Abstract

We examined the ability to recognise birds of conservation interest among the residents living adjacent to the Serengeti National Park. Data on ability to recognise the photo of eight selected bird species were collected in October 2011, in relation to the respondents' gender, age, tribe and education. Almost all eight species were known by at least 50% of the respondents. The men, older people between 40 and 42 years of age and the Maasai tribe showed good or perfect ability in recognising these birds. Unexpectedly, we found that people with little or no education had greater ability of recognising birds than those who received secondary and/or higher education. Given that only approximately 50% of respondents recognised the selected bird species regardless of age, education, gender and tribe, we emphasise that education programmes on wildlife resources recognition and biodiversity conservation awareness raising activities are to be introduced to communities surrounding the western Serengeti ecosystem. We discuss the results and how to incorporate traditional knowledge into natural resource management, biodiversity conservation and the management of sustainable resource use.

Introduction

A firm understanding of wildlife in communities might lead to improvement of wildlife species conservation. Low public knowledge of wildlife inevitably leads to low conservation due to the fact that some wildlife species will be less known than other species (Clevo & Clem Citation2004). In most cases, wildlife species conservation effort at various categories depends on information generated by the public (Wilson & Tisdell Citation2005). Local people who frequently interact with birds in their local environment may develop a broader knowledge of the life histories, behaviour (breeding period and habitat use), movement and seasonal changes in composition and abundance of those birds (Gichuki Citation1999). Thus, traditional knowledge is increasingly used by academics, agency scientists and policy-makers as a source for ideas on ecosystem management, restoration and conservation biology (Huntington Citation2000). The public's knowledge of birds may therefore influence decisions about bird conservation taken by both governmental and non-governmental organisation conservation programmes.

Knowledge of wildlife species not only enables the public to better understand and benefit from wildlife but may also encourage the public to protect and conserve wildlife, especially threatened species (Wilson & Tisdell Citation2005). In the absence of such knowledge, the public may gain less satisfaction from conserving wildlife because they are unfamiliar with the species being conserved (Wilson & Tisdell Citation2005).

It is likely that the value, both economic and others (consumptive uses; i.e. activities that deplete bird populations, and socio-cultural uses; i.e. activities that provide spiritual or academic fulfilment) that the public place on poorly understood wildlife species is lower than the value they place on more well-known species. However, social-cultural usage of birds might not always be good for conservation; rare species that are not ecologically viable but are important for traditional healing and ceremonies may be exterminated. Increased appreciation of wildlife, especially threatened species, may result in greater support for the conservation of these species and may increase the public's awareness of, and membership in, organisations that help to protect and conserve wildlife (Wilson & Tisdell Citation2005). Community knowledge of local birds is important because birds are the most reliable indicators of terrestrial biological richness and environmental conditions (Bibby Citation1999). Numerous studies have demonstrated the significance of birds as important mobile links in the dynamics of natural and human-dominated ecosystems (Stiles Citation1985; Proctor et al. Citation1996; Levey et al. Citation2002; Mols & Visser Citation2002; Lundberg & Moberg Citation2003; Croll et al. Citation2005). Moreover, locals' knowledge of birds and local bird ecological information has been accepted within the scientific research community as a useful component of impact assessment and conservation monitoring (Huntington Citation2000). Local knowledge of birds has been applied in the development of management plans for various forests and national park reserves among different communities (Gichuki Citation1999).

According to Huntington (Citation2000), traditional ecological knowledge is the knowledge and insight acquired through extensive observation of an area or species by indigenous or other people. Scientists normally select birds of the conservation concern on the basis of scientific knowledge of the protected areas and do not consider the locals' knowledge of these ecosystems. The failure to consider the knowledge of local people may reduce the effectiveness of scientific and local ecological monitoring.

It has previously been found that the ability of local people to identify bird species may vary with gender, age, tribe and education level (Kideghesho et al. Citation2007; Røskaft et al. Citation2007; Sarker & Røskaft Citation2010, Citation2011). It is possible that the age of the individual and the individual's proximity to protected areas affect that individual's knowledge and understanding of birds. This may have implication for the conservation of more well-known species in the area of concern.

The aim of this study was to assess the ability to recognise eight selected bird species among local people living adjacent to the Serengeti National Park in northern Tanzania. An understanding of local peoples' ability to recognise selected bird species may help management authorities to focus on important species in their conservation programmes by including species that are not well known to the people. The following species were selected: ostrich (Struthio camelus), helmeted guinea fowl (Numida meleagris), secretary bird (Sagittarius serpentarius), marabou stork (Leptoptilos crumeniferus), lilac-breasted roller (Coracias caudata), martial eagle (Polemaetus bellicosus), southern ground hornbill (Bucorvus leadbeateri) and kori bustard (Ardeotis kori). We hypothesised that people in the northwest Ngorongoro and western Serengeti districts would be able to recognise these birds because they inhabit villages adjacent to the Serengeti ecosystem, where a variety of birds live. We also hypothesised that the ability to recognise the birds would differ between men and women and with age, education and tribal affiliation. We expected that men would be more knowledgeable in recognising the birds than women because men spend more time hunting in their natural surroundings and that knowledge would increase as a result of age and school education. Finally, we expected the tribes that spend the greatest amount of time in their natural surroundings to be able to recognise the birds better than others and that those who living near the National Park boundary, where the birds are most common, would also have more knowledge. The results from this study and their significance to biodiversity conservation, management and ecosystem services will also be discussed.

Methods

Study area

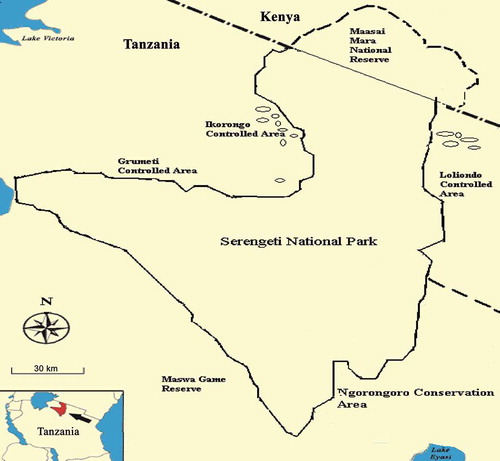

The Serengeti ecosystem is in northern Tanzania near the north-eastern border with Kenya and covers an area of 30,830 km2. The ecosystem lies between 1° 15′ to 3° 30′ S and 34° to 36° E. The Serengeti ecosystem comprises several different conservation areas: the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (8288 km2) and Serengeti National Park (14,763 km2), Open Areas and Game Reserves (Ikorongo (563 km2), Grumeti (416 km2), Maswa (2200 km2), the Ikona Wildlife Management Area (600 km2), the Loliondo Game Controlled Area (4000 km2) and the Maasai Mara Natural Reserve to the north in Kenya ().

Figure 1. Map of the Serengeti ecosystem indicating the protected areas and villages that are contiguous with the Serengeti ecosystem where the survey was conducted. Oval shapes on the map indicate the villages surveyed.

This study was conducted in villages adjacent to the Serengeti ecosystem in north-western Loliondo and the western Serengeti districts (). The ecosystem currently suffers due to conflict between conservationists and local communities (Hofer et al. Citation1996). The conflicts in western Serengeti result from the fact that local people are prohibited from accessing the reserved area to meet their demand for natural resources, such as pasture and water for livestock to sustain their livelihoods (Kideghesho et al. Citation2007).

Study species

The study focused on eight bird species, some of which are of high conservation concern. Some of these species such as guinea fowl, ostrich and kori bustard are hunted for food (Magige et al. Citation2009) and for cultural activities by the tribes that live in the western Serengeti villages (Kaltenborn et al. Citation2003). The helmeted guinea fowl and ostrich are found in almost all habitats of the Serengeti ecosystem, whereas kori bustards are found only in grassland and lightly wooded savannas (Stevenson & Fanshawe Citation2002). Of these eight study species, the ostrich (S. camelus), helmeted guinea fowl (N. meleagris), secretary bird (S. serpentarius) and marabou stork (L. crumeniferus) were expected to be familiar to the study participants because the villagers are hunters and pastoralists who live close to the border of the Serengeti National Park (Kaltenborn et al. Citation2003; Holmern et al. Citation2004). Illegal hunting in the National Park and the presence of these bird species outside of these protected areas when they are in search of food may increase awareness of these species. The other four species, the lilac-breasted roller (C. caudata), the martial eagle (P. bellicosus), the southern ground hornbill (B. leadbeateri) and the kori bustard (A. kori), were assumed to be unknown to the villagers because these birds inhabit the protected areas and are rarely observed outside of these areas. We took photographs of the eight selected bird species in Serengeti National Park and showed them to the village residents to determine their ability to identify the selected bird species.

Data collection with questionnaires

During data collection, some study respondents were unable to recognise the birds by their scientific or vernacular names but were able to recognise them in their local/traditional names. Local translators were recruited from the study area to help translate the names of the birds from scientific/vernacular to local name so that we were able to record a precise response. Questionnaires were prepared in English and later were translated to, and administered in, Kiswahili so that the respondents were easily able to understand the questions.

Data were collected on locals' ability to recognise the eight selected bird species in October 2011. Questionnaires surveys were conducted in 13 villages in north-western Loliondo (near the Loliondo Game Controlled Area) and western Serengeti (near Serengeti National Park), an area with a total population of approximately 30,000 people (United Republic of Tanzania Citation2003). During the research period, a questionnaire survey was conducted in each village making a total of 13 surveys at all 13 villages. Each questionnaire survey had 23 questions and was administered by investigators at respondents' home. Surveys were conducted to 330 individuals through random sampling; respondents were either visited at their homes or were met on the road while investigators were on the way to the homes of respondents of preselected villages. Thus respondents were randomly picked at their homes or whenever seen in the preselected villages. Questionnaires were administered in the following villages; Bwitengi, Kebosongo, Kibeyo, Kisangura, Miseke, Morotonga, Oloipiri, Ololosokwani, Park Nyigoti, Robanda, Soitsambu, Sukenya and Waso, in the Loliondo and Serengeti Districts. The majority of the respondents from these villages belonged to the Maasai, Kurya or Ikoma tribes. A small number of the individuals interviewed belonged to the Luo, Chaga, Jita, Iraq, Mbulu, Meru, Natta, Maragori, Mungurumi, Zanaki, Ikizu, Mwira, Sukuma, Isenye and Sonjo tribes. The questionnaires included questions about the respondent's gender, age, tribe, village of birth, educational level and ability to recognise the selected bird species. The respondent's knowledge of the selected birds was determined using questions that asked whether the respondent knew the names of the birds and whether they had observed the birds.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 19. A non-parametric test (chi-squared test) was used to assess the relationships between gender, tribe and education level and the respondents' ability to recognise the birds. The respondents' knowledge was classified as perfect, good or poor. Those who knew seven to eight birds were considered to have perfect knowledge, those knowing four to six birds were considered to have good knowledge, and those knowing only one to three birds were considered to have poor knowledge (none of the respondents knew zero birds). A parametric test, i.e. an analysis of variance (ANOVA), was used to assess whether respondents' ability to recognise the birds differed in relation to their age or the distance between the respondent's village and the Serengeti National Park boarder. Linear regression analyses were used to identify the respondents' ability to recognise the birds relative to their gender, age and tribe and education level. The ability of those individuals' who were interviewed to recognise the selected birds was assessed using frequency tables expressed as percentages. The Luo, Chaga, Jita, Iraq, Mbulu, Meru, Natta, Maragori, Mungurumi, Zanaki, Ikizu, Mwira, Sukuma and Isenye tribes were combined into a single ‘other tribes’ category due to the small number of respondents from these tribes. However, this category was not used in the linear regression analyses.

Results

Knowledge of individual bird species

Almost all of the selected bird species were known by at least 50% of the respondents (). The lilac-breasted roller was the least-known bird species; only 47.9% of the respondents knew this species. The helmeted guinea fowl was the most commonly known bird, followed by the marabou stork, ostrich, secretary bird, ground hornbill, martial eagle and kori bustard. All respondents stated that they knew the helmeted guinea fowl. Fewer than 5.5% of the respondents stated that they had seen all selected bird species but did not know the name.

Table 1. Percentage of respondents who recognised the species in question, those who did not, or those who had only seen the species (total number of respondents: n = 330)

Knowledge of birds in relation to gender, age, tribe, education and distance from the Park

In all, 56% of the men showed a perfect ability to recognise the selected birds, compared with only 24.7% of the women. Furthermore, 43.8% of the women demonstrated a poor ability to recognise the selected birds. In contrast, only 15.6% of the men demonstrated a poor ability (). Thus, the gender difference in the ability to recognise the selected bird species was highly statistically significant (χ2 = 32.4, df = 2, p < 0.001; ).

Table 2. General ability to recognise all eight species of birds in relation to gender

The respondents who were perfect or good in their ability to recognise the selected birds were significantly older than those who showed only poor ability (ANOVA; F = 7.118, df = 2, p < 0.001; ).

Table 3. Mean age of respondents with different levels of recognising the eight selected birds in the Serengeti ecosystem

The Maasai tribe demonstrated the best ability to recognise the eight selected bird species, followed by the Ikoma and Sonjo tribes. The Kurya tribe had the poorest ability to recognise the selected bird species (χ2 = 117.1, df = 8, p < 0.001; ).

Table 4. General knowledge of the eight selected birds according to tribe and education level

The respondents who had no education demonstrated better ability (not statistically significant) to recognise the eight selected bird species than the respondents who had attended school (χ2 = 5.70, df = 4, NS; ).

The respondents who lived the furthest away from the park had a better ability to recognise the selected bird species than those who lived in close proximity to the park (ANOVA; F = 19.4, p < 0.001; ).

Table 5. General ability to recognise the birds in relation to village distance from the Park boundary

Knowledge of all bird species

A linear regression analysis that used the respondent's ability to recognise birds as the dependent variable and gender, age, tribe (excluding the pooled ‘other tribe’ group), village distance from the Park boundary and educational level as the independent variables explained 27% of the total variation in knowledge. All of the variables except the distance to the Park boundary and educational level contributed significantly to this variation (r 2 = 0.266, df = 5, p < 0.001; ).

Table 6. The results of a linear regression analysis with general ability to recognise eight selected birds as the dependent variable (excluding the pooled ‘other tribe’ group)

Discussion

Knowledge of individual bird species

Overall, the respondents were highly capable of recognising the eight selected birds species. The guinea fowl was the best-known species, whereas the kori bustard and the lilac-breasted roller were the least known. The fact that more than 50% of the respondents were able to recognise these birds species might be a result of the distribution of these species, which are common and widespread in a variety of habitats including open grassland, wooded grassland, woodlands and forests (Stevenson & Fanshawe Citation2002). Because these habitats are near the villages surveyed, these birds are easily observed and thus are familiar to the respondents. The helmeted guinea fowl was the best-known species (96.4%) by all respondents, potentially because these birds are common in cultivated areas, where they feed on cereals during the harvesting season and farmers can see them frequently. The proximity of the study villages to Serengeti National Park might also be the reason that guinea fowl are well known. It is probable that human knowledge towards recognising animals is influenced by direct and indirect selection pressures (Herzog & Burghardt Citation1988). Direct pressures result from human evolutionary coexistence with animals, whereas indirect pressures are anthropomorphic generalisations of responses that originally evolved towards other people (Herzog & Burghardt Citation1988).

The previous assumption that the lilac-breasted roller was not well known to the people proved to be incorrect. Roughly 50% of all respondents knew this species. This familiarity might be due to the bird's habit of occupying communal or cultivated lands, especially during the season when the farmers burn the land to prepare for cultivation by setting fires. During this season, many insects take flight to escape the fires and become an available food source for the lilac-breasted roller. The martial eagle was also well known (70.3%). This species plays an important role in the ecosystem as an efficient scavenger and has been associated with migratory wild animals during the dry season. It travels to the communal land to seek wild and domestic animals carcasses for food. This type of scavenging behaviour might make the bird better known among residents.

Knowledge of birds in relation to gender, age, education, tribe and distance from the National Park

The gender-related difference in respondents' ability to recognise birds was highly significant. This finding supported our hypothesis that the men would be more knowledgeable than the women in identifying the selected bird species.

This result was consistent with finding from Huxham et al. (Citation2006) who found that young men had significantly greater wildlife knowledge than young women. The different roles that exist between men and women, particularly among the Maasai, likely contributed to ability of men to recognise birds as was also suggested by Røskaft et al. (Citation2003, 2004). In the western Serengeti, wildlife hunting has been an integral part of life for centuries (Magige et al. Citation2009; Holmern Citation2010). Men's illegal access to the Serengeti National Park for hunting (Bitanyi et al. Citation2012) where these birds exist potentially allow them to see and identify birds more readily than women, who are not hunters. Several researchers have identified significant gender differences in animals' identification (Kideghesho et al. Citation2007; Røskaft et al. Citation2007; Sarker & Røskaft Citation2010). The ability to recognise animals has further been tested by Setalaphruk and Price (Citation2007) who found that young men were able to list 81 animals compared to young women who listed only 45 animals. The study suggested further that young men were able to provide more animal names because they spent more time wandering around the village and playing outside compared to young women. It is likely that the most significant difference in men and women's ability to recognise birds may stem from their different roles in outdoor activities (Røskaft et al. Citation2004).

It is likely that older respondents were able to identify and name the selected birds more accurately because they resided in the area for a longer period of time (Papworth et al. Citation2009). Various tribes in the Serengeti ecosystem use birds as a vital part of their diet (Magige et al. Citation2009), which might contribute to older people's knowledge and ability to recognise birds because of their extensive hunting experience (Huxham et al. Citation2006). It has been explained that local knowledge results from experience (Papworth et al. Citation2009) and is orally transmitted, cumulative and builds on the experiences of past and present generations through mentoring, storytelling and cooperative work (MacGregor Citation2000). However, some studies have also found that younger people, including school pupils, had a better ability to recognise birds than older pupils (Beck et al. Citation2001; Prokop et al. Citation2008). Bogner (Citation1999) examined the effects of conservation programmes on 10- to 16-year-old students' attitudes about and knowledge of the common swift (Apus apus) and found that specific knowledge about the common swift increased only in younger students. A similar study of bird identification skills with visual stimuli (bird pictures) conducted with elementary students (mean age 12.3 years) and university students (mean age 21.2 years) found that the ability to identify birds did not differ significantly between the two groups (Prokop & Rodak Citation2009; Randler Citation2009). Surprisingly, we found that the ability to recognise birds accurately was not positively related to education level. Interestingly, uneducated respondents had a perfect ability to identify birds more frequently than educated respondents. However, the effect of education was not present in the multivariate analysis because the educational level of the Maasai people was generally lower, but they were found to have the highest general ability to recognise birds (see next section).

The Maasai tribe was the best at recognising the eight selected bird species. However, the Maasai people are not wildlife hunters and are often viewed as pastoralist and nomadic, i.e. they follow their herds to better grazing lands and water. Such a lifestyle might improve their opportunities to see and become familiar with a number of bird species. The behaviour of various bird species is frequently used by Maasai elders to predict the weather. For example, if ground hornbills make an unusual ‘hoohoohoo’ sound and ostriches make roaring sounds, the beginning of the rainy season is thought to be near. If guinea fowl stop moving after a signal from their leader and make a special sound, the rainy season is about to begin (Indigenous Knowledge Citation2005). The use of bird signs as an indicator of the weather might increase Maasai people's ability to recognise different bird species.

In Tanzania, bush meat (meat obtained by killing wild animals) is an important source of protein and cash income (Barnett Citation2000). The Ikoma tribe is traditionally a hunting tribe, collecting eggs from game birds (Magige et al. Citation2009). This tradition might explain this tribe's relatively strong ability to identify the selected birds. The Sonjo tribe also had an almost perfect ability to recognise birds; however, this does not give a clear picture of their ability to recognise birds compared to other tribes because of the small number of respondents. The men of the Sonjo tribe are hunters, wild honey gatherers and agro-pastoralists which might explain their ability to recognise birds (Potkanski & Adams Citation1998). In contrast, respondents belonging to the Kurya tribe had the poorest ability to recognise the birds which is likely due to the fact that many Kurya people are exclusively farmers.

Respondents who lived in the villages furthest from the Park were better at recognising the selected bird species than those who lived closer distances to the park. However, the effect of distance was not present in the multivariate analysis. This might be due to the nomadic and pastoralist nature of the Maasai living up to 70 km from the park and the farming habit of the Kurya (living very close to the park) which might influence their ability to recognise selected bird species.

People's knowledge of birds in relation to biodiversity, ecosystem services and management

Some bird species which are currently in decline are characterised by naturally fluctuating populations (Willis et al. Citation2007). Current conservation initiatives pay substantial attention to identify those species that are mostly threatened by extinction (International Union for Conservation of Nature Citation2004), while little consideration is paid to other more common species. Human-induced activities continue to change the environment on both local and global levels, leading to dramatic changes in the biotic structure and composition of ecological communities (Hooper et al. Citation2005). Such activities frequently cause declines in biodiversity that affect ecosystem functioning and yield (Russell Citation1989; Daily Citation1997). Local knowledge of birds of conservation interest and their importance to the Serengeti ecosystem is important for successful conservation and might lead to increased conservation efforts and reduction in activities that jeopardise these species or at least important prerequisite for successful conservation. This idea is supported by research from Wilson and Tisdell (Citation2005) who showed that poor public knowledge of bird species is likely to result in less support for their conservation compared to more common and better known bird species. Inadequate support might jeopardise the survival of species that are harvested for household food (Magige et al. Citation2009). Thus, the ability to recognise birds is a prerequisite for protecting birds of conservation interest, even if this alone is not sufficient or the only important issue.

Due to agricultural expansion and habitat fragmentation in the study areas adjacent to Serengeti National Park, the population of birds of conservation interest might decline. These birds appear in these areas during the farming season when food is readily available. Some bird species are vulnerable because they are crop pests (guinea fowl), while others hunt for domestic chickens, goats and lambs (Martial eagle). The application of pesticides during the farming period might also be dangerous to birds, including populations of many farmland birds (Donald et al. Citation2001).

As interest increase in incorporating traditional knowledge into natural resource management and biodiversity conservation (Gadgill et al. Citation1993; Horowitz Citation1998; Johannes Citation1998; Ramakrishnan et al. Citation1998; Nabhan Citation2000), the management of ecological processes (Alcorn and Toledo Citation1998), and general sustainable resource use in (Schmink et al. Citation1992; Berkes Citation1999), special effort must be made by management authorities to involve local people's understanding of various conservation programmes that play a role in biodiversity conservation in different localities. Given the results of this study, it is important for biodiversity conservation in Serengeti ecosystem, that management authorities involve education agenda/programmes to schools and local people when developing conservation programmes.

Local people in the Serengeti ecosystem might possess a broad knowledge base that has been accumulated through observations and transmitted from generation to generation. Huxham et al. (Citation2006) showed that school children rely on a culturally mediated source of information for knowledge on the existence of wildlife. Thus, local people in the Serengeti ecosystem may see biological diversity as a crucial factor in generating the ecological services and natural resources on which they depend (Gadgill et al. Citation1993). These services include birds' pollination, seed dispersal and controlling of outbreaks of insect pests (Berkes et al. Citation2000). Populations by seed-dispersing birds are also of importance for the renewal of surrounding ecosystems (Gadgill et al. Citation1993).

The ability to recognise different species of birds by local people surrounding Serengeti National Park is important because once they know these species it may be easier for them to understand their status and whether they need protection. This understanding may lead management authorities to include the species that have been identified as needing protection when developing conservation programmes. For example, our findings showed that the Kurya tribe was least able to recognise the birds in our study. Tribes close to protected areas are often wildlife hunters including selected birds for household food (except for the Maasai), rituals and ceremonial events (Magige et al. Citation2009). They are very aware of the bird species occurring in their area (in this paper) but may not have knowledge of conservation status of the different bird species. The fact that some tribes, such as Kurya, possess little knowledge of the selected birds and their conservation status may have serious impacts on the conservation of these species. There is, therefore, a need of promoting wider understanding of the importance of birds in relation to biodiversity conservation. There is also a need of raising awareness of the Kurya tribe about the importance of not killing birds during farming activities as most of these birds feed on planted seeds.

Conclusions and recommendations

The aim of this study was to investigate villagers' knowledge of eight selected bird species of conservation interest in villages adjacent to the Serengeti ecosystem. The results indicated that the majority of people interviewed had good knowledge of local birds. However, the knowledge of birds of conservation interest varied with the respondents' gender, age and tribe. Though all of the selected bird species were common in the areas of the Park near the villages in northern Loliondo and western Serengeti, the public's knowledge of certain species was poor. The most important criteria associated with the ability to recognise the selected bird species were gender (men knew more about the species than women), age (older people could identify more species) and tribe (the Maasai were the best at recognising the birds). These results indicate that among the people living adjacent to the park, experiencing bush life (wild environment) is the most important factor for developing such ability. Given that there has been increasing interest in incorporating traditional knowledge into natural resource management, biodiversity conservation and sustainable resource use, community integration must play an important role in natural resource management and conservation, taking into account individuals' gender, age and education. The results draw attention to the need for public education, especially about species that are of conservation status and/or are threatened with extinction.

We further recommend that education programmes be introduced among the communities living close to the Serengeti National Park to increase awareness and bird identification skills. Our results may help to guide the development of education programmes, allowing for a design that fits particular groups. The education programmes should include learning to recognise bird species, the conservation status of the species, threats to the species and how to mitigate the threats. These programmes should involve knowledge of biodiversity conservation as an important long-term survival tool for the wildlife. These programmes should also include bringing wildlife conservation and management into primary and secondary school curricula and the creating of wildlife information centres in villages.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere thanks to the Government of Norway for their financial support, without which this study would not have been possible. We are very grateful to Dr. Robert Fyumagwa, Director of the Serengeti Wildlife Research Centre, for logistic support and to Mr. Noel Massawe for field assistance during the questionnaire survey. Thanks are also due to the Director General of TAWIRI, Dr. Simon Mduma, for granting permission to conduct such a unique type of study. Finally, we want to acknowledge two anonymous reviewers whose comments improved this paper.

References

- Alcorn , JB and Toledo , VM. 1998 . “ Resilient resource management in Mexico's forest ecosystems: the contribution of property rights ” . In Linking social and ecological systems: management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience , Edited by: Berkes , F and Folke , C . 216 – 249 . Cambridge , UK : Cambridge University Press .

- Barnett , R. 2000 . Food for thought: the utilization of wild meat in eastern and southern Africa. Trade Review , 264 Nairobi : TRAFFIC/WWF/IUCN .

- Beck , AM , Melson , GF , da Costa , PL and Liu , T. 2001 . The educational benefits of a ten-week home-based wild bird feeding program for children . Anthrozoös. , 14 : 19 – 28 .

- Berkes , F. 1999 . Sacred ecology. Traditional ecological knowledge and resource management , Philadelphia (PA) and London : Taylor and Francis .

- Berkes , F , Colding , J and Folke , C. 2000 . Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management . Ecol Appl. , 10 ( 5 ) : 1251 – 1262 .

- Bibby , CJ. 1999 . Making the most of birds as environmental indicators . Ostrich. , 70 : 81 – 88 .

- Bitanyi , S , Nesje , M , Kusiluka , LJM , Chenyambuga , SW and Kaltenborn , BP. 2012 . Awareness and perceptions of local people about wildlife hunting in western Serengeti communities . Trop Conserv Sci. , 5 ( 2 ) : 208 – 224 .

- Bogner , FX. 1999 . Empirical evaluation of an educational conservation programme introduced in Swiss secondary schools . Int J Sci Educ. , 21 : 1169 – 1185 .

- Clevo , W and Clem , T. 2004 . What role does knowledge of wildlife play in providing support for species' conservation? Working Papers in Economics, Ecology and the Environment , 10 The University of Queensland School of Economics, St Lucia, QLD .

- Croll , DA , Maron , JL , Estes , JA , Danner , EM and Byrd , GV. 2005 . Introduced predators transform subarctic islands from grassland to tundra . Science. , 307 ( 5717 ) : 1959 – 1961 .

- Daily , GC. 1997 . Nature's services: social dependence on natural ecosystems , Washington , DC : Island Press .

- Donald , PF , Green , RE and Heath , MF. 2001 . Agricultural intensification and the collapse of Europe's farmland bird populations . Proc R Soc Lond, B Biol Sci. , 268 : 25 – 29 .

- Gadgill , M , Berkes , F and Folke , G. 1993 . Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. AMBIO , 22 ( 2–3 ) : 151 – 156 .

- Gichuki , FN. 1999 . Threats and opportunities for mountain area development in Kenya . AMBIO. , 28 ( 5 ) : 430 – 435 .

- Herzog , H and Burghardt , GM. 1988 . Attitudes toward animals: origins and diversity . Anthrozoös. , 1 : 214 – 222 .

- Hofer , H , Campbell , KLI , East , ML and Huish , SA. 1996 . “ The impact of game meat hunting on target and non-target species in the Serengeti ” . In The exploitation of mammal populations , Edited by: Taylor , J and Dunstone , N . 117 – 146 . London : Chapman and Hall .

- Holmern , T. 2010 . “ Bushmeat hunting in Western Serengeti: implications for community-based conservation ” . In Conservation of natural resources: some African & Asian examples , Edited by: Gereta , E and Røskaft , E . 211 – 236 . Trondheim : Tapir Academic Press .

- Holmern , T , Johannesen , AB , Mbaruka , J , Mkama , SY , Muya , J and Røskaft , E. 2004 . Human–wildlife conflicts and hunting in the western Serengeti , 26 Tanzania : NINA Project Report Trondheim. Norway: Norwegian Institute of Nature Research. 26th issue .

- Hooper , DU , Chapin , FS , Ewel , JJ , Hector , A , Inchaust , P , Lavorel , S , Lawton , JH , Lodge , DM , Loreau , M Naeem , S . 2005 . Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge . Ecol Monogr. , 75 ( 1 ) : 3 – 35 .

- Horowitz , LS. 1998 . Integrating indigenous resource management with wildlife conservation: a case study of Batang Ai National Park, Sarawak, Malaysia . Human Ecol. , 26 : 371 – 404 .

- Huntington , HP. 2000 . Using traditional ecological knowledge in science: methods and applications . Ecol Appl. , 10 ( 5 ) : 1270 – 1274 .

- Huxham , M , Welsh , A , Berry , A and Templeton , S. 2006 . Factors influencing primary school children's knowledge of wildlife . J Biol Educ. , 41 ( 1 ) : 9 – 12 .

- 2005 . “ Indigenous knowledge in disaster management in Africa ” . In United Nations Environment Programme, Indigenous Knowledge in Africa, UNEP , 117 Nairobi : UNEP .

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2004. IUCN red list of threatened species [Internet]. [cited 2011 Nov 10]. www.redlist.org (http://www.redlist.org)

- Johannes , RE. 1998 . The case for data-less marine resource management: examples from tropical nearshore finfisheries . Trends Ecol Evol. , 13 : 243 – 246 .

- Kaltenborn , BP , Nyahongo , JW and Mayengo , M. 2003 . People and wildlife interactions around Serengeti National Park , 31 Tanzania : Biodiversity and the human–wildlife interface in Serengeti, Tanzania. Trondheim: NINA .

- Kideghesho , JR , Røskaft , E and Kaltenborn , BP. 2007 . Factors influencing conservation attitudes of local people in Western Serengeti, Tanzania . Biodiv Conserv. , 16 ( 7 ) : 2213 – 2230 .

- Levey , DJ , Silva , WR and Galetti , M , eds. 2002 . Seed dispersal and frugivory: ecology, evolution and conservation , Rio Quente : CABI Publications .

- Lundberg , J and Moberg , F. 2003 . Mobile link organisms and ecosystem functioning: implications for ecosystem resilience and management . Ecosystems. , 6 ( 1 ) : 87 – 98 .

- MacGregor , D. 2000 . “ The state of traditional ecological knowledge research in Canada: a critique of current theory and practice ” . In Expressions in Canadian native studies , Edited by: Laliberte , R , Settee , P , Waldram , J , Innes , R , Macdougall , B , McBain , L and Barron , F . 436 – 458 . Saskatoon : University of Saskatchewan Extension Press .

- Magige , FJ , Holmern , T , Stokke , S , Mlingwa , C and Røskaft , E. 2009 . Does illegal hunting affect density and behaviour of African grassland birds? A case study on ostrich (Struthio camelus) . Biodiv Conserv. , 18 ( 5 ) : 1361 – 1373 .

- Mols , CMM and Visser , ME. 2002 . Great tits can reduce caterpillar damage in apple orchards . J Appl Ecol. , 39 ( 6 ) : 888 – 899 .

- Nabhan , GP. 2000 . Interspecific relationship affecting endangered species recognized by O'odham and Comcáac cultures . Ecol Appl. , 10 : 1288 – 1295 .

- Papworth , SK , Rist , J , Coad , L and Milner-Gulland , EJ. 2009 . Evidence for shifting baseline syndrome in conservation . Conserv Lett. , 2 ( 2 ) : 93 – 100 .

- Potkanski , R and Adams , WM. 1998 . Water scarcity, property regimes and irrigation management in Sonjo, Tanzania . J Develop Stud. , 34 ( 4 ) : 86 – 116 .

- Proctor , M , Yeo , P and Lack , A. 1996 . The natural history of pollination , Portland , OR : Timber Press .

- Prokop , P , Prokop , M and Tunnicliffe , SD. 2008 . Effects of keeping animals as pets on children's concepts of vertebrates and invertebrates . Int J Sci Educ. , 30 ( 4 ) : 431 – 449 .

- Prokop , P and Rodak , R. 2009 . Ability of Slovakian students to identify birds . Euras J Math Sci Tech Educ. , 5 ( 2 ) : 127 – 133 .

- Ramakrishnan , PS , Saxena , KG and Chandrashekara , UM , eds. 1998 . Conserving the sacred for biodiversity management , New Delhi : Oxford & IBH Publishing Co .

- Randler , C. 2009 . Learning about bird species on the primary level . J Sci Educ Technol. , 18 ( 2 ) : 138 – 145 .

- Russell , EP. 1989 . Enemies hypothesis: a review of the effect of vegetational diversity on predatory insects and parasitoids . Environ Entomol. , 18 : 590 – 599 .

- Røskaft , E , Bjerke , T , Kaltenborn , BP , Linnell , JDC and Andersen , R. 2003 . Patterns of self-reported fear towards large carnivores among the Norwegian public . Evol Hum Behav. , 24 ( 3 ) : 184 – 198 .

- Røskaft , E , Hagen , ML , Hagen , TL and Moksnes , A. 2004 . Patterns of outdoor recreation activities among Norwegians: an evolutionary approach . Ann Zool Fennici. , 41 ( 5 ) : 609 – 618 .

- Røskaft , E , Händel , B , Bjerke , T and Kaltenborn , BP. 2007 . Human attitudes towards large carnivores in Norway . Wildl Biol. , 13 ( 2 ) : 172 – 185 .

- Sarker , AHMR and Røskaft , E. 2010 . Human attitudes towards conservation of Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) in Bangladesh . Int J Biod Conserv. , 2 ( 10 ) : 316 – 327 .

- Sarker , AHMR and Røskaft , E. 2011 . Human attitudes towards the conservation of protected areas: a case study from four protected areas in Bangladesh . Oryx. , 45 ( 3 ) : 391 – 400 . doi: 310.1017/S0030605310001067

- Schmink , M , Redford , KH and Padoch , C. 1992 . “ Traditional peoples and the biosphere: framing the issues and defining the terms ” . In Conservation of neotropical forests: working from traditional resource use , Edited by: Redford , KH and Padoch , C . 3 – 13 . New York , NY : Columbia University Press .

- Setalaphruk , C, Price LL . 2007 . Children's traditional ecological knowledge of wild food resources: a case study in a rural village in Northeast Thailand . J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. , 33 ( 3 ) doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1183-1133

- Stevenson , T and Fanshawe , J. 2002 . Field guide to the birds of East Africa , London : T & A Poyser Ltd .

- Stiles , FG. 1985 . “ On the role of birds in the dynamics of neotropical forests ” . In Conservation of tropical forest birds , Edited by: Diamond , AW and Lovejoy , TE . 49 – 59 . London : International Council for Bird Preservation .

- United Republic of Tanzania . 2003 . Population and housing censuses. Bureau of Statistics PsOPC , Dar es Salaam : United Republic of Tanzania, Government Printer .

- Willis , KJ , Araújo , MB , Bennett , KD , Figueroa-Rangel , B , Froyd , CA and Myers , N. 2007 . How can a knowledge of the past help to conserve the future? Biodiversity conservation and the relevance of long-term ecological studies . Philos Trans Roy Soc B. , 362 : 175 – 186 .

- Wilson , C and Tisdell , C. 2005 . Knowledge of birds and willingness to support their conservation: an Australian case study . Bird Conserv Int. , 15 ( 3 ) : 225 – 235 .