?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

As a market-based instrument of transportation demand management, congestion charge can not only effectively reduce traffic congestion, but also improve air quality. However, due to its low public acceptability, this policy only has a few urban practices. As one of the fast-growing metropolises in emerging economies that are facing both traffic congestion and industrial pollution problems, Beijing is now considering the feasibility of implementing congestion charging. Some researchers address that though people with strong environmental concerns are more prone to support congestion charges, the associations between environmental concerns and support for congestion charges are context-dependent. A survey was conducted in Beijing in 2016 to understand how the pollution context in cities of emerging economies affects these associations. We find that the acceptability in Beijing is 33%, and expected policy effects and environmental concerns are the most important impact factors. Due to the influence of the regional industrial pollution context, most residents in Beijing do not consider congestion charge to be an effective way to tackle air pollution. Under these circumstances, even if the public environmental concerns, in general, are high and congestion charges are “marketed” as environmental policies, there is no guarantee that policy support will rise.

Introduction

The coupling of motorization and urbanization has brought about enormous environmental and economic problems, particularly in cities of emerging economies. Such as in Beijing, the number of motor vehicles increased from 1.2 million in 2000 to 5.6 million in 2015; and social costs including the costs of congestion and pollution that induced by motorized transportation are equivalent to about 7.5% – 15.0% of Beijing’s GDP (Creutzig and He Citation2009). At the same time, although local industrial pollution has been well controlled, due to the uneven development of the surrounding area, Beijing’s air quality is still severely affected by the transmission of industrial pollution in the region.

In 2010, to alleviate traffic congestion, the Beijing Municipal Government began to study the feasibility of implementing congestion charges for heavily congested sections or areas. In 2013, Beijing issued the Clean Air Action Plan (2013–2017) and identified critical tasks to improve Beijing’s air quality. One of the tasks is to study and formulate congestion charge schemes. Since then, congestion charging has become a possible environmental policy option in the future.

Congestion charge, a potentially powerful tool for alleviating congestion and environmental problems, has gained broad support from economists and urban planners worldwide. Several cities such as Singapore (Goh Citation2002), London (Atkinson et al. Citation2009), and Stockholm (Eliasson Citation2008) have successfully implemented the congestion charge. So far, however, policy practice has been minimal, and one of the main challenges is public acceptability (Santos, Behrendt, and Teytelboym Citation2010).

A higher public support rate indicates a higher probability that the policy would meet the Kaldor-Hicks efficiency criterion, which states that those who would benefit from the policy would be able to compensate fully those who would lose and still be better off (Boardman et al. Citation2012). Moreover, higher public support also helps to reduce the cost of policy implementation and promote the smooth implementation of the policy. Therefore, governments attach great importance to public support. Researches in China also show that public attitudes have a significant impact on policy formulation and implementation (Yu Citation2015; Zhang and Li Citation2016; Zheng et al. Citation2013).

Researches show that the main influencing factors of acceptability of congestion charges include expectations of policy effects on congestion, environment and personal outcome (Jaensirisak, Wardman, and May 2005; Schaller Citation2010; Schuitema, Steg, and Rothengatter Citation2010), sound transit system (Kottenhoff and Freij Citation2009), revenue use (Schuitema and Steg Citation2008), and attitudinal factors such as environmental concerns (Eliasson and Jonsson Citation2011), trust in public agencies, and equity (Eliasson and Mattsson Citation2006).

People with strong environmental concerns are more prone to support congestion charges (e.g. Börjesson et al. Citation2015; Eliasson and Jonsson Citation2011). Based on surveys in European cities, researchers find that environmental concern is one of the most influential attitudinal factors (Börjesson et al. Citation2015; Hamilton et al. Citation2014), and one of the two most important factors to congestion charges (Eliasson and Jonsson Citation2011). Hamilton et al. (Citation2014) address that the associations between environmental concerns and support for congestion charges are context-dependent, and point out that if congestion charge were suggested in a city where the public attached importance to economic development without paying much attention to the natural environment; the impact strength of environmental concerns might be significantly reduced.

Most researchers treat respondents’ concerns on specific environmental issues as environmental concerns in general, which is useful in identifying general rules. However, different environmental concerns derive from corresponding problem contexts (Vorkinn and Riese Citation2001). For example, in cities where industry is the primary source of pollution, citizens will pay more attention to industrial pollution and its solutions, and less attention to the impact of other types of pollution such as traffic pollution on the environment. In analyzing public attitudes toward traffic policies, the effect of traffic-related environmental concerns should be identified from general environmental concerns to see whether attitudes are affected differently.

So far, the studies of public attitudes toward congestion charges are mostly in cities in developed countries (e.g. of Australia cities, Zheng et al. Citation2014; of European cities, Börjesson et al. Citation2012; Gaunt, Rye, and Allen Citation2007; Souche, Raux, and Croissant Citation2012), where traffic is the primary source of air pollution. In most cities of emerging economies, however, air pollution is often characterized by coal-burning pollution or composite pollution from coal combustion and traffic (e.g. Altieri and Keen Citation2019; Gupta and Spears Citation2017; Li, Feng, and Li Citation2017). The differences in pollution contexts may cause differences in residents’ environmental concerns and policy attitudes.

The purpose of this study is to understand how the pollution context in significant cities of emerging economies affects the association between environmental concerns and public acceptability of congestion charging while taking other influencing factors of attitudes such as expectations of policy effects as control variables. The concept of environmental concern in this study is “the degree to which people are aware of problems regarding the environment and support efforts to solve them” (Dunlap and Jones Citation2002). We chose Beijing as the case city as a representative of the fast-growing metropolis that suffering from severe congestion and environmental problems.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the content of the questionnaire, data collection, and analysis method. Section 3 presents respondents’ environmental concerns, factor analysis of environmental concerns, explanatory factors of policy attitudes, in particular, the impacts of specific environmental concerns on attitudes. Section 4 concludes and discusses the results.

Data and methods

Questionnaire and survey

As a pretest, 117 respondents were interviewed face-to-face in Changping and Haidian District of Beijing during October 2015. During the pretest, we revised the questionnaire to ensure the understanding and acceptance of respondents. We conducted the formal survey from November 2015 to April 2016. The sample frame was the residents within the 6th ring of Beijing (around 2267 km2). First, we divided the region within the 6th ring into grids of a specific area. Second, we selected several grids at random. Finally, we chose households randomly from the selected grids. The surveys were conducted over the weekends to include target respondents of all ages older than 18. In total, we selected 1992 samples randomly, among which we interviewed 874 respondents, with a response rate of 44%; 14 questionnaires were excluded due to uncompleted information, inconsistent answers, and extreme values, resulting in 860 useable observations.

In addition to an introduction section, other parts of the questionnaire are environmental concerns, travel patterns, policy attitudes, and demographic information of respondents. Based on orthogonal experimental design, four attributes, namely toll area, toll period, charging level, and revenue use, were combined at different levels to form eight policy alternatives (See ).

Table 1. Attributes and levels of the policy alternatives

Each questionnaire details a policy alternative in the “Policy Attitudes” section and describes its potential positive and negative policy impacts. The possible positive effects include: (1) The decrease of vehicle traffic volume, the decrease in traffic congestion time and the increase of vehicle speed; (2) The improvement of air quality. The potential negative impact is that public transit might be more crowded. Respondents are then asked to assess their level of support for the policy and the expected policy impact on personal life, congestion mitigation, and air quality improvement.

Empirical hypotheses

The assumption underlying this study is that the contexts of environmental problems affect the acceptability of congestion charge by influencing the environmental concerns of residents. This assumption can be further developed into two hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1. Compared with residents of other international metropolises characterized by traffic pollution, Beijing residents are less convinced that traffic pollution can severely affect ambient air quality. The characteristics of air pollution in Beijing are mixed source pollution, i.e. industrial pollution (regional and local), coal burning, and traffic pollution. Among them, regional industrial pollution transmission has the highest contribution rate. This pollution context in Beijing might have affected residents’ environmental concerns.

Hypothesis 2. Beijing residents who concerned about industrial pollution may have less support for congestion charging policies. The city’s pollution context may have a differentiated effect on residents’ environmental concerns. Moreover, there may be mutual exclusion between different concerns. Those who think that industry is a more important source of air pollution will think that reducing industrial pollution rather than traffic pollution can improve the environment more significantly. Conversely, those who are more concerned about traffic pollution are more supportive of traffic pollution management policies. Therefore, influenced by the pollution context, industry-related and traffic-related environmental concerns might have different impacts strength on policy acceptability.

The test of these two hypotheses can help us understand the impact mechanism of pollution context on public policy attitudes.

Analytical method

Since the response variable (support for congestion charge) is a multi ordinal variable, the ordinal regression model is used to analyze the explanatory variables of acceptability. The two Logit models are fitted as follows:

Where: π1, π2, π3 – the probabilities of 1 ~ 3 levels of attitude variables (namely “not support, neutral, and support”), respectively; α, β – estimated parameters; envconcern – environmental concern variables; expectations – policy expectation variables, including expected effects on personal life, congestion reduction, and air quality improvement; attributes – attributes of policy alternatives, including toll area, toll period, charging level, and revenue use; socioeconomic – social and economic characteristics of respondents, including gender, age, income, and education.

Results and analysis

Respondents’ demographic characteristics

The socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents under each policy alternatives are given in .

Table 2. Socio-economic characteristics of respondents under each policy alternative

The results of one-way ANOVA in show that the means of the socioeconomic characteristics of the eight subgroups are the same. As seen from , respondents’ average age was close to that of the census data in Beijing. Male respondents, as well as low and middle-income groups, were slightly overrepresented. Respondents’ lower average income may be due to the difficulty in entering high-level communities, so the proportion of high-income groups in the survey is relatively small.

Public perception of the causes of air pollution

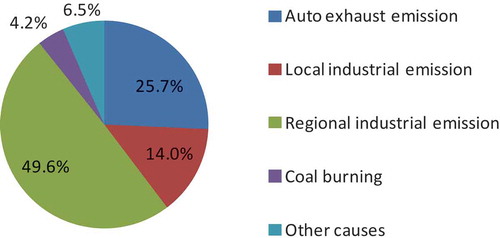

Respondents’ perception of the leading causes of air pollution in Beijing is shown in .

shows that the respondents believe that the leading causes of air pollution in Beijing are “regional industrial emission” (49.6%), “auto emissions” (25.7%), “local industrial emissions” (14.0%). According to the PM2.5 source apportionment result issued by Beijing Environmental Protection Bureau in 2014, local auto emission contributes about 19.9%-22.4% to total pollution in Beijing; and regional industrial emission contributes 28.0%-36.0% in general, while under unfavorable weather conditions, the regional contribution could reach more than 50% (Streets et al. Citation2007). To sum up, the regional transmission has the most significant impact on air quality in Beijing, especially in heavily polluted weather. These show that respondents’ awareness of the leading causes of air pollution in Beijing is consistent with the official information.

Industrial and traffic-related environmental concerns

Public environmental concerns

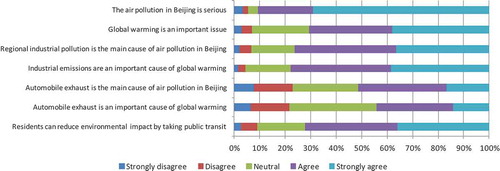

We designed several statements of the relationship between air quality and pollution in the questionnaire. The Likert scale is used to ask respondents to what extent they agree on each statement, i.e. 1 to 5 indicates from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” respectively. Respondents’ environmental beliefs are given in .

Most respondents are concerned about the general environmental problems (), “Global warming is an important issue” (Mean = 4.0, SD = 1.0) and “The air pollution in Beijing is serious” (Mean = 4.5, SD = 0.9). And most respondents are aware of the environmental consequences of industrial activities in the local (Mean = 4.0, SD = 1.0) and global (Mean = 4.1, SD = 0.90). However, less attention is paid to the impact of traffic behavior on the local environment (Mean = 3.4, SD = 1.2) or the global environment (Mean = 3.3, SD = 1.1).

compares the environmental concerns of Beijing residents and urban residents of developed countries.

Table 3. Respondents’ expected effects of congestion charge, general and traffic-related environmental concerns in cities in related studies

As can be seen from , urban residents in Beijing and developed countries have similar levels of general environmental concerns, as well as traffic-related environmental concerns (based on the comparison between the agreed rate of residents in European cities to the statement “motor traffic is among the largest threats to the environment” and Beijing residents’ agreed rates to the comments “automobile exhaust is the main cause of air pollution in Beijing” and “automobile exhaust is an important cause of global warming”). This result rejects hypothesis 1 that compared with residents of other international metropolises characterized by traffic pollution, Beijing residents are less convinced that traffic pollution can seriously affect the ambient air quality.

Intercorrelation among seven environmental concern items and correlations between environmental concerns and demographic variables are analyzed to test whether attitudes toward different environmental problems are consistent. The results are shown in and .

Table 4. Correlations among environmental concerns a.

Table 5. Bivariate correlations between environmental concerns and selected demographic variables a.

As shown in , concerns over “The air pollution in Beijing is serious” are more strongly related to industry-related concerns (r is ranging from 0.168 to 0.234) than traffic-related concerns (r is ranging from 0.082 to 0.141). Environmental concerns over industry-related problems are either slightly correlated (r is ranging from 0.063 to 0.180) or not correlated (r is ranging from −0.008 to 0.042) with concerns over traffic-related problems.

As can be seen from , the coefficients of gender are always in the expected direction (negatively related to environmental concern) and are significant for five of the seven measures, indicating that women are significantly more environmentally concerned than men, which is consistent with the results in studies of environmental concerns (Stern, Dietz, and Kalof Citation1993; Zelezny, Chua, and Aldrich Citation2000). However, education differentially correlates with specific environmental concerns, that is, positively relates to industry-related environmental concerns, and negatively relates to traffic-related environmental concerns. These are also the case in the relationships between income and specific environmental concerns. These may be because, with the improvement of educational and income level, residents can better obtain and better understand the pollution information, such as the regional transmission of industrial pollution. Therefore, Beijing residents with a higher level of education and income are more concerned about the impacts of industrial pollution on air quality.

Results from – show that the specific environmental concerns are context-dependent. The characteristics of mixed source pollution in Beijing caused differentiated concerns of respondents on industrial and traffic pollution. As a result, these two specific environmental concerns are relatively independent of each other and are related to socio-demographic variables in different ways.

Factor analysis of environmental concern items

Factor analysis is applied to reduce the dimensionality of seven environmental concerns items and to explore the relationship between specific environmental concerns. First, the data is checked, and KMO value is 0.659, and Bartlett test value is 951.5 (P <0.001), indicating that the data is suitable for factor analysis. The analysis results in two factors, only factors with eigenvalues greater than one are used, and the accumulative contribution rate is 52.8%. displays the rotated factor loadings.

Table 6. Rotated factor loadings of environmental concern variables

As shown in , the first factor, labeled as industrial pollution factor (INDUS), combines general environmental concerns, and concerns about the environmental impact of regional and global industrial pollution, reflecting the traditional concerns over industrial pollution. The second factor, labeled as transport pollution factor (TRANS), combines the concerns about the environmental impact of exhaust emissions and bus travel, reflecting the concerns over transport pollution. Factor analysis results show that under the influence of the pollution context, Beijing residents’ two specific environmental concerns, industry- and traffic-related environmental concerns, are independent of each other.

Public policy attitude and its influencing factors

Public attitudes toward congestion charges

The seven-graded scale is used to express respondents’ attitudes to congestion charges, from “strongly oppose” (1) over “neutral” (4) to “strongly support” (7). The Kruskal-Wallis chi-square test shows that the respondents did not differ in their attitudes toward different policy alternatives (X2 = 12.959, P >0.05) so that the subgroups of different policy alternatives can be merged and analyzed.

The policy support rate is 33%, and the mean attitude is 3.6 (SD = 2.0), indicating that the overall attitude is not supportive. Worldwide, low public support for congestion charges is quite common. For instance, the general acceptance rate was 43% – 52% in Stockholm before the congestion charges trial (Winslott-Hiselius et al. Citation2009), 33% in Gothenburg before the implementation of the scheme (Börjesson, Eliasson, and Hamilton Citation2016); and the mean score of public acceptability for a toll charge in the Netherlands was 2.9 out of a 7-graded scale (Schuitema, Steg, and Rothengatter Citation2010).

67% of the respondents object to congestion charges (including unsupportive and neutral attitudes). Three main reasons are “congestion charges cannot solve the traffic congestion and air pollution problems” (56%), “Congestion charges limit the travel options of low- and middle- income car owners, but have little impact on the rich” (11%), “I am worried that the use of the policy revenue maybe not transparent and not well regulated” (8%), indicating that the important factors for residents to oppose congestion charges are effectiveness, fairness, and trust in public agencies.

Influencing factors of policy attitudes

Descriptions of the variables that could theoretically affect policy attitudes are shown in . Regression analysis results are shown in .

Table 7. Description of variables

Table 8. Influencing factors of support for the congestion charge (N = 860)

Results () show that TRANS factor and Exh_BJ significantly affect respondents’ policy attitudes, indicating that people with strong traffic-related environmental concerns are more likely to support the congestion charge, while the impacts of general and industry-related environmental concerns are not significant. These support hypothesis 2 that Beijing residents who concerned about industrial pollution may have less support for congestion charging policies. There are similarities and differences between this result and those of other studies in European cities, which report the significant impacts of general environmental concerns (Hamilton et al. Citation2014) and traffic-related environmental concerns (Eliasson and Jonsson Citation2011) on acceptability.

In all the three models (), two of the three policy expectation variables, PersonLf and TraffImprov, significantly affect respondents’ policy attitudes, and the former contributes more to the explanation of acceptability. Respondents who expected to be better off in general and respondents who expected a reduction in congestion when the policy is implemented are more likely to support congestion charges, which is consistent with the results of the related studies (Eliasson and Jonsson Citation2011; Schuitema, Steg, and Rothengatter Citation2010). As the consent degree of respondents to the statement of expected environmental effect changes from “strongly disagree” to “agree,” the partial regression coefficient increases gradually, and the sign changes from negative to positive, indicating that respondents who expected improvement of environment tend to support the policy; but the impact of this variable is not significant.

Conclusions and discussions

We take Beijing as an example to investigate urban residents’ support for a congestion charge in emerging economies and analyze the impacts of pollution context on the association between specific environmental concerns and policy attitudes. We find that the acceptability of congestion charge in Beijing is around 33%, indicating that the overall attitude is not supportive. We have identified two specific environmental concerns; one is traditional that focuses on the impact of industrial pollution on the environment; the other is the concerns of the adverse environmental effects of traffic activities. These two specific environmental concerns are relatively independent of each other and relate in different ways to policy acceptability. The traffic-related environmental concern is strongly related with the positive attitudes to the congestion charge, while the impact of industry-related environmental concerns is not significant. The expected policy effects on the personal life and congestion mitigation are significantly associated with support for the congestion charge, while the expected environmental impact is not significant.

The insignificant impacts of general and industry-related environmental concerns, as well as expected environmental effects on support for congestion charges, are different from the research results of European cities (Börjesson et al. Citation2015; Schuitema, Steg, and Rothengatter Citation2010), and we attribute these differences to the influence of different pollution contexts. Unlike air pollution in European cities, which is mostly characterized by traffic pollutants, regional transmission of industrial pollutants contributes the most to Beijing’s air pollution, which makes Beijing residents pay more attention to industrial pollution. Although congestion charging has certain environmental effects, the localization of the charging measures makes the policy more effective in improving air quality on days when local pollution is dominant. During periods of severe pollution (often in adverse atmospheric diffusion conditions) that are of great public concern and are typically characterized by the transmission of regional pollutants, the contribution of local pollution will diminish, and the perceived environmental effects of congestion charging will decline. In short, objectively and subjectively, Beijing residents do not consider congestion charging to be an effective way to tackle air pollution. Therefore, although Beijing residents have a high degree of environmental concerns, most of these concerns are related to industrial pollution and cannot bring support for congestion charging.

Researchers address that if congestion pricing is reframed from fiscal policy to environmental policy, the impact of environmental concerns on policy attitudes will be strengthened (Börjesson, Eliasson, and Hamilton Citation2016). “Reframing” is a gradual process, as happened in Stockholm during the mid-1990s (Eliasson Citation2014), well before the implementation of the congestion charge. At present, the kind of reframing process has begun in Beijing, some people have been well aware of the environmental consequences of traffic behaviors, whether in the local or global, but the process is far from completion. As an international metropolis, Beijing’s local industrial pollution has been well controlled, and the contribution rate of traffic pollution to local pollution ranks first. However, due to pollution transmission, regional industrial pollution has the most significant impact on air quality and population health in Beijing. These are hindering the reframing process in Beijing. In emerging economies, because of the uneven development among regions and cities, the pollution context in Beijing is also familiar in many other big cities. Under these circumstances, even if the general level of environmental concerns is high and congestion charges are “marketed” as environmental policies, there is no guarantee that policy support will rise.

This paper adds to the limited number of attitude research of congestion charge in cities of emerging economies, and it contributes to the understanding of the influence of pollution contexts on the association between specific environmental concerns and public acceptability of congestion charging. More research in major cities of emerging economies suffering from both traffic congestion and industrial pollution problems is warranted to test the robustness of our results. Moreover, further studies are warranted to address the relationship between specific environmental concerns and attitudes toward traffic policies in different air pollution contexts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China [No. 14BGL208]. The efforts by Mr. Zhen Wang, Ms. Yanbin Chen, Ms. Ying Wang, Mr. Buyun Zheng, Ms. Qianqian Liang, Mr. Xinghua Zhang, Ms. Huihui Long, Mr. Fude Ma, Mr. Yibo Dong on collecting survey data are appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altieri, K. E., and S. L. Keen. 2019. “Public Health Benefits of Reducing Exposure to Ambient Fine Particulate Matter in South Africa.” Science of the Total Environment 684: 610–12. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.355.

- Atkinson, R. W., B. Barratt, B. Armstrong, H. R. Anderson, S. D. Beevers, I. S. Mudway, D. Green, et al. 2009. “The Impact of the Congestion Charging Scheme on Ambient Air Pollution Concentrations in London.” Atmospheric Environment 43: 5493–5500. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.07.023.

- Boardman, A. E., D. H. Greenberg, A. R. Vining, and D. L. Weimer. 2012. Cost-benefit Analysis: Concepts and Practice. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Börjesson, M., J. Eliasson, and C. Hamilton. 2016. “Why Experience Changes Attitudes to Congestion Pricing: The Case of Gothenburg.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 85: 1–16.

- Börjesson, M., J. Eliasson, M. B. Hugosson, and K. Brundell-Freij. 2012. “The Stockholm Congestion Charges – 5 Years On. Effects, Acceptability and Lessons Learnt.” Transport Policy 20: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2011.11.001.

- Börjesson, M., C. J. Hamilton, P. Näsman, and C. Papaix. 2015. “Factors Driving Public Support for Road Congestion Reduction Policies: Congestion Charging, Free Public Transport and More Roads in Stockholm, Helsinki and Lyon.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 78: 452–462.

- Creutzig, F., and D. He. 2009. “Climate Change Mitigation and Co-benefits of Feasible Transport Demand Policies in Beijing.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 14: 120–131. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2008.11.007.

- Dunlap, R. E., and R. E. Jones. 2002. “Environmental Concern: Conceptual and Measurement Issues.” In Handbook of Environmental Sociology, edited by R. E. Dunlap and W. Michelson, 485. London: Greenwood Press.

- Eliasson, J. 2008. “Lessons from the Stockholm Congestion Charging Trial.” Transport Policy 15: 395–404. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2008.12.004.

- Eliasson, J. 2014. “The Role of Attitude Structures, Direct Experience and Reframing for the Success of Congestion Pricing.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 67: 81–95.

- Eliasson, J., and L. Jonsson. 2011. “The Unexpected “Yes”: Explanatory Factors behind the Positive Attitudes to Congestion Charges in Stockholm.” Transport Policy 18: 636–647. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2011.03.006.

- Eliasson, J., and L. Mattsson. 2006. “Equity Effects of Congestion Pricing: Quantitative Methodology and a Case Study for Stockholm.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 40: 602–620.

- Gaunt, M., T. Rye, and S. Allen. 2007. “Public Acceptability of Road User Charging: The Case of Edinburgh and the 2005 Referendum.” Transport Reviews 27 (1): 85–102. doi:10.1080/01441640600831299.

- Goh, M. 2002. “Congestion Management and Electronic Road Pricing in Singapore.” Journal of Transport Geography 10 (1): 29–38. doi:10.1016/S0966-6923(01)00036-9.

- Gupta, A., and D. Spears. 2017. “Health Externalities of India’s Expansion of Coal Plants: Evidence from a National Panel of 40,000 Households.” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 86: 262–276. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2017.04.007.

- Hamilton, C. J., J. Eliasson, K. Brundell-Freij, C. Raux, S. Souche, K. Kiiskilää, and J. Tervonen, 2014. “Determinants of Congestion Pricing Acceptability.” CTS Working Paper No. 2014. 11. SE-100 44 Stockholm, Centre for Transport Studies, KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

- Jaensirisak, S., M. Wardman, and A. D. May. 2005. “Explaining Variations in Public Acceptability of Road Pricing Schemes.” Journal of Transport, Economics and Policy 39 (2): 127–153.

- Kottenhoff, K., and K. B. Freij. 2009. “The Role of Public Transport for Feasibility and Acceptability of Congestion Charging: The Case of Stockholm.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 43: 297–305.

- Li, S., K. Feng, and M. Li. 2017. “Identifying the Main Contributors of Air Pollution in Beijing.” Journal of Cleaner Production 163: S359–S365. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.127.

- Santos, G., H. Behrendt, and A. Teytelboym. 2010. “Part II: Policy Instruments for Sustainable Road Transport.” Research in Transportation Economics 28 (1): 46–91. doi:10.1016/j.retrec.2010.03.002.

- Schaller, B. 2010. “New York City’s Congestion Pricing Experience and Implications for Road Pricing Acceptance in the United States.” Transport Policy 17: 266–273. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.01.013.

- Schuitema, G., and L. Steg. 2008. “The Role of Revenue Use in the Acceptability of Transport Pricing Policies.” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 11: 221–231. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2007.11.003.

- Schuitema, G., L. Steg, and J. A. Rothengatter. 2010. “The Acceptability, Personal Outcome Expectations, and Expected Effects of Transport Pricing Policies.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (4): 587–593.

- Souche, S., C. Raux, and Y. Croissant. 2012. “On the Perceived Justice of Urban Road Pricing: An Empirical Study in Lyon.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 46: 1124–1136.

- Stern, P. C., T. Dietz, and L. Kalof. 1993. “Value Orientations, Gender, and Environmental Concern.” Environment and Behavior 25 (5): 322–348. doi:10.1177/0013916593255002.

- Streets, D. G., J. S. Fu, C. J. Jang, J. Hao, K. He, X. Tang, Y. Zhang, et al. 2007. “Air Quality during the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games.” Atmospheric Environment 41 (3): 480–492. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.08.046.

- Vorkinn, M., and H. Riese. 2001. “Environmental Concern in a Local Context: The Significance of Place Attachment.” Environment and Behavior 33 (2): 249–363. doi:10.1177/00139160121972972.

- Winslott-Hiselius, L., K. Brundell-Freij, Å. Vagland, and C. Byström. 2009. “The Development of Public Attitudes Towards the Stockholm Congestion Trial.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 43: 269–282.

- Yu, W. C. 2015. “Public Appeal, Government Intervention and Environmental Governance Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis Based on Provincial Panel Data.” Journal of Yunnan University of Finance and Economics 5: 132–139. (In Chinese).

- Zelezny, L. C., P. Chua, and C. Aldrich. 2000. “New Ways of Thinking about Environmentalism: Elaborating on Gender Differences in Environmentalism.” Journal of Social Issues 56 (3): 443–457. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00177.

- Zhang, S., and Y. Li. 2016. “Different Government Smog Governance Strategies in Response to Public Opinion.” Comparative Economic & Social Systems 3: 52–60. (In Chinese).

- Zheng, S. Q., G. H. Wan, W. Z. Sun, and D. L. Luo. 2013. “Public Appeal and Urban Environmental Governance.” Management World 6: 72–84. (In Chinese).

- Zheng, Z., Z. Liu, C. Liu, and N. Shiwakoti. 2014. “Understanding Public Response to A Congestion Charge: A Random-effects Ordered Logit Approach.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 70: 117–134.

Residents’ attitudes to traffic congestion charges

Survey Date: / /2016 Survey location: District

Good morning / afternoon. I’m from China University of Petroleum (Beijing). We are conducting a study on residents’ attitudes to traffic congestion charges. In recent years, traffic congestion and air pollution in Beijing have become the most concerned issue for the public. Beijing has adopted a series of traffic management measures, such as driving restriction, passenger car quota, improvement of gasoline quality, improvement of motor vehicle emission standards, increase of parking fees in central urban areas, and construction of subway, but the effect is not satisfactory. With the increasing number of vehicles, traffic congestion and air pollution problems are getting worse.

At present, the Beijing Municipal Transportation Commission and the Municipal Environmental Protection Bureau are jointly formulating a traffic congestion charging scheme. Congestion charges refer to the charging of road users in some areas during traffic congestion to reduce traffic volume and alleviate traffic congestion and air pollution. At present, some cities in the world, such as Singapore, London and Stockholm, have carried out policy practices and achieved good results.

This questionnaire is designed to investigate the attitudes of Beijing residents to the congestion charge policy. Your opinion is valuable to the study. Do you agree to participate in the survey? Thank you, the time duration of this interview is about 20 minutes, we greatly appreciate your completion of the questionnaire. Your answers will be used only for the purpose of research. In answering the questions, please remember that there are no correct or wrong answer. We are just after your honest opinion.

Part I Public Opinion to Environmental Problems

A1. The following are some statements on environmental issues in Beijing. How strongly you agree or disagree with each?

A2. In your opinion, the main cause of traffic congestion in Beijing is ——.

(1) Excessive number and rapid growth of motor vehicles;

(2) Development of public transport lags behind;

(3) The unreasonable urban planning leads to the concentration of traffic flow in the city center;

(4) The unreasonable road planning and design lead to serious congestion in some sections;

(5) The level of traffic order management is low, and some people and cars do not abide by the traffic regulations;

(6) Traffic intelligence and informatization construction lag behind;

(7) Other reasons, please indicate —————.

A3. Which of the following policy can most effectively solve the traffic congestion problem in Beijing?

Odd-even driving restriction;

Congestion charges;

Improvement of bus and subway system;

Passenger car quota;

Increase parking fees in the downtown area;

Raise the level of fuel tax

New and widened roads;

Improve the design of existing roads;

Improve the management level of traffic order and regulate the traffic behavior of people and vehicles;

Improve the level of intelligent traffic management;

None of the above policies can produce significant results. Please write down the effective measures you think are —————.

A4. What do you think is the main cause of air pollution in Beijing?

Motor vehicles exhaust emissions;

Industrial pollution emissions in Beijing;

Industrial pollution emissions in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region;

Coal-fired boiler (heating, electricity) pollution emissions;

Road dust and construction site dust;

Catering fume emissions;

Dust weather;

Other reasons, please indicate .

A5. Which of the following policy can most effectively improve air pollution in Beijing?

Strengthening industrial pollution control in Beijing;

Strengthening the prevention and control of motor vehicle exhaust in Beijing;

Joint prevention and control of industrial pollution in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei area;

Joint prevention and control of vehicle exhaust pollution in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei area;

Strengthening the control of coal-fired pollution;

Strengthening dust management on roads and construction sites;

Strengthening the management of catering soot emissions;

None of the above policies can produce significant results. Please write down the effective measures you think are —————.

Part II Travel Pattern

B1. Do you drive to work?

(1) Never; (2) Rarely; (3) Sometimes; (4) Frequently; (5) Every time.

B2. How well do you know about the public transit near the community? (How many buses, general routes, frequency of departures, subway stations, etc.)

(1) Not familiar at all; (2) not familiar; (3) Neutral; (4) Somewhat familiar; (5) Very familiar.

B3. How satisfied are you with the public transit near the community? (Including the frequency, transfer, punctuality, crowding, etc. of the public transit)

(1) Very unsatisfied; (2) Unsatisfied; (3) Neutral; (4) Satisfied; (5) Very satisfied.

B4. How many cars are there in your family?

(1) One; (2) Two; (3) Three and above; (4) Zero.

B5. What is the main mode of transportation for your commute?

(1) Driving to work; (2) Parking and transfer to the bus; (3) Bus, subway, shuttle;

(4) Taxi; (5) Car pooling; (6) Bicycle; (7) Others.

B6. What is the distance between your workplace and your home? km

Part III Attitudes to traffic congestion charges

C1. To what extent you would support this project?

If the respondent chooses one of the “1–4“ options, then proceed to C2; if the respondent chooses one of the ”5–7” options, proceed to C3 directly.

C2. The main reason why you don’t support this project is ——?

I don’t think congestion charges can solve traffic congestion and air pollution problems;

I am worried that the use of the policy revenue may be not transparent and not well regulated;

Alternative modes of transportation such as bus and subway are inconvenient, uncomfortable and time consuming;

Congestion charges limit the travel options of low- and middle-income car owners, but they have little impact on the rich;

It is unfair for residents who live and work in the fourth ring to drive without having to pay congestion charges;

The increase in travel costs will lower my standard of living;

The government can adopt other policy measures to solve traffic congestion and air pollution problems;

Traffic congestion is mainly caused by irregular traffic behaviors, which should be regulated by the government;

I am the victim of traffic congestion and should not pay for it;

At present, traffic congestion has little impact on my life;

Other reasons, please indicate —————.

C3. Please consider this project from two aspects: favorable impacts (congestion reduction, air quality improvement, etc.) and adverse effects (increased travel costs, etc.). Overall, how do you expect this implementation will affect your life?

C4. How do you agree with the following statement: “Implementation of this congestion charge project will effectively reduce traffic congestion in Beijing”?

C5. How do you agree with the following statement: “Implementation of this congestion charge project will effectively improve the air quality in Beijing”?

Part IV Socio-economic Information

D1. Age: ——.

D2. Gender: (1) Male; (2) Female.

D3. Household Size: ——.

D4. Education:

(1) Elementary school and below; (2) Junior High School; (3) Senior High School;

(4) University; (5) Master’s degree and higher.

D5. Household Income:

(1) < 4000 CNY; (2) 4001–8000 CNY; (3) 8001–12,000 CNY;

(4) 12,001–16,000 CNY; (5) 16,001–20,000 CNY; (6) 20,001–30,000 CNY; (7) >30,000 CNY.

Thank you very much for your kind help.