ABSTRACT

This paper argues that, by shaping everyday attitudes towards women and perceptions of their value and decisions about them, family systems explain part of the difficulty in bridging the gap between men's and women's achievement in education. The gap is more pronounced outside the highly industrialized nations, where affordable mass education is not the standard, and gender differences in educational attainment are markedly affected by persisting cultural norms. I test this hypothesis by examining family systems that have had a lasting effect on gender norms. I find evidence that family systems explain gender differences in average years of education in 86 developing and middle-income countries around the globe, for the period 1950 to 2005.

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

Many countries aim for gender equality in education but, despite similar levels of economic development, some do better than others. A case in point, often cited, is Sri Lanka, which, despite not having strong economic growth, nevertheless has a fairly high level of gender equality, especially compared to countries with similar or higher national incomes (Sen Citation1999, 45; Hausmann et al. Citation2010). In 2010 the Sri Lankan educational system had already been gender equal for 20 years. In contrast, Pakistan recorded a gender ratio in educational attainment of 6 women to 10 men in 2010, a ratio Sri Lanka had achieved as early as 1950 (Barro & Lee Citation2010). The Sri Lankan accomplishment in educational gender equality is as impressive as Pakistan's lack thereof is puzzling.

What causes these gendered differences in educational outcomes? This study assesses the effect of family systems on gender equality in education in countries with medium to low levels of development. Previous studies have emphasized the importance of economic growth for promoting gender equality and its strong association with gender equality in education (Marshall Citation1985; Inglehart & Norris Citation2003). But economic growth is not sufficient to explain essential gender equality differences between countries, especially the sharp differences found outside the highly developed countries (Dilli et al. Citation2015). Since North (Citation1981, Citation1990) emphasized the importance of ideology in the enforcement of property rights and the role of institutions, institutions have become a prevalent explanation of the mechanism of historical heritage. Cultural norms, values and preferences can be seen as informal institutions, encompassing the typically unwritten codes of conduct that underlie and supplement formal rules (North Citation1990; Folbre Citation1994). Recent scholarly attention has turned to the role of historical and cultural legacies in determining development outcomes. For instance, a seminal paper by Acemoglu et al. (Citation2001) demonstrates that colonial origin strongly correlates with current economic performance. Alesina et al. (Citation2011) find evidence to support Boserup's hypothesis that traditional agricultural practices influenced the historical gender division of labour and the evolution and persistence of gender norms.

Culture is an important informal institution, but its long-term effect is hard to measure. The family, however, is a measurable cultural institution, with two marked qualities important for education. First, family characteristics provide information about the underlying rules, norms and preferences regarding women's appropriate role and behaviour. Within the family, these norms, values and preferences are transmitted from generation to generation, which can make them resilient to change. Second, decisions about how to invest in the children's education are made by the family, particularly the parents. The family's willingness to invest in female education will be in part determined by gender preferences inherited from former generations. Further, the size of the family and the extent of its influence may determine how far it will deviate from existing gender norms and how much it will invest in girls.

In a country with a functional education system that is both compulsory and affordable, as in the highly developed countries, we might not expect a large difference in gender patterns. But where parents face real costs to children's education, both financially and culturally (deviating from a social norm), gender preferences play a much stronger role. What role do family systems play in gender equality in education outside the highly developed nations? I look at the relation between family systems, marriage patterns and the gender ratio in education to see how different family systems have different effects and to find out whether historical preferences persist and to what extent. I argue that family systems influence the social and economic status of women and shape female bargaining power within the family and thus contribute to households’ everyday attitudes and decisions about investing in female education. Marriage patterns and family systems have been explored extensively for Western Europe and Asia (Lynch Citation1991; Engelen & Wolf Citation2005) and to some extent globally (Todd & Garrioch Citation1985; Todd Citation1987; Therborn Citation2004), and their effect on various gender roles has been partly explored as well (Dyson & Moore Citation1983; Laslett & Brenner Citation1989; Basu & Das Gupta Citation2001; De Moor & Van Zanden Citation2010).

This paper looks at the gender ratio in average years of education and its relation to family characteristics, with specific attention to female agency.Footnote2 Other studies explain gender equality in education in terms of income, female labour force participation and the gender wage gap (Jafarey & Maiti Citation2015) or religious preferences, regional factors and civil freedom (Dollar & Gatti Citation1999). To the best of our knowledge, only the paper by Bertocchi and Bozzano (Citation2015) explores the links between family systems and gender equality in education. These authors found that family structure in nineteenth century Italy significantly affected the female to male enrolment ratio in upper primary education. To the best of my knowledge, there are no studies that investigate the links between historical family systems and human capital investment in girls at a global level. This paper provides the first cross-country exploration of the relation between family systems and gender equality in education. By exploring the relation between family indicators such as marriage, inheritance rights and co-residence, it provides insight into the success or failure of countries in achieving gender equality in education over 55 years.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Why the educational gender gap matters

During the past three decades, a large and growing volume of studies has emphasized the instrumental benefits of women's education. Evidence suggests that gender inequality, by lowering the average level of human capital in education, has a direct negative effect on long-term economic growth (Klasen Citation2002). Indirectly, gender inequality in education has a negative effect on fertility decline, and on structural investments since women are marginally represented in policies (King & Hill Citation1997; Dollar & Gatti Citation1999; Klasen & Lamanna Citation2009). General rates of return to education are stronger when women are included, and women benefit individually by receiving larger private returns from labour market participation (Psacharopoulos Citation1994).

Other gains from female education accrue from the benefits of educating mothers. Maternal education has been found to improve knowledge of healthcare (Barrera Citation1990) and household efficiency (Rosenzweig & Schultz Citation1982). Higher levels of maternal education are related to declines in infant mortality (Strauss & Thomas Citation1995) and are associated with intergenerational improvements in the health, education and the general wellbeing of their children (King et al. Citation1986; TP Schultz Citation1988; Strauss & Thomas Citation1995 Currie & Moretti Citation2003). Mothers are vital links in the transfer of resources to children. Empirical evidence suggests that women are more likely than men to favour children in their resource allocation behaviour (Thomas Citation1994; Hoddinott & Haddad Citation1995; Glick & Sahn Citation2000; Currie & Moretti Citation2003; Doss Citation2012). For example, Handa (1994, 119–137) finds, in a study in Jamaica, that mothers with higher education tend to have higher bargaining power, which results in higher investments in the health and education of the children. Some authors suggest that mothers tend to channel resources specifically to their daughters (Thomas Citation1994; Glick & Sahn Citation2000; Currie & Moretti Citation2003). In short, the benefits of educating girls are manifold and gender equality in education seems to make social and economic sense (World Bank 2011; Fiske Citation2012). Why then does gender inequality persist in education?

Factors affecting female education

Poverty makes it hard to invest in human capital. To some extent, poverty also explains gender inequality; economic prosperity is strongly associated with gender equality in general (Inglehart & Norris Citation2003) and with gender equality in education, especially in secondary education (Marshall Citation1985). A poor family struggling to come out on a small budget may prefer to invest in a son, in anticipation of his future remittances. However, investing in boys rather than girls is not necessarily a rational economic cost-benefit decision; rather, it is likely to be based on normative views of women's roles, value and earning capacity. As Boserup (Citation1970, 119–121) succinctly notes:

If a poor country belongs to a culture with a positive attitude to higher education for girls, we find a high proportion of girls among the relatively few adult students. By contrast, if the dominant culture is hostile or indifferent to the higher education of girls, we find few girls among the adult students even if the country is relatively advanced.

Several other hypotheses suggest reasons why female educational participation lags behind male participation, focusing on either supply and demand, or on access to education. In the first place, education needs to be supplied: schools must be built and teachers hired. The state is largely responsible for providing the legal and physical infrastructure needed for schooling and state investments tend to be guided either by ideological motives or by a desire to modernize and industrialize (Benavot & Riddle Citation1988; Meyer et al. Citation1992; Friedman Citation2002; Lindert Citation2004). The provision of mass education by the state overcomes credit constraints faced by local actors in financing education (Engerman et al. Citation1998; Galor et al. Citation2009). With the state making education accessible, free and compulsory, parents find it easier to send their children to school. It seems indisputable that parents want their children to receive education because of seemingly obvious income and social benefits. But opponents of this view stress that the benefits of education are not clear-cut and they argue that without a clear demand for female education, increasing the supply of schooling yields little result (Easterly Citation2006; Banerjee & Duflo Citation2011).

A further factor driving the demand for education is labour force participation. Low female labour force participation, leaving the labour force after marriage and the unskilled nature of female labour are various reasons offered to explain why women's education trails behind men's. The neoclassical argument asserts that the household, with unified household preferences, applies a division of labour directed at maximizing efficiency and family income (Becker Citation1964, Citation1965; TW Schultz Citation1961, Citation1974). A ‘natural’ division of labour exists within the household: men have a natural strength advantage, while women specialize in reproduction, child care and related domestic activities (Murdock & Provost Citation1973). Female domestic specialization, by reducing women's time in the labour force, makes women's earnings and job opportunities lower than men's. This in turn discourages investment in female human capital (Becker Citation1985, 198). A considerable literature questions this neoclassical view, and other explanations for restricted female labour force participation abound, citing, for example, gender-specific agricultural practices, per capita incomes, industries and cultural beliefs (Folbre Citation1994; Goldin Citation1994; Fernández & Fogli Citation2009; Iversen & Rosenbluth Citation2010; Alesina et al. Citation2013). Whatever the root causes, the consequence is that women play a smaller part in the labour market and educational investment in women thus yields lower returns than investment in men.

As the family is the primary locus of decisions about girls’ education, the study of family systems and relationships can shed light on beliefs about the value of women. An abundant literature on household bargaining underlines the importance of the way resources are distributed among family members (Becker & Lewis Citation1973; Becker Citation1991; Hanushek Citation1992; Agarwal Citation1997). The members’ relative positions in the distribution are governed by norms and culturally determined gender roles, and these norms and roles in turn create social expectations about women's entitlements, duties and responsibilities. Human capital investment in women may be hampered by gender roles, when expectations of proper female behaviour rule out women for investment. Powerful legal and institutional factors determining the disposition of household assets, such as family laws regarding property rights and social entitlements, help to perpetuate such norms (Folbre Citation1986, Citation1994, Citation2002).

The resilience of gender norms across generations is a product of cultural transmission and socialization within the family. Vital cultural preferences and social norms, such as family attitudes towards fertility or women's labour force participation, are passed on through generations as a result of ‘imperfect empathy’ (Bisin & Verdier Citation2001, Citation2008), which means that the family wishes to socialize their offspring optimally, yet this ‘optimal’ state is subjectively coloured towards the family's own cultural experiences and preferences. Family choices about, for example children's education, marriage partners and place of residence, all contribute to passing on cultural values (Bisin & Verdier Citation2000, Citation2008; Cohen-Zada Citation2006). Families are willing to assume high costs to socialize their children according to their own preferences, and one way they do it is by deciding what kind of education they will receive.

A family system can be defined as ‘a set of beliefs and norms, common practices, and associated sanctions through which kinship and the rights and obligations of particular kin relationships are defined'. It typically defines

what it means to be related by blood, or descent, and by marriage; who should live with whom at which stages of the life course; the social, sexual, and economic rights and obligations of individuals occupying different kin positions in relation to each other; and the division of labour among kin-related individuals. (Mason Citation2001, 160–161)

A family system classification can be useful to researchers because family systems carry elements of gender systems, such as the appropriate roles for wives and husbands and the preferred sex of children (Basu & Das Gupta Citation2001). Todd (Citation1987) finds that stronger female authority within the family system is positively correlated with the educational advancement of the next generation. Measuring the impact of various historical institutions on a historical gender equality index, Dilli et al. (Citation2015) find that family systems as an institution have insignificant effects on various elements of gender equality. Our study differs from theirs in using a different classification and concentrating solely on a single outcome, gender equality in education – this may explain why our results differ from theirs. For more information, see the notes to Appendix .

Family systems can also reveal how far girls exercise choice or agency, in other words, their ability to make meaningful life decisions (Sen Citation1999; Kabeer Citation2005; World Bank Citation2011). In societies where inheritance and marriage rules favour men, for example obliging the woman to live with the husband's family after marriage, women have little economic independence or agency (Basu & Das Gupta Citation2001). As I explain further below, if a girl is to participate in education she must also have certain abilities within the family context, such as the ability not to be married at a young age, to own property or to generate her own income. The level of agency women can exercise within the family system is important for investment in their educational careers. For instance, King et al. (Citation1986) observe that in Asia, in areas with lower female agency mothers have the least effect on their daughters completed education (Pakistan), whereas in areas with higher female agency (the Philippines) their effect is much stronger.

FAMILY ORGANIZATION AND GENDERED EDUCATIONAL INVESTMENT

Women's value and agency in the family

Family systems allow us to understand the gender relations and preferences of many generations ago. Questions to ask are whether these preferences persist, to what extent they persist, and whether family systems have different types of influence. To answer these questions, I look at three features of family systems that could lead to gender inequality: marriage patterns, inheritance structures and domestic organization or co-residence patterns.Footnote3

Marriage patterns inform us about the agency women have in whether, when and whom to marry. They thus reflect women's position in their natal household and in the new household they will set up. Key elements are the age at first marriage and the age difference between husband and wife: the spousal age gap. Young married girls may be prevented from taking advantage of education or work opportunities by household responsibilities, pregnancy and child rearing, and social restrictions such as limitation of their mobility (Mathur et al. Citation2003; Jain & Kurz Citation2007). On the other hand, being able to delay marriage and the first birth is often strongly correlated with an increase in education and earnings (Goldin & Katz Citation2000; Pezzini Citation2005; Field & Ambrus Citation2008) and can positively influence women's time and resource investment in developing their human capital (Jensen & Thornton Citation2003). A small spousal age gap to a certain extent reflects equality between a woman and her partner (Casterline et al. Citation1986) and higher female bargaining power than in family systems where women marry men much older than themselves (Lloyd Citation2005; Carmichael et al. Citation2011). These factors are related: research shows that women who marry before 18 are more likely to be married to much older men (Mensch Citation1986; Jain & Kurz Citation2007). In family systems where women marry when they are past adolescence, and to men of similar age, we may assume that they are more able to make decisions about their human capital development, and that of their children, than women who are married younger and to older men.

The question here is one of direction of causality: do women marry later because their family system allows them to receive more education, or do they receive more education because their family system allows them to marry later? The expansion of girls’ formal schooling is often seen as one of the main influences on family structure and behaviour (Jain & Kurz Citation2007). However, we could argue that when marriage age is relatively high from the outset, girls are more likely to participate in education. Modernization in the form of industrialization, schooling and increasing employment opportunities for women can provide some departures from traditional gender roles, but this only partly accounts for the way the gender education gap varies from society to society. The decision to delay marriage is not only shaped by current incentives such as human capital accumulation or labour force participation, but also reflects cultural values, even though these values may have emanated from historical economic realities (Lynch Citation1991). Although age at marriage is likely to be sensitive to the economic environment, marriage patterns also appear to be shaped by other features of family systems.

The second feature I look at is inheritance structure. The ability of women to inherit indicates the strength of female property rights, which in turn are positively related to increases in female educational attainment (Quisumbing & Maluccio Citation2003; Roy Citation2011), and the well-being of children. In Nepal, for example, women's land rights empower women by increasing their control over household decision making, which in turn benefits children's health (Allendorf Citation2007). Anthropologists distinguish three basic inheritance types: patrilineal, matrilineal or bilateral. Patrilineal systems, in which men control the productive resources, generally imply weak female bargaining power and a lower economic status for women. This gender imbalance can inhibit a mother's ability to provide for daughters, resulting in an intergenerational transfer of a lower economic position of women (Cox & Fafchamps Citation2007, 3767). Matrilineal inheritance seems to suggest some form of female property rights. In reality, however, property is transmitted through males related to the mother and women are prohibited from holding property. However, in this system women are arguably valued more highly than in the patrilineal system, where women do not form such links. Bilateral systems do make it possible for women to inherit and give them a somewhat stronger economic bargaining position, which implies better ability to provide for themselves and their daughters.

Our third feature of interest is domestic organization or co-residence patterns. A family is either nuclear (the conjugal couple and their children) or complex. Complex families include adults other than the conjugal couple. There are three types: extended families, stem families and polygamous families. ‘Domestic organization' often refers to what people consider their ideal living arrangement, which does not necessarily reflect the actual arrangement at every stage of life (see for example Karve Citation1965). This measure is therefore highly normative, and can be used to describe ideal gender roles. The four types of family have different gendered expectations of appropriate female roles within the family, and these expectations in turn influence female human capital investment.

A nuclear family excludes family members other than the conjugal couple from everyday decision-making. A new household is established after marriage and is generally based on the mutual consent of both spouses, thus providing a more solid base for gender equality in household investment decisions, than those families where marriage is not on the basis of such mutual consent. Nuclear families are associated with high age at marriage and thus with a longer period of capital accumulation for women. They are also thought to have a positive influence on female labour force participation, which is positively related to human capital accumulation. And with the emphasis on the conjugal couple, and moving out of the parental home after marriage, the nuclear family supports a stronger agency with respect to parental authority (Richard et al. Citation1983; Todd Citation1987; De Moor & Van Zanden Citation2006).Footnote4

Extended families consist of more than one married couple, generally three generations including relatives such as grandparents, aunts, uncles and (married) siblings. Cultures with extended families are considered to be typically less egalitarian than those that favour the nuclear family, with hierarchical male-dominated structures and inheritance, weakening the position of the women in the family (Boserup Citation1970; Alesina et al. Citation2013). Arranged marriages are especially frequent in extended families, often resulting in young female marriage with a high spousal age gap and a young bride's outmigration to the husband's family, weakening her bargaining power (Gupta Citation1976, 82). In these families, boys are favoured for human capital investment because their remittances flow back directly into the natal home.

In the stem family, one of the children remains at home, under the authority of the parents. The position of women in these families seems similar to that of the extended family. Decision-making involves more relatives than is the case in the nuclear family, and resources must be distributed among more kin. However, age at marriage is generally late in stem families and not all children are subject to parental control, which could have positive effects for the position of women and their human capital investment.

The polygamous family, found mostly in Africa, is one with multiple wives (polygyny) or multiple husbands (polyandry), though the latter is rare. Polygyny is generally considered non-beneficial for female educational investment, as it drives up the demand for wives and increases the price men must pay to marry them. This system is only sustainable when population growth is high and men marry women younger than themselves. Investment flows into ‘buying’ wives and ‘selling’ daughters, decreasing capital investment, including that for education (Tertilt Citation2005, Citation2006). In addition, women share their husband's earnings with his other spouses. When fertility per woman remains high, fewer resources are available per child than is the case in other family types, which implies less education investment potential. When son preference is strong, boys will be favoured over girls for human capital investment. However, son preference is not clear-cut in societies with this kind of family. In Africa especially, a woman can have considerable autonomy, even if she lacks economic status, and may run her own household in a separate dwelling (Murdock Citation1981). Polygamous societies that prize high fertility will focus strongly on daughters (Cox & Fafchamps Citation2007). However, age at marriage is generally low and inheritance is either patrilineal or matrilineal, never bilateral.

Many of these features of family systems are likely to reinforce one another. For instance, son preference may be exacerbated in the extended family, because large families can divide labour more strictly and concentrate human capital investment on certain children only (Das Gupta Citation1999; Duranton et al. Citation2009). This son preference has an impact on educational investment, but also on the provision of food and the division of inheritance (Rosenzweig & Schultz Citation1982; Greenhalgh Citation1985; King & Hill Citation1997). In a patrilineal system where girls marry young and cannot claim inheritance rights, sons are considered the more rational investment choice as the old-age caregivers of the natal household, but in bilateral systems this is not necessarily the case. Todd (Citation1987) argues that women in extended families where their position is favourable (measured by their propensity to inherit, relatively high age at marriage and low spousal age gap) are positively associated with literacy attainment. This links up with research that suggests there is a positive relation between maternal education and investment in the grandchildren's human capital – the so-called ‘grandmother effect’ (Baizan & Camps Citation2007; Parker & Short Citation2009).

Capturing family systems

There is data that enable us to measure marriage patterns between 1950 and 2005. Domestic organization and inheritance are available as historical time-fixed indicators measured around the 1920s. This allows us to measure whether such historical systems still have an impact on the period between 1950 and 2005. By combining the types of domestic organization with inheritance, as a basic indicator of the economic status of women in the family, we can expand the four basic types described above into nine sub-types. shows these systems, example countries for each type, and the expected effects of the female to male ratio in each system.

Table 1: Overview of family systems

The patrilineal extended family systems of Pakistan and India exemplify the effects of family systems on gender outcomes in education. Here, inheritance rights (patrilineal) and residence patterns (patrilocal)Footnote5 are weighted in favour of men. Property is transmitted though the male line, implying poor property rights for girls; the fathers and husbands control the family budget. Girls marry young and spousal age gaps are large, leaving little room for female agency in human capital investment decisions. Families have little incentive to invest in daughters’ human capital: girls move to the husband's home after marriage, cutting off remittances to the natal family. This is not to say that all parents make a harsh cost-benefit analysis. A girl's marriage offers a viable and culturally accepted ‘exit strategy’, where the young bride will be taken care of by a new family. Nonetheless, this family system is expected to have one of the lowest potentials for gender equality in education.

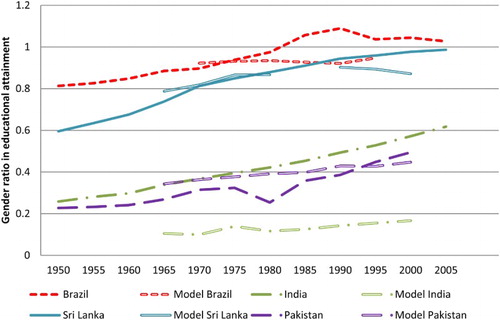

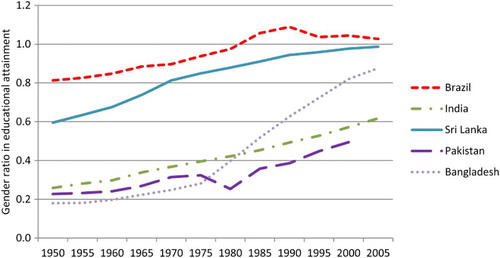

compares gender gaps in educational attainment for five countries from 1950 to 2005. The large gaps and slow educational development of Pakistan and India are clear. There is some progression towards gender equality, but the curve is not as steep as that of Bangladesh. The other two countries, Brazil and Sri Lanka, examples of the bilateral nuclear family system, do not have steeper convergence curves but they do have higher starting positions for the incorporation of women into education. It is true that mass education thrived much earlier in Latin America than in, for example, India, but Latin American countries also have a high level of female inclusion in education (Frankema Citation2009; van der Vleuten Citation2009).

Figure 1: Gender gaps in educational attainment in five countries, 1950–2005

Source: Barro & Lee 2010

The bilateral nuclear system as it exists in Sri Lanka has a strong development potential for female educational participation because of the strong position it assigns to women in the family (Caldwell Citation1996). Inheritance is bilateral, the domestic residence is nuclear and women have access to property, making them less dependent on relatives outside the conjugal couple. In addition, Sri Lankan families historically have a higher age at marriage than families in other countries in South Asia. To show the marriage ages in historical comparison, compares Sri Lanka with India and China in the early twentieth century, showing that Sri Lankan female age at marriage was high, well past adolescence. Age at marriage is measured using the singulate mean age at marriage (SMAM – the average years of single life, of those who marry before age 50). Hajnal (Citation1953) created this measure to calculate the mean age at marriage, and more recently it has been used as an indicator of female empowerment (Carmichael Citation2011; World Bank Citation2011). The spousal age gap, measured by subtracting female SMAM from male SMAM, has been used as a similar indicator of women's marginalization within marriage and society (Edlund Citation1999).

Table 2: Early marriage patterns in three East and South-East Asian countries, early twentieth century

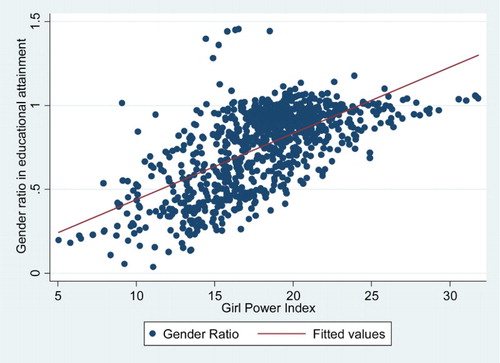

In addition to domestic organization and inheritance, female SMAM and the spousal age gap are further useful as measures of female bargaining power and equality within marriage. Unlike inheritance and domestic residence, data availability allows for the continuous measurement of these indicators throughout the period 1950 to 2005. De Moor and Van Zanden (Citation2006, Citation2010) developed the ‘girl power index’ (GPI) to combine both indicators by subtracting the spousal age gap from the female age at first marriage. Carmichael et al. (Citation2011) tested this measure against contemporary female empowerment measures such as the Global Gender Gap (World Economic Forum) and the Gender Inequality Index (UN) and found them to correlate very strongly. shows that the GPI also relates strongly to the gender ratio in average years of education.

Figure 2: Correlation female to male gender ratio (pop. 15 +) and the girl power index (GPI), 1950–2005

The above observations suggest hypotheses about the relation between family systems and gendered educational attainment. Late marriage and a low spousal age gap should increase female educational attainment and a higher score on the GPI should narrow the gender gap in education. Patrilineal inheritance probably widens the gender gap in education and conversely, bilateral inheritance should narrow it. Expectations for matrilineal inheritance fall between the negative and positive ones of the patrilineal and bilateral inheritance types. Complex families are expected to have higher gender inequality in education than nuclear families.

DATA AND ANALYSIS

To test these hypotheses, I used an unbalanced panel of 86 countries for which data are available on gender inequality in education, family factors and several socioeconomic controls between 1950 and 2005. I followed the subdivision of Barro and Lee (2012), which considers two broad groups of countries in their dataset: 24 advanced countries and 122 developing countries. The use of other data led to a diminishing of that total number: 21 advanced countries and 86 developing countries. The focus is on developing countries since they display the most variability in the dependent variable and in age at first marriage.Footnote6 The main dependent variable is the ratio of female to male average years of education and the data are by 5-year intervals. in the Appendix provides descriptive statistics for all variables. The analytical framework is a random effects panel regression, allowing for the inclusion of time-invariant individual parameters such as the family system operators. In a random effects model, the unobserved variables are assumed to be uncorrelated with all the observed variables. I preferred the random effects model to a pooled OLS model because it can account for individual heterogeneity and to a fixed effects model because it can account for time-invariant variables vital to my analysis, such as the family systems.Footnote7 I used Newey-West (Citation1987) standard errors clustered on countries to correct for serial correlation in the panel.

The full regression model is specified as follows:

Here yit refers to the ratio of female to male average years of education in country i at time t. The parameter refers to the set of family system dummies,

to the GPI,

to the lagged set of socioeconomic controls and

to the religion dummies. All estimated models include year

and regional

fixed effects to control for individual change over time and by region unexplained by the model.Footnote8 The

is an error term, capturing all other omitted factors. Dummies are used for the time-invariant family systems, each with a different combination of domestic organization (nuclear, extended, stem and polygamous) and inheritance practices (patrilineal, matrilineal and bilateral). Both domestic organization and inheritance are classified as dominant when the proportion of the historically practising population exceeds a benchmark level of 20% of the population, otherwise the variable is excluded. The family systems are generalized to the total population. The patrilineal extended system is the reference category, for which I expect the lowest gender ratio in education. Data for these family systems are from a dataset in Rijpma and Carmichael (Citation2016) which brings together data from Todd (Citation1987) and the Murdock-Narodov atlas.Footnote9 These data sources have been used frequently by other authors (Duranton et al. Citation2009; Alesina et al. Citation2013; Tur-Prats Citation2014).Footnote10 The is a continuous measure, consisting of data from Sarah Carmichael's work on marriage patterns (Carmichael Citation2011; Carmichael et al. Citation2011). It is lagged with one period (t-1), as are the other time-variant factors, to account for delays in the effect of the variables. For instance, mother's bargaining power and subsequent investment possibilities are expected to influence the education of the next generation of girls, and a five-year lag adjusts for this delay.Footnote11 This does, however, imply a diminished number of observations.

The economic control variables include (the log) of GDP per capita, the female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) and public expenditure on education, all with a 1-period lag (t-1). The parameter of religion describes religious adherence: Catholic, Protestant, Muslim, Hindu, or other. Following Inglehart and Baker (Citation2000), the religion dummy takes the value of one when a particular religion is dominant and zero otherwise. The benchmark for dominance of adherents was set at 50%. For the highly developed countries, a dummy for Protestant was included as well.Footnote12

RESULTS

Model 1 in shows the relation between the gender ratio, the various family systems and the full spectrum of control variables. Models 2 to 4 add the marriage patterns, either the GPI (2), solely the age at marriage (3) or the spousal age gap (4). The last model adds a comparison, in which the 21 highly developed countries are also included.Footnote13 shows that most expectations about the link between women's value in the family and the gender ratio in education are met. Model 1 shows a statistically significant correlation between the gender ratio in education and those family systems where the women's value is high and families are relatively small. Nuclear systems have a more significant positive association with the gender ratio in education than the patrilineal extended family system, but only when women have a say in the transmission of property, in other words, when the nuclear system is combined with bilateral or matrilineal inheritance. The estimates for the matrilineal nuclear and bilateral nuclear family systems are 0.154 and 0.142 respectively, both significant at 1%. The second of these estimates implies that the bilateral nuclear system increases the value of the gender ratio in education by 14.6 percentage points. This is a fairly large increase compared with the mean of the gender ratio in education, which is 0.72 in the sample.

Table 3: Family systems, 1950–2005

Patrilineal inheritance has no significant effect on female educational participation, but this could be because the baseline category is a patrilineal system as well. Nevertheless, I would have expected the patrilineal nuclear system to perform better than the extended ones, because son preference might be increased by the nature of extended families, as explained above. Matrilineal inheritance has no positive effect on the female to male ratio when the domestic organization type is extended. Surprisingly, matrilineal inheritance does have a positive effect in combination with a polygamous family system. In addition the patrilineal polygamous family system is positive and significant vis-à-vis the patrilineal extended system, though I expected polygamous systems in general to perform similarly or worse. With the inclusion of the GPI in the second model, the effect of the patrilineal extended system becomes more significant than that of the polygamous systems, which could indicate that the influence of these polygamous systems on the gender ratio is driven by differences in age at marriage and spousal age gap. This supports the findings by Tertilt (Citation2005, Citation2006) that spousal age differences are higher in polygamous than in monogamous systems. In sum, inheritance types that favour women have positive effects in all the models. Nuclear family systems perform better than extended systems, as expected. Polygamous systems seem to have a more positive effect than the extended system, but this is more robustly so in combination with a historically matrilineal inheritance structure. This may also be because girls are valued more highly on the basis of their future fertility (Cox & Fafchamps Citation2007), or because of (domestic) labour conditions that allow girls to go to school while boys need to work. The reasons for a smaller gender gap in families with a tradition of matrilineal inheritance and a polygamous structure should be analysed in future research.

Turning to the link between the GPI and the educational gender gap, we see that the positive and significant sign of the coefficient supports the hypothesis that later marriage and a smaller spousal age gap are positively associated with the gender ratio in education. In model 2, keeping all control variables equal, a one-point increase in the GPI results in a 1.5 percentage point increase in the gender ratio. When marriage partners are on a more equal footing, i.e., when ‘girl power’ increases, gender equality in education rises as well. Further investigation into the two variables constituting the GPI show that both SMAM and the age gap have the right positively and negatively significant signs respectively, with somewhat larger coefficients (models 3 and 4). As mentioned earlier, the inclusion of the age gap decreases the effect of the polygamous family system on the gender ratio in education, while the age at marriage does not have this effect. I added model 5 because I wondered whether the inclusion of highly advanced countries would weaken the significance of either of the variables. With the addition of the 21 advanced countries, the GPI is still significant at a 10% level.

in the Appendix tests the robustness of these marriage pattern findings by applying alternative estimation methods. The same controls, year and region dummies apply, but for the sake of brevity these are unreported. Models 1 and 2 show the benchmark random effects estimation and a pooled OLS estimation with robust standard errors. The GPI is significant and positive and the two models yield very similar results, providing some confidence in my model specification (Wooldridge Citation2009, ch. 14). As mentioned earlier (footnote 7), a Hausman test indicated that fixed-effects model might have been better, but this would yield no estimations for my time-invariant family systems. With the GPI now as the main independent variable of interest, I performed a fixed-effects estimation, reported in model 3 in . Though the coefficient of the GPI is somewhat smaller, it remains robustly significant. Lastly, I recognize that the GPI suffers from an endogeneity problem because high education of women might result in later marriage. I therefore applied a traditional technique of using lags of the GPI as an instrument in the model, using a two-stage least-squares approach. I lagged these variables once, and my model still yielded significant results. I interpret these last models with caution and use them only as a test to check the robustness of my results. Since Angrist and Krueger (Citation2001) have pointed out the mechanical and a-theoretical nature of this traditional choice of instrument, the use of lagged variables as instruments is under heavy debate. All in all though, I find that the GPI is robustly associated with the gender ratio in average years in education.

Some interesting findings appeared in the controls. Surprisingly, expenditures on education were negatively related to the gender ratio in education. The results are similar even when I do not control for income per capita. It must be noted that the data quality of this particular variable is weak, which discourages drawing strong conclusions. Nonetheless, the relative worsening of female education by public spending seems like an unlikely outcome. A possible explanation might be that added public expenditure on education benefits men over women. Regressing the same model on female and male education separately, I found that expenditure had no significant relation to female education, but a small significant and positive (10% level) effect on male education (not reported). When the highly developed countries are included in the analysis, the detrimental effect of public educational spending on the gender ratio disappears. This could indicate two things. First, the effects of educational spending on male instead of female education could be stronger in developing countries because of a gender bias of state institutions. Second, in the period from 1950 onwards, developing countries began their mass education systems, which at first generally included more men than women. This feature diminished as mass educational systems matured, as is the case in the developed regions and reflected by the drop in the significance of the coefficient in model 4. Further investigation into this variable might yield some interesting results.

The control variable GDP per capita provides some indication of the resources available for education. The positive sign of the GDP coefficient indicates that as income per capita increases and the constraints of poverty become less severe, gender differences in educational enrolment diminish. The female labour force participation rate showed no significant association with the gender ratio in education. It is difficult to assess the causality direction of the relationship between female labour force participation and female education. Development economists have shown that the effect of education on labour force participation rates is not uniform across years of education and that the relationship may be U-shaped. This means that female gains in education are not always reflected by female gains in income and employment or vice versa (Cameron et al. Citation2001).

Religious adherence produces some interesting results. Recent studies show that female education is more constrained in a society with a large share of Muslim adherents, and to some extent in one with a large share of Hindu adherents, than it is in a society with a large share of any Christian faith (Norton & Tomal Citation2009; Cooray & Potrafke Citation2010). However, when I include regional dummies, I find that the Muslim and Hindu dummy variables are insignificant, while without including regions dummies (not reported), I did obtain a significant coefficient. This implies that the cultural effects are captured by regional differences, not by religious ones.

To compare the effect of the different variables influencing the gender ratio in education, in the Appendix shows the standardized coefficients of the full family systems model. The effect of the family system variables is very strong, even stronger than that of income per capita. The matrilineal nuclear family and the bilateral nuclear family both stand out as having a particularly strong association with the gender gap, though the effect of the matrilineal polygamous system is strong as well. The coefficient for the GPI and its comparative effect on the educational gender gap is also stronger than that of income per capita. Though not as large as the effect of the family characteristics, GDP per capita still has a positive effect on the gender ratio in education. In comparison, the coefficient for public expenditure on education is smaller, and still negative. Once again, there are no strong negative effects for the Muslim and Hindu variables.

As a robustness check, I tested the full model again only for the year 2000, for the set of developing countries ( in the Appendix). The association with the gender gap in education and the GPI remains robustly significant. However, many family systems now lose their significant effect compared to the base category of the patrilineal extended system. The bilateral nuclear system retains its significant effect on the gender ratio in education and the effects of the matrilineal extended system come out as negative. An F-test (F(8, 46) = 4.12; P = 0.0009) performed for all family systems shows that these family systems do have some jointly significant effect on the gender ratio.

illustrates the predictive power of our model, by showing the actual time-series of the gender gap in educational attainment, and the outcome as predicted by our model for five countries. Pakistan, with a patrilineal extended family type, and Brazil and Sri Lanka, both with bilateral nuclear types, seem to fit the model quite well. The actual gender gaps demonstrate somewhat more volatility than the model can pick up, but there seems to be a fair match between the actual and the modelled outcomes. The modelled outcome for India shows the model's imperfections as well. India is already a weak performer, but the modelled outcome predicts the gender gap to be even larger. Possibly, the prediction missed some important elements adding to Indian-specific gender equality in education, such as caste divisions. Another possible explanation is that there is a marked contrast between the historical demographic patterns of North and South India, and that using the Indian country-average family type as data does not accurately portray reality.

CONCLUSIONS

This study adds to the debate on the determinants and persistence of gender gaps in education and the effects of cultural institutions more broadly. I argue that family systems and female agency are a productive area for inquiry into the roots of gender inequalities and their ongoing persistence. I found robust evidence of the association between the value placed on women in the family and the gender ratio in education, whether this is via institutional effects of family systems or via marriage patterns associated with high female agency. The family as an institution may thus either limit or increase women's freedom of choice and life opportunities more than it does men's, through unequal educational participation. Matrilineal and bilateral family types are strong predictors of equal gender participation in education, especially when they are also the nuclear family type. I found that extended or polygamous families did not necessarily have a negative effect on the gender ratio in education; rather, the ratio depended more on the type of inheritance system the family used.

Historical legacies do not weaken a society's ability to overcome gender inequalities. Countries across the world are trying to overcome gender barriers in education, improve female labour force participation and, more generally, make women valued as assets to society. Moreover, women are themselves active agents in their struggle towards gender equality in all aspects of life. My study demonstrates that the struggle may be more arduous in some parts of the world than in others, because of differences in the slow-changing cultural institution of the family, and the different ways in which has been organized historically. Strong female agency within the family enables women to make important life decisions, such to invest in their own education and their daughters’. Where both spouses are educated, intergenerational transfer of knowledge benefits. This study provides a well-quantified study with a wide range of international data and indicates that in countries where women lack the capacity to choose, either because they marry into a new family at a young age, or because they lack property rights, it is likely that less will be invested in women's education than in men's.

Notes

2 Defined as the ability to make meaningful life decisions (Sen Citation1999; Kabeer Citation2005; World Bank 2011).

3 Additional features that can be used are preferences for patrilocality, matrilocality, bilocality or neolocality and biological mythology (the child seen as a product of father, mother or both), but lack of data and difficulty in measuring these features prevents us considering them here.

4 Goode (Citation1970 – now textbook modernization theory), saw the ideal type of nuclear family as positively related to industrialization and believed that family patterns around the world would eventually resemble the Western-type nuclear family.

5 ‘Patrilocality' refers to the married couple setting up residence in or near the husband's family's home.

6 The 86 countries of interest are Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Argentina, Armenia, Bangladesh, Benin, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chile, China, Colombia, Congo, Croatia, Cuba, Czech Republic, Côte d'Ivoire, Ecuador, Egypt, Estonia, Gambia, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Liberia, Lithuania, Malawi, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritania, Mexico, Mongolia, Morocco, Mozambique, Nepal, Niger, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Republic of Korea, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Syrian Arab Republic, Tajikistan, Thailand, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Republic of Tanzania, Uruguay, Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), Yemen and Zambia. Although Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and Venezuela were high-income countries in 1950, I do include them in this group for a better comparison with the Barro and Lee dataset.

7 A Hausman test showed that a fixed-effects model might have been better, but this model was not an option because the family systems are time-invariant. I used a fixed effects model as a robustness check for the girl power index (GPI).

8 Regions are classified according to the CLIO-Infra OECD classification (Van Zanden et al. Citation2014). The regions are: East Asia and the Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Advanced Economies, Europe and Central Asia.

9 See notes for in the Appendix.

10 Further elaboration on this dataset can be found in the notes to in the Appendix.

11 I tested for the robustness of this lag period against using multiple lags and found that the latter yielded similar results. However, because the lag period decreases the number of observations, I selected the shortest lag period.

12 In the set of low to middle developed countries, no country reached the benchmark of 50% for the variable ‘Protestant'.

13 The high income countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, UK and US.

References

- Acemoglu, D, Johnson, S & Robinson, JA, 2001. The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review 91(5), 1369–1401. doi: 10.1257/aer.91.5.1369

- Agarwal, B, 1997. “Bargaining” and Gender Relations: Within and Beyond the Household. Feminist Economics 3(1), 1–51. doi: 10.1080/135457097338799

- Alesina, AF, Giuliano, P & Nunn, N, 2011. On the origins of gender roles: Women and the plough. NBER Working Paper 17098. National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17098.

- Alesina, AF, Giuliano, P & Nunn, N, 2013. On the origins of gender roles: Women and the plough. Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(2), 469–530. doi:10.1093/qje/qjt005.

- Allendorf, K, 2007. Do women's land rights promote empowerment and child health in Nepal? World Development 35(11), 1975–1988. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.12.005.

- Angrist, JD & Krueger, AB, 2001. Instrumental Variables and the Search for Identification: From Supply and Demand to Natural Experiments The Journal of Economic Perspectives 15(4), 69–85. doi: 10.1257/jep.15.4.69

- Baizan, P & Camps, E, 2007. The impact of women's educational and economic resources on fertility. Spanish birth cohorts 1901–1950. Gendering the Fertility Decline in the Western World 7, 25–58.

- Banerjee, A & Duflo, E, 2011. Poor economics: A radical rethinking of the way to fight global poverty. New York, Public Affairs.

- Barrera, A, 1990. The role of maternal schooling and its interaction with public health programs in child health production. Journal of Development Economics 32(1), 69–91. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(90)90052-D.

- Barro, RJ & Lee, JW, 2010. A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. NBER Working Paper 15902, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Basu, A & Das Gupta, M, 2001. Family systems and the preferred sex of children. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences 8: 5350–5357. doi: 10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/02151-3

- Becker, GS, 1964. Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Becker, GS, 1965. A theory of the allocation of time. Economic Journal 75(299), 493–517. doi: 10.2307/2228949

- Becker, GS, 1985. Human capital, effort, and the sexual division of labor. Journal of Labor Economics 3(1), S33–S58.

- Becker, GS, 1991. A Treatise on the Family. Harvard Univ Pr, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- Becker, GS & Lewis, HG, 1973. On the Interaction between the Quantity and Quality of Children. Journal of Political Economy 81, S279–S288. doi:10.2307/1840425.

- Becker, SO & Woessmann, L, 2009. Was Weber wrong? A human capital theory of protestant economic history. Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(2), 531–596. doi:10.1162/qjec.2009.124.2.531.

- Benavot, A, & Riddle, P, 1988. The expansion of primary education, 1870–1940: Trends and issues. Sociology of Education 61(3), 191–210. doi:10.2307/2112627.

- Bertocchi, G, & Bozzano, M, 2015. Family structure and the education gender gap: Evidence from Italian provinces. CESifo Economic Studies 61(1), 263–300. doi:10.1093/cesifo/ifu026.

- Bisin, Alberto, & Verdier, T, 2000. ‘Beyond the melting pot’: Cultural transmission, marriage, and the evolution of ethnic and religious traits. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(3), 955–988. doi:10.1162/003355300554953.

- Bisin, A, & Verdier, T, 2001. The Economics of Cultural Transmission and the Dynamics of Preferences. Journal of Economic Theory 97(2), 298–319. doi:10.1006/jeth.2000.2678.

- Bisin, Alberto, & Verdier, T, 2008. Cultural transmission. In Durlauf, SN & Blume, LE (Eds), The new Palgrave dictionary of economics, 2nd edn. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke. http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_C000549.

- Boserup, E, 1970. Woman's role in economic development. George Allen & Unwin, London.

- Caldwell, B, 1996. The family and demographic change in Sri Lanka. Health Transition Review: The Cultural, Social, and Behavioural Determinants of Health 6 Suppl: 45–60.

- Cameron, LA, Dowling JM, & Worswick, C. 2001. Education and labor market participation of women in Asia: Evidence from five countries. Economic Development and Cultural Change 49(3), 459–477.

- Carmichael, S, 2011. Marriage and power: Age at first marriage and spousal age gap in lesser developed countries. The History of the Family 16(4), 416–436. doi:10.1016/j.hisfam.2011.08.002.

- Carmichael, SG, De Moor, T, & van Zanden, JL, 2011. When the heart is baked, don't try to knead it: Marriage age and spousal age gap as a measure of female agency. In Engelen, T, Boonstra, O & Janssens, A (Eds), Levenslopen in Transformatie: Liber Amicorum Bij Het Afscheid van Prof. Dr. Paul M. M. Klep, 208–221.

- Casterline, JB, Williams, L & McDonald, P, 1986. The age difference between spouses: Variations among developing countries. Population Studies 40(3), 353–374. doi:10.1080/0032472031000142296.

- Cohen-Zada, D, 2006. Preserving religious identity through education: Economic analysis and evidence from the US. Journal of Urban Economics 60(3), 372–398. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2006.04.007.

- Cooray, A, & Potrafke, N, 2010. Gender inequality in education: Political institutions or culture and religion? Working Paper Series of the Department of Economics, University of Konstanz 2010-01. Department of Economics, University of Konstanz. http://ideas.repec.org/p/knz/dpteco/1001.html.

- Cox, D, & Fafchamps, M, 2007. Extended Family and Kinship Networks: Economic Insights and Evolutionary Directions, in: Schultz, TP, Strauss, J & Rosenzweig, MR (Eds.), Handbook of Development Economics, 3711–3784. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Currie, J, & Moretti, E, 2003. Mother's education and the intergenerational transmission of human capital: Evidence from college openings. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4), 1495–1532. doi:10.1162/003355303322552856.

- Das Gupta, M, 1999. Lifeboat versus corporate ethic: Social and demographic implications of stem and joint families. Social Science & Medicine 49(2), 173–184. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00096-9.

- De Moor, T & van Zanden, JL, 2006. Vrouwen en de geboorte van het kapitalisme in West-Europa. Boom, Amsterdam.

- De Moor, T, & van Zanden, JL, 2010. Girl Power: The European marriage pattern and labour markets in the north sea region in the late medieval and early modern period. The Economic History Review 63(1), 1–33. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2009.00483.x.

- Dilli, S, Rijpma, A & Carmichael, SG, 2015. Achieving gender equality: Development versus historical legacies. CESifo Economic Studies 61(1), 301–334. doi:10.1093/cesifo/ifu027.

- Dollar, D, Gatti, R, 1999. Gender inequality, income, and growth: Are good times good for women? Policy Research Report on Gender and Development, Working Paper Series 1.

- Donno, D, & Russett, B, 2004. Islam, authoritarianism, and female empowerment: What are the linkages? World Politics 56(4), 582–607. doi: 10.1353/wp.2005.0003

- Doss, C, 2012. Intrahousehold bargaining and resource allocation in developing countries. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/9145 (accessed 2 February 2016).

- Duranton, G, Rodríguez-Pose, A, & Sandall, R, 2009. Family types and the persistence of regional disparities in Europe. Economic Geography 85(1), 23–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2008.01002.x

- Dyson, T, & Moore, M, 1983. On kinship structure, female autonomy, and demographic behavior in India. Population and Development Review 9(1), 35–60. doi:10.2307/1972894.

- Easterly, W, 2006. The white man's burden: why the west's efforts to aid the rest have done so much ill and so little good. Penguin, New York.

- Edlund, L, 1999. Son preference, sex ratios, and marriage patterns. Journal of Political Economy 107(6), 1275–1304. doi:10.1086/250097.

- Engelen, T, Wolf, AP, 2005. Marriage and the family in Eurasia: Perspectives on the Hajnal hypothesis. Aksant, Amsterdam.

- Engerman, SL, Mariscal, E & Sokoloff, KL, 1998. Schooling, suffrage, and the persistence of inequality in the Americas, 1800–1945. Unpublished Paper, Department of Economics, UCLA.

- Fernández, R & Fogli, A, 2009. Culture: An empirical investigation of beliefs, work, and fertility. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 1(1), 146–177. doi:10.1257/mac.1.1.146.

- Field, E, & Ambrus, A, 2008. Early marriage, age of menarche, and female schooling attainment in Bangladesh. Journal of Political Economy 116(5), 881–930. doi: 10.1086/593333

- Fish, SM, 2002. Islam and authoritarianism. World Politics 55(01), 4–37. doi:10.1353/wp.2003.0004.

- Fiske, EB, 2012. World atlas of gender equality in education. UNESCO, Paris.

- Folbre, N, 1986. Hearts and spades: Paradigms of household economics. World Development 14(2), 245–255. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(86)90056-2

- Folbre, N, 1994. Who pays for the kids? Gender and the structure of constraint. Routledge, London.

- Folbre, N, 2002. The invisible heart: Economics and family values. New Press, New York.

- Frankema, E, 2009. Has Latin America always been unequal? A comparative study of asset and income inequality in the long twentieth century. Koninklijke Brill, Leiden & Boston.

- Friedman, M, 2002. Capitalism and freedom: Fortieth anniversary edition. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Galor, O, Moav, O & Vollrath, D, 2009. Inequality in landownership, the emergence of human-capital promoting institutions, and the great divergence. Review of Economic Studies 76(1), 143–179. doi:10.1111/j.1467-937X.2008.00506.x.

- Glick, P, & Sahn DE, 2000. Schooling of girls and boys in a West African country: The effects of parental education, income, and household structure. Economics of Education Review 19(1), 63–87. doi:10.1016/S0272-7757(99)00029-1.

- Goldin, C, 1994. The U-Shaped female labor force function in economic development and economic history. NBER Working Paper Series No. 4707. National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w4707.

- Goldin, C, & Katz, LF, 2000. The power of the pill: Oral contraceptives and women's career and marriage decisions. NBER Working Paper Series No. 7527. National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w7527.

- Goode, WJ, 1970. World revolution and family patterns. Free Press, New York.

- Greenhalgh, S, 1985. Sexual stratification: The other side of ‘growth with equity’ in East Asia. Population and Development Review 11(2), 265–314. doi:10.2307/1973489.

- Gupta, GJ, 1976. Love, arranged marriage, and the Indian social structure. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 7(1), 75–85.

- Hajnal, J, 1953. Age at marriage and proportions marrying. Population Studies 7(2), 111–136. doi:10.2307/2172028.

- Handa, S, 1994. Gender, headship and intrahousehold resource allocation. World Development 22(10), 1535–1547. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(94)90036-1.

- Hanushek, EA, 1992. The trade-off between child quantity and quality. Journal of Political Economy 100(1), 84–117. doi: 10.1086/261808

- Hausmann, R, Tyson, LD, & Zahadi, S, 2010. The global gender gap report 2010. World Economic Forum. Available online: http://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2010 (accessed 2 February 2016).

- Hoddinott, J & Haddad, L, 1995. Does female income share influence household expenditures? Evidence from Côte d'Ivoire. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 57(1), 77–96. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0084.1995.tb00028.x.

- Inglehart, R & Baker, WE, 2000. Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review 65(1), 19. doi:10.2307/2657288.

- Inglehart, R & Norris, P, 2003. Rising tide: Gender equality and cultural change around the world. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Iversen, T & Rosenbluth, FM, 2010. Women, work, and power: The political economy of gender inequality. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Jafarey, S & Maiti, D, 2015. Glass slippers and glass ceilings: An analysis of marital anticipation and female education. Journal of Development Economics. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.12.005.

- Jain, S & Kurz K, 2007. New insights on preventing child marriage: A global analysis of factors and programs. ICRW Report. Washington DC: International Center for Research on Women (ICRW).

- Jensen, R, & Thornton, R, 2003. Early female marriage in the Ddeveloping World. Gender & Development 11(2), 9–19. doi:10.1080/741954311.

- Kabeer, N, 2005. Gender equality and women's empowerment: A critical analysis of the third millennium development goal. Gender and Development 13(1), 13–24. doi: 10.1080/13552070512331332273

- Karve, IK, 1965. Kinship organization in India. Asia Publ. House, Mumbai.

- King, EM, & Hill, MA, 1997. Women's education in developing countries: An overview. In King, EM & Hill, MA (Eds), Women's education in developing countries: Barriers, benefits, and policies. World Bank Publications, Baltimore and London. 1–50.

- King, EM, Peterson, J, Adioetomo, SM, Domingo, LJ & Syed, SH, 1986. Change in the status of women across generations in Asia. Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, CA.

- Klasen, S, 2002. Low schooling for girls, slower growth for all? Cross-country evidence on the effect of gender inequality in education on economic development. The World Bank Economic Review 16(3), 345–373. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhf004

- Klasen, S & Lamanna, S, 2009. The impact of gender inequality in education and employment on economic growth: New evidence for a panel of countries. Feminist Economics 15(3), 91–132. doi:10.1080/13545700902893106.

- Laslett, B & Brenner, J, 1989. Gender and social reproduction: Historical perspectives. Annual Review of Sociology 15, 381–404. doi:10.2307/2083231.

- Lindert, PH, 2004. Growing public: Social spending and economic growth since the eighteenth century, vol. 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Lloyd, CB, 2005. Growing up global: The changing transitions to adulthood in developing countries. The National Academies Press, Washington DC.

- Lynch, KA, 1991. The European marriage pattern in the cities: Variations on a theme by Hajnal. Journal of Family History 16(1), 79–96. doi:10.1177/036319909101600106.

- Lynch, KA, 2011. Why weren't (many) European women ‘missing’? The history of the family 16(3), 250–266. doi:10.1016/j.hisfam.2011.02.001.

- Marshall, SE, 1985. Development, dependence, and gender inequality in the third world. International Studies Quarterly, 29(2), 217–240. doi: 10.2307/2600507

- Mason, KO, 2001. Gender and family systems in the fertility transition. Population and Development Review 27, 160–76.

- Mathur, S, Greene, A & Malhotra, A, 2003. Too young to wed: The lives, rights and health of young married girl. International Center for Research on Women, Washington DC. http://www.icrw.org/publications/too-young-wed-0.

- Mensch, B, 1986. Age differences between spouses in first marriages. Biodemography and Social Biology 33(3-4), 229–240. doi:10.1080/19485565.1986.9988641.

- Meyer, JW, Ramirez, FO & Soysal, YN, 1992. World expansion of mass education, 1870–1980. Sociology of Education, 65(2), 128–149. doi:10.2307/2112679

- Murdock, GP, 1981. Atlas of world cultures. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh.

- Murdock, GP & Provost, C, 1973. Factors in the division of labor by sex: A cross-cultural analysis. Ethnology 1 (2), 203–225. doi:10.2307/3773347.

- Newey, WK & West, KD, 1987. A Simple, Positive Semi-Definite, Heteroskedasticity and Autocorrelation Consistent Covariance Matrix. Econometrica 55 (3), 703–708. doi:10.2307/1913610.

- North, DC, 1981. Structure and change in economic history. Norton, New York.

- North, DC, 1990. Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Norton, SW & Tomal, A, 2009. Religion and female educational attainment. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 41(5), 961–986. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4616.2009.00240.x.

- Parker, EM, & Short SE, 2009. Grandmother coresidence, maternal orphans, and school enrollment in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Family Issues 30(6), 813–836. doi: 10.1177/0192513X09331921

- Pezzini, S, 2005. The effect of women's rights on women's welfare: Evidence from a natural experiment. Economic Journal 115(502), C208–C227. doi:10.1111/j.0013-0133.2005.00988.x.

- Psacharopoulos, G, 1994. Returns to investment in education: A global update. World Development 22(9), 1325–1343. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(94)90007-8

- Quisumbing, AR & Maluccio, JA, 2003. Resources at marriage and intrahousehold allocation: Evidence from bangladesh, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and South Africa. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 65(3), 283–327. doi:10.1111/1468-0084.t01-1-00052.

- Richard, W, Robin, J & Laslett, P (Eds.), 1983. Family Forms in Historic Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Rijpma, A & Carmichael, S, 2016. Testing Todd: Global data on family characteristics. Economic History of Developing Regions, 31(1): doi:10.1080/20780389.2015.1114415.

- Rosenzweig, MR & Schultz, TP, 1982. Market opportunities, genetic endowments, and intrafamily resource distribution: Child survival in rural India. The American Economic Review 72(4), 803–815.

- Roy, S, 2011. Empowering women: Inheritance rights and female education in India. CAGE Online Working Paper Series 45. Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy (CAGE). http://ideas.repec.org/p/cge/warwcg/45.html.

- Schultz, TP, 1988. Education investments and returns. Handbook of Development Economics 1(1), 543–630. doi: 10.1016/S1573-4471(88)01016-2

- Schultz, TW, 1961. Investment in human capital. The American Economic Review 51(1), 1–17.

- Schultz, TW, 1974. Economics of the family: Marriage, children, and human capital. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. http://www.nber.org/books/schu74-1 (accessed 2 February 2016).

- Sen, A, 1999. Development as freedom. Oxford University Press, Amsterdam.

- Strauss, J & Thomas, D, 1995. Chapter 34: Human resources: Empirical modelling of household and family decisions. In Behrman, JR & Srinivasan, TN (Eds.), Handbook of Development Economics. North Holland, Amsterdam, 1883–2023.

- Tertilt, M, 2005. Polygyny, fertility, and savings. Journal of Political Economy 113(6), 1341–1371. doi:10.1086/498049.

- Tertilt, M, 2006. Polygyny, women's rights, and development. Journal of the European Economic Association 4(2/3), 523–530. doi: 10.1162/jeea.2006.4.2-3.523

- Therborn, G, 2004. Between sex and power: Family in the world, 1900–2000. Routledge, London.

- The World Bank. 2011. World development report 2012: Gender equality and development. Available from: http://go.worldbank.org/6R2KGVEXP0 (accessed 2 February 2016).

- Thomas, Duncan. 1994. Like father, like son; like mother, like daughter: Parental resources and child height. Journal of Human Resources 29(4), 950–988. doi:10.2307/146131.

- Todd, E, 1987. The causes of progress: Culture, authority and change. Blackwell, Oxford.

- Todd, E, & Garrioch, D, 1985. The explanation of ideology: Family structures and social systems. Blackwell, Oxford.

- Tur-Prats, A, 2014. Family types and intimate-partner violence: A historical perspective. Job Market Paper. Available from: https://www.dropbox.com/s/9vx6fja6spfxuid/Tur-Prats%20A%2C%20Job%20market%20paper.pdf (accessed 2 February 2016).

- Vleuten, L van der, 2009. The girls' march to school: A comparative historical analysis of gender equalization in education in Argentina and Japan, ca. 1880–1970. Master thesis, University of Utrecht, Utrecht. http://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/35892 (accessed 2 February 2016).

- Van Zanden, JL, Baten, J, Mira d'Ercole, M, Rijpma, A, Smith, C, & Timmer, M (Eds), 2014. How was life? Global Well-being since 1820. OECD Publishing, Paris (accessed 2 February 2016).

- Weber, M, 2001. The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. Routledge, New York.

- Wooldridge, JM, 2009. Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. Cengage Learning, Mason.