ABSTRACT

This article considers the centrality of smells, both fragrant and fetid, to food practices at the Mughal court. Mughal-era manuscripts and paintings frequently reference the smells of spices, fruits, and flowers in the context of food preparation as well as consumption. They describe, too, the widespread use of aromatics derived from animals, especially ambergris and musk. The article explores how incorporation of these odoriferous substances in food dishes and dining spaces was envisaged as an ethical endeavor for fashioning of the Mughal elite as civilized, healthy, and spiritually refined gentlemen.

In Pursuit of Smells

Smell features as an important sensorial register in descriptions of meals consumed by the courtly elites of the Mughal empire that spanned present day India and Pakistan (Hindustan) from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. The textual and visual records of the period invite us to vicariously whiff the scents which enveloped Mughal elites as they ambled through rose-water sprinkled courtyards and sat around flowerbeds or water-tanks infused with saffron to consume bread loaves kneaded with fennel seeds, spiced rice, sweetmeats and comfits, beverages perfumed with rose water, and betel rolls packed with ambergris and musk.Footnote1 Lending an alert nose to these smells, the article will examine Mughal elites’ food (including beverage) consumption habits as an olfactory practice. In doing so, I recognize the concerns raised by the global community of food historians about the need to move beyond taste as the sole paradigm of sensory engagement.Footnote2

My decision to adopt an olfactory approach is a considered choice buttressed by evidence such as the following biographical sketch of a seventeenth-century Mughal noble, Jafar Khan. Upon eating a sweet-tasting melon given to him, Khan observed that it possessed an unpleasant fish-like smell. An enquiry into the matter revealed that the melon was grown in fields where bits of fish were mixed with the soil as manure. Subsequently, Khan was commended for “exquisite powers of smell and palate,” “rightmindedness,” and “excellent etiquette.” Footnote3 Khan’s dislike for the smell of fish was not an unusual or individual preference. Mughal cookbooks, repositories of the elite gastronomic expectations, provide recipes for removing foul smells from fish and aquatic fowls by cleaning, marinating, and preparing them with aromatics.Footnote4

A few key observations can be gleaned from these details. Firstly, the Mughal elite engaged critically with the sensory dimensions of food they consumed, and this skill was posited as the signifier of intellect and refined comportment. Furthermore, the prowess of discernment was not limited to the sense of taste but also involved being sensitive and attentive to the smell of food. Thus, a wholesome gastronomic experience was defined as much by the smell of food as its taste. Concomitantly, the article will argue that the act of food consumption was also the act of stimulating the nose for the Mughal elites invested in fashioning themselves as intelligent and genteel men. These attributes, as the article will elaborate, signified the virtue of civility or gentlemanliness and it involved cultivating a healthy mind and body to embody an ethical and spiritually refined self.

Locating smell-based food consumption practices as essential ingredients of this self-fashioning project, the article contributes to South Asian as well as global early modern food history. The existing scholarship on early modern South Asian does not offer nuanced reflections on the theme of food consumption.Footnote5 The earliest comments on the topic came from the pen of nineteenth-century colonial scholars who used descriptions like the ones cited above to furnish Orientalist cliches about abject moral corruption, hollow pageantry, and decadence of the Mughal court and the lives of its elite.Footnote6 Historians of Mughal South Asia offered resistance to these allegations by focusing on “more rational” issues pertaining to food like the questions of agrarian production, the adjunct revenue structures, and economies created by maritime spice trade networks.Footnote7 The reductive nature of this response to the accusations of Oriental superfluousness is particularly jarring because the Mughals recorded their acts of consumption in as many intricate details as the agricultural and trade processes that brought viands to their tables. Contrary to the reluctance of Mughal specialists, scholars of modern South Asia have trained the lens of food and embodiment to contextualize the issues of class, gender, and national identity formation during the colonial period.Footnote8 The present article bridges the gap to early modern South Asian historiography by focusing on the smells that informed food consumption habits to delineate the mentality, self-fashioning concerns, and the material-ephemeral world of the Mughal elite.

In the early modern global context, the Hindustani Mughal empire along with the Iranian Safavid and the Eurasian Ottoman empires constituted the Islamicate ecumene that spread from the Balkans in the west to Bay of Bengal in the east. These geographically diverse regions were welded together by their Central Asian lineage, use of Persian as the primary language of knowledge production, and constant movement of people, texts, ideas, and commodities via overland and Indian Ocean maritime routes.Footnote9 Drawing on this framework, Safavid and Ottoman scholars have enriched our understanding of how elites within these three empires inhabited a shared gastronomic zone, which was fostered by the circulation of ingredients as well as recipes rooted in Arabic, Iranian, and Central Asia food traditions.Footnote10 This formulation can be expanded to include the existence of analogous self-fashioning and sensorial concerns among the elites in early modern Islamicate societies. Though the present article focuses on the Mughal elite, it draws on literature and bio-ethical discourse that underpinned the intellectual landscape across these empires. In doing so, and aligning with the connected histories approach employed by scholars to study these empires, the article offers a template for understanding why the elites in the other regions of the Islamicate ecumene too would have focused on or employed similar smells in relation to their food consumption practices.

To examine the olfactory stimuli that pervaded food practices of the Mughal elite, the article will bring an insistent focus on the following questions: How was the notion of smell conceptualized and executed in relation to food consumption practices? Which olfactory substances and choices informed the etiquette of food consumption? Addressing them, the article is divided into two main sections that are centered on theory-prescriptions and praxis, respectively.

The first section will analyze the significance of olfactory dimensions of food consumption practices to the Mughal concept of civility. Here we will delve into the discourses on ethics, medicine, and religion that undergirded the lives of the Mughal elites. The second section will examine the ways in which expositions espoused by these knowledge systems translated into food habits and related material objects. This theme will be nuanced further by examining the role of the Islamic concept of correspondence between olfactory and ocular faculties in shaping Mughal elites’ ephemeral-material food culture. In doing so, the article will establish how every aspect of food consumption practice – ranging from meal settings to consumable and vessels – was informed by smell and its effect on the consumer’s body and mind.

Comprehensive engagement with these themes requires us to suspend modern as well as contemporary Anglophone sensibilities and lean into the early modern Islamic scientific and artistic conventions embedded in the Mughal autobiographies, biographies, advice treatises, manuals (domestic, lifestyle and culinary), poetry, paintings, and material objects. Building a dialog between these textual and visual materials, the article will advance an analytical narrative about Mughal food consumption as an olfactory practice that was primed by the demands of self-refinement.

Sense and Sensibility

The elite section of Mughal courtly society comprised the emperor and other male members who were enrolled in imperial service with a numeric rank (mansab) of 1000 and above.Footnote11 In addition to this bureaucratic standing, the Mughal elite claimed cultural superiority on the basis of their identity as civilized gentlemen. This notion of civility was informed by an exclusively elite male-centric discourse of Akhlāq (science of soul and ethics) that excluded women and non-elite men from the program of self-refinement. It was rooted in the thirteenth-century Iranian philosopher Nasir ul-Din Tusi’s Akhāq-i Nāsiri and drew on the principles of contemporary medical science (Yūnānī tibb) that envisaged the human body as a humoral entity that could be subjected to techniques of refinement. Tusi’s text was an integral part of the elites’ educational curriculum, and it inspired an entire gamut of ethical literature and codes of conduct treatises that was produced at the Mughal court.Footnote12 We will now consider one such text, the seventeenth-century Mirzānāma by an anonymous author.

Describing the rules of comportment (ādāb) for Mughal elites, the Mirzānāma lists partaking of fragrant foods and curating perfumed dining spaces as essential features of gentlemanliness (mizāī).Footnote13 This training manual was written to distinguish courtly elite from merchants and other nouveau riche but lower-status men who aspired to lead a luxurious life. Though the latter categories owned resources, they were scorned for lacking a decent pedigree, a position at the court, and the concomitant behavioral finesse. Practices of food consumption and the smells associated with it were posited as signifiers of difference between the elite and non-elite. Thus, unlike the “rabble of the market-place,” that is, men of lower status who drank and ate excessively, preservation of Mughal elites’ dignity demanded the avoidance of gluttony because it led to belching, the odor of which was considered “worse and more unpleasant to the mind than the smell of gunpowder.”Footnote14 Mughal elite were also exhorted against consuming radish and turnips on the same grounds.Footnote15 Instead, civilized gentleman were advised to consume fragrant food and drinks like rice boiled with spices, harīsa (wheat porridge) with cinnamon and herbs, āshjaw (broth of barley) compounded with lemon juice, sugar, herbs, and rose-water, sarpācha (boiled jaw and foot-joint of meat) sprinkled with vinegar, lemon juice and mint, perfumed fāluda (chilled vermicelli), halwā (sweetmeat) made with nuts, amber tablets, pieces of lemon, and sandalwood perfume, rishta (pasta-like dish) fragranced with amber, bīd- mushk (musky willow flower) scented drinking water, and perfumed wine.Footnote16 Commenting on the manner in which was a mirzā expected to host food gatherings, the text recorded:

He should always provide perfumes [ʿaṭrīyāt] in his parties; and try to keep his parties fragrant with them. All sorts of vases full of flowers in every season should be on view. Without them he should consider the luxury of living as forbidden. He should keep his feasts colourful; so that whoever departs from it may feel that he has been to the feast of a mirzā; that is to say, he should depart bearing the fragrant smell of scent and flower.Footnote17

In laying out these prescriptions, which highlight smell as an important aspect of food consumption syntax, the author claims to be an expert who knows and understands ‘ilm, a term used to signify knowledge and science in Islamicate societies.Footnote18 The author exhorted that the act of meaningfully embedding one’s self in the world of fragrant food practices demanded commitment to the ‘ilm of ethics (Akhlāq) and etiquette (ādāb).Footnote19

The Akhlāqī discourse advocated cultivation of a balanced soul (nafs) or inner-self, which used the physical body an active receptacle for its manifestation, and emphasized the outward display of this virtuous self through acts of comportment. According to Tusi, this state of internal balance could be fashioned by establishing the command of intellect over the uninhibited carnal and appetitive drives such as anger, greed, desire, and hunger. Achievement of this disciplined or moderate self was considered important for successful governance of the empire and dispensation of domestic duties. It was also seen as the conduit for experiencing absolute happiness, active pleasure, and spiritual awakening.Footnote20 Subservience to intellect was posited as a particularly difficult task for women as their procreative functions were believed to incline them more toward carnal desires.Footnote21 Consequently, the Akhlāqī model of ethical self-fashioning projects decadence as a feminine trait and pleasure activated by intellect as a masculine attribute. The author of the Mirzānāma reproduces and reinforces this idea by assigning a masculine identity to mizā’ī. He states that to be a mirzā was to be mirzā-Beg and mirzā Khān (male elite) and not mirzāda-Begum or Khānum (female elite).Footnote22 As a result, the prescriptions about food consumption recorded in the text were aimed at ethical and spiritual advancement that was not universal in nature. Rather, it was specific to the construction of elite masculinity.

The Akhlāqī emphasis on the mastery of intellect implied acquiring knowledge about the physical body and learning the techniques to refining it. In this regard, Akhlāq, the‘ilm of soul, was to be complimented with Yūnānī tibb (Graeco-Arab medical system), the‘ilm of human body.Footnote23 Yūnānī, practiced across the Islamic ecumene and a living tradition even in the present times, conceives the human body as made of four temperament-dictating humors that were identified with four natural elements and a pair of contrary properties. In short, it presents the following scheme:

While equilibrium between the four humors implied a healthy temperamental state, excess of any humor was perceived to cause an imbalanced or diseased temperament. Excessive amounts of yellow bile and humoral blood resulted in bilious and sanguine temperaments, respectively, that excited carnal emotions and appetitive powers by releasing more than necessary heat in the body. Similarly, predominance of black bile and phlegm stimulated unwarranted coldness, rendering the temperament passive and inducing sadness and lethargy in a person.Footnote24

The smell of food and the spaces in which it was consumed were envisaged as possessing the power to shape an individual’s temperamental and ethical health. Yūnānī linked the formation of temperament to the digestion of food – proper digestion of food was believed to ensure balanced humoral formation and poor digestion resulted in humoral imbalances.Footnote25 The functioning of the gut was in turn dictated by the odor of food. Elaborating on this, Galen remarked that “food must not have hateful smell, digestion of [which is] harmful for the stomach, fumigating into the head and detrimental for the brains.”Footnote26 Thus, bad smelling food hindered the process of digestion and simultaneously impeded the ability of the brain, the facilitator of intellect, to perform at its optimal capacity. In addition to ingestion of smell via food, the smell inhaled from the surroundings was also believed to affect the body and the mind. Here it must be pointed out that smell can be defined as a qualitative attribute of air. Depending upon the type of odoriferous substance air comes in contact with, it either emanates fragrance or fetor. This association is signified by the Persian term dam, that implies air and smell as well as breath.Footnote27 According to Yūnānī physicians, Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Jalius (Galen), inhaled air impressed on the faculty of smell (quwāt-i shāma) located in the front part of the brain and affected the ability of the heart to pump humors to the rest of the body.Footnote28

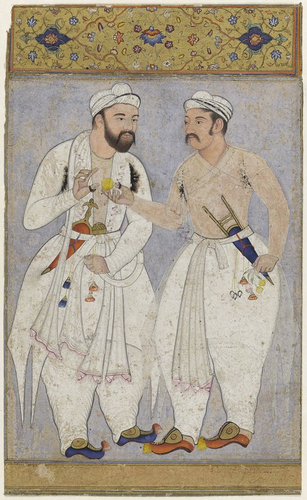

Drawing on personal observation, the fourth Mughal Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–27) noted in his autobiography that people who inhaled bad air (badbū) were extremely weak-hearted, feeble-minded, and suffered from illness.Footnote29 Contrary to this, fragrance was perceived to be a fortifying entity. Using the example of lemon, the eleventh-century Arab physician, Ibn al-Baitar, waxed eloquent about the ability of fragrance to purify polluted or pestilential air. The celebrated twelfth-century Persian poet, Nizami, embellished this medical-olfactory prescription and credited the scent of lemons with “removing the torture from the friend’s brain.”Footnote30 Nizami’s words seem to have found visual expression in a Mughal miniature that portrays an exchange of lemon, presumably for the purpose of consumption, between two Mughal elite men (see ). In fact, the substances from which fragrances emerged were categorized under the umbrella of cephalic and cardiac drugs (adwiya-i mufarrih, literally exhilarating and refreshing drugs) in Yūnānī pharmacopoeias.Footnote31 In addition to lemon and other citrus fruits like citron and orange, these included: apple, quince, pear, melon, pomegranates, mangoes, pineapple, cardamon, saffron, black pepper, cinnamon, cloves, ginger, coriander, mastic, sandalwood, aloeswood, camphor, rose, narcissus, violet, hyacinth, jasmine, lily, water lily, basil, musk, and ambergris.Footnote32

Figure 1. Unknown, Two men with archer’s rings on thumbs, dressed in white muslin clothes, one giving the other a lemon, circa 1560–1580, the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

The above-outlined details exemplify why the Mirzānāma advised the Mughal elite to fashion themselves as civilized gentlemen by staying clear of fetid and embracing fragrant food consumption practices. Eating fetid food in foul smelling dining spaces was inimical to the physiological and psychological processes considered essential to the Akhlāqī and Yūnānī conceptions of ethical, spiritual, and temperamental refinement of the self. In other words, the potential of the brain to muster intelligence, the ability of the stomach to produce humors in a balanced quantity, and the strength of the heart to circulate these humors were obstructed by food and meal settings that bore an unpleasant smell. Partaking of fragrant (khushbū) food in perfumed surroundings, on the other hand, invigorated the heart and the brain, bestowed the body with temperamental equilibrium, and thereby contributed to the idealized state of ethical perfection and spiritual awakening.

The significance of consuming fragrant food in perfumed surroundings as a conduit for civility is reinforced by the Sufi ideas that undergirded Mughal political and religious thought. In a debate at Akbar’s court over the question of Islamic religious sanction on the consumption of saffron, Abul Fazl, Akbar’s ideologue and the author of his biographical account, weighed in with the following response:

It [religious sanction] depends on temperament. As it is, there is a Prophet’s saying, “Accept that which is limpid and leave that which is turbid;” it should be acted upon; in other words, whatever is good and the temperament accepts, one should act on it and whatever is not agreeable to temperament, one should avoid it.Footnote33

Fazl’s explanation, highlighting entanglement between the Islamic Prophetic tradition and medical concept of temperament, draws from the twelfth-century Sufi philosopher Ibn ‘Arabi’s text, Fusūs al-Hikam.Footnote34 The Fusūs situates the existence and use of fragrant ingredients as an expression and fulfillment of the divine will. It explains the Quranic tradition about the Prophet Muhammad’s fondness for fragrances as the reflection of his moral beauty, which emanated from perfect temperamental constitution that corresponded to the divine will in the most precise way possible for a human being.Footnote35 This exposition lends itself to a more generalized understanding about temperament as the guiding force behind an individual’s preference for pleasant or unpleasant olfactory stimulus. ‘Arabi envisioned the acts of delighting in fragrant substances, such as their inclusion in foods and dining spaces, as a tangible expression of the inner-state of temperamental balance and moral beauty (al-husn). He also asserted that speech, an outward manifestation of breath or the inhaled air, was attributed with odoriferous qualities. Those with proclivity for consuming fragrant substances were perceived as possessing a beautiful fragrant speech and the ones who did not ingest and inhale good smells were condemned to spout less comely or foul speech.Footnote36 ‘Arabi’s commentary about the use of fragrant substances as a medium for displaying or “speaking” about one’s temperamental, moral, and spiritual refinement runs parallel to Akhlāqī emphasis on exhibiting the civilized self through appropriate comportment.Footnote37

This imbrication between Sufi, Akhlāqī, and Yūnānī discourses is further underlined by inclusion of Fusūs in the‛Ilājāt-i Dārā Shikūhī’, a weighty, four-volume medical compendium composed by the seventeenth-century Mughal physician, Nur al-Din Shirazi. The text contains theoretical expositions about the body and the mind and practical knowledge about recipes, including methods for preparing perfumes and fragrant food. The discussion on sense organs elaborated in the ‛Ilājāt is particularly illuminating in the context of this article. It notes how all sense organs functioned as gatherers of information from the outside world but lacked the ability to differentiate between good and bad sensations. But even as the text suggests these similarities, it organizes external sense organs in a hierarchical order in which the nose is accorded the last position. Ironically, the reason for the nose’s inferior position derived from its importance as the channel for breath or life force. This anatomical function makes the nose more vulnerable to unpleasant stimuli because, unlike the other sense organs, it cannot be coerced into shutting down for extended periods of time.Footnote38 As a result, learning about odoriferous substances so as to surround the nose with fragrant smells and protect it from foul odor was integral to the Mughal conception of civility.

The significance of the intellectual prowess in navigating the world of smells is succinctly captured by the Persian term dimāgh, which primarily means the brain but is also used to signify the nose.Footnote39 Prescriptive treatises, like the Mirzānāma and medical manuals, were penned to educate the courtly elite about odoriferous substances. These medical manuals commissioned, and in circulation, at the Mughal court included Shirazi’s seventeenth-century book on materia medica titled the Alfāz u Adwiya; the tenth-century Arab physician Al-Samarqandi’s texts that formed the basis of a 1700 CE Mughal medical treatise called the Tibb-i Akbari; the seventeenth-century Mughal domestic manual, Bayaz-i Khushbu’i (literally sweet-smelling notebook); and Fawaʾid al-Insan, a sixteenth-century Mughal pharmacopoeia.

Sheared of dense theory and rendered in simple language, these texts provide lists of fragrant consumables and state their properties and effects on the human body. They employ odor intensity as the criteria for categorizing substances into primary (musk, ambergris, aloeswood, camphor, and saffron) and secondary aromatics (clove, pepper, cinnamon, mace, nutmeg, fennel, cardamom, mastic, sandal, lotus and rose).Footnote40 Fragrant ingredients were also classified on the basis of their inherent hot, cold, and temperate qualities with rose, narcissus, and more generally all floral smells being identified as temperate; musk, ambergris, saffron, black pepper, ginger, citron, and watermelon as hot; and camphor and sandalwood as cold.Footnote41 Knowledge of these qualities was important as they could be harnessed according to the principle of contraries to fix temperamental imbalance. In other words, warm aromatic substances were used to counteract disorders caused by an excess of cold humors in the body and vice-versa. However, the Yūnānī tradition vehemently promotes prevention over cure.Footnote42 The emphasis on maintaining a disease-free, healthy body as a canvas for experiencing ethical pleasure and spiritual awakening resulted in the promulgation of a Mughal food consumption regime, which lavished attention on the use of fragrant substances and was implemented on a daily basis.

Ephemeral World of the Mughal Gentlemen

Now I will delineate how the Mughal elite executed this prescriptive and theoretical knowledge about the impact of odoriferous substances to curate their meals. We will enter their dining spaces and experience the food dishes, mouth-fresheners, wine, and tobacco they partook. The function of aromatics in negotiating with proscribed practices of wine and tobacco consumption will be explored. Attention will also be drawn to the role of fragrance in dictating the visual imagery that accompanied the elites’ consumption practices.

Let us embark on this journey by attending to the spatial arrangements of elite convivial gatherings. In the case of outdoor gatherings, gardens redolent with flowering plants and fruit bearing trees were the most favored venues. The autobiography of the first Mughal emperor, Babur, records many instances in which he and his retinue of men halted at various gardens for the purpose of refreshments. Particularly striking among these was Babur’s Bāgh-i Wafā or the Garden of Fidelity in Kabul, which boasted of fragrant pomegranate and orange trees, and a constantly running stream of water from the nearby mountains and a ten-by-ten meter pool.Footnote43 As stagnant water could have caused stench, waterwheels were constantly operated to funnel fresh groundwater into the pools situated within the Mughal gardens.Footnote44 Similarly, his grandson Emperor Jahangir organized a wine gathering in saffron fields such that the breeze perfumed the nostrils of the imbibers.Footnote45 Bhimsen Saxena, a seventeenth-century Mughal administrator and poet, describes a meal setting in a garden with ambergris-scented earth (alluding to the practice of mixing manure with aromatics) accessorized with carpets, grape vines, cypress trees and flowing water.Footnote46 Even the indoor meal settings were infused with perfumes, which were used according to their inherent qualities and the principle of contraries. For instance, lakhlakha, a warming perfumed-ball composed of aloeswood, musk, and camphor was burnt in an iron censer during winter and monsoon seasons; rose along with argaja, a cooling perfume, was considered perfect banquets hosted at inside the mansions of the elite during the summer months.Footnote47

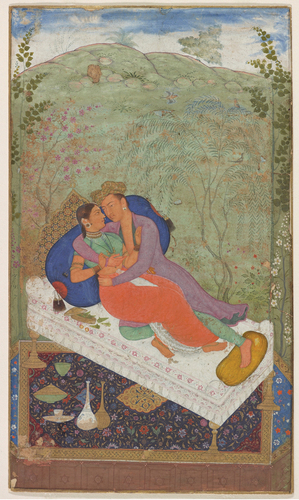

In terms of food commodities, fragrant masticatory betel (pan or tānbūl) rolls (bira), concocted by packing betel leaves with slaked lime, catechu essence and slices of areca nut, ambergris, musk, camphor, cinnamon, cloves, and oyster shells, were integral components of elites’ lives. Mughal manuals and pharmacopoeias specify the exact proportion in which the above-listed ingredients should be mixed to produce a perfectly balanced parcel of olfactory substances.Footnote48 Upon chewing, these betel rolls functioned as mouth fresheners (mukhavasa) that adorned the breath with a sweet fragrance and thereby provided gladness to the heart, reduced stress and strengthened intellect.Footnote49 Perfumed breath, as pointed in the previous sections, was considered an outward exhibition of a person’s inner refinement and was believed to layer their spoken words with moral beauty. For these reasons, sweet-scented betel rolls were used in multiple contexts. These green-colored parcels were consumed at the beginning or during the course of amatory liaisons to invigorate the heart (see ). Music performers partook betel rolls during recitals to channel their properties of reducing stress and lacing the voice with sweetness (see ). Betel rolls were also chewed after meals to alleviate halitosis and were gifted to signal the end of social gatherings on a veritably sweet or happy note.Footnote50 Commenting on the latter, Peter Mundy, an Englishman who visited the Mughal court wrote in 1632:

Figure 3. Unknown, Lovers on a terrace with three musicians, circa 1700, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

There is noe vesitt, banquett, etts. Without it, with which they passe away the tyme, as with Tobaccoe in England; but this is very wholesome, sweet in smell, and stronge in taste. To strangers, it is most commonly given att partinge, soe that when they send for Paane (betel rolls), it is a sign of dispeedinge, or that it is time to be gon.Footnote51

Mundy’s account also highlights that olfactory and papillary profiles of a consumable were not always mutually exclusive. For example, the sweet-smelling pan did not possess a sweet but a sharp taste. While some food products were believed to naturally combine sweet smell and taste, in other cases, irrespective of the taste profile, conscious efforts were made to infuse dishes with sweet aromas. The significance of this can be gauged from the definition of sweet smell as a temperate and well-balanced profile with digestive properties.Footnote52 Illustrating the former, mangoes, melons, and pineapples, listed as most suitable fruits for a gentleman, were praised for bearing qualities of sweet smell and taste.Footnote53 From among these, pineapples were only introduced in the Mughal territories during the late-sixteenth century by the Portuguese traders. For the Mughals, the smell of this unfamiliar transatlantic fruit was similar to that of mangoes, a typically south Asian fruit celebrated for its unrivaled sweet-smell that was believed to increase manifold if the fruit got injured while on the tree.Footnote54 Mughal gentleman were advised to consume mango preserve with fresh herb juice and pineapple relish mixed with sugar and rose water.Footnote55 These fruits along with melon were also added to savory dishes such as qalya (gravy based meat and vegetable dish) and pūlāv (a rice dish; sometimes anglicized as pilaf).Footnote56 The smell of cooked food was also enhanced by the addition of other sweet-scented ingredients like chalta (flower of elephant apple), hamesha bahār, pādal, binafsha (violet), and gul-i Multānī (a flower from the region of Multan).Footnote57

Humorally cold and hot properties bearing fragrant substances such as saffron, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, areca nut, coriander, ginger, oranges, and lemons, among others, also informed the olfactory profile of dishes.Footnote58 However, overuse of these as well as the other aromatics could lead to loss of moisture from food, making it difficult to digest.Footnote59 Improper digestion in turn impeded the project of ethical and spiritual self-fashioning by causing temperamental imbalance. To retain the virtue of aromatics in bolstering the process of the self-refinement, they were added to food dishes in specific proportions. This complicated craft was executed by skilled cooks employed in the kitchens of the elites. They worked under the watchful eyes of kitchen superintendents, who were physicians by training and helmed the production of food recipe manuals that mentioned exact quantities and combinations of fragrant substances to be used in each food preparation.Footnote60 This supervision and standardization, ensuring mindful use of spices and aromatics, rendered a humorally balanced smell profile to each dish. Similarly, the beverages department in the elite households was managed by a supervisor who ensured addition of appropriate quantities of fragrant substances in various drinks, including wine.Footnote61

The practice of drinking perfumed wine highlights the manner in which intoxication was understood and navigated within the constraints presented by the Islamic religious and legal framework. Contrary to the commonly held belief, Islam does not unequivocally condemn the consumption of wine. The Quran, even as it spells the pitfalls of wine over-consumption, includes rivers of wine and intoxicants obtained from the fruits of palms and grapes as the promised pleasures of paradise. They are hailed as good nourishment and one of God’s special signs to the community of true believers.Footnote62 Sufi discourses extoll wine as a conduit for experiencing true knowledge of the divine and the spiritual realm that exists outside the dimension of normal consciousness.Footnote63 In the context of Islamic law, the Sunni Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence followed by the Mughals advanced a stance that distinguished between drinking wine and being drunk on wine. Not the intoxicant itself in but intoxication resulting from over-indulgence, which manifested itself in the form of odor on the consumer’s breath was forbidden.Footnote64 Here, the smell of the breath is posited as the distinguishing factor between an inebriated and sober state. This presents a corollary to the previously detailed argument about the smell of breath as the conduit for gauging one’s moral constitution. Therefore, the practice of camouflaging the undesirable smell of wine through addition of aromatics was adopted by imbibers to perform sobriety as well as civility.

Among the aromatics, rose and musk feature regularly as additions to wine in autobiographical records, medical manuals, and recipe books.Footnote65 These choices are particularly instructive as the fragrances of rose and musk were and are considered conduits to the divine within the Islamic religious tradition.Footnote66 The Mirzānāma likens rosewater to the Prophet Muhammad’s sweat and, in doing so, evokes the Islamic belief that rose was created from the drops of perspiration that fell from the Prophet’s forehead during his miraculous nocturnal ascent through the seven heavens to the throne of God.Footnote67 Encapsulating within its essence the Prophet’s transcendental beauty, the rose is credited with the power to soothe one’s spiritual needs through its long-lasting fragrance that continues to endure despite the process of organic decay.Footnote68 Musk on the other hand, as Anya King has pointed out, was the chosen aromatic of the Prophet. It finds mention in Quranic verses and commentaries that speak about it as an additional component or aroma of the wine promised in heaven.Footnote69 Evoking the Quranic association between musk and wine, Emperor Jahangir waxed eloquent about the aromatic vapors of the exhilarating wine banquet that turned “the celestial sphere into a musk bag.”Footnote70 Thus, consuming musk-scented paradisiacal wine and wine mixed with the Prophet’s proverbial sweat would have heightened the Mughal elites’ experience of spiritual awakening.

Wine on the breath was not the only objectionable odor; the Mirzānāma also condemns the practice of smoking tobacco. This “new world” transatlantic commodity, introduced in the late sixteenth century to Mughal territory by the Portuguese, was deplored on the grounds that its use imparted undesirable stench to the breath of the consumer.Footnote71 As in the case of injunctions against the smell of wine, the Mughal elite innovated a way to negotiate tobacco’s unpleasant odor. Mughal paintings of the elites smoking hookah (a single or multi-stemmed instrument for heating or vaporizing and then smoking tobacco) often depict them smelling fragrant flowers – particularly rose and narcissus – that surely perfumed the air of their immediate surroundings as well as their breath.Footnote72

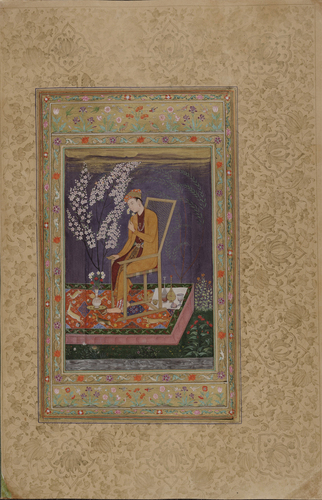

It is worth noting that the narcissus flower occupied as prominent a niche as rose in the Mughal olfactory-food consumption grammar. A metonym for eyes in the classical Arabic and Persian literary traditions, the narcissus flower is presented as the first competitor among fragrant flowers in the late fifteenth-century Persian poem, Ramz al-Rayāhin (Secret of Fragrant Plants).Footnote73 In this munāzara or debate poem genre, which drew on the prevailing botanical practices to convey opinions about mundane and spiritual issues, the narcissus is a worthy rival of the rose. As the rose casts aspersions on the comparatively less potent smell of the narcissus to boast about its own ability to saturate the wine with fragrance, the narcissus reminds the audience of the illicit role played by the rose in enabling excessive drinking and projects itself as the eyes that keep watch on the acts of intoxication in convivial gatherings.Footnote74 The essence of this poetic claim about the role of narcissus as the guardian of morally driven consumption etiquette is captured in a seventeenth-century painting (see ) from the reign of the fifth Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. It depicts a seated young Mughal prince, who is decidedly looking away from wine flasks and cups and is gazing at a vase filled with narcissus whilst sniffing a taffeta of narcissus.

Figure 4. Unknown, a prince with a narcissus, circa 1600–1699, Bodleian Libraries MS. Douce Or.A.1, folio 45b., University of Oxford.

As for the potency of the narcissus’s fragrance, Nizami noted that it was powerful enough to rob the extraordinarily perfumed oranges of their “good fortune” or fragrant scent.Footnote75 The smell of narcissus was also believed to change the orange’s acidic taste to sweetness. For this reason, the practice of planting narcissus under orange trees is favored in the ‘Ajā’ib al-Makhlūqāt (Wonders of creation) by Zakariyya ibn Muhammad al-Qazwini, which was first written in thirteenth-century Iraq and continued to be reproduced throughout the early modern Islamic ecumene.Footnote76 The complementary relationship between the narcissus and orange can be seen at play in an eighteenth-century Mughal painting held in a private collection and reproduced in the Foger and Lynch exhibition catalog. It depicts a pile of oranges propped over mangoes, nudging them closer to a thick bunch of narcissus flowers overflowing from a vase.Footnote77 In a similar vein, another eighteenth-century miniature at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, shows a noble and a woman sitting in a garden pavilion that is lined with orange trees with a vase full of narcissus flowers and a pile of betel rolls placed between them. The nobleman is also holding a bunch of narcissus in one hand and a smoking pipe in the other.Footnote78 These details highlight how the elites understood and channelized the transformative power of fragrance to convert their consumption habits into a source of self-refinement.

Visual representations of the narcissus were not limited to paintings. This fragrant flower found its way into the culinary realm in the form of a recipe format called the nargisī. A tenth-century versified Arab culinary text explains the process for preparing a nargisī dish as follows: “Then break an egg on it, like eyes; Like shining stars of the firmament; Or round narcissus flowers.”Footnote79 The Mughal culinary manuals record recipes for preparing dishes such pulāv, du piyāza (viscous gravy based savory preparation), qalya (gravy based savory preparation), and shashranga (medley of vegetables) in this manner.Footnote80 These recipes involved mimicking the narcissus flower on top of food dishes by adding eggs to them in such a manner that the yolk and white did not mix. Consequently, the cooked eggs looked like the narcissus flower: yellow yolk center surrounded by the egg white. Recreating the fragrant narcissus, which was also popularly recognized as the motif for the eye, the nargisī dishes, I contend, aimed to engage the sense of smell through the sense of sight. These dishes also allude to the idea that sensory engagement with food was not restricted to the sense of taste or sensations on the tongue. Rather, the experience of food consumption involved participation of multiple senses, like the olfactory and ocular in the present case.

To contextualize these arguments, let us turn our attention to the Islamic model of intersensory perception and synaesthetic idea of “seeing” smell. Complex interplay between olfactory and ocular modalities features in the Quranic story about the blind Yaqub (Jacob) regaining eyesight on smelling his son, Yusuf’s (Joseph) sweat-drenched shirt. Rumi, the famous thirteenth-century Sufi poet, built on this Quranic cross-modal tradition. Drawing attention to the Persian term bīnī that signifies both seeing and nose, he advised the readers to reflect on the fragrance of his poetic words.Footnote81 In doing so, he situated the eyes as the preceptor for the nose and likened the ability to “see” fragrance with an experience of spiritual rapture. The act of “seeing” smell is comparable to the experience of spiritual enlightenment because the divine and the fragrant odor, on account of their inherently invisible nature, cannot be witnessed by the naked eye. The visual-olfactory clues embedded in the nargisī format can be situated within this tradition of “seeing” the invisible smell. The puzzle presented by nargisī dishes would have been legible to the Mughal elite, who were expected to be acquainted with these sacral and poetic traditions and were invested in fashioning themselves as spiritually refined gentlemen. The sight of nargisī food dishes must have encouraged them to think about and recall the smell of narcissus, or fragrant odors more generally, while consuming their meal. Concomitantly, food consumption activities can be envisaged as cognitive exercises that demanded the Mughal elite to be alert and perceptive to multiple sensory stimuli. This coincides with the emphasis placed on boosting the mental faculty, the gatherer of sensory information and the facilitator of intellect, in the Akhlāqī and Yūnānī program of self-refinement.

This framework of multi-and-intersensory perception, whereby the smell of an odoriferous substance could be imagined and experienced by looking at its visual rendition, also provides a departure point for analyzing consumption-related material objects. Inlaid and carved representations of aromatic substances recur as a prominent design feature on the trays, flasks, cups, plates, bowls, and even spoons used by the Mughal elite for food consumption. Likewise, the mango-shaped beverage flask (see ), the ruby-studded and rose-resembling rosewater sprinkler and many other similarly rendered vessels are explicit visual renditions of fragrant substances.Footnote82 Mineral substances such as jade, rubies and pearls used to craft these vessels were believed to possess stomach strengthening and cephalic properties akin to the powers yielded by fragrant substances.Footnote83 These design and material decisions, I argue, were considered choices aimed at invoking the smell of fragrant substances as well as replicating their effect on the body. Thus, every aspect of the Mughal consumption experience – from the meal setting, to the food and the utensils in which it was consumed – was doused in fragrances.

Conclusion

Let us compare the narrative presented in this article with a scene from a recent Indian Hindi-language period film that shows an early modern Islamic elite male seated in a dirty-dingy tent and devouring a big slab of undressed meat. This almost animalistic depiction reflects lack of research and aligns with tropes furnished by the colonial writers. According to them, the Mughal court society was “sunk in sloth” and plagued by elites who seemed to “sympathize with no virtue, and to abhor no vice.”Footnote84 The courtly elite were accused of not being productive by indulging in decadent grand gestures that lacked sophistication and philosophical mooring. The analysis offered in this article shatters these unpalatable orientalist cliches and their persistence in the contemporary portrayals of early modern courtly lifestyle. The latter is equally enabled by the current Indian political dispensation’s communal rhetoric about the erosion of South Asia’s sanitized “Hindu culture” due to the establishment of the decadent Islamic Mughal empire. The penchant of the Mughal elite for using expensive fragrant ingredients in their meals and meal settings undeniably symbolizes grandeur. But this life of ostentation, as I delineate throughout the article, was dictated by the demands of embodying civilized elite masculinity. This implied cultivating a refined self that could successfully perform imperial duties, revel in ethical pleasure, and experience spiritual awakening. Fashioning of this virtuous self was nurtured by intersecting discourses on ethics, medicine and religion that hailed the powers of odoriferous substances to transform the consumer’s soul by affecting their body and mind. Odors rising from fragrant substances were categorized as exhilarating cephalic and cardiac drugs as they were believed to activate the brain, fortify the heart, and render a balanced temperament. The transformative powers of fragrant ingredients were also conceived of as layering a person’s speech with moral qualities. On the other hand, smells from odoriferous substances that impacted these functions negatively were consigned to the category fetor. Given this totalizing impact of fragrant ingredients on a person’s being, the world of civilized Mughal gentlemen – wrapped in the sweet-smelling betel rolls, cinnamon, cardamom and pepper spiced dishes, beverages mixed with flower extracts, outdoor meal settings in gardens manured with ambergris and indoor dining spaces fumed with camphor – could not afford disturbances caused by foul odors such as belching compelled by acts of over-eating or by the consumption of radishes and turnips.

Different sections of the Mughal population could, and must have, adopted similar fragrant food practices, but the significance of these consumption habits was judged on the basis of the consumer’s political-social position and gender identity. It was believed that lower-status men, due to their indecent pedigree, and women, vested with procreative functions that weakened their ability to act in a balanced manner, lacked behavioral finesses and capacity to acquire knowledge that was needed to channelize the power of fragrant substances for curating a refined self. High-status men were singled out as the sole candidates for realizing the potential of fragrant ingredients to craft a wholesome ethical self, in pursuit of pleasure and spiritual enlightenment. Prescriptive codes of conduct treatises, pharmacopoeias, domestic manuals and cookbooks were authored to teach elite men about the properties of odoriferous commodities, methods for lacing food dishes and dining spaces with fragrances, and a proper regime for ingesting and inhaling them. As repositories of the Mughal olfactory catalog, these texts were constantly updated to include new commodities brought to the South Asian shores by the Portuguese merchant traders via transatlantic trade networks. Pineapples and tobacco feature as the chief “new world” products that attracted remarks by Mughal commentators, with the odor of the former earning the reputation of fragrance while the smell emitted by the latter was compared to the stench of gunpowder. Proscription of unpleasant smell begetting practices, like tobacco smoking and excessive wine-consumption, underline their widespread usage. Yet, their consumption did not translate into neglect of olfactory etiquette. To negotiate these undesirable smells, the Mughal elite adopted the practice of sitting in verdant garden pavilions and sniffing flowers while smoking tobacco and mixing wine with rose water and musk, the two aromatics that in the Islamic theology are associated with Prophet Muhammad.

Furthermore, the nose and the mouth were not the only orifices through which the Mughal elite were expected to consume fragrant substances. They were also expected to use their sense of sight to perceive smell. The ability to “see” invisible fragrant odors, equated with the ability to perceive the invisible divine, involved using mental faculty to recall and experience smell by looking at the odoriferous object and its visual representation. Based on the Islamic notion of correspondence between the olfactory, ocular, and mental faculties, this notion of seeing smell found culinary expression in the visual trick employed to recreate the narcissus flower garnish for food preparations. It also informed the practice of using gemstones, metals, and minerals, attributed with cephalic and cardiac properties similar to those yielded by fragrant substances, to reproduce floral and fruit motifs on vessels used for eating food and drinking beverages. In a nutshell, for the Mughal elite, food consumption was a complex cognitive exercise that relied on ingesting, inhaling, and envisioning fragrant smells to render a synesthetic sensory experience aimed at temporal and spiritual refinement.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Neha Vermani

Neha Vermani is a cultural historian of early modern South Asia invested in the themes of consumption practices, body, and affect. Her work explores histories of self-fashioning, senses, emotions, and related knowledge and material productions. Her research repertoire spans the history of Mughal and early colonial South Asian history from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, with an interest in Timurid Central Asia, and Safavid and Ottoman Empires.

Notes

1. For detailed descriptions of such events, see Fazl, Akbarnanama, 1:418–431; Bayat, Tanikh-i Humayun, 4–5; Bhakkar, Dhakhirat ul-Khawanin, 1:88–89; Nathan, Baharistan-i Ghaybi, 2:735–6.

2. Vabre, Bruegel, and Atkins, Food History; Korsmeyer and Sutton, “The Sensory Experience of Food,” 461–475.

3. Khan and Hayy, Maathir-ul-Umara, 1:723.

4. Anonymous, Risala-i Anwa‛-i Taʻam, f. 112.

5. In the recent years, smell as a category of historical analysis has assumed significance in early modern South Asian studies. Akbar Ali Hussain and Emma Flatt, working on Deccan Sultanates that rivaled the Mughal empire and reigned over South India from the late fifteenth to the seventeenth century, have examined the centrality of scents to garden culture, bodily adornment, and occult sciences. See Hussain, Scent in the Islamic Garden; Hussain, “Perfume and Pleasure,” 43–56; Flatt “Spices, Smells and Spells,” 3–21; Flatt, “Social Stimulants,” 24–41. Scholarship of Suzzanne Evans, Maria Subtelny, Christiane Gruber, Michael Pifer and Adam Bursi, spanning the Arabian Peninsula to Iran, Turkey and Armenia, highlight the ubiquitous presence and use of fragrances in Islamic religious practices from the eighth century onwards in their investigations of histories of martyrdom, mysticism, devotional art, and pilgrimage sites. See, Evans, “The Scent of a Martyr,” 193–211; Subtelny, “Visionary Rose,” 13–25; Gruber, “The Rose of the Prophet,” 224–249; Pifer, “The Rose of Muḥammad,” 285–320; Bursi, “Scents of Space,” 200–234; Anya King’s monograph extensively covers the origins, ceremonial, medicinal, and geography specific uses and trade of a singular aromatic substance – musk – in the medieval Islamic world. See King, Scent from the Garden.

6. For colonial narrative about the Mughal empire, see, H.M. Elliot’s original preface in Elliot, The History of India, 1:xv – xxvii.

7. Such works include Habib, The Agrarian System; Habib, “Potentialities of Capitalistic Development,” 32–78.

8. See Berger, “Between Digestion and Desire,” 1622–1643; Ray, Culinary Culture; Sengupta, “Nation on a Platter,” 81–98.

9. See Hogdson, The Expansion of Islam; Robinson, “Ottomans-Safavids-Mughals,” 151–184; Subrahmanyam, “Connected Histories,” 735–762.

10. Fragner, “From the Caucasus to the Roof of the World,” 50–60; Matthee, “Patterns of Food Consumption,” 3–5; Isin, Bountiful Empire, 11–17; Hoogervorst, “Qaliyya,” 106–127.

11. Ali, The Mughal Nobility, 2.

12. Alam, The Languages of Political Islam, 49–71; Kinra, Writing Self, Writing Empire, 61, 83.

13. Ahmad, “The British Museum Mirzanama,” 100.

14. Ibid., 101, 104.

15. Ibid., 104.

16. Ibid., 101, 103–104.

17. Ibid., 102.

18. Ibid., 103. For a discussion on ‘ilm as a concept that denotes both knowledge and science in Islamic societies and how this differs from the modern-day English language rendition of the terms of knowledge and science, see, Rosenthal, Knowledge Triumphant, 1–4, 40–45, 194–246, 340.

19. Ibid., 100.

20. Ibid., 28, 43, 47, 50–52, 56, 71–72.

21. O’Hanlon, “Manliness and Imperial Service,” 52–54.

22. Ahmad, “The British Museum Mirzanama,” 105.

23. Tusi, The Nasirean Ethics, 111–112.

24. Here, I have presented a condensed version of the basic concepts and principles of Unani medical system. See Israeli, “Humoral Theory of Unani Tibb,” 95–99; Rahman, “Unani Medicine in India,” 304–313; Pormann and Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine, 41–44.

25. Vermani, “From the courts to Kitchens,” 128–129.

26. Al-Israili, Kitab al-Aghdhiya, 162.

27. Steingass, A Comprehensive Persian-English Dictionary, 534.

28. Avicenna, Avicenna’s Psychology, 26–27. Jütte, “Sensory Perception,” 314; Hussain, Scent in the Islamic Garden, 126.

29. Jahangir, Jahangirnama, 263–64.

30. Ruymbeke, Science and Poetry, 137.

31. Hussain, Scent in the Islamic Garden, 131; Shirazi, Ulfaz Udwiyeh, 19–21.

32. Bayaz-i Khushbu’i, f.12a-19b; Shirazi, Ulfaz Udwiyeh,19–21; Al-Samarqandi, The medical Formulary, 66.

33. Bhakkar, Dhakhirat ul-Khawanin, 1:50–51.

34. While the impact of Fuṣūṣ’ olfactory expositions on the Mughal mentality has hitherto not been studied, the influence of Fuṣūṣ’s doctrines of waḥdat al-wujūd (unity or oneness of being) and insān al-kāmil (divinely ordained perfect being) on Mughal political thought and the practices of Chisti and Qadiri Sufi orders active at the Mughal court is well documented. See Alam, “The Mughals, the Sufi Shaikhs,” 162, 169–170; Habib, “A Political Theory,” 331; Franke, “Emperors of Ṣūrat,” 130–131.

35. Zargar, Sufi Aesthetics, 50–51.

36. Ibid., 49.

37. Percolation of Yūnānī and Akhlāqī discourses in Sufi philosophy is emblematic of Franz Rosenthal’s argument that medieval and early modern Islamic scholars considered all forms of knowledge as interconnected parts of the all-encompassing ‘ilm of religious truth. Rosenthal, Knowledge Triumphant, 1–2, 41–44.

38. Price, “Extracts from the Mualijāt,” 45–46.

39. Steingass, A comprehensive Persian-English Dictionary, 534.

40. Al-Samarqandi, “Ibn Māsawaih,” 397; King, Scent from the Garden, 273–5.

41. Ruymbeke, Science and Poetry, 132, 137.

42. For use of aromatics to treat ailments by employing the principle of contrary, see, Khurasani, “Tibb-a-Yousufi,” 107–115.

43. Babur, Baburnama, 299.

44. Ibid., 418.

45. Jahangir, Jahangirnama, 348.

46. Saxena, Tarikh-i-Dilkasha, 151–52.

47. Ahmad, “The British Museum Mirzanama,” 104.

48. Fazl, Ā‘īn-i Akbarī, 1:77–78. For examples of different methods for preparing betel rolls, see The Niʻmatnāma Manuscript, 48–50.

49. Shirazi, Fawāʾid al-Insān, f.102a.

50. For instances highlighting betel roll consumption at Mughal court, see, Khan, Maasir-i Alamgiri, 22, 64, 96, 100, 172.

51. Mundy, The Travels of Peter Mundy, 2:96–97.

52. Shirazi, Ilajat-i Dara Shikuhi, ff.11b-12a, f.36b.

53. Ahmad, “The British Museum Mirzanama,” 104; Fazl, Ā‘īn-i Akbarī, 1:68.

54. Fazl, Ā‘īn-i Akbarī, 1:72–73. Jahangir, Jahangirnama, 24.

55. Ahmad, “The British Museum Mirzanama,” 103–104.

56. Ibid., 103; Risala-i anwa‛-i Taʻam, f. 28, 84, 85, 138.

57. Fazl, Ā‘īn-i Akbarī, 1:88–89; Risala-i anwa‛-i Taʻam, f. 112.

58. Khwan-i Alwan-i Niʻmat, ff.35a-b, 83b-84a; Risala-i anwa‛-i Taʻam, f. 24–25, 30–31. 57, 63.

59. Al-Israili, Kitab al-Aghdhiya, 164.

60. Vermani, “From the Cauldrons of History,” 451–452.

61. Vermani, “From the cauldron of history,” 448.

62. Matthee, The Pursuit of Pleasure, 38.

63. Kueny, The Rhetoric of Sobriety, 105–115; Khare, “The Wine-Cup in Mughal Court,” 155.

64. Hattox, Coffee and Coffeehouse, 54–56; Al-Marghinani, The Hedaya, 2:53–58.

65. Jahangir, Jahangirnama, 184.

66. Seyed-Gohrab, “The Rose and the Wine,” 75; King, Scent from the Garden, 277.

67. Ahmad, “The British Museum Mirzanama,” 106; Subtelny, Visionary Rose, 15.

68. Gruber, “The Rose of the Prophet,” 233–238.

69. King, Scent from the Garden, 319–20.

70. Jahangir, Jahangirnama, 224.

71. Ahmad, “The British Museum Mirzanama,” 101.

72. For instance, the eighteenth-century Mughal painting in the British Museum collection that depicts Hasan Ali Khari reclining on cushions while smoking from a long pipe and holding a rose close to his nose. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1974–0617-0-10-56; Also see, seventeenth-century painting that depicts two noblemen sitting facing each other and smoking from hookahs. The figure on the left can be seen holding a bunch of narcissus. A spray of narcissus can also be noticed next to the figure seated on the right. Flowering trees and slender cypresses can be seen in the background. This painting is a part of a private collection has been reproduced as image number 14 in Forge and Lynch Exhibition Catalogue 2017.

73. Schimmel, A Two-colored Brocade, 164–65; Kashani, “Ramz al-Rayāhin,” 300–301.

74. Seyed-Gohrab, “The Rose and the Wine,” 72; Schimmel, A Two-colored Brocade, 165, 389.

75. Ruymbeke, Science and Poetry, 89.

76. Qazwini, ‘Ajā’ib al-Makhlūqāt, f.89 v.

77. Image number 20 in Forge and Lynch Exhibition catalog, 2017.

78. V&A Museum, image accession number IM.252–1921.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O405517/painting-unknown/.

79. Gelder, Of Dishes and Discourse, 65.

80. Khwan-i Alwan-i Niʻmat, ff.32b-33a, ff.33a-33b, ff.60a-68a, ff.88a-88b.

81. Subtelny, Visionary Rose, 21–24; Gruber, “The Rose of the Prophet,” 233–35.

82. For other examples, see gemstones studded Mughal rose-water bottles from Al-Thani collection (https://www.thealthanicollection.com/recently-shown-highlights/rosewater-bottle) and Christie’s collection (https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6211875); Also see, boxes to hold betel leaf rolls, cups and platters in Salomon de Rothschild Collection at Louvre Museum, Paris (https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010330640; https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010329545; https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010330646; https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010330645).

83. Melikian-Chirvani, “Precious and Semi-Precious Stones,” 130–131. Shirazi, Ulfaz Udwiyeh, 19–21.

84. History of India as told, xx-xxi.

Bibliography

- Aftabachi, Jawhar. Tadhkirat u’l-Wāqīāt [Remembrance of Occurrences] in Three Memoirs of Humāyun. Translated by Wheeler M. Thackston. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, 2009.

- Ahmad, Aziz. “The British Museum Mirzanama and the Seventeenth Century Mirza in India.” Iran 13, no. 1 (1975): 99–110.

- Alam, Muzaffar. The Languages of Political Islam: India 1200- 1800. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Alam, Muzaffar. “The Mughals, the Sufi Shaikhs and the Formation of the Akbari Dispensation.” Modern Asian Studies 43, no. 1 (2009): 135–174. doi:10.1017/S0026749X07003253.

- Al-Din Al-Samarqandi, Najib, and Muhammad ibn Ali. The Medical Formulary of Al-Samarqandi and the Relation of Early Arabic Simples to Those Found in the Indigenous Medicine of the Near East and India. Translated by Martin Levey and Noury Al- Khaledy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1967.

- Ali, Athar. The Mughal Nobility Under Aurangzeb. New Delhi: Asia Publishing House, 1970.

- Al-Israili, Ishaq Sulayman. Kitāb Al-Aghdhiya Wa’l-Adwiya [Book of Aliments and Drugs].Edited by Muhammad Al-Sabah Beirut: Mu’assasat ‘Izz al-Dīn li’l-Ṭibā a wa’l-Nashr,1992.

- Al-Marghinani, Burhan al-Din. The Hedaya, or Guide: A Commentary on the Mussulman Laws. Vol. 2. Translated by Charles Hamilton. London: T. Bensley, 1791.

- Al-Samarqandi, Muhammad ibn Ali Najib al-Din. The Medical Formulary of Al-Samarqandi and the Relation of Early Arabic Simples to Those Found in the Indigenous Medicine of the Near East and India. Translated by Martin Levey and Noury Al-Khaledy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1967.

- Avicenna. Avicenna’s Psychology: An English Translation of Kitāb Al-Najāt, Book II, Chapter VI, with Historico-Philosophical Notes and Textual Improvements on the Cairo Edition. Translated by Rahman, Fazlur, Westport, CT: Hyperion Press, 1981.

- Bayat, Bayazid. “Tārīkh-i Humāyūn [History of Humayun] in Three Memoirs of Humāyun. Translated by Wheeler M. Thackston. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2009.

- Bayazi- Khushbu’i [Fragrant Anthology]. I.O Islamic 828. London: British Library.

- Berger, Rachel. “Between Digestion and Desire: Genealogies of Food in Nationalist North India.” Modern Asian Studies 47, no. 5, February (2013): 1622–1643. doi:10.1017/S0026749X11000850.

- Bhakkar. Shaikh Farid. Dhakhirat Ul-Khawanin [Treasure of Elites], Part-1. Translated by Ziya Ud-Din A. Desai, 2009. Delhi: Idrah-i Adabiyat-i Delli.

- Bursi, Adam. “Scents of Space: Early Islamic Pilgrimage, Perfume, and Paradise.” Arabica 67, no. 2–3 (2020): 200–234. doi:10.1163/15700585-12341557.

- Christine Van, Ruymbeke. Science and Poetry in Medieval Persia: The Botany of Nizami’s Khamsa. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 2007.

- Elliot, H. M. The History of India as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period. Vol. 1.Edited by John Dowson. Delhi: Low Price Publication, 2001.

- Evans, Suzanne. “The Scent of a Martyr.” Numen 49, no. 2 (2002): 193–211. doi:10.1163/156852702760186772.

- Fazl, Abu’l. . . Ā‘īn-i Akbarī [Institutes of Akbar], Vol.1. Translated by H.Blochmann. Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1927.

- Fazl, Abu’l. Akbarnama [History of Akbar]. Vol. 1. Translated by H. Beveridge. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, 2000.

- Flatt, Emma J. “Spices, Smells and Spells: The Use of Olfactory Substances in Conjuring of Spirits.” South Asian Studies 32, no. 1 (2016): 3–21. doi:10.1080/02666030.2016.1174400.

- Flatt, Emma J. “Social Stimulants: Perfuming Practices in Sultanate India.” In The Scent Upon the Southern Breeze: Synaesthetic Arts of the Deccan, edited by Kavita Singh, 24–41. Mumbai: The Marg Foundation, 2018.

- Fragner, Bert. “From the Caucasus to the Roof of the World: A Culinary Adventure.” In Culinary Cultures of the Middle East, edited by Sami Zubaida and Richard Tapper, 49–62. London: I.B. Tauris, 1994.

- Franke, Heike. “Emperors of Ṣūrat and Maʿnī: Jahangir and Shah Jahan as Temporal and Spiritual Rulers.” Muqarnas 31, no. 1 (2014): 123–149. doi:10.1163/22118993-00311P06.

- Gelder, G., and J. H. van. Of Dishes and Discourse: Classical Arabic Literary Representations of Food. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 2000.

- Gruber, Christiane. “The Rose of the Prophet: Floral Metaphors in Late Ottoman Devotional Art.” In Envisioning Islamic Art and Architecture: Essays in Honour of Renata Holod, edited by David J. Roxburgh, 223–249. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

- Habib, Irfan. “Potentialities of Capitalistic Development in the Economy of Mughal India.” The Journal of Economic History 29, no. 1 (1969): 32–78. doi:10.1017/S0022050700097825.

- Habib, Irfan. “A Political Theory for the Mughal Empire – a Study of the Ideas of Abu’l Fazl.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress Patiala 59 (1998): 329–340.

- Habib, Irfan. The Agrarian System of Mughal India, 1556-1707. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Hattox, Ralph S. Coffee and Coffeehouses: The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988.

- Hodgson, Marshall. “ The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization. Vol. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

- Hoogervorst, Tom G. “Qaliyya: The Connections, Exclusions, and Silences of an Indian Ocean Stew.” Global Food History 8, no. 2 (2022): 106–127. doi:10.1080/20549547.2022.2041356.

- Hussain, Akbar Ali. Scent in the Islamic Garden: A Study of Deccani Urdu Literary Sources. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Hussain, Akbar Ali. “Perfume and Pleasure in 17th-Century Deccan.” In The Scent Upon the Southern Breeze: Synaesthetic Arts of the Deccan, edited by Kavita Singh, 42-55. Mumbai: The Marg Foundation , 2018.

- Inayat, Khan. The Shahjahan Nama of ʿinayat Khan. Edited and Translated by W. E. Begley and Z. A. Desai. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Isin, Priscilla Mary. Bountiful Empire: A History of Ottoman Cuisine. London: Reaktion Books, 2018.

- Israili, A. H. “Humoral Theory of Unani Tibb.” Indian Journal of History of Science 16, no. 1 (1981): 95–99.

- Jütte, Robert. “The Sense of Smell in Historical Perspective.” In Sensory Perception: Mind and Matter, edited by Friedrich G. Barth, Patrizia Giampieri-Deutsch, and Hans-Dieter Klein, 313–332. Vienna: Springer, 2012.

- Kashani, Mohammad-Hadi b. Habib Ramzi. ““Ramz al-Rayāḥin” [Secret of Fragrant Plants].Edited by Iraj Afshar.” Waḥid 3 (1967): 300–303.

- Khan, Saqi Must‘ad. Maāsir-I-‘Ālamgiri [Achievements of Alamgir or Aurangzeb]. Translated by Jadunath Sarkar. Calcutta: Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1947.

- Khare, Meera. “The Wine-Cup in Mughal Court Culture—From Hedonism to Kingship.” The Medieval History Journal 8, no. 1, April (2005): 143–188. doi:10.1177/097194580400800108.

- Khurasani, Hakim Yusuf bin Muhammad bin Yusuf al-Tabib. “Tibb-A-Yousufi [Medicine of Yusufi].” Hyderabad 3, no. 2 (1965): 107–115.

- Khwan-i Alwan-i Niʻmat [Spread of Varieties of Bounty or Blessings]. Add. 17959. London: British Library.

- King, Anya. Scent from the Garden of Paradise. Musk and the Medieval Islamic World. Leiden: Brill, 2017.

- Kinra, Rajeev. Writing Self, Writing Empire: Chandar Bhan Brahman and the Cultural World of the Indo-Persian State Secretary. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015.

- Korsmeyer, Carolyn, and David Sutton. “The Sensory Experience of Food.” Food, Culture & Society 14, no. 4 (2011): 461–476. doi:10.2752/175174411X13046092851316.

- Kueny, Kathryn. The Rhetoric of Sobriety: Wine in Early Islam. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001.

- Levey, Martin. “Ibn Māsawaih and His Treatise on Simple Aromatic Substances: Studies in the History of Arabic Pharmacology I.” Journal of the History of Medicine 16, no. 4 (1961): 394–410. doi:10.1093/jhmas/XVI.4.394.

- Matthee, Rudolph P. The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History, 1500-1900. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Matthee, Rudolph P. “Patterns of Food Consumption in Early Modern Iran.” Oxford Handbook Topics in History (online edition) (2015): 1–29 doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935369.013.13.

- Melikian-Chirvani, A. S. “Precious and Semi-Precious Stones in Iranian Culture.” Bulletin of the Asia Institute 11 (1997): 123–173.

- Muhammad, Babur, Zahir al-Din. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor.Translated by Wheeler M. Thackston. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institute and Oxford University Press, 1966.

- Muhammad Jahangir, Nur ul- Din. “Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Translated by Wheeler M. Thackston. New York: Oxford University, 1999.

- Mundy, Peter. The Travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia. Vol. 2. Edited by Richard Temple. London: Haklyut Society, 1914.

- Nathan, Mirza. Baharistan-I Ghaybi: A History of the Mughal Wars in Assam, Cooch Behar, Bengal, Bihar and Orissa During the Reigns of Jahangir and Shahjahan. Vol. 2. Translated by M. I. Borah. Gauhati, Assam: The Government of Assam, Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, Narayani Handiqui Historical Institute, 1936.

- Nawwab, Khan, Shah Nawaz Samsamuddaula, and Hayy Abdul. Maathir-Ul-Umara [Achievements of Elites]. Vol. 1. Translated by H. Beveridge. Kolkata: The Asiatic Society, 2003.

- O’Hanlon, Rosalind. “Manliness and Imperial Service in Mughal North India.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 42, no. 1 (1999): 47–93. doi:10.1163/1568520991445597.

- Pifer, Michael. “The Rose of Muḥammad, the Fragrance of Christ: Liminal Poetics in Medieval Anatolia.” Medieval Encounters 26, no. 3 (2020): 285–320. doi:10.1163/15700674-12340073.

- Pormann, Peter E., and Emilie. Savage-Smith. Medieval Islamic Medicine. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2007.

- Price, David Major. “Extracts from the Mualijāt-i-Dārā-Shekohi.” Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 3 (1835): 32–56.

- Qazwini, Zakariya ibn Muhammad. ‘Ajā’ib al-Makhlūqāt wa-Gharā’ib al-Mawjūdāt [Wonders and Rarities of Creation]. Or.14140. . London: British Library

- Rahman, Syed Zilur. “Unani Medicine in India: Its Origin and Fundamental Concepts.” In History of Science, Philosophy and Culture, Vol.Vi/2 (Medicine and Life Sciences in India), edited by B. V. Subbarayappa, 298–325. New Delhi: Centre for Studies in Civilizations and Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2001.

- Ray, Utsa. Culinary Culture in Colonial India. Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Risāla-i Anwā‘-i Ta’ām [Treatise of Varieties of Food Dishes] Ms. 46463. : London: Special collection SOAS Library, undated

- Robinson, Francis. “Ottomans-Safavids-Mughals: Shared Knowledge and Connective Systems.” Journal of Islamic Studies 8, no. 2 (1997): 151–184. doi:10.1093/jis/8.2.151.

- Rosenthal, Franz. Knowledge Triumphant: The Concept of Knowledge in Medieval Islam. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

- Saxena, Bhimsen. Tarikh-i-Dilkasha: Memoirs of Bhimsen Relating to Aurangzib’s Deccan Campaigns. Translated and edited by V.G. Kobrekar. Bombay: Department of Archives Maharashtra, 1972.

- Schimmel, Annemarie. A Two-Colored Brocade: The Imagery of Persian Poetry. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

- Sengupta, Jayanta. “Nation on a Platter: The Culture and Politics of Food and Cuisine in Colonial Bengal.” Modern Asian Studies 44, no. 1 (2010): 81–98. doi:10.1017/S0026749X09990072.

- Seyed-Gohrab, Asghar. “The Rose and the Wine: Dispute as a Literary Device in Classical Persian Literature.” Iranian Studies 47, no. 1 (2014): 69–85. doi:10.1080/00210862.2013.825506.

- Shirazi, Ain ul-Mulk Fida’i. Fawa’id al-Insan [For the Benefits of Human Beings]. Or.683. Cambridge: Cambridge University Library .

- Shirazi, Nur al-Din Muhammad. Ulfaz Udwiyeh or the Materia Medica in the Arabic, Persian and Hindevy Languages, Translated by Francis Gladwin. Calcutta: Chronicle Press, 1793.

- Shirazi, Nur al-Din Muhammad .‘Ilajāt-i Dārā Shikūhī [Remedies of Dara Shikuh]. Codrington/Reade no. 196. . Vol. : London: Royal Asiatic Society. .

- Steingass, Francis Joseph. A Comprehensive Persian-English Dictionary. London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1892.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. “Connected Histories: Notes Towards a Reconfiguration of Early Modern Eurasia.” Modern Asian Studies 31, no. 3 (1997): 735–762. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00017133.

- Subtelny, Maria. “Visionary Rose: Metaphorical Interpretation of Horticultural Practice in Medieval Persian Mysticism.” In Botanical Progress, Horticultural Innovation and Cultural Changes, Volume 28, edited by Michel Conan and W. John Kress, 13–34. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection and Harvard University Press, 2007.

- The Niʻmatnāma Manuscript of the Sultans of Mandu: The Sultan’s Book of Delights. Translated by Norah M. Titley. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2005.

- Tusi, Nasir ad-Din. The Nasirean Ethics, Translated by G. M. Wickens. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1964.

- Vabre, Sylvie, Martin Bruegel, and Peter J. Atkins, eds. Food History: A Feast of the Senses in Europe, 1750 to the Present. New York: Routledge, 2021.

- Vermani, Neha. “From the Court to the Kitchens: Food Practices of the Mughal Elites (16th to 18th Century).” PhD Dissertation, Royal Holloway University of London, 2020.

- Vermani, Neha. “From the Cauldrons of History: Hidden Labor of Kitchen Work at the Mughal Court.” Journal of South Asian History and Culture 13, no. 4 (2022): 445–465. doi:10.1080/19472498.2022.2050027.

- Zargar, Cyrus Ali. Sufi Aesthetics: Beauty, Love, and the Human Form in the Writings of Ibn ‘Arabi and ‘Iraqi. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2011.