Abstract

Bamboo is one of the most important non-timber forest products in Bangladesh. Previous research, however, has focused mainly on its silvicultural aspects, with its socio-economic aspects remaining underexplored. In a study conducted between January and March in 2008, we surveyed 30 randomly selected bamboo-based entrepreneurs in a regional market in southern Bangladesh to identify employment and trade patterns, financial contributions, and marketing of bamboo and its products. Bamboo was found to be important in generating profits for entrepreneurs and employment for low-skilled rural workers. Bambusa balcooa, Melocanna baccifera, Bambusa tulda, and Bambusa vulgaris were found to be the most traded species, with Bambusa balcooa constituting 39% of the market. Major uses of (secondary products from) bamboo were found to be construction, fences, mats, and domestic baskets and utensils. Operating costs varied across the enterprises according to their sales, workforce size, and purchases. Estimated net average incomes of the large, medium, and small enterprises were around Tk. 43,000 ($625), Tk. 30,000 ($435), and Tk. 19,300 ($280), respectively, during the year 2007. Medium-sized enterprises earned the most (32%) from the sale of secondary products. Three marketing channels were identified, with most of the bamboo in the area being found to be collected through intermediaries. Our discussion highlights the importance of bamboo and its secondary products in generating employment and profits in the area and also the presence of problems such as income variability throughout the year. Promoting the trade of bamboo and bamboo-based enterprises through appropriate technical and financial assistance to growers and entrepreneurs could be an effective strategy to improve local economies in Bangladesh.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, bamboo has been increasingly recognized as one of the major non-timber forest products (NTFPs) of the world (Wong Citation2004). In fact, with more than 1500 documented uses and with about 1200 species, it is one of the most useful and economically important NTFPs (Lobovikov et al. Citation2007). This species of grass belongs to the family Graminae and is distributed naturally across the tropics and subtropics (Lobovikov et al. Citation2007; Qing et al. Citation2008). Worldwide, approximately 2.5 billion people benefit directly or indirectly from the trade and consumption of bamboo (International Network for Bamboo and Rattan Citation1999; Yuming et al. Citation2004). In many parts of the world, bamboo still forms an essential part of the livelihoods and cultures of tribal and rural communities by being the primary source of housing material, food, agricultural implements, and domestic utensils (Vantomme et al. Citation2002; Yuming et al. Citation2004).

Globally, in the last few years, commercialization of NTFPs has increased income and employment opportunities, especially for poor and otherwise disadvantaged people (Belcher & Schreckenberg Citation2007). In developing countries, the production and trade of bamboo has been increasingly recognized as a potential tool for poverty alleviation amongst marginal or low-income people (Ruiz Pérez et al. Citation1999). According to the International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (Citation1999), worldwide domestic trade and subsistence use of bamboo is worth about US$ 4.5 billion per annum, with another US$ 2.7 billion generated from its export. In Asia, with around 1000 bamboo species grown naturally, bamboo industries are now thriving (Lobovikov et al. Citation2007). In China, for example, bamboo is a valuable raw material for its booming NTFPs industry, which has stimulated regional economies and has generated employment opportunities for thousands of semi-skilled laborers (Ruiz Pérez et al. Citation1999).

In Bangladesh, bamboo, also called ‘poor man's timber’, has played a central role in regional NTFP markets (Khan & Khan Citation1994). Between 1981 and 2000, the gross annual domestic consumption of bamboo was about 700 million culms, corresponding to almost one million tons (Lobovikov et al. Citation2007). Bamboo is also the major raw material for about 45,000 small-scale cottage enterprises in the country (Banik Citation1998). Thirty-three bamboo species, with 18 occurring naturally, have been reported from the country (Banik Citation1998; Bystriakova et al. Citation2003). Only a few of these species, however, are socio-economically important and many are limited by their distribution. In the country, bamboo is available both from forest and non-forest areas and can be categorized into forest bamboos and village bamboos based on their primary collection source. Despite bamboo's widespread use in Bangladesh, previous research mainly concentrated on silvicultural or managerial aspects of bamboo rather than its socio-economic significance, especially in relation to trade patterns and financial prospects (c.f. Banik Citation1988; Miah et al. Citation2002; Kamruzzaman et al. Citation2008; Rana et al. Citation2010). With such a backdrop, the present study was designed to better understand the social and financial attributes of bamboo trade and marketing patterns in a regional market of southern Bangladesh. The study could serve as a baseline for future and in-depth socio-economic studies on bamboo-based enterprises and livelihoods. The organization of this paper is as follows. First, there is a brief description of the method used for data collection and analysis. Then there is a presentation of findings about the nature of employment and wages, how bamboo is used and which species are most important, the profitability of bamboo and bamboo-based enterprises, and how bamboo is collected and marketed. There is then a discussion of our findings, followed by concluding comments about the way in which this study can be used and recommendations for the focus of development initiatives.

The study site

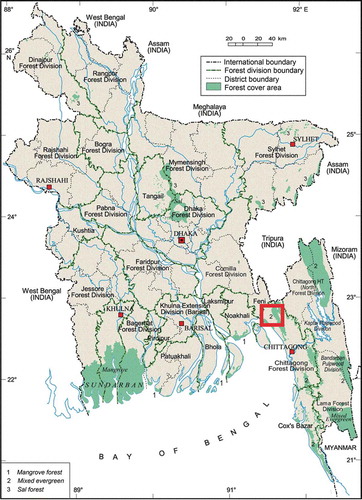

The study was performed in Baroia Hat Pouroshova (the local term for ‘metropolis’) under Mirsharai upazila Footnote 1 of the Chittagong division, in southern Bangladesh (). The area is located between 22°40′–22°58′ N and 91°25′–91°40′ E in an important strategic focal point and is bounded by Tripura state in India and the Feni district to the north, Sitakunda upazila to the south, Fatikchari upazila to the east, and Sonagazi (Noakhali) upazila to the west. The only hilly range of the country to the northern and eastern sides of this area extended up to Chittagong and the Chittagong Hill Tracts. This is an old and established bamboo market, which acts as a hub for major bamboo-producing districts of the southern region of the country. The area is a major supply source of bamboo and related products to adjacent districts because of the relatively cheap price attributable to year-round supply of bamboo from nearby upstream hilly forest areas and from the local homesteads. The market spreads along a quarter kilometer of the Dhaka-Chittagong main highway and is easily accessible from any part of the country.

Methods

Fieldwork for the study was conducted during January–March, 2008. An entrepreneur was defined as a person who owns a bamboo-based enterprise who buys bamboo and resells it either in its raw form as bamboo culms/poles or as manufactured secondary products. Entrepreneurs were identified randomly from the market through a preliminary field survey. Thirty entrepreneurs (n = 30), corresponding to about 25% of the total sample population (N = 122), were selected randomly, regardless of the volume of their business and regardless of their involvement with that business in terms of number of years of participation. Entrepreneurs were interviewed personally, maintaining an informal schedule, and each interview took place during the day between 9.30 a.m. and 5.00 p.m. in places convenient to the respondent, this generally being their place of business. Each interview took a minimum of 30 minutes to a maximum of 2 hours based on the availability of the entrepreneurs for the survey. Additionally, to gain insight into the overall bamboo market in the area and the prospects and challenges faced by the entrepreneurs, two focus group discussions involving local and influential entrepreneurs were organized. For convenience of data analysis based on annual profits from the sale of bamboo and bamboo-based manufactured products, enterprises were later categorized into three distinct classes: ‘large’ – income above Tk.Footnote 2 135,000 ($1942) year−1; ‘medium’ – income of Tk. 80,000 ($1151)–135,000 ($1942) year−1, and ‘small’ – income below Tk. 80,000 ($1151) year−1.

We used a semi-structured questionnaire to collect information on basic demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the entrepreneurs, financial information for the year 2007, supply and sources of bamboo, manufactured products, marketing patterns, status of workers (i.e., the people who worked in the local bamboo shop on either a permanent or temporary basis), and available government and non-government organization (NGO) support.

All qualitative and quantitative data were collected in local terms and units. The approximated incomes of the local bamboo-based enterprises for the year 2007 were estimated through careful questioning of the entrepreneurs. All comparisons were made in terms of monetary value. The total input (purchase of raw products, transportation, wages of the workers, an allowance towards self-labor, fixed costs like permanent structures, depreciation costs, rent and bills, taxes on incomes and, where applicable, interest on loans) and output (sale of primary and secondary value-added products) values were adjusted at 2008 prices. The production costs of the bamboo-based products were determined from the average value of total inputs required (excluding wages of workers and factory running costs). For quantitative data, descriptive statistics were used to interpret the key findings.

Results

Entrepreneurs and the work force

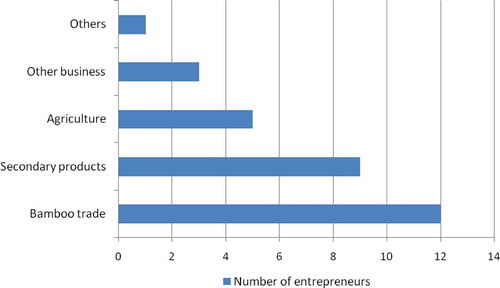

All the entrepreneurs were male with the majority of them (53.3%) being younger than 41–50 years (). Literacy rates among the entrepreneurs were high; most had primary school educations (43.3%), followed by junior secondary school (33.3%) and secondary school or above (20%). Most of the entrepreneurs were engaged in their profession for more than 10 years, following on from their predecessor (). The trade of bamboo was the primary earning source for about 40% of the entrepreneurs (12 out of 30), whereas the trade of bamboo-based secondary products was the primary earning source for about 30% of the entrepreneurs (9 out of 30) (). Other major income-generating occupations among the entrepreneurs were agriculture (5; 16.7%) and other small businesses (3; 10%).

Table 1. Profile of the interviewed entrepreneurs and workers

In the 30 factories that were surveyed, there were 198 workers altogether. Among the workers, 52% were working temporarily on a per day wage basis and 48% were paid a monthly salary and were permanently employed in the factories. The majority of the workers were adult males (84.4%), in the age bracket of 31–40 years, with a literacy rate of 52.5% (i.e., education in primary school or above). There were two types of workers in the industry: artisans (locally termed as karigar) who manufactured the bamboo-based secondary products and laborers whose main responsibility was to provide physical labor. The average number of workers in the large, medium, and small factories was 8.6 (artisan, 33.3%), 6.17 (artisan, 34.23%), and 4.5 (artisan, 27.78%) persons, respectively. All the children (2.5%) and female (15.6%) laborers work temporarily employed. Women and children also received lower wages than did adult male laborers (the daily wage rate of adult males, women, and children during the study period were Tk. 120, Tk. 80, and Tk. 60 respectively).

Utilization of bamboo and secondary products

Four species of bamboo () were traded locally in the market, either in unprocessed form as bamboo poles/culms or for manufacturing secondary bamboo-based products. B. balcoa was the most traded species (29%; market value Tk. 322,245 during 2007) followed by M. baccifera, B. tulda, and B. vulgaris (market value Tk. 223,092.5, Tk. 190,040, and Tk. 90,890, respectively). The total shares of B. balcoa, B. tulda, B. baccifera, and B. vulgaris were 39, 27, 23, and 11%, respectively, in terms of market value during the year 2007. B. balcoa was traded primarily in unprocessed form and was reported as being popular for use as scaffolding during building construction and for making the framework of roof casting (). The major use of the other three species of M. baccifera, B.tulda, and B. vulgaris were making fences, mats, and domestic baskets and utensils ( and ). Apart from B. balcoa, M. baccifera was also sold in unprocessed form. The market price of B. balcoa and M. baccifera culms varied considerably in terms of maturity and quality (i.e., usable length, thickness, and color) of the culms. The usual price of a single B. balcoa culm in the local market was Tk. 150–200 compared with its purchase value from intermediaries of between Tk. 80 and 110, whereas M. baccifera was sold at a price of Tk. 500–750 (100 culms) with a purchase value ranging between Tk. 300 and Tk. 425. Prices were also subject to change according to seasonal demand and product availability, where the peak season is between October and April with the initiation of the construction period during winter and the off-peak season is between May and September.

Table 2. Bamboo species used in the local market

A list of articles produced from different bamboo species with their trade names, common uses, production costs, and prices in the different markets is given in . Bamboo mats and fences are the two most popular and traded articles available at different sizes. The prices of entire articles were found to depend primarily on the time and expertise required by artisans followed by the amount of bamboo and other raw materials used to manufacture those products.

Table 3. Bamboo-based articles (secondary products) and prices on the local market

Profiting from bamboo-based enterprises

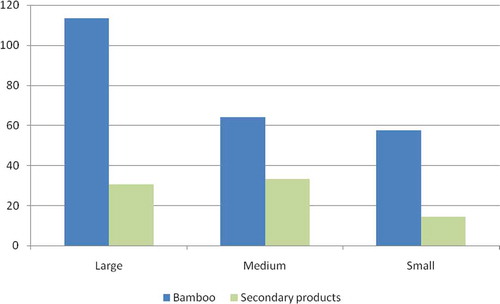

Based on our financial calculations focusing on the amount of total cash earned from selling of bamboo and bamboo-based secondary products, the numbers of enterprises falling within the large, medium, and small categories were 8, 18, and 4, respectively. The financial information about the enterprises for the year 2007 is summarized in . The estimated net profit/earnings of large, medium, and small enterprises during 2007 were Tk. 41,565, Tk. 26,540, and Tk. 22,215, respectively. Only three of the surveyed enterprises had a self-owned permanent structure as the place of doing business, whereas the other entrepreneurs rented space from others to run their businesses. Most of the inputs into the surveyed enterprises were used for purchasing unprocessed bamboo for further sale and processing (50–53%) followed by payment of wages/salaries to the workers employed in the corresponding enterprises (37–41%). The pattern of earnings from primary and secondary products varied across different enterprise categories (). The medium-sized enterprises, however, earned on average the most from the selling of secondary or manufactured products (Tk. 35,942; 32% of total income). The net contribution of earning from bamboo-based enterprise to entrepreneurs' gross annual incomes (i.e., the sum of income from both bamboo and non-bamboo-based activities) was around 61–80% to about 37% of the surveyed entrepreneurs ().

Figure 6. Monthly incomes (in $) from bamboo and secondary products between large, medium, and small enterprises.

Table 4. Financial analysis of the study enterprises. All values are rounded

Table 5. Contribution of bamboo-based income to entrepreneurs' total annual income

Collection and marketing of bamboo and bamboo products

Our survey revealed that most of the bamboo (80%) was collected through intermediaries. About 16% of the bamboo was collected from distant bamboo hat's (the local term for the open bamboo market) by entrepreneurs themselves and 4% was collected directly from local homesteads and village bamboo groves (). Nearly all the imported bamboo in the area was brought from the south-eastern and hilly regions of the country, including some regular/weekly bamboo hat's in the Khagrachari, Matiranga, Ramgorh, Kaptai, Tabalchri, Panchari, Chekchara, Chikonchara, Koila, Balutila, Hyako, Narayanhat, Korerhat, and Notunbazar areas. The majority of the bamboo from these locations was supplied during the monsoon period to take advantage of the monsoon river current that facilitates rafting of large amount of bamboo from upstream areas (). Beside these regular sources, a considerable proportion of bamboo was also brought illegally from the nearby Tripura state of India. The price of bamboo, however, varied across areas and was usually cheaper in remote areas with comparatively high transportation costs involved. Intermediaries appeared to prefer buying bulk amounts of bamboo from more remote areas to secure the advantage of somewhat lower prices.

We identified three different marketing channels for selling of bamboo and bamboo manufactured secondary products (). Around 27% of the products (with an estimated value of about Tk. 942,830) were collected directly from the market by consumers (producer → consumer). The rest (with an approximate value of Tk. 254,9130) was sold to intermediaries who re-sell the products to a retailer or wholesaler before reaching consumers (producer → intermediary → retailer → consumer or producer → intermediary → wholesaler → consumer). In the case of secondary products, retailers earned the maximum possible from selling bamboo manufactured products, earning in some cases nearly twice the factory prices they received ().

The role of NGOs in promoting bamboo-based enterprises

We identified two different NGOs, namely ‘Grameen Bank’ (the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize winner and the world's pioneer micro-credit provider) and ‘BRAC’ (an acronym for Building Resources Across Communities; the world's largest NGO) supporting local bamboo business and entrepreneurs (56.7% respondents) in the area. The support was, however, limited to purchasing of bamboo and was restricted to between Tk. 25,000 and Tk. 50,000. Recipients of loans had to return the money in monthly installments at an agreed and pre-arranged rate. The amount and extent of such support did, however, appear to be inadequate, and entrepreneurs claimed that procedures for processing their loans were rather complicated, with modest (15–35%) interest rates being charged.

Discussion

In Bangladesh, because of its direct and widespread importance to people's social and economic wellbeing, bamboo plays a crucial role in improving the livelihoods of rural poor people (Nath et al. Citation2000). Moreover, much of the bamboo is harvested by the poor (especially by the women and children) and an estimated 300,000 people in the country are employed in bamboo cutting and collecting from the forests (Banik Citation1998). In our study, most of the entrepreneurs involved in bamboo and bamboo-based products belonged to the age class 41–50 years. The pattern of involvement and importance of enterprise processing and selling of local NTFPs is comparable with the findings of Alamgir et al. (Citation2006) and Uddin et al. (Citation2008). Alamgir et al. (Citation2006) found that most of the entrepreneurs of cane (Calamus spp. and Daeomonorops spp.) enterprises were younger than the age class 41–50 in the nearby Chittagong city corporation area. The diversified uses of bamboo for all conceivable household purposes is also in accordance with the findings of Banik (Citation1994), Nath et al. (Citation2000), Lobovikov et al. (Citation2007), and Motaleb and Hossain (Citation2008) from other parts of the country. Banik (Citation1994) also reported south-eastern hilly districts as being the major sources of all traded bamboo in the country.

Nowadays, because of technological advancements, intrusion of synthetic substitutes into local markets, and changing attitudes of consumers, there have been changes in the pattern of trade and in the consumption of major NTFPs (including bamboo) in urban areas of the country (Mukul Citation2011). In the area, the majority of the traded bamboo (i.e., B. balcoa) was finally used for bamboo scaffolding during building construction. Similar notable use is also evident from Wong (Citation2004). The prices of the articles manufactured from bamboo, other than unprocessed ones, were found to vary depending on raw materials, expertise, and time required to manufacture individual products. Similar observations are also evident from Ahmed et al. (Citation2007) in the case of murta (Schumannianthus dichotoma)-based products in the north-eastern region of the country.

The recent commercialization of many NTFPs makes value chains more complex and difficult (Belcher & Schreckenberg Citation2007). Furthermore, the main actors (e.g., artisans) are often underpaid because of their poor marketing knowledge and their limited access to markets (Moktan et al. Citation2009). The support of NGOs in buying raw materials and disseminating value-added products significantly influences the success of the small-scale enterprises part of the industry (Pereira et al. Citation2006). In our study, the contribution of earnings from trade of bamboo and bamboo-based products to entrepreneurs' net annual incomes was found to vary from person to person. Such an unusual pattern of contribution was also reported by Shackleton and Campbell (Citation2007) in the case of broom grass (Athrixiaphylicoides and Festucacostata) trade in South Africa, where it contributed between 76 and 100% of gross annual income for about 76% of producers. Again, Pereira et al. (Citation2006) in another study found that the income from reed (Cyperustextilis and Juncuskraussii)-based craft products contributed an average of 5–40% to the total annual incomes of the crafters. Some disparities while marketing of bamboo-based secondary products were observed: retailers tended to take advantage of marketing and most of the time they earned the best returns from the sale of products. Similar profit inequalities are evident also in Lim et al. (Citation1994) in the case of NTFP products trade in Malaysia and in Maraseni et al. (Citation2006) in the case of lichen (a common Nepalese NTFP) trade across the large border area between Nepal and India.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the trade patterns, financial contribution, and marketing of bamboo and bamboo-based products in a regional market in southern Bangladesh. It could usefully serve as a baseline for future and in-depth socio-economic studies on bamboo-based enterprises and livelihoods in Bangladesh and elsewhere. We find that bamboo is important not only in generating profits for local entrepreneurs, but also as a way of creating employment for rural, less-skilled workers in production and through provision of intermediary services between producers and consumers. It is recommended that attention should be paid to income disparities amongst different people. We also find that four species are most economically important, suggesting a fruitful route for provision of technical and financial support for growers. We also highlight the many uses of bamboo, which provides clues for where to focus technical and financial assistance for entrepreneurs.

Our findings about price fluctuations and variability are also important. Price variability appeared to depend on maturity and quality, and this reveals clues about how local growers might improve their incomes through provision of better quality and older bamboo for sale. Our finding that there is an off-peak season between May and September is important for understanding the earnings volatility for workers and entrepreneurs.

Despite its contribution to local livelihoods and the regional economy, this thriving industry still seems to rely on one particular season of the year, and this leaves the livelihoods of the rural workers employed in this industry vulnerable. Governments and NGOs should work together with entrepreneurs to make the livelihoods of poor workers more resilient during the off-market period, thereby making the industry more stable and sustainable. This could be achieved through providing greater technical and institutional support in the distribution of bamboo and value-added products from bamboo to urban and regional markets. Existing loan schemes from local organizations to entrepreneurs could also be revised and made more flexible, so that they can comply with entrepreneurs' needs and market situation, for example, by requiring lower repayments during the off-market period.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere appreciation to all the respondents of the study area for sharing their information and for the heartiest cooperation during our field surveys. We also thank the editorial office and two anonymous reviewers for their effort in improving the quality of the manuscript.

Notes

1. Sub-district; administrative entity.

2. Tk. or Taka, Bangladeshi currency; the exchange rate with the US$ during the 2006–2007 was about 69.50 Tk.

References

- Ahmed , R , Islam , ANMF , Rahman , M and Halim , MA. 2007 . Management and economic value of Schumannianthusdichotomain rural homesteads in the Sylhet region of Bangladesh . Int J Biodiversity Sci Manage. , 3 ( 4 ) : 252 – 258 .

- Alamgir , M , Bhuiyan , MAR , Jashimuddin , M and Alam , MS. 2006 . Economic profitability of cane based furniture enterprises of Chittagong City Corporation Area, Bangladesh . J Forestry Res. , 17 ( 2 ) : 153 – 156 .

- Banik , RL. 1988 . Investigation on the culm production and culm expansion behavior of five bamboo species of Bangladesh . Indian J Forestry. , 114 ( 9 ) : 576 – 585 .

- Banik , RL. 1994 . Distribution and ecological status of bamboo forests of Bangladesh . Bangladesh J Forest Sci. , 23 ( 2 ) : 12 – 19 .

- Banik , RL. 1998 May 10–17 1998 . “ Bamboo resources, management and utilization in Bangladesh ” . In Bamboo conservation, diversity, ecogeography, germplasm, resource utilization and taxonomy , Edited by: Rao , AN and Rao , VR . 1998 May 10–17 , 137 – 150 . Proceedings of training course cum workshop . Kunming and Xishuangbanna, Yunnan (China)

- Belcher , B and Schreckenberg , K. 2007 . Commercialisation of non-timber forest products: a reality check . Develop Policy Rev. , 25 ( 3 ) : 355 – 377 .

- Bystriakova , N , Kapos , V , Lysenko , I and Stapleton , CMA. 2003 . Distribution and conservation status of forest bamboo biodiversity in the Asia-Pacific Region . Biodiversity Conserv. , 12 : 1833 – 1841 .

- International Network for Bamboo and Rattan . 1999 . Socio-economic issues and constraints in the bamboo and rattan sectors, INBAR's assessment , INBAR Working Paper No. 23; Beijing, China .

- Kamruzzaman , M , Saha , SK , Bose , AK and Islam , MN. 2008 . Effects of age and height on physical and mechanical properties of bamboo . J Trop Forest Sci. , 20 ( 3 ) : 211 – 217 .

- Khan , SA and Khan , NA. 1994 . Non-wood forest products of Bangladesh: an overview . Bangladesh J Forest Sci. , 23 ( 1 ) : 45 – 50 .

- Lim , HF , Vincent , J and Woon , WC. 1994 . Markets for non-timber forest products in thevicinity of Pasosh Forest Reserve, Malaysia: preliminary survey results . J Trop Forest Sci. , 6 ( 4 ) : 502 – 507 .

- Lobovikov , M. , Paudel , S , Piazza , M , Ren , H and Wu , J. 2007 . World bamboo resources, a thematic study prepared in the framework of the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005 , Rome , , Italy : Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Non-Wood Forest Products Series No. 18 .

- Maraseni , TN , Shivakoti , GP , Cockfield , G and Apan , A. 2006 . Nepalese non-timber forest products: an analysis of the equitability of profit distribution across a supply chain to India . Small-Scale Forest Econ Manage Policy. , 5 ( 2 ) : 191 – 206 .

- Miah , MD , Ahmed , R and Uddin , MB. 2002 . Indigenous management of bamboo plantations in the rural homesteads of floodplain areas of Bangladesh . Int J Forestry Usufruct Manage. , 3 ( 1 and 2 ) : 35 – 40 .

- Moktan , MR , Norbu , L , Dukpa , K , Rai , TB , Dorji , R , Dhendup , K and Gyaltshen , N. 2009 . Bamboo and cane vulnerability and income generation in the rural household subsistence economy of Bjoka, Zhemgang, Bhutan . Mountain Res Develop. , 29 ( 3 ) : 230 – 240 .

- Motaleb , MA and Hossain , MK. 2008 . Depndency of rural livelihood on non woodfores products (NWFPs) in Hathazariupazila, Chittagong, Bangladesh . Int J Forest Usufruct Manage. , 99 ( 1 ) : 1 – 7 .

- Mukul , SA. 2011 . Changing consumption and marketing pattern of non-timber forest products in a competitive world: case study from an urban area of north-eastern Bangladesh . Small-Scale Forestry. , 10 ( 3 ) : 273 – 286 .

- Nath , TK , Uddin , MB and Ahmed , R. 2000 . Role of bamboo based cottage industry in economic upliftment of rural poor: a case study from rural Bangladesh . Malaysian Forester. , 63 ( 3 ) : 98 – 105 .

- Pereira , T , Shackleton , C and Shackleton , S. 2006 . Trade in reed-based craft products in rural villages in the Eastern Cape, South Africa . Develop Southern Africa. , 23 ( 4 ) : 477 – 495 .

- Qing , Y , Zhu-Biao , D , Zheng-liang , W , Kai-Hong , H , Qi-Xiang , S and Zhen-Hua , P. 2008 . Bamboo resources, utilization and ex-situ conservation in Xishuangbanna, South-eastern China . J Forestry Res. , 19 ( 1 ) : 79 – 83 .

- Rana , MP , Mukul , SA , Sohel , MSI , Chowdhury , MSH , Akhter , S , Chowdhury , MQ and Koike , M. 2010 . Economic and employment generation of bamboo-based enterprises: a case study from Eastern Bangladesh . Small-Scale Forestry. , 9 ( 1 ) : 41 – 51 .

- Ruiz Pérez , M , Zhong , M , Belcher , B , Xie , C , Fu , M and Xie , J. 1999 . The role of bamboo plantations in rural development: the case of Anji County, Zhejiang, China . World Develop. , 27 ( 1 ) : 101 – 104 .

- Shackleton , SE and Campbell , BM. 2007 . The traditional broom trade in Bushbuckridge, South Africa: helping poor women cope with adversity . Econ Bot. , 61 ( 3 ) : 256 – 268 .

- Uddin , MS , Mukul , SA , Khan , MASA , Alamgir , M , Harun , MY and Alam , MS. 2008 . Small-scale agar (Aquilariaagallocha Roxb.) based cottage enterprises in Maulvibazar District of Bangladesh: production, marketing and potential contribution to rural development . Small-Scale Forestry. , 7 ( 2 ) : 139 – 149 .

- Vantomme , P , Markkula , A and Leslie , RN , eds. 2002 . Non-wood forest products in 15 countries of tropical Asia: an overview , Bangkok , , Thailand : FAO-Regional office for Asia and the Pacific .

- Wong , KM. 2004 . Bamboo—the amazing grass, a guide to the diversity and study of bamboos in Southeast Asia , DarulEhsan and Kuala Lumpur , , Malaysia : International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI) and University of Malaya, Selangor .

- Yuming , Y , Kanglin , W , Shengji , P and Jiming , H. 2004 . Bamboo Diversity and Traditional Uses in Yunnan, China . Mountain Res Develop. , 24 ( 2 ) : 157 – 165 .