ABSTRACT

It is widely acknowledged through various studies that comprehending the environment and sustainability can help children cultivate curiosity, insights, and ethical ideals, facilitating ways of enhancing public environmental literacy and leading to a more sustainable future. Environmental education in early childhood has substantial positive effects on social, economic, wellness, and educational elements, aiding in the growth of children’s abilities to become responsible young citizens. The present article examines how green informational picturebooks in India can cultivate eco-consciousness in young readers and support environmental children’s literature, motivating them to protect the earth and recognise their responsibility in environmental issues as adults. Taking Jeyanthi Manokaran’s Chipko Takes Root (2015) as a point of exploration and intervention, the article illustrates how a picturebook like this can be implemented as a means of communication for environmental protection. For this, the article emphasises how the book indulges in a streamlined recounting of the Chipko movement, incorporates regional stories, and uses effective visual representations as tools to elevate awareness about environment and sustainability among children.

Introduction

A critical ecological ontology in curriculum theory emphasises how learners engage in the world with an individualised objective of sustainability and environmental education. This mode of education aims to enhance adolescents’ environmental consciousness, competencies, perspectives, and ability to take action (Declaration Citation1977), referred to as their ecological literacy. For instance, the North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE) strives to promote knowledge about the environment and civic engagement through education to build ‘a more equitable and sustainable future’ (NAAEE Citation2022). While sustainability and environmental education are gradually becoming more prevalent as environmental problems escalate in the Anthropocene era, an economic agenda, shaped by New Public Management (Gibson-Graham and Ethan Citation2015), prioritises ‘marketability and competitiveness’ (Delors Citation1996) over social and environmental well-being in the pursuit of sustainable economic growth. Simultaneously, as Coyle (Citation2005) argues, this educational perspective has not expanded extensively enough to significantly impact public environmental literacy, as the process needs to begin from childhood, emphasising Witt and Kimple’s (Citation2008) assertion that childhood is the most vital time period for embracing and following novel and newly-learned ideas. Understanding the environment and sustainability has significant potential to guide children towards developing curiosity, insights, and ethical principles that can contribute to ‘a more sustainable world’ (Samuelsson, Li, and Hu Citation2019, 369). This approach leverages children’s inherent inquisitiveness and their capacity to interact with the natural world. The positive impacts of ECESE (Early Childhood Environment and Sustainability Education) in social, economic, wellness, and educational aspects are significant, contributing to the development of children’s skills to become young responsible citizens (Davis Citation2009).

Implementing picture books as instructional materials in early elementary education offers notable benefits. The combination of images and text actively engages and encourages young learners to acquire knowledge through various means. Research indicates that the use of picture books throughout early childhood can enhance intellectual growth due to the significant correlation between cognitive development and the application of books with illustrations. The effective use of picture books has also been associated with improved socio-cultural development, since engaging in critical thinking and verbalising thoughts and feelings regarding the images enhances children’s comprehension of their surrounding environment, culture, and society as a whole (Kümmerling-Meibauer and Meibauer Citation2013; Muthukrishnan Citation2019, 21). Picturebooks that explore significant societal and environmental topics, as well as reflect on real-life stories and historical accounts of environmental movements, can facilitate ecocritical dialogues, which refers to creating a space for learners to collectively analyse, address, and interpret the meaning of a literary work from an ecocentric viewpoint (Goga and Pujol-Valls Citation2020, 7653; Rybak Citation2023). An intriguing aspect is that these picturebooks can serve as subjects for inquiry, conversation, and critical reflection for both young readers and advanced learners.

Children’s comprehension of environmental sustainability is developed through various interactive experiences that involve the senses, hands-on activities, open-ended exploration, and educational material that is connected to specific (hi)stories. Following Salmon (Citation2000), in circumstances where the lack of environmental education resources impedes progress in enhancing ecological knowledge among students, green informational picturebooks can effectively involve children in various modes of learning about environmental issues in their early years. Green picturebooks are illustrations/visual narratives that frequently feature the colour green on their front covers and explore themes related to environmental issues, climate change, the impact of global warming, and environmental activism by employing various verbal and visual storytelling methods to captivate children’s attention (Beauvais Citation2015, 170–171). These picturebooks feature ‘nonnarrative, informative, or hybrid’ works that blend ‘facts with fiction and fantasy with realism,’ categorising them as ‘green informational picturebooks’ (Rybak Citation2023, 1). In this context, information is selected, organised, and interpreted using verbal and visual codes to make it available to laypeople, engaging them both cognitively and emotionally, as argued by Nikola von Merveldt (Citation2018, 232). Stories in these green informational picturebooks can be used as instruments for climate literacy, which Marek Oziewicz (Citation2023, 34) outlines as a comprehensive understanding of the urgent need for climate action – its facts, causes, effects, and importance – with a focus on cultivating principles, mindsets, and behavioural changes that promote planetary sustainability for the present and future generations.

Diverse perspectives are required to enhance our comprehension of sustainability. The practice of sustainability encompasses various dimensions, including geographical location, historical period, history, code of conduct, and cultural factors. This denotes that sustainability is perceived differently among countries and cultures, evolving over time and influenced by different norms and values (Pramling-Samuelsson, Li, and Hu Citation2019). In India, the initial significant action to combine environment and development was the creation of the National Council of Environmental Planning and Coordination following the landmark 1972 Conference on Human Environment in Stockholm. Subsequently, the Department for Environment was established and upgraded to a fully operational ministry. From 1972 onwards, a variety of binding and efficient rules and regulations were established to create the regulatory framework for safeguarding the environment. The education system in India has incorporated initiatives such as Mahatma Gandhi’s Basic Education, guidelines from the Education Commission (1964–66), and the National Policy on Education in 1986, which includes the Programme of Action (POA–1992). These efforts highlight the importance of integrating environmental issues into all levels of schooling. The National Policy emphasises the need to raise awareness about the environment across all age groups and social strata, starting with children (Sharma and Pandya Citation2015, 12–15). This necessitates a curriculum and syllabi that are action-oriented and progress from knowledge acquisition to cultivating environmental-friendly habits starting from childhood. In such a context, green informational picturebooks in India have the potential to foster eco-consciousness in young readers and contribute to environmental children’s literature, encouraging them to take action to safeguard the planet and acknowledge their role in environmental issues in their adult years (Anderson Citation2021, 184; Christensen Citation2021). Jeyanthi Manokaran’s Chipko Takes Root (Citation2015) is one such green informational picture book that conveys the story of Dichi, a courageous Bhotiya girl who participates in the Chipko movement to protect trees by hugging them. It is worth noting that the Bhotia tribe resides in a large region next to Tibet and Nepal, and can be located in three states of India – Sikkim, West Bengal, and Uttarakhand. The book emphasises the significance of trees and the detrimental impacts of deforestation and government-corporate development.

Picturebooks are critical for early socialisation because they serve as a means of introducing socio-cultural and ethical principles to young minds, as well as providing them with an opportunity to gain knowledge about the world outside their immediate surroundings. They acquire an understanding of the environment, distinguishing between right and wrong, as well as learning about the societal expectations that apply to children of their age. Furthermore, books provide children with exemplars – depictions of the kinds of people they can and should emulate as they mature (Weitzman et al. Citation1972, 1126). The rationale behind taking Chipko Takes Root as the focus of intervention in this article, among many other graphic novels and comics on environmental issues, is its ability to enhance children’s understanding of environmental concerns. Additionally, the book introduces them to influential individuals engaged in environmental activism and helps them become aware of local and regional environmental issues, as well as knowledge specific to certain locations. Thus, Chipko Takes Root reflects a ‘eco-globalist’ approach and impact on climate change. According to Buell (Citation2007, 232–234), this impact is a strong emotional focus on a limited physical environment that is closely connected, either real or imagined, to a larger global context. It involves the process of connecting local ecological issues to larger global issues, which is frequently alarming. Therefore, a meticulous examination of a picturebook centred around a prominent environmental movement in India may undoubtedly identify how ecological concerns affecting nearby ecosystems ultimately contribute to the broader challenges linked to climate change in the present day (Murphy Citation2024). Consequently, this might serve as a source of motivation for children to strive towards being advocates for environmental conservation and conscientious members of society as they mature.

Taking this picturebook as a point of exploration, the article illustrates how a picturebook like this can be implemented as a means of communication for environmental protection, bolstering Chawla’s (Citation1998) argument that children possess a caring nature, meaning early childhood is an ideal time to engage in environmental and sustainability education. In doing so, the article is divided into three sections: the first section discusses the streamlined recounting of the Chipko movement, blending facts with fiction as depicted in Chipko Takes Root; the second section emphasises the movement itself and the information it provides in terms of regional stories; and the last section underscores how the book can educate children and elevate awareness about the environment and sustainability.

Jeyanthi Manokaran’s Chipko Takes Root: fictional account with illustrations

Literature has the potential to affect how individuals perceive the world and nature, making it an important tool in inspiring young readers to reconnect with the endangered natural environment (Harju and Rouse Citation2018; Røskeland Citation2018). This pattern is anticipated due to the incorporation of international recommendations on Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations Citation2020) in the latest national curriculum frameworks of various countries. There is significant concern regarding the environmental problem, and picturebooks are occasionally viewed as a platform for promoting environmental protection, mostly from an educational rather than a literary perspective. To incorporate ecocritical reading and environmental consciousness through book-based interaction with learners and educators, the writers of green picturebooks advocate and construct what Nina et al. (Citation2023) characterise as ‘ecocritical dialogues,’ an effective technique to integrate both. This merging of the ecocritical and the literary is, however, not an underpinning for all of the present methods of environmentalism and books for children. As Kanatsouli (Citation2005, 535) reminds us, there is a segment of books that are inconsistent because they contend to be literary but in reality focus on educating young readers with inadequately composed narratives that lack action, have superficial characters, and lack setting. These books essentially just ‘lecture’ children on the significance of cultivating ‘ecological awareness’ in an outmoded and didactic manner. Taking this into consideration, Soulioti (Citation2022) notes that one of the most pressing needs of the discipline of children’s literature is an attitude towards these kinds of books that takes into consideration both the ecocritical worth of the books and the level of craftsmanship of the literary structure contained within them. In such a context, Jeyanthi Manokaran’s open-access picture book, Chipko Takes Root, engages young readers with verbal and visual representations to convey information concerning the Chipko movement. The book, as outlined by Nikola von Merveldt (Citation2018, 232), excels at fundamental facts to spark a desire to learn, stimulate questions, and foster a sense of solidarity, thereby standing out from academic texts by striving to engage, educate, and motivate readers, which is essential to fostering climate literacy.

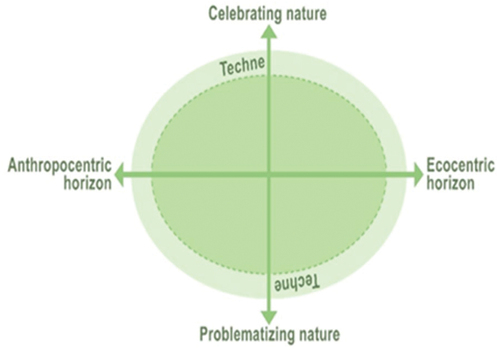

The Chipko movement and the narrative of Dichi, a young girlchild and her community, saving the forest by embracing trees, are discussed in this article employing a modern analytical framework known as The Nature in Culture Matrix (NatCul Matrix). The NatCul Matrix, developed in 2013 by a Scandinavian research group called Nature in Children’s Literature (NaChiLit), examines how literary works address the connections between nature and humanity or nature and society. The tool is a conceptual framework that integrates key concepts of ecocritical analysis for contemplation and evaluation. The rationale here is that this tool is a graphical illustration of how literary works or specific aspects within them either focus on human-centred or nature-centred perspectives. They may depict an idealised view of nature or raise questions about the practical significance humans assign to their natural environment (Soulioti Citation2022, 457). The given below is the model of The Nature in Culture Matrix (NatCul Matrix):

Figure 1. The Nature in Culture Matrix (CitationNature in Children’s Literature and Culture n.p).

The matrix is a coordinate system that facilitates the discussion of different cultural expressions in connection with a vertical continuum from celebration to problematisation of nature, and a horizontal continuum from an anthropocentric to an ecocentric perspective. The lines in the coordinate system illustrate how human perspectives of nature are influenced by their positioning in nature at both fundamental and everyday levels. The indicator ‘Celebrating nature’ suggests that nature is perceived as a pristine and peaceful environment, akin to the pastoral tradition. This idealised portrayal of nature is influenced by the notion of the ‘pure child’ or the ‘child of nature’ in Rousseau’s cultural and educational standards (Garrard Citation2012a, 37–66; Soulioti Citation2022). Conversely, ‘Problematizing nature’ suggests that nature can be viewed as problematic, since it is a space where environmental imbalances, climate change, and the extinction of species and plants indicate times of crisis, causing the concept to fluctuate between the ideal and the problematic (Gifford Citation2014; Nina et al. Citation2023, 1433). The indicator ‘Anthropocentric horizon’ signifies human dominance over nature, while the ‘Ecocentric horizon’ perceives nature holistically and acknowledges the intrinsic worth and rights of all natural elements, such as mountains, waterways, flora and fauna, and humans. The two axes are defined by a third dimension referred to as ‘Techne,’ derived from ancient Greek and referring to the notion of rhetoric, which is the art of persuasion according to Aristotle. Here, it refers to deliberately shaping oneself, the external environment, and society at large in a way that, similar to persuasion, highlights that all literary works for children and young adults include mediated and manufactured graphic representations of the natural world (Boellstorf Citation2015, 55; Soulioti Citation2022, 457–458). The discussion below focuses on how the four indicators are prominently featured in the picturebook Chipko Takes Root, considering the entire matrix as the method of study.

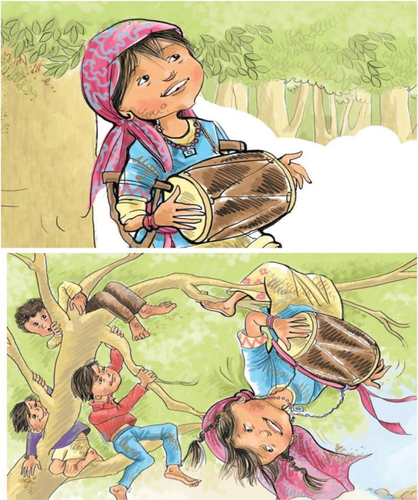

While the cover of this picture book illustrates Dichi happily playing her dholak under a tree, the opening page portrays Dichi with her dholak hanging from the branches of her favourite tree, her three brothers climbing the identical tree (), and their sheep jostling and bleating in the meadow below. The author’s celebration of the natural world in this book is highlighted by the greenness of the illustrations, as well as the enjoyment of the children, the representation of the tree, and the presence of non-human subjects. Thus, the book’s beginning with an illustration depicting Dichi and her brothers engaged in fun time within their local environment, as well as the tree as the medium of their play, serves to emphasise their tranquil and happy coexistence with nature. This graphic exemplifies the ‘sociomateriality method’ (Orlikowski Citation2010) by demonstrating the connection between ecocentrism and radical reflexivity, providing a simple perspective on our interconnectedness with the earth, and emphasising our personal and collective responsibility to take action as the book later unfolds.

Figure 2. Dichi with her dholak and her hanging from the branches of the ash tree (Manokaran Citation2015).

On another occasion, Dichi is seen sitting on ‘her’ ash tree (), looking down at two crutches on the greenery underneath, and listening to the tree’s whispers about its branches: ‘My branches are thin and fat, long and short, I’m strong’ (Manokaran Citation2015, 9). Dichi ascends to a higher altitude for a better view of a bird’s nest, follows her fingers after an army of ants, inhales the refreshing aroma of ash leaves, and then addresses the tree, ‘You’re my ash tree. Chacha says I’m just like you, sturdy as a yak. With these crutches, I’ll be strong and fierce as a Yeti’ (Manokaran Citation2015, 9). The affinity between Dichi and her ash tree mirrors John Muir’s ecocentric viewpoint, which recognises the inherent value of non-human organisms beyond their impact on human progress. From this perspective, humans are not distinct from or superior to nature but are part of nature’s interconnected system. Human progress should be pursued as long as it does not harm the balance of the natural ecosystems to which they are linked (Hoffman and Sandelands Citation2005, 144).

Figure 3. Dichi is sitting on ‘her’ ash tree (Manokaran Citation2015).

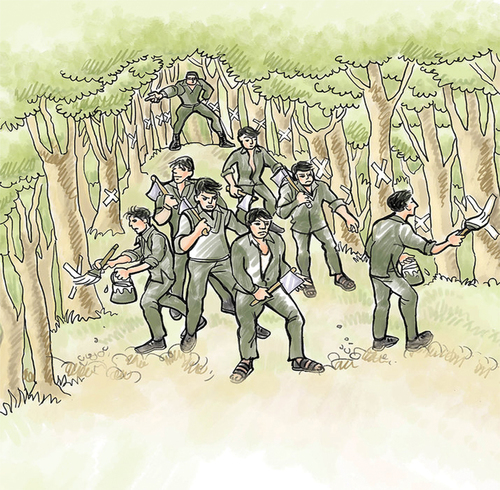

This ecocentric way of experiencing nature is entirely broken when Dichi learns about the sports goods company that cut down their chir, pine, deodar, and ash trees in order to manufacture cricket bats and other sporting goods. Dichi posed the question, ‘Why do they chop our forests? Can’t they see the landslides thunder down the mountainside? The fierce flash floods that carry away the poor folk?’ (Manokaran Citation2015, 6). Her dada and the power that Dichi had in her left leg were both taken by those floods, rendering Dichi unable to feel anything below the knee. The reference to deforestation and the oppression of disadvantaged individuals in the face of environmental catastrophes contributes to the anthropocentric worldview that prioritises human needs and evaluates nature based on these needs. This perspective emphasises that continuous human advancement can be achieved by utilising nature’s boundless resources. This perspective, influenced by Francis Bacon’s belief in extracting secrets of nature through exploration, views humans as distinct from and above nature. It regards nature as a passive mechanism, perpetually grouped and driven by external forces rather than internal ones. One major flaw of anthropocentric ethics in this instance is its refusal to see (non)humans as ‘morally significant agents’ (Cafaro and Primack Citation2014; Gladwin, Kennelly, and Krause Citation1995; Hoffman and Sandelands Citation2005; Kopnina Citation2019). This anthropocentric perspective becomes more apparent when a group of uniformed axemen headed by contractor Chand arrive in the village and bark out commands to meticulously mark the chir, pine, deodar, and ash trees for auction with a chalky white X (). Chand is the one who is in charge of the axemen. As they make their way into her woodland, which is filled with numerous trees, these men emerge in a single file. Although their khaki clothes are shabby, their axes sparkle as they move forward, reminding of C. S. Lewis’s (Citation1953, 44; italics original) observation, ‘We reduce things to mere Nature in order that we may “conquer” them. We are always conquering Nature, because “Nature” is the name for what we have, to some extent, conquer.’ The sound of the axemen’s footsteps reverberates down the mountain slope as they continue to walk rapidly. This demonstrates that the short-term benefit of cutting down trees for profit and commercialisation, given the long-term repercussions of deforestation, is not a sustainable practice for preserving socio-environmental balance.

Figure 4. The marking of the chir, pine, deodar, and ash trees for auction (Manokaran Citation2015).

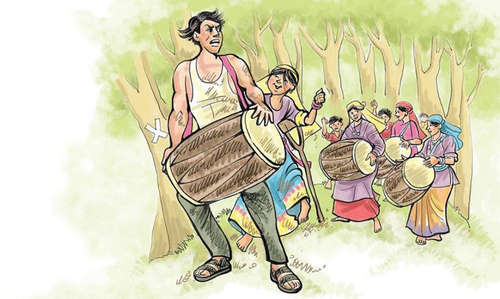

Social and ecological justice are considered particular consequences of a spectrum between ecocentrism and anthropocentrism in environmental philosophy (Schlosberg Citation2004). Ecological justice here specifically targets individuals who lack the ability to protect their rights under enforceable circumstances. Baxter (Citation2005, 4) contends that nonhuman species are entitled to ‘distributive justice’ about an equitable portion of the environmental resources necessary for survival and growth. While those axemen deny ecological justice and the ‘Rights of Nature’ (Borràs Citation2016), Dichi and her communities believe that a comprehensive ecological ethics is essential for long-term conservation efforts, emphasising a holistic concept of justice that intertwines social justice for themselves and ecological justice for their beloved trees. Dichi and her community exhibit the premise of achieving justice through their collective activism. Gauri, one elder woman from the community, notes that although they are uneducated, they are knowledgeable individuals who will not permit the loggers to sell our valuable trees to any business entities. The locals decide to display their non-violent movement by hugging the chir, pine, deodar, and ash trees in the forests, as these trees cannot protect themselves, thus culminating in the members marching into the forest while shouting their Chipko slogan. Dichi grabs her dholak to resonate with the children’s chant as they move energetically (). ‘What do these forests bear?’ Dichi asks loudly, and ‘Soil, water and pure air’ (Manokaran Citation2015, 12–13) the children respond in unison, imitating her with lively movements and demonstrating the broader notion of sustainability and environmental activism, where children also actively engage. These collective statements represent a two-part notion: one is the importance of land ethics, and the other is the fundamental values of deep ecology. The land ethic value, as Leopold (Citation1949, 203–204) contends, expands the borders of the Bhotiya community to encompass soils, waterways, trees, and animals. A land ethic does not have the authority to prevent alterations, control, and exploitation of these ‘resources,’ but it does acknowledge their entitlement for continued existence and, to a certain extent, their persistence in an undamaged condition within the ecosystem of the Bhotiya community. Furthermore, the Chipko slogan of Dichi and her community underscores the first principle of the Deep Ecology Platform (Devall and Sessions Citation1985, 69), stating that we should recognise the intrinsic value of non-human life on Earth, regardless of its practical utility for specific human objectives.

Figure 5. Dichi and other children are shouting their slogans (Manokaran Citation2015).

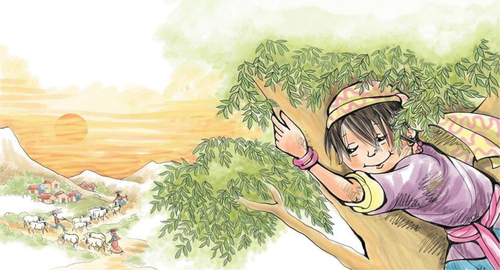

The pragmatic approach in the children’s slogans is evident in environmental education and education for sustainable development, posing an impediment to the overarching concept of sustainability. The premise of sustainable development focuses on supporting the requirements of human populations but often ignores the consideration of addressing the basic needs and existential crises of non-human entities. As Crist (Citation2012, 145) argues, ‘How many people, and at what level of consumption, can live on the Earth without turning the Earth into a human colony founded on the genocide of its non-human indigenes?’ Implementing justice in the management of forest resources, as mentioned by children, contributes to the equitable protection of both human and non-human entities. Ecocentrism and ecojustice in this context emphasise the inherent value of non-human entities, questioning the prevailing notion of assigning greater value to certain organisms and dismissing the idea of valuing nature only based on its usefulness to humans (Crist Citation2012; Curry Citation2011). This sustainable approach coupled with the ecocentric notion is further reflected in the collective slogan of the women in that village: ‘Soil ours, water ours, ours are these forests too. Our forefathers raised these, it is we who must protect these too’ (Manokaran Citation2015, 16), thereby reflecting that injustice transcends financial prosperity and cultural determination, impacting the continued existence of many organisms (S. Abram et al. Citation2016). Dichi’s ongoing association with her favourite ash tree () is further evidence of this. On every occasion available to her, she ascends this tree. The tree’s tender foliage has a calming effect, while its smooth outer layer refreshes her cheeks, as if it were softly communicating with her. Dichi strongly desires the thriving of the tree and opposes its exploitation for capitalist and commercial gains. The words ‘No one must take away my ash! Time stands still. All is right with the world’ (Manokaran Citation2015, 18) is spoken with conviction by her, despite the fact that she is aware of the imminent threat.

Figure 6. Dichi with her favourite ash tree (Manokaran Citation2015).

On the initial attempt, the contractor Chand and his axemen cannot manage to penetrate the forest and cut down the trees because the villagers are driving them away. Meanwhile, the government manipulates the menfolk by sending them to a distant location to watch a film, which is an unexpected and unignorably treat. Movies are not frequently seen in these parts, so the government assumes that women and children will not be capable of safeguarding their trees. The moment Dichi discovers Chand and her axemen making their way towards her forest, she is overcome with apprehension, searches for her crutches, and stumbles back to her home while yelling, ‘Help! My ash! They can’t cut my ash! […] The X that marks every tree to be cut, feels like a gash – a wound that will never heal. My Ash!’ (Manokaran Citation2015, 19–24). After wrapping her arms around her tree, Dichi’s quivering fingers scratched at the bark in an attempt to remove the X. The unwavering affection that Dichi has for the tree exemplifies the concept of ‘bioproportionality’ (Mathews Citation2016), which is an ethical principle that goes beyond the premise of ‘viability’ and fosters the abundance and flourishing of all species in accordance with the requirements that they have for their survival. This bioproportional drive motivates Dichi and other children to even weave a shawl, work at the soap unit, and work at the water mill in order to repay the debt of their uncle, who, as a consequence of acute poverty, is compelled to take a job as an axeman. The uncle feels empowered by the words of these children, resulting in the removal of his uniform, taking up Dichi’s dholak, and joining the children in their efforts to save their beloved trees (). This highlights how children and young people are engaging in the climate crisis fight independently, alongside friends and relatives, by exerting impact through subtle acts that Morten and Benwell (Citation2021) refer to as young people’s everyday climate crisis activism.

Figure 7. Uncle with the children and other village women (Manokaran Citation2015).

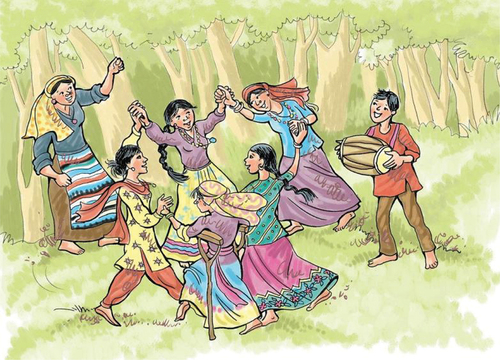

Dichi, along with the other children, encourages the village women to leave their household chores, come together, play the dholaks, and sing their chipko slogan. Contractor Chand instructs Dichi to vacate the forest, which for him only contains ‘timber, resin, and foreign exchange,’ and commands his axemen to cut down the trees, leading Dichi to cry out, ‘Chipko! Hug the trees!’ (Manokaran Citation2015, 28–29). This activism involves individual and group actions aimed at changing, adjusting, or disrupting both personal and others’ regular behaviours in response to concerns about the adverse effects of capitalist routines on the environment as they are understood, appreciated, and envisioned. Compassionate connections with nature and ecosystems serve as the driving force behind this activism, which manifests itself in both public and private settings (Walker Citation2017, 14). Women and children embrace the designated trees, confront the contractor Chand’s verbal assault, and sing their chipko slogan until the loggers abandon their mission, showcasing the communities’ ‘environmental activism’ (Dono, Webb, and Richardson Citation2010, 178) as a collaborative effort to engage in environmental protection and advocate the environmental movement in its entirety. With each other by their sides, the villagers do a triumphant dance of victory (). The ash tree swings in response to the wind of protest and movement. Resting her cheek against the bark of the tree, Dichi feels the rustling of its feathery leaves as the evening breeze blows, and the story concludes with Dichi whispering to her ash tree, ‘I’m like you, strong and fierce like a Yeti…sturdy as a yak’ (Manokaran Citation2015, 31).

Figure 8. Collective solidarity and victory (Manokaran Citation2015).

Retelling the (hi)story as source of information: the chipko movement

Chipko Takes Root exhibits a vibrant and potent aptitude to create ecocentric approaches to conceiving, being, and responding by generating communication and conceptual frameworks to express objectives, recognise detrimental developmental scenarios, and form alliances. Human brain architecture has evolved to interpret narratives, implying that the way we process tangible information is primarily through culturally dominant narratives, also known as ‘stories-we-live-by’ (Stibbe Citation2015, 6) as well as ‘intersubjective imagined orders’ (Harari Citation2015, 117). The future of humanity will be shaped by the stories we decide to share and our willingness to envision the steps needed to shift towards a more sustainable civilisation (Oziewicz Citation2022). Chipko Takes Root utilises visual elements to stimulate ‘anticipatory imagination’ (Oziewicz Citation2023, 35) and prompt action by informing readers about what it stands for. Jeyanthi Manokaran, the author and illustrator of this picturebook acknowledges that,

Like Dichi in this book, a little Bhotiya girl spots the axemen and alerts the village women who march into the forest with shouts of Chipko slogans.Without violence, they block the axemen from cutting the trees. In 1980, theGovernment of India passes a law to protect these forests. This is one of the first important environmental movements in India (Manokaran Citation2015, 36).

This information encourages readers, including children, educators, learners, and facilitators, to delve deeper into this movement, providing insight into its origins and evolution within environmental discourses in India.

According to Chen and Hsiao (Citation2014), engaging in a story discussion is crucial in children’s literature since it allows educators to assess children’s understanding of the subject matter, protagonists, and storyline of picture books. Similar to this, this section briefly discusses the Chipko movement within the broader context of grassroots environmentalism in India, acknowledging that the analysis of the rich history of this movement is beyond the aims and scope of this article. The Chipko movement, which gained global recognition, began in the early 1970s in the Garhwal Himalayas. The movement occurred at a time when there was no effort towards environmental preservation in the country, and Indian policymakers had not fully grasped the importance of ecological sustainability in fostering economic growth that was environmentally friendly. British colonisers started exploiting the region’s natural riches in 1815, when the East India Company gained authority over the country. The company primarily sought easy accessibility to the Himalayan passes between Nepal and India and aimed to dominate the trading route historically known as the Silk Road. The company recognised the potential for utilising the forest for timber, resin, feed, and other resources. In Post-independence period, government of India maintained colonial forestry practices. Over time, the percentage of the forest set aside as reserved grew, resulting in local residents having access to a decreasing amount of forest for their daily activities (Rangan Citation2000, 128; Shah Citation2008). Local communities protested for several years against existing forest management practices, the cutting down of trees for commercial purposes, and persistent poverty. The challenges in the region worsened due to strong monsoon rains that caused destruction to houses, agricultural land, crop fields, bridges, and roadways throughout an area of almost 300 square kilometres. Reports indicate that deforestation and soil erosion in restricted forestlands were significant factors contributing to the considerable devastation (Haigh Citation1988; Shah Citation2008; Tewari Citation1995).

Villages damaged by landslides were located beneath extensively deforested areas. The indigenous people’s traditional knowledge about the connections among deforestation, landslides, and flooding was sadly proven true once the flooding occurred (Guha Citation2002). The national government in New Delhi and logging business corporations had long disregarded and belittled the specific forestry management expertise of the local community. In early 1973, a local employment cooperative asked the government for a supply of ash trees to create agricultural equipment. The Forest Service denied the proposal but promptly provided the identical piece of land to Symonds Co., a company that manufactures cricket bats for sale. The cooperative members were furious about the decision and gathered to strategize regarding how to stop those with financial interests from cutting down the designated trees. The idea of embracing the trees, known as ‘chipko’ in the local language, was probably conceived at this meeting. The idea involved individuals working together, embracing trees designated for cutting down, and holding onto them until the loggers left. Contractors hired by Symonds arrived at the forest to find individuals embracing each tree designated for cutting down. The opposition was against the cutting down of trees by contractors authorised by the forest department, which was leading to significant harm to the mountain ecology and resulting in severe social and economic disruptions, mainly affecting the impoverished and marginalised communities, notably women. The strategy used involved non-violent protest, where people, particularly women, embraced the trees to stop the contractors from cutting them down. The image below () and other visuals of the Chipko movement highlight the authenticity of the illustrations in Jeyanthi Manokaran’s picturebook Chipko Takes Root.

Figure 9. Chipko activists in the Himalayas embrace the tree (Singh Citation1994, Photograph. Sepia Eye).

The protesters remained steadfast, causing the contractors to depart from the forest without achieving their goal. As news of the effective resistance spread, neighbouring villages used the same strategy to hinder commercial logging activities (Bhatt Citation1997; Rangan Citation2000; Guha Citation2002; Shah Citation2008, 36–38; Srivastava Citation2015). The grassroots environmentalism challenged the national focus on development promoted by the modernist ideology of the Indian state. It presented an alternative narrative emphasising the interconnected and intertwined interaction between humans and the environment. The movement promoted the growth of small-scale businesses, sustainable and equitable utilisation of forests for local advantages, as well as proactive and remedial measures for environmental conservation. Various grassroots environmental activism initiatives have emerged following the Chipko movement. These include movements to protect forests, oppose extractive industries, resist megadams, save rivers like the Ganga, conserve biodiversity, and promote sustainable agricultural practices (Srivastava Citation2015). It is worth mentioning that the Chipko movement was a component of global ecological activism; certain individuals perceive it as ‘environmentalism of the poor’ and a form of resistance against colonial capitalism, holding relevance in the age of the Anthropocene (Badri Citation2024). Thus, the message that Jeyanthi Manokaran’s Chipko Takes Root provides is that Chipko symbolises the enduring principle that soil and water are the fundamental resources of existence. Natural forests are the origin of rivers and play a crucial role in the formation of soil. No tangible progress or lasting economic success can occur until we enhance these two fundamental resources. The fundamental concept behind Chipko’s slogan is that environment equals permanent economy. Chipko is a rebellion against the destruction of the environment. The goal is to revive the principles of forest culture by prioritising spirituality as the foundation for science and technology, aiming to benefit all living creatures (Bahuguna Citation1987, 247) and deciphering the core and simplest forms of messages interwoven with this movement.

Ecological literacy, education and sustainability

Children and young people are most heavily affected by the severe consequences of the worldwide climate crisis, emphasising that they will face growing challenges to their overall well-being and future livelihoods due to upheavals in the socio-economic, cultural, and ecological components of their everyday existence (Clark et al. Citation2020). In such a circumstance, a green informational picture book such as Jeyanthi Manokaran’s Chipko Takes Root can serve as a creative piece of writing and an artistic medium for environmental education in a classroom setting and seek to foster a greater understanding and appreciation of nature by promoting a sustainable and considerate relationship with the environment. This is further illustrated by a statement made by one of the Chipko activists: ‘I would not be there to taste the fruits of this tree. But my grandchildren and their children would taste its fruits’ (quoted in Lakshmi Citation2000). Here, this picturebook can serve as a tool for promoting ‘ecological literacy’ (Risser Citation1986), which encompasses knowledge, concern, and practical skills (Orr Citation1991, 92). Ecological literacy involves comprehending the interaction between humans and ecosystems and attaining sustainability in this relationship. Education for ecological literacy is comprehensive and interdisciplinary, viewing humans as an integral component of the natural world. The process begins with childhood outdoor and learning activities, evolves into empathy and consideration for other living beings, and culminates in a comprehension of ecological systems. Moreover, it involves active participation and highlights the significance of the connection to a certain place (Hammarsten et al. Citation2019, 228). An ecologically literate individual perceives environmental realities through a holistic perspective that considers humans as an integral part of the natural environment, rather than distinct from it (Capra Citation1996).

Ecological literacy encompasses four crucial components: the capacity to analyse, evaluate, engage in critical thinking, and anticipate the long-term consequences of a behaviour on the environment; a sense of concern, affection, acknowledgement, and understanding for all living beings; the capacity to be creative and develop methods that contribute to energy adaptation and decisions that foster sustainability; and the experience of awe and gratitude towards the environment as a whole (Center for Ecoliteracy Citation2013; Muthukrishnan Citation2019, 20). The picturebook Chipko Takes Root effectively portrays the deep emotional connection between Dichi and her Ash tree, as well as her determination to protect it. Additionally, it highlights the community’s collective decision to embrace the trees as a means of preserving their local ecosystems. The frequent reference to Dichi and her tree, the conversation they have, and the reciprocal relationship demonstrate the dynamic and dialogic interconnectedness between people and non-human entities. As Abram (Citation1996, 88) notes,

To touch the coarse skin of a tree is thus, at the same time, to experience one’s own tactility, to feel oneself touched by the tree. […] We can experience things – can touch, hear and taste things – only because, as bodies, we ourselves are entirely a part of the sensible field, and have our own textures, sounds and tastes. We can perceive things only because we ourselves are entirely a part of the sensible world that we perceive! We might as well say that we are organs of this world, flesh of its flesh, and that the world is perceiving itself through us.

Chipko Takes Root promotes ecological literacy using critical place-based pedagogy, which includes developing identities and meaning-making processes by connecting individuals to their community and natural surroundings. Critical place-based pedagogy perceives locations as educational spaces and prioritises an equitable and encouraging atmosphere for learning. It seeks to provide learners with a sense of control over their own understanding and fosters their active participation in democratic processes, such as engaging with environmental problems and addressing sustainability issues. This pedagogy emphasises the importance of interrogating and working collaboratively as essential aspects of a critical educational approach (Mahmoudi et al. Citation2012; Häggström and Schmidt Citation2020, 1730–1731). The fictional account of Dichi and her community, the illustrations of trees and the ecosystem, the anthropocentric and ecocentric perspectives on nature, and the environmental activism of Dichi and her companions assist learners in exploring three important elements of education: comprehending local histories and environmentalism, learning to coexist and care, and developing ecological awareness. This picturebook addresses place-based pedagogy in India’s Himalayan highlands and the Chipko movement, empowering children through Dichi’s actions and words and encouraging them to question environmental and sustainability issues, as well as local and regional politics and developmental strategies on a larger scale. Schmidt (Citation2017, 168) argues that contemplating and questioning places, people, and the environment might be figuratively likened to interpreting the world as a text, connecting local concerns to global issues.

Ecological literacy emphasises humans as essential components of ecosystems and acknowledges the impact of their actions on forests. as depicted in this picture book. Environmental education pertaining to this book involves learners utilising the content to cultivate awareness of their ethical interactions with the environment, strengthen their knowledge of forest conservation, prompt them to address developmental concerns, and motivate them to contribute towards sustainable development. As ‘simplifcation, schematic representation, and metaphor can make abstract concepts tangible’ (Kearns and Kearns Citation2020, 147), the illustrations in this picturebook employ of a variety of instruments, such as green and other colours, visuals of vehicles, uniforms and axes, animals, trees, and other non-human entities, and they vividly convey the feelings of sadness, nervousness, and happiness of Dichi and her communities. This culminates in shifting the narration from ‘a literature of facts’ (Fisher Citation1972) to ‘a literature of questions”’ (Sanders Citation2018) and a sustainable way of perceiving nature.

Conclusion

Following Tien and Wu’s (Citation2010) argument that children between the ages of 5–8 are the most appropriate age group regarding learning about environmental education through picture books, Jeyanthi Manokaran’s Chipko Takes Root, a level 4 green informational picture book, serves as an effective medium for promoting ‘progressive pedagogy’ (Garrard Citation2012b) and fostering environmental responsibility. It underscores the significance of environmentally conscious practice as a means to comprehend the interactions of ecologies at local, regional, and global levels within cultural frameworks (Gaard Citation2009, 326), as it is essential to cultivate environmental awareness locally and promote worldwide responsibility. Picturebooks such as Chipko Takes Root can promote ‘ecological wisdom’ (Wang, Palazzo, and Carper Citation2016) by combining ecological awareness with location-specific knowledge in socio-ecological practices to achieve mutually beneficial relationships between humans and the natural world. Through the incorporation of a heteroglossia of simplified stories and expressions, including nonverbal utterances, which are interpreted through visuals, emphasised representations, and phrases, a green informational picturebook has the potential to generate an ‘ecocritical dialogic space’ (Nina et al. Citation2023). This space strives to merge collaborative idea-sharing with a considerate understanding of both the readers and the broader ecosystem of resources and organisms. It is important to incorporate more green picturebooks in the teaching-learning process to provide children with examples to emulate and pluralistic viewpoints on environmental sustainability, hoping that these may assist learners in developing a sense of care and agency, as well as enhancing their environmental awareness and ecological thinking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abram, D. 1996. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Vintage Books.

- Abram, S., G. Acciaioli, A. Baviskar, H. Kopnina, D. Nonini, and V. Strang. 2016. “Special Module: Plenary Debate from the IUAES World Congress 2013: Evolving Humanity, Emerging Worlds, 5–10 August 2013.” Anthropological Forum 26 (1): 74–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2015.1102229.

- Anderson, B. 2021. “Reimagining Plastic Pollution and Climate Activism: Contradictions of Eco-Education in Rachel Hope Allison’s I’m Not a Plastic Bag.” The Lion and the Unicorn 45 (2): 172–191. https://doi.org/10.1353/uni.2021.0014.

- Badri, A. 2024. “Feeling for the Anthropocene: Affective Relations and Ecological Activism in the Global South.” International Affairs 100 (2): 731–749. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiae010.

- Bahuguna, S. 1987. “The Chipko: A people’s Movement.” In The Himalayan Heritage, edited by M. K. Raha, 238–248. New Dehli: Gian Publishing House.

- Baxter, B. 2005. A Theory of Ecological Justice. New York: Routledge.

- Beauvais, C. 2015. The Mighty Child: Time and Power in Children’s Literature. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Bhatt, C. P. 1997. The Future of Large Projects in the Himalayas. Nainital. Nainital: People’s Association forHimalaya Area Research.

- Boellstorf, T. 2015. Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Borràs, S. 2016. “New Transitions from Human Rights to the Environment to the Rights of Nature.”Transnational Environmental Law 5 (1): 113–143. https://doi.org/10.1017/S204710251500028X.

- Buell, L. 2007. “Ecoglobalist Affects: The Emergence of U.S. Environmental Imagination on a Planetary Scale.” In Shades of the Planet: American Literature As World Literature, edited by W. C. Dimock and L. Buell, 227–248. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Cafaro, P., and R. Primack. 2014. “Species Extinction Is a Great Moral Wrong.” Biological Conservation 170:1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.12.022.

- Capra, F. 1996. The Web of Life. A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

- Center for Ecoliteracy. 2013. “Discover: Competencies.” Ecoliteracy. http://www.ecoliteracy.org/taxonomy/term/84.

- Chawla, L. 1998. “Significant Life Experiences Revisited: A Review of Research on Sources of Environmental Sensitivity.” The Journal of Environmental Education 29 (3): 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958969809599114.

- Chen, C. M., and C. Y. Hsiao. 2014. “An Investigation of kindergarteners’ Understanding of Picture Books Through Their Drawings.” Proceedings of the GCIN Conference, Hong Kong.

- Christensen, N. 2021. “Agency.” In Keywords for Children’s Literature: Second Edition, edited by P. Nel, L. Paul, and N. Christensen, 10–13. New York: New York University Press.

- Clark, H., A. Marie Coll-Seck, A. Banerjee, S. Peterson, S. L. Dalglish, S. Ameratunga, D. Balabanova, et al. 2020. “A Future for the world’s Children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission.” The Lancet 395 (10224): 605–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32540-1.

- Coyle, K. 2005. Environmental Literacy in America. What Ten Years of NEETF/Roper Research and Related Studies Say About Environmental Literacy in the U.S. Washington, DC: The National Environmental Education & Training Foundation.

- Crist, E. 2012. “Abundant Earth and Population.” In Life on the Brink: Environmentalists Confront Overpopulation, edited by P. Cafaro and E. Crist, 141–153. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- Curry, P. 2011. Ecological Ethics: An Introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Davis, J. 2009. “Revealing the Research ‘Hole’of Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: A Preliminary Survey of the Literature.” Environmental Education Research 15 (2): 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620802710607.

- Declaration, T. 1977. https://www.gdrc.org/uem/ee/tbilisi.html.

- Delors, J. 1996. Learning: The Treasure Within: Report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century. Paris: Unesco Publications.

- Devall, B., and G. Sessions. 1985. Deep Ecology: Living As if Nature Mattered. Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith.

- Dono, J., J. Webb, and B. Richardson. 2010. “The Relationship Between Environmental Activism, Pro-Environmental Behaviour and Social Identity.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2): 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.11.006.

- Fisher, M. 1972. Matters of Fact: Aspects of Non-Fiction for Children. Leicester: Brock Hampton Press.

- Gaard, G. 2009. “Children’s Environmental Literature: From Ecocriticism to Ecopedagogy.” Neohelicon 36 (2): 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11059-009-0003-7.

- Garrard, G. 2012a. Ecocriticism. London: Routledge.

- Garrard, G. 2012b. “Introduction.” In Teaching Ecocriticism and Green Cultural Studies, edited by G. Garrard, 1–10. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K., and M. Ethan. 2015. “Economy As Ecological Livelihood.” In Manifesto for Living in the Anthropocene, edited by K. Gibson, D. B. Rose, and R. Fincher, 7–16. New York: Punctum Books.

- Gifford, T. 2014. “Pastoral, Anti-Pastoral, and Post-Pastoral.” In The Cambridge Companion to Literature and the Environment, edited by L. Westling, 17–30. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gladwin, T. N., J. J. Kennelly, and T.-S. Krause. 1995. “Shifting Paradigms for Sustainable Development: Implications for Management Theory and Research.” Academy of Management Review 20 (4): 874–907. https://doi.org/10.2307/258959.

- Goga, N., and M. Pujol-Valls. 2020. “Ecocritical Engagement with Picturebook Through Literature Conversations About Beatrice Alemagne’s On a Magical Do-Nothing Day.” Sustainability 12 (18): 7653. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187653.

- Guha, R. 2002. “Chipko: A Social History of an ‘Environmental’ Movement.” In Social Movements and the State, edited by G. Shah, 423–454. New Delhi: Sage.

- Häggström, M., and C. Schmidt. 2020. “Enhancing children’s Literacy and Ecological Literacy Through Critical Place-Based Pedagogy.” Environmental Education Research 26 (12): 1729–1745. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1812537.

- Haigh, M. J. 1988. “Understanding ‘Chipko’: The Himalayan people’s Movement for Forest Conservation.” International Journal of Environmental Studies 31 (2–3): 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207238808710418.

- Hammarsten, M., P. Askerlund, E. Almers, H. Avery, and T. Samuelsson. 2019. “Developing Ecological Literacy in a Forest Garden: Children’s Perspectives.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 19 (3): 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1517371.

- Harari, Y. N. 2015. Sapiens: A brief history of humankind. New York: HarperCollins.

- Harju, M.-L., and D. Rouse. 2018. ““Keeping Some Wildness Always alive”: Posthumanism and the Animality of children’s Literature and Play.” Children’s Literature in Education 49:447–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-017-9329-3.

- Hoffman, A. J., and L. E. Sandelands. 2005. “Getting Right with Nature: Anthropocentrism, Ecocentrism, and Theocentrism.” Organization & Environment 18 (2): 141–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026605276197.

- Kanatsouli, M. 2005. “Ecology and Children’s Literature.” In Environmental Education, edited by A. Georgopoulos, 535–549. Athens: Gutenberg.

- Kearns, C., and N. Kearns. 2020. “The Role of Comics in Public Health Communication During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine 43 (3): 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453054.2020.1761248.

- Kopnina, H. 2019. “Ecocentric Education: Student Reflections on Anthropocentrism–Ecocentrism Continuum and Justice.” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 13 (1): 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408219840567.

- Kümmerling-Meibauer, B., and J. Meibauer. 2013. “Towards a Cognitive Theory of Picturebooks.” International Research in Children’s Literature 6 (2): 143–160. https://doi.org/10.3366/ircl.2013.0095.

- Lakshmi, C. S. 2000. “Lessons from the Mountains.” The Hindu. https://uttarakhand.org/2000/05/hindu-lessons-from-the-mountains-the-story-of-gaura-devi/.

- Leopold, A. 1949. A Sand County Almanac: With Essays on Conservation from Round River. New York, NY: Random House.

- Lewis, C. S. 1953. The Abolition of Man. New York: Macmillan.

- Mahmoudi, S., E. Jafari, H. Ali Nasrabadi, and M. Javad Liaghatdar. 2012. “Holistic Education: An Approach for 21 Century.” International Education Studies 5 (3): 178–186. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v5n3p178.

- Manokaran, J. 2015. Chipko Takes Root. Bengaluru: Pratham Books.

- Mathews, F. 2016. “From Biodiversity-Based Conservation to an Ethic of Bio-Proportionality.” Biological Conservation 200:140–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.037.

- Merveldt, N. V. 2018. “Informational Picturebooks.” In The Routledge Companion to Picturebooks, edited by B. Kümmerling-Meibauer, 231–245. New York: Routledge.

- Morten, S., and M. C. Benwell. 2021. “Young people’s Everyday Climate Crisis Activism: New Terrains for Research, Analysis and Action.” Children’s Geographies 19 (3): 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2021.1924360.

- Murphy, E. 2024. “Healing Landscapes and Grieving Eco-Warriors: Climate Activism in Children’s Literature.” Children’s Literature in Education 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-023-09567-3.

- Muthukrishnan, R. 2019. “Using Picture Books to Enhance Ecoliteracy of First-Grade Students.” The International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education 6 (2): 19–41.

- NAAEE. 2022. About EE and Why it Matters. https://naaee.org/about-us/about-ee-and-why-it-matters.

- Nature in Children’s Literature and Culture. “The NatCul Matrix.” https://blogg.hvl.no/nachilit/the-natcul-matrix/.

- Nina, G., L. Guanio-Uluru, B. Oddrun Hallås, S. M. HøHøIsæteræter, A. Nyrnes, and H. Emma Rimmereide. 2023. “Ecocritical Dialogues in Teacher Education.” Environmental Education Research 29 (10): 1430–1442. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2023.2213414.

- Orlikowski, W. J. 2010. “The Sociomateriality of Organisational Life: Considering Technology in Management Research.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34 (1): 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bep058.

- Orr, D. W. 1991. Ecological Literacy: Education and the Transition to a Postmodern World. Albany: Suny Press.

- Oziewicz, M. 2022. “It wasn’t Us: Teaching About Ecocide and the Systemic Causes of Climate Change.” In Literature As a Lens for Climate Change: Using Narratives to Prepare the Next Generation, edited by R. L. Young, 19–51. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Oziewicz, M. 2023. “What Is Climate Literacy?” Climate Literacy in Education 1 (1): 34–38. https://doi.org/10.24926/cle.v1i1.5240.

- Rangan, H. 2000. Of Myths and Movements: Rewriting Chipko into Himalayan History. London: Verso.

- Risser, P. G. 1986. “Address of the Past President: Syracuse New York.” Ecological Literacy Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 67 (4): 264–270. August.

- Røskeland, M. 2018. “Nature and Becoming in a Picturebook About “Things That Are.” In Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures: Nordic Dialogues, edited by N. Goga, L. Guanio-Uluru, B. O. Hallås, and A. Nyrnes, 27–40. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rybak, K. 2023. “Towards a Literature of Actions: Green Informational Picturebooks and Critical Engagement with Fighting Climate Change.” Children’s Literature in Education 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-023-09549-5.

- Salmon, J. 2000. “Are We Building Environmental Literacy?” The Journal of Environmental Education 31 (4): 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958960009598645.

- Samuelsson, I. P., M. Li, and A. Hu. 2019. “Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: A Driver for Quality.” ECNU Review of Education 2 (4): 369–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531119893478.

- Sanders, J. S. 2018. A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Schlosberg, D. 2004. “Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements and Political Theories.” Environmental Politics 13 (3): 517–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000229025.

- Schmidt, C. 2017. “Thrown Together: Incorporating Place and Sustainability into Early Literacy Education.” International Journal of Early Childhood 49 (2): 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-017-0192-6.

- Shah, H. 2008. “Communication and Marginal Sites: The Chipko Movement and the Dominant Paradigm of Development Communication.” Asian Journal of Communication 18 (1): 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292980701823757.

- Sharma, K., and M. Pandya. 2015. Towards a Green School: On Education for Sustainable Development for Elementary Schools. New Delhi: National Council of Educational Research and Training.

- Singh, P. 1994. “Chipko Tree Huggers of the Himalayas.” https://www.sepiaeye.com/pamela-singh-chipko-tree-huggers-of-the-himalayas.

- Soulioti, D. 2022. “Ecocritical Insights: Contemporary Concerns About Forest Ecosystems in a Greek Picturebook.” Children’s Literature in Education 53 (4): 454–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-021-09451-y.

- Srivastava, J. 2015. “Grassroots Environmentalism As Discursive Contestation in India: Narratives from the Chipko and Save the Narmada Movements.” Rivista Degli Studi Orientali 88:131–147.

- Stibbe, A. 2015. Ecolinguistics: Language, Ecology and the Stories We Live By. New York: Routledge.

- Tewari, D. D. 1995. “The Chipko: The Dialectics of Economics and Environment.” Dialectical Anthropology 20 (2): 133–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01298415.

- Tien, Y. F., and H. C. Wu. 2010. “A Study of Environmental Education Content Presented in Highquality Picture Books: Samples Recommended by Taichung County Early Childhood Teachers.” Journal of Environmental Education Research 8 (1): 63–93.

- United Nations. 2020. The Sustainable Development Goals Report (2020). New York: United Nations.

- Walker, C. 2017. “Embodying ‘The Next generation’: Children’s Everyday Environmental Activism in India and England.” Contemporary Social Science 12 (1–2): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2017.1325922.

- Wang, X., D. Palazzo, and M. Carper. 2016. “Ecological Wisdom as an Emerging Field of Scholarly Inquiry in Urban Planning and Design.” Landscape and Urban Planning 155:100–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.05.019.

- Weitzman, L. J., D. Eifler, E. Hokada, and C. Ross. 1972. “Sex-Role Socialization in Picture Books for Preschool Children.” American Journal of Sociology 77 (6): 1125–1150. https://doi.org/10.1086/225261.

- Witt, S. D., and K. P. Kimple. 2008. “‘How Does Your Garden grow?’ Teaching Preschool Children About the Environment.” Early Child Development and Care 178 (1): 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430600601156.