Alfred Hrdlicka’s Memorial against War and Fascism caused much debate and political turmoil both before and after it was erected in 1988, and has continued to do so ever since.1 A dramatically changing Austrian cultural memory in the second half of the 1980s made its creation possible, even necessary. But even at the time it was put into place, the monument lagged behind the slowly changing historical collective consciousness, which began calling for more than a confrontation with the long-neglected history of World War II. More and more people saw the need to address the stark realities of Austrians’ participation in the persecution of Austrian Jews. While Hrdlicka’s memorial clearly displayed disgust for war and fascism and a will to publicly confront World War II, it failed to address Austrians’ guilt and shame at having participated in the genocide of European Jews.2 Thus, Hrdlicka’s work was lagging behind the new understanding of the past. Nevertheless, to this day, Hrdlicka’s memorial occupies a prominent public space in central Vienna.

This article considers what happens when a problematic public artwork is not turned down despite it being out of tune with an established cultural memory, and when it continues to occupy public space, influencing passers-by. During the decades since its installment, Hrdlicka’s memorial acted, unwilled, as performative. It became the site of artistic interventions that demanded an ongoing confrontation with a past many Austrians did not find adequately represented. Three of these interventions will be discussed in this article. I will investigate what exactly these works criticize, and explore the power and effect that emanate from them. Before investigating the distinct ways in which these temporal works entered a critical dialogue with Hrdlicka’s memorial, the latter will be introduced, in particular its obvious blind spot: the figure of the street-washing Jew.

THE MEMORIAL AND ITS BLIND SPOT: THE STREET-WASHING JEW

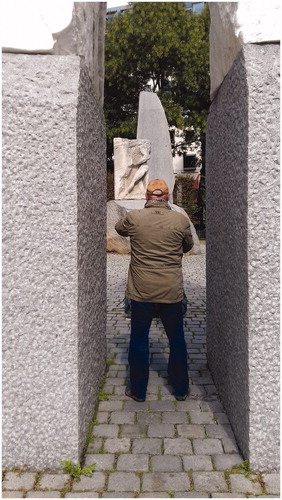

Alfred Hrdlicka’s Memorial against War and Fascism () is situated in Albertinaplatz in central Vienna. It can be described as a “walking-in” memorial,3 consisting of several parts occupying an area of over 25 square meters. Right in front of the Gate of Violence, a granite stone is embedded in the pavement. It contains some basic information, ending with the following statement: “This monument is dedicated to all victims of war and fascism.” These words clearly indicate what the monument is about. Likewise, they anticipate its criticism for having remembered all dead on equal terms.4

Figure 1. Alfred Hrdlicka. Memorial against War and Fascism. Vienna. 1988/1991. Marble, granite, limestone and bronze. Photograph by author.

The Gate of Violence with its two parts Hinterland Front and Hero’s Death depict the general chaos, horror and despair of war and the crimes against humanity committed in its shadow (). Passing through the gate or circumventing it, one stumbles upon the third piece, The Street-washing Jew. This figure stands out; it is the only element that one looks down on in an ensemble where all other parts are placed on plinths, or impress by their height.5 Furthermore, the dark patinated bronze contrasts with the light-colored marble and the limestone and granite of the memorial’s three other components. When viewed from the front, one sees the open and friendly face of an old man with a full beard, a kippa, and a hand holding a brush angled towards the pavement’s surface. As this element is crucial for the understanding of the work and the after-images it called forth, I will return to it in closer detail. First, I will give an overview of the composition.

From the figure on the ground, one turns towards Orpheus enters Hades. The plaque informs us that this part commemorates “the victims of bombings and all who lost their lives resisting National Socialism” — in other words: both innocent civilians who lost their lives in an Allied air raid and resistance fighters are honored, side by side. Clearly, not only in the already-mentioned dedication, but also in the visual representation, this monument commemorates all dead on equal terms.

Like the Street-washing Jew, the last piece of the memorial ensemble, the Stone of the Republic, is positioned directly on the ground. Although lacking a plinth, and set apart in the background, this stela nonetheless impresses due to its sheer height of more than 7 meters. It displays extracts from the policy statement of the provisional government signed by the three newly reconstituted political parties of Austria on April 27, 1945. This text became essential for the 1955 state treaty, and was reckoned as the hour of birth of the Second Republic. The excerpts contain a plea to all “antifascists” to overcome old resentments in this chaotic time, thereby referring indirectly to the violent struggles between left- and right-wing movements in Austria’s Ständestaat prior to 1938, which weakened the democratic system and inured Austro-fascism. The policy statement was meant to assure the Austrians that the Allies would support an independent Austria within the borders of 1938. The excerpts indicate that its goal was to encourage the citizens to show courage, reassure that there was no need for them to fear any repercussions, and to set aside all ideological differences, contribute to a stable government and restore the Austrian economy. Notably, no text segment mentions Austria’s complicity with Nazism; nor does it leave room for a future confrontation with the Austrian perpetrators. Instead, the call of the hour in 1938 was the vision of a democratic order, and it is this call that the memorial referred to when erected 50 years later.

In 2018, 80 years after the Anschluss (the German invasion on March 12, 1938 and the subsequent incorporation of Austria into the Reich), the monumentality, pathos and figurative style of Hrdlicka’s memorial differ from the established iconography of voids and abstract architectural formations used in many monuments dealing with World War II and in particular the Holocaust.6 Its dissonant appearance may secure attention, supported by its prominent setting in central Vienna. But this attention is problematic: while the work clearly expresses an urgent need to confront the painful past of World War II, it remains caught in an understanding of history that was already out of date when the work was established. Most problematic was, and remains, the portrayal of the street-washing Jew.

The point of departure for Hrdlicka’s bronze figure of the Jew was the public degradation that took place in the capital and other Austrian cities on the night before, and especially in the weeks and months after the Anschluss. In the so-called Reibpartien (scrubbing squads), people were forced to clean the streets of political slogans with brushes, sometimes toothbrushes.7 The slogans were reactions to a scheduled referendum organized by the Austro-fascist regime for an independent Austria (which was not executed due to the German invasion).8 The Reibpartien and other pogrom-like attacks during spring 1938, including the arrest of many political opponents, affected in particular Jewish citizens. Their shops were plundered; many were beaten, raped and driven to suicide.9 State authorities and ordinary fellow citizens carried out these assaults.10 The word Reibpartien hardly reflects the violent nature of these excesses, but it captures the hatred and malicious pleasure of the people who took part in these public spectacles, enjoying the humiliation of the Austrian Jews, their fellow citizens.11

Until the mid-1980s, the memory of the Reibpartien had been widely repressed.12 Many Austrians wanted to assign the blame to the German Nazis alone, or held the unruly mob responsible.13 The participation of, or toleration by, ordinary Austrians was not confronted. Moreover, Austrians distanced themselves from what followed: the systematic deprivation, the forced exile and the deportations to death camps. Although no one could anticipate that the incidents of 1938 were the prelude to a genocide, when viewed retrospectively, these events seem to point to what happened later. Of Austria’s around 200,000 Jews (depending on which definition of “Jewishness” one refers to — Nazi racial policy, traditional Jewish religious understandings or the self-definition of the persecuted), approximately 125,000 people fled into exile and more than 65,000 were murdered in the Holocaust.14

In his Memorial against War and Fascism, Hrdlicka presents the Jewish humiliation of spring 1938 not as a prelude to what followed but as the result of war and terror. This is the work’s blind spot.15 Walking through the Gate of Violence, or circumventing its two structures Hinterland Front and Hero’s Death, one passes dreadful scenes, snapshots from a violent war and the crimes against humanity during World War II. In this state of mind, one stumbles upon the bronze of the amorphous body of the old man flattened to the ground, enveloped in some kind of coat, his head, at a 90-degree angle, placed in an unnatural position. This stereotypical portrayal of an orthodox Jew and the public display of his degradation was, and still is, highly problematic as it confirms rather than alters the perception of “the other.”16 Although orthodox Jews were obvious targets for these excesses as they could easily be identified,17 Hrdlicka’s representation lacks historical accuracy: most Jews living in Vienna in the 1930s were not orthodox and were hardly identifiable as Jews from their outer appearance or dress code. Given the absence of Jews from the Austrian public sphere, both historically and at the time when Hrdlicka’s work was erected, this portrayal caused much bewilderment, particularly among Austrian Jews.18

It is important to realize that the reason why Hrdlicka’s work fails does not lie in this stereotypical depiction alone. The pivotal point is its placement within the memorial ensemble as an entity. The memorial’s misconception of history is a result of the composition chosen by the artist. This defines the reading and leads to a distortion of the historical situation — namely that the humiliation of the Jews had occurred in the shadow of war, thereby somehow excusing earlier Austrian antisemitic violence as part of the war atrocities. But Austrian antisemitism took place throughout 1938; there were violent excesses throughout the country long before World War II started in September 1939.19 If the figure had to appear at all, it had to be the opening scene, placed in front of, not behind, the Gate of Violence.

This close reading of the ensemble stands in contrast to the performative reading Hrdlicka had postulated after the criticism raised against his work. In fact, Hrdlicka did not call the bronze The Street-washing Jew but Bei der Reibpartie (At the Scrubbing Squad),20 a title that implies the presence of a spectator. According to Hrdlicka, the monument’s five distinct elements were to be viewed in a particular order.21 The artist intended that the sculpture of the Jew be a “thorn in the flesh” to his fellow citizens who would be forced to confront their “deep-rooted, home-grown antisemitism” every time they passed by the ensemble.22 Thus, Hrdlicka wanted to confront the non-Jewish audience with its guilt and shame. In his understanding, Austrians were being asked to activate their repertoire of historical images or narratives of the Reibpartien, and to realize that they themselves were performing the role of the bystanders. Ideally, this would lead them to self-critical reflection on their own, or criticisms of other Austrians’ roles and responsibilities after the Anschluss.23 While the artist was convinced that he “had memorialized the cheers and approving gazes of the Viennese population as a political statement against the selectivity of Austrian memory,”24 most Austrian Jews regarded the memorial differently. It was the body of the Jew, not the perpetrator or the laughing bystander, that was on public display.25 Hrdlicka’s memorial hardly did, and still fails to, find an audience who reacts in the prescribed manner to the scene. Indeed, it cannot, because the work’s failure lies exactly, as just described, in the spatial arrangement which Hrdlicka had created, where Jewish humiliation is positioned in the shadow of the war, when in fact it was the other way around.

In summary, the erection of the Memorial against War and Fascism in the prominent Albertinaplatz in central Vienna is a clear statement of a desire to confront the history of World War II and to integrate its memory permanently into the public sphere, thereby into cultural memory.26 However, Hrdlicka’s postulated desire to break free from a cultural memory that had dominated Austria for five decades, the myth of being Hitler’s first victim, failed.27 Hrdlicka’s memorial stayed rooted in a cultural memory that was already outdated at the time it was erected; a cultural memory not yet ready to openly confront Austrian complicity in the humiliation and persecution of its fellow citizens. His public work proves that the artist, like the country, was still caught in the victim myth. In 1988, Hrdlicka failed to confront the historical events that had occurred 50 years previously with the necessary empathy. His portrayal of the humiliated Jew became a stumbling block of controversy and bewilderment, and remains so to this day.28

THE PERFORMATIVE POWER OF A FAILURE

Against this background, Hrdlicka’s memorial can be considered a failure — but a failure that actually possesses a performative power as it provoked impressive after-images, namely a series of artistic interventions. Before we will turn to three of these, let me briefly explain how I use the term “performative” and what I mean by “after-images.”

I employ the term “performative” following ideas explored by the philosopher John L. Austin in his influential How to do Things with Words (1962). His fundamental insight was that words are not only descriptive but have the capacity to do something, namely to bring into being what they name. This notion has proven to be very influential in the field of Cultural Studies, and it is useful to explain what Hrdlicka’s memorial does; namely, as shown, it freezes an understanding of a past already outdated when the work was erected, in a prominent place, thereby having the chance to influence many people on a daily basis. However, this is not all: there is also a force that emanates from its actual failure as it calls forth after-images which in their turn create, albeit only temporarily, new realities displaying alternative readings of Hrdlicka’s version of the past.

The term “after-image” was used in James E. Young’s At Memory’s Edge: After-Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture (2000) and became the title of an exhibition at the Neues Museum Weserburg Bremen in 2004 that built on Young’s research.29 The term hints at the accumulation of images produced after World War II and the Holocaust, which not only mediate history but also constantly call forth new images. The artistic after-images shown in the exhibition in Bremen were critical reflections of how this history is mediated, sometimes instrumentalized. After-images, understood as products of social memory, do not just illustrate a changing cultural memory (based on new research findings, for example) but can in themselves, as aesthetic experiences, stimulate confrontations with the past, thereby contributing new insights. Here, art acts as an arena in which to negotiate established ways of representation, to make viewers aware of processes of commemoration, often by the use of exaggerations and confrontation. Thus, these after-images potentially possess transformative power in an Austinian sense, as they imply “re-vision” — the seeing anew of what is there, Hrdlicka’s work — in relation to what was there, the Reibpartien. The aesthetic experience of after-images offers a chance to become aware of established forms of commemoration and acts as encouragement to confront the past anew, from a current perspective. Thus, the term after-images grasps the concrete artistic interventions that took place at Hrdlicka’s memorial, while also reflecting the interplay of (historic/artistic) images. Moreover, the term hints at what is called forth, maybe only temporarily, in each individual’s perception when seeing the artistic intervention against the numerous images accumulated throughout a lifetime, or later when the temporary intervention is gone but one revisits Hrdlicka’s memorial.

THE BLIND SPOT’S UNWILLED PERFORMATIVES

The performative force that results from the memorial’s shortcomings gave rise to many responses. Rachel Whiteread’s Nameless Library (2000) in Judenplatz, within walking distance, can be seen as the most significant, lasting response that Hrdlicka’s memorial produced. Its very existence is a result of the never-ending controversy that prompted Simon Wiesenthal in 1994 to initiate a campaign for an alternative memorial dedicated to the murdered Austrian Jews.30 In this article, I will concentrate on the consequences that the performative force had on the Memorial against War and Fascism itself, such as the signboards that were added much later, in 2012.31 They reveal how much Austrian cultural memory had changed in the years since the memorial was erected. The wording of these signboards (Wienkl) tries to counteract what is expressed in the visual, namely that the “street-washing Jew recalls the degradation that foreshadowed persecution and murder.” However, the much stronger visual expression dominates the scene to this day, narrating a different version of history — a version that, during the preceding years, called for equally strong after-images, as we will see.

The memorial, and in particular the humiliated Jew, produced highly uncomfortable images. While the work’s other elements are seen from below, most put on plinths giving them an aura of respect, the low bronze of the Jew by contrast is only about 50 cm in height, anchored directly to the ground. This makes it vulnerable, and led to passers-by using it for unwelcome purposes: people would sit on the man’s back to eat an ice cream or tie their shoelaces, using the old Jew as support, and dogs would urinate on it.32 Contrary to Hrdlicka’s posited intention, the sculpture became a symbol of a continuing and renewed humiliation. Consequently, the City of Vienna urged Hrdlicka to alter his memorial to prevent such impious scenes.33 However, changes were not made until another artistic intervention occurred, widely understood as an act of vandalism.

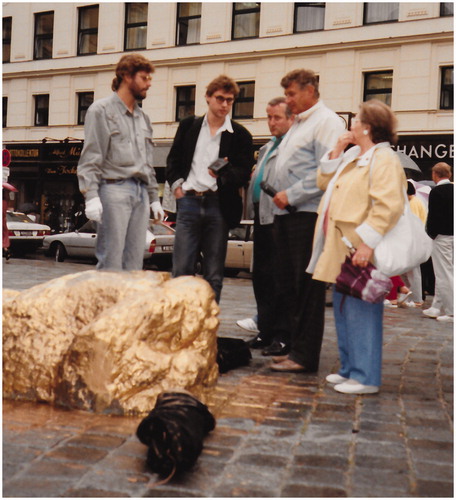

THE BLIND SPOT DEMANDS REACTION AND ACTION: GOLD ATTACK AND BARBED-WIRE PROTECTION

One and half years after Hrdlicka’s memorial was inaugurated (but not yet completed), sculptor Johannes Angerbauer-Goldhoff covered The Street-Washing Jew in gold bronze, fabricated by the artist himself ().34 This “gold attack,” subversively conducted on May 25, 1990, was the starting-point for the artist’s life-long examination of the material gold, generally understood to be pure and sacral, but in Angerbauer-Goldhoff’s view a material highly contaminated by greed and misuse of power, leading to suppression, exploitation and the destruction of men and nature. I will concentrate on his very first intervention, Zahn-Gold-Zeit-Gold. Angerbauer-Goldhoff’s intervention made fitting allusions to the enrichment that resulted from the expropriation and murder of European Jews, including the gold teeth robbed by the Nazis from concentration camp victims. However, the topic of Nazi gold only began to receive international attention during the 1990s. This might be one explanation why his action did not receive greater media coverage, as few grasped its implications. Another reason might be that the gilding of the Jew in itself was not unproblematic as it evoked common antisemitic perceptions of Jews as wealthy and greedy profiteers.35 Preoccupied by an overarching interest in exposing the contamination of the material gold, Angerbauer-Goldhoff rejects this criticism. To him, the gilding of The Street-Washing Jew was an attempt to enhance the status of the humiliated.

Figure 2. Johannes Angerbauer-Goldhoff. Tooth-Gold-Time-Gold. Vienna. 25 May 1990. Photographer unknown; courtesy of the artist. Photograph © Johannes Angerbauer-Goldhoff.

Interestingly, Angerbauer-Goldhoff completed his gold attack unhindered. Over the decades, even the Viennese authorities had become accustomed to provocative Aktionskunst.36 In Austria, there exists a high degree of tolerance when it comes to public art. Moreover, the police might have been blinded by the shiny material, leading to the assumption that the artist had been commissioned. Symptomatic for Austrian cultural memory at the time was that the police, as Angerbauer-Goldhoff recalled, did not care about the figure of the Jew. They only intervened when they thought the pavement would be besmirched. The action was perceived as damage to property, and the artist was put into temporary custody, and summoned to a public health officer.

Angerbauer-Goldhoff’s intervention made Hrdlicka finally meet the city’s pleas to alter his memorial. Three days after the gold attack, the sculpture was removed.37 This prevented Angerbauer-Goldhoff from completing the planned second part of the performance, namely the careful cleaning of the aureated Jew, to be carried out by the artist on his bare knees. Many, especially from the Jewish community, had hoped that the bronze would not return.38 It was, however, restored and reinstalled two months later, now with what appeared to be barbed wire added to the figure’s back to stop people sitting on it.

This form of “protection,”39 created by Hrdlicka himself, called forth other difficult images counteracting the artist’s original intentions. References to Christian iconography were close at hand, as the metal spikes resembled the crown of thorns worn by Jesus, thereby alluding to the classic antisemitic portrayal of Jews as the murderers of Christ.40 Far from solving the problem, the barbed wire on the old Jew was as unbearable an image as the ice cream-eating tourists. Hrdlicka’s monument remained a reminder of Jewish humiliation, for many too painful to look at. Consequently, some Viennese Jews avoid(ed) Albertinaplatz altogether.41 Nonetheless, the Memorial against War and Fascism remained in place, and continued to be a stumbling-block, challenged by further artistic interventions.

EVOKING HRDLICKA’S INTENDED PERFORMATIVE BY EMBODIMENT

The second intervention, Cleaning Time (Vienna): a Shandeh un A Charpeh (Yiddish for A Shame and a Disgrace) (), by the internationally acclaimed South African performance artist, Steven Cohen, was staged in Albertinaplatz and at two additional sites, the Helden- and Judenplatz, on two separate occasions in March and November 2007. This performance, at these three historically relevant sites, can be seen as a refusal to produce another written-in-stone truth and as a general questioning of the monument genre’s ability to adequately address the Holocaust. The performance at these three sites will be the subject of a separate study. Here, I will focus on Cohen’s performance at Hrdlicka’s memorial.

Figure 3. Steven Cohen. Cleaning Time (Vienna) – A Shandeh un a Charpeh. Albertinaplatz #1. Vienna. 2007. Photograph © Marianne Greber/Bildrecht, 2018.

Cohen’s intervention, like Angerbauer-Goldhoff’s and the historical events the memorial commemorates, took place in plain daylight. Both artists’ projects were seen only by a small audience, and ended with the intervention of the police. There was never any doubt, however, that Cohen’s Aktion was an art performance, and later prestigious art museums bought and occasionally exhibited the iconic photos taken by Marianne Greber.42

In his artistic rendition of The Street-Washing Jew, Cohen is equipped with oversized and highly symbolic props, such as a giant red tooth brush, and authentic items such as a Judenstern (patches with the Star of David and the word “Jew” that were used in many parts of Europe under Nazi rule to mark Jewish people) and a gas mask. This strange, almost naked being crawls through the streets, pulled down by oversized red lacquer high heels, burdened by a menorah. A cork adorned with crystals sticks out from his anus, catching the viewer’s reluctant but recurrent attention.

Cohen’s provocative performance breaks with established forms of Holocaust commemoration. Consequently, it acts as an effective tool that forces us to look again and rethink history and how it is commemorated in Hrdlicka’s memorial. At the same time, Cohen’s exaggerations correspond to the grotesque absurdity Austrian Jews were confronted with in 1938. Jewish and homosexual, Cohen embodies antisemitic propaganda of the 1930s, which described the Jewish body as abnormal, gay and perverse.43 Cohen takes the liberty of alluding to the privileged economic position of some bourgeois Viennese Jews, which had called forth much envy and resentment. In the artist’s eyes, this made them vulnerable scapegoats and targets for the growing political frustration during the Austro-fascist regime.44 The materiality of the crystal refers to the privileged status of these Viennese Jews, as well as how their oppressors grew wealthy as a result of the ethnic cleansing that followed. By the presence of his own body, Cohen’s representation points to the continuation of Jewish degradation, which did not stop with the end of the war. It is still necessary to confront how survivors were treated on their return or in exile after 1945,45 especially in terms of (the rather late) restitution46 and the inadequate representation of their humiliation.

Despite all exaggerations, the image Cohen created is in fact more historically accurate than the Jew in Hrdlicka’s memorial: Cohen cleans the street of Austria’s capital on his knees, not flattened to the ground. His cleaning, however, is symbolic. With the giant toothbrush he pushes the dirt back and forth, endlessly confronting the shame and disgrace resulting from the insight into what humans were capable of doing to other humans.

In contrast to Hrdlicka or Angerbauer-Goldhoff, Cohen does not subject the bronze figure of the Jew once again to any kind of humiliation, but instead exposes his own body.47 This is a strenuous performance both for the artist and the audience. For Hrdlicka “the martyred human body best expresses human suffering, especially when rendered as authentically (and provocatively) as possible.”48 Cohen takes the topic of the martyred human body one step further: by using his own, very much alive body, contrasted with Hrdlicka’s static memorial in granite, marble and bronze. According to the plaques, The Gate of Violence, Orpheus enters Hades and the Stone of the Republic are of granite quarried at Mauthausen. Already shortly after the war, the former concentration and labor camp Mauthausen became a memorial site and in the decades to come, official Austrian memorial efforts were mainly directed towards this site.49 In the former camp, prisoners had to work in the quarries under terrifying conditions. By using material from this region, Hrdlicka anchors his work historically in the wider landscape of Austria and loads its physicality with symbolic meaning, transmitted by the text on the plaque and by the status Mauthausen has in Austrian memory culture. While the use of contaminated material in Hrdlicka’s memorial forms the base of a permanent marker in space, the contaminated material used by Cohen, as the authentic Judenstern, only temporarily occupies this space. The whiteness of Cohen’s rendition of the cleaning Jew corresponds to the white figurative sculptures on top of most plinths, executed in costly Carrara marble. While Hrdlicka’s work as a sculptor might be physically extremely exhausting, it takes place in the privacy of the studio. Cohen performs in the bustling city, at a spot frequented by many tourists, not in the protective world of the studio or gallery. He feels physical pain with each move he makes, because of the crystal in his anus, and because his knees scrape on the asphalt. Furthermore, Cohen encounters and directly endures the reactions his performance generates. Because his intervention was not announced, it came as a total surprise to anyone who walked by.

In my reading, Cohen did not primarily want to shock — even though according to the artist, the shocking historical events demand, with the passage of time, an equally shocking artistic rendition.50 To me, Cohen aimed to disrupt the familiar and counteract Hrdlicka’s show of strength, spectacle and figurative explicitness by making his own Jewish body publicly vulnerable.

The reactions of passers-by (), collected in a 10-minute video by the artist, and a news segment by the ORF (the Austrian equivalent of the BBC) are important since Cohen’s performance is created not only in the public space but with the public.51 Where Hrdlicka failed to convey performative engagement, instead producing historically incorrect statements fixed in stone and marble, Cohen succeeded. His grotesque epiphany ventures through the streets, calling forth reactions similar to those evoked in 1938: incomprehension, bewildered amusement, amazement and discomfort. While Hrdlicka thought of an audience that silently contemplated Austrian responsibilities, the reactions to Cohen’s embodiment revealed rather frightening similarities with those faced by the Viennese Jews in 1938: many spectators were laughing, enjoying the unfamiliar scene in the familiarity of the city setting. They also took photos with their mobile phones, happy that they might appear on TV. Cohen’s street-washing Jew points to the lack of reflection about or awareness of many passers-by of what is in fact being enacted: the behavior many Austrians displayed when seeing their fellow citizens publicly humiliated 69 years earlier, as captured in photographs and memoirs.

Figure 4. Steven Cohen. Cleaning Time (Vienna) – A Shandeh un a Charpeh. Albertinaplatz #4. Vienna. 2007. Photograph © Marianne Greber/Bildrecht, 2018.

Given the surprise that Cohen’s persona created, it might be difficult to draw far-reaching conclusions about what these reactions actually reveal about Austrian cultural memory. After all, in contrast to the historic events, his cleaning Jew had agency — the artist himself had made the decision to perform in public — and the public he met had not created the scene it faced. Despite these crucial differences, the dominant reaction Cohen’s performance caused had been amusement, uncannily similar to the reactions shown in the historical photographs, and especially discernible in the only moving images of these scenes, to which I will now turn.

FILLING THE GAP: THE MISSING IMAGE

One year after Cohen’s performance, writer and filmmaker Ruth Beckermann, daughter of Holocaust survivors and one of the most prolific critics of Hrdlicka’s memorial at the time it was erected, visually expressed her verbal criticisms made 26 years ago.52 Her main criticism had been that Hrdlicka “cut off” the grinning spectators and reduced the Jew to an eternal victim; she doubted the audience’s capacity or willingness to follow Hrdlicka’s intended performative spectacle: to fill in the missing part and pose self-critical questions.53 In her installation The Missing Image (2015) (), Beckermann added what was absent in Hrdlicka’s memorial: the cheering faces of the amused crowd watching the humiliation of their fellow citizens. This footage was not known when Cohen cleaned the streets of Vienna in 2007.

Figure 5. Ruth Beckermann. The Missing Image. Vienna. 9 Mar.–10 Dec. 2015. Photograph © Philipp Diettrich.

It was the rediscovery of amateur archival film footage that made Beckermann’s installation possible. This footage was found in 2005 as part of a larger research project.54 The material was shown in 2008 during a series of public events at the Film Museum, situated just across the road from Hrdlicka’s memorial, where Beckermann encountered what became key to her intervention.55 So far, this five seconds of footage remain the only known moving image of the Reibpartien.56 Most likely it was secretly filmed57 and not an extract from officially produced propaganda material.

In Beckerman’s intervention, the film clip appeared in a two-channel-installation on LED-screens right in front of the bronze on the ground. The screens were integrated delicately into the Gate of Violence.58 The historical authenticity of the moving sequences offers contemporary spectators what is missing in Hrdlicka’s work. Beckermann’s intervention demanded that audiences confront the historical burden that Austrians had long ignored, given that they had not only been victims, but also bystanders and perpetrators. However, unlike the audience response that Hrdlicka had in mind, Beckermann did not force the viewer into the role of the cheerful bystander. Hardly anyone laughed, as many did when exposed to Cohen’s persona, when being confronted with Beckermann’s work. Rather the audience was invited both to revisit the scenes from 1938, and to re-see Hrdlicka’s memorial, which by its permanence and prominent setting has exerted an authority over the construction and shaping of Austrian cultural memory.

When Beckermann asks the audience to confront what happened in 1938, she does so by using a carefully thought-out artistic composition: the short excerpt of black and white film appears in a new order, oversized and presented in slow motion in a loop of 1 minute and 34 seconds, repeated again and again, day and night, being especially effective in the dark. The performativity of The Missing Image lies in its communicative power of the moving images, encouraging the audience to confront these historical events anew. Thereby, the Jewish men forced to clean the streets and the laughing crowd of bystanders are both presented oversized, and at eye level. This confrontation has an intensity that is hard to ignore. These were the scenes Austrians so long avoided — scenes that were known, but gained a new facticity due to the authenticity and poignancy of the now publicly accessible moving images. The moment of insight and confrontation is furthermore encouraged by Beckermann, in that spectators see their own portraits on the LED screens. This promotes self-critical engagement with the past and with the remnants of its cultural memory, as in Hrdlicka’s prominently placed memorial.

In both Cohen’s and Angerbauer-Goldhoff’s interventions, time is an important aspect. Angerbauer-Goldhoff made clear that time would not solve the question of the guilt that the crimes had caused. In fact, over the decades historical research has revealed the extent of the cruelties committed. Thereby, Nazi gold is only one part of the picture, which nonetheless hints at how this past and its atrocities still affect us today on many levels, including the ethical and the economic. When it comes to the stolen gold, it might have been reused in other products, and might be found in wedding rings bought today, as Angerbauer-Goldhoff points out.59 Likewise, Cohen’s attempt to clean time is meant to fail. Rather, this lost estranged being, with its delicate fairytale make-up, acts as a living reminder of the ongoing need to clean up, to come to terms with this past.

Time also plays a crucial role on several levels in Beckermann’s work. In 2015, Beckermann could count on many people pausing to confront these uncomfortable images. Those who watched were rarely those who had committed the crimes. Austrian cultural memory had changed significantly since Hrdlicka’s work was erected. What was still taboo in Hrdlicka’s day, to confront Austrian participation in the persecution and murder of their fellow citizens, had become part of official cultural memory and found a broad consensus among the population.60 It was easier to face this past and one’s own reflection on the screen for the second and third generation born after the war; it was not their own personal guilt and shame they confronted, but those of their parents or grandparents. Furthermore, it was now widely accepted to acknowledge responsibility for these historic crimes.

Nevertheless, it remained relevant to confront this past anew, especially in this specific public context, leading to a questioning of Hrdlicka’s self-evident, permanent occupation of this prominent place. Furthermore, Beckermann addressed continuities between historical and contemporary events: one day in June 2015, she exchanged the historical images of the Reibpartien with scenes from Erdberg in which Austrians were demonstrating against a home for asylum seekers.61 In the same Viennese district, Jews were forced to clean the streets in 1938 accompanied by the laughter of their fellow residents.62 Now, asylum seekers were not welcome. The frightening similarities in reaction to “the other” were effectively exposed in Beckermann’s installation.

In contrast to the unannounced interventions by Angerbauer-Goldhoff and Cohen, Beckermann’s work was officially approved and occupied the site for almost nine months. It found wide appreciation among the general public and the prominent support of intellectuals and politicians alike. Nevertheless, it was dismantled in December 2015.63 Though Beckermann never argued for the removal of Hrdlicka’s memorial,64 the echoes that reverberate from the photos documenting her work imply that something is missing.65

TIME FOR “HRDLICKA MUST FALL”?66

According to the cultural historian Heidemarie Uhl, Holocaust memorials are “seismographs of historical consciousness.”67 Admittedly, as already the title indicates, Hrdlicka’s Memorial against War and Fascism was not intended to be a Holocaust memorial. Yet, it could not possibly have excluded this pivotal aspect. While Hrdlicka did not avoid representing the humiliation of Austrian Jews altogether, their extermination was not his work’s main subject. This alone demonstrates how grounded Hrdlicka was in a cultural memory that demanded confrontation with World War II but did not yet focus on the genocide of European Jews, in which many Austrians participated. Hrdlicka’s stated intention was to come to terms with the myth of Austria’s innocence. His memorial, however, and in particular the old Jew, exposed how much Hrdlicka was still grounded in this perception, which made it impossible to confront Austrians’ shameful participation in the systematic persecution and annihilation of their fellow citizens.68

Uhl’s statement remains true for all, not just Holocaust, memorials. By their physical occupation of a public space, memorials are expressions of political compromises, confronting what is possible at a given time and place. Once realized, these public manifestations take on an authority that has the potential to impact audiences.69 This can be an opportunity, but also a risk, as in Hrdlicka’s case: his public work continues to transport a message out of tune with the established cultural memory, reshaped due to new historical insights. The sophisticated audience may read Hrdlicka’s work as a materialized manifestation of a cultural memory in transformation, of an incipient phase in Austria’s reappraisal of the Nazi past. For most passers-by, though, this public marker equals all atrocities committed during World War II and continues to present a stereotypical portrayal of the Jew as “the other”; here as the eternal victim.

The artistic interventions at the site indicate that revaluations of the past demand new visible, physical manifestations in the here-and-now. In their temporality, these works argued for an ongoing confrontation with Austrian guilt and shame, an aspect that to this day is not dealt with in a permanent memorial. Instead, it is Hrdlicka’s memorial whose permanence is secured due to its status as a historical monument,70 and which defines how this past is publicly narrated and mediated. In its prominent setting, it is frequently photographed by innumerable tourists and many people pass it by every day (). Beckermann’s intervention, more in line with the contemporary established cultural memory, had to be dismantled. What do we do with Hrdlicka’s Memorial against War and Fascism? Do we just let it occasionally provoke powerful artistic after-images; or do we materialize the more recently established cultural memory in public space?

Without doubt, monuments which recall shameful national histories are relatively new contributions to cultures of memory. From Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial (1982) to Peter Eisenman’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (2005), it took long and fierce debates before such works could be realized. As Erika Doss has demonstrated, the precondition for such works is an acknowledgement that there is in fact something to be ashamed about.71 Today, however, as Doss shows, monuments to shameful national pasts have become quite common.72 They reveal a different understanding of how democratic countries are expected to handle the past — not only as a sequence of events to celebrate national pride, but also as reminders of guilt to deter future cultural atrocities.

The aspect of shame is elaborated most clearly in Cohen’s performance, made explicit already in the title, A Shame and a Disgrace. His persona alludes to shame’s linguistic roots and meanings throughout history which are almost always connected to the physicality of the body, to nakedness, the body’s public display, and sexuality, and bound to the act of seeing and being seen.73 While the notion of shame served as a regulator in Western societies to “civilize” the body, by extension, “decreased shame thresholds may be found when mannered behaviors are socially unrestrained, at mob lynchings,”74 or pogrom-like riots such as the Reibpartien. The enjoyment felt during such excesses is almost always necessarily repressed when life returns to normality.

Living for decades with the myth of having been Hitler’s first victim did not require Austrians to confront their roles as bystanders and perpetrators. Following Doss, shame is a “key affect in identity formation” that in fact can have a social function: it might offer social or political transformation towards accepting responsibility. Thus, rather than avoiding shame, one should embrace its transformational power, especially as this has already become an integral part of Austrian memory culture and as internationally it also has become increasingly common to embrace this uncomfortable feeling, using it in reparative terms.75

Having incorporated Austrian guilt in the participation of the murder of the European Jews into cultural memory was in fact a precondition for Beckermann’s installation to find official approval, remain in place for almost nine months and receive wide acceptance among different audiences. The status of Hrdlicka’s work as “Denkmal” (worthy of preservation) makes permanent alterations — such as Beckermann’s, or perhaps a reflective surface around the figure of the Jew (in order to reflect the spectators and thereby produce the performative effect Hrdlicka had in mind) — almost impossible. More importantly, such alterations would not substantially change the misconception of history resulting from Hrdlicka’s chosen composition in which the humiliation of the Austrian Jews is placed in the shadow of the war atrocities.

In Hrdlicka’s memorial, the humiliated Jew is frozen in the pose of the eternal victim; he is already flattened to the ground, and thus he cannot fall. If the site cannot be turned into a stage of annual interventions (similar to those at Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth), the memorial should be removed. Another work needs to be added to the Austrian memorial landscape. Only then would the seismograph Uhl speaks of be complete. Contemporary artists should be entrusted with facing the ethical and aesthetic challenge of producing more sensitive images that confront historic guilt and shame in public, on a permanent basis, without voyeurism and without freezing the victims into the state of eternal dehumanizing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article builds on collaborative research conducted with Diana I. Popescu as part of our research project Making the Past Present: Public Perceptions of Performative Holocaust Commemoration since the Year 2000, financed by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet) [421-2014-1289]. My sincere thanks to Diana, who triggered the investigation on Hrdlicka’s memorial by discovering Ruth Beckermann’s intervention. Diana provided valuable insights in particular through her research on visitors’ reactions to the site.

NOTES

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tanja Schult

Tanja Schult is an Associate Professor and Senior Lecturer at Stockholm University, where she teaches Art History and Visual Studies in the Department of Culture and Aesthetics. Her current research project, Making the Past Present: Public Perceptions of Performative Holocaust Commemoration since the Year 2000 (together with Diana I. Popescu), is financed by the Swedish Research Council. Schult is the author of A Hero’s Many Faces: Raoul Wallenberg in Contemporary Monuments (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, paperback in 2012), the editor (together with Eva Kingsepp) of Hitler für alle. Populärkulturella perspektiv på Nazityskland, andra världskriget och Forintelsen (Carlsson, 2012), and the editor (together with Diana I. Popescu) of Revisiting Holocaust Representation in the Post-Witness Era (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

Notes

1 Theodor Scheufele, Das Mahnmahl am Wiener Albertinaplatz und die Presse. Eine Dokumentation (1978–1992). Vol. 2 of Alfred Hrdlicka: Mahnmal gegen Krieg und Faschismus in Wien, ed. Ulrike Jenni (Graz: Akademische Druck, 1993), 7.

2 Ulrike Jenni, Alfred Hrdlicka: Mahnmal gegen Krieg und Faschismus in Wien, 2 vols. (Graz: Akademische Druck, 1993), 29.

3 John Czaplicka, “Stones Set Upright in the Winds of Controversy: An Austrian Monument against War and Fascism,” in A User’s Guide to German Cultural Studies, eds. Scott Denham, Irene Kacandes and Jonathan Petropoulos (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 285, note 21.

4 The description is based on my visits to the place in 2015 and 2017. In another article, Hrdlicka’s memorial is described even more extensively and its coming into existence is embedded in the Austrian cultural memory; Tanja Schult and Diana I. Popescu, “Infelicitous Efficacy: Alfred Hrdlicka’s Memorial against War and Fascism in Vienna,” Articulo - Journal of Urban Research (forthcoming).

5 See: Ruth Beckermann, Unzugehörig: Österreicher und Juden nach 1945 (Vienna: Locker, 2005 [1989]), 15.

6 It is noteworthy that Hrdlicka’s figurative, expressionistic style was realized at a time when counter-monuments such as the Jochen and Esther Shalev-Gerz’ Monument against Fascism (1986) in Hamburg-Harburg were already erected. They accepted their minimalistic monument’s slow disappearance into the ground as a result of audience participation, thereby questioning the genre’s traditional claim to permanence. See: Uwe Schneede, “Kein Held aus Erz, nur ein Jude im Staub,” Rheinischer Merkur, 20 Jan. 1989.

7 Gerhard Botz, “Judenhatz und Reichskristallnacht,” in Der Pogrom 1938, ed. Kurt Schmid (Vienna: Picus, 1990), 19, 15. For an image of such a Reibpartie, see: https://www.doew.at/erkennen/ausstellung/1938/ns-terror/terror-von-unten (accessed 4 Jan. 2018). Astonishingly, given the relevance of these iconic images for our perception of this past, these photographs are still widely under-researched. It remains unclear whether there are “numerous” photos documenting the event (see: Botz, “Judenhatz und Reichskristallnacht,” 9) or only very few (see: Hans Petschar, “Bekannt und Unbekannt. Fotografische Ikonen zum ‘Anschluss’ Österreichs an das Dritte Reich,” in Schlüsselbilder des Nationalsozialismus, ed. Werner Dreier [Innsbruck: Studien, 2008], 58, 66–67). Consequently, the identity of the portrayed (and thus the reasons for their degradation as Jews/political opponents/etc.) remains in most cases uncertain. I thank historian Ingo Zechner, Director of the Boltzmann Institute, for a thought-provoking conversation on this issue on 20 Sep. 2017 in Vienna.

8 Crowds in Vienna during Anschluss. Mar.-Apr. 1938 (film). Baker Family Collection [RG-60.4553], part of Special collection Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive, US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

9 Hans Safrian and Hans Witek, Und keiner war dabei: Dokumente des alltäglichen Antisemitismus in Wien 1938, revised edition (Vienna: Picus, 2008 [1988]), 23–27, 61–65; Martin Krist and Albert Lichtblau, Nationalsozialismus in Wien: Opfer. Täter. Gegner (Innsbruck: Studien, 2017), 74, 81, 241–45.

10 See: Dieter J. Hecht, Eleonore Lappin-Eppel, and Michaela Raggam-Blesch, “‘Anschluss’ – Pogrom in Wien,” in Topographie der Shoah: Gedächtnisorte des zerstörten Wien (Vienna: Mandelbaum, 2015), 16–41.

11 See: Petschar, “Bekannt und Unbekannt,” 66.

12 Matti Bunzl, “On the Politics and Semantics of Austrian Memory: Vienna’s Monument against War and Fascism,” History and Memory 7. 2 (1995): 7–40.

13 Botz, “Judenhatz und Reichskristallnacht,” 9.

14 Heidemarie Uhl, “From the Periphery to the Center of Memory: Holocaust Memorials in Vienna,” Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust 30.3 (2016): 242.

15 This aspect is elaborated in close detail in Tanja Schult and Diana I. Popescu, “Infelicitous Efficacy.”

16 See: Czaplicka, “Stones Set Upright,” 278.

17 Krist and Lichtblau, Nationalsozialismus in Wien, 242.

18 Matti Bunzl, Jews and Queers; Symptoms of Modernity in the Late-Twentieth-Century Vienna (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 3, 30, 47; Beckermann, Unzugehörig, 14–15; and Eva Kuttenberg, “Austria’s Topography of Memory: Heldenplatz, Albertinaplatz, Judenplatz, and Beyond,” The German Quarterly 80.4 (2007): 473.

19 Safrian and Witek, Und keiner war dabei, 15–16, 23–27, 61–65; and Krist and Lichtblau, Nationalsozialismus in Wien, 64.

20 See: Czaplicka, “Stones Set Upright,” 275.

21 Bunzl, “Politics and Semantics of Austrian Memory,” 21.

22 Quotes from Michael Z. Wise, “Vienna’s Statue of Limitations: The controversial Holocaust monument,” Washington Post, 24 Jun. 1990. http://michaelzwise.com/viennas-statue-of-limitations/; See also: James E. Young, “Austria’s Ambivalent Memory,” in The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning in Europe, Israel and America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993), 110.

23 Bunzl, “Politics and Semantics of Austrian Memory,” 22.

24 Ibid., 30.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid., 22, 24.

27 Safrian and Witek, Und keiner war dabei, 318; Krist and Lichtblau, Nationalsozialismus in Wien, 376; and Heidemarie Uhl, “Das ‘erste Opfer’. Der österreichische Opfermythos und seine Transformationen in der Zweiten Republik,” Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft (ÖZP) 30.1 (2001): 93–108.

28 See: Heidemarie Uhl, “Die Transformation des ‘österreichischen Gedächtnisses’ in der Erinnerungskultur der Zweiten Republik.” GR/SR 13.2 (2004): 49. https://storiaeregione.eu/attachment/get/up_292_14696102947266.pdf (accessed 12 Jan. 2018).

29 After Images: Kunst als soziales Gedächtnis. Exhibition catalogue (in German and English), Neues Museum Weserburg Bremen, with contributions by among others James E. Young, Harald Welzer and Peter Friese (Frankfurt/Main: Revolver, Archiv für Aktuelle Kunst, 2004); see in particular 25, 29–30, 57, 60, 64–65, 83, 95.

30 Simon Wiesenthal, Projekt: Judenplatz Wien: Zur Konstruktion von Erinnerung (Vienna: Paul Zsolnay, 2000), 9; and Mechthild Widrich, “The Willed and the Unwilled Monument: Judenplatz Vienna and Riegl’s Denkmalpflege,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 72.3 (2013): 383.

31 This section is based on correspondence with Marianne Taferner, Referat Kulturelles Erbe, Magistratsabteilung 7 — Kultur, Vienna, email to the author 11 Sep. and 19, 2017. An image of the ‘Wienkl’ can be found in Ina Weber, “Bis in den letzten ‘Wienkl’,” Wiener Zeitung, 24 Sep. 2012. http://www.wienerzeitung.at/nachrichten/wien/stadtleben/488966_Bis-in-den-letzten-Wienkl.html (accessed 12 Jan. 2018). They replaced signs added earlier that had aged and needed to be replaced.

32 Wise, “Vienna’s Statue of Limitations.” For an image see: Young, “Austria’s Ambivalent Memory”, 109.

33 Heidi Grundmann, “Wien ist anders! — Ist Wien anders?” Kunst Intern, 7 Jun. 1990, 48; and Marta S. Halpert, “Die missglückte Provokation,” Wochenpresse, 20 Jul. 1990, 62.

34 This section is based on an extensive email correspondence with the artist since Sep. 2017, a long interview with him in Steyr on 19 Sep. 2017, material provided by the artist, and Manuela Schmid, “Johannes Angerbauer — Die Rückkehr des Goldes zur Erde” (MA thesis, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main, 1999). My inquiries made Angerbauer-Goldhoff retrieve material long thought lost and confront it anew after 27 years. As a consequence, he updated his (already well documented) homepage with new posts, such as a video made on the day of his performance: http://www.social.gold/D/archiv/zahn_gold_zeit_gold/index.html (accessed 4 Jan. 2018). The homepage includes photos, detailed descriptions of the event, reflections by the artist, newspaper articles, documents from his arrest and correspondence with state/city authorities. See also: Scheufele, Das Mahnmahl am Wiener Albertinaplatz und die Presse, 286–88; and Eva Maria Bachinger and Gerald Lehner, Im Schatten der Ringstrasse: Reiseführer durch die braune Topographie von Wien (Vienna: Czernin, 2015), 46–51.

35 See: Botz, “Judenhatz und Reichskristallnacht,” 21.

36 Oliver Jahraus, Die Aktion des Wiener Aktionismus: Subversion der Kultur und Dispositionierung des Bewusstseins (Das Problempotential der Nachkriegsavantgarden, vol. 2 (Munich: Fink, 2001).

37 Aktenvermerk, Bundespolizeidirektion Wien. Staatspolizeiliches Büro, 25 May 1990. (Document provided by Angerbauer-Goldhoff). See also: Scheufele, Das Mahnmahl am Wiener Albertinaplatz und die Presse, 247.

38 Wise, “Vienna’s Statue of Limitations.”

39 Bericht (I – Pos 5675/VI-StB/90). Bundespolizeidirektion Wien. Staatspolizeiliches Büro. 21 Jun. 1990. (Document provided by Angerbauer-Goldhoff).

40 Otto Friedrich, “Die Rückkehr der Grinser,” Die Furche, 5 Mar. 2015, 17.

41 Wise, “Vienna’s Statue of Limitations;” and Alexia Weiss, “Grinser und Gaffer,” Wiener Zeitung, 14 Mar. 2015. http://www.wienerzeitung.at/nachrichten/wien/stadtleben/740556_Grinser-und-Gaffer.html (accessed 4 Jan. 2018).

42 Marianne Greber worked closely together with Cohen and chose the sites. This section is based on an extensive email correspondence with Greber (since Dec. 2016) and Cohen (throughout 2017) and on information on Greber’s homepage, http://www.mariannegreber.at/pro_steven.htm (accessed 4 Jan. 2018). I want to thank Marianne for two long conversations and visits to the site (on 22 Jan. and 16 Sep. 2017) and the material she provided me with. From the vast literature on Cohen, most thought-provoking (albeit not quoted) were the articles by Rebecca Rossen, “Jews on View: Spectacle, Degradation, and Jewish Corporeality in Contemporary Dance and Performance,” Theatre Journal 64.1 (2012): 59–78; Melanie Klein, “Intimate Interactions: Intersektionale Dynamiken als künstlerische Strategie in den Performances von Steven Cohen und Ingrid Wang i Robert Hutter,” FKW (Zeitschrift für Geschlechterforschung und Visuelle Kultur) 56 (2014): 55–68; April Sizemore-Barber, “A Queer Transition: Whiteness in the Prismatic, Post-Apartheid Drag Performances of Pieter-Dirk Uys and Steven Cohen,” Theatre Journal 68.2 (2016): 191–211; and the exhibition catalogue Steven Cohen, Dancing Inside Out (Vienna: Kunsthalle Wien, 2006). Cohen’s complex work can hardly be done justice to in the short paragraph above, thus e.g. allusions to the Nazi persecution of homosexuals are left out here.

43 Botz, “Judenhatz und Reichskristallnacht,” 21.

44 Ibid., 20. Text from the exhibition, “Memory Lab: Photography Challenges History, ” MUSA, Wien, Austria, 28 Oct. 2014—21 Mar. 2015 (materials provided by Marianne Greber).

45 See: Beckermann, Unzugehörig, 86.

46 Gerhard Botz, “The Dynamics of Persecution in Austria, 1938–45,” in Austrians and Jews in the Twentieth Century: From Franz Joseph to Waldheim, ed. Robert S. Widrich (Basingstoke: St. Martin’s Press, 1992), 199–219.

47 See: Jilian Carman, ed. Steven Cohen. (Johannesburg: David Krut Publishing, 2003), 14-15, 21, 23; Steven Cohen, Life is Shot, Art is Long (Johannesburg: Michael Stevens Gallery, 2010), 16; Lebens.art. Cohen Gedenk-Aktion und Diskussion (Lebenssart spezial). ORF (Österreichisches Fernsehen), 12 Nov. 2007.

48 Kuttenberg, “Austria’s Topography of Memory,” 481.

49 Young, “Austria’s Ambivalent Memory,” 92.

50 “Memory Lab.”

51 The 10-minute video is available online: http://www.heure-exquise.org/video.php?id =1407&l=uk (accessed 4 Jan. 2018). It deserves a close reading in its own right. I received the short ORF documentation (Lebens.art) from Anita Reinbacher-Ronacher.

52 I want to thank Ruth Beckermann for our conversation on 22 Sep. 2017.

53 Beckermann, Unzugehörig, 13, 14–16.

54 The discovery of the amateur film was part of the research cooperation Ephemeral Films Project: National Socialism in Austria (2013–ongoing). It is available at: http://efilms.ushmm.org/ (accessed 2 Jan. 2018) as well http://stadtfilm-wien.at/film/104/ (accessed 13 May 2018). The Ephemeral Films Project made amateur films, among other material, accessible in order to supplement and correct the common understanding of this historical period which to a large degree is still dominated by propaganda produced by the Nazis. Beckermann used the very last seconds of the found film.

55 Alexander Horwath, Speech at the opening of Beckermann’s installation, 12 Mar. 2015. http://www.themissingimage.at/home.php?il =4&l=de (accessed 5 Jan. 2018).

56 Ruth Beckermann, The Missing Image, 2015. http://www.themissingimage.at/home.php?il =2&l=en (accessed 4 Jan. 2018).

57 Petschar, “Bekannt und Unbekannt,” 67.

58 Ruth Beckermann, The Missing Image. 2016. (Video-documentary). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbHEEjQVqOQ (accessed 5 Jan. 2018).

59 Artist’s homepage: www.social.gold/D/archiv/zahn_gold_zeit_gold/index.html (accessed 4 Jan. 2018).

60 Uhl, “Das ‘erste Opfer’,” 11.

61 “Déjà-vu.” Videointervention. 2015. https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20150618_OTS0006/dj-vu-eine-videointervention-bild (accessed 13 Jan. 2018).

62 See: Safrian and Witek, Und keiner war dabei, 30–31.

63 Thomas Trenkler,“Beckermann-Installation in Wien abgebaut,” Kurier, 4 Jan. 2016.

64 Friedrich, “Die Rückkehr der Grinser.”

65 Isolde Charim, “Was fehlt bei Alfred Hrdlickas Monument. Arena der Meute,” Taz, 24 Mar. 2015. http://www.taz.de/!207058/ (accessed 8 May 2018).

66 The headline is chosen in allusion to the Rhodes Must Fall protest movement that originated in March 2015 against the Cecil Rhodes Memorial on Cape Town’s University Campus and which questioned public signifiers of post-colonial values. This is discussed by Brenda Schmahmann, “The Fall of Rhodes: The Removal of a Sculpture from the University of Cape Town,” Public Art Dialogue 6.1 (2016): 90–115.

67 Uhl, “From the Periphery to the Center of Memory,” 222.

68 Notably, the more sensitive approaches to the subject stem both from Jews, Cohen and Beckermann, who also make claim to the Jewish right to self-representation. See: Schult and Popescu, “Infelicitous Efficacy.”

69 See: Tanja Schult, “Gestaltningen och etablering av Förintelseminnet i Sverige,” Nordisk Judaistik/Scandinavian Jewish Studies [S.l.] 27.3 (2016): 4.

70 I thank Michael Rainer, conservator at the Federal Monuments Authority Austria, for clarifying the work’s Denkmalstatus (telephone interview, 11 Jan. 2018). According to legislation from 1923, Hrdlicka’s memorial was automatically protected, just because it is a public art work. In 2017 a new inventory confirmed Hrdlicka’s Denkmalstatus, meaning being classified as a memorial worthy of preservation. This status secures the work’s maintenance and protection: it can only be altered or removed with the permission of the City of Vienna (as the work’s owner), the Hrdlicka Trust (as copyright holder), and of course the Bundesdenkmalamt itself. The latter gave permission for Beckermann’s intervention, but would have prevented it from becoming permanent as their mission is to preserve the original intention of protected monuments.

71 Erika Doss, Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 256.

72 Ibid., 257.

73 Ibid., 260, 262.

74 Ibid., 261.

75 Ibid., 264.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- After Images: Kunst als soziales Gedächtnis. Exhibition catalogue (in German and English). Neues Museum Weserburg Bremen. Frankfurt/Main: Revolver, Archiv für Aktuelle Kunst, 2004.

- Austin, John L. How to do Things with Words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962.

- Bachinger, Eva Maria, and Gerald Lehner. Im Schatten der Ringstrasse: Reiseführer durch die braune Topographie von Wien. Wien: Czernin, 2015.

- Beckermann, Ruth. Unzugehörig: Österreicher und Juden nach 1945. Vienna: Locker, 2005 [1989].

- Beckermann, Ruth. The Missing Image. 2015. http://www.themissingimage.at/home.php?il =2&l=en (accessed 4 Jan. 2018).

- Beckermann, Ruth. The Missing Image. 2016. Video-documentary. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbHEEjQVqOQ (accessed 5 Jan. 2018).

- Botz, Gerhard. “The Dynamics of Persecution in Austria, 1938–45.” In Austrians and Jews in the Twentieth Century: From Franz Joseph to Waldheim. Ed. Robert S. Widrich. Basingstoke: St. Martin’s Press, 1992. 199–219.

- Botz, Gerhard. “Judenhatz und Reichskristallnacht.” In Der Pogrom 1938. Ed. Kurt Schmid. Vienna: Picus, 1990. 9–24.

- Bunzl, Matti. “On the Politics and Semantics of Austrian Memory: Vienna’s Monument against War and Fascism.” History and Memory 7.2 (1995): 7–40.

- Bunzl, Matti. Jews and Queers: Symptoms of Modernity in the Late-Twentieth-Century Vienna. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

- Carman, Jilian, ed. Steven Cohen. Johannesburg: David Krut, 2003.

- Charim, Isolde. “Was fehlt bei Alfred Hrdlickas Monument: Arena der Meute.” Taz, 24 Mar. 2015. http://www.taz.de/!207058/(accessed 8 May 2018).

- Cohen, Steven. Dancing Inside Out. Vienna: Kunsthalle Wien, 2006.

- Cohen, Steven. Life is Shot, Art is Long. Johannesburg: Michael Stevens Gallery, 2010.

- Crowds in Vienna during Anschluss. Mar.–Apr. 1938. Film. Baker Family Collection [RG-60.4553], part of Special collection Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Czaplicka, John. “Stones Set Upright in the Winds of Controversy: An Austrian Monument against War and Fascism.” In A User’s Guide to German Cultural Studies. Ed. Scott Denham, Irene Kacandes and Jonathan Petropoulos. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997. 257–86.

- “Déjà-vu.” Video intervention. 2015. https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20150618_OTS0006/dj-vu-eine-videointervention-bild (accessed 13 Jan. 2018).

- Doss, Erika. Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2010.

- Friedrich, Otto. “Die Rückkehr der Grinser.” Die Furche, 5 Mar. 2015.

- Grundmann, Heidi. “Wien ist anders! — Ist Wien anders?” Kunst Intern, 7 Jun. 1990, 46–48.

- Halpert, Marta S. “Die missglückte Provokation.” Wochenpresse, 20 Jul. 1990, 62 (available on Angerbauer-Goldhoff’s homepage).

- Hecht, Dieter J., Eleonore Lappin-Eppel, and Michaela Raggam-Blesch. “‘Anschluss’ — Pogrom in Wien.” In Topographie der Shoah: Gedächtnisorte des zerstörten Wien. Wien: Mandelbaum, 2015. 16–41.

- Horwath, Alexander. Speech at the opening of Beckermann’s installation, 12 Mar. 2015. http://www.themissingimage.at/home.php?il =4&l=de (accessed 5 Jan. 2018).

- Jahraus, Oliver. Die Aktion des Wiener Aktionismus: Subversion der Kultur und Dispositionierung des Bewusstseins. (Das Problempotential der Nachkriegsavantgarden, vol. 2). Munich: Fink, 2001.

- Jenni, Ulrike. Alfred Hrdlicka: Mahnmal gegen Krieg und Faschismus in Wien. 2 vols. Graz: Akademische Druck, 1993.

- Klein, Melanie. “Intimate Interactions: Intersektionale Dynamiken als künstlerische Strategie in den Performances von Steven Cohen und Ingrid Wang i Robert Hutter.” FKW (Zeitschrift für Geschlechterforschung und Visuelle Kultur) 56 (2014): 55–68.

- Krist, Martin, and Albert Lichtblau. Nationalsozialismus in Wien: Opfer. Täter. Gegner. Innsbruck: Studien, 2017.

- Kuttenberg, Eva. “Austria’s Topography of Memory: Heldenplatz, Albertinaplatz, Judenplatz, and Beyond.” The German Quarterly 80.4 (2007): 468–91.

- Petschar, Hans. “Bekannt und Unbekannt: Fotografische Ikonen zum ‘Anschluss’ Österreichs an das Dritte Reich.” In Schlüsselbilder des Nationalsozialismus. Ed. Werner Dreier. Innsbruck: Studien, 2008. 58–69.

- Rossen, Rebecca. “Jews on View: Spectacle, Degradation, and Jewish Corporeality in Contemporary Dance and Performance.” Theatre Journal 64.1 (2012): 59–78.

- Safrian, Hans, and Hans Witek. Und keiner war dabei; Dokumente des alltäglichen Antisemitismus in Wien 1938. Revised ed. Vienna: Picus, 2008 [1988].

- Scheufele, Theodor. Das Mahnmahl am Wiener Albertinaplatz und die Presse. Eine Dokumentation (1978–1992). Vol. 2 of Alfred Hrdlicka. Mahnmal gegen Krieg und Faschismus in Wien. Ed. Ulrike Jenni. Graz: Akademische Druck, 1993.

- Schmahmann, Brenda. “The Fall of Rhodes: The Removal of a Sculpture from the University of Cape Town.” Public Art Dialogue 6.1 (2016): 90–115.

- Schmid, Manuela. “Johannes Angerbauer – Die Rückkehr des Goldes zur Erde.” MA diss., Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main, 1999.

- Schneede, Uwe. “Kein Held aus Erz, nur ein Jude im Staub.” Rheinischer Merkur, 20 Jan. 1989.

- Schult, Tanja. “Gestaltningen och etablering av Förintelseminnet i Sverige.” Nordisk Judaistik/Scandinavian Jewish Studies [S.l.] 27.2 (2016): 3–21.

- Schult, Tanja, and Diana I. Popescu. “Infelicitous Efficacy: Alfred Hrdlicka’s Memorial against War and Fascism in Vienna.” Articulo - Journal of Urban Research (forthcoming).

- Sizemore-Barber, April. “A Queer Transition: Whiteness in the Prismatic, Post-Apartheid Drag Performances of Pieter-Dirk Uys and Steven Cohen.” Theatre Journal 68.2 (2016): 191–211.

- Trenkler, Thomas. “Beckermann-Installation in Wien abgebaut.” Kurier, 4 Jan. 2016. https://kurier.at/kultur/beckermann-installation-the-missing-image-in-wien-abgebaut/173.160.202. (accessed 4 Jan. 2018).

- Uhl, Heidemarie. “Das ‘erste Opfer’: Der österreichische Opfermythos und seine Transformationen in der Zweiten Republik.” Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft (ÖZP) 30.1 (2001): 93–108.

- Uhl, Heidemarie. “Die Transformation des ‘österreichischen Gedächtnisses’ in der Erinnerungskultur der Zweiten Republik.” GR/SR 13.2 (2004): 23–54. https://storiaeregione.eu/attachment/get/up_292_14696102947266.pdf (accessed 12 Jan. 2018).

- Uhl, Heidemarie. “From the Periphery to the Center of Memory: Holocaust Memorials in Vienna.” Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust 30.3 (2016): 221–42.

- Weber, Ina. “Bis in den letzten ‘Wienkl’.” Wiener Zeitung, 24 Sep. 2012. http://www.wienerzeitung.at/nachrichten/wien/stadtleben/488966_Bis-in-den-letzten-Wienkl.html. (accessed 12 Jan. 2018).

- Weiss, Alexia. “Grinser und Gaffer.” Wiener Zeitung, 14 Mar. 2015. http://www.wienerzeitung.at/nachrichten/wien/stadtleben/740556_Grinser-und-Gaffer.html. (accessed 12 Jan. 2018).

- Widrich, Mechthild. “The Willed and the Unwilled Monument: Judenplatz Vienna and Riegl’s Denkmalpflege.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 72.3 (2013): 382–98.

- Wiesenthal, Simon. Projekt: Judenplatz Wien: Zur Konstruktion von Erinnerung. Vienna: Paul Zsolnay, 2000.

- Wise, Michael Z. “Vienna’s Statue of Limitations: The Controversial Holocaust Monument.” Washington Post, 24 Jun. 1990. http://michaelzwise.com/viennas-statue-of-limitations/ (accessed 12 Jan. 2018).

- Young, James E. “Austria’s Ambivalent Memory.” In The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning in Europe, Israel and America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993. 91–112.

- Young, James E. At Memory’s Edge: After-Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000.