Abstract

The recent consolidation of graphic reportage as a genre of graphic non-fiction has brought a distinct non-photographic regime of visual documentation with its own temporality and affective engagement. Graphic documentarism both complicates and relies on the gentrification of the comics as well as the changed ontology of the photograph and has its unique ways of mitigating the risks of distortion and exploitation in covering violent conflicts in distant locations. The two works examined in detail both focus on journalistic mediation of distant conflicts, reporting not only on the places and events of violence but also on their being reported. In Joe Sacco’s The Fixer: A Story from Sarajevo (2004. London: Jonathan Cape), the structural vulnerability of the documentary account due to complex mediation is conveyed through an affective engagement based on intimacy and haptic visuality. This autonomous non-photographic regime of visual documentation is compared to Emmanuel Guibert, Didier Lefévre, and Frédéric Lemercier’s The Photographer: Into War-Torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Borders (2009. New York: First Second), a hybrid reportage combining graphic non-fiction with photojournalism. The comparison suggests that the unique qualities of non-photographic documentation are difficult to maintain when the photographic discourse of factuality not only surrounds the work as a dominant set of expectations, but is integrated into the graphic narrative.

Writing in the aftermath of war and conflict often takes place in a global economy of storytelling, in which a violently disrupted life is represented by a mobile and privileged outsider visiting one of the world’s ‘hotspots’. Graphic narratives are no exception; in fact, the medium of comics has recently become a popular choice for intercultural representations,Footnote1 owing partly to the (false) assumption of its universal accessibility, and partly to the capacity of multimodal representation to transmit nuances of difference simultaneously through its various channels. When graphic narratives mediate between a local atrocity and the global circulation of images and interpretations of war and organised violence, they tend to move from the material culture of violence towards our eventual distant act of consumption through acts of collaborative witnessing that often threaten to collapse into masquerade on the one hand, and disaster tourism on the other. The insider producing an account for a distant audience (conceived as generically global and uninformed or specifically assumed to have the power to intervene and change local conditions) may be merely an interlocutor or the author of the final product. There can also be significant variation in the duration, degree and quality of the mobile outsider’s proximity to the events and the resulting relation to the conflict. All of these affect the distance between the event and its mediated consumption and the types of transformation that occur (such as translation or intercultural interpretation). In the present study, I focus on the latter type of account, in which outsiders author accounts of dramatic conflicts elsewhere and embed their reporting on war and conflict in an equally sharp reporting on the problem and process of reporting itself. The problem of mediating between distant victims and privileged audiences in a non-photographic medium is central to both works under examination: after a detailed analysis of Joe Sacco’s (Citation2003) Sarajevo-based graphic reportage The Fixer, I compare it to a project that involves different media, The Photographer, a hybrid graphic-photographic report from ‘war-torn Afghanistan’ co-authored by Emmanuel Guibert, Didier Lefèvre and Frédéric Lemercier (Citation2003–Citation2006, Citation2009a, Citation2009b). Their different methods, employing and departing from photographic documentation, highlight not only the ethical dilemmas of mediating distant human suffering, but also the new role of the non-photographic image in reporting.

Photo fatigue

The rising popularity of graphic reportageFootnote2 within non-fiction graphic narrative and its current position in journalism is, ironically, a function of its improved cultural prestige. It is, at first glance, an ironic turn of events, since an important part of the recent history of graphic narrative has been its gentrification, its partial absorption into the category of the literary along with the appropriate prestigious forms of production and circulation. (This has long been assumed to be the primary function of the English term ‘graphic novel’. A long-time critic of the term, Art Spiegelman grudgingly acknowledges in a recent interview that it has been an effective ‘marketing term’, the two component words of which convey a ‘double respectability’ [Chute Citation2014, 219].) This process has emphasised the growing distance between long-form comics and the ephemerality and disposability associated with serial publication, a crucial context of the early history of comics. Of course, practices of collection and the typical lifecycle of comics from comic book to trade paperback have mitigated against the disposability of serial publications, but the re-association of the comics with journalism and the press in the form of graphic reportage might still seem to jeopardise the hard-earned high-cultural legitimacy of the graphic novel. It is a modified return, however, that is ultimately rather a beneficiary of the rise and occasional canonisation of graphic novels as serious works. First, the comics’ successful bid for serious journalism depends on its broader acceptance as a serious form and, second, graphic reportage partly grows out of the autobiographical/memoir narrative that has been central to the development of the graphic novel (Caraco Citation2013), because – for reasons intrinsic to the medium – graphic reportage tends to be participatory and reporter-centred.

With reportage, the graphic narrative is reinserted into a very heterogeneous media landscape, drawing on the status of the long-form comic, yet significantly departing from its temporality and modes of reception. Analysing the book as a cultural institution, Carla Hesse (Citation1996, 27) notes that, far more important than the technology of printing, it is a relationship to time that defines the book:

[T]he book is a slow form of exchange. It is a mode of temporality which conceives of public communication not as action, but rather as reflection upon action. Indeed, the book form serves precisely to defer action, to widen the temporal gap between thought and deed, to create a space for reflection and debate.

If this history explains why graphic narrative can afford to return to journalism, it does not explain what makes it attractive as a medium of reportage. In accord with the report’s intermediate position between news and opinion genres in the press, graphic reportage takes on key functions of infographics: visualising the non-optically accessible truth of events and situations. Whereas in infographics this commonly means showing their causal and structural relationships, in graphic reportage it is also their affective, experiential truth linked to lived, embodied experience to which the reporter has access, thanks to being physically present at the scene.Footnote3 This emphasis on the observer’s experience foregrounds the presence, perspective and representational choices of the person(s) representing. By the same token, graphic reportage can represent its subject in terms of its subjective experience with no assumption of unmediated reality. This self-reflexive, mediation-conscious reportage attains its effect partly through its distinction from photographic images as the twentieth century’s primary medium of documentary evidence.

The distinction from the mainstream of journalistic images has a novelty value, presumably a merely transitory edge of an emergent sub-genre embraced by editors in the hope of attracting new readers. Graphic documentary visuality is expected to escape the reinforcement of the expected (in the form of isolated images conforming to received knowledge) and the media blindness resulting from repetition and saturation by overly familiar images. What is expected is more than a new diversion among all too many diversions, however; it is a slower, possibly more contemplative kind of looking, in which the temporality of image making cultivates attitudes akin to viewing pre-snapshot or early photography. The different, though likely, transient capacity of these images to be seen anew would be worth little for graphic journalism, however, if they could not be seen in a documentary function. What makes their documentary function in reporting conceivable – besides the sense that they document a particular experiential aspect of facts – is that the distinction between photographic document and graphic representation has been modified by the changed ontology of the photograph in digital photography. Belgian comics artist Jean Philippe Stassen still aligns the images of graphic reportage with literary reportage in opposition to the photographic, because of the different contracts offered to the reader (‘the images the artist proposes for illustrating – or developing – a fact are the products of his subjectivity. Just like the facts that pass through a writer’s sensibility and his literary style offer a point of view’ [Mauger Citation2009]). In fact, whether one posits this as merely an intensification of conditions inherent in the chemical-based photographic process (Osborne Citation2010) or a clear ontological divide, photos have arguably come closer to being ‘drawn’. The guarantee of their documentary authenticity has long relied primarily on institutional warrants rather than technological necessity (Fetveit Citation1999, 789, 797–798), and digital data processing has brought new issues, such as visually undetectable pixel-level modifications, to be covered by the evolving norms of processing between capture and display (Osborne Citation2010, 65). There may be a disjunction or lag, however, between knowledge and response here: despite the ‘self-consciousness of the potentially illusory character of the photographic image’ that brings the warrants of the graphic and photographic documentary image closer to each other, one’s reaction to images presented as photographic facts may linger, and unlearning it may take much longer (as long as a sense of the photograph as a ‘transparent’ image-trace survives). It is in this transition that the graphic documentary image has made its recent advances.

‘I’d barely traced the edges of his secrets’: The Fixer

Joe Sacco’s entire oeuvre – his best-known body of work on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the break-up of Yugoslavia as well as other reports – engages with the process of collaborative witnessing, displaying an awareness of the limitations and complexities of discursive access and understanding, and the ethical dubiousness of trading on other people’s pain and suffering, while attending to the potentially dangerous and noble task of making them seen and heard. In a sense, Sacco’s career can itself be taken as a dramatisation of this issue – adopting the medium of graphic reportage as an exile from the ineffectualness of traditional journalism, the American homeland and its media institutions, while nevertheless enjoying the privileges of his intermediary position. What makes The Fixer unique and particularly memorable within the oeuvre is that it makes journalistic mediation the central theme of the work. It offers Sacco’s most sustained and complex enquiry into the difficulties of finding a professionally authentic and ethically responsible position vis-à-vis one’s subject in journalism and within a haptic aesthetic of non-photographic documentary work. By employing the unique qualities of the medium to engage questions of privilege, mobility, accuracy and authenticity, The Fixer focuses on the elusiveness of a non-exploitative intimate access to one’s subject. It is important to note that what is at issue here is not graphic non-fiction in general, but the specific genre of reportage, in which the perception and physical experience of persons, locations, events and actions is transformed into an account for those unable to experience it first-hand. Tellingly, Sacco gave up a graphic non-fiction project on the Vietnam War, because he had no first-hand experience to rely on (Adams Citation2008, 124).

The Fixer goes beyond the usual acknowledgement of the reporter’s subjective, interpretive view (most often signalled by the intra-diegetic representation of the reporter’s avatar) by choosing two mediators as his twin protagonists and setting up a narrative structure that focuses primarily on the chain of mediation. The dual protagonists are Sacco, the journalist, and Neven, his one-time local informant and organiser, his ‘fixer’; and in typical aftermath reportage fashion, the journalist revisits Sarajevo years after the conflict. In the alternating stories of Neven’s war experiences and the journalist’s interviews with him years later, the book examines the flow of information through a chain of intermediaries and their transactions of access and interpretation. It is important to distinguish when general problems of intercultural reportage are merely exemplified by visual reportage and when non-photographic reportage inflects and mitigates these problems in unique ways.

The processes of information gathering are quite elaborate in some of Sacco’s other works; at times, they are even more intricate than in The Fixer, with more types of contributors, whether or not they are explicitly represented in the text. He explains, for example, about Footnotes in Gaza:

I had read bits of Ben Gurion’s testimony, but one of my Israeli researchers found a newspaper that reprinted his entire response to the incident at Rafah…. I read a snippet of the story of Mark Gefen, an eyewitness soldier who talks about a ‘human slaughterhouse’. It was footnoted to a magazine back in the eighties. Someone found it, and then my editor translated the whole document for me. (Chute Citation2014, 144)

Translators and interpreters are also prominent figures in much of Sacco’s oeuvre, their re-articulation of personal testimony foregrounded rather than transparently elided in the text. Brigid Maher notes several visual techniques for safeguarding the reader’s awareness of the translation process, and preventing the original utterance from being supplanted even when no bilingual text is presented: visually depicting the translator, including the translator’s reporting phrases, and alternating speech balloons between witness and translator, both of whom are depicted as speaking. This ensures that the complexity of a complex bilingual oral exchange is residually present despite its double condensation into its monolingual shortened written version due to the constraints of the speech bubble (Maher Citation2011, 126). Although The Fixer forsakes some of this diversity of contributors to journalistic fieldwork and research when it compresses them into the larger-than-life character of the fixer and Sacco’s reporter avatar, it compensates by painstakingly dissecting the chain of communication and its distortions and dependencies that are belied by the smooth, unified representation in a text creatively controlled by a single author.

Between us and the city that would not speak, there is Sacco and his fixer. Sacco, who provides the reader access to the story, is in a position that replicates ours: even though he is on the ground, his access and understanding are largely based on the fixer’s selections and interpretation, quite problematically so, as the fixer’s motivations and reliability are increasingly called into question (by common sense and witnesses who refuse to corroborate his accounts). The fixer’s position and financial gain are born out of this dependence; otherwise it would be possible to eliminate him. There is a tension between fieldwork-based journalistic authenticity – the wealth of verifiable factual detail and the rigorous marking of time through a visual black-and-white separation of then and now in the text, as the ‘journalist’s standard obligations – to report accurately, to get quotes right, and to check claims – still pertain’ (Sacco Citation2012, xii) – and the structural vulnerability of the documentary account, due to the tenuousness of the interpretive chain of information at the end of which the public consumes representations of remote events. The focal shift from the subject of war to that of war reportage is clear from the decision to keep and study this increasingly questionable source and incorporate his contested narration in a text otherwise employing rigorous journalistic methods of fact-checking, recordkeeping and multiple sources. Unless this problem is the primary subject of the book, it would make little sense to compromise the journalist’s work.

The book stages this problem of access as the scene of the fixer’s birth, instantly embedding his monetising of privileged access in the commoditisation of human suffering as a news item: an Australian television crew filming kids playing in the garbage. This is the master image of ineffectual and ethically dubious global journalism that Sacco’s own enterprise is measured against. The crew takes up Neven on his challenge to film the real front line and rewards him for his services, thereby informing him of the market value of his provision of access. This is one of several occasions in the narrative when the disempowerment of locals is expressed by association with waste and a denial of adult agency either by infantilisation or old age. The fixer’s subordination to the foreign correspondent is analogously compared to a subhuman status contested by Neven when he is not allowed to join a journalist at dinner (‘I asked him, ‘“Do you have a leash?/“Maybe it would be more convenient”’ [Sacco Citation2004, 50]). This subordination and association with waste always entails a reduced capacity for mobility or even complete immobility, and it becomes increasingly clear that the exchange value of information cannot be readily converted to mobility and agency. In fact, the narrative closes with Neven still dreaming of his passport and ‘getting his ass out of here’/‘As soon as possible’ (Sacco Citation2004, 104). If it were not obvious to the reader what it means to break this statement into three identical panels, the panels of stasis and eternal longing (‘as soon as’ probably meaning ‘never’), our final view of Neven is from a rising bird’s-eye perspective. We are literally dropping him, and the narrator’s small text boxes fall out of the panel frame and towards the ground, like falling leaves, bombs, or litter floating down into the giant wastepaper basket of the aerial cityscape.

Thus, the chain of procuring and transmitting knowledge not only allows distant publics to inform themselves, despite the occasional human error,Footnote4 but also appears from time to time as a far more sinister chain of trade transactions between differently empowered partners in which the disempowered offer themselves as subjects, if necessary masquerading at whatever is most likely to be consumed. This commentary is most clearly offered in two scenes when Neven recounts hiring prostitutes for journalists. In the first scene, a woman is hired to have sex ‘with a party of seven journalists’ (Sacco Citation2004, 7) and, in the second, a prostitute is hired to pose naked in a German photographer’s photo essay on ‘Nightlife in Sarajevo’ (60). In both episodes, the jobs of the journalists, the fixer who ‘arrange[s] whores’ for them, and the (professional or occasional) sex worker are cuttingly intertwined under the concept of labour, reassuringly called ‘completely normal’ (7) and just ‘another job’ (60). The transaction is explicitly part of producing media coverage in the second scene, but the first creates an equally strong connection between prostitution and the fixer–reporter–reader relationship, as the exchange is clearly and immediately juxtaposed with the relationship between the journalist and his fixer, ‘This conversation is costing me 100 dm, but 100 dm does not begin to fill the crater of my obligation to Neven’ (8).

There are also two less obvious, but equally meaningful, connections between sexual exploitation and journalistic transactions here: the intersection between felt experience and external observation and the monitoring of the flow of information. Neven recounts: ‘Afterwards she said she felt suicidal. I said, “2000 DMs. You can live for a year on that.”’ The reported exchange reflects two sharply conflicting senses of living in terms of exchange value and the dignity of human life. It is also a question whether the transaction would merely take place, protected from passing into discourse, or whether it would be transmitted as a story (7). ‘She was worried that her boyfriend or brother would find out. I said, “If they find out it will be because you tell them.”’ Our finding out, then, is at the troubling intersection of her ultimately betrayed secret and the voicing of her felt pain. This is the model of narrative exploitation and service that the whole book grapples with.

That said, when Sacco’s work, and specifically The Fixer’s ‘transcultural coverage’ of traumas is read as part of a late capitalist ‘trauma economy’, or ‘the economic, cultural, discursive and political structures that guide, enable and ultimately institutionalize the representation, travel and attention to certain traumas’ (Tomsky Citation2011, 50, 53), the power differentials and exploitative aspects of the interchange seem to obscure the intimacy and emotional engagement that is also a genuine potential of the re-articulation of painful testimony and the haptic visuality of graphic narrative. Significantly, this is where the nature and consequences of the graphic medium substantially inflect the process of reporting; the more an analysis brackets this as a minor aspect of reporting in the broader framework of economy or journalism, the more bleak the resulting assessment. A ‘haptic aesthetic’ is the most concretely signalled by tactile contact in Sacco’s Palestine (Scherr Citation2013, 25), but it informs his work and, indeed, the entire medium of the comics more generally, where the transmission of embodied experience happens through the book as a tactile ‘discursive-material node’ bearing the traces of drawing, handwriting and lending itself to holding and haptic browsing rather than a merely symbolic site for author/reader interactions (Orbán Citation2014, 181).

In other words, while Tomsky convincingly argues that ostensible exchanges of resources and information are co-dependencies and exploitations of the economic value of trauma in response to the international demand for mediatised trauma in the form of ‘intense’ yet ‘fleeting’ media fascination with the crisis of the day (Tomsky Citation2011, 54), they are not simply that. Integrating stories with visual reporting more pervasively than the logic of illustration would justify can open dominant scripts of geopolitical events to the everyday, the liminal visual presence of the settings of daily life and its ‘constant hum of practices’, a ‘proximity to the everyday outcomes of geopolitical events’ (Holland Citation2012, 110, 112). When this is the case, even products of fleeting media fascination can open a space of contestation as their ‘narrative practices make possible oppositional readings of dominant geopolitical scripts’ (Holland Citation2012, 108). The fact that the author retains the privileged position of those able to buy disaster stories and images for distant consumption does not limit his account to an articulation of elite-centric official narratives in popular culture. If there is a genuine contestation of dominant narratives, the ‘simplifying scripts’ of geopolitics through ‘low-level interactions’ (Holland Citation2012, 108, 113), conversations and personal interviews, a space of intimacy and empathy can open between the trauma on site and its institutionalisation.

Graphic reportage is also a laborious process that requires a prolonged connection with its subject in an embodied relationship. It is a particular kind of creative reconstruction that has its own intimacy because of the time involved. When Sacco says in an interview that ‘[d]rawing is a lot harder than being there’ (Wilson and Jacot Citation2013, 152), the comparison is obviously not to primary victim experience, but to his own witnessing on site. Even so, this seems a self-indulgent statement at first glance, but it is worth paying close attention to the language that articulates the emotional toll of drawing the images of atrocity again and again: there is a relationship to the body and the imagination that is hard to articulate, important, yet skirts close to appropriating the victims’ experience. ‘You inhabit everything you draw’; ‘you sort of have to appreciate holding up a bat to hit someone over the head’; ‘you kind of have to go through the motions’ – the embodied experience of imagining an experience in which whatever feels close is fundamentally not yours, this is what all the ‘sort ofs’ and ‘kind ofs’ in Sacco’s responses mark (Wilson and Jacot Citation2013, 152). It is a methodologically intimate reconstruction that is ‘weird’ precisely because it stops short of over-identification. (Once over-identification happens, the experience is felt, rather than kind of appreciated in a weird way.) All of this matters also because there is kind of a residue of this appreciation in the embodied reading of graphic reportage. This kind of going through the motions is attenuated further in reading, since the reader clearly does not inhabit a drawn subject in a similarly prolonged, intimate way – it is a key practical difficulty of graphic reportage journals that we read and current affairs develop much faster than they can draw – and yet the reader’s difficulty in claiming the haptic visuality of reading as an experience is not unlike the graphic artist’s. Sacco aims at this intimacy of nevertheless unclaimable experience: ‘I can actually show [that] and help the reader sort of visualize themselves in that space’ (Wilson and Jacot Citation2013, 147, emphasis added). It is a mistake to argue that the ‘stylisation of reality’ creates a distance that controls this type of ‘affective engagement’ in graphic narrative, as has been suggested in an analysis of French comics artist Etienne Davodeau (Le Foulgoc Citation2009, 88); engagement is sustained more by the tactile nature of visuality and its sense of proximity in the comics rather than immediacy.

The page describing a visit to Neven’s elderly aunt back at his apartment (owned by the aunt and legally lost by Neven in the end) and a subsequent visit to a bar are a characteristic encapsulation of this evocative power of graphic documentation, the pervasive setting informing its visual communication of disaster, and the intimacy of haptic vision combining empathy with a sense of difference – our mobile protagonists wading in a wasteland of dirt and junk they are in touch with, yet are defined by not being part of. The different states and qualities of life, the relationship of value and waste, seeing and being seen, and relative powers of mobility are non-photographically documented. A page of five expository panels about the aunt, her apartment and her being ‘the main reason’ Neven is staying in Sarajevo is followed by a page horizontally split between two large panels (Sacco Citation2004, 45–46). The top image is an overhead view of the living room, where the aunt is lying on a couch by the wall surrounded by unimaginable clutter, used dirty plates, bottles and cans, dirty clothes. It is sharply divided by a graphic distinction of tone and shading that is irreconcilable with any photographic representation of the space: the room falls into the coextensive spaces of mobility and stasis. As we know that Neven also lives in this wasteland (5), this representation shows that mobility is paramount: you are not part of it as long as you can leave it, which they promptly do.

It is not a fantastic image – all shapes and forms obey the laws of physics and perspective and underwrite the non-fiction contract of the text – but it is profoundly counter-photographic in its violation of the rules of light. The two men dynamically walk out of the sea of decay and disorder; she is included among the abandoned useless objects, a thing that can be seen by the visitors, but cannot look back, and is indeed on the verge of becoming unseen in the meticulously drawn layers of disarray on all horizontal surfaces of the room. The difference between agency and its lack is absolute, and the state of life as waste and object has no direct connection to the state of autonomous life (she is not talked to, only talked about). It is visually inconceivable that she is alive, yet she is (‘the main reason I’m staying in Sarajevo’) and she can’t (‘see a thing’), and this living is what is paradoxically conveyed in the image – not a metaphoric living death, but an actual life lived this way. In contemplating and scanning the minutiae of her world, the reader can un-see her objectification and see her life (a life lived as something that looks like an object but is not, though it/she has no power to make this known). Neven’s comment that contests living for others in the name of autonomy (‘I have my own life to live’) ironically applies to the old woman as either a sentence of life imprisonment or as the affirmation of the dignity of human life despite all. Combined with the bottom image, in which Neven turns out to be unable to get a passport and leave, his autonomy and dynamic movement turn out to be severely limited and relative, and the scene is positioned within the story of its transmission (to the passport-holding journalist eventually narrating it to us). Inscribed into the pages are relationships of power derived from the differentials of quality of life, agency, value and mobility, including our own.

If representation is a collaborative product here – and there is a strong sense in The Fixer that it is, despite the single author and copyright holder – there is at best a shared ownership of the story, in which lived experience and its account are inextricably fused. Once ‘the story’ is both the events and their account, and the account has been formed by the artist, not taking it or giving it back is only viable as an ideal horizon for ethical obligation, an impossibility one must aim at. This is akin to the ideal or limit concept of the ‘ethics of the spectator’, as posited by Ariella Azoulay in the context of photography (Citation2008, 340), which at least in this respect lends itself well to the documentary graphic images discussed here: the potentiality of the image to be seen ethically in the future through the inevitable ‘gap between the stated aims and what has actually taken place in the encounter between photographer, photographed and camera’ (124) and thereby turn into a claim, a grievance and ‘redefine limits, communities, and places’ (120). Sacco explains the ending of Footnotes with the artistic gesture of silence marking the wish to – once again, ‘in a way’, ‘kind of’ – return ‘the whole story’:

Had I sterilized this whole event by the process of looking at it? Sterilized the component parts for myself? In a way, I kind of just wanted to give the whole story back to the people who suffered…. I kind of knew the grander picture. But those individuals are the ones that went through it. (Chute Citation2014, 152)

Yet listening, reimagining, reconstructing and even silence can only return the story to the ‘people who suffered’ via the reader’s empathy and changed understanding (the ethics of the spectator). If the spectators within the chain of transmission are ‘at best imperfect copies or representatives’ of this ideal, this neither invalidates the ethical duty to aspire to it, nor conceals the possibility of actual complicity. The Fixer is realistic and rather disillusioned in this respect: there is no access to an unfiltered reality of suffering, and there might always be a more trusted informant than one’s current informant. In the end, Neven himself is wrapped in the account of a trusted informant wrapped in the narrator’s account and the authenticity of his words is restored at the very moment he is finally too far to speak, turning into a vanishing point with all ‘the people who suffered’. And yet, they are not vanishing, as the journalistic work of the book has established them as living their own lives before and beyond ‘the story’ intersecting with ours. The last of the ‘Last Words’ are the author’s ‘most thanks’ to an extra-diegetic Neven, which ought to remind us: there is a perspective from which we are vanishing too, becoming smaller and smaller to participants in a conflict we might never truly understand – the question is whether as human beings in the face of extreme violence or as privileged members of a richer, more mobile community at leisure to contemplate in wonderment a scene of distant suffering.

Lines, gaps and contact sheets: The Photographer

The Fixer is a representative example of the most sophisticated attempts at establishing an autonomous non-photographic regime of visual documentation. It is completely graphic and contains none of Sacco’s photographic notes (it is known from special editionsFootnote5 and interviews how much he relies on photos for the authentic recreation of scenes, architectural details, clothes, etc.). The book includes no representation of such reference photos being taken; the reporter’s professional tools of documentation that do appear at times are the notepad and the tape recorder (Sacco Citation2004, 20, 92), the latter playing an important role in the narrative as well. The photographic is completely absorbed and subordinated to the graphic, most memorably in the hand-drawn representation of a single personal photo kept by the fixer to remember his war buddies and prove his heroic action against overwhelming force (34, 100). The autonomy of graphic documentation is affirmed by refusing to let the photo break through its homogeneous field, and the photo’s claims to unique mnemonic and documentary power are made increasingly tenuous in the course of the narrative: in an early scene, the fixer successfully uses the photo as proof of his participation in a unit during the war, though he fails in expanding the photo’s power to prove his account of specific unlikely actions merely by association (‘It was taken shortly before we went into action against the 43 tanks’ [34]). Later in the narrative, the photo breaks down completely as either a mnemonic aid or documentary proof: he takes out the photo of his comrades in vain, unable to remember their names.

Of course, even such a consistent effort to construct an autonomous regime of non-photographic documentation inescapably works in the context of photography as a privileged discourse of truth and factuality over the past century. It surrounds the work as a dominant set of expectations in the media landscape of its production and reception, and it is refused in counter-photographic images, but it is not part of the work. Once photographic and non-photographic media of reporting share a space within the same work, however, the role of graphic reportage changes significantly. How does the more than occasional combination or possibly integration with photography alter the documentary effectiveness of the graphic medium, its role in reporting, and the intimacy associated with its haptic aesthetic? The hybrid graphic novel The Photographer constructs a graphic non-fiction narrative around the much earlier photo documentation of a medical mission of Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières; MSF) into Afghanistan in 1986. The hybrid text is once again a reporting on reporting; a photojournalistic assignment originally aimed at validation through documentation (securing public representation and funding for MSF) is reported in the narrative by comics artist Emmanuel Guibert and colourist Frédéric Lemercier based on Guibert’s lengthy interviews with the photographer.Footnote6 The unfolding story of the mission is told through the story of its recording. The book – serially published in French in 2003–2006 and collected in a volume in 2008 – thus combines, at least at first glance, a comics narrative of Didier Lefévre’s participation in the MSF mission with a detailed photo essay; and the two seem to be woven together seamlessly into aftermath reporting formulated as a first-person memoir on behalf of the photographer. The story of the preparations, the difficult trek across the mountains to set up a hospital and the even more dangerous return journey that nearly kills the photographer is laid out harmoniously; graphic and photo sequences seem to flow into each other in a steady rhythm, joining forces to tell a convincing and affecting story.

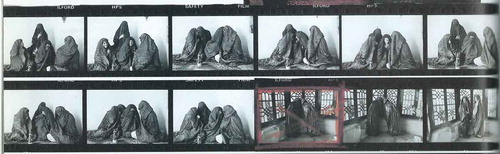

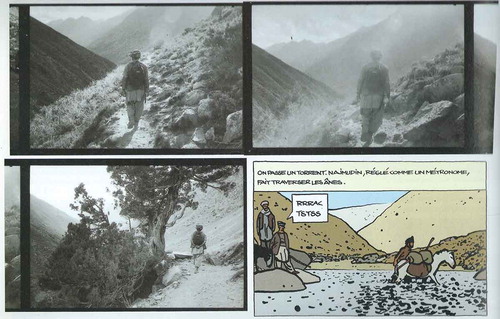

The reading experience, however, is quite different. The relationship between the graphic and the photographic is unsettled and remains so throughout the work. Does the chronology of the project make the graphic narrative a running secondary commentary on a photo essay, resuscitating a core material languishing in obscurity for many years due to a lack of media interest, or rather the media’s preference for more shocking and spectacular images? Or, given that the photos are not quite a work in a strict sense but at least partly the raw material from the photographer’s workshop, is what we are looking at primarily a comic book illustrated and authenticated by photographic images? These are relevant questions even when a single author produces and combines these media more concurrently, but they are intensified here by the different times and authorities of the creative components and, as already mentioned, by the inclusion of two distinct types of photographic sequence. Besides enlargements, that is photographic images extracted from the immediate context of their production, the book includes an abundance of photographic images in various, sometimes extreme, degrees of multiplicity and variation, presented as contact sheets. Strips of raw images normally intended for image review rather than viewing, in the original size or somewhat enlarged, but still framed by the film material itself, introduce problems of image status and image relationships that deeply trouble the flow and texture of the narrative (). These are multitudes of versions, alternative views and moments of a subject that do not necessarily involve seriality. They depict many successive moments of an event or scene, often representing different settings of the technical apparatus rather than meaningful phases. They are variants that are not meant to work together but an array from which the best image can emerge – pre-selections from the real resulting from some ratio of intention and accident before they have been subjected to a selection based on seeing the image produced. The frequent red lines marking the frames to enlarge and occasional red crop marks visualise this subsequent selection, which is dissolved in the inclusion of all images, whether selected or unused. Formally, these contact sheets convert into panels with deceptive ease, yet their ‘panelisation’ belies the fact that they do not operate by the logic of panel sequencing and their multiplicity of moments explodes the logic of panel sequencing. There are exceptions to this, when individual images from a contact sheet are selected, extracted and rearranged into a real sequence of photographic panels, such as the two-page sequence of a previously explained special Afghan custom of negotiating by hand (Guibert, Lefèvre, and Lemercier Citation2003, 7–8). Size also introduces a dilemma: unlike large mountain landscapes, village scenes and portraits, these actual size and moderately enlarged contact sheet images are too small to see unaided by a magnifier. Are we meant to see them, if necessary, by poring over them with a magnifying glass, or should we be content to have a passing view of the tiny details with even tinier variations as proof of the images’ and their subjects’ existence?

Figure 1. Le Photographe – Tome 1, p. 34, detail.

The result of these questions in the reading process is a very dynamic sequence of dizzying displacements. Panel sequences, photo enlargements and ‘panelised’ contact strips significantly shift the logic of organisation, status, and mode of viewing. Some analyses have maintained that this dynamic is a harmonious and collaborative narrativity, where ‘[i]n no way do the abrupt shifts to a photographic register disrupt the coherency of the storytelling’ (Pedri Citation2011). In fact, the shifts are even further amplified by the disproportionate attribution of all verbal narration and dialogue to the graphic narrative (as opposed to photo captions or writing on photos). This is maintained throughout the text, as even what could easily be photo captions are rigorously presented in text-only comic panels. The type of explicit narration that names and contextualises characters and events, that propels the story forward and establishes causal relations is provided solely by the graphic narrative. (A four-page wordless photo sequence of a crucial near-death experience is strictly separated from the surrounding graphic narration, in which the story of taking the photos is constructed in words and increasingly abstract drawings []). This split has important consequences for both the photographic and the graphic elements. The photos neither have an autonomous narrative function because they narrate so little (virtually never moving the story along), nor are they simply illustrative or authenticating since they appear far too excessively to illustrate and authenticate. Instead of doing their own narrating or illustrating, they take on a silent, mysterious character, pulling one out of the narration and establishing a deeper world, one that recedes much further into the background even in the case of identical scenes (). This ontological and functional split between the graphic and photographic explodes the narrative time and time again. As the narrative is followed, one keeps plunging into the silence of the photograph, then pulled back into narrative proper, slipping between modes of reading and viewing. This limited narrative capacity is not inherent in the photographic image as a paradigmatic case of the monochronic still image, but rather in its specific use here. Still images, including photographic ones, can easily form narratives in sequence (though their appearance as single objects or parts of a series depends on various generic and contextual factors), and even a single still image may evoke or imply narration (Kibédi Varga Citation1989a, 35, Citation1989b, 96–98; Wolf Citation2002, 96), where any ‘distinct narrative content’ of a photograph must result from an intended ‘association between the image and the narrative’ (Currie Citation2006 [1999], 146). If this is not the case here, it is not due to any intrinsic narrative incapacity of the photographic, but a relative and relational surplus attained through juxtaposition with an explicitly narrative and discursive graphic representation. In the case of the enlargements, it is a combination of silence and an excess of factuality: the photograph’s ‘difficulty with selectivity’ (Adams Citation2008, 187) creates a reality effect through automatically captured detail. This is not necessarily a validation of the truth discourse of photography, but a more powerful enclosure and inward-turning of the framed image. The photographic is often used here with the ‘punctuating capacity of the photographic frame’, ‘bringing readers to pause and break away from the familiar storyworld’ (something Nancy Pedri [Citation2014, 62] attributes to photo frames in multimodal life-writing elsewhere). It is the rigorously maintained muteness of photos within their frames that endows specifically the photographic with the kind of deceleration or pause effect that often characterises silent, wordless (drawn) panels or pages in graphic reportage (Banita Citation2013, 57).

Figure 2. Le Photographe – Tome 3, p. 57, detail.

Figure 3. Le Photographe – Tome 1, p. 52, detail.

For the secondary reporting of the graphic narrative, the old photos of street scenes in Peshawar or female members of the mission posing in ‘chadri’ might well be facts of documentation that could be seen as pictures of photos, staying on the plane of graphic reporting. Even though one might expect this attitude to be supported by the visibility of the non-transparent materiality of the film roll (betraying the production of the image), the photos derail this smooth interaction precisely through their (far from inevitable or medium-determined) under-narration. Rather than establishing a bedrock of truth or authenticity, their muteness indicates a reserve of the unvoiced, a hinterland of the unseen that recedes to the background and demands to be seen, voiced and understood. This actualisation is an ethical response to the event of photography, which

can only be suspended, caught in the anticipation of the next encounter that will allow for its actualization: an encounter that might allow a certain spectator to remark on the excess or lack inscribed in the photograph so as to re-articulate every detail including those that some believe to be fixed in place by the glossy emulsion of the photograph. (Azoulay Citation2012, 25)

The collaborative work of graphic journalism hinged on the collaboration between local informants and distant visitors in The Fixer. Although The Photographer conveys a hierarchy of relative knowledgeability, in which rather clueless documenters try to grasp the meaning of what they are recording from experienced outsiders and locals, the collaborative work the book highlights inheres primarily in the unsettling collaboration between media, switching between alternatives that keep dislodging each other and showing how different media create different versions of reality.

The reason this is more generally significant for graphic reportage is that it shows the fragility of its non-photographic aesthetic, how much the potentiality of tactile visuality and a sense of proximity and affective engagement depends on an extensive text and immersive reading. Many sequences with such potential exist in this hybrid text, including the powercut and the ensuing heat at night, the team’s arrival into Afghanistan at night, or the most prolonged sequence of the photographer’s near death by exposure on his independent return journey (Guibert, Lefèvre, and Lemercier Citation2003 10–11, 36–37, Citation2006, 42–71). The more prolonged, the more powerful they are, yet even so they cannot sustain the type of non-photographic documentariness that operates in a fully graphic reportage. It is noteworthy that these formally identical shorter sequences cannot accomplish this when the graphic narrative is built on the photographic as a way of seeing rather having it as the inescapable horizon of dominant expectations of documentation and when it is integrated with photographs that cannot be absorbed as occasional illustration. New and fragile graphic reportage might be compared to the legacy of the photographic regime of documentation, yet the transformation of the photojournalist’s never seen photos is perhaps illustrative of a more general potential: despite photography’s apparent power to dislodge the graphic mode of reportage, it is the graphic narrative and its discursive difference that revives and mobilises something that has become lost, inert and inarticulate in the photographic record.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katalin Orbán

Katalin Orbán is Assistant Professor at Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest. Her previous affiliations include Harvard University and the National University of Singapore. Her works on graphic narrative, contemporary transformations of reading and the book, and the ethics and politics of social memory have appeared in the ‘Comics and Media’ special issue of Critical Inquiry, Representations and her Ethical Diversions: The Post-Holocaust Narratives of Pynchon, Abish, DeLillo, and Spiegelman (Routledge).

Notes

1. An entire recent volume devoted to this potential is Denson, Meyer, and Stein (Citation2013).

2. As the gradual and so far fairly localised emergence of a unique potential, rather than a mass movement, particularly visible in the United States and France, this increase is significant in relative terms. Patrick de Saint-Exupéry comments in 2010: ‘There is only one Joe Sacco in the United States, as far as I know. There aren’t 100 000 out to anchor graphic work in the real. In France or in Belgium, there are also some authors who are interested in this topic. But they know that it is not an easily explored vast virgin territory. It is a space that is open, but everything is under construction’ (Benaïche and Mauger Citation2010, my translation).

3. In some cases, works of graphic journalism strategically integrate comics and infographics (maps and diagrams), as in Dan Archer’s (Citation2013) ‘Nepal: “I was 14 when I was sold”’, a piece on human trafficking from Nepal produced for the BBC.

4. ‘By admitting that I am present at the scene, I mean to signal to the reader that journalism is a process with seams and imperfections practiced by a human being – it is not a cold science carried out behind Plexiglas by a robot’ (Sacco Citation2012, xiii).

5. The special edition of Safe Area Gorazde (Sacco Citation2011) not only includes some of the author’s reference photos, but presents a side-by-side comparison of the photos and the panels.

6. The interviews between the two were subsequently published in the separate volume Conversations avec le photographe in 2009 to commemorate Lefévre’s untimely death (Guibert, Lefèvre, and Lemercier Citation2009a). The book is illustrated with his photographs taken between 1986 and 2006.

References

- Adams, J. 2008. Documentary Graphic Novels and Social Realism. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Archer, D. 2013. “I Was 14 When I Was Sold.” BBC News, April 22, 2013. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-22250772

- Azoulay, A. 2008. The Civil Contract of Photography. New York: Zone Books.

- Azoulay, A. 2012. Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography. London: Verso.

- Banita, G. 2013. “Cosmopolitan Suspicion: Comics Journalism and Graphic Silence.” In Transnational Perspectives on Graphic Narratives: Comics at the Crossroads, edited by S. Denson, C. Meyer, and D. Stein, 49–65. London: Bloomsbury.

- Benaïche, M., and F. Mauger. 2010. “Interview with Patrick de Saint-Exupéry. “Revue XXI: la preuve par le récit graphique.” Mondomix: Le magazine des musiques et cultures dans le monde, February 3: n.p. http://www.mondomix.com/news/revue-xxi-la-preuve-par-le-recit-graphique

- Caraco, B. 2013. “Reportage(S): Intimité du journalisme et de la bande dessinée.” nonfiction.fr, September 27, 2013. http://www.nonfiction.fr/article-6712-reportage_s__intimite_du_journalisme_et_de_la_bande_dessinee.htm

- Chute, H. L. 2014. Outside the Box: Interviews with Contemporary Cartoonists. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Currie, G. 2006 [1999]. “Visible Traces: Documentary and the Contents of Photographs.” In Philosophy of Film and Motion Pictures: An Anthology, edited by N. Carroll, and J. Choi, 141–153. Malden, MA: Blackwell. 2006.

- Denson, S., C. Meyer, and D. Stein, eds. 2013. Transnational Perspectives on Graphic Narratives: Comics at the Crossroads. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Fetveit, A. 1999. “Reality TV in the Digital Era: A Paradox in Visual Culture?” Media, Culture & Society 21 (6): 787–804. doi:10.1177/016344399021006005.

- Guibert, E., D. Lefèvre, and F. Lemercier. 2003. Le Photographe: Tome 1. Marcinelle, Belgium: Dupuis.

- Guibert, E., D. Lefèvre, and F. Lemercier. 2004. Le Photographe: Tome 2. Marcinelle, Belgium: Dupuis.

- Guibert, E., D. Lefèvre, and F. Lemercier. 2006. Le Photographe: Tome 3. Marcinelle, Belgium: Dupuis.

- Guibert, E., D. Lefèvre, and F. Lemercier. 2009a. Conversations avec le photographe. Marcinelle, Belgium: Dupuis.

- Guibert, E., D. Lefèvre, and F. Lemercier. 2009b. The Photographer: Into War-Torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Borders. New York: First Second.

- Hesse, C. 1996. “Books in Time.” In The Future of the Book, edited by G. Nunberg, 21–36. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Holland, C. E. 2012. “‘To Think and Imagine and See Differently’: Popular Geopolitics, Graphic Narrative, and Joe Sacco’s ‘Chechen War, Chechen Women’.” Geopolitics 17: 105–129. doi:10.1080/14650045.2011.573512.

- Kibédi Varga, A. 1989a. “Criteria for Describing Word-and-Image Relations.” Poetics Today 10 (1): 31–53. Spring, doi:10.2307/1772554.

- Kibédi Varga, A. 1989b. Discours, récit, image. Liège, Belgium: Pierre Mardaga Éditeur. 1989.

- Le Foulgoc, A. 2009. “La BD de reportage: le cas Davodeau.” Hermès 54: 83–90.

- Maher, B. 2011. “Drawing Blood: Translation, Mediation and Conflict in Joe Sacco’s Comics Journalism.” In Words, Images and Performances in Translation, edited by R. Wilson, and B. Maher, 119–138. London: Continuum.

- Mauger, L. 2009. “Le journalisme est-il dans la bulle?” Revue XXI: L’information grand format, February 15: n.p. http://www.leblogde21.com/article-27885090.html

- Orbán, K. 2014. “A Language of Scratches and Stitches: The Graphic Novel between Hyperreading and Print.” Critical Inquiry 40 (3): 169–181. Comics & Media, edited by Hillary Chute and Patrick Jagoda, doi:10.1086/677340.

- Osborne, P. 2010. “Infinite Exchange: The Social Ontology of the Photographic Image.” Philosophy of Photography 1 (1): 59–68. doi:10.1386/pop.1.1.59/1.

- Pedri, N. 2011. “When Photographs Aren’t Quite Enough: Reflections on Photography and Cartooning in Le Photographe.” ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies 6 (1): n.p. http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v6_1/pedri/

- Pedri, N. 2014. “Empty Photographic Frames: Punctuating the Narrative.” Image and Narrative 15 (4): 60–76. http://www.imageandnarrative.be/index.php/imagenarrative/article/view/562

- Sacco, J. 2004. The Fixer: A Story from Sarajevo. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Sacco, J. 2011. Safe Area Gorazde: The Special Edition. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics.

- Sacco, J. 2012. Journalism. New York: Metropolitan Books.

- Scherr, R. 2013. “Shaking Hands with Other People’s Pain: Joe Sacco’s Palestine.” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 46 (1): 19–36, March. doi:10.1353/mos.2013.0004.

- Tomsky, T. 2011. “From Sarajevo to 9/11: Travelling Memory and the Trauma Economy.” Parallax 17 (4): 49–60. doi:10.1080/13534645.2011.605578.

- Wilson, J., and J. Jacot 2013. “Fieldwork and Graphic Narratives.” The Geographical Review 103 (2): 143–152. April. doi:10.1111/gere.12003.

- Wolf, W. 2002. “Das Problem der Narrativität in Literatur, bildender Kunst und Musik: Ein Beitrag zu einer intermedialen Erzähltheorie.” In Erzähltheorie transgenerisch, intermedial, interdisziplinär, edited by V. Nünning, and A. Nünning, 23–104. Trier, Germany: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.