ABSTRACT

Introduction

Tuberculosis remains a major global health problem and ranks alongside the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as a leading cause of mortality worldwide. This study investigated the treatment outcome of tuberculosis and predictors of unsuccessful treatment outcome of tuberculosis (TB) patients enrolled in Arsi-Robe Hospital, central Ethiopia between January 2013 and December 2017.

Methods

An institution-based retrospective study was conducted on patients who had all forms of TB such as smear positive tuberculosis (PTB+), smear negative tuberculosis (PTB-), and extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) in the DOTS clinic. A multivariable logistic regression model was employed to identify predictors of unsuccessful treatment outcome and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Out of 257 registered TB patients, most were males (60%), rural residents (62.6%), new cases (69.6%), and HIV-negative (91.4%) and had pulmonary TB (80.2%). Regarding treatment outcome, 31.5% were cured, 52.5% completed their treatment, 5.1% defaulted, 5.8% died, and 5.1% had failed treatment. The overall successful treatment outcome and unsuccessful treatment outcome were 84% (87.9% males and 78.7% females) and 16% (21.1% males and 21.3% females), respectively. TB patients’ residence, age, treatment category, HIV-status and TB types were significantly associated with unsuccessful treatment outcome. TB patients from urban areas [AOR, adjusted odds ratio: 3.34, 95% CI (1.33–8.38)], within age of 45–54 years [AOR: 2.35, 95% CI (1.03–6.98)], those with failure treatment [AOR: 6.64, 95% CI (1.12–37.08)], and HIV-positive [AOR: 5.02, 95% CI (1.50–16.82)] patients had higher odds of unsuccessful TB treatment outcome. However, patients with PTB+ and EPTB had significantly lower odds of unsuccessful treatment outcome compared to patients with PTB-.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The treatment success rate is low as compared to the national treatment success rate. Public health facilities are advised to work on identifying factors of unsuccessful treatment outcomes through strengthened implementation of the DOTS strategy.

1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the top 10 causes of death and the leading cause from a single infectious agent; millions of people continue to fall sick with the disease worldwide each year [Citation1]. According to the WHO [Citation1], estimated 1.3 million (range, 1.2–1.4 million) deaths from TB among HIV-negative people and additional 300 000 deaths from TB among HIV-positive people were reported in 2017. At present, 1.7 billion (26%) of the world’s population are supposed to be infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis [Citation2], the bacterial pathogen causing the tuberculosis [Citation3].

Ninety-five percent of all TB cases and 99% of the deaths occur in developing countries, with the greatest burden in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia [Citation3]. A single TB patient with active disease, if not treated, was estimated to infect on average 10–15 people every year in sub-Saharan Africa [Citation4]. According to the 2018 WHO Global TB Report [Citation1], the prevalence of TB in Ethiopia was 164 per 100,000 population in 2017, with an annual mortality rate of 27.5 per 100,000 populations in 2017. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), smoking, diabetes, alcohol use, under-nutrition, use of immunosuppressive drugs, young age, socio-economic status, and behavioral aspects have been found to increase the susceptibility to TB infection [Citation4–6]. In Ethiopia, the reported high mortality rate among TB patients has been ascribed mainly to co-infection with HIV and the emergence of MDR M. tuberculosis strains [Citation7]. Retrospective studies conducted in different hospitals in Ethiopia showed human immunodeficiency virus as a strong determinant of treatment outcome of TB [Citation8–10].

A directly observed treatment short course therapy (DOTS) is a global strategy launched by the WHO for the prevention and control of TB. The DOTs program principally employs a direct observation of treatment approach where health professionals watch the patient taking each dose to ensure correct treatment and to take rapid action in case of need [Citation11]. In Ethiopia, the DOTS strategy was first implemented in the Arsi and Bale zones in 1992. It was subsequently scaled up and expanded to the national level [Citation7]. Currently, nearly all public, private, and non-governmental health facilities use the strategy [Citation12], but case detection and treatment outcomes vary across different regions of Ethiopia [Citation13]. Studies of treatment success rate (TSR) of smear-positive pulmonary TB in 25 districts of Arsi Zone in southern central Ethiopia from September 2004 to 2011 revealed treatment success rates ranging from 69.3% to 92.5%, but the TSR in Arsi-Robe District (82.4%) [Citation14], was still below the WHO TSR.

Factors in treatment outcome of TB are likely to vary depending on local demographic and socioeconomic settings. It was suggested that analysis of factors affecting treatment outcomes may help to improve the performance of DOTS services and provide useful evidence for decision-making in disease control programs [Citation15]. However, no study has assessed the treatment outcome and predictor factors of treatment outcome of TB in Arsi-Robe Hospital, central Ethiopia between January 2013 and December 2017. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first and most comprehensive study that specifically addressed the treatment outcome of TB and the predictors of unsuccessful treatment outcome under the DOTS strategy in this public hospital.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study setting and period

This study was conducted in Arsi-Robe Hospital, which is located in Arsi Administrative Zone, central Ethiopia, 226 km to the east of Addis Ababa. The hospital has a DOTS clinic which is operating under the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Program (NTLCP) [Citation12], under which the different types of TB were diagnosed.

2.2. Study design and study population

This study employed an institutional retrospective cohort design. The study employed records of all TB patients who were enrolled in the DOTS program from January 2013 to December 2017 in Arsi-Robe Hospital.

2.3. Inclusion criteria

Records of all types of tuberculosis (PTB+, PTB-, and EPTB) patients who were within the DOTS program at Arsi-Robe Hospital from January 2013 to December 2017 and having full records of treatment outcome were included in this study. Patients whose data of treatment outcomes were missing, who transferred to other health facilities, and who had multi-drug resistant TB were excluded from the study. Those cases that were undergoing TB treatment during data recording by the researchers were also excluded.

2.4. Sampling procedure and sample size

Arsi-Robe Hospital is the only healthy facility delivering TB treatment based on the DOTS scheme to inhabitants in Arsi-Robe town and to the surrounding people in the adjacent countryside. From a total of 315 cases of TB treatment, only 257 records of TB treatment fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the study.

2.5. Variables of the study

This study included unsuccessful TB treatment outcome (the sum of default, failure, and death) as a dependent variable, while socio-demographic variables (sex, age, and residence), clinical variables (weight, HIV status, types of TB treated, and TB patients’ treatment category), and year of treatment are the independent variables.

2.6. Diagnosis and treatment of TB patients

Arsi-Robe Hospital primarily employed acid-fast bacilli (AFB) for diagnosis of pulmonary TB and/or chest radiography for both pulmonary and EPTB. Culture and Xpert tests could be used for research purposes only. Therefore, the TB treatment outcome was determined using AFB and/or chest radiography results. Patients diagnosed with tuberculosis were treated following the guidelines specified by the Ethiopian FMoH National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Program (NTLCP) guidelines [Citation12].

2.7. Definition of terms

TB types, TB patients’ treatment category at entry, and definition of treatment outcomes were defined based on WHO definitions for treatment outcome [Citation1,Citation3,Citation6] and NTLCP guidelines of FMoH of Ethiopia for the diagnosis and treatment of TB cases [Citation12]. Types of TB treated were smear negative pulmonary TB [PTB-], smear-positive pulmonary TB [PTB+], and extrapulmonary TB [EPTB]. TB patients’ treatment category was new, relapsed, defaulted, failure, transfer-in, and other. Treatment outcomes were cured, treatment completed, treatment failure, defaulted, and died ().

Table 1. Definitions of TB types, treatment category and outcome of TB patients in DOTS program.

2.8. Data collection and quality assurance

Data for this research was abstracted from the DOTS unit TB register by trained nurses in Arsi-Robe Hospital. All available TB patient cards fulfilling the inclusion criteria were collected, and the information was retrieved based on a structured checklist prepared in English. Before data collection, one-day training on the process of data collection was provided by the investigators to data collectors (nurses) and supervisors in the hospital. In addition, records of 26 (10%) TB patients were abstracted in order to check the consistency and accuracy of data collection tools. The data collection process and completed datasets were supervised by both the investigators and the supervisors.

2.9. Data management and analysis

Data was checked for completeness, cleaned, and entered into a database using EpiData software version 3.1, and then exported to the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM. Corp., NY, USA). The results of this study were descriptively summarized in terms of frequency, percentages, tables, and figures. Bivariate logistic regression was used to analyze the association of each independent variable with unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB (dependent variable) for both sexes (male and female combined) and for each sex (male or female). Independent variables with a cut-point of P < 0.2 in bivariate analysis were exported into a multivariable logistic regression model to identify the final independent factors (predictors) associated with the dependent variable of patients with TB and the association was significant at P < 0.05.

2.10. Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance (Ref. No. CNCS/153/2018) was obtained by the ethics committee of the College of Natural and Computational Science, Madda Walabu University on July 20 2018. Permission letter to conduct the study was obtained from Arsi Zone Health Office to Arsi Robe Hospital administration.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of TB patients

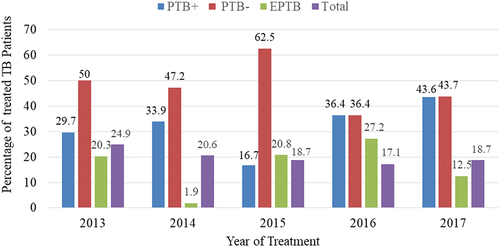

Male and female constituted 149 (60%) and 108 (42%) of the TB patients, respectively. A large number of TB patients were rural residents (62.6%). The mean age (± SD) and weight (± SD) of the TB patients were 27.63 ± 14.13 years and 45.51 ± 12.94 kg, respectively. Based on clinical characteristics, most of the TB patients were new cases (69.7%) and HIV-negative (91.4%). Based on TB types, 48.2%, 32.0%, and 19.8% of the TB patients were diagnosed for PTB-, PTB+, and EPTB, respectively (). The percentage of TB patients that participated in DOTs program generally decreased from the year 2013 to 2017. PTB+ showed an increasing pattern, but PTB- and EPTB showed an inconsistent decreasing and increasing trend across the year of treatment ().

Figure 1. Percentage of treatment of TB patients for different types of TB in Arsi-Robe Hospital, Ethiopia from January 2013 to December 2017.

Table 2. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of all TB patients enrolled in the DOTS program at Arsi-Robe Hospital, Ethiopia, January 2013 to December 2017 (n = 257).

3.2. Treatment outcome of TB in DOTS program

Among 257 TB patients who enrolled in the DOTS program in Arsi-Robe Hospital, 81 (31.5%) were cured and 135 (52.5%) completed their treatment. However, 13 (5.1%), 15 (5.8%), and 13 (5.1%) defaulted, died, and failure in their TB treatment outcome, respectively. The highest percentages of cured cases were recorded in TB patients who had PTB+ (93.9%). Treatment completion rate was higher in TB patients who were male (56.4%), age of ≤14 years (72.4%), transferred-in (62.5%), EPTB (84.3%), and HIV-negative (55.3%). The death rate was high in TB patients aged 45–54 (22.2%), HIV-positive patients (18.2%), and PTB- patients (18.9%) compared to their counterparts. TB patients who were HIV-positive (13.6%) had higher rates of treatment failure than its counterpart ().

Table 3. Treatment outcome of TB patients who received treatment for all forms of TB at Arsi-Robe Hospital, Ethiopia, January 2013 to December 2017 (n = 257).

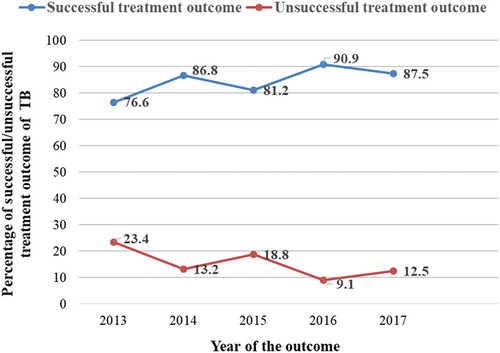

3.3. Prevalence of unsuccessful TB treatment outcome

Among TB patients enrolled in the DOTS program, the overall prevalence of successful TB treatment outcomes and unsuccessful TB treatment outcomes in Arsi-Robe Hospital were 84% (216/257) and 16% (41/257), respectively (). The percentage of unsuccessful treatment outcomes decreased from 23.4% in 2013 to 9.1% in the year 2016. However, there was a trend of an inconsistent decrease and increase from the year 2013 to 2017 ().

Figure 2. Trend of successful/unsuccessful treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients enrolled in DOTS program in Arsi-Robe Hospital, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 257).

Table 4. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses of factors associated with unsuccessful treatment outcomes for all forms of TB for both sexes at Arsi-Robe Hospital, Ethiopia, January 2013 to December 2017 (n = 257).

3.4. Predictors of unsuccessful treatment outcome of tuberculosis from both sex combined

In the bivariate analysis for both sexes, variables such as sex, residence, TB patients’ treatment category, HIV status, and types of TB were significantly associated with unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB (P < 0.05), but TB patients’ age groups and weight category produced P < 0.2. All these variables were fitted to the final model (multivariable logistic regression). In the final model, residence, age groups, TB patients’ treatment category, HIV status, and types of TB were significantly associated with unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB (P < 0.05) (). The likelihood of having unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB in both sexes residing in urban area was 2.63 times higher than TB patients residing in rural areas [AOR: 2.63, 95% CI (1.10–6.27)]. TB patients of both sexes within the age range of 45–54 years were 2.35 times more likely to have unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB compared to the patients with age ≤15 years [AOR: 2.35, 95% CI (1.03–6.98)] ().

TB patients with failure cases from both sexes were 6.46 times more likely to show unsuccessful treatment outcomes of TB compared to new cases [AOR: 6.64, 95% CI (1.12–37.08)] compared to new patients. HIV-positive TB patients from both sexes were 5.02 times more likely to have unsuccessful TB treatment outcome compared to HIV-negative TB patients [AOR: 5.02, 95% CI (1.50–16.82)]. TB patients from both sexes with PTB+ and EPTB were 85% times [AOR: 0.15, 95% CI (0.03–0.68)] and 81% times [AOR: 0.19, 95% CI (0.05–0.69)], respectively, less likely to experience unsuccessful treatment compared to PTB- patients ().

3.5. Predictors of unsuccessful TB treatment outcomes of male or female sex (each sex independently)

Male TB patients with HIV-positive were 12.34 times more likely to have unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB compared to male patients with HIV-negative result [AOR = 12.34, 95% CI (2.29, 66.37)]. Male patients with PTB+ and EPTB were 90% times [AOR = 0.10, 95% CI (0.01–0.95)] and 91% times [AOR = 0.09, 95% CI (0.014, 0.56)], respectively, less likely to have unsuccessful treatment outcome compared to male patients with PTB- ().

Table 5. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses of factors associated with unsuccessful treatment outcome in male or female TB patients at Arsi-Robe Hospital, Ethiopia, January 2013–December 2017 (n = 257).

Female TB patients from urban areas were about 3.32 times more likely to have unsuccessful TB treatment outcome compared to those who lived in rural areas [AOR = 3.32, 95% CI (1.03, 10.77)] (). Female TB patients within the age of 45–54 years were 1.53 times more likely to have unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB compared to age ≤14 years [AOR: 1.53, 95% CI (1.07–7.93)] (). Female TB patients with re about 4.13 times [AOR: 4.13, 95% CI (1.71–35.74)] more likely to experience failure treatment compared to new patients. Female TB patients with PTB+ were 88% times [AOR = 0.12, 95% CI (0.01, 0.78)] and those with EPTB were 94% times [AOR = 0.06, 95% CI (0.01, 0.6)] less likely to have an unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB compared to those having PTB- ().

4. Discussion

This study analyzes treatment outcomes and factors associated with unsuccessful treatment outcomes of TB cases treated at the DOTS Clinic of Arsi-Robe Hospital, Oromia Regional State, central Ethiopia, between January 2013 and December 2017. Evaluation of treatment outcome and associated factors for TB patients is of crucial importance in assessing the effectiveness of DOTS programs [Citation16].

In this study, the percentage of TB in males (60%) was higher than in females (42%), possibly due to males engagement in high TB risk professions [Citation17], or females underutilizing DOTS services as a result of various socioeconomic and cultural influences [Citation18]. The proportion of TB infection was invariably low in young patients (≤14 years) (), possibly due to bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine implementation in the Arsi-Robe Hospital. Ethiopia was one of the countries reporting between 50% and 89% coverage of the BCG vaccine in 2018 [Citation19]. The number of new TB patients was larger than those in the other TB treatment categories (). Similar results were reported by studies in Debre Tabor, northwest Ethiopia [Citation20]. The overall TB-HIV co-infection rate at Arsi-Robe Hospital was 8.6% (). This was lower than reported by studies in Ethiopia as a whole (29.4%) [Citation21] and in Kenya (41.8%) [Citation22]. Unavailability of HIV counseling and testing services, refusal of patients to be tested for HIV [Citation16] or low prevalence of HIV in the study population may contribute to lower TB-HIV co-infection rates [Citation23].

Regarding the treatment outcome of TB, there was a higher percentage of cured treatment outcome in PTB+ than other TB types. This could be due to a better DOTS implementation by the Arsi Robe Hospital and adherence of the TB patients to their DOTS treatment. TB patients who are not cured or non-adherent to their treatment present a challenge to effective TB control [Citation24]. The treatment failure rate (5.1%) in Arsi-Robe Hospital was higher than the rate in all forms of TB in Asella Teaching Hospital, central Ethiopia (0.2%) [Citation10]. Treatment failure was due to multidrug resistance tuberculosis (MDR-TB) development in previously treated TB cases [Citation25]. The overall death rate of TB patients in this study was recorded to be 5.8% and higher death rates were reported for TB patients who were older, HIV-positive, and had PTB- (). Higher death in older TB patients may be due to increasing comorbidities as well as the general immunological deterioration with age [Citation10,Citation26]. Dangisso et al. [Citation15] suggested that the higher proportion of deaths in PTB- cases might be due to diagnosis and treatment delays, as well as HIV infection among PTB- cases. TB patients who were HIV-positive experienced more defaults, death, and treatment failure than HIV-negative TB patients (), also reported by a study in Asella Referral Hospital [Citation10]. In TB-HIV co-infected patients, HIV constrains the effectiveness and success of TB treatment [Citation27].

The overall TSR of all forms of TB in this study was 84% () was lower than the global WHO target (>90%) and the targets for Ethiopia for new cases in the years 2016 (90%) [Citation1] and 2017 (96%) [Citation19], but it was higher than in Kenya (82.4%) [Citation28]. These variations may be due to variations in DOTs performance in different study areas, socio-economic status of patients, geographic settings, sample size, study periods, and TB management. In Arsi-Robe Hospital, PTB+ had the highest treatment success rate (95.1%) and was higher than the result in Bale Robe General Hospital (84.1%) [Citation9] and in Arsi Zone (83.6%) [Citation14]. Except for 2016 (90%), the TSR of TB in Arsi-Robe Hospital () was lower than that of the national treatment success rate in 2013 (91%) [Citation29], in 2014 (89%) [Citation6], in 2015 (84%) [Citation30], and in 2016 (90%) [Citation1].

In multivariable analysis for both sexes, TB patients residing in urban areas were more likely to have unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB compared to TB patients living in rural areas (), also reported in other studies in Ethiopia [Citation15,Citation20]. Comorbidities (HIV and diabetes mellitus), temporary interruption of treatment and addiction-related factors were suggested for poor treatment outcome of TB among urban residents [Citation20].

Patients with treatment failure had higher odds of significant unsuccessful treatment than new patients, corroborating studies in Ethiopia [Citation9,Citation20]. Previously treated TB cases (including failure) had multidrug resistance tuberculosis (MDR TB) [Citation11,Citation25,Citation31], and unsuccessful treatment outcomes [Citation10,Citation31]. TB patients of both sexes within the age of 45–54 years were more likely to experience unsuccessful treatment outcomes compared to patients in the age of ≤14 years (). This was in agreement with a study from Debre Tabor town, Northwestern Ethiopia [Citation16] and China [Citation32]. A highly unsuccessful TB treatment outcome in old TB patients is associated with co-infections with other diseases and general physiological deterioration [Citation10]. TB patients with HIV co-infections had higher odds of unsuccessful treatment than HIV-negative patients (). This was in agreement with the studies in Ethiopia [Citation9,Citation13,Citation14] and Malaysia [Citation33]. HIV/TB co-infection increases the risk of latent TB reactivation 20-fold, a well-known risk factor for the progression of M. tuberculosis infection to active disease [Citation34]. Co-administration of antiretroviral treatment along with anti-TB therapy can lead to drug interactions, overlapping drug toxicities, and immune reconstitution syndrome thereby reducing the treatment success rate in TB/HIV co-infected patients [Citation35].

In our study, TB patients with PTB+ and EPTB from both sexes were less likely to have unsuccessful treatment compared to PTB- patients (). Similarly studies from Ethiopia reported a highly successful treatment outcome of EPTB over both PTB- [Citation15] and PTB+ over PTB- [Citation36,Citation37]. A higher lost-to-follow up was observed among PTB- cases as compared to PTB+ [AOR: 1.14; CI 95%: 1.03–1.25] [Citation15]. The relatively high TSR of PTB+ rates in our study may also be due to improved diagnosis and good adherence to the DOTS program in the Arsi-Robe Hospital. Deployment of health extension workers who provide preventive and curative interventions against TB has been suggested for an increase in successful treatment outcome (cured and treatment completion) in Ethiopia [Citation38].

In a separate multivariable analysis, being male or female TB patients with EPTB and PTB+ were less likely to experience unsuccessful treatment outcome compared to male or female patients with PTB- (). In Male TB patients, similar results were also reported from East Gojjam, Ethiopia, although not reported for female patients [Citation37]. Male TB patients with HIV-positive results had a higher chance of having an unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB compared to HIV-negative TB patients (). This was supported by studies from east Gojjam, Ethiopia [Citation37] and elsewhere [Citation39]. According to Meseret et al. [Citation37], male TB patients with HIV-positive are more likely to die (due to HIV or TB) and treatment failure thereby experiencing highly unsuccessful treatment outcomes. However, this finding requires further exploration before a final conclusion can be made from this study.

Female TB patients from urban areas were more likely to experience unsuccessful treatment outcome compared to female TB patients from rural areas (). The high unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB in female TB patients in urban areas compared to rural areas may be due to a high rate of loss-to-follow-up in urban areas [Citation33], and/or economic and socio-cultural barriers. Female TB patients with a failed treatment category experienced a higher chance of unsuccessful treatment outcomes compared to new patients. A long duration between onset of symptoms to initiation of treatment in female rather than male [Citation40] and development of MDRT [Citation11,Citation31] might be attributed for a high chance of unsuccessful treatment outcome. The highly unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB in female patients of 45–54 years could be due to age-related diseases and comorbidities that impair the TB treatment [Citation10].

This study has the following limitations. The study was performed on a retrospective basis and used already registered socio-economic and clinical variables. Our study did not include registry on MDR-TB and on other means of diagnosis of TB such as Xpert and culture tests. Therefore, the conclusion of the results of our study and any interpretation of the results should consider the mentioned limitations. The pre-print of this study was found at https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-151177/v1 [Citation41] for the sake of visibility, readability, and seeking comments only. The current version of this paper has been, nevertheless, revised methodologically and scientifically.

5. Conclusions

There was a high proportion of PTB- patients over and PTB+ and EPTB patients, and a relatively low proportion of TB/HIV co-infection in Arsi-Robe Hospital. Cured cases were higher in PTB+ patients than other TB types, but death cases were higher in PTB- patients and in patients having HIV/TB co-infection. The overall prevalence of successful treatment outcome and unsuccessful treatment outcome of TB in Arsi-Robe Hospital was 84% and 16%, respectively. For both sexes (combined), residence, age groups, treatment category, HIV status, and TB types were the predictor variables for unsuccessful treatment outcome of tuberculosis in Arsi-Robe Hospital, Ethiopia. In male TB patients, HIV status, and TB types and in female TB patients residence, age groups, treatment categories and TB types were significantly associated with unsuccessful TB treatment outcomes of TB. Despite a low proportion of TB/HIV co-infection in the Hospital, it is important to strengthen the antiretroviral treatment of HIV coverage in order to reduce the morbidity and mortality due to TB. It is also essential to enhance the strategy of TB patients’ follow-up and tracing to keep them in contact with health professionals at service delivery point during treatment could increase the successfulness of TB treatment outcome. It is also important to study the relation of other socio-economic and clinical factors with treatment outcome in the study area and in other studies.

Authors’ contributions

Ararsa Girma and Addisu Assefa designed the study, prepared the proposal, supervised data collection, analyzed, and interpreted the data. Ararsa Girma and Addisu Assefa prepared the manuscript. Addisu Assefa and Helmut Kloos coached the overall process from proposal development to data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Madda Walabu University for facilitating the undertaking of this study. We are very grateful to Arsi Zonal Health Department and Arsi-Robe Hospital for their support in facilitating the data collection of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Addisu Assefa

Addisu Assefa (PhD), I was born on 14th of October, 1974 at Akasha Village in Ginnir district, Bale Zone, Southeastern Ethiopia. I completed my PhD study in Applied Microbiology at Addis Ababa University in July 2013. Currently, I am a teaching and research staff at Madda Walabu University (MWU), Bale Robe, Ethiopia. I published more than 20 articles in peer-reviewed and reputable journals with high impact factor. I have reviewed several manuscripts for various peer-reviewed and reputable journals. I am a member of professional organizations such as ASM, Ethiopian Society of Microbiology, and Biological Society of Ethiopia. Currently, I am an Associate Professor of Microbiology at Department Biology. I have been working as Dean of School of Graduate Studies of MWU since September 20, 2016. I am member of MWU Senate. I have been advising many masters and PhD students.

Ararsa Girma

Mr. Ararsa Girma (M.Sc, Lecturer), I was born on August 18, 1998 in Arsi Robe town, central Ethiopia. I completed my first degree at Ambo University in June 2020 and my second degree at Madda Walabu University in 2019. I worked my master’s study in a topic entitled as “Treatment outcome of tuberculosis (TB) and associated risk factors: a retrospective cohort study in Arsi Robe Hospital, Arsi zone, Ethiopia”. Currently, I am working as a lecturer.

Helmut Kloos

Helmut Kloos (PhD), I was formerly an associate professor in medical geography at Addis Ababa University, a visiting professor in the Universidade Federal in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, a consultant for the ministries of health in Kenya and Egypt, and is currently a Research Associate in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of California in San Francisco, USA. His research focused on the epidemiology of schistosomiasis and other water-related diseases, HIV/AIDS, and COVID-19, health services accessibility and utilization, traditional medicine, and the preparation of textbooks and bibliographies on public health in Ethiopia. He peer-reviewed articles such as Ethiopian Journal of Health Development, Ethiopian Medical Journal, Journal of the American Water Resources Association, PLoS Neglected Diseases.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis report 2018: document WHO/CDS/TB/2018.20. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018.

- Chakaya J, Khanc M, Ntoumi F, et al. Global Tuberculosis report 2020—reflections on the global TB burden, treatment and prevention efforts. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;113(Supplement 1):S7–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.107

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis report 2013: document WHO/HTM/TB/2013.11. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013.

- Castelnuovo B. A review of compliance to antituberculosis treatment and risk factors for defaulting treatment in Sub Saharan Africa. Afr Health Sci. 2010;10(4):320–324.

- Duarte R, Lönnroth K, Carvalho C, et al. Tuberculosis, social determinants and co-morbidities (including HIV). Pulmonol. 2018;24(2):115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.rppnen.2017.11.003

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis report 2016: document WHO/HTM/TB/2016.13; Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Ministry of Health of Ethiopia (MOH). Tuberculosis, leprosy and TB/HIV prevention and control programme manual 4. Addis Ababa. Ethiopia: MOH; 2008.

- Tachbele E, Taye B, Tulu B, et al. Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis patients at bale robe hospital Oromia regional state, Ethiopia: A five year retrospective study. J Nurs Care. 2017;6(2):386. doi: 10.4172/2167-1168.1000386

- Assefa A, Belete G, Helmut K. Factors associated with treatment outcome of tuberculosis in bale robe general hospital, Southeastern Ethiopia. A retrospective study. Gulhane Med J. 2022;64(2):178–188. doi: 10.4274/gulhane.galenos.2021.83703

- Tafess K, Beyen TK, Abera A, et al. Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis at Asella teaching hospital, Ethiopia: Ten years’ retrospective aggregated data. Front Med. 2018;5:38. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00038

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis report 2012: document WHO/HTM/TB/2012; Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. Guidelines for clinical and programmatic management of TB, TB/HIV and Leprosy. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa; 2012.

- Gebrezgabiher G, Romha G, Ejeta E, et al. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment short course and factors affecting outcome in Southern Ethiopia: A five-year retrospective study. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0150560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150560

- Hamusse SD, Demissie M, Teshome D, et al. Fifteen-year trend in treatment outcomes among patients with pulmonary smear-positive tuberculosis and its determinants in Arsi Zone, Central Ethiopia. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):25382. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25382

- Dangisso MH, Gemechu DG, Lindtjørn B, et al. Trends of tuberculosis case notification and treatment outcomes in the sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia: Ten-year retrospective trend analysis in urban-rural settings. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114225

- Melese A, Zeleke B, Ewnete B. Treatment outcome and associated factors among tuberculosis patients in Debre Tabor, Northwestern Ethiopia: A retrospective study. Tuber Res Treat. 2016;2016:1354356. doi: 10.1155/2016/1354356

- Narasimhan P, Wood J, Macintyre CR, et al. Risk factors for tuberculosis. Pulmon Med. 2013;2013:828939. doi: 10.1155/2013/828939

- Gafar MM, Nyazema NZ, Dambisya YM. Factors influencing treatment outcomes in tuberculosis patients in Limpopo province, South Africa, from 2006 to 2010: a retrospective study. Curationis. 2014;37(1):7. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v37i1.1169

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis report 2019: document WHO/CDS/TB/2019. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019.

- Melese A, Zeleke B. Factors associated with poor treatment outcome of tuberculosis in Debre Tabor, northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3129-8

- Ali SA, Mavundla TR, Fantu R, et al. Outcomes of TB treatment in HIV co-infected TB patients in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional analytic study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:640. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1967-3

- Nyamogoba DN, Mbuthia G, Mining S, et al. HIV co-infection with tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacteria in western Kenya: challenges in the diagnosis and management. Afr Health Sci. 2012;12(3):305–311. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v12i3.9

- Datiko DG, Yassin MA, Chekol LT, et al. The rate of TB-HIV co-infection depends on the prevalence of HIV infection in the community. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):266. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-266

- Dooley KE, Lahlou O, Ghali I, et al. Risk factors for tuberculosis treatment failure, default, or relapse and outcomes of retreatment in morocco. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):140. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-140

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control 2009: epidemiology, strategy, financing, document. WHO/HTM/TB/2009.411; Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2009.

- Caylà JA, Caminero JA, Rey R, et al. Current status of treatment completion and fatality among tuberculosis patients in Spain. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(4):458–464.

- Tola A, Mishore KM, Ayele Y, et al. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis and associated factors among TB-HIV co-infected patients at public Hospitals of Harar town, Eastern Ethiopia: A five year retrospective study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1658. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7980-x

- Mibei D, Kiarie J, Wairia A, et al. Treatment outcomes of drug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Kenya. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2016;20(11):1477–1482. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0915

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis report 2015: document WHO/HTM/TB/2015.22; Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015.

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis report 2017: document WHO/HTM/TB/2017.23; Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Assefa D, Seyoum B, Oljira L. Determinants of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2017;10:209–213. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S134369

- Wen Y, Zhang Z, Li X, et al. Treatment outcomes and factors affecting unsuccessful outcome among new pulmonary smear positive and negative tuberculosis patients in anqing, China: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3019-7

- Tok PSK, Liew SM, Wong LP, et al. Determinants of unsuccessful treatment outcomes and mortality among tuberculosis patients in Malaysia: a registry-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231986. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231986

- Getahun B, Ameni G, Medhin G, et al. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17(5):521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.12.010

- Narendran C, Padmapriyadarsini G, Swaminathan S. Diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in HIV co-infected patients. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134(6):850–865. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.92630

- Biruk M, Yimam B, Abrha H, et al. Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis and associated factors in an Ethiopian university hospital. Adv Public Health. 2016;2016:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2016/8504629

- Meseret M, Tizazua G, Temesgen H, et al. Successful tuberculosis treatment outcome in East Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: cross-sectional study design. Alexandria J Med. 2022;58(1):60–68. doi: 10.1080/20905068.2022.2090064

- Sebhatu A. The implementation of Ethiopia’s health extension program: an overview. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2008. Available from: https://www.phe490ethiopia.org/pdf/Health%20Extension%20Program%20in%20Ethiopia.pdf

- Murphy ME, Wills GH, Murthy S, et al. Gender differences in tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a post hoc analysis of the REMoxTB study. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):189. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1169-5

- Kapoor SK, Raman AV, Sachdeva KS, et al. How did the TB patients reach DOTS services in Delhi? A study of patient treatment-seeking Behavior. Public Library Of Science One. 2012;7(8):e42458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042458

- Assefa A, Girma A, Kloos H. Factors associated with unsuccessful treatment of tuberculosis in Arsi-Robe Hospital, Arsi Zone, Ethiopia: a retrospective study. [Pre-Print] https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-151177/v1