Abstract

Histories of Orientalist photography focus predominately on the form and content of positive prints. This article argues that more attention should be paid to the distinctive visual qualities and associated meanings of photographic negatives within the colonial visual encounter. Paper and glass-plate negatives were the objects of frequent spectatorship and discussion for travelling British photographers working ‘in the field’ in the early years of the medium. While scholarship on such photography has traditionally emphasized the camera’s capacity to ‘fix’ the racialized Other as a static image available for the imperial gaze, the actual practice of making photographs ‘in the field’ was defined by fluid chemical processes and the fragile materiality of sensitized plates. I argue that such procedures yielded negative images that were defined not so much by fixity as mutability. The distinctive blemishes and marks that appeared on such negatives were read by photographers as indexes of volatile chemical and climatic agencies that decentered photographic authorship. Attending to photographers’ writings on such visual traits thus reveals a counter-discourse to the standard language of stasis and instantaneity that has come to dominate accounts of photography.

Introduction

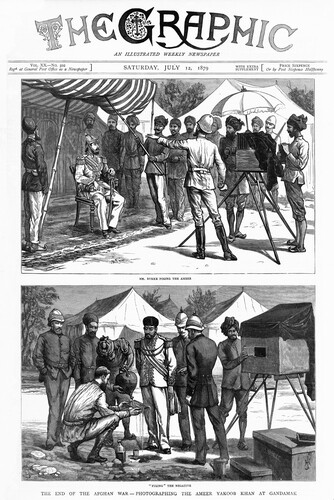

In 1879, The Graphic ran a front-page illustration () showing the Emir of Afghanistan peering at his portrait as it emerges from a wet-collodion negative prepared by a colonial photographer. A fixing solution is being poured over the light-sensitive film of the glass-plate, running over a nascent image. Photography is thus not encountered as a fully developed positive print with a clear representational content. It is something inchoate, an active and ongoing chemical process. By highlighting the temporality of the photographic event, the two-part scene serves as what W. J. T. Mitchell terms a ‘meta-picture’, inviting Victorian viewers to reflect on the nature of photographic image-making (Mitchell Citation2013, 10). This was how such Orientalist portraiture was often witnessed by those who encountered the camera ‘in the field’: a series of theatrical, technical and chemical procedures involving the preparation, exposure, developing, fixing, rinsing and varnishing of a negative, during which the intended final product, the positive, remained absent.

Figure 1. Frederic Villiers, ‘Mr Burke Posing the Ameer’ and ‘“Fixing” the Negative’, The Graphic, 12 July 1879, cover. © Mary Evans Picture Library.

Negatives, however, are seldom written about in any detail by historians of colonial visual culture and they are illustrated only rarely within the wider historiography of photography. Scholarship has overwhelmingly prioritized the representational clarity of the positive print. It is important to attend to colonial negatives at this time, however, because they are currently being used to invite a renewed formalist enjoyment of nineteenth-century Orientalist photography, the latest iteration of what Ali Behdad, in reference to a series of exhibitions in the 1990s, has termed ‘curatorial Orientalism’ (Behdad Citation2016, 8; Behdad & Gartlan Citation2013, 8). Linnaeus Tripe’s paper negatives of Indian and Burmese architecture, made in the 1850s and held by the V&A, and John Thomson’s glass-plate negatives of anthropological ‘types’ in China and Southeast Asia, produced in the 1860s and 70s and held by the Wellcome Library, have both been used as resources to develop colonial photography in a manner that rehabilitates it as a site of aesthetic appreciation. In recent years viewers have been encouraged to enjoy the ‘beauty’ of the artefacts’ distinctive visual features, like blemishes, cloudiness and cracks. Negatives were sometimes peppered with visual traits that were considered extraneous or undesirable, serving as a bar to the intended representational content of the image. Yet these errant marks were also crucial aspects of the phenomenology of photography for practitioners and were seen to convey significant information about the ecologies of photographic production.

This article offers a brief account of such visual traits and the formal and material qualities of negatives more broadly. It asks what these artefacts might reveal about the image-making process that their positive counterparts do not. Attending to negatives means understanding photography not so much in terms of the documentary detail that many Victorians tended to prize about the medium, but through the haziness of latency; not in terms of the various discursive and archival contexts that comprise the ‘social biography’ of prints, but via the chemical and climatic flows that inscribed themselves in the materiality of a negative; and not in terms of the stasis and instantaneity often associated with photographs, but through the ‘durations’ (Knight and McFayden Citation2020, 55) that inhered in the complex and delicate procedures of photographic production in the imperial field. In the foggy and blemished surface of a negative, racialized subjects and colonized lands appeared ‘through a glass, darkly’. Obscurity of this sort challenges the dominant metaphors used to describe photography – a medium conceived in terms of transparency, detail and light.

Travelling Victorian photographers understood photography in terms of mysterious chemical and environmental agencies. ‘[H]ow much photographers are indebted to sunshine as a great chemical agent’, wrote Thomson, ‘of the exact nature of whose properties we are so ignorant’ (Thomson Citation1866c, 436). Negative in particular were defined by sensitivity and reactivity, whereby labile images developed in dynamic response to chemicals, climate and technique. In her account of the early conceptual vocabulary of the medium, Vered Maimon describes the Victorian sense of witnessing ‘an unregulated temporal “encounter” between light and a sensitive surface whose outcome cannot be fully predicted’ (Maimon Citation2015, 121). The aesthetic qualities of the negative were not fixed, nor were they seen to be determined solely by authorial design. ‘Photography’, as Lady Eastlake put it in an 1857 essay, ‘is, after all, too profoundly interwoven with the deep things of Nature to be unlocked by any given method’ (Eastlake Citation1857).

All of which sits uneasily within the traditional metaphysical system of the humanities, whereby artistic materials are viewed as fundamentally inert stuff until they are shaped into meaningful form by the intentions and skillful handling of an authorial figure – a conceptual framework that the anthropologist Tim Ingold calls the ‘hylomorphic’ model of material culture (Ingold Citation2013, 21). This kind of traditional materialist perspective is inadequate for describing the colonial experience of creating photographs in the field. I thus draw on the ecocritical conceptual apparatus of new materialism in order to suggest that working with photosensitive compounds in unfamiliar climates prompted in colonials a keen awareness of the environmental elements shaping the image-making process. To look with an ‘ecological eye’ (Patrizio Citation2019, 17) is not to locate photographic content that was explicitly ecological in its focus – landscapes, botany, and so on – but a means of becoming attuned to the nonhuman agencies that constitute the very tissue of these images.

Ecocritical theoretical perspectives can help reframe conventional readings of the Orientalist encounter. Instead of the binary confrontation between colonial subject and racialized other that results in a document of the latter authored by the former, a more complex picture develops. In a recent article on nineteenth century survey photography in the American West, Elizabeth Hutchinson writes of a ‘distribution of responsibility’ (Hutchinson Citation2020, 3) for photographic production that encompasses not only socio-political circumstances but the ecological conditions in which photographs are able to be made and which determine their visual qualities: light, temperature, humidity, pressure, altitude, dust and pollution, not to mention the production or extraction of photographic materials like eggs, glass and silver in the first place. Such conditions were just as important to colonial photography as the panoptic fantasies and Hegelian ‘master-slave’ power struggles that have been fundamental to postcolonial understandings of Orientalist visual culture. While scholarship on colonial photography has traditionally emphasized the camera’s capacity to ‘fix’ the racialized Other as a static image available for the imperial gaze, the actual practice of making photographs ‘in the field’ was defined by fluid chemical processes. As The Graphic scene shows, working with negatives in the mid nineteenth century involved moments of relative authorial passivity – a ‘structure of waiting’ (Moskatova Citation2017, 116) that was constitutive of photographic temporality in the field, whereby the photographer, their subject and other onlookers became spectators of the autogenic world of photosensitive materials.

Historiography of negatives

Writing of colonial photographs of Tibet, Elizabeth Edwards characterized the negative as ‘perhaps the primary document’ of photography, for it is ‘the negative which captures the light reflected off an object, passing through the aperture of a camera to be held and stilled on light sensitive chemicals spread across a support of glass or film’. Yet, unlike the materiality of the positives which Edwards’ work has analyzed in depth, this primary document is afforded limited aesthetic resonance or semantic substance: ‘While the moment of inscription or exposure on the negative carries with it the authenticity of the moment, the sense of meaning created through the use of photographs emerges from the moment those negatives are first printed’ (Edwards Citation2003, 133). This privileging of the print is representative of the majority of scholarship on photography, which, not unreasonably, has gravitated towards the positives that tended to be chosen by photographers for publication, exhibition and dissemination, and which consequently circulated far more widely than the singular negatives upon which they were based. When one confronts photography, observed the theorist Vilhelm Flusser, ‘significance appears to flow into the complex [the camera] on the one side (input) in order to flow out on the other side (output), during which the process – what is going on inside the complex – remains concealed: a “black box” in fact’ (Flusser [Citation1983] Citation2005, 16).

Negatives, then, as Geoffrey Batchen recently put it, are part of the ‘repressed, dark’ side of photography’s history (Batchen Citation2020, 3). Yet there have been some scattered attempts to grapple with the visual politics of the negative/positive process, which was historically conceived in terms of a racialized metaphysics of darkness and light. In her archival work on Black British photography, Tina M. Campt noted how attending to the inversions of tone in negatives defamiliarizes the usual dermatological markers of race and reveals the extent to which, ‘even when race seems clearly visible in a photographic print, its visuality is the creation of technical, material, and cultural processes of conjuring and fixing’ at the negative stage (Campt Citation2012, 128, emphasis added).

A similar argument is made by Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby in her 2011 article ‘Negative–Positive Truths’ with reference to antebellum American photography. When it came to the racially charged tonal values of early black and white photographs, she writes, ‘compromises and losses [of visual-racial information] are built into its procedures as well as its results’ (Grigsby Citation2011, 23). Skin tone was to a large extent the effect of (white) authorial choices made regarding exposure and development of the negative; and such choices required a trade-off between light and dark tones, whereby an adequate exposure for darker complexions meant the overexposure and thus loss of information for paler skin, and an appropriate exposure for lighter skin meant the underexposure and consequent loss of information about darker complexions. Grigsby (Citation2011) argues that bringing the negative into the frame enables a view of photography that, contrary to naive Barthesian photographic realism (‘this has been’), points towards racial difference as something that is at stake within the authorial decisions and chemical reactions at the negative stage of the practice.

The racial stakes of the negative/positive process were not lost on Victorian practitioners. Scholars have noted bountiful instances of early writing on the medium in which ‘the relationship between the negative and the positive is both morally loaded and racially inflected, semantically infused with difference and prejudice’ (Batchen Citation2020, 7). The man who first proposed that the terms ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ should be used to denote the respective stages of the photographic process, Sir John Herschel, wrote in his diary that, in a negative, ‘fair women are transformed into negresses’ (quoted in Batchen Citation2020, 7). And when, in 1866, the travelling Scottish photographer John Thomson published a series of articles in the British Journal of Photography on the titular theme of ‘Practical Photography in Tropical Regions’, he duly framed his advice in terms of securing the integrity and legibility of race. He warned that unless colonial photographers were careful with their chemical techniques, then people back in Britain receiving portraits of loved ones from the East would believe their relatives ‘must have grown black out in that horrid place, and turned Hindoo or Chitty’ (Thomson Citation1866a, 360).

The verisimilitude of photography in the imperial field was thus dependent on its ultimate ability to recuperate recognizable forms of whiteness. The documentary integrity of photography required such racial legibility; ‘(pictorial) truth is restored when white is finally once again white, and dark is once again dark (after a temporary disorienting inversion)’ (Grigsby Citation2011, 21). The binary terms of photography (black/white, negative/positive) thus buttressed nineteenth-century conceptions of racial difference even as the messy realities of photographic processes stoked anxieties about the dissolution of those very racial boundaries.

Viewing negatives ‘in the field’

The method of conducting visual study ‘in the field’ was not an ideologically neutral means of knowledge-production but contained an implicit hierarchy. It involved, as Johannes Fabian puts it, ‘the enactment of power relations between societies that send out fieldworkers and societies that are the field’ (Fabian [Citation1983] Citation2014, 122). The images produced under such circumstances worked to shore up a subject-object divide between colonial photographers and those subjected to their ‘ethnographic surveillance’ (Richards Citation1993, 21). Yet such observation was by no means unidirectional; those conducting the visual fieldwork of empire sometimes felt they were ‘more spectacle than spectators’ (Grant Citation1856, 15).

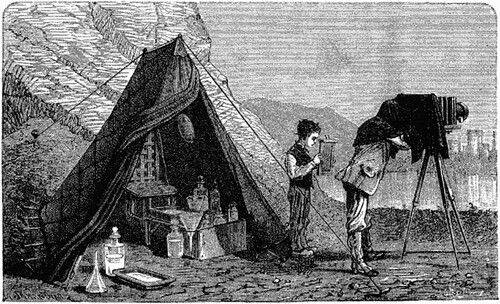

This sense of being the object of another’s gaze is unsurprising given the extensive equipment and elaborate techniques required of early photographic image-making. In 1851, Frederick Scott Archer invented the wet collodion process, which, in spite of its reliance on fragile glass plates, temperamental chemical procedures and on-site darkrooms, became highly popular with photographers working in the global field. This was the method for which Roger Fenton required his ‘photographic van’ during the Crimean War (1853–1856), a horse-drawn carriage that served as a storage space and darkroom in which the necessary chemical treatments could be made immediately before and after the exposure of the glass-plate negative. The more common practice was to use a travelling tent ().

Figure 2. Gaston Tissandier, ‘Photography and Exploration’, History and Handbook of Photography, 1876, wood engraving. © National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

During his time in Southeast Asia and China, Thomson became a great proponent of the new collodion method, insisting on the viability of the process outdoors ‘providing the chemicals are modified to suit the climate’ (Thomson Citation1866a, 380). Photographers were increasingly cognizant of the importance of various atmospheric factors, using thermometers, barometers and hydrometers to assess conditions of production; the American survey photographer William Henry Jackson wrote of waiting for days for favourable ‘photographic weather’ (Hutchinson Citation2020, 3). Even in good conditions, the collodion method was a tricky endeavour. Thomson described a lengthy and recursive practice in which the initial preparation and exposure of a glass negative was followed by an extended process of moving in and out of his darkroom tent. He preferred to conduct as many of his operations outside as was possible (Thomson Citation1866b, 404): ‘Tent work’, he wrote, ‘I consider to be the most unhealthy part of the photographer’s operation … You may work with your tent in the shade of the tree, and take every precaution you may for ventilating the interior, and yet, after ten minutes’ work, the rapid evaporation of your chemicals renders the air noxious’. Thus, following initial development in the darkroom, he described washing, fixing, re-washing, drying and eventually re-development all occurring ‘in broad daylight’, where he could ‘carefully watch the process of intensifying until it has reached the stage desired, when the picture may be washed, dried, and varnished (Thomson Citation1866d, 474). Even after varnishing, when ‘its character is supposed to be so settled that it is beyond the reach of alternative or improvement’, a negative could still be intensified through a tincture of iodine and spirit (Anon. Citation1866, 573). There was a plasticity to photography, a medium that was in fact frequently ‘unfixed’ by its users (Bajorek Citation2020, 22).

The negatives produced through such means were visible to onlookers at numerous points throughout the process and remained an object of interest. Thomson claimed that he had to lock his box of collodion negatives to stop curious locals sneaking a peek and leaving their ‘oily’ fingerprints on the glass, which would then come out in his prints as ‘indelible greasy thumbprints’ (Thomson Citation1866b, 404). Yet other colonials made a point of showing off their negatives to the peoples whose lands were being surveyed, treating this as a test of a population’s visual literacy. On a British imperial mission to Burma in 1855, one member told of how the Madras Army photographer Linnaeus Tripe was ‘immediately surrounded by a mob of monks and their pupils’ whenever he stopped to make photographic studies of architecture – producing images which, ‘though all remaining in the negative stage, appeared to be understood’ by the local crowds (Yule [Citation1856] Citation1968, 89). Fifty years later, a journalist accompanying the British invasion of Tibet in 1904 wrote of how the expedition’s official photographer, John Claude White, would show off his large-format glass negatives to curious onlookers, saying that ‘it was an unfailing source of mystification to the Tibetans to be allowed to look at the reversed picture in the ground glass under the black velvet’ (Landon Citation1905, 253). Yet the journalist claimed that these Tibetans did not comprehend the negatives, ‘It was for them merely a beautiful pattern of varying colors seen in a singularly effective manner’.

Such assignations of photographic illiteracy were common in colonial discourse and should be treated with caution. But it is worth remaining open to the particular visual strangeness of negatives. The translucency of a negative image invites an appreciation not just of its representational content but of its material support (paper, glass or celluloid), whereas the clarity of positive prints offer an ‘illusion of transparency’ as a window-on-the-world (Batchen Citation2020, 6). The ideal of the photographic image as an unmediated visual document is compromised by the spectral materiality of the negative plate. As the photographer Ingrid Pollard describes it, there is ‘a thingyness that you feel incredibly strongly when you work with negatives’ (Pollard, in Campt Citation2012, 128).

Crucially, many of the contextual factors that ultimately shaped understandings of positive photographic prints were undecided when a negative was encountered ‘in the field’. Important authorial interventions (cropping, retouching, printing, captioning) and sociohistorical factors (publication, circulation, display, reception) remained to be seen. Given that such contextual frames are now key to the standard hermeneutic strategies of photo-historians, how should we approach negative images that are defined more by potentiality than any determinate content or context? In conventional studies of material culture – whether they are working in Marxist, feminist, or postcolonial methodological traditions – the overwhelming focus has been on finished objects and their contexts. The artefact, in its apparent integrity, is read as a reflection, distortion or symptom of the social relations from which it emerged. ‘What is lost [in such an approach]’, writes Ingold, ‘is the creativity of the productive processes that bring the artefacts themselves into being: on the one hand the generative currents of the materials of which they are made; on the other the sensory awareness of practitioners’ (Ingold Citation2013, 7). To regard an artefact only in terms of its apparently fixed and finished state is to ignore the contingencies and ecologies inherent in the processes of its creation and the significance that accrued to those ephemeral processes for those who harnessed or witnessed them.

A cursory look at the nineteenth-century photographic press is sufficient to demonstrate that photographers themselves were obsessive about the particulars of those processes: ‘Too much care cannot be taken in dealing with the delicate and invisible impressions produced upon photographic films by vibrations of light’ (Harrison Citation1866, 498). So too was the process itself a crucial element of the medium’s visual impact and meaning for non-specialist audiences, as The Graphic front-page attests.

The artist who rendered that scene, Frederic Villiers, was a regular correspondent for the popular illustrated magazine and was not averse to self-promotion. Yet here he directs the attention of his audience away from his own professional practice of sketching ‘on the spot’ (as the parlance of the press had it) in order to report the drama of posing an Asian sovereign for the camera at a vexed moment of geopolitical transition. The scene works to conflate military conquest and photographic capture at the conclusion of a war. But the visual narrative also complicates the popular Victorian fantasy of the camera-as-cannon, in which photography figured as an explosive force. Villiers highlights the technical procedures of photography, portraying a delicate form of visual theatre in which the as-yet unfinished photographic negative becomes an object of cross-cultural spectatorship. The scene reveals what Lesley McFadyen and Dan Hicks, writing against the theme of instantaneity that has pervaded photo-historiography, have termed the ‘durational’ qualities of the medium (McFadyen and Hicks Citation2020, 7). As much as the caption to the lower scene raises the prospect of ‘fixity’, viewers are not shown a stable photographic image but a fluid and dynamic process of chemical treatment following the negative’s removal from a portable darkroom (the tripod structure seen on the right). The photographic image is inchoate, emerging from fluid processes of production.

Viewing the creation of photographic negatives was thus a fundamentally different type of experience from consuming positives. An interplay between visibility and concealment was key to the poetics of the negative. As Susan E. Cook notes in her book on its symbolism in Victorian fiction, the negative promises presence and yet simultaneously withdraws from presence (Cook Citation2019, xxviii). Latency and spectrality were a key part of the allure of this new form of image-making. In his oft-quoted 1863 essay ‘Doings of the Sunbeam’, the American writer Oliver Wendell Holmes described the drama of witnessing figures emerge on a negative plate:

… a ghost we hold imprisoned in the shield we have just brought from the camera. We open it and find our milky-surfaced glass plate looking exactly as it did when we placed it in the shield. No eye, no microscope, can detect a trace of change in the white film that is spread over it. And yet there is a potential image in it, – a latent soul, which we will presently appear before its judge … We pour on the solution. There is no change at first; the fluid flows over the whole surface as harmless and useless as if it were water. What if there were no picture there? Stop! What is that change of color beginning at the edge, and spreading as a blush spreads over a girl’s cheek? … and now the eyes come out from the blank as stars from the empty sky … (Holmes Citation1863, 240)

At this stage in photography’s history, then, neither the camera nor the portable darkroom were akin to Flusser’s ‘black box’, defined by the ‘impenetrability of its interior’. They were permeable spaces in which reactive chemicals, mutable materials and emergent images circulated in dynamic relationship to one another throughout various stages of manufacture. This would change with the invention and subsequent spread of the Kodak in 1888. The new technology meant that negatives were no longer a visible element of the photographic performance; they were hidden in a roll of film that needed to be sent off to the company to be processed and then returned to the customer as positive prints. In the era of collodion, though, negative were a site of ongoing authorial intervention on the basis of aesthetic judgement and were themselves a distinct source of visual enjoyment. ‘We use gelatine solution in the silver bath’, one Victorian photographer advised his peers in an article on the methods of working outdoors: ‘There is a beautiful bloom on the negative prepared in this way’ (Towler Citation1866, 478).

By the time negatives produced in the field became positive prints consumed in the imperial metropole, they tended to be weighed down by what Ali Behdad terms the ‘excessive anchorage’ of Orientalist discourse, which rendered the meaning of its photographs ‘univocal and flat’ (Behdad Citation2016, 31). Yet, contrary to such fixity, the negative itself was a dynamic visual artefact. The wet-collodion glass-plate process in particular had what Kaja Silverman, borrowing from Jeff Wall, terms a ‘liquid intelligence’, which made it fluid and ‘unpredictable’ (Silverman Citation2015, 75). In an intriguing reading, Silverman suggests that, while born of the phallic fantasy of the camera-as-weapon, the novelty cameras that were designed to actually look like guns, such as Thomas Skaife’s Pistolgraph from 1858, ultimately stimulated little consumer interest ‘because other aspects of chemical photography were still so “wet” – literally as well as metaphorically’. ‘Wetness’ here stands for an immersion in and receptivity to the world, as opposed to the ‘dry’ subject-object split of a Cartesian metaphysics that has traditionally informed scholarly accounts of the camera and the colonial gaze.

Something of the ‘wetness’ and unpredictability of early photography is still detectable in the blemished surfaces of surviving colonial negatives. These marks are artefacts of a photographic process that failed to always yield the straightforward window-on-the-world form of representation for which photography is best known. And it is precisely these kinds of non-mimetic marks and imperfections – which serve no representational function but attest to the photographic process itself, the reactivity and fragility of its materials – that has lately become the basis for a renewed aesthetic appreciation of Orientalist photography.

Negative marks, past and present

In 2018, the German photographer Thomas Ruff came across four boxes of Linnaeus Tripe’s waxed paper negatives produced in India and Burma in the 1850s and now held in the Victoria & Albert Museum (). He was ‘utterly captivated’ by the ‘haunting yet beautiful quality’ of the ethnographic studies of architecture that Tripe had produced on behalf of his employer, the English East India Company. Ruff was especially struck by the blemishes on these negatives, many of them showing ‘traces of mold, water damage, and even chemical mutation’ (Ruff Citation2019).

Figure 3. Linnaeus Tripe, Amerapoora, Mohdee Kyoung, 1855, waxed-paper negative. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London [rps.2721–2017].

![Figure 3. Linnaeus Tripe, Amerapoora, Mohdee Kyoung, 1855, waxed-paper negative. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London [rps.2721–2017].](/cms/asset/a7c03ab6-8f22-4f28-a3ae-300dc21514c4/rwor_a_2160007_f0003_oc.jpg)

In a commission for the museum, he enlarged the images and produced digital positives that emphasized these features (https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/tripe-ruff).Footnote1 Ruff’s interventions do not seek to recover the original appearance of the imagery. This is by no means a conventional project of conservation in which the debris of time is removed from an artefact to restore it to a notion of historical authenticity. Rather, it is open to what the art historian Alois Riegl termed the ‘age-value’ (Alterswert) of an artefact where, ‘as soon as the individual entity has taken shape (whether at the hands of man or nature), destruction sets in, which through its mechanical and chemical force, dissolves the entity again and returns it to amorphous nature’ (quoted in Fowler Citation2019, 9). It is not the representational content that Ruff is recovering but the texture of negatives whose deterioration is interpreted as what Serpil Oppermann terms ‘storied matter’ (Opperman Citation2016, 90). Attending to signs of damage and decay prompts an understanding of photography as the product of entangled ecological and technical milieus, whereby nonhuman processes produce a variety of visual and material effects in the image-object: fading from continuous chemical reactions to light; foxing caused by fungal growth; curling from moisture in the air.

Colonial photographers like Tripe were experimenting with novel forms of photosensitive image-making and were acutely aware that their results were not altogether stable and timeless as historic records. Tripe wrote of how the ‘unfavourable weather’ of Burma – its heat and humidity – presented particular difficulties for the photographic process and led to what he termed ‘defective photographs … he was working against time, and frequently with no opportunity of replacing poor proofs by better’ (Tripe Citation1857). From preparation to storage, the delicate material and chemical nature of the negative meant it was frustratingly susceptible to transformations as environmental factors and experimental concoctions of photographic liquids meant that images often continued to develop or degrade in unpredictable ways. The organic materiality of Tripe’s paper negatives constitutes a form of historic evidence in which, as Miles Ogborn writes on the ecology of archives, ‘the materials of remembrance are living, dying, and being devoured’ (Ogborn Citation2004, 240).

Partly owing to their inherent fragility, many negatives from this era have not survived. Yet those that have are increasingly subject to archival initiatives producing digital copies of these ‘storied’ objects. The Wellcome Collection, for example, has produced high-resolution scans (rendered as both digital negatives and positives) of its collection of John Thomson’s original glass-plate images. Life-size prints of such scans then went on to form the basis for a popular exhibition, ‘Through the Lens of John Thomson’, which has been on the road for more than ten years featuring in 26 global museums across Asia, Europe and America, hosting almost a million visitors.Footnote2 There are shades in the Thomson exhibition of the Museum of Modern Art’s famous ‘Family of Man’ show in New York from the 1950s (which also toured internationally), with large portraits encouraging an engagement predicated on the universal recognition of subjectivity among culturally diverse sitters – a show with a politically liberal charge. Thomson, as a video on the exhibition website tells us, ‘humanised otherwise “exotic creatures” for these westerners’. The digital versions of Thomson’s work encompass the entire glass plate, replete with signed and inscribed borders, accidental markings, and areas of damage. In this respect they invite a similar form of visual engagement to Ruff’s treatment of Tripe’s paper negatives. Both function to foreground, even fetishes, the delicate materiality and contingency of early photographic processes ().

Figure 4. John Thomson, A Manchu Bride, 1871, digital positive of original glassplate negative, 12.1 × 16.5 cm. Wellcome Collection, London.

In many ways these posthumous developments of Victorian-era negatives occlude the historicity of their respective late photographers’ oeuvres. Reviewing the Thomson exhibition, Stéphanie Hornstein wrote of how, ‘at this size, a format which would have been simply impossible for Thomson to achieve, it becomes difficult for the viewer to assess the photographs as anything other than aesthetic objects, making a critical eye harder to muster’. For a properly historical understanding of such photography, she suggests, viewers will ‘need to look beyond the gorgeously framed piece to the material context in which the original prints were imbricated’ (Hornstein Citation2018). Photographers like Thomson produced prints that favoured representational clarity; such visual documents were placed in the service of ethnographic taxonomies, not as art-objects on a gallery wall. At the exhibition, imperfections are aestheticized, emerging as romantic signs of a lost past. As Batchen (Citation2020, 144) points out with reference to other instances of creating new pictures from a deceased photographers’ negatives, the resulting pictures ‘float free from any of the particular technologies, political contexts, or aesthetic preferences evidenced in the photographer’s own working life’.

Indeed, visual blemishes were originally interpreted in terms of failure or ruin. ‘I must impress upon you that you cannot get a good warm tone in a print unless you have a good negative’, wrote the photographer Osmund R. Green in 1866: ‘The negative should be vigorous and clear … Many of the negatives which I have seen at our meetings are feeble … ’ (Green Citation1866, 520). Clarity was the ideal because it allowed the representational content of the image to shine forth without any distracting visual traits exposing the mediated nature of the document. However, such marks were not meaningless to photographers They were signatures of production that attested to the tempestuous nature of chemical processes, the influence of climate and the nuances of authorial technique.

The photographic press of the time sustained a detailed discourse about how to recognize and resolve different forms of such markings – to understand, that is, ‘how matter matters’ as an ‘active participant’ within the image-making process (Barad Citation2003, 803). Here are a few examples from over a few months in 1866 in which photographers discussed the practicalities of working ‘in the field’:

On one occasion we forgot to filter the silver solution, and the next morning every negative was spoiled with a deposit of specks of reduced silver on the upper part of each plate (Towler Citation1866, 479)

I perceived my pictures almost invariably begin to fog as soon as I began to strengthen them with [the developer] pyrogallic acid … I saw at once the cause of my troubles … [The tent] had lately had several soakings in the rain, the effect of which had been to wash out a great part of the native yellow dye, which of course, left it pervious to actinic light. (Bourne Citation1866a, 499)

I discovered to my horror that some five or six of the very best negatives had cracked (that is, the varnished films), like a piece of network, all over … I at first attributed it to the varnish, but am now convinced that it arose from damp depositing on the surface, and then, while perhaps in a closed box, being carried in the sun or subjected to a higher temperature. (Bourne Citation1866b, 618)

The negative, then, did not simply convey the empty geometrical space of Cartesian perspective that is often associated with positive prints. It could also register aspects of the ‘ambient’ environment itself, a palpable atmosphere that imprints itself on the sensitive surface of the plate. Ambience, as Morton (Citation2007, 55) sees it, appears to exist in between the opposing entities of subject and object, ‘glimpsed as a fleeting, dissolving presence that … cannot be brought front and centre’. Rather than being conveyed representationally as ‘ecomimesis’ (Morton Citation2007, 35), the ambient atmosphere was transmuted into the visual static and tonal range of a negative image, leaving material traces that photographers often saw as symptoms of an excessive environmental intrusion that needed to be diagnosed and controlled.

Conclusion

Art historical accounts of Orientalist imagery have often defined themselves in opposition to ‘curatorial’ and ‘formalist’ approaches. The first major intervention in art historical scholarship – Linda Nochlin’s Citation1983 polemic against nineteenth-century French Orientalist oil painting – was catalyzed by an exhibition that, to Nochlin’s mind, elevated formal considerations over historical context and political critique (Nochlin Citation1983). More recently, Behdad has similary criticized ‘the museum curators’ formalistic and aestheticised approaches to photographic representations of the Middle East [which] disavow the political aims and cultural implications [of photographs]’ (Behdad Citation2016, 31). At the conference panel on which this special issue was based, many of the talks, including mine, involved some form of critique of exhibitions.

It would be easy enough to subject the above material to such a reading, pitching aesthetic surface (allegedly favoured by curators) against historical depth (triumphantly claimed by the academy). After all, as seen above, the work of both Tripe and Thomson has recently been reframed through digital interventions that invite forms of aesthetic engagement that do not dwell for long on the political significance of such images within the colonial contexts from which they emerged and in which they circulated. But these interventions complicate a too-easy binary between surface and depth because they are rooted in archival practices that recuperate repressed signatures of photographic production. These signatures were a constitutive feature of the colonial photographic experience, both in the field and within the pages of specialist journals that sought to understand their causes. If understood historically, rather than anachronistically framed as aesthetically pleasing artistic traits (as if these colonial photographers were all budding modernists experimenting with the artifice of their medium), then the speckling and blemishes of negatives invite a ‘posthumanist approach’ that enables new ways of thinking about Orientalist photography as the product of entangled and ongoing ‘natural’ and ‘cultural’ processes (Hutchinson Citation2020, 3).

My reading, too, might be critiqued for its formalism. Scholarship on material culture often involves a ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’, whereby an artefact’s surface-effects are exposed as the organ of deep political structures – an ‘organicist’ loop that exchanges one form of integrity (aesthetic or formalist) for another (ideological closure or historical totality) (Griffiths and Kriesel Citation2020, 5). I have barely touched upon the relationship of these images to the colonial political systems and discourses of the era; instead, I have embraced what might be considered a fairly superficial and overly technical reading of the photographic process, tarrying with the incidental surface effects of the colonial photographic encounter and saying little about the meaning of these images in terms of their originally intended function as visual mimesis produced in the service of imperial ethnographic taxonomies.

I have written in greater depth elsewhere about the political significance of such representations (Willcock Citation2021). With some types of pictures, however, ‘we cannot get as quickly from the slurry of marks to orderly historical meanings’, cannot move seamlessly from the indexical ‘babble’ of the surface to the world of transparent representational ‘signs’ (Elkins Citation1995, 824). Negatives do not only reveal a socially constructed world of coded representations circulating within an ideological system. Other agencies impinge, visible as stray marks and decomposition, visual stutters within the intended content of the image, lacunae within the codes of colonial photography.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sean Willcock

Sean Willcock is Departmental Lecturer in the History of Art in the Department for Continuing Education at the University of Oxford, where he is Course Director for the Undergraduate Certificate and Diploma in the History of Art. He was previously a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London, and has held teaching positions at the Savannah College of Art and Design, Hong Kong, and on the Yale in London programme. He is Reviews Editor at the journal History of Photography. His first book, Victorian Visions of War and Peace: Aesthetics, Sovereignty and Violence in the British Empire, was published with Yale University Press and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art in 2021.

Notes

1 Thomas Ruff after Linnaeus Tripe, Amerapoora, Mohdee Kyoung, 2018. C-type print. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/tripe-ruff).

2 I went to see ‘China and Siam: Through the Lens of John Thomson’ at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS, London (12 April – 22 June 2018). For a full list of venues from 2009 to the present, see: <http://www.johnthomsonexhibition.org/venues> (22 August 2018).

Bibliography

- Anon. 1866. “How to Intensify Negatives after They are Varnished.” British Journal of Photography, November 30: 573.

- Bajorek, Jennifer. 2020. Unfixed: Photography and Decolonial Imagination in West Africa. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Barad, Karen. 2003. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28: 801–831. https://doi.org/10.1086/345321

- Batchen, Geoffrey. 2020. Negative/Positive: A History of Photography. London and New York: Routledge.

- Behdad, Ali. 2016. Camera Orientalis: Reflections on Photography of the Middle East. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Behdad, Ali, and Luke Gartlan, eds. 2013. “Photography's Orientalism: New Essays on Colonial Representation.” Getty Publications.

- Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bourne, Samuel. 1866a. “‘Narrative of a Photographic Trip to Kashmir (Cashmere) and Adjacent Districts’, II.” British Journal of Photography 14 (337): 498–499.

- Bourne, Samuel. 1866b. “‘Narrative of a Photographic Trip to Kashmir (Cashmere) and Adjacent Districts’, IV.” British Journal of Photography 14 (347): 617–619.

- Campt, Tina M. 2012. Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Cook, Susan E. 2019. Victorian Negatives: Literary Culture and the Dark Side of Photography in the Nineteenth Century. New York: SUNY Press.

- Eastlake, Elizabeth. 1857. “Photography.” The London Quarterly Review 101 (April 1857): 442–468. http://www.nearbycafe.com/photocriticism/members/archivetexts/photohistory/eastlake/eastlakephotography1.html.

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 2003. “Some Thoughts on Photographs as History.” In Seeing Lhasa: British Depictions of the Tibetan Capital, 1936-1947, edited by Clare Harris, and Tsering Shakya, 127–140. Chicago: Serindia Publications.

- Elkins, James. 1995. “Marks, Traces, Traits, Contours, Orli, and Splendores: Nonsemiotic Elements in Pictures.” Critical Inquiry 21 (4): 822–860. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344069

- Fabian, Johannes. [1983] 2014. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Flusser, Vilém. [1983] 2005. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. London: Reaction Books.

- Fowler, Caroline. 2019. “Technical Art History as Method.” Art Bulletin 101 (4): 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2019.1602446

- Garascia, Ann. 2019. “‘Impressions of Plants Themselves’: Materializing Eco-Archival Practices with Anna Atkins’s Photographs of British Algae.” Victorian Literature and Culture 47 (2): 267–303. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1060150318001511

- Grant, Colesworthy. 1856. “Notes Explanatory of a Series of Views taken in Burmah during Major Phayre’s Mission to the Court of Ava in 1855.” Unpublished manuscript, British Library, London, pdp/wd540.

- Green, Osmund R. 1866. “On Printing and Mounting Photographs.” British Journal of Photography, November 2: 520.

- Griffiths, Devin, and Deanna K. Kriesel. 2020. “Introduction: Open Ecologies.” Victorian Literature and Culture 48 (1): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1060150319000470

- Grigsby, Darcy Grimaldo. 2011. “Negative-Positive Truths.” Representations 113 (1): 16–38. https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2011.113.1.16

- Harrison, William H. 1866. “Practical Photographic Suggestions.” British Journal of Photography, October 19: 497–498.

- Holmes, Oliver Wendell. 1863. “Doings of the Sunbeam.” The Atlantic 1863: 1–15.

- Hornstein, Stéphanie. 2018. “Exhibition Review: John Thomson at SOAS’s Brunei Gallery.” http://britishphotohistory.ning.com/profiles/blogs/exhibition-review-john-thomson-at-soas-s-brunei-gallery?overrideMobileRedirect=1.

- Hutchinson, Elizabeth. 2020. “‘Photographic Weather’: A Posthumanist Approach to Western Survey Photography.” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6 (2). https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10862.

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London & New York: Routledge.

- Knight, Mark, and Lesley McFayden. 2020. “‘At Any Given Moment’ Duration in Archaeology and Photography.” In Archaeology and Photography: Time, Objectivity and Archive, edited by Lesley McFadyen, and Dan Hicks, 55–72. London, New York, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

- Landon, Perceval. 1905. The Opening of Tibet: An Account of Lhasa and the Country and People of Central Tibet and of the Progress of the Mission Sent There by the English Government in the Year 1903-4. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co.

- Maimon, Vered. 2015. Singular Images, Failed Copies: William Henry Fox Talbot and the Early Photograph. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McFadyen, Lesley, and Dan Hicks. 2020. “Introduction: From Archaeography to Photology.” In Archaeology and Photography: Time, Objectivity and Archive, edited by L. McFadyen, and D. Hicks, 1–20. London, New York, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 2013. What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Morton. 2007. Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press.

- Moskatova, Olga. 2017. “In the Event of Non-Happening: On the Activity and Passivity of Materials.” In State of Flux: Aesthetics of Fluid Materials, edited by Marcel Finke, and Friedrich Weltzien, 105–120. Berlin: Reimer.

- Nochlin, Linda. 1983. “The Imaginary Orient.” Art in America XX (May): 119–191.

- Ogborn, Miles. 2004. “Archives.” In Patterned Ground: Entanglements of Nature and Culture, edited by Stephen Harrison, Steve Pile, and Nigel Thrift, 240–242. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Opperman, Serpil. 2016. “Material Ecocriticism.” In Gender: Nature, edited by Iris van der Turin, 89–102. New York: Macmillan Reference USA.

- Patrizio, Andrew. 2019. The Ecological Eye: Assembling an Ecocritical Art History. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Richards, Thomas. 1993. The Imperial Archive: Knowledge and the Fantasy of Empire. London and New York: Verso.

- Ruff, Thomas. 2019. “Thomas Ruff Reimagines 1850s India and Burma.” IndiaArtFair. Accessed December 20, 2020. http://web.archive.org/web/20200814204458/http://indiaartfair.in/thomas-ruff-reimagines-1850s-india-and-burma.

- Silverman, Kaja. 2015. The Miracle of Analogy: Or, The History of Photography, Part 1. Palo Alto (CA): Stanford University Press.

- Thomson, John. 1866a. “Practical Photography in Tropical Regions.” British Photography Journal 13 (327): 380.

- Thomson, John. 1866b. “Practical Photography in Tropical Regions.” British Photography Journal 13 (329): 404.

- Thomson, John. 1866c. “Practical Photography in Tropical Regions.” British Photography Journal 13 (329): 436–437.

- Thomson, John. 1866d. “Practical Photography in Tropical Regions.” British Photography Journal 13 (335): 472–473.

- Towler, J. 1866. “Landscape Photography.” British Journal of Photography, October 3: 478–479.

- Tripe, Linnaeus. 1857. “Views in Burma taken during the Mission to Ava (1857).” British Library, Photo 61.

- Willcock, Sean. 2021. Victorian Visions of War and Peace: Aesthetics, Sovereignty and Violence in the British Empire, c. 1851-1900. Yale University Press and Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

- Yule, Henry. [1856] 1968. Mission to the Court of Ava in 1855. London & New York: Oxford University Press.