ABSTRACT

Background

Child discipline practices are the methods used by parents to prevent future unwanted behavior in children. Child discipline practices involve non-violent and violent. Violent discipline is a pervasive problem across Egypt shaped by many factors and has many negative consequences. This study attempted to measure the prevalence of child discipline practices among mothers in Alexandria and their associated maternal psychosocial profile of mothers.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted to interview a sample of 275 mothers at eight family health units and centers in Alexandria using interview format to collect personal and socio-demographic data in addition to The Arabic version of the parent form of Conflict Tactics Scales Parent-Child (CTSPC) form and The Arabic Version of Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS).

Results

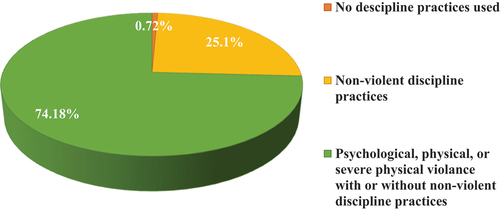

The study revealed that 25.09% of studied mothers were using nonviolent discipline practices (NVDP) only, while 74.18% were using psychological, physical, or severe physical violence with or without using NVDP.

A significantly higher percentage of mothers who use NVDP are of high socioeconomic status compared to the other group (73.9% compared to 17.6%), they scored normal on the three domains of DASS compared to the other group (76.8% compared to 30.5% on depression domain, 72.5% compared to 14.7% on anxiety domain and 60.9% compared for 18.6% on stress domain).

1. Introduction

Discipline is an integral part of child rearing. It shapes a child’s self-control and behavior and is crucial for child development and socialization [Citation1].

Child discipline is intended to teach what good and proper behaviors are while eliminating negative behaviors so that children can grow into responsible and social grown-ups [Citation2].

Child discipline practices simply are “the methods used by parents (or caregivers) to prevent future unwanted behavior in children.” They include training directed at moral and mental improvement through developing cognitive skills such as self-control, behavioral boundaries, judgment, and positive social conduct. The ultimate aim of these practices is to produce a specific character or shape of personality [Citation3].

Child discipline practices range from nonviolent discipline practices based on discussion and reasoning to violent ones which could be classified into three major categories of practices; verbal aggression, physical violence, and severe physical violence [Citation4].

Psychological violence encompasses such behaviors as screaming or yelling at, threatening, or insulting children. Physical violence includes hitting, shaking, and spanking, while severe physical violence includes acts like choking, burning, or scalding [Citation5].

Violent child discipline practices are considered as a form of child maltreatment carried out by parents at home, it is related to parenting or the process of raising children [Citation6]. In 1984, Jay Belsky published a manuscript outlining his model of parenting process, the theory that has become the classical theory among parenting and family psychologists till now. According to Belsky’s model, parenting is determined by three domains; the parent characteristics, the child characteristics, and the family’s social context characteristics [Citation7].

Within the parent characteristic domain, Belsky reported parental psychological functioning as a major important factor that plays role in parenting process [Citation7].

Parents suffer from psychological issues; depression, anxiety, and stress frequently have behavioral changes, including inconsistent parenting, increased negative communication, decreased supervision, and the establishment of ambiguous rules or limits on behavior. Parents who suffer from psychological issues have tendency to be more reactive than proactive, with tendency to the use of violent discipline practices [Citation8].

The extent and trends of national or international rates as well as determinants of child abuse are largely unknown. Nonetheless, international research reveals shocking numbers [Citation9]. Globally, one out of every two children between the ages of 2 and 17 is estimated to encounter a sort of violence every year [Citation10].

The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), in 2017, reported that Egypt had the highest percentage all over the world of children aged 2–4 years who experienced any violent discipline, which was about 94%. Egypt also occupied the first place all over the world in percentage of children aged 2–4 years who experienced severe physical punishment by about 48% and occupied the second place in percentage of children aged 12–23 months who experienced any violent discipline [Citation11].

According to UNICEF, in Egypt, in 2022, percentage of children aged 1–14 years who have experienced any violent discipline practice (psychological aggression and/or physical punishment) ranged from 10% to 80% [Citation12].

The Egyptian government has made significant progress in tackling the issue by enacting a variety of national policies; however, the high prevalence of violent disciplinary practices in Egypt continues its rise which raises many research questions [Citation13].

This study aims at measure the prevalence of child discipline practices and associated maternal psychosocial profile of mothers in Alexandria.

2. Subjects and methods

2.1. Study design and research setting

A cross-sectional study design was adopted. Alexandria governorate is divided into eight administrative districts. The study was conducted in family health units/centers where one family health unit/center was randomly selected from each district.

2.2. Target population

This study included mothers attending the selected family health units and centers.

Inclusion criteria:

Mothers of normal children aged from 1 to 14 years (because child discipline practices during this age group are critical for shaping child behavior and self-control).

Mothers who serve as primary caregivers.

Mothers who are willing to participate.

Exclusion criteria:

Mothers without permanent residence in Alexandria.

2.3. Sampling

2.3.1. Sample size

The sample size was calculated using Epi Info 7 software for sample size calculation, using a 93% prevalence of any violent discipline method experienced by children age 1–14 years in Alexandria according to Egyptian demographic and health survey 2014 [Citation14], design effect 2.5 and limit of precision 5%. The calculated sample size was 250 mothers and was increased to 275 to adjust for non- or incomplete response.

2.3.2. Sampling technique

A stratified random sampling technique with proportionate allocation was used to obtain the sample.

Alexandria is divided geographically into eight health districts (El Montazah, East, Middle, West, El Gomrok, El Agamy, Borg El Arab and El Amreya health districts).

From the list of family health centers and units published in the report of the Information Center, Alexandria Directorate of Health Affairs, 2021 [Citation15], one health unit/center was randomly chosen from each health district. A representative sample of mothers with proportionate allocation according to the number of female population served by each health district was obtained from the selected family health unit or center in the district, as follows; 83 mothers from El montazah health district, 62 mothers from East health district, 30 mothers from Middle health district, 19 mothers from West health district, 8 mothers from El Gomrok health district, 40 mothers from El Agamy health district, 8 mothers from Borg EL Arab health district, and 25 mothers from El Amreya health district.

2.4. Data collection

Data was collected through direct face-to-face interviews with mothers using a specifically designed interview format. Data in the interview format included:

1-Personal data: including mother’s age, residence, marital status, and age of the child.

2-Socioeconomic data: including education and occupation of the mother and her husband, crowding index as well as monthly income. These data were summed in a total socio-economic score modified after Fahmy and El Sherbini (1983) [Citation16], which is classified into; high socio-economic status (>31), middle socio-economic status (25–31), low socio-economic status (<25)

3- The Arabic version of the parent form of Conflict Tactics Scales Parent–Child (CTSPC) Parent form [Citation17]: The CTSPC was originally developed to identify child psychological and physical maltreatment and neglect by parents, as well as nonviolent modes of discipline.

It contains 22 items across three subscales of discipline during the last month, namely nonviolent discipline (4 items), psychological aggression (5 items), and physical assault (5 items for corporal punishment, 4 items for severe physical assault, 4 items for very severe physical assault).

The nonviolent discipline scale measures the use of four disciplinary practices that are widely used alternatives to corporal punishment (explanation, time out, deprivation of privileges and substitute activity). The psychological aggression-scale measures verbal and symbolic acts by the parent intended to cause psychological pain or fear on the part of the child.

Physical assault scale includes acts from minor physical assault, for which parents are granted an exemption from prosecution for assault (corporal punishment) to very severe physical acts that result in child injury.

The interviewed mothers were asked whether they practiced each item of previously mentioned subscales during the last month against her child. If the mother has more than one child in the selected age range, the child was selected using a Kish grid to avoid selection bias. The Kish Grid is a way of randomly choosing one in a household, by assigning numbers to each member of the household, based on age. The most important aspect of the grid is that it assigns an equal probability for selection of each member [Citation14,Citation18]. A modified form of Kish grid was used [Citation19,Citation20].

4- The Arabic Version of Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) [Citation21]:

The DASS is a set of three self-report scales designed to measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress. Each of the three DASS scales contains 14 items. Mothers were asked to use 4-point severity/frequency scales to rate the extent to which they have experienced each state over the past week. Scores for depression, anxiety, and stress are calculated by summing the scores for the relevant items. The Arabic Version of DASS has been shown to have high internal consistency and to yield meaningful discriminations in a variety of settings.

Scores of the three subscales were interpreted as follows:

2.5. Data analysis

1- Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) version 22 [Citation22]. Variables were presented using numbers and percent for qualitative variables, and mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables. The Chi-square test was the appropriate statistical test used. Significance of the results was obtained at level below or equal to 0.05.

3. Results

The present study included 275 mothers; the majority were urban residents (83.6%). The mean age of the enrolled mothers was 33.1 ± 8.4 years with a minimum of 18 years and maximum of 55 years. The mean age of children was 6.4 ± 3.3 with a minimum of 1 year and maximum 14 years. Upon calculation of total socioeconomic score, 37.5% were low, 30.9% were moderate and 31.6% were socioeconomically high.

shows the prevalence of different types of child discipline practices perpetrated by sampled mothers during the last month according to Conflict Tactics Scale-Parent Child form. It reveals that about one quarter of studied mothers (25.09%) were using nonviolent discipline practices (NVDP) only without using any form of violence, while about three quarters (74.18%) of studied mothers were using one or more forms of violence with or without using NVDP. Two mothers did not use any method of child discipline due to the young age of their children (1 year) as mentioned by mothers, so they were excluded from the data analysis, tables, and figures. Accordingly, the total was 273 and not 275.

Figure 1. Distribution of sampled mothers by the used type of child discipline practices, in Alexandria, 2023.

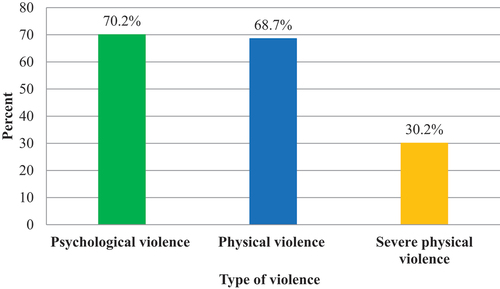

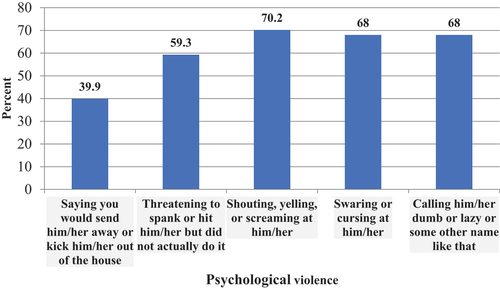

As illustrates, the most common type of violent discipline practices was psychological violence (70.2% of all violent discipline practices). Moreover, the most common form of psychological violence is shouting, yelling, or screaming at the child ().

Figure 2. Distribution of sampled mothers by the used type of violent discipline practices, in Alexandria, 2023.

Figure 3. Distribution of different forms psychological violent discipline practices, in Alexandria, 2023.

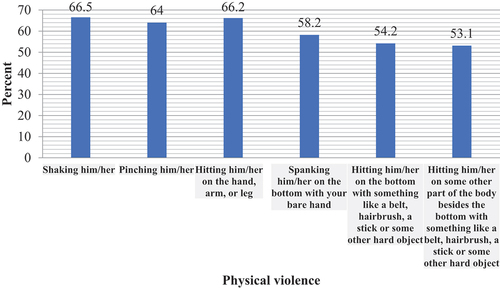

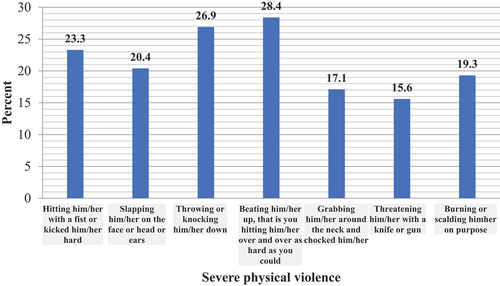

As for physical violence, the most common form was shaking the child by 66.5%. While the most common form of severe physical violence was beating the child up, the mother hits him/her over and over as hard as the mother can, by 28.4% ().

Figure 4. Distribution of different forms physical violent discipline practices, in Alexandria, 2023.

Figure 5. Distribution of different forms severe physical violent discipline practices, in Alexandria, 2023.

Socio-demographic characteristics of sampled mothers who used NVDP only versus who used psychological, physical, or severe physical violence with or without NVDP are illustrated in . As the table portrays, there is a statistically significant difference between the two regard residence where 95.7% of mothers using NVDP lived in urban areas as compared to 79.9% of the other group.

Table 1. Distribution of sampled mothers who use nonviolent discipline practices only versus who use psychological, physical, or severe physical with or without nonviolent discipline practices by their socio-demographic characteristics, in Alexandria, 2023.

A significantly higher percentage of mothers who used NVDP were dealing with toddlers (1 < 3 years) by 24.6% compared to 7.8% for the other groups. On the other hand, a significantly higher percentage of mothers who used psychological, physical, or severe physical with or without NVDP were dealing with preschoolers (3 < 6 years) by 34.8% compared to 20.3% for the other groups. Overall, there is an increasing trend for using violent child discipline practices with increasing the age of the child to reach 57.4% in school age children (>6 years).

There is a statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the educational level of mothers where significantly higher percentage of mothers using NVDP got high education (institute and university graduate) compared to the other group (42% and 37.7% compared to 25.5% and 10.8% respectively). Concerning occupation, a significantly higher percentage of mothers using NVDP, and their husbands have professional occupation compared to the other group (31.9% and 68.1% compared to 2.5% and 15.7% respectively).

Overall, a significantly higher percentage of mothers who use NVDP are of high socioeconomic status compared mothers who use psychological, physical, or severe physical with or without NVDP (73.9% compared to 17.6%).

A significantly higher percentage of mothers who use psychological, physical, or severe physical with or without NVDP were of low socioeconomic status compared to mothers who NVDP only (48% versus 5.8% respectively).

shows the relation between the type of child discipline practices and psychological profile of mothers. There was a statistically significant difference between mothers who use NVDP only versus who use psychological, physical, or severe physical with or without NVDP as regard depression, anxiety, and stress where significantly higher percentage of mothers use psychological, physical, or severe physical with or without NVDP scored mild, moderate, severe, or extremely severe levels of depression, anxiety, or stress compared to the other group.

Table 2. Distribution of sampled mothers who use nonviolent discipline practices only versus who use psychological, physical, or severe physical with or without nonviolent discipline practices by their scores on depression anxiety stress scales, in Alexandria, 2023.

4. Discussion

In all cultures, child discipline practices are an integral part of parenting process and child rearing, it teaches children how to behave properly. Although there is an agreement as regards the necessity for child discipline practices, there is a debate regarding the use of violent psychological and physical discipline practices because they violate child’s rights and have many negative consequences on children’s mental and physical health and social development.

Egypt has made significant progress in tackling the issue by enacting a variety of national policies. The present study reveals a declining trend regarding the use of violent child discipline practices in the Egyptian society, from 93% according to Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) 2014 [Citation14], to 84.1% according to Egypt Family Health Survey (EFHS) 2021 [Citation23]. This could be justified by the increasing awareness of parents about the nonviolent methods to discipline their children and about the harmful effect of using violent discipline practices against their children.

This large difference between what reported in EFHS 2021 and the current study could be attributed to that the majority of the studied sample were urban mothers (83.6%) and it is documented that the violent child discipline practices are more widespread in rural areas [Citation24,Citation25].

Although the declining trend in use of violent discipline practices, Egypt is still one of the highest around the world. Although the exact extent and trends of national or international rates are largely unknown [Citation9], international research reveals that, globally, one out of every two children (50%) between the ages of 2 and 17 is estimated to encounter a sort of violence every year [Citation10]. In comparison with Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Egypt still has higher prevalence, for example, the prevalence rate in Sudan is 64%, Lebanon 57%, and Qatar 50% [Citation26].

The high prevalence rate of this problem could be attributed to several factors; parents feel pressured by the prevailing culture of society and their own beliefs in its necessity to raise well-disciplined obeying children. Due to the intergenerational transmission of the issue, mothers who employ violent discipline practices with their children mostly have been gone through similar experiences as children, normalizing the problem in Egypt from generation to another. Egyptian families struggle financially because of their demanding living conditions and poverty, putting more stressors on mothers leading to such violent behavior. Furthermore, even though the Egyptian Child Law is in force, there is a shortfall of awareness and receptivity to children’s rights and parental responsibilities to them.

The most common type of violent child discipline practices in the current study was psychological violence, in agreement with Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) 2014 [Citation14]. However, it shows marked decline from 91.1% in EDHS 2014 to 70.2% in the current study.

The present study reveals that, in agreement with EDHS 2014, the most common form of psychological violence was shouting, yelling, or screaming at the child. However, it shows marked decline from 88% in EDHS 2014 to 70.2% in the current study [Citation14].

Regarding physical violence, the most common form of physical violence in the current study is shaking the child by 66.5%, while in EDHS 2014, it was hitting the child on the hand, arm, or leg by 54.8% [Citation14]. Also, the most common form of severe physical violence in the current study is beating the child up that is the mother hitting him/her over and over as hard as the mother can, by 28.4%, while in EDHS 2014, it was hitting the child on the face, head, or ears by 41.2% [Citation14].

The current study found a statistically significant differences between mothers who use NVDP only versus those who use psychological, physical, or severe physical violence with or without NVDP for all determinants of socioeconomic status (SES). A lower educational level and less prestigious occupation of the mother and her husband, as well as lower monthly income, give lower total socioeconomic scores. A significantly higher percentage of mothers who use psychological, physical, or severe physical with or without NVDP are of low socioeconomic status compared mothers who use NVDP only (48% compared to 5.8%).

This agrees with what was stated by UNICEF in its report about child discipline practices at home in middle- and low-income countries where a series of family-related risk factors for the use of violence in child rearing practices were identified. UNICEF stated that children from families with low education, low income, and overcrowding homes (three of the indicative factors of low socioeconomic status) are more likely to experience violent discipline practices [Citation3].

Low socioeconomic status contributes to insecurity and parental stress which, in turn, increase parental use of violent, punitive, and coercive behaviors. When behavior and belief do not align (i.e. when children are exposed to disciplinary violence despite caregivers not believing in its efficacy) may provide a more explicit measure of parenting behavior driven by stressors, not belief [Citation27,Citation28].

Low socioeconomic status entails domains that lead to violent discipline in many ways. Higher rates of poverty and unemployment, such low-income levels put the family under high financial pressure which increases the use of violent discipline. Low education of parents makes a wide gap of knowledge regarding the negative consequences of violent discipline practices and unawareness about the positive ways and nonviolent alternatives for child discipline. Less prestigious occupations need high physical effort for long time which exhaust the parents and makes them unable to respond appropriately to their children.

However, many confounding variables may distort the relation between low socioeconomic status and violent discipline practices like cultural background of low socioeconomic families which normalize the use of violence. The developmental history of parents and suffering from negative adverse childhood experiences is another variable, where parents who were abused as children are more likely to abuse their children. Wrong behavior of low socioeconomic children which they are taught from their friends and colleague is another factor.

Regarding the association between the type of disciplinary practices and psychological profile of mothers, the current study found that significantly higher percentages of mothers use psychological, physical, or severe physical with or without NVDP suffer from variable degrees of depression, anxiety, or stress compared to the other group (69.6% compared to 23.2% on depression domain, 85.3% compared to 50% on anxiety domain and 81.4% compared for 58% on stress domain).

These results are in accordance with different theoretical perspectives and research results where impaired mental health of mothers and poor parenting are related. Depression and anxiety may negatively affect mothers’ capacity to give sensitive care or consider their children’s viewpoints (i.e. empathic understanding). The caregiving abilities and the capacity to focus on the needs of their own children are compromised because they are so consumed by their own negative ruminations [Citation29,Citation30]. Maternal stress frequently results in behavioral changes, including inconsistent parenting, increased negative communication, decreased supervision, the establishment of ambiguous rules or limits on behavior, a tendency to be more reactive than proactive, and the use of violent disciplinary techniques [Citation8,Citation31].

Depression impairs mothers’ cognitions, affects, and behaviors, which in turn makes it more likely that mothers would overlook the emotional and social needs of their children. Coyne et al.. (2007) discovered that depressive women paid less attention and less reactions to their children and had a more negative view about them [Citation32].

According to a meta-analysis of 46 studies using observational measures of parenting behavior, maternal depression has consistently been linked with higher levels of harsh, negative parenting and, to a lesser extent, with lower levels of positive, sensitive parenting [Citation29].

5. Conclusion and recommendation

The study revealed that violent child discipline practices are still widely used by mothers in Alexandria. It is more common among low socioeconomic class mothers with low education, less prestigious occupation, and low-income level.

The psychological aspect of mothers plays an important role in parenting process, violent child discipline practices are more likely to be used by mothers suffer from variable degrees of depression, anxiety, and stress.

The present study provides valuable information and has important practical implications. It informs social, economic, and health policies that promote socioeconomic stability and equality and that improve living standards. Social Policies include public awareness campaigns, community support programs, and social services enhancement. Economic policies include poverty alleviation, social welfare programs, parental leave, and flexible work policies. The health policies are mainly improved access to health-care services, affordable and comprehensive health-care services, including mental health support for families. Legislation and legal frameworks are also essential for protecting children from violence, ensuring that perpetrators face appropriate legal consequences.

The current findings provide strong empirical evidence that appropriate prevention intervention efforts are needed to target mothers from low socioeconomic class mainly. The findings regarding the coexistence of maternal violent discipline and psychological disorders emphasize the importance of intervening on the psychological aspect of mothers side by side with parenting education.

Limitations of the present study include the potential for inherent response biases in self-reported data, particularly faced in sensitive topics like child discipline. This could include recall bias, social desirability bias, or other cognitive biases that might affect the accuracy of the information provided by participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Meldrum RC, Hay C. Do peers matter in the development of self-control? Evidence from a longitudinal study of youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41(6):691–703.. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9692-0

- Nelsen J. Positive discipline: the classic guide to helping children develop self-discipline, responsibility, cooperation, and problem-solving skills. New York: Ballantine Books; 2011.

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Child disciplinary practices at home: evidence from a Range of Low- and middle-income countries. New York: UNICEF; 2010.

- Straus MA, Mattingly MJ. A short form and severity level types for the parent-child conflict tactics scales. Durham, NH: Family Research Laboratory, University of New Hampshire; 2007.

- Taraban L, Shaw DS, Leve LD, et al. Maternal depression and parenting in early childhood: contextual influence of marital quality and social support in two samples. Dev Psychol. 2017;53(3):436–449. doi: 10.1037/dev0000261

- World Health Organization (WHO). Preventing child Maltreatment: a guide to taking action and generating evidence. Geneva: WHO; 2006.

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Dev. 1984 Feb;1(1):83–96. doi: 10.2307/1129836

- Chandler M, Heffer R, Turner E. The influence of parenting styles, achievement motivation, and self-efficacy on academic performance in college students. J Coll Stud Dev. 2009;50(3):337–346. doi: 10.1353/csd.0.0073

- Gilbert R, Fluke J, O’Donnell M, et al. Child maltreatment: variation in trends and policies in six developed countries. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):758–772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61087-8

- Hillis S, Mercy J, Amobi A, et al. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: a systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20154079. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4079

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). A familiar faceviolence in the lives of children and adolescents. New York: UNICEF; 2017.

- United Nations International Children’s Energency Fund (UNICEF). Violent discipline. 2022. [Cited 2023 7 October]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/violence/violent-discipline/

- Swailam I, Fahiem M, Hesham R, et al. On positive parenting: preventing disciplinary violence against children within Egyptian households. Egypt: The American university in Cairo; 2022.

- Egypt Demographic and Health Survey, El-Zanaty F. Cairo EMoHap, Ministry of Health and Population, El-zanaty and associates and Rockville. Maryland, USA: The DHS Program, ICF International 2015, 2014.

- Alexandria Directorate of Health Affairs. Distribution of population on 1/1/2021 by medical districts and gender; information center. 2021.

- Fahmy SI, El-Sherbini AF. Determining simple parameters for social classifications for health research. Bull HIPH. 1983;XIII(5):95–107.

- Abu-Nazel MW, Al Nakeb KM Profile of domestic violence perpetration by husbands attending health insurance general practitioner clinics in Alexandria, Egypt. Proceedings of The International Conference “Alex Health”2014 Health from Theory to Practice; Alexandria, Egypt. 2014.

- Lewis-Beck M, Bryman AE, Liao TF. The sage encyclopedia of social science research methods. California: Sage Publications; 2003.

- Lorence B, Hidalgo V, Pérez-Padilla J. The role of parenting styles on behavior problem profiles of adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15):27–67. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152767

- International labour office. Sampling methodology. In: Elders S, editor. In: ILO school to work transition survey: a methodological guide. Geneva: ILO; 2009:22.

- Ali AM, Ahmed A, Sharaf A, et al. The Arabic version of the depression anxiety stress scale- 21: cumulative scaling and discriminant-validation testing. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;30:56–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.07.018

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp 2012.

- Central agency for public mobilization and statistics. Egypt family health survey. 2021.

- Alyahri A, Goodman R. Harsh corporal punishment of Yemeni children: occurrence, type and associations. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32(8):766–73.. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.01.001

- Pinderhughes EE, Nix R, Foster EM, et al. Parenting in context: impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks, and danger on parental behaviors. J Marriage Fam. 2001;63(4):941–53.. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00941.x

- United Nations International Children’s Energency Fund (UNICEF). Violent discipline. 2022. [cited 2022 Aug23]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/violence/violent-discipline/

- Beatriz E, Salhi C. Child discipline in low- and middle-income countries: socioeconomic disparities at the household- and country-level. [online]. Child Abuse Negl. 2019 [October 2023];94:104023. [cited 2023 8] Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0145213419301851

- Tran TD, Luchters S, Fisher J. Early childhood development: impact of national human development, family poverty, parenting practices and access to early childhood education. Child Care Health Develop. 2017;43(3):415–426. doi: 10.1111/cch.12395

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, et al. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20(5):561–92. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7

- Hummel AC, Kiel EJ, Zvirblyte S. Bidirectional effects of positive affect, warmth, and interactions between mothers with and without symptoms of depression and their toddlers. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(3):781–9. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0272-x

- Kopko K. Parenting styles and adolescents. New York: Cornell University Cooperative Extension; 2007. pp. 1–8.

- Coyne LW, Low CM, Miller AL, et al. Mothers’ empathic understanding of their toddlers: associations with maternal depression and sensitivity. J Child And Fam Stud. 2007;16(4):483–497. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9099-9