ABSTRACT

Objective

This study aimed to 1) investigate the psychometric properties of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale or CCAS (Clayton & Karazsia, 2020) and 2) examine the mediating role of climate change anxiety on the link between experience of climate change and behavioural engagement in climate mitigation in Filipino youth.

Method

A total of 452 Filipino adolescents responded to the survey (Mean Age = 19.18, SD = .99).

Results

A modified two-factor model of the CCAS displayed superior fit relative to the other three models tested. Confirmatory factor analysis in Phase 1 yielded a stable two-factor structure with strong factor loadings and good internal consistency. In Phase 2, cognitive-emotional, but not the functional impairment component of climate anxiety, showed a mediating effect on the relationship between experience of climate change and behavioural engagement in climate mitigation.

Conclusions

This study is the first to demonstrate that CCAS subscales have distinct mediating roles in linking Filipino adolescents’ experience of climate change and mitigation behaviours. Further validation of the CCAS is recommended, as well as further research on the factors that can promote environment-friendly behaviours in Filipino youth.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

(1) Only two studies to date examined the psychometric properties of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale (CCAS), which both used samples from WEIRD countries.

(2) There is a dearth of studies on climate change anxiety in a non-WEIRD country such as the Philippines.

(3) Those who experienced the consequences of climate change are more likely to engage in actions that help mitigate it.

What this topic adds:

(1) As a psychometrically sound tool, the Climate Change Anxiety Scale can be used to measure climate anxiety in Filipino youth.

(2) Psychologists should be prepared to address the negative impacts of the climate crisis on youth mental health.

(3) The study provides meaningful insights that can be used in educating the younger generations in mitigating climate change.

The United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and leading world scientists recommended elevating the status of climate change to a climate crisis (McGrath, Citation2021; Ripple et al., Citation2020). The climate crisis has become a serious threat to individual well-being and survival, and research indicates that humans are the ones warming the planet resulting to adverse consequences (Friedlingstein et al., Citation2019). While acknowledgement of the climate crisis can urge aggressive climate change mitigation (Ripple et al., Citation2020), this could also have a strong emotional impact on people most affected. Despite the Philippines being one of the countries most vulnerable to the brunt of climate change due to its geographical location and limited economic capacity (BusinessWorld, Citation2021), studies that examine climate change anxiety, especially among the youth, are rather scarce. The first objective of this study is to examine the psychometric properties of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale (CCAS: Clayton & Karazsia, Citation2020) in Filipino youth. It is important to establish a psychometrically sound tool that can assess the climate change anxiety among youth from a country that is part of the Global South (low- and middle-income countries or the majority world), given that they are the ones most likely to experience the impacts of climate change in the near future (The Center for Effective Global Action, Citation2020). The second aim of the current study is to investigate the mediating role of climate change anxiety in the link between personal experience of climate change consequences and mitigation actions. The current paper is organised as follows. In the next section, we discuss the validity findings of CCAS and the basis for examining its structural validity in Filipino youth. Next, we describe our mediation hypothesis characterising climate change anxiety as a psychological mechanism that links the personal experience of climate change and engagement in mitigation behaviours. We then report our findings and provide implications for mitigation actions in climate-vulnerable countries like the Philippines.

The climate crisis’ impact on the youth and validation of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale

The climate crisis is imposing a huge psychological burden on the youth, as they continue to be exposed to climate-related disasters and to anticipate harsher consequences brought about by the changing climate (Sanson & Bellemo, Citation2021). Despite having been predominantly caused by the past and current generations of adults, the worst impacts of the climate crisis will likely be felt and absorbed by today’s young people who are the future adults (Sanson et al., Citation2018). With the realisation that urgent climate action is needed, young people face immense pressure to secure their future. On the one hand, heightened awareness of the reality of the climate crisis can make the youth feel more motivated to engage in climate change mitigation behaviours, but on the other hand, this hypervigilance could potentially have an adverse impact on their psychological health.

Emerging evidence for the potential impacts of the climate crisis on mental health (Ogunbode et al., Citation2021; Palinkas & Wong, Citation2020) necessitates the use of a tool that could measure climate change anxiety. To date, there are only two studies that examined the psychometric properties of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale (CCAS) using American (Clayton & Karazsia, Citation2020) and German samples (Wullenkord et al., Citation2021). While the CCAS had been used to examine the relationship between climate change anxiety and mental health among Gen Z Filipinos, the authors did not attempt to validate the scale in their sample (Reyes et al., Citation2021). In the initial validation of the CCAS, climate change anxiety was structured as a bidimensional construct with two higher-order dimensions of cognitive-emotional impairment and functional impairment, both of which they found to be related to the experience of climate change and to negative emotions (Clayton & Karazsia, Citation2020). The authors developed the items based on existing literature and blogs that address emotional responses to climate change. They also selected items from clinically relevant tools that measure impaired functioning. Cognitive-emotional impairment assesses if people were thinking about climate change to an unhealthy extent, while functional impairment checks whether the emotions related to climate change interfered with people’s capacity to function. Validation of the translated version of CCAS on German samples did not find evidence for Clayton and Karazsia (Citation2020) proposed two-factor structure. This inconsistency puts forth a need to further test the structural validity of the CCAS and its relationship to other variables. The current study compared one-factor and two-factor models of the CCAS, hypothesising that the latter would demonstrate superior fit relative to the one-factor solution. The study offers compelling reasons for the need to examine the CCAS in using Philippine samples. The current literature on climate change anxiety is dominated by samples drawn from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) countries (Clayton & Karazsia, Citation2020; Wullenkord et al., Citation2021) despite the climate crisis being not only a WEIRD problem. Given the global nature of the climate crisis (Patz, Citation2016) and the known cultural differences on how people experience anxiety (Hofmann & Hinton, Citation2014), examining the psychometric properties of the CCAS in a non-WEIRD sample is important. Moreover, the current study responded to the recommendation of the original authors of CCAS (i.e., Clayton & Karazsia, Citation2020) to examine climate change anxiety in under-represented samples. To our knowledge, there is no study yet to date that validates the measure from a non-WEIRD country such as the Philippines.

Experience of climate change, climate anxiety and engagement in mitigation

Studies showed that those who experience the consequences of climate change (e.g., extreme weather and other effects of global warming) had greater intention to engage in sustainable actions (Bollettino et al., Citation2020; Broomell et al., Citation2015; Demski et al., Citation2017). Evidence from the Philippines suggests that 71.7% of Filipino respondents from a nationally representative sample believed that their experiences with disasters, including extreme weather disasters, were due to or somewhat due to climate change (Bollettino et al., Citation2020). Prior experience of climate change was found to be related to psychological distress, and psychological distress was in turn linked to behavioural engagement in climate mitigation (Reser et al., Citation2012). In this paper, we propose that Filipino youth who experience the consequences of climate change (e.g., extreme typhoons and drought) are more likely to engage in actions that help mitigate it (e.g., saving energy, recycling, etc.). This argument is based on the proposition of Construal Level Theory (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010), which emphasised that people’s behaviour can be motivated by the extent to which they perceive events as abstract or concrete. An abstract perception involves perceiving threats as psychologically distant or more likely to happen in the far future (temporal distance), less likely to be experienced by individuals like themselves (social distance) and unlikely to happen in their place of residence or local community (geographical distance). On the other hand, a concrete perception reflects people’s tendency to perceive threats as psychologically proximal or likely to happen today or in the near future (temporally proximal), among people like themselves (socially proximal) and likely to happen in their local residence or community (geographically proximal). This proposition is supported by results of a systematic review that demonstrated how people have an increased propensity to perform pro-environmental behaviours when it is construed as more proximal and concrete within the construct of psychological distance (Maiella et al., Citation2020). We aim to add to the literature by providing evidence on the role of climate change anxiety in the relationship between psychological distance (experience of climate change) and mitigation actions. Given the notable consequences of climate change on mental health in previous disasters that occurred in the Philippines (Nalipay et al., Citation2015), it is logical to propose that climate anxiety could also be a negative emotional consequence that results from personal experience of climate change. We reason that, climate change anxiety, as people’s emotional response to extreme weather events caused by climate change, can motivate them to engage in climate mitigation behaviours. As literature suggests that climate change anxiety is strongly related to pro-environmental outcomes (Wullenkord et al., Citation2021) and that heightened worry about the impacts of climate change increases the tendency to engage in mitigation behaviour (Urban et al., Citation2021), we believe that testing the mediating effects of climate change anxiety between Filipino youth’s experience of extreme weather events and their engagement in mitigation actions to reduce climate change fills an important gap in the literature.

Study objectives and hypotheses

This study aimed to 1) investigate the psychometric properties of the CCAS (Clayton & Karazsia, Citation2020) and 2) examine the mediating role of climate change anxiety on the link between experience of climate change and behavioural engagement in climate mitigation among Filipino adolescents. To address these objectives, this research implemented two phases. Phase 1 validated the CCAS (Clayton & Karazsia, Citation2020), while Phase 2 tested the mediating effect of the two dimensions of climate change anxiety (cognitive-emotional impairment and functional impairment) on the relationship between experience of climate change and behavioural engagement in climate mitigation. Examining the mediating effects of the two components of CCAS separately comes with the acknowledgement that they could display differential relations with experience of climate change and behavioural engagement in climate mitigation. Below, we present the current study’s hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: The two-factor structure of the CCAS will display superior fit relative to the one-factor model.

Hypothesis 2: Experience of climate change will positively and significantly predict Filipino adolescents’ behavioural engagement in climate mitigation.

Hypothesis 3: Cognitive-emotional impairment will significantly mediate the relationship between experience of climate change and behavioural engagement in climate mitigation among Filipino adolescents.

Hypothesis 4: Functional impairment will significantly mediate the relationship between experience of climate change and behavioural engagement in climate mitigation among Filipino adolescents.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were 452 Filipino adolescents who are undergraduate students in a private university in Manila, the Philippines (mean age = 19.18, SD = .99). Participants were recruited through announcements in online classes and email messages which contained relevant details about the study and the survey link. They were informed that their responses will be confidential and anonymous, and that they have the right to withdraw from participation any time. After securing their consent, the participants were directed to the online page with survey questions. Participants were given course credits for their participation. The study followed guidelines from the American Psychological Association, the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Instruments

Participants were given English versions of all the instruments. They were instructed to read each item and respond accordingly. They were assumed to have adequate comprehension of the language as it is the primary medium of instruction in the Philippines (Rafael, Citation2015). Participants responded to 5-point Likert scales representing frequency (1 = never to 5 = almost always). presents all items of the three measures used in this study.

Table 1. Survey items

Climate change anxiety scale

The 13-item Climate Change Anxiety scale (CCAS) by Clayton and Karazsia (Citation2020) was used. It measures two subscales of climate change anxiety, namely: cognitive-emotional impairment which is comprised of eight items and functional impairment which has four items. Both factors have exhibited good internal consistency in this study with Cronbach's alpha coefficients of .90 and .85, respectively. The overall reliability of the scale is .92.

Experience of climate change

Three-items measuring participants’ experience of climate change (ECC) were included. A sample item includes “I have been directly affected by climate change”. The items showed adequate internal consistency (α = .79). All three items are presented in .

Behavioural engagement in climate mitigation

Six behavioural engagement items were included in the study. Clayton and Karazsia (Citation2020) adapted these questions from Drive for Muscularity Scale to assess participant’s behavioural engagement related to sustainability. A sample item from this set is “I recycle”. In the current study, the scale showed an internal consistency of .67.

Data analysis

Phase 1

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) through maximum likelihood estimation was used to examine four competing models of CCAS among Filipino adolescents: one-factor model without modifications, one-factor model with modifications, two-factor model without modifications and two-factor model with modifications. The following fit indices were employed: the model chi-square, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, Citation1992), comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, Citation1990), standardised root mean square residual or (S)RMR and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). Cut-off scores by Hu and Bentler (Citation1998) were applied in determining model fit. To test the convergent and discriminant validity of the CCAS subscales, computations of composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), maximum shared variance (MSV) and square root of AVE were used.

Phase 2

Descriptive statistics and correlations were computed. To determine the mediating role of cognitive-emotional impairment and functional impairment on the experience of climate change to behavioural engagement in climate mitigation, mediation analysis was initially conducted through structural equation modelling (SEM). SEM provides data model fit for the hypothesised mediation model, thereby making a strong case for the plausibility of the causality assumptions (Gunzler et al., Citation2013). However, employing SEM to test the hypothesised model resulted in poor fit: CFI = .44, TLI = −2.38, Bayesian (BIC) = 7656.02, RMSEA = .81 and SRMR = .20.

As an alternative, mediation analysis using Model 6 of Hayes’ PROCESS macro for SPSS was performed on 5,000 bootstrap samples (Hayes, Citation2018; Hayes, Citation2013). This model made it possible to test the mediating effect of the two subscales of the CCAS separately. The use of PROCESS was deemed sufficient in testing the mediation given the current study’s huge enough sample (N = 452). Our sample size made it ideal to apply bootstrapping, as the accuracy of the parameter estimates increases and the bootstrapping empirical distribution is better able to represent the true underlying distribution of the population under examination with increasing sample size (Ratick & Schwarz, Citation2009).

Results

Phase 1

Structural validity of the CCAS

Models 1 and 2 were structured as a single-factor model representing an overall climate anxiety factor, with Model 2 permitting correlated error residuals on four pairs of items (1 and 2, 5 and 6, 6 and 8, 11 and 12). Model 1 yielded poor fit, while Model 2 showed adequate fit. Models 3 and 4, on the other hand, represented a two-factor model characterising correlated two-factors including cognitive-emotional and functional impairment subscales, with Model 4 allowing correlated errors on the same four pairs of items. CFA results showed that Model 3 has suboptimal model fit. Model 4 yielded an adequate data-model fit with strong factor loadings. Its fit indices are also superior to those of Model 2. Hence, we conclude that Model 4 or the modified two-factor solution of the CCAS is the best fitting model of climate change anxiety in adolescent Filipinos, confirming Hypothesis 1. presents fit indices of the four models of CCAS tested in this study.

Table 2. Fit indices of CFA (comparison of four models of CCAS)

All items loaded substantially to their respective factors ( shows the factor loadings of CCAS’ items in all four models tested). Items on both subscales also demonstrated high internal consistency, .90 for the cognitive-emotional component and .85 for the functional component. The overall Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the CCAS is .92.

Table 3. Standardised factor loadings of CCAS items (per model)

Convergent and discriminant validity of the CCAS

With evidence for the two-factor structure of the CCAS, we then assessed the convergent and discriminant validity of the subscales. The relevant results are displayed in . Both subscales displayed convergent validity based on computations of composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). Results showed that the CR of the two subscales is greater than .70. To examine convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) should be above .50 and the CR should be more than the corresponding AVE (Hair et al., Citation2010). Both subscales met these criteria. On the other hand, analysis failed to find evidence for discriminant validity, since the maximum shared variance (MSV) must be less than the corresponding AVE, and the square root of AVE should be greater than the related correlations (Hair et al., Citation2010). As shows, the two subscales did not meet the criteria for discriminant validity.

Table 4. Convergent and discriminant validity statistics of the CCAS subscales

Phase 2

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Descriptive statistics and correlations between the variables are shown in . All variables are positively and significantly correlated, with cognitive-emotional impairment and functional impairment showing the strongest correlation with each other. On the other hand, functional impairment displayed the weakest correlation with behavioural engagement in climate mitigation.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Mediation analysis

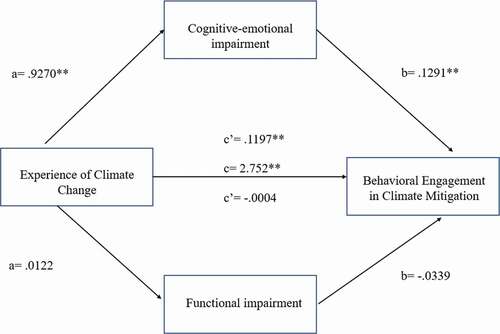

After performing Model 6 mediation analysis on 5000 bootstrap samples using PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, Citation2018; Hayes, Citation2013), a direct effect of experience of climate change on behavioural engagement in climate mitigation was found, confirming Hypothesis 2. Results also showed a mediating effect of the cognitive-emotional impairment component of climate change anxiety on the relationship between experience of climate change and behavioural engagement in climate mitigation (confirming Hypothesis 3), while the mediating effect of the functional impairment component was non-significant (inconsistent with Hypothesis 4). Taken together, the results lend support for Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 but not Hypothesis 4. See, for the Phase 2 results. illustrates the relationships between the variables.

Table 6. Mediation results

Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the psychometric properties of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale (Clayton & Karazsia, Citation2020) including its structural, convergent, and discriminant validity and reliability among adolescents from the Philippines. Moreover, we investigated the mediating role of cognitive-emotional and functional impairment subscales of the CCAS on the association between experience of climate change and behavioural engagement in climate mitigation. Overall, the findings confirmed the modified two-factor solution for CCAS with internally consistent items, convergent validity, but no support was found for its discriminant validity. Results of the mediation analysis showed that CCAS subscales (cognitive-emotional and functional impairment) have distinct mediating effects on the experience of climate change and mitigation behaviour link. Specifically, we found that the cognitive-emotional, but not the functional impairment subscale, mediated the positive influence of experience of climate change on behavioural engagement in climate mitigation. We discussed these findings in further detail below.

Validity findings of the CCAS

We used CFA to examine four competing models of CCAS among Filipino adolescents. Models 1 and 2 were structured as a single-factor model representing an overall climate anxiety factor, with Model 2 permitting correlated error residuals. Model 1 yielded poor fit, while Model 2 showed adequate fit. Models 3 and 4 represented a two-factor model characterising correlated two-factors including cognitive-emotional and functional impairment subscales, with Model 4 allowing correlated errors. CFA results showed that Model 3 has suboptimal model fit. Model 4 yielded an adequate data-model fit with strong factor loadings and superior fit indices relative to Model 2. Hence, we conclude that Model 4 or the modified two-factor solution of the CCAS is the best fitting model of climate change anxiety in adolescent Filipinos, confirming Hypothesis 1. All items loaded substantially to their respective factor, indicating that the items are valid for measuring the cognitive-emotional and functional impairment factors of climate change anxiety in Filipino adolescents. Further, we found high reliability across all items in both subscales indicating that the CCAS items have high internal consistency. The two-factor model verified in the CCAS substantiated the conceptualisation of climate change anxiety which was originally forwarded by Clayton and Karazsia (Citation2020). To our knowledge, there are only two studies that examined the psychometric properties of CCAS using American (Clayton & Karazsia, Citation2020) and German samples (Wullenkord et al., Citation2021). The present findings contributed to the dearth of studies on the psychometric properties of CCAS by investigating its validity and reliability using a non-WEIRD and under-represented sample from the Philippines. We found evidence for convergent but not discriminant validity of the CCAS. Convergent validity implies that items of the scales are internally consistent and that the observed variables represent the construct well. On the other hand, lack of evidence for discriminant validity raises the possibility that the strength of the relationships found could be overestimated, since it implies that the latent constructs could have an influence on the variation of more than just the observed variables to which they are theoretically related (Farell, Citation2010). Farrell suggested to combine constructs into one overall measure to address discriminant validity issues (Farell, Citation2010), but as we would later on show in this paper, the distinct mediating effects of the two subscales of CCAS justify their differentiation in this study. Perhaps, given the huge shared variance between the cognitive-emotional and functional impairment subscales (as implied by insufficient discriminant validity), future studies can test the possibility of a bifactor model of the CCAS.

Experience of climate change leads to mitigation efforts

Our findings lend support for Hypothesis 2 by demonstrating that experience of climate change consequences positively and significantly predicted engagement in mitigating behaviours. In other words, Filipino adolescents who experienced the consequences of climate change (e.g., extreme typhoons and drought) are more likely to engage in actions that help mitigate climate change (e.g., saving energy, planting trees, etc.), confirming past studies (Bollettino et al., Citation2020; Broomell et al., Citation2015; Demski et al., Citation2017; Wullenkord et al., Citation2021). For instance, previous research showed that UK adults who experience the consequences of climate change such as extreme weather reported greater intention to sustainable actions (Demski et al., Citation2017). The same pattern was found across 24 countries, with people who experience the consequences of global warming showed stronger intentions to engage in mitigating actions (Broomell et al., Citation2015). Evidence from the Philippines showed that Filipinos who face a greater risk from climate consequences engage in actions that mitigate the climate crisis and prepare for future disasters (Bollettino et al., Citation2020). This finding supported the proposition of Construal Level Theory (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010) by elucidating that personal experience of climate change consequences can motivate mitigation behaviours among the Filipino youth. Personally experiencing the consequences of climate change may have led Filipino youth to perceive threats of extreme weather events as proximal, compelling them to act to mitigate its future effects.

Climate change anxiety as a psychological mechanism

Providing support for Hypothesis 3, our findings showed that cognitive-emotional partially mediated the positive influence of experience of climate change on engagement in climate change mitigation among Filipino adolescents. This suggests that individuals who experience the consequences of climate change tend to experience higher levels of worrying and negative emotions about the climate crisis, which in turn motivates them to engage in behaviours that help mitigate climate change. Evolutionary psychology explained that emotions are adaptive mechanisms that help humans to respond to threats (Tooby & Cosmides, Citation2008). Anxiety, in particular, is an adaptive default emotion that signals the presence of threats and uncertainty, allowing one to act to avoid the impending danger (Brosschot et al., Citation2016; Buss, Citation1990). Affect heuristic explains how emotions as heuristic influence an individual’s decision-making and pro-environmental behaviour based on previous experience (Pachur et al., Citation2012). We explain that Filipino adolescents’ emotional responses to extreme weather events may have heightened their perception of vulnerability to and risks from the present and future consequences of the climate crisis. Consequently, this can encourage them to personally act to mitigate climate change.

However, our findings did not find support for Hypothesis 4, as functional impairment did not mediate the positive experience of climate change and engagement in climate change mitigation among Filipino adolescents. Specifically, the indirect effect of functional impairment in the experience of climate change and mitigation behaviours link was not significant. In other words, Filipino adolescents may engage in behaviours that mitigate climate change regardless of impairment associated with worrying about climate change. A possible explanation is that Filipino adolescents’ worries about climate change might not be high enough to cause functional impairment, as previous research has noted (see Clayton & Karazsia, Citation2020). We note that this finding merits further investigation.

Taken together, the present findings contribute to the literature in several ways. First, this study was the first to examine the psychometric properties of CCAS in an under-represented, non-WEIRD and highly climate-vulnerable country such as the Philippines. Specifically, our findings yielded that the two-factor solution of CCAS is a psychometrically sound tool for assessing climate anxiety in Filipino adolescents. Investigating climate anxiety in the Philippines is valuable as it is one of the countries in the world that constantly faces the devastating consequences of climate change. For instance, the country faces at least 20 cyclones per year (Asian Disaster Reduction Center, Citation2021), several of which are supertyphoons (e.g., Haiyan) that cause extreme damages to the lives and livelihood of Filipinos. Second, the current research focused on adolescents who will face the future consequences of the climate crisis. Our findings indicate that adolescent Filipinos can experience a certain degree of climate anxiety due to their personal exposure to extreme weather events such as typhoons and droughts. Third, our findings revealed that Filipino adolescents who experienced the brunt of the climate crisis engage in mitigation actions to reduce climate change. While the limited past research examined adaptation strategies from disasters caused by climate change (Bollettino et al., Citation2020) among Filipino adults, the current findings centred on the mitigation responses among the younger generations of Filipinos. Lastly, the present study made use of the Construal Level Theory (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010) as basis for the hypothesis that climate change anxiety can operate as an emotional mechanism that mediates the positive influence of experience of climate change on mitigation behaviours among the Filipino youth. The present study is the first to demonstrate the distinct associations of the mediator variables (cognitive-emotional and functional impairment) to Filipino adolescents’ personal experience of climate change and their mitigation behaviours. In particular, our findings indicated that cognitive-emotional, but not functional impairment, mediates the positive influence of one’s personal experience of climate change on mitigating behaviours.

Limitations and future directions

Despite its limitations, the current study offers opportunities for future research. First, given that the present study focused on adolescents, future research may consider examining the hypothesis among younger children. This is important given the emerging evidence on climate anxiety among children (Swain, Citation2020). Second, our study was conducted in one country only. Given the global nature of environmental problems (Aruta, Citation2021a; Tam & Milfont, Citation2020), future studies may consider investigating climate change anxiety and its correlations across cultures. Third, this study did not use existing measures in examining the convergent, criterion and discriminant validity of CCAS. Future research should look into how CCAS correlates with relevant measures in examining its psychometric properties in Filipinos and samples from other non-WEIRD countries. Fourth, the scale used to measure behavioural engagement in climate mitigation displayed less-than-ideal reliability in the current study; thus, we recommend that future researchers carefully choose and employ a scale whose items have better internal consistency. Fifth, the study cannot claim causal inferences on the associations among experience of climate change, climate anxiety and mitigation actions due to its cross-sectional nature. The SEM also exhibited poor fit, weakening causality assumptions. Future studies may opt for a longitudinal design or may consider testing the hypotheses in a controlled laboratory setting to establish cause-and-effect. It would be interesting to examine at what point climate change anxiety becomes maladaptive, as climate change has the potential to be a chronic stressor (Clayton, Citation2020). Lastly, the current research did not examine the role of gender in climate anxiety and mitigation behaviour. As there are gender-specific patterns in environmentalism (Aruta, Citation2021a; Chan et al., Citation2019), future studies should investigate the role of gender in climate anxiety and climate change mitigation efforts. Nonetheless, the present study provides meaningful insights that can be used in educating the younger generations in mitigating climate change and adapting from its psychological consequences.

Implications

The present study was able to demonstrate how the experience of climate change is associated with climate anxiety and engagement in mitigating actions. While this shows an apparent need to raise climate awareness to motivate engagement in sustainable behaviours, psychologists should be prepared to address the potential negative impacts of the climate crisis on youth mental and physical health (Sanson & Bellemo, Citation2021). As evidenced in this study, climate change anxiety is one consequence of experiencing climate change. Beyond learning how to adapt to such consequences, we recommend finding more avenues to promote environment-friendly behaviours among the youth.

Educational and developmental psychologists are in good positions to support and empower the youth in their pursuit to fight climate change and spur collective action. Evidence exists for how intergenerational transmission of environmental concern and green purchase intentions between Filipino parents and adolescents is possible (Aruta, Citation2021b, Citation2021c; Aruta & Paceño, Citation2021). This implies value in recognising the crucial role of parents in raising children who are socially responsible and are cognisant of their role in environmental sustainability. Parents are considered to be the first educators to children who pass on important values (Gozum & Sarmiento, Citation2021); thus, psychologists are called on to alert parents, either through open dialogue or by means of psychoeducational interventions, about this crucial role that they play in securing the future of their children and of succeeding generations.

We also recommend that stakeholders commit to coming up with curative rather than just palliative solutions to the climate crisis facing humans, and this includes educating the youth on the detrimental consequences of climate change and how they can contribute to mitigating it. One viable strategy is to target children and adolescents in their formative years (Gozum & Sarmiento, Citation2021), for instance, through educators’ use of classroom materials that aim to incite environmental concern, and through incorporating discussions of climate change and the climate crisis in the school curriculum. Beyond the classroom, there are also other avenues to promote environmental awareness. We could maximise the potential of the culture and the arts in raising awareness of these issues and support the development of active and adaptive coping skills while taking caution not to cause dysfunctional psychological distress. We also encourage stakeholders to mindfully come up with solutions that are inclusive, equitable and wide in reach, owing to the glaring socio-economic inequalities observed across and within countries (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), Citation2015). Finally, we advocate for the conduct of more local studies in different contexts so that localised, context-specific policies that take into account the role of culture in fighting climate change can be generated.

Data availability statement

The data analysed in this study can be made available upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aruta, J. J. B. R. (2021a). An extension of Theory of Planned Behavior in predicting intention to reduce plastic use in the Philippines: Cross-sectional and experimental evidence. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12504

- Aruta, J. J. B. R. (2021b). The intergenerational transmission of nature relatedness predicts green purchase intention among Filipino adolescents: Cross-age invariance and the role of social responsibility. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02087-7

- Aruta, J. J. B. R. (2021c). The differential impact of prescriptive norms in the intergenerational transmission of environmental concern in a non-Western context: Evidence from the Philippines. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12508

- Aruta, J. J. B. R., & Paceño, J. L. (2021). Social responsibility facilitates the intergenerational transmission of attitudes toward green purchasing in a non-Western country: Evidence from the Philippines. Ecopsychology. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2021.0016

- Asian Disaster Reduction Center. (2021, January 21). Information on disaster risk reduction of the member countries. https://www.adrc.asia/nationinformation.php?NationCode=608&Lang=en&NationNum=14

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

- Bollettino, V., Alcayna-Stevens, T., Sharma, M., Dy, P., Pham, P., & Vinck, P. (2020). Public perception of climate change and disaster preparedness: Evidence from the Philippines. Climate Risk Management, 30, 100250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2020.100250

- Broomell, S. B., Budescu, D. V., & Por, H. H. (2015). Personal experience with climate change predicts intentions to act. Global Environmental Change, 32, 67–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.03.001

- Brosschot, J. F., Verkuil, B., & Thayer, J. F. (2016). The default response to uncertainty and the importance of perceived safety in anxiety and stress: An evolution-theoretical perspective. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 41, 22–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.04.012

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Testing Structural Equation Models, 21(2), 136–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005

- BusinessWorld. (2021, July 5). Philippines maintains lower-middle-income status amid pandemic. https://www.bworldonline.com/philippines-maintains-lower-middle-income-status-amid-pandemic/

- Buss, D. M. (1990). The evolution of anxiety and social exclusion. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(2), 196–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.196

- The Center for Effective Global Action. (2020, November 20). Evidence to action 2020: Climate change and the Global South. CEGA. https://medium.com/center-for-effective-global-action/evidence-to-action-2020-climate-change-and-the-global-south-792b643b2ee0

- Chan, H. W., Pong, V., & Tam, K. P. (2019). Cross-national variation of gender differences in environmental concern: Testing the sociocultural hindrance hypothesis. Environment and Behavior, 51(1), 81–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517735149

- Clayton, S. & Karazsia, B.T. (2020). Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 69(June), 101434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101434

- Demski, C., Capstick, S., Pidgeon, N., Sposato, R. G., & Spence, A. (2017). Experience of extreme weather affects climate change mitigation and adaptation responses. Climatic Change, 140(2), 149–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1837-4

- Farell, A. M. (2010). Insufficient discriminant validity: A comment on Bove, Pervan, Beatty, and Shiu (2009). Journal of Business Research, 63(3), 324–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.05.003

- Friedlingstein, P., Jones, M. W., O’Sullivan, M., Andrew, R. M., Hauck, J., Peters, G. P., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Sitch, S., Le Quéré, C., Bakker, D. C. E., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Jackson, R. B., Anthoni, P., Barbero, L., Bastos, A., Bastrikov, V., Becker, M., & Zaehle, S. (2019). Global carbon budget 2019. Earth System Science Data, 11(4), 1783–1838. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000385668

- Gozum, I. E. A., & Sarmiento, P. J. D. (2021). Emphasizing the role of parents in values education to children in their formative years during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Research Studies in Education, 10(7), 35–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrse.2021.618

- Gunzler, D., Chen, T., Wu, P., & Zhang, H. (2013). Introduction to mediation analysis with structural equation modeling. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 25(6), 390–394.

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

- Hofmann, S. G., & Hinton, D. E. (2014). Cross-cultural aspects of anxiety disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 16(6), 450. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0450-3

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

- Maiella, R., La Malva, P., Marchetti, D., Pomarico, E., Di Crosta, A., Palumbo, R., Cetara, L., Di Domenico, A., & Verrocchio, M. C. (2020). The psychological distance and climate change: A systematic review on the mitigation and adaptation behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568899

- McGrath, M. (2021, August 9). Climate change: IPCC report is ‘code red for humanity’. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-58130705

- Nalipay, M. J. N., Mordeno, I. G., & Saavedra, R. L. J. (2015). Cognitive processing, PSTD symptoms, and the mediating role of posttraumatic cognitions. Philippine Journal of Psychology, 48(2), 3–26.

- Ogunbode, C. A., Pallesen, S., Böhm, G., Doran, R., Bhullar, N., Aquino, S., … & Lomas, M. J. (2021). Negative emotions about climate change are related to insomnia symptoms and mental health: Cross-sectional evidence from 25 countries. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01385-4

- Pachur, T., Hertwig, R., & Steinmann, F. (2012). How do people judge risks: Availability heuristic, affect heuristic, or both? Journal of Experimental Psychology. Applied, 18(3), 314–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028279

- Palinkas, L.A. & Wong, M. (2020). Global climate change and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 32, 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.023

- Patz, J. A. (2016). Solving the global climate crisis: The greatest health opportunity of our times? Public Health Reviews, 37(1), 30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-016-0047-y

- Rafael, V. (2015). The war of translation: Colonial education, American English, and Tagalog slang in the Philippines. The Journal of Asian Studies, 74(2), 283–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911814002241

- Ratick, S., & Schwarz, G. (2009). Monte Carlo simulation. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 175–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044910-4.00476-4

- Reser, J. P., Bradley, G. L., & Ellul, M. C. (2012). Coping with climate change: Bringing psychological adaptation in from the cold. In B. Molinelli & V. Grimaldo (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of coping (pp. 1–34). Nova Science Publishers.

- Reyes, M. E. S., Carmen, B. P. B., Luminarias, M. E. P., Mangulabnan, S. A. N. B., & Ogunbode, C. A. (2021). An investigation into the relationship between climate change anxiety and mental health among Gen Z Filipinos. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02099-3

- Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Newsome, T. M., Barnard, P., & Moomaw, W. R. (2020). World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency. BioScience, 70(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biz088.

- Sanson, A., & Bellemo, M. (2021). Children and youth in the climate crisis. British Journal of Psychiatry Bulletin, 45(4), 205–209. https://www.cambridge.org/core

- Sanson, A., Wachs, T. D., Koller, S. H., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2018). Young people and climate change: The role of developmental science. In S. Verma & A. Peterson (Eds.), Developmental science and sustainable development goals for children and youth (pp. 115–138). Springer Publishing.

- Swain, K. (2020). Children’s picture books in an age of climate anxiety. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(9), 650–651. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30253-4

- Tam, K. P., & Milfont, T. L. (2020). Towards cross-cultural environmental psychology: A state-of-the-art review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 71, 101474. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101474

- Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2008). The evolutionary psychology of the emotions and their relationship to internal regulatory variables. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 114–137). The Guilford Press.

- Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440–463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018963

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). (2015). Unless we act now. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/reports/unless-weact-now-impact-climate-change-children

- Urban, J., Vačkářová, D., & Badura, T. (2021). Climate adaptation and climate mitigation do not undermine each other: A cross-cultural test in four countries. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 77, 101658. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101658

- Wullenkord, M., Tröger, J., Hamann, K. R., Loy, L., & Reese, G. (2021). Anxiety and climate change: A validation of the climate anxiety scale in a German-speaking quota sample and an investigation of psychological correlates. (Unpublished manuscript). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marlis-Wullenkord/publication/349763168_Anxiety_and_Climate_Change_A_Validation_of_the_Climate_Anxiety_Scale_in_a_German-_Speaking_Quota_Sample_and_an_Investigation_of_Psychological_Correlates/links/6040b9a54585154e8c7585ee/Anxiety-and-Climate-Change-A-Validation-of-the-Climate-Anxiety-Scale-in-a-German-Speaking-Quota-Sample-and-an-Investigation-of-Psychological-Correlates.pdf