Abstract

In Bangladesh, many forestry projects have been launched with the objective of involving local people in managing forest resources. However, only a few of them have been sustained. In a reaction, the Forest Department (FD) of Bangladesh initiated a project in the Madhupur Sal forest area to protect forests and improve the livelihoods of forest-dependent people in a sustainable way. This study analysed the nature and extent of peoples' participation in Madhupur projects, and evaluated the project's impacts on the livelihoods of participating people through empirical data. The result revealed that capacity building of encroachers and forest-dependent families were the basic achievements of this project. Natural assets, social relationships, and the utilization of human capital through alternative livelihood strategies have provided security and improved livelihood assets of participants. All participants were appointed as paid community forest workers, received incentives, and established a good relationship with the FD, which dismissed participants' forest offences and mobilized their participation. Moreover, protection of encroacher intervention in Sal forests and substantial re-vegetation went hand-in-hand in a synergistic way that made the project initially successful, but community empowerment issues will need more attention from the FD to ensure the sustainability of the project.

Introduction

Forests offer numerous benefits to local people and adjacent communities, which have been appreciated by international and national authorities (Oksanen et al. Citation2003; Laws et al. Citation2004; Shackleton et al. Citation2007). Forests provide ecosystem services that serve as source of employment, cultural and aesthetic uses, subsistence uses, and direct or indirect income. Nonetheless, in many cases, access to natural resources is neither uniform nor equitable within and between communities (Shackleton et al. Citation2007). Usually, forests are located in rural and remote areas. Such areas are relatively underdeveloped regarding infrastructure, market, government services, jobs, and health facilities. Therefore, local communities living in and around the forest areas have been facing high levels of poverty with limited livelihood opportunities (Wunder Citation2001; Sunderlin et al. Citation2005; Shackleton et al. Citation2007). Thus, it is a huge challenge for the state to uphold the livelihoods of forest-dependent people or to give them alternative options so that their forest dependency might be reduced. Still, use of forest resources has offered alternative sources of livelihoods (either cash, direct use, or indirect use values) to the forest-dependent people; hence, such sustainable use implies an opportunity to integrate both conservation and development objectives (Shackleton Citation2001; Sunderlin et al. Citation2005, 2007). Efforts to combine both of these objectives have been made by international agencies and the national governments of South Asian countries through their revised forest policies (e.g. Revised Forestry Sector Policy 2000 in Nepal). Forestry has consistently been an important economic activity to the forest-dependent people of South Asia.

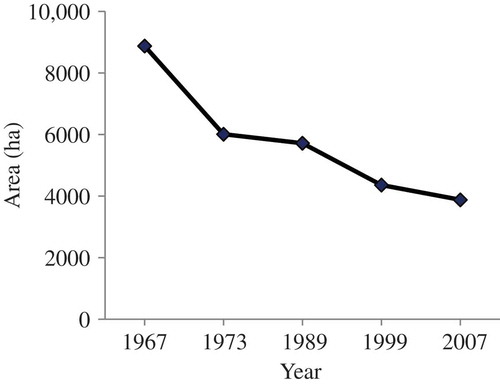

In Bangladesh, Sal forests cover an area of about 0.12 million ha (FD Citation2012), which is distributed over the relatively drier central and northwestern parts of the country (Alam et al. Citation2008). Compared to other forests of Bangladesh, the plain land Sal forests are considered to be of more environmental and economic importance (Safa Citation2004; Alam et al. Citation2008). In addition, they are surrounded by a high-density population, including ethnic minorities. The ethnic minorities have a long history of dependency on the Sal forests, and several social factors have caused the Sal forests to be exploited at an alarming rate, bringing them close to extinction (Alam et al. Citation2008). It was found that the Sal forest cover was severely depleted. In recent statistics, it was found that only 29.8% of the total Madhupur Sal forest (major Sal forest of Bangladesh) area remains (Alam et al. Citation2008; NSP Citation2008) (). It was also noted that illegal logging and forestland conversions were the main causes of Sal forest destruction in Bangladesh (Salam and Noguchi Citation1998; Ahmed Citation2008; Islam and Sato Citation2012b).

The concerned authority of the Bangladesh Sal forests, namely the Forest Department (FD), has been trying to implement different management approaches since 1961–1962 (FD Citation2012). The FD identified a shortage of funds and a lack of proper management plans as reasons for the failure of previous projects (Nath and Inoue Citation2008). Even the latest forest policy of Bangladesh (in 1994) does not address realistic issues such as land tenure, benefit sharing, market process, and inter-coordination of different government institutions, but indicates only a generalized direction (Khan and Begum Citation1997; Ahmed Citation2008). The FD had realized that to meet both conservation and development goals, there is no other alternative than to include local people in forest management and protection (Muhammed et al. Citation2011). Accordingly, the local forest office identified the real causes of Sal forest destruction, and they found encroachers (tree plunderers) among the main forest-dependent families in the Madhupur Sal forest area (Islam and Sato Citation2012b). The basic idea of the FD was to build the capacity of forest-dependent people and ensure their participation in forest management activities. In light of this, the FD had provided an alternative livelihood opportunity to forest-dependent people as a part of a rehabilitation process. All of these holistic ideas were implemented in the Madhupur Sal forest area through a 2009 forestry project: ‘Re-vegetation of Madhupur Forests through Rehabilitation of Forest Dependent Local and Ethnic Communities’ (hereinafter the ‘RMF project’). As per previous project experience, peoples' participation in forest conservation and protection is a big challenge for the FD (Islam et al. Citation2010; Nath and Inoue Citation2010). This article describes the nature of people's participation through RMF projects. The specific objectives of this study were to examine: (1) the extent and nature of local peoples' participation in practice; (2) the impacts of projects on the livelihoods of participants; and (3) the exact situation of the re-vegetation and resource conservation of the Madhupur Sal forests.

Materials and methods

Study area

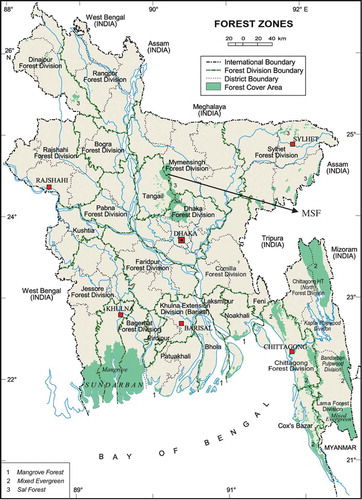

This study was conducted in the entire area covered by the RMF project. The total land surface area of Madhupur Sal forests is 25,495.96 ha in 1982 (Islam and Sato Citation2012a), which the major Sal forest of Bangladesh. Recent statistics showed that the forest cover is lower than 8000 ha in 2007 (NSP 2008) and is situated about 50 km by road from Tangail city and 30 km by road from Mymensingh city (Islam and Sato Citation2012a) (). The RMF project was implemented under the control of the Tangail Forest Division, and the Madhupur Sal forests of Tangail are administratively divided into four ranges or forest administrative units – Dokhola, Aronkhola, Madhupur, and National Park. Each range has one or more beat offices, and there are a total of 10 beat offices. In addition, about 50,000 people had lived in and around the Madhupur Sal forests for the last 40 years (Rahman Citation2010). In Madhupur Sal forests area, a total of 20,000 ethnic minorities (the majority are Garos, but there are a few Koch) had been living throughout the forests since time immemorial (Gain Citation2002), and they have a long history related to the forests.

Description of the forests

The present condition of the Madhupur forest cover varies along a gradient from open, heavily used, and degraded scrub, to relatively dense Sal coppice re-growth and scattered trees (NSP Citation2008). Although all areas have been subjected to some degree of exploitation, and a large range of wildlife species (e.g. tiger, leopard, elephant, sloth bear, and spotted deer) have become extinct, it is notable that important plant diversity still exists (NSP Citation2008). The prevailing species (more than 80%) of this forest is the commercially profitable Sal (Shorea robusta) tree. The estimated woody plant diversity comprises 176 species, 73 of which are trees (BCAS 1997; NSP Citation2008). The bird diversity has been estimated as 140 species; mammal diversity as 19 species; reptile diversity as 19 species; and amphibian diversity as 4 species (BCAS 1997; NSP Citation2008).

Description of the project

The RMF project resulted from the implementation in the Madhupur Sal forest area in June 2009 of a Bangladesh climate change trust fund worth 154,500,000 Taka (73 Taka = 1 US$) (FD Citation2012). Initially the project was launched for 2009–2011 and extended for another year. The project activities were carefully designed to develop human resources and alternative livelihood support at the local level necessary for the protection of forest resources ().

The project has been implemented with an integrated and holistic approach within the direct patronization of the local forest office. According to the FD offences record, the FD made a list of 500 encroachers (illegal logger) and provided 400 of them with two months' training (FD Citation2012). The rest of the 100 encroachers, and another 200 forest-dependent poor (person income less than 1 US$/day) people received the same training. Encroachers and forest-dependent people are hereafter referred to as participants. In total, 700 participants have received two months of intensive training which consists of nursery establishment and management, apiculture, fisheries, mushroom cultivation, afforestation, controlling forest fires, poultry, cow fattening, vegetable gardening, compost preparation, medicinal plant cultivation, jam and jelly production, honey bee cultivation, and grass production (FD Citation2012). After completing training, all participants were appointed as community forest workers (CFW), participating in forest development activities and assisting the forest guard in protecting the Sal forests. The CFW received wage worth 200 Taka on a weekly basis (FD Citation2012). As a part of capacity building, the FD (after three months of main training) organized another 15-day refresher training course for all CFW. The project also selected another 5500 forest-dependent families living in and around the Sal forests area as a part of their livelihood improvement. These 5500 families, together with 700 CFW, received incentives totaling 11,000 Taka.

In addition to these incentives, each CFW received an alternative livelihood opportunity (such as fisheries, poultry farm, or nurseries). CFW activities were monitored by the respective range office, and each of the range CFW units had a representative committee nominated by the general CFW. All CFW meet when called for, generally at least once a month in the Madhupur Forest Office. Senior FD officials and government officers already monitored the project activities, and their satisfaction level regarding the outcome of the project was high (The Daily Ittefaq Citation2010; Rahman Citation2010; Rauf Citation2010; Refazur Citation2010).

Sampling and data collection

The study comprised both qualitative and quantitative data in order to make the method pluralized. For qualitative information, this study follows in-depth interviews with participants, focus group discussions at each range office and a general discussion meeting at the Madhupur Forest Office. This study also conducted discussion with different levels of forest staff, and personal observation over the last three years. In the case of quantitative information, this study used a structured questionnaire. For the selection of the sample population, at first we collected the total number of participants and their detailed information from the Assistant Conservator of Forest (ACF) office at Madhupur. The total of 700 participants (500 encroachers and 200 forest-dependent people) consists of 671 male and 29 female poor people. Of them, 540 participants belong to Bengalis, while 160 belonged to ethnic communities. Most of the participants were extremely poor (daily income less than 1 US$) (Islam et al. Citation2012) and only 12% of the participants are literate. The literacy rate was measured according to Bangladesh government-prescribed criteria. This means those participants who can read and write were considered literate. Random sampling was carried out to select a population of 120 people, and the sample population consists of all types of people proportionate to their total number in each range. The sample population comprised 114 male and 6 female forest-dependent people of various ages (22–65 years). Majority (about 90%) of the respondents were encroachers and day laborers (rely on only daily labor wage). Furthermore, this study also covered the opinion of range officers (4), conservators (2), and Sal forest experts (6). The questions (for sampling participants) were related to project outcomes, livelihood aspects, and participation issues of the participants. Most of the questions were formatted, but in some cases, a few open-ended questions were also asked to draw out the participants' opinions and ideas. However, the opinion of the experts and other members was gathered from different types of questions, which were formatted according to the topics list (e.g. the social relationship between the FD and the participants). The experts' interview mainly focused on their opinions, perceptions, and knowledge, rather than numerical data. The entire study was carried out at different times: July–August 2009, September–October 2010, November–December 2011, and January 2012. One PhD student and two MS students of Bangladesh Agricultural University helped to collect data (as enumerator) and facilitated focus group discussion. Moreover, two ethnic leaders supported us to establish rapport with the ethnic participants. The study summarized all qualitative and quantitative data, and used SPSS version 15 for statistical analysis of quantitative data.

Theoretical frameworks

Participation

‘Participation’ is a word with different meanings to different authors (Karim Citation2000; Chowdhury Citation2004). Some have explained the notion of participation with the concept of influence, while others argued that participation means empowerment or democracy (Suzuku Citation2000). In the early 1960s, participation was principally meant as political participation and activities associated only with the voting and decision-making process. However, political participation has narrowed the concept of participation and it eventually excluded other development initiatives taken by the community (Samad Citation2003). Later on, in the 1970s, social scientists and other development organizations defined the term ‘people's participation’ as an essential part of development approaches (Samad Citation2003; Chowdhury Citation2004).

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, a community participation approach had come up, in which ‘projects with people’ and ‘benefit sharing by the poor’ approaches were established (Oakley Citation1991; Cornwall Citation2002). The World Bank described the concept of participation as ‘a process through which stakeholders influence and share control over development initiatives, decisions, and resources that affect them’ (World Bank Participation Sourcebook Citation1996: xi). On the other hand, community-supported development programs have been treated as essential building blocks in the empowerment of societies. They also provide a platform for the weak and legitimize collective decision-making processes (Tietjen Citation2001). The United Nations (Citation1975) defined and explained three interconnected, but different, processes for explaining participation: (1) the involvement of local people in decision-making; (2) the eliciting of their input to development programs; and (3) the ensuring of peoples' participation in benefit sharing from the development process. However, several scientists have argued that participation can be better understood in terms of its practical use. Uphoff (Citation1979) explained four distinct and interrelated types of participation: (1) participation in decision-making in identifying problems and planning alternative options and allocating resource; (2) participation in implementing activities and managing and operating programs; (3) participation for benefit sharing individually or collectively; and (4) participation in evaluating and monitoring activities (Chowdhury Citation2004). The United Nation Panel on People's Participation in 1982 suggested four different forms of participation in rural development: participation as collaboration, participation in community development activities, participation through organizations, and participation as a process of empowerment (Oakley Citation1988; Chowdhury Citation2004). So, the approach of participation has several dimensions and the most important issue is community or individual empowerment, and researchers' stated that participation and empowerment are interdependent (Chowdhury Citation2004; Mahmud Citation2004). However, several initiatives have been undertaken to introduce participatory process in the Bangladesh forestry sector in order to ensure peoples' participation in development projects. This study has attempted to assess peoples' participation on the basis of the Uphoff (Citation1979) classification of participation. Because the nature and types of participation in forest management in Bangladesh is more relevant to the Uphoff prescribed classification (Khan and Begum Citation1997; Chowdhury Citation2004). This means that the study is focused on the following areas: decision-making, implementation, benefit sharing, and the monitoring and evaluation process of RMF project implementations.

Livelihoods

In order to explore the impacts of the RMF project on participants' livelihoods, it is necessary to explain the livelihood concepts and their different dimensions. ‘A livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets (including both material and social resources) and activities required for means of living. A livelihood is sustainable when it can cope with and recover from stress and socks, maintain or enhance its capabilities and assets, while not undermining the natural resource base’ (Scoones Citation1998: 5). A number of agencies (e.g. Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, United Nations Development Programme, and Food and Agriculture Organization) have adopted livelihood approaches and continue to make use of livelihood frameworks. However, the Department for International Development (DFID)'s Sustainable Livelihood (SL) framework looks at the basic dynamics of livelihoods and how people are represented on a set of capital/assets as a basis for their livelihoods (Carney Citation1998; Hussein and Nelson Citation1998). Further, the DFID's framework is useful for explaining the interrelationship among different livelihood capitals and their utilization in diversifying livelihood strategies to attain desirable outcomes (such as increased income) in the available enabling environment. In DFID's framework, capitals are represented by the following categories: ‘Human’ (skill, knowledge, capacity, labor ability, and good health); ‘Social’ (relationship of trust and reciprocity, networks, and membership of groups); ‘Physical’ (basic infrastructure, transport, shelter, and communications); ‘Natural’ (land, forest, water, wildlife, and biodiversity); and ‘Financial’ (monetary resources – savings, credit, and remittances). The capitals are the building blocks of the participants' livelihoods and a range of assets are needed to attain positive livelihood outcomes (Das Citation2009; Shahabaz Citation2009). Improvement in all the five capitals could be termed ‘strong SL,’ while improvement in only some of the capitals that compensate for any decline in other capitals could be termed ‘weak SL’ or ‘poor SL’ (Das Citation2009). For the purpose of this study, the sustainable livelihood framework proposed by DFID (Citation2001) was used as the key point of reference.

Results and discussion

Participation as decision-making

In a true sense of local level decision-making, the RMF project did not fully execute the participants' decision-making process. The major responsibilities for decision-making and function were not vested with the participating people. The majority of the participants (91.67%) clearly mentioned that all of the main decisions related to project planning were made by the forest officers. They also added that their concerns and problems were treated with the same level of importance as those of the forest officers by the FD. The central FD decentralized their power to the divisional level, and the project-working plan was structured by the Divisional Forest Officer (DFO) with the collaboration of local-level forest officers (such as range officers) (FD Citation2012). On the other hand, empowerment is a multidimensional social process that helps people gain control over their own lives (Page and Czuba Citation1999). Local people gain power and control over their lives due to intensive training and other activities of the RMF projects. The project helped participants by teaching them how to effect change in a community or society. It was observed that the local community would feel responsible for their natural resources only when they could gain control over such resources, and when they felt that they have the decision-making rights to exercise such control (Breemer et al. Citation1995). It also found that decision-making rights are the key to mobilizing peoples' participation in natural resource conservation in Africa (Degeti Citation2003).

The RMF project itself identified the important issues of empowerment and demonstrated the ways to attain it. The devolution of power is always vested in the forest officer, and, in reality, the forest officer was always concerned with the participants' groups, and was prepared to execute any action plan that would make the situation better, compared to previous project activities in such areas (Safa Citation2004; Islam et al. Citation2010). While many of the working plans of this project originate from a bottom-up approach, the decision-making rights are controlled by the FD. So, the ongoing decision-making process of the RMF project showed an unbalanced power relationship between the FD and participants, which affects peoples' participation. Similarly, in India, the Joint Forest Management program created an unbalanced power relationship between the FD and local communities, with the FD retaining control over most forest management decisions. The local communities were unable to accept such control, and thus, peoples' participation was affected due to conflict between the two entities (Sarin et al. Citation2003). The greatest challenge to effective participation is usually the FD officials' decision-making behavior, which tends to inhibit a participatory approach. About 87% respondent claimed that FD officers had always played the dominant role and controlled the whole decision-making process in the general meetings. However, government officials have an important role in ensuring peoples' participation as the arm of government responsible for executing the projects in rural areas (Wallis Citation1989; Chowdhury Citation2004). Participatory approaches supported by government have facilitated the empowerment of local people, such as community forest management in India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka (Fernandes et al. Citation1988; Gronow and Shrestha Citation1991; Sarin et al. Citation2003; Nayak Citation2006).

Another hallmark of the project was that the FD formed an independent committee including local ethnic and non-ethnic people to select 5500 forest-dependent families. So, the culture of collective planning does have a significant effect on participants, and it ultimately mobilized their participation in project implementation and execution. Collective action and planning have the potential to change the outcomes of the participatory projects in Bangladesh (Nath and Inoue Citation2010). It was generally comprehended that participation in government-run projects often meant no more than providing input, which was recurrently constructed with an active form of participation, involving control over decisions, formation of groups, plans, and implementation (Rahman Citation1993; Smith et al. Citation1993; Smith Citation1998). However, the RMF project not only provided government incentives, but also ensured people's participation in various ways, in which forest officers' positive attitudes toward addressing peoples' real needs and problems had played an important role. Therefore, the study revealed that the project makes every effort to build the participants' skills and knowledge, which would empower them to improve their own lives.

Participation as implementation

Participatory development programs cannot be sustained without local communities' participation in the sense of cooperation (Smith Citation1998). The study observed that there was a strong collaboration and friendly relationship among the FD, government institutions, and participating people. Even the participants who were engaged in illegal logging activities now maintain a good relationship with the FD staff (FD Citation2012). During the two months of intensive training and CFW activities, each of the participants got to know everyone well. Thus, a strong collaborative and cooperative attitude formed among them. Almost 70.83% participants mentioned that previously they (mainly encroachers) were treated as opponents to others and often fought with each other. In every focus group discussion, the participants unanimously expressed the feeling that a strong cooperation and linkage occurred among them and the FD. Therefore, the study summarized that all forms of cooperation and linkages are always beneficial to the participants, and the RMF project established a strong cooperation and linkages among the stakeholders. Similarly, Panicker and Dhands (Citation1992) mentioned that people's cooperation would be necessary to implement any action plan in development programs, and their study also provided successful evidence of a mosquito control scheme with the active cooperation of local people in Kerala, India.

In many countries, plans for ecosystem conservation and implementation of development activities have failed to address the local knowledge and real needs of forest-dependent peoples (Ellen Citation1986; Kumar Citation2000). However, participation and motivation by local communities is essential to any conservation effort. During the two months' training, the participants not only received training, but also acquired a strong level of motivation from different senior government officials/professionals. The participants were assured by respected government officials that their forest offences would be dismissed if they would cease their illegal logging. Little by little, they realized the offer was sincere. Previously, every participants were depends on Sal forests for their firewood consumptions (although it was prohibited). However, this study found that after training, majority (74%) of the participants collected firewood other than Sal forests source. Eventually, they also discouraged other people from illegal logging activities in the Sal forest area (The Daily Ittefaq Citation2010; Rahman Citation2010; Rauf Citation2010). As a consequence, participants gained social acceptance, and one of them has already been elected as a Union Parishad Leader (Local Government). The project implementation also had a significant impact on their attitudes and perceptions. Accordingly, this study revealed that the school attendance of participants children have been increasing of 32.5% compare to their previous situation. However, Madhupur Upazilla has only a 37.1% literacy rate (Banglapedia Citation2012), and the literacy rate among the participants was less than 12%. In a study of community forestry in India, Singh (Citation1996) found that changing local peoples' attitudes and getting their active participation may lead to more effective conservation of forests.

The participants received training, and the FD realized that without any alternative livelihood options, they might revert to their previous profession of illegal logging. From the project funds, every participant received 10,000 Taka to start an alternative livelihood opportunity. For this, participants needed to form a homogenous group of at least 10 people. The FD doled out the money after the participant groups were formed and it received satisfactory proposals from them. The FD was also directly monitoring the whole process, thus reducing the chance of initiative failure. About 84.16% of the participants have started bull fattening, nursery establishment, fisheries, or poultry farms. In the initial stages, their sincerity and devotion were remarkable, and now it is not possible to say that the new livelihood approaches are sustainable. However, the participants' true devotion and collective actions definitely help run the new initiatives sustainably. In addition, every participant would get one hectare of land to start participatory forestry programs on a 10-year-tenure basis, which would help them to improve their livelihoods (Islam et al. Citation2010; Islam and Sato Citation2012a). Therefore, alternative livelihood opportunities provided by the RMF project have a positive impact on the socioeconomic well-being of the participants and will ultimately mobilize their participation in project activities. Similarly, in a case study of Cogtong Bay, Philippines, it was observed that the coastal management project was sustainable due to its provision of a 25-year lease to the local community (Primavera Citation2000). Likewise, Kairo (Citation1995) and Masoud and Wild (Citation2000) mentioned that alternative facilities enhanced peoples' participation in government-driven projects in Kenya and Tanzania.

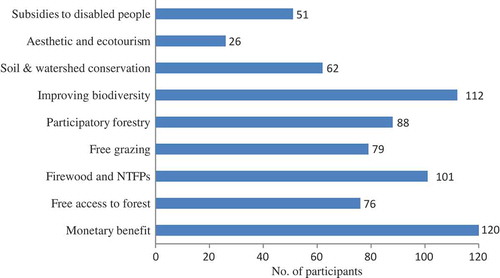

Participation as benefit sharing

One of the important aspects of this project was to provide wage support to the participants on a regular basis. During the training period, participants received 150 Taka per person as a daily allowance. After finishing the training, they were appointed as CFW and received a wage on a weekly basis. This wage employment provided a big boost and enabled the participants to make full use of their productive assets. Before starting the alternative livelihood approach, this provision of incentives had played a significant role toward changing participants' attitudes and supporting their families. Another important feature of the project was transparency, as all the money transactions were made via bank accounts or checks. In addition to this, every participant and 5500 forest-dependent families received incentives amounting to 11,000 Taka () as a part of their livelihood improvements. Moreover, participants were asked whether they expected any benefit from participating in the RMF project. Almost every participant replied that they expected much more benefit from this project. All respondents indicated that monetary benefits strongly motivate them, and 93% of participants expected to improve tree species (biodiversity) through project activities (). However, multiple responses were obtained from many of the participants express their major expectations for project benefits. The results also figure out the real benefits of the RMF projects that the participants had enjoyed. Seventy-nine percent of participants mentioned the monetary benefits and tree species improvement through implementation of RMF project. Although, 25% participants directly claimed that their firewood and Non Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) collection and free-grazing facilities have been restricted due to the implementation of RFM projects. In a study in Africa, Degeti (Citation2003) found that monetary benefits together with free access rights enhanced peoples' participation in forest conservation activities.

Table 1. Incentives (money) provided by the FD to the forest-dependent people

The striking feature of the RMF project was its assurance that the participants would share the plantation produce equally with the FD and would be able to take part in the participatory forestry program. In the participatory forestry program, the farmer has to share only tree produce at a 45%/45% basis with the FD, and the other 10% would be stored for the future tree farming fund (TFF). Each rotation (program length) has a 10-year duration, and participants can use up to three rotations if they maintain program criteria properly. Moreover, participants can cultivate agriculture crops along with trees at any time of the program tenure, and the entire crop output would be the participant's property (Islam et al. Citation2010; Islam and Sato Citation2012a). However, all respondent reported that they received incentives and logistical support from the FD in proper ways. As the study observed, this resulted in overall participant satisfaction with and devotion to the program (open discussion with participants in a general meeting in December 23, 2011). Similarly, a case study in the southern part of Thailand located in the Andaman Sea revealed that government concessions to local people was the key factor for effective participation and made the project successful (Kazuhiro Citation2000).

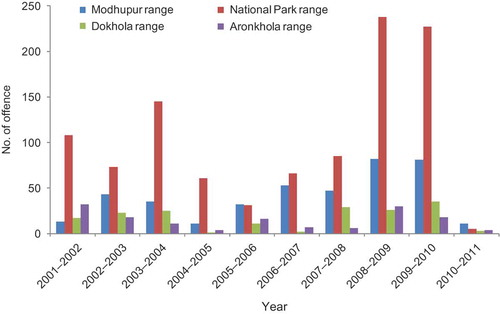

The participants' capacity building and rehabilitation process have reduced the unexpected environmental risks and withstand vulnerability. Therefore, as the forest-dependent people have acquired livelihood security, it is safe to say their forest dependency may decrease. In the Madhupur Sal forest area, the forest dependency of participants and families has been reduced by the active support of the RMF project. Interviewing with FD staff, this study found that majority of the forest offences had occurred by the 500 listed encroachers in the Madhupur Sal forests area. FD staff also mentioned that due to the implementation of RMF project, forest offences were gradually decreased in 2010–2011 compared to previous records () (FD Citation2012). In 2010–2011, the offences were reduced to only 23, while they numbered 361 and 376 in 2008–2009 and 2009–2010, respectively (FD Citation2012). Only three offences have been reported so far for 2011–2012. Thus, the initiative of the RMF projects was clearly a new paradigm that ensured the security of the participants and reduced illegal logging. In a case study in Vietnam, Kazuhiro (Citation2000) found that government conservation and afforestation schemes had a positive impact on the security of local communities that depend on natural resources, and thus, their attitudes toward excessive resource collection improved.

Participation as monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring and evaluation is the process of collecting and analysing information about the projects in order to reach the project objectives. It also helps to identify the desired impact of the projects. At the same time, it is important to avoid spending too much time and/or money on monitoring and appointing staff to obtain outcomes that are too idealistic: in the long run, this would be counterproductive (Nampila Citation2005). In the RMF project, monitoring and evaluation were also the FD's responsibilities, and participants have participated in the projects' performance appraisal. So far, the study observed that a good institutional form of accountability existed in the participants. Every participant's performance was critically evaluated in general meetings with the presence of the FD staff. The participants also noted that the frequency of field visits and inspections by the FD staff were not many, but met the minimum level. Almost 97% of participants reported that the FD personnel were sincere in their desire to work on the project. Participants also mentioned that the FD played the role of facilitator, rather than controlling participants who have traditional knowledge and experiences. Moreover, in the participatory process, skilled people or organizations who can act as catalysts are essential (De Beer and Swanepoel Citation1998). In this project, the FD acted as a catalyst and mentioned that the last two years' participants were carefully monitored due to their previous professions, and so far, their performance has been quite impressive. This trend of participation would be very effective to protect the Sal forests.

Factors affecting peoples' participation

This study also identified the main factors affecting peoples' participation in the project. The results revealed that about 98.33% of participants reported that they had to face bureaucratic problems at the trials that dismissed forest offences. They had to endure a complex process and often faced illegal money demands by the police department and justice office staff. Conversely, the local police department said that they tried their best to process the offences quickly, but due to official formalities could not. They refuted claims of illegal money demands. It was also noted that 15% of the participants had more than 50 forest offences each, and the study found a participant who had 105 forest offences (the highest). The participants (68.33%) also mentioned that they did not receive timely incentives. The FD, on the other hand, agreed that due to some official process, and because many of the participants did not have bank accounts, money transactions were delayed. In addition, some powerful leaders/elites have brickfields and sawmills (more than 100) situated at the Madhupur forest area, and they used illegal Sal timber/firewood for making bricks and furniture. Thus, the elite had to hire encroachers, who they paid minimum wage (Integrated Protected Area Co-management Citation2009). Now, the situation has changed, and the elite are creating immense pressure on the CFW to do the encroaching, and often they contacted the police department to arrest CFW. About 72.5% of the participants mentioned such problems and wanted immediate action. In a forest management study of India, Singh (Citation1992) mentioned that there are several constraints which can limit peoples' participation in natural resource management programs. Of them, availability of grants and subsidies, interference by politicians, and misunderstanding among organizations were important factors. Finally, it may be summarized that every project has some constraints, but in the case of the RMF, the bureaucracy of forest offences, and ill motives by local elites and leaders were the crucial factors that must be improved for active participation of the participants and resource conservation.

Livelihood assessments

Participants of the RMF project were selected based on their poverty level and previous forest offences. In the previous studies of Safa (Citation2004) and Muhammed et al. (Citation2008), it was mentioned that the Sal forest-dependent people were generally from the poorer sectors of the local community. Therefore, the participants were involved in the project in order to support their own livelihoods. After involvement in the program, they were able to build up several types of livelihood capitals, and this study examines some important variables of these capitals.

Human capital

Training on different aspects has improved participants' human capital, so they can easily improve household income (Islam et al. Citation2010). Out of the total project budget, more than 15% of the money was spent for training purposes of the forest-dependent people (FD Citation2012). The FD offered a two-month intensive training program, which played a valuable role in the knowledge and skill development of 700 participants. The training program was able to create leadership and build a strong network among the participants in which they could work as a team, all of which have ensured the participants' capacity building. This study monitored the capacity building of participants according to the five key elements proposed by Garlick (Citation1999) in

Table 2. Different elements and their observations for capacity building of the participants

Almost all the participants received training components without major difficulties, and this study judged the effectiveness of the training program. Again, the FD arranged 15-day refresher courses for all the participants, which easily explained the training content. This study also evaluates the overall skill and improvements of the participants for five important training programs through a 5-point rating scale (1 = Very good, 2 = Good, 3 = Satisfactory, 4 = Poor, 5 = Very poor), which is presented in In the refresher course, each of the participants was requested to select one or two specific programs in which they wanted to start a group. The study also observed that the FD gave the highest priority to capacity building, due to the fact that the illiterate participants were unable to start any alternative livelihood program unless they were fully trained. Trainings can enhance skills, and skills might have significant impacts on the participants' attitude and perception of living, as well as forest conservation. Moreover, participants acquired skill and knowledge had an impact on the social capital, such as building relationship and encouraging self-capacity with the participating people.

Table 3. Five important training programs and assessment of the participants' performance

On the other hand, poor participants living in remote areas normally have limited access to health services. In Bangladesh, the government health program tends to have better coverage in urban areas. It was true in the project areas that the poorest had to make serious sacrifices to afford medical services. Often, the government health facilities were located far from their homes. In addition, government social service subsidies were not well implemented (Barret and Beardmor Citation2000). However, this study observed that due to intensive training, participants' awareness of health care increased, and almost 87.5% of participants went to a local clinic or government hospital (although they are far from their homes) to get treatment in case of family illness. In addition to this, 24.76% participants (out of 87.5%) visited government hospitals for the 1st time of their life during the RMF project implementation period. Participants also mentioned that their rate of hospital attendance has increased due to the motivation, economic benefits, and information provided by the RMF project; and hospital attendance can indicate the improvement of participants' family health care system.

Physical capital

The RMF project provided money to make improvements for all the participants and the other 5500 family household structures. The study observed that 100% of the participants and 3000 families already improved their homestead structure with the guidance of forest personnel. Another 2500 families were on the way to improve their household structure. All participants bought a small ruminant (usually a cow or goat) after receiving the project incentives of 5000 Taka. Moreover, there were directions from the central government office to all concerned departments to unite their development and regular activities in the project areas in order of precedence. Although it was behind the RMF project capacity to improve all common roads, electricity, drinking water, and school structures, the initiatives have been processed due to the participants' active roles in the projects. Nevertheless, in the presence of strong physical capital, especially for good transportation and communication, the natural assets were managed easily by the participants and even for FD staff. Good transportation and communication facilities have positively affect the development of financial capital of the participants (Islam and Sato Citation2012a).

Social capital

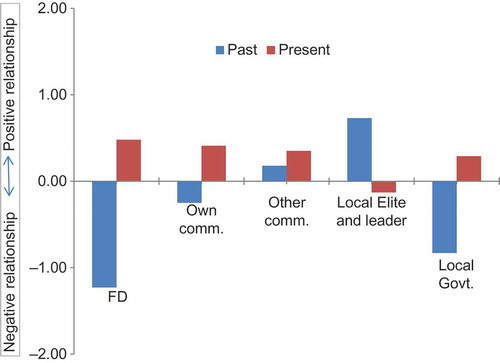

The participants' acquisition of skill and motivation had an enormous impact on the social capital, such as building relationships and encouraging self-capacity for the participants. The study observed that due to intensive training and CWF activities, a social network occurred among participants and local communities as well. On a measurement scale of –2, –1, 0, 1, 2 (–2 is strongly negative and 2 is strongly positive), the study visualized a past and present social relationship scenario among the participants and their community (). It was noted that previously participants had strong negative relationships with the FD and local government, and the literature review articulated similar results (Safa Citation2004; Muhammed et al. Citation2008; Islam et al. Citation2010; Islam and Sato Citation2012b). However, the existing relationship among the participants, the FD, and local government is much better than it was previously (). The figure also represents that participants have negative present trends of social relationships with the local elite and leaders. The study noted that, previously, local elite and leaders had used participants for illegal logging activities, and a similar report was published by Ahmed (Citation2008); Gain (Citation2002), and Islam et al. (Citation2010), However, the participants possess a good social relationship with their own communities compared to the past.

Figure 6. Past and present social relationship between the participants and other people of the society.

Although social capital is an attribute of an individual in a social context (Sobel Citation2002), the growth of social capital depends on the institutions, relationships, attitudes, and values that govern interactions among participants and contribute to economic and social development (World Bank Citation2002). Therefore, they are difficult to measure. The participants were also asked about their household food security throughout the whole year, with 45 (out of 120) participants responding that they suffered from food shortages. Overall, this project has improved the food insufficiency rate of participants, but still a considerable number of participants were suffering from food shortages. Food sufficiency is treated one the important parameter to judge the participants livelihoods security and also treated as a social parameter (Moser Citation1998). In addition, social capital brings collective action among the participants and their own communities, which indicates a strong influence of social capital to other capitals.

Natural capital

Natural capital denotes environmental assets, such as land, and common property resources, such as forests, water, or grazing land (Islam and Sato Citation2012a). In RMF projects, participants already planted 1,100,000 tree species in their homestead premises, together with another 2,532,000 different species of local timber, fuelwood, fodder, and fruit in the Sal forests. Moreover, each participant received a participatory forestry plot of 1 ha land, all of which effectively enhanced participants' natural capital. The participants adopted homestead agroforestry technology due to training and the good social relationship with other communities, from which they derived extra income, which they used for subsistence purposes. Land is an important natural capital and the majority of participants (about 84.16%) were categorized as landless, having 0–0.2 ha land (Iqbal Citation2007). However, the participatory plot/land is owned by the FD, and so it should not be included in the measure of the participants' total farmland. Free access to Sal forests was already restricted for local people, and this study observed that a majority of participants (about 81.6%) depends on forest resources, especially for firewood. It was anticipated that the project might be helpful in minimizing the firewood demands of participants, but the reality turned out different. Similarly, in research on the Madhupur Sal forest, Islam et al. (Citation2012) observed that about 73% of forest-dependent people had severely exploited Sal forests for their firewood consumption.

Financial capital

Financial capital refers to the financial resources that participants use to achieve their livelihood objectives (DFID Citation2001). Participants have needed a regular flow of money to ensure their financial capital, and the project supplied wage support as a transition to an alternative livelihood approach. It is normal that participants invested financial capital to achieve their children education and health care (human capital) and to cover household expenditures that partly sustained their livelihoods. In addition, the day labor scope was a good source of income for trained participants in nearby agriculture farms and other commercial farms. On the other hand, participants' natural stocks (e.g. trees and cattle) would supply emergency financial returns in order to face family crises. About 38% of participants agreed that the project outcomes were not able to ensure their food requirements throughout the whole year. Therefore, the project support would be a boost to livelihood capitals, especially the human, social, and natural capitals of the participants, but the sustainability of livelihood capitals depends on the development of all (five) capitals.

Re-vegetation and forest conservation

According to the NSP (Citation2008) report, in the Madhupur Sal forest area, about 47.3% of the forest land, was converted to agricultural and fallow lands, most of which was grabbed by local elites and powerful leaders (Gain Citation2002, Citation2005; Islam et al. Citation2010). Now, the FD has tried to retrieve such land and to initiate re-vegetation strategies. Already 1000 ha of land was covered by local timber species and included participants under the umbrella of the participatory forestry (). Participants would get as much benefit as the FD (i.e. 45% to participants, 45% to the FD, and 10% to Future Tree Farming Funds), and the re-vegetation process might be treated as ‘greening the Sal forests’. In addition to re-vegetation of Sal forests, 700 participants and 5500 forest-dependent families planted 200 tree species in each of their homestead premises. Although it was uncertain whether 100% of the species would survive after five years, the process is certainly a noble initiative. On the one hand, participants have started greening the Sal forests, and on the other hand, they opposed human intervention to the Sal forests as forest guards. This process has had a significant impact on the natural regeneration process of the Sal forests (The Daily Ittefaq Citation2010; Rahman Citation2010; Rauf Citation2010; Refazur Citation2010; FD Citation2012).

Table 4. Re-vegetation scheme of Madhupur Sal forests area

Conclusions

People's participation in forest management through the RMF project has been improving or greater than before. In spite of the generally low participation of local people in the Bangladesh forestry sector projects, there is no doubt that the RMF project has already set a model example, with a number of inspiring successes and future potential. First, it has reduced the long-term conflict between local communities and the FD. The initiatives to rehabilitate the encroachers have already reached a milestone by improving the overall relationship between the two entities. Second, the participants' capacity building through intensive training and alternative services of RFM projects has provided the power to withstand vulnerability and shocks over their own lives, over their community, and over society as a whole. Third, the project seems to have had a significant impact on the participants' livelihoods, especially the building of their human, social, and natural livelihood capitals. Fourth, the project has established a sense of security among the participating poor people. As soon as the project was implemented, the participants realized that the FD has properly addressed their real needs and problems, and they may look forward to future positive action by the FD. Finally, the project has already made an outstanding example in combating the rate of illegal logging toward deforestation and greening the forest area with suitable native tree species. Therefore, the re-vegetation process, together with protecting deforestation and human interventions in the Sal forests, has had a significant impact on its natural resource conservation. All of those positive impacts could enhance the project's success from a participation, livelihood, and resource conservation point of view.

The project is still in its initial stage, and it is too early to make a list of recommendations and policy implications. Rather, the present study provides some practical suggestions for the sustainability of project objectives. First, the study has introduced some complex procedures in order to dismiss participants' forest offences and to address a few bureaucratic problems in the project's operation. To address these problems, top government action is needed to create strong coordination between the local FD, police, the justice department, and local government offices to minimize missed communication and ego gaps. Second, all brickfields and sawmills situated in the Sal forest area need a strong monitoring system so that Sal timber cannot be used illegally. The study also abolishes the existing negative social relationship between participants and local elites who own the saw mills and brickfields. Third, the devolution of power was mainly controlled by the FD, and there was less room for participants to make decisions or control the project implementation process. These power imbalances have affected participants' empowerment. Finally, both the participants and the sustainability of the Sal forest area need to continue the project for at least another two years. The project has just started to build the livelihood capitals of the participants. To make the livelihood sustainable, all of its capitals and equivalent improvements are mandatory. It very vividly demonstrates that the ultimate solution to the development and resource conservation process of Sal forests lies in the improvement of the forest-dependent people's livelihoods in the most comprehensive and sustainable way. However, considering the few limitations, the RMF projects remain a good example of facilitating participation and resource conservation in Bangladesh. Further, it can also encourage other countries that face similar deforestation to follow Bangladesh's example.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Madhupur Sal forest office for their assistance and active support during data collection. Our thanks are extended to Interdisciplinary Programs in Education and Projects in Research Development (P&P Program), Kyushu University, Japan for supporting us with the research funds.

Notes

References

- Ahmed , MU . 2008 . Underlying causes of deforestation and forest degradation in Bangladesh. A report submitted to Global Forest Coalition (GFC) 15 – 18 . the Netherlands

- Alam , M. 2009 . Evolution of forest policies in Bangladesh: a critical analysis . Int J Soc Forestry , 2 ( 2 ) : 149 – 166 .

- Alam , M , Furukawa , Y , Sarker , SK and Ahmed , R. 2008 . Sustainability of Sal (Shorea robusta) forest in Bangladesh: past, present and future actions . Int Forestry Rev , 10 ( 1 ) : 29 – 37 .

- Bangladesh Centre for Advance Studies . 1997 . “ Demographic and Social-Economic Survey ” . In Ministry of Environment and Forest, GOB, National Conservation Strategies , Dhaka , , Bangladesh : Implementation Project-I .

- Banglapedia. 2012. National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh [Internet]. Bangladesh; http://www.banglapedia.org/httpdocs/english/index/T.htm (http://www.banglapedia.org/httpdocs/english/index/T.htm) (Accessed: 12 January 2012 ).

- Barret , A and Beardmor , R . 2000 . Poverty reduction in India: towards building successful slum upgrading strategies . Discussion Paper for Urban Futures 2000 Conference . 2000 . Johannesburg , , South Africa

- Breemer , VD , Drijver , CA and Venema , LB . 1995 . “ Local resource management in Africa. Chichester (UK) and New York ” . In John Wiley & Sons

- Carney , D. 1998 . Sustainable rural livelihoods; what contribution can we make? , London , UK : Department for International Development .

- Chowdhury , SA. 2004 . Participation in forestry: a study of people's participation on the social forestry policy in Bangladesh: myth or reality [M.Phil. dissertation] , Bergen , , Norway : Department of Administration and Organization Theory, University of Bergen .

- Cornwall , A. 2002 . Introduction: new democratic space? The politics and dynamics of institutionalized participation . IDS Bull , 3 ( 2 ) : 2

- The Daily Ittefaq. 2010. Madhupurgorer Gaschorder Paharadar Kore Sufolmilse (in Bengali). The Daily Ittefaq Group of Publication; http://ittefaq.com.bd/content/2010/09/04/ (http://ittefaq.com.bd/content/2010/09/04/) (Accessed: 15 December 2012 ).

- Das , N. 2009 . “ Can joint forest management programme sustain rural life ” . In a livelihood analysis from community-based forest management groups MPRA Paper No. 15305:2

- De Beer , F and Swanepoel , H. 1998 . Community development and beyond: issues, structures and procedures , Pretoria , , South Africa : JL Van Schaik Publisher .

- Degeti , T. 2003 . “ Factors affecting people's participation in participatory forest management ” . In the case of IFMP Adaba-Dodola in Bale zone of Oromia Region [MSc dissertation] , Addis Ababa , Ethiopia : Addis Ababa University .

- [DFID] Department for International Development . 2001 . Sustainable livelihood guidance sheets – comparing development approaches , 2 – 22 . London , UK : Department for International Development. p .

- Ellen , R. 1986 . What black elk left unsaid . Anthropol Today , 2 ( 6 ) : 8 – 12 .

- [FD] Forest Department. 2012. Land and forest area of Bangladesh [Internet]. Bangladesh Forest Department; http://www.bforest.gov.bd/act.php (http://www.bforest.gov.bd/act.php) (Accessed: 20 January 2012 ).

- Fernandes , W , Menon , G and Philip , V. 1988 . Forest, environment and marginalization in Orissa , 363 New Delhi , India : Indian Social Institute. p . Tribes of India Series No. 2

- Gain , P. 2002 . The last forest of Bangladesh , Dhaka , Bangladesh : Society for Environmental and Human Development (SEHD) . Book for Forester

- Gain , P . 2005 . Bangladesher Biponno Bon (In Bengali) , Dhaka , Bangladesh : Society for Environmental and Human Development (SEHD) . editor.Book for Forester

- Garlick , B. 1999 . “ Elements of capacity building ” . In Community capacity building. Paper presented at: Australian Association for Research and Education Conference; Brisbane, Australia. p. 65–93 Edited by: McGinty , S . editor

- Gronow , J and Shrestha , NK . 1991 . From mistrust to participation: the creation of a participatory environment for community forestry in Nepal. Social Forestry Network Paper No. 12/b , London , UK : Overseas Development Institute .

- Hussein , K and Nelson , J. 1998 . “ Sustainable livelihood and livelihood diversification ” . In IDS Working Paper, No. 69 , Brighton , UK : Institute of Development Studies .

- Integrated Protected Area Co-management . 2009 . Site-level field appraisal for forest co-management: IPAC Madhupur site , 41 Bangladesh : A project report by RDRS .

- Iqbal , MT. 2007 . Energy input and output for production of Boro rice in Bangladesh . Electron J Environ Agric Food Chem , 6 ( 5 ) : 2144 – 2149 .

- Islam , KK and Sato , N. 2012a . Participatory forestry in Bangladesh: has it helped to increase the livelihoods of Sal forests dependent people . South Forests: J Forest Sci , 74 ( 2 ) : 89 – 101 .

- Islam , KK and Sato , N. 2012b . Deforestation, land conversion and illegal logging in Bangladesh: the case of the Sal (Shorea robusta) forests . iForest Biogeosci Forestry , 5 ( 1 ) : 171 – 178 .

- Islam , KK , Sato , N and Hoogstra , M. 2010 . Poverty alleviation in Bangladesh: the case of the participatory agroforestry program . Int Forestry Rev. , 12 ( 5 ) : 412 – 415 .

- Islam , KK , Ullah , MO , Hoogstra , M and Sato , N. 2012 . Economic contribution of participatory agroforestry program to poverty alleviation: a case from Sal forests, Bangladesh . J Forestry Res , 23 ( 2 ) : 323 – 332 .

- Kairo , JG. 1995 . “ Community participatory forestry for rehabilitation of deforested mangrove areas of Gazi Bay ” . In Technical report, Biodiversity Support Program , 100 Washington , DC : USAID .

- Karim , A. 2000 . “ Recent changes in the structure of the Union Parishid in Bangladesh: scope for participation of women ” . In a study of twelve Union Parishad [MPhil dissertation] , Bergen , , Norway : Department of Administration and Organization Theory, University of Bergen .

- Kazuhiro , A . 2000 . Socioeconomic study on the utilization of mangrove forests in Southeast Asia . Pacific cooperation of on research for conservation of mangroves, proceedings of Asia-Pacific . 2000 . Okinawa , , Japan Paper presented at

- Khan , NA and Begum , SA. 1997 . Participation in Social Forestry re-examined: a case study from Bangladesh . Dev Pract , 7 ( 3 ) : 260 – 266 .

- Kumar , N. 2000 . All is not green with JFM in India . Forest Trees People , 42 ( 1 ) : 46 – 50 .

- Lawes M, Eeley H, Shackleton C, Geach B, editors. 2004. Indigenous forests and woodlands in South Africa: policy, people and practice [Internet]; http://www.gbv.de/dms/goettingen/470178310.pdf (http://www.gbv.de/dms/goettingen/470178310.pdf) (Accessed: 22 March 2012 ).

- Mahmud , S. 2004 . Citizen Participation in the health sector in rural Bangladesh: perception and reality, in new democratic space? . IDS Bull , 35 ( 2 ) : 11 – 18 .

- Masud , TS and Wild , RG . 2000 . Sustainable use and conservation management of mangroves in Zanzibar, Tanzania . Pacific cooperation of on research for conservation of mangroves, proceedings of Asia-Pacific . 2000 . Okinawa , , Japan Paper presented at

- Moser , C. 1998 . The asset vulnerability framework: reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies . World Dev , 26 ( 1 ) : 1 – 19 .

- Muhammed , N , Chowdhury , Koike M MSH and Haque , F. 2011 . The profitability of strip plantations: a case study on two social forestry divisions in Bangladesh . J Sustain Forestry , 30 ( 3 ) : 224 – 246 .

- Muhammed , N , Koike , M , Haque , F and Miah , MD. 2008 . Quantitative assessment of people oriented forestry in Bangladesh: a case study from Tangail Forest Division . J Environ Manage , 88 ( 1 ) : 83 – 92 .

- Nampila , T . 2005 . Assessing community participation – the Huidare informal settlement [MSc dissertation] , Stellenbosch , , South Africa : University of Stellenbosch .

- Nath , TK and Inoue , M. 2008 . How does local governance affect project outcomes? Experience from a participatory forestry (PF) project in Bangladesh . Int J Agric Resour Governance Ecol , 7 ( 1 ) : 491 – 506 .

- Nath , TK and Inoue , M. 2010 . Impacts of participatory forestry on livelihoods of ethnic people: experience from Bangladesh . Soc Nat Resour , 23 ( 11 ) : 1093 – 1107 .

- Nayak , PK. 2006 . Politics of co-option: self-organized community forest management and joint forest management in Orissa, India [MSc dissertation] , Winnipeg , CA : University of Manitoba .

- [NSP] Nishorgo Support Project. 2008. Framework management plan for Madhupur National Park, Nishorgo Support Project [Internet]. Nishorgo Bangladesh; http://www.nishorgo.org/nishorgo2/pdf/reports/GENERAL%20REPORTS/1.MNP_Framework_ManagementPlan/ (http://www.nishorgo.org/nishorgo2/pdf/reports/GENERAL%20REPORTS/1.MNP_Framework_ManagementPlan/) (Accessed: 20 January 2011 ).

- Oakley , P . 1988 . “ Strengthening people's participation in rural development ” . In New Delhi (India): Society for Participatory Research in Asia , Occasional Paper Series No. 1 .

- Oakley , P . 1991 . Project with people: the practice of participation in rural development , 304 Geneva , Switzerland : International Labor Organization. p .

- Oksanen , T , Pajari , B and Tuomasjakka , T , eds. 2003 . Forests in poverty reduction strategies: capturing the potential , 206 Torikatu , Finland : European Forest Institute. p . editors

- Page , N and Czuba , CE. 1999 . Empowerment: what is it? . J Ext , 37 ( 5 ) 5, Editor's Page

- Panicker , KN and Dhanda , V. 1992 . Community participation in the control of filariasis . World Health Forum , 13 ( 1 ) : 177 – 181 .

- Primavera , JH . 2000 . Philippine mangrove: status, threats and sustainable development . Pacific cooperation of on research for conservation of mangroves, proceedings of Asia-Pacific . 2000 . Okinawa , , Japan Paper presented at

- Rahman M. 2010 Aug 11. Boner Adibashider Shongenia Bonrokha (in Bengali). The Daily Protom Alo; http://www.prothomalo.com/detail/date/2010-08-11/news/85515 (http://www.prothomalo.com/detail/date/2010-08-11/news/85515) (Accessed: 25 November 2010 ).

- Rahman , MA. 1993 . People's self-development. Perspective on participatory action research , London , UK : Zed Books .

- Rauf MA. 2010 Aug 2. Bon Khekora Ekon Bon prohori (in Bengali). The Daily Amar Desh; http://www.amardeshonline.com/pages/home/2010/08/02 (http://www.amardeshonline.com/pages/home/2010/08/02) (Accessed: 10 December 2012 ).

- Refazur R. 2010 Aug 19. Gaschorder Dia Bonrokka (in Bengali). The Daily Jugantor; http://jugantor.us/enews/issue/2010/08/19/ (http://jugantor.us/enews/issue/2010/08/19/) (Accessed: 19 December 2012 ).

- Safa , MS. 2004 . The effect of participatory forest management on the livelihood of the settlers in a rehabilitation program of degraded forest in Bangladesh . Small-Scale Forest Econ, Manage Policy , 3 ( 2 ) : 223 – 238 .

- Salam , MA and Noguchi , T. 1998 . Factors influencing the loss of forest cover in Bangladesh: an analysis from socioeconomic and demographic perspectives . J Forestry Res , 3 ( 1 ) : 145 – 150 .

- Samad , M. 2003 . Participation of the rural poor: in government and NGO programs , Dhaka , Bangladesh : Mowla Brother .

- Sarin , M , Singh , N and Bhogal , RK. 2003 . “ Devaluation as a threat to democratic decision-making in forestry? Findings from three States in India ” . In Working Paper No. 197 , UK : Overseases Development Institute .

- Scoones , I. 1998 . “ Sustainable rural livelihood: a framework for analysis ” . In IDS Working Paper No. 72 , Brighton , UK : Institute of Development Studies .

- Shackleton , CM. 2001 . Re-examined local and market oriented use of wild species for the conservation of biodiversity . Environ Conserv , 28 ( 1 ) : 270 – 278 .

- Shackleton , CM , Shackleton , SE , Buiten , E and Bird , N. 2007 . The importance of dry woodlands and forests in rural livelihoods and poverty alleviation in South Africa . Forest Policy Econ , 9 ( 1 ) : 558 – 577 .

- Shahbaz , B. 2009 . Dilemmas in participatory forest management in northwest Pakistan. A livelihoods perspective . Hum Geogr Ser , 25 ( 1 ) : 15 – 16 .

- Singh , K. 1992 . “ People's participation in natural resources management ” . In Factors affecting people's participation in participatory forest management: the case of IFMP Adaba-Dodola in Bale zone of Oromia Region [MSc dissertation] , Edited by: Degeti , T . Addis Ababa , Ethiopia : Addis Ababa University. p. 29 . editor

- Singh S. 1996. Joint forest management in India. In: Isager L, Theilade I, Thomson L, editors. People's participation in forest conservation: consideration and case studies; http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/AC648E/ac648e0i.htm (http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/AC648E/ac648e0i.htm) (Accessed: 20 March 2012 ).

- Smith , BC. 1998 . Participation without power: subterfuge or development? . Community Dev J , 33 ( 3 ) : 197 – 204 .

- Smith , SE , Pyrch , T and Lizardi , AO. 1993 . Participatory action-research for health . World Health Forum , 14 ( 1 ) : 319 – 324 .

- Sobel , J. 2002 . Can we trust social capital? . J Econ Lit , 40 ( 1 ) : 139 – 154 .

- Sunderlin , WD , Anglsen , A , Belcher , B , Burgers , P , Nasi , R , Santos , L and Wunder , S. 2005 . Livelihoods, forests and conservation in developing countries: an overview . World Dev , 33 ( 1 ) : 1383 – 1402 .

- Suzuku , I. 2000 . “ The notion of participation in primary education in Uganada: democracy in school governance ” . In Paper presented at: British Association for International and Comparative Education (BAICE) Conference , Institute of Education, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK . Sep 20, 2009

- Tietjen , K . 2001 . “ Community support for basic education in sub-Saharan Africa ” . In African Region Human Development, Working Paper No. 23072 , Washington , DC : The World Bank .

- United Nations . 1975 . Popular participation in decision making for development , New York , NY : UN Department for Economics and Social Affairs .

- Uphoff , N. 1979 . Feasibility and application of rural development participation: a state-of-the art paper , Ithaca , NY : Rural Development Committee, Centre for International Studies, Cornel University .

- Wallis , M. 1989 . Bureaucracy – its role in third world development , London , UK : Macmillan Publisher Ltd .

- World Bank. 2002. Impact on migration on economic and social development: a review of evidence and emerging issue; Migration&Development-Ratha-GFMD_2010a.pdf http://siteresources.worldbank.org/TOPICS/Resources/2149701288877981391/ (http://siteresources.worldbank.org/TOPICS/Resources/2149701288877981391/) (Accessed: 20 March 2012 ).

- World Bank Participation Sourcebook . 1996 . Environmental Sustainable Development (ESD) publication , Washington , DC : The World Bank .

- Wunder , S. 2001 . Poverty alleviation and tropical forest – what scope for synergies? . World Dev. , 29 ( 11 ) : 1817 – 1833 .