?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Background

A stool color card has improved the prognosis of biliary atresia patients since it was first developed in Japan. This study investigated how Sudanese pediatric residents currently utilize stool color cards.

Methods

In January and February of 2022, 254 pediatric residents participated in this facility-based, cross-sectional study. The researchers developed a structured questionnaire, which was completed in Google form with a 100% response rate after it was pretested and validated. All the statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 25.0 (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL). The ethical committee of the Sudan Medical Specialization Board approved the study. All participants provided written informed consent.

Results

A total of 254 residents, ranging in age from 25 to 40 years, were enrolled in the study; 215 of whom were female (84.6%), and 39 were male (15.4%). Approximately 54.7% of the residents did not know about SCC. Of those who knew of SCC, 73% were proficient users. 71% of the participants properly identified the first three normal photographs of stool color out of the six photos in the SSC example. Nevertheless, only 13% of the participants correctly identified the final three abnormal images. The majority of residents (84.6%) were aware of when to send patients to gastroenterologists. At least one prereferral investigation was ordered by 83.8% of the residents.

Conclusion

The residents’ knowledge was unrelated to their practices. Educational interventions as well as practice protocols and guidelines are needed. More in-depth research with suitable designs and methodologies may offer additional clarity in the future.

1. Introduction

The main cause of cholestasis in newborns is a rare condition called biliary atresia (BA), which progresses over time. On the other hand, hepatic failure and fibrosis can occur if they are not identified and treated in a timely manner, ultimately resulting in early childhood death [Citation1]. The etiology of this illness is unclear, as it originates from large bile duct damage that scleroses quickly and completely, blocking all bile flow [Citation2]. BA typically appears in the first few weeks of life as jaundice and pale stools, and the prevalence of BA varies between nations [Citation3]. In contrast to the majority of benign, unconjugated cases of newborn hyperbilirubinemia, BA causes conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. The typical course of treatment for BA is hepatic portoenterostomy (also known as Kasai surgery), followed by liver transplantation when liver failure develops [Citation4].

The infant’s age at the time of the procedure is the most significant predictor of a successful Kasai procedure. The best results are obtained when the intervention is carried out at or before 30 days of age [Citation3]. Common problems with BA include delayed diagnosis, late referral, and untimely surgery [Citation3].

While it appears to be subjective, educating parents and healthcare professionals on the symptoms of neonatal liver disease (such as jaundice and stool color) can aid in the early diagnosis of neonatal cholestasis, including cases of BA [Citation5–7]. Furthermore, evaluating stool color is not a normal part of “well-baby” care, and parents and healthcare professionals do not typically check for pale stools, particularly in newborns who are jaundiced. Additionally, healthcare professionals have a limited understanding of the significance of early BA identification [Citation4]. Therefore, screening for BA more successfully can be performed using an objective tool such as a stool color card (SCC) [Citation6,Citation7].

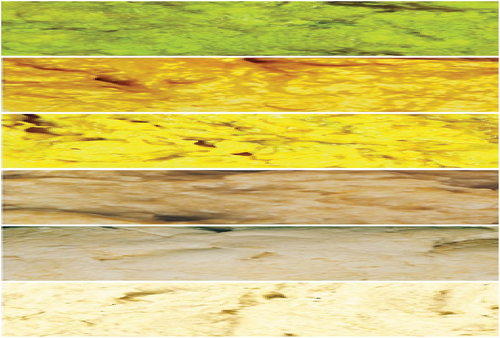

The concept of SCC is straightforward: it consists of five to seven images () showing a variety of stool colors arranged from normal to abnormal. It is given to infants’ parents and guardians during prenatal or postpartum care, and they are instructed to contact the local hospital if they notice an unusual color in the kid’s stool [Citation8].

Figure 1. A stool colour card example. Shown are six images (descending from above: the first three tree photos show a normal stool color, while the next three photos show an abnormal stool color) that were produced with approval from Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health, Taiwan, and professor Mei Hwei Chang, College of medicine, National taiwan university.

Since its initial introduction in Japan in 1994 [Citation8], a number of SCC government-led mandated programs have been established in Taiwan, Chinese provinces, and Switzerland, while voluntary programs have been implemented in Canada, Italy, and Portugal [Citation9–14]. Various studies indicate that despite variations in the regional incidence of BA, SCC screening programs not only enhance BA outcomes (such as reduced hospitalization rates, earlier surgical intervention, improved survival with native liver, and decreased number of transplants) but also prove to be an efficient approach in terms of healthcare costs [Citation7,Citation15–17].

Financial constraints may prevent children with prolonged jaundice (who appear well overall) from receiving additional medical workup, including laboratory and imaging tests, in underdeveloped nations. Hence, employing an SCC to raise suspicions about BA patients will be an affordable strategy that ensures early referral to specialized centers. The successful implementation of screening programs that involve SCC is heavily dependent on the understanding of the concept by physicians and parents. SCC has been shown to be an effective, easy, sensitive, specific, and adaptable approach for the early identification of BA, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [Citation18].

The use of the SCC card by pediatric residents in Sudan for treating infants with cholestatic jaundice and when to promptly refer the child to a gastroenterologist are unknown. Therefore, we set out to accomplish this goal because there is no nationwide published study on pediatric residents’ awareness and use of infant SCC.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and setting

This was a descriptive cross-sectional office-based study led between January and February 2022. The study was carried out at the Pediatric Council of the Sudan Medical Specialization Board (SMSB). By Presidential Decree, the SMSB was established in 1995 in accordance with the Sudan Medical Specialization Act of 1995. The SMSB is tasked with managing and carrying out the republic’s medical and health specialist programs. When trainees finish their four-year residency program, the Pediatric Council of the SMSB awards them a clinical medical doctorate (MD) degree for pediatrics and child health. The holder of the doctor’s license is qualified to practice general pediatrics as a specialist.

2.2. Study population and eligibility criteria

Eighteen Sudanese states were home to pediatric residents enrolled in the Sudan Medical Specialization Board training program. The pediatric council secretary reported that the 746 pediatric residents in the SMSB were split into four batches, ranging from resident (R) year 1 to year 4. Those who had just begun their residency program and had not yet completed their clinical rotation were included. Individuals who had taken their yearly vacations of absence from work, sick leave or maternity leave were not included.

2.3. Sample size determination and sampling technique

With the following assumptions: n = sample size, N = population size, p = probability, z = 95% confidence interval (1.96), d = error proportion (0.05), the Stephen–Thompson formula was used to determine the total sample size (254).

Study participants were chosen by simple random sampling; residents assigned to the study were contacted individually; and the total number of residents was distributed proportionately based on their residency year (from R1 most junior to R4 most senior).

2.4. Data collection tool

The researchers developed a questionnaire specifically for this study, which was pretested on eight pediatric residents who were not included in the final sample size calculation and was verified by three physicians who are also medical educators. The 15 closed-ended questions on the questionnaire recorded the demographic characteristics of the residents (three items) and evaluated their knowledge (six items) and practices (six items) on stool color cards. Every resident involved in the study was contacted individually. The survey was sent by e-mail or via WhatsApp as a Google form in English.

2.5. Data analysis

Microsoft Excel files were transferred to a computer for analysis using IBM SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). The normality of the distribution was confirmed using the Shapiro‒Wilk test. For qualitative data, percentages (%) and frequencies (N) were calculated. Standard deviations (SDs) and means are used to describe the quantitative data. After that, the data are shown in tables and charts. Chi-square analysis was used to identify various correlations between variables. The importance of the findings at a p value of less than 0.05.

2.6. Ethical consideration

The SMSB Ethics Committee and the Pediatrics Council approved the study. All participants provided informed consent following a thorough explanation of the study’s objectives in the first section of Google Forms.

3. Results

The understanding and utilization of the newborn stool color card were assessed among the pediatric residents of the Sudan Medical Specialization Board in this study.

3.1. Participant characteristics

For the study, 254 residents were enrolled, representing various residency program batches from R1 to R4; 215 females (84.6%) and 39 males (15.4%) were included, and the ages ranged from 25 to 40 years.

3.2. Participants’ knowledge of the SCC concept in BA case diagnosis

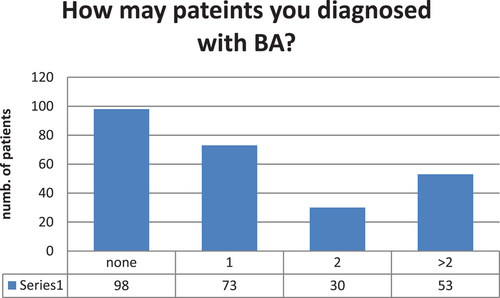

According to the overall response of the residents, 156 (61.4%) of the residents were able to diagnosed new cases of BA. However, up to the time of this study, 98 (38.5%) of the residents had never received a diagnosis of biliary atresia. .

Only 115 (45%) of the residents knew the SCC concept in the diagnosis of BA, and approximately 58 (50%) of them knew it in their last residency year, according to the particular response of the residents regarding their knowledge about stool color cards as a screening or diagnostic tool for biliary atresia. .

Table 1. Pediatric residents’ perceptions and knowledge of the stool color card.

3.3. Participant’s usage of the SCC for BA case diagnosis

Eighty-four (73%) of the 115 residents who were familiar with the SCC concept were also competent at using it in clinical practice.

Only 32 (12.6%) of the residents accurately identified the truly abnormal photographs (photos 4, 5, and 6) in their response to a real practice example of the six-photos stool color card provided to them. .

Table 2. Current pediatric residents’ practices regarding stool color cards.

According to participant responses about the management and referral of suspected BA patients, 215 (84.6%) residents generally understood when to refer suspicious patients to gastroenterologists, and 213 (83.8%) ordered at least one prereferral investigation (). As the conventional treatment for BA, 134 (52.7%) patients chose the Kasai procedure ± liver transplantation later in life.

Table 3. Residents’ perceptions of the prereferral investigations.

4. Discussion

To improve the native liver survival rate, decrease the need for liver transplantation, and improve the success rate of the Kasai procedure, early detection of BA is crucial. Clearly, a crucial part of reaching this goal is screening. Additionally, as demonstrated by comparing the direct medical costs of hospitalizations before and after the implementation of the SCC screening program in Shenzhen in 2015, early detection also shortens the duration of hospitalization and lowers medical costs, which lessens the burden on guardians [Citation19]. The stool color card is an easy-to-use, practical, effective, and crucial tool for identifying and diagnosing biliary atresia cases early on. The purpose of this study was to determine how Sudanese pediatric residents feel about stool color cards as a screening method for biliary atresia.

The findings of our study point to a general knowledge gap regarding SCC. The stool color card was unknown to 139 residents, or nearly half (54.7%) of the total. This is similar to the findings of a Chinese study that included 200 pediatricians; 52% had never heard of SCC [Citation17]. Additionally, this finding is similar to that of a study conducted in Egypt, which revealed that nearly all of the referring doctors for the 108 infants included did not know about the SCC concept [Citation18]. Therefore, providing pediatric residents with professional development opportunities (such as workshops and sessions) is crucial to improving the situation.

Of the six SCC example photographs that the residents were shown, only 32 (12.5%) properly identified the later abnormal stool color photos, while the remaining 182 (71.6%) correctly identified the first three normal stool color photos. In contrast, a study conducted in the Netherlands among general practitioners and youth physicians revealed that 61% of youth healthcare doctors correctly classified all discolored stools as “abnormal,” while 18% of them correctly classified all colored stools as “normal.” Among all the general practitioners, 22% correctly identified all 10 photos correctly, and 36% correctly identified all the discolored stools as “abnormal” [Citation20]. Thus, gathering and evaluating the perspectives of Sudanese pediatric residents regarding SCC could aid in addressing these challenges and offer practical options that could assist them in identifying cases of biliary atresia early on.

Because BA is still a very uncommon illness for the majority of babies in Sudan, screening resources for both financial and human use are limited. Moreover, parents/guardians typically send their babies to many pediatricians and primary care doctors, who are not always able to identify BA. Thus, healthcare facilities actually waste too much money and time. The results of this study serve as a baseline for subsequent office-based research projects that will be necessary to solve common issues and maximize the advantages of using this kind of screening tool in clinical settings.

5. Recommendations

Implementing the global best guidelines and/or developing local practices for the early screening and diagnosis of biliary atresia.

To improve health, pediatricians’ knowledge of SCC must increase through a variety of medical initiatives (workshops, clinical audits, etc.).

Evidence-based strategies for managing the difficulties associated with SCC may be useful in assisting pediatricians in making an early diagnosis of biliary atresia.

6. Conclusion

This is the first study to evaluate Sudanese doctors’ practices and knowledge of infant stool color cards. The results showed that the stool color cards used were poorly understood. The knowledge gained from this study will be useful in prioritizing communication regarding newborn stool color cards and guiding future better design.

7. Limitations

The cross-sectional study design and methodology are constrained by the data collected on residents’ self-reported use of stool color cards. As a result of the formal questionnaire design, residents’ practice responses may be biased toward an overestimation of their activities. Furthermore, the replies gathered may present a positive picture of the behavior that the residents recommended. However, future research utilizing a suitable study design and methodology will need to concentrate on examining pediatricians’ usage of SSC.

Abbreviations

| BA | = | biliary atresia |

| SCC | = | Stool color card |

| SMSB | = | Sudan medical specialization board |

| R1-R4 | = | Number of years of residence in the training program |

| HPA | = | Health Promotion Administration |

Availability of data and material

The corresponding author can supply the data utilized and/or analyzed for this work upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express to their gratitude to all the residents who participated in this research. Acknowledgement to the Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health,Taiwan, and professor Mei Hwei Chang, College of medicine, National taiwan university for agreeing to use the stool color card.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rayan Sharief Shaibo

Rayan sharief shaibo is a pediatric specialist, pediatric council, Sudan Medical specialization board, Khartoum, Sudan.

Muaath Ahmed Mohammed

Muaath Ahmed Mohammed is a pediatrician, pediatric council, Sudan Medical specialization board, Khartoum, Sudan.Also, he is a lecturer of physiology, faculty of medicine, ibnsina university, Khartoum, Sudan

Hanaa Ahmed Hamad

Hanaa Ahmed Hamad is a consultant pediatrician, Department of Gastroenteroloy, jafar ibn auf specialized hospital for children, Khartoum, Sudan

References

- Sokol RJ. Biliary atresia screening: why, when, and how? Pediatrics. 2009 May 1;123(5):e951–2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3108

- Hartley JL, Davenport M, Kelly DA. Biliary atresia. Lancet. 2009 Nov 14;374(9702):1704–1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60946-6

- Schreiber RA, Barker CC, Roberts EA, et al. Biliary atresia: the Canadian experience. J Paediatr. 2007 Dec 1;151(6):659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.05.051

- Schreiber RA, Butler A. Screening for biliary atresia: it’s in the cards. Can Family Physician. 2017 Jun 1;63(6):424–425. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/content/cfp/63/6/424.full.pdf

- Witt M, Lindeboom J, Wijnja C, et al. Early detection of neonatal cholestasis: inadequate assessment of stool color by parents and primary healthcare doctors. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2015 Oct 28;26:067–73. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1566101

- Lee M, Chen SC, Yang HY, et al. Infant stool color card screening helps reduce the hospitalization rate and mortality of biliary atresia: a 14-year nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine. 2016 Mar;95(12):e3166. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003166

- Tseng JJ, Lai MS, Lin MC, et al. Stool color card screening for biliary atresia. Pediatrics. 2011 Nov 1;128(5):e1209–15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3495

- Gu YH, Yokoyama K, Mizuta K, et al. Stool color card screening for early detection of biliary atresia and long-term native liver survival: a 19-year cohort study in Japan. J Paediatr. 2015 Apr 1;166(4):897–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.12.063

- Gu YH, Zhao JQ, Kong YY, et al. Repeatability and reliability of home-based stool color card screening for biliary atresia based on results in China and Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2020;252(4):365–372. doi: 10.1620/tjem.252.365

- Lien TH, Chang MH, Wu JF, et al. Effects of the infant stool color card screening program on 5‐year outcome of biliary atresia in Taiwan. Hepatology. 2011 Jan;53(1):202–208. doi: 10.1002/hep.24023

- Woolfson JP, Schreiber RA, Butler AE, et al. Province-wide biliary atresia home screening program in British Columbia: evaluation of first 2 years. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018 Jun 1;66(6):845–849. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001950

- Ashworth J, Tavares M, Silva ES, et al. The stool color card as a screening tool for biliary atresia in the digital version of the Portuguese child and youth health booklet. Acta Médica Portuguesa. 2021 Aug 31;34(9):632–633. doi: 10.20344/amp.16679

- Angelico R, Liccardo D, Paoletti M, et al. A novel mobile phone application for infant stool color recognition: an easy and effective tool to identify acholic stools in newborns. J Med Screen. 2021 Sep;28(3):230–237. doi: 10.1177/0969141320974413

- Wildhaber BE. Screening for biliary atresia: Swiss stool color card. Hepatology. 2011 Jul 1;54(1):368. doi: 10.1002/hep.24346

- Masucci L, Schreiber RA, Kaczorowski J, et al. Universal screening of newborns for biliary atresia: cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies. J Med Screen. 2019 Sep;26(3):113–119. doi: 10.1177/0969141319832039

- Mogul D, Zhou M, Intihar P, et al. Cost-effective analysis of screening for biliary atresia with the stool color card. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Jan 1;60(1):91–98. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000569

- Kong YY, Zhao JQ, Wang J, et al. Modified stool color card with digital images was efficient and feasible for early detection of biliary atresia—A pilot study in Beijing, China. World J Pediatr. 2016 Nov;12(4):415–420.

- El-Shabrawi MH, Baroudy SR, Hassanin FS, et al. A pilot study of the value of a stool color card as a diagnostic tool for extrahepatic biliary atresia at a single tertiary referral center in a low/middle income country. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2021 Mar 1;22(1):61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2020.12.004

- Zheng J, Ye Y, Wang B, Zhang L. Biliary atresia screening in Shenzhen: implementation and achievements. Arch Dis Child. 2020 Jun 8;105(8):720–723.

- Witt M. Presentation and treatment of biliary atresia. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. 2018: 125. Available from: https://research.rug.nl/en/publications/presentation-and-treatment-of-biliary-at