ABSTRACT

Purpose of the research: To identify the gaps between the rhetoric and reality of the role of citizen participation and its role in maintenance and monitoring of heritages and resources (including biodiversity monitoring), we analyzed the discourse of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS) at municipality level.

Methods: As an analytical framework, text mining is applied to interviews of officers at the municipal level of GIAHS in Noto which was amongst the first sites in Japan. The identification of such gap is critical for sustainability and to prevent conflicts from tourism, agriculture or educations.

Results: The results reveal that (1) there is a gap between the official goals of that designation at the international level and local needs, (2) role of citizens is emphasized in the applications and action plans at rhetorical level but remain rather limited in practice and that (3) municipalities composing the GIAHS often have different priorities, even within the very same GIAHS sites, some municipalities even calling themselves “just a transition point to other destination municipalities.”

Conclusions: It is critical for municipal officers to collaborate with various stakeholders, especially citizens. As such, citizen science is a bottom-up approach to promote biodiversity conservation and facilitate GIAHS managements.

Introduction

The official record explanations for regional certifications or recognitions are frequently bottom-up with rhetoric of local initiatives. However, in reality, it is often spearheaded by a leader or an organization serving as catalyst. This was presumably the case for the Noto peninsula, which was the first registration of the Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) in Japan in June 2011. The official record states that the registration process was initiated by the eight local municipalities, which later became nine as a town was added. The efforts were endorsed and recommended by the local branch of United Nations organizations, as well as universities and prefectures, with support from the national government or the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). However, a number of interviewees agreed that in the early stages, the application for GIAHS was primarily led by the national government or a regional branch of the national government. Related efforts are then pursued by the prefecture.

The municipalities who lead and take the official documents usually do not lead the GIAHS applications process. In some cases, they remain passive about its value or the achievement of its objectives. Despite this, municipalities are undoubtedly key players in operationalizing and sustaining the GIAHS scheme as a heritage. Hence, it is important to examine whether the municipalities adopt a more active role in undertaking relevant activities after five years of GIAHS registration. For the Noto peninsula, its GIAHS application highlighted efforts on biodiversity conservation and maintenance of Satoyama cultural landscapes. It mentioned citizen-led monitoring of biodiversity, which is a precondition of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) for GIAHS registration, as part of such efforts. This study examined whether the ideas and practices of the initial GIAHS plan, particularly statements on citizen-led monitoring of biodiversity, are mainstreamed among policymakers at the grassroots level of municipalities, who play a critical role in the sustainability of the system. We interviewed the officers in charge of GIAHS and examined which elements are mainstreamed among the policymakers by analyzing the results quantitatively. This paper is unique in that it applies quantitative methods yet the implications of the findings on municipal strategies are largely qualitative.

Review: globally important agricultural heritage systems

Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems are established under the framework of FAO with the aims of evaluating sustainable agricultural systems cultivated on the basis of regional biodiversity, and promoting community-based agriculture (Koohafkan and Altieri Citation2011). To facilitate community-based sustainable agriculture and biodiversity conservation, GIAHS designations are currently utilized in different regions of the world, with 37 designated sites in 16 countries. The Asia-Pacific region has a relatively large portion of such designations, with 26 GIAHS sites (Evonne, Akira, and Kazuhiko Citation2016). Under the current framework, the value of agricultural heritages is being rediscovered in making and implementing comprehensive local strategies in those regions’ rural areas (Mitchell and Barrett Citation2015; Uchiyama et al. Citation2017a).

Regarding the activities in GIAHS sites, communities focus on research and promotion of the grassroots activities including biodiversity monitoring by citizens. The FAO developed the GIAHS designation (or acknowledged status) with the aim to maintain local agricultural systems and transmit them to future generations. In the official description of the aim of the GIAHS programme, branding or promotion of agricultural products per se is not the primary goal. From the existing literature, it is seen that there are certain products of GIAHS sites which are not destined for market supplies (Chen and Qiu Citation2012) but are shared by local communities and as gifts to families as local resources (Kamiyama et al. Citation2016).

The GIAHS generally focusses on local and bottom-up activities in that the applications are voluntarily done usually by local umbrella organizations or municipalities. In this respect, municipalities need to support their local activities by providing the platforms for decision-making by stakeholders. For such purposes, the collaboration of stakeholders, including international organizations, local municipalities, private companies, and residents, is an urgent task to facilitate local resource management under international designation systems such as GIAHS (Qiu, Chen, and Takemoto Citation2014). Local stakeholders have differing understandings of local resources, and preferred information channels differ among them (Kohsaka, Tomiyoshi, and Matuoka Citation2016). In local resource management with diverse stakeholders, it is crucial towards effective collaboration to visualize and understand the diversity of their understandings and attitudes.

The global change in the conditions of agriculture affects the local landscapes of community-based agriculture. The GIAHS sites are not exceptional, and their landscapes are influenced by global change in this regard (Carmona and Nahuelhual Citation2012). The influence needs to be identified, not only in specific micro-districts, but also in large-scale perspectives involving several local municipalities (Calvo-Iglesias, Fra-Paleo, and Diaz-Varela Citation2009). Area management based on benchmarks, including approaches of citizen sciences, is recommended for GIAHS sites (Koohafkan and Altieri Citation2011). To support indicator-based management, the visualization and evaluation of ecosystem services are conducted in the GIAHS sites with mapping systems based on a geographic information system (GIS) (Barrena et al. Citation2014; Nahuelhual et al. Citation2014). The mapping systems are utilized as a useful tool in participatory approaches of local environmental managements including citizen science approaches (Ramos Citation2010; Larcher et al. Citation2013; Yehong et al. Citation2013; Wachowiak et al. Citation2017; Brown et al. Citation2018). These research results can contribute to collaboration among stakeholders and citizens in developing local policies. Relevant information sharing helps to facilitate local environmental management (Nthunya Citation2002). On the other hand, understanding the expectations and attitudes of local municipalities which facilitate collaboration of stakeholders is required to develop the methods to use the visualized data in local decision-making. For local stakeholders, particularly for citizens, environmental managements have different expectations for resources and future pathways. The analysis of the stakeholders including local communities and citizens is implemented based on qualitative evidence for building basis for consensus (Moran and Rau Citation2016). Furthermore, the conservation efforts are frequently described as “bottom-up” but there are not many empirical analyses which examined the extent of such efforts amongst policymakers and practices.

Often, the main aims of regional designation systems are not identical with the expectations of local stakeholders. A regional designation system does not necessarily aim primarily to promote local tourism or economy but to conserve biodiversity and the local environment. However, aim and expectation are not necessarily trade-offs and local actors often expect a positive effect in promotion of the products and participations (Uchiyama et al. Citation2017b; Kajima, Tanaka, and Uchiyama Citation2017; Kohsaka, Fujihira, and Uchiyama Citation2016). Local culture that forms the socio-ecological landscape in a place is often related to the economic culture in that place (Huggins and Thompson Citation2015). In this regard, involving regional economic strategy and citizen participation is crucial to implementing the conservation of the landscape that is the focus in GIAHS. For example, contributions of Geoparks which is a regional designation managed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in socio-economic development in local areas can be expected in terms of sustainable managements of designation areas (Farsani, Coelho, and Costa Citation2011). In addition to economic development and environmental conservation, maintenance of cultural aspects that underpin the local communities of designation areas need to be considered and to explore appropriate balance with other aspects including economy and environment (Hung et al. Citation2017).

International institutions, including United Nations organizations, are designating the heritage sites. At the implementation phase, however, collaborations of global, national, and local-level stakeholders, including governments and institutions, are necessary (Dempsey and Wilbrand Citation2017). Figuring out what kinds of views or approaches are held by local officers is integral part of the discussion. Furthermore, identifying the status of collaboration between the different spatial scales and among local municipalities needs to be addressed. However, research on the attitudes of local municipalities is limited in number, and methodological frameworks for such research have not been established, neither in a quantitative nor qualitative way. The analysis of interviews of officers at the municipal level is highly relevant to the actual GIAHS operation because municipalities are critical actors, frequently in framing the political agendas and in shaping the landscapes through financial measures such as subsidies. We need to visualize not only the condition of or change in resources but also the attitudes of local municipalities which manage those resources. Local municipalities (and related citizen science approaches mainly in monitoring) play various roles in the management of GIAHS. The roles of local municipalities are paid attention in the bottom-up approach of citizen science in natural resource managements (Little, Hayashi, and Liang Citation2016; Fraser et al. Citation2006).

In prior research, analysis of the minutes of local assemblies, where some of the most formal discussions take place, was conducted to understand the attitudes of the municipalities at official discussions in the municipality assembly of individual GIAHS sites (Kohsaka and Matsuoka Citation2015). This revealed that the attitudes varied, and it can be a cause of conflicts among the municipalities, although it has been implied that there is room for cross-municipality collaboration, based on the study of local resources in the Noto region (Uchiyama and Kohsaka Citation2016). In the Noto GIAHS site, which is composed of several municipalities, relatively large municipalities discussed GIAHS frequently and regarded it as an important factor in their local strategies. Those research results gave an overview of the differences among attitudes of municipalities in GIAHS sites. However, the detailed differences among municipalities, and between local needs and the goals of global institutions, are not fully identified particularly in quantitative terms. There is an obvious need for analysis at less formal level.

Materials and methods

In this research, we interviewed persons in departments related to GIAHS management in the nine municipalities () and then analyzed the results using text analysis. Text analysis has been used in prior research to quantify attitudes about environmental conservation (Iwata, Fukamachi, and Morimoto Citation2011; Iwata, Yumoto, and Morimoto Citation2014; Kohsaka and Matsuoka Citation2015). As a first step, the aggregated texts were analyzed to see attitudes about the overall use of the GIAHS and their relationships to keywords such as tourism, agriculture, fishery, and other relevant concepts. As a second step, we applied the corresponding analysis to the results from officers of the individual municipalities and categorized the results into different groups.

Overall, the population of the municipalities is decreasing (); the largest municipality, Nanao City, has shrunk by approximately 10,000 people in the last 15 years. The trends in numbers of workers in the individual industries are similar between the municipalities, although the percentages of the individual industries workers differ among the municipalities (). The differences in industrial structures can be reflected in the results of the interviews. The percentages of workers in the primary industry have been relatively stable since the year 2000. The percentages for secondary industry workers are decreasing; on the other hand, those for tertiary industry workers are rising.

Semi-structured interviews were implemented in the nine municipalities which compose the Noto GIAHS site. The survey period was from 16 May 2014 to 21 April 2015. Three or four years had passed since the GIAHS designation in 2011, and the municipalities needed to review their policies and plans in that period. They organized their reports relative to the status of the GIAHS site and the activities therein. In this context, the survey could be conducted effectively and efficiently, based on their collected and organized information. We provided the following interview questions:

Why did you decide to apply for the designation?

What are the advantages you can receive in utilization of the GIAHS designation?

What are the disadvantages you can receive in utilization of the GIAHS designation?

How do you implement decision-making?

How do you cooperate with other municipalities?

Do you have any impetus to obtain other regional designations, such as World Heritage, Biosphere Reserve, or Geopark?

In the process of designation, was there any change in the organizational structure or budget in your municipality?

Was there any change in the number of tourists or the attitude of local people?

In the management of the GIAHS site, do any external experts participate in the meetings or activities in your municipality?

What kinds of requests do the local people make regarding the management of the GIAHS?

What kinds of requests do tourists make regarding the management of the GIAHS?

Do you have any strategies for biodiversity conservation, or do you consider biodiversity in other existing strategies?

Did you find any effects on the recognition of your municipality by tourists, or any economic effects in the tourism sector?

We used a text mining software, the KH Coder. We analyzed Japanese nouns in the text of the respondents’ remarks and identified frequencies of appearance of the nouns. We conducted co-occurrence analysis to identify the overall trend for the Noto region, and correspondence analysis to clarify the characteristics of individual municipalities.

As a result of the survey, we obtained text data of 21,445 words from the interviews in the municipalities. To understand the relationships between the GIAHS and local strategies in individual municipalities, we analyzed unique words that describe the overall trends of the Noto region and characteristics of each municipality.

Co-occurrence analysis can be used to visualize relationships of words; using it, we could identify words that were frequently used together with “GIAHS.” The results of the analysis indicate the policies or activities which are related to GIAHS with high priority, thus reflecting differences in attitudes or expectations of local municipalities.

In the text mining approach, correspondence analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis are used to compare and identify the relationships among sentences with similar themes (Weiss et al. Citation2010; Minami and Ohura Citation2015; Hemsley and Palmer Citation2016). Correspondence analysis is utilized to understand the relationships of two dimensions by degree of frequency of words. On the other hand, the main purpose of hierarchical cluster analysis is categorization, and the cluster analysis is not appropriate to apply to the texts without clear clusters. In this research, we used the correspondence analysis to identify the detailed relationships of the two dimensions (Weiss et al. Citation2010), which are “municipalities” and “words mentioned in the municipal assemblies.” In order to apply the correspondence analysis, we prepared the matrix of the degree of frequency of words. is an example of the matrix that shows the degree of frequency of the words including “influence,” “symbiosis,” and “year” in individual municipal assemblies. We made such table by using the results of the interview to conduct the correspondence analysis.

Table 1. Example of the matrix that shows degree of frequency of the words including “influence,” “symbiosis,” and “year” in individual municipal assemblies

Results

In this section, we first show the result of co-occurrence analysis to provide the overall trend for the Noto region. Then, we show the result of correspondence analysis to indicate the characteristics of the individual municipalities.

Results of co-occurrence analysis

The co-occurrence network () shows that the respondents mentioned not only the GIAHS but also other designations such as World Heritage and Biosphere Reserve. Regarding the relationships between GIAHS and the other designations, GIAHS has a relatively strong connection with World Heritage. This result reflects the fact that the Noto region’s traditional event known as Aenokoto is certified as an Intangible Cultural Heritage by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). Aenokoto is a traditional event related to local agriculture and is regarded as one of the cultural resources of the Noto GIAHS site. In this regard, the term ’World Heritage’ is connected with “culture.”

Figure 4. Co-occurrence network of the content of the interviews in the municipalities in the Noto GIAHS site

The term ’tourism’ was frequently mentioned along with “GIAHS;” in , “tourism” is located adjacent to “GIAHS.” The result shows that the municipalities put their efforts into tourism development in the promotion of GIAHS. As the tight connections of ’economy“, ”effect“, and ”tourism‘ imply, they expect an economic effect from tourism development by using GIAHS. Intensive tourism development can be a cause of conflicts between development and the local environment. However, in the Noto region, where the population is rapidly decreasing and aging, increasing the number of visitors is regarded as an urgent issue. In terms of sustainable regional managements, balanced efforts on tourism development and environmental conservation are needed in the maintenance of GIAHS sites where an increase in the number of visitors is expected to help tackle the issues of shrinking societies.

The term “region” is also strongly connected with “GIAHS,” and relates to ’agriculture“ and ”culture“ through ”local area.’ The term ’local area‘ reflects the existence of individual small villages and districts with unique characteristics. These are widely distributed throughout the municipalities of the Noto region. The concepts of Satoyama and Satoumi, or socio-ecological production landscapes, are shared by the Noto municipalities. In this context, individual municipalities try to develop their unique regional strategies based on differentiated local areas.

The concept of Satoyama closely relates to agriculture and forestry, and Satoumi relates to fishery for exact definition (JSSA Citation2010). In the Noto region’s application for the GIAHS designation, Satoyama and Satoumi were emphasized about equally. However, the connection of GIAHS with fishery seems relatively weak in the co-occurrence network (): the distance between the terms ’GIAHS“ and ”fishery“ is greater than the distance between ”GIAHS“ and ”agriculture.“ These relationships reflect the fact that the sections of GIAHS in the municipalities are often located in the sections related to agriculture, and those sections have difficulty collaborating with fishery sections. However, Satoyama and Satoumi make an integrated system that works seamlessly in wider regions that encompass forest, agriculture, and coastal areas. This result implies that sectionalism exists in the municipalities of the Noto GIAHS site, and this can be an issue in the integrated management of the site.

In the response from the local municipal officers, there were limited reference to the role of citizens participation, citizen science. Nor were limited references to their contribution to the monitoring of biodiversity. Although the participatory monitoring of biodiversity is a fundamental factor of the GIAHS management, the interests and concerns of the local municipalities seem not directly related to the participatory monitoring activities of citizens.

The summary of the results is provided in the following list. The main aim of the GIAHS is not branding of products or tourism development. However, the officers of the municipalities frequently mentioned tourism development and economic effect in the interviews. Specifically, we identified the following attitudes by conducting the co-occurrence network analysis:

GIAHS is regarded as a heritage designation that relates to World Heritage through traditional agricultural events such as Aenokoto.

Tourism development using GIAHS is regarded as an urgent issue due to the region’s socio-economic background factors such as depopulation and aging.

The uniqueness of small villages and districts in the municipalities is a focus in the management and promotion of the Noto GIAHS sites.

There is a potential trend that the agricultural, forestry and fishery elements will be emphasized more than other ceremonial or scientific ones because of the section in charge of GIAHS. This is not unnatural given that the Satoyama concept, which strongly relates to agriculture and forestry, is frequently emphasized in the management of the Noto GIAHS sites. This overall trend, if not bias, needs to be noted in the interpenetration of the analysis result of individual municipalities.

Results of the correspondence analysis

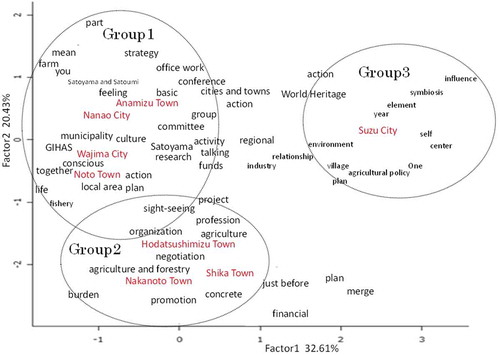

At the individual municipality level, we conducted the correspondence analysis to identify the characteristics of them. In , the terms that reflect the characteristics of the individual municipalities are shown near their names. If a municipality name appears near another municipality name, this shows similarity in the results of the interviews with the officers of those municipalities. Regarding the terms related to citizen science and participatory approaches did not appear in . This result indicates that biodiversity monitoring by citizens was not active in the Noto region, although the municipalities needed to promote the participatory monitoring activities. The municipalities can be categorized by their locations in the scatter plot of , and the understanding of the current situations of the municipalities can be facilitated by the result of categorization. Based on the categorization, three groups are identified. The differences in the interests and priorities of the municipalities are not trivial, and the characteristics of the individual groups are provided in the following paragraphs.

Figure 5. Scatter plot of correspondence analysis of the content of the interviews in the municipalities in the Noto GIAHS site

Group 1. Wajima City, Anamizu Town, Nanao City, Noto Town

The terms “Satoyama and Satoumi,” “fishery,” “action plan,” and “farm” appeared relatively frequently in the interviews and characterized the municipalities of group 1 (). The results reflect that the fisheries in Wajima City, Anamizu Town, and Nanao City are relatively active, and that Nanao City has started to make an action plan for the GIAHS. Suzu City is the first municipality to make an action plan for the Noto GIAHS site, and Nanao City is the second. In the result of the co-occurrence network analysis () showing the overall trend for the Noto region, the terms ’agriculture“ and ”Satoyama and Satoumi“ are not directly connected. On the other hand, the municipalities of group 1 are located near agriculture-related terms such as ”farm“ and “Satoyama and Satoumi“. This result shows that the municipalities seem to promote their agriculture under the concepts of Satoyama and Satoumi.

Group 2. Nakanoto Town, Shika Town, Hodatsushimizu Town

In , the terms ’agriculture and forestry’ and ’promotion“ are located close to the names of the municipalities. This result reflects the fact that agriculture in group 2 is relatively active as compared with group 1. However, fishery is not active in group 2, and the frequency of appearance of the term ”Satoyama and Satoumi“ in the group 2 interviews is relatively low. The three municipalities of group 2 have relatively few tourism resources and have difficulty in promoting themselves to visitors. The term ”promotion‘ is located near these municipalities’ names because that is their urgent issue in the utilization of GIAHS.

Group 3. Suzu City

Suzu City has relatively unique policies and activities regarding the Noto GIAHS site. The traditional agricultural event, Aenokoto, which is certified as an Intangible Cultural Heritage in Suzu City, is famous among tourists. The municipality has a relatively large number of cultural resources related to GIAHS and is characterized by terms including ‘village“, ”centre“, ”one“, and ”agricultural policy“. Unlike other municipalities, the terms ”centre“ and ”one“ appear for group 3 in because Suzu City is the first municipality which had the secretariat for the Noto GIAHS site. Suzu City is doing promotion and management of GIAHS based on the villages distributed in its administrative area, and thus ”village“ appears as a characteristic term.

Discussion and conclusion

We conducted the text-analysis as a quantitative approach to the texts of the interviews of the officers of the local municipalities. As a first step, the aggregated texts were analyzed to see the overall use of the GIAHS and the municipalities’ relationships with the keywords ’ tourism,’ “agriculture,” “fishery,” and other relevant concepts. As a second step, we applied the corresponding analysis to the results for officers of the individual municipalities and categorized the results into different groups. We aimed to visualize the overall trends (step 1) and the differences and trends of individual municipalities within the same site of the Noto GIAHS (step 2).

From the results of step 1, the gap between the official goals of the GIAHS designation at the international level and the local needs at the municipality level was identified. The official goals emphasize the heritage aspects, while the local trends are linked strongly with direct benefits to tourism, the economy, and other elements. As a first step to address the issues related to that gap, understanding different value systems of local municipalities and international organizations that manage GIAHS designation is necessary.

Furthermore, it was identified from step 2 that municipalities composing the GIAHS frequently have different interests and priorities, even within the very same GIAHS site. The different interests and priories are probably related to the cultural and agricultural resources and the municipal industrial structures. For example, municipalities with fewer cultural and agricultural resources had fewer interests in GIAHS activities, calling themselves ’just a transition point to other destination municipalities’. The agricultural and cultural resources that are components of Noto GIAHS are located in every municipalities in Noto region, and the networks of the resources can attract visitors. However, the location of the resources is not fully shared among municipalities, and communication platform to utilize the networks of the resources is not developed. In this regard, the communication platform and strategic collaboration of municipalities are needed to enhance the potential of heritage systems in the region.

Policymakers at the municipal level are generally interested in harnessing GIAHS recognition in local management strategies, including strategies to promote tourism in Japan. In managing GIAHS sites, it is critical for municipal officers to collaborate with various stakeholders, especially citizens. As such, citizen science is a potential bottom-up approach to promote biodiversity conservation and develop GIAHS sites as a tourist destination. Citizen-led monitoring of biodiversity, a prerequisite from the FAO for GIAHS registration, was a core thrust of the Noto region during its registration. The participation of citizens, including younger generations, and their role in monitoring was formalized in the Noto GIAHS Action Plan and was re-emphasized when the Action Plan was established for its first period (2011–2015) and when it was revised in 2016.

However, in the present study, elements related to citizen science were scarcely mentioned in the majority of the interviews with municipal officers. The term “monitoring” and “citizen participation” did not appear frequently. This contrasts with what is being emphasized in the initial GIAHS plan and revised action plan of the Noto region. These discrepancies were not prominent in the findings and thus require further evaluation and consideration. The involvement of citizens, which is presently mere rhetoric, should be mainstreamed by policymakers at the municipal level. The quality of biodiversity conservation efforts can be maintained through citizen-led monitoring, and the proper monitoring of biodiversity leads to the maintenance of Satoyama cultural landscapes.

There is a possibility that the staff members of the municipal governments, who are in charge of the GIAHS, are not aware of citizen science programs, although those programs are conducted in the municipalities. As a cause of that situation, it can be frequently seen that the citizen science programs are not directly related to the sections of the municipalities, which are in charge of the GIAHS. The staffs who are in charge of the GIAHS belong to agricultural sections in the municipalities, on the other hand, the citizen science programs are basically under the sections of environmental managements. Information sharing and collaborations between the agricultural sections and the environmental managements sections are challenging tasks in the municipalities, and this situation can be a main cause of the municipal GIAHS staffs’ low awareness of the citizen science programs. Regarding the countermeasures to connect the GIAHS staffs and the citizen science programs, facilitation of collaborations between agricultural sections and environmental managements sections, implementation of educational programs for the GIAHS staffs to learn citizen science, and sharing knowledge related to the GIAHS with the staffs of environmental managements sections can be conducted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barrena, J., L. Nahuelhual, A. Báez, I. Schiappacasse, and C. Cerda. 2014. “Valuing Cultural Ecosystem Services: Agricultural Heritage in Chiloé Island, Southern Chile.” Ecosystem Services 7: 66–132. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.12.005.

- Brown, G., C. McAlpine, J. Rhodes, D. Lunney, R. Goldingay, K. Fielding, S. Hetherington, et al. 2018. “Assessing the Validity of Crowdsourced Wildlife Observations for Conservation Using Public Participatory Mapping Methods.” Biological Conservation 227: 141–151. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2018.09.016.

- Calvo-Iglesias, M. S., U. Fra-Paleo, and R. A. Diaz-Varela. 2009. “Changes in Farming System and Population as Drivers of Land Cover and Landscape Dynamics: The Case of Enclosed and Semi-Openfield Systems in Northern Galicia (Spain).” Landscape and Urban Planning 90 (3): 168–177. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2008.10.025.

- Carmona, A., and L. Nahuelhual. 2012. “Combining Land Transitions and Trajectories in Assessing Forest Cover Change.” Applied Geography 32 (2): 904–915. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.09.006.

- Chen, B., and Z. Qiu. 2012. “Consumers‘ Attitudes Towards Edible Wild Plants: A Case Study of Noto Peninsula, Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan.” International Journal of Forestry Research 2012: 1–16. doi:10.1155/2012/872413.

- Dempsey, K. E., and S. M. Wilbrand. 2017. “The role of the region in the European Landscape Convention.” Regional Studies, 51 (6), 909–919. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1144923

- Evonne, Y., N. Akira, and T. Kazuhiko. 2016. “Comparative Study on Conservation of Agricultural Heritage Systems in China, Japan and Korea.” Journal of Resources and Ecology 7 (3): 170–179. doi:10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2016.03.004.

- Farsani, N. T., C. Coelho, and C. Costa. 2011. “Geotourism and Geoparks as Novel Strategies for Socio‐Economic Development in Rural Areas.” International Journal of Tourism Research 13 (1): 68–81. doi:10.1002/jtr.v13.1.

- Fraser, E. D., A. J. Dougill, W. E. Mabee, M. Reed, and P. McAlpine. 2006. “Bottom up and Top Down: Analysis of Participatory Processes for Sustainability Indicator Identification as a Pathway to Community Empowerment and Sustainable Environmental Management.” Journal of Environmental Management 78 (2): 114–127. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.04.009.

- Hemsley, B., and S. Palmer. 2016. “Two Studies on Twitter Networks and Tweet Content in Relation to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Conversation, Information, and ‘Diary of a Daily Life’.” Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 227: 41–47.

- Huggins, R., and P. Thompson. 2015. “Culture and Place-Based Development: A Socio-Economic Analysis.” Regional Studies 49 (1): 130–159. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.889817.

- Hung, K., X. Yang, P. Wassler, D. Wang, P. Lin, and Z. Liu. 2017. “Contesting the Commercialization and Sanctity of Religious Tourism in the Shaolin Monastery, China.” International Journal of Tourism Research 19 (2): 145–159. doi:10.1002/jtr.v19.2.

- Iwata, Y., K. Fukamachi, and Y. Morimoto. 2011. “Public Perception of the Cultural Value of Satoyama Landscape Types in Japan.” Landscape and Ecological Engineering 7 (2): 173–184. doi:10.1007/s11355-010-0128-x.

- Iwata, Y., T. Yumoto, and Y. Morimoto. 2014. “Can Satoyama Offer a Realistic Solution for a Low Carbon Society? Public Perception and Challenges Arising.” In Designing Low Carbon Societies in Landscapes, edited by Nobukazu Nakagoshi and Jhonamie A. Mabuhay, 89–108. Tokyo, Japan: Springer Japan.

- Japan Satoyama Satoumi Assessment (JSSA). 2010. Satoyama-Satoumi Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes of Japan – Summary for Decision Makers. Tokyo, Japan: United Nations University.

- Kajima, S., Y. Tanaka, and Y. Uchiyama. 2017. “Japanese Sake and Tea as Place-Based Products: A Comparison of Regional Certifications of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems, Geopark, Biosphere Reserves, and Geographical Indication at Product Level Certification.” Journal of Ethnic Foods 4 (2): 80–87. doi:10.1016/j.jef.2017.05.006.

- Kamiyama, C., S. Hashimoto, R. Kohsaka, and O. Saito. 2016. “Non-Market Food Provisioning Services via Homegardens and Communal Sharing in Satoyama Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes on Japan’s Noto Peninsula.” Ecosystem Services 17: 185–196. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.01.002.

- Kohsaka, R., and H. Matsuoka. 2015. “Analysis of Japanese Municipalities with Geopark, MAB, and GIAHS Certification.” SAGE Open 5 (4): 1–10. doi:10.1177/2158244015617517.

- Kohsaka, R., M. Tomiyoshi, and H. Matuoka. 2016. “Tourist Perceptions of Traditional Japanese Vegetable Brands: A Quantitative Approach to Kaga Vegetable Brands and an Information Channel for Tourists at the Noto GIAHS Site.” In Aquatic Biodiversity Conservation and Ecosystem Services, edited by Shin-ichi Nakano,Tetsukazu Yahara, and Tohru Nakashizuka, 109–121. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Kohsaka, R., Y. Fujihira, and Y. Uchiyama. 2016. “Impact of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems on Local Areas: Analysis on Prices of Local Agricultural Products with Geographical Indication, in Otemon University Venture Business Research Institute, Promotion of Primary Producers’ Diversification into Processing and Distribution (Sixth Sector Industrialization) in Local Agriculture.” Otemon University Press, 1–24. in Japanese.

- Koohafkan, P., and M. Altieri. 2011. “A Methodological Framework for the Dynamic Conservation of Agricultural Heritage Systems” Land and Water Division, The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations 1–59.

- Larcher, F., S. Novelli, P. Gullino, and M. Devecchi. 2013. “Planning Rural Landscapes: A Participatory Approach to Analyse Future Scenarios in Monferrato Astigiano, Piedmont, Italy.” Landscape Research 38 (6): 707–728. doi:10.1080/01426397.2012.746652.

- Little, K. E., M. Hayashi, and S. Liang. 2016. “Community-Based Groundwater Monitoring Network Using a Citizen Science Approach.” Groundwater 54 (3): 317–324. doi:10.1111/gwat.2016.54.issue-3.

- Minami, T., and Y. Ohura. 2015. “How Student‘S Attitude Influences on Learning Achievement?-An Analysis of Attitude-Representing Words Appearing in Looking-Back Evaluation Texts.” International Journal of Database Theory and Application 8 (2): 192. doi:10.14257/ijdta.2015.8.2.13.

- Mitchell, N. J., and B. Barrett. 2015. “Heritage Values and Agricultural Landscapes: Towards a New Synthesis.” Landscape Research 40 (6): 701–716. doi:10.1080/01426397.2015.1058346.

- Moran, L., and H. Rau. 2016. “Mapping Divergent Concepts of Sustainability: Lay Knowledge, Local Practices and Environmental Governance.” Local Environment 21 (3): 344–360. doi:10.1080/13549839.2014.963838.

- Nahuelhual, L., A. Carmona, P. Laterra, J. Barrena, and M. Aguayo. 2014. “A Mapping Approach to Assess Intangible Cultural Ecosystem Services: The Case of Agriculture Heritage in Southern Chile.” Ecological Indicators 40: 90–101. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.01.005.

- Nthunya, E. 2002. “The Role of Information in Environmental Management and Governance in Lesotho.” Local Environment 7 (2): 135–148. doi:10.1080/13549830220136445.

- Qiu, Z., B. Chen, and K. Takemoto. 2014. “Conservation of Terraced Paddy Fields Engaged with Multiple Stakeholders: The Case of the Noto GIAHS Site in Japan.” Paddy and Water Environment 12 (2): 275–283. doi:10.1007/s10333-013-0387-x.

- Ramos, I. L. 2010. “Exploratory Landscape Scenarios’ in the Formulation of ‘Landscape Quality Objectives.” Futures 42 (7): 682–692. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2010.04.005.

- Uchiyama, Y., and R. Kohsaka. 2016. “Cognitive Value of Tourism Resources and Their Relationship with Accessibility: A Case of Noto Region, Japan.” Tourism Management Perspectives 19: 61–68. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2016.03.006.

- Uchiyama, Y., Y. Fujihira, H. Matsuoka, and R. Kohsaka. 2017b. “Tradition and Japanese Vegetables: History, Locality, Geography, and Discursive Ambiguity.” Journal of Ethnic Foods 4 (3): 198–203. doi:10.1016/j.jef.2017.08.004.

- Uchiyama, Y., Y. Tanaka, H. Matsuoka, and R. Kohsaka. 2017a. “Expectations of Residents and Tourists of Agriculture-Related Certification Systems: Analysis of Public Perceptions.” Journal of Ethnic Foods 4 (2): 110–117. doi:10.1016/j.jef.2017.05.003.

- Wachowiak, M. P., D. F. Walters, J. M. Kovacs, R. Wachowiak-Smolíková, and A. L. James. 2017. “Visual Analytics and Remote Sensing Imagery to Support Community-Based Research for Precision Agriculture in Emerging Areas.” Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 143: 149–164. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2017.09.035.

- Weiss, S. M., N. Indurkhya, T. Zhang, and F. Damerau. 2010. Text Mining: Predictive Methods for Analyzing Unstructured Information. New York, USA: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Yehong, S., W. Jing, and L. Moucheng. 2013. “Community Perspective to Agricultural Heritage Conservation and Tourism Development.” Journal of Resources and Ecology 4 (3): 258–266. doi: 10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2013.03.009.