ABSTRACT

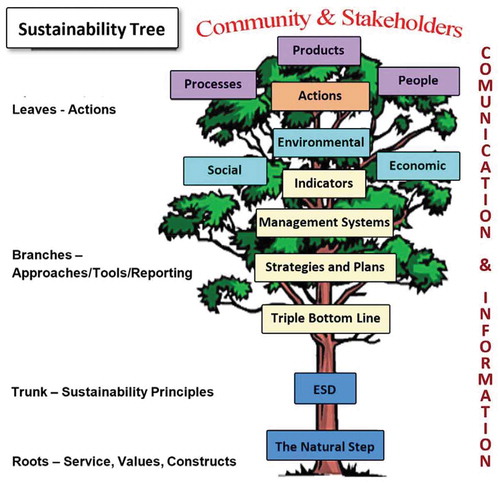

This study aimed to determine the sustainability criteria of the beekeeping industry in Iran, which was performed using three-stage classical Delphi technique. The participants were 32 experts in beekeeping industry who were purposefully selected using the snowball sampling method. The criteria identified, after three Delphi stages, consisted of 70 items, which were categorized into 13 general criteria and into four economic, environmental, social, and institutional dimensions. The general criteria were presented in the form of a conceptual model, including: farmers’ environmental behavior quality, beekeepers' environmental behavior quality, the quality of marketing and sales of beekeeping productions, productivity and performance improvement, amount of monetization from pollinations' right, the amount of monetization of byproducts and value added, employment rate and job stability, the level of social development of stakeholders, the quality of the role-playing of non-governmental stakeholders, the quality of extension and education new sciences and technologies to stakeholders, comprehensiveness of laws and programs, quality of role-playing of stakeholder non-governmental organizations, and the quality of the roleplaying of governmental institutions stakeholder. Using them, a comprehensive perception of the necessary criteria for the sustainability of Iran's beekeeping industry can be obtained and a comprehensive program can be designed for its implementation.

Introduction

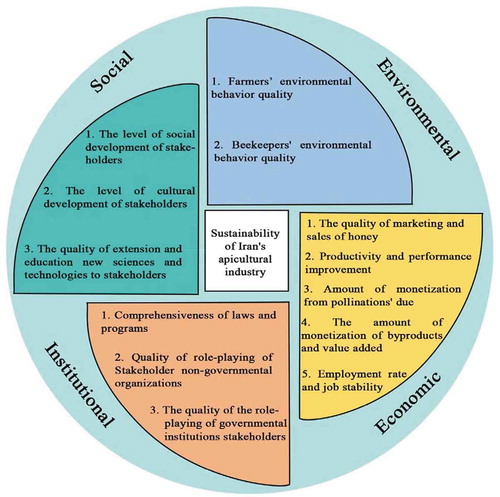

The original idea of sustainability first appeared in an official under the auspices of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 1969 and became the main topic of the UN International Conference on Human Environment in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1972. The mainstream of sustainable development thinking developed and evolved through the World Conservation Strategy (1980), the Brundtland report (in 1987), and the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio, Brazil (in 1992) in the following decades (Adams Citation2006). According to a definition presented in the Brundtland Report entitled “our common future,” sustainable development is the development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (WCED Citation1987; Mohammadi-Mehr et al. Citation2018; Sabzali Parikhani et al. Citation2018). In fact, the interests of the two groups, namely the next generation of humans and other species of living things are considered in the concept of sustainability (Duran Citation2015). In 2002, Crawford presented the schematic of a sustainability tree, resembling it to a tree whose roots include science, values, and constructs (). The trunk of the tree is the principles of sustainable development while its three main branches are social, economic, and environmental dimensions that develop more accurate strategies and plans, management systems, and indicators. Finally, the leaves of this tree are at the highest level, indicating the actions and interests of the beneficiaries of the program (Schutte Citation2009).

Figure 1. Sustainability tree (Crawford, Young, and Mial Citation2002)

One of the most important steps toward sustainable development took place in 2015. On September 25, 2015, the 193 Member States of the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development – including 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets. The agenda commits the international community to end poverty and hunger and achieve sustainable development in all three dimensions (social, economic and environmental) over the next 15 years (2016–2030) (FAO Citation2017). Following the 2030 agenda, in Iran, in 2015, with the presence of ministers and high-ranking representatives of 12 institutions, the main trustees of the 17 SDGs were identified. The National Committee for Sustainable Development in the Department of Environment is responsible for coordinating and cooperating with various stakeholders. (Iranian Department of Environment Citation2015). In this regard, the beekeeping industry as a sustainable food production system plays an important role in achieving the 2030 agenda for SDGs. The concept of sustainability has been largely altered during its evolution process and emerging trends have arisen in this area, including urban sustainable development, sustainable indicators, water management, environmental assessment, and general policies (Olawumi and Chan Citation2018; Moradi et al. Citation2011; Ebrahimi Sarcheshmeh et al. Citation2018). In this context, sustainable agriculture is a type of agriculture that improves the life quality of the current and future generations by preserving and improving the ecological processes on which life depends. In sustainable agriculture, the primary goal is establishing a type of agriculture that is economically viable, socially accountable, and eco-friendly. In addition, this type of agriculture should improve the life quality of farmers and their families on a farm and be ecologically renewable in line with the sustainability of agricultural production in the community. As such, the sustainable agriculture is an intergenerational concept, meaning that the main focus should be on preserving or improving natural resources instead of depletion or contamination (Ataei Citation2019).

While most researchers and international organizations have assessed sustainable development in three environmental, economic and social dimensions (Rao and Rogers Citation2006; Rogers, Jalal, and Boyd Citation2008; Potter et al. Citation2008; Onduru and Du Preez Citation2008; Hayati, Ranjbar, and Karami Citation2010; Tanguay et al. Citation2010; Bond and Morrison-Saunders Citation2011; Singh et al. Citation2012; Chang, Kelly, and Metzger Citation2015; Berglund and Gericke Citation2016), some have added a fourth “institutional” dimension to this area (UNDESA Citation2001; Spangenberg Citation2002; Golusin and Munitlak Ivanovic Citation2009; UNESCO Citation2010; Schindler, Graef, and König Citation2015; Yang et al. Citation2016; Bachev Citation2016). The dimensions of sustainability are interdependent in sustainability literature, meaning that any factor that affects one of the sustainability dimensions influences other dimensions as well. According to researchers, interactions between these dimensions can create a balanced level of sustainable development. Therefore, adopting a new policy in one of the dimensions must be carried out while considering its impact on other dimensions of sustainability. Certainly, the balanced development of sustainability dimensions will pave the way for sustainable development (Gautam Citation2014; Ramcilovic-Suominen and Pülzl Citation2018).

The main question raised in the area of sustainable development is how to measure this concept. While different countries have developed basic indicators for agricultural sustainability at the national and regional levels (OECD Citation2002), no comprehensive measures have been taken in Iran to develop basic indicators for agricultural sustainability so far. This is due to the low awareness of the agricultural sustainability status in the country and a low number of studies performed in this regard. In fact, each sustainability index is a numerical value that consists of several sustainability measures and shows the stability of the agricultural system in the form of a single quantity (Belali and Monteshlo Citation2015). While beekeeping has been one of the most ancient agricultural topics and a common industry in the world and Iran for many years, many of its capacities and capabilities have been neglected so far and no comprehensive study has been conducted to identify the sustainable development indicators in this industry.

The word “Apis” is used for “honey bee” Latin language, and Apiculture is the science and practice of “beekeeping.” Honey harvest has been experienced by humans for at least 4,500 years, and its valuable benefits are fully known. The product that most people remember when they hear the name bee is honey even though honey is just one of several different products that can be harvested from bee colonies. Bee wax, pollen, propolis, royal jelly and venom and using bees in apitherapy are other products of honey bees. In addition to their diverse products, one of the most valuable services of this insect is biodiversity maintenance and pollination (Bradbear Citation2009). The abundance of bees and their close connection with flowering plants make their role in pollination the keystone in the dynamism of the world’s wild and agricultural ecosystems. Scientific assessments show that 45% of agricultural products in the world which are directly consumed by humans, are pollinator-dependent between 1% and 40%, 28% of them are 40–90% pollinator-dependent, and 12% are 90% pollinator-dependent (IPBES Citation2016). The prediction shows that raising overall food production by some 70% will be required in 2050. Although governments and large corporations have made great efforts to provide the food required in the world, 70% of the world’s food is provided by small-scale farmers (Economist Intelligence Unit Citation2018). Naturally, the sustainability of apiculture in the world, especially in developing countries such as Iran (where most farmers are small scale), can significantly affect agriculture and the environment. This sustainable increase could be significant for two billion people around the world working on small-scale farms. For instance, Garibaldi et al. evaluated the impact of the density of pollinators on the performance of 33 pollinator-dependent products in various parts of the world. According to the results, the performance gap could be reduced by increasing the density of pollinators in farms smaller than two hectares, thereby increasing performance by 24% (Garibaldi, Carvalheiro, and Zhang Citation2016). According to the latest statistics presented by the Ministry of Agriculture, there are over than 10 million bee colonies and 98,000 beekeepers in Iran, bred in 85,336 apiaries, which yield 12,000 tons of honey and 2596 tons of other honeybee products annually (Ebadzadeh et al. Citation2019). In this context, studies in Iran have shown that the honey bee is 90 times more valuable in the increase of crop and livestock products, compared to the direct production of hives (Tahmasbi and Poorgharaei Citation2000).

Given the extensive programs designed and implemented in most advanced countries of the world to develop the beekeeping industry, it is crucial to develop a comprehensive plan in Iran for the sustainable development of the industry and using its capacity to extend the agricultural sector of the country. In this regard, various studies have been conducted to measure the level of sustainability in various agricultural areas (OECD Citation1999; Valentin and Spangenberg Citation2000; Evans Citation2005; Lopez-ridaura Citation2005; Mogni et al. Citation2009; Hayati, Ranjbar, and Karami Citation2010; Diazabakana et al. Citation2014; Blewitt Citation2015; Santos Citation2017; Fallah-Alipour et al. Citation2018; Ataei et al. Citation2019). While these studies have proposed criteria and indexes for sustainability measurement, no comprehensive research has been conducted in the area of the apicultural industry to determine sustainability measurement criteria. On the other hand, the proposed criteria have failed to comprehensively measure sustainability in the apicultural industry due to the different nature of this industry, compared to the other agricultural sectors. In a research, Mogni et al. assessed the sustainability development indexes in the apicultural industry of Argentina and realized that the normal indexes used to measure agricultural sustainability could not be used to determine sustainability in the apicultural industry or there were huge differences in this regard (Mogni et al. Citation2009).

Therefore, this study was conducted to fill the scientific gap in this field and lay the foundation for future studies in the area of apicultural industry sustainability and planning for the development of the industry, especially in Iran. The main goal of the present study was recognizing and developing criteria to measure apicultural industry sustainability based on the opinions of experts in the field. The novelty of the current research was using the opinions of experts in the apiculture field of Iran to assess the apicultural industry criteria qualitatively for the first time. Using the opinion of the experts in determining the criteria for assessing the sustainability, in addition to localizing international information, leads to the application and specialization of the identified criteria. Moreover, we evaluated the institutional dimension in this area in addition to three social, economic, and environmental dimensions.

Materials and methods

This is a qualitative research in terms of paradigm and an applied study regarding the goal. In addition, it was a descriptive study in terms of type of research and was implemented using the classic three-step Delphi technique. The Delphi technique was used due to a lack of an adequate research background regarding the sustainability in apiculture industry (Sadeghi and Bijani Citation2018). Delphi technique is a qualitative research method that uses the judgment of qualified experts to provide a valid group opinion. The classic Delphi is a type of Delphi that has five characteristics of anonymity, iteration, controlled feedback, statistical group response, and stability in response among those who specialize in a particular subject (Goodarzi, Abbasi, and Farhadian Citation2018). In the present study, 32 Iranian apicultural experts were selected as a sample by purposeful and snowball sampling. According to Warner and based on the research by Delbecq et al. and Dalkey, an ideal panel size in the Delphi technique is a minimum of 10–15 individuals, and the reliability coefficient of Delphi studies whose expert group number is higher than 13 individuals is 90% (Warner Citation2014). As mentioned, 32 subject experts were enrolled in the research due to fear that some of them might fail to repetitively respond to research questions (28 individuals responded in the third stage). It is notable that the face validity of the questionnaires was confirmed by some academic professors and experts of agricultural and apicultural education and extension.

First, a questionnaire encompassing four open questions entitled “what are the sustainability criteria for Iran’s apicultural industry in four environmental, economic, social, and institutional dimensions?” was provided to the experts. Participating experts in this study presented their perspectives separately on the four dimensions of sustainability. In the second step, the criteria were returned to the participants, asking them to score the items extracted from the first step based on a five-point Likert scale (one and five scores for minimum and maximum agreement, respectively). The items that averaged less than 3.5 (between 1 and 5) were eliminated at this stage, and the remaining criteria eventually entered the third step. In the third step, the above criteria were again referred to the selected experts to announce the extent of their agreement or disagreement with each of the criteria. At this stage, 28 experts responded to the items and the criteria achieving more than 80% of experts’ agreement were selected as the final items for evaluation of sustainability in the apicultural industry of Iran. Finally, the identified criteria were categorized based on the conceptual affinity of the items.

Results

Descriptive and demographic statistics of the panel of experts

In this research, 81% of the experts were male and the rest were female (19%). In addition, 37% of the participants were working in governmental organizations while 31% of individuals were the staff of non-governmental organizations related to the apicultural industry. Moreover, 16% of the experts were academic professors, whereas 16% of the participants had no executive responsibility. Notably, 75% of the participants had beekeeping-related occupations and the rest had a history of activities related to this industry ().

Table 1. Descriptive and demographic statistics of the panel of experts (n = 32)

Environmental sustainability of apicultural industry

Environmental sustainability has been evaluated in various studies as the first and most cited dimensions of sustainability. Researchers have introduced various criteria to assess this dimension, including water and energy use, waste production, CO2 and wastewater, soil degradation and biodiversity, toxicity and chemical fertilizers, organic and green manure consumption, efficiency of use of inputs and performance, and integrated pests management (Evans et al. Citation2005; Mogni et al. Citation2009; Diazabakana et al. Citation2014; Santos, Povoas de Lima, and Alberto Pellegrin Citation2017; Ataei et al. Citation2019). However, as mentioned before, the sustainability criteria in the apicultural industry are different from other agricultural sectors.

Mogni et al. found a huge difference between the apicultural industry and other agricultural sectors in terms of environmental sustainability. In terms of water and energy use, contrary to other agricultural sectors that mostly need water and energy for production, the apicultural industry has almost no need for them except for a small amount used during harvest and cleaning the honey extraction containers. In terms of food waste criteria, despite the high waste production level in various agricultural sectors, the only waste generated in the beekeeping industry is packaging containers, which can also be reused in industries. Regarding the criteria of the amount of CO2 generated in the production process, while methane gas is emitted from animal waste in the livestock sector (which is 23 times more potent than carbon dioxide in trapping heat in the atmosphere), methane generation is very low in apiculture. Moreover, this industry plays a significant, indirect role in the consolidation of CO2 and the reduction of greenhouse gases through the pollination of various plants and the increase of vegetation cover. In terms of wastewater, the water consumption level is very low in this industry. Regarding biodiversity, the industry has greatly contributed to the extension of biodiversity through pollination. In addition, not only the apicultural industry has had no negative effects on soil, but also it plays a crucial role in the improvement of soil quality (Mogni et al. Citation2009).

Given the fact that most conventional criteria used to assess environmental sustainability do not apply to the apicultural industry, we asked the panel of experts to identify sustainability assessment criteria for the environmental dimension in the apicultural industry of Iran while taking the mentioned criteria and the apicultural industry status of Iran into account. According to , 11 items were presented by experts, divided into two classifications of “farmers’ environmental behavior quality” and “beekeepers’ environmental behavior quality” based on the conceptual affinity of the criteria. The items of “the rate of notifications about farm and garden spraying time to beekeepers to reduce honey bees mortality by farmers” and “rate of reduction of pesticides and chemical diseases in apiaries” were ranked second and third with the highest frequency (12 and 11) in the first round.

Table 2. Presented items for assessing the environmental sustainability of apicultural industry

Economic sustainability of apicultural industry

Given its direct impact on the livelihood of the current and future generations, economic sustainability has attracted more attention, compared to the other sustainability dimensions. In this regard, the main goal is long-term economic growth along with ensuring the economic growth of the current generation. In this respect, various criteria were proposed by the panel of experts, including average production, the number of costs spent, the rate of productivity, the amount of income from in-farm production, the amount of income generated from outside the farm, the amount of employment created, the amount of access to sale market and the variety of products produced (OECD Citation1999; Valentin and Spangenberg Citation2000; Mogni et al. Citation2009; Hayati, Ranjbar, and Karami Citation2010; Diazabakana et al. Citation2014; Blewitt Citation2015; Fallah-Alipour et al. Citation2018).

The economic sustainability criteria cited in sources are more common, compared to the criteria of other sustainability dimensions, and could be cited to assess economic sustainability in Iran’s apicultural industry after localization and generalization. Therefore, the panel of experts was requested to determine the criteria that fit the assessment of the economic sustainability of Iran’s apicultural industry based on these criteria. In this regard, 24 criteria were identified, which were divided into five categories of “the quality of marketing and sales of honey,” “productivity and performance improvement,” “the amount of monetization from pollinations’ right,” “the amount of monetization of byproducts and value-added” and “employment rate and job stability” (). According to the classifications, it seems that in addition to selling honey as the main product, revenue can be generated by selling the byproducts of honey such as royal jelly, bee pollen, wax, propolis and venom. Moreover, receiving pollination fee from gardeners, farmers, and rangers can also be profitable.

Table 3. Presented items for assessing the economic sustainability of apicultural industry

Social sustainability of apicultural industry

In addition to the environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability, another dimension assessed was social sustainability. In this area, the main topics assessed are people’s quality of life, local societies, and the extent of their abilities. Social sustainability occurs when formal and informal processes, systems, structures, and relationships actively support the capacity of future generations to build healthy and vibrant communities. A sustainable community is fair, diverse, connected, and democratic and offers a good quality of life. In fact, social sustainability involves achieving a fair degree of social uniformity, fair distribution of income, an occupation that provides suitable welfare, fair access to social services and resources, a balance between respect for tradition and innovation, autonomy, endogeneity, self-construction and self-confidence (Missimer Citation2013).

The following criteria have been proposed for assessment of social sustainability: the level of literacy and education received, the amount of social capital, the health status of family members, the quality of life and livelihood, as well as the level of access to citizenship rights (Lopez-ridaura et al. Citation2005; Diazabakana et al. Citation2014; Blewitt Citation2015; Fallah-Alipour et al. Citation2018; Ataei et al. Citation2019). Based on the mentioned criteria introduced by references to evaluate agricultural sustainability, the experts of the apicultural industry of Iran identified 18 criteria to assess the social sustainability of the industry divided into three classifications of “the level of social development of stakeholders,” “the level of cultural development of stakeholders” and “the quality of extension and education new sciences and technologies to stakeholders” (). According to the results, the criteria of social justice in access to information and facilities, the level of participation of beekeepers in elections and decision-making related to the apicultural industry, the quality of farmers’ and officials’ views on the role of bees in the quantitative and qualitative development of agricultural products, and the number of educational courses held for farmers and rangeland owners to extend the use of honey bees in pollination in farms and gardens in various categories were ranked one to third.

Table 4. Presented items for assessing the social sustainability of apicultural industry

Institutional sustainability of apicultural industry

Institutional sustainability refers to sustainable facilities and services and principled organization of structures, regulated communication between them, and the adoption of appropriate laws, policies, and guidelines (Azad, Rahmani Firuozjah, and Abbasi Asfajir Citation2019). The social dimension is a series of human abilities, whereas the institutional dimension includes human interaction with the guiding laws (i.e. the institutions of that society) (Valentin and Spangenberg Citation2000). The governmental and non-governmental institutions are the influential stakeholders of institutional sustainability while the governing laws and regulations are an effective pillar in this regard. Several non-governmental institutions are active in the apicultural industry, creating a huge potential in this area. On the other hand, the extensive role of this industry in various agricultural sectors necessitates the need for efficient and comprehensive laws to eliminate barriers and increase development.

The criteria proposed in literature review to evaluate institutional sustainability are often in the areas of related laws and regulations, inter-institutional relations, non-governmental institutions, and governmental support. In the present research, the panel of experts suggested 15 criteria for institutional evaluation divided into three main categories of “comprehensiveness of rules and programs,” “the quality of the role-playing of non-governmental stakeholders,” and “the quality of the role-playing of governmental institutions stakeholders” (). As observed, the highest frequency and means were related to the criteria of the comprehensiveness and quality of the executive guarantee of the laws related to the apicultural industry, the extent of the influence and position of apicultural organizations in policy-making and decision-making related to the apicultural industry, and the rate of the benefit of the country’s apicultural community from social insurance services in various categories.

Table 5. Presented items for assessing the institutional sustainability of apicultural industry

Presenting the conceptual model of apicultural industry sustainability

While the assessment criteria of Iran’s apicultural industry sustainability identified by the experts of the research were similar to the criteria introduced in the previous studies in some aspects, there was a huge difference between them. In this regard, shows the classification of the criteria identified in the current research in four environmental, economic, social, and institutional sustainability in the form of a conceptual model.

As observed, the criteria of the environmental dimension were divided into two groups of farmers’ environmental behavior and beekeepers’ environmental behavior. In addition to operating as an independent food production area, the apicultural industry plays a role in farms and gardens due to pollination and the environmental performance of farmers affects the sustainability of the apicultural industry. Therefore, the behavior of farmers has been emphasized in line with the behavior of beekeepers in the study of the environmental sustainability of this industry. In the economic dimensions, the criteria of productivity and performance and employment rate were formerly introduced in other references. Nonetheless, the issue of monetization of byproducts and income generation from pollination were identified by the participants as unique criteria of the industry. Furthermore, given the importance of lab use in determining the quality of products of the industry and the interest of activists in the industry in obtaining a standard certificate for all products, the quality of sales and marketing was recognized as the criteria for economic sustainability in the industry.

The social dimension of sustainability in the apicultural industry is also significantly important considering the expansion of the relations between the industry’s activities in social and cultural development criteria. Due to the establishment of several non-governmental institutions in the apicultural industry and expanded relations with various governmental and non-governmental organizations and institutions and with regard to the need for comprehensive laws and instructions to determine these relations, the apicultural industry needs criteria such as the comprehensiveness of laws and plans and the quality of role-playing of beneficiary governmental and non-governmental institutions. The criteria of social and institutional dimensions in determining the organizational power and social influence of this industry among farmers and various institutions of the society were confirmed by the experts in Iran’s apicultural industry.

Discussion and conclusion

In order to achieve sustainable development goals in each category, the development of evaluation indicators is the first priority, and these indicators must be continuously improved according to the specific conditions of each subject and each region. Also, each country must create the required number and range of indicators according to its needs and capacities (Sarvajayakesavalu Citation2015). Literature review showed that there has been no comprehensive study and suitable tool for evaluating the sustainability of apicultural industry (Bianca, Mǎrghitaş, and Popa Citation2012; Kouchner et al. Citation2018). The present study aimed to determine the sustainability criteria for the apicultural industry in Iran. The review of the literature revealed that the criteria identified in this field do not respond to most areas of the apicultural industry. Accordingly, the research involved an exploratory process and used the Delphi technique and the opinions of experts in the apicultural industry of Iran to identify and conceptualize the sustainability criteria of the industry as a subsidiary of agriculture. However, during the study, the criteria introduced in the theoretical literature were not overlooked and attempts were made to have more reflection in areas with a gap. In this respect, a gap was lack of considering the institutional dimension along with other sustainability dimensions (environmental, economic, and social) in the theoretical literature. After performing the three-stage Delphi method, the criteria identified in the present study included 70 items classified into 13 main criteria based on the conceptual affinity and four sustainability dimensions and presented as a conceptual model. Another issue that distinguished the present research from previous studies was presenting unique criteria and items for the apiculture industry, especially in the environmental dimension, which did not exist in the previous studies. In this regard, Lu et al. (Citation2015) believe that in order to evaluate the sustainability of any ecosystem, it is necessary to integrate the environmental dimension with social, economic, policymaking, biophysical, and biochemical dimensions and use the results in development of practical strategies to achieve and maintain the ecosystem health. The observed differences in the criteria identified in this study, in addition to taking into account the needs and capacities of the studied area, are related to the nature of the apicultural industry. As Mogni et al. (Citation2009) confirm, sustainability in the apicultural industry is very different from other sectors of agriculture. Therefore, the criteria for assessing the sustainability of this industry should be designed and developed according to the specific conditions of that industry. Especially in the environmental dimension, due to the many positive effects of the apicultural industry on the environment, the environmental sustainability criteria of this industry should be very different from other agricultural sectors. Comparison of the results of this study with the goals of 2030 agenda for sustainable development indicates that most of the goals of 2030 agenda are hidden in the criteria identified in the present study. For example, goals 1 and 2 (no poverty and zero hunger) as well as goal 8 (decent work and economic growth) are explained by the five criteria of the economic dimension. Goals 3 (good health and well-being), 6 (clean water and sanitation), 12 (responsible consumption), 13 (climate action), 14 (life below water) and 15 (life on land) of the 2030 goals can be evaluated by the criteria of environmental behavior of beekeepers and farmers. Goals 4 and 10, which refer to quality education and reduced inequalities, are covered by the social dimension criteria. Finally, goals 9 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure), 11 (sustainable cities and communities), 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions) and 17 (partnership for the goals) can also be evaluated using institutional dimension criteria. As explained, with the exception of goals 5 and 7, which refer to gender equality and affordable and clean energy, the rest of goals of 2030 agenda for sustainable development can be assessed in some way by the criteria identified in this study.

Overall, it could be concluded that the conceptual model presented in the current research could provide useful practical and theoretical insights in the area of behavioral changing methods and managerial, technical, social, economic, and environmental interventions to practitioners, decision-makers, policymakers, researchers, and others involved in apiculture management. In other words, the model presented in the current study could be beneficial for the above-mentioned end-users from various aspects.

First of all, they can draw the attention of these individuals toward the importance and key role of the sustainability items and criteria identified in the analysis of the sustainability of the apiculture industry. Meanwhile, these criteria seemed to be forgotten in most previous studies conducted on sustainability. Second of all, the conceptual model presented in the current research could help clarify and increase the comprehensiveness of apiculture sustainability components that could be found among various environmental, economic, social, and institutional variables. In other words, the configuration of apicultural industry sustainability items and their combination in the form of general criteria in the present study led to the creation of a simple model that provides a clear understanding for users and facilitates the stages of intervention with a sustainability approach in the field.

There are some limitations in the current research, similar to other studies in the field. Some of the major drawbacks of the present study were its qualitative approach and lack of confidence in the generalization of the results. Despite this weakness, our research could be used as the basis for future studies, especially those with a quantitative approach. It is recommended that quantitative or mixed approaches be used by researchers to develop the model and use it to compare various regions and groups of beekeepers. Moreover, by reflecting on each of the four dimensions of sustainability, it is possible to design and implement transcendental research from different scientific angles, and present strategies and then operational plans by carefully examining the details of each dimension. Another limitation of the Delphi method, which is natural and unavoidable, is close overlapping of some items, which was attempted to be minimized with great care and benefit from the agreement of the participants in the three-stage Delphi method.

Acknowledgments

A major part of the costs spent for this research was funded by Tarbiat Modares University (TMU). Accordingly, the authors specially thank the research practitioners of this university. A special appreciation should also be expressed to participants as well as the interviewer group members. Evidently, without their help, conductance of this research was not possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adams, W. M. 2006. “The Future of Sustainability: Re-thinking Environment and Development in the Twenty-first Century.” Conference: IUCN Renowned Thinkers Meeting, UK, 29-31 January 2006. https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/12635

- Ataei, P. 2019. “Analysis of Sustainable Learning Transfer Behavior among Protected Agricultural Wheat Farmers of Iran.” PhD Dissertation, Tarbiat Modarres University, College of Agriculture, Department of Agricultural Extension and Education. Unpublished. (In Persian).

- Azad, M., A. Rahmani Firuozjah, and A. Abbasi Asfajir. 2019. “Investigating the Relationship between Social Capital and Urban Sustainable Development, Case Study: Mazandaran Province.” Urban Sociological Studies 9 (30): 89–13. (In Persian). doi:10.22059/JRD.2019.74462.

- Bachev, H., B. Lvanov, D. Toteva, and E. Sokolova. 2016. “Agrarian Sustainability and Its Governance - Understanding, Evaluation, Improvement.” Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 7, 4 (16): 639–663. doi:10.14505/jemt.v7.4(16).11.

- Belali, H., and M. Monteshlo. 2015. “Investigating the Status of Agricultural Sustainability Indicators Due to Fuel Subsidies Reduction, a Case Study of Qorveh Plain.” Journal of Agricultural Economics and Development 29 (2): 150–158. (In Persian).

- Berglund, T., and N. Gericke. 2016. “Separated and Integrated Perspectives on Environmental, Economic, and Social Dimensions – An Investigation of Student Views on Sustainable Development.” Environmental Education Research 22 (8): 1115–1138. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1063589.

- Bianca, P. C., L. A. Mǎrghitaş, and A. A. Popa. 2012. “Evaluation of Sustainability of the Beekeeping Sector in the North West Region of Romania.” Journal of Food Agriculture and Environment 10 (3): 1132–1138. doi:10.1234/4.2012.3610.

- Blewitt, J. 2015. Understanding Sustainable Development. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Bond, A. J., and A. Morrison-Saunders. 2011. “Re-evaluating Sustainability Assessment: Aligning the Vision and the Practice.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 31 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2010.01.007.

- Bradbear, N. 2009. “Bees and Their Role in Forest Livelihoods: A Guide to the Services Provided by Bees and the Sustainable Harvesting, Processing and Marketing of Their Products.” Italy. Rome: FAO. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i0842e.pdf

- Chang, H. C., R. M. Kelly, and E. P. Metzger. 2015. “A Qualitative Study of Teachers’ Understanding of Sustainability: Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), Dimensions of Sustainability, Environmental Protection.” In Improving K-12 STEM Education Outcomes through Technological Integration. China: IGI Global publisher of Timely Knowledge. doi:10.4018/978-1-4666-9616-7.ch010.

- Crawford, J., C. Young, and S. Mial. 2002. “The Sustainability Tree.” Regional Institude Online Publishing. http://www.regional.org.au/au/soc/2002/5/crawford.htm

- Diazabakana, A., L. Latruffe, C. Bockstaller, Y. Desjeux, J. Finn, E. Kell, M. Ryan, and S. Uthes. 2014. “A Review of Farm Level Indicators of Sustainability with A Focus on CAP and FADN.” FLINT Project, funded by the European Commission’s 7th Framework Programme, Contract no. 613800. http://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=LV2016019766

- Duran, D. C., L. M. Gogan, A. Artene, and V. Duran. 2015. “The Components of Sustainable Development - a Possible Approach.” Procedia Economics and Finance 26 (2015): 806–811. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00849-7.

- Ebadzadeh, H. R., K. Ahmadi Somehe, H. Barazandeh, F. Hatami, S. Mohammadnia Afrozi, F. Asghari, and H. Abdeshah. 2019. Detailed Results of the Census of the Iran’s Apiaries in 2018. Information and Communication Technology Center, Deputy Minister of Planning and Economy, Ministry of Agriculture Jihad, Tehran, Iran. (In Persian).

- Ebrahimi Sarcheshmeh, E., Bijani, M., & Sadighi, H. (2018). Adoption behavior towards the use of nuclear technology in agriculture: A causal analysis. Technology in Society, 54(2018), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.08.001

- Economist Intelligence Unit. 2018. Fixing Food 2018: Best Practices Towards the Sustainable Development Goals (Sdgs). Parma, Italy: BCFN Publications.

- Evans, B., M. Joas, S. Sundback, and K. Theobald. 2005. Governing Sustainable Cities. Earthscan. London Sterling, VA: Earthscan.

- Fallah-Alipour, S., H. Mehrabi Boshrabadi, M. R. Zare Mehrjerdi, and D. Hayati. 2018. “A Framework for Empirical Assessment of Agricultural Sustainability: The Case of Iran.” Sustainability 10 (12): 4823. doi:10.3390/su10124823.

- FAO. 2017. “FAO and the SDGs Indicators: Measuring up to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” http://www.fao.org/policy-support/tools-and-publications/resources-details/en/c/854006/

- Garibaldi, L. A., L. G. Carvalheiro, and H. Zhang. 2016. “Supplementary Materials for Mutually Beneficial Pollinator Diversity and Crop Yield Outcomes in Small and Large Farms.” Science 351 (6271): 388–391. doi:10.1126/science.aac7287.

- Gautam, N. 2014. “Analyzing the Sustainable Development Indicators of Nepal Using System Dynamics Approach.” Unpublished, A thesis submitted to the committee of the Graduate School of International and Area Studies Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of M.A. International Development Studies. https://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/handle/10535/9823

- Golusin, M., and O. Munitlak Ivanovic. 2009. “Definition, Characteristics and State of the Indicators of Sustainable Development in Countries of Southeastern Europe.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 130 (1–2): 67–74. doi:10.26458/jedep.v1i2.10.

- Goodarzi, Z., E. Abbasi, and H. Farhadian. 2018. “Achieving Consensus Deal with Methodological Issues in the Delphi Technique.” International Journal of Agricultural Management and Development (IJAMAD) 8 (2): 219–230.

- Hayati, D., Z. Ranjbar, and E. Karami. 2010. “Measuring Agricultural Sustainability.” In Biodiversity, Biofuels, Agroforestry and Conservation Agriculture. Sustainable Agriculture Reviews, E. Lichtfouse edited by, Vol. 5, 73–100. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9513-8_2.

- IPBES. 2016. “The Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services on Pollinators, Pollination and Food Production.” In Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, edited by S. G. Potts, V. L. Imperatriz-Fonseca, and H. T. Ngo, 552. Bonn: Germany.

- Iranian Department of Environment. 2015. Sustainable Development Goals. Tehran, Iran: Hak Publishing.

- Kouchner, C., C. Ferrus, S. Blanchard, A. Decourtye, B. Basso, Y. Conte, and M. Tchamitchian 2018. “Sustainability of Beekeeping Farms: Development of an Assessment Framework through Participatory Research.” IFSA 2018: Farming systems facing uncertainties and enhancing opportunities, Chania, Crete, Greece. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334193227

- Lopez-ridaura, S., H. Van Keulen, M. K. van Ittersum, and P. A. Leffelaar. 2005. “Multiscale Methodological Framework to Derive Criteria and Indicators for Sustainability Evaluation of Peasant Natural Resource Management Systems.” Environment, Development and Sustainability 7: 51–69. doi:10.1007/s10668-003-6976-x.

- Lu, Y., R. Wang, Y. Zhang, H. Su, P. Wang, A. Jenkins, R. C. Ferrier, M. Bailey, and G. Squire. 2015. “Ecosystem Health Towards Sustainability.” Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 1 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1890/EHS14-0013.1.

- Missimer, M. 2013. “The Social Dimension of Strategic Sustainable Development. Blekinge Institute of Technology.” Licentiate Dissertation in Mechanical Engineering, Series No. 2013: 03, School of Engineering, Karlskrona, Sweden. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:834567/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Mogni, F., S. Senesi, I. Palau, and F. Vilella 2009. “The Argentine Beekeeping Sector: Description within the Sustainable Development Framework.” International Food and Agribusiness Management Association 20th Annual World Forum and Symposium, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

- Mohammadi-Mehr, S., Bijani, M., & Abbasi, E. (2018). Factors affecting the aesthetic behavior of villagers towards the natural environment: The case of Kermanshah province, Iran. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology,20(7), 1353–1367.

- Moradi, H., Bijani, M., Shabanali Fami, H., Fallah Haghighi, N., Tamadon, A. R. & Moradi, A. R. (2011). Analysis of effective components on professional development of agricultural extension agents in Kermanshah province in Iran. International Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment, 3&4(9), 803–810. https://doi.org/10.1234/4.2011

- OECD. 1999. “Environmental Indicators for Agriculture, Volume 2, Issues and Design “The York Workshop”.” OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development) Publications Service, Paris, France.

- OECD. 2002. “Governance for Sustainable Development: Five OECD Case Studies.” OECD (Organisation For Economic Co-Operation and Development) Publications Service, Paris, France.

- Olawumi, T. O., and D. W. M. Chan. 2018. “A Scientometric Review of Global Research on Sustainability and Sustainable Development.” Journal of Cleaner Production 183 (May 2018): 231–250. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.162.

- Onduru, D. D., and C. C. C. Du Preez. 2008. “Farmers’ Knowledge and Perceptions in Assessing Tropical Dryland Agricultural Sustainability: Experiences from Mbeere District, Eastern Kenya.” International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology 15 (2): 145–152. doi:10.1080/13504500809469779.

- Potter, R. B., J. A. Binns, J. A. Elliott, and D. Smith. 2008. Geographies of Development. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

- Ramcilovic-Suominen, S., and H. Pülzl. 2018. “Sustainable Development - A ‘Selling Point’ of the Emerging EU Bioeconomy Policy Framework?” Journal of Cleaner Production 172 (January 2018): 4170–4180. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.157.

- Rao, N. H., and P. P. Rogers. 2006. “Assessment of Agricultural Sustainability.” Current Science 91 (4): 439–448. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24093944

- Rogers, P. R., K. F. Jalal, and J. A. Boyd. 2008. “An Introduction to Sustainable Development.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 4 (1): 50–51. doi:10.1080/15487733.2008.11908015.

- Sabzali Parikhani, R., Sadighi, H., & Bijani, M. (2018). Ecological consequences of nanotechnology in agriculture: Researchers’ perspective. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology,20(2), 205–219.

- Sadeghi, A., and M. Bijani. 2018. “Pathological Analysis of Misapplication of Statistical and Data Processing Methods in Agricultural Scientific Research.” Jurnal of Agricultural Education Administration Research 10 (14): 127–148. (In Persian).

- Santos, S. A., H. Povoas de Lima, and L. Alberto Pellegrin. 2017. “A Fuzzy Logic_based Tool to Assess Beef Cattle Ranching Sustainability in Complex Environmental Systems.” Journal of Environmental Management 198 (Part 2, August 2017): 95–106. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.04.076.

- Sarvajayakesavalu, S. 2015. “Addressing Challenges of Developing Countries in Implementing Five Priorities for Sustainable Development Goals.” Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 1 (7): 1–4. doi:10.1890/EHS15-0028.1.

- Schindler, J., F. Graef, and H. J. König. 2015. “Methods to Assess Farming Sustainability in Developing Countries. A Review.” Agronomy for Sustainable Development 35 (3): 1043–1057. doi:10.1007/s13593-015-0305-2.

- Schutte, I. C. 2009. “A Strategic Management Plan for the Sustainable Development of Geotourism in South Africa.” Unpublished, Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Potchefstroom campus of the North-West University. https://repository.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/2252

- Singh, R. K., H. R. Murty, S. K. Gupta, and A. K. Dikshit. 2012. “An Overview of Sustainability Assessment Methodologies.” Ecological Indicators 15 (1): 281–299. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2008.05.011.

- Spangenberg, J. H. 2002. “Institutional Sustainability Indicators: An Analysis of the Institutions in Agenda 21 and a Draft Set of Indicators for Monitoring Their Effectivity.” Sustainable Development 10 (2): 103–115. doi:10.1002/sd.184.

- Tahmasbi, G., and H. Poorgharaei. 2000. “The Value of Honey Bees in Increasing the Iranian Agricultural Products.” The Journal of Agricultural Economics and Development (Agricultural Science and Technology) 8 (30): 131–144. (In Persian).

- Tanguay, G. A., J. Rajaonson, J. F. Lefebvre, and P. Lanoie. 2010. “Measuring the Sustainability of Cities: An Analysis of the Use of Local Indicators.” Ecological Indicators 10 (2): 407–418. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2009.07.013.

- UNDESA. 2001. “Indicators of Sustainable Development: Framework and Methodologies.” Commission on Sustainable Development. Ninth session. New York.

- UNESCO. 2010. “Teaching and Learning for a Sustainable Future: Four Dimensions of Sustainability.” Paris, France: Author. http://www.unesco.org/education/tlsf/mods/theme_a/popups/mod04t01s03.html

- Valentin, A., and J. H. Spangenberg. 2000. “A Guide to Community Sustainability Indicators.” Journal of Environmental Impact Assessment Review 20 (3): 381–392. doi:10.1016/S0195-9255(00)00049-4.

- Warner, L. A. 2014. “Using the Delphi Technique to Achieve Consensus: A Tool for Guiding Extension Programs.” EDIS: UF/IFAS Extension. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/WC/WC18300.pdf

- WCED. 1987. Our Common Future, 4. Oxford, New York: Oxford University, Press.

- Yang, L., B. Huang, M. Mao, L. Yao, S. Niedermann, W. Hu, and Y. Chen. 2016. “Sustainability Assessment of Greenhouse Vegetable Farming Practices from Environmental, Economic, and Socioinstitutional Perspectives in China.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 23 (17): 17287–17297. doi:10.1007/s11356-016-6937-1.