ABSTRACT

Visual narratives, such as graphic novels and comic books, are powerful forms of literature that use verbal and pictorial modes, in intersemiotic complementarity, making them an effective tool to tackle social issues, namely to explore hidden or sensitive topics in a thought-provoking, entertaining, and inspiring way. This is the case in the last graphic novel published by a young Portuguese writer and illustrator for children and young adults, Joana Estrela, the recipient of numerous prestigious awards. In this study, then, we intend to focus on Raquel, the protagonist in Pardalita, who takes her future into her hands and ventures to navigate the waters of self-discovery, crossing prejudice and challenging gender role stereotypes. Through her theatre group, she enters a third space that promotes inclusivity and empowers individuals regardless of gender. By analysing the multimodality that characterises this book, we come to realise the synergistic and transformative potential that visual narratives hold.

Introduction

The concept of identity is highly polymorphic, and its meaning is negotiated and co-constructed through social interaction. As soon as a woman learns she is pregnant with a boy or a girl, expectations within the gender binary are set: the world outside seems to be ready to welcome the newborn with prenatal biases. S/he will be associated with pink or blue, an environment of dolls and fairy tales or balls and cars, and activities such as ballet or football, among other gender-stereotyped beliefs. This is why Butler (Citation1998) argues that the concept of gender is not innate but instead prescribed by society, learnt and acted out, that is, performed: ‘Gender is performative insofar as it is the effect of a regulatory regime of gender differences in which genders are divided and hierarchized under constraint’ (ibidem, Butler Citation2013, 22). Perry et al. (Citation2019, 289) also highlight the idea of adaptability to a certain social category, when they claim it to be ‘a set of cognitions encompassing a person’s appraisals of compatibility with, and motivation to fit in with, a gender collective.’ In fact, rather than fixed, identity formation is an ever-changing process that is negotiated or, following the tropes in the graphic novel that we will analyse, it is navigated, and so are two of its components: the above-mentioned gender category and sexual identity, which, although intimately intertwined, are separate constructs. If, as seen, gender identity stems from our internalisation of norms and our external reaction to this labelling of ourselves and others as a male or female, sexual identity is related to ‘the expression of behaviors and thoughts that have erotic meaning’ (Page Citation2004, 14). On Andler’s usage (Andler Citation2021, 263), it is ‘a matter of the beliefs of other social agents about the individual’s sexual orientation’. Even if, on one hand, gender and sexual identity are social constructs, on the other hand, one’s sexual orientation is, just like one’s sex, defined biologically, according to some researchers (e.g. Bailey et al. Citation2016; Barron Citation2019; Cook Citation2021). Following the same line of thought, Balthazart (Citation2016, 8) postulates that

Human sexual orientation and in particular its less common form homosexuality, is thus not mainly the result of postnatal education, but is, to a large extent, determined before birth by multiple biological mechanisms that leave little to no space for personal choice or effects of social interactions.

In light of the previous discussion, and bearing in mind that, according to Baams & Kaufman, ‘[s]exuality and gender are relevant parts of adolescents’ lives, and related to their health and wellbeing’ (Baams and Kaufman Citation2023, 1), it is not surprising to find these topics mirrored in books for young adults. Books depict imaginary worlds and, thus, readers are allowed to fly on the wings of fantasy, to get to know the characters’ utmost emotions and desires, and, consequently, alternative worldviews and subjectivities generating empathy, or to see themselves represented, hence boosting their self-esteem and sense of belonging (Amante, Citation2022).

Graphic novels and comic books are multimodal media that are prone to showcase those emotions and draw an affective response from readers of all ages, namely young adults, as the example we are about to look at specifically addresses. As we will explain further on, these narratives combine text and visual elements, which allow readers to go beyond words to interpret the subtleties of non-verbal communication. The characters’ looks, such as their hairstyles, choice of clothing, and attitudes, for instance, also convey aspects of their cultural backgrounds, social contexts, and personalities. Graphic novels and comics provide this platform for readers to witness the emotions and experiences of different, diverse characters, and their stories, some of which may be outside of the readers’ familiar scope. Thus, they can serve as a pedagogical tool, challenging heteronormative assumptions while reframing mindsets and attitudes towards unknown realities, and fostering a more inclusive and empathetic understanding of the world. As Malins & Whitty point out (Malins and Whitty Citation2022, 120), ‘books such as these [namely Pardalita, by Joana Estrela] can act as mirrors, windows or doors (…) to expand representation and disrupt identity hierarchies, power relations, and binaries including male/female or heterosexual/homosexual.’

In light of the foregoing backdrop, this study has two objectives. First, it aims to analyse a graphic novel by a Portuguese young author and illustrator that succeeds in her mission of engaging her (young) audience in the visual and verbal dimensions of her work. Second, it attempts to defy stereotypes regarding gender roles, breaking down existing gender distinctions in regard to masculinity and femininity.

For that purpose, we will start by providing a glimpse of who Joana Estrela is and, afterwards, frame her narrative within the broader context of graphic novels/comic books. Subsequently, we will focus on Pardalita itself and we conclude by summarising the key ideas and the overall contribution of the book to the genre.

Joana Estrela, a young new voice

Born in 1990 in Penafiel, Portugal, Joana Estrela studied Communication Design at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Porto, in Portugal. She defines herself as an illustrator and author, thus creatively questioning whether she is an ‘illustrauthor’ or an ‘authorstrator’ (Estrela, Citation2017a). Her first book is a comic book in English and it dates back to 2014. It is entitled Propaganda and it tells the story of her experience, between 2012 and 2013, volunteering with the Gay League in Lithuania, a country where political authorities tried to convince the population that homosexuality is a plague spread by Western countries (Estrela, Citation2014). Later, in 2016, Mana [Little Sis] followed, and it was the winner of the 1st Serpa International Award for Picturebooks (Estrela, Citation2016). In the same year, it was also the recipient of the Best Picture Book Illustration by a Portuguese Author Award (Amadora BD – International Comics Festival in Amadora). Some other works by the same artist are Rainha do Norte [the Northern Queen] (Estrela, Citation2017b), Os Tigres na Parede [Tigers on the Wall] (Estrela, Citation2018), Aqui é um Bom Lugar [Here’s a Good Place] (Estrela, Citation2019) and, among others, Menino, Menina (Estrela, Citation2020), which was adapted and translated into English by the award-winning transgender poet Jay Hulme and titled My Own Way (Estrela and Hulme, Citation2020). Her latest book, the one we will focus on, is Pardalita (2021), a graphic novel in black and white for adolescents and a bit older target, according to its copyright page. As we will see, and as argued by Karen Scott (Citation2023), in a comment published on the Planeta Tangerina website:

Told through traditional graphic novel style panels supplemented with prose and poetry, this hybrid book explores all the conflicting feelings surrounding first love, high school, friendships, family, and change. It takes a realistic look at the confusion teens can feel as they navigate their sexual identities and their own place in their world.

This idea about the discovery of one’s identity was also emphasised and given due weight by the Catalan Booksellers’ Guild, when earlier this year, in May, Pardaleta, the Catalan edition translated by Àlex Tarradellas and published by Meraki, won the Llibreter Prize, in the ‘Best Children’s and YA Literature Book – Other Literatures’ category (de Llibreters de Catalunya Citation2023).

Before embarking on Raquel’s quest, that is, the protagonist’s journey for self-discovery, let us take a brief look at the importance of graphic novels and comic books for the purpose of captivating, entertaining and educating these readers while conveying a meaningful message. Having decided to study comics at LUCA School of Arts, in Brussels, in 2022 (Tangerina Citation2023), Joana Estrela has certainly expanded her knowledge and skills in this field, which has attracted her since she was a young girl.

The importance of graphic novels and comic books

A graphic novel is a visual novel composed of comic-strip panels. More specifically, ‘graphic’ denotes its use of cartoon drawings, and ‘novel’ describes its depiction of fictional or nonfictional stories. The term was introduced in the late 1970s to define a longer and more novel-like version of comics … (Kwon, Citation2020, p. 33)

Although graphic novels and comic books are far from being exclusively addressed to children and young adults, rather being a medium that has firmly established itself as a powerful and versatile art form that is capable of engaging readers of all ages, we are particularly focusing on young audiences because of the book under analysis. The art form of graphic novels, defined above, and comic books, provides children and young adults with the opportunity to experience the aesthetic and affective dimension of pictures and go beyond literal responses. The lines, shapes, shades, tones, colours and angles of the sequential drawings complement the verbal message and give the readers the idea that they are closer to other visual media with which they interact daily, whether it be TV cartoons, films or even video games.

In fact, the combination of the written and the pictorial text opens up more perspectives, and more familiar ones, than just one medium alone and enables the development of a deeper understanding of the content being conveyed. If we take comic books as an example, we notice that, with their multiple panels, they invite the readers to complete meaning by filling in the gaps with prior knowledge, as well as their own beliefs and attitudes. As a result, comic books represent a great pedagogical tool, because students can infer hidden meanings and develop their creativity, but they also may contain subliminal messages that might be used to influence others, such as in political propaganda, as we find in Estrela’s first book, even if politicians and political scientists do not always recognise its value: ‘Yet most political scientists have not given serious consideration to comics even though in recent decades, comic strips, comic books, and graphic novels have been making noteworthy contributions to the political discourse’ (Duncan Citation2021, 282). This type of books is still often underestimated, but it provides a lot more details to cue the viewer/reader and facilitate the interpretation of difficult, complex or abstract meanings.

Being a multimodal medium, it juxtaposes iconographic imagery and the written word, allowing for irony or any other humorous effects to be identified, and it can also be used for supporting causes or advancing ideologies. It is not just the expressions of the characters that give the readers hints about their thoughts, behaviours and actions; it goes beyond the presence of kinaesthetic and proxemic non-verbal signs to bring the aural aspects to the fore through the use of different speech and thought bubbles, captions, font sizes and font types. The paralinguistic component is made visible, and we can detect hesitation and intonation in a character’s voice or almost hear the words that are graphically amplified or whispered. Besides this, visual stimuli attract readers and retain their attention and motivation, turning reading for pleasure into a purposeful social activity, rather than just one that belongs to formal instruction.

Much more could be added about the importance of graphic novels and comic books, but because all the features above can be found in the book we are about to discuss, let us conclude this section by summarising some of the benefits according to Silva (Citation2018, 525), who, in turn, quoting Giroux, explains that ‘comic books [and graphic novels] are considered not only as entertainment products, but also as an artifact of media culture, lying at “the crossroads between entertainment, defense of certain political and social ideas, pleasure and consumption” (Giroux, Citation1995: 60)’.

Pardalita, an evocative, dialogic and powerful counter-narrative that defies expectations and disrupts imposed norms

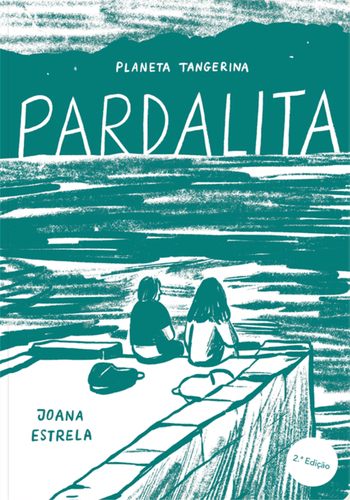

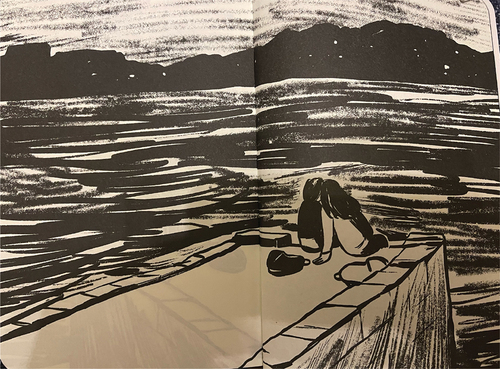

Before diving into the first few pages, the cover of Pardalita deserves special mention (cf. )Footnote1: using green that might suggestively symbolise hope, the author places her two main characters in a simple setting, which we will find again upon the closing of the graphic novel, in pages organised contiguously and in a continuum of six illustrations that appear to repeat themselves or to change only slightly to result in a dramatic effect of suspense. Actually, on the cover, we find the homodiegetic narrator, Raquel, at the moment when she is asked, at the end of the narrative, if she would cross the Tejo River to meet Pardalita, the protagonist, on the other side. We implicitly know that she would traverse it, as on the two last contiguous pages we witness Pardalita and Raquel kissing by the river. The river represents the flow of Raquel’s emotions and her journey of self-discovery. Swimming to the other side implies crossing the space that divides and connects the souls of the two young female lovers and, thus, it means that, by entering an in-between space, or a third space according to Bhabha (Citation1994), she is empowering herself. The river moves from the background to the foreground symbolising the waters that need to be navigated.

The trope of the water is a recurring one: whether discussing the film Titanic and the realisation that the utterance ‘women and children first’ is sexist, to the illustration shown in contiguous pages where we read that high school is a fish tank, also the reference to the Greek myth relating to Leander who swims every night across the Hellespont to spend some time with Hero, his lover, or even, among other instances, the explicit mention to the Greek island of Lesbos. Interestingly enough, when choosing an animal for the girls to identify with, Luísa, Raquel’s best friend since she was four, describes herself as a dolphin, whereas Raquel sees herself as a squid (cf. ). Dolphins are popularly regarded as social aquatic mammals that interact and move in groups, whereas squids, with their tentacles, portray fluidity and freedom, adaptability, dexterity and manoeuverability; thereby, the animal allusions reflect the characters’ personality traits. Pardalita [translated as little hen sparrow], whose real name is unknown till the end of the narrative, is also a free spirit who is constantly chirping cheerfully around Raquel, embraces spontaneity and is the first to climb a tree, rejects conformity, leading the narrator to confess: ‘Pardalita, eu não te percebo./És um verbo irregular. És de decorar’ [Pardalita, I don’t understand you. You are an irregular verb. You are meant to be memorised] (Estrela Citation2022, 178–179).Footnote2

The book opens up with Raquel’s letter to Pardalita, an introductory letter that is not to be sent, but serves the purpose of setting the scene and revealing the way and reason why the protagonist is named that way. We learn that Raquel had been suspended because she has a short fuse and madly yelled at a non-teaching assistant who could not mind her own business, and that Pardalita was named after her scatterbrain attitude when she was passing by Raquel, jumping and gliding like a bird. Pardalita absolutely swept Raquel away from the first moment she had seen her, and we are made aware of it, as we are told: ‘Escrevi o teu nome na mesa. Nem me apercebi, estava distraída, foi a mão que desenhou as letras’ [I wrote your name on the table. I didn’t even realise it, I was distracted, it was my hand that drew the letters] (Estrela Citation2022, 1).

However, things are not easy for Raquel, who has to learn how to adapt herself to be free, just like a squid. She seems to have more than one heart, once again similarly to this marine animal, and even if she loves Pardalita at first sight, she dates Miguel (Estrela Citation2022, 25), who is mockingly addressed by Luísa and Fred, another friend, as ‘O Bailarino’ [The ballet dancer] (ibidem). Although Miguel does not know it, he is the kind of person that would not mind in case he found out about it, according to the narrator. The relationship does not last (Estrela Citation2022, 74), which does not come as a surprise because Raquel feels some kind of depersonalisation disorder, that is, she feels she is observing herself from outside her body, trying to find evidence that everything is ok, but she pretends every single moment when she is with him (Estrela Citation2022, 44). He is alien to her and she feels the urge to ignore him and his text messages (Estrela Citation2022, 60; p. 64). Notwithstanding her lack of interest, she feels hurt when it happens, maybe because she does not want to admit that it is the result of her actions. Losing him means she cannot be saved from confronting her lesbianism, and she questions herself and her feelings in a kind of poem entitled ‘E se for?’ [What if I am?] (Estrela Citation2022, 79). The poem draws one’s attention to the importance of belonging because she needs to discover others who share the same condition, the same letter from a set of letters, as she puts it to refer to the LGBTQI+ acronym. Perhaps there is no need for her to deny it, perhaps she might be bisexual, if we take Luísa’s reading of Raquel’s index and ring fingers, which are exactly the same length (Estrela Citation2022, 138). As Breedlove (Citation2017) puts it, there are some well-documented examples that refuse binary conceptions of human sexual orientations and attest to the finger anatomy – in her words, digit ratios – caused by the presence or the lack of prenatal exposure to testosterone. This would explain Raquel’s difficulties in expressing her identity, always feeling the truth lingers in murky waters, in between a third space of here and there, now and before, you and me, male and female, homosexual and heterosexual, pretending and being: ‘O oposto da verdade é a mentira?/Ou há alguma coisa que fica no meio,/escondida entre as duas?’ [Is the opposite of the truth a lie?/Or is there something that lies in between,/hidden between the two?] (Estrela Citation2022, 141).

Raquel is hybrid, she is both, everything, whole, but she does not know it. She is influenced by her mother, who does not fit conventional feminine standards: Raquel’s mother played football as a girl (Estrela Citation2022, 34), she had been the one to impatiently rush the relationship with Raquel’s father (Estrela Citation2022, 11), she complained about the world and called for changes to be made to the extent of being active online, adopting animals and even organising parades for human rights. She is what may be called both a slacktivist and a cyberactivist (Amante, Freitas, and Silva Citation2023). Raquel’s father is the opposite: he’s the type of person that cannot take decisions (e.g. when to leave parties even if it is too late for his child to be awake). He lets himself be annihilated, as the Monstera Deliciosa plant metaphorically represents: it was the first of many other plants to be taken to his apartment, it stretched and grew, increasingly occupying the living room. Just like the Monstera, the woman who decorates his house with plants progressively dominated his life, by leaving a coat, then a pair of slippers, some milk branded differently from the usual one, and a book … until Raquel finally met her (Estrela Citation2022, 39).

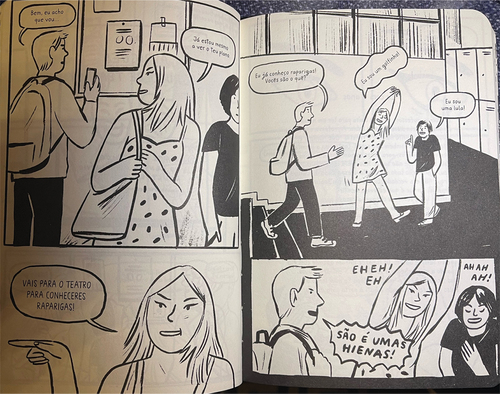

The theatre group was Raquel’s catharsis, as we notice in . It enlightened her, releasing negative emotions and serving a purgative effect. The dancing and all the drama exercises made the theatre a venue for a participatory, multi-dimensional experience. It was the opportunity for her emotions to be elicited and released. She no longer needed to live a mimicry of life, she was entitled to live a real life, the one that was meant to be, according to the lines on her hand: Luísa takes Raquel to see a witch, who reads her palm and sees that someone whose name starts with the letter P would be connected to her, as seen in (Estrela Citation2022, 56–57).

Just like Pardalita who shakes Raquel’s life, the graphic novel itself also defies all conventions, in several different ways. Quoting Lopes (Citation2023, 310), it does so ‘pelo arrojo narrativo e formal, pela abordagem temática e pela própria agência emancipatória de Raquel [through its narrative and formal boldness, its thematic approach and Raquel’s own emancipatory agency].’ The graphic novel Pardalita crosses the line between pop and classical culture. It explicitly references Greek plays and settings, as mentioned above, but it also alludes to popular songs, whether from the rock band The Rolling Stones or from the Portuguese songwriter and singer António Variações, known for his eccentricity, controversial behaviour and for his fusion of genres. Lopes elaborates on the book’s hybridity and multimodality further:

The use of other media, reflected in references to mobile phone messages, the Internet, cinema, music and painting, places Pardalita in the context of contemporary youth literature, since this work ‘resorts not only to literary texts, but also to lyrics, films or elements of popular and media culture’, incorporating ‘elements of poetry, theatre and even genres considered non-literary or paraliterary by tradition’ (Lopes Citation2023, 313, my translation)Footnote3

Estrela mixes diaristic and epistolary writing with poetry, text messages and colloquial speech, acts, lists, quotes, manifestos, lyrics and many other intertextual palimpsests, paintings, drawings, shapes, lines, interjections, unintelligible sounds, and silences to be filled in, interpreted, opening opportunities for her graphic novel to be considered ‘a heuristic tool: a mental technology that facilitates understanding of a text by means of an affective hermeneutics – a set way of gaining knowledge through feeling’, as Anna Wilson puts it in her analysis of fanfiction (Wilson Citation2016, paragraph 1.4). As seen in , the pictorial component, in black and white, is prioritised and shown in comic style or in contiguous illustrated full pages, and has a life of its own, augmenting the verbal component. The use of black-and-white illustrations, dynamic strokes, and intricate shapes is itself a semiotic choice that intends to bring a sense of movement and vitality to each page, while also lending an aura of universality to the graphic novel. In fact, the monochromatic imagery is meant for readers not to lose sight of this quest and the fact that the narrative is not linear also provides us insights into Raquel’s personality, emotions and motivations, growth and self-discovery.

Conclusion – or the long-stand applause

In Portugal, Joana Estrela has been taking the first steps to give a voice to all types of women in books for children and young adults, challenging conventional roles and stereotypical representations associated with genders. We are shown female characters who, like Luísa, dress in very short dresses and like to be ‘hot’ in her words, gossip, cook pink food, and are true confidants; others who, like Raquel’s mother and Pardalita, have empowered themselves, struggling against a status quo of hegemonic masculinity and tired clichés, and who are strong, independent and not afraid of speaking up their minds, behaving like a rainbow; still those who are in between, in a third space, and similarly to Raquel, are rational and pragmatic, full of questions, but open enough to depart on a quest to discover their true selves. It is interesting to notice that Raquel envies Pardalita’s freedom: ‘Sinto-me mal quando te vejo. Se calhar tenho inveja de ti [I feel bad when I see you. Maybe I’m jealous of you]’ (Estrela, Citation2022, p. 19), and so she looks up to her as a source of inspiration.

This book may also be a source of inspiration for young people to read about a story that they can relate to, or, even better, for readers of all ages to understand themselves or others around them. As noted on the copyright page, books published under the Dois Passos e Um Salto imprint are intended for adolescents and other older readers, and we are further informed that ‘Não há uma idade certa para ser leitor desta coleção [There is no right age to be a reader of this imprint].’ As Abate, Grice and Stamper (Citation2018, 1) point out, when referring to the power of visual narratives to evoke a sense of self and belonging:

Comics have been an important locus of queer female identity, community, and politics for generations. Whether taking the form of newspaper strips, comic books, or graphic novels and memoirs, the medium has a long history of featuring female same-sex attraction, relationships, and identity.

The same idea is shared by Pantaleo (Citation2017), who claims that visual narratives imply a unique combination of image and writing, enabling a seamless flow of emotions and motion/action.

The storyteller and illustrator Joana Estrela has been gaining global visibility, heralded for her ability to tackle significant and complex societal issues with creativity and sensitivity. As seen, through Pardalita, Estrela encourages her readers to embrace their uniqueness and individuality, free from societal pressures. Thus, this graphic novel has a remarkable potential to open up conversations about (self-)acceptance, empathy and understanding, being a great pedagogical tool to question and explore societal norms, while encouraging kindness and respect to be upheld at all times, in all circumstances.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The publishing house and the author have granted us permission to reproduce the pictures in this article.

2. Pardalita is not paginated, but the page number is added for easier reference, considering the letter as the first page.

3. A convocação de outros media, plasmada nas referências a mensagens de telemóvel, à Internet, ao cinema, passando pela música e pela pintura, posiciona Pardalita no âmbito da literatura juvenil contemporânea, uma vez que também nesta obra é possível encontrar ‘o recurso não apenas a textos literários, mas a letras de músicas, filmes ou elementos da cultura popular e mediática’, incorporando ‘elementos da poesia, do teatro e mesmo de géneros considerados não-literários ou paraliterários pela tradição’ (Ramos E Navas (Citation2016) 19) (Lopes Citation2023, 313).

References

- Abate, M., K. Grice, and C. Stamper. 2018. “Introduction: “Suffering Sappho!”: Lesbian Content and Queer Female Characters in Comics.” Journal of Lesbian Studies 22 (4): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2018.1449500.

- Amante, S. 2022. “Chimamanda Adichie, Mia Couto e o combate às expectativas de género [Chimamanda Adichie, Mia Couto and their struggle against gender expectations].” Revista Estudos Feministas 30 (1): e75873. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9584-2022v30n175873.

- Amante, S., A. Freitas, and A. I. Silva. 2023. “Representation of the American #METOO Movement in Portuguese Online Media.” Revista Conhecimento Online 15 (2): 211–234. https://doi.org/10.25112/rco.v2.3330.

- Andler, M. 2021. “The Sexual Orientation/Identity Distinction.” Hypatia 36 (2): 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/hyp.2021.13.

- Baams, L., and T. Kaufman. 2023. “Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity/Expression in Adolescent Research: Two Decades in Review.” The Journal of Sex Research 60 (7): 1004–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2023.2219245.

- Bailey, J., P. Vasey, L. Diamond, S. Breedlove, E. Vilain, and M. Epprecht. 2016. “Sexual orientation, controversy, and science.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 17 (2): 45–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100616637616.

- Balthazart, J. 2016. “Sex Differences in Partner Preference in Humans and Animals.” Philosophical Transactions Royal Society B 371 (1688): 20150118. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0118.

- Barron, A. 2019. “Sexuality is Complex.” New Scientist 243 (3243): 23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0262-4079(19)31528-3.

- Bhabha, H. 1994. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge.

- Breedlove, S. 2017. “Prenatal Influences on Human Sexual Orientation: Expectations versus Data.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 46 (6): 1583–1592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0904-2.

- Butler, J. 1998. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology Andfeminist Theory.” In Writing on the Body: Female Embodiment and Feminist Theory, edited by K. Conboy, N. Medina, and S. Stanbury, 401–417. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Butler, J. 2013. “Critically Queer.” In The Routledge Queer Studies Reader, edited by D. E. Hall and A. Jagose, 18–31. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cook, C. 2021. “The Causes of Human Sexual Orientation.” Theology & Sexuality 27 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13558358.2020.1818541.

- de Llibreters de Catalunya, G. 2023. XXIV PREMI LLIBRETER. https://gremidellibreters.cat/xxi-premi-llibreter/.

- Duncan, R. 2021. “Persuasive Comics.” In What Political Science Can Learn from the Humanities: Blurring Genres, edited by R. A. W. Rhodes and S. Hodgett, 259–286. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Estrela, J. 2014. Propaganda. Porto: Plana.

- Estrela, J. 2016. Mana. Carcavelos: Planeta Tangerina.

- Estrela, J. 2017a. Joana Estrela: About me. https://joanaestrela.com/about/.

- Estrela, J. 2017b. A Rainha do Norte. Carcavelos: Planeta Tangerina.

- Estrela, J. 2018. Os Tigres na Parede. Lisboa: Zero a Oito.

- Estrela, J. 2019. Aqui é um Bom Lugar. Carcavelos: Planeta Tangerina.

- Estrela, J. 2020. Menino, Menina. Carcavelos: Planeta Tangerina.

- Estrela, J. 2022. Pardalita. (2021, 1st ed.). 2nd ed. Carcavelos: Planeta Tangerina.

- Estrela, J., and J. Hulme. 2020. My Own Way: Celebrating Gender Freedom for Kids. London: Wide Eyed Editions.

- Giroux, H.1995. A disneyzação da cultura infantil. In Territórios contestados: os currículos e os novos mapas políticos e culturais, edited by T.T. Silva and A.F. Moreira., 49–81. Petrópolis: Vozes.

- Kwon, H. 2020. “Graphic Novels: Exploring Visual Culture and Multimodal Literacy in Preservice Art Teacher Education.” Art Education 73 (2): 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2019.1695479.

- Lopes, M. J. 2023. “Entre o passado e a contemporaneidade: o mito de Hero e Leandro em Pardalita [Between the past and contemporaneity: the myth of Hero and Leandros in Pardalita].” Ágora Estudos Clássicos em Debate 25:301–322. https://doi.org/10.34624/agora.v25i0.31358.

- Malins, P., and P. Whitty. 2022. “Families’ Comfort with LGBTQ2s+ Picturebooks: Embracing Children’s Critical Knowledges.” Waikato Journal of Education 27 (1): 119–132. https://doi.org/10.15663/wje.v26i1.912.

- Page, A. 2004. Behind the Blue Line: Investigating Police Officers’ Attitudes Toward Women and Rape (PhD dissertation). University of Tennessee. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/6369.

- Pantaleo, S. 2017. “The Semantic and Syntactic Qualities of Paneling in Students’ Graphic Narratives.” Visual Communication 18 (1): 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357217740393.

- Perry, D., R. Pauletti, and P. Cooper. 2019. “Gender Identity in Childhood: A Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Behavioral Development 43 (4): 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025418811129.

- Ramos, A. M., and D. Navas. 2016.“Literatura juvenil dos dois lados do Atlântico.” Porto: Tropelias & Companhia.

- Scott, K. 2023. “Pardalita: o que se diz.” https://www.planetatangerina.com/pt-pt/loja/pardalita/.

- Silva, M. 2018. “Gender Relations, Comic Books and Children’s Cultures: Between Stereotypes and Reinventions.” Policy Futures in Education 16 (5): 524–538. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210317724642.

- Tangerina, P. 2023. “Autores: Joana Estrela.” https://www.planetatangerina.com/pt-pt/sobre/joana-estrela/.

- Wilson, A. 2016. “The Role of Affect in Fan Fiction.” Transformative Works and Cultures 21. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2016.0684.