ABSTRACT

In 1944, U. S. Camera Company, the force behind one of the largest circulation photography magazines, launched Camera Comics for children. At the heart of every ten-cent issue was Kid Click, a teenage “shutterbug” whose camera helped him overcome bullies at summer camp, to uncover Nazi spy rings, and to bring armed robbers to justice. The character provided a neat segue to the rotogravure illustrated and textual pages of Camera Comics that offered photographic guidance for children, including tips for building camera gadgets at home and winning school competitions. Photographs by “typical American boys” – real-life Kid Clicks – abutted camera advertisements aimed at the same. Camera Comics imagined and addressed US child photographers via a distinctive set of gendered and nationalistic narratives, offering an illuminating comic-themed case study in a much wider and longer story of how cultural expectations of cameras and children have been ideologically constructed to intersect. This article offers a close reading of the extant nine issues of the comic and a comparison with parallel issues of U. S. Camera magazine, along with other primary sources that aligned children with photography in the period. These are contextualised with secondary literature on comics, photographic history, and childhood studies. Ultimately, the article argues that Camera Comics offers a highly productive space for surveying cultural expectations made of children in mid-century USA, and especially the conflicting moral attributes applied to different media forms and tools directed at children as cultural consumers and producers.

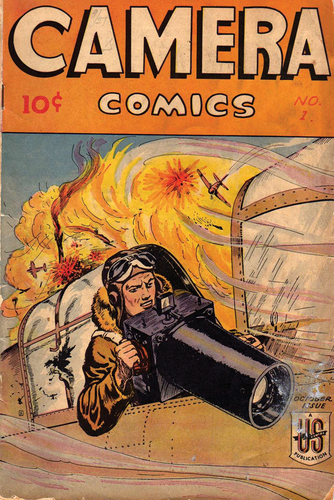

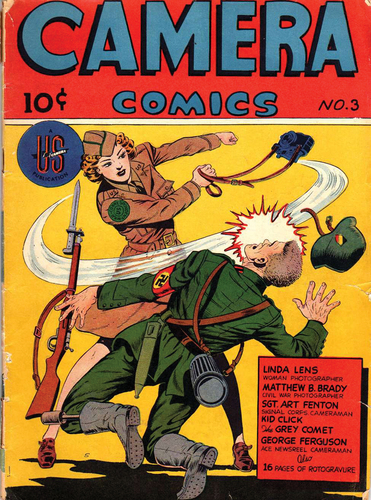

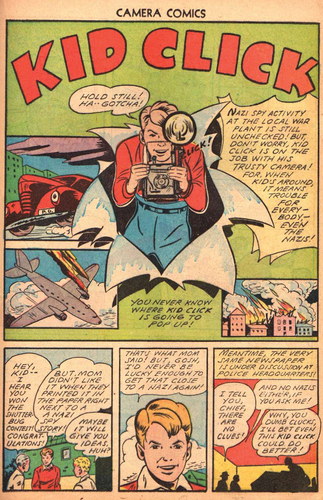

In 1944, the U. S. Camera Company, the force behind one of the largest circulation photography magazines, launched Camera Comics, aimed at children. Over two years, the comic combined adventurous illustrated stories of fictional hero photographers, from ‘Bob Scott: Crash Photographer’ to ‘Linda Lens: Ace Woman Photographer’ whose photojournalism covered international revolutions and violent domestic crime. In a war context, the military camera was at the centre of stories about aerial bombardment, while the detective camera vanquished the cunning wiles of crudely caricatured US enemies. At the heart of every ten-cent issue was Kid Click, a teenage ‘shutterbug’ whose camera helped him overcome bullies at summer camp, to uncover Nazi spy rings, and to bring armed robbers to justice. The character provided a neat segue to the rotogravure illustrated and textual pages of Camera Comics that offered photographic guidance for children, including tips for building camera gadgets at home and winning school competitions. Photographs by ‘typical American boys’ – real-life Kid Clicks – abutted camera advertisements aimed at the same.

As part of a mid-century boom in camera ownership and a concomitant growth in publications designed to support these new photographic publics, Camera Comics can be read as one of several manifestations of educational literature adopting a child-friendly comic visual form in the period. Yet, as this article will show, Camera Comics was not straightforward in its educational messages and certainly not in its moral guidance. Its contents include violent scenes and racist depictions; Kid Click uses his fists in the pursuit of justice, and his friend Skinny uses his camera to get ‘fresh’ with attractive girls. Articles between stories showcase the pictorial achievements of young competition winners and advise readers on how to photograph their model trains. Kid Click, by contrast, photographs armed hold-ups, is threatened with acid baths and at gunpoint, and is kidnapped and violently tortured.

This article considers Camera Comics in the wider context of how photography was promoted in mid-century USA as morally beneficial for children at the same time as comics were characterised as morally corrupting. From the start of the twentieth century, well-financed advertising campaigns by major US manufacturers, especially Kodak, have supported the sales of cameras marketed at children, while youth organisations, such as the Boy Scouts of America, promoted photographic seeing as a component of modern citizenship and productive leisure in the interwar period. By the Second World War, the child’s camera took on new ideological messages embodied in the fictional characters and comic retellings of photographic history in Camera Comics.

As this article demonstrates, Camera Comics imagined and addressed US child photographers via a distinctive set of gendered and nationalistic narratives, offering an illuminating comic-themed case study in a much wider and longer history of how cultural expectations of cameras and children have been ideologically constructed to intersect.Footnote1 To explore this little-examined phemonenon, I offer a close reading of the extant nine issues of the comic, and a comparison with parallel issues of U. S. Camera magazine by the same publisher, along with other primary sources that aligned children with photography in the period.Footnote2 These are contextualised in relation to critical, theoretical and methodological literature on US comic history, photographic history, and childhood studies. Ultimately, I argue that the previously unanalysed Camera Comics offers a highly productive space for surveying cultural expectations made of children in mid-century USA, and especially the conflicting moral attributes applied to different media forms and tools directed at children as cultural consumers and producers.

A short history of photography by American children

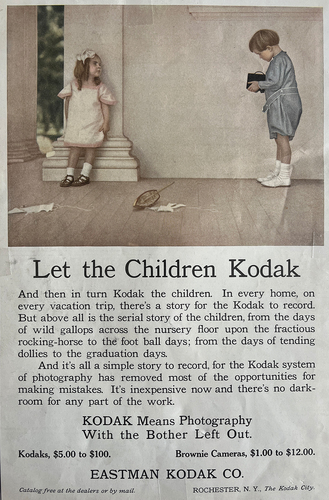

Photographic historian John R. Stilgoe observed in Citation2014 that the ‘long relationship between American children and photography begs to be written’ (101). While a full history remains overdue, valuable studies have provided reflection on some key moments in the formation of children as photographers, mostly in relation to the first promotion of cameras to children by the American manufacturer Kodak from 1900. Nancy Martha West (Citation2000), for example, has explored how very young children were targeted by Kodak as consumers and users of the simple-to-operate and push-button Brownie cameras. Promoted via the fairy figures of the Brownie, as illustrated in Palmer Cox’s popular children’s books, the Kodak Brownie was an early form of character marketing which aligned the enchantment of usually invisible helpful household creatures with photography’s apparently magical visual effects. Children were figured in advertising campaigns in the first decade of the twentieth century as symbolic guarantors of the camera’s simplicity, while the framing of the company’s slogans, such as ‘Let the Children Kodak’, suggested children’s eagerness to participate in photography and parental generosity in enabling them to depict the world on their terms (). Such endeavours attempted to naturalise the connection between children and cameras.

Figure 1. ‘Let the Children Kodak’, Eastman Kodak Company advertisement. The Ladies’ Home Journal, March 1909, p. 86. Author’s own photograph. Collection of Annebella Pollen.

With the coming of more organised youth groups, such as the Boy Scouts of America, from around 1910, cameras became increasingly harnessed to the wider principles of citizenship and nature observation that were promoted for children as social skills. As a form of productive leisure, photography was linked, by manufacturers and youth organisers alike, with the physically and morally improving outdoor activities of camping and sports. In these discourses, the camera was an enhancement of other forms of enjoyment and a form of meaningful engagement in its own right. Naturalists and educators both vouched for its educational and even spiritual merits. ‘The child with a camera habit is no longer an interloper between earth and sky’, claimed the American philosopher, Elbert Hubbard, in a statement adopted by Ansco cameras in its advertising from 1912 (‘The Superb Ansco’, National Sportsman, p. 75). ‘He is never lonesome, wherever he is, because he feels the kinship that exists between himself and all living things.’ () The camera’s value, across these claims, was social, scientific, playful and purposeful, especially for boys. Magazines, including The American Boy, and the scouting periodical, Boy’s Life, ran regular photographic features and camera advertising during the interwar period.

Figure 2. ‘The Superb Ansco’, Ansco Company advertisement. The National Sportsman, 1912, p. 73. Author’s own photograph. Collection of Annebella Pollen.

By the end of the 1930s, US publications produced by camera manufacturers and independent authors equally promoted photography as easy, interesting, and worthwhile as a hobby, and as training for a career. For the rural youngster, its usefulness might include applications in ‘vocational agriculture’, where photographs could be used for to create records of livestock and crop cultivation; it could offer a parallel to hunting, as ‘shooting with a camera is a lot like shooting with a gun’ (Eastman Kodak Citation1939, 17). For urban boys, as outlined in The Boys’ Book of Photography, there were many thrilling potential photographic jobs to grow into. In police departments, for example, ‘roving cameramen photograph the scenes of murders and fatal accidents, to aid detectives in solving crimes’, as the author of the 1941 guide put it. ‘Fire departments often have special cameramen to record the exciting work of battling flames.’ Alternatively: ‘If you like excitement and variety, and are fast on the trigger of your camera’, a newspaper photographer’s role might appeal. ‘Shooting scenes of excitement – mobs, riots, murders, fires, the arrival of famous personages – is all in the day’s work for them. They have to be able to shoot fast and keep cool’ (Teale Citation1941, 240).

New photographic audiences, new photographic publications

The promotion of an expanding photographic culture of possibility for children mapped onto contemporary expectations about US children’s interests and capacities, but it was also a product of nationally expanding cultures of photography more broadly at mid-century. Teale’s text boasted that, one hundred years after photography’s invention, 25 million cameras ‘were owned by Americans alone’ (Citation1941, 7). Beaumont Newhall, the first photographic curator at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, made a similar assessment of the state of photography before the Second World War, describing it as ‘the brink of a revolution as staggering as any photography in its hundred years of existence had experienced.’ The revolution was, as historian Raeburn (Citation2006, 95) has argued, principally in the new audiences that photography commanded and the new channels through which it was disseminated. These included print periodicals, which flourished like never before and through which a broader, more democratic culture of amateur photographic engagement was fostered.

One of the most popular of these magazines was U. S. Camera. Founded in 1938 by Tom Maloney, a Manhattan advertising executive, it began as a large-format spiral bound quarterly, but soon moved to a more cheaply produced monthly. It kept its large 10 × 15-inch format, all the better to pack a visual punch with its eclectic range of photo essays and news reportage, pin-ups and pictures of kittens and babies. The 15-cent, 72-page monochrome magazine carried effusive guidance for amateurs and professional photographers’ portfolios interspersed with abundant advertising from camera manufacturers large and small. As the USA entered the war, U. S. Camera turned its attention to military matters, made manifest not only through dramatic and sometimes explicit war photographs, but also through the framing of more domestic and sentimental subject matter, especially that produced by women at home. A dominant patriotic narrative ran through both editorial and advertising copy. For example, in an April 1944 advertisement for Kalart range finders and flash devices, readers are told: ‘Don’t miss the pictures he’ll treasure most. His own kids maybe. Or members of his family. The people he’s fighting for!’ The accompanying photograph was of three young blonde-haired children. The message conveyed was that while those at home may not be able to ‘send as many pictures as you would like, because film and bulbs have gone to war with him’, photographs could still be made precisely, with specialist kit, to eliminate waste in constrained times (47).

U. S. Camera, at its peak, sold some 300,000 copies per issue and was second only in sales figures to Popular Photography, its rival, which had launched a year before it (Saretzky Citation2004, 26–27). U. S. Camera’s reach was broad and its intended readership wide. In the company’s own promotion in May 1943 (58), it was read by ‘the bright people’, including ‘the professional’, ‘the doctor’, ‘the lawyer’, ‘the army’, ‘the navy’ and ‘the women’. Although children were the fond visual subject of many photographic features, nowhere were they addressed as readers. Maloney, however, a keen entrepreneur, published U. S. Camera magazine alongside annuals of ‘best of’ photographs, commemorative war albums and photographic manuals. In 1944, he began producing photographically-illustrated children’s books for the first time, and he also launched the first issue of Camera Comics.

Camera Comics in comic context

Camera Comics emerged at a time when periodical production was booming in the US, and not just in camera magazines. Even though the country was at war, and paper rationing was in place from 1943, the years between 1936–1954 have been described by Jean-Paul Gabilliet as ‘a commercial golden age for illustrated magazines, at least in terms of the number of units sold’ (Citation2010, 197). Alongside this, reading had seen a sharp rise in popularity since the early 1930s with a ‘meteoric rise’ in book borrowing (Citation2010, 195). In addition, the second half of the 1930s saw ‘the progressive improvement of overall economic conditions’, leading to a growth in disposable income (Gabilliet Citation2010, 17). These shifts in commercial production, shifts in leisure activity and shifts in purchasing power occurred at the same time as a new publishing format and genre emerged: the comic book.

Originally taking the form of republished newspaper comic strips, the cheaply produced, affordable and standalone comic books, containing original content and, crucially, aimed at child readers, took off from the mid-1930s as a distinctive new American cultural product that achieved enormous popularity. While there are scholarly discrepancies in figures, even the more modest of calculations observe major numbers. Carol Tilley, for example, notes that, while in 1939 ‘twenty-three weekly and comic periodicals which continue the adventures of the daily and Sunday funny paper characters could be found on newsstands and in drugstores, by 1945 readers could select from more than one hundred comic book titles. Sales figures for that year indicate that readers purchased almost twenty-five million comics each month, equal to the combined sales of the four best-selling noncomics magazines, including the Reader’s Digest and Ladies Home Journal’ (Tilley Citation2012, 388). Notably, readers were largely children. ‘According to a series of articles appearing in the New York World-Telegram in 1942’, Gabilliet notes, ‘the average age of comic book readers was ten to twelve years old. A survey undertaken in 1944 revealed that between six and eleven years of age, 95% of boys and 91% of girls read comic books, at an average of a dozen per month’ (Citation2010, 198).

Comics were typically printed on cheap paper in four colours, stapled together in thirty-six to sixty-eight pages, containing line-drawn stories in sequential panels with speech bubble dialogue. Advertising, of products aimed at children, and of other periodicals by the same publishers, typically represented around 10% of content. Comics covered a range of territories and styles. Action and adventure stories were popular, especially when accompanied by the superheroes that were an innovation of the form, but there were also many other genres; these spanned love to crime. A distinctive category was the educational non-fiction comic, which achieved some popularity in the early 1940s when public criticism began to emerge in national newspapers about the suitability of comics’ content and style for impressionable child readers.

Literary critic Stanley North, for example, in a widely cited 1940 article in Chicago Daily News entitled ‘A National Disgrace (and a Challenge to American Parents)’ stated:

Virtually every child in America is reading color ‘comic’ magazines - a poisonous mushroom growth of the last two years. Ten million copies of these sex-horror serials are sold every month. One million dollars are taken from the pockets of America’s children in exchange for graphic insanity.

He studied 108 examples and found ‘at least 70%’ to be ‘of a nature no respectable newspaper would think of accepting’. In particular, he noted, ‘the bulk of these lurid publications depend for their appeal upon mayhem, torture and abduction – often with a child as the victim’ (North Citation1940, 56). In response, the publisher of Parents’ Magazine produced a factual comic that they perceived to be more educationally wholesome than comics based on fictional fantasies, supernatural characters and superhuman feats. True Comics, as Gabilliet describes it, ‘contained biographies of Winston Churchill and Simon Bolivar and pages on malaria and the marathon’ (Citation2010, 26). It sold 300,000 copies in ten days, although Gabilliet suspects that most buyers were parents rather than children.

It was into this landscape that Camera Comics emerged. Its 52 pages comprised two-thirds colour comic stories and one-third rotogravure monochrome photography magazine-style content. In the comic category, every issue featured a biography of a photographic pioneer told in comic story format, from Kodak’s founder, George Eastman, to Matthew Brady, ‘America’s First War Photographer’. Fictional comic characters involved men whose identities intersected with photography, such as the Grey Comet, ‘a daring danger-seeking member of the Army Air Force’, whose aerial battles took place in a plane loaded with cameras instead of bombs; George Ferguson, a Newsreel Cameraman; and ‘Jim Lane: Insurance Investigator’. Linda Lens, the sole female lead character, was an advertising photographer who turned her back on fashion to become a war reporter. Each character faced peril, battled threat, fought enemies, and solved crime, often in treacherous conditions, amid arson or bombardment, gunfire or stabbing, bondage or kidnapping, fist fights or car crashes. ( and )

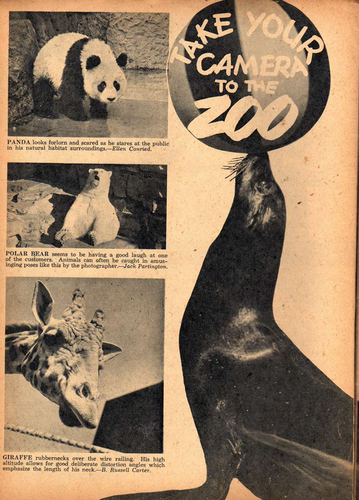

In the rotogravure category, photographically illustrated pages provided technical guidance for camera composition and photographic printing, and inspiration on subjects and styles. Photographic pursuits, from the daring (venomous snake photography) to the domestic (comic caricatures made with kitchen equipment), were covered in features sometimes repurposed from U. S. Camera. () Alongside the drawn stories and the photographic sections, Camera Comics carried advertisements for cameras and film, as well as promotions for other publications, including U. S. Camera, but also Mechanix Illustrated (promoted by Captain Marvel) and Parents’ Magazine comics.

Kid clicks: child photographers in Camera Comics

A key illustrated story in every Camera Comics issue was the blonde teen comic character, Kid Click. ( and ) Sometimes featuring as the sole protagonist, and sometimes appearing in conjunction with his teen sidekick Skinny, Kid was of indeterminate age. He was old enough to be out on his own and to be able to work in junior roles, but young enough to be chastised by his mother and not be taken seriously in a workplace. His attendance at a summer camp in Issue 5 places him at sixteen years old or under. For a child reader of Camera Comics, this character was perhaps the one they were expected to identify with most, as he was not, like other characters, a fighter pilot or a professional detective, although that is not to imply that his life was unremarkable. Over nine spreads, Kid suffered death threats by acid bath and armed assailants; he attacked armed muggers with rocks and fought off bullies with fists. He was tortured and kidnapped; with his camera and his ingenuity, he foiled black market racketeers and Nazi spy rings. He did this with a simple cameras and sometimes without film (the fact that film was rationed in America in the period, and was thus barely available, was used as the premise for stories about undercover trading).

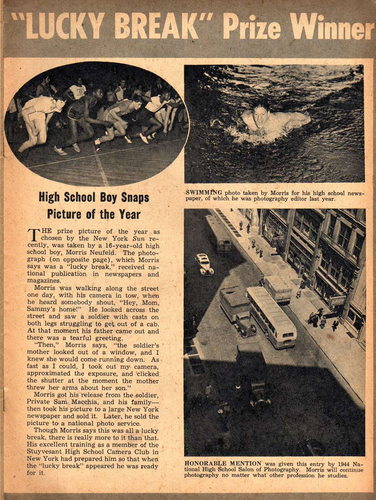

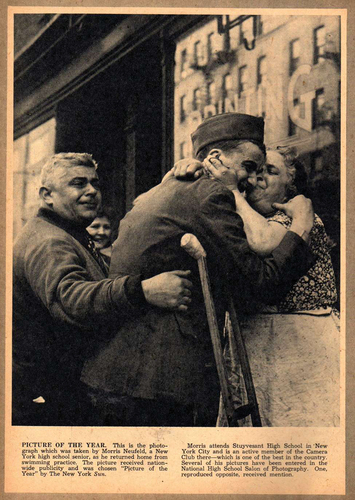

After reading Kid Click’s adventures, the child reader was taken to features on real-life Kid Clicks and ). A two-page feature in Issue 4 (24–25), for example, showcased a ‘Picture of the Year’ photographed by a ‘High School Boy’. Sixteen-year-old Morris Neufeld took a chance photograph of a returning soldier on the street, and it became celebrated in the national press. The article emphasised Neufeld’s role as a member of high school camera club and photography editor of the school magazine. In Issue 6 (24–25), an article entitled ‘Photo Album’ summarised, in its subtitle, ‘Eight year-old Tommy Valentine shows an unusual photographic talent’. Valentine was given a camera by his grandfather and used it to snap days out at the coast and the zoo, and to take photographs of friends and flowers. The narrative is that the technicalities of developing and printing and the need for complex cameras can come later; if a boy of eight can take up the hobby and get his pictures published, ‘he is headed on the right road to a career’. Features on the Kodak High School Photography Competition, with $3000 in prizes, were promoted in Issue 7. There was also a High School prize promoted in the All-American Photo Contest, sponsored by camera manufacturer, Graflex, which boasted $5000 prizes in Issue 8. ‘Kid Photographer’ Evan Richards, who won the Kodak High School Photography Contest, featured in Issue 9. His story became a series of cartoons on Camera Comics’ pages, completing the cycle.

Advertising the idea of photography

Child photographers also appeared in an important additional element of Camera Comics, that is, in its advertising. Full colour Kodak advertisements featured on the comic’s back pages, and sometimes as double-page spreads within, while children as camera users and photography consumers were also depicted in advertisements for other manufacturers and other products. The opening advertisement in Issue 6 (2), for example, was entitled, ‘Hurry Up! You can have this big book of war pictures!’ The illustration was a line drawing of four boys looking at a photographically-illustrated publication with delight. The copy read: ‘It’s jam-packed with thrilling, action-filled photographs of the War! Daring combat lensmen risked their lives to bring you these scenes of the greatest war in history. Every boy in your neighbourhood will want this exciting picture book! Maybe you can be First!’. An advertisement for Mechanix Illustrated in Issue 6 (51), which Captain Marvel says is ‘crammed with exciting new inventions’, featured a rare girl photographer, snapping a burning building. She said, in a speech bubble, ‘These photo kinks are what I like in Mechanix Illustrated! They’re Fun!’.

A core challenge for advertising cameras and associated products in wartime was that US industrial production had been redirected to the war effort and new cameras could not be bought. Film sales were limited by rationing. These conditions affected the wider photographic culture, as demonstrated in the pages of U. S. Camera where, despite scarcity, nearly half of its pages in wartime are given over to advertising. In keeping with the patriotic messaging of the periodical, war was the dominant theme; advertisers who could not sell a product instead promoted their role in the war effort. For example, Universal Camera Corporation, who described themselves as ‘Makers of Precision Photographic and Optical Instruments’, ran full page advertisements about the importance of binoculars on frontline duties; illustrations showed drawn scenes of helmeted soldiers in commando positions, holding guns and walkie talkies and looking through viewfinders. The narrative was written like a war story: ‘Hold it, boys! Those devils are up to something’. The segue was to the promotion of products: ‘Naked eyes might never have caught the suspicious signs. […] Universal is proud of being one of the few specialized manufacturers now engaged in making binoculars for the Army, Navy and Marines, and the United Nations’ (2 May 1943).

A sense of delayed gratification was found across all camera promotions; if you could not buy cameras, you must wait. In a May 1943 advertisement in U. S. Camera by Agfa Ansco (3), for example, a hand sketched a camera on drawing paper. The narrative explained, ‘While working day and night on their war jobs, our engineers just can’t resist the temptation to jot down an idea every now and then for tomorrow’s camera … The Dream Camera.’ The advertisements were designed to keep brands and their imagined promise in customers’ minds until after the war, with products promoted as worth waiting for. The same strategy was at work in Camera Comics, especially in relation to Kodak supplies.

In Issue 2 of Camera Comics, for example, the advertisement for Kodak cameras used comic illustration styles in the same four colours as the comic stories (). It offered continuity with articles about cameras in army service, such as ‘Invasion by Camera: The Reconnaissance Photogs are the Eyes of the War’ (Issue 2, 26), and the precision instruments depicted in articles and on covers (including on the very first issue), as well as the promotion of cheaper equipment that readers might be able to afford. ‘A Brownie Reflex came back from overseas recently, something of a hero’, an advertisement claimed in Issue 2. ‘It had stopped a fragment of shrapnel headed straight for its owner, an American artilleryman. Quite a camera in peacetime, too, the Brownie Reflex.’ The advertisement proceeded to outline its technical merits, but potential consumers were told ‘look for it after the war’ (52). It could not be bought under current conditions.

Figure 10. ‘Kodaks are Fighting’, Eastman Kodak Company advertisement, Camera Comics, issue 2, p. 52. Public domain comic scanned by Comic Books Plus.

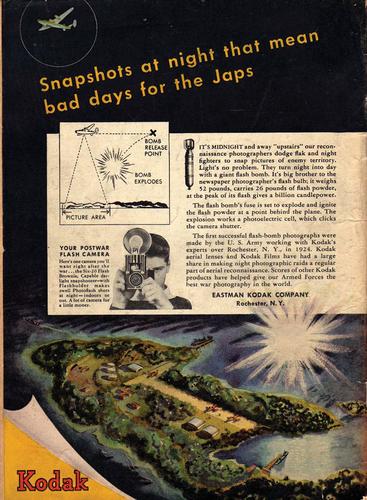

Issue 3 of Camera Comics had a back page advertisement for Kodak film, which began: ‘Picture yourself a fledging fighter pilot […] There’s a gun camera in your plane … ’ It asked readers to imagine themselves in a role they could not inhabit, with technology and tools they could not buy; the task was to keep photography in the minds of dreamers, to create demand for the future. ‘Because of war demands, Kodak Verichrome Film may be hard to get, but as America’s favourite film it is well worth waiting for’ (52). Similarly, in Issue 4, the final page advertisement entitled, ‘Snapshots at night mean bad days for the Japs’, likened Kodak’s indoor flash technology to a US ‘flash bomb’ on enemy territory. () A photograph showed a boy with the flash camera in his hands, while the text read: ‘Your postwar flash camera.’ On the resolution to the comic’s narrative development that was the back page, it offered a culmination of the components of the comic: ‘Kodak products have helped give our Armed Forces the best war photography in the world’ (52).

Figure 11. ‘Snapshots at night that mean bad days for the Japs’, Eastman Kodak Company advertisement, Camera Comics, issue 4, p. 52. Public domain comic scanned by Comic Books Plus.

Photographic historian Rachel Snow has argued that Kodak’s wartime photographic advertising campaigns ‘aimed at building consumer loyalty and a positive corporate image’. They did so not necessarily by advertising products, but by selling the notion that the corporation was ‘an indispensable public institution, allied with the U.S. government in times of war and crisis’. As the leading manufacturer of photographic products and services, Kodak did, indeed, take a lead role in the wartime production of photography and precision optical products for communications, surveys, aerial mapping and engineering. As Snow put it, by ‘educating the public about Kodak’s varied and far-reaching achievements’, advertisements could burnish the company’s reputation and deflect from the fact – which may not be viewed so favourably – that despite restrictions on the domestic sale of cameras and films, business boomed for Kodak in these new directions in the Second World War. Kodak advertising thus served to deflect from their expanding profits towards a more wholesome notion of the company as a public servant (Snow Citation2016, 152).

Kodak has been credited not only with inventing and popularising affordable roll film cameras in the late nineteenth century, but with creating a broader set of meanings and practices that set the template for amateur photography as a culture. It did this through its enormous advertising budgets and its innovative campaigns that sold the idea of photography rather than simply cameras and films (West Citation2000). Selling the idea of photography became pertinent again in wartime conditions when photographic products were in limited supply; Kodak could promote its own brand without having products on sale. As Snow observed, Kodak literally and metaphorically weaponised the camera: ‘the company knew the public would be pulled into the drama of technological development through images of warplanes, fighter pilots, and high-tech camera-guns’ (Snow Citation2016, 159). This was especially the case with its advertising to boys, to whom battle fantasies were widely promoted, including in comics. Boys were explicitly addressed as ‘embryo war photographers’ by Kodak in Camera Comics, Issue 6, 27. Even though boys may never take frontline photographs themselves, positive, patriotic associations with heroic servicemen were attached to products by proxy, and the camera’s peacetime potential was promised ‘after Victory’.

Fantasies and realities: good comics/bad comics

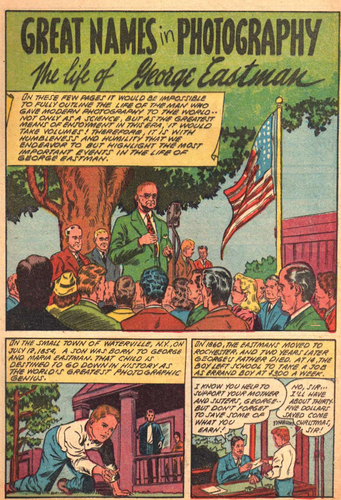

In the brightly coloured dream spaces of camera advertising and comic stories alike, child readers of Camera Comics could imagine what might be possible as child photographers. The reality of what they might be able to capture on the commonly owned amateur box camera, however, without flash and without focus, was rather more limited, even if film could be had: merely eight small black and white prints. Readers who owned only simple equipment were therefore reassured: ‘The box camera, like a revolver in the hand, is always ready to be quickly brought up and shot, much quicker than it takes to tell’ (Issue 6, 23). Cameras for boys were frequently recast as guns, and owners could imagine themselves as detectives and spies, vanquishing enemies and becoming great men. George Eastman, for example, in his Camera Comics life story, was first shown as an infant and then as a 14-year-old errand boy; the narrative promised: ‘That child is destined to go down in history as the world’s greatest photographic genius’ (Issue 2, 9). () In encouraging heroic possibilities, the photographic companies whose advertising supported Camera Comics might secure future sales, and the parent publisher might secure future readers.

Figure 12. ‘Great Names in Photography: The Life of George Eastman’, Camera Comics, issue 2. Public domain comic scanned by Comic Books Plus.

U. S. Camera advertised their magazine in Camera Comics. In 1946, they wrote: ‘If photography’s your hobby – or if it is going to be; or if you’re just interested in looking at good pictures – this is the magazine for you.’ Despite the fact that U. S. Camera did not address children in its content, it stated, in its Camera Comics advertising: ‘U. S. Camera is Big – pages the size of Life – it’s filled with pictures and there’s good reading in it for every member of the family, young or old’ (Issue 8, 51). The covers used to promote the magazine showed a nude young woman, seen from the waist up and from the side, typical of the ‘cheesecake’ pin-ups that were a wartime staple of its pages. A child reader graduating from Camera Comics to U. S. Camera in the years of its duration, 1944–46, would also find graphic depictions of fatalities on its pages, for example, April 1944ʹs ‘Picture of the Month: Death on Tarawa’ (11), which showed Japanese corpses under the headline, ‘Good Japs are Dead Japs’. The U. S. Camera editorial stated, ‘Photographs like this one should spearhead our propaganda’.

Scenes of sexual titillation and graphic violence were described in U. S. Camera as ‘good pictures’, but they represented precisely what campaigning publishers, such as Parents’ Magazine, were trying to protect children from and, indeed, counteract, in their production of heroic life story comics, which offered positive models for children to live by, as the good substitute to the comics causing a ‘national disgrace’, called for by Stanley North. Parts of Camera Comics supported this educational corrective approach. The more wholesome elements of its factual content taught history, encouraged participation in school societies, and developed career skills. On other pages, however, the messages embodied exactly the problem that comics critics had identified. Kid Click, for example, represented precisely the tortured and abducted child victim that North described in his anti-comics invective. The comic stories were also populated with two of North’s other bugbears, firstly, voluptuous females in scanty attire and secondly, cheap political propaganda, in the form of racist stereotypes in a post-Pearl Harbor context.

Although the female characters in Camera Comics gave as good as they got, as gun-toting fighters as well as shot-at victims – Linda Lens memorably smashed one assailant over the head with her stiletto heel in Issue 6 – there was also casual sexual objectification. For example, when detective Art Fenton solved a crime in a photographic studio, he asked, for his reward, to watch a female glamour model on her photo shoot, making the lascivious appraisal ‘Hubba Hubba!’ (Issue 9, 18) Kid Click’s sidekick Skinny had no real interest in photography but found a camera useful for extorting contact details from beautiful girls, despite having no film loaded when he posed them for portraits (Issue 3, 36). Jim Lane: Insurance Investigator, punched a woman in the face in Issue 8 (8), while shouting, ‘Chivalry is dead!’ and ‘I’m not a Boy Scout’. These messages ran directly counter to contemporaneous messages about photography as a morally valuable youth citizenship tool, as promoted by both Scout Merit Badges and Kodak campaigns.

Advertisements, reportage pages, and comic stories all situate the Japanese as the central enemy in Camera Comics, where ‘Japs’ are crudely and repeatedly caricatured with yellow skin, protruding teeth and evil, slanted eyes. Bradley W. Wright, in Comic Book Nation, has noted how the direct, emotional and naïve appeal of comic books in America contributed to ‘the widespread popular impression, which still persists, that World War II was truly a “good war”’. He observes that racist representations of the Japanese abounded across all media, but that ‘comic books proved uniquely suited to portray the Asian enemy as many Americans saw him – a sinister, ugly subhuman creature […] using the most vicious caricatures that artist could imagine’ (Wright Citation2003, 44–45). Camera Comics was, then, not alone in its depictions, but its repeated acts of violence, racism and sexism trouble its moral position in the fraught terms of the time, when children were perceived to be uniquely at risk from comics. In the categorisations later developed by psychiatrist Frederic Wertham – as part of a broader denouncement of the perceived negative effects of comics on children’s behaviour – factual comics, historical comics, and comics serving business were termed ‘good comics’, but even these, upon close scrutiny, Wertham claimed, bastardised the truth and moulded children to ideological ends. If the worst of comics were ‘poisonous plants’, in his estimation, ‘“good” comic books are at best weeds’ (Citation1954, 313). The positive moral values of photography for children, as claimed in both educational and commercial domains, were thus destabilised by its position in a comic.

Closing reflections: Camera Comics as a site of conflicting values

Camera Comics was a short-lived enterprise, lasting only two years from 1944–46. I have not been able to locate any material providing the reasons for its wartime establishment or its post-war decline. Nonetheless, the service that it provided as an entry route for readers of U. S. Camera magazine, and as a means for camera manufacturers to keep the idea of photography alive for young people at a time when photographic supplies were not available, is demonstrable. It seamlessly moved from a wartime stand-in for photographic practice and products to a refreshed post-war vehicle for photographic consumer goods as these became available, once again, after the conflict. American manufacturers had long sought to naturalise a connection between cameras and children to create new markets and associations for their products and services; they did this earlier in the century to bring together the apparently uniquely imaginative spaces of children and photography; in the interwar years they harnessed photography to new discourses about the merits of outdoor health and organised socialisation. With the coming of a new media form that positioned children directly in its sights, and which was taken up by them avidly, comics offered a new commercial channel for promotion, especially at a wartime context. As Gabilliet notes (Citation2010, 23), this was a time when US children had little else to spend their money on.

The child photographer in the pages of Camera Comics was both a fictional figure and an imagined consumer but, importantly, these two elements were triangulated by contributions by young photographers themselves. Methodologically, those who go seeking the addressees of historical advice guidance are often left with an empty space evoked by a set of ideals (Lees-Maffei Citation2001). Photographic magazines, in addition, have been argued to ‘constitute a coherent discursive regime on popular amateur photography’, including advice alongside news, features and advertising. Together, these elements address and interpellate a photographic reader. Finding that historical reader, however, can be a complex manoeuvre between a set of moving targets, including the reader constructed in the text and the real-life purchaser of the magazine (Buse Citation2018, 50–52). In relation to children’s culture, too, it is also often the case that the actual child is hard to grasp; they are spoken for in children’s literature, or merely constituted as an image, as many scholars in children’s studies have observed (for examples, see Rose Citation1993; Sanchez-Eppler Citation2013; Moruzi, Musgrove and Leahy Citation2019). Photographs by children in Camera Comics – by Tommy Valentine, Morris Neufeld and Evan Richards – significantly bring real-life child photographers into the frame of the comic, grounding other areas marked by exaggeration and fantasy.

One must be careful, however, not to idealise these photographic contributions as representative of children’s authentic voices; they remain limited, careful selections deemed praiseworthy by adult competition judges, industry advisors and publication editors. For all the compelling reality effects of photographs, they should not be read romantically as unmediated child’s-eye views of the world. Their existence and publication were conditioned and shaped by a range of technological factors and cultural systems of filtration. As Henry Jenkins (Citation1998) has observed, more broadly, while children’s cultural production ‘is not the result of purely top-down forces of ideological and institutional control, nor is it a free space of individual expression. Children’s culture is a site of conflicting values, goals and expectations.’ Perhaps no space in the mid-century US was more strongly figured as a site of moral contestation than the children’s comic.

Without readership or circulation figures for Camera Comics, it is hard to measure its reach and its impact. Did children who were already keen photographers maintain their interest in the practice through lean times because of the comic’s coaxing, as was surely the aim of its industry supporters? Did more children buy cameras and film, post-war, because of its inspiration? In a parallel case, Carol Tilley has examined how National Comics (later DC) used Superman in campaigns to promote reading in the early 1940s; as a result, she records, libraries reported significant boosts in borrowing. But Tilley is cautious of how directly such effects can be mapped. She found, for example, ‘little direct evidence that a child who read a recommendation for Glen Round’s The Blind Colt in Flash Comics raced off to the library to check out a copy’ (Citation2013, 261). Likewise, I cannot say that sales of Kodak Brownie Reflexes were boosted by child readers of Camera Comics responding to promotions. Nonetheless, to adapt Tilley’s conclusions, in the wider knowledge of how children engaged with comics, she argues that ‘the obsessive, immersive manner in which young people interacted with comics’ encourages her belief that young people’s ‘cultural tastes were altered, stimulated, and seeded’ by what they saw (Citation2013, 262). This may well be true for comic campaigns for photography.

Whether the advertising campaigns in Camera Comics achieved their ultimate ends, they continued to promote the naturalisation of children and photography. As restrictions eased and the conflict ended, the comics continued, but Kodak adjusted its advertising approach. The 1946 issues of Camera Comics carried Kodak’s post-war promotional campaign, which also ran in Boy’s Life. This attempted to insert photography into the everyday life of American teenagers. Its messages were no longer concerned with matters of wartime urgency but the daily life of high school, where photographs could create social opportunities and bond friends. These advertisements, linked to Kodak-funded High School Photography Contests, claimed ‘young people and photography belonged together’.Footnote3 The rhetoric endured even when the war was over.

As Tilley has observed, of 1940s examples: ‘Comic books were a means for young people to engage with the world around them: comics were more than a marketing phenomenon, more than cultural junk, more than a pastime’ (Citation2013, 260). For a short period of time, comics also became a potent space for imagining fresh alignments between children and photography. In its combination of these two forms, and in its diverse contents, Camera Comics united dimensions that characterised ‘good’ and ‘bad’ in discourses at the time, meeting midway the desires of child readers and adult authorities. As I have argued through this article, in a period and place when camera supplies were unavailable, the imaginative spaces of Camera Comics created commercially valuable, if morally ambiguous, connections between photographic technologies and patriotic triumph. Motivated by commercial needs to maintain photography in the minds of enthusiasts who could no longer practice it, and to cultivate it in the minds of those yet to undertake it, Camera Comics delivered an affordable, exciting package that promoted the medium’s heroic possibilities in four-colour fantasies while glossing over its monochrome wartime realities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Annebella Pollen

Annebella Pollen is Professor of Visual and Material Culture at University of Brighton, UK. She is widely published in photography studies and is the author of five books of art and design history. She was awarded a Philip Leverhulme Prize in 2021, which she is using to research the long history of children as photographers.

Notes

1. This article is an outcome from a three-year Philip Leverhulme Prize-funded project designed to result in a book and exhibition on the history of photography by children. With thanks to Leverhulme Trust.

2. Camera Comics was a short-lived venture that lasted for nine issues, 1944–46. It began as a bi-monthly of 52 pages and later became quarterly. The full run is digitally reproduced at https://comicbookplus.com/?cid=659. To contextualise the comic in the practices of its parent company, U. S. Camera, I draw on nine issues of the magazine from a similar period in my ownership. I also draw on contemporaneous photographic instruction guides, principally the 1941 edition of Edwin Way Teale, The Boys’ Book of Photography (originally published 1939) and the 72-page 1939 Kodak booklet, Photography for Rural Young People, alongside selected advertisements and articles on photography published in US children’s magazines in the period, such as The American Boy and Boy’s Life.

3. I was able to view the full Kodak post-war advertising campaign aimed at US high school students, including this slogan, at George Eastman Museum, Rochester, USA. With thanks to Kathy Connor and Todd Gustavson.

References

- Buse, P. 2018. “The Photographer as Reader.” In Photography Reframed: New Visions in Contemporary Photographic Culture, edited by B. Burbridge and A. Pollen, 48–61. London, UK: I. B. Tauris.

- Eastman Kodak Company. 1939. Photography for Rural Young People. Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Company.

- Gabilliet, J.-P. 2010. Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books, Translated by B. Beaty and N. Nguyen. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

- Jenkins, H. 1998. “Introduction: Childhood Innocence and Other Modern Myths.” In The Children’s Culture Reader, edited by H. Jenkins, 1–37. New York: New York University Press.

- Lees-Maffei, G. 2001. “From Service to Self-Service: Advice Literature as Design Discourse, 1920-1970.” Journal of Design History 14 (3): 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/14.3.187.

- Moruzi, K., N. Musgrove, and C. P. Leahy, Edited by. 2019. Children’s Voices from the Past. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- North, S. 1940, 8 May. “A National Disgrace (And A Challenge to American Parents).” Chicago Daily News. 56.

- Raeburn, J. 2006. A Staggering Revolution: A Cultural History of Thirties Photography. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Rose, J. 1993. The Case of Peter Pan, Or, the Impossibility of Children’s Fiction. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Sanchez-Eppler, K. 2013. “In the Archives of Childhood.” In The Children’s Table: Childhood Studies and the Humanities, edited by A. M. Duane, 213–237. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- Saretzky, G. D. 2004. “U.S. Camera: A Thomas J. Maloney Chronology.” The Photo Review 4 (1): 26–27.

- Snow, R. 2016. “Photography’s Second Front: Kodak’s Serving Human Progress Through Photography Institutional Advertising Campaign.” Journal of War & Culture Studies 9 (2): 151–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/17526272.2016.1190206.

- Stilgoe, J. R. 2014. Old Fields: Photography, Glamour, and Fantasy Landscape. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

- Teale, E. W. 1941. The Boys’ Book of Photography. New York: E. P. Dutton and Co.

- Tilley, C. L. 2012. “Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications that Helped Condemn Comics.” Information & Culture 47 (4): 383–413. https://doi.org/10.7560/IC47401.

- Tilley, C. L. 2013. “’Superman Says, “Read!”’ National Comics and Reading Promotion.” Children’s Literature in Education 44 (3): 251–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-012-9193-0.

- Wertham, F. 1954. Seduction of the Innocent. New York: Rinehart and Company.

- West, N. M. 2000. Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia. Virginia: University Press of Virginia.

- Wright, B. W. 2003. Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.