ABSTRACT

Introduction

Widespread use of effective and safe vaccines is the most promising method to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. This study aimed to assess the acceptance level of COVID-19 vaccination among the general population in six Middle East countries (Egypt, Jordan, Palestine, Tunisia, Sudan, and Yemen) as well as to assess factors associated with acceptance or refusal of vaccination.

Methods

A cross-sectional multinational study was conducted during the period from May 20 to August 8 2021. A web-based, self-administered, Google form Arabic questionnaire was used after a pilot study using 30 participants.

Results

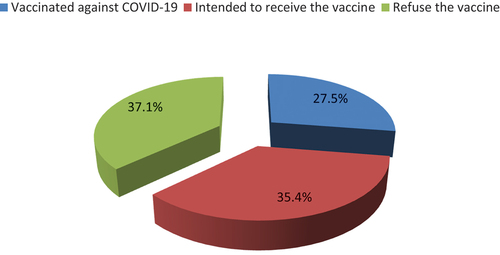

The COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate was 62.9%. The highest rate was reported among Tunisians (70%), while the lowest rate was detected among Egyptians (54.4%) and Yemenis (49%). Fear of side effects of vaccination was the main barrier to vaccination (53.1%). Meanwhile, nearly three-fifths (57.7%) of the respondents reported that vaccination would reduce the risk of infection. Logistic regression analysis stated that age >40 years, having children, being Health-Care Workers (HCWs), had higher education and higher income levels, and administering influenza vaccination were significant predictors of vaccine acceptance, as well as Jordanians, Palestinians, and Sudanese had higher probabilities of vaccine acceptance than Egyptians and Yemenis.

Conclusions

The acceptance rate was moderate. Fear of vaccine side effects and lack of receiving appropriate information were reported as barriers to vaccination. It is important to improve vaccine acceptance and reduce the barriers to COVID-19 vaccination.

1. Introduction

Nearly 2 years after the first identification of the virus causing COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2), many issues have changed. Our knowledge about how the virus spreads, and the impacts of the pandemic on all aspects of life have continued to evolve. Also, many variants of SARS-CoV2 have been detected; out of which four variants have been defined as variants of concern [Citation1]. Reducing the risk of exposure to the virus and the chance of its transmission through the application of evidence-based public health measures such as social distancing, masks, suspected case detection, and testing, tracing contacts, isolation of cases, and deployment of effective vaccines are the key to control over the pandemic [Citation1].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has approved several COVID-19 vaccines to prevent infection with SARS-CoV-2 [Citation2] that are considered the most promising method to reduce the likelihood of mutations and furthermore, end the pandemic [Citation3]. However, many concerns have emerged about people’s decision to receive these COVID-19 vaccines [Citation4].

Vaccination coverage rates show wide differences between Middle East countries. The highest rate was reported from Tunisia with an estimated rate of 56.4%. Jordan was in the second rank with vaccination coverage of 49.5% followed by Egypt (45.5%) and Palestine (39.9%). Sudan and Yemen were in the bottom of the list with vaccination coverage (9.6% and 1.5%, respectively) [Citation5].

Despite the availability of vaccines, there is a delay in acceptance or even refusal of vaccines; this is called vaccine hesitancy, which may be responsible for decreasing vaccine coverage [Citation6,Citation7]. Vaccine hesitancy is influenced by a variety of complex, context-specific factors, including convenience and access issues. However, concerns about vaccine safety due to its rapid development, the level of trust in the vaccine or provider, and the perception of no need for, or value of a vaccine are among the most commonly reported factors [Citation8,Citation9].

Hence, the current study aimed to assess the acceptance level of COVID-19 vaccination among the general population in the (Egypt, Jordan, Palestine, Tunisia, Sudan, and Yemen), as well as to identify socio-demographic factors associated with vaccine acceptance. The study also sought to ascertain barriers and facilitators related to vaccine refusal or acceptance.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

A cross-sectional multinational study was conducted during the period from May 20 to August 8 2021.

2.2. Study population and sampling

Participants aged 18 years and above who are the target group for COVID-19 vaccines in Arab countries at the time of the study were eligible to participate. Convenience techniques were used to distribute the Google form (questionnaire). Convenience sampling method is a non-probability sampling strategy in which choosing participants depends on how easily they can be reached by the investigators. The sample size of the study was calculated using Epi Info 7. A minimum sample size of 384 was calculated, assuming 50% as the prevalence of vaccine willingness with a confidence interval of 95% and precision of 5%. A sample size of 1500 was targeted from Egypt and Jordan and at least 400 from Tunisia, Sudan, Yemen, and Palestine.

Study instrument (questionnaire)

A web-based, self-administered, Google form Arabic questionnaire was formulated based on literature review [Citation9,Citation10–12] and discussion with the public. A pilot test (n = 30) was conducted to explore the clarity of the survey questions; the questionnaire form was subjected to editing (rewording, adding, and deleting some questions). Then, the questionnaire was taken by the investigators from different countries and distributed online through social media networks.

The questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first section collected information on respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, occupation, education level, income level, pregnancy for females, having a chronic disease). Sufficient income is the level of income needed to maintain the typical living standards in the socioeconomic class to which the household belongs [Citation13]. The second section included COVID and influenza vaccination status; for non-COVID 19 vaccinated respondents, we asked, “If any of the COVID-19 vaccines are available to you, would you be willing to take them”? The responses were yes, no, or hesitated.

The third section contained questions on barriers or facilitators affecting individual decisions regarding vaccination.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 22 (SPSS Inc, USA). Descriptive statistics were performed to summarize the basic characteristics of the study respondents, the estimate of vaccine acceptance proportion, and perceived barriers and facilitators to vaccine acceptance. For quantitative data, mean and standard deviation (SD) were computed. However, numbers and percentages were used to represent the qualitative data. The proportion of participants who had received the COVID-19 vaccine in the past or who were willing to get it was used to estimate the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance.

Inferential statistics were implemented to assess the relation between different characteristics and vaccine acceptance. Chi-square (χ2) test was performed as a statistical test of significance for the qualitative data. Adjusted odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) to estimate the likelihood of vaccine acceptance for different predictors were assessed using multiple logistic regression. Statistical significance was indicated at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Basic and other motivation characteristics

A total of 5394 questionnaires were analyzed. Most participants were in the age groups less than or equal to 40 years old 3365 (62.4%) with mean ± SD of 39.9 ± 9.8. Most participants were female 3512 (65.1%). Most of the study participants were married 3516 (65.2%). Most of the study population 3334 (61.8%) had children. Majority of the study participants 4278 (79.3%) were urban inhabitants. The majority of the survey participants 3564 (66.1%) had a sufficient income. Working participants constituted 3928 (72.8%) of the study sample. Most participants were highly educated either university graduates 3794 (70.4%) or postgraduates 1306 (24%). Health-care workers (HCW) made up nearly half of the participants 2928 (54.3%). More than one-third of participants were from Jordan (36.2%), followed by Egypt (28%) ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants (N = 5394).

About one-third of the study participants (35.8%) reported that they had previous COVID-19 infection with the highest infection rate among Jordanians (47.7%) and Yemenis (38%), while lower rates were reported among Tunisians (26%) and Sudanese (18.6%). Influenza vaccination coverage was 23.4%, with a significant difference between countries (p < 0.001); the highest influenza vaccination was reported among Tunisians (31%) and the least vaccination rates were in Sudan (14%) and Yemen (13%), .

Table 2. Vaccination history of study participants according to nationality (N = 5394).

3.2. COVID-19 vaccines acceptance

The participants were classified according to COVID-19 vaccination status into previously vaccinated participants against COVID-19 (27.5%), willing to take the vaccine (35.4%), and refusing the vaccination (37.1%). The overall COVID-19 vaccine acceptance proportion was 62.9%, . Regarding previous COVID-19 vaccination, the highest rates were reported among Palestinians and Tunisians (46.3% and 42.3%), and the lowest rate was recorded among Yemenis (9.4%). Among the unvaccinated, nearly half of the participants (48.9%) signified their willingness to receive vaccination with the highest proportions among Jordanians (52.4%), .

3.3. Barriers and facilitators to vaccine acceptance

Among those who had refused the vaccination, fear of side effects of vaccination was the main perceived barrier to vaccination (51.9%) with no statistically significant difference between countries (p = 0.177). Other perceived barriers were reported including the fear of the effect of some vaccines on genetic traits of humans (36.6%) and lack of providing information about vaccination (31.3%). In addition, several perceived beliefs that can give rise to the worries about vaccine effectiveness were highlighted. The most frequent beliefs were the doubt about the effectiveness of vaccination and its ability to boost immunity (44.8%), fear of contracting the disease despite vaccination (40.1%), and the possibility of contracting COVID-19 or its complications despite vaccination (35.4%). These opinions varied greatly between the surveyed nations ().

Table 3. (a): Factors against COVID-19 vaccination among refusing participants according to nationality (n = 2000): perceived susceptibility and complications and perceived benefit (concerns about vaccine effectiveness).

On the other hand, most respondents indicated that the vaccination would lower the risk of infection and its complications (57.7%), that everyone should get vaccinated (53.7%), and that the vaccination is effective and that it is feasible to raise immunity (42.6%). Tunisians were more likely to express these beliefs ().

Table 4. (a): Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance according to nationality among those accepted vaccination (n = 3394): perceived susceptibility and complications and perceived benefit.

3.4. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance

depicts the relationship between vaccine acceptance and possible associated factors. The percentage of vaccine acceptance was higher among males than females (64.9% vs. 61.8%, P = 0.025). It was also higher among respondents belonging to age groups >40 years old, in urban residence, those with higher education levels, and those with higher income level. Married respondents, those had children and non-pregnant females, reported higher level of vaccine acceptance.

Table 5. Relationship between respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics and vaccine acceptance.

When comparing vaccine acceptance rates across different nationalities, the highest rate for vaccine acceptance was reported among Tunisians (70.4%) and Jordanians (67%), while the lowest rate was detected among Egyptians (54.4%) and Yemenis (49.2%) (P = 0.001). Vaccine acceptance was higher among influenza vaccinated participants and respondents who had not been previously infected with COVID-19 (p values < 0.001) ().

According to multiple logistic regression analysis, being more than 40 years old, those living in urban places, being HCW, having a higher education and income levels, and receiving influenza vaccination were significant predictors for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. However, having chronic diseases, being pregnant and previously infected with COVID-19 were associated with a low probability of vaccine acceptance. Regarding nationalities, Jordanians, Palestinians, Sudanese, and Tunisians had higher probabilities of vaccine acceptance than Egyptians: on the other hand, Yemenis had the lowest probability of vaccine acceptance ().

Table 6. Factors associated with vaccine acceptance among participants.

4. Discussion

The current study attempts to bridge the knowledge gap about COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in a set of Arab countries. It also identified the perceived facilitators and barriers of the participants to accept or refuse the vaccine. Higher vaccination rates and establishing herd immunity are the most important long-term preventive measure against COVID-19 infection. Our findings revealed variable but broadly moderate levels of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across countries. More than 62% of our participants had accepted the vaccine with the highest level of vaccine acceptance in Tunisia (70%) followed by Jordan, and Palestine. The lowest acceptance rate was reported from Yemen (49.2%). This manner of difference between the studied countries was in agreement with the reported vaccination coverage rates as the highest rate was reported from Tunisia with an estimated rate of 56.4%. Jordan comes in the second rank with vaccination coverage of 49.5% followed by Egypt (45.5%) and Palestine (39.9%). Sudan and Yemen had the lowest rates with vaccination coverage of (9.6% and 1.5% respectively) [Citation5].

Our findings disagree with the results of another study including several Middle East countries which reported that 80% of the adult Arabs were opposing COVID-19 vaccination [Citation10]. Also in a previous study conducted in Egypt, only 25% had decided to take the vaccine [Citation11], while in a study carried out in Saudi Arabia, 44.7% of the respondents had decided to receive the vaccine [Citation12].

This research showed that half of the non-vaccinated respondents had reported their willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination. This is comparable to the finding of a study conducted among adult Hungarians, which found that 48.2% of the population was willing to get the vaccine [Citation14] but it was lower than the reported results in the study carried out in the USA (56.0–68.6%) [Citation15]. It was also lower than in some European countries such as Italy (56.6%), Greece (57.7%), Finland (72.9%), France (76.0–77.6%), and the United Kingdom (83%) [Citation16,Citation17–20]. The difference between countries in accepting the vaccine was attributed to the level of trust in the information from governmental sources and the availability of such information [Citation21].

Fear of the vaccine side effects was the principal reason for refusing the vaccine. Lack of trust in the vaccine efficacy was also perceived as a barrier for refusal. This is compatible with a previous Egyptian study that found more than half of the participants had a high level of worry about unexpected side effects of the vaccine and almost two-thirds had no trust in the vaccine’s benefits [Citation11]. Other study conducted among Egyptian health-care workers stated that more than half of the respondents have concerns about its safety and one-fifth have concerns about efficacy and fear of gene mutations [Citation22]. Also, Qunaibi et al. found that fear of the potential side effects to be the most important reason for indecision about the vaccine [Citation10]. Furthermore, most adult Saudi population had reported their concerns about the vaccine side effects [Citation12]. Likewise, Dombrádi et al. emphasized the association between vaccine refusal and uncertainty and negative beliefs, while vaccine acceptance was associated with holding positive beliefs [Citation14]. This necessitates conduction of continuous awareness campaigns emphasizing the safety of all the available vaccines.

In our study, nearly half reported the importance of the vaccination in reducing the risk of the infection. This comes in agreement with a previous systematic review conducted by Bish et al. who reported that participant positive attitudes toward H1N1 vaccination were strongly associated with receiving the vaccine [Citation23]. Also, Magadmi & Kamel in a study conducted in Saudi Arabia stated the importance of the respondents’ beliefs as a significant predictor for acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination [Citation12].

Vaccine acceptance or refusal was found to be associated with several factors that may differ between different settings [Citation4,Citation24,Citation25]. Like other previous studies, we found that males were more likely to accept the vaccine than females [Citation10,Citation11,Citation14,Citation26]. On the other hand, we found that pregnant or lactating females were a significant predictor of vaccine refusal. As well as, people over the age of 40 were found to be more likely to accept vaccines. This is consistent with other studies in which older age groups are more likely to accept the vaccine [Citation10,Citation17,Citation27]. This may be due to the aging population has been at more risk making them more willing to get the vaccine contrary to the younger population who survived the SARS-CoV-2 infection with light symptoms or no symptoms [Citation14].

The effect of the educational level on the willingness to get the vaccine is not clear across the different studies. We found that the high education level was a significant predictor for accepting the vaccine. These findings were in accord with previous research findings [Citation12,Citation14,Citation26,Citation28]. According to other reporting, education was found to have no significant effect on the vaccine acceptance [Citation11,Citation19,Citation29,Citation30].

In terms of influenza vaccination, our research has reported that receiving influenza vaccination was a significant predictor for vaccine acceptance. This finding was in agreement with Magadmi & Kamel and Dombrádi et al., who stated that receiving the influenza vaccine was a significant predictor of accepting COVID-19 vaccination [Citation12,Citation14]. Also, Omar and Hani reported that having influenza vaccination was associated with hesitancy about COVID-19 vaccine [Citation11].

4.1. Strengths and limitations of the study

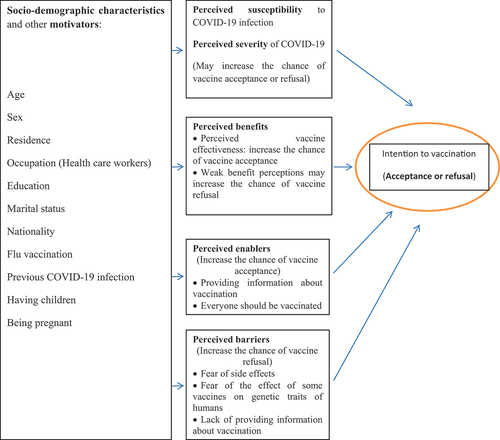

The main study strength is the identification of the factors that could influence the chance of COVID-19 vaccine refusal and acceptance. Although some studies address this issue in Arab countries [Citation10,Citation31], in our results we tried to find the differences in these factors across the studied countries. Additionally, we summarized our findings in the context of the conceptual framework proposed by Burke et al., 2021 after making some modifications [Citation32] in order to demonstrate how the study can contribute to the existing knowledge and furthurmore to design behvious change interventions, . As regards limitations, this study relied on an online questionnaire with using a convenience sampling technique which may affect the generalizability of the results to the population. Certain groups are less likely to have internet access and respond to online questionnaires. On the other hand, some occupations, such as health-care workers, are overrepresented because they are more likely to have internet access and thus have a higher chance of receiving the questionnaire.

4.2. Conclusions and recommendations

The COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate in the countries studied was moderate, except for Yemen, which revealed the lowest rate. Fear of vaccine side effects and lack of the providing the appropriate information about the vaccines were the most reported perceived barriers to vaccination. It is important to improve vaccine acceptance and reduce these barriers to COVID-19 vaccination through providing the population in our countries by the adequate information via mass media and vaccination campaigns aiming at instilling trust in vaccine safety and effectiveness. On the other hand, the study participants’ adoption of the vaccine was significantly influenced by their positive benefit perception.

4.3. Ethical approval and consent to participate

The current study was approved by Research Ethical Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Fayoum University.

Author contribution

MS: put proposal plan, prepared the study tool, and searched the literature, shared in data analysis and presentation, shared in writing the draft of the manuscript and submitting the paper. WYA: put research plan, performed analysis and data interpretation, wrote manuscript, final drafting of manuscript. RH: selected research topic, data collection, edited and reviewed data and all analysis done. NSH: wrote the manuscript, shared in final drafting and revision of the manuscript. MI, FM, NA, AZ, LA, collection of data, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge our participants for being a part of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohamed Masoud

Mohamed Masoud Associate Professor of Public health & Community medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Fayoum University, Fayoum, Egypt.

Rasha Hammed Bassyouni

Rasha Hammed Bassyouni Professor of Medical Microbiology and Immunology Department, faculty of Medicine , Fayoum University, Fayoum, Egypt.

Wafaa Yousif Abdel-Wahed

Wafaa Yousif Abdel-Wahed Professor of Public health & Community medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Fayoum University, Fayoum, Egypt.

Mohammed Ibrahim Al Hawamdeh

Mohammed Ibrahim Al Hawamdeh General director of Jordanian Experts for training – Jordan Fadi Mohammad Nassar Supervisor at Rafidya Surgical Hospital – MOH, Palestine.

Fadi Mohammad Nassar

Fadi Mohammad Nassar Supervisor at Rafidya Surgical Hospital – MOH, Palestine.

Nahla Arishi

Nahla Arishi National Emergency Coordinator in Ministry of public health, Yemen.

Anez Ziad

Anez Ziad Director of Preventive Health, Ministry of Health, Tunisia.

Lubna Abdelwahab Elsidig

Lubna Abdelwahab Elsidig General Directorate of Quality, Development and Accreditation, Federal Ministry of Health, Sudan.

Nashwa Sayed Hamed

Nashwa Sayed Hamed Lecturer of Public health & Community medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Fayoum University, Fayoum, Egypt.

References

- World Health Organization. Critical preparedness, readiness and response actions for COVID-19: interim guidance, 27 May 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/341520. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

- World Health Organization. 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-race-for-a-covid-19-vaccine-explained [Accessed 2 Dec 2021].

- Krause PR, Fleming TR, Longini IM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants and vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(2):179–186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr2105280

- Machingaidze S, Wiysonge CS. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Nature Med. 2021;27(8):1338–1339. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01459-7

- Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, et al. coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19).2020. 2Dec 2020. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

- Trogen B, Pirofski L. Understanding vaccine hesitancy in COVID-19. Med. 2021;2(5):498–501. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2021.04.002

- Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763–1773. doi: 10.4161/hv.24657

- Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160

- Murphy J, Vallières F, Bentall RP, et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun. 2021 Jan 4;12(1):29. PMID: 33397962; PMCID: PMC7782692. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9.

- Qunaibi EA, Helmy M, Basheti I, et al. A high rate of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a large-scale survey on Arabs. Elife. 2021 May 27;10:e68038. PMID: 34042047; PMCID: PMC8205489. doi: 10.7554/eLife.68038

- Omar DI, Hani BM. Attitudes and intentions towards COVID-19 vaccines and associated factors among Egyptian adults. J Infect Public Health. 2021;S1876-0341(21):00185–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2021.06.019

- Magadmi RM, Kamel FO. Beliefs and barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccination among the general population in Saudi Arabia. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1438. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11501-5

- Tabbarah RB. The adequacy of income: a social dimension in economic development. J Dev Stud. 2007;8(3):57–75. doi: 10.1080/00220387208421412

- Dombrádi V, Joó T, Palla G, et al. Comparison of hesitancy between COVID-19 and seasonal influenza vaccinations within the general Hungarian population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021 Dec 23;21(1): 2317. PMID: 34949176; PMCID: PMC8697540. 10.1186/s12889-021-12386-0.

- Pogue K, Jensen JL, Stancil CK, et al. Influences on attitudes regarding potential COVID-19 vaccination in the United States. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(4):582. doi: 10.3390/vacci.nes80.40582

- Graffigna G, Palamenghi L, Boccia S, et al. Relationship between citizens’ health engagement and intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine in Italy: a mediation analysis. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(4):576. doi: 10.3390/vaccines80.40576

- Kourlaba G, Kourkouni E, Maistreli S, et al. Willingness of Greek general population to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Glob Health Res Policy. 2021;6(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s41256-021-00188-1

- Karlsson LC, Soveri A, Lewandowsky S, et al. Fearing the disease or the vaccine: the case of COVID-19. Personal Individ Differ. 2021;172:110590. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110590

- Ward JK, Alleaume C, Peretti-Watel P, et al. The French public’s attitudes to a future COVID-19 vaccine: the politicization of a public health issue. Soc Sci Med. 2020;265:113414. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113414

- Salali GD, Uysal MS. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychol Med. 2020;1–3. doi: 10.1017/S0033.29172.00040.67

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225–228. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9

- Aliaë MH, Islam GS, Makhlouf N, et al. A national survey of potential acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines in healthcare workers in Egypt. medRxiv. 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.01.11.21249324.

- Bish A, Yardley L, Nicoll A, et al. Factors associated with uptake of vaccination against pandemic influenza: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2011;29(38):6472–6484. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.107

- Reiter PL, Pennell ML, Katz ML. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: how many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 2020 Sep 29;38(42):6500–6507. Epub 2020 Aug 20. PMID: 32863069; PMCID: PMC7440153. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043

- Arce IS, Warren SS, Meriggi NF, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low and middle income countries, and implications for messaging. medRxiv. 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.03.11.21253419

- Sallam M, Dababseh D, Eid H, et al. High rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its association with conspiracy beliefs: a study in Jordan and Kuwait among other Arab countries. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):42. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010042

- Dodd RH, Cvejic E, Bonner C, et al. Sydney health literacy lab COVID-19 group. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 in Australia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(3):318–319. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30559-4

- Ogilvie GS, Gordon S, Smith LW, et al. Intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine: results from a population-based survey in Canada. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1017. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11098-9

- Mohamad O, Zamlout A, AlKhoury N, et al. Factors associated with the intention of Syrian adult population to accept COVID-19 vaccination: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1310. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11361-z

- Syed Alwi SAR, Rafidah E, Zurraini A, et al. A survey on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and concern among Malaysians. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1129. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11071-6

- Walid AA-Q, Anan SJ. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance and its associated factors among a middle eastern population front. Public Health. 2021;9:632914. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.632914

- Burke PF, Masters D, Massey G. Enablers and barriers to COVID-19 vaccine uptake: an international study of perceptions and intentions. Vaccine. 2021 Aug 23;39(36):5116–5128. Epub 2021 Jul 23. PMID: 34340856; PMCID: PMC8299222. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.056