ABSTRACT

Life in the Roman World (LitRW) is a programme for schools based on research carried out by the School of Archaeology and Ancient History (SAAH) at the University of Leicester (UoL) on Roman-era identities, and large-scale investigation of Roman Leicester by University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS). LitRW includes a book and teaching resources which have introduced new non-traditional audiences to the complex, diverse communities of the Roman world through the prism of local heritage. This programme has dramatically increased teacher and pupil engagement with archaeology and classical subjects in state schools in the East Midlands, making Roman-era history, culture and language accessible to c. 9,900 participants, many from disadvantaged backgrounds.

1. Introduction and rationale

If your work lives in a locked room with a tiny door, with only a few keys out in circulation to open it, few people will know. Few people will care. It doesn’t matter how powerful the experience is inside the room if most people cannot or choose not to enter. Nina Simon (Citation2016, 21)

Archaeology and Classics in the Community (ACC) was established by students and staff to facilitate school and community engagement with the academic and field research of the School of Archaeology and Ancient History (SAAH), University of Leicester (UoL) and University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS). ACC supports multiple initiatives linked to staff research locally, nationally and worldwide and works collaboratively with external partners, including schools and heritage organizations (e.g. Thomas et al. Citation2019; James et al. Citation2021). This case study focuses on one element of ACC’s work which has introduced new audiences to the study of the ancient world through the prism of local Roman heritage. Research by SAAH staff on Roman-era identities, and large-scale investigation of Roman Leicester by ULAS, has been synthesized and made accessible through a Key Stage 2/3 (KS2/3) programme for schools (age 7–14 years): Life in the Roman World (LitRW). This paper provides an overview of the programme to date and reflects on some of the challenges and opportunities encountered.

1.1 Archaeology and classics in education

The widespread appeal of archaeology is evident today through the popularity of television programmes, community archaeology, and the numbers of visitors to archaeological sites. The interdisciplinary nature and the potential of archaeology in education was recognized in the formative period of the discipline: ‘It must ever be borne in mind, that the science [archaeology] … . is one of the highest consideration, that it might be made of great public utility, and without which every system of education must be incomplete’ (Smith Citation1848, vii; Scott Citation2017). However, there are currently limited opportunities for young people to engage with archaeology through the English national curriculum after KS2 (7–11 years). The lack of opportunities especially for KS3–5 (11–18 years) pupils was exacerbated by the withdrawal of the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) in 2006, and the Advanced Level (A level) in 2016; young people therefore lack the perspective offered by the discipline on global human history, and on the integration of humanities, social science and natural science in its practice (British Academy Citation2016, 17).

The contemporary relevance and appeal of classical subjects is also abundantly clear in popular culture, including books (e.g. Lawrence Citation2001; Harris Citation2009; Riordan Citation2013; Fry Citation2018), as well as the enduring appeal of the work of Mary Renault with its integration of archaeological narrative (e.g. Renault Citation1958). Antiquity is also experiencing a revival in films and television series, comics, and video games (e.g. Winkler Citation2004; Kovacs and Marshall Citation2011; Politopoulos Aris et al. Citation2019). Classicists are working to reveal and celebrate the contributions of people from diverse backgrounds, including working class and female classicists (e.g. Wyles & Hall Citation2016; Stead and Hall Citation2015), and there are several organizations devoted to making classical subjects more accessible (e.g. Classics for All (Hall and Holmes Henderson Citation2017); Advocating Classics http://aceclassics.org.uk/; Holmes-Henderson, Hunt, and Musié Citation2018). However, while classical subjects can be studied to GCSE and A Level, in practice they are largely the preserve of independent schools, especially classical Greek and Latin; the lack of access to classical subjects at A level in state-maintained schools has been defined as ‘classics poverty’ by Hunt and Holmes-Henderson (Citation2021), and perceptions that these subjects are elitist and irrelevant are widespread (see for example Osler Citation2004; see also Morley (Citation2018, 1–40) on the historical background and a discussion of ‘what’s wrong with classics’).

Both archaeology and classical subjects offer numerous possibilities for developing key concepts and skills of far wider applicability, such as an understanding and appreciation of cultural, ethnic and religious diversity, the application and underlying principles of scientific methods and critical reflection on the discovery, preservation and interpretation of the past (Stone and Molyneaux Citation1994; Stone, Henson, and Corbishley Citation2004; Corbishley Citation2011, 152–90; Henson Citation1997; Holmes-Henderson, Hunt, and Musié Citation2018). The impact that such activities can have on both individuals and the wider community is well documented, if not always critically evaluated (Corbishley Citation2011, 291; Henson Citation2009; Holmes-Henderson, Hunt, and Musié Citation2018); for example, while classics is playing an increasingly prominent role in the social justice agenda (Hunt Citation2018), such work can serve to perpetuate a deficit perspective where it is assumed that studying these subjects will improve the lives of students of colour, or improve educational outcomes for pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds, without attempting to examine or address the complex intersecting and systemic causes of inequities (multiculturalclassics.wordpress.com). Cultivating ‘critical consciousness’ is an essential step in addressing such issues (Freire Citation1970), providing opportunities for pupils and teachers (and academics) to affect change within their communities, and to challenge institutional priorities and values more broadly through collaborative and inclusive working.

1.2 Archaeology and Classics in the Community (ACC)

ACC was established in 2014 to facilitate access to archaeology and classical subjects for a wide audience, including school pupils, teachers, and community groups, and to develop inclusive communities of practice (British Academy Citation2016, 6–7). As highlighted in the British Academy’s Reflections on Archaeology (Citation2016, 15), such activities ‘tap into questions of local identity and what sorts of histories are relevant to diverse communities’; the interconnectivity, cultural dynamics and the societal challenges of ethnically and culturally diverse societies in the past are of the utmost relevance to culturally plural populations, such as that of Leicester.Footnote1

We have encountered numerous challenges in the development of ACC, which are more widely recognized, including the perception within Higher Education (HE) that such initiatives are less worthy of investment than ‘scientific breakthroughs’ or ‘big data’ projects (Edwards and Roy Citation2017; Greenburg Citation2019); as cogently argued by Greenburg ‘critical public or collaborative archaeology stands at odds with the dominant academic management paradigm’ (Citation2019, 489; Edwards and Roy Citation2017). While we have received funding from a range of sources, it has been challenging at times to negotiate the diverse aims and reporting requirements of multiple funding bodies. A particular challenge has been securing long-term support for projects which are complex and multi-dimensional; brokering and sustaining partnerships with external stakeholders requires a significant investment of time and resource. We have received University support (in connection with research impact), but the demands of the Research Excellence Framework (REF2021), and especially the focus on metrics and monitoring, has detracted at times from the complex ‘impacts’ that our projects have demonstrated (see Smith et al. Citation2020 for a wider discussion of these issues). Through our collaborations with ULAS (a commercial archaeological unit) and the charity Classics for All (which is supported by individual and corporate philanthropy), our priorities have been shaped to some extent by developer-funded and market-led interests, with the consequent risks of ‘unidirectional deposition’ and the inadvertent perpetuation of ‘Authorised Heritage Discourse’ (Fredheim Citation2018; Greenburg Citation2019; Smith and Waterton Citation2012).

While acknowledging the potential pitfalls and challenges involved, we view the diversification of publications and the provision of access as crucial first steps in ensuring that a wider and more diverse range of voices are involved in shaping academic and institutional priorities, as demonstrated by our Life in the Roman World (LitRW) programme.

1.3 Why Roman Leicester?

LitRW focuses on the culturally plural Roman period in Leicestershire, building on the widespread school and community engagement inspired by hugely successful projects such as the Hallaton treasure project (Score Citation2012), and the discovery of Richard III (Buckley et al. Citation2013). Twenty-five years of large-scale investigations led by ULAS have made Ratae Corieltavorum (Leicester) one of the best explored cities of Rome’s northern provinces and the excavated evidence shows that it was a vibrant multicultural centre from the outset (Buckley, Cooper, and Morris Citation2021; Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 10–2). The Jewry Wall, Roman Leicester’s bath complex, is one of the largest pieces of Roman masonry still standing in Britain. The Jewry Wall Museum opened in 1966, with ‘the Jewry Wall and the Saxon church of St. Nicholas as its most prominent exhibits’ (Friends of the Jewry Wall Newsletter No. 36, Jan. 2016). The collection includes a wide range of evidence for everyday life in the Roman period and has grown significantly in recent years due to the developer funded excavations in the city (Buckley, Cooper, and Morris Citation2021; Buckley et al. Citation2013). The Museum has been shut since 2017 but is now under refurbishment as a £15.5-million visitor centre which it is hoped will ‘breathe life into the stories of citizens from Roman Leicester’, focusing on ‘themes including Leicester’s place in Roman Britain, life in Roman Leicester, the Jewry Wall baths and Leicester’s archaeological pioneers’ (https://news.leicester.gov.uk/news-articles/2021/april/phase-one-of-jewry-wall-revamp-underway/). Some councillors have argued that the Museum should not be a post-Covid priority, especially given the higher than expected costs (https://www.leicestermercury.co.uk/news/leicester-news/multi-million-pound-roman-attraction-4990634), but the City Mayor Sir Peter Soulsby views it as an important initiative for drawing visitors to Leicester, and for reinvigorating the city centre. A key challenge is to ensure that Leicester’s Roman heritage is accessible and relevant to Leicester’s culturally plural population, and to those living in areas of central Leicester which are within the 10% most deprived nationally (English Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015).

In 2015 we were awarded funding by the national charity Classics for All (CfA) – the charity was founded in 2010 to reverse the decline in the teaching of classics in state schools and aims to enrich the lives and raise the aspirations and achievements of all young people through learning about the classical world (https://classicsforall.org.uk/). This funding enabled us to employ a part-time coordinator Jane Ainsworth (SAAH PhD and experienced teacher). CfA at this time placed particular emphasis on Latin; while Latin was a key element of our proposal, we also saw this as an opportunity to demonstrate the potential of an alternative but complementary approach focused on Leicester’s exceptional Roman heritage. Our aim was to work with teachers and pupils to develop an ambitious, coherent and inspiring programme for pupils at Key Stages 2/3 (LitRW), informed by recent research, showing how this could be embedded in core subjects (especially English and History) facilitating rich and deep learning. A key aim of LitRW is to encourage life-long engagement in the local community and its history, and to empower young people from all backgrounds to shape priorities and contribute to knowledge generation in the future.

We started running after-school clubs in three schools in 2015, introducing Latin in the context of everyday life in Roman Leicester. The after-school clubs were successful in many respects, with positive feedback from both pupils and teachers. However, we faced three significant challenges: (1) the logistics and expense of sending several groups of student volunteers to schools across Leicester with limited resource; (2) evaluating the effectiveness of the clubs and the student and school experience, and (3) encouraging schools to commit to the programme longer-term; achieving sustainability is a key challenge facing school and community engagement programmes (see for e.g. Moshenska, Dhanjal, and Cooper Citation2009 and Searle, Jackson, and Scott Citation2018, 29). It was increasingly evident that schools had very different needs and interests and that a more flexible approach was required. In order to address these issues, we shifted focus from running clubs to offering free training, resources and mentoring for teachers and taster sessions and enrichment activities for pupils on campus and in schools. This approach resulted in far greater levels of engagement and enthusiasm, often with the strong support of senior leadership in schools and multi-academy trusts, and was easier to manage. Providing training and mentoring for several teachers within a school or trust also significantly increased the chance of long-term commitment and inspired teachers to contribute to the development of the programme; for example, through ambassadorial roles, promoting and supporting the introduction of classical subjects within their own trusts and further afield. The success of this approach, as shown by the numbers of pupils and teachers engaged, and qualitative feedback from teachers, resulted in further investment from Classics for All and support from the University. This enabled us to write a book (Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018) and to develop linked teaching resources for KS2/3 (Ainsworth, Savani, and Taylor Citation2018; Ainsworth Citation2020). It also resulted in an expanded range of opportunities for schools, supervisory roles for PhD students, and accredited professional development opportunities (volunteering and internships) for University of Leicester students.

Through investigating and celebrating diverse voices and life stories, LitRW is aligned with the national curriculum and Ofsted priorities, such as ‘discern how and why contrasting arguments and interpretations of the past have been constructed’, and the provision of access to ‘the corpus of knowledge that should be the entitlement of every child’ (Ofsted Jan 2019). An appendix to the teaching resources makes clear how tasks meet national curriculum aims and objectives for different subjects. Pupils in areas of disadvantage are disproportionately impacted by the lack of such opportunities; as stressed by Ofsted, such ‘distortions have the greatest negative effect on the pupils we should care most about: the most disadvantaged, the poor and those with special educational needs and/or disabilities (SEND)’ (Ofsted, Jan 2019). LitRW encourages pupils and teachers to question priorities and dominant narratives, and to explore diverse, or discrepant, experiences through a critical approach to both written sources and objects. The aim is to empower pupils and teachers to question evidence and interpretations, and to use LitRW as a springboard for developing their own knowledge and interests.

2. Life in the Roman world: Roman Leicester

The notion of a ‘benign’ Roman imperialism is common in popular literature and museum displays and embedded in schools curricula and textbooks (Morley Citation2010, 8–9; Mills Citation2013, 1–10; Polm Citation2016, 237; Hingley Citation2021). The limitations of narrowly defined perspectives on ‘nation building’ in the English national history curriculum have been highlighted by education professionals (e.g. Moncrieffe Citation2018a; Citation2018b). The main protagonists are elite white men (past and present) with Romanization seen as a unidirectional and beneficial process resulting in the inevitable adoption of Roman lifestyle. The shortcomings of this nineteenth-century conception mirroring contemporary European colonialism are now widely recognized (Hingley Citation2021; Mattingly Citation2004; Citation2007; Citation2011).

LitRW draws explicitly upon our combined expertize in archaeology, ancient history and Latin at three scales: empire, province and city. It considers Roman occupation through the eyes of different people and groups – men, women, adults, children, soldiers, warriors, merchants, farmers – and shows that there was no stereotypical ‘life in Roman Britain’ (Mattingly Citation2007). This approach is shaped by the notion of ‘discrepant experience’, an explanatory concept drawn from research into modern colonialisms (Mattingly Citation2007). Diverse responses to Roman rule are also explored through violence and conflict within and between ancient identity groups (James Citation2011), and through studies of the experiences of women and children in contexts ranging from military bases to Roman households (Allison Citation2013; Harlow Citation2012). The complexity of Iron-Age communities in the region and their connections with the Roman world are also examined (Score Citation2012).

Such research has been made accessible through a programme that comprises a book, teaching resources and continuing professional development courses for teachers, with a focus on pedagogy. We also offer enrichment activities facilitating engagement with ancient evidence and the processes of interpretation, drawing on ULAS excavations across the East Midlands and local museum collections, and including as-yet unpublished data from Leicester. The book (Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018) combines art and narrative with a synthesis of research and archaeological discoveries. The program encourages encourages teachers and pupils to interrogate traditional reconstructions of the Roman past and to develop their understanding of the contexts in which knowledge is produced; for example, it examines the role of women such as Anna Gurney (Brookman Citation2016; Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 8; Scott Citation2017), the first female member of the British Archaeological Association, and the pioneering work of archaeologists such as Kathleen Kenyon and Jean Mellor (Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 11–2). Cultural plurality and interconnectivity in the ancient world are explored through the lives of inhabitants of Ratae Corieltavorum, introducing pupils to a fascinating and highly relevant story of human ingenuity, resilience and creativity in a period of immense social and political upheaval. Leicester’s history and archaeology are placed in a global context to ensure that diverse voices and life stories are investigated and celebrated.

As noted by Polm (Citation2016, 231), the exploitative nature of Roman rule is rarely examined in museum exhibitions and is also frequently glossed over or sanitized in books for young people; the agency of local peoples and regional diversity within provinces are similarly overlooked (Polm Citation2016, 229; 238; see also Hingley Citation2021). Here, the complexities of life at the time of the invasion, and under Roman rule, are explored through recent archaeological discoveries; for example, through the discoveries at Hallaton (Leicestershire) (Score Citation2012; Citation2013), which suggest that long-distance trade and diplomacy was taking place between the inhabitants of the Leicester area and Rome long before the Roman conquest. The realities of ancient warfare are examined (Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 22; Mattingly Citation2007, 87–127), including the impact on women and children, large-scale mobility of populations, and the recruitment of conquered peoples to the army and its consequent ethnic and social diversity (ibid. 23; James Citation2011; on the importance of understanding the ways in which ‘archaeological experts’ inform the identities and roles of people today, see Hingley, Bonacchi, and Sharpe Citation2018, 297).

Everyday life in the Roman world (Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 36) is explored through thematic sections, which include bathing (‘Taking the plunge’; ‘The Jewry Wall Roman baths’); houses (‘Houses in the Roman world’; ‘Living in Roman Leicester: the Vine Street Courtyard House’) and art (‘Art in the Roman world’; ‘Art in Roman Britain’). Traditional interpretations are explained, and their strengths and limitations are discussed; for example, the section on houses explains how terminology used by ancient authors such as Vitruvius, Pliny and Varro has been used uncritically by archaeologists to explain the function of rooms (Allison Citation2001), showing how archaeological evidence was largely used to illustrate the ancient texts which formed the basis of a classical education in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The diversity and creativity of art forms across the empire is described and celebrated (Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 45; Scott and Webster Citation2003); for example, the art and architecture of Roman-era tombs at the site of Ghirza in the Libyan pre-desert, which is a fascinating fusion of Libyan, Punic (Carthaginian) and Roman forms; combining Roman images of power with subjects, styles and ideas that were important locally (Mattingly Citation2003).

The diversity of the Roman world is addressed through evidence from Leicester; for example, the owner of the Vine Street courtyard house may have been a high-ranking military officer who had moved or retired to Leicester, perhaps from elsewhere in the empire (Buckley, Cooper, and Morris Citation2021; Morris, Buckley, and Codd Citation2011, 27; Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 44). A small rectangular ivory panel depicting the Egyptian god Anubis would have been a rare luxury item even in Egypt where it was made and suggests that someone with a military connection may have lived in the house at Vine Street (Buckley, Cooper, and Morris Citation2021, 181–2; Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 51). The diversity of Leicester’s population is also examined through recent burial evidence from the Western Road cemetery; six people buried there may have had African ancestry: two were born in Britain – one in the Leicester area and another in the Pennines – whilst another certainly came from a southern climate such as around the Mediterranean (Morris Citation2016); these burials clearly highlight the complexities of what it means to be ‘local’ (see Eckhardt Citation2010; Eckhardt, Müldner, and Lewis Citation2014 for archaeological approaches to mobility and diversity; for an overview of recent projects and debates discussing Roman migration in the context of contemporary diverse communities in Britain, see Hingley, Bonacchi, and Sharpe Citation2018, 294).

2.1 Combining art and narrative

Archaeological imagination has received significant attention over the last two decades. Scholars have used this concept to explore interceptions between art and archaeology (Jameson, Christine, and Ehrenhard Citation2003; Van Dyke and Bernbeck Citation2015) as well as a theoretical tool to engage with a broad range of social and cultural issues (e.g. Wallace Citation2004; Sanders Citation2009; Shanks Citation2012). While a concern for the risks of an ‘imaginative’ archaeology have led many to discourage any creative interference with the ‘scientific’ core of the discipline (e.g. James Citation1997, 23; Bernbeck Citation2015, 258), recent collaborations between artists and archaeologists are starting to reveal the role that creativity can have in academic discourses (e.g. Dann and Jollet Citation2018; Savani and Thompson Citation2020). In their volume Theatre/Archaeology, Michael Shanks and Mike Pearson (2001: 62–4) suggest a non-hierarchical approach to a site report, with documents of different natures (e.g. texts, images, musical notations) contributing collectively to create a more nuanced picture of an archaeological site. In their model, creativity is not a threat to science because these work on parallel planes – they are not competing to reveal an elusive ‘historical truth’. Rather, they provide very different tools to engage with the same, fragmented picture of the past. The flexibility of this approach was exactly what we needed for the book.

Pearson and Shanks’ paratactic methodology influenced the way we structured each chapter, which is subdivided into three distinct but closely interrelated components: an illustration; the narrative; and an educational section. This structure provides three different but compatible ways to engage with the past.

The narrative is written from the perspective of a local god, Maglus, who observes everyday life in and around Ratae. Maglus is the divine addressee of a curse tablet found in 2005 during the excavation of a Roman house in Leicester (Tomlin Citation2008, 208; Tomlin Citation2009, 327–8, Nr. 21; Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 49). His immortality makes him the perfect witness to the impact that the ‘Roman way of life’ had on the small community of Leicester across the approximately 400 years of Roman occupation. Balancing humour and affection, he accounts for the many changes and contradictions experienced by the inhabitants.

Pupils and teachers from Lionheart Academies Trust provided feedback on images and draft sections of the book at a writing workshop. During the event, the students engaged with the materiality of the past and reflected on how objects shape our identities. When faced with complex and potentially distressing aspects of antiquity such as slavery, they encouraged us to ‘use more harder vocabulary’ and helped us to pitch the writing appropriately. They also emphasized the emotional role that certain objects (e.g. heirlooms) play in their lives and were keen for this aspect to be reflected in the book (on the importance of collaboration between archaeologists and teachers see Hingley, Bonacchi, and Sharpe Citation2018, 287).

The information section expands and explains the narrative, combining text, photographs, and boxes dedicated to specific artefacts or events. These are based on SAAH research and benefitted from the experience of the third co-author, Mathew Morris, who works for University of Leicester Archaeological Services. It was written to highlight ‘multiple interpretations and possibilities’ in contrast to the univocality of the traditional academic voice (Savani and Thompson Citation2020, 212). As argued by Hingley, Bonacchi, and Sharpe (Citation2018, 297), it is important to address the idea of ambiguity in order to develop critical thinking, and to challenge the oversimplified perspective on Roman rule underpinning the English national curriculum. The book therefore contextualizes interpretations, highlighting key debates in Roman archaeology and examining how and why conclusions have been reached by archaeologists and historians.

While the imagined voices of past peoples can be very effective in encouraging archaeologists and the wider public to engage with emotions and the senses, it is important that ambiguities are not masked (Tringham Citation2019, 338); as emphasized by Savani and Thompson (Citation2020, 210), ‘a balanced mixture of authenticity and inventiveness is crucial in (re)constructing all sorts of narratives of the past, in both written and visual works’.

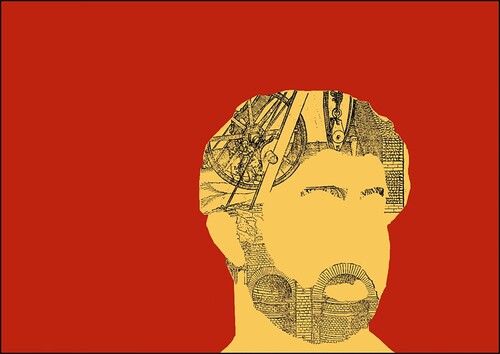

The style of the illustrations changes in order to experiment with different techniques and to complement the narrative of each chapter; for instance, the portrait of the emperor Hadrian that introduces Chapter 4. The chapter is called ‘The City’ and is an attempt to capture the complex process that transformed a small village into a thriving Roman city in less than a lifetime. The information section highlights how Hadrian and his building programme across the empire were central to this process; the image therefore attempts to make the nexus between the emperor and the changes in the architecture of Leicester visible, constructing Hadrian’s portrait using fragments of early-modern illustrations of Vitruvius’ De architectura ().

Figure 1. Hadrian, the builder of cities (Art by Giacomo Savani). Source: Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 31.

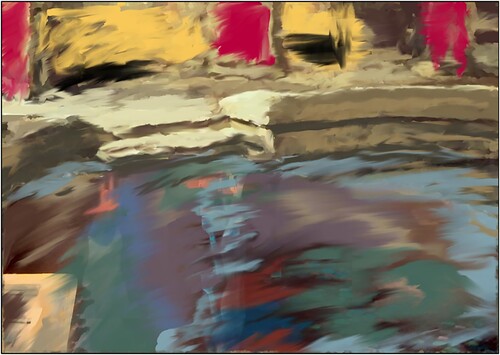

Chapter 5 focuses on the role played by baths and bathing in the process of cultural change promoted by Rome in her provinces. Maglus is a river god and he is curious to discover how humans have managed to subdue water to their will. He therefore pays a visit to the large public bath-house built in Leicester under the emperor Hadrian (). In the hot plunge-bath of these facilities, he discovers a new kind of water (Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 38): ‘fire has changed her’, he says, ‘transfiguring her weightlessness into a heavy, suggestive substance.’ And continues:

And here, overwhelmed by hot vapours, I finally see why your princeps with many names has put so much money into this place. On the opening day, only a few of you knew what to do with it, and now you can’t live without it. No one bathes in the river anymore, that’s for the sick and the savage. I guess the war is really over now.

Figure 2. Foreign water (Art by Giacomo Savani). Source: Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 37.

Chapter 7 is another good example of this paratactic methodology. In this case, the narrative developed from a specific object: the curse tablet addressing the god Maglus. In the ancient world, writing a curse was a way of seeking divine punishment of a wrongdoer and curse tablets were particularly popular in Roman Britain. The message was usually inscribed on a metal tablet which was then thrown into a sacred pool or hidden in a building. For instance, many examples have been recovered from the sacred springs at Bath in Somerset (see Tomlin Citation1988). The one shown here is the so-called Servandus tablet from Leicester (Tomlin Citation2008, 208; Tomlin Citation2009, 327–8, Nr. 21) () and the first few lines read: ‘I give to the god Maglus him who did wrong from the slave-quarters; I give him who did steal the cloak from the slave-quarters; who stole the cloak of Servandus’ (translated by R. S. O. Tomlin). Twenty names are then listed, presumably of other household slaves.

Figure 3. The so-called Servandus tablet from the Roman house discovered in Vine Street, Leicester (University of Leicester Archaeological Services).

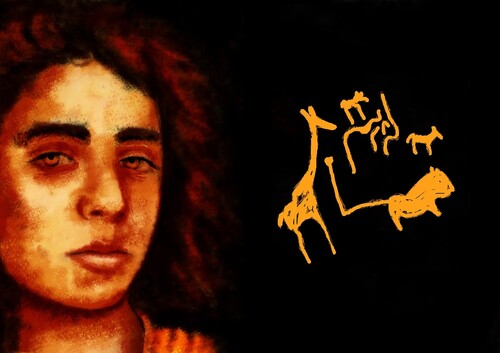

In the narrative Maglus is rather surprized to be the addressee of such a text, because he does not really like Servandus. Moreover, he knows little about the people listed in the tablet: most of them worship foreign deities and pay little attention to local gods. However, he does recognize the name of a girl, Nigella. As Maglus recalls, ‘she was born in a land where the earth is dry and hot, beyond the ocean and the narrow sea’ (Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 48). She sometimes comes to visit him at night, telling him about her homeland and how she was taken away.

Nigella’s story is imagined as follows (Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 48):

Once, Nigella told me about the night she was taken away. About the long journey packed in a cart with men and women and children, about the sweetish stench of the slave markets. About the man who bought her, the way he looked at her, like he was looking at a piece of carved wood. The words the slave trader said: ‘She is warranted healthy and not liable to run away.

These words pronounced by the slave trader are taken from another document from Roman Britain: a tablet found in London in 1996 and dating to the late 1st century CE, which is discussed in the educational section of the chapter. It is a legal document attesting the sale of a girl from Gaul called Fortunata to Vegetus, himself enslaved (Tomlin Citation2003). The coldness of this legal formula contrasts sharply with Nigella’s account, revealing the contradictions of a society where the sale of human beings was not only tolerated but also meticulously regulated. The portrait of Nigella illustrating the chapter () is inspired by the picture of a Syrian refugee, a way to remind us that our world is still very much coping with similar contradictions.

Figure 4. Nigella (Art by Giacomo Savani). Source: Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 47.

These are just a few examples of the complex interactions between archaeology, art, and narrative that shape the book. The challenges faced by archaeologists and artists engaging with the past are very much alike: to decipher the faint tracks of foreign people and landscapes before re-elaborating them into a story (Perry and Johnson Citation2014, 348–49). The story we wanted to tell was one of figures like Nigella, often overlooked in traditional narratives, and everyday life in a provincial town of the empire. While engaging with liminality and multivocality, we also attempted to weave into the narrative some aspects of current theoretical debate in Roman archaeology.

We have distributed 2,000 free copies of the book to schools across the East Midlands as part of a package of training and resources, with support from Classics for All and the University of Leicester. A website RomanLeicester.com was launched at the CBA Festival of Archaeology 2020 to facilitate wider engagement with SAAH and ULAS projects on the Roman world and local Roman collections through collaborative events and resources, and to serve as an information and LitRW resource hub for teachers, young people and the wider community.

2.2 Lesson plans and training

Our LitRW resources for teachers (Ainsworth, Savani, and Taylor Citation2018; Ainsworth Citation2020) are designed to appeal to learners from diverse backgrounds, many with English as a second or third language. By basing the activities in local contexts, the aim is to demonstrate the relevance of the classical world in contemporary life to all pupils, emphasizing the infinite variety, complexity and richness of responses to Roman rule. All activities include information on how pupils can become involved in and gain access to local projects; for example, through participation in Young Archaeologists Clubs and visits to sites such as the Jewry Wall (Leicester) and Harborough Museum (Leicestershire), to encourage life-long engagement in the local community and its history.

The format of sessions, offering a mix of language and culture, responded to the requests of the schools involved, which were not interested in heavy-language courses. They were also an attempt at rethinking some common assumptions about teaching Latin and were designed to cover the three areas identified by John Gruber-Miller (Citation2006) as essential for the learning process of classical languages: communication, context, and community. Gruber-Miller (Citation2006, 14) criticizes the common practice of teaching culture as something separate from the rest of a language class and stresses how ‘[f]or language learners to succeed in communicating, they need to understand the values, attitudes, customs, and rituals of a culture that are expressed in what they hear and read, speak and write’.

The content of the original lesson plans (Ainsworth, Savani, and Taylor Citation2018) was based on seven characters, imagined from the inscriptions and signatures on objects found in Leicester from the Roman period (Morris, Buckley, and Codd Citation2011) and artistically rendered by Savani: Primus, a tile maker who signed a box flue tile; Gracilis, whose stone seal shows he sold ointments; Lucius the gladiator and Verecunda the dancing girl, whose names are found together on a clay love token; Marcus the centurion, whose initials are found on lead seals (see Higgins, Morris, and Stone Citation2009); Servandus and Nigella, names which appear on one of the curse tablets found at Vine Street ().

Figure 5. Primus, Lucius and Verecunda (Art by Giacomo Savani). Box flue with inscription PRIMUS FECIT X Primus made 10 (tiles). The Lucius and Verecunda ‘love token’; a sherd of pottery with the inscription VERECUNDA LUDIA LUCIUS GLADIATOR; ‘Verecunda the actress’ and ‘Lucius the gladiator’. The hole suggests it may have been worn as a love token (University of Leicester Archaeological Services).

More recent resources for KS2/3 (2020), which were written to accompany the book, are designed to engage pupils with the diverse experiences of living in the ancient world through the characters described above, and through a variety of tasks which equip pupils with the skills to critically evaluate different kinds of primary evidence (objects and historical sources) using a framework of questions. The tasks address topics set for study in the national curriculum for History; for example, at KS2 ‘the Roman Empire and its impact on Britain’ and ‘the legacy of Roman culture on art, architecture and literature in Britain and the western world’, but also part of ‘Britain’s settlement by the Anglo-Saxons’. By focusing on the sites of Hallaton and Ratae Corieltavorum, it can also provide a depth study in local history as well as opportunities for low-cost locally-focused school visits. All of the aims and historical skills identified in the history curriculum are addressed by these resources, which also allow opportunities for cross-curricular work in aspects of the art, design technology, English and geography requirements. Opportunities for pupils to investigate how key words in each chapter form the roots of English and other modern foreign languages, are also provided, allowing pupils to consider the different contexts in which derivatives of Latin now appear (Ainsworth Citation2020).

3. Archaeology and classics in leicester schools

Having begun with three schools in 2015, in 2021 we are providing LitRW resources and research-led support for a network of more than 110 schools across the East Midlands. In 2018 we became a regional hub for the charity Classics for All (University of Leicester and East Midlands Classics Network). Cumulatively, at least 6,658 pupils studied the classical world for the first time in taster sessions or dedicated LitRW units within the KS2/3 curriculum for History and/or English 2016–20.

3.1 Reach and significance

In 2014 <2% of Leicester state schools taught classical subjects. 2015–19 ACC provided LitRW training and/or support for 38% of Leicester academies, 41% of primary schools within LE1-3 postcodes and 31% of state-funded secondary schools. Thirteen schools in Leicester embedded LitRW for Years 3–9 (KS2/3). The success of LitRW inspired 11 schools to introduce Latin and 3 to introduce GCSE Classical Civilisation. The schools engaged are diverse in character but many of the inner city schools have a high proportion of pupils with English as an Additional Language (EAL) and/or disadvantaged pupils; for example, at Hazel Community Primary School 39% of pupils are from disadvantaged backgrounds with 73% learning EAL.

The programme is resulting in changes to educational and pedagogical practices in schools. Medway Community Primary School (32% disadvantaged; 93% EAL) introduced the study of the classical world for all Yr 3–6 pupils from 2019: ‘I was attracted to this programme because of the innovative and engaging approach which introduces Latin in the context of life in the Roman world with an emphasis on the experiences of ordinary people from diverse backgrounds … this approach was especially appealing … because we are a school with nearly 100% EAL pupils’ (teacher, Medway Community Primary School). In secondary schools, LitRW is often embedded within KS3 History, and has prompted teachers and pupils to question traditional narratives; a KS3 history teacher reported that the programme had encouraged their students ‘to really think deeply about the nature and impact of the Roman conquest of Britain’ which had previously been approached in a way ‘that is too simplistic’. Crucially, these opportunities are available to all pupils, not just selected groups.

Collaboration with Lionheart Academies Trust (LAT) comprising six secondaries, four primaries and a 6th form college in Leicester, has been especially fruitful (Reynard Citation2020). LitRW support transformed the delivery of the national curriculum for History and English at KS2/3 in Lionheart schools and enabled many teachers to tackle new challenges, profoundly impacting job satisfaction and career opportunities: ‘Classics has changed my experience of teaching. After 8 years of English teaching, it's been great to learn something new – I prefer it to teaching English now.’ (English & Classics teacher, Beauchamp College). In 2017–18 we supported clubs in three Lionheart secondary schools. An instant success, they featured very positively in Cedars Academy’s Ofsted report, and had excellent retention rates. Teachers reported an increased appetite for literature, ancient history and archaeology and University collaboration was very popular. Inspired by success of the clubs, the Trust introduced a 12-week Classical Narratives unit to the Year 7 (11–12 years) English curriculum across its secondary schools.

Access to the classical world is proving particularly beneficial for those children often described as reluctant readers – including those with Special Educational Needs (SEN); for example, it ‘prompted autistic learners to engage … in a way that more traditional KS3 English lessons have not’ (Director of English, LAT). Teachers described improved levels of pupil enthusiasm and engagement and improved vocabulary and grammar. In 2019 LAT introduced a 12-week history module ‘Roman Leicester’ for Year 7 pupils (1,373) across six secondary schools, using LitRW: ‘LitRW offers schools the opportunity to be demographically and geographically relevant … our children are fascinated to learn that Roman Leicester was as multicultural as millennial Leicester is’ (Reynard Citation2020, 85).

Lionheart Academies Trust introduced Latin to all primaries, is now offering GCSE Classical Civilisation, and appointed a Head of Classics in 2019. A Classics Ambassador (a LAT English and Classics teacher funded by Classics for All) works in partnership with us to support schools across the East Midlands introducing classical subjects for the first time.

In 2019, we supported LAT’s successful bid to open a new inner-city free school in Leicester. ‘our bid was bold and unusual (we were told) in that [it] was so firmly academic. There were six other bids, but it was the message that classical subjects act as a means for social justice (Holmes-Henderson, Hunt, and Musié Citation2018), which was also grounded in our proven success at our schools as a result of our work with the University of Leicester and CfA, that meant ours was the successful offer’ (Head of English, LAT).

LitRW is inspiring teachers to design lessons focused on local archaeological heritage; as part of the Year 7 Classical Narratives unit, two Lionheart teachers produced imaginative lesson plans which encouraged pupils to engage with descriptions of archaeological excavation and discovery, and to respond creatively to these. One lesson was based on a newspaper article describing Kathleen Kenyon’s 1936 excavation of the Jewry Wall Roman baths (Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 11); pupils imagined her response to the discovery through a creative writing exercise. Another lesson used a newspaper article (Daily Mail, 2 December 2016; Savani, Scott, and Morris Citation2018, 52) describing the discovery of Roman skeletons of English-born individuals of African descent to encourage pupils to engage with challenging vocabulary; for example, pupils were asked to discuss the meaning of the headline ‘multicultural heritage’ as a starting point. The lesson also explored the ways in which archaeologists use objects to understand the lives of people in the past through a creative time capsule activity.

Future evaluation will use surveys, focus groups and classroom evidence to assess the impact of the programme against intended objectives, and to understand the mechanisms through which transformations might be working. It will include (i) tracking participants through the programme (for example, using Higher Education Access Tracker (HEAT) and regional access trackers and existing partnership tracking) (ii) evaluating teacher engagement, skills and confidence (iii) evaluating pupil engagement, skills and attainment. This research will enable us to further refine and enhance our programmes and to ensure their continued growth.

3.2 Students as collaborators

Recent PhD graduates have played a key role in the co-ordination and delivery of this programme. More than 100 University of Leicester students have received accreditation on their Higher Education Achievement Report (HEAR) through their involvement in this initiative, with more than 15 taking on supervisory roles. In 2018–19, Archaeology and Classics in the Community Internships were established, which provide a programme of training and mentoring for students working with schools.

A partnership with the School of Education, University of Leicester has enabled us to embed training in archaeology and classical subjects within the Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) curriculum since 2019. This initiative was in part a response to the challenge that these are not mainstream curriculum subjects. The seriousness of this problem has been noted by others; for example, Henson, Stone, and Corbishley (Citation2004, 38) emphasize the importance of providing teachers with the confidence, expertize, and support to use archaeology within the curriculum. This kind of training, which does not assume prior knowledge, is an essential step in expanding and diversifying the pool of teachers with the knowledge, skills, and confidence to teach archaeology and classical subjects, especially at KS3 (11–14 years).

4. Engaging pupils and teachers with local heritage through partnerships

Collaboration with local heritage organizations has been key to engaging schools. For example, through Historic England’s Heritage Schools programme, we have been able to reach with a wider range of schools than would otherwise have been possible. The Heritage Schools programme was developed by Historic England in response to the government report on cultural education in England; it aims to help school children develop an understanding of their local heritage and its significance. There is clear synergy between our organizations as we encourage children to engage with their local heritage and to understand how it relates to national and global history. We have delivered training sessions for teachers in partnership with Heritage Schools, and our book and resources are highlighted as best practice by them.

Collaboration with Leicester Creative Business Depot (LCB) (Leicester City Council) and the Friends of the Jewry Wall Museum has enabled us to deliver events, activities and resources linked to Leicester’s Roman heritage. For example, SAAH and ULAS research has underpinned the development of Roman Leicester in Minecraft (funded by Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society). Minecraft is a very popular creative video game that can be played across a number of platforms. Roman Leicester in Minecraft enables young people to engage creatively with local Roman heritage and was successfully launched at a Roman Leicester Day at LCB Depot for the Council for British Archaeology Festival of Archaeology in July 2019 (https://romanleicester.com/2020/07/17/build-like-a-roman/).

In 2020 a partnership was established with the Chester House Estate, a GBP14.5M project funded by National Lottery Heritage Funds and Northants County Council. The Estate (which opened October 2021) will serve as a hub for collaborative and participatory research and learning in Northamptonshire and bordering counties, focused on the small Roman town of Irchester and the Northamptonshire Archaeological Resource Centre (both located within the Estate). LitRW informed the development of a pilot school and community engagement programme in 2019 and has underpinned the interpretation at the site. This project is providing important insights into life in a small rural community; as noted by Hingley, Bonacchi, and Sharpe (Citation2018, 293) approximately 90% of the population of Britain in the Roman period lived in the countryside and this nationally significant site offers opportunities to engage pupils and teachers with the diverse populations who were living and working in these communities to gain a more balanced perspective. It will help us to reach schools in an area of significant deprivation; according to the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2019 profile, Wellingborough (the nearest town to the Estate) is one of the county’s three most deprived areas and within the top 10% most deprived areas nationally.

We are raising the profile of archaeology and classics regionally through hosting events such as the East Midlands Association of Classical Teachers (EMACT) conferences (for pupils 16–18 years) and an annual Latin and Greek reading competition. In 2019, four pupils from Medway Community Primary won the novice Latin class (out of 19 schools, the majority of which were independent schools with a long history of classics teaching). These links have also resulted in collaboration between independent and state schoolteachers: for example, through mentoring and the sharing of resources. These competitions are language focused and traditional in format, but many of the schools, teachers and pupils we are working with value the cultural capital afforded by such opportunities; in turn, their engagement is influencing the range of events, activities and resources offered by these organizations.

LitRW has promoted and facilitated school and community engagement with the Jewry Wall Museum collection and Roman baths site during an extended closure for renovation and during the pandemic. Sarah Scott (SAAH) and Mathew Morris (ULAS) are writing Jewry Wall site guides for the Friends of the Jewry Wall and Leicester City Council, funded by National Lottery Heritage Fund, which draw on LitRW and recent ULAS projects. Through collaboration with Leicester City Council and a wide range of stakeholders we are working to ensure that Leicester’s Roman heritage is engaging and accessible for diverse communities in the city and beyond, and that these communities are empowered to shape future priorities and heritage presentation through a wealth of participatory research and learning opportunities.

5. Conclusions

LitRW is redefining the ways in which archaeology and classics are perceived in schools in the East Midlands through an innovative and flexible set of resources and training which challenge traditional narratives of life under Roman rule and explore diverse, or discrepant, experiences through a critical approach to both written sources and objects. This programme has demonstrated the contemporary relevance and value of these subjects to school leadership teams and teachers, resulting in changes to curricula, teaching practices, and to the priorities of local schools and trusts. We have shown that bespoke training can enable teachers with no previous experience of these subjects to embed them across the KS2/3 curriculum, and in many cases these opportunities have had a significant impact on the careers of those involved. We are now supporting a network of more than 110 schools across the East Midlands, working in partnership with teachers to co-create resources, and to ensure the continued growth and sustainability of the programme through collaboration with a wide range of heritage partners. Our programme has also informed the strategy of Classics for All in connection with teaching resources and support for teachers, especially at Key Stages 2 and 3.

We are encouraging and facilitating wider academic engagement to ensure that the programme reflects the richness, breadth and diversity of current research and that future research is informed by the needs and interests of the wider community. These kinds of initiatives often rely on the passion and commitment of a small number of individuals with the consequent risk of single points of failure; increasing levels of participation and institutional support will further raise the profile and enhance the value of such knowledge exchange activities, offering a wealth of opportunities for universities to contribute to post-Covid social and economic recovery through learning and heritage, and to contribute to the social justice agenda; equality of opportunity is of the utmost importance, especially in light of the growing attainment gap in the wake of Covid.

Notwithstanding the challenges involved, we hope that the success of this initiative will encourage other organizations to work collaboratively to engage pupils and teachers with the richness and multi-disciplinary nature of the ancient world. LitRW highlights the potential of such work for transforming lives and for diversifying our disciplines.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professors Colin Haselgrove, Simon James and David Mattingly for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. This success of this programme is the result of sustained support from many individuals, schools and organisations, especially: Classics for All; Lionheart Academies Trust; Medway Community Primary School; University of Leicester Archaeological Services, especially Mathew Morris; Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society; Leicester City Council; The Friends of the Jewry Wall Museum; Leicester Creative Business Depot; The Chester House Estate (North Northants and West Northants Councils); the staff of the School of Archaeology and Ancient History; the School of Education, University of Leicester especially Marianne Quinsee and Kerry Onyejekwe. Finally, the success of the programme is due especially to the commitment, creativity and enthusiasm of many SAAH student volunteers, interns and team members.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sarah Scott

Sarah Scott’s Professor of Archaeology, School of Archaeology and Ancient History, University of Leicester. https://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/archaeology/people/academics/scott

Giacomo Savani

Giacomo Savani is an RSE Saltire Early Career Fellow at the School of Classics, University of St Andrews.

Jane Ainsworth

Jane Ainsworth, Leicester Classics Hub Manager, University of Leicester

Anna Hunt

Anna Hunt, Director of English, Lionheart Academies Trust, Leicester

Lidia Kuhivchak

Lidia Kuhivchak, Leicester Classics Hub Ambassador, Lionheart Academies Trust, Leicester.

Notes

1 Leicester’s population is 60% Black and Minority Ethnic. https://www.leicester.gov.uk/media/183446/cyp-jsna-chapter-one-setting-the-context.pdf

References

- Ainsworth, Jane. 2020. Life in the Roman World. Key Stage 2 Resources for Teachers. Leicester: University of Leicester and East Midlands Classics Network.

- Ainsworth, Jane, Giacomo Savani, and Katherine Taylor. 2018. Life in the Roman World: Ratae Corieltavorum, Leicester Classics Hub: Resources for Teachers. http://hdl.handle.net/2381/42447.

- Allison, Penelope. 2001. “Using the Material and Written Sources: Turn of the Millennium Approaches to Roman Domestic Space.” American Journal of Archaeology 105 (2): 181–208.

- Allison, Penelope. 2013. People and Spaces in Roman Military Bases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bernbeck, Reinhard. 2015. “From Imaginations of a Peopled Past to a Recognition of Past People.” In Subjects and Narratives in Archaeology, edited by R. M. Van Dyke, and R. Bernbeck, 257–276. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

- Bowden, W. 2020. “What is the Role of the Academic in Community Archaeology? The Changing Nature of Volunteer Participation at Caistor Roman Town.” Journal of Community Archaeology and Heritage.

- British Academy. 2016. Reflections on Archaeology, https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/reflections-on-archaeology.

- Brookman, Helen. 2016. “Gurney, Anna (1795–1857).” In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Accessed 17 Feb, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/11759.

- Buckley, R., N. Cooper, and M. Morris. 2021. Life in Roman and Medieval Leicester: Excavations in the Town’s North-East Quarter, 1958–2006. Leicester: Leicester Archaeology Monographs.

- Buckley, Richard, Mathew Morris, Jo Appleby, Turi King, Deirdre O'Sullivan, and Lin Foxhall. 2013. “: The King in the car Park: Searching for the Last Known Resting Place of King Richard III.” Antiquity 87 (336): 519–538.

- Corbishley, Mike. 2011. Pinning Down the Past: Archaeology, Heritage and Education Today. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- Dann, Rachael J., and Etienne Jollet. 2018. “Looking for Trouble: Archaeology, art and Interdisciplinary Encounters.” The Senses and Society 13 (3): 299–316.

- Eckhardt, Hella. 2010. “Roman Diasporas: Archaeological Approaches to Mobility and Diversity in the Roman Empire.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 78.

- Eckhardt, Hella, Gundula Müldner, and Mary Lewis. 2014. “People on the Move in Roman Britain.” World Archaeology 46 (4): 534–550.

- Edwards, Mark, and Siddartha Roy. 2017. “Academic Research in the 21st Century: Maintaining Scientific Integrity in a Climate of Perverse Incentives and Hypercompetition.” Environmental Engineering Science 34 (1): 51–61.

- Fredheim, Harald. 2018. “‘Endangerment-Driven Heritage Volunteering: Democratization or ‘Changeless Change,’.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (6): 619–633.

- Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin.

- Fry, Stephen. 2018. Mythos. London: Penguin.

- Greenburg, Raphael. 2019. “Wedded to Privilege? Archaeology, Academic Capital and Critical Public Engagement.” Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress 15 (3): 481–495.

- Gruber-Miller, John. 2006. “Communication, Context and Community: Integrating the Standards in the Greek and Latin Classroom.” In When Dead Tongues Speak: Teaching Beginning Greek and Latin, edited by J. Gruber-Miller, 9–25. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hall, Edith, and Arlene Holmes-Henderson. 2017. “Advocating Classics Education – A new National Project.” The Journal of Classics Teaching 18 (36): 25–28.

- Harlow, Mary. 2012. Dress and Identity. Oxford: BAR.

- Harris, Robert. 2009. Lustrum. London: Arrow.

- Henson, Donald. 1997. Archaeology in the English National Curriculum: Using Sites, Buildings and Artefacts. London and York: English Heritage and Council for British Archaeology.

- Henson, Donald. 2009. “The True End of Archaeology?” Primary History 51: 7.

- Henson, Donald, Peter Stone, and Michael Corbishley. 2004. Education and the Historic Environment. London: Routledge.

- Higgins, T., Mathew Morris, and D. Stone. 2009. Life and Death in Leicester’s North-East Quarter: Excavation of a Roman Town House and Mediaeval Parish Churchyard at Vine Street, Leicester (Highcross Leicester) 2004–2006. Leicester: University of Leicester Archaeological Services.

- Hingley, Richard. 2021. “Assessing How Representation of the Roman Past Impacts Public Perceptions of the Province of Britain.” Public Archaeology.

- Hingley, Richard, Chiara Bonacchi, and Kate Sharpe. 2018. “‘Are You Local?’ Indigenous Iron Age and Mobile Roman and Post-Roman Populations: Then, now and in-Between.” Britannia (society for the Promotion of Roman Studies) 49: 283–302.

- Holmes-Henderson, Arlene, Steven Hunt, and Mai Musié. 2018. Forward with Classics. Classical Languages in Schools and Communities. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Hunt, Steven. 2018. “Classics and the Social Justice Agenda of the Coalition Government 2010–2015.” In Forward with Classics, edited by Arlene Holmes-Henderson, Steven Hunt, and Mai Musie, 9–26. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Hunt, Steven, and Arlene Holmes-Henderson. 2021. “A Level Classics Poverty: Classical Subjects in Schools in England: Access, Attainment and Progression.” Council for University Classics Departments Bulletin 50 (2021).

- James, Simon. 1997. “Drawing Inferences: Visual Reconstructions in Theory and Practice.” In The Cultural Life of Images: Visual Representations in Archaeology, edited by Brian L. Molyneaux, 22–48. London: Routledge.

- James, Simon. 2011. Rome and the Sword: How Warriors and Weapons Shaped Roman History. London–New York: Thames & Hudson.

- James, Simon, Lucy Blue, Adam Rogers, and Vicki Score. 2021. “From Phantom Town to Maritime Cultural Landscape and Beyond: Dreamer's Bay Roman-Byzantine ‘Port’, the Akrotiri Peninsula, Cyprus, and Eastern Mediterranean Maritime Communications.” Levant 52: 337–360.

- Jameson, John H. Jr., Finn Christine, and John E Ehrenhard. 2003. Ancient Muses: Archaeology and the Arts. Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama Press.

- Kovacs, George, and C. W. Marshall. 2011. Classics and Comics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lawrence, Caroline. 2001. The Thieves of Ostia. London: Orion.

- Mattingly, David. 2003. “Family Values: Art and Power at Ghirza in the Libyan pre-Desert.” In Roman Imperialism and Provincial Art, edited by Sarah Scott, and Jane Webster, 153–170. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mattingly, David. 2004. “Being Roman: Expressing Identity in a Provincial Setting.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 17: 5–26.

- Mattingly, David. 2007. An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire 54 bc–ad 409. London: Penguin.

- Mattingly, David. 2011. Imperialism, Power and Identity: Experiencing the Roman Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Mills, Nigel. 2013. “Introduction: Presenting the Romans.” In Presenting the Romans: Interpreting the Frontiers of the Roman Empire World Heritage Site, edited by Nigel Mills, 1–10. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer.

- Moncrieffe, Marlon. 2018a. ‘Arresting ‘epistemic violence’: Decolonising the national curriculum for history’. Dec 6, 2018. British Educational Research Association, https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/arresting-epistemic-violence-decolonising-the-national-curriculum-for-history.

- Moncrieffe, Marlon. 2018b. “Teaching and Learning About Cross-Cultural Encounters Over the Ages Through the Story of Britain’s Migrant Past.” In Advancing Multicultural Dialogues in Education, edited by Richard Race, 195–214. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Morley, Neville. 2010. The Roman Empire: Roots of Imperialism. London: Pluto Press.

- Morley, Neville. 2018. Classics: Why it Matters. Cambridge: Polity.

- Morris, Mathew. 2016. Between road and river: Investigating a Roman cemetery in Leicester. Current Archaeology https://archaeology.co.uk/articles/features/between-road-and-river-investigating-a-roman-cemetery-in-leicester.htm.

- Morris, Mathew, Richard Buckley, and Michael Codd. 2011. Visions of Ancient Leicester: Reconstructing Life in the Roman and Medieval Town from the Archaeology of Highcross Leicester Excavations. Leicester: University of Leicester.

- Moshenska, Gabriel, Sarah Dhanjal, and Don Cooper. 2009. “Building Sustainability in Community Archaeology.” Archaeology International 13/14: 94–100.

- Osler, Douglas. 2004. ‘Don’t waste your tears on Classics’, Times Educational Supplement, 30 April 2004. https://www.tes.com/news/dont-waste-your-tears-classics.

- Pearson, Michael, and Michael Shanks. 2001. Theatre/Archaeology. London: Routledge.

- Perry, Sarah, and Matthew Johnson. 2014. “Reconstruction art and Disciplinary Practice: Alan Sorrell and the Negotiation of the Archaeological Record.” Antiquaries Journal 94: 323–352.

- Politopoulos Aris, Mol, Boom Angus A. A., H. J. Krijn, and Csilla. E. Ariese. 2019. “‘“History Is Our Playground”: Action and Authenticity in Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey’.” Advances in Archaeological Practice 7 (3): 317–323.

- Polm, Martijn. 2016. “Museum Representations of Roman Britain: A Post-Colonial Perspective.” Britannia (society for the Promotion of Roman Studies) 47: 209–241.

- Renault, Mary 1958. The King Must Die. London: Longmans, Green Co.

- Reynard, Anna. 2020. “Classics at Lionheart Trust.” The Journal of Classics Teaching 21: 84–85.

- Riordan, Rick. 2013. Percy Jackson and the Lightening Thief. London: Penguin.

- Sanders, Karin. 2009. Bodies in the Bog and the Archaeological Imagination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Savani, Giacomo, Sarah Scott, and Mathew Morris. 2018. Life in the Roman World: Roman Leicester. Leicester: University of Leicester.

- Savani, Giacomo, and Victoria Thompson. 2020. “Ambiguity and Omission: Creative Mediation of the Unknowable Past.” In Researching the Archaeological Past Through Imagined Narratives. A Necessary Fiction, edited by Daniel van Helden, and Robert Witcher, 210–237. London: Routledge.

- Score, Vicki. 2012. Hoards, Hounds and Helmets: A Conquest-Period Ritual Site at Hallaton, Leicestershire, Leicester Archaeology Monograph 21. Leicester: University of Leicester.

- Score, Vicki. 2013. Hoards, Hounds and Helmets. The Story of the Hallaton Treasure. Leicester: University of Leicester Archaeological Services.

- Scott, Sarah. 2017. ““Gratefully Dedicated to the Subscribers”: The Archaeological Publishing Projects and Achievements of Charles Roach Smith.” Internet Archaeology 45.

- Scott, Sarah, and Jane Webster. 2003. Roman Imperialism and Provincial Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Searle, Emma, Lucy Jackson, Michael Scott, et al. 2018. “Widening Access to Classics in the UK: How the Impact, Public Engagement, Outreach and Knowledge Exchange Agenda has Helped.” In Forward with Classics. Classical Languages in Schools and Communities, edited by Holmes Henderson. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Shanks, Michael. 2012. The Archaeological Imagination. Walnut Creek: Left Coast.

- Simon, Nina. 2016. The Art of Relevance. Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0.

- Smith, Charles Roach. 1848. Collectanea Antiqua, Etchings and Notices of Ancient Remains, Illustrative of the Habits, Customs and History of Past Ages, Vol.1. London: John Russell Smith. http://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/OXVU1:LSCOP_OX:oxfaleph012213330.

- Smith, Katherine E., Justyna Bandola-Gill, Nasar Meer, Ellen Stewart, and Richard Watermeyer. 2020. The Impact Agenda. Controversies, Consequences and Challenges. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Smith, Laurajane, and Emma Waterton. 2012. “Constrained by Common Sense: The Authorized Heritage Discourse in Contemporary Debates.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Archaeology, edited by Robin Skeates, Carol McDavid, and John Carman. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stead, Henry, and Edith Hall. 2015. Greek and Roman Classics in the British Struggle for Social Reform. London: Bloomsbury.

- Stone, Peter, Donald Henson, and Mike Corbishley. 2004. Education and the Historic Environment. London: Routledge.

- Stone, Peter, and Brian Molyneaux. 1994. The Presented Past: Heritage, Museums and Education. London: Routledge.

- Thomas, R., J. Harvey, J. Browning, and P. Liddle. 2019. “A Medieval Hunting Lodge at Bradgate Park, Leicestershire.” Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society 93: 169–197.

- Tomlin, Roger. S. O. 1988. “The Curse Tablets.” In The Temple of Sulis Minerva at Bath, 2: Finds from the Sacred Spring, Oxford University Committee for Archaeology Monograph 16, edited by Barry Cunliffe, 59–277. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Tomlin, Roger S. O. 2003. ““The Girl in Question”: A new Text from Roman London.” Britannia (society for the Promotion of Roman Studies) 34: 41–51.

- Tomlin, Roger S. O. 2008. ““Paedagogium and Septizonium”: Two Roman Lead Tablets from Leicester.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 167: 207–218.

- Tomlin, Roger S. O. 2009. “III. Inscriptions.” Britannia (society for the Promotion of Roman Studies) 40: 313–363.

- Tringham, Ruth. 2019. “‘Giving Voice (Without Words) to Prehistoric People: Glimpses Into an Archaeologist’s Imagination’.” European Journal of Archaeology 22 (3): 338–353.

- Van Dyke, Reinhard M., and Ruth Bernbeck. 2015. Subjects and Narratives in Archaeology. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

- Wallace, Jennifer. 2004. Digging the Dirt: The Archaeological Imagination. London: Duckworth.

- Winkler, Martin M. 2004. Gladiator: Film and History. Malden: Blackwell.

- Wyles, Rosie, and Edith Hall. 2016. Women Classical Scholars: Unsealing the Fountain from the Renaissance to Jacqueline de Romilly. Oxford: Oxford University Press.