Abstract

The annual Pintores de África exhibitions, organised by Franco’s colonial administration in mid-twentieth-century Madrid, offered audiences a colourful feast of artistic representations of Spain’s colonial territories in Africa, and of Spain’s architectural legacy of al-Andalus. Foregrounding the ideological issues underpinning these exhibitions, this article evaluates the selection of artworks, the programme of events, exhibition catalogues, and reviews. Many writers discussed the artworks with reference to al-Andalus, echoing colonial propaganda. After Moroccan independence (1956), the exhibitions partly lost their purpose, but the memory of al-Andalus was repurposed by Moroccan cultural brokers for the fashioning of their post-colonial artistic identity. The last part of this article reveals the relations between the Painters of Africa exhibitions and the birth of the School of Tetouan. The article not only sheds light on the art, curation, and art writing that took place in the interstices between Spain and Morocco at the end of colonialism, but also illuminates the paradoxical processes underpinning the formation of artistic identity in post-independence northern Morocco. The case study is relevant to global perspectives in History of Art and refigures understandings of East–West relations with which we have become so familiar since Said’s Orientalism of 1978.

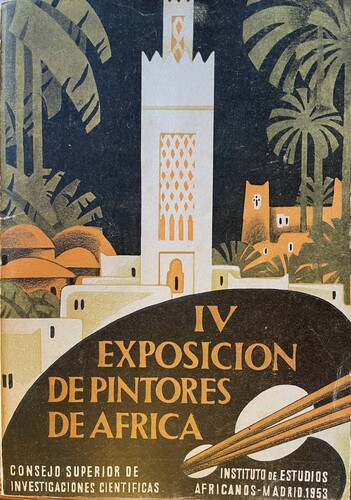

The Painters of Africa (Pintores de África) exhibitions, shown annually at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid from 1950 onwards, offered Spanish audiences a visual feast of artworks by Spanish and some Moroccan artists. On the one hand, the works represented the people and the urban and natural landscapes of Spain’s colonial territories, especially of the Protectorate of Morocco and, to a lesser extent, of West Africa. On the other hand, they focused on aspects of Spain’s Andalusí architectural legacy. Organised by Franco’s Dirección General de Marruecos y Colonias, in collaboration with the Instituto de Estudios Africanos of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), the exhibitions were open to Spanish and colonial artists to contribute and compete for art prizes. The shows were of considerable scale, accompanied by a dynamic programme of events, and well-attended. To ensure an afterlife of the exhibitions, the Instituto de Estudios Africanos also published catalogues after each exhibition. They included the list of exhibits, the prize-winners, illustrations, the texts of the speeches, the details of concerts and poetry readings delivered during the exhibitions, alongside reprints of reviews that had appeared in the press (). From 1955 onwards, with Moroccan independence looming, the catalogues became more modest publications, reduced to lists of works.

Figure 1. Cover of Cuarta exposición de pintores de Africa, Citation1953. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

Between 1957 until the independence of Spanish Guinea and the province of Ifni in 1969, the exhibitions were organised by the Dirección General de Plazas y Provincias Africanas. In 1971, the Dirección General de Promoción de Sahara organised the final exhibition, which was still of a considerable size with 116 works of art, focusing on the same themes established with the first exhibition.Footnote1 The nature and the importance of these later exhibitions can be glimpsed from a critic’s commentary in 1969, confirming that the artworks typically paid ‘close attention to the people, the customs and the landscapes of the African lands or of the Hispano-Arab tradition’, and that ‘perhaps the most important aspect of these exhibitions may be the vigilance maintained over a long time by the organising entity of the event (…). Their labour of art has been truly distinguished throughout the twenty-one exhibitions’ (‘Los artistas africanos’ Citation1969).

Despite the longevity of these exhibitions, they have thus far received limited attention in surveys of Spanish Orientalist painting (Arias Anglés Citation2007, 33–35) and in studies of individual artists (e.g. Pleguezuelos Sánchez Citation2013, 119, 123, 127, 137; Hopkins Citation2017, 158–160). Only recently scholars have explored the exhibitions as a case study for the ‘re-definition of the catalogue concept' in Franco’s Spain (Sauret Guerrero Citation2019) and for the appropriation of al-Andalus (Hopkins Citation2019/20). The scholarly neglect is partly due to the fact that many of the exhibited artworks are no longer traceable, and partly because Orientalist painting does not fit into the art historical narratives of mid-twentieth-century Spanish art. Most recent scholarship and curatorial projects relating to Spanish art of the 1940s and 50s focus on the rise of abstraction, the formation of art collectives, and the staging of international exhibitions in Madrid and Barcelona, relating to new movements and groups, such as Informel, the School of Paris, and Abstract Expressionism. Analyses of the relations between Franco’s politics and art tend to pitch traditional figurative styles as a foil against which to explain the increasing importance of the avantgarde art as a modernising effort. Even impressive scholarly publications addressing the relations between art and power (Jiménez-Blanco Citation2016) ignore the case of the Painters of Africa exhibitions and the continued relevance of Orientalist painting in certain factions of the Spanish art world. Instead, the focus is typically on the International Congress of Abstract Art in Santander in 1953 as a landmark event, which signalled the official acceptance of abstract art (Jiménez-Blanco Citation2016, 34). Yet, surely it is not insignificant that Franco’s regime also encouraged artists, Spanish and Moroccan, to participate in the annual Painters of Africa exhibitions, staged in the centre of Madrid from 1950 to 1971. The public interest in these exhibitions can be gauged from the many reviews published in the press. They impacted on Spanish audiences and artists and also had long-term consequences for North African artists.

The purpose of this article is twofold.Footnote2 Its main focus is an analysis of the exhibition discourse and the reception of the Painters of Africa exhibitions until Moroccan independence in Citation1956, foregrounding the ideological issues underpinning the selection of artworks, the exhibiton programme, and the numerous reviews. The final part of the essay shifts the focus from Madrid to Tetouan to uncover the process by which the Painters of Africa exhibition rhetoric and the work of Spain’s most important Protectorate painter Mariano Bertuchi (Granada, 1886-Tetouan, 1955) were repurposed for forging an artistic identity of the ‘School of Tetouan’ after independence. As such, the article presents a compelling case study that sheds light on the mobilisation of art, curatorial practice, and art criticism in the interstices between two cultures in the fraught context of colonialism. The article challenges familiar understandings of Western attitudes to Islamic cultures in binary terms with which we have become so familiar since Edward Said’s Orientalism of 1978, and it illuminates the paradoxical processes that are involved in the formation of artistic identity in post-colonial northern Morocco.

Display and rhetoric: convivencia

The ideological framework of the Painters of Africa exhibition can be gauged from the opening speech ‘Fortuny y la pintura africanista’ at the first exhibition by José Francés on 9 March 1950, a prominent art critic and the secretary of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid. Focusing on the nineteenth-century painter Mariano Fortuny y Marsal (1849–1871), Spain’s most important and much admired Orientalist painter, he established a legitimate pictorial genealogy for the artists participating in the Painters of Africa exhibition. Francés reminded his audience that Fortuny had been deeply sympathetic to Morroccan culture. Even though he had discovered it during the so-called African War between Spain and Morocco in 1859–1860, Fortuny had shown more interest in picturing ordinary Moroccan life than in glorifying Spain’s military triumph on canvas. Furthermore, Francés argued, Fortuny’s ‘love’ for Morocco extended to Granada and the Alhambra, amounting to a rediscovery of ‘the ancient Arab soul that wanders among the walls and the gardens and the ponds’ (Francés Citation1951a, 18). According to Francés, Fortuny forged a path for later artists picturing North Africa, including those represented in the Painters of Africa exhibition.

Towards the end of his propagandistic speech, Francés conjured up an idyllic picture of the Spanish Protectorate, which had been established in the northern part of Morocco in 1912, alongside the French Protectorate in the southern part. He made no mention of the violent Rif War (1921–1926) and the independence movement, which was gaining traction. Instead Francés pointed to flourishing Spanish-Moroccan relations, because Moroccan men had ‘seized their spears, raised their voices and hearts in unison, and fraternally joined the Spanish people and race to free the protective homeland’ (Francés Citation1951b, 26–27). With this he alluded to the thousands of Moroccan merceneries recruited by the falangists to fight on Franco’s side in the Civil War against the legitimate Spanish Republic (1936–1939) (Madariaga Citation2002). Francés’s rhetoric was entirely in line with Francoist war propaganda, which consistently presented the Nationalist uprising as a crusade and a new ‘reconquista’ in order to ‘free Spain from Marxism’ (Arrarás Iribarren Citation1939–Citation1941, prologue, unpaginated).

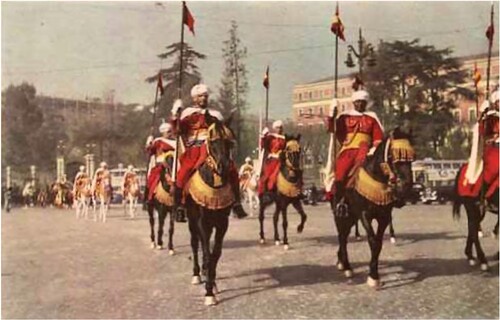

As living evidence of this alliance between Nationalists and Muslims, Francés pointed to the guardia mora (Moorish Guard) – the Moroccan soldiers chosen by Franco as his permanent escort after 1939 and a common sight in public life during his dicatatorship (). Blurring the boundaries between art and reality, Francés described their appearance in picturesque and symbolic terms, as if describing an Orientalist painting:

They are a flutter of oriental clothes and a brilliance of weapons and spirited horses, mixed with the sounds of instruments of gallant Moorishness under the Spanish sky.

They are the joyful symbol of an eternal convivencia because in us [Spaniards] there is something that we cannot and do not ever wish to deny: the secular and ancestral pride of Arab civilization and sensibility. (Francés Citation1951a, 26–27)

Francés’ positive remarks about al-Andalus and Morocco were not arbitrary reflections but tapped into a well-established colonial discourse, which originates in the nineteenth century. It is worth outlining the main tenets and examples of expressions here. As historians have demonstrated, Spanish writers began to articulate similarities between Andalusia and Morocco (people, landscapes, architecture, cities) in the context of the African War of 1859–1860 (Martin Márquez Citation2008; Calderwood Citation2018). As Spain’s ambitions in the region developed, intellectuals consolidated the discourse of similarities. In 1884 the politician Joaquín Costa even suggested that Moroccans and Spaniards shared a blood brotherhood, because they shared a past in medieval al-Andalus. In the early twentieth century, as several European powers vied for domination in Morocco, Spanish ideologues mobilised the Andalusí past as a justification for colonisation, arguing that Spain was the most suited of all European powers to intervene. The argument was that the medieval Arabs’s achievements in science, philosophy, and the arts had benefitted Spain in the past (Jensen Citation2005, 89), and it was therefore only natural that, in modern times, Spain should help its weaker ‘sibling’ Morocco (Mateo Dieste Citation2003; Martin Márquez Citation2008, 57). In reality, Spain’s expansionist ambitions were also motivated by a desire to compensate for the country’s traumatic loss of Cuba in the Spanish-US war of 1898: it not only signalled the end to Spain’s empire but also triggered a profound crisis in the national psyche. In the early twentieth century, following a period of instability in Morocco, European powers and the US decided Morocco’s fate at the Conference of Algeciras of 1906, leading to the establishment of a Protectorate in 1912, with the southern part coming under French control, and the northern part under Spanish control. It is in this context that the memory of al-Andalus was regularly conjured up in multiple media. A relevant example is the Revista de tropas coloniales, founded in 1924, which juxtaposed photographs of urban views of Spanish and Moroccan cities, such as Seville, Cordoba, Granada, Chefchaouen, Rabat, Tetouan, revealing a shared architectural Andalusí heritage (Bolorinos Allard Citation2017, 119–125).

The colonial administration also promoted identification with the material culture of al-Andalus by setting up Tetouan’s School of Indigenous Art (Escuela de Artes Indígenas de Tetuán) in order to revive the material culture of al-Andalus to which both Spanish and Moroccan audiences could relate. The school was led by Mariano Bertuchi, a key figure in Protectorate society since the 1920s and a prolific artist, who visualised Morocco through paintings, illustrations for books and magazines, and designs for stamps and tourist posters – often evocative of Spanish-Moroccan connections (Hopkins Citation2017). Bertuchi also served as the first director of Tetouan’s Preparatory School of Fine Art (Escuela de Preparatoria de Bellas Artes), founded in 1945 with the aim to train both Moroccan and colonial Spanish artists in easel painting. Paralleling Bertuchi’s role in art, the priest Patrocinio García Barriuso (1909–1997) was a central figure in the promotion of traditional Moroccan music and its Andalusí roots. It is therefore no coincidence that García Barriuso’s publication La música hispano-musulmana en Marruecos (1941) featured a painting by Bertuchi on its cover, depicting a turbaned lute player at the Alhambra and thus suggesting Granada as a point of origin for Moroccan music (Calderwood Citation2018, 253, n.1).

As demonstrated by Eloy Martín Corrales, the cultural and commercial exhibitions staged across Spain throughout the colonial period before and after the Civil War (1936–1939) were also important vehicles for introducing Morocco to Spanish audiences (Martín Corrales Citation2007, 88–94). They included displays of artisanal products made by the pupils of the School of Indigeneous Art in Tetouan for the Moroccan pavilion at the 1929 Ibero-American exhibition in Seville. After the Civil War, such craft displays were shown in Granada (Exhibition of Granadan and Moroccan Art, 1940), Melilla (Exhibition of Crafts, 1945), Cordoba (Exhibition of Moroccan Art, 1946), Madrid (Exhibitions of Decorative Arts in 1946 and in 1949), Tetouan (Exhibition of Hispano-Moroccan Crafts, 1947 and 1953) and Tangiers (Exhibition of Crafts, 1955). International trade fairs too were important. At the fair in Barcelona in 1942, visitors encountered artisanal products and an exhibition of paintings by Bertuchi, advertised in the exhibition pamphlet:

a new Morrocan art, which preserves the strong warp of the Orient and features modalities of old Hispanic flavour. Its obvious leader is an illustrious Spaniard named Bertuchi, who, like Leonardo da Vinci, masters nearly all the Muses of Parnassus. (…) with this Exhibition, a path has opened for further unifying Spain with our Protectorate. (Catálogo de la exposición y talleres del pabellón de Marruecos Citation194Citation2, n.p.)

The portrayal of Morocco as a colonial idyll was pure propaganda. In reality, the years immediately after the Civil War were followed by hunger and drought in the Rif, migration from rural areas to cities, and increasing prostitution and drug abuse, as described in the classic novel For Bread Alone (1973) by Mohamed Choukri. The anthropologist Mateo Dieste has further pointed out that social relations between Spaniards and Moroccans were not homogenous, as Moroccans reacted to colonialism differently. On the one hand, the close collaborations between high-ranking Moroccan individuals and Spanish officials were vital to the functioning of the indirect government of the Protectorate (the Majzen). Friendly relations existed, and sections of Moroccans were seduced by the colonial promise of progress. But on the other hand, resistance and anti-European sentiment were well-established in the Moroccan imaginary. Moreover, Islamic law forbade Moroccan Muslim women to enter in intimate relations with Christian men. The colonisers, in turn, regarded their supposed ‘brothers’ as inferior and took measures to suppress the formation of Moroccan-Spanish couples, in direct contradiction with the concept of a brotherhood (Mateo Dieste and García Citation2020, 55–56, 60-62; Jensen Citation2005, 92–93).

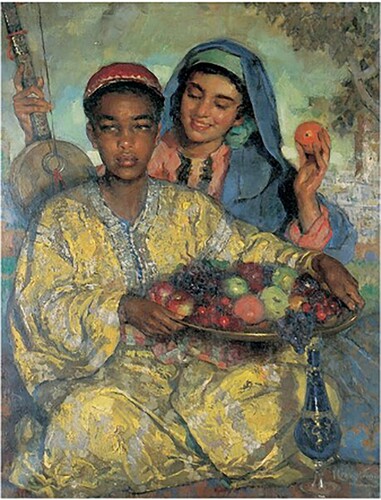

Bypassing the complexities that marked real life in the Protectorate, the speeches and awards at the Painters of Africa exhibitions reveal the regime’s ideological interests in consolidating ideas of Spanish-Moroccan connections. In 1950, the jury, composed of eminent figures in institutional positions, including the Director of the Prado Museum and others affiliated with the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, awarded the first prize to José Cruz Herrera (1890–1972) for a colourful depiction of a young ‘black slave’, seated on the ground and holding a platter of fruit, and a smiling girl with a lighter complexion, mischievously helping herself to an orange (). This was one of three exuberant images by Cruz Herrera, depicting healthy and joyful looking Moroccan inhabitants of different ethnicities. In his speech, Francés likened the images to the artist’s earlier paintings of Andalusian children and women, ‘with dark skin’ and seductive smiles, thus implying ethnic links between Morocco and Andalusia. Cruz Herrera’s multi-ethnic imagery resonated with the concept of Hispanicity (Hispanidad), which was evoked in a hyperbolic propaganda speech by Andrés Ovejero Bustamente (1871–1954), professor of literature at the University of Madrid. Ovejero praised the colonial administration for succeeding in bringing ‘[African] peoples, distant for many centuries’ closer to Spain and in revealing ‘the common heartbeat of the common wing that unites us’ (Ovejero Citation1951, 34). Therefore, it should be a great ‘lesson’ for the whole world to realise that Spain’s national sentiment was ‘so vastly generous that it unites the races within it’ (Ovejero Citation1951, 35). To substantiate his argument, Ovejero quoted Spain’s Golden Age writer Miguel de Cervantes that Spain was ‘the mother of all nations’, and therefore ‘all the conditions of foreigness’ ceased to exist for those who reached ‘the intimacy of the Spanish fraternity’ (Ovejero Citation1951, 36). Such ideas also found expression in other spheres, such as the Hispanoamerican art exhibitions staged in Madrid (1951), Barcelona (1955), and Havana (1955). They were organised by the Instituto de la Cultura Hispánica to celebrate relations between Spain and its former South American colonies. Notions of a Hispanic, multi-ethnic fraternity were particularly valued in these years when Franco’s regime was still shunned by the democratic West.

Figure 3. Reproduction of José Cruz Herrero, El esclavo moro, in Primera exposición de pintores de África, 1951. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

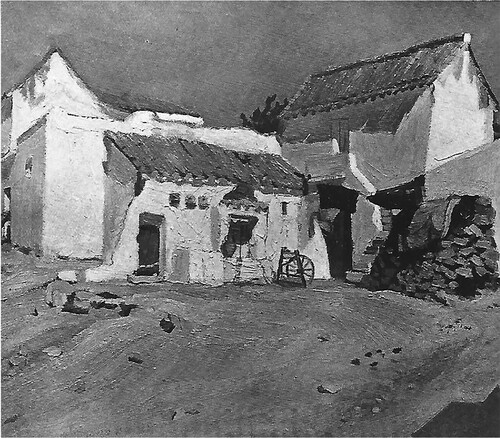

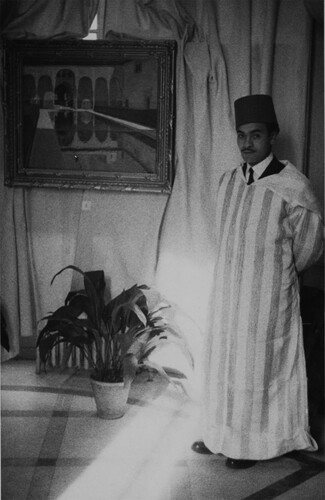

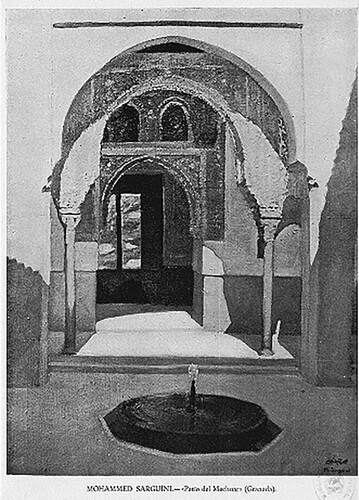

The Painters of Africa organisers also put the idea of a transnational fraternity into practice by encouraging African artists to take up painting and participate in the exhibition. The most prominent figure was the Larache-born artist Mohamed Sarghini (1923–1999), who trained at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in the 1940s and had already exhibited his works in the Madrid headquarters of the Dirección General de Marruecos y Colonias in 1947 (). At the first Painters of Africa exhibition, he won a prize for a painting of the Mexuar courtyard in the Alhambra, now only known through an illustration (). Francés praised it for ‘evoking the Arab traces in Spain, the architecture and the evocative splendour of the Alhambra’ (Francés Citation1951a, 26). The melancholy mood of Sarghini’s picture of the empty courtyard contrasted with Cruz Herrera’s exuberant scenes of sensual figures. When seeing their images together, the implication is clear: if the ancient Nasrid palace was a noble ‘trace’ of a Hispano-Arab past, its culture was healthy and alive in Morocco.

Figure 4. Anon., Mohamed Sarghini exhibiting his works in the Dirección General de Marruecas y Colonias, c. 1947, photograph. Biblioteca Nacional de España. GC-CARP/382/2/9.

Figure 5. Reproduction of Mohamed Sarghini, El patio del Mexuar, in Primera exposición de pintores de África, Citation1951. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

Following the first Painters of Africa, the organisers made efforts to include artists working in more modern styles, but they essentially continued the thematic emphasis on Africa on the one hand and al-Andalus on the other. Images of streets, markets, ceremonies, individual figures, occasionally still life objects, and natural landscapes revealed a peaceful, attractive life in Spain’s colonial territories, thus serving as soft power for colonial ideology. The negative Orientalist tropes of an exaggerated sensuality, violence, fanaticism, and folkloric aspects – so typical in nineteenth-century Orientalist paintings – were absent.

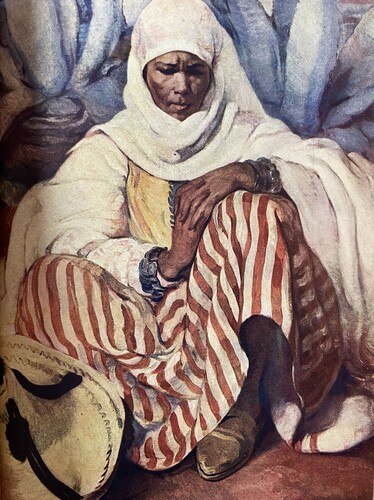

The depictions of single figures often convey a sense of gravity, seriousness, or melancholy, such as the seated pensive black woman in a work titled Quietness () by Rafael Pellicer Galeote (Madrid, 1906–1963), a realist painter based in Cordoba. His painting won the first prize in 1951 (Segunda exposición de pintores de África Citation1951, 61; Antolín Paz Citation1994, 3213–3215). Similarly Genaro Lahuerta’s classicising, almost severe representation of a Moroccan woman, titled Zahia, defies clichés of oriental immorality or sensuality. It received a prize at the fifth edition (Quinta exposición de pintores de África 1954, 25). At the same exhibition, the Moroccan painter Martyn Prados was awarded a prize for a realist portrait of a Jbala man of Chrouda ().

Figure 6. Reproduction of Rafael Pellicer, Quietud, in Segunda exposición de pintores de África, 1951. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

Figure 7. Reproduction of Martin [Martyn] Prados, Yebli de Cheruda, in Quinta exposición de pintores de África, 1954. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

![Figure 7. Reproduction of Martin [Martyn] Prados, Yebli de Cheruda, in Quinta exposición de pintores de África, 1954. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.](/cms/asset/0bafd9d5-238f-45be-a3fa-fd426a650c3f/rwor_a_2150886_f0007_oc.jpg)

Artists working in more modern styles were rewarded too, such as María Jesús Rodríguez, who received a prize for a painting of two stylised figures of Moroccan women, painted with a palette knife (Segunda exposición de pintores de África Citation1951, 61). Today forgotten, Rodríguez had graduated in drawing at the fine art school of San Fernando in Madrid, and subsequently became one of the teachers at Tetouan’s Preparatory School of Fine Art, then under the directorship of Bertuchi (Bacaicoa Arnaiz Citation1967, n.p.). At the third exhibition, the jury awarded her again a prize for a painting The sale of a goat (now lost) (Tercera exposición de pintores de África 1953, 24). At the fifth exhibition, which had two venues (Madrid, Círculo de Bellas Artes; Barcelona, Palacio de la Virreina), the jury awarded Tomás Ferrándiz Llopis (Alcoy, Alicante 1914–2010) a prize for his stylised sculpture Moorish woman. Like Rodríguez, Ferrándiz Llopis taught at the Preparatory School of Fine Art in Tetouan and had initially trained at the Academy in Madrid (Antolín Paz Citation1994, vol. 5, 1275–1276). Similarly, the young Basque artist Néstor Basterretxea (Bermeo, 1924-Hondarrabia, 2014) received a prize for his schematic rendering of two figures in Black Servant and Moorish Musician, consisting of flat surfaces against an abstract background.

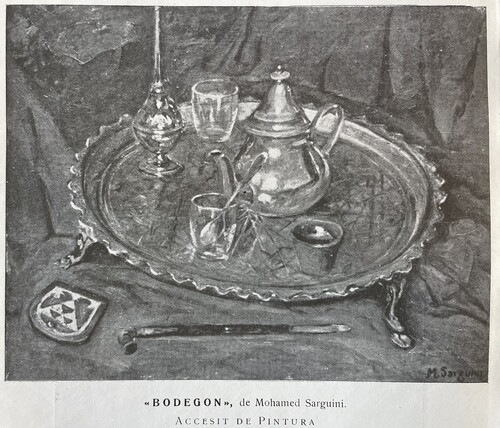

A number of still lifes were included at every exhibition and recognised as important. At the fifth exhibition Sarghini received a prize for a painting of a tea service, alluding to Moroccan traditions and material culture, which was being revived by the colonial administration (Quinta exposición de pintores de África 1954, 25). ().

Figure 8. Reproduction of Mohamed Sarghini, Bodegón, in Quinta exposición de pintores de África, 1954. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

The abovementioned Bertuchi was included as an honorary artists at the fourth and fifth exhibition (in the second Barcelona venue), and posthumously at the seventh exhibition (Catálogo de la VII exposición de pintores de África Citation1956). His images were already well-known amongst the Spanish public, not just through paintings, but also illustrations, posters, and designs for stamps. Avoiding Orientalist clichés, his pictures presented Morocco as an attractive idyll, often alluding to the memory of al-Andalus or prompting comparison with aspects of life in Spain: domestic interiors, markets, or public festivities. An example is La Pascua Grande (), which depicts an orderly procession led by the Jalifa through the streets of Tetouan on the occasion of the ‘festival of sacrifice’, an annual event commemorating Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac (Cuarta exposición de pintores de África Citation195Citation3, 16). Consistent with the idea of a harmonious way of life in Morocco, Bertuchi reveals a people unified in their faith and respectful to authority. For audiences in Francoist Spain, Bertuchi’s depiction of a Moroccan procession did not vastly differ from the open-air congregations, processions, and military parades that could be seen all across the Peninsula. As Bertuchi died in 1955, the seventh Pintores de Africa exhibition, which took place only a month before Moroccan independence, was conceived as a homage to him, where he was posthumously awarded the first prize.

Figure 9. Mariano Bertuchi, La Pascua Grande, n.d., oil on canvas, 125 x 100 cm. Ministerio del Interior, Madrid. Courtesy M. Bertuchi Alcaide (2017).

Alongside the African themes, the exhibitions included images of Andalusian architecture or street views, which conjured up a memory of al-Andalus. In his speeches, Francés praised the juxtaposition of Moroccan scenes with such views evoking the ‘eternal testimonies’ of Spain’s Arab legacy (Francés Citation1951b, 52), and he urged his audience to experience them with a sense of nostalgia. Francés did not merely refer to the most emblematic buildings, such as the Alhambra, but pointed to vernacular architecture across Andalusian towns and villages, as shown in a picturesque view of a sunlit corner in Arcos de la Frontera, one of the ‘white villages’ that had flourished in al-Andalus (). It was awarded a second prize. At the third exhibition, judging from the titles of the exhibits, the theme of al-Andalus was expressed in painting and sculpture, as in Arches of the Calle Averroes in Cordoba, a painting (now lost) by Rafael Álvarez Ortega (1927-2011), an artist and illustrator who had trained in Seville and in Madrid (Antolín Paz Citation1994, 125). A painting titled Arab corner in Toledo by Francisco Andrada was evocative of the Arab presence in medieval Toledo, whilst two sculptures Boabdil and Aixa by Tomás Ferrandiz pointed to Nasrid Granada, one depicting the last Nasrid King and the other his mother (Tomás Citation1953, 97).

Events

The exhibited artworks were given meaning by a rich programme of lectures, concerts, and poetry readings, which embraced the exhibitions' twin focus on present-day Morocco and the memory of al-Andalus. At the second exhibition, a singer and lute player, named as Mohammed ben El Mojtar b. el Amin and Mohammed ben Abdel-lah b. Ayad, gave a concert of ‘Arab-Andalusian’ music in the exhibition space. This was followed the next day by a piano concert, featuring compositions evocative of Spain’s past: España. Recuerdos by Isaac Albéniz; Fiesta mora en Tánger by Joaquín Turina; Morisca y Canción árabe by Enrique Granados, and Fantasia baetica by Manuel Falla (Segunda exposición de pintores de África Citation1951, 29, 33–46). Similar concerts also featured at the fourth and fifth exhibitions, and a Spanish university choir sang Andalusí-themed ballads at the fifth one (see Cuarta exposición de pintores de África Citation1953, 31–32; Quinta exposición de Pintores de África, 1954, 29–34). At the seventh exhibition (1956), the concert was preceded by ‘explanatory words’ by the musicologist Arcadio Larrea Palacín (1907–1985), who had researched musical traditions in Spain’s colonial territories since 1950 (AGA 81.15653). It gave context to the musical performance and the paintings that featured Moroccan figures singing or playing musical instruments.

When Larrea Palacín’s spoke again at the 1958 edition of the exhibition, two years after Moroccan independence, his speech ‘Ancient Spanish music in North Africa’ was published as a pamphlet. This time he urged his audiences not to forget that despite the dissolution of the Protectorate of Morocco, ‘Spain continues to be present in the cities and territories, which are undisputible Spanish’ (Larrea Palacín Citation1960, 35). The lecture centred on the influence of medieval Castilian song on Andalusí music in Muslim Granada, and its introduction to North Africa due to the migration of Moriscos and Sephardies to North Africa. There, Larrea Palacín explained, it is called ‘“Andalusian” music, which means Spanish and also Granadan’ (Larrea Palacín Citation1960, 36). Considering the post-colonial situation, he recommended ‘a change of attitude to the problem of our relations with North African people’ and a ‘maximum stimulus’ of cultural elements in order to achieve cordial relations and ‘to dispel the mistrust born of our forced political action in the past’ (Larrea Palacín Citation1960, 36). He concluded that music was the most ‘endearing’ cultural element connecting Spaniards and Moroccans, and that the new political circumstances could ‘never erase the permanent truth of Spanish relations with Africa’ (Larrea Palacín Citation1960, 42).

Larrea Palacín’s insistence on cultural Spanish-Moroccan relations was hammered home by the many other propaganda speeches and academic lectures delivered at the exhibitions. Already at the second exhibition, José Francés declared:

There is so much of us in them, and so much of them in us! Shared roots nourish our races and gave life to art and poetry, bravery and mysticism here and there. Permanent traces, indestructible evidence of the Arab in Spanish cities; eurythmy of coinciding rhythm, of parallel routes in ideology, the sentimental and the sensitive. A strong continuity of tradition, a coming and going of distant echos, burning passions. (Francés Citation1951b, 52)

Reception

The exhibition reviews generally reflect a positive and popular reception. For instance, at the fifth exhibition, one journalist stated that

an enthusiastic and diverse public attended the opening (…) Many women, students, artists, men with a passion for Morocco (…) In the large salon of the Círculo de Bellas Artes are 53 works, some in a large format, by 38 artists. There are magnificent works. There are also 17 sculptures to be admired. In the salon Minerva are watercolours, drawings, and prints, 41 works, also noteworthy. 111 works overall. Our Morocco cannot complain! (Carabias Citation1954, 122)

A dominant theme running through the press reviews in the early 1950s is the idea of affinities between Spain and Africa, and expressions of empathy towards Moroccan people. One article, reproduced in four newspapers, asserted that the paintings revealed similarities between Andalusia and Africa (María de Vega Citation1951, 80). Another critic enthused about the ‘delight of Moorish music’ that the exhibitions offered, because such concerts stimulated ‘thinking towards the history of our ancestors’ (Guillot Carratala Citation1953, 75–76, my emphasis). Other critics praised Cruz Herrera’s three paintings ‘Arab musicians, Moorish slave, Jews’ as empathetic images, which truthfully depicted ‘the racial characteristics of the stock of Moorish lands’ (cited Pleguezuelos Sánchez Citation2011, 119–120), and another remarked that it was impossible to tell whether Cruz Herrera’s figures were based on Spanish or Moroccan models. ‘What does it matter any way?’ the writer asked, because, ‘deep down Spaniards and Moroccans are all one. This is the great lesson of the exhibition’ (Varón Citation1951, 126).

The strongest assertions in terms of Moroccan-Spanish affinities were made by Rodolfo Gil Benumeya (1901–1975), a leading theoretician of colonialism, Spanish-Moroccan history, and a commentator on art and photography of Morocco. As Eric Calderwood has pointed out, Benumeya’s own identification with al-Andalus is indicated by his pen name ‘Benumeya’, which means ‘son of the Umayyads’, alluding to the medieval caliphat of Córdoba (Calderwood Citation2014, 411). At the first Painters of Africa exhibition, Benumeya praised Cruz Herrera’s depiction of a lively group of male and female figures, with an accordion player in the centre. Benumeya pointed out that the singing figure on the left ‘with her mouth half-open seems to be singing an Andalusian song from the time of Arab al-Andalus’ (Gil Benumeya Citation1951, 115). For Benumeya, the picture confirmed that the culture of medieval Spain, especially that of Granada, had influenced North Africa, and therefore, Morocco and Andalusia were something like twins or siblings.

Benumeya made similar observations in relation to representatons of Andalusí architecture. He singled out two works: the Alcazaba of Almeria (untraced) by Francisco Alcaraz, a painter of the (under-researched) Indaliano movement in Almeria (Durán Díaz Citation1981). The other painting was the abovementioned Mexuar court in the Alhambra by Sarghini (). Benumeya’s passage is worth quoting in full here:

… the art from southern Spain (…) went to North Africa or Barbary. Morocco is not possible without her sister Andalusia, and the undeniable memory of its [Morocco’s] Iberian origin is represented in the Exhibition (…) with two symbolic artworks: The Alcazaba in Almería by Francisco Alcaraz and A courtyard of the Alhambra by Mohamed Sarghini, a young Moroccan and Muslim painter from Larache, who has a Spanish title from the School of San Fernando in Madrid. Sarghini, a good colourist and lover of Granadan themes, is a living symbol of the fraternal artistic exchange between Moroccans and Spaniards. (Gil Benumeya Citation1951, 115)

the proof that the various territories known under the general label of Spanish Africa, or Hispano-Maghreb, are not and cannot be exotic, but they are an extension of peninsular aesthetics [my emphasis]. (Gil Benumeya Citation1951, 115)

a search for a way of feeling, understanding, and loving the landscapes, the architecture, and the daily life of the Muslims of the Maghreb, analysing within themselves everything that recalls ancient Spain […] In this manner the Spanish painters who go to Morocco are able to avoid the dangers of an easy picturesqueness. (Gil Benumeya Citation1951, 86)

At the seventh exhibition of 1956, the reviewers did not engage with the imminent Moroccan independence, as if in denial (Camón Aznar Citation1956). Critics praised the ‘high artistic quality’ of works by older artists, such as Bertuchi, Cruz Herrera, and Lahuerta, alongside younger ones: the ‘brilliant chromatic examples of impressionism in the service light, life, and movement’ by Bertuchi; the ‘restless’ works by Salvador Rodríguez Bornchu’s (1913–1999); the ‘vibrant’ picture by Ramón Vilamoso; the ‘Gauguinesque’ scenes with a ‘daring’ facture by Amadeo Freixas Vivó; the ‘advanced’ and ‘balanced’ paintings by Waldo Aguilar (1930–2000), the ‘graceful’ paintings by Mohamed Sarghini (Cobos Citation1956, 7). One critic still praised the exhibition for revealing the beauties of ‘our Protectorate’ and promoting relations between ‘the two fraternal countries’ (‘Pintores de África’ Citation1956).

The Moroccan perspective

If the first six Pintores de Africa exhibitions were soft power in the service of colonial discourse and international diplomacy, what did this exhibition discourse mean to the participating Moroccan artists and performers? To what extent were they invested in the idea of a shared Spanish-Moroccan past and a continuing convivencia? As Eric Calderwood has shown, the colonial myth of an idealised al-Andalus migrated from the Spanish discourse into a discourse of the Moroccan independence movement in which it was repurposed for shaping a modern Moroccan national identity (Calderwood Citation2018, 277). For Moroccan intellectuals, al-Andalus signalled a culture of refinement at a time when Morocco had influence across the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa. It was a source of pride. Regarding music, for example, the nationalist Abd al-Khaliq al-Turris asserted that Morocco and al-Andalus played a great role in the formation of the musical heritage for Arab civilisation’, and that music was essential for a renewal of the Moroccan people (Calderwood Citation2018, 247). In fact, the establishment of a conservatory in Tetouan in the early 1940s was initiated by Moroccan nationalists with the support from the Spanish authorities.

Seen against the Moroccan interest in claiming al-Andalus as part of their legacy, the Moroccan musicians who performed Andalusi music at the Painters of Africa exhibitions in Madrid were engaged in an ideologically muddled performance: on the one hand they were recruited to serve Spain’s colonial discourse; but, on the other, they were psychologically invested in a revival of an Andalusi heritage that nourished Moroccan thinking about independence. Similarly, it can be argued that Sarghini’s picture of the Alhambra, The Mexuar Courtyard (), or his still life of a tea set, were not a blind assimilation of Spanish pictorial conventions and colonialist rhetoric but responded to his own interests in al-Andalus at a time when independence was in sight.

After 1956, Sarghini became an important figure in the Moroccan artworld as an artist, curator, and director of the renamed National School of Fine Art of Tetouan (the former Preparatory School of Fine Art), which had developed a reputation in colonial and mainland Spain under Bertuchi’s directorship until his death in 1955. In 1953, a promotional photo reportage on the Protectorate, published in the magazine Fotos, explained that the artists of the ‘school of light and colour’ in Tetouan included numerous artists, amongst them Sarghini (Fotos Citation1953, 15). After independence, far from rejecting Bertuchi and the Tetouan school for their colonial associations, Sarghini was key in consolidating Bertuchi’s status as the founder of what he labelled the ‘School of Tetouan’. While Bertuchi was largely ignored in mainstream art writing in Spain, he was turned into an important figure in the Moroccan context. As the Ceuta-based historian José Luis Gómez Barceló (Citation2009) outlined in a survey of Tetouan painters, four artists emerged from this school, which are described as the ‘first generation’: Meki Megara, Ben Cheffaj, Ahmed Amrani, and Mohamed Ataallah. They were followed by three generations of artists, many of whom completed their training in art institutions in Europe. The label ‘School of Tetouan’ was disseminated through a number of exhibitons across Morocco and Spain from the 1960s onwards, often referring to, or including works by Bertuchi as a founding figure. In the Spanish context, this is exemplified by small-scale exhibitions of artists from Tetouan, staged at El Ateneo in central Madrid under the title Escuela de Tetuán. Homenaje a Bertuchi (School of Tetouan. Homage to Bertuchi, Madrid, 1967). Amongst the artists, selected by the Spanish Consul in Tetouan, were Meki Megara, who had already featured in a solo exhibiton in El Ateneo in Madrid in 1965, and Ahmad Hassan Amrani, Amina de Melehi, Saad Ben Seffaj, alongside Spanish artists living in Morocco, María Jesús Rodríguez, Damas Ruano, and Carlos García Muela. According to the critic Carlos Areán these artists brought ‘their works together in homage to Bertuchi. They know that without Bertuchi the artistic School of Tetouan would not have become what it is (…) Bertuchi formed a generation of artists from whom those presented here emerge’ (Areán Citation1967, unpaginated). According to the prologue in the exhibition pamphlet too, the artists have their origin in the former colonial School of Fine Art of Tetouan and the ‘fabulous painter from Granada’ Bertuchi – ‘Don Mariano’, the director and ‘soul’ of that school. Nevertheless, the writer cautioned readers, stating that the artists were ferociously individualistic:

according to my own observations (…) the members of the Tetouan group dislike being considered as a ‘school’. They do not like to be diluted by a label, no matter how flattering it may be, and they are the ones who deny the existence of common points, some with their words, other with their silence. (Bacaicoa Arnaiz Citation1967, unpaginated)

The label ‘School of Tetouan’ did, however, continue to flourish, albeit not uncontested. In the Moroccan context, Sarghini promoted the label in the exhibition catalogue Pintores marroquíes de la Escuela de Tetuán (Morrocan painters of the School of Tetouan), an exhibition associated with the I Encuentro de intelectuales magrebíes de expresión española (First encounter of Spanish-speaking Maghreb intellectuals) in Marrakesh in 1989. He upheld that the artists constituted an ‘artistic school’, which had its roots in the developments of the 1940s. The colonial discourse of the Painters of Africa exhibitions here finds an echo in Sarghini’s assertion that it was thanks to the ‘fraternity, convivencia and the mutual, Spanish-Moroccan creative work’ that the first Tetouan artists formed an entire school, ‘received the breath of life’ and flourished through younger artists (Sarghini Citation1989, 1, cited in Jiménez Valiente Citation2018, 165). A few years later, the label ‘School of Tetouan’, alongside the idea of a Spanish-Moroccan tradition and a claim to modernity, was mobilised for official, Moroccan self-representation in the international context of the universal exposition Expo ’92 in Seville. The Moroccan pavilion featured the exhibition 18 artistas marroquíes y españoles de la Escuela de Tetuán (18 Moroccan and Spanish artists from the School of Tetouan), curated by Ben Yessef, an artist who had studied in Seville in the late 1960s. In the catalogue he explained that an artist’s affiliation to the School of Tetouan implied: ‘a union of two cultures and an authentic fusion between Moroccan and Spanish traditions, with a highly positive and enriching result in the global artistic panorama’ (cited by Jiménez Valiente Citation2018, 238). In aesthetic terms, Yessef felt that the School of Tetouan could by characterised by the use of Arab calligraphy, and the study of white ‘treated in a distinct and varied manner of tones and shades (…), the exposed form of the picture surface, with a tremendous sense of innovation, which signals modernity in the world of painting’ (cited by Jimenez Valiente Citation2018, 238).

The desire to construct a shared identity for Tetouan artists is still evident in certain exhibition initiatives in the twenty-first century (see for example, 9 Discípulos de Bertuchi Citation2000). In 2004, an exhibition staged in Cuenca, near Madrid, at the Fundación Antonio Pérez, showed the work of four younger Tetouani artists: Abdelkrim Ouazzani, Younès Rahmoun, Safaa Erruas, Hassan Echair under the title The New School of Tetouan (La nueva escuela de Tetuán). In the exhibition catalogue, the origin narrative is upheld:

Since its creation in 1945, the School of Tetouan has contributed to the formation of the greatest figures of contemporary Moroccan painting. Although famous for its realist painters, loyal to the legacy of Bertuchi and figuration, it nevertheless accommodates names who, since the 1960s, have embraced the rise of a contemporary art in Morocco. (Zahi Citation2004, 7)

Three years later, the Museum of Ceuta, just 30 km away from Tetouan, presented Escuela de Tetuán: 50 Años de reflexión: A. Amrani, R. Ataallah, S. Ben Cheffaj, M. Megara (15 May to 13 July 2007, Museo de Ceuta), curated by the Ceuta historian José Luis Gómez Barceló. In the preface of the catalogue, the Councilor of Education and Culture of Ceuta reiterated the origin of the school in Bertuchi and the trope of Moroccan-Spanish connections:

Spain and Morocco have fed, during centuries, from the same source of culture (…) this is and will be the great bridge of union, facilitating understanding, respect, and knowledge of different people (…) The seed from which this magnificent art movement emerged in Tetouan during the twentieth century is the [Preparatory] School of Fine Art, founded by the Granadan painter Mariano Bertuchi Nieto. (Museo de Ceuta Citation2007, n.p.)

They know that they are from the School of Tetouan, but perhaps many others do not know this or attempt to transform the sense of the trajectory, which was outlined for Moroccan artists by a Spanish painter – as Spanish as a Granadan painter can be, called Mariano Bertuchi. (Museo de Ceuta Citation2007, n.p.)

artistic, pedagogical, social, and interactive events, which would favour the writing of a history of art in Morocco, according to the criteria contained in the abovementioned values, with the aim to re-establish some truths, and therefore offer the public a perspective on an art that is original, independent, and of a universal ambition. (Museo de Ceuta Citation2007, 10)

A more recent attempt at sketching out a history of modern Moroccan art relativises the importance of the School of Tetouan by setting it into a wider pan-Moroccan panorama. Abdellah Karroum, curator of the pioneering exhibition Trilogía marroquí (Moroccan Trilogy, Museo Nacional de Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2021) acknowledges that Tetouan’s Preparatory School of Fine Art had been important for forming an ‘entire generation’ of artists who then went to Europe. But he refrains from mentioning Bertuchi or the Painters of Africa exhibitions, which mark the beginning of Sarghini’s career. He draws attention to the French Protectorate of Morocco, asserting that the Fine Art School in Casablanca, founded in 1950, was also important in forging links with French and Italian artworlds. According to Karroum, access to these schools in Casablanca and Tetouan had not been easy for Moroccan artists in the Protectorate period, and that after independence, the schools lacked resources; in his view, much of modern Moroccan artistic production developed outside schools, thus playing down the importance of the Tetouan painters Amrani et al.

Figure 11. Jaro Varga, Building of the Centro de Arte Moderno in Tetouan, former train station, photograph. Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Antigua_estaci%C3%B3n_de_tren_de_Tetu%C3%A1n_(02).jpg.

The museum’s director Manuel Borja-Villel introduced the Moroccan Trilogy exhibition as the museum’s attempt at widening the focus of their decolonial analysis to other territories (Borja Villel Citation2021, 15). Whilst this is an important initiative, the challenges of selecting representative artworks are enormous. As Karroum suggests, the history of modern Moroccan art is that of a multiplicity of voices, memories, and understanding of the art (Karroum Citation2021, 20–22). He explains that the focus of Morrocan Trilogy is informed by the narratives written by art enthusiasts and artists’ biographers, such Mohamed Sijelmass and Latifa Serghini, and European historians and ‘friends of Morocco’ (Karroum Citation2021, 31) such as the French critic Pierre Restany (1930–2003), and Toni Maraini (b. 1941), supporter of the avantgarde magazine Souffles, published in Rabat between 1966 and 1972. Based on such sources, the catalogue constructs a vibrant image of modern Moroccan art, but does not fully address the complex historiography of Moroccan art and the development of its institutions.

To conclude, the Painters of Africa exhibitions constitute a remarkable effort at popularising the notion of a Spanish-Moroccan brotherhood with reference to an idealised vision of al-Andalus with which both Spaniards and Moroccans could identify. This discourse did not deal in difference, which is often seen in other contexts of East–West interactions; it cannot be understood through the notion of the exotic ‘Other’, with which we have become familiar since Edward Said’s landmark book Orientalism (1978). But like the discourse of otherness, a discourse of affinities can also be a tool of suppression and colonisation. Clearly, at the Painters of Africa exhibition, the memory of al-Andalus was mobilised to serve colonial propaganda, promoting a positive image of Spanish rule in northern Morocco. The arts were used as soft power. Although the Painters of Africa exhibitions lost part of their purpose after Moroccan independence, paradoxically, the ideas of a Moroccan-Spanish artistic fusion and affinities, originally driven by Spanish colonialists, took on new shapes and forms in the postcolonial artworld in northern Morocco, where they are still relevant today in certain cultural spheres.

The Painters of Africa exhibitions not only shed light on art practice, curation, and art writing that took place in the interstices between two cultures in the fraught context of colonialism, but they also illuminate the complex and paradoxical processes that underpin the formation of artistic identity in post-colonial societies, such as northern Morocco. It is precisely this kind of material that deserves to be studied if scholars are to develop an advanced understanding of twentieth-century art in a global context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Claudia Hopkins

Claudia Hopkins is Professor and Director of the Zurbarán Centre for Spanish and Latin American Art at Durham University. Before joining Durham in 2020, she was Senior Lecturer in History of Art at the University of Edinburgh. Her research mostly focuses on nineteenth- and twentieth-century art in relation to issues of cultural translation, centre/periphery, and constructs of self and others. Amongst her publications are the edited volumes Orientalism and Spain (2017) with A. McSweeney, and Hot Art, Cold War – European Writing on American Art 1945–1990 (Routledge, 2020, 2 volumes, edited with I.B. Whyte). She is the curator of the recent exhibition Romantic Spain: Genaro Pérez Villaamil and David Roberts (Madrid, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, 2021-2022) and the main author of the exhibition catalogue. Her monograph on Spanish attitudes to al-Andalus and Morocco in Spanish painting, 1833-1956, is forthcoming. She is Associate Editor of the Getty-funded journal Art in Translation.

Notes

1 AGA 81.15653.0001, AGA 81.15653.0003; AGA 81.15654.0001; AGA 81.1564.0004; 81.15655.0003.

2 The article has developed from two conference papers (1) ‘Al-Andalus at the Painters of África exhibitions’ at Artistic Heritage of al-Andalus and National Identity, Humboldt University, Berlin, October 2017, published by the Justi Vereinigung in 2019/20 (Hopkins Citation2019/20). (2) ‘Moroccan Perspectives’ at the Challenging Orientalism panel, organised by Emily Christensen and Emma Payet at the Association of Art Historians conference, April 2021. The translations are mine, unless otherwise stated. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

3 Castro’s idealised vision of the past contrasted with the alternative view of history, proposed by Claudio Sánchez Albornóz, who regarded the presence of Muslims and Jews in medieval Spain as a mere interlude with no major consequence for the ‘essence’ of Spain (Sánchez Albornóz Citation1956).

References

- Archival sources:

- Archivo General de la Administración (AGA), Alcalá de Henares:

- AGA 81.15653.0001

- AGA 81.15653.0003

- AGA 81.15654.0001

- AGA 81.15655.0003

- Published sources:

- Antolín Paz, Mario. 1994. Diccionario de pintores y escultores españoles del siglo XX. Madrid: Forum Artes.

- Areán, Carlos. 1967. “La Escuela de Tetuán en Madrid.” In Escuela de Tetuán, Homenaje a Bertuchi. Publicaciones españolas cuadernos de arte. Serie divulgación ciclo de arte hispano-marroquí. Madrid.

- Arrarás Iribarren, Joaquín. 1939–1943. Historia de la cruzada española. Madrid: Ediciones Españolas. 8 volumes.

- Arias Anglés, Enrique. 2007. “La visión de Marruecos a través de la pintura orientalista epsañola.” In Mélanges de la Casa de Velázquez, edited by Helena de Felipe, 13–38. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez.

- Asín, Miguel. 1940. “Por qué lucharon a nuestro lado los musulmanes marroquíes.” Boletín de la Universidad Central de Madrid (separata), 1–25.

- Bacaicoa Arnaiz, Dora. 1967. “Gestación de la Escuela de Tetuán.” In Escuela de Tetuan, Homenja a Bertuchi. Publicaciones españolas cuadernos de arte. Madrid: Serie divulgación ciclo de Arte Hispano-Marroquí.

- Bolorinos Allard, Elisabeth. 2017. “Visualizing ‘Moorish’ Traces within Spain: Orientalism and Medievalist Nostalgia in Spanish Colonial Photojournalim 1909-1933”. Art in Translation 9 (1): 114–133.

- Borja-Villel, Manuel. 2021. “Umbrales.” In Trilogía marroquí, edited by Manual Borja-Villel, and Abdellah Karoum, 15–18. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

- Bouzaid, Bouabid. 2013. “Centre d’Art Moderne de Tétouan. Discours et parcours muséologique.” In Centro de Arte Moderno de Tetuán, edited by Eduardo Dizy Caso, Bouzaid Bouabid, Clara Miret Nicolazzi, Moulim El Aroussi, Julio Malo de Molina Martín-Montalvo, and María Victoria Ridrúgyez Machuca, 13–16. Tetouan: Centro de Arte Modern de Tetuán.

- Calderwood, Eric. 2014. “‘In Andalucia There are no Foreigners’: Andalucismo from Transperipheral Critique to Colonial Apology.” Journal of Spanish Studies 15 (4): 399–417.

- Calderwood, Eric. 2018. Colonial Al-Andalus: Spain and the Making of Modern Moroccan Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Camón Aznar, José. 1956. “Exposición de Pintores de Africa en el salón del Círculo de Beellas Artes.” ABC (Madrid), 14 March 1956, 47.

- Carabias, Josefina. 1954. “Pintores de África” [Informaciones, 27 March 1954]. In Quinta exposición de pintores de África, 121–122.

- Catálogo de la exposición y talleres del pabellón de Marruecos. X Feria oficial de muestras internacional Barcelona. 1942. Barcelona: Imp. Altés.

- Catálogo de la VII Exposición de Pintores de Africa. 1956. Madrid: Dirección General de Marruecos y Colonias, Instituto de Estudios Africanos (CSIC).

- Castro, Américo. 1948. España en su historia. Cristianos, moros y judíos. Buenos Aires: Editorial Losada.

- Cobos, Antonio. 1956. Alta calidad artística en la VII exposición de pintores de África.” Ya 7 (9 Mar 1956).

- Cuarta exposición de pintores de África. 1953. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Díaz de Villegas, José. 1954. “Palabras del Excmo Sr Don José Díaz de Villegas.” In Quinta exposición de pintores de África, 165–167. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Durán Díaz, Maria Dolores. 1981. Historia y estética del movimiento indaliano. Almeria: Cimal.

- “El protectorado español de Marruecos bajo la comisaría Garcia-Valiño.” Fotos (San Sebastian). 1953.

- Francés, José. 1951a. “Fortuny y la pintura africanista.” In Primera exposición de pintores de África, 7–27. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Francés, José. 1951b. “Nostalgia y promesa de lo Africano.” In Segunda exposición de pintores de África, 49–58. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Francés, José. 1956. “Apostillas a la VI Exposición de Pintores de África.” Archivo del Instituto Estudios Africanos, xx–xx.

- Figuerela Ferreti, Luis. 1954. “Quinta exposición de pintores de África” [from: Arriba, 4 April 1954]. In Quinta exposición de Pintores de África, 131. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Gil Benumeya, Rudolfo. 1943. Marruecos Andaluz. Madrid: Cultural Hispánica.

- Gil Benumeya, Rudolfo. 1951. “Pintores de África en Madrid.” In Primera exposición de pintores de África, 113–115. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Gil Benumeya, Rudolfo. 1953a. “Pintura española del Magreb y pintura magrebí de España.” In Cuarta exposición de pintores de Africa, 85–87. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Gil Benumeya, Rudolfo. 1953b. “Madrid ante la IV exposición de pintores de África” [Radio Nacional de España. Translated from Arabic into Spanish].” In Cuarta exposición de pintores de Africa, 89–91. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Gil Benumeya, Rudolfo. 1953c. Hispanidad y Arabidad. Madrid: Cultural Hispánica.

- Goderque, F. G. 1953. “Impresiones de la III exposición de pintores de África en Madrid.” In Tercera exposición de pintores de África, 111–113. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Gómez Barceló, José. 2009. “La enseñanza de las Bellas Artes en el Protectorado.” In Ceuta y Protectorado español en Marruecos, IX Jornadas de Historia de Ceuta, 121–149. Ceuta: Instituto de Estudios Ceuties.

- Guillot Carratala, J. 1953. “La IV Exposicion de Pintores de Africa.” In IV exposición de pintores de África, 73–76. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Hopkins, Claudia. 2017. “The Politics of Spanish Orientalism. Distance and Proximity in Tapiró and Bertuchi.” Art in Translation 9 (1): 134–167.

- Hopkins, Claudia. 2019/20. “Al-Ándalus at the Pintores de África Exhibitions.” In Mitteilungen der Carl Justi-Vereinigung, edited by S. Hänsel and B. Marten, no. 31/32, 93–102. Münster: Nodus.

- Jensen, Geoffrey. 2005. “The Pecularities of Spanish Morocco Imperial Ideology and Economic Development.” Mediterranean Historical Review 20 (1): 81–102.

- Jiménez-Blanco, María Dolores, ed. 2016. Campo Cerrado. Arte y poder en la posguerra española (1939–1953). Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia.

- Jimenez Valiente, María Dolores. 2018. “La Escuela pictórica de Tetuán: Historia, desarrollo e imprenta del arte marroquí contemporáneo.” PhD Dissertation. Universidad de Alicante.

- Karroum, Abdellah. 2021. “Trilogía marroquí.” In Trilogía marroquí, edited by Manuel Borja-Villel, and Abedellah Karoum, 19–32. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

- Larrea Palacín, Arcadio. 1960. “Antigua música española en el Norte de Africa. Conferencia pronciuado con motiva de la IX Exposición de Pintores de África, 8 de marzo 1958, Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid.” Archivos de Instituto de Estudios Africanos 52: 33–42.

- “Los artistas ‘africanos’”. 1969. Informaciones (Madrid), 20 March. Press cutting in AGA 81/15658, XIX Exposición de pintores de África.

- Madariaga, M. Rosa. 2002. Los moros que trajo Franco. La intervención de tropas coloniales en la Guerra Civil Española. Barcelona: Ediciones Martínez Roca.

- Madariaga, M. Rosa. 2015. “Confrontation in the Spanish Zone (1945–56): Franco, the Nationalists and the Post-War Politics of Decolonization.” Journal of North African Studies 19 (4): 490–500.

- Martín Corrales, Eloy. 2007. “Marruecos y los marroquíes en la propaganda official del Protectorado (1912–1956).” In Mélanges de la Casa de Velázquez, edited by Helena de Felipe, 83–107. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez.

- Martin Márquez, Susan. 2008. Disorientations. Spanish Colonialism in Africa and the Perfomance of Identity. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Mateo Dieste, Josep Lluís. 2003. La ‘hermandad’ hispano-marroquí. Política y religión bajo el Protectorado español en Marruecos 1912–1956. Barcelona: Bellaterra.

- Mateo Dieste, Josep Lluís, and Nieves Muriel García. 2020. A mi querido Abdelaziz … de tu Conchita. Cartas entre españoles y marroquíes durante el Marruecos colonial. Barcelona: Icaria.

- Morales Oliver, Luis. 1953a. “Lo africano en la prosa literaria española.” In Tercera exposición de pintores de África, 29–44. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Morales Oliver, Luis. 1953b. “Lo africano en la poesia española.” In Tercera exposición de pintores de África, 61–75. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Morales Oliver, Luis. 1954. “Conferencia pronunciada por el Illmo. Sr. Don Luis Morales Oliver.” In Quinta exposición de pintores de África, 39–50. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Muller, Nicolás. 1944a. Estampas marroquíes. Cién Fotografías de Nicolas Muller. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Políticos.

- Muller, Nicolás. 1944b. Tánger por el Jalifa. Reportaje gráfico de Nicolás Muller. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos.

- Museo de Ceuta. 2007. Escuela de Tetuán: 50 años de reflexión: A. Amrani, R. Ataallah, S. Ben Cheffaj, M. Megara. Exhibition catalogue. Ceuta: Museo de Ceuta, Revellín de San Ignacio, Conjunto Monumental de las Murallas Reales.

- Ovejero, Andrés. 1951. “El tema de África en nuestra pintura.” In Primera exposición de pintores de África, 29–53. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- “Pintores de Africa.” 1956. Domingo, March 11.

- Pleguezuelos Sánchez, José Antonio. 2013. Mariano Bertuchi. Ceuta: UNED de Ceuta.

- Pleguezuelos Sánchez, José Antonio. 2011. José Cruz Herrera. Malaga: Editorial Sarriá.

- Preston, Paul. 1993. Franco. A Biography. London: Harper Collins.

- Primera exposición de pintores de África. 1951. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Sánchez Albornóz, Claudio. 1956. España: un enigma histórico. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana.

- Tomás, M. 1953. “III Exposición de pintores de África en el Círculo de Bellas Artes.” In Tercera exposición de pintores de África, 97–99. Madrid: Insituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. 1954. “Unidad artística de Al-Andalus y Berbería en el siglo XII. Expansión del arte andaluz.” In Quinta exposición de pintores de África, 51–73. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Sarghini, Mohamed. 1989. “La Escuela de Tetuán.” In Pintores marroquíes de la Escuela de Tetuán. I Encuentro de intelectuales magrebíes de expresión española. Marrakesh.

- Sauret Guerrero, Teresa. 2019. “Las exposiciones ‘Pintores de África’, y la redefinición del concepto del catálogo.” Quiroga 15: 72–81.

- Segunda exposición de pintores de África. 1951. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Vega, José María. 1951. “Africa an la pintura española.” In Primera Exposición de Pintores de África, 80. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- Varón, O. 1951. “La II Exposición de Temas Africanos.” In Segunda exposición de pintores de Africa, 126. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Africanos.

- 9 Discipulos de Bertuchi. 2000. Tetouan: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes.

- Zahi, Farid. 2004. “Vision en partage”. In Abdelkrim Ouazzani, Younès Rahmoun, Safaa Erruas, Hassan Echair. La nueva escuela de Tetuan. Cuenca: Diputación de Cuenca. Fundacion Antonio Pérez.