ABSTRACT

This research is aimed at investigating Corporate Environmental Responsibility in Manufacturing Enterprises in the Akaki River basin on protecting the urban environment with particular emphasis on twenty selected industries. To attain its objective, the study employed a mixed methods research approach. Data were collected by employing tools such as questionnaire, key informant interview, group discussions and observation. The findings of the research show that corporate environmental responsibility is very low. The majority of Large Scale Industries encompassed in the survey did not show considerable effort on protecting the environment responsibly. The reasons identified by this research are among others the absence of corporate environmental responsibility, low pressure from the enforcing institutions, and lack of financial and human resources. As a result, the Akaki River is highly polluted mainly through toxic industrial effluents released with little or no prior treatment. The consequences are countless. The populations living across the river are facing health deteriorations and economic damages. Based on the findings of this study, setting up strong institutions which are capable of developing new laws and implementing the existing environmental legal framework is commended.

Introduction

The literature reviewed illustrates that urban environment has much to do with pollutions caused through the course of industrialization (Langeweg, Hilderink, & Mass, Citation2000, Douglass, Citation1999). This is mainly because the cradle of the urbanization process is the result of modern industrialization (WAN Yongkun et al, Citation2013). Because most industries are located within and/near to urban settlements, the urban environment is severely exposed to pollution and degradation. Considering the life-threatening nature of environmental troubles throughout the world, global organizations and individual states are designing different mechanisms on how to resolve problems of the natural environment.

The United Nations General Assembly, for example, in its resolution 45/94 (1990) reaffirmed the Stockholm declaration by stating that “all individuals are entitled to live in an environment adequate for their health and well-being” and calls for enhanced efforts toward ensuring a “better and healthier environment” Abadir Ibrahim, (Citation2009, 62–74).

An additional argument would make a case that the Ethiopian Constitution clearly declares that “all persons have the right to a clean and healthy environment” (FDRE Constitution, Citation1995). The constitution also proclaims that the Government has a duty to struggle to ensure that all Ethiopians live in a “clean and a healthy” environment. Some of the articles of the Environmental Policy of Ethiopia directly or indirectly address urban environment management issues. Articles 3(7) and 3(8) of the environmental policy address issues related to Human Settlement, Urban Environment and Environmental Health, Control of Hazardous Materials and Pollution from Industrial Waste (FDRE Citation1997).

The legal environmental regulatory framework is largely promising, at least in principle. Yet, practices reveal that environmental management is a policy responsibility of the Environmental Protection Authority and its allies in Ethiopia (Melese Citation2009). There is a lack of information on either corporations are governing the natural environment responsibly or worse exhausting it.

Unfortunately, there is inadequate information on corporate environmental management in developing countries, especially on the African continent (Nukpezah Citation2010). The need for capacity building and technology transfer to less developed countries, such as Ethiopia, remains an important developmental agenda. As the focus in Ethiopia, manufacturing industries are predominantly located along watercourses and coastal wetlands and the discharge of untreated wastes into these water bodies and the adjacent area has resulted in gross pollution of these regions. Pollution and the threat of more pollution from industry thus remain real (Janka Citation2007, 1–34).

Recent studies on the environment (e.g., Damtie and Kebede (Citation2012), Feyisa (Citation2016), Getu (Citation2013), Aregawi (Citation2014)) further state that Ethiopia’s past development has been highly criticized due to lack of integrating environmental concerns into the development agendas. Nevertheless, in order to ensure sustainable development, it is essential to integrate environmental concerns into development activities, programs, and policies.

Consequently, though, it is just from the start, pollution from the industrial sector in Ethiopia has been on the rise, posing a serious problem to the environment. Many industrial processes produce polluting waste substances that are discharged to the environment (Aregawi Citation2014). Among the most polluting industries are textiles, tanneries, and beverage & food processing industries with processing plants and factories that produce liquid effluents which are discharged into rivers, often without treatment. In Addis Ababa, rivers frequently receive polluting discharges from many different sources all at the same time (Eshetu Citation2012). Therefore, curbing dangerous industrial pollution from the start requires the engagement of every stakeholder.

Existing literature on environmental governance in Ethiopia takes no notice of the notion of Corporate Responsibility. Most writings, though they are in short quantity, are not investigating the environmental governance in its entirety. Scores of research studies conducted on air and water pollution (Van Rooijen and Taddesse Citation2009, Kumie Citation2009) and deforestation, degradation, and climate change (Tedla and Kifle Citation1998). Nonetheless, the corporate aspect of Environmental Governance seems to be overlooked. Previous researches are conducted assuming the government as a sole vanguard actor in protecting the environment.

As the central goal of this research is to examine Corporate Responsibilities to Environmental Governance and the mechanisms through which these factors operate, inquiries call into question the degree to which the regulatory and legal framework governing environmental protection addresses this problem. Further, it is going to address subjects related to corporate environmental challenges of Ethiopia, with emphasis on the urban environmental governance. In addition, this study seeks to document the extent to which environmental governance is on the corporate agenda in Ethiopia.

Objective of the study

The overall objective of this study is to investigate corporate environmental responsibility (CER) practices in large-scale manufacturing enterprises in the Akaki River Basin in protecting the urban environment.

Research questions

This thesis looks at CER; what are and should companies be doing? Given the problem discussed above, it is neatly reasonable to ask the following key research questions:

How are manufacturing industries treating their industrial waste? Do they have an adequate facility, capacity, commitment, and knowledge?

How appropriate and to what extent effective are environmental laws in controlling environmental pollution from the Manufacturing Industries?

Description of the study area and research methodology

Description of the study area

Addis Ababa lies at an altitude of 2300 m above sea level and is a grassland biome, located at 9°1′48″ N and 38°44′24″ E. The city lies at the foot of Mount Entoto and forms part of the watershed for the Awash River Basin. The Akaki River Basin is part of the city of Addis Ababa (MEFCC Citation2005).

The Akaki River Basin is located in the central Ethiopian highlands near the western edge of the Main Ethiopian Rift System. Akaki River is located between 8°16ʹ N and 37°57ʹ E. The total surface area of the catchment is 1462 km. Large mountains and various volcanic rocks characterize the watershed boundary. The elevation varies from 2060 m above sea level in the south around the Akaki well field to 3200 m above sea level in the northern Entoto Mountains. The entire catchment is bounded to the north by the Entoto ridge system, to the west by Mt Menagesha and the Wechecha volcanic range, to the southwest by Mt Furi, to the south by Mt Bilbilo and Mt Guji, to the southeast by the Gara Bushu Hills and to the east by the Mt Yerer volcanic center (MEFCC Citation2005).

Research methodology

A combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods was used to collect data from respondents. The nature of research problems most often dictates the methodology of the study. This study focuses on examining the responsibilities of corporations in governing and protecting the urban environment. Both practices (actual performance) and opinions regarding the issue were measured. Given the fact that subjective opinions and verified performances require different mechanisms to deal with, this study ascribes itself into a mixed research approach/design.

Types, sources, and tools of data

Both primary and secondary types of data have been used throughout this study. The primary data were collected from in-depth key-informants interview with corporate heads and high-ranking government officials (key informants were selected based on their significance to the problem), 20 mixed format survey questionnaire, and direct personal site observation on the field (in order to triangulate the results from questionnaires and personal interviews and get the actual practice on the ground, the researcher went to the study area for an observation and fact-finding). The secondary data, on the other hand, were consulted from books, journals, the Internet, government policies, and corporate reports.

Sample and sampling procedure

Company selection was made based on the three factors such as company size, location, and pollution status. Samples were selected purposively as deemed appropriate for the study based on the parameters mentioned above. Therefore, large-scale and highly polluting industries, located along the near post of the Akaki River Basin system (approximately 200 m) have been the subject of investigation. Based on these measures, 20 large-scale manufacturing firms were selected as samples of this research. The criteria to decide the firms’ size as Large, Medium, or Small are based on the Ministry of Industry’s (MoI) classification system. All firms in the survey satisfied the MoI’s parameter for “large-scale manufacturing industry.”

Data presentation, analysis, and interpretations

This study has used descriptive statistics as a method of data analysis with concurrent triangulation. Quantitative data collected through survey questionnaires have been organized and entered into the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS version 21) software to result in descriptive statistics and to examine the problem under study. In addition, qualitative data gathered through focus group discussion and key informant interview were described qualitatively to corroborate the questionnaire data.

Results and discussion

Results

Throughout the survey, 20 large- and medium-scale manufacturing industries located near to the Akaki River were studied. It has been found accordingly that majority of these sample firms are seriously polluting the urban environment. Though not faultless, there are few corporates working on the protection of the urban environment, where they are operating. However, this does not mean that all government environmental regulatory standards are fully applied to these corporates.

How dedicated to corporate environmental responsibility are companies in Akaki River Basin?

In this current study, 14 out of the total 20 corporates included in the survey replied they have a policy dealing with the treatment of hazardous waste (see ). Companies which have no waste treatment plant and actually highly pollutant claimed to have an official environmental policy. Having the policy, however, the absolute majority of these companies are not moving for the implementation. For example, the National Alcohol Factory (Mekanisa plant) has an environmental policy and claims it is working for the protection of the environment. The company also displays a large banner outside the gate stating as “it is committed to working for environmental protection.” In spite of this claim though, the company has no Effluent Treatment Plant. The industrial waste is directly released to the nearby river without any prior treatment. During the observation, the researcher witnessed many cases similar to the National Alcohol Factory (personal observation, 2017).

Table 1. Corporate environmental policy

Similarly, manufacturing industries were also asked about the ISO 14001 series environmental standards accreditation as a measure for good environmental management system. From the total of 20 companies consulted in the survey, only 3 were found accredited with ISO 14001 Environmental Standard Accreditation, while the vast majorities (17 companies) are not yet accredited for ISO 14001 environmental standards as an initiative to manage the environment (see ). These standards have been designed to help enterprises meet their environmental management systems needs such as the setting of goals and priorities, assignment of responsibility for accomplishing them, measuring and reporting on results, and external verification of claims. As per the researcher’s perception, lots of large-scale manufacturing industries are not registered for ISO 14001 standards accreditation because they fail the requirements compulsory for it. Such requirements as many are not treating their industrial effluents properly, they have no environmental policy, and an internal unit for environmental protection, etc. (own survey, 2017).

Table 2. Corporate ISO accreditation

Trends on CER throughout the world show that companies that respond effectively to the challenges of sustainability can gain a competitive advantage, exploit new market opportunities, boost market share, increase shareholder value, and become more profitable. Improved Corporate Environmental Governance is one way to respond to these challenges ().

Table 3. Factor(s) which triggered the company for environmental work

Above all, 75% of companies consulted in the survey believed that they are cooperating with the Ethiopian government to work for the protection of the environment. But this cooperation is mainly regular environmental reporting to EPA organs. This type of cooperation is always obligatory by the authorities. Therefore, voluntary cooperation for emission reduction and pollution control is minimal as corporates in Ethiopia lack environmental responsibility.

Industry Assessment Report of Addis Ababa Environmental Protection Authority (AAEPA) 2016 revealed that very large numbers of Manufacturing Industries are reluctant on cooperating with the government regulatory organs. The corporate move for pollution control and emission reduction is negligible. It further states that a few large- and medium-scale manufacturing industries provide environmental report periodically (AAEPA, 2016, Interview).

How do companies place corporate environmental responsibility into exercise?

Knowing that manufacturing industries use hazardous chemicals during operation, corporates are negligent to effectively treat their industrial effluent. During the field observation, there was no any large- and medium-scale manufacturing industry with effective effluent treatment plant in operation, especially across the little Akaki River system. Some have primary-level treatment systems. But hazardous chemicals such as chrome cannot be easily treated with the conventional treatment plant and even worse, these primary-level treatment plants are not functioning consistently (personal observation, 2017).

The following table shows the laboratory analysis result of industrial effluents which Walia Tannery releases directly to the river. The effluents of the company have only met 2 parameters, temperature and PH value, among the 10 parameters set by the government regulatory organ as a maximum permissible limit ().

Table 4. Effluent released from Walia Tannery to the Akaki River

Awash Tannery does not comply with all the government environmental regulatory frameworks. The waste treatment plants erected by this company after the AAEPA inspection are very rudimentary and constructed mainly for the time of inspection by the authority. Solid and liquid waste treatment system of the case corporates is poor. Thus, effluent liquid, which inevitably made its way into the waterway, is polluting the Akaki River system (AAEPA, 2016, Interview).

Furthermore, this study showed that the amount of water used in the production process, the amount of wastewater discharged into the river, and the level of Effluent Treatment are not known. This poses difficulty in taking mitigation measures and measuring the economic cost of pollution. Hence, the consequences of pollution from these industries on the environment cannot be clearly recognized. Because all large-scale manufacturing industries in Addis Ababa are established along rivers and release a large amount of waste (known for very bad smell) to the Little Akaki River, the downstream community calls the river as “Leather River” – associated with the leather industries ().

Asked for the reasons of why are these companies not complying with the government environmental framework, government regulatory organs responded to the absence of CER. Several corporates are reluctant to set up a permanent internal environmental protections unit which can help to facilitate environmental protection (AAEPA, 2016, Oromia Regional State EPA, 2016, Interview).

Installing an effluent treatment plant and compliance with government regulatory standards as a measure of environmental protection

Slightly half of the companies in the survey admitted that they do not have effluent treatment plant yet, while 55% of companies replied they already have installed effluent treatment plant (see ). An interview with AAEPA Environmental Protection and Inspection Unit showed that manufacturing companies with proper effluent treatment plant are very few, usually beverage industries. Many large- and medium-scale manufacturing industries have a treatment plant mainly primary level, built for purpose of inspection by the EPA organs. By and large, these primary-level treatment plants are not functioning consistently (own survey, 2017).

Table 5. Waste treatment plant

The researcher has conducted a field observation across some parts of the Akaki River Basin system. In March 2017, the observation was started at the middle section of the Little Akaki on three tributaries draining through different areas of Addis Ababa. The observation was conducted in areas where large- and medium-scale industries are located. On the way through, it was observed that many industries across the river dispose of their effluent directly into it. It is easy to see the industrial waste joining the river water through open sources. For instance, in an area called “Garment Sefer,” Nefas-selk-Lafto Sub City, the researcher witnessed chrome waste, one of the most toxic industrial wastes, released to the river without prior treatment. It was the worst case the researcher has seen during the observation and the factory denied access to give information about it ().

Figure 2. Chrome liquid waste heading toward the river without prior treatment

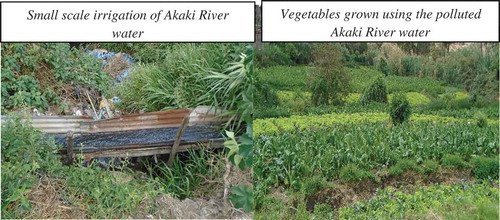

During the observation, the researcher also witnessed that urban farmers are using the Akaki River water for irrigation in spite of its pollution status. The dependence on the river water increases in the downstream places along the river. According to the data from AAEPA and Oromia EPA, the users know that the river water is dangerous and they even call it “toxic water” and they believe the river is dead. Though, knowing the water is “toxic,” farmers are producing vegetables using the river. The researcher gathered a photo of sample vegetables grown using the extremely polluted Little Akaki river water around Gofa-Gabriel area, Addis Ababa ().

Figure 3. Urban agriculture using badly polluted water in Akaki River Basin. Polluted water (left) and sample vegetables grown (right)

Therefore, protecting the urban environment especially from industrial pollution would have a tremendous impact on the health of the urban population. During the course of my observation, the researcher observed a number of open waste sources from the operating companies around the river bank of Akaki releasing their liquid wastes directly into the river. This plainly supports the argument explained in previous sections of this chapter that the presence of the industries in the river banks is just for easy discharging of their liquid wastes into rivers. This is highly deteriorating the quality of the river in particular and degrading the environment of Addis Ababa in general.

Compliance for government regulations and previous achievements on environmental protection

Majority of manufacturing industries were not conforming to the government’s environmental regulatory requirements nor also showing sympathy for responsible corporate environmental governance. As a result, pollution is alarmingly increasing in the Akaki River Basin and adjacent areas due to residues of industries known as effluents released in water and land without any treatment which pollutes the water and land, affecting the biotic life, surface water, and underground water. Industrial wastes particularly hazardous waste and radioactive waste have also become a major environmental pollution problem (EEPA, EIA Unit, Interview result, (2017)).

Because the majority of large- and medium-scale industries located along the Akaki River lack effective Effluent Treatment Plant in operation, recycling process water found to be minimal. Even companies which claimed to have waste treatment plant do not use process water because their treatment is mostly primary level (personal observation, 2017).

Very few companies can recycle process water which is badly polluted with toxic chemicals. Otherwise, the wastewater enters into primary-level Effluent Treatment Plant (ETP) and/or released directly to the nearby river. But many other large- and medium-scale industries release polluted waste into the river without prior treatment let alone recycling it. An interview with corporate heads illustrates that the major reasons for the absence of recycling process water are deficient capacity, facility, and human resources of many large-scale manufacturing industries.

As per AAEPA (2017, Interview), corporates operating along the Akaki River Basin have shown no sign of effluent limitation or emission monitoring as a means of environmental responsibility and accountability. It also adds that they have never been abiding by the law throughout their establishment. Consequently, environmental health is abandoned.

According to AAEPA deputy manager, his office and other collaborative environmentalists face accusations from the government’s “developmental institutions” as anti-development actors which work to obstruct development efforts. The deputy manager adds that the government shows greater adherence to economic growth at any. Balancing the economic thirst and ecological preservation is the major challenge in Ethiopia. According to the manager, the government of Ethiopia is Blameworthy for the ill health of the environment (AAEPA deputy manager, 2017, Interview).

Furthermore, the survey respondents were also asked about environmental-related accomplishments so far. Very few companies are working on pollution control and emission reduction other than the enforced periodic environmental reporting for AAEPA. This is a good evidence that shows companies are not responsibly working to protect the environment and owing to ethical concern for justice. As companies keep going irresponsible to manage the environment, it is very obvious the natural environment where industries are operating around will also have an impact beyond that area (own survey, 2017).

Authorities confirm that farmers are discouraged to upkeep, develop their farmland and increase output and lose cattle (the most invaluable assets to the farmer) due to the pollution from industries and households in the upper stream. This setting leads to a grave situation of financial crisis to these farmers. The study further explores that pollution of the Akaki River water bears a great impact on the health of the residents across the adjacent areas across the river. Above all, abortion of women is very common due to the bad smell from the polluted river and direct and indirect consumption of the Akaki River water. And more, asthma and premature deaths associated with industrial pollution are high in the area.

Highly polluting manufacturing industries should undertake initiatives to promote greater environmental responsibility and support a precautionary approach to environmental challenges. The precautionary strategies would consist of avoiding and reducing waste; using recycling and environmentally friendly disposal systems; conserving natural resources by using raw materials and energy responsibly; and using environmentally friendly technology in research and production. By doing so, companies would increase safety in the workplace and protect the environment and the local communities. Responsible Corporate Environmental Governance, therefore, is a must for sustainable and healthy development.

Discussion

Corporate concern in corporate environmental responsibility

Corporates need to feel responsibility beyond return to shareholders to include an acknowledgment of its responsibilities to a broad range of stakeholders throughout society such as employees, customers, business partners, communities, and the environment. Big corporates need to have faith in the idea that not only public policy but companies, too, should take responsibility for environmental and social issues in their sphere. They should seek for the responsible action to be undertaken for the environmental protection as well as meeting self-interest beyond the legal compliance (Grossman Citation2005).

A joint study by Addis Ababa and Oromia EPA Bureaus uncovered that manufacturing industries in Addis Ababa lack the self-commitment to protect the environment. Let alone having self-regulatory mechanisms to acting responsibly, these industries are not even abiding by the government regulatory requirements because CER involves a self-motivated concern for environmental protection beyond legal regime controlling mechanisms (AAEPA & Oromia Region EPA, 2016, Interview).

Compliance with the national and international environmental protection regulatory frameworks is, without a doubt, an indispensable for the protection of the natural environment. The literature on CER shows that corporates in the developed world are moving beyond the compulsory legal requirements for the protection of the environment which they consider it as working for a good corporate profile for their business (Khanna and Anton Citation2002; Li Citation2006). However, back here in the developing countries such as Ethiopia, many corporations are not responsible for the environment. Corporates do not tell the correct information about the share of their business to the environmental pollution nor do they have the facility to measure the impact of pollution (AAEPA, 2016, Interview).

Corporate environmental responsibility in action?

According to the AAEPA Environmental Protection and Law Enforcement Department, it is hardly possible to find a company completely meeting the government environmental regulatory requirements. Almost all the Manufacturing Industries lack the comprehensive effluent treatment mechanism thus failing to meet the government regulatory standard. However, there are few companies taking the environmental protection to their front agenda and working toward achieving this goal (AAEPA Environmental Protection and Law Enforcement Department, 2017, Interview).

This is absolutely against the environmental pollution proclamation 300/2002 Article 4 which states that “no person shall pollute or cause any other person to pollute the environment by violating the relevant environmental standard.” “Person” for this case is the juridical one (corporates). The proclamation on Article 3/1 states that the generation, keeping, storage, transportation, treatment, or disposal of any hazardous waste without a permit from the Authority or the relevant regional environmental agency is prohibited (FDRE Citation2002b).

Recognizing the fact that leather and footwear industries are severely polluting the environment, the authority has penalized some six severely polluting industries in 2015 (AAEPA, 2016, Interview). Awash, Walia, Addis Ababa, Dire, Batu, and New-wing Tanneries were among the manufacturing industries penalized by the authority. The measure which was taken after the assessment was a total closure of the companies. However, the decision to stay was just a matter of a few days. The companies returned to operation with a warning not to further pollute the river. The decision was lifted on conditions of building wastewater treatment plant, monitoring emission, and establishing an internal environmental unit and environmental management system (AAEPA, 2017, Interview).

What is more, the penalty for breach of environmental law itself could also be one reason for the low performance of manufacturing industries on protecting the environment. Environmental Pollution Control Proclamation No. 300/2002 Article 12/1/b imposes a punishment for the environmental offenses in the case of a juridical person, “to a fine of not less than 10,000 Birr and not more than 20,000 Birr” (FDRE Citation2002b). Therefore, these companies prefer to discharge their industrial effluent directly to the river than incurring a higher cost for waste treatment plant erection because of the small amount of the fine coupled with low monitoring and assessment from government organs.

Compliance to the government policies

Complying with government regulatory standards and moving beyond these compulsory requirements is not free lunch. According to Desjardins (Citation1998), CER recognizes that business is always going to have a challenge of balancing profitability with the obligations of ethics – helps to set minimum requirements. But beyond the minimum of what we must do there is a side of ethics which talks about doing good and actually going beyond the minimum target. Furthermore, it is the ability of a company to improve its profits and environmental performance simultaneously through resource conservation and pollution control strategies (Desjardins Citation1998, 825–838). However, in practice, corporates in the developing world are usually thinking of now not the future (Nukpezah Citation2010).

Effluent wastes being discharged from such industries without treatment can carry toxic heavy metals and organics that are harmful to the plant and animals as well as humans coming in contact with it. Concerning this issue, studies conducted by AAEPA have confirmed the dangerous extent of heavy metal contamination of vegetables being grown with irrigation of polluted Akaki River water. This indicates that the disposal of untreated wastes is polluting the rivers in the area and has great potential to affect the health of the residents and the city at all, as the vegetables grown in the area have been distributed over the city (own survey, 2017, Eshetu Citation2012).

Data from AAEPA further demonstrate that more than 40% of Addis Ababa’s vegetable supply comes from urban agriculture produced using the polluted rivers in Addis Ababa. The literature on this issues revealed that some heavy metals like chrome, which have high potential to cause cancer, have been found in sample vegetables. According to a study by Van Rooijen and Taddesse (Citation2009), the concentration of metallic elements in the leaf of vegetables produced using the Akaki River water is significant and could cause the outbreak of several diseases such as diarrhea, and water-borne diseases, most common in the city and let people prone to cancer. Regarding the impacts of pollution from the industry, Aregawi (Citation2014) further articulated that local residents and vegetable farmers are among the highly vulnerable groups to industrial pollution-related health and economic problems ().

Table 6. Trace metal content in vegetable leafs in Addis Ababa

According to Oromia region EPA, manufacturing industries which fail to fulfill environmental regulatory standards in the times of inspection have been receiving warning and punishments from the authority. However, predominantly, old aged and high-profile polluting industries remained defiant to the environmental laws and challenge the EPA organs (Oromia EPA Citation2017).

The finding of the research also uncovered that there is no single manufacturing company entirely conformed to the requirements as far as the maximum permissible limits are concerned. Completely conforming to the requirement is not that much easy though. But there are very few large- and medium-scale manufacturing industries nearly conforming to the government requirements. As shown in the previous sections and observed during the survey, local market-oriented beverage companies better perform on protecting the environment while the absolute majority of industries prefer to overexploit the local environment and win economic benefit. This is utterly against the Principles of Sustainable Development as well as CER.

Use of state of the art technology and effluents monitoring from the source

Replacing old and energy consuming technology is a large contribution to pollution reduction on the environment. But this is not a culture in Ethiopia both in private and in public institutions. The majority of industries asked about replacing obsolete technologies with new one self-confessed that they are not applying this technique. Only a few companies agreed that they continually updated their old machines with new technologies. Environmental Protection Head of KK textile factory told me in an interview that very old machines consume high energy usually from coal and oil. Those obsolete machines release high industrial waste to the surrounding environment in the air or ground. Releasing huge amount of waste coupled with the absence of treatment plant causes environmental pollution. Thus, updating outdated machines could be one way to reduce urban environmental degradation.

As part of the responsible environmental management system, manufacturing industries are expected to monitor effluents from industrial activities. In the survey, many companies claimed they control toxic effluents through the course of industrial operation. Majority of the respondents responded that their industrial effluents are monitored from the source. In spite of this, however, the concept of separating waste at source and pollution control and resource conservation initiatives undertaken by manufacturing industries is not prevalent. For instance, Dire Leather Industry responded as they monitor effluents from the operation. However, a study by AAEPA shows that biochemical oxygen demand was about 55,950 mg/L and the chemical oxygen demand measured 79,540 mg/L compared to 200 and 500 mg/L national limit respectively. This also implies that corporate policy issues are not being translated well into pollution control and resource conservation measures. Effluents are not managed and identified depending on the magnitude of their toxicity (AAEPA, 2016, Interview).

Regarding this issue, the prevention of industrial pollution council of ministers regulation on Article 4/1 declares that:

a factory subject to this regulation shall prevent or if that is not possible, shall minimize the generation of every pollutant to an amount not exceeding the limit set by the relevant environmental standard and dispose of it in an environmentally friendly sound manner (FDRE, Citation2008)

In addition, the Ethiopian government has delivered environmental standards for every pollutant emissions to be in line with these maximum permissible limits. Given these environmental standards, companies are required to release industrial waste which falls within the permissible limit. In practice, however, this regulation is not actually being implemented. Studies by Eshetu (Citation2012), Damtie and Kebede (Citation2012), and Aregawi (Citation2014) revealed that environmental laws are not effectively combating pollution from the Industry.

For instance, Addis Ababa leather factory replied to this question during the survey as it conforms the government regulatory requirements. But the laboratory analysis from wastewater released by this company to the Akaki River shows that availability of oxygen in the water (DO) was only 0.7 mg/L which is far below the national permissible limit ≥7 mg/L (as measured by AAEPA, 2016, Interview) implying the water is very badly polluted and cannot support life totally. Besides according to AAEPA (2016, Interview), the absolute majority of large- and medium-scale manufacturing industries do not record the amount of energy and resources they used and the amount of industrial waste they release to the environment.

Summary

Even though the establishment of industries in Addis Ababa dates back long years, industries which have standardized waste treatment and disposal system are very few. The majority of large- and medium-scale industries such as Textile, Beverage, Leather, and Chemical industries have large pollution sources during production. However, the majority of them do not identify the type of waste during production and have no standardized Effluent Treatment Plant system. Treatment plants in operation are mainly primary level which is built for the purpose of avoiding penalties in the course of an inspection by EPA organs. Otherwise, many industries release their effluents to nearby rivers.

Following majority of highly polluting industries located near or on the Akaki River Basin, and because these industries are not managing their waste and protecting the environment, the entirety of the river system is polluted. The entire river system is known for extremely bad smell because of polluted air environment. As I observed some parts of the study area, the bad smell is irresistible for a while let alone living for entire life along there. However, inside Addis Ababa, because the city is not a planned one, a considerable number of people live following the Akaki River Basin system. These people are prone to several kinds of diseases. Moreover, the river water is utilized along the adjacent Oromia region and even beyond the Akaki River Basin system. The social economic and health impact of the polluted Akaki river water is huge across the area.

Unfortunately, in Addis Ababa, high-profile polluting industries’ (Textile and Leather & Footwear) final product destinations are foreign markets. Hence, two important factors could make the corporate environmental governance challenging. First, because these firms are major sources of foreign exchange for the nation thus easy pressure from the government, and second, these kinds of corporates would not compete for reputation in the local community due to foreign demand for their products.

As a requirement for operation, large- and medium-scale manufacturing industries in Ethiopia have environmental protection policies. These policies are overambitious and never fully implemented by the absolute majority of corporates and prepared for the usual report to the EPA organs. Corporate environmental protection has not been a widely accepted concept so far. Many companies treat it as an additional burden. A few local market-oriented beverage companies have a better understanding of environmental issues and are therefore more likely to protect the environment and disclose information at least for economic purpose.

Recommendations

Taking into account the discussions made and conclusions drawn, the following suggestions are forwarded both for the government and for the corporates:

A mixed system – both command and control regulations (currently working) plus corporate voluntary codes – rather than over-reliance on only one should be employed to achieve environmental sustainability.

Altering the lip-service, fighting pollution from the industry needs strong commitment because it could incur immediate financial cost both for the regulator (the government) and for the industry. But the regulator should act as real environmental safeguarding agent stepping forward from the double-standard position.

A strong communication, teamwork, monitoring, and inspection among and between hierarchical EPA organs.

Integration between Licensing and monitoring institutions (such as Ethiopian Investment Commission (EIC), Ministry of Transport (MoT), MoI) and Environmental Protection Departments in different government sectors as well as the EPA organs.

A deeper transformation of vertical and horizontal institutional structure in the government EPA organs.

Manufacturing Industries with high pollution profile should strive for the real adoption of voluntary environmental management systems and environmental codes of practice. This should also be encouraged by the government EPA organs.

Institutionalizing good environmental management culture within the Manufacturing Industries. The government using research and training method should encourage industries to establish best environmental practices in the industry including to strive to protect the environment beyond than mere compliance and pollution prevention.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Aregawi, T. 2014. “Peculiar Health Problems Due to Industrial Wastes in Addis Ababa City: The Case of Akaki Kality Industrial Zone.” Unpublished master’s thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa Ethiopia.

- Damtie, M., and S. Kebede. 2012. “The Need for Redesigning and Redefining Institutional Roles for Environmental Governance in Ethiopia.” In Movement for Ecological Learning Community Action. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Desjardins, J. 1998. “Corporate Environmental Responsibility.” Journal of Business Ethics 17 (8): 825–838. doi:10.1023/A:1005719707880.

- Douglass, T. J. 1999. “Performance Implication of Incorporating Natural Environmental Issues into The Strategic Planning Process: An Empirical Assessment.” Journal of Management Studies 35 (2): 241–262.

- Eshetu, F. 2012. “Physico-Chemical Pollution Pattern in Akaki River Basin, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.” Unpublished master’s thesis, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden.

- FDRE (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia). 1997. Environmental Policy of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: FDRE.

- FDRE (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia). 2002a. Environmental Impact Assessment Proclamation No. 299/2002. Addis Ababa: FDRE.

- FDRE (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia). 2002b. Environmental Pollution Control Proclamation No.300/2002. Addis Ababa: FDRE.

- FDRE (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia). 2008. Prevention of Industrial Pollution Regulation 159/2008. Addis Ababa: FDRE.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Constitution. 1995. Article 44 (1) FDRE Constitution Article 92 (1).

- Feyisa, A. 2016. Environmental Impact Assessment in Ethiopia: A General Review of History, Transformation, and Challenges Hindering Full Implementation. Ambo, Ethiopia: Ambo University, Department of Natural Resources Management.

- Getu, M. 2013. Defiance of Environmental Governance: Environmental Impact Assessment in Ethiopia.

- Grossman, H. A. 2005. “Refining the Role of the Corporation: The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Shareholder Primacy Theory.” Deakin Law Review 2.

- Ibrahim, A. 2009. A Human Rights Approach to Environmental Protection: The Case of Ethiopia. Florida: St. Thomas University, School of Law Miami.

- Janka, D. G. 2007. “Participation of Stakeholders in Environmental Impact Assessment Process in Ethiopia: Law and Practice.” JimmaUniversity Law Journal 4 (1).

- Khanna, A. M., and W. Anton. 2002. “What Is Driving Corporate Environmentalism: Opportunity or Threat?” Corporate Environmental Strategy 9 (4): 409–417.

- Kumie, A. 2009. Air Pollution in Ethiopia: Indoor Air Pollution in a Rural Butajira and Traffic Air Pollution in Addis Ababa. Addis Ababa University press.

- Langeweg, F., H. Hilderink, and R. Maas (2000). Urbanisation, Industrialisation and Sustainable Development. RIVM report 402001015. Retrieved from: http://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/cms/publicaties/402001015.pdf

- Li, X. 2006. “Environmental Concerns in China: Problems, Policies, and Global Implications.” International Social Science Review 81 (1/2): 43–57.

- MEFCC. 2005. “Review of the Status of Akaki River Water Pollution.” Unpublished report. Addis Ababa.

- Melese, E. 2009. Non-Financial Reporting: Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Reporting, an Ethiopian Case. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Nukpezah, D. 2010. Corporate Environmental Governance in Ghana: Studies on Industrial Level Environmental Performance in Manufacturing and Mining. Ghana.

- Oromia regional state Environmental protection authority. 2017. Laboratory analysis result of Leather industries in and around Addis Ababa city: unpublished report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Tedla, S., and L. Kifle. 1998. Environmental Management in Ethiopia: Have The National Conservation Plans Worked? Organization for Social Science Research in Eastern and Southern Africa.

- Van Rooijen, D., and G. Taddesse 2009. “Urban Sanitation and Wastewater Treatment in Addis Ababa in the Awash Basin, Ethiopia.” 34th WEDC International Conference, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- WAN Yongkun, DONG Suocheng, and MAO Qiliang et al. 2013. “Causes of Environmental Pollution after Industrial Restructuring in Gansu Province.” Journal of Resources and Ecology 4 (1): 88–92.