

- Klein, Julie T. 1990. Interdisciplinarity: History, Theory, Practice. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Lassiter, Luke E. 2005. The Chicago Guide to Collaborative Ethnography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ledingham, Ken. 2014. “An Aberdeenshire Estate Rental Book: The Estates of Leslie of Balquhain, 1875–84.” Scottish Local History 89: 15–26.

- Matthews, Peter, Janice Astbury, Julie Brown, Laura Brown, Steve Connelly, and Dave O’Brien. 2017. “Evaluating Legacy: The Who, What, Why, When and Where of Evaluation for Community Research.” In Valuing Interdisciplinary Collaborative Research: Beyond Impact, edited by Keri Facer, and Kate Pahl, 45–66. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Milek, Karen. 2018. “Transdisciplinary Archaeology and the Future of Archaeological Practice: Citizen Science, Portable Science, Ethical Science.” Norwegian Archaeological Review 51: 36–47.

- Miller, Colin H. 2015. “Bennachie, the “Colony”, Balquhain and Fetternear: Some Archival Sources.” Northern Scotland 6: 70–83.

- Noddings, Nel. 2016. Philosophy of Education. New York: Routledge.

- Oliver, Jeff. 2020. “On Interdisciplinarity in Historical Archaeology.” In The Routledge Handbook of Global Historical Archaeology, edited by Charles E. Orser, Andrés Zarankin, Pedro P. A. Funari, Susan Lawrence, and James Symonds, 264–288. London: Routledge.

- Oliver, Jeff, Jackson Armstrong, Karen Milek, James E. Schofield, Jo Vergunst, Thomas Brochard, Aife Gould, and Gordon Noble. 2016. “The Bennachie Colony: A Nineteenth-Century Informal Community in Northeast Scotland.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 20 (2): 341–377.

- Oliver, Jeff, Gordon Noble, Rick Knecht, Karen Milek, Jo Vergunst, Elizabeth Curtis, and Neil Curtis. 2012. Bennachie Landscapes: Investigating Communities Past and Present at the Colony Site. AHRC Development Grant Application. https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref=AH%2FK007750%2F1.

- Oliver, Jeff, Gordon Noble, Colin Shepherd, Rick Knecht, Karen Milek, and Óskar Sveinbjarnarson. 2013. “Historical Archaeology and the ‘Colony’: Reflections on Fieldwork at a 19th-Century Settlement in Rural Scotland.” In Bennachie and the Garioch: Society and Ecology in the History of North-East Scotland, Bennachie Landscapes Series 2, edited by Colin Shepherd, 101–122. Inverurie: The Bailies of Bennachie.

- Pahl, Kate, and Kerri Facer. 2017. “Understanding Collaborative Research Practices: A Lexicon.” In Valuing Interdisciplinary Collaborative Research: Beyond Impact, edited by Keri Facer, and Kate Pahl, 215–231. Bristol: Policy Press.

- RCAHMS. 2011. A Practical Guide to Recording Archaeological Sites. Edinburgh: Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

- Shepherd, Colin. 2010. Bennachie Biocultural Study. Unpublished Project Design Prepared for the Bailies of Bennachie.

- Shepherd, Colin, ed. 2013. Bennachie and the Garioch: Society and Ecology in the History of North-East Scotland. Bennachie Landscapes Series 2. Inverurie: The Bailies of Bennachie.

- Shepherd, Colin, ed. 2015. Bennachie and the Garioch: Society and Ecology in the History of North-East Scotland. Bennachie Landscapes Series 3. Inverurie: The Bailies of Bennachie.

- Shepherd, Colin, ed. 2018. Bennachie and the Garioch: Society and Ecology in the History of North-East Scotland. Bennachie Landscapes Series 4. Inverurie: The Bailies of Bennachie.

- Silliman, Stephen W, ed. 2008. Collaborating at the Trowel’s Edge: Teaching and Learning in Indigenous Archaeology. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Simpson, Faye, and Howard Williams. 2008. “Evaluating Community Archaeology in the UK.” Public Archaeology 7: 69–90.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Stephens, Lucie, Josh Ryan-Collins, and David Boyle. 2008. Co-production: A Manifesto for Growing the Core Economy. London: New Economics Foundation.

- Straight, Bilinda, Paul J. Lane, Charles E Hilton, and Musa Letua. 2015. “It was Maendeleo That Removed Them: Disturbing Burials and Reciprocal Knowledge Production in a Context of Collaborative Archaeology.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 21: 391–418.

- Vergunst, Jo, Elisabeth Curtis, Neil Curtis, Jeff Oliver, and Colin Shepherd. 2019. “Shaping Heritage in the Landscape Amongst Communities Past and Present.” In Heritage as Community Research: Legacies of Co-Production, edited by Helen Graham, and Jo Vergunst, 27–50. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Vergunst, Jo, Elisabeth Curtis, Oliver Davis, Helen Graham, Robert Johnston, and Colin Shepherd. 2017. “Material Legacies: Shaping Things and Places Through Heritage.” In Valuing Interdisciplinary Collaborative Research: Beyond Impact, edited by Keri Facer, and Kate Pahl, 153–171. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Vergunst, Jo, and Helen Graham. 2019. “Introduction: Heritage as Community Research.” In Heritage as Community Research: Legacies of Co-Production, edited by Helen Graham, and Jo Vergunst, 27–50. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Waterton, Emma, and Steve Watson. 2011. Heritage and Community Engagement. London: Routledge.

- Wenger, Etienne. 1999. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.