Abstract

In the autumn of 2019, Brown University hosted a major exhibition by the world renowned Haitian, Miami-based artist Edouard Duval-Carrié (b. 1954), curated by Brown’s Professor of Humanities and Africana Studies, specialist on Haitian history and art, Anthony Bogues. The title was ‘The Art of Embedded Histories'. As the title of the exhibition indicates, and as even a cursory look at this work could show, Duval-Carrié’s practice and output speak to material and visual culture specialists, and to anthropologists and archaeologists of art, as well as to art historians and scholars of postcolonialism. In this conversation, we engage with both the artist and the curator. Edouard Duval-Carrié deserves to be known more widely amongst material culture specialists, and we hope that the fascinating dialogue that follows will contribute to this.

Introduction

YH In the autumn of 2019, Brown University hosted a major exhibition by the world renowned Haitian, Miami-based artist Edouard Duval-Carrié (b. 1954), curated by Brown’s Professor of Africana Studies, specialist on Haitian history and art, as well as curator, Anthony Bogues (cf. Bogues Citation2018). The title was ‘The Art of Embedded Histories', it occupied two separate galleries in close proximity (the Cohen Gallery, and the gallery of the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice), and included both, very recent (2019) work by the artist, as well as some older, well recognized pieces and assemblages. As the title of the exhibition indicates, and as even a cursory look at this work could show, Duval-Carrié’s practice and output speak to material and visual culture specialists, and to anthropologists and archaeologists of art, as well as to art historians and scholars of postcolonialism.

But perhaps ‘speaks’ is the wrong verb here. These works act upon us in a non-verbal way, they are sensorially affective and captivating. We felt enchanted or even ‘entrapped' by them, to evoke an article in which Alfred Gell encourages us to see artworks as traps (Gell Citation1996). There are many reasons for it, Haiti, for a start: this is a country that was established as an independent nation-state after a revolution which was at the same time an anti-colonial and an anti-slavery one, a major, successful insurrection of enslaved people which reshaped the modern world in both the Americas and in Europe. The event was declared by C. L. R. James (Citation1989, ix) ‘the only successful slave revolt in history', a statement included in the preface of one of the most important texts of anti-colonial struggle, The Black Jacobins which narrates the story.

For me in particular, the Haitian revolution is of much interest for the additional reason of its connection to my region of study, Greece. I am referring to the impact of Haitian revolution upon people who were active in the Greek Revolution, or what is best known as the early nineteenth century Greek War of Independence, which led to the formation of the modern Greek nation-state, a connection that remains largely unexplored. Indeed, black Haiti is considered the first country to informally recognize Greece as an independent nation-state through a response letter by its president to a group of ‘citizens of Greece' who were requesting help, sent in January 1822 (cf. Sideris and Konsta Citation2005). Alongside these associations, Haiti has been a key reference in discussions on the politics of history and heritage, thanks to a range of inspired and inspiring writings, most notably by Michel-Rolph Trouillot (Citation2015), a scholar for whom ‘history is always material', as Carby put it (Citation2015, xii).

Moreover, Duval-Carrié’s specific ways of engaging with materials and substances from paper to aluminum, plexiglass and resin, and the diversity of his practice of assembling and sculpting, as well painting, engraving and embedding (on which more below) make him of particular interest to the scholars of material culture. But it is his hands-on dialogue with both the history of Haiti and of the Caribbean in general, with trans-Atlantic slave trade, with alternative ontologies, and with the Vodou material religious beliefs and practices from West Africa to the Caribbean, that make him a fascinating interlocutor, and his work a source of inspiration and reflection for cultural historians, anthropologists, archaeologists, and other material culture specialists.

From this extremely rich repertoire, I should mention briefly a couple of thematic threads, to be explored further below, which make Duval-Carrié’s work of special interest for its topicality and contemporary resonances. The first is the racialized histories of global capitalist modernity, histories in which Haiti and its past – which is always present – is central. I am writing these lines in the summer of 2020, based in the USA, in the midst of a popular revolt spearheaded by the Black Lives Matter movement, and for which the ongoing histories of race are central. A key question that seems to engage many people and groups, from street activists to art and museum professionals is, what does it mean to decolonize both the present and the past? Potential answers to this question are more performed and materialized than uttered, and in this contemporary political theatre, Haiti and Duval-Carrié’s work have a lot to offer.

The second is forced-undocumented migration and mobility in the modern era. Some of us would claim that we have entered a new nomadic age (see Hamilakis Citation2018), the material dimensions of which need serious and sustained attention. Earlier episodes of forced migration, and especially the mass trans-Atlantic transport of enslaved people from the sixteenth century onwards, despite its considerable differences with recent forced and undocumented mobility, will need to be part of our migration discussion, with colonial, racialized modernity and its geopolitics as the unifying frame. The legacy of slavery but also contemporary migration loom large in Duval-Carrié’s work. Finally, his paintings of human-tree figures or an engraving on plexiglass called Burning Amazon (2019), showing a human-like female figure in the midst of flames, evoke not only our contemporary reflections on alternative, post-humanist ontologies but also the concerns over human and nonhuman life, at times of climate emergency.

RGC As an archaeologist who works on slavery and the legacies of colonialism in contemporary western societies, I am often confronted by the limitations of the archive. The design and architecture of plantations and its coeval representations are products of the planter’s hegemony across space and time. Archaeology provides a narrow window into the lives of the enslaved and of self-emancipated communities, by revealing certain things, practices, or events that would otherwise remain absent from the historical record.

Yet, documentation practices done by archaeologists always rely on a visual regime that was put forward by extractivist practices, particularly those grounded in slavery. They are part of what Nicholas Mirzoeff (Citation2011, 48–76) has called the plantation’s complex of visuality. More than a structure of perception and interpretation, visuality is a power strategy and the set of technologies that define social and political boundaries in every historical context. Technical drawing, photography, and accounting are media that were developed within the plantation order. They objectify the world and testify to its possession, but also index social hierarchies and condense experience in ways akin to the management of labor exploitation or racial discrimination (see Mirzoeff Citation2011). The limitations of the archive are doubled by the limitations set by archaeology as a disciplinary practice.

These sensorial and epistemological configurations are the product of colonial modernity, and they were materialized with certain costs. Epistemicide, or the obliteration of humanity’s cognitive diversity, is among their utmost consequences (see Santos Citation2014). In this context, how can we possibly circumvent a centuries-old, ongoing process of erasure?

In my work about the Paraíba Valley in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, I have tried to elude these limitations by examining the ways in which the plantation landscape was constructed and negotiated through multiple bodily senses (Coelho Citation2017). Despite the possibilities opened up by a sensorial approach within landscape archaeology, visuality is still central in western modernity. Our potential role as archaeologists is to contextualize practices of seeing and make a critique of representations that are produced or fed by the discipline. We will never be able to recreate the experience of our ancestors, but we can certainly imagine that it is possible to acknowledge and reinvent the sensorial scaffold that has been shaping the west for the past few centuries. What are we allowed to see? How do we want to look?

The answers to these questions require critical fabulation and a focus on epistemic justice; a future-oriented effort through which we can sort out the materials, words or images that we intend to carry with us (Hartman Citation2008; Azoulay Citation2019). Through his work, Edouard Duval-Carrié mobilizes the multi-temporal threads that connect experiences, events and memories that can help us find alternative ways to represent our critical efforts. It is a work of countervisuality in as much as it dissects images grafted from the planter’s imagination and reinvents them as critical tools (see Mirzoeff Citation2011).

Duval-Carrié defies the mechanisms of possession and hierarchy entailed by modernist representations: images such as Henri Christophe’s resonate with European royal portraiture. Yet, it is transmuted into the Vodou imaginary, while its plexiglass surface defies the sensorial limitations of paper, ink or oil paint. In Benin, Duval-Carrié’s sculptures were reappropriated and repurposed according to local intentions. The artist struggled to make sense of these events and reflects on the practices of authorship (see Pressley-Sanon Citation2013). With the series Memory Windows, he combined resin, paper and plastic creatures in three-dimensional representations of events that resonate across time, space, personal memories and the historical record. In sum, what Duval-Carrié is doing with his work is generating new archival material to discuss history, current politics, and the future.

Artists and archaeologists share the ability to intervene in the archives that sustain hegemonic narratives about the past (González-Ruibal Citation2019, 91–112). Duval-Carrié’s interventions are an attempt at decolonizing the visual archive in which western modernity is grounded. With his work, he invites us to question today’s visuality, and push forward a new way of seeing; one that acknowledges alternative archives and diversifies the canon of works, images and ideas that populate our disciplinary canons. In order to do so, it is likely that we archaeologists have to generate new material and new ways of representing what we do. Regardless of how we do it, we should ask first: what world do we want to see?

These are some of the reasons that prompted us to have a conversation with the artist and with a key scholar and curator of his work. Edouard Duval-Carrié deserves to be known more widely amongst material culture specialists, and we hope that the fascinating dialogue that follows will contribute to this.

Embedded histories and the specter of the first Black republic

RGC As archaeologists, we think about how people and social life are embedded in the material world, and how objects are not representations but active agents. The work we do is constantly driven by a universe of expectations, relations, and particular forms of imagination framed by archaeological sites and artifacts. This is also the case with many artists. What are the images and objects that set your work in motion?

EDC Well, I want to tell you the story on where it's all started from. It started when Baby Doc (Jean-Claude Duvalier, who was president of Haiti from 1971 until 1986) fell. There was this flurry of excitement, of course, and I was there. And also there was an onslaught of artists and whomever, and they were painting everywhere in Port-au-Prince. I mean, there was not a wall then that did not have a very large painting. And as I started looking at them, I had a friend there who went and photographed them systematically, and he made a book in the end. I accompanied him because it was difficult. He didn't know where he was. So we were looking at all these things and I started looking at these images, some of which I had not seen before. And I said, where did they get them from? So I started literally looking at every book on visual history, especially of the Haitian Revolution, and realized that two hundred years later, suddenly, all these images from that time are springing up. Not everybody in Port-au-Prince had access to antiquarian books. So I looked, and there were maybe three or four of those images that were literally reminiscent of images from Marcus Rainsford’s An Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti (Citation1805) which is a very rare book that was published in England: the same context, same kind of imagery, but with modern characters in it. One of the images was this hill filled with posts and there were people hanging from them. I had never seen it before until I consulted the book. And I said, well, how did they know about it? That’s not in any repertoire of locally made history books in Haiti. How come this particular image surfaces in Port-au-Prince? So I tried to go back to see who had done it, and ask how did they get that image? I started realizing that there are things that people either remember or somebody had seen or told them about it. And that particular image is not being used in any reference book. So, I started looking to see where all these images come from. I realized that there is a direct connection, somehow; either they know about it or it has suffused through time.

It was very interesting to see how these images form part of the psyche of Haitians. Very peculiar, in particular, because in the Marcus Rainford case, what he was trying to do was to show how the British and the Haitians and the French were treating the situation. It was literally the only image or one of the few images produced in England, concerning the Haitian Revolution. And it was like the British fighting the French and the French being fought by the Haitians, and vice versa. So that is a group of images that I've always found very strange because they were depicting an international confrontation on the soil of Haiti. From then on, that stuck into my mind. There are core images of historical nature that are part of the whole island's psyche, somehow. And people read them carefully. They knew what they were, not what was being discussed. I mean, Haiti can see pretty wild things, people burning, there was the necklacing (execution by forcing a rubber tire filled with petrol around a victim's chest and arms, and setting it on fire), but never that particular image.

From that moment on, I've been looking at these historical images to see which ones have been adopted. For example, there's nothing really left of the American occupation, between July 1915 and August 1934, in the minds of Haitians. Yes, they know it existed; yes, they have the ultimate image of that, which is the 1948 painting of Haitian painter Philomé Obin. I could see it recurring once in a while. I mean ‘The Crucifixion of Charlemagne Péralte for Freedom' which was based on an anonymous, 1919 photo by a US marine. Péralte is a character who became important during the US occupation, a Haitian nationalist leader who led a revolt against the occupation by the USA. As you know, he headed a guerrilla group called the Cacos. So, I'm looking at all these things and I'm fascinated that people just would look at it and would know exactly what was happening.

YH So, you've become an archaeologist of images, tracing their material and visual genealogies and their temporal resonances?

EDC Yes. That's what I have become!

YH That's really interesting. Do they incorporate any monuments, such as the ones you have painted, for example the Sans-Souci palace?

EDC Yes, they do. I mean, King Henry's period (1811–1820) when some of these monuments were constructed, was a very important element in it. But to me, it's like trying to create this visual documentary of a nation. Now that I'm in the United States, I'm finding things that are also pertinent to that whole thing and also stories that are hidden, that are so evidently part of that whole configuration. So you have the connection with Louisiana. And now suddenly, I went into the north of Florida and the same things happen there. There's all sort of things – I mean, the French émigrés from Haiti and who did they bring with them. People would say that they were about 1000, 2000. But everybody forgets to say that the real wealth was in human beings, in enslaved people. So they were finding places where they could take their population, I mean, their slaves. So when they say to you that 1000, 2000 people showed up in New Orleans, they forget to tell you that there were more than 10,000 slaves accompanying them. And these are stories that people usually do not talk about.

YH I would like to ask Tony about the concept of embedded histories, which is in the title of the exhibition here at Brown University. Could you tell us why did you choose this title and what do you mean by that?

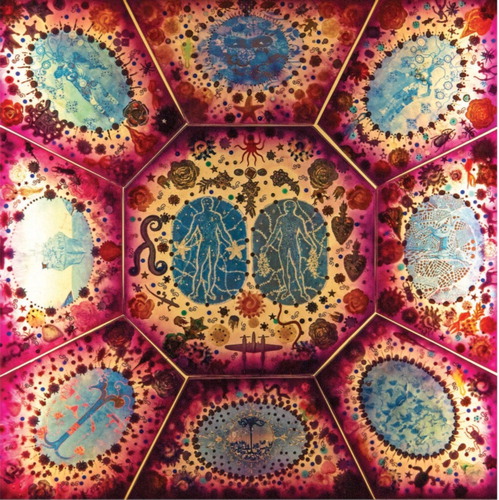

AB Well, it's really very simple: that if you look at some of Edouard’s work, for example in the Memory Windows series ( and ), then you will see that embedded within the resin are more objects and images that he himself has used in some of his other works. But there are also historical images embedded within that work. So, what came to me was that what you are looking at is an artist who is practicing the technique of embeddedment by putting things in resin, in this kaleidoscopic manner. And he is doing that both with his own earlier works, as well as with images from the past, taken from books. Therefore, the title Embedded History flowed from this perspective. If you think through the portrait of Henri Christophe (), you will notice that the artist is doing a different kind of embeddedment. He’s trying to think about Henri Christophe (1767–1820), a key leader of Haitian revolution and monarch, in a way that is much different from the way in which colonials thought about Henri Christophe. He’s trying to correct the stereotypes. And therefore, trying to do a visual history of Haiti that is part of the ways in which Haitian art works, with its visual histories of the revolutionary leadership. Henri Christophe as a work is a different kind of embeddedment, an embeddedment within Haitian history by taking it out of the colonial gaze. So for me, embeddedment and things being embedded, both work within some kind of tradition of visual historical culture, what we can call the Historical School of Haitian painting, one which has many currents.

Figure 1. Edouard Duval-Carrié, Memory Window #2, 2017. Mixed media embedded in resin, 58 × 58 in. Reproduced with the artist’s permission.

Figure 2. Edouard Duval-Carrié, Memory Window #9, 2018. Mixed media embedded in resin, 58 × 58 in. Reproduced with the artist’s permission.

Figure 3. Edouard Duval-Carrié, Henry Christophe, ou la derniere danse Taino, 2019. Engraving on plexiglass, 84 × 84 in. Reproduced with the artist’s permission.

YH When we look at the series Memory Windows, we are reminded of amber, and of insects or other creatures trapped in it, and we conjure up a geological idea of capturing a moment from history or of preserving intact a living organism in a specific matrix, in this case inside amber (). How are you using the concept of living history to describe Edouard’s work? Is it similar to embedded history or is it different?

AB To the question of living history: the concept emerged as I was writing an essay on the relationship of Edouard’s work to history. He was doing a solo show at the University of Florida and as I looked at the new pieces of the show, it became clear to me that he is an artist who was thinking and working with history in specific ways. The argument is really this: that he is, in my view, not a visual historian, which is what I've written before, but he is trying instead to think about the work of history. So he is painting history. He is reworking history, whether it is in his visual commentary on the work of the Hudson School, or in other places. He is repainting some of the paintings of earlier artists, and putting American gunships and Disney characters in the middle of it all; he is trying to think about racial slavery and its afterlives in his painting on cotton, and then thinking and working through the meanings of migration in works such as the Memory Windows series. As well when you look at his work on ships, which was done at the Colorado Fine Arts Museum, you see someone who was preoccupied with history, but not history as something that's just in the past, but the ways in which actually history lives with us today. The idea of living history was that he is, in my view, an artist that uses history to make a critique of history as well as the present. His work is not about the past which you can capture, and access faithfully and truthfully. He has taken particular moments and fragments – and fragments is the better word – of history, and has reworked them to critique the present. One has to add that the work is deeply rooted in the Haitian culture, the Haitian history of visual culture, the Haitian literary tradition, and the Haitian cosmology of Vodou. And in all those four things, the work of memory is important.

EDC I was here, at Brown, doing this project with the students. And every time, I let them do whatever they wanted to because you just give them an idea and see how they can develop it, and juxtapose different times. You know, the recent with the ancient and see if there is a correlating line or what interests them really, what is pertinent to them. I did that three times by now. I did it once with students from high school to celebrate the bicentennial of Haiti in Miami. The second time I did it I was at Duke University, where they had all these scholars united under the banner of the Haiti Lab.

RGC What kind of connections did the students draw through their art practice?

EDC The project was called ‘Haiti Embedded in Amber'. And indeed, they came up with things that were linked to their fields of studies, from architecture to social sciences and medicine. It gives you an idea of the state of research on Haiti at the time. And I did a project in Grinnell College, in the middle of nowhere, in Iowa. And I asked them the question: is there a connection with Haiti here? And I got about 25 of those students and professors working on this question. They showed that there was a continuation of history either through the Mississippi all the way up there, or through the abolitionists and the anti-slavery movement. And one finds out about all of these histories that are somehow hidden and not really well known, at least to the lay public and to myself.

AB So, how do people remember stuff and think about stuff? If you think about the archives of the Haitian Revolution, one of them is actual Vodou songs. And those songs have a long history, and those songs are done and redone time and again. They change a little bit, and so on. Vodou is a religion that has no text, there's no Quran, there's no Bible, it is an oral religion; as a result, the work of memory becomes important in the transformation of the elements of its cosmology. When Edouard talked at the beginning about the Marcus Rainford images in that particular book, which is a remarkable book on the Haitian Revolution, what I am reminded of is, okay, who may have seen that?

EDC Right. That's what I'm asking myself.

AB And then, actually, reproduce it and tell other people about it, and then get it repainted. And once it gets repeated once or twice, people pick it up and rework it. So it becomes a memory. So how then do you tell the history of the Haitian Revolution if you are in the present? You tell it by researching official archives of the French Bibliothéque Nationale, the John Carter Brown at Brown University, Boston Library, the British Library. But you also have to tell it in the way in which ordinary people may understand it themselves. And that's what I think Edouard is trying to do: he’s trying to tell a story of Haiti and indeed of the Caribbean, from a standpoint in which he is deeply rooted, in the actual culture and cosmology of the places that he is trying to work through. So that's why you get living history. History and memory are jostling together all the time into work, and sometimes you're not sure, what is memory? And then what is history?

YH I want to emphasize what you said, Tony, on the work of memory. You are evoking an idea of memory as something which is not passive, which just happens (as in the notion of involuntary memory) but as a process that needs work, such as bringing together the things you collect, putting them next to each other or reworking and modifying them, creating a kind of visual/material narrative history. But these new objects in their turn, work themselves upon humans and upon the material world, they perform memory work on their own. This is one thing I want to emphasize. The other is about temporality. It seems that Edouard’s work is not just a living history. It's also a certain materialized temporality which is very different from linear temporality. Edouard’s sense of temporality is about duration and coexistence, rather than linearity and succession: all of these moments are here now and coexist, and they are not a part of a past that’s gone, points in time along a linear sequence. That’s another way of describing this work as living history, a sense of temporality that evokes the philosophical writings of Henri Bergson and Gilles Deleuze.

EDC The point is that all of these stories are the core part of how one perceives and how we construct reality. There is a lot of turmoil in Haiti right now. We want to get rid of the president. People are saying things like ‘we are not slaves anymore.' They have been saying these words, and I can imagine the same happened two centuries ago. And interlocutors immediately realize that they did have to be transported back centuries ago. So the question then is, have they realized that not that much has changed since then? Because they've somehow left it to all these social experiments that Haiti had been going through. These were experiments that they were part of, that they allowed, that they supported, that they participated in. And two centuries later, they are nowhere.

So these are the kind of questions I have, as I realize that this nation-building process has failed. And then where do we start again? And how do we tell that, and how can I explain it visually to these people that this is them, that they are part of this history? I look at this process very carefully and try to figure out what went wrong. Well, I mean, that's what people have to figure out. Even me, I have to figure it out. It's been an ongoing process of trial and error. I mean, you realize that two centuries have passed, and you realize that everybody is still at the same moment when they decided to take the onslaught against the French. So we have to ask, what next?

AB Well, I think that what might be useful is to think about Haiti as not just Haiti, but the island of Hispaniola. To think that this was the very first site of the colonial European conquest in the Americas, and to remember that after colonization it was split between Spain and France. The first battles against European colonial conquest happened there. You are looking at a locality in which the first conquest of the New World happened, and there's always been resistance to that. Not every day obviously, but there's always been resistance there. What you are seeing is that this country is really deeply embedded in a struggle against colonialism and against the West. That struggle has been enormously difficult. We tend to forget that Haiti had to pay reparations to France, right up until the 1930s, in a so-called exchange recognition. Imagine that you’re free – I free myself and keep myself free from you. And then you come back to me and say: you now have to pay me. And I have to pay you for the land. I have to pay you for me as a person as well, because since racial slavery is about the property and ownership, then I'm also property. Then think about the history of the island after the payment, and how the United States intervened. I'm not saying that there are no things that are wrong in Haiti; that's not the point I'm making. I'm talking about the relationship between the external forces and the internal forces. What are some of the internal problems?

This is the way I explain it to people: If I lived in Haiti in 1805, for example, and I looked around me and I saw that there were slave plantations everywhere, north, south, east, west, I would have to have an argument with myself: do I have democracy? Or do I have an army that can defend me? Because these people are going to attack me in some way. The revolutionaries in the eighteenth–ninteenth centuries decided to have an army. The problem with having revolutionary armed militias run the country is that you militarize the country, even with the best will in the world. There is a logic to having the military running a country, even if the people running it are good people in their heads …

YH A logic of militarization.

AB Then you have a logic of militarization, plus the external things that create tensions in Haiti. Michel-Rolph Trouillot put this very well in this book called State Against Nation (Citation2000), in which he argues that what you get through the historical process of the militarization is a certain kind of government and of politics that is based upon practices of terror and authoritarianism. But he says that what you then get, is the ordinary Haitian withdrawing from that. So you get a nation of peasants, and of ordinary people living in the countryside, doing whatever they're doing, trying to live. And then you get the authoritarian people … and the military people. You get those two things. What I think Edouard is talking about is that at various moments, what you get is that the actual nation moves against the state. In other words, the actual nation says: listen, enough. We are not slaves trying to reclaim a nation. A nation that has a political discourse in 2020 that begins with ‘we are not slaves' shows that there is a historical memory, a ground from which people begin, a self-identification as the people who actually created the first Black republic. That is unprecedented. It’s unprecedented in so many ways that we haven't quite understood it. Because if you try to think about it, what is it that these people were raising in the nineteenth century? They are raising the question of Black sovereignty. How was that possible, in the anti-Black racist world of the nineteenth century? How could you have these people talking about Black sovereignty? When people thought that the nation-state is becoming important in Europe, there are these people saying: no, can we have a Black Republic? It is a kind of impossibility. And therefore, that kind of impossibility, in my view, always resonates within the West. And everything had to be done to tarnish it, including painting the Haitian stereotype of a country of superstition and zombies.

EDC The West has built a whole aura around it.

AB The West has to do that because you have to keep alive the idea that Black sovereignty is not possible.

Atlantic connections

RGC The Haitian revolution shook and changed the Atlantic world, and it continues to resonate in contemporary struggles for social justice. I wonder how this global legacy affected your work. There is this moment in your career, in 1993, when you went to the ‘Ouidah ‘92' festival in Ouidah, Benin, where you presented some of your work. At some point, you realized that it had been appropriated and re-signified in different terms. How did you see this at the time, and how do you describe this moment in your own career?

EDC I was invited to participate in an art project. I've looked at Vodou, I studied the various forms of it. And then I got there and I realized that I am at the heart of African Vodou. I was in the seat of the Vodou, as practiced in West Africa. Ouidah is the center of that. And suddenly, I realized that there is this very organized religious system with a head – I mean, to me he was literally the Vodou Pope, and he reunited, in West Africa, whomever he felt needed to be there because that was the point. All the dignitaries from Nigeria, from Togo, from Mali, and all these saintly people showed up, in their caravans, and some of them even in their Mercedes Benz. But they were all there, and they came to pay homage to him because he was somehow self-aggrandizing for that group. And here I was, you know, literally the only artist kid who came from Haiti.

YH Why did they invite you in the first place?

EDC I was the easiest. I was in Paris at the time. I was interested in Vodou, and they said, ‘send him down there!' So here I was. I arrived early because I wanted to do an installation, and there was nobody there yet. I asked if there was a museum. There was no museum. I ended up with the Dagbo Hou Non, the ‘Vodou Pope'. So he decided to whitewash his whole temple, which had really old and very beautiful paintings. And then he took my book, the catalog that I had with me, and said: ‘I want this painting here. I want … ' I said, are you mad? This is not the way that it's supposed to work! So anyway, a Cuban artist showed up, and then a Brazilian. So I explained to them: listen, we have 15 days to repaint this chap's temple for it to look like something because he just whitewashed it, as you can see. We all worked, and in the end, he allowed me to do my installation, which at the beginning he decided was not really Vodou because it had antennas. It’s a long story. They liked the idea, and I had no idea why they liked it. They allowed me to put it in. And I don't know what he said to everybody. Everybody walked into the temple and my installation was there and everybody bowed and poured eggs on my pieces and stuff. So I'm just like, okay, that's fine. What can I do? And when the thing was dying down, I decided to pick up my piece and they were gone. The Dagbo Hou Non said ‘thank you very much, we like it'. It’s a year later that I found out what was in his mind. What he wanted was to turn Benin into a center of Vodou, but also to bring tourists, African-American tourists. He even said Michael Jackson was coming. I said, are you mad? Michael Jackson? ‘But he's Vodou! Just look at him!'.

Then I said, we have to go to the beach. I wanted to make sure that I put my antennas up so that all the spirits that come back to Africa find their way to Benin. The Dagbo Hou Non just loved the idea. So one day, five or ten years later, somebody brought a video they had made from the ceremonies that were happening at that place where I had asked them to do my sculptures. So they were putting all these things up, and then in the middle of it, I see my sculptures! They were half broken because there were made in plastic but they were there! And it was full of airplanes. The whole idea was to create a temple which would have attracted tourists to Benin. I mean, it was just fascinating. And that's the way it happened.

RGC But there is also a story about a Vodou temple in Haiti, where you found a poster of one of your exhibitions hanging from the wall.

EDC It's not just one. My first big exhibit was at Davenport (in Iowa, at the Figge Art Museum), and the painting that they had bought was one of my first big purchases. They had made a lot of posters which they sent to Haiti. The exhibit’s posters were distributed and, for some reason, some of these posters, the largest posters, were put in temples. Not only one, but I witnessed it in one of them. I said: what is that doing there? He said, ‘oh, that's Ogun’.Footnote1 I said, you know, I made it. ‘You didn't make that. You could not have made that!' Okay, fine. I said, that's my name under there. Do you see my name? That's me. They're just like, ‘oh you know about Vodou and stuff like that!'

YH How do you feel about that?

EDC I feel that I'm right where I'm supposed to be. And I find it very interesting that these kinds of things can happen because they read the work. Somehow, I must have caught the essence of it. And it happened in Africa as well, because in Benin I had painted the temple of that chap, and all the others – he was not the only one. He was probably the most important. But there were others. And I had three or four ladies come to me with bags of money. So I said, oh, my God, I can be an artist in West Africa. I can survive here if I stay! So, you know, that was even more fascinating than that whole story.

YH What happened to that Benin work, afterwards?

EDC I don't know. It's still there. They repaint it and refresh it, according to friends of mine who have been there. I'm not bitter that they refresh it. I have a portrait of the Dagbo Hou Non with the painting behind. It's quite nice.

RGC In Haiti and in the context of Vodou the relationships between national identity, artistic practice and notions of authorship are not as central as they are elsewhere in the West. The boundaries between contemporary art practices and spirituality are not necessarily relevant.

EDC When you go to Haiti, you realize that spirituality is where it all comes from, and you realize that in West Africa as well. The notion of country does not really exist as we know it. I mean, Ouidah in Benin is considered a major spiritual center. And one day they'll have to reorganize themselves and think of it in those terms. You should have seen who came to visit that festival and how far they came from. There was even some character from Cameroon. And when you realize from where this guy took his car and drove all the way up, or flew in or whatever, to be there and pay homage to this Dagbo Hou Non. And even the president was there, and you realize that this is an organized system that is recognized and powerful. And he was allowed to do that because he had cured the president. I mean, there was this president in the 1990s, Nicéphore Soglo, who fell ill. He was interesting, intelligent. So one day the previous president decides to leave. He just packed up and said, ‘I'm returning to my village'. And there was a vacuum of power and so the French filled it in with this Nicéphore Soglo who, however, became deadly ill, and they had to bring him to France. This was at the height of AIDS epidemic. And he was cured by the Dagbo Hou Non. So when the president asked, ‘OK, what should we do?’ the Dagbo Hou Non said, ‘I want to do a festival'. A festival organized around that whole Vodou thing. So it was half political, half cultural. It was a very interesting moment. And I realized that Vodou is a lot bigger than people think it is. Even for me, I mean. And when I went in, I realized as well that there were people from all those Caribbean islands, Cuba, and there was a few Martinicans. The Dagbo Hou Non wanted to present himself as an international kind of phenomenon, you know, like a Vodou phenomenon. I think he could do it! I mean, it could be done, because the network is all over. There were people from Brazil, a lot of them, a lot of emissaries from Brazil.

RGC What fascinates me even more in these stories that you are telling is that it seems that to them you are not just an artist. Am I right?

EDC Oh, no, I was not an artist. I mean, to them, no. Because you know, I said, I'm a good artist, you see, I have a catalog. And to them, it was the objects and their meaning which were important. The idea for me was to plant something. I had looked at what was produced there, and I decided to make the antennas as the central idea, like I had seen happening in this festival in Haiti. I only saw it once. I was returning from a far-away place, and I saw a really big gathering of people. And it was this officiating mambo, this Vodou priestess, and her name was Nana. She had organized this thing and she was sending spirits back to Africa. And when you got to this place, you could buy your passport. So there were little stands. Thousands of dollars were made that day. People would buy a passport, and then they would take the whole lot to her and she would put a stamp on them. She had a little stamp that she would put on each passport and then she would ship all the spirits back.

YH And you needed a passport for that.

EDC You needed a passport. So to me, that was so amazing. And I was in France by then, and I had just come back to visit my house. So when they invited me to do this thing in Benin, I said they needed antennas so that the spirits can find their way back to Africa because they're going to get lost in the ocean. So I got totally into this whole thing and I went back with the idea that I saw this in Haiti, that they're sending all these spirits back. I decided that we have to put antennas in Ouidah so that they could find their way to the real place. When I showed these sculptures to the Dagbo Hou Non, he said, ‘Ah! They're like crosses!' I said, they're not crosses! I mean, of course, they just had the basic shape. In the end, that's what I installed and I don't know what he told them, that they were like powerful gris-gris which is a Vodou amulet. And so, I got to the point that I had to give a talk at the School of Art in Cotonou, the largest city in Benin. So I went there and I was explaining to them what I was doing and how important it was because they had boycotted the whole thing. And I went after them to make sure that they would come. I explained that this is real, a South-South kind of thing, that this project started by some priest, that his religion is very peculiar as it accepts art. They responded that somebody went there and told them that there is only one cool thing there, some Vodou priest from somewhere abroad had installed something amazing and that everyone should go and see it. And I said, what you're talking about are my pieces.

YH Did they come at the end?

EDC They did. They came to check on the Haitian gris-gris.

RGC You’re taking us back and forth across the Atlantic. Perhaps it’s a good moment to ask you about your experience in South Africa. Could you tell us how that started?

EDC That’s fascinating because I often asked myself: what am I doing here? And what was fascinating is to realize that I was in a Black space, despite the fact that they are only 20 years, not even 20 years away from apartheid. Everybody that I spoke to unless they are a lot younger than me, was involved in that system, whether white or black. And it's very difficult. They talk about it but this situation is very fluid, and I'm probably there as a cautionary tale. Is that the way you see it, Tony?

AB No, I think the link to South Africa has a long history that involves Cape Town and that city’s national museum. Edouard and I were in a discussion after 2011 about the reframing of Haitian art. We agreed we needed to do an exhibition. It's art, so that's what you need to do. And so I was in Cape Town as a visiting professor at the University of Cape Town Museum, and met an artist and curator, Raison Nadioo, who was the first Black director of the gallery. He and I had a long discussion. We talked about Haitian art and the possibilities of bringing Haitian art to South Africa, and why was that important. We agreed, and we tried to put it together. Putting that project together, though, had huge financial costs. Edouard came down to South Africa and saw the space we agreed about; we had discussed how to use a national gallery. But it never materialized. But also, quite frankly, he ran into difficulties as the first Black director because he was trying to deal with certain things that a lot of people call afterlives of apartheid, things that were still institutionally in place. And so the director actually resigned. He left the job and sued them for certain things. And so, when my look shifted from Cape Town to Johannesburg, I still had that exhibition in mind. I spoke to the associate curator of art and architecture at the University of Johannesburg and they have a gallery and they said, ‘yes’. Importantly, we also got the Johannesburg Art Gallery interested. There are not enough resources to do a big Haitian show, but they thought it was important to have Edouard to do a solo show there. And so, part of this was to give him a residency, and then we would do an exhibition. However, the exhibition has been stalled because of COVID-19, and once the pandemic is over we will resume the process of making that show a reality. Tentatively, the working title of the show is Marvelous Real. So that move to South Africa is really about trying to reframe Haitian art, but not necessarily from Paris or New York, but actually do it from South Africa.

YH Edouard, how long did you stay there?

EDC Two months. Well, one month and a half. Long enough to realize how complicated the situation is. It’s interesting and vibrant at the same time, though. It’s a very wealthy nation. They do have potential, that’s the thing. Plus they have a tradition which stems from the anti-apartheid movement of creating all these quick visuals, you know, like with printing. That’s what informs the art.

YH Stencil tradition, or?

EDC Yes, stencils and linocuts. They're not into refining anything and they focus on disseminating. It’s impressive and informed even the work by people like William Kentridge.

YH And you worked on different forms and media while you were there.

EDC I tried everything that I could. And I wish I had stayed longer to really get into the whole thing. But I had too many preconceived ideas of what I should be doing. I did manage to create quite a corpus of work, which is interesting, which has yet to be presented properly.

Migrations and hybridity

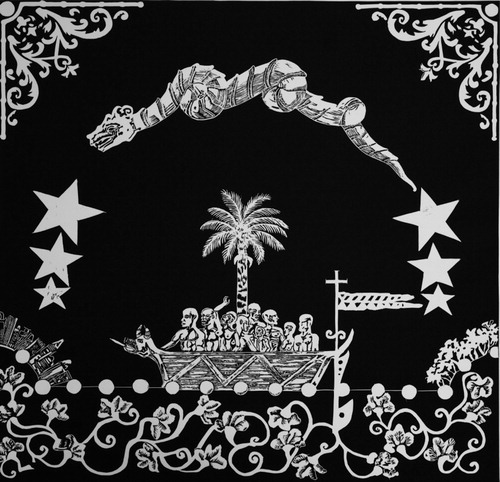

YH Can we just go back to your work on migration? I see migration as an undercurrent running through many of the topics we've been discussing, as a constant within history thought of as a living process. Within a multi-temporal understanding of history, I see connections between contemporary, undocumented migration from the Global South and slavery. Some of us would even say that contemporary migration constitutes the most recent episode in the long duration of colonial, racialized modernity and racialized capitalism, with slavery as its key, originary episode. And I am thinking of the figure of the ship or boat in your work (), the vessel that transported enslaved people, but also the boats that people from the Global South use today to cross into the European Union or to Australia and to the other countries of the Global North.

Figure 4. Edouard Duval-Carrié, Migration, 2019. Engraving on plexiglass, 48 × 48 in. Reproduced with the artist’s permission.

EDC This has been standard in my work since the beginning, and particularly since I arrived in Miami, after living in France for a while. I got the newspaper a few days after I arrived in Miami, and there was a study by some local journalists. How much does it cost for a boat like this to arrive from Haiti? These guys went to Haiti and followed the whole process. And they learned that the creators spent so much on wood, they spent so much on cloth … so there was like a spreadsheet of how much these things cost. And then I was looking at it and there was one item the most expensive, which was a Vodou calabash. I mean, that was two thousand five hundred dollars that they had to pay the Vodou priest to guarantee that the boat would get safely there. I was flabbergasted. So the Vodou gods were accompanying these people, no matter what creed they were. Of course, they were not all Vodoisants. You have to remember that 90 percent of Haitians are Catholic. But they are very Cartesian, if you wish; they will not put all their eggs into one basket. But two thousand five hundred dollars went to the Vodou priest that created that little calabash.

YH Do they construct the boats themselves?

EDC Oh, the Haitians are the best with the boats. It’s uncanny and unbelievable. I went to this character who collected what the Cubans were making as ships to go to the United States, and these people are into suicide trips! Meanwhile, Haitian boats are really well done. They must have had some knowledge from Africa, how to make them. Plus, the first onslaught of French colonizers was by Breton fishermen. And that’s the style of boats they use in Brittany, that's the way they build their boats. I've heard them say ‘No, that's the way you're supposed to build'. I said there are different ways. And they said, ‘that's the way'. So they are done in that particular tradition. And they're seaworthy. Of course, they put too many people in them, and they sink. But you should see what they do in Cuba. I mean, I've seen things like metal chassis of big trucks to which they tie the foams from a TV box so they can float. Of course, they don't get three meters far.

YH Is there someone collecting that kind of stuff?

EDC I don't know where they've put it, but I went to a place where this character had collected maybe two dozen boats. And they were all different. There was no knowledge of anything. I mean, some of them were made of wrapped tires.

RGC It's interesting. Ship-making is one of the most radical interventions in post-colonial Haiti because after the independence, Haitians were not allowed to build large ships as per agreement with the British and the French, right?

EDC They did try to enforce that, but in the nineteenth century, there was this tradition where Haiti provided what is called a vive, provisions like bananas to all of the islands, all the way down to Curaçao. So Haiti has always had this merchant marine, which was not important enough for it to be stopped. But the United States is still trying to curtail them by forcing onto them to have a GPS system and stuff like that. So, of course, these people know their sea and they know how to do it. So, until today there have been discussions in Haiti about whether they can make boats, or should bring them down, because they’re not seaworthy. Of course they are seaworthy, they've been doing it for a hundred years.

AB Another thing that you might try to remember is that Toussaint did have a plan to build boats to go to Africa to free the slaves. He began that, but then stopped it. Because it became very clear that if he did that, then trade with America would have become impossible. And he had to think about, ‘OK, France is over there, America is over here and I need to have trade. What do I do?' But there was a real discussion about that. In my view, if he was thinking about that, he was also thinking about the ships that brought people over, and what capacities they had to be able to build boats.

EDC And also, you have to realize that in Haiti, until the 1940s and 1950s, there were not many roads. You had to go on donkeys or take the boat to go around the island. So there is a knowledge of boat-making and boat-building.

YH You have also created very strong images of hybridity that involve humans and plants. Have you made them in relation to current events and processes, from climatic change to the destruction of the Amazon?

EDC We’re part of this world, part of this nature. We're no different. This is something that I basically started when this whole AIDS thing came up. How to live with disease, you understand it is a balance, but we're definitely not balanced these days. So we're going to see a lot more imbalances like that.

YH This last point allows us to start pulling together, by way of conclusion, some of the many threads we have developed in the course of our fruitful conversation. What you say about nature resonates with the attempts in many disciplines, including archaeology and anthropology, to explore different ontologies, alternative ways of being in the world, beyond the dominant western, anthropocentric canon. Your work, including your half-human, half-tree figures, speak to that anxiety. And as we are editing these lines in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, your phrase about living with the disease strikes a chord: living with the disease while, at the same time, learning to conceive of and live through life differently. But in our discussion, and mostly through your work, you offered us an oblique commentary on and a range of responses to contemporary struggles towards decolonizing artistic and scholarly practice. You have told us and showed us that engaging with matter, vibrant matter, striving to produce new material forms, and remaking canonical works, can bring to life the multi-temporality of experience but can also enliven history, make it palpable, sensorially affective and politically efficacious. You have also proved how important it is, in this specific moment, to give material expression to the link that connects contemporary migration with the histories of racialized slavery and with colonization. Finally, you have implied that in our decolonizing efforts we should demonstrate the interconnectedness of the Global South and the Global North, while at the same time striving to develop more South-South connections. Most importantly perhaps, you have intimated that Haiti and its histories will always be there to remind us of the unfulfilled promises, of alterative modernities beyond racialization, of the revolutions yet to come.

RGC We started by discussing how Edouard’s work was impacted by images and objects that were negotiated and circulated since his early years as an artist. He reassembled a constellation of books, wall paintings, photographs, and even boats that Haitians built to sail across the Caribbean. Like an archaeologist of images, he has been mediating the past through material and visual artefacts that often escape the communication boundaries set by our métier. A poster of Edouard’s first major show in the United States, for example, reappeared in a Vodou temple in Haiti where the image was re-signified as Ogun’s. This is a reminder of the powerful effects of Edouard’s work, which instigates us to connect fragments of multiple temporalities and opens new paths for our political imagination.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rui Gomes Coelho

Rui Gomes Coelho is a historical archaeologist who works on colonialism, decolonization, conflict, and resistance in Southern Europe and in the Atlantic World. He is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Archaeology, Durham University, UK and is also affiliated with the Centre for Archaeology at the University of Lisbon, Portugal. His interests are interdisciplinary and driven by a fascination with the sensorial constitution of alternative modernities, and with marginal communities who mobilize material culture against traditional approaches to heritage. Recent publications include the essay ‘An Archaeology of Decolonization: Imperial Intimacies in Contemporary Lisbon', published by the Journal of Social Archaeology (2019) and the essay ‘Heritage and the Visual Ecology of the Plantationocene' in the volume Heritage Ecologies edited by Torgeir Rinke Bangstad and Þóra Pétursdóttir (2021). He is currently focused on two community-based projects: the archaeology of slavery in Cacheu, Guinea-Bissau, and the archaeology of anti-fascist resistance in Croatia during the Second World War.

Yannis Hamilakis

Yannis Hamilakis is Joukowsky Family Professor of Archaeology and Professor of Modern Greek Studies at Brown University. He has researched and published on archaeology of the body and the senses, the politics of the past, decolonizing archaeology, archaeological ethnography, the photographic and the archaeological as collateral devices of modernity, and the materiality of contemporary migration. His books include The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece (2007); Archaeology and the Senses: Human Experience, Memory, and Affect (2013), Camera Kalaureia: An Archaeological Photo-ethnography (with Fotis Ifantidis; 2016); and the edited volume, The New Nomadic Age: Archaeologies of Forced and Undocumented Migration (2018). Archaeology, Nation, and Race: Confronting the Past, Decolonizing the Future in Greece and Israel (co-authored with Rafi Greenberg) will appear in 2022. He co-directs the Koutroulou Magoula Archaeology and Archaeological Ethnography Project which, amongst other things, engages with artistic practice as part of the excavation process. Since 2016 he has been exploring the materiality of contemporary migration on the border island of Lesvos. He has curated and co-curated a series of exhibitions at Brown University, most recently ‘Transient Matter: Assemblages of Migration in the Mediterranean’ which is currently on show at the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology (https://blogs.brown.edu/transientmatter/).

Notes

1 Ogun is an orisha (spirit) in Yoruba religion and West African Vodun. It has been venerated in African diasporic religions across the Americas, namely in Brazil, Cuba and Haiti. Ogun protects warriors and blacksmiths, and is known for being the orisha who opens and clears paths.

References

- Azoulay, A.A. 2019. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. New York: Verso.

- Bogues, A. 2018. “Making history and the work of memory in the art of Edouard Duval-Carrie”. In Decolonizing Refinement: Contemporary Pursuits in the Art of Edouard Duval-Carrié, edited by P. Neil, M. Carrasco and L. Wolff. Gainesville (FL): University Press of Florida.

- Carby, H. V. 2015. “Foreword.” In Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, edited by M.-R. Trouillot, xi–xiii. Boston: Beacon.

- Coelho, R.G. 2017. Sensorial Regime of “Second Slavery”: Landscape of Enslavement in the Paraíba Valley (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). PhD thesis, Binghamton University, USA.

- Gell, A. 1996. “Vogel’s net: Traps as Artworks and Artworks as Traps”. Journal of Material Culture 1(1): 15–38.

- González-Ruibal, A. 2019. An Archaeology of the Contemporary Era. London: Routledge.

- Hamilakis, Y. ed. 2018. The New Nomadic Age: Archaeologies of Forced and Undocumented Migration. Sheffield: Equinox.

- Hartman, S. 2008. “Venus in Two Acts”. Small Axe 26: 1–14.

- James, C.L.R. 1989. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. 2nd ed. London: Vintage.

- Mirzoeff, N. 2011. The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Pressley-Sanon, T. 2013. “Exile, Return, Ouidah, and Haiti: Vodun’s Workings on the Art of Edouard Duval-Carrié”. African Arts 46 (3): 40–53.

- Rainsford, M. 1805. An Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti. London: Albion Press.

- Santos, B.S. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Sideris, E.G. and A.A. Konsta. 2005. “A Letter from Jean-Pierre Boyer to Greek Revolutionaries”. Journal of Haitian Studies 11 (1): 167–171.

- Trouillot, M.-R. 2000. Haiti: State Against Nation. Origins and Legacy of Duvalierism. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Trouillot, M.-R. 2015. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon.