Abstract

Background: An important determinant of a medical student's behaviour and performance is the department's teaching and learning environment. Evaluation of such an environment can explore methods to improve educational curricula and optimise the academic learning environment.

Aim: The aim is to evaluate the educational environment of undergraduate students in the Department of Family Medicine as perceived by students.

Setting: This descriptive quantitative study was conducted with one group of final-year students (n = 41) enrolled in 2018, with a response rate of 93% (n = 39). Students were in different training sites at SMU.

Methods: Data were collected using the Dundee Ready Educational Environmental Measure (DREEM) questionnaire. Total and mean scores for all questions were calculated.

Results: The learning environment was given a mean score of 142/200 by the students. Individual subscales show that ‘academic self-perception’ was rated the highest (25/32), while ‘social self-perception’ had the lowest score (13/24). Positive perception aspects of the academic climate included: student competence and confidence; student participation in class; constructive criticism provided; empathy in medical profession; and friendships created. Areas for improvement included: provision of good support systems for students; social life improvement; course coordinators being less authoritarian and more approachable; student-centred curriculum with less emphasis on factual learning and factual recall.

Conclusion: Students’ perceptions of their learning environment were more positive than negative. The areas of improvement will be used to draw lessons to optimise the curriculum and learning environment, improve administrative processes and develop student support mechanisms in order to improve students’ academic experience.

Introduction

The term ‘learning environment’ commonly refers to the diverse physical locations, contexts and cultures in which students learn. It encompasses the culture of a university faculty, and its presiding ethos and characteristics, including how students interact and their relationships with one another as well as the ways in which teachers may organise an educational setting.Citation1 Some educationists use it interchangeably with the term ‘institutional climate’.Citation2 A vital driver for a student's behaviour and performance in health professions education institutions is the learning environment.Citation3 Furthermore, it is widely agreed that the academic learning environment influences the attitudes, knowledge, skills and academic progression of students.Citation4

Assessing the educational environment correlates positively with determining student approaches to study, understanding of practice, desired educational outcomes and satisfaction with educational programmes.Citation5,Citation6 Undergraduate medical students’ perceptions of their educational environment have been studied at traditional and innovative medical schools. These studies have shown that students’ perceptions of the educational environment can be a basis for implementing modifications and thus optimising the educational environment. The educational environment influences how, why and what students learn.Citation7 As a result of the recent imperatives towards enhanced quality assessment monitoring and the commitment of health professions education to student-centred teaching and learning, there is increased interest in the learning environment.Citation7 Learning environment research for undergraduate medical students seeks to assess students’ perceptions of their environment and can guide medical and health sciences teachers to introspect, devise and incorporate the best teaching strategy.Citation8

Student satisfaction is an important indicator of the quality of learning experiences and is usually related to several outcome variables.Citation9 In this regard, researchers have been guided in their thinking by learning theories that stress the need and value of learning environments that provide engaging activities for students.Citation4,Citation10 The learning theories that apply particularly when assessing the learning environment include the social theories of learning, behavioural theories, self-determination theories, transformative learning theories and experiential learning.Citation11

Although there are diverse determinants of how individual students view different aspects of a particular learning environment, perceived rating measurements report their perceptions precisely.Citation1 Previous research has shown that findings from educational environmental investigations can be used effectively to implement and measure changes to the educational delivery and the physical environment.Citation7,Citation8

Many instruments are currently available to assess the learning environment of universities. Of all instruments available, the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM), Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure, Clinical Learning Environment and Supervision, and Dental Student Learning Environment Survey have been found to be the most suitable for undergraduate medicine, postgraduate medicine, nursing and dental education, respectively.Citation12 The Manchester Clinical Placement Index (MCBI) is commonly used to assess perceptions of students placed in hospitals and measures two subscales, namely learning environment and training.Citation12 The most widely used contemporary instrument to assess undergraduates in medical courses is the DREEM,Citation9,Citation10,Citation13,Citation14 which was developed by an international Delphi panel in Scotland.Citation1 The DREEM questionnaire has the highest reliability and validity scores in comparison with other instruments measuring undergraduate medical students’ perceptions of the learning environment and clinical placements.Citation8,Citation9,Citation12 It has been proposed as the standard to be used for measuring undergraduate learning environments.Citation15 Because students of family medicine at SMU learn in community health care centres and not in hospitals, the eight-item Manchester Clinical Placement Index (MCBI), which was introduced in 2012 and tests for learning environment and training only and not the five subscales that are the objectives for our study, the MCBI was not selected for this study.Citation12 Furthermore, the DREEM tool has been used extensively in family medicine curriculum evaluations.Citation14,Citation16 The DREEM questionnaire was also used in a cross-sectional survey to assess clinical associate students’ perception of their learning environment at the University of the Witwatersrand.Citation3

Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University (SMU) was established as an independent health sciences university in 2015. The vision of SMU is to provide all-inclusive health sciences education and to employ educational approaches that include evidence-based methods for curriculum design, delivery and assessment of learning. The management structure of the university has also changed since 2016 with the appointment for the first time of a deputy vice-chancellor (DVC) for teaching and learning. There is a focus on, and commitment to, excellence in learning and teaching.Citation17

On the other hand, students appear to be dissatisfied with the learning environment at SMU, according to reports presented by the academic planning and curriculum development committee (APCDC) and memoranda submitted by students to the vice-chancellor during the student protest strikes on the campus during 2015, 2016 and 2018. Undergraduate students report that the academic environment at SMU is not conducive to learning, it is not based on their needs and is teacher-centred rather than student-centred.Citation18

In the final year medical students spend six weeks in family medicine training. Of these, at least five weeks are spent in rural, community-based primary health care facilities. The students receive lectures at the central department for the first week and thereafter are taught at the various sites by family physicians.

The Department of Family Medicine at SMU conducts almost all its teaching in the community using the problem-based model. From 2014 to 2017, the department achieved the award for the best clinical teaching department.

Family Medicine is an emerging speciality in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation19,Citation20 There has been consensus nationally that this discipline is a core contributor to primary health care and critical to the achievement of equitable health outcomes for all. In order to accomplish this, training in family medicine must be community-based within the district health system with an adequate number of trained clinical personnel.Citation21 Assessing community-based education as part of the curriculum is of vital importance as elaborated in the SPICES (student-centred; problem-based; integrated; community-based; elective; systematic) model.Citation22

Consequently, taking all these developments into consideration (change in the university's structure and student dissatisfaction), the aim of this study was to investigate student perceptions of their learning environment in undergraduate family medicine teaching at SMU, in order to optimise the students’ learning environment experience. To reach this aim we had the following objective, namely to determine student perceptions of their learning activities, facilitators, academic self-perceptions, learning atmosphere and social self-perceptions. We sought to identify any learning areas in the students’ perceptions of their learning environment that need to be addressed, explore trends in the learning environments at different site placements and, should deficiencies be found, make recommendations to the HOD on optimising the learning environment in undergraduate family medicine teaching at SMU.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional, descriptive study using self-administered DREEM questionnaires.

Study population

There are six groups of final-year students annually with the total number of students per year being about 240. Students are placed in these groups by the School of Medicine in their first year of study where they remain for their entire study period at SMU. Students do not choose to which group they are allocated and there are no differences between the groups which, have on average 40 students per group. One group of students made up the sample.

The health facilities where the students rotated included Phokeng Health Centre (two students), Tlhabane CHC (four students), Odi District Hospital (seven students), Job Shimankane Thabane Hospital (four students), Phedisong CHC (three students), Jubilee District Hospital (five students), Bapong CHC (three students), Swartruggens Hospital (six students), Soshanguve CHC (four students) and Brits District Hospital (one student).

Sample size

Final-year family medicine students were surveyed at the end of their six-week family medicine block. There are six groups of students annually. The students in each group are randomly selected by the school of medicine from first year of study. One randomly selected group of students made up the sample. There are on average 40 students in each group. All the students in one group were approached to participate. Therefore a form of random sampling was used.

The aims and objectives of this study were purely descriptive, aiming to measure perceptions of students around various topics, and not specifically to test any hypothesis; thus, a sample size calculation was not performed.

Data collection

An independent third party distributed the questionnaires on the last day of the family medicine block. This was after their assessments when students felt less vulnerable.

Data analysis

Information from the questionnaires was captured onto a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) and exported to SPSS statistical software (version 25; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) for analysis. Scores for the domains were computed and summarised using appropriate measures of central tendency and dispersion. Trends in the results of student perceptions between the different training sites were explored using stratified analysis.

The DREEM questionnaire has 50 items that assess five domainsCitation6 as can be seen in . There were nine negative items (items 4, 8, 9, 17, 25, 35, 39, 48 and 50), for which correction was made by reversing the scores; thus, after correction, higher scores indicate disagreement with that item. Items with a mean score of ≥ 3.5 are true positive points; those with a mean of ≤ 2 are problem areas; scores between these two limits indicate aspects of the environment that could be enhanced. The maximum global score for the questionnaire is 200, and the global score is interpreted as follows: 0–50 = very poor; 51–100 = many problems; 101–150 = more positive than negative; 151–200 = excellent.Citation6,Citation19

Table 1: The DREEM questionnaire domains

Total percentage scores reflect the following:

agreement: calculated by adding responses of ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’;

uncertain: calculated by giving a percentage to all responses that indicated ‘uncertain’;

disagreement: calculated by adding responses of ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘disagree’.

Ethical considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Stellenbosch University Research and Ethics Committee (number S18/02/039). The Head of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care Department and the Acting Dean of the School of Medicine at SMU gave permission to conduct the study.

Results

A total of 39/42 (93%) students completed the questionnaire. There were 18 (46%) females and 21 (54%) male participants. The mean age of the students was 24.9 years (SD 2.6) and only two had other degrees (Biomedical Technology and BSc (Hons) Medical Microbiology).

DREEM scores for all students

The total mean score for the DREEM was 141/200. The lowest mean score was for ‘The teaching overemphasises factual learning’ (1.23). shows the percentage of students who either agree, disagree or are neutral regarding each statement. The best scores were as follows:

Students are encouraged to participate in teaching sessions (86% agreed).

Teaching helps to develop their competence (81% agreed).

Confidence (86% agreed).

Teachers practise a patient-centred approach (86% agreed).

Teachers give clear examples during teaching (82% agreed).

Students are confident of passing this year (almost 90%).

Students have learnt a lot about empathy in their profession (96%).

Students’ problem-solving skills are being well developed (91%).

Students are able to ask any questions they wish to (96%).

The atmosphere is relaxed during lectures (91%).

Much of what they have learnt seems relevant to a career in health care (96%).

Table 2: Scores for the five subscales of the DREEM questionnaire

The five subscales of the DREEM questionnaire

The lowest minimum score for any domain was for the perception of the course organiser, which was 4 (9%), indicating a very poor perception of the organiser (see ). However, the mean score for this domain was 32 (72%) with a standard deviation (SD) of 8, which indicated that overall the course organiser was moving in the right direction.

Table 3: Comparison of male and female perceptions of the learning environment

As regards the perception of learning subscale, the mean score was 34 (72% of the possible perfect score) indicating that students had a positive perception of learning. It is noteworthy that the minimum score was 17 and the standard deviation 6.9, indicating that there were students who viewed teaching negatively, although none perceived the teaching as very poor.

The students perceived the atmosphere as positive (mean score 34 ± 7.3 SD; 71%). The minimum score was 20, indicating that the students perceived many issues in need of change.

The mean score for the students’ academic self-perception was 25 ± 4.0 SD (77%), which indicates that their academic self-perception leaned towards the positive side. Their social self-perception was adequate with mean scores of 16.9 ± 4.1 SD (60.0%). These results are represented in .

In total there were four problem areas (scores with a mean of ≤ 2).

Item 4: I am too tired to enjoy the course.

Item 9: The course organisers are authoritarian.

Item 25: The teaching overemphasises factual learning.

Item 28: I seldom feel lonely.

One item (no. 10) detected a strength point in the educational climate: I am confident about passing this year.

The subscale which scored highest was ‘academic self-perception’ (25; 77%), which implies a feeling of academic self-confidence, followed by ‘learning’ (34/48), and course coordinator perception (32/44), which score 72% for each. When we use the DREEM scoring guide to interpret the results for these two subscales, the 34/48 for learning perception implies that the students have a positive perception of their learning. Similarly, the 32/44 for the course organisers implies that the students perceive the course organisers to be moving in the right direction to make the learning environment student-centred, although they feel that that there is room for improvement,Citation9 indicating a more positive perception of their learning and a feeling that the course coordinator is moving in the right direction, respectively (see for results of subscales).

Categorisation of DREEM overall scores

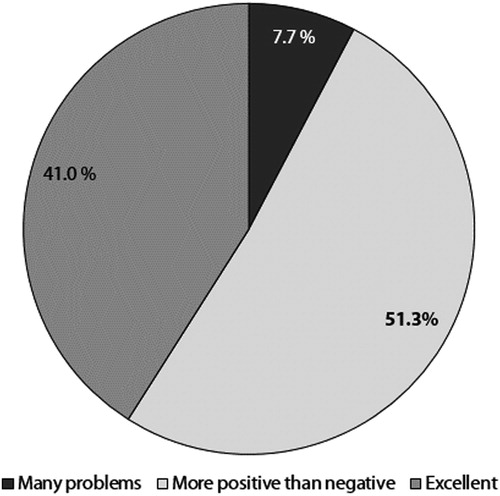

In total, 51% of the students felt that the family medicine training environment was more positive than negative; 41% felt that it was excellent, while only 7.7% (= 3) of the students felt that the final-year family medicine programme has many problems ().

Comparison of male and female perceptions of the learning environment

Male students seemed to perceive the learning environment more favourably than female students for all the subscale elements, although the difference was not statistically significant. The independent t-test indicated a p-value > 0.05 for all learning environments ().

Health facility and learning environment

Although the number of students training at the different facilities was small, it seems that the students were especially happy with Phokeng CHC and perceived its learning environment to be excellent (161/200) ().

Table 4: Health facility and learning environment

It is emphasised that the DREEM score is not related to the quality of clinical care rendered at the individual facilities; it is a reflection of students’ perceptions of their learning environment.

Discussion

The DREEM evaluation of the final-year family medicine students’ perception of their learning environment had a total mean score of 141/200, which indicates a more positive than negative perception of their environment. These family medicine students perceived their learning environment to be slightly better than those reported by students at other medical schools in India (123/200)Citation10 and Nigeria (118/200).Citation23 Medical students from Sri Lanka (108/200)Citation12 and Iran (100/200)Citation24 perceived their learning environment to be poorer than that of SMU. The differences could be attributed to the fact that our total DREEM score was based on a single group of students, while other studies administered the DREEM questionnaire either to a large number of undergraduate students in different years of enrolment,Citation25 to all students in medical schools,Citation20 or conducted comparative cross-sectional studies in a number of medical schools.Citation15 Other single-cohort studies in medical schools in the United Kingdom (139/200)Citation10 and Nepal (130/200)Citation24 also perceived their learning environment to be more positive than negative. Valuable insights and recommendations were drawn from surveys of family medicine students at universities similar to SMU, in Egypt and Saudi Arabia where research designs were used.Citation19,Citation26 In these studies, students’ major concerns were that the curriculum was not student-centred and the quality of teaching was poor.Citation19,Citation26

Our scores are higher than those of several studies conducted in other family medicine departments of middle-income countries, e.g. King Abdul Aziz University (102.0),Citation27 King Khalid University (112.95),Citation28 and Qassim University (112.0).Citation29 Our mean score of 141/200 and the score of 2.90 for the students’ perception of whether they consider teaching to be student-centred indicates the dominance of student-centred methods of teaching.Citation29 The total DREEM score was slightly higher for males compared with females; however, with the small sample, we could not conclude whether the difference was statistically significant. Although there have been studies reporting on gender difference in the perception of the DREEM total and subscale scores at other medical universities,Citation30,Citation31 the reported effect of gender is inconsistent; this could be a topic for further investigation in a larger sample size.Citation32,Citation33

One important application of the DREEM instrument is the analysis of the individual items. This directly shows the strengths and weaknesses of different aspects of the educational environment. The majority of items in the domain of learning scored 2.9 or more, indicating few problems. Our results showed one weak learning domain issue that should receive attention and this was the lowest item for the entire DREEM questionnaire: 1.23 for ‘The teaching overemphasises factual learning’. This learning encourages more superficial learning and remembering facts rather than a deeper learning with understanding and application of knowledge. This finding is consistent with that of Arzuman et al.Citation33 Perhaps, in the short time they spend in this course, lecturers provide facts on clinical conditions and the current guidelines on managing common clinical conditions, which may be perceived as an excess of factual knowledge that students are expected to remember and recall for their written assessments. The students may have referred to the class-based teaching (which includes factual learning) and not clinical teaching which focuses on real patients (hands-on/practical learning). Further exploration of this aspect through a qualitative research design may provide a clearer picture of what the students are actually referring to. Negative perceptions of the learning subscale were reported in Spain where they were attributed to the use of traditional methods of teaching (lecturer standing in front of the class and talking).Citation34 On the other hand, item number 47 (‘Long-term learning is emphasised over short-term’) is perceived more positively. It is worth noting that durable knowledge is one of the primary goals of medical education.Citation35

The highest individual scores in this section indicate that teaching helps to develop the students’ competence (3.38) and confidence (3.26), which are important traits needed for their future professional career. Students also believed that they were encouraged to participate in class (3.36), which is an indication of an open and interactive learning atmosphere. Contrary to our findings, medical students in Malaysia rated class participation at 1.88, which indicated their teaching does not provide enough experiences and participation in class in order to help them develop and grow their confidence.Citation33

The other concerns that could be improved upon are that teaching is perceived to be teacher-centred and the course does not really allow the student to be an active learner. This also ties in with their perception that the teaching could be more stimulating. These areas need to be enhanced as the family medicine curriculum strives to focus on student-centred and problem-based learning. In the curriculum greater emphasis should be placed on the promotion of student-centred learning. This may involve training the clinical trainers and has already begun as part of the European Union Project nationally.Citation36

In terms of quality of teaching (course organiser perceptions), educators in the family medicine programme are perceived as moving in the right direction. The best traits of teachers, as perceived by students, include being knowledgeable (3.46), espousing a patient-centred approach to consulting (3.36) and giving students clear examples (3.21). This finding is similar to that of the study by Arzuman et al.,Citation33 which indicated that teachers had good communication skills. The students also recognised that their teachers are well prepared for their teaching sessions (3.18). This is encouraging for the family medicine programme, as the findings of a study conducted by Aghamolaei et al.Citation37 were that teachers were not knowledgeable, not prepared for their lectures and did not provide constructive feedback. However, students in our study also considered that there was some room for improvement as far as constructive criticism is concerned and the course organisers are perceived as being too authoritarian (1.69). This area must be explored further through interviews with the students for a better understanding, and then measures implemented to ensure that course organisers are more approachable and student-centred.

In contrast to studies conducted in other medical schools, which found that academic self-perceptions were rated low,Citation25,Citation38 in our study this was rated highest. Students strongly believed and were confident that they would pass (3.51), they had learnt a lot about empathy in their profession (3.44), and much of what they had learnt seemed relevant to a career in health care (3.01). They also perceived that their problem-solving skills were being well developed (3.03), which is an important objective of the family medicine programme indicating that the learning environment contributes to the fulfilment of the course objectives. This good positive perception of the academic environment at the family medicine department indicates that the academic curriculum is transparent, relevant and student-centred. Moreover, the students’ perceptions were proved accurate when they all passed the course. The findings of our study differ from those of Hamid et al.Citation39 who found that ‘academic self-perception’ had a low score of 20/32. Our study reveals a more positive feeling among the students with regard to their academic environment.

All students rated their learning atmosphere in the category of ‘a more positive attitude’ with a mean score of 34/48 (71%). The best perceived aspect of the learning atmosphere is that students felt there were opportunities available to them to develop their interpersonal skills and were able to ask questions as they desired, which potentially enhanced their communication skills. The atmosphere was relaxed during teaching, thereby promoting teacher–student interaction and sharing of scientific and conceptual knowledge. Other studies also found that the overall learning atmosphere for the students was perceived as positive and relaxed and that this promoted learning.Citation34

In the social domain, the stress of studying medicine outweighed the joy during the course and the perception was that the atmosphere to motivate students as learners could be improved upon. The students could have perceived the course to be too stressful for them to enjoy; it included being away from family and friends for the family medicine clinical rotation. The course was perceived to be relatively well timetabled. This result was different from other studies in which students did not consider their course to be well timetabled and this caused stress for them.Citation39,Citation40

Although the students had different social environments at their clinical placements, their overall ‘social self-perception’ received the lowest scores of all the domains. Students perceived their social environment as ‘not too bad’. This subscale reflects that students expect the educational environment to be creative and less stressful. There is an indirect relationship between stress and the academic performance of students. Students reporting higher stress levels perceive a lack of self-confidence.Citation9,Citation41 The social self-esteem domain was scored the lowest by both male and female students. The item asking about friends (3.28) was similar to perceptions of students at other universities.Citation36,Citation42 The presence of friendly relationships between students reflects a healthy support structure. Problem-based learning encourages interaction between the students and this has been shown to build friendly relationships.Citation42 The item ‘I am too tired to enjoy this course’ had a low score (1.33) while the feeling of loneliness scored 1.96. This indicates a lack of supportive strategies for stressed students. Unfortunately, this situation prevails at many other universities.Citation25,Citation42 It has been reported that the top stressors for undergraduate students are perceived lack of social support, depression and concerns regarding the completion of clinical work.Citation43

It is recommended that SMU offer support and teach students how to manage and cope with the various stressful situations they encounter, whether academic, social or financial. The presence of positive and friendly relationships among students is essential as a coping mechanism to minimise the effects of stress generated by the study load. On this point, it was unclear as to whether the students were referring to social, academic or personal support systems. In order to improve the social aspect and ensure that apart from the academic aspect of teaching and learning family medicine students also enjoy their social life, we need to further explore this aspect and take measures accordingly as this will impact on their experience of working in clinical settings away from home. Concerning the perception of learning, it was noted that the high mean score of 34 indicated a positive perception of the educational environment.

Academic self-perception showed a positive score (32). This is mainly concerned with the students’ views of their academic abilities and skills, as well as their expected duties, as one of the most important factors affecting the academic success of the students is their learning skills.Citation26 Students’ academic achievement requires the use of appropriate learning methods. Taking into consideration individual items to detect strengths and weaknesses, it was noted that students felt that teachers do not ridicule them, cheating is not a problem and they do not find the course disappointing.Citation37,Citation42

Concerning the eight negative statements, the students were in full agreement that the university programme organisers are authoritarian. These negative perceptions of the course organisers could be addressed with the interviews suggested previously and may lead to a greater awareness of what the students mean and how this can be improved. As regards social perceptions, they mentioned that they do not consider the atmosphere to be socially comfortable. These results emphasise the role of the staff who are responsible for doing their tasks efficiently, who should be patient with their students, show tolerance towards them and bear in mind students’ expectations.Citation39,Citation44

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that, overall, the educational environment was rated more positive than negative. Concerning the individual items, the perception of the social environment was the most defective domain while problems in the learning environment had a higher DREEM score among males. Greater efforts are needed to manage the negative items, which include the negative perception of teaching, the stressful environment and the lack of supportive strategies for stressed students.

This study is a brief descriptive study conducted with a group of final-year students. Despite the sample size, the study tried to evaluate the overall educational climate of the innovative approach to family medicine at SMU. Results from this study demonstrate that the course was perceived as a positive learning environment, contributing to the course objectives. This study highlighted strengths and weaknesses in the programme that could guide course organisers in modifying the course.

Limitations

Considering the nature of the course, which combines classroom-based learning with hospital/clinic-based teaching, DREEM does have some limitations in this context. Terms such as ‘course organiser’, ‘teachers’, ‘atmosphere’ and ‘learning/teaching’ present ambiguity in terms of whether the students perceived these as referring to a classroom- or hospital-based learning environment.

Another study with a larger sample size and data that are supported by qualitative data from in-depth interviews that specifically address the weak areas identified in this study would provide more information for the course organisers to enable them to optimise the finer details of the educational environment.

The number of students at various training sites could influence the total scores for the sites. More students per site would lead to more observations per site, and the weighting of the observations could be influenced either positively or negatively.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the students who voluntarily participated in this study and Mr Stevens Kgoebane for text-editing the document.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Al-Rukban MO, Khalil MS, Al-Zalabani A. Learning environment in medical schools adopting different educational strategies. Educ Res Rev. 2010;5(3):126–9.

- Till H. Climate studies: can students’ perceptions of the ideal educational environment be of use for institutional planning and resource utilization? Med Teach. 2005;27(4):332–7.

- Dreyer A, Gibbs A, Smalley S, et al. Clinical associate students’ perception of the educational environment at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2015;7(1):778.

- Harden RM. The learning environment and the curriculum. Med Teach. 2001;23(4):335–6.

- Veerapen K, McAleer S. Students’ perception of the learning environment in a distributed medical programme. Med Educ Online. 2010;15:5168.

- Genn JM. AMEE medical education guide no. 23 (part 1): curriculum, environment, climate, quality and change in medical education – a unifying perspective. Med Teach. 2001;23(4):337–44.

- Genn JM. AMEE medical education guide no. 23 (Part2): curriculum, environment, climate, quality and change in medical education – a unifying perspective. Med Teach. 2001;23(5):445–54.

- Vaughan B, Carter A, Macfarlane C, et al. The DREEM, part 1: measurement of the educational environment in an osteopathy teaching program. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:99.

- Roff S. The Dundee ready education environment measure (DREEM) – a generic instrument for measuring students’ perceptions of undergraduate health professions curricula. Med Teach. 2005;27(4):322–5.

- Pai PG, Menezes V, Srikanth, et al. Medical students’ perception of their educational environment. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(1):103–7.

- Taylor DC, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE guide no. 83. Med Teach. 2013;35(11):e1561–72.

- Soemantri D, Herrera C, Riquelme A. Measuring the educational environment in health professions studies: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2010;32:947–52.

- Thistlethwaite JE, Kidd MR, Hudson JN. General practice: a leading provider of medical student education in the 21st century? Med J Aust. 2007;187:124–8.

- Rabinowitz HK. Family medicine pre-doctoral education: 30-something. Fam Med. 2007;39:57–9.

- Dornan T, Muijtjens A, Graham J, et al. Manchester clinical placement index (MCPI). Conditions for medical students’ learning in hospital and community placements. Adv Health Sci Ed. 2012;17(5):703–16.

- Mowafy M, Zayed M, Eid N. The effect of family medicine programs’ educational environment on postgraduate medical students’ learning perceptions in Egypt. Egypt J Com Med. 2015;33(4):13–24.

- Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences. About us. Vison, mission and Motto. [cited 2018 February 15]. Available from: https://www.smu.ac.za/about-smu-sefako-makgatho-university/

- The Citizen. Students protest over safety at Sefako Makgatho Health Science University. [cited 2018 February 17]. Available from: https://citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/1998987/students-protest-over-safety-at-sefako-makgatho-health-science-university/

- De Villiers PJT. Becoming a family medicine specialist. S Afr Fam Pract. 2008;50(4):59.

- Mash B, Couper ID, Hugo J. Building consensus on clinical procedural skills for South African family medicine training using the Delphi technique. S Afr Fam Pract. 2006;48(10):59.

- Mash R, Reid S. Statement of consensus on family medicine in Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2010. [cited 2018 January 23]. Available at: http://www.phcfm.org/index.php/phcfm/article/view/151/53

- Harden RM, Sowden S, Dunn WR. Educational strategies in curriculum development: the SPICES model. Med Educ. 1984;18(4):284–97.

- Roff S, McAleer S, Ifere OS, et al. A global diagnostic tool for measuring the educational environment: comparing Nigeria and Nepal. Med Teach. 2001;23:378–82.

- Al-Hazimi A, Zaini R, Al-Hyiani A, et al. Educational environment in traditional and innovative medical schools: a study in four undergraduate medical schools. Edu Health. 2004;17(2):192–203.

- Khan AS, Akturk Z, Al-Megbil T. Evaluation of the learning environment for diploma in family medicine with the Dundee ready education environment (DREEM) inventory. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2010;7:2.

- Al-Ayed I, Sheikh S. Assessment of the educational environment at the college of medicine of King Saud University, Riyadh. East Mediter Health J. 2008;14(4):953–9.

- Alshehri SA, Alshehri AF, Erwin TD. Measuring the medical school educational environment: validating an approach from Saudi Arabia. Health Educ. J 2012;71(5):553–64.

- Al-Mohaimeed A. Perceptions of the educational environment of a new medical school, Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Sci Educ. 2013;7(2):150–9.

- Mojaddidi MA, Khoshhal KI, Habib F, et al. Reassessment of the undergraduate educational environment in the college of medicine, Taibah University, Almadinah Almunawwarah, Saudi Arabia. Med Teach. 2013;35(s1):S39–46.

- Brown T, Williams B, Lynch M. The Australian DREEM: evaluating student perceptions of academic learning environments within eight health science courses. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:94–101.

- Carmody DF, Jacques A, Denz-Penhey H, et al. Perceptions by medical students of their educational environment for obstetrics and gynaecology in metropolitan and rural teaching sites. Med Teach. 2009;31(12):e596–602.

- Dunne F, McAleer S, Roff S. Assessment of the undergraduate medical education environment in a large UK medical school. Health Educ J. 2006;65(2):149–58.

- Arzuman H, Yussoff MSB, Chit SP. Big Sib students’ perceptions of the educational environment at the school of medical sciences, University Sains Malaysia, using Dundee ready educational environment measure (DREEM) inventory. Malays J Med Sci. 2010;17(3):40–7.

- Pales J, Gual A, Escanero J, et al. Educational climate perception by preclinical and clinical medical students in five Spanish medical schools. Int J Med Educ. 2015;6:65–75.

- Mash R, Blitz J, Edwards J, et al. Training of workplace-based clinical trainers in family medicine, South Africa: before-and-after evaluation. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2018;10(1):a1589.

- Scheele F. The art of medical education. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2012;4(4):266–9.

- Aghamolaei T, Shirazi M, Dadgaran I, et al. Health students’ expectations of the ideal educational environment: a qualitative research. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2014;2(4):151–7.

- Palmgren PJ, Lindquist I, Sundberg T, et al. Exploring perceptions of the educational environment among undergraduate physiotherapy students. Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:135–46.

- Hamid B, Faroulah A, Mohammadhosein B. Nursing students’ perceptions of their educational environment based on DREEM model in an Iranian University. Malays J Med Sci. 2013;20(4):56–63.

- Roff S, McAleer S. What is educational climate? Med Teach. 2001;23(4):333–4.

- Babar MG, Hasan SS, Ooi YJ, et al. Perceived sources of stress among Malaysian dental students. Int J Med Educ. 2015;6:56–61.

- Bassaw B, Roff S, Mcaleer S, et al. Students’ perspectives on the educational environment, faculty of medical sciences, Trinidad. Med Teach. 2003;25(5),522–26.

- Murray B. The first African regional collaboration for emergency medicine resident education: the influence of a clinical rotation in Tanzania on Ethiopian emergency medicine residents. In partial fulfilment of the MPhil in Health Education. Stellenbosch University. 2017.

- Bouhaimed M, Thalib L, Doi S. Perception of the educational environment by medical students undergoing a curricular transition in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2009;18:204–8.