Abstract

Mangrove forest ecosystems are critically threatened in West-Central Africa due to minimal management and policy efforts. This is partly caused by insufficient knowledge about the economic and ecological value of mangrove ecosystems, which provide important ecosystem services, such as fish, flood prevention, erosion prevention, water regulation, and timber products. A strategy to improve mangrove ecosystem management would be to improve public understanding of the ecosystem's values. We studied these drivers on a regional scale, using socio-economic and grey literature and consultations with experts, thereby focusing on the period from 1980 to 2006. Wood harvesting, conversion of mangroves for agriculture, and bio-fuel plantations were important drivers of mangrove forest change. Coastal development is the most important direct driver of mangrove forest change, especially between 2000 and 2006, a period that coincides with large oil discoveries in the region. About 60% of all industries within the region are located near the coast, which is expected to attract about 50 million people by 2025. Future policies should target the risks of declining mangrove ecosystems in West-Central Africa. This requires focusing on adaptive strategies, reviewing existing coastal and marine ecosystem policies, and developing an integrated coastal management strategy for the region.

Introduction

Mangroves are complex inter-tidal forests that thrive at the interface between dry-land and open seas, in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. This ecosystem is the mainstay of enormous biological and abiotic resources (Adams Citation1993; Dame and Kebe Citation2000; Tallec and Kébé Citation2006; Ukwe, Ibe, Nwilo, et al. Citation2006). The coastal zone of West-Central Africa in particular is attracting a variety of people and development initiatives that converge to benefit from a mixture of ecosystem services offered by mangrove ecosystems (Kelleher et al. 1985; Diop Citation1993; Kjerfve et al. Citation1997; Ajonina et al. Citation2008). These services can be grouped into provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural (Millennium Ecosystems Assessment Citation2005), and cumulatively contribute to the socio-economic well-being of coastal communities and local governments in the region. Nowadays, mangroves are increasingly recognized as ecosystems with considerable hydrological and chemical cycling abilities (Hamilton and Snedaker Citation1984; Bosire et al. Citation2005). They also contribute to stabilizing coastlines, protecting coastal communities from tropical storms and surges and in sustaining coastal water resources, agriculture, and fisheries (Dahdouh-Guebas et al. Citation2005; Fatoyinbo et al. Citation2008; UNEP Citation2008).

Despite these recognized benefits, mangroves are largely neglected in national and regional policies in West-Central Africa (CEC Citation1992; Diop Citation1993; FAO Citation2007). Consequently, continuous degradation and deforestation as a result of uncontrolled exploitation and land conversion is taking place on a large scale. As pointed out by Fatoyinbo et al. (Citation2008), mangroves of Africa are rapidly declining, and this trend is likely to continue, as an additional 25% of developing countries' mangroves would be lost by 2025 (Mcleoa and Slam Citation2006). As these mangroves dwindle, the livelihoods and well-being of millions of vulnerable coastal communities and local governments that directly or indirectly depend on its resources are at risk. There is a correlation between mangrove ecological health and its ability to sustain its services (Nagelkerken et al. Citation2001; Mumby et al. Citation2004; Worm et al. Citation2006). Already, this continuous loss of mangroves in the region is causing falling fish catch, property loss, and increase in poverty levels and hence human suffering (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Citation2001, 2007). These impacts will be compounded by the effects of sea level rise as a result of climate change (Ibe and Awosika Citation1991; Ibe Citation1996; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Citation2001; FAO Citation2004). Hence the need to take actions that will proactively reverse these dangerous trends.

To attract actions that will stimulate the sustainability of this ecosystem, it is necessary to identify the drivers of mangrove forest change from a wider perspective (Thai-Eng Citation1998; Voabil et al. Citation1999). Various studies have examined the extent of threats to mangrove forests within countries of the region, for example, Diop (Citation1993), Kjerfve et al. (Citation1997), UNEP (Citation1999), Ajonina and Usongo (Citation2001), Feka and Manzano (Citation2008), and Ajonina et al. (Citation2008). These investigations show that activities that promote the conversion of mangroves forests constitute a valuable baseline for the socio-economic well-being of coastal communities and local governments in the region. However, empirical information on these activities and their implications on mangrove forests from a regional spectrum is disperse and scarce. The objective of this article is to elucidate that economic activities operated within and around mangrove forest ecosystems contribute to the decline of this ecosystem in West-Central Africa. The article aims to promote a sustainable management agenda for this ecosystem that strategically considers these activities, which are essential for the well-being of local people in the region.

Distribution and ecological importance of mangroves in West-Central Africa

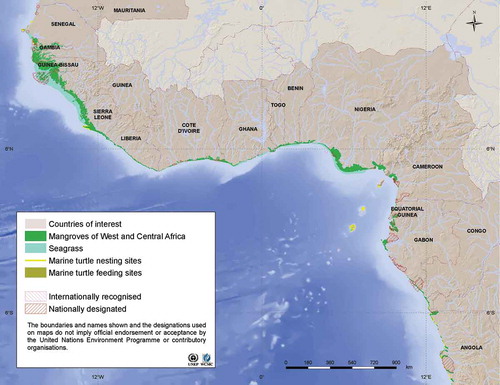

Africa hosts about 19% of the world's mangroves, of which about 20,410 km2 (12% of the world's mangroves) is located in West-Central Africa. These mangroves cover 15% of the 8492 km of the West-Central African coastal zone (UNEP-WCMC Citation2007; UNEP Citation2008) stretching from the west coast of Mauritania through the Gulf of Guinea countries down to Angola (), covering some 19 countries with total population of over 300 million people (). A variety of habitat types heightens this coastline, ranging from sandy desert shores in Mauritania, to deeply indented estuarine and island coasts of Guinea Bissau, to the lagoons of the Gulf of Guinea countries and to the occasional large mudflats and deltas in the Gambia and the Niger Delta, that exemplify the heterogeneity of these habitats. This conglomerate of habitats has instituted favorable conditions that attract and favor the development of biological resources of significant value (Kelleher et al. Citation1985). A strikingly significant part of this environment is the vast array of rivers that flow from the hinterlands into the Atlantic Ocean. The confluences of these rivers with marine waters form suitable conditions for the development of outstanding mangrove vegetation in the region. shows indicative values of mangrove forests area coverage as at 2006, while illustrates areas lost over 1980–2006. These mangroves extend inland as far as 160 km in some countries, especially Gambia and Guinea Bissau (Diop Citation1993).

Figure 2. Status of mangrove forests in West-Central Africa; including mean area change per country (1980–2006). Negative values indicate a gain in mangrove area.

Table 1. Extent, distribution, and status of mangroves in West and Central Africa (1980–2006)

Plant species of varying morphologies characterize mangroves of the region, and are dominated by Rhizophora racemosa species (IUCN Citation2004; FAO Citation2007). There are five indigenous mangrove species belonging to three families, including Rhizophora racemosa, Rhizophora mangle, and Rhizophora harrisonii, the white Avicennia germinans and Laguncularia racemosa. Nypa fruticans is an exotic species introduced in Nigeria from Asia, while Astrotichum aureum and Cornocarpus erectus are associates. There is no significant difference in floral species between neighboring countries, but variations in species numbers that vary (). In addition to the floral species, mangrove forests of the region are a ‘paradise’ for prominent resident and migratory water bird species, marine organisms, and other coastal/terrestrial organisms that use this ecosystem as breeding and feeding ground. These mangroves are extremely valuable because of the high proportion of endemic fauna that use and depend on its resources. Some of the important faunal species found in these ecosystems include the Trichechus senegalensis (West African manatee), globally endangered pygmy hippopotamus (restricted to Liberia and the Niger Delta), the threatened pennant red colobus (restricted to isolated areas in the Niger Delta and Bioko) and the dwarf and slender-snouted crocodile (restricted to the coastal forests of Liberia, Niger Delta, Cameroon, and Angola) (Kelleher et al. 1985). All of these organisms compete with many other generalists, most particularly the endangered loggerhead and leatherback turtles that navigate the entire coast of the region (Dodman et al. Citation2006). In addition, the coastal lagoon regions support a significant number of important biological organisms, some of which are endemic to the region (Kelleher et al. 1985; Dodman et al. Citation2006).

Important drivers of mangrove forest change in West-Central Africa

Coastal fisheries and related activities account for about 200 million jobs globally, and most of these employment opportunities are in developing countries (FAO Citation2004; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Citation2005; ICTSD Citation2006). The coastal populations of West-Central Africa constitute an important fraction of this number, because artisana fishing and associated activities support over 5 million jobs in the region (Tallec and Kébé Citation2006; Bene et al. Citation2007). Fishing accounts for about 3% of the gross domestic product (GDP) of the Gambia, 4% of Ghana, 5% of Mauritania, 5% of Senegal and up to 70% of Benin (UNEP Citation2008). Fishermen of the region practice coastal artisanal fishing in the brackish waters of creeks and estuaries, along the coastal zone. These fishermen operate hand pulled or motorized boats (canoes), in these waters, but occasionally stray into the open seas. The Gulf of Guinea (found in this region) is host to one of the most important up-welling zones in the world. Up-welling significantly promotes fish production (Ukwe, Ibe, et al. 2006; Ukwe, Ibe, Nwilo, et al. Citation2006). Many fishing stakeholders operate bountiful fishing types and activities in this region, and they use varied fishing gear from one country to the other (FAO Citation1994a, Citation2004; Njifonjou and Njock Citation2000). Some of this equipment includes set gill-nets, beach seiners, large meshed drift nets, hooks on long line/hand lines, and various traps such as acadja, common in Benin, and fence-trap (Dame and Kebe Citation2000). The use of this equipment often bears cultural and/or traditional links to a particular community in a given country. However, in some areas traditional equipment has disappeared in order to meet up with competition from new fishing technologies and the declining fish stocks (FAO Citation1994a; Lenselink and Cacaud Citation2005).

There are many fishing villages and/or camps along the West-Central African coastline (Department for International Development of the United Kingdom and Food and Agriculture Organization Citation2005). About 60% of all fish harvested in these rural areas is of artisanal origin (FAO Citation1998; Citation2000). Open drying, dry salting, salting, fermenting, icing, refrigerating, and smoking are the common methods used to preserve this fish (Labarriere et al. Citation1988; FAO Citation1994a). However, fish smoking is the most important and most ubiquitous method for preserving fish in the region. Fish smoking is mostly used to preserve fish because it reduces post harvest losses by complementing the time lapse from the point of catch to the fishing port (Abalagba et al. Citation1996; Akande et al. Citation1996). Preference for this method is further justified by the scarcity of electricity, lack of conservation facilities, and market opportunities for fresh fish in this environmental edge.

There are various types of energy sources used for fish smoking across countries of this region (Satia and Hansen 1984; FAO Citation1994a; Lenselink and Cacaud Citation2005), but fuel wood is the principal source of energy used in all forms of fish smoking. The fuel wood provisioning industry for fish smoking is an important economic sector in this region. Mangrove wood is widely preferred for fish smoking within coastal areas of this region because of its availability, high calorific value, ability to burn under wet conditions, and the quality it imparts to the smoked fish (Oladosu et al. Citation1996). Mangrove wood harvesting intensities vary across countries and it is seasonal and gender determined (Feka et al. Citation2011). These harvesting patterns are further determined by the level of policy implementation and the stewardship of local people (Walters et al. Citation2008). In Mauritania and Benin, mangrove wood is harvested mostly from dead branches by women and children. While in Senegal, the Gambia, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Cameroon wood is mostly harvested from mangrove stands (Diop Citation1993; Kjerfve et al. Citation1997; Adite Citation2002). Mangrove wood harvesting is ubiquitous in the region, and constitutes a significant socio-economic resource to local people in all countries of the region (Diop Citation1993; Kjerfve et al. Citation1997; Ajonina and Usongo Citation2001; Da Silva et al. Citation2005). illustrates the wood harvested from mangrove forests from some countries of the region.

Table 2. Mangrove wood harvested from mangrove forest stands in seven coastal countries of the region

Traditional aquaculture ‘acadja’ is also a cause for mangrove clearing in this region. This activity began at the beginning of past century in Benin. Acadja is the use of mangrove branches in an area about 12–16 m2 to artificially mimic fish habitats, in order to attract fish. It is practiced extensively in countries such as Benin and Ghana and this practice contributes to about 15–30% of the national fish landings (Lalleye Citation2000). On the other hand, modern coastal aquaculture is slowly expanding into the coastal areas of West-Central Africa (World Rainforest Movement (WRM) Citation2004). Shrimp farms operate in a variety of coastal and inland zones in Guinea, Gambia, Sierra Leone (extensive ponds at Makali to the north and Senegal). The Ebrié and Grand-Lahou Lagoons are popular sites where subsistence aquaculture directly contributes to about 20,000 tons of annual fish production in Ivory Coast (Abe et al. 2000). In Nigeria, about 20,500 tons of fish from coastal aquaculture is produced per year. There are prospects of further expansion as companies such as the Amerger (Asian base aquaculture company) finalized a shrimp farm study, with a potential production of 2000 tons per year in 2004 in Gabon, while the Srilankan industrial shrimp farmer, Sulalanka plans to cultivate over 2222 ha of mangrove land from north-west to southeast of Nigeria. This project will generate over 6000 job opportunities in rural areas and produce a minimum of 50,000 tons of the black tiger prawns for the international market, worth over US$ 400 million per year (Alfredo Quarto Personal Communication 2007).

Salt extraction is also driving mangrove forest change, as the extracted salt from sea water is dried using mangrove wood. This activity is popular among local communities of Guinea Bissau and Nigeria (CEC Citation1992). The process of excavation and processing to obtain pure salt from sea water is described in CEC (Citation1992). The vaporization of about 63 kg of salt consumes about 1 m3 of wood. On average, about 47,613 m3 of wood is used annually as energy to produce 30,000 tons of salt in Benin (Convention on Biological Diversity Citation2002). This activity generates an annual revenue of about US$ 185 with a profit margin of 46% per year, per individual. An individual extracting salt under these circumstances deforests about 900–1600 m2 of mangroves annually, depending on available resources. For the levels of salt extraction intensities in other countries of the region see .

Table 3. Frequency distribution indicating the intensity of major anthropogenic activities scooping mangrove forests in West-Central Africaa

Agriculture is the most important economic activity in most non-oil exporting Sub-Saharan African countries. It makes up about 30% of Africa's GDP and up to 50% of the total export value of Africa. About 70% of the continent's workforce depends on agriculture for their livelihoods (OECD Citation1998, Citation2006). With the exception of countries such as Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and Nigeria, coastal countries of West-Central Africa have agriculture-based economies. Most of these countries have developed mechanized, intensive agriculture in coastal areas (FAO 1998). The flat topography of coastal areas, coupled with the warm climatic conditions favor the development of agricultural plantations in these locations by colonialists who sought fields to produce tropical crops for export to Europe (Neba Citation1987). With the departure of the former, agricultural plantations continue to exist on these fields; and cash crops such as rice, oil palm, cashew nuts, Havea brassilensis, and coconuts thrive well in these zones (IUCN Citation2004). The proliferation of plantations of these cash crops, particularly in Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, and Cameroon helps in contributing to meet food self-sufficiency, employment, and financial obligations for local communities and government agencies. The plantations of the Cameroon Development Corporation occupies all available coastal lands in the south-west and Littoral regions of Cameroon and is the second largest employer after the state in Cameroon. Similarly, agricultural activities in the coastal region of Togo engage close to 329,090 people. However, the outcome of these actions has caused the loss of about 78,000 ha of mangroves and other coastal forests. Swap rice cultivation is a promising economic activity that accounts for about 10% of the total rice production in the region. However, this activity has wiped about 214,000 ha of mangrove forests in the region (West Africa Rice Development Authority Citation1983; Fofanah Citation2002).

The potential of wetland conversion to bio-fuel feedstock plantations of jatropha, sugarcane, and oil palm is high in Africa, particularly coastal West-Central Africa (Sielhorst et al. Citation2008). About 1000 ha of mangrove forests are envisaged for palm plantation in the Bakassi peninsula in Cameroon, located in this region. In Ivory Coast, a palm oil company has started the replacement of 6000 ha of the Ehy forest in Tanoé swamps forest, to oil-palm plantation, while industrial groups from Malaysia and South Africa have finalized plans to develop oil-palm plantations covering 300,000–400,000 ha in the mangroves of Benin for feedstock production (Sielhorst et al. Citation2008).

Coastal urbanization

Capital cities such as Dakar, Abidjan, Accra, Lagos, Port Harcourt, Freetown, Douala, Kribi, Libreville, and Cotonou have developed along the coastal zone of West-Central Africa. Some of these cities have emerged at this environmental edge because of favorable economic factors such as transportation, favorable climate type, cheap labor, and available natural resources. This combination has favored the vast expansion and development of approximately 90% of all industries in Senegal and Togo, and 60% of industries in Ghana within or in close range of the coastal zone (Abe et al. 2000). Similarly, the coastal areas of Nigeria and Cameroon are host to 85% and 65% of all industries, respectively (Ibe and Awosika 1991). These industries are attracting an ever-bulging population to this zone, and currently, about 46 million people live in the Gulf of Guinea's narrow coastal fringe, and this number will reach 50 million by 2025 (UNEP Citation1999; Citation2008).

Exploration and exploitation of petroleum and gas

Petroleum production in the region () is about 16.9 billion barrels annually. Petroleum-producing countries in this region own more than 4.5% of proven world oil reserves, distributed between the open sea and the land interface (British Petroleum 2006). In 2005, oil production from within these countries contributed to 5% of total world commercial production. This activity has encouraged significant economic growth in these countries. Moreover, it has spurred financial stimuli that have allowed governments to consider infrastructure improvements and diversification of the national economy. Oil production and its supporting activities contribute to about half the GDP of Angola and 90% of its exports. Increased oil production provided a 12%, 19%, and 17% economic growth in 2004, 2005, and 2006, respectively, in Equatorial Guinea (Mobbs Citation1998; Coakley and Mobbs Citation1999).

Table 4. Petroleum and oil and gas reserves – production by some countries of West-Central Africa

Despite the apparently successful outcomes from this industry, its activities have had disastrous implications for the environment and mangroves in particular. As a result of oil exploitation and/or exploration, oil spills have occurred close to main ports of Abidjan, Lomé, Bata, Kribi, Cap Lopez, Port Gentil, Pointe-Noire, Cabinda, and Luanda (Dodman et al. Citation2006). Over a 20-year period, 1976–1998, about 2,570,000 m3 of oil leaked and/or spilled into the Niger Delta. In addition, about 75% of all gas produced annually in the Niger delta flares, causing serious ecological and physical damage to other resources such as land/soil, water, and mangrove vegetation (Egberonge et al. Citation2006). Oil exploitation operations in Nigeria might have caused the loss of about 2568 ha of mangrove forests from 1980 to 2006 (Diop Citation1993; Ekundayo and Obuekwe Citation2001).

Mangrove management policies

The mangroves of West-Central Africa are essential wetlands, providing a wide range of market and non-market goods to coastal communities. Despite these recognized benefits, mangrove forests remain over-exploited. This is because mangroves are marginalized in national and regional political agendas (Kjerfve et al. Citation1997; Dodman et al. Citation2006; UNEP-WCMC Citation2007). This marginalization is due to the poor weighting of this ecosystem's services, because of the inability to establish a market value to these services (Barbier et al. Citation1997; Barbier and Cox Citation2003). This lack of information to effectively value mangroves is the result of inadequate research interest and limited government concern; indicated by inadequate regulations and poor policy enforcement. For instance, there is no country with conventional mangrove forest policies in the region, as mangrove management is often encapsulated within existing terrestrial forests or marine resources policies. This marginalization reflects in the meager 20% of mangroves protected in all these countries ().

Discussion

Implications of wood harvesting on mangrove forests

All over most coastal tropical developing regions, there are various factors that drive the transformation of mangrove ecosystems (WRM Citation2002). Local coastal communities, corporate institutions, and governments exploit and use resources from these ecosystems for a wide variety of purposes. Similarly, in West-Central Africa, exploitation activities are driving mangrove ecosystem change. However, wood harvesting is the most perverse indirect driver of this change in this region (Dodman et al. 2006; Feka et al. Citation2009; Nfotabong et al. Citation2009). As pointed out in this study, about 50,769 ha of mangroves were lost annually as a result of fuel-wood harvesting from 1980 to 2006 in only seven countries of the region. Moreover, when available wood harvest data from are extrapolated for the period 1980 to 2006, wood off-take from mangrove forests might have cumulatively extirpated about 5 million ha of mangrove forests from 1980 to 2006 in West-Central Africa; assuming there was no growth (). However, when mangrove stands growth is considered, using growth rates of prominent mangrove tree species in the region derived by Ajonina (Citation2008), the net mangrove forest area reduced as a result of wood harvest is about 3 million ha. Most of the harvested wood is used for fish smoking (Satia and Hansen Citation1984; Ajonina and Usongo Citation2001). This quantitatively concords with findings from this study which elucidates that over 90% of mangrove forests were cut annually to sustain fish smoking; in three countries ().

Figure 4. Projected wood harvest from mangrove stands in WCA for seven countries in West-Central Africa.

However, it should be noted that the productivity rate used in the growth extrapolation, in this study, is high compared to other mangrove species and locations of the region. Similarly, the wood piling coefficient used (Feka Citation2005; Ajonina Citation2008) in the analysis is for Cameroon mangroves only. Moreover, methodological insufficiency and duplication of information might have over- and/or under-estimated quantities of wood harvested. These limitations notwithstanding, it is undeniable that the utilization of wood from mangrove forests is a significant factor driving the deforestation of mangroves in West-Central Africa. This increasing rate of wood harvest is the outcome of the dilapidating economic situation and increasing dependence on natural resources among countries of the region, which is driving high dependence on natural resources exploitation (OECD 1998, 2006). However, mangroves have an enormous capacity to recover from disturbances (Zuleiku et al. Citation2003; Bosire et al. Citation2006). Notwithstanding, such reversals are a function of the nature of disturbances, persistence, and availability of reproductive materials such as propagules (Field Citation1997; Harun-or-Rashid et al. Citation2009). In areas where fuel wood exploitation is not excessive and repeated, the ecosystem will successfully regenerate if given due management efforts (Bosire et al. Citation2005; Feka et al. Citation2011).

This study thus makes it clear that about 700,000 ha of mangrove forests might have undergone and/or are in the process of undergoing transformations to rice and/or bio-fuels feedstock plantations from the 1980s to 2006. Although the factors driving this change are serious, their intensities are not evenly distributed among countries of the region (). This conversion of mangroves forests forces the alteration of flora and soils and biodiversity loss hence the probability for ecosystem sedimentation, loss of indigenous people's livelihood support sources, and food insecurity (Koh and Wilcove Citation2008). Despite the current levels of conversions, there is the promise for continuous conversion as Wetland International has established that African wetlands (including mangroves) are seriously at risk of further conversions because of favorable conditions such as cheap land and labor, favorable climate, and fertile sediments from inlands that favor the development of bio-fuel feedstock. Moreover, continuous demand for bio-fuel feedstock from Africa has now out-scaled the entire world market and will reach 47% by 2020 (Smeets and Faaij Citation2004).

Coastal agriculture is thus fast becoming a dominant threat to the sustainability of mangroves in West-Central Africa. The conversion might bring profitable short-term benefits as in the case of Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia that enjoy priority positions among shrimp and bio-fuel feedstock-producing nations in the world (WRM 2002). However, the outcomes from such actions have far-reaching short- to long-term implications to hydrological cycles, food webs, and the overall ecosystem sustainability. Moreover, aquaculture is the greatest single direct threat to mangroves globally (WRM Citation2002; IUCN Citation2004). For these reasons, coastal agriculture needs to be prioritized within poverty reduction plans and coastal strategic development plans in these countries.

Coastal development activities have unequivocally contributed to the striping of mangrove forests in West-Central Africa. The case of Kamsar port in Guinea which caused the loss of about 70,000 ha of mangrove forests and the expansion of the town of Accra, which wiped out up to half of Ghana's mangroves are blatant examples (UNEP-WCMC Citation2007; UNEP Citation2008). One of the consequences of this clearing is the rapid erosion of the coastal zone. Coastal erosion is now a serious problem in the region, threatening the remaining mangroves and destabilizing the coastal zone. It contributes to shoreline retreat by diminishing the amount of fluvial sediment input to the coastline. Coastal retreats of up to 30 m per year are reported in some countries of the region (Ibe Citation1996; Abe et al. Citation2000; Adite Citation2002). In the Niger Delta, about 400 ha of mangrove forests are lost annually as a result of erosion (Hinrichsen Citation2007).

In West-Central Africa, as is the case with most Sub-Saharan countries, most of these development activities happen outside a strategic development plans. This circumstance, coupled with the poor weighing of mangrove services creates prospects for uncontrolled urbanization, which is a leading cause of mangrove forest change (Hamilton and Snedaker Citation1984; Barbier and Cox Citation2003). Petroleum is extremely dangerous to the ecology of mangroves because it causes acute chronic and immediate effects with a resident time of up to 10 years. This may cause reproductive failures in both plants and animals and drastic decreases in the population size of other resident organisms (Kjerfve et al. Citation1997; Ekundayo and Obuekwe Citation2001). In the Niger Delta, mangroves are negatively sensitive to the least levels of oils (Hindah et al. Citation2007). Petroleum exploration and pipeline installation are partially responsible for the loss of about 60% of the Nigerian mangroves, mainly in the Niger Delta. Hence, development activities have contributed to causing fundamental changes in mangrove forests, extent in the region over the period of 1980–2006. However, empirical data on mangrove deforestation as a result of development activities are insufficient for the region, and it will be necessary to investigate further, the direct contribution of this driver to any change in this ecosystem.

Implications of lack of appropriate policies and responsibility on mangrove forests

A review of existing policies regulating the exploitation and use of mangroves and other coastal resources in West-Central Africa reveals the existence of a plethora of sector-based policies that appear to be conflicting, outdated, and deficient to conserve mangroves in the region. These policy deficiencies, coupled with the devolved roles among institutions, suggest that there is a multitude of ministries and/or agencies supposedly managing this ecosystem in one particular country (Macintosh and Ashton Citation2003).

This lack of tied responsibilities among and between institutions speculates the existence of conflict of interest between institutions and local people involved in the resource-use process. Against these policy deficiencies, it will be a significant value for countries in the region to initiate research on mangrove policies development. However, relevant documents such as the Mangrove Code of Conduct and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands can be used as base documents in the region.

Prospects for sustainable management of mangrove forests in the region

Mangroves of West-Central Africa are suffering from a multitude of dilemmas. These threats range from poor policies, which are perpetuating the ‘tragedy of the commons,’ in the region to poor governance. Most institutions working on mangroves and coastal ecosystems management in the region operate as islands, coupled with the massive lack of national and regional corporation. Moreover, most regional initiatives originate from outside the continent or from multilateral institutions. These circumstances make it potentially difficult for the overseas development agencies to direct its resources for the effective management of this ecosystem. Moreover, it creates avenues for projects' duplication and waste of scarce resources.

Mangroves like other natural resources require supportive and adaptive policies, which are adequately enforced. These policies have to be accompanied by initiatives such as plans to facilitate conflict resolution between stakeholders and encourage consultations with administrative officials (Campredon and Cuq Citation2001; Mitsch Citation2005). However, a major challenge with developing these policies lies in bringing the highly heterogeneous mangrove stakeholders to a consensus. There are also reports of the lack of adequate capacity and financial resources to manage this system in the region (Larcerda Citation2001; AMN Citation2009).

At the regional level, these challenges could be overcome by developing fundamental adaptive sustainable strategies, within a regional management entity such as an Integrated Coastal Management system. Integrated Coastal Management is an ongoing, iterative, adaptive, and consensus-building process comprised of a number of related tasks, all of which must be carried out to obtain a set of goals for the sustainable use of the coastal area (Bower et al. Citation1994). This approach builds on the assumption that it involves intersectoral integration. The government initiates and coordinates the implementation of this initiative, but it usually involves all stakeholders. Such initiatives successfully contributed to coastal ecosystems revival in Tanzania and South-East Asia. The implementation of this strategy in these areas has contributed to reduce pressure on coastal resources. In addition, this approach has helped to develop practical resource management plans (Thai-Eng Citation1998; Voabil et al. Citation1999). The values of this approach lie in its ability to develop adaptive sustainable strategies, which consider policy reforms, awareness raising, capacity development, the institutionalization of community-based organizations to monitor these drivers and research for development.

Policies relating to the management of mangroves for the region should reflect the importance of the active national- and local-level participation in the utilization of mangrove resources as a livelihood strategy. Moreover, considering the transnational nature of resources dependent on this system, regional scales of reference should take precedence over national borders and the long-term consequences of development should be considered. This approach will improve the outputs of existing projects/programs through regional corporation, information sharing, and collaborative efforts in ensuring effective mangrove management. This strategy does not intend to ignore existing projects and/or mangrove conservation projects in the region, as there are many ingenious mangrove management initiatives in the region; however, the approaches currently used are unpredictable; without a clear position of how such strategies should be driven.

At the national and local levels, many government institutions, local communities, and NGOs have initiated many mangrove reforestation efforts. However, such efforts are far more progressive in the East and West than the Central African sub-region (AMN Citation2009). While there is growing enthusiasm for the restoration of this system, overall success rates remain extremely low in the region (AMN Citation2009). Some of the major drawbacks for these increasing fruitless initiatives emanate from the poor understanding of the socio-economic values, physicochemical and regenerative properties of mangroves, and how anthropogenic activities are affecting this ecosystem in the region (Hamilton and Snedaker 1984; FAO Citation1994b; Larcerda Citation2001). Specific field problems and constraints encountered identified by restorers include difficulty of access, losses from various attacks at planting especially from crabs, and the difficulty of working local communities during peak agricultural activities.

Considering that local communities extensively extract mangrove wood for fuel, there is the need to develop alternative energy sources. This could be effective through the promotion of fast growing (fuel-wood plantation) trees on land. Moreover, in order to reduce existing pressure on mangrove resources, while sustaining the livelihoods of the local population, it is essential to develop comparative alternative sources of income for mangrove resources such as aquaculture, poultry, and livestock development activities. All of these ideas could only be materialized through the development of local natural resources management institutions or enhancing the existing ones, initiating a base for participatory mangrove resources conservation where the organizational, operational, and management capacities needs will be developed and/or enhanced.

Furthermore, to ensure the effective and efficient use of resources, there is the need to develop a monitoring and evaluation mechanism for plantations and other management efforts to ensure post-project sustainability. This could take the form of regular monitoring and research activities by the universities with far-reaching recommendations to enhance their development. As pointed out earlier in this article, most countries in the region do not have any mangrove-specific policies. Hence, it is imperative that mangrove plantation development policies be crafted as part of the general national policy framework for mangroves or wetlands. This implies that there is a need to promote the development of people-centered climate-sensitive mangrove policies which should include conservation in mangrove and marine reserves and restoration of degraded mangrove areas through re-planting.

Conclusions

This study elucidates that mangrove ecosystems are veritable supermarkets, housing and provisioning various goods and services to millions of local people and other adjoining ecosystems that depend on them for sustenance. They are also a promising source of income for the functioning of local economies, governments, and corporate institutions in West-Central Africa. Paradoxically, these very activities are undermining the existence of these ecosystems, as they have cumulatively scooped about 700,000 ha of mangrove forests from the region over a 25 year period from 1980.

Urbanization and related activities are key factors in this change, but regional information on urban development and mangrove deforestation is still scarce to make concrete conclusions in this region. The lack of adequate and enforceable policies for the management of mangroves has exacerbated the loss of mangroves in the region. Mangroves of the region are suffering from the ‘tragedy of the commons.’ It is probable, as shown in , that the severity of threats afflicting mangroves in the region is a reflection of the economic situation of these countries as more economically viable countries such as Angola and Gabon have relatively smaller mangrove deforestation rates. Therefore, the sustainable management of mangroves in the region cannot be achieved in isolation of economic development for the benefit of the local people.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the United Nations Environmental Programme – World Conservation Monitoring Centre's Chevening scholarship programme. We are grateful to all internal and external experts who supported the development of this article, most particularly Edmunds McManus who directed the initial stages of this work, Liesbeth Renders and Emily Cochran for important comments on early drafts, Tiago Estrada and Corinna Ravilious for helping with the map. We also want to appreciate the valuable contributions of Alfredo Da Silva of IUCN Guinea Bissau, and MPO Dore of the Ministry of Forests Nigeria.

Notes

References

- [AMN] African Mangrove Network . 2009 . A decade of mangrove reforestation in Africa (1999–2009): Serie 1: an assessment in five West African Countries: Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria and Senegal/Une décennie de reboisement de mangrove en Afrique: Serie 1: Evaluations dans cinq pays en Afrique de l'Ouest: Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria and Senegal , Dakar (Senegal): African Mangrove Network/Réseau Africain pour la conservation de la Mangrove .

- Abalagba , OJ , Aliu , BS , Okonji , VA , Eboko , FY and Igene , JO. 1996 . A comparative study of the economy of four types of smoking kilns used in Nigeria. Expert consultations on fish smoking technology in Africa report no. 574 , 67 – 69 . Rome , , Italy : Food and Agriculture Organization .

- Abe , J , Kouassi , M , Ibo , J , N'guessan , N , Kouadio , A , N'goran , N and Kaba , N. Cote d'Ivoire coastal zone phase 1: integrated environmental problem analysis . Global Environment Facility, MSP Sub-Saharan Africa Project (GF/6010–0016) . 2000 .

- Adams , WM. 1993 . Indigenous use of wetlands and sustainable development in West Africa . Geogr J , 159 ( 2 ) : 209 – 218 .

- Adite A. 2002. The mangrove fishes in the Benin estuarine system (Benin, West Africa): diversity, degradation and management implications [Internet]. [cited 2007 Jan 20]. http://www.oceandocs.net/handle/1834/455. (http://www.oceandocs.net/handle/1834/455.)

- Ajonina , GN. 2008 . Inventory and modeling forest stand dynamics following different levels of wood exploitation pressures in the Douala-Edea Atlantic coast of Cameroon, Central Africa [PhD thesis] , Germany : University of Freiburg . Freiburg im Breisgau

- Ajonina , GN , Diamé , E and Kairo , JK. 2008 . Current status and conservation of mangroves in Africa: an overview , World Rainforest Movement, Bulletin 133 .

- Ajonina , GN and Usongo , L. 2001 . Preliminary quantitative impact assessment of wood extraction on the mangroves of Douala – Edea Forest Reserve, Cameroon . Trop Biodiv , 7 ( 2–3 ) : 137 – 149 .

- Akande , GR , Oladuso , OH and Tobor , JG. 1996 . “ A comparative technical and economic appraisal of fish smoking: two traditional ovens and a new improve magbon-Alande oven ” . In Expert consultations on fish smoking technology in Africa report no. 574 , 70 – 75 . Rome , , Italy : Food and Agriculture Organization .

- Barbier , EB , Acreman , MC and Knowler , D. 1997 . Economic valuation of wetlands: a guide for policy makers and planners , Gland , Switzerland : Ramsar Convention Bureau .

- Barbier , EB and Cox , K. 2003 . Does economic development lead to mangrove loss? Across country analysis Contemp . Econ Pol , 21 ( 4 ) : 418 – 432 .

- Bosire , JO , Dahdouh-Guebas , F , Kairo , JG , Wartel , S , Kazungu , J and Koedam , N. 2006 . Success rates and recruited tree species and their contribution to the structural development of reforested mangrove stands . Mar Ecol Prog Ser , 325 : 85 – 91 .

- Bosire , JO , Kazungu , J , Koedam , N and Dahdouh-Guebas , F. 2005 . Predation on propagules regulates regeneration in a high-density reforested mangrove plantation . Mar Ecol Prog Ser , 299 : 149 – 155 .

- Bower , BT , Ehler , CN and Basta , DJ . 1994 . A framework for planning for integrated education in the context of changing relationships with the state . Silver Spring (MD): NOAA/NOS Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment ,

- Béné , C , Macfadyen , G and Allison , EH. 2007 . “ Increasing the contribution of small-scale fisheries to poverty alleviation and food security ” . In FAO Fisheries Technical Paper No. 481 , Rome , , Italy : Food and Agriculture Organization .

- British Petroleum . 2006 . Statistical review of world energy, 2006 , London , , UK : BP P.L.C .

- Cameroon Wildlife Conservation Society . 2001 . Activity report, Douala-Edea forest project for 2000. Mounko (Cameroon) ,

- Campredon , P and Cuq , F. 2001 . Artisanal fishing and coastal conservation in West Africa . J Coast Conserv , 7 ( 1 ) : 91 – 100 .

- Coakley GJ and Mobbs PM. 1999. The mineral industries of Africa. In: U.S. geological survey mineral year book [Internet]. [cited 2007 May]. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/country/africa99.pdf. (http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/country/africa99.pdf.)

- [CEC] Commission of the European Communities . 1992 . “ Commission of the European Communities, Directorate-General for Development ” . In Mangroves of Africa and Madagascar , Brussels , Luxembourg : Office for Official Publications of the European Communities .

- Convention on Biological Diversity. 2002. Benin ministry of environment, habitat and urban planning: national biodiversity strategy action plan Cotonou, Benin [Internet]. [cited 2009 Mar 7]. http://bch-cbd.naturalsciences.be/benin/implementation/documents/strategie/strat_brute.pdf. (http://bch-cbd.naturalsciences.be/benin/implementation/documents/strategie/strat_brute.pdf.)

- Dahdouh-Guebas , F , Jayatisse , LP , Di Nitto , D , Bosire , JO , Lo Seen , D and Koedam , N. 2005 . How effective were mangroves as a defense against the recent tsunami? . Curr Bio , 15 ( 12 ) : 443 – 447 .

- Dame , M and Kebe , M. 2000 . Review sectorielle de la peche au Senegale: aspets socio-economiques , Dakar , Senegal : Ministere de L'agriculture, institut Senegalaise de recherches agricoles .

- Da Silva , SA , da Silva , CS and Biai , J. 2005 . Contribution de La Guinee-Bissau a L'élaboration d'une Charte Sous-Regionale Pour Une Gestion Durable des Ressources de Mangroves , Guinea Bissau : IUCN/IBAP .

- Department for International Development of the United Kingdom, Food and Agriculture Organization . 2005 . Reducing fisher folk vulnerability leads to sustainable fisheries: policies to support livelihoods and resource management: a series of policy briefs on development issues , Rome , , Italy : Department of International Development of the United Kingdom, Food and Agriculture Organization .

- Din , N , Saenger , P , Priso , RJ , Siegfried , DD and Basco , F. 2008 . Logging activities in mangrove forests: a case study from Douala, Cameroon . Afr J Enviorn Sci Tech , 2 ( 2 ) : 22 – 30 .

- Diop , S. , ed. 1993 . “ Conservation and sustainable utilisation of mangrove forests in Latin America and Africa Regions ” . In Okinawa (Japan): ISME. Part II Africa ISME/UNESCO Project Mangrove Ecosystems Technical Reports 3

- Dodman , T , Diop , MD , Mokoko , IJ and Ndiaye , A. , eds. 2006 . Priority conservation actions for coastal wetlands of the Gulf of Guinea: results from an eco-regional workshop; 2005 Apr 19–22; Pointe-Noire, Congo , Dakar , Senegal : Wetlands International .

- Egberonge , FOA , Nwilo , PC and Baddejo , OT. Oil spills disasters monitoring along Nigerian coastline . 5th FIG regional conference; . Accra, Ghana Accra , Ghana . 2006 Mar 8–11 . FIG .

- Ekundayo , EO and Obuekwe , CO. 2001 . Effects of an oil spill on soil physico-chemical properties of a spill site in a typic udipsamment of the Niger delta basin of Nigeria . Environ Manag Assess , 60 ( 2 ) : 235 – 249 .

- Field , C. 1997 . The restoration of mangrove ecosystems . International newsletter of coastal management, Intercoast. Special Edition No. 1. Narragansett (RI): Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island ,

- [FAO] Food and Agriculture Organization . 1994a . Utilization of Bonga (Ethmalosa fimbriata) in West Africa. Fisheries Circular No. 870 , Rome , , Italy : Food and Agriculture Organization .

- [FAO] Food and Agriculture Organization . 1994b . Mangrove forest management guidelines , Rome , , Italy : Food and Agriculture Organization . Forestry Paper No. 117

- [FAO] Food and Agriculture Organization . 1998 . Integrated coastal area management and agriculture, forestry and fisheries , Rome , , Italy : Food and Agriculture Organization .

- [FAO] Food and Agriculture Organization . 2000 . Demographic change in coastal fishing communities and its implications for the coastal environment: FAO Fisheries Technical Paper No. 403 , Rome , , Italy : Food and Agriculture Organization .

- [FAO] Food and Agriculture Organization . 2004 . The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. Rome (Italy): United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization ,

- [FAO] Food and Agriculture Organization . 2007 . The world's mangroves 1980–2005 , Rome , , Italy : Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations . Forestry Paper No. 153

- Fatoyinbo , TE , Simard , M , Washington-Allen , RA and Shugart , HH. 2008 . Landscape-scale extent, height, biomass, and carbon estimation of Mozambique's mangrove forests with Landsat ETM and Shuttle Radar Topography Mission elevation data . J Geophy Res , 113 ( g2 ) : G02S06

- Feka , NZ. 2005 . Perspectives for the sustainable management of mangrove stands in the Douala-Edea wildlife reserve, Cameroon [M.Sc. thesis] , Buea , Cameroon : University of Buea .

- Feka , NZ , Chuyong , GB and Ajonina , GN . 2009 . Sustainable utilization of mangroves using improved fish smoking systems: a management perspective from the Douala-Edea wildlife reserve, Cameroon . Trop Conserv Sci , 4 : 400 – 419 .

- Feka , NZ and Manzano , MG. 2008 . The implications of wood exploitation for fish smoking on mangrove ecosystem conservation in the South West Province, Cameroon . Trop Conserv Sci , 1 ( 3 ) : 222 – 235 .

- Feka , NZ , Manzano , MG and Dahdouh–Guebas , F. 2011 . The effects of different genderharvesting practices on mangrove ecology and conservation in Cameroon . Int J Biodivers Conserv Ecosyst. Serv Manag , doi: 10.1080/21513732.2011.606429

- Fofanah , AS. 2002 . Proceedings of a One-day Inaugural Seminar on Wetlands for Members of The National Wetlands Committee – Sierra Leone. Freetown (Sierra Leone): The National Wetlands Committee ,

- Hamilton , LS and Snedaker , SC. , eds. 1984 . Handbook for mangrove area management , Gland , , Switzerland : UNEP/East West Centre Environment and Policy Institute . Honolulu (HI)

- Harun-or-Rashid , S , Biswas , RS , Bocker , R and Kruse , M. 2009 . Mangrove community recovery potential after catastrophic disturbances in Bangladesh . For Ecol Manag , 257 : 923 – 930 .

- Hindah , AC , Braide , A , Makiri , J and Onokurhefe , J. 2007 . Effect of crude oil on the development of mangrove (Rhizophora mangle L.) seedlings from Niger Delta, Nigeria . Revista Científica UDO Agrícola , 7 ( 1 ) : 181 – 194 .

- Hinrichsen D. 2007. Ocean planet in decline [Internet]. Peopleandplanet.net; 25 Jan. [cited 2007 Jun 1]. http://www.peopleandplanet.net/doc.php?id=429andsection=6. (http://www.peopleandplanet.net/doc.php?id=429andsection=6.)

- Ibe , AC. 1996 . “ The coastal zone and oceanic problems of Sub-Saharan Africa ” . In Economic social and environmental change in Sub-Saharan Africa: sustaining the future. Economic, social, and environmental change in Sub-Saharan Africa , Edited by: Benneh , J , Morgan , WB and Uitto , JI . Tokyo , , Japan : United Nations University .

- Ibe , AC and Awosika , LF . 1991 . “ Sea level rise impact on African coastal zones ” . In A change in the weather: African perspectives on climate change , Edited by: Omide , SH and Juma , C . 105 – 112 . Nairobi , , Kenya : African Centre for Technology .

- [ICTSD] International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development . 2006 . Fisheries, international trade and sustainable development: policy discussion paper International Trade and Sustainable Development natural resources, international trade and sustainable development series: International centre for development and trade , Geneva , , Switzerland : International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development .

- [IPCC] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change . 2001 . Special report on the regional impacts of climate changes an assessment of vulnerability . Cambridge (UK): University of Cambridge ,

- [IPCC] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2007. Mitigation of climate change, working group III fourth assessment report, intergovernmental panel on climate change [Internet]. [cited 2010 Feb 25]. http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/wg3/ar4-wg3-chapter1.pdf. (http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/wg3/ar4-wg3-chapter1.pdf.)

- [IUCN] International Union for Conservation of Nature . 2004 . Programme de L'union International pour la Nature de Guinée-Bissau 2005–2008: Planification Stratégique 2 , Bissau , , Guinea Bissau : IUCN .

- Kelleher , G , Bleakley , C and Wells , C. 1985 . Global representative systems of marine protected areas , Washington , DC : World Bank .

- Lacerda LD , Kjerfve B and Diop , SH , eds. 1997 . Mangrove ecosystems studies in Latin America and Africa , Paris , , France : UNESCO .

- Koh , LP and Wilcove , DS . 2008 . Is oil palm agriculture really destroying tropical biodiversity? . Conserv Lett , 1 ( 2 ) : 60 – 64 .

- Labarriere , JL , Kouako , KL and Bouberi , L . 1988 . Le Four type “Aby” Une amelioration des techniques traditionnelles du fummages du poison FAO, Expert Consultations on Fish Smoking Technology in Africa , 78 – 85 . Rome , , Italy : FAO . Report No. 400

- Lalleye , P . Acadja fisheries enhancement systems in Benin: their productivity and environmental impacts . Biodiversity and sustainable use of fish in coastal zones. ICLARM conference proceedings. Cotonou (Benin): Universite Nationale du Benin. p. 63 . Edited by: Abban , EK , Casal , CMV , Falk , TM and Pullin , RSV . pp. 51 – 52 .

- Larcerda , DL. 2001 . Mangroves functions and management , Berlin , , Germany : Springer .

- Lenselink , N and Cacaud , P . 2005 . Participation in fishery management for improved livelihoods of artisanal fisheries communities of West Africa , Rome , , Italy : FAO. Fishery technology “technical project promotion of coastal fisheries management” FAO Rome GCP/INT/735/UK .

- Macintosh , JD and Ashton , CE . 2003 . The sustainable management of mangrove ecosystems . Accra (Ghana): Centre for African Wetlands, University of Ghana. African Regional Workshop Report ,

- Mcleoa , E and Slam , RV. 2006 . Managing mangroves for resilience to climate change , Gland , , Switzerland : International Union for Nature .

- [MA] Millennium Ecosystem Assessments . 2005 . Ecosystems and human well-being: current state and trends , Washington , DC : Island Press .

- Mitsch , WJ. 2005 . Wetland creation, restoration, and conservation: a wetland invitational at the Olentangy River Wetland Research Park . Ecol Eng , 24 ( 5 ) : 243 – 251 .

- Mobbs PM. 1998. The mineral industry of Equatorial Guinea– 1998. US geological survey Mineral yearbook 16.1 [Internet]. [cited 2007 May]. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/country/1998/eguniea98.pdf (http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/country/1998/eguniea98.pdf)

- Mumby , JP , Edwards , AJ , Arias-González , EJ , Lindeman , K , Blackwell , JPG , Gall , A , Gorczynska , MI , Harborne , AR , Pescod , CL Renken , H . 2004 . Mangroves enhance the biomass of coral reef fish communities in the Caribbean . Nature , 427 : 533 – 536 .

- Nagelkerken , I , Kleijnen , S , Klop , T , Van den Brand , RACJ , Cocheret de la Morinière , E and Van der Velde , G. 2001 . Dependence of Caribbean reef fishes on mangroves and seagrass beds as nursery habitats: a comparison of fish faunas between bays with and without mangroves/seagrass beds . Mar Ecol Prog Ser , 214 : 225 – 235 .

- Neba , AS. 1987 . Modern geography of the Republic of Cameroon , 2nd , London , , UK : Longman .

- Nfotabong , AA , Din , N , Longonje , SN , Koedam , N and Dahdouh-Guebas , F. 2009 . Commercial activities and subsistence utilization of mangrove forests around the Wouri estuary and the Douala-Edea reserve (Cameroon) . J Ethnobio Ethnomed , 5 : 35 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-35

- Njifonjou , O and Njock , JC. 2000 . “ African Fisheries: Major trends and diagnostic of the 20th century ” . In microbehavior and Macroresults: proceedings of the tenth biennial conference of the international Institute of Fisheries Economics and Trade Presentations , Galicia , , Spain : IIFET .

- Oladosu , OK , Adande , GR and Tobor , JG . 1996 . “ Technology needs assessment and technology assessment in the conceptualisation and design of Magbon-Alande – Fish smoking – drying equipment in Nionr ” . In Expert consultations on fish smoking technology in Africa. Rome (Italy): FAO. Report No. 574 76 – 80 .

- [OECD] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . 1998 . West Africa long time perspective Study preparing for the future: a vision of West Africa in the year 2020 , Paris , , France : OECD .

- [OECD] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . 2006 . promoting pro-poor growth: agriculture , Paris , , France : OECD .

- Samoura , K and Diallo , L. 2003 . Environmental issues associated with the main sectors of energy production in Guinea. AJEAM-RAGEE , 5 ( 1 ) : 28 – 38 .

- Satia , PB and Hansen , LS. 1984 . Sustainability of development and management actions in two-community fishery center in the Gambia , Cotonou , , Benin : IDAF. Project Technical Report IDAF/WP/57 .

- Sielhorst , S , Molenaar , JM and Offermans , D. 2008 . Biofuels in Africa: an assessment of risks and benefits for African wetlands , Wageningen , , the Netherlands : Wetlands International .

- Smeets , E and Faaij , A. Iris LewandowskiA quickscan of global bio-energy potentials to 2050: an analysis of the regional availability of biomass resources for export in relation to the underlying factors . Utrecht (the Netherlands): Utrecht Copernicus Institute. Report NWS-E-2004-109 . 2004 .

- Tallec , F and Kébé , M. 2006 . Evaluation of the contribution of the fisheries sector to the national economy of West and Central African countries. Analysis and summary of the studies conducted in 14 countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, São Tomé & Principe and Senegal . The Sustainable Fisheries Livelihoods Programme (SFLP), Feb 2006; Dakar, Senegal ,

- Thai-Eng , C. 1998 . Lessons learned from practicing integrated coastal management in Southeast Asia . Ambio , 27 ( 8 ) : 599 – 610 .

- [UNEP] United Nations Environment Programme . 1999 . Overview of land-based sources and activities affecting the marine, coastal and associated freshwater environment in the West and Central African Region , Nairobi , , Kenya : United Nations Environment Programme. UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No. 171 .

- [UNEP] United Nations Environment Programme . 2008 . “ Africa: atlas of our changing environment ” . In Division of early warning and assessment , Nairobi , , Kenya : United Nations Environment Programme .

- UNEP-WCMC . 2007 . Mangroves of Western and Central Africa , Cambridge , , UK : United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Regional Seas Programme/UNEP – World Conservation Monitoring Centre .

- Ukwe , CN , Ibe , AC and Kenneth Sherman , K. 2006 . A sixteen-country mobilization for sustainable fisheries in the Guinea Current Large Marine Ecosystem . Ocea Cotl Manag , 49 ( 7–8 ) : 385 – 412 .

- Ukwe , CN , Ibe , AC , Nwilo , PC and Huidobro , PA. 2006 . Contributing to WSSD targets on oceans and coasts on West and Central Africa the Guinea large Marine ecosystem project . Int J Oceans Oceanogr , 6 ( 1 ) : 21 – 44 .

- Voabil , C , Engdahl , S and Banze , J. 1999 . Coastal zone management in Eastern Africa has taken a new approach . Ambio , 27 ( 8 ) : 776 – 778 .

- Walters , BB , Ronnback , P , Kovacs , JM , Crona , B , Hussien , SA , Badola , R , Primavera , JH , Babier , E and Dahdouh-Guebas , F. 2008 . Ethnobiology, socio-economic and management of mangrove forests: a review . Aquatic Botany , 89 ( 2 ) : 220 – 236 .

- [WARDA] West African Rice Development Authority . 1983 . Regional mangrove swamp rice research station. Quinquennial Review Provisional Report , Rokupr Freetown , Sierra Leone : WARDA .

- [WRM] World Rainforest Movement. 2002. Mangroves livelihoods vs corporate profits International Secretariat Maldonado 1858, Montevideo, Uruguay web site [Internet]. [cited 2006 Oct 2] http://www.wrm.org.uy. (http://www.wrm.org.uy.)

- [WRM] World Rainforest Movement. 2004. African mangroves to Feed shrimp aquaculture [Internet]. WRM Bul. No. 84 [cited 2007 Jul 24]. www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/. (http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/.)

- Worm , B , Barbier , BE , Beaumont , N , Duff , E , Folke , C , Halpern , BS , Jackson , J , Heike , K , Micheli , L Stephen , R . 2006 . Impacts of biodiversity loss on ocean ecosystem services . Science , 5800 : 787 – 790 .

- Zuleiku , SP , Ewel , KC and Putz , EF. 2003 . Gap formation and forest regeneration in a Micronesian mangrove forest . J Trop Ecol , 19 : 143 – 153 .