ABSTRACT

Since the initiation of the community based Nunalleq Archaeological Project in 2009 near the Yup’ik village of Quinhagak, in southwest Alaska, more than100,000 artefacts have been recovered from the eroding coastline of the Bering Sea. This has provided an unprecedented view into Yup’ik life before contact and has also led to a revival of traditional cultural practices in the community. The collection is now permanently deposited in Quinhagak under the curation of the descendant community, and on display in the Nunalleq Culture and Archaeology Center. In this paper we describe the events surrounding the public opening of the Center in 2018 and discuss principles of community collaboration and practice that strengthen partnerships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous collaborations and how they can be sustained long term.

In memory of Stephan Jones

This collection is of paramount importance for the local community of Quinhagak, where the Nunalleq site and artefacts have already become embedded into local history and cultural heritage. Furthermore, it is of vital importance to our understanding of the cultures of southwest Alaska and the North American Arctic. The Yukon-Kuskokwim delta of over 130,000 square kilometre is homeland to the Yupik, the largest Indigenous people in Alaska (Mollenkamp Citation2023), yet its rich pre-contact culture is known only through a limited number of excavations (Frink Citation2016; Kowta Citation1963; Oswalt Citation1952; Oswalt and Vanstone Citation1967; Redding-Gubitosa Citation1992; Shaw Citation1998; Skinner Citation2019).

The permanent presence of a collection of this magnitude in a source community of this size is ground-breaking. Among scientific and community leaders with a long-term involvement with the project there was a keen sense that it was important to celebrate this milestone. In an attempt to involve all the different interest groups, and to combine both western and Yup’ik ways of celebration, the week leading up to the opening of the Culture Center was marked by a ‘Yup’ik Culture Fest’, including a stakeholder workshop and a series of arts workshops celebrating Yup’ik cultural heritage. The community festivities culminated on the opening day with a traditional potluck feast and performance by the Quinhagak Dancers’.

Here we give an overview of the activities leading up to the grand opening, with the aim of discussing practices that strengthen partnerships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous collaborators that have combined to increase community engagement over the long term. The ethos of the Nunalleq project since its inception has been collaborative, following inclusive methodologies, allowing Indigenous perspectives and knowledge to inform archaeological interpretations, and co-creating academic and outreach products (Knecht and Jones Citation2019). It was important that these aspects were also recognized in the opening celebrations and inviting guests to the community. Hosting a feast for guests from other villages, sharing food and gifts, as well as performing songs and dances are intrinsic elements of Yup’ik hospitality. Traditional intervillage celebrations would take place throughout winter in a qasgiq, a men's community house, to honour the relationships between the living people, animals, spirits and ancestors (e.g. Fienup-Riordan Citation1996).

The Nunalleq project

The Nunalleq project was an altogether novel undertaking in Yup’ik country when it first started,Footnote1 but years of collaboration has built the solid foundation of trust relationships that made local curation of the Nunalleq collection possible. Excavations revealed a multitemporal settlement dating to the late pre-contactFootnote2 period AD 1570–1675 (Ledger et al. Citation2018) of unprecedented complexity and level of preservation (Knecht and Jones Citation2019). Thousands of organic and non-organic artefacts, including objects as fragile as grass basketry, as precious as walrus ivory artwork, and as rare as complete wooden dance masks, piece together the daily and ceremonial life of Nunalleq (The Old Village – named so by local EldersFootnote3).

The Nunalleq site is located on land owned by the local ANCSA village corporation of Quinhagak, Qanirtuuq Inc. Under US law, archaeological sites and artefacts within them remain the property of private landowners, including Alaska Native Corporations. According to the agreement between the corporation and the research team, at the end of each field season, the archaeological finds were transported to Scotland, to the University of Aberdeen, for preservation, curation and research purposes. This was done under the mutual understanding that the collection would be returned to Alaska at the end of the project. The initial plan was to reposit the collection in one of the already existing Alaska-based museums: in Anchorage, Fairbanks or the regional hub, Bethel. However, over the years, as the archaeological project became progressively more deeply rooted in the community, the idea of bringing the collection ‘back home’ also began solidifying. The final decision to make this a reality was taken by Qanirtuuq Inc. at a board meeting in 2016 (Hillerdal, Knecht, and Jones Citation2019). A pre-school building was donated by the School District: it was moved to the village centre in 2017 and equipped by the corporation with museum grade materials to house the substantial collection. The new facility began serving immediately that year as an archaeological lab and repository, with the finds being cleaned, conserved and curated on location in Quinhagak.

Prior to establishing the lab in Quinhagak, sending the artefacts off to the other side of the planet at the University of Aberdeen was necessary to stabilize and record this fragile and unique collection. The sheer bulk of the finds was daunting- every year we packed and shipped scores of trunk-sized totes of artefacts and samples to Scotland. For all the man-hours that go into excavation, the post-excavation part is by far the most time-consuming, and neither the expertise nor human resources were available in Quinhagak at the time. At the University of Aberdeen, much of this capacity was found in students volunteering in the lab under the guidance of Rick Knecht, but also professional conservators employed to the project and expert consultation from the University of Aberdeen Marischal Museum. Years of hard lab work cleaning, conserving and cataloguing artefacts finally culminated in the collection being shipped back home. After three months of safe packing for shipping, including building special padded boxes for delicate artefacts like masks, 80 crates of carefully conserved artefactsFootnote4 left Scotland with destination Quinhagak.

Over the years, the presence and persistence of the archaeological effort has earned the trust of the people in Quinhagak, but with the excavations winding down, one question became more and more central: how to ensure that this effort continued over the long-term? New paths needed to be forged to sustain academic – community collaboration and keep building capacity to eventually reach the point where a community-based Culture Center can be self-efficient and fully autonomic.

The culture center

Since its inception, the Nunalleq archaeology project has been steadily integrated into the Quinhagak community with full and heartfelt participation and engagement from its members (see Knecht and Jones Citation2019, 30). The everyday engagement has been closely linked to excavation and archaeological activity: village residents were frequently visiting the site, helping with excavation and screening, and the lab, sharing their local knowledge and oral histories. The opening of the Culture Center provided a new context for collaboration beyond excavation.

Yup’ik communities today are suffering under lingering colonial structures, continuously fighting against cultural and social marginalization, economic exploitation and under-compensation for the extraction by outsiders of the natural resources, all with the additional stressors of rapid climate change (cf. Britton and Hillerdal Citation2019). Elders in the community are deeply concerned that younger generations are becoming estranged from their traditional Yup’ik lifeways and values. Reconnecting with traditional culture has proven to be one of the most effective ways of improving wellness amongst Native youth (e.g. Rasmus et al. Citation2019). The Nunalleq project was initiated to target these urgent local concerns, also shared by the whole region. The goal was to find new avenues to convey traditional knowledge to younger people as well as address the combined effects of climate change on threatened cultural heritage. The Culture Centre supports these goals by offering a meeting point where essential conversations and learning about Yup’ik culture could take place, restoring some the functions of the traditional qasgi, community meeting houses that once served as the beating cultural hearts of Yup’ik villages.

The Nunalleq Culture and Archaeology Center became the first Alaska Native owned and village-based archaeological repository in the Yup’ik culture area. The Culture Center is operated by the non-profit incorporation Quinhagak Heritage Inc., QHI, on behalf of the community of Quinhagak. Following the Nunalleq project’s objectives, the Culture Center was established to safeguard Yup’ik culture heritage for the sake of future generations. The Centre also ensures that traditional cultural knowledge and local expertise can fully inform the curation and research of the collection. Hence, the stated mission of the Culture Center is ‘to preserve and restore the Yup’ik culture and traditions’ (Quinhagak Heritage CitationInc.). The Culture Center preserves not only the material culture collection, but also the immaterial cultural layers and meanings that it embodies: ancestral history, traditional Yup’ik values, culture, and subsistence practices.

The Culture Centre has already seen its setbacks, not least the tragic premature death of its first director, Stephan Jones in 2019. Despite this, before the restrictions imposed on village life by COVID-19 in 2020, the Culture Centre had already started to function as a cultural hub, frequently visited by incoming tourists, but more importantly recurring visitors from the local school, and serving as a venue for regular dance practises by the local Yup’ik dance group. As COVID restrictions have eased, the Culture Center is once again a busy place.

Stakeholder workshop

The return of an immensely important archaeological collection to a remote Indigenous village is an exceptional event with no set protocols. Hence, these had to be established ad hoc in a collaborative dynamic between community leaders and the scientific team. The archaeological collection is a significant cultural asset for the local community and taking full control over it provides both opportunities and challenges. The sustainability of the Culture Center requests a transparent dialogue between the researchers and museum professionals on one hand, and the Native community and culture bearers on the other. This, in turn, demands personal commitment and many forms of support.

The main aim of the stakeholder’s workshop was to bring together local decision makers, researchers and museum professionals to foster collaboration across academic and non-academic boundaries and discuss the needs and future prospects of the Culture Center. The workshop gathered 28 participants in total (), including Quinhagak Elders, Qanirtuuq Inc. and QHI board members, representatives from the Native Village of Kwinhagak and Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat school as well as the Nunalleq archaeologists and regional professionals of the cultural management sector including AVCPFootnote5 (Association of Village Council Presidents). Alaska key museum institutions were represented by Yupiit Piciryarait Museum in Bethel, the Anchorage Museum, the Museum of the Aleutians, the Alutiiq Museum, the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center, with the added international perspective from University of Aberdeen Museums.

The message from – and for – the community was voiced at the beginning of the workshop by Elders Grace Hill and Joshua Cleveland, and community leader Warren Jones:

One of the main reasons behind the decision to excavate Nunalleq was to rescue and save the artefacts for the younger generation— “for our kids to never forget where we are from”. In the face of social and cultural changes, “you are Yup’ik regardless”. The Culture Centre will help the community stay healthy and (re)connect to a historic and traditional Yup’ik past. The aim of the Culture Centre is to serve the Yup’ik community to preserve Yup’ik heritage, support a Native way of life, and serve as a platform for culture revitalization (Hillerdal Citation2018).

An important outcome of the workshop was to establish a support network of professional museums in aid of the daily operation of the culture centre. Although not formalized in any agreements at the time, training opportunities have since been offered by the Anchorage Museum, as well as several in-kind donations from the State museums have been made.

The stakeholder workshop captured the more formal and academic aspects of the Culture Center opening celebrations, involving the interested parties on the local, regional and international level. However, the accomplishment was also celebrated through art and culture workshops following Yup’ik traditional teaching methods, intergenerational dialogue and learning by practice.

Art workshops

The week leading up to the inauguration of the Culture Centre, August 6–11, was marked with a series of art and craft workshops that engaged the local community in traditional and contemporary tangible and performing arts. The Arts possess a unique ability to transcend time and engage the past with the present (cf. Hillerdal Citation2017). Over the years at Nunalleq, it has become apparent that artists communicate effortlessly with the archaeological material. The archaeological material has in various ways prompted local engagement with traditional cultural practices (see Hillerdal et al. Citationaccepted), and local Yup’ik carvers have found immense inspiration in the artwork made by their ancestors (see Mossolova and Michael Citation2020).

To capture a range of different cultural activities, both local artists and established Yup’ik artists from outside of Quinhagak were invited to lead a variety of art workshops. Participants of the workshops moved between the contemporary and the traditional, the present and the past. Six out of eight workshops focused on traditional Yup’ik crafts present in the archaeological collections, the rest represented more exploratory interactions with the past through contemporary arts practice. Together, they conveyed a message of a strong continuity, but also a dynamic Yup’ik culture ready to take younger generations into the future. Since archaeological finds served as a point of engagement and inspiration, one of the objectives was also to give the Quinhagak residences an opportunity to view and handle their cultural legacy first hand and more fully explore it from an artistic point of view.

The tangible arts workshops were planned as three-day events and had between four and ten participants. They were led by local artists Sarah Brown, Willard Church and John Smith, regional artist Mike McIntyre, and contemporary Yup’ik artists Drew Michael and Ryan Romer. A performing art workshop was led by a frontman of the well-known Yup’ik music group Pamyua, Philip Blancette (with the support of their guitarist Ivan Night) and dancer and choreographer, Emily Johnson. The Quinhagak dancers also had a workshop with Yup’ik master artist, storyteller and dancer, Chuna McIntyre, who gifted them a song to perform at the opening celebration. The workshopsFootnote6 were documented by two young local photographers Crystal Carter and Carl Nicolai (Nicholai and Carter Citation2018),Footnote7 and parts of their narrative will be retold here (in words and pictures).

Sarah Brown is one of few people in Quinhagak still practising traditional skin sewing – a crucial survival skill in the Arctic (Fienup-Riordan Citation2007, 305). Participants in her workshop got the opportunity to learn these skills through making sealskin toys or a pair of baby booties from sealskin: ´Skin sewing is an important cultural activity that young participants can learn because our ancestors sewn together everything they wore before we got technology, they sewn everything they had and made everything by their own hands which is amazing’ (Nicholai and Carter Citation2018).

John Smith is a Quinhagak Elder and master carver. Originally from Hooper Bay, he learned to carve as a child, and the traditional Yup’ik ways of teaching are important in his approach to teaching: learning by watching and listening and letting your hands work ().

While running errands for his mom, he’d stop by the qasgiq, a place where men gathered and where young boys gained skills and knowledge through stories and guidance from the older men. He said that he learned by observing what they were doing and by listening to what they had to say. He also said that he would go outside, pick up a random piece of wood and start carving. Through that story, he told his students that we all have a talent; we just have to get off of our butts and learn how to utilize that talent (Nicholai and Carter Citation2018).

Figure 2. Christian Alexie Jr intensely concentrating on the task at the Ivory carving workshop. Picture by Carl Nicholai and Crystal Carter, used with permission.

Willard Church owns his local business making and selling uluaqs – multi-purpose knives used for a range of different tasks (). The Nunalleq collection contains a multitude of different uluaqs, ranging in size from less than 10 cm long made for sewing to the bigger ones, up to 25 cm long, for processing larger mammals etc. The uluaqs are instantly recognized today, although the ground slate blades of the past have been replaced by steel, the overall highly functional design has not changed much, and they remain in constant use in any Yup’ik household. Willard is also a local historian and has a keen interest in the Yup’ik past as well as traditional subsistence. He has been learning from the ancient artefacts and technologies reflected in the Nunalleq collection and has found inspiration for his own work there: ‘Willard expressed that it is important to think about what the maker prefers, who the uluaq is for, and what the uluaq will be cutting before designing your uluaq because uluaqs come in all shapes and sizes’ (Nicholai and Carter Citation2018).

Figure 3. Darryl Small Jr showing his work in progress at the uluaq workshop. Picture by Carl Nicholai and Crystal Carter, used with permission.

The performing arts were represented in a dance and music workshop with Emily Johnson, Philip Blanchette, and Ivan Night. These artists are strong messengers for Indigenous values and equity. Emily Johnson, an award-winning contemporary dancer, choreographer and artistic director of her own dance company Catalyst (Johnson Citationn.d.), is working actively towards decolonizing and indigenizing the world of performing arts (i.e. Johnson Citationn.d.(b)). In her words, ‘through dance, theater, story, and song, through reciprocal relationships, the power is surging now and flowing back. As it should. A reciprocal flow of power and inspiration’ (Johnson Citation2018, 19). In a similar manner, through contemporary reinterpretation of traditional melodies, Pamyua sees their music creating a ‘platform to share Indigenous knowledge and history’ (Pamyua Citationn.d.). Music and dance become an instrument of empowerment and a catalyst (NB Emily) for change. ‘As our Indigenous stories and songs and plights and brilliance and lands are known, as we are recognized, we can better effect the needed change for this land – in policies, in relationships, in consciousness’ (Johnson Citation2018, 20). Emily got to know the project first hand when she joined the Nunalleq excavations as a volunteer archaeologist for the 2015 field season.

For their collaborative dance and music workshop Emily and Phillip ‘used one of Quinhagak’s yuraq songs about our river called Qanirtuuq Upnerkami. Using the yuraq song as a basis, they modernized and adapted it into a louder and more free-flowing yuraq song where the participants were invited to dance and sing with their whole being’ (Nicholai and Carter Citation2018).

The intersections between past and present, traditional and contemporary are also explored in the art by Yup’ik artist Drew Michael, whose motto is ‘to protect and activate our culture’ (Michael Citationn.d.). Drew is a mask maker and works primarily with wood. He perceives the practice of wood carving as directly linked to the work of past generations: ‘With each cut I make through wood I have to remember the long line of people who came before me doing the same motions, telling stories about our connection to the world seen and unseen’ (Michael Citationn.d.(b)). Drew also participated in the Nunalleq excavations back in 2017 when he found a mask made and used by his ancestors ∼500 years ago. This experience has had a profound impact on Drew and influenced his own artistic practice (cf. Mossolova and Michael Citation2020). For his workshop, Drew chose to experiment with bentwood (), a technique frequently seen in the Nunalleq material, primarily vessels, ladles, drums, and mask hoops, but no longer part of traditional crafts work practises in the village.

Figure 4. Leah Mark preparing the wood for bending at the bentwood vessel workshop. Picture by Carl Nicholai and Crystal Carter, used with permission.

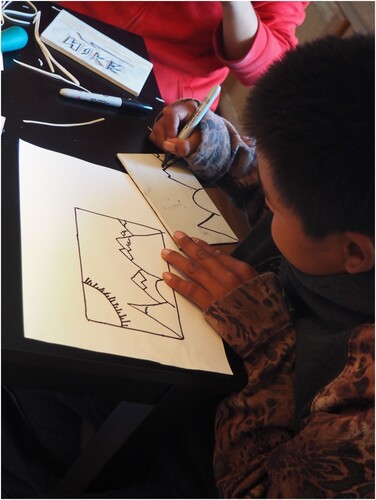

Ryan Romer is a contemporary Yup’ik artist working primarily in graphic design (). Ryan too is using his Yup’ik heritage as a source of inspiration for his artwork: ‘his paintings and printmaking are inspired from experiences, stories and folklore from the Y-K Delta, capturing nomadic lifestyles as they exist in contemporary Alaska and weaving in Indigenous values and knowledge along the way’ (Ryan Romer – Aywaa Citationn.d.). His art is an active and contemporary critique of a soulless modern way of life: ‘Every image is intended to present a possible parallel universe — a storyline in motion that the viewer may accept as an alternative to the Western, capitalist structures we live in today’ (Ryan Romer – Aywaa Citationn.d.). For his workshop, Ryan had students making relief prints. Students were encouraged to explore their identities by engaging with symbols found in the collection and designs important to their modern culture, to create a print full of meaning for themselves.

Figure 5. Designing an image for printing workshop. Picture by Carl Nicholai and Crystal Carter, used with permission.

Mike McIntyre is a Yup’ik mask maker who upholds the traditional arts protocols and prefers working with natural materials. To Mike, traditional means something intuitive, intergenerational, and linked to storytelling (Mossolova Citation2020, 371). Continuity and learning are thus indispensable from the very definition of ‘tradition’. This standpoint was expressed in his approach to teaching the workshop: ‘After a brief demonstration of the different kinds of masks, he handed everyone a carving tool to begin their mask. He gave the participants the creative freedom to design and carve what he or she wanted’ (Nicholai and Carter Citation2018).

Mask making is a tradition of high communal importance to the Yup’ik. It reflects the ways in which Yup’ik people viewed the reciprocal relationships between animals, humans, and spirits, all components of a sentient layered universe (see Fienup-Riordan Citation1987; Citation1996). However, mask making practices have been almost forgotten in Quinhagak for generations due to the abolition of this tradition by the Moravian Church in the early 1900s (Mossolova and Michael Citation2020). With the reclamation of pre-colonial cultural traditions came the opportunity to reintroduce mask making to Quinhagak.

The parallel timing of the stakeholder and art workshops was important to enable synergies between them. Ben Charles was invited to the stakeholder workshop as a representative of the Yupiit Piciryarait Museum in Bethel, but as a talented Yup’ik artist he could not stand aside observing others carving masks during the mask-making workshop. He carved a mask inspired by a walrus-human transformation mask discovered at Nunalleq and gifted it to the Quinhagak Dancers (Mossolova Citation2020, 376). The mask was danced by Peter Smith during the grand opening celebration – the first mask danced at a Quinhagak communal gathering since the disruption of masked dance tradition in the village a century ago. The ‘Song for Nunalleq’ was an important part of the celebration (Watterson and Hillerdal Citation2020).

Together all these workshops were a strong manifestation of the power of Yup’ik culture and the dynamic force that a living, practised culture has in the contemporary world. ‘Traditional’ does not equate to ‘passive’. In a colonial setting, with constant external pressures to either conform (to Western society) or perform (your Indigeneity), the choice to adhere to traditional practices is an act of both resilience and resistance (for a relevant comparison from Sápmi see Nylander Citation2023).

Grand opening of the culture centre

Just ten days prior to the grand opening, the artefacts finally arrived from Aberdeen (to the great relief of everyone involved ()). The storage cabinets that were initially supposed to be shipped with the collections were refused by the shippers which led to a frenzy among Qanirtuuq Inc. carpenters to build custom made drawers for storage and display. Explicitly opposing the traditional museum ‘glass case’ exhibit of artefacts, there is nothing separating the visitor from the artefacts at the Nunalleq Culture Center where they can be easily accessed, handled and studied closely. This approach is a continuation of the practice established in the yearly ‘Show and Tell’ that used to close every excavation season. At these events, the entire village was invited to meet the most spectacular artefacts, to tell their stories, offer their interpretations, to look, touch, and ponder. These events have been instrumental for anchoring the project in the community. They introduced the finds to community members and rooted a sense of ownership. Strict museum protocols of displaying and handling have not always been rigidly followed, but ‘ideal handling procedure’ does not always equate to ‘best practice’. Direct community engagement with a collection entails some adjustments.

Figure 6. Artefacts arrive in 80 crates only 10 days before the opening celebration. Picture by Rick Knecht.

On the day of the opening, hundreds of people had gathered by the Culture Center: Elders, community leaders, locals of all ages, archaeologists, and invited guests. So came the long-awaited moment: Grace Hill and Warren Jones cut the ribbon (made symbolically from a roll of flagging tape used at the site) and the doors opened (). A long line of Elders, invited to be first to see the collection, stood before the opened drawers of artefacts with smiles and tears, some seeing the artefacts up close for the first time. Warren Jones describes this day as ‘a weight off his shoulders’. It was a very emotional moment for everyone involved (). An era had come to an end – and a new one had begun.

Figure 7. Warren Jones and Grace Hill of Qanirtuuq Inc. cutting the ribbon at the opening of the Culture Centre (also pictured Annie Wassilie and Jamie Small). Picture by Katie Basile/KYUK, used with permission.

Figure 8. Small visitors studying arefacts in the Culture Center on the day of the opening. Picture by Rick Knecht.

The celebration continued with a rich potluck – a traditional sharing of Native foods. The highlight of the evening, the Quinhagak Dancers performed their Song for Nunalleq, that they had written especially for the occasion, and spent many evenings rehearsing.Footnote8 It followed a storyline where the young people of Quinhagak turned to their ancestors at Nunalleq with a question: ‘How did you live?’. The chorus was a humoristic rendering of the archaeological process through the eyes of the dancers; the excitement of finding an artefact, just to conclude it is nothing after all, and toss it away – a scenario that many of them had experienced first-hand as volunteers at the dig site.

The award-winning documentary Children of the Dig by Alaskan filmmaker, Joshua Branstetter also premiered during the celebration (Branstetter Citation2018). Josh visited the excavation in 2017 and produced a fine-tuned account of the community’s archaeological journey. This project was yet another example of creative synergies born from the archaeological excavation.

Discussion

The village of Quinhagak has c. 700 inhabitants, the absolute majority of which are Native Alaskans. Economic opportunities are few, and the capitalistic economy does not offer equal terms in this, from the majority culture’s view, marginalized context. From an outsider's perspective the village can be described as remote. It is accessible only by bush plane or by boat, which results in very high prices in the village store. Commercial fishing, the main income for many villagers, has recurrently been suspended or limited in recent years. Many families live under national poverty levels, which makes traditional subsistence not only a cultural, but an economic, necessity. Large numbers of younger people move out of the village to for better opportunities. To take on stewardship of a such a rich archaeological collection is an enormous undertaking for any community, but especially for geographically isolated and economically marginalized villages like Quinhagak. It is not a commitment that has been made lightly. The years of collaboration has built local capacity and confidence to care for the archaeological material, curate it for the long term, and share it with the village and the world.

Reinforcing this confidence are the artefacts themselves, and the communicative power they have, as well as the wide exposure that a large-scale excavation has had in both regional and international media, as well as the academic world. The story of Quinhagak, the descendant community that in the wake of climate crisis managed nonetheless to safeguard their archaeological heritage, transcends scientific importance, and draws people in, creating an economic catchment of human capital that extends far beyond Quinhagak. Equally, the per capita engagement is higher in Quinhagak than other community centres in Alaska. This is what makes the Community Center both possible and sustainable.

The presence of the artefacts in Quinhagak, under the care and control of the descendant community brings to the village an unprecedented empowerment through accessibility, ownership, and authorship.

The Nunalleq Culture Centre in Quinhagak turns the question of accessibility on its head. It is an accessibility that is defined in qualitative terms, rather than quantitative: instead of being accessible to many interested but less invested visitors in faraway cities, this collection is accessible to a small descendant community, to which it matters the most. Such accessibility is direct in a way that it enables people to interact with artefacts without a mediator and without a wall of glass between descendants and their heritage.

A conceptual ‘barrier’ – looking at artefacts behind glass – is, however, even less problematic, than the very pragmatic barrier of economic costs. Due to the high cost of flights and hotels in the cities, most people in the village cannot afford a visit to a museum. When artefacts are housed locally in the community, people can go and see them on their own time.

The last three decades have seen a dramatic change in the relationship between museums and source communities, towards a more inclusive mindset, where consultation and collaboration with the descendant communities are now considered rather a norm than exception (e.g. Harrison, Byrne, and Clarke Citation2013; Peers and Brown Citation2003; Phillips Citation2005). Museums have redefined source community members as rightful authorities on their own heritage, and recognize they have a moral and ethical obligation to prioritize the Indigenous voice in interpretation and display. However, the debates about whether these new relationships remain asymmetrical and who owns the intellectual control over collections continue (e.g. Boast Citation2011; Lonetree Citation2012; Mithlo Citation2004).

Authorship means that one produces, owns and has an ability to narrate the story oneself. Bringing the story home is more than including Indigenous voices to interpretation of artefacts – it empowers the community to be effective and primary stewards of their cultural heritage. It allows not only for power sharing but the creation of an altogether different hierarchy to Indigenous culture heritage management. When the power balance shifts from the centre to the periphery, everything shifts with it into an entirely different order, that allows the periphery to become the centre (cf. Boast Citation2011, 67). Decision making, the power to invite, the power to restrict, lies with the community. The Nunalleq Culture Centre acknowledges that ownership entails caring, responsibility, as well as the autonomy to decide.

The presence of the collection in Quinhagak enables multifaceted curation that is sensitive to the immaterial values of the collection, anchoring it in Yup’ik identity and values. The descendant community members see the collection as a gift from their ancestors (see Mossolova and Michael Citation2020) that allows them to stay rooted in their culture and connect to their forebears. One example of this dialogue through time played out at the culture festival: during his visit to the collection, Chuna McIntyre honoured the ancestors who lived at Nunalleq by offering a song and beads that have now become part of the collection, curated next to the masks they were offered to.

Many Indigenous collections have been removed from their local context, making them hardly (if at all) accessible to the descendant communities (Linn et al. Citation2017; Stevens Citation2016). The Nunalleq collection, on the contrary, is readily available for the local community, but remote from a national as well as an international perspective. Many points can be raised against such an unusual decision – from limited exposure to lack of capacity to adhere to formalized museum standards, but in the end, it comes down to which values should be prioritized. For all parties involved in the decision making, the benefits of having the collection in the source community outweighs any other argument. Nonetheless, the Culture Centre must also work for keeping the community interest alive through culture programmes and exhibitions, through multiple outreach contexts – local, regional, and global. Crucially, different culture programmes and outreach activities should serve to lift local knowledge and skills, recognizing and cherishing local expertise (see Postscript).

Conclusion

Archaeology is of the past, but it gains importance in the present, and retains importance with the future in mind. A scientific value of an archaeological site and/or collection like Nunalleq is indisputable, but when engaged and embedded in a descendant community its importance becomes many times multiplied. A collection stored away in a faraway museum is muted (cf. Haakanson in Haakanson Citation2015; Pullar, Knecht, and Haakanson Citation2013) until it is re-ignited by the reconnections made with living people, it is a tree stump with no crown. The Nunalleq collection is active, it is vibrant and loud. It lives on in every working hand, in every story told, in every drumbeat; this is Nunalleq – not earth and stone and wood, but people – then and there, now and here, looking forward into the bright hopes for the future.

Postscript

The community workshops, planned as future activities for the Culture Center at the stakeholder workshops, have since been established. In 2019, the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Centre, represented at the stakeholder workshop by Aron Crowell, sponsored a series of community workshops on making twined grass bags (Crowell Citation2019; Hillerdal et al. Citationaccepted), a grass weaving technique represented in the archaeological material, but not in wide practice in Yup’ik communities today (Masson-MacLean, Masson-MacLean, and Knecht Citation2019, 90–95). A similar ambition – to revive an art practice of the past – inspired a fish skin tanning workshop coordinated by Cheryl Heitman in 2021. Although the traditional methods of tanning or preserving skins for use have been lost, the aspiration of the workshop was to bring fish skin as a material back into practice. Informed by the archaeological collection, salmon at the workshop were processed, scraped and skinned with a replica of an uluaq from Nunalleq made by Willard Church. Workshops like these continue the engagement with, and reinforce the importance of, the Nunalleq collection in the community. They are also an efficient way of expanding engagement in the community and attract interest from new groups of people or individuals. Thus, solidifying the substructure of community value, so vital for the long-term survival of the Community Center.

One of the ideas discussed during the stakeholder workshop in relation to wider accessibility was an online exhibition. Since then, this idea has been realized; Charlotta Hillerdal and Alice Watterson, partnering with Qanirtuuq Inc. and QHI, were awarded a grant to develop the co-curated Nunalleq Digital Museum, a project currently underway, to be completed in spring 2023. This project has also included traditional skills workshops in wood carving and drum making, taught by Yup’ik master craftspeople from the region.

The challenges for the Culture Center today can be identified mainly in economic terms and limited capacity. However, the Culture Centre – which was officially renamed as Nunalleq Museum in 2021 – remains a central priority for the community of Quinhagak and is generating new opportunities that would otherwise not be available. The Nunalleq Museum has yet to make its full impact on the region, but the effects of its existence are already rippling through the tundra landscape.

Acknowledgements

Firstly, we want to acknowledge the contribution by Stephan Jones, first Director of the Nunalleq Culture and Archaeology Center and Director of QHI, who is sadly no longer with us. Stephan was one of the organizers behind the cultural workshops and celebration, and had fate wanted differently, his name would be found among the authors of this paper. Thank you to Crystal Carter and Carl Nicholai for reporting on the culture workshops, and for the kind permission to use your beautiful pictures. We are grateful to all the artists who made the workshops possible, and to all the workshop participants who made them so successful and enjoyable. We also extend our thanks to two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on our paper. Thanks to everyone in Quinhagak who contributed to the Potluck and celebration, and special thanks to the Quinhagak dancers for your performance. We cannot leave without mentioning all the researchers and volunteers who have dedicated their time to Nunalleq over the years. Finally, we are extremely grateful to the people of Quinhagak for their constant support – without you none of this could have happened.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Charlotta Hillerdal

Charlotta Hillerdal has been working with Indigenous groups in Canada and Alaska for over 15 years. Her specialisms include archaeological theory, Indigenous archaeology, and community collaboration. She joined the Nunalleq project in 2010 as one of its co-leaders with a special focus on community engagement. Within this project she has been directing excavation and field schools, as well as community and stakeholder workshops. She had a leading role in developing the co-created digital Nunalleq Educational Resource, and is currently heading a project developing the co-curated Nunalleq Digital Museum. Charlotta is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland.

Anna Mossolova

Anna Mossolova joined the Nunalleq project in 2015 and has been conducting her archaeological and ethnographic fieldwork in Alaska since then. She was volunteering for the 'Alaska lab' at the University of Aberdeen, when the Nunalleq collection was there, and aided with packing and shipping artefacts back to Quinhagak in the spring of 2018. Anna defended her doctoral thesis ‘Mending the Breaks: Revival and Recovery in Southwest Alaska Mask-Making Tradition’ in 2020. Her work is driven by collaborations with Alaska Native artists and arts-based research methods. Currently, Anna holds a postdoctoral position at the Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo.

Rick Knecht

Rick Knecht has been doing archaeology and cultural preservation projects in partnership with Alaska Native communities for 40 years; on Kodiak Island, the Aleutians and the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. He has also worked with and for Indigenous communities in Micronesia on oral history, archaeological and museum projects. For the past 14 years he, along with colleagues and community members, have co-directed the Nunalleq Archaeological Project. He was founding director of three Alaskan institutions that hold locally recovered artifacts and celebrate Native cultures; the Alutiiq Museum on Kodiak, the Museum of the Aleutians in Unalaska and the Nunalleq Museum in Quinhagak. In 2022 Rick was awarded the Friends of First Alaskans Ted Stevens Award by the First Alaskans Institute, in recognition for support of Native issues and partnerships with Alaska Native communities. He is currently a Senior Lecturer in Archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland.

Warren Jones

Warren Jones is a lifelong resident of Quinhagak and has been a community leader for many years, serving in law enforcement, fisheries management and since 2006 as CEO of Qanirtuuq, Inc. the ANCSA Corporation for Quinhagak. He was instrumental in working with elders to build a consensus that allowed the Nunalleq Project to go forward and supplied its start-up funding through a grant from the Alaska Federation of Natives. Warren has coordinated local support and logistics for the Nunalleq project from the outset, which depended almost exclusively on local funds for its first four years. He led the repurposing of the Nunalleq Museum building, co-authored a number of academic papers and has been an articulate Native voice in world-wide media coverage.

Notes

1 For a comparable project in Alaska see Jensen (Citation2012).

2 The first Euro-American contact came to the Yup’ik country around the 1820s (Barker, Fienup-Riordan, and John Citation2010).

3 The historical name of the village, as preserved in local oral history, was Agaligmiut (Fienup-Riordan and Rearden Citation2013, 394).

4 Only the fragile grass artefacts, leather pieces and a portion of pottery, stayed behind, yet to be conserved.

5 Responsible for overseeing archaeological investigations in the region.

6 In addition, an archaeologist and digital artist Alice Watterson led a stop-motion workshop narrating the story of the attack that ended the Nunalleq settlement, which was included in the Nunalleq educational resource (see Watterson, Anderson, and Paxton Citation2019).

7 Crystal and Carl were hired to document the cultural workshops for the CIRI Foundation’s report ‘A journey to what matters’ (Nicholai and Carter Citation2018). They had developed their photography skill in a National Geographic Photo Camp run for young Quinhagak residents previously that summer, during which they explored themes related to archaeology, their past, traditions, village life, and ultimately what it means to be Yup’ik (Nunalleq Blog: National Geographic Photo Camp, Citation2018).

8 The full text of the song is cited in Watterson and Hillerdal (Citation2020).

References

- Barker, James H., Ann Fienup-Riordan, and Theresa Arevgaq John. 2010. Yupiit Yuraryarait/Yup’ik Ways of Dancing. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- Boast, Robin. 2011. “Neocolonial Collaboration: Museum as Contact Zone Revisited.” Museum Anthropology 34 (1): 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1379.2010.01107.x.

- Branstetter, Josua A. 2018. “Children of the Dig.” https://vimeo.com/294900082.

- Britton, Kate, and Charlotta Hillerdal. 2019. “Archaeologies of Climate Change: Perceptions and Prospects.” Études Inuit Studies 43 (1-2): 265–287. https://doi.org/10.7202/1071948ar.

- Crowell, Aron. 2019. “Renewing and Ancestral Art at Quinhagak: a Smithsonian Community Collaboration.” Accessed October 8, 2021. https://www.anchoragemuseum.org/about-us/museum-journal/museum-journal-archive/renewing-an-ancestral-art-at-quinhagak-a-smithsonian-community-collaboration/.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann. 1987. “The Mask: The Eye of the Dance.” Arctic Anthropology 24 (2): 40–55.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann. 1996. The Living Tradition of Yup’ik Masks. Agayuliyararput, Our Way of Making Prayer. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann. 2007. Yuungnaqpiallerput. The Way We Genuinely Live. Masterworks of Yup’ik Science and Survival. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann, and Alice Rearden. 2013. Erinaput Unguvaniartut. So Our Voices Will Live. Quinhagak History and Oral Traditions. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Language Center.

- Frink, Liam. 2016. A Tale of Three Villages. Indigenous-Colonial Interaction in Southwestern Alaska, 1740–1950. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

- Haakanson, Sven. 2015. “Translating Knowledge: Uniting Alutiiq People with Heritage Information.” In Museum as Process: Translating Local and Global Knowledges, edited by Raymond Silverman, 123–129. London: Routledge.

- Harrison, Rodney, Sarah Byrne, and Anne Clarke, eds. 2013. Reassembling the Collection: Ethnographic Museums and Indigenous Agency. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Hillerdal, Charlotta. 2017. Integrating the Past in the Present. Archaeology as part of Living Yup'ik Heritage. In Hillerdal, Charlotta, Karlström, Anna, and Ojala, Carl-Gösta (Eds.) Archaeologies of “Us” and “Them”. Debating History, Heritage and Indigeneity, 62–79. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hillerdal, Charlotta. 2018. Unpublished. ‘Living Heritage’ Workshop, Quinhagak, AK, August 8–11, 2018: Notes from the meeting.

- Hillerdal, Charlotta, Rick Knecht, and Warren Jones. 2019. “Nunalleq: Archaeology, Climate Change, and Community Engagement in a Yup’ik Village.” Arctic Anthropology 56 (1): 4–17. https://doi.org/10.3368/aa.56.1.4.

- Hillerdal, Charlotta, Alice Watterson, M. Akiqaralria Williams, Lonny Alaskuk Strunk, and Jacqueline Nalikutaar Cleveland. accepted. “Giving the Past a Future: community archaeology, youth engagement and heritage in Quinhagak, Alaska.” Études/Inuit/Studies.

- Jensen, Anne M. 2012. “Culture and Change: Learning from the Past Through Community Archaeology on the North Slope.” Polar Geography 35 (3-4): 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2012.710881.

- Johnson, Emily. 2018. “Land, Indigenous, People, Sky.” Peak Journal, 18–20.

- Johnson, Emily. n.d. “Emily Johnson/Catalyst.” Accessed March 25, 2021. http://www.catalystdance.com/.

- Johnson, Emily. n.d.(b). “Colonisation Rider.” Accessed March 25, 2021. http://www.catalystdance.com/decolonization-rider.

- Knecht, Rick, and Warren Jones. 2019. ““The Old Village”: Yup’ik Precontact Archaeology and Community-Based Research at the Nunalleq Site, Quinhagak, Alaska.” Études/ Inuit/Studies 43 (1-2): 25–52. https://doi.org/10.7202/1071939ar

- Kowta, Makoto. 1963. Unpublished. Old Togiak in Prehistory. Los Angeles.: University of California.

- Ledger, Paul, Véronique Forbes, Edouard Masson-MacLean, Charlotta Hillerdal, W. Derek Hamilton, Ellen McManus-Fry, Ana Jorge, Kate Britton, and Rick Knecht. 2018. “Three Generations Under One Roof? Bayesian Modeling of Radiocarbon Data from Nunalleq, Yukon/Kuskokwim Delta, Alaska.” American Antiquity 83 (3): 505–524. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2018.14.

- Linn, Angela J., Joshua D. Reuther, Chris B. Wooley, Scott J. Shirar, and Jason S. Rogers. 2017. “Museum Cultural Collections: Pathways to the Preservation of Traditional and Scientific Knowledge.” Arctic Science 3: 618–634. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2017-0001.

- Lonetree, Amy. 2012. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Masson-MacLean, Julie, Edouard Masson-MacLean, and Rick Knecht. 2019. “The Fabric of Basketry: Initial Archaeological Study of the Grass Artifacts Assemblage from the Nunalleq Site, Southwest Alaska.” Études Inuit Studies 43 (1-2): 85–105. https://doi.org/10.7202/1072715ar.

- Michael, Drew. n.d. “Drew Michael.” Accessed March 25, 2021. https://www.drewmichael.art/new-index.

- Michael, Drew. n.d.(b). “Drew Michael, Research and Discovery.” Accessed March 25, 2021. https://www.drewmichael.art/research/discovery.

- Mithlo, Nancy Marie. 2004. ““Red Man's Burden”: The Politics of Inclusion in Museum Settings.” The American Indian Quarterly 28 (3&4): 743–763. https://doi.org/10.1353/aiq.2004.0105.

- Mollenkamp, Daniel Thomas. 2023. “Largest Indigenous Groups in the U.S.” Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.investopedia.com/largest-indigenous-groups-in-us-6747515.

- Mossolova, Anna. 2020. “Innovation and Healing in Contemporary Yup’ik Mask Making.” Anthropologica 62: 365–379. https://doi.org/10.3138/anth-2018-0099.

- Mossolova, Anna, and Drew Michael. 2020. “Yup’ik Masks in the Precontact Past and the Contested Present.” World Archaeology 52 (5): 667–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2021.1993989.

- Nicholai, Carl, and Crystal Carter. 2018. “A Journey to what matters – Yup’ik Culture Fest Workshops 2018.” Accessed August 14, 2022. http://thecirifoundation.org/2018/10/02/a-journey-to-what-matters-yupik-culture-fest-workshops-2018/?fbclid=IwAR2B18nSGQ62VqFG-UA95H1c-5O4kmwLxPrOhagbuQtu2uJ-4tj1AE9QU_I.

- Nunalleq Blog “National Geographic Photo Camp.” Nunalleq (blog). July 25, 2018. https://nunalleq.wordpress.com/2018/07/25/national-geographic-photo-camp/

- Nylander, Eeva-Kristina. 2023. From Repatriation to Rematriation. Dismantling the Attitudes and Potentials Behind the Repatriation of Sámi Heritage. Oulu: University of Oulu.

- Oswalt, Wendell H. 1952. “Archaeology of Hooper Bay Village, Alaska.” Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska 1 (1): 47–91.

- Oswalt, Wendell H., and James W. Vanstone. 1967. The Ethnoarchaeology of Crow Village, Alaska. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Pamyua. n.d. “Pamyua.” Accessed April 20, 2021. http://www.pamyua.com/.

- Peers, Laura, and Alison K. Brown. 2003. “Introduction.” In Museums and Source Communities. A Routledge Reader, edited by Laura Peers, and Alison K. Brown, 1–16. London: Routledge.

- Phillips, Ruth. 2005. “Re-placing Objects: Historical Practices for the Second Museum age.” Canadian Historical Review 86 (1): 83–110. https://doi.org/10.3138/CHR/86.1.83.

- Pullar, Gordon, Rick Knecht, and Sven Haakanson. 2013. “Archaeology and the Sugpiaq Renaissance on Kodiak Island: Three Stories from Alaska.” Études/Inuit/Studies 37 (1): 79–94. https://doi.org/10.7202/1025255ar.

- Quinhagak Heritage Inc. Organizational Business Plan. Unpublished.

- Rasmus, Stacy M., Edison Tricket, Billy Charles, Simeon John, and James Allen. 2019. “The Qasgiq Model as an Indigenous Intervention: Using the Cultural Logic of Contexts to Build Protective Factors for Alaska Native Suicide and Alcohol Misuse Prevention.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 25 (1): 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000243.

- Redding-Gubitosa, Donna. 1992 – Unpublished. Excavations at Kwigiumpainukamiut: A Multi-Ethnic Historic Site, Southwestern Alaska. Los Angeles.: University of California.

- Ryan Romer – Aywaa. n.d. “Aywaa Story House.” Accessed May 26, 2022. http://aywaa.org/artists/ryan-romer/.

- Shaw, Robert D. 1998. “An Archaeology of the Central Yupik: A Regional Overview for the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, Northern Bristol Bay, and Nunivak.” Arctic Anthropology 35 (1): 234–246.

- Skinner, Dougless I. 2019 – Unpublished. Indigenous Archaeological Approached to Artifact and Household Analysis at Precolonial Yup’ik Village Temyiq Tuyuryaq (Old Togiak). University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- Stevens, Scott Manning. 2016. “Collectors and Museums. From Cabinets of Curiosities to Indigenous Cultural Centers.” In The Oxford Handbook of American Indian History, edited by Frederick E. Hoxie, 475–495. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Watterson, Alice, John Anderson, and Tom Paxton. 2019. Nunalleq: Stories from the Village of Our Ancestors. Accessed October 28, 2021. http://www.seriousanimation.com/nunalleq/.

- Watterson, Alice, and Charlotta Hillerdal. 2020. “Nunalleq, Stories from the Village of our Ancestors: Co-Designing a Multi-vocal Educational Resource Based on an Archaeological Excavation.” Archaeologies 16 (2): 198–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-020-09399-3.