ABSTRACT

This paper examines the emergence and development of a new soundscape of work in the open-plan office. To understand the persistent tension between public social interaction and private undisturbed work in many open-offices today, I argue that we need to account for the perceptual engineering that has been built into its very concept. To do so, I reconstruct the development and reception of Action Office 2, a pioneering and influential open-plan office concept that was launched by manufacturer Herman Miller Inc. in the late 1960s. I show how its designers sought to optimise the office as an informatic system by balancing workers’ experience of exposure and enclosure in the open-plan office. This informatic challenge coincided with a new approach to office acoustics in the 1960s and 1970s that focused on managing intelligibility and improving privacy rather than noise. Examining this “perceptual technic” reveals how noise became an architectonic element that served to optimise and economise a relation between private and public experience of work. Ultimately, I argue, this technic and the sound masking technologies that derive from it have helped sustain both the open-plan office to the present day, but also the tensions underlying it.

Introduction

Although a lot of office work today takes place in open-plan environments, such environments reflect a deep-rooted tension. On the one hand, the open-plan office has long been promoted for facilitating the social interaction and serendipitous meetings that foster a motivated and innovative workforce (Tett Citation2021). On the other hand, workers often experience the open plan as a noisy and distracting space, where it may be difficult to get any “work done” (Burkeman Citation2018; Perry Citation2022; Somaiya Citation2008). This has led office designers and facility managers to experiment with acoustically proofed “phone booths”, private meeting pods or inflatable acoustic walls (Clifford Citation2021). Office workers, meanwhile, have sought their own means of acoustic control, with dedicated playlists, sound generators or noise-cancelling headphones, that promise the concentration required for functioning in the post-industrial workspace (Dibben and Haake Citation2013; Droumeva Citation2021; Plourde Citation2017; Ris Citation2021). This tension, however, is hardly new. In fact, as this paper shows, it reflects a sensory-social organisation that has been layered in the open plan’s material infrastructure by its very design.

The contemporary open-plan office has been traced back to concepts that gained traction in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly in Germany, Britain and the United States (Kaufmann-Buhler Citation2021; Schwartz Citation2002). Existing historical scholarship has charted, among others, how the open-plan office materialised new managerial philosophies as well as cybernetic ideas about communication and information exchange (Murphy Citation2006; Rumpfhuber Citation2013). As Hong (Citation2017) has argued, the open-plan office’s material and aesthetic design promoted a “fantasy of information work” as transformational, pleasurable and frictionless. In such an “informatic” view, open-plan offices were expected to eliminate the hierarchical and static structures (as represented by the private office) that tended to clog up the channels of information that organisations were vitally dependent on. Instead, the open layout supported a horizontal and flexible organisation within which self-directing professionals could exchange and collaborate, allowing information to flow uninterruptedly. However, from the start, many workers experienced the new open-plan office as anything but frictionless (Kaufmann-Buhler Citation2021). Their frustrated acoustic experience of distractions and lack of auditory privacy suggested that the informatic ideal was difficult to maintain in practice. Attending to how these informatic and acoustic understandings of the workspace were subsequently negotiated, I argue, provides insight in how both the open-plan office concept as well as the tension underlying it have persisted until the present day.

To trace how this tension was negotiated, I focus on the case of Action Office 2 (henceforth AO2). Designed by Robert Propst and launched in 1968 by furniture manufacturer Herman Miller Inc., AO2’s system furniture is widely regarded as a pioneering, influential and long-standing icon of the open-plan office in the United States (Kaufmann-Buhler Citation2021). Drawing on published and archival sources related to AO2, I argue that Propst promoted an informatic conception of the office that concerned not just its material layout but also workers’ own sensory perception, as he sought to modulate workers’ exposure to sensory stimuli and distractions, or signal and noise, in intricate ways. Focusing on AO2’s initial reception and its aftermath, I reconstruct the perceptual engineering and sound technologies with which designers and acoustical engineers sought to negotiate informatics and acoustics in the office. In the 1970s, this approach materialised in a new line of sound masking technologies, which employed finely tuned noise spectra to mask intelligible speech in the office and promised to “tune” the conditions of comfortable and productive work in the office.

Reading the architectonics of the workspace critically through the lens of sound studies contributes to existing scholarship in several ways. First, it illustrates how a “modern soundscape” in the workplace was reconfigured into a late modern “workscape”.Footnote1 In Emily Thompson’s classic account, a shift in the science of architectural acoustics at the turn of the twentieth century had prompted a new sensory-spatial condition that was organised around the control of sound and noise. This is evident among others in the widespread application of acoustically engineered materials with absorptive qualities, which aimed to reduce noises and distracting reverberations in the workplace and other public spaces. By 1970, acoustical engineering relied on similar materials and techniques. But as this paper shows, it also framed the problem of noise in a starkly different way: rather than a sensory disruption or a source of inefficiency, noise was now understood in the informational terms of intelligibility. Instead of reducing noise, then, this led them to introduce noise as an instrument to condition the acoustic environment. As such, this case illustrates one widespread implementation of what Jonathan Sterne (Citation2012) has described as a post-war turn towards the “domestication of noise”.

More generally, this article contributes to studies on the politics of sound and listening in the demarcation of private and public space (Born Citation2013). One classic strand of work in sound studies has examined how acoustic engineering offered a new kind of control to organise and texture public architectural space, often in ideologically tinted ways (Sterne Citation1997; Thompson Citation2002; Touloumi Citation2014; Wittje Citation2016). As historians of work and sound have shown, this was also the case in the workplace, where auditory ambiences have long been tailored and regulated in an attempt to manage workers’ rhythms, affect and productivity (Grajeda Citation2013; Hui Citation2014; Jones Citation2005; Korczynski, Pickering, and Robertson Citation2013). Another strand has shown how sound technologies have afforded the individual a new form of sonic control by carving out acoustically private, mobile and personalised self-enclosures (Bull Citation2007; Hosokawa Citation1984; Weber Citation2010). In the workplace, sound studies scholarship has highlighted how headphones and playlists function as technologies of self-care and self-isolation (Plourde Citation2017; Droumeva Citation2021; Dibben and Haak Citation2013). As Hagood (Citation2019) shows, noise emerges as one such orphic technology that promises a new degree of individual control over one’s personal surroundings, by burying acoustic difference behind a wall of sonic sameness.

Such sound studies scholarship has presented the workplace as a product of these largely separate and opposing forces of (self-)control. This paper complicates that notion, by highlighting a particular intersection of regulation, control and care. It does so, first, by tracing how the workspace was acoustically regulated to meet an individual desire for acoustic privacy and self-control, and to protect the individual against auditory distractions. However, the experience of acoustic self-enclosure is perceptually engineered on behalf of the individual, but not by the individual. As such, it pre-empted acoustic self-isolation (for instance through headphones). Second, such acoustic enclosure was engineered to serve as a consistent form of architecture. As such, it tends to be more fixed and provides much less opportunities for individual control and adjustment than other technologies of acoustic self-care. It is based, after all, on particular expectations of individual tolerance for noise and acoustic privacy that are based on a perceptual technic of aggregated and statistically knowable listening behaviours and preferences. Ultimately, I argue, this perceptual technic has been calibrated not to maximise employees’ acoustic comfort, but rather to economise and maintain an informatic logic of information flow in the workplace.

In the sections that follow, I briefly reconstruct the informatic assumptions underlying the open-office concept, before discussing how these materialised in the Action Office 2. I then reconstruct how workers’ complaints forced Herman Miller to adopt an acoustic perspective instead, before examining how this perspective came to revolve around the concept and practice of sound masking. I conclude by discussing how sound masking became integral to the architectonics of the office.

Managing information exposure

In the late-1960s, the office was reimagined as the materialisation of an emerging knowledge economy. Against the background of a post-war economic boom and aided by technological advances in lighting and climate control, project developers, architects and corporations favoured building designs that maximised floor space and organisational flexibility. American offices had long been divided in private offices for executives, managers and professional staff, and so-called “bullpen” open areas for lower-level clerical workers (Bernasconi and Nellen Citation2019). But by the late 1960s, management consultants, architects and furniture designers began to promote the open-plan layout as a radically new way of organising office work (Kaufman-Buhler Citation2021). Within the United States, the concept of the open-plan office had been pioneered by Robert Propst. An inventor, and head of a new research division at furniture manufacturer Herman Miller Inc., he was responsible for developing and launching its Action Office 2 as one of the first systems of modular furniture designed specifically for the open-plan concept.

In a pamphlet titled The Office. A Facility Based on Change (Citation1968) that accompanied the launch, Propst presented the open-plan office as a model for the future. Within a quickly changing economy, he predicted, office facilities had to be flexible to organisational change, allowing them to grow or contract with the organisation. For decades, the office had been envisaged as a paper-handling machine. This had been spatially encoded in its layout too: desk-based clerical workers formed a clear grid, processing paper information that travelled up the hierarchical chain to executives’ private offices. But channelling a broader cultural concern with “information overload” (Levine Citation2017), Propst countered that such centralised command was ill-adapted to the complex information streams that modern organisations now depended on.

Instead, he envisaged a spatial form that reflected a much more decentralised organisational structure that encouraged office workers of all levels to adopt more responsibility in managing their tasks. This ideal borrowed from influential management theorist Peter Drucker (Citation1959) who presented “knowledge workers” as autonomous professionals whose job revolved around critical judgement, problem solving and collaboration. Such ideals also aligned with a major shift in management theory which emphasised that productivity required more attention to human relations than top-down managerial control over worker and environment. Popularised in the 1960s, among others by psychologist Douglas McGregor (Citation1960), this theory promoted a management style that gave space to initiative, creative problem-solving and involvement in decision-making. Action Office 2 was designed to embody and promote this progressive philosophy (Kaufmann-Buhler Citation2021).

Action Office 2 was partly modelled on a planning technique called Organisationskybernetik, which had been pioneered by the Hamburg management consultancy firm Quickborner Team in the late 1950s. The firm pioneered a method for organising work processes based on actual, rather than ideal communication patterns in an organisation. Charting workers face-to-face, telephone and paper exchanges through interviews and questionnaires, the consultants determined an ideal floor plan, such that frequently interacting individuals (regardless of function, status or privilege) were clustered in physical proximity to one another. Prioritising efficiency of communication over an aesthetic of geometric order, such floorplans abolished private offices and instead distributed workstations across the open floor in what they termed an “office landscape”. Independent of fixed wall-panelling or private offices, this spatial regime was both flexible and cost-effective. In prioritising face-to-face interaction over standard office communication technologies, it also promoted direct communication – unfettered by fixed walls and isolating private enclosures – as one of the office’s central functions. Axel Boje, a German consultant on office landscape planning, for instance, praised the open office concept as a means to achieve “optimum information flow unhindered by doors and unnecessarily long distances” (Citation1971, 8).

From the perspective of its advocates, the advantages of unhindered communication clearly outweighed its drawbacks. For instance, Boje (Citation1971) argued for the profitability of open over closed offices, with a detailed calculation to show that the effect of any “secondary distractions” (such as noticing a passer-by or hearing office noises) would be offset by a sharp reduction in “primary distractions” (such as unnecessarily ringing telephones or visitor interruptions) and an effective increase in efficiency (expected to be between 16% and 25%). This was because the constant but distributed activity in the open-plan office would effectively stimulate workers to draw more on their “output reserves”. Since their activities would be visible and audible to all, Boje reasoned, workers would be inclined to limit their private occupations at work, be absent from work less and distribute the workload among colleagues more loyally and efficiently. An open layout and atmosphere, in other words, stimulated workers to put their best behaviour on.

Propst identified similar advantages for the Action Office 2 concept. But he did advocate a more careful and reserved approach to managing the office as an open information system. On the one hand, he argued, involvement was an “essential need” among office workers. Too often, the symbolic value of a private office had deprived workers of key exposure to their colleagues. Likewise, too often an over-concern with privacy indicated a retreat from responsibility and sagging motivation. An open-plan promised to mediate that. On the other hand, Propst recognised personal privacy as an instinctual and therefore necessary concern. Completely open environments (like the German office landscape), he argued, tended to distract and irritate workers by too much exposure (Propst Citation1968). To avoid information overload, not just at an organisational level but also at an individual and personal level, knowledge workers could not just be placed as “sideless, senseless particles” in an open space for the benefit of communication (Propst Citation1968, 27). With the office teeming with “signals, sensations, and perceptual combinations”, Propst proposed, it thus had to act as a “capacity regulator” that filtered vitalising stimuli from those that were distracting (or even destructive) to workers’ intentions.Footnote2

Offices thus had to be finely calibrated as environments that balanced the conflicting needs of exposure and involvement. To do so, Propst drew from environmental psychology, an emerging field of social sciences that considered architecture, spatial arrangements and material surroundings, from table placement to the layout of parks, as key tools for managing the social, emotional and mental well-being of their users. Although the fledgling discipline’s insights were difficult to generalise, they were widely embraced by designers, architects and urban planners (Sachs Citation2018). As Knoblauch (Citation2020) has shown, in the 1960s and 1970s, “psychological functionalism” widely informed the design of hospitals, community centres, prisons and community housing. Office design was no exception to this.

Against this background, Propst was particularly inspired by the work of anthropologist Edward Hall and social psychologist Robert Sommer on the notion of “personal space”. This notion had originated with Hall’s approach to the “study of how man unconsciously structures micro-space”, an approach he developed while employed at the U.S. State Department’s Foreign Service Institute to train diplomats in navigating cross-cultural differences abroad and which he later systematised as “proxemics”. With a keen eye for micro-cultural patterns, Hall (Citation1959) influentially theorised that humans possessed a sense of personal space – a culturally conditioned territorial bubble that affected the distances at which they felt comfortable interacting with others. Such spatial relations, it seemed, were unconscious but did shape individuals’ perception of their environment. Hall later conceptualised this “personal space” as a culturally defined series of zones of social and perceptual distance that people organised around themselves in different settings, using architecture, material furniture and their own non-verbal behaviour. Although personal space was in principle multi-sensory, Hall conceptualised it primarily in visual terms – with its olfactory or auditory dimensions limited to just a few intercultural generalisations (Hall Citation1966).

UC Davis social psychologist Robert Sommer, another of Propst’s influences, later investigated the specifications of personal space through sociometric experiments by varying spatial dimensions in mental health wards, libraries, dining halls and bus stations and analysing the resulting interactions (Sommer Citation1966). Both Sommer and Hall explicitly urged designers and architects to take note of the ways in which architecture organised man’s proximate environment. Sommer (Citation1969) illustrated this, for instance, with a series of studies commissioned by the Office of Civil and Defence Mobilisation which had sought to determine the minimally amount of living surface and privacy that individuals required to live in extreme environments such as Antarctic field stations or space missions. One such study had examined the physical, psychological and behavioural effects of “perceptual overloading” on their inhabitants (Dunlap and Associates Citation1963). For instance, the study had sought to quantify how much noise co-habitants were willing and capable to tolerate in function of their physiological stress and ability to communicate. Sommer and Hall themselves underscored that the thresholds that defined personal space were highly variable, both culturally and individually, and that their results hardly offered a formula with which spaces could be optimised. However, designers such as Propst eagerly adopted their concepts as principles of design.

Drawing on Hall and Sommer’s work, Propst sought to determine an optimal balance between privacy and involvement in the open-plan office. To that end, Action Office 2 offered a system of interlocking workstations, panels and standing storage units that could be combined in a honeycomb-like structure of 240° semi-enclosed cells. Whereas private offices had effectively insulated workers from interaction, and open bullpens or office landscapes threatened to expose them to a point of discomfort, Action Office was designed to provide each worker a small and partial territorial enclave fitted to their needs. These cells were connected by narrow lanes and open conference spaces designed to prompt ad-hoc interactions. Open, yet out of sight, such “personal arenas” aimed to make workers feel less visibly exposed or distracted while keeping them directly accessible to their colleagues for interaction or surveillance. Importantly, Action Office was designed not to provide workers a comfortable retreat from the open-plan activity, but rather an enclosure that was just enough for its occupants to feel naturally protected and meet what Propst considered to be a basic condition for productivity.

Action Office’s flexible structure allowed this balance between exposure and enclosure to be adjusted further. While acknowledging that not every individual shared the same experience of personal space, Propst insisted that there was not a problem that could not be solved through basic etiquette or the “soft control” of design. In this view, it was exactly Action Office’s openness and the environmental awareness that it promoted that provided the necessary opportunities for cycles of corrective feedback: co-workers’ awareness of each other’s proximity would lead them to automatically modulate their acoustic presence, voice levels and tendency towards interruption – more, in fact, than they would in a “private” office. If necessary, so-called extroverts could be enclosed more with additional wall-panelling, while excessive interaction could be modulated by repositioning workstations. Propst recommended that organisations give themselves and sceptical employees a year to learn to inhabit such an open space.

Tuning acoustic privacy

By 1970, planning and designs firms in the United States began to widely implement the open-plan office concept. In 1973, Herman Miller’s Action Office 2 listings read like a who’s who of American corporations, including IBM, Xerox Corporation, Ford Motor Company and Polaroid, as well as more traditionally conservative office users such as banks and governmental agencies.Footnote3 In the course of the 1970s and 1980s, moreover, its open-plan furniture system spun off in over a dozen competing systems, by firms such as Steelcase, Knoll and Eppinger (Kaufmann-Buhler Citation2021). Therefore, it was estimated that by the early 1980s, more than half of American office workers worked in an open-plan office (Dzubay Citation1997). But despite its widespread adoption, workers remained sceptical about the open-plan concept.

Although a series of post-occupancy evaluations and attitude surveys generally found more communication and information flow, actual improvements in staff productivity proved hard to demonstrate (Fucigna Citation1967). What these studies did show, however, was a marked increase in a perceived “lack of privacy” (Brookes Citation1972; Riland Citation1970). When surveyors asked users to compare their experiences in open-plan offices to their conventional spaces, complaints turned out to be plenty and variate. While privacy had always been tentative, even in a private office, designers’ attempt to level this privilege was associated by some (mostly managers) with a loss in status, and by others (mostly employees) with an increase in surveillance. More often, however, privacy was framed in strikingly informational terms: in the conventional sense of the word, managers were concerned about loss of confidentiality of information in meetings, while for employees privacy connoted their defencelessness against visual and acoustics interruption and especially noises on the work-floor, which affected their ability to execute their work.Footnote4

A book-length post-occupancy study of the new headquarters of farm machinery manufacturer John Deere and Co., designed by star architect Eero Saarinen illustrates this (Hall and Hall Citation1975). The authors concluded that the building’s partitioned open floors had seemed to improve work tempo and productivity. But they also noted that many employees complained about constant visual and auditory interruptions. Workers felt distracted by intrusions of animated conversations, duelling typewriters, ringing telephones, machine handling and even the ambient noises generated by HVAC units. The “stimulation of constant interpersonal interactions” became unbearable in some spaces, where secretaries’ desks were placed so close to one another that constant interruptions “broke the action chain” of their tasks (ibid. 30). Meanwhile, employees on the executive floor had become concerned over a lack of their own acoustical privacy, with sound travelling often uninterruptedly across the office floor. Whether workers’ concerns were motivated by status, surveillance or comfort, then, framing their diminished control over the workspace as a problem of acoustic privacy and disturbance effectively subverted claims to the open-plan office’s usefulness. After all, if the open-plan office had promised to manage information overload, distraction and lack of privacy – channelling a long-standing concern over noise as a distraction and disruption to “mental labor” – now threatened to undercut that promise (Bijsterveld Citation2008; Picker Citation2003).

Herman Miller initially sought to address the problem of acoustic privacy in conventional ways. Open-plan acoustics had been a subject of technical intervention since the 1920s, and since then an entire industry had emerged around sound absorptive technologies, such as floor carpeting, acoustic tile ceilings and isolating wall panelling that provided means to reduce reflections of ambient noises in the office (Martin Citation2019; Thompson Citation2002). In the 1970s, Herman Miller instituted an Environmental Technology Service for solving post-occupancy issue and published Action Office Acoustic Handbook (Citation1975), a reference tool for facility managers, planners and designers seeking to control noise in the open office. This handbook, along with promotional materials, argued that “most moderate acoustic difficulties” could be relieved by “small tuning adjustments” (p. 45) while maintaining Action Office’s spatial integrity. Such metaphoric tuning work involved adapting parts of the built and social environment – its ceilings, carpeting or people – to a baseline value of desired sound, much like one would with a musical instrument.

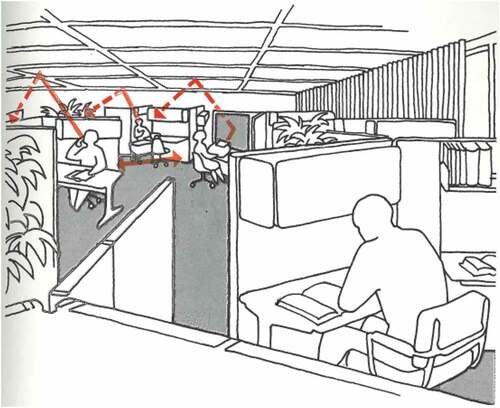

This metaphor does conceal, however, how reorganising the office environment around “acoustic privacy” in fact required a complete reconceptualisation of its informatic model, and with it the spatial and social topology of the office. Crucially, distance and proximity were no longer reliable indicators for how information travelled and how space was demarcated. As the complaints about acoustic distraction made clear, information was not easily contained or channelled within the visual territorial boundaries and relations of proximity that had informed the basic vocabulary of Action Office. In fact, redefined as an acoustic relation, information was subject to a high degree of leakage and entropy. As Robert Propst and environmental consultant Michael Wodka noted, concerns about privacy emerged when auditory zones did not coincide with spatial zones: “If they do not, the results are unsettling. If we can hear and understand the speech of unseen outsiders and know that they can hear and understand us, the effect is insidious. We are given space that suggests privacy on one hand, but fails to deliver on the other” (Citation1975, 9). As a series of images from the Acoustics Handbook suggests, then, information travelled along vectors that were reflected, redirected, amplified, attenuated and absorbed in complex ways by the material layout of the office environment (). In order to engineer a sense of privacy, work zones thus had to be adjusted with even more care for acoustics.

Figure 1. “How sound travels”. From: Propst and Wodka (Citation1975, 31). Courtesy of the Herman Miller Corporate archives.

Along with other suppliers of office interiors and building materials, by the 1970s, Herman Miller redeveloped and branded its products (such as acoustic panelling) as part of an integrated system to tune the open-plan office. But such technologies were to be used judiciously. By its inherent ability to define space, control traffic and reduce distractions, Propst insisted, Action Office already automatically reduced the acoustical problems found in traditional offices (Herman Miller Citation1976a). Moreover, while panel screens could be used to insulate individuals from some acoustic interference, their visual separation and invisibility could also reinforce the problem further, by reducing their environmental awareness and opportunities for feedback and thus increase acoustic irritations again. Resolving the problem of privacy in the open-plan office thus required tuning a balance of visual and acoustic exposure as well.

Redefining noise

Reducing absolute noise levels and controlling how sound travelled were only part of the solution. Solutions to the problem of privacy and distraction in the office were ultimately drawn from a radically different conceptualisation and approach to the problem of office noise that had taken shape in the decade preceding. Noise reduction in the office had typically been based on the premise that noise produced loss of efficiency, not least as a source of physiological or psychological stress (Broadbent Citation1958; Mansell Citation2017; Kryter Citation1950). Yet by the late 1950s, consultants in architectural acoustics had begun to redefine the problem of noise in the office in starkly informational terms; as a form of interference, less with physical health than with the content of speech communication. This shift is best illustrated by the influential work taking place at the acoustical consultancy Bolt, Beranek and Newman (henceforth BBN).

The group BBN had been formed by Leo Beranek and his colleagues to repurpose the expertise in acoustical engineering they had gained in the preceding wartime years. Beranek had directed the Harvard acoustical laboratory that undertook acoustical research for defence purposes. Tasked, among others, with engineering improved communication acoustics in vehicle cockpits under conditions of combat, this had prompted extensive lines of research and testing noise reduction materials as well as the acoustic performance of speech communication systems (Beranek Citation2008). As has been well documented in Beranek’s memoirs, in the post-war period, Beranek formed a partnership with his MIT colleagues Dick Bolt and Bob Newman to consult on a variety of acoustical problems. Working on problems in architectural acoustics (of auditoria, offices and, famously, the United Nations assembly), noise reduction and speech intelligibility led BBN consultants to reconceptualise the problem of office noise in two ways.

BBN’s first contribution to a reconceptualisation of the problem of office noise was to quantify (and thereby to standardise within a metric) workers’ tolerance for particular noise levels. Having been contracted to study noise complaints in offices on a U.S. Airforce base in the mid-1950s, Leo Beranek had measured absolute noise levels – generated by aircraft on the surrounding runways – that office workers were exposed to and sought to determine their impact on office workers’ ability to work. But because their behavioural impact on work efficiency were notoriously difficult to determine, Beranek used surveys to solicit workers’ own subjective rating of the noise levels and their interference with their duties, such as conversing on the phone, typing up a report or concentrating on reading. Together with the measurements of sound levels that were collected throughout the day (particularly those octave bands that equalled those of human speech), these were plotted and calculated into a set of so-called Noise Criterion curves, which charted for different groups of office users the maximum acceptable spectrum of room noises (Beranek Citation1957). As subsequent studies in other offices showed, survey responses varied significantly between individuals and conditions. But by calculating a median, Beranek argued, such curves suggested a threshold value that architects and consultants could make good use of when planning acoustic treatment of offices in function of specific job needs. For sure, the resulting metrics did define noise tolerance mostly in terms of interference with employees’ tasks, rather than their subjective sense of well-being or comfort (Casey Citation2005). In practice, judgement remained necessary to see how local customs, expectations and experiences affected individual tolerances. But as a planning instrument, Noise Criterion levels suggested that criteria for noise reduction should not seek to eliminate noise completely but rather to reduce it to those levels of loudness that workers were willing to tolerate.

William Farrell and B.G. Watters, collaborators of Beranek’s at BBN, revisited this idea a few years later, when acoustic isolation manufacturer Owens-Corning commissioned them to come up with simplified methods for modelling noise reduction and predicting the acceptability of office acoustics. In the 1950s, architects had increasingly turned to specify lightweight, flexible partitions to separate private offices. Yet these had come at the cost of acoustical isolation, resulting in complaints about a lack of privacy and noise in the office. While testing building materials for their transmission of noise, the group recognised that speech privacy constituted a particular problem. Subsequent psychophysical tests with office workers, who completed a variety of tasks while speech, noise and insulation with neighbouring offices were varied, suggested that not all noises were equal (Farrell and Watters Citation1959). Noises, they reasoned, were less easily tolerated when they were intelligible. After all, whispers in a silent library were typically more disturbing than a raised voice in a noisy bar, not so much because of their relative loudness, but rather because of the way the signal stood out against a general background ambience. This held important insights for the study and design of privacy in separate offices, as the intelligibility of speech affected the degree of privacy that an environment afforded. Reporting on their experiments in 1962, the consultants explained that “an increase in the background level has the same effect on intelligibility as an increase in noise reduction between spaces” (Cavanaugh et al. Citation1962, 478). This redefined the problem of office noise and privacy from one of absolute levels to levels that were relative to their background. By demonstrating workers’ tolerance for noise and reconceptualising office noise as a problem of intelligibility, BBN’s two-step redefinition of noise helped spark the realisation that noise itself was not by definition a distracting source that needed to be contained. Instead, it could also be a strategic ally to address the dual problems of distraction and privacy in the office.

To reconceptualise and calculate office noise as a relation between intelligible speech and its background levels, the consultants drew on the so-called Articulation Index (AI). The index had descended from a line of pre-war articulation tests by Bell Telephone Laboratories, which had served to determine the acoustic structure of conversational human voice to improve performance of microphones, telephones and receivers. Bell researchers discovered that speech intelligibility varied greatly with frequency and loudness, with high frequency sounds most important to speech comprehension (French and Steinberg Citation1947). During the war, this approach had found its way into the Harvard sound control laboratories that were tasked with improving communication under the intensely noisy conditions of combat (Touloumi Citation2014). The Harvard researchers found that noise within the airplane had a peculiar structure, with all frequencies added together “producing a noise that is to sound what white light is to light” (Carson, Miles, and Stevens Citation1943, 129). Such “white noise” was not so much disabling because it was disagreeable to listeners, but rather because it spoilt radio communications, reducing the intelligibility of speech in the cabin to about 50%. Because aeronautical design did not tolerate acoustic isolation that was heavy enough to be effective, the researchers had focused their efforts on improving the ratio of speech signal to surrounding noises by improving earphones and microphones instead, making use of Bell Telephone Labs studies to measure the impact of noises and distortions on the intelligibility of telephone communications. Harvard researchers continued these tests, to determine the degree to which speech intelligibility through earphones was affected by different acoustical conditions.

Yet to conduct articulation tests with human subjects was laborious and time-consuming. After the war, therefore, the Bell Labs and Harvard researchers systematised their measurements on the average intelligibility of normal male speech into a standardised and highly idealised spectrum, the so-called “Articulation Index” (AI). This index was based on 200 standard values with which the relative contribution of each individual frequency band to a clearly articulated and thus intelligible speech signal could be weighed. A comparison of this standard profile against the acoustic measurements made in any surroundings resulted in a value of a signal-to-noise ratio that was indicative of the intelligibility of human voice in this surrounding (Kryter Citation1962). Although developed to improve intelligibility in speech communication, the BBN acoustical consultants working on the problem of office noise, Bill Cavanaugh and Parker Hirtle, repurposed a simplified form of the articulation index as an inverted measure of privacy. Low intelligibility scores on the AI index equalled, after all, high privacy levels; an AI of 0.20 meant, for instance, that people who were not part of the conversation could understand just 20% of the words spoken, which was generally considered a good level of privacy (Lewis and O’Sullivan Citation1974). Paired with spectra for background noises, the articulation index offered consultants an instrument for working out the bandwidth of speech levels that remained intelligible to bystanders at close distance. Reversely, paired with noise tolerance indices, it also allowed consultants to calculate at what levels background sounds would begin to mask such speech without (at least theoretically) becoming so unacceptably loud that workers’ performance would be affected (see ).

Figure 2. “The Sounds of an Open Office”. From: Hamme and Huggins (Citation1968, n.p).

Of course, speech intelligibility proved far more difficult to predict in a three-dimensional space than for two-directional telephonic communications, and especially if that space was not an enclosed box but the open-plan landscape of the 1970s. As acousticians discovered, the complexity of modelling privacy increased substantially in the open-plan office, as intelligibility was affected by such variables as speaker orientation, effort, distance and the existing architectural surroundings as well as their material finishing. Because the limits acoustic privacy could not always be made to coincide with the physical layout of workstations, acoustical consultants preferred to speak of “circles of influence”. These represented concentric zones that existed around individuals or groups of co-workers with similar requirements, defining a range from completely intelligible to barely audible in function of distance from the source. Limiting speaker intelligibility (and thus enhancing privacy) in the open office involved a careful use of available materials, such as screens, partitions, ceilings and carpets to attenuate and absorb sounds and reduce reflections beyond designated zones. It also required strategic placement of each individual sound source to ensure that sounds that inevitably did travel between zones were rendered as unintelligible as possible to the accidental receiver. For instance, a pool of clicking typewriters could be used to produce a homogenous masking sound that rendered a private conversation in the nearby conference zone unintelligible, except to those participating in the meeting.

This redefinition of the problem of office acoustics from a problem of noise control to one of intelligibility illustrates how a perceptual technic of sound masking was put to use as an instrument of spatial ordering. The notion of “perceptual technic” was coined by Sterne (Citation2012) to describe the aggregate of listening behaviours and preferences into a statistically knowable threshold of human perception that could be used to economise channel capacity in such media as the telephone or the mp3 compression format. But within the architecture of the open office – conceived by Propst and others as an information medium in itself – a threshold ergonomics of noise tolerances and intelligibility indices likewise suggested a way to optimise the information circuit by modulating the conflicting needs of exposure and enclosure. Importantly, drawing on Beranek’s noise criteris, such thresholds were defined not so much from the perspective of employees’ optimal comfort, but rather by their ability to function and be productive. After all, as I will detail below, employees’ demands were not met with more physical enclosure but with a media infrastructure that produced the experience of acoustic privacy while maintaining employees’ visual and physical availability to one another.

Sound masking

In the mid-1960s already, acoustical consultants had begun to look for sounds with frequency spectra that could mask conversations but were not intrusive. Early experiments showed that workers would be more comfortable with sounds that they were already familiar with (Hamme and Huggins Citation1968). Office sounds, for instance, were believed to be stimulating to work, and a general guideline among office planners was to make sure that enough people were placed in each area to create “activity bustle”. But initial experiences with introducing sounds in the office also suggested a fine line existed between resolving and worsening noise complaints. Ventilation or air-conditioning systems could not be amplified evenly enough for human speech, while piped-in music could distract from mental work (Waller Citation1969). A more reliable alternative was found in artificial masking sounds – after all, electronic noise generators had been on the market for domestic use since about 1962 already (Hagood Citation2019, 77).

Sound masking systems offered a more sophisticated control over the properties of masking sound. As a technology, these generators typically entailed nothing more than a random noise generator, a filter, a power-amplifying system and one or more speakers, which broadcasted its electrically generated noise at a lower volume than average conversational speech. Initial models had experimented with a uniform “white noise” spectrum (consistently renamed “white sound”), but this sounded too much like the sound of steam escaping and proved to be a sure way to irritate office workers (Shumake Citation1992; Waller Citation1969). Other developers experimented with more agreeable frequency distributions which, in the words of office planner David Harris, sounded like “ocean surf, whispering pines, or a large water fountain, except very uniform in time and space” (Citation1981, 58).

From the mid-1970s, several firms began advertising such electronic sound masking systems, initially as stand-alone systems, such as Sound Industries’ Husher or Herman Miller’s own Acoustic Conditioner. The Acoustic Conditioner, for instance, was a portable two-inch speaker that could be positioned strategically around the office to provide a masking effect between workstations. Herman Miller’s branding of sound masking as “acoustic conditioning”, for instance, suggested that acoustics could be controlled in the same unobtrusive way as indoor climate could. Moreover, in an apparent bid to alleviate workers’ complaints about office acoustics, the generator was designed to be clearly visible in the office. It even allowed individual users to “tune” the speaker’s volume and bass/treble just “like a radio” (Herman Miller Citation1976a), extending the metaphor of tuning to the use of a dial on a media device – even if this was used to dial into the static that media users usually avoided. Like many other sound masking systems, the Herman Miller acoustic conditioner randomly modulated the signal, to sound more natural and less monotonous. Robert Propst even commissioned a young composer to produce sample compositions which could help “domesticate” its “white noise” into an “attractive aesthetic experience” similar to that of background music.Footnote5

Most sound conditioners that were patented and appeared on the market in the 1970s and 1980s, however, were designed as connected systems of speakers (often including paging or music distribution) and typically integrated inconspicuously in the plenum above the ceiling board (along with other office infrastructure such as HVAC and electrics) or hidden in light fixtures. In contrast to Herman Miller’s initial marketing strategy, masking sound was soon considered to be most effective when it was spatially and temporally uniform, such that listeners could not point to a source, be it real or perceived (Harris et al. Citation1981, 60–61). An absence or increase in masking sound could, after all, call attention to its presence and thus to masking sounds as a disturbance in itself. So that their exact location was less easily determined, speakers were designed to distribute masking sound non-directionally. Moreover, their placement and tuning had to be adjusted such that, as workers moved across the floor between stations, bathrooms and hallways, they were met by a smooth and indiscernible progression of sounds levels (Shumake Citation1992). More advanced systems even enabled variable sound levels and frequency spectra throughout the day to cover peaks in office activity. This conserved energy but also ensured that office workers would not notice a sharp difference at the end of the day (Chanaud Citation1976). For acoustical consultant David Harris and his collaborators, the masking system was to be considered an element of the office’s acoustics; never to be turned off or muted (Citation1981). To ensure its constant operation for 365 days a year, he advised that controls of masking system be placed in a locked cabinet. In this way, acoustics became a highly architectonic element; not just a way of defining architectural space, but even a semi-permanent part of the office architecture itself.

Noise masking alleviated some of the most conspicuous acoustical effects of the open-plan office. But environmental designers also found that it was hardly a catch-all solution. Although sound masking systems were frequently advertised as out-of-the-box solutions for noisy offices, achieving unobtrusive and effective sound masking typically involved an intricate process. It required, so office planners and acoustical consultants insisted, specific expertise to adjust its placement and spectra to each individual acoustical context, including its architectural features, layout, ceilings, carpeting and panelling, all of which could block, attenuate, transmit or shadow sounds in different ways. Especially if acoustics had been neglected in planning, sound conditioning could become a costly process of trial-and-error.

Moreover, the needs and sensitivities of individual office workers for acoustic privacy and disturbance naturally differed from the “idealised” average listener that intelligibility models had implied and that standardised systems of sound masking usually allowed for. Typically, reporting in specialised trade magazines and popular press seemed to evidence the premise of sound masking, regularly finding employees even unaware of its operation in the workplace. The “imperceptibility” of sound masking was a common trope in popular reporting on the technology. But occasionally, such reports did suggest that employees also differed in their acoustic sensitivity. One reporter, for instance, found that within the same organisation and building, one division of system analysts petitioned management to disable the sound masking system because they found it too distracting to think with, while employees on other floors were unaware of its operation at all (Parry Citation1972).

Acoustical consultants were aware of these perceptual differences, but typically explained them as a product of human psychology and prejudice against the principle of adding more noise to reduce noise or resistance against the suggestion that sound masking manipulated workers’ experience (Aschenbach Citation1984; Hill Citation1984). Such concerns tied into growing fears about the health and safety risks that were associated with the introduction of automation and information technologies in the office environment in the late 1970s and through the 1980s. These ranged from allegedly harmful environmental factors (such as the fluorescent light and possible radiation emitted by video display units, chemical pollutants wafting from furniture and carpets, ill-fitting chairs and keyboards designs forcing repetitive strain injuries) to social stressors, such as boredom or job insecurity as a result of work organisation (Makower Citation1981; Murphy Citation2006; Stadler Citation2017). In that same vein, some office employees blamed sound masking for headaches, irritability, malaise and other psychological problems (Aschenbach Citation1984). But since office noise was itself considered an important stressor and a major cause of employee turnover and inefficiency, such complaints tended to be drowned out by the vocal support of employees, acousticians and office designers.

In subsequent decades, sound masking became a standard application in office planning. This is clear, among others, from its continued presence in office planning handbooks and trade magazines, as well as the variety of sound management solutions that office furniture manufacturers and acoustic consultancies continued to offer well into the new millennium (Aronoff Citation1995; Marmot Citation2000). Herman Miller, for instance, founded the subsidiary Sonare Technologies specifically to develop and market products for sound and privacy management (Herman Miller Citation2005). In the early 2000s, it launched Babble, a small unit that camouflaged telephone conversations with the speaker’s own but unintelligibly scrambled voice. Herman Miller’s competitor Steelcase, likewise, commercialised Confidante, a system of self-contained units that allowed each user to adjust sound masking volume to their needs.

Both firms employed acoustic technology that had been developed by Cambridge Sound Management Inc., which had been founded in the late 1990s by an acoustic consultant at Bolt Beranek and Newman and with collaborators who had been directly instrumental to the development of sound masking technologies in the late 1970s (Cambridge Sound Management Citation2017). Among others, the firm developed more refined “pink noise” that better matched the spectrum of the human voice, by eliminating the low and high frequencies in white noise. While Herman Miller has since relegated its acoustic management activities, and sound masking is now primarily offered by specialised firms such as Cambridge Sound Management Inc. and several competitors whose client lists suggest not just the ubiquity and persistence of sound masking infrastructure in the open-plan office but also a variety of new settings where open-plan designs are applied such as in conferences, hotels, healthcare and customer services (ibid.).

Architectonics of public space

Even though it was hardly effective for all employees, planners, designers and facility managers in the 1970s and 1980s widely endorsed sound masking as part of a comprehensive acoustic management to offset the critique raised against the open-plan office. On the one hand, sound masking could be seen as a genuine attempt to ensure workers’ satisfaction and welfare at work, albeit within the frame of the open-plan office. Its introduction coincided with a renewed interest in the quality of working life and conditions in the early 1970s by labour organisations, government and trade unions, which ranged from the physical working environment to protection against hazards to social benefits (Delamotte and Walker Citation1976). This push for a more “humane” work environment focused particularly on working conditions in the industrial sectors. But in promoting a social and physical environment that reflected human relations’ ideals of a progressive and egalitarian work culture, the Herman Miller corporation projected similar ideas onto the office. Sound masking could be seen as an attempt to preserve those progressive ideals well into the 1970s and 1980s.

On the other hand, Sterne’s notion of “perceptual technics” also alerts us to the ways in which psycho-acoustic models of intelligibility and sound masking technology served to economise the so-called “channel capacity” of the office as, in Propst’s term, a self-regulating information circuit. In specifying how much enclosure an individual needs in order to feel comfortable, how much noise an office worker can tolerate while doing their job, or at what point their speech becomes inaudible to by-standers, it has helped to define a set of thresholds that could be used to modulate this circuit. I propose that it did this in two ways that have made sound masking integral to the architectonics of the office.

The first is that it has contributed to economise the use of space (and thus economised its cost too). In spite of its developers’ progressive ideals and much to Propst’s own dismay, by the mid-1970s, Action Office 2 sales focused especially on the bottom line, with staff instructed to highlight how it reduced the office’s surface value and cost per employee (in terms of lease, construction, maintenance costs).Footnote6 Against the background of an economic recession, many organisations tended to use the open plan in exactly this way (Kaufman-Buhler Citation2016). While the open-plan office had been conceived as a landscape of generously spaced and distributed workstations, by the late 1970s and 1980s, the drive for economy of space led organisations to seat workers in tight geometric rows of semi-enclosed workstations. In the 1980s and 1990s, this so-called “cubicle” would be a default in office infrastructure for lower-level clerical workers. That such workers could be seated at increasingly close range, was due in part to a perceptual technic that afforded ways of carving out spaces that were perceived as “just private enough”.

The second way in which sound masking promised to economise channel capacity is by maximising workers’ continued availability for information exchange. Rather than allowing workers to retreat in a private, personal space, sound masking carved out an acoustic territory for the worker. In that sense, it is decidedly different from other contemporary technologies for individualised and private listening, such as the headphone. As Weber (Citation2010) has shown, for instance, in the 1970s and 1980s, the headphone was redefined from a specialised, professional application to a consumer technology for achieving an intimate, personal acoustic space – especially in close quarters of the family home or urban space. But exactly because it provided the listener with an enhanced control over their personal space and availability to others, in this period, the “acoustic cocoon” of headphone listening was also widely criticised as antisocial and detached (Weber Citation2010). The analogy is instructive here. Sound masking promised a more private and concentrated experience. But by externalising its acoustic control as part of the office infrastructure rather than to individuals themselves, it maintained – at least in principle – listeners’ ongoing availability for participation in the office’s social environment.

In so bringing the informatic ideals and acoustic experiences of the open-plan office concept more in accordance, sound masking may help to explain the open-office concept’s continued persistence up to this day – albeit in very different forms: from Action Office 2 to the cubicle farm and, more recently, the radically partition-less workspaces of Silicon Valley. At the same time, the notion of perceptual technic affords insight in why acoustical concerns, too, have continued to persist. First, because sound masking’s solutions were based on highly idealised perceptual thresholds. As such, they perpetuated many of the assumptions underlying the studies of listening that these threshold criteria were based on – assumptions about what kind of work was worthwhile, what information to focus on and what to discard as distraction, or how to value workers’ own sense of comfort at work. As a product of aggregate and universalised listening preferences and tolerances, moreover, such thresholds never coincided with the experience of all listeners in the office. But as perceptual criteria that were naturalised in noise criterion curves, black-boxed in building codes or hidden from view as semi-permanent architectonic elements, they also tended to become fixed and unresponsive to changing needs in the office. This has allowed them to blend nearly indistinguishably with the built environment, and shape the experience of its inhabitants. But it has also turned them at odds with the flexibility and change that was projected to characterise working life within this environment. By changing spatial layouts in the office, by repeated attempts to maximise occupation levels or by continually changing expectations and ways of working, not only office environments have been pushed to its limits. So have these idealised thresholds and the people they represented.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joeri Bruyninckx

Joeri Bruyninckx is assistant professor in science and technology studies at Maastricht University’s Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences (the Netherlands). He is author of Listening in the Field. Recording and the Science of Birdsong (MIT Press). His current project investigates the interplay of ergonomic science, design, and use in shaping today’s office environments.

Notes

1. I borrow the term “workscape” from Franklin Becker and Fritz Steele’s book (1995) Workplace by design: mapping the high-performance workscape. The authors promote the idea that the design and use of space is key to managing high-performing organisations. I use this term here to reference office planners’ conception of the workplace as a total (and multi-sensory) environment in need to be managed in detail, an idea that traces back at least to the period described here.

2. Propst, The Office, 20; Propst, “The psychology of sensory values,” BEMA Executive symposium, October 27–29, 1969. Robert L. Propst Papers, Acc. 2010.83, Drawer D8, Folder “Psychology of the sensory value-bema”, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford, Dearborn, MI.

3. n.a. Memo, “Action Office 2 Listings April 1973”, Folder AO69, Herman Miller Corporate Archives, Holland, MI.

4. n.a. “Technics: Office acoustics” brochure published by Progressive Architecture, Reprint, September 1979. Pubs 7396, Herman Miller Corporate Archives, Holland, MI.

5. President’s report to HMRC board, 11/4/77, Folder 20 “Hugh dePree.” Herman Miller Corporate Archives, Holland, MI.

6. Memo ‘Financial Advantages of AO”, Folder “AO70”, Herman Miller Corporate Archives, Holland MI.

References

- Aronoff, S. 1995. Total Workplace Performance: Rethinking the Office Environment. Ottawa: WDL Publications.

- Aschenbach, J. 1984. “Turn on Pink Noise: It Quickly Seems Quieter.” The Daily Times, March 17, 14.

- Beranek, L. L. 1957. “Revised Criteria for Noise in Buildings.” Noise Control, January 3, 19–27.

- Beranek, L. 2008. Riding the Waves. A Life in Sound, Science, and Industry. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bernasconi, G., and S. Nellen, eds. 2019. Das Büro: Zur Rationalisierung des Interieurs, 1880–1960. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

- Bijsterveld, K. 2008. Mechanical Sound. Technology, Culture, and Public Problems of Noise in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Boje, A. 1971. Open-Plan Offices. Translated by Das Grossraum-Büro. London: Business Books Limited.

- Born, G., ed. 2013. Music, Sound and Space. Transformations of Public and Private Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Broadbent, D. E. 1958. “Effect of Noise on an ‘Intellectual’ Task.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 30: 824–827. doi:10.1121/1.1909779.

- Brookes, M.J. 1972. “Office Landscape: Does It Work?” Applied Ergonomics 3 (4): 226. doi:10.1016/0003-6870(72)90105-6.

- Bull, M. 2007. Sound Moves. iPod Culture and Urban Experience. London: Routledge.

- Burkeman, O. 2018. “Open-plan Office? No, Thanks, I’d Rather Get Some Work Done.” The Guardian, November 9.

- Cambridge Sound Mangement Inc. 2017. Company Profile. Cambridge: Cambridge Sound Management.

- Carson, L.D., W. R. Miles, and S. S. Stevens. 1943. “Vision, Hearing, and Aeronautical Design.” Journal of the Aeronautical Sciences 10 (4): 127–149. doi:10.2514/8.11011.

- Casey, K. 2005. “Noise Making Subjects.” PhD diss., University of California.

- Cavanaugh, W.J., W.R. Farrell, P.W. Hirtle, and B.G. Watters. 1962. “Speech Privacy in Buildings.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 34 (4): 475–492. doi:10.1121/1.1918154.

- Chanaud, R.C. 1976. “Variable and Adaptive Masking Sound Systems.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 60 (S1): 58. doi:10.1121/1.2003429.

- Clifford, C. 2021. “Google’s Plan or the Future of Work: Privacy Robots and Balloon Walls.” New York Times, April 30.

- Delamotte, Y., and K. F. Walker. 1976. “Humanization of Work and the Quality of Working Life.” International Journal of Sociology 6 (1): 8–40. doi:10.1080/15579336.1976.11769634.

- Dibben, N., and A. B. Haake. 2013. “Music and the Construction of Space in office-based Work Settings.” In Music, Sound and Space. Transformations of Public and Private Experience, edited by G. Born, 151–168. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Droumeva, M. 2021. “Soundscapes of Productivity. The Coffee-Office and the Sonic Gentrification of Work.” Resonance: The Journal of Sound and Culture 2 (3): 377–394. doi:10.1525/res.2021.2.3.377.

- Drucker, P. F. 1959. Landmarks of Tomorrow. New York: Harper.

- Dunlap and Associates. 1963. Physiological and Psychological Effects of Overloading Fallout Shelters. Santa Barbara, CA: Dunlap & Associates.

- Dzubay, G. 1997. “Sound Masking for the Office Unmasked”. Sound & Communications, December 22, 34–46. Port Washington, NY.

- Farrell, W.R., and B.G. Watters. 1959. “Speech Privacy Design Analyzer.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 31: 1577.

- French, N.R., and J.C. Steinberg. 1947. “Factors Governing the Intelligibility of Speech Sounds.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 19 (90): 90–119. doi:10.1121/1.1916407.

- Fucigna, J. T. 1967. “The Ergonomics of Offices.” Ergonomics 10 (5): 589–604. doi:10.1080/00140136708930912.

- Grajeda, T. 2013. “Early Mood Music: Edison’s Phonography, American Modernity and the Instrumentalization of Listening.” In Ubiquitous Musics. The Everyday Sounds That We Don’t Always Notice, edited by Marta G. Quiunones, Anahid Kassabian, and Elena Boschi, 31–48. Surrey: Ashgate.

- Hagood, M. 2019. Hush. Media and Sonic Self-Control. Durham, PA: Duke University Press.

- Hall, E. T. 1959. A Silent Language. New York: Doubleday and Company.

- Hall, E. T. 1966. The Hidden Dimension. New York: Doubleday and Company.

- Hall, M.R., and E.T. Hall. 1975. The Fourth Dimension in Architecture: The Impact of Building on Behavior. Santa Fe, NM: Sunstone Press.

- Hamme, R., and D. Huggins. 1968. “Acoustics in the Open Plan.” Office Design, September reprint, 1–4.

- Harris, D. A., A. E. Palmer, M. S. Lewis, D. L. Munson, G. Meckler, and R. Gerdes. 1981. Planning and Designing the Office Environment. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Herman Miller Inc. 1976a. Action Office by Herman Miller: Sound Solutions for Office Privacy. Ann Arbor: Herman Miller Research Corporation.

- Herman Miller Inc. 1976b. “Acoustic Problems? Here’s a Checklist.” Ideas, August 4–14.

- Herman Miller Inc. 2005. Sound Management Sales Handbook. Zeeland, MI: Herman Miller.

- Hill, B. 1984. “Noise-piping Plan Has Office Workers Upset.” Ottawa Citizen, March 1.

- Hong, R. 2017. “Office Interiors and the Fantasy of Information Work.” Triple C 15 (2): 540–562. doi:10.31269/triplec.v15i2.763.

- Hosokawa, S. 1984. “The Walkman Effect.” Popular Music 4: 165–180. doi:10.1017/S0261143000006218.

- Hui, A. 2014. “Muzak-While-You-Work: Programming Music for Industry, 1919–1948.” Historische Anthropologie 22 (3): 364–383. doi:10.7788/ha-2014-0306.

- Jones, K. 2005. “Music in Factories: A twentieth-century Technique for Control of the Productive Self.” Social & Cultural Geography 6 (5): 723–744. doi:10.1080/14649360500258229.

- Kaufman-Buhler, J. 2016. “Progressive Partitions. The Promises and Problems of the American Open Plan Office.” Design and Culture 8 (2): 205–233. doi:10.1080/17547075.2016.1189308.

- Kaufmann-Buhler, J. 2021. Open-Plan. A Design History of the American Office. London: Bloomsbury.

- Knoblauch, J. 2020. The Architecture of Good Behavior. Psychology and Modern Institutional Design in Postwar America. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Korczynski, M., M. Pickering, and E. Robertson. 2013. Rhythms of Labour. Music at Work in Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kryter, K. D. 1950. “The Effects of Noise on Man.” Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, Monograph Supplement 1: 1–95.

- Kryter, K.D. 1962. “Methods for the Calculation and Use of the Articulation Index.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 34 (11): 1689–1697. doi:10.1121/1.1909094.

- Levine, N. 2017. “The Nature of the Glut: Information Overload in Postwar America.” History of the Human Sciences 30: 32–49. doi:10.1177/0952695116686016.

- Lewis, P. T., and P.E. O’Sullivan. 1974. “Acoustic Privacy in Office Design.” Journal of Architectural Research 3 (1): 48–51.

- Makower, J. 1981. Office Hazards: How Your Job Can Make You Sick. Washington, DC: Tilden Press.

- Mansell, J. G. 2017. The Age of Noise in Britain. Hearing Modernity. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Marmot, A. 2000. Office Space Planning. Designing for Tomorrow’s Workplace. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Martin, R. 2019. “Acoustic Tile.” In The Oxford Handbook of Media, Technology, and Organization Studies, edited by T. Beyes, R. Holt, and C. Pias, 15–25. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McGregor, D. 1960. The Human Side of Enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Murphy, M. 2006. Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty. Environmental Politics, Technoscience, and Women Workers. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Parry, D. 1972. “Be Quiet! Make a Little Noise.” Montreal Gazette, September 1, n.p.

- Perry, P. 2022. “I Can’t Face Going Back to Work in the Office.” The Guardian, March 20.

- Picker, J. M. 2003. Victorian Soundscapes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Plourde, L. 2017. “Sonic air-conditioning: Muzak as Affect Management for Office Workers in Japan.” The Senses & Society 12 (1): 18–34. doi:10.1080/17458927.2017.1268812.

- Propst, R. L. 1968. The Office. A Facility Based on Change. Ann Arbor: Herman Miller Research Corporation.

- Propst, R. L., and M. Wodka. 1975. The Action Office Acoustic Handbook. Ann Arbor, MI: Herman Miller Research Corporation.

- Riland, L. H. 1970. “Summary: A Survey of Employee Reactions to the Landscape Environment One Year after Initial Occupation.” Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak, March.

- Ris, V. 2021. “The Environmentalization of Space and Listening. An Archaeology of noise-cancelling Headphones and Spotify’s Concentration Playlists.” Sound Effects. An Interdisciplinary Journal of Sound and Sound Experience 10 (1): 158–172. doi:10.7146/se.v10i1.124204.

- Rumpfhuber, A. 2013. Architektur immaterieller Arbeit. Vienna: Verlag Turia + Kant.

- Sachs, A. 2018. Environmental Design. Architecture, Politics, and Science in Postwar America. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

- Schwartz, H. 2002. “Techno-Territories: The Spatial, Technological and Social Reorganization of Office Work.” PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Shumake, M. G. 1992. Increasing Productivity and Profit in the Workplace: A Guide to Office Planning and Design. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Somaiya, R. 2008. “Noises off.” The Guardian, October 23.

- Sommer, R. 1966. “Man’s Proximate Environment.” Journal of Social Issues 12 (4): 59–70. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1966.tb00549.x.

- Sommer, R. 1969. Personal Space. The Behavioral Basis of Design. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall .

- Stadler, M. 2017. “Man Not a Machine: Models, Minds, and Mental Labor, C. 1980.” Progress in Brain Research 223: 73–100.

- Sterne, J. 1997. “Sounds like the Mall of America: Programmed Music and the Architectonics of Commercial Space.” Ethnomusicology 41 (1): 22–50. doi:10.2307/852577.

- Sterne, J. 2012. MP3: The Meaning of a Format. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Tett, G. 2021. “The Empty Office: What We Lose When We Work from Home.” The Guardian, June 3.

- Thompson, E. 2002. The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900–1930. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Touloumi, O. 2014. “Architectures of Global Communication: Psychoacoustics, Acoustic Space, and the Total Environment, 1941–1970.” PhD diss., Harvard University.

- Waller, R.A. 1969. “Office Acoustics. Effect of Background Noise.” Applied Acoustics 2: 121–130. doi:10.1016/0003-682X(69)90014-0.

- Weber, H. 2010. “Head Cocoons. A Sensori-Social History of Earphone Use in West Germany, 1950–2010.” The Senses & Society 5 (3): 339–363. doi:10.2752/174589210X12753842356089.

- Wittje, R. 2016. The Age of Electroacoustics. Transforming Science and Sound. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.