ABSTRACT

Landscape preference (LP) studies highlight one of the most important issues of human-environment relationship, and their related publications have increased rapidly over the last two decades. However, there is no systematic review with a holistic understanding of this field. here we applied a bibliometric approach to examine the evolution of LP research and identify its status and future prospects. We obtained 7,637 LP research publications from Web of Science core collection from 1968 to 2019 and analyzed the characteristics of publication outputs as well as performances in various countries and institutions. Besides, content keywords analysis was conducted to discover the drivers, focus, motivation, and trends of LP research. We found that 1) publications, subject categories, and active journals increased rapidly since the 2000s ; 2) the USA, England, and Australia are the leading countries in LP research, while China is starting to have some influence; 3) LP research is most closely linked to ecological and environmental studies, being developed by objective drivers, i.e., interactions with landscape change, and subjective motivations ; and 4) LP research is advancing the landscape sustainability science, integrating natural and social science together through ecosystem services. By comprehensively reviewing the evolution and prospect of LP research, we provide insights for further research in this field.

Introduction

Urbanization is a universal socio-economic phenomenon taking place worldwide, which significantly changes land use composition and configuration, and gradually transforms traditional rural landscapes into urban ones (Antrop Citation2000; Domon Citation2011; Forman Citation2019). In this process, the way people use and shape landscapes have changed (Antrop Citation2005; Deng et al. Citation2009; Křováková et al. Citation2015), as well as their values, perceptions, and preferences toward the landscapes (Häfner et al. Citation2018; Pflüger, Rackham, and Larned Citation2010; Swanwick Citation2009; Beza Citation2010). These transitions increased the interest in assessing people’s attitudes and preferences for different landscapes, leading to widespread academic interest in this field over the years (Kerebel et al. Citation2019; Coeterier Citation1996; Dramstad et al. Citation2006; Howley, Donoghue, and Hynes Citation2012; Kaltenborn and Bjerke Citation2002). Researchers across a broad range of disciplines and subjects including geography, psychology, philosophy, sociology and anthropology, notably planning and landscape architecture, have investigated related questions (Gobster et al. Citation2007; Westling et al. Citation2014; Ostrom Citation2010; Vouligny, Domon, and Ruiz Citation2009; McGranahan Citation2008; Renetzeder et al. Citation2010; Li and Nassauer Citation2020). Knowing people’s LPs not only brings public interests into the planning process which promotes landscape democracy (Arler Citation2002), but also contributes to the evaluation of public policies which further helps decision-makers to produce better plans and designs (Pinto-Correia and Kristensen Citation2013; Tress and Tress Citation2003).

In general, LPs have been studied from multiple perspectives, such as (a) how people with different demographic characteristics hold views on various landscapes; (b) how different landscape attributes are studied from the aesthetic value perspective; and (c) how some psychological theories such as the sense of place affect people’s way of viewing the landscape. Specifically, demographic characteristics include cultural background (Yu Citation1995), education level (Svobodova et al. Citation2012; Van Den Berg, Vlek, and Coeterier Citation1998), gender (Lindemann-Matthies et al. Citation2010; Strumse Citation1996), age (Howley Citation2011; Swanwick Citation2009; Yamashita Citation2002), expertise (Strumse Citation1996; Vouligny, Domon, and Ruiz Citation2009), environmental value orientations (Howley, Donoghue, and Hynes Citation2012; Jin Park et al. Citation2008; Soliva and Hunziker Citation2009), place of residence (Swanwick Citation2009; Van Den Berg and Koole Citation2006), and socio-economic status (Larsen and Harlan Citation2006; Swanwick Citation2009). These studies focus on different groups, such as the local inhabitants, experts, and general public (Hunziker et al. Citation2008), urban users (Almeida et al. Citation2016), women (Hami and Tarashkar Citation2018), children and adults (Tempesta Citation2010; Yamashita Citation2002), tourists (Fyhri, Jacobsen, and Tømmervik Citation2009), and different ethical groups (Buijs, Elands, and Langers Citation2009; Gobster Citation2002). Regarding landscape types, one of the most studied is agricultural landscapes which are forming new landscape functions such as recreation and tourism, considering as cultural heritage and can be preserved for future generations (Howley, Donoghue, and Hynes Citation2012; Sayadi, González-Roa, and Calatrava-Requena Citation2009). Other landscape types being studied include the forest (Jensen and Koch Citation2004), peri-urban (Ives and Kendal Citation2013), densely populated and fragmented (Di Giulio, Holderegger, and Tobias Citation2009), desert (Larsen and Harlan Citation2006; Yabiku, Casagrande, and Farley-Metzger Citation2008), plant and water (Hami and Tarashkar Citation2018; Kendal, Williams, and Williams Citation2012; Todorova, Asakawa, and Aikoh Citation2004), and energy landscape (Soini et al. Citation2011). Among these landscape types, there is a key distinction between the natural and constructed environment (Kaplan Citation1987; Lamb and Purcell Citation1990), and landscapes that are perceived as natural are considered more scenic than human-influenced (cultural) landscapes (Kent and Elliott Citation1995; Real, Arce, and Sabucedo Citation2000). Landscape attributes which are the physical characteristics of certain landscapes, have been verified to affect LPs (Scholte et al. Citation2018; Sevenant and Antrop Citation2009), and they are usually studied as quantifiable indicators to be used in landscape assessment (Tveit, Ode, and Fry Citation2006). In addition, the concept of “place attachment” has been commonly used in LPs field, for it provides a meaningful role that “place” plays in people’s lives, considering the nature of human experience, perception, and expression as related to the environment (Walker and Ryan Citation2008).

In LP research field, reviews are quite limited. The earliest review by Zube, Sell, and Taylor (Citation1982) analyzed articles from 1965 − 1980, identifying four paradigms (expert, psychophysical, cognitive, and experiential) in landscape value assessment. Lothian (Citation1999) proposed two paradigms (the objectivist and subjectivist) for landscape quality assessment, underlying surveys of the physical landscape and observer preferences. Gundersen et al. (Citation2016) reviewed forest preference research carried out in Finland, Sweden, and Norway, and discussed these findings in relation to bioenergy production in boreal forest ecosystems. In recent studies, Lee (Citation2017) reported on evolutionary theory and information-seeking preference hypothesis, which were reviewed to identify the ecological aesthetics of wetlands. Bubalo, van Zanten, and Verburg (Citation2019) summarized different crowdsourcing modes to collect geo-information on LPs, in the trend of using dedicated mobile apps and web-platforms to generate data. However, although LP research has been reviewed from various perspectives, they focused on specific aspects rather than the whole picture of this field.

In this study, we tried to reveal the trends and prospects in LP research from 1968 − 2019 based on the above-mentioned research progress and gaps. We split the target period (1968 − 2019) into four sub-periods, with two main objectives: 1) to investigate the overall development of this field by analyzing the publication numbers, journal types, and subject categories, and to outline the distribution patterns by analyzing the publication activities of nations and institutions; and 2) to explore topical issues and future perspectives in the field. Our findings provide comprehensive information on the evolution of LP research over 50 years, an overview of the status and trends in LP research, and insights into the potential for future research in this field.

Materials and analysis

Data acquisition

The Web of Science (WoS) core collection database contains the most reputable and influential journals, and is therefore recognized as the most authoritative data source for studying publications of most subjects (Zhao et al. Citation2019). Although Scopus has a wider range of coverage than WoS, there are significant overlaps between them. Archambault, David, and Yves (Citation2009)compared the bibliometric statistics gathered from WoS and Scopus and found that articles collected from the two databases were highly correlated, which means there will not be significant differences when choosing the two databases. The search results of WoS can be classified and sorted by various analysis needs, such as the subject categories, active journals, countries and institutions, etc. Also, these search results can be imported into other document management software such as Excel and CiteSpace for deeper quantitative data analysis (Wu and Ren Citation2019; Zhao et al. Citation2019; Meerow and Newell Citation2015; Zhang et al. Citation2020). Based on this, WoS can effectively explore the history, development and applications of a theme and track its current research hotspots. Other databases like Google Scholar and CNKI are not able to do quantitative analysis as WoS, so we only cited articles from them to do qualitative content analysis as a complementary to make sure that the research result is valid enough.

Peer-reviewed scientific literature was retrieved from the WoS core collection, initially with no time restriction on publication, through a topic search of the WoS database to collect all literature that contained one of the several search terms () in their titles, abstracts, or keywords. According to the research goals, articles and reviews which accounted for the 85% publications of all the document types were included in the analysis, while other types (i.e., proceeding paper and book chapter) were excluded. Moreover, to avoid unnecessary interference when doing the analysis, some biology, chemistry, and medicine related subjects that were irrelevant to this study were deliberately excluded. After these filtering steps, a total of 7,637 documents in English (published before 31 October 2019) were retrieved. According to the search result, the earliest paper was published in 1968 (English Citation1968). Therefore, papers published between 1968 and 2019 were selected for the study analysis. As extracting keywords for analysis is difficult before 1990, this period was then subdivided into four-time intervals (pre−1990, 1990 − 1999, 2000 − 2009, and 2010 − 2019) (Z. Wu and Ren Citation2019).

Table 1. Search terms applied to title, abstract and keywords in WoS

Analysis methods

In this study, we adopted the bibliometric analysis method which has been applied across several disciplines (Meerow and Newell Citation2015; Zhang et al. Citation2020; Zhao et al. Citation2019). Bibliometric analysis describes the characteristics of specific categories of literature through various mathematical and statistical techniques, assesses the performance and cooperation of authors, institutions, and countries, discovers research priorities, and reveals research trends and future prospects (Z. Wu and Ren Citation2019). Hence, using such a quantitative method to analyze the previously published data can clarify the evolution of LP research in an accurate and comprehensive way, which would not only be beneficial for researchers studying LPs but also generate insights by coupling information provided by other disciplines. In this study, except for the main search engine of WoS and the complementary search engine of Scopus, Google Scholar, and CNKI, other software programs like CiteSpace and VOS were selected for the bibliometric analysis. CiteSpace can process large-scale data generated by numerous scientific documents, and can easily extract information by time slice (Chen Citation2006). VOSviewer has unique advantages in mapping knowledge domain displays, and its layered label structure can clearly display dense network node interactions (Van Eck and Waltman Citation2010). Besides, ArcGIS software was used to generate geographic visualization maps.

Also, content analysis can be conducted to analyze keywords that were extracted from a large amount of literature (Si et al. Citation2019). Keyword analysis can reflect hot issues and how they evolved with time in a specific field. In this study, three main types of keyword analysis were employed:

1) High-frequency keyword co-occurrence analysis, in which all keywords in the three time periods were extracted, i.e., 120, 783, and 848 keywords for the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s respectively. As keywords before 1990 were not available, they were not included in the analysis. Subsequently, duplicate detection and merging were performed in Excel by a manual check. Some keywords which were separately appeared in one article were merged, such as “landscape” and “preference” were replaced by “landscape preference;” “landscape” and “perception” were merged into “landscape perception;” “landscape” and “ecology” became “landscape ecology.” Based on this merging of keywords, we obtained the most frequently used keywords for the 1990s, 2000s, 2010s.

2) Burst word analysis, which calculated the growth rate of keywords based on the frequency of words appeared in literature titles and abstracts. The higher the number of the burst, the more attention it receives. Therefore, burst words can also represent hotspot issues in some time periods.

3) Keyword clustering analysis, which was applied to re-allocate retrieved information and investigate the evolution of a specific research area to provide reasonable predictions of future trends (Wu and Ren Citation2019). We made a keyword research hotspot clustering network map visualized by the VOS viewer, where keywords are clustered in different colors, representing different research themes. The specific description of the keyword analysis can be seen in the following sections.

Result

Evolution of publication activities of landscape preference research

Publications, subject categories, and active journals

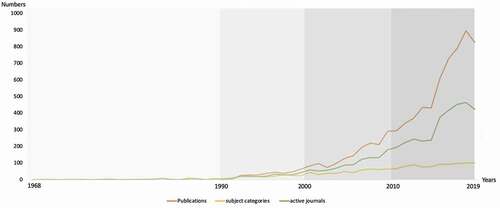

According to the number of LP publications, subject categories, and active journals each year from 1968 to 2019 (), there was stagnation between 1968 − 1989. Since 1990, LP research entered a period of rapid development, with several peaks in 1996, 2007, and 2013, covering the three time periods. Overall, there were only 46 publications before 1990; but after 1990, the number of LP publications started to increase steadily and reached the maximum of 897 in 2018. From the trend, it can be predicted that the publication of LP studies in 2019 will exceed that in 2018.

Figure 1. Numbers of landscape preference publications, subject categories, and active journals by year

Early studies on LP were mainly about human-environment relationships and the methods to explore them. Hence, a high proportion of LP publications were in ecology, geography, environment, and psychology-related journals. In 1968, there was only one subject category, increasing to 101 by 2019 (). Among these subjects, ecology and environmental studies have always ranked the two highest since 1990 (). However, environmental studies replaced ecology with highest output since 2010. This suggests a closer relationship between LP research and environmental value orientations, which also reflects the growing awareness in society for environmental issues. Geography and geography physical were always among the top 10 list in the three time period, indicating that LP research is not only aesthetic, cognitive, or psychological, but also closely linked to some geographical spatial metrics such as land cover, land use and number of patches. Besides, publications belong to the categories of urban studies and regional urban planning accounted for a large proportion, reflecting the interests of public participation in landscape management. Biodiversity conservation is another important subject, rising year by year in the ranking, which suggested increasing attention being paid to efficient land use patterns that sustain high levels of biodiversity and economic returns.

Table 2. Evolution of publication volumes in the top 10 subject categories ranked in descending order over the three decades

The number of academic journals covering LP research has also increased significantly over time, and more and more new scientific journals were involving in this field. Before 1990, publications were concentrated in a small number of journals, with 10 journals accounted for 88.9% of all publications. In the following three periods, the percentage of publications contributed by the top 10 journals declined to 43.4%, 28.1%, and 20.6%, respectively (). In the 2010s, the top 10 journals (4.78% of 209 journals) published 1,178 papers (20.6% of 5,718 papers), with an average of 118 papers each; the remaining 199 journals (95.22% of 209 journals) published an average of 28 papers each, which was far less than those by the top 10 journals. This means that although an increasing number of journals focus on LP research, the most influential journals are limited to a scope (). Rankings of the journals also reveal the focus of this field. Since the 1990s, Landscape and Urban Planning has been ranking the first on the list of most productive journals. The focus of Landscape and Urban Planning is to “advance conceptual, scientific, and applied understandings of landscape in order to promote sustainable solutions for landscape change.” Publication frequency of LP research in this journal indicates the increasing attention paid to the interaction between people and landscape during the landscape change process. Besides, Land Use Policy, which was not on the top 10 list before 2010, ranked the second in the 2010s. This journal aims to provide policy guidance to governments and planners, suggesting that LP research is more connected to some practical issues concerned with the social, economic, political, legal, physical, and planning aspects of urban and rural land use.

Table 3. Evolution of publishing activity of the top 10 active journals ranked in descending order over the three decades

Countries and institutions

was the publications by top 10 countries that participated in LP research since 1990. Results showed a sharp increase in the participating countries, from only 12 before 1990 to 147 in the 2010s. However, the relative contributions of the top 10 countries has declined during the 52-year period: 96.15% (pre-1990), 86.78% (1990s), 85.25% (2000s), and 84.19% (2010s). The top 3 countries were always the USA, England, and Australia in the four time periods, contributing the most proportion of publications, i.e., 87.7%, 70.9%, 63.6%, 54.9%. Although China was not on the top 10 during the first three periods, it developed rapidly and ranked seventh in the 2010s. Actually, the publications from China has grown from zero in the 1990s to 325 in the 2010s. In addition, the composition of the top 10 most productive countries suggested that developing countries are still not producing many publications in the LP field.

Table 4. Top 10 most productive countries in landscape preference research ranked in descending order of publications over three decades

Although institutions from USA remained in the leading position over three decades (), its number of institutions on the top 10 lists showed a declining trend, from 8 to 6 to 5. This illustrated that institutions from other countries are starting to increase their influence. For instance, institutions from North European such as the University of Eastern Finland, Wageningen University Research, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, and Swiss Federal Institute for Forest Snow Landscape Research all occupied their positions on the top 10 lists. In the 2010s, despite China ranked seventh on the top 10 most productive countries, there were no Chinese institutions on the list, suggesting that China is still exploring in this field, with several different institutions in competition but no excellent leaders in this field.

Table 5. Top 10 most productive institutions in landscape preference research ranked in descending order of publications over three decades

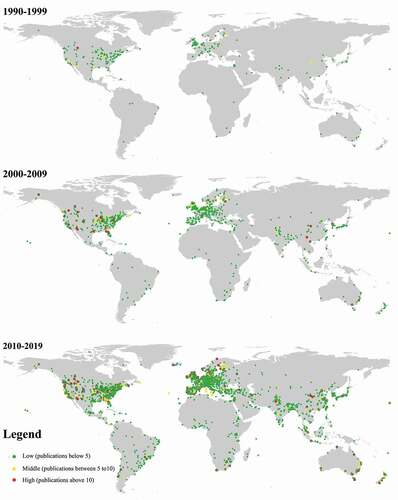

Geographic maps that represent the spatial distribution of publication activity among institutions were developed based on CiteSpace, and publication activity referred to the frequency of an institution being found in the author’s affiliations. Low, middle, and high activity corresponded to ≤5, 5–10, and ≥10 publications in each period, respectively. We refer to an institution with high publication activity as a research hotspot city. Before 1990, no cities showed high publication activity, and they were mainly distributed in American cities such as Blacksburg, Tucson, and European cities like Madrid (this period is not shown on the geographic distribution map). During the 1990s, although more cities started to do LP research, the overall publication level was still low. In 2000 − 2009, both the number of cities producing LP research and those that reached a high level of publication activity rapidly increased. Although LP research mainly occurred in the USA and Europe, there were some high-activity cities in East Asia and Australia. In 2010 − 2019, LP research activity significantly expanded to six continents, and high publication activities emerged in Africa, South America, and Oceania ().

Drivers, focus, motivations, and trends in landscape preference research

Objective drivers: interactions between landscape change and landscape preference

LP study is deeply connected with landscape change, and the interactions between them can be seen as the basic drivers developing LP study. In the early stage of LP research, the most frequently used keyword was “agriculture,” together with the burst keyword “rural landscape” (), which reflected that people paid much attention to the causes and effects of landscape change. Urbanization, which is defined as a complex process that transforms the rural or natural landscapes into urban and industrial ones (Antrop Citation2000), brought profound changes in rural areas. “counter-urbanization,” another form of urbanization, is the process that hobby farmers with an urban income moved to the countryside (Primdahl Citation2014), also deeply affected agricultural landscapes. Hence, there are remarkable land use changes such as intensification, specialization, and concentration of the agricultural sector (Pinto-Correia and Kristensen Citation2013), which further affected ecosystem functioning, biodiversity, and environmental quality, as well as human behavior, community structure, and social organization (Wu Citation2014; Yu et al. Citation2018). Based on this background, people’s perceptions toward rural landscapes changed accordingly. In the past, the main purpose of the agricultural landscape was to deliver provisioning services such as food and fuel (Häfner et al. Citation2018), but now, they are often summarized as cultural services, such as recreation, tourism, cultural heritage, and aesthetic functions (Häfner et al. Citation2018). Therefore, many researchers have explored the multifunctionality of agricultural landscapes (Ives and Kendal Citation2013; Willemen et al. Citation2010; Gulickx et al. Citation2013). Besides, researchers tried to find potential impacts of changing agricultural activities on scenic beauty (Hunziker and Kienast Citation1999) and solutions for the re-use of abandoned agricultural land (Ruskule et al. Citation2013), identify generic preferences for particular types of agricultural landscape attributes (Häfner et al. Citation2018; Van Zanten et al. Citation2014; Sayadi, González-Roa, and Calatrava-Requena Citation2009) to better preserve valuable territorial assets, and improve the cultural ecosystem services in rural areas (van Zanten et al. Citation2016). Also, urban users’ demand for the rural landscape has been studied (Almeida et al. Citation2016; Ives and Kendal Citation2013). Despite the urban population is generally referred to as “outsiders,” integrating their interests into rural policy and planning has shown to be influential in the dynamics of rural space and can be a step forward for rural communities (Almeida et al. Citation2016).

Table 6. Top 20 most frequently used keywords ranked in descending order over three decades

Table 7. Top 10 burst keywords in the landscape preference research field

On the other hand, LP study promoted landscape change by exerting landscape policies. For example, by understanding the LPs of both rural residents and hobby farmers from cities, the decision makers obtain significant data to be considered in policy implementation (Primdahl Citation2014), which in turn contribute to landscape change. Actually, a large number of rural LP studies are directed to landscape policies. van Zanten et al. (Citation2016) assessed how agricultural landscape features could contribute to aesthetic and recreational values, which supported the integration of cultural services in landscape policy. Howley, Donoghue, and Hynes (Citation2012) investigated factors that affect the general public’s preferences for traditional farming landscapes, providing some new ideas to encourage landscape conservation. Almeida et al. (Citation2016) identified urban users’ preferences for rural landscapes, forming a territorial approach to integrate landscape appreciation into land use planning practices. Ives and Kendal (Citation2013) studied the attitudes of city residents on peri-urban landscapes, providing a number of principles that should be considered by policymakers.

Three main focus: physical, socio-cultural, and aesthetic aspects

The European Landscape Convention stated (2000) that landscape is the integration of ecological, social, and visual qualities. Accordingly, the LPs related articles mainly involved these three aspects from different perspectives. Literature that mentioned the three aspects have various expressions, such as natural, social, and aesthetic landscape values (Solecka Citation2019); or physical, socio-cultural, and perceptual categories of public preference (Garcia et al. Citation2019). In this review, based on previous studies, we chose the concept of the physical, socio-cultural, and aesthetic as representative of different expressions. Within these concepts, a word that cannot be ignored is “value,” which was a high-frequency word in the 2010s; and “landscape value” was on the top 10 burst keywords (). Social and cultural research suggest that value is a psychological and cultural concept related to human perception (Sherrouse, Clement, and Semmens Citation2011), and landscape values can be seen synonymous of LP, as they both provide information about human needs and desires (Zube, Sell, and Taylor Citation1982).

Physical aspect

The physical aspect is associated with the elemental, structural, and functional characteristics of landscapes which are mainly studied in ecology (Solecka Citation2019). However, its close relationships with LPs is to explore how different physical characteristics are preferred (Marry et al. Citation2018). For instance, Lee (Citation2017) found 13 ecological attributes that would influence LPs of wetlands, which could further lead to behavioral choices. Besides, Solecka (Citation2019) reviewed articles and summarized 12 physical landscape values: native wildlife, vegetation, marine, fragility, productivity, natural history, renewal of groundwater resources, life-sustaining, biological diversity, ecological value, wilderness, and naturalness. Some of these physical landscape values reflect the most frequently used keywords in the three time periods (), such as “landscape ecology,” “conservation,” “vegetation,” “fragmentation,” “habitat,” “heterogeneity,” and “biodiversity.”

“Biodiversity,” defined as the variety of habitats or the richness of species in a given ecosystem (Dronova Citation2017), became a high-frequency word since the 2000s. Although “biodiversity” is mainly studied in landscape ecology, it is discussed in the context of LPs, such as whether preferences and biodiversity are compatible in urban green space, whether people appreciate ecologically rich environments, and the relationship between ecological characteristics, local society, and visitor preferences (Solecka Citation2019). Besides, there were several other keywords related to “biodiversity.” “Fragmentation,” which means to break cover types or habitat patches into smaller disconnected units (Fahrig Citation2003), is often seen as an ecological challenge. However, it has a societal perspective, i.e., how humans perceive landscape fragmentation and how this potentially influences human wellbeing (Di Giulio, Holderegger, and Tobias Citation2009). “Heterogeneity” is another keyword in landscape ecology, but connected with human needs. It can be seen from both physical and aesthetic sides. From the physical view, heterogeneity directly affects the diversity of color, form, texture, and thus, aesthetic properties of landscape elements that are relevant to human perceptions. From the aesthetic view, it is represented by terms such as “complexity,” “diversity,” “variety,” with specific definitions varying among research contexts (Dronova Citation2017). For example, in the studies which use landscape photographs, complexity often represents the overall visual richness and information content (Tveit, Ode, and Fry Citation2006).

In the physical aspect of LPs, except for landscape ecology related research, there are different landscape types being studied. However, on the top 20 most frequently used keywords, only “forest” was on the list over three decades. Jensen and Koch (Citation2004) had a 25 years of forest recreational preference research, finding that LPs of the forest is quite stable over the period. Even if leisure options have constantly increased, forest has been able to strengthen its position as a very significant recreation venue for the public.

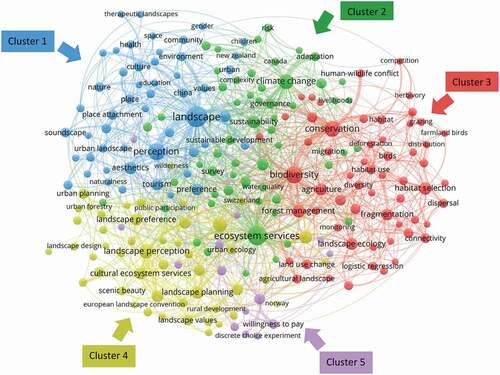

Socio-cultural aspect

The socio-cultural aspect is related to the individual’s social and cultural background, and factors that shape their personal views toward the tangible world (Garcia et al. Citation2019). Since the 2000s, “landscape perception” was the most frequently used keyword, with other keywords like “attitude” and “impact” indicated that researchers had more interest on how humans affect the landscape. In the clustering network diagram (), cluster 1 reflects the socio-cultural aspects through words like “place attachment,” “education,” and “therapeutic.” “Place attachment” is a complex psychological relationship between individuals and their environment, examining associations between users’ attachment and their levels of experience and interaction with a specific place (Kaltenborn and Bjerke Citation2002; Kyle, Mowen, and Tarrant Citation2004; García-Llorente et al. Citation2012). Studies have identified factors that affect people’s levels of place attachment, including life-cycle (e.g., age, family status), length of residency, and mobility (Walker and Ryan Citation2008). Besides, place attachment has been found to positively contribute to landscape planning and management. For instance, Walker and Ryan (Citation2008) found that people who expressed stronger levels of place attachment were more willing to engage in conservation and land use planning strategies. Lokocz, Ryan, and Sadler (Citation2011) and García-Llorente et al. (Citation2012) found that local residents’ attachment to the rural landscape was a strong motivation to engage in land stewardship and preservation efforts to sustain rural places and economies. In addition, “education” has been verified to affect LPs, and those with higher education levels are more likely to hold positive attitudes toward the preservation of certain landscapes (Li et al. Citation2019). Besides, the term “therapeutic landscapes” was first coined by health geographer Wilbert Gesler (1992) to explore why certain environments seem to contribute to a healing sense of place. Since then, this concept evolved and expanded as researchers examined the dynamic material, affective and socio-cultural roots, and routes to experiences of health and wellbeing in specific places (Bell et al. Citation2018).

Aesthetic aspect

The aesthetic aspect is linked to the individual’s affective and cognitive constructions generated on our relationship with the physical surroundings (Kaltenborn and Bjerke Citation2002; Gobster et al. Citation2007). Generally, there are two methods to aesthetic assessment (Lothian Citation1999): the objective method, which focus on landscape attributes, can be explained by evolutional preference theory; and the subjective method, which is about personal experiences, can be explained by cultural preference theory (Fry et al. Citation2009). Evolutionary theories claim that we respond positively to features that enhance survival and wellbeing (Kaplan Citation1987), and the cultural preference theories explain the beauty as essentially being in the eye of the beholder (Meinig Citation1979). “Scenic beauty,” a high-frequency word which is used to describe “visual quality” (Lee Citation2017), was usually used as an index to study factors that affect the aesthetic preference (Kalivoda et al. Citation2014; Wang, Zhao, and Liu Citation2016). Aesthetic factors may consider harmony, atmosphere, ephemeral, uniqueness, maintenance, sensory experiences, view, vastness, color, and admirability (Vouligny, Domon, and Ruiz Citation2009). In addition, most aesthetic preference studies used the photo-based method (Schirpke et al. Citation2019; Tieskens et al. Citation2018; Wang, Zhao, and Liu Citation2016; Barroso et al. Citation2012), and they include various environmental contexts ranging from cities to agricultural areas and wilderness (Daniel et al. Citation2012). “Choice experiment” is another popular burst keyword in the last five years. It is a method used to analyze what landscape attributes are preferred. It is rooted in traditional microeconomic theories of consumer behavior that are used to estimate attribute utilities based on an individual’s response to combinations of multiple decision attributes (Häfner et al. Citation2018).

Coupling bridge: ecosystem service

In the keyword clustering network, cluster 1 shows the socio-cultural aspect of LP while cluster 3 focus on the physical aspect of LP. They are relatively independent but connected by cluster 2, which is mainly about ecosystem service. Therefore, we carefully proposed that “ecosystem service” is a bridge that connects the three aspects of physical, socio-cultural, and aesthetic together. From the 2010s, “ecosystem service” became a high-frequency word (). It can be defined as the conditions, processes, and components of the natural environment that provide both tangible and intangible benefits for sustaining and fulfilling human life (Sherrouse, Clement, and Semmens Citation2011). Ecosystem services (ES) are broadly classed in four groups, i.e., provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural services. The physical aspect, such as biodiversity, is frequently attributed to the first three types of ES, while the aesthetic aspect is mainly discussed in the fourth type of ES as cultural ecosystem services (CES) (Cheng et al. Citation2019). We can see that the cluster 5, which is a very small part in the keyword clustering network, mainly shows the methods of quantifying the ES, such as willing to pay (WTP) and choice experiment. Hence, the cluster 5 can be seen as a branch of the cluster 2. Actually, quite a number of researchers have conducted a WTP exercise to estimate the monetary value of CES (Chaikaew, Hodges, and Grunwald Citation2017; Rewitzer et al. Citation2017; Van Berkel and Verburg Citation2014), also using choice experiment to estimate respondents’ preferences for landscape attributes (Grammatikopoulou, Badura, and Vačkářová Citation2020; Foelske et al. Citation2019; Häfner et al. Citation2018). Cues to Care (CTC), another important concept related to CES, was proposed by Nassauer (Citation2020). As designed landscape elements, it investigates the relationship between landscape perception and environmental function, which helps to create aesthetic value while maintaining other ESs.

Besides, many researchers have assessed the relationships of the three aspects, further showing that they are interconnected through the bridge of ES. For example, both Gobster et al. (Citation2007) and Tribot, Deter, and Mouquet (Citation2018) found that landscapes perceived as aesthetically pleasing were more likely to be conserved, thus understanding the ecological-aesthetic relationship can be important to improve conservation strategies and landscape management. Fry et al. (Citation2009) explored the conceptual common ground between visual and ecological landscape indicators which can be used to analyze different landscape functions, thus supporting the multiple-use planning. Dronova (Citation2017) found a substantial overlap between landscape ecology and aesthetic, finding that the diversity of land cover promotes the versatility of resources, habitats, and functional mechanisms, while producing a visual variety of colors, textures, and perceivable landscape elements. As for the relationship between the physical and socio-cultural Nassauer (Citation1995, 2009) did a lot of research on how cultural norms affect LPs, and then creating ecological functions by designing. In short, ecosystem service, originated from landscape ecology, has become a coupling bridge that integrates physical, socio-cultural, and aesthetic aspects in LP research.

Subjective motivation: implications for planning and management

The European Landscape Convention defines landscape as “an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural or human factors.” This definition underlines the necessity of LPs as a component of determining appropriate land use policies (Sevenant and Antrop Citation2009; Pearson and McAlpine Citation2010; Solecka Citation2019). Since the 2000s, “management” jumped to be the second most frequently used keywords (). In the clustering network (), keywords from cluster 4 such as “urban planning,” “landscape design,” and “landscape planning” suggested that LP research has close contact with landscape planning and management. Actually, planners and researchers have tried to conduct positive impact on landscape structures and compositions by studying how LPs could improve management practices. For instance, Pinto-Correia and Carvalho-Ribeiro (Citation2012) described the Index of Function Suitability to offer an integrated conceptual tool for incorporating social demands into landscape management. García-Llorente et al. (Citation2012) summarized the main public preference factors for river rehabilitation, which could assist decision-makers to anticipate conflicts and outline management strategies. Solecka (Citation2019) reviewed interdisciplinary literature to formulate a conceptual framework for integrating landscape value assessment with planning. In the decision-making process, Kristensen and Primdahl (Citation2020) proposed a landscape strategy making approach to engage multiple stakeholders rather than the expert-centered; Arler (Citation2002) studied on landscape democracy to realize equal co-determination and maximize preference satisfaction. “community,” another frequent keyword since the 2000s, reflects people’s increasing awareness of participatory planning. Community stakeholders are considered true experts of their environment, and public participation GIS, which combines community participation with the use of digital geospatial techniques, has been applied to engage the public and local stakeholders in decision-making under the collaborative planning paradigm (Fagerholm et al. Citation2012).

To increase public participation in LP research, some spatial data collection and mapping methods such as GIS, data visualization, and crowdsourcing tools are increasingly being used (Kienast et al. Citation2015; Simensen, Halvorsen, and Erikstad Citation2018; Bubalo, van Zanten, and Verburg Citation2019). These technical methods are gradually replacing and complementing traditional questionnaires and field observation-based tools, as they enable the in-situ collection of real-time location-based data. For example, Bubalo, van Zanten, and Verburg (Citation2019) reviewed literature and offered a summary of different crowdsourcing modes to collect geo-information on LPs. These crowdsourcing modes range from harvesting information passively transmitted by large groups on the web to actively engaging the crowd to generate data by using dedicated mobile apps and web-platforms. These techniques help to visualize LPs to mobilize public engagement in land use planning, so as to maintain and increase landscape quality. In short, to make full use of the implications of LPs on landscape planning and management, both the public participation and the related data collection and mapping methods are indispensable.

New trends: an ecosystem-service-oriented approach

Keywords such as “climate change” and “adaptation” showed up in the keyword clustering network, and researchers have been studying the stakeholder preference toward ecosystem-based approaches for climate change to support adaptation planning (Krkoška Lorencová et al. Citation2021). Besides, how to reconcile the relationship between the long-term objectives of healthy ecosystem services and the immediate needs of improving visual landscape quality needs to be considered. Actually, an ecological aesthetic discourse on to what extent landscapes are both functional and visually pleasing has been discussed, demonstrating that the trend of LP study would be the integration of natural and social science by an ecosystem-service-oriented approach (ESO). For instance, Sherrouse, Clement, and Semmens (Citation2011) described a GIS application for assessing, mapping, and quantifying the social values of ES, which integrates preference survey results with data characterizing the physical environment of the study area. Another approach of Landscape Character Assessment also helps to integrate the physical and socio-cultural aspects of landscapes. It is a process of describing, mapping, and evaluating distinct characters in the landscape used by several researchers (Simensen, Halvorsen, and Erikstad Citation2018; Atik et al. Citation2017) to combine map-based biophysical information and on-site visual landscape characteristics.

We propose this ESO approach because it can further promote LP studies. LP research deals with the identification of landscape values that is subjective, but ESO approach is based on knowledge of landscape characters which is relatively objective. This objective paradigm has been proposed as landscape indicators (Tveit, Ode, and Fry Citation2006; Fry et al. Citation2009; Schirpke et al. Citation2019). Landscape indicators were firstly used in landscape ecology to assess the essential characteristics of landscapes, but they are gradually developed in sociological studies to quantify LPs. In the 2010s, “indicator” became one of the most frequently used keywords and researchers were starting to adopt this integrated approach. Tveit, Ode, and Fry (Citation2006) identified nine visual concepts to assess different visual landscape characters. Subsequently, Ode et al. (Citation2009) explored the relationship between LPs and some landscape indicators extracted from the visual concept of naturalness. Kienast et al. (Citation2015) introduced the Swiss Landscape Monitoring Program with a comprehensive indicator set to monitor physical landscape patterns and their perception by the local population. Sowińska-Świerkosz and Chmielewski (Citation2016) introduced Landscape Quality Objectives as a set of indicators that consider natural, cultural, and aesthetic landscape values to be applied in the process of landscape planning and management. To conclude, landscape indicators help us explore the conceptual common ground between landscape ecology and aesthetics, contributing to a better understanding of landscape functions and improving landscape analysis methods. Thus, they can be useful tools for the future landscape planning and management. Hence, in LP studies, indicators across different landscape types and different groups of observers should be tested to provide objective criteria and support the ESO approach (Fry et al. Citation2009).

Discussion

Development of landscape preference research

This study used the bibliometric method to offer a holistic view of the LP research evolution, which was rarely studied before. The method combined both quantitative and qualitative analysis, analyzing data about the progress of publication activities and keywords about the focus and trends in LP research, respectively. Results showed both the objective drivers and subjective motivations for the development of LP research. Objectively, the preference study was started and promoted by landscape change, which is mainly driven by urbanization (Antrop Citation2000; Yu et al. Citation2019a). Owing to landscapes changing at an unprecedented speed, the number of LP publications, subject categories, and active journals are all rising yearly despite some stagnations, and we predict the numbers will reach the highest peak in 2019. As landscape change is a complex process involving different fields such as geography, psychology, philosophy, sociology, and anthropology, LP research should be interdisciplinary. However, in the early stages, commonly one article only studied one subject of LPs such as how to view environmental preference from an evolutionary perspective (Kaplan Citation1987), cultural variations and group differences in landscape preference (Yu Citation1995; Van Den Berg, Vlek, and Coeterier Citation1998), or the philosophy of landscape aesthetics (Lothian Citation1999). In recent years, researchers started to cross the disciplines and combine different subjects in one article, such as integrating the landscape aesthetic preference and ecological quality (Tribot, Deter, and Mouquet Citation2018), and how to make use of place attachment to affect landscape conservations (Lee and Lee Citation2017; Verbrugge and Van Den Born Citation2018).

Subjectively, researchers and planners are motivated to study LPs because they want to know more about human needs to provide better policies. Therefore, the implications for planning and management can be seen as research motivations of LP research. Previous research has explored conceptual tools and practical techniques to incorporate public demands into landscape planning and management, with the challenge of lacking specific guidance targeted at specific regions (Howley Citation2011). Another challenge for researchers and planners is evaluating the public’s understanding of planning tools and techniques (Walker and Ryan Citation2008). Owing to the various demographic backgrounds such as different educational levels and environmental values, understandings of landscape policies could vary from person to person. Therefore, which group’s attitudes and opinions deserve the most attention and should be most valued in a specific area remains to be studied in future research.

Furthermore, results indicated that traditional LP research mainly focuses on the physical, socio-cultural, and aesthetic aspects of landscapes (Solecka Citation2019; Garcia et al. Citation2019). These characteristics include a broad range of problems to be solved in LP research. For example, which landscape attributes are more valued by people? What is the relationship between landscape ecology and human cognition? Which demographic factors could have more influence on people’s preferences toward certain landscape? How to define the human emotional bond with a specific place from the psychological perspective? What is the landscape aesthetic assessment and what methods could be used to examine people’s aesthetic preference? Traditional LP research was dedicated to exploring answers for these related questions. However, LP research is currently crossing the boundaries and starting to be combined with some hot topics, like climate change and social-ecological systems, whose main task is addressing the sustainability issue.

Toward a landscape sustainability paradigm

Landscape preference, as an important branch of landscape science, has interacted with other elements like landscape change and ecosystem service. To make it clearer, we developed a loop here to show their relationships and how it is directed to landscape sustainability (). As we stated above, LP study is driven by landscape change, which happens during the urbanization process. As urbanization has brought several environmental problems that made our cities unsustainable, “sustainability” has become the theme of our time and “urban sustainability” can be seen as the ultimate goal of urbanization (Wu Citation2010). To achieve urban sustainability, we first need to design and build better cities to achieve landscape sustainability because cities are the most heterogeneous landscapes (Wu Citation2010).

Figure 4. Relationships flow between landscape change, landscape preference, ecosystem service, and landscape sustainability

Actually, landscape scientists have been studying landscape sustainability for over three decades, with a plurality of perspectives and methods (Zhou, Wu, and Anderies Citation2019), including topics like ecosystem service, landscape ecology, landscape planning, and agricultural landscape, as well as some new topics like climate adaption planning (Yu et al. Citation2020). These topics can fit with the main topics in LP research, as seen in the keyword research hotspot clustering network diagram (). Therefore, LP study is not an isolated discipline anymore, but it is moving toward a multidisciplinary landscape sustainability paradigm. Furthermore, the center of LP study is to address the issue of human-environment interactions while landscape sustainability aims to enhance the sustainability of human wellbeing (Zhou, Wu, and Anderies Citation2019; Yang et al. Citation2020), here they show an overlap on the main goals, hence LP research has great implications to advance the development of landscape sustainability.

Besides, LP research is closely linked to landscape sustainability through ecosystem service, which not only connects three aspects (physical, socio-cultural, aesthetic) of landscape preference, but also guides them to landscape sustainability through four main services, i.e., provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural service. Through the bridge role of ecosystem service, public preferences and social values can be quantified by some technological applications, and landscape aesthetic values, which are intangible, can be measured by indicators extracted from landscape ecology. Therefore, in the future, LP research would not be human-centered but should be studied from the landscape sustainability perspective, where human and environment can coexist and have mutual promotions and development.

Limitations

Despite great implications of LPs research, and preference surveys are able to collect answers from different parts of the population, there are a couple of problems (Arler Citation2002). First, people’s wishes are not always consistent and sometimes they even want two mutually exclusive landscape features, such as more songbirds but fewer insects (Arler Citation2002). Second, the pictures of landscapes that are used to be evaluated through the survey are usually isolated from its background, thus the local history or other relevant features could be ignored. Third, few people could have thoroughly considered the landscape, and their LPs can be changeable once they get more knowledge of an area.

As for this review, there were also some limitations. First, our use of English language literature may overlook some important LP studies and bias attention toward Western culture. Second, although we found WoS to be the most comprehensive database, and publications from it can represent the whole picture of LP research, it still excludes many books and is limited to journals registered by it. Besides, the study did not include other databases such as Google Scholar, Scopus, Medline, and Zetoc to do quantitative analysis, which may have limited the scope of data collection (although we have employed many related literatures from them to do further and detailed qualitative analysis). Third, we may have introduced errors in data formatting by relying on CiteSpace to conduct our keyword frequency analysis; and the different parameter settings for VOSviewer may produce different keyword clustering visualization results.

Conclusion

This review was the first to apply a bibliometric approach to analyze LP research publications and provides a systematic and holistic view about the past trends and future prospects in this field. A total of 7,637 publications were retrieved from the core collection of the WoS database from 1968 to 2019, and this time period was subdivided into four-time intervals (pre-1990, 1990 − 1999, 2000 − 2009, and 2010 − 2019) to better compare the temporal trends. We conducted a quantitative analysis of publication activity, finding that the number of LP publications, subject categories, and active journals increased yearly since 1968 and developed quickly in the recent two decades. Although LP research involves several disciplines, it was most strongly linked to ecological and environmental studies, indicating that the central issue of LP research is the human-environment relationship. As for the active journals, Landscape and Urban Planning was the most influential one in LP research and Land Use Policy is developing at an astonishing speed. In addition, the results showed that the three leading countries, i.e., the USA, England, and Australia, are from different continents, but their influences are decreasing owing to the emergence of developing countries like China, which are producing an increasing number of publications in LP research.

Further, we identified the objective drivers and subjective motivations of LP research. LP research is driven by its interactions with the landscape change, and researchers are motivated to study it because it has great implications for landscape planning and management. Traditional LP research focuses on three separate aspects, i.e., physical, socio-cultural, and aesthetic, where problems are studied individually without the integration of other disciplines. However, there is a new LP research direction, with ecosystem service as a bridge connecting the three aspects, and more researchers are starting to explore their relationships. This helps LP research to develop toward a more sustainable direction, with the combination of natural and social science. This systematic review of LP research may provide insights for further research in this field.

HIGHLIGHTS

Landscape preference research was systematically reviewed using a bibliometric approach.

We assessed the evolution of landscape preference publication activities.

We identified the development potential of landscape preference research.

Landscape preference research is developing towards a sustainable direction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Almeida, M., I. Loupa-Ramos, H. Menezes, S. Carvalho-Ribeiro, N. Guiomar, and T. Pinto-Correia. 2016. “Urban Population Looking for Rural Landscapes: Different Appreciation Patterns Identified in Southern Europe.” Land Use Policy 53: 44–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.09.025.

- Antrop, M. 2000. “Changing Patterns in the Urbanized Countryside of Western Europe”. Landscape Ecology, no. 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008151109252.

- Antrop, M. 2005. “Why Landscapes of the past are Important for the Future”. Landscape and Urban Planning, no. 1–2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2003.10.002.

- Archambault, É., C. David, and G. Yves. 2009. “Comparing Bibliometric Statistics Obtained from theWeb of Science and Scopus.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60 (7): 1320–1326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.

- Arler, F. 2002. “A True Landscape Democracy.” In Humans in the Land: The Ethics and Aaesthetics of the Cultural Landscape, edited by S. Arntzen and E. Brady, 75–99, Fagbokforlaget.

- Atik, M., R. C. Işıklı, V. Ortaçeşme, and E. Yıldırım. 2017. “Exploring a Combination of Objective and Subjective Assessment in Landscape Classification: Side Case from Turkey.” Applied Geography 83: 130–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.04.004.

- Barroso, F. L., T. Pinto-Correia, I. L. Ramos, D. Surová, and H. Menezes. 2012. “Dealing with Landscape Fuzziness in User Preference Studies: Photo-based Questionnaires in the Mediterranean Context.” Landscape and Urban Planning 104 (3–4): 329–342. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.11.005.

- Bell, S. L., R. Foley, F. Houghton, A. Maddrell, and A. M. Williams. 2018. “From Therapeutic Landscapes to Healthy Spaces, Places and Practices: A Scoping Review.” Social Science & Medicine 196 (November 2017): 123–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.035.

- Beza, B. B. 2010. “The Aaesthetic Value of A Mountain Landscape: A Study of the Mt. Everest Trek.” Landscape and Urban Planning 97 (4): 306–317. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.07.003.

- Bubalo, M., B. T. van Zanten, and P. H. Verburg. 2019. “Crowdsourcing Geo-information on Landscape Perceptions and Preferences: A Review.” Landscape and Urban Planning 184 (February 2018): 101–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.01.001.

- Buijs, A. E., B. H. M. Elands, and F. Langers. 2009. “No Wilderness for Immigrants: Cultural Differences in Images of Nature and Landscape Preferences”. Landscape and Urban Planning, no. 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2008.12.003.

- Chaikaew, P., A. W. Hodges, and S. Grunwald. 2017. “Estimating the Value of Ecosystem Services in A Mixed-use Watershed: A Choice Experiment Approach.” Ecosystem Services. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.12.015.

- Chen, C. 2006. “CiteSpace II: Detecting and Visualizing Emerging Trends and Transient Patterns in Scientific Literature”. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, no. 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20317.

- Cheng, X., S. Van Damme, L. Li, and P. Uyttenhove. 2019. “Evaluation of Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Review of Methods.” Ecosystem Services 37 (April): 100925. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.100925.

- Coeterier, J. F. 1996. “Dominant Attributes in the Perception and Evaluation of the Dutch Landscape.” Landscape and Urban Planning 34 (1): 27–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(95)00204-9.

- Daniel, T. C., A. Muhar, A. Arnberger, O. Aznar, J. W. Boyd, K. M. A. Chan, … A. Von Der Dunk. 2012. “Contributions of Cultural Services to the Ecosystem Services Agenda.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (23): 8812–8819. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1114773109.

- Deng, J. S., K. Wang, Y. Hong, and J. G. Qi. 2009. “Spatio-temporal Dynamics and Evolution of Land Use Change and Landscape Pattern in Response to Rapid Urbanization.” Landscape and Urban Planning 92 (3–4): 187–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2009.05.001.

- Di Giulio, M., R. Holderegger, and S. Tobias. 2009. “Effects of Habitat and Landscape Fragmentation on Humans and Biodiversity in Densely Populated Landscapes.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (10): 2959–2968. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.05.002.

- Domon, G. 2011. “Landscape as Resource: Consequences, Challenges and Opportunities for Rural Development.” Landscape and Urban Planning 100 (4): 338–340. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.02.014.

- Dramstad, W. E., M. S. Tveit, W. J. Fjellstad, and G. L. A. Fry. 2006. “Relationships between Visual Landscape Preferences and Map-based Indicators of Landscape Structure.” Landscape and Urban Planning 78 (4): 465–474. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.12.006.

- Dronova, I. 2017. “Environmental Heterogeneity as a Bridge between Ecosystem Service and Visual Quality Objectives in Management, Planning and Design.” Landscape and Urban Planning 163: 90–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.03.005.

- English, P. W. 1968. “Landscape, Ecosystem, and Environmental Perception: Concepts in Cultural Geography.” Journal of Geography 67 (4): 198–205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00221346808980928.

- Fagerholm, N., N. Käyhkö, F. Ndumbaro, and M. Khamis. 2012. “Community Stakeholders’ Knowledge in Landscape Assessments - Mapping Indicators for Landscape Services.” Ecological Indicators. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.12.004.

- Fahrig, L. 2003. “Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Biodiversity”. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, no. 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132419.

- Foelske, L., C. J. Van Riper, W. Stewart, A. Ando, P. Gobster, and L. Hunt. 2019. “Assessing Preferences for Growth on the Rural-urban Fringe Using a Stated Choice Analysis.” Landscape and Urban Planning 189 (October 2018): 396–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.05.016.

- Forman, R. T. T. 2019. “Town Ecology: For the Land of Towns and Villages.” Landscape Ecology 34 (10): 2209–2211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00890-z.

- Fry, G., M. S. Tveit, Å. Ode, and M. D. Velarde. 2009. “The Ecology of Visual Landscapes: Exploring the Conceptual Common Ground of Visual and Ecological Landscape Indicators.” Ecological Indicators 9 (5): 933–947. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2008.11.008.

- Fyhri, A., J. K. S. Jacobsen, and H. Tømmervik. 2009. “Tourists’ Landscape Perceptions and Preferences in a Scandinavian Coastal Region.” Landscape and Urban Planning 91 (4): 202–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2009.01.002.

- Garcia, X., M. Benages-Albert, M. Buchecker, and P. Vall-Casas. 2019. “River Rehabilitation: Preference Factors and Public Participation Implications.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 0 (0): 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1680353.

- García-Llorente, M., B. Martín-López, I. Iniesta-Arandia, C. A. López-Santiago, P. A. Aguilera, and C. Montes. 2012. “The Role of Multi-functionality in Social Preferences toward Semi-arid Rural Landscapes: An Ecosystem Service Approach.” Environmental Science & Policy 19–20: 136–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.01.006.

- Gobster, P. H. 2002. “Managing Urban Parks for a Racially and Ethnically Diverse Clientele.” Leisure Sciences 24 (2): 143–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400252900121.

- Gobster, P. H., J. I. Nassauer, T. C. Daniel, and G. Fry. 2007. “The Shared Landscape: What Does Aaesthetics Have to Do with Ecology?.” Landscape Ecology 22 (7): 959–972. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-007-9110-x.

- Grammatikopoulou, I., T. Badura, and D. Vačkářová. 2020. “Public Preferences for Post 2020 Agri-environmental Policy in the Czech Republic: A Choice Experiment Approach.” Land Use Policy 99 (August 2019): 104988. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104988.

- Gulickx, M. M. C., P. H. Verburg, J. J. Stoorvogel, K. Kok, and A. Veldkamp. 2013. “Mapping Landscape Services: A Case Study in A Multifunctional Rural Landscape in the Netherlands.” Ecological Indicators 24: 273–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.07.005.

- Gundersen, V., N. Clarke, W. Dramstad, and W. Fjellstad. 2016. “Effects of Bioenergy Extraction on Visual Preferences in Boreal Forests: A Review of Surveys from Finland, Sweden and Norway.” Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 31 (3): 323–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2015.1099725.

- Häfner, K., I. Zasada, B. T. van Zanten, F. Ungaro, M. Koetse, and A. Piorr. 2018. “Assessing Landscape Preferences: A Visual Choice Experiment in the Agricultural Region of Märkische Schweiz, Germany.” Landscape Research 43 (6): 846–861. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2017.1386289.

- Hami, A., and M. Tarashkar. 2018. “Assessment of Women’s Familiarity Perceptions and Preferences in Terms of Plants Origins in the Urban Parks of Tabriz, Iran.” Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 32 (December 2017): 168–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.04.002.

- Howley, P. 2011. “Landscape Aaesthetics: Assessing the General Publics’ Preferences Towards Rural Landscapes.” Ecological Economics 72: 161–169. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.09.026.

- Howley, P., C. O. Donoghue, and S. Hynes. 2012. “Exploring Public Preferences for Traditional Farming Landscapes.” Landscape and Urban Planning 104 (1): 66–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.09.006.

- Hunziker, M., P. Felber, K. Gehring, M. Buchecker, N. Bauer, and F. Kienast. 2008. “Evaluation of Landscape Change by Different Social Groups.” Mountain Research and Development 28 (2): 140–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1659/mrd.0952.

- Hunziker, M., and F. Kienast. 1999. “Potential Impacts of Changing Agricultural Activities on Scenic Beauty - A Prototypical Technique for Automated Rapid Assessment.” Landscape Ecology 14 (2): 161–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008079715913.

- Ives, C. D., and D. Kendal. 2013. “Values and Attitudes of the Urban Public Towards Peri-urban Agricultural Land.” Land Use Policy 34: 80–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.02.003.

- Jensen, F. S., and N. E. Koch. 2004. “Twenty-five Years of Forest Recreation Research in Denmark and Its Influence on Forest Policy.” Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, Supplement 19 (sup004): 93–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14004080410034173.

- Jin Park, J., A. Jorgensen, C. Swanwick, and P. Selman. 2008. “Relationships between Environmental Values and the Acceptability of Mobile Telecommunications Development in a Protected Area.” Landscape Research 33 (5): 587–604. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390801948398.

- Kalivoda, O., J. Vojar, Z. Skřivanová, and D. Zahradník. 2014. “Consensus in Landscape Preference Judgments: The Effects of Landscape Visual Aaesthetic Quality and Respondents’ Characteristics.” Journal of Environmental Management 137: 36–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.02.009.

- Kaltenborn, B. P., and T. Bjerke. 2002. “Association between Environmental Value Orientations and Landscape Preferences.” Landscape and Urban Planning 59 (1): 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(01)00243-2.

- Kaplan, S. 1987. Aaesthetics, Affect, and Cognition: Environmental Preference from an Evolutionary Perspective. 3–32. Environment and Behavior. pp. 3–32. Sage Publication, Inc.

- Kendal, D., K. J. H. Williams, and N. S. G. Williams. 2012. “Plant Traits Link People’s Plant Preferences to the Composition of Their Gardens.” Landscape and Urban Planning 105 (1–2): 34–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.11.023.

- Kent, R. L., and C. L. Elliott. 1995. “Scenic Routes Linking and Protecting Natural and Cultural Landscape Features: A Greenway Skeleton.” Landscape and Urban Planning 33 (1–3): 341–355. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(94)02027-D.

- Kerebel, A., N. Gélinas, S. Déry, B. Voigt, and A. Munson. 2019. “Landscape Aaesthetic Modelling Using Bayesian Networks: Conceptual Framework and Participatory Indicator Weighting.” Landscape and Urban Planning 185 (February): 258–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.02.001.

- Kienast, F., J. Frick, M. J. van Strien, and M. Hunziker. 2015. “The Swiss Landscape Monitoring Program - A Comprehensive Indicator Set to Measure Landscape Change.” Ecological Modelling 295: 136–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2014.08.008.

- Kristensen, L. S., and J. Primdahl. 2020. “Landscape Strategy Making as a Pathway to Policy Integration and Involvement of Stakeholders: Examples from a Danish Action Research Programme.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 63 (6): 1114–1131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1636531.

- Krkoška Lorencová, E., L. Slavíková, A. Emmer, E. Vejchodská, K. Rybová, and D. Vačkářová. 2021. “Stakeholder Engagement and Institutional Context Features of the Ecosystem-based Approaches in Urban Adaptation Planning in the Czech Republic.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 58 (December 2020): 126955. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126955.

- Křováková, K., S. Semerádová, M. Mudrochová, and J. Skaloš. 2015. “Landscape Functions and Their Change - a Review on Methodological Approaches.” Ecological Engineering 75: 378–383. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.12.011.

- Kyle, G. T., A. J. Mowen, and M. Tarrant. 2004. “Linking Place Preferences with Place Meaning: An Examination of the Relationship between Place Motivation and Place Attachment.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 24 (4): 439–454. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.11.001.

- Lamb, R. J., and A. T. Purcell. 1990. “Perception of Naturalness in Landscape and Its Relationship to Vegetation Structure.” Landscape and Urban Planning 19 (4): 333–352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(90)90041-Y.

- Larsen, L., and S. L. Harlan. 2006. “Desert Dreamscapes: Residential Landscape Preference and Behavior.” Landscape and Urban Planning 78 (1–2): 85–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.06.002.

- Lee, D., and J. H. Lee. 2017. “A Structural Relationship between Place Attachment and Intention to Conserve Landscapes – A Case Study of Harz National Park in Germany.” Journal of Mountain Science 14 (5): 998–1007. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-017-4366-3.

- Lee, L. H. 2017. “Perspectives on Landscape Aaesthetics for the Ecological Conservation of Wetlands.” Wetlands 37 (2): 381–389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-016-0873-1.

- Li, J., and J. I. Nassauer. 2020. “Cues to Care: A Systematic Analytical Review.” Landscape and Urban Planning 201. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103821.

- Li, X. P., S. X. Fan, N. Kühn, L. Dong, and P. Y. Hao. 2019. “Residents’ Ecological and Aaesthetical Perceptions toward Spontaneous Vegetation in Urban Parks in China.” Urban Forestry and Urban Greening. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126397.

- Lindemann-Matthies, P., R. Briegel, B. Schüpbach, and X. Junge. 2010. “Aaesthetic Preference for a Swiss Alpine Landscape: The Impact of Different Agricultural Land-use with Different Biodiversity.” Landscape and Urban Planning 98 (2): 99–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.07.015.

- Lokocz, E., R. L. Ryan, and A. J. Sadler. 2011. “Motivations for Land Protection and Stewardship: Exploring Place Attachment and Rural Landscape Character in Massachusetts.” Landscape and Urban Planning 99 (2): 65–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.08.015.

- Lothian, A. 1999. “Landscape and the Philosophy of Aaesthetics: Is Landscape Quality Inherent in the Landscape or in the Eye of the Beholder?.” Landscape and Urban Planning 44 (4): 177–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(99)00019-5.

- Marry, M. S., K. Asahiro, S. M. Asik Ullah, M. Moriyama, M. Tani, and M. Sakamoto. 2018. “Assessing Local People’s Preferences for Landscape Character in Teknaf Peninsula for Sustainable Landscape Conservation and Development.” International Review for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development 6 (2): 50–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.14246/irspsd.6.2_50.

- McGranahan, D. A. 2008. “Landscape Influence on Recent Rural Migration in the U.S.” Landscape and Urban Planning 85 (3–4): 228–240. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.12.001.

- Meerow, S., and J. P. Newell. 2015. “Resilience and Complexity: A Bibliometric Review and Prospects for Industrial Ecology.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 19 (2): 236–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12252.

- Meinig, D. W. 1979. “The Beholding Eye: Ten Versions of the Same Scene.” The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays 33–48.

- Nassauer, J. I. 1995. “Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames.” Landscape Journal 14 (2): 161–170. doi:https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.14.2.161.

- Ode, Å., G. Fry, M. S. Tveit, P. Messager, and D. Miller. 2009. “Indicators of Perceived Naturalness as Drivers of Landscape Preference.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (1): 375–383. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.10.013.

- Ostrom, E. 2010. “Polycentric Systems for Coping with Collective Action and Global Environmental Change.” Global Environmental Change 20 (4): 550–557. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.004.

- Pearson, D. M., and C. A. McAlpine. 2010. “Landscape Ecology: An Integrated Science for Sustainability in a Changing World.” Landscape Ecology 25 (8): 1151–1154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-010-9512-z.

- Pflüger, Y., A. Rackham, and S. Larned. 2010. “The Aaesthetic Value of River Flows: An Assessment of Flow Preferences for Large and Small Rivers.” Landscape and Urban Planning 95 (1–2): 68–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2009.12.004.

- Pinto-Correia, T., and L. Kristensen. 2013. “Linking Research to Practice: The Landscape as the Basis for Integrating Social and Ecological Perspectives of the Rural.” Landscape and Urban Planning 120: 248–256. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.07.005.

- Pinto-Correia, T., and S. Carvalho-Ribeiro. 2012. “The Index of Function Suitability (IFS): A New Tool for Assessing the Capacity of Landscapes to Provide Amenity Functions.” Land Use Policy 29 (1): 23–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.05.001.

- Primdahl, J. 2014. “Agricultural Landscape Sustainability under Pressure: Policy Developments and Landscape Change.” Landscape Research 39 (2): 123–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2014.891726.

- Real, E., C. Arce, and J. M. Sabucedo. 2000. “Classification of Landscapes Using Quantitative and Categorical Data, and Prediction of Their Scenic Beauty in North-western Spain.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 20 (4): 355–373. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2000.0184.

- Renetzeder, C., S. Schindler, J. Peterseil, M. A. Prinz, S. Mücher, and T. Wrbka. 2010. “Can We Measure Ecological Sustainability? Landscape Pattern as an Indicator for Naturalness and Land Use Intensity at Regional, National and European Level.” Ecological Indicators 10 (1): 39–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2009.03.017.

- Rewitzer, S., R. Huber, A. Grêt-Regamey, and J. Barkmann. 2017. “Economic Valuation of Cultural Ecosystem Service Changes to a Landscape in the Swiss Alps.” Ecosystem Services. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.06.014.

- Ruskule, A., O. Nikodemus, R. Kasparinskis, S. Bell, and I. Urtane. 2013. “The Perception of Abandoned Farmland by Local People and Experts: Landscape Value and Perspectives on Future Land Use.” Landscape and Urban Planning 115: 49–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.03.012.

- Sayadi, S., M. C. González-Roa, and J. Calatrava-Requena. 2009. “Public Preferences for Landscape Features: The Case of Agricultural Landscape in Mountainous Mediterranean Areas.” Land Use Policy 26 (2): 334–344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.04.003.

- Schirpke, U., G. Tappeiner, E. Tasser, and U. Tappeiner. 2019. “Using Conjoint Analysis to Gain Deeper Insights into Aaesthetic Landscape Preferences.” Ecological Indicators 96 (January 2018): 202–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.09.001.

- Scholte, S. S. K., M. Daams, H. Farjon, F. J. Sijtsma, A. J. A. van Teeffelen, and P. H. Verburg. 2018. “Mapping Recreation as an Ecosystem Service: Considering Scale, Interregional Differences and the Influence of Physical Attributes.” Landscape and Urban Planning 175 (March): 149–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.03.011.

- Sevenant, M., and M. Antrop. 2009. “Cognitive Attributes and Aaesthetic Preferences in Assessment and Differentiation of Landscapes.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (9): 2889–2899. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.10.016.

- Sherrouse, B. C., J. M. Clement, and D. J. Semmens. 2011. “A GIS Application for Assessing, Mapping, and Quantifying the Social Values of Ecosystem Services.” Applied Geography 31 (2): 748–760. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.08.002.

- Si, H., J. G. Shi, D. Tang, S. Wen, W. Miao, and K. Duan. 2019. “Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Environmental Science: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, no. 15. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152788.

- Simensen, T., R. Halvorsen, and L. Erikstad. 2018. “Methods for Landscape Characterisation and Mapping: A Systematic Review.” Land Use Policy 75 (October 2017): 557–569. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.04.022.

- Soini, K., E. Pouta, M. Salmiovirta, M. Uusitalo, and T. Kivinen. 2011. “Local Residents’ Perceptions of Energy Landscape: The Case of Transmission Lines.” Land Use Policy 28 (1): 294–305. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.06.009.

- Solecka, I. 2019. “The Use of Landscape Value Assessment in Spatial Planning and Sustainable Land Management — A Review.” Landscape Research 44 (8): 966–981. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2018.1520206.

- Soliva, R., and M. Hunziker. 2009. “How Do Biodiversity and Conservation Values Relate to Landscape Preferences? A Case Study from the Swiss Alps.” Biodiversity and Conservation 18 (9): 2483–2507. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9603-9.

- Sowińska-Świerkosz, B. N., and T. J. Chmielewski. 2016. “A New Approach to the Identification of Landscape Quality Objectives (Lqos) as A Set of Indicators.” Journal of Environmental Management 184: 596–608. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.10.016.

- Strumse, E. 1996. “Demographic Differences in the Visual Preferences for Agrarian Landscapes in Western Norway.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 16 (1): 17–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80219-1.